Abstract

We report herein that the anti-CD20 therapeutic antibody, rituximab, is rearranged into microclusters within the phagocytic synapse by macrophage Fcγ receptors (FcγR) during antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis. These microclusters were observed to potently recruit Syk and to undergo rearrangements that were limited by the cytoskeleton of the target cell, with depolymerization of target-cell actin filaments leading to modest increases in phagocytic efficiency. Total internal reflection fluorescence analysis revealed that FcγR total phosphorylation, Syk phosphorylation, and Syk recruitment were enhanced when IgG-FcγR microclustering was enabled on fluid bilayers relative to immobile bilayers in a process that required Arp2/3. We conclude that on fluid surfaces, IgG-FcγR microclustering promotes signaling through Syk that is amplified by Arp2/3-driven actin rearrangements. Thus, the surface mobility of antigens bound by IgG shapes the signaling of FcγR with an unrecognized complexity beyond the zipper and trigger models of phagocytosis.

Significance

Antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) is an important effector mechanism for the removal of malignant, immunologically aberrant, and infected cells during treatment with therapeutic antibodies or adaptive immune responses. This work demonstrates that macrophages overcome weak confinement of cell-surface antigens on B lymphoma cells and that they extensively rearrange FcγR-IgG-antigen complexes during ADCP. Thus, new paradigms are needed for understanding ADCP in the context of surface mobile IgG. Moreover, we found that increased mobility of rituximab on the surface of B lymphoma cells is beneficial for ADCP efficacy.

Introduction

Therapeutic antibodies are a rapidly growing class of drugs for treating rheumatologic, viral, and malignant conditions (1,2,3). Nearly all are of class immunoglobulin G (IgG) owing to long circulatory half-lives, broad tissue distribution, and the ability to activate potent immune effector functions on cells bearing Fcγ receptors (FcγRs) (4,5,6). A growing body of evidence indicates that antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) by macrophages and monocytes is an important and likely essential effector mechanism, especially for the destruction of cells of lymphocytic origin (4,7,8,9,10,11). Some of the most successful therapeutic antibodies that mediate ADCP killing of lymphocytes include anti-CD20 (rituximab) and its derivatives (2,8,12,13). However, suboptimal ADCP or trogocytosis, characterized by small “bites” of the target cell’s antigen and plasma membrane, can lead to either the target cell’s evasion via antigen modulation or cell killing. This phenomenon manifests in rituximab (RTX) treatment where B cell antigenic modulation by trogocytosis depletes CD20 and enables escape of the target (14,15). In some cases, as with anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (cetuximab) on breast cancer cells, these partial attacks may ultimately lead to the target cell’s destruction (16,17). Thus, there is a pressing need to understand the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which FcγR ligation to target-bound IgG orchestrates effective ADCP and how the antigen on the target cell influences this process to enable the development of improved therapeutic antibodies and adjuvants that modulate phagocyte function.

Macrophages, monocytes, and dendritic cells express all FcγRs to varying degrees and are resident in nearly all tissues of the body, making them key effectors of IgG-mediated responses and antigen presentation (4,8,11,18,19,20). FcγR function on macrophages contributes to therapeutic antibody anti-tumor activity, provided that inhibitory signals originating from the microenvironment are overcome, including the use of STING agonists to promote ADCP and CD47/SIRPα blocking antibodies to alleviate innate inhibitory signaling in tumor microenvironments (8,20,21,22,23). Recently the concept of engineering macrophages with chimeric antigen receptors, analogous to chimeric antigen receptor T cells, as an alternative to cell-based therapeutic strategy has emerged (24), further highlighting the need to understand the molecular mechanisms regulating macrophage ADCP.

The rearrangements of phagocytic receptors and inhibitory molecules within the phagocytic synapse have been the focus of models for explaining how molecular reorganization amplifies pro-inflammatory and inhibitory signaling for phagocytosis. The exclusion of phosphatases with large extracellular domains such as CD45 and CD148 from the phagocytic synapse contributes to the alleviation of inhibition of phagocytic receptor-associated Syk kinase activity (25). Similarly, signal amplification by the grouping of activating receptors can produces regions of high kinase activity and low phosphatase activity including Dectin-1 diring the phagocytosis of yeasts, FcεR binidnig of IgE complexes, or FcγRs bingin IgG on target cells (26,27,28,29,30). The minimal valence of these interactions requires five grouped FcγRs to initiate signaling (31); however, work is needed to understand how the clustering of IgG at the interface of a living cell promotes exclusion of phosphatases and the formation of localized high-valency interactions to promote FcγR activation. Indeed, the internalization of beads displaying engineered clustering, via DNA origami, at different densities indicated that tighter clustering of ligands predicted phagocytosis when the total number of ligands were held constant (30).

ADCP and the mechanisms underpinning its efficacy and failure are shaped by the two historical models of phagocytosis known as the “zipper” and the “trigger” (32,33,34,35). The zipper model posits that FcγRs must sequentially engage IgG on the target surface as actin polymerization extends membrane over the target, like the closing of a zipper (32,34,35). In contrast, the trigger model posits that if sufficient FcγRs bind IgG, an activating signal will trigger large-scale cytoskeletal rearrangements to engulf the target (34,35). In seminal work from the Silverstein lab, the zipper model prevailed as the mode by which FcγRs successfully facilitate target engulfment. Specifically, they observed that when IgG was “capped” onto one side of the lymphocyte surface macrophages failed to engulf them, leading to trogocytosis of the IgG, whereas diffuse IgG distributions were associated with successful ADCP (32). Subsequent work using RAW264.7 cells suggested that asymmetric arrangements of RTX were the result of target cell cytoskeletal movements and resulted in trogocytosis (36). However, extensive reorganization of IgG-FcγR by macrophages on synthetic membranes (29,37) and on cancer cell anti-CD19 (38) has been observed. Moreover, IgG antibodies vary widely in their ability to mediate therapeutic responses (39,40). Thus, understanding the organization of FcγR-IgG clusters will provide critical information for the rational design of next-generation therapeutic antibodies including establishing criteria for antigen selection, optimal antibody Fc structure, and complementary adjuvant therapies to promote ADCP.

Here, we have addressed how cellular rearrangements of RTX influence FcγR signaling at the macrophage/target-cell interface during ADCP. Our findings indicate that the surface mobility of RTX has a modestly beneficial effect on ADCP, with increased surface mobility leading to increased Syk recruitment and improved likelihood of successful ADCP. Moreover, we find that Syk and Arp2/3 work together to organize IgG-FcγR microclusters prior to and during engulfment and limit trogocytic clearance of IgG from the target cell.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Fetal liver-derived macrophages (FLMs) were prepared from embryonic-day-18 mouse fetuses from B6J.129(Cg)-Igs2tm1.1(CAG-cas9∗)Mmw/J mice (stock no. 028239; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) with approval from South Dakota State University Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee. Liver tissue was mechanically dissociated using sterile fine-pointed forceps, and a single-cell suspension was created by passing the tissue through a 1-mL pipette tip. Bone-marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were prepared using single-cell suspensions of bone marrow obtained from the long bones of B6J.129(Cg)-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1.1(CAG-cas9∗,-EGFP)Fezh/J mice (stock no. 026179; The Jackson Laboratory). BMDM and FLMs were cultured in bone marrow medium containing DMEM (Corning, New York, NY) supplemented with 30% L cell supernatant, 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (pen/strep) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2. Prior to lattice light-sheet microscopy (LLSM) experiments, FLMs were cultured in DMEM/F12 (Gibco, Waltham, MA) supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated FBS (R&D Systems), 1% pen/strep (Gibco), 50 ng/mL CSF-1 (BioLegend), and 0.5 μg/mL plasmocin (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) at 37°C with 7.5% CO2. WIL2-S cells (CRL-8885) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (ATCC 30-2001) containing 10% FBS and 1% pen/strep (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Plasmids, lentiviral transduction, and CRISPR gene disruption

Lentiviral expression plasmids pLJM1-Syk-mScarlet and pLJM1-Lck(mem)-mNeonGreen (mNG-Mem) were created by gene synthesis (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ). pCMV-VSV-G was a gift from Bob Weinberg (Addgene plasmid #8454; http://n2t.net/addgene:8454; RRID:Addgene_8454) (41). psPAX2 was a gift from Didier Trono (Addgene plasmid #12260; http://n2t.net/addgene:12260; RRID:Addgene_12260). pLJM1-EGFP was a gift from David Sabatini (Addgene plasmid #19319; http://n2t.net/addgene:19319; RRID:Addgene_19319) (42). Lentiviral vectors were produced in 293T cells by transfection with pLJM1-Syk-mScarlet-I in combination with helper plasmids psPAX2 and pCMV-VSV-G, using linear 25 kDa polyethyleneimine. Lentiviral supernatant was harvested after 48 h, centrifuged, and added to FLMs cultured in bone marrow medium supplemented with 10 μg/mL of cyclosporine A. Virally transduced cells were selected with blasticidin (10 μg/mL) and/or puromycin (5 μg/mL) for 48 h post transduction. Macrophages were split into respective well formats for experiments. Once BMDMs or FLMs reached appropriate seeding density, they were used for phagocytosis assays, frustrated phagocytosis, and live imaging.

Antibody labeling with NHS ester fluorophores

Anti-human CD20 murine IgG2a (hcd20-mab10; InvivoGen) and mouse anti-biotin mIgG2a [3E6] (ab36406; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) were fluorescently labeled using Alexa Fluor 647 N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) ester (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or CF 647 NHS ester (Biotium, Fremont, CA). Prior to labeling, antibodies were buffer exchanged in Zeba Spin desalting columns (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with three washes of PBS (pH 7.4) without Ca2+ and Mg2+. Exchanged antibodies were mixed with NHS fluorophore at molar ratio of 1:10 IgG/fluorophore in 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with pH of 8.1–8.3. The mixture was incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After 1 h of incubation, excess fluorophores in the solution were removed using Zeba Spin columns (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Supported lipid bilayers

Bilayers were formed by spontaneous fusion of lipid vesicles. Small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) were prepared by mixing 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-polyethylene glycol 2000 (DSPE-PEG(2000))-biotin (880129; Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) and 1,2-dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) (850355; Avanti Polar Lipids) or 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine (POPC) (850457; Avanti Polar Lipids) at a molar ratio of 1:1000 with total lipid concentration of 500 μM (380 μg/mL) in chloroform. Lipids were then roto-vacuum dried for up to 60 min in a glass test tube. The lipid film was resuspended using 1 mL of PBS (pH 7.4) without Ca2+ and Mg2+. The glass tube was then sonicated for 5 min using a bath sonicator (JSP US40) followed by extrusion (610,000; Avanti Polar Lipids) through a 100-nm filter at least 13 times (Whatman Nucleopore Track-Etch 100-nm membrane). POPC liposomes, with Tm of −2°C, were extruded and sonicated at room temperature, whereas DPPC liposomes, with Tm of 41°C, were extruded and sonicated at 60°C.

The 500-μM stocks of SUVs were diluted 1:6 in 2 mM Mg2+ PBS. POPC-supported lipid bilayers (SLBs) were formed by pipetting the diluted lipids onto Hellmanex III (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA) cleaned 96-well (MGB096-1-2-LG-L; Dot Scientific, Burton, MI) plates and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. DPPC bilayers were formed by pipetting the diluted lipids onto a 25-mm Hellmanex III (MilliporeSigma) cleaned coverslip mounted in a pre-warmed AttoFluor chamber (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated at 70°C for 30 min on a slide-warmer (Premiere XH-2001; C & A Scientific, Sterling, VA). Bilayers were also formed on silica beads of 5-μm diameter (Bangs Laboratories, Fishers. IN). Silica beads (SBs) were washed by centrifugation twice with acetone, twice with ethanol, and twice with deionized water. POPC and DPPC SUVs were then incubated at 37°C or 70°C for 30 min with the cleaned silica beads. Following incubation, excess liposomes were removed by pipetting in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS; Corning 21023CV) containing FBS in 1:1000 ratio (HBSS + 0.1% FBS). SLBs and SLB-SBs were incubated with anti-biotin IgG (3E6) (Abcam ab36406) conjugated with Alexa Fluor 647 NHS ester (Thermo Fisher Scientific) SLBs at 37°C for 30 min. SLBs were rinsed without exposure to air to remove excess IgG using HBSS.

For imaging FLM cells on SLBs, SLBs were made directly on Hellmanex III (MilliporeSigma) cleaned 25-mm coverslips (no. 1.5, Thermo Fisher) or onto 96-well glass-bottom plates (MGB096-1-2-LG-L, Dot Scientific) for high-content experiments. The 25-mm coverslips were imaged in AttoFluor chambers (Thermo Fisher).

Immunostaining and analysis of pTyr and pSyk

BMDMs were plated into 96-well glass-bottom plates and exposed to silica beads bearing DSPE-PEG(2000)-biotin at 1:1000 in POPC or DPPC bilayers, then opsonized using anti-biotin IgG2a for 12 min. Cells were then rinsed with ice-cold PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at room temperature for 30 min, followed by blocking with PBS containing 5% FBS for 10 min and incubation with a 1:50 dilution of anti-pSyk-AF647 (C87C1) or anti-pTyr-AF647 (P-Tyr-100) and anti-CD45-AF488 (D3F8Q; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) overnight at 4°C with gentle rocking. Images were captured using an ImageXpress Micro XLS Widefield High-Content Analysis System (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) using a 20 × 0.70 numerical aperture (N.A.) objective lens. Quantification was carried out using a MATLAB script to pre-process all images, background subtraction, and exposure-time normalization, aster which manual selection was performed on open phagocytic cup structures as identified in the anti-CD45-AF488 image. Regions of interest (ROIs) were centered on the identified cups, and the total fluorescence in the anti-pSyk or anti-pTyr channel was reordered.

Manipulation of actin and CD20 mobility in target cells

PFA (T353-500; Thermo Fisher Scientific), latrunculin B (Lat B) (428020; MilliporeSigma), and jasplakinolide (Jas) (420107; MilliporeSigma)/blebbistatin (Bleb) (B0560; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were used for manipulating CD20 mobility. PFA (4%) was prepared using powder-form PFA, which was diluted to prepare 2% PFA in PBS (pH 7.4) without Ca2+ and Mg2+and stored at −20°C. WIL2-S cells were treated using 2% PFA for 10 min at 4°C. Lat was resuspended in DMSO at a concentration of 25 mg/mL (62.5 mM) and stored at −20°C. Lat B solution (12.5 mM) was prepared from the stock solution and used to treat target cells for 30 min at 4°C. Jas and Bleb were stored in DMSO at concentrations of 0.71 mg/mL (1 mM) and 5 mg/mL (17 mM), respectively, at −20°C. Cells were incubated with 75 μM Bleb for 10 min, followed by 1 μM Jas for 5 min. After drug treatment, WIL2-S cells were thoroughly washed by centrifugation three times and incubated on ice. FLMs were treated with the Arp2/3 inhibitor CK-666 (MilliporeSigma) at 1.2 μM in HBSS for 1 h at 4°C before live imaging.

TIRF imaging

FLMs were dropped onto prepared SLBs. Total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF)-based imaging was conducted using an inverted microscope built around a Till iMic (Till Photonics, Munich, Germany) equipped with a 60 × 1.49 N.A. oil-immersion objective lens. The entire microscope setup and TIRF-360 imaging and centering of the back-focal plane was previously described in (43). Cells were labeled by rinsing with 1 μg/mL DiI (1,19-dioctadecyl-3,3,39,39-tetramethylindocarbocyanine) in 2.5% DMSO/PBS. Excitation for TIRF was provided by a 633-nm laser for AF647 anti-biotin mIgG2a, a 561-nm laser for Syk-mScarlet, and a 488-nm laser for mNG-Mem.

TIRF-360 was used to create uniform TIRF illumination for fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) by steering the laser at the back-focal plane above or below the critical angle to produce a TIRF and Epi illumination image pair as previously described (44). For spreading area, wild-type, Syk-knockout (KO), and CK-666-treated FLMs were dropped on both mobile and immobile SLBs. FLMs expressing mNG-Mem were imaged 10 min after dropping, and spreading areas were measured by manually thresholding mNG-Mem fluorescence using ImageJ/Fiji (45).

Image analysis on the TIRF-360 data was carried out using custom MATLAB scripts (ver. 2023b; MathWorks Natick, MA) in conjunction DipImage (Diplib 3.4.0, http://www.diplib.org/). All time-lapse videos were bias subtracted and normalized for exposure times. TIRF/Epi ratios were computed, and a binary mask was generated on the mNG-Mem TIRF image and used to measure the mask area and average TIRF/Epi ratio per pixel for the Syk-mScarlet and mNG-Mem images, as well as the IgG-647 signals. TIRF/Epi ratio images were shown using the “inferno” colormap from MatPlotLib Perceptually Uniform Colormaps (https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/62729-matplotlib-perceptually-uniform-colormaps, MATLAB Central File Exchange, retrieved October 26, 2023). The initial IgG-647 density on the bilayer was quantified from an ROI placed in a cell-free region on the first frame of the video.

Confocal imaging

FLMs plated on ethanol-flamed 25-mm coverslips were challenged with biotin-labeled and IgG2a-opsonized WIL2-S cells as targets. Imaging was performed on a Till Photonics Andromeda Spinning Disk Confocal microscope (Till Photonics), using a 60 × 1.4 N.A. oil-immersion objective lens. Excitation for confocal imaging was provided by a 640-nm laser for AF647 anti-CD20 mIgG2a, a 561-nm laser for Syk-mScarlet, and a 515-nm laser for mNG-Mem.

High-content imaging

For high-content experiments, BMDMs were plated on 96-well plates for at least 2 h (MGB096-1-2-LG-L, Dot Scientific) before imaging, WIL2-S cells were opsonized with anti-hCD20 mIgG2a (RTX, InvivoGen) and treated with different drugs including PFA, Lat B, and Jas/Bleb. Fluorescent detection of internalized targets was achieved by labeling WIL2-S cells with pHrodo SE Red dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in PBS (pH 7.4) without Ca2+ and Mg2+. Medium was replaced with HBSS prior to imaging by pipetting. High-content fluorescent imaging was conducted using an ImageXpress Micro XLS Widefield High-Content Analysis System (Molecular Devices) equipped with a 20 × 0.70 N.A. objective lens. For each well, four fields of view were imaged for pHrodo Red (excitation (ex.) 562/40, emission (em.) 624/40), GFP (ex. 482/35, em. 536/40), and HCS NuclearMask Blue (ex. 377/50, em. 447/60). Images were analyzed using a custom pipeline in CellProfiler (46) to obtain the number of engulfed WIL2-S cells per macrophage to quantify the phagocytic index.

The density of IgG on cells was measured using Alexa Fluor 633 goat anti-mouse IgG2a cross-adsorbed secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The secondary antibody was diluted 1:1000 in HBSS + 0.1% FBS. WIL2-S cells were opsonized with dilutions of anti-human CD20-murine IgG2a (hcd20-mab10, InvivoGen) for 30 min followed by incubation with the diluted secondary antibody for 30 min and washed three times with HBSS. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis was performed on a BD Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer and analyzed using BD FlowJo (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Cell preparation for LLSM ADCP

FLMs (2–3 × 105) expressing Syk-mScarlet and Mem-mNG were plated overnight in a 6-well dish on absolute ethanol-flame-cleaned, 5-mm diameter, #1 thickness coverslips (Warner Instruments, Holliston, MA). WIL2-S cells (1.5 × 106) were incubated with 20 μM calcein violet AM (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) and 5 μg/mL of RTX-CF647 for 30 min at 4°C and washed at least three times in HBSS with 1% FBS. The field of view was chosen to contain a single FLM, and 3 × 105 labeled WIL2-S cells were dropped on top of the coverslip and imaged immediately after to capture the initial contact.

Lattice light-sheet microscopy

Volumetric image stacks were generated using dithered square virtual lattices (Outer N.A. 0.55, Inner N.A. 0.50, approximately 30 μm long), stage scanning of 151 slices with 0.5-μm step sizes, resulting in 254-nm deskewed z-steps, an ROI of ∼76 μm × 76 μm × 42 μm, and 12-ms exposures resulting in 10- to 12-s intervals. The laser illumination was optimized to minimize photobleaching during the full acquisition, resulting in 0.58 μW (405 nm) for calcein violet, 15 μW (488 nm) for Mem-mNG, 22 μW (560 nm) for Syk-mScarlet, and 17 μW (640 nm) for Rtx-CF647 as measured at the rear aperture of the excitation objective.

Post-processing and visualization

The raw volumes acquired from the LLSM were processed using a standard pipeline (47) including deskewing, deconvolving, and rotating to coverslip coordinates in LLSpy (48). We applied a fixed background subtraction based on an average dark current image, 10 iterations of Lucy-Richardson deconvolution with experimentally measured point spread functions for each excitation, followed by rotation to coverslip coordinates and cropping to the region of interest for visualization. The fully processed data were opened as a volume map series in UCSF ChimeraX and utilized isosurface, mesh, and 3D volumetric renderings to examine the data (49).

Surface visualizations were performed using ChimeraX (49) by generating a surface rendering of the target cell (WIL2S), using an empirically determined threshold for the time series from the calcein violet image. Using the surface rendering of the target, we threshold all pixels in the raw data image that fit the rendered target model and have an applied dilation and erosion operation to create a masked image per time point (50). The masked image was then applied to the signal channel (e.g., Syk or IgG). Using the spatial coordinates of each pixel of the target and signal, a ranked query search (KD-tree approach) was used to determine the closest 200 points, confined to a 1.5-μm search, in the signal channel to each vertex in the rendered object. The resulting array of closest pixels in the signal channel (e.g., Syk or IgG) were averaged for intensity and assigned to the rendered objects’ positional vertex (50). Identification of the top and bottom hemispheres for measurement was carried out by using the plane equation (Eq. 1) to generate the output P, where vertices yielding P positive are above (top) the plane, P negative are below (bottom) the plane, and P equal to zero are in line with the plane. Inputs are as described below.

| (1) |

Eq. 1 renders the object centroid coordinates (x1, y1, z1), object vertex position (x, y, z), and surface normal (a, b, c).

Solving for the target centroid coordinate (x1, y1, z1) was achieved by taking the mean average (x, y, z) of the target, and surface normal (a, b, c) was determined empirically from ChimeraX’s clip function and recorded via the clip list function manually by observing the direction of phagosome extension. Using the prior values as constants defines a plane, and comparisons are made vertex-wise from the target to determine whether the vertex sits on the top or bottom half of the target. Vertices are then binned according to the side of the plane on which they lie, and the corresponding vertex intensities previously determined are then summed for each side.

Results

Rituximab is rapidly microclustered upon contact between macrophage and B lymphoma cells and pools at the base of the phagosome, where it amplifies FcγR signaling during target-cell engulfment

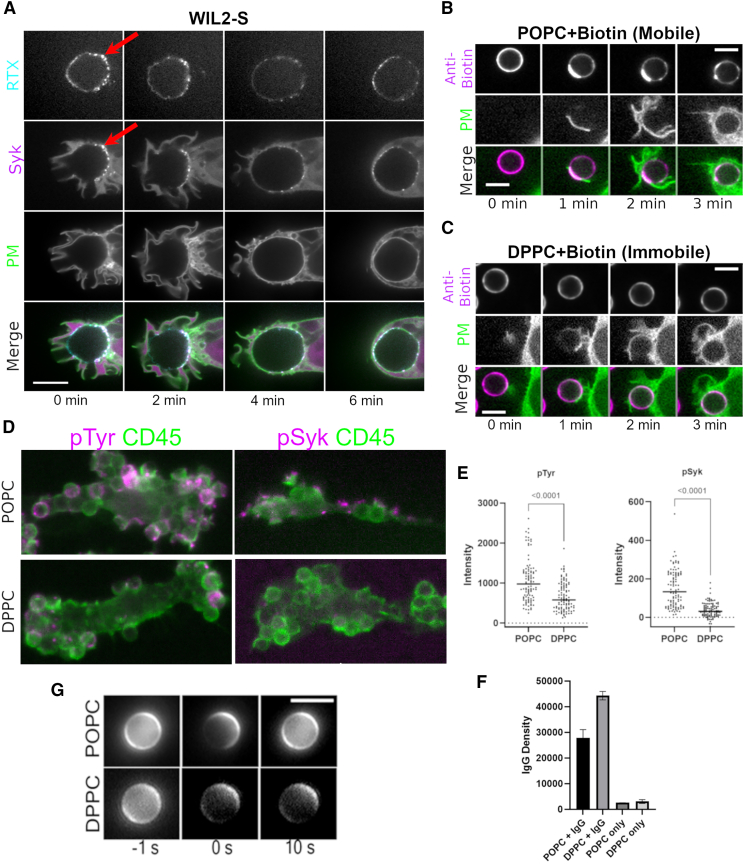

Given our prior findings that IgG presented on fluid SLBs is rearranged by macrophage FcγRs in a process reminiscent of T cell receptor (TCR) and B cell receptor (BCR) rearrangements, we hypothesized that similar rearrangements occur during ADCP (37). To address this question in a clinically relevant context, we sought to determine the movements of RTX on the surface of B cell lymphoma targets during ADCP. Confocal microscopy of opsonized WIL2-S cell ADCP by FLMs revealed that CD20-docked RTX-AF647 was rearranged into microclusters upon contact with the macrophage (Fig. 1 and Video S1). Notably this reorganization is much larger than the hexomeric structures observed with RTX docked to CD20 (51). Moreover, a previously validated Syk-mScarlet construct (31) was recruited to these microclusters, demonstrating a high degree of ITAM phosphorylation. During engulfment, the RTX-FcγR-Syk microclusters were redistributed over the surface of the WIL2-S target as the enveloping pseudopod advanced, ultimately producing a phagosome containing the WIL2-S target with an approximately uniform distribution of RTX-FcγR-Syk microclusters forming the connection between phagosome and target membranes (Fig. 1 A). This behavior was representative of over 12 confocal videos of independent phagocytic events.

Figure 1.

Microclustering of IgG-FcγR at the phagocytic synapse amplifies signaling on mobile IgG surfaces. (A) Confocal imaging of RTX-AF647 on WIL2-S cells displayed distinct microclusters at the contact with macrophages (red arrow), to which Syk-mScarlet was recruited relative to the membrane (mNG-Mem) in FLM macrophages. During engulfment, new RTX-AF647 microclusters formed, pooled at the base of the phagocytic synapse, and were ultimately redistributed over the complete phagosome/target surface (scale bar, 10 μm). (B and C) Confocal imaging of macrophage-induced microclustering and rearrangement of anti-biotin IgG on beads coated with biotin-DPPE embedded in (B) mobile (POPC) or (C) immobile (DPPC) bilayers (scale bar, 5 μm). (D) Phosphotyrosine and phospho-Syk (pTyr525/526) immunofluorescence (macrophage (magenta) counterstained with anti-CD45 (green)) in BMDMs 12 min after being fed silica beads displaying anti-biotin IgG on mobile (POPC) or immobile (DPPC) SLBs. (E) Quantification of p-Tyr or p-Syk immunofluorescence (total intensity from a 5.5-μm ROI) on individual forming phagosomes for beads bearing POPC- or DPPC-supported lipid bilayers (Student’s t-test comparison, p-value). (F) Quantification of AF657-IgG density/bead (n = 100 beads/condition; error bars denote SD). (G) Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching of AF647-IgG displayed in POPC- or DPPC-supported lipid bilayers on silica beads (scale bar, 5 μm). To see this figure in color, go online.

An FLM expressing Syk-mScarlet and mNG-Mem during ADCP of an RTX-AF647 opsonized WIL2-S cell. Video duration is 7 min (scale bar, 10 μm).

To determine whether the forces responsible for reorganizing RTX originated from the macrophage, we imaged the redistribution of anti-biotin IgG on fluid and immobile supported lipid bilayers on silica beads (SLB-SBs, Fig. 1 G). Upon contact with fluid POPC SLB-SBs, anti-biotin IgG clustered at the base of the phagocytic synapse indicate capture by FcγRs (Fig. 1 B), which are restricted to the contact site and have slower diffusion coefficients (∼0.1 μm2/s) than IgG on the SLB (∼1–2 μm2/s) (31). Engulfment of the fluid SLB-SB was coincident with redistribution of the anti-biotin-IgG-AF647 over the bead surface, recapitulating the movements observed for RTX on WIL2-S targets (Fig. 1, A and B). When SLB-SBs were made from gel-phase/immobile DPPC, little or no change in the distribution of anti-biotin-IgG was observed (Fig. 1 C). We used our SLB-SB system to determine whether microclustering of mobile IgG promotes FcγR signal amplification as has been reported for BCRs and TCRs (52,53,54). Indeed, immunostaining of BMDMs fixed during phagocytic cup formation (∼12 min after addition of SLB-SB targets) demonstrated that tyrosine phosphorylation (pTyr) and Syk phosphorylation (pSyk) was significantly elevated on mobile SLBs (POPC) compared with immobile SLB-SBs (DPPC) (Fig. 1, D and E) even when IgG densities were slightly higher on the immobile DPPC beads (Fig. 1 F). These data indicate that 1) engaged FcγRs influence the movement of target-bound IgG, 2) clustered IgG-FcγRs amplifies Syk recruitment and phosphorylation, and 3) redistribution of the IgG over the surface of the target occurs during and after engulfment. Thus, given permissive antigen mobility, forces within the macrophage constrain the diffusion of the IgG-FcγR complex to drive substantial rearrangements of target-associated IgG, and these forces dissipate during or following closure of the forming phagosome.

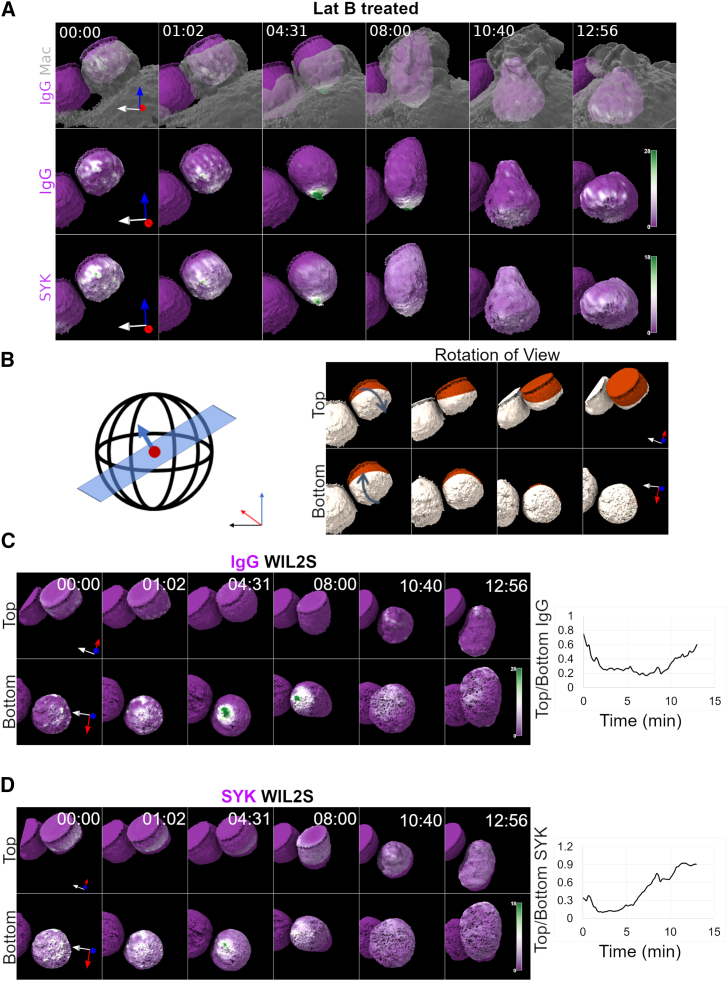

To gain a more complete three-dimensional (3D) view of this process, we used LLSM to capture 3D fluorescence distributions with minimal phototoxicity (55). Surface reconstructions of LLSM data revealed that RTX-AF647 was relatively uniform on the surface of WIL2-S cells with slightly elevated densities on filipodia (Fig. 2 A). Upon contact with the macrophage, the RTX-AF647 formed microclusters that rapidly recruited Syk-mScarlet (Fig. 2 A; Videos S2, S3, and S4). As the phagocytic cup began to form, the microclusters assembled into larger patches as they streamed toward the base of the phagosome (initial contact site), suggesting a coupling between the macrophage FcγRs and the retrograde flow of the macrophage’s actin cytoskeleton. Within 2–3 min post contact, macrophage membrane ruffles radiated in a flower-like pattern and engulfed the WIL2-S cell as RTX microclusters continued to accumulate into larger patches near the base of the forming phagosome where increased recruitment of Syk-mScarlet was observed. Extension of the pseudopod followed along with sinking of the WIL2-S cell into the macrophage cytoplasm, during which many microclusters were propelled forward over the target, resulting in redistribution of the RTX-Syk into a radially symmetric position over the internalized target (Fig. 2 A; Videos S2, S3, and S4). To quantify the redistribution of IgG and Syk, the target cell was split into two hemispherical ROIs using the surface normal vector relative to the forming phagosome, and the surface proximal intensity was quantified for each region (Fig. 2 B). Quantification of IgG in the “top” hemisphere (where the phagosome closes) relative to the “bottom” hemisphere (base of phagosome, initial contact site, Fig. 2 C) demonstrated that RTX preferentially formed large patches on the bottom as observed in a drop of top/bottom ratio to below 1, which then redistributed more evenly over the surface of WIL2-S cell with a final ratio of 0.8. Importantly, much of the RTX remained patched after internalization (Fig. 2 C). Similar quantification of Syk-mScarlet redistribution demonstrated intense localization at the initial contact site, coincident with initial patches of IgG at the base of the phagosome, resulting in a low top/bottom ratio (Fig. 2 D). As the phagosome formed, Syk was recruited to the IgG patches at the top, resulting in a nearly uniform distribution of Syk between the two hemispheres (Fig. 2 D). These data indicate that the macrophage cytoskeleton drives rearrangement of RTX docked to FcγRs during ADCP in three phases: 1) microclustering and Syk recruitment during initial contact and early pseudopod extension, followed by 2) retrograde accumulation of larger clusters with sustained Syk recruitment at the base of the phagocytic cup during which engulfment occurs; and 3) the phagosome closes and IgG-FcγRs redistribute over the surface of the target.

Figure 2.

Lattice light-sheet microscopy (LLSM) imaging of RTX clustering and Syk recruitment. (A) Lattice light-sheet imaging of RTX (IgG) microclustering on the surface of the WIL2-S cell (magenta-green) and the recruitment of Syk relative to the movements of macrophage membrane (mNG-Mem, gray transparent surface). (B) Hemispherical coordinates and view rotation on the WIL-2S target cell. (C) RTX (IgG) clustering during ADCP in either top or bottom hemispheres and the quantified top/bottom ratio. (D) Syk distribution in the target surface proximal region during ADCP with quantified top/bottom ratio (image volume is 29 μm × 28 μm × 31 μm). To see this figure in color, go online.

An FLM expressing Syk-Scarlet and mNG-Mem was challenged by WIL2-S cell labeled with calcein violet and RTX-AF647. Video duration is 11:07 min (image volume is 29 μm × 28 μm × 31 μm).

Same as Video S2, but without the macrophage membrane. Video duration is 11:07 min (image volume is 29 μm × 28 μm × 31 μm).

Same as Video S2, but without the macrophage membrane, showing only Syk movements. Video duration is 11:07 min (image volume is 29 μm × 28 μm × 31 μm).

Surface mobility of RTX is beneficial for ADCP

The cortical actin cytoskeleton is known to constrain the diffusion of transmembrane proteins (56,57,58,59), and colocalization of CD20 with moesin and ICAM-1 has been observed in polarized B cells (60) as well as a localization to the uropod in motile B lymphoma cells (36), indicating that the actin cytoskeleton influences the surface mobility of CD20-RTX. Moreover, the binding of RTX to CD20 can induce the formation of hexameric complexes that may associate with lipid rafts and further limit diffusion (51). To address the role of the target cell’s cytoskeleton in constraining the mobility of CD20-RTX, we measured the phagocytic index (number of target cells internalized per macrophage) as a function of RTX density in WIL2-S cells with manipulated actin cytoskeletons (Fig. 3, A and B). To control for changes in the cell-surface abundance of CD20 during these treatments, the RTX density was measured by flow cytometry and used to define the IgG surface density (Fig. S2). Indeed, treatment of WIL2-S cells with the actin depolymerizing drug, Lat, increased the phagocytic index at lower surface densities of RTX (Fig. 3). Moreover, this treatment resulted in a dramatic increase in the mobile fraction and diffusion of CD20-RTX over that of non-treated cells (Fig. 3), indicating that the WIL2-S cell’s cytoskeleton constrains the mobility of CD20-RTX regardless of oligomeric state. To determine whether this constraint was an active or passive process relative to the interaction with the macrophage, we treated cells with the combination of Jas and Bleb. This combination fragments actin and disables myosin II motors, effectively freezing the cell with minimal effect on cell shape or topography (61,62). Jas/Bleb had no discernible effect on the mobile fraction of CD20 or on ADCP, indicating that a fragmented and immobilized cytoskeleton created a similar boundary for CD20-RTX movement as encountered in the living cell (Fig. 3), suggesting a passive fence-type constraint on CD20-RTX mobility. Fixation of WIL2-S cells with PFA to permanently immobilize CD20-RTX (Fig. S4) required a greater surface density of RTX to promote ADCP (Fig. 3). Notably, FRAP measurements of RTX-AF647 demonstrated limited diffusion for untreated cells (mobile fraction <10%; Fig. 3, C–E). However, engagement with macrophage FcγR leads to its rearrangement on the cell surface (Figs. 1 and 2), suggesting that cytoskeletal fences within the target cell can be crossed by binding to macrophage FcγRs (57,63,64).

Figure 3.

Enhanced ADCP and IgG/Syk microcluster rearrangement with increasing CD20 surface mobility. (A) High-content imaging of BMDMs (green) and internalized WIL2-S cells (pHrodo Red, magenta) opsonized with RTX, untreated or following actin manipulation with Lat, Jas/Bleb, or fixation with paraformaldehyde (scale bar, 10 μm). (B) Quantified phagocytic index for measured RTX densities on WIL2-S cells treated with Lat, Jas/Bleb, or PFA (error bars denote SEM from 200 cells across two experiments per RTX density). (C–E) (C) FRAP images and (D) normalized recovery traces of anti-RTX-AF647 on single WIL2-S cells treated with the indicated actin disrupting drugs, and (E) the average mobile fraction FM (n = 10 cells/condition, error bars denote SD). To see this figure in color, go online.

To test the generality of these findings, we examined other B lymphoma cell lines and checked to see whether actin disruption affected the surface glycocalyx (65), which can limit engagement of FcγR (65). In WIL2-S cells, treatment with Lat led to a slight reduction in total glycosylated cell-surface proteins at an amount that was similar to the reduction in CD20 abundance (Fig. S1), consistent with the loss of cell-surface roughness (Fig. 3 C), leading to a reduction in cell-surface area by endocytosis. In addition, we found that depolymerization of actin in Ramos and Daudi cells led to similar or slightly better ADCP in Ramos but not Daudi cells relative to non-treated controls, and with little change in their glycocalyx density (Fig. S2), indicating that this is a general phenomenon, with potentially different efficacies, in different cell types.

Removal of target cytoskeleton leads to dramatic reorganization of RTX

Given that our FRAP measurements indicated that Lat treatment increased the mobility of CD20-RTX, we examined the movements of CD20-RTX during ADCP by LLSM. Indeed, Lat treatment of the WIL2-S cell produced dramatic microclustering followed by pooling of RTX at the base of phagosome prior to engulfment (Fig. 4 A; Videos S5, S6, and S7). The extent of this pooling of microclusters at the phagosome base was even more dramatic when compared with non-treated WIL2-S targets (Fig. 2; Videos S3 and S4). Thus, the movement of these microclusters is resisted by the target-cell cytoskeleton but dominated by interactions with Syk-bound FcγR toward the base of the phagocytic cup, potentially similar to that observed with deformable but immobile beads (66). Additionally, this large patch produced intense recruitment of Syk-mScarlet at the base of phagosome that was redistributed over the target along with RTX following closure of the phagosome (Fig. 4, C and D), suggesting that the inward-moving forces are relieved upon closure of the phagosome. Quantification of this reorganization demonstrated a drop in the top/bottom ratios for Syk and RTX that were more extensive than for non-treated targets (Fig. 4, C and D). In this case, the degree of RTX pooling at the base of the phagosome closely resembled that of IgG presented on fluid SLB-SBs (compare Fig. 1 B). Together, these findings indicate that the target-cell cytoskeleton partially restricts the macrophage FcγR-induced movement of RTX. Moreover, this finding suggests that in the presence of mobile CD20-RTX, macrophages can engulf target cells without the need for progressive “zippering” of IgG-FcγR complexes at regularly spaced intervals along the target surface. Furthermore, increased mobility of CD20-RTX can lead to additional amplification of signaling that “triggers” greater actin polymerization, contributing to engulfment.

Figure 4.

Disruption of the target cell’s actin cytoskeleton results in dramatic reorganization of RTX by macrophage Fc receptors. (A) Surface reconstruction of LLSM mapping the RTX-AF647 (IgG) or proximal Syk-Scarlet density onto the target-cell surface, relative to the macrophage membrane movements (mNG-mem, gray surface) during ADCP of a Lat-treated WIL-2S cell. (B) Hemispherical coordinates and view rotation on the WIL-2S target cell. (C) RTX (IgG) clustering during ADCP and quantified ratio of within top/bottom ratio. (D) Target proximal Syk-Scarlet distribution during ADCP of the WIL2-S cell with the top/bottom ratio quantified (image volume is 29 μm × 32 μm × 32 μm). To see this figure in color, go online.

An FLM expressing Syk-Scarlet and mNG-Mem was challenged by LatB-treated WIL2-S cell labeled with calcein violet and RTX-AF647. Video duration is 12:56 min (image volume is 29 μm × 32 μm × 32 μm).

Same as Video S5, but without the macrophage membrane. Video duration is 12:56 min (image volume is 29 μm × 32 μm × 32 μm).

Same as Video S5, but without the macrophage membrane, showing only Syk movements. Video duration is 12:56 min (image volume is 29 μm × 32 μm × 32 μm).

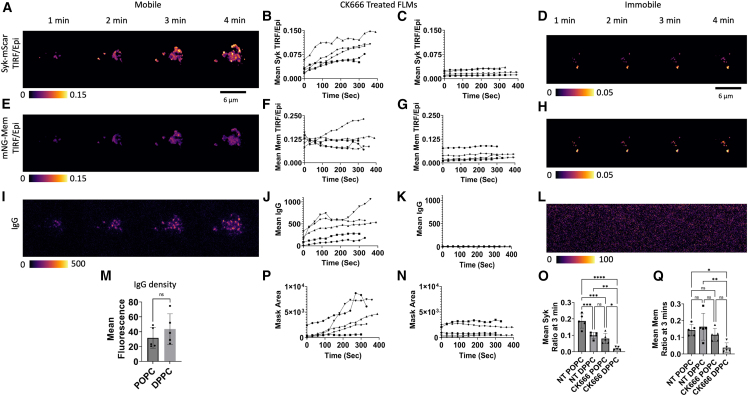

Syk and Arp2/3 are required for the organization of microclusters on surfaces of mobile IgG and cell spreading on both mobile and immobile IgG

We sought to capture a high-resolution view of IgG-FcγR organization on the membrane within the phagocytic synapse using our previously established TIRF-360 microscopy approach, which provides a highly uniform TIRF field that is effectively devoid of interference fringes (37,43,44). SLBs on glass coverslips displaying IgG2a-AF647 docked to DSPE-biotin were created with fluid-phase POPC or gel-phase DPPC phospholipids. FRAP measurements confirmed that the POPC was fluid with a diffusion coefficient for the DSPE-biotin-IgG-AF647 of ∼0.93 μm2 s-1 (Fig. 5, J and K). TIRF microscopy of IgG-AF647 by FcγR was verified by colocalization with a Scarlet-FcγR1 fusion protein (Fig. S3 A). Consistent with our previous work (37), we observed the formation of distinct microclusters at the leading edge that aggregated into patches that moved centripetally inward (Fig. S3 B). These microclusters initially recruited Syk-mScarlet, but then partially lost it as they formed larger patches and the macrophage continued to spread (Fig. 5 A). In contrast, FLMs engaging immobile IgG displayed uniform distribution of Syk (Fig. 5 B). Given the striking recruitment of Syk-mScarlet to the lamellar leading edge and similar observations that Arp2/3 mediates rearrangements of the BCRs and TCRs (52,53), we speculated that Arp2/3 would be important for this organization. Indeed, inhibition with CK-666, a potent Arp2/3 inhibitor (52,67), dramatically altered the organization IgG microclusters and prevented the formation of lamellipodia (Fig. 5 E). CK-666-treated FLMs on immobile IgG surfaces also failed to form lamellipodia (Fig. 5 F). Additionally, CK-666-treated FLMs demonstrated a dramatic defect in spreading compared with untreated FLMs (Fig. 5 I). Thus, Arp2/3 promotes the spatial organization of the IgG-FcγR microcluster formation at the front of the forming pseudopod on mobile IgG surfaces and contributes to engagement of IgG on immobile surfaces. Given the central role of Syk in mediating signaling from the FcγR to actin, we sought to determine its contribution to organizing microclusters in the SLB-IgG system (68,69). Here, we generated FLMs with gene disruptions in Syk using the CRISPR-Cas9 system (31). Syk-KO FLMs formed disorganized contacts with both the POPC and DPPC IgG-presenting bilayers (Fig. 5, G and H) and failed to spread, similar to Arp2/3-inhibited cells (Fig. 5 I). Together, these results suggest that Arp2/3 directs microcluster formation through actin branching, which in turn enables Syk-mediated amplification of IgG-FcγR signaling (quantified below in Figs. 6 and 7). Moreover, mobile IgG facilitates microclustering of IgG-FcγRs to potentiate signaling, driving pseudopod extension and reinforcement through the formation of additional IgG-FcγR binding and microclustering. Thus, like the rearrangement of the BCRs and TCRs, Arp2/3 and Syk are necessary for organizing and rearranging IgG-FcγR microclusters (52,53), which is likely a result of Arp2/3’s contribution to shaping the lamellapod and contributing to new IgG-FcγR ligation.

Figure 5.

TIRF imaging of microcluster organization on mobile IgG surfaces is shaped by Arp2/3-mediated actin branching and Syk-mediated signaling. (A) TIRF imaging of FLM cells expressing Syk-mScarlet spreading on IgG-AF647 mobile POPC SLB. Blue arrow highlights IgG microclusters associated with Syk-mScarlet near the leading edge. Red arrows indicate pooled IgG microclusters that have lost Syk-mScarlet. (B) Immobile (DPPC) SLB displaying IgG show no reorganization (white speckled pattern marks evenly distributed IgG-647, same camera settings as in A, but window leveled to show detail). (E–H) Macrophages treated with CK666 formed initial IgG-AF647 microclusters on mobile POPC bilayers that were disorganized (yellow arrows) (E) or points of contact on uniformly distributed IgG on immobile DPPC bilayers (F) (same camera and laser settings as E, IgG image window leveled separately). Syk-knockout macrophages engaging IgG-AF647 presented on mobile (G) or immobile bilayer (H) cells expressing mNG-Mem. All scale bars represent 10 μm. (I) Quantification of macrophage spreading diameters for all conditions presented above (t-test comparison, error bars denote mean; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.001). (J and K) FRAP analysis of POPC- and DPPC-supported lipid bilayers (white noise surrounding the FRAP spot corresponds to IgG-647 molecules; scale bar, 5 μm). To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 6.

Quantitative analysis of IgG microclustering and Syk recruitment on mobile and immobile surfaces by TIRF/Epi ratio. (A–L) TIRF/Epi ratio images of Syk-mScarlet and quantification for five cells (A–D) as the mean TIRF/Epi ratio per pixel. Similarly, the amount of mNG-Mem probe recruitment was also imaged and quantified (E–H) along with the distribution of IgG-647 (I and K) and mean cell association (J and L). (M) Initial IgG-647 bilayer densities were statistically indistinguishable (t-test, error is SD). (N and O) Cell spreading on mobile (N) relative to immobile (O) bilayers as defined by the area of the mask created on the mNG-Mem image. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 7.

Quantification of IgG microclustering and Syk recruitment in Arp2/3 disabled cells. (A–L) TIRF/Epi ratio images of Syk-mScarlet and quantification for five cells (A–D) as the mean TIRF/Epi ratio per pixel. Similarly, the amount of mNG-Mem probe recruitment was also imaged and quantified (E–H) along with the distribution of IgG-647 (I and K) and mean cell assocation (J and L). (M) Initial IgG-647 bilayer densities were statistically indistinguishable (t-test, error bars are SD). (O and Q) Comparison of the Syk-mScarlet (O) and mNG-mMem (Q) recruitment to mobile (POPC)-supported and immobile (DPPC)-supported lipid bilayers in non-treated (NT) and CK-666-treated cells. (P and Q) Cell spreading on mobile (P) relative to immobile (N) bilayers. To see this figure in color, go online.

Mobile IgG surfaces recruit more Syk than immobile ones in a process mediated by Arp 2/3 membrane engagement

With the finding that pTyr and pSyk were elevated in phagocytic cups engaging mobile SLB-SBs relative to immobile SLB-SBs (Fig. 1, D and E) and the striking recruitment of Syk to RTX-FcγR microclusters during ADCP (Fig. 1), we speculated that these microcluster patches would serve as signal amplification hot spots for signals promoting pseudopod advancement (70). To quantify the recruitment of Syk-mScarlet, we analyzed our TIRF-360 microscopy videos by computing the ratio of the TIRF image to an Epi fluorescence image taken by moving the laser to a subcritical angle (Video S8. Epi/TIRF ratio video of IgG, Syk-mScarlet, and mNG-Mem of a macrophage engaging a mobile (POPC) IgG-SLB surface, Video S9. Epi/TIRF ratio video of IgG, Syk-mScarlet, and mNG-Mem of a macrophage engaging an immobile (DPPC) IgG-SLB surface, Video S10. Epi/TIRF ratio video of IgG, Syk-mScarlet, and mNG-Mem of a CK666-treated macrophage engaging a mobile (POPC) IgG-SLB surface, Video S11. Epi/TIRF ratio video of IgG, Syk-mScarlet, and mNG-Mem of a CK666-treated macrophage engaging an immobile (DPPC) IgG-SLB surface). Thus, the fluorescence signal in the widefield Epi-360 image captures the total fluorescence within the cell due to out-of-focus light contributions to the in-focus TIRF plane, and the TIRF-360 image captures only the fluorescence from molecules within the exponentially decaying TIRF field with a characteristic depth of ∼150 nm (44,71,72). Here, we have quantified the mean TIRF/Epi per pixel as a measure of the fraction of molecules recruited to the contact area. The recruitment of Syk-mScarlet was maximal at the microclusters forming at leading edge of the advancing pseudopod (Fig. 6 A), which corresponded to regions of elevated mNG-Mem (Fig. 6 E), indicating a tight apposition of macrophage membrane, and SLB was associated with IgG-FcγR microclustering (Video S8). Larger patches of IgG-AF647 rapidly accumulated away from the leading edge (Fig. 6 I) where they had lower recruitment of Syk-mScarlet. Quantification of these behaviors on mobile IgG surfaces indicated that Syk-mScarlet was continuously recruited to the interacting surface during spreading (Fig. 6 B), and this generally correlated with the amount of IgG engaged (Fig. 6 J) and cell spreading (Fig. 6 N). On immobile surfaces, the Syk-mScarlet recruitment was far more subdued (Fig. 6, C and D) despite a more homogeneous mNG-Mem signal, suggesting that in the case of immobile IgG there is an overall tighter association of the plasma membrane with the surface (Video S9). Cellular spreading on immobile IgG was slower and generally reached smaller diameter on immobile surfaces (Fig. 6, N and O), consistent with our spreading analysis (Fig. 5 I). Thus, FcγR signaling leads to more Syk recruitment to the contact site on mobile IgG surfaces. There are likely two underpinning mechanisms for the increased Syk recruitment to the mobile IgG surfaces. First, diffusion of IgG from the planar bilayer significantly increases the amount of FcγR-IgG complexes, and second, the increased spreading rate of these cells drives the formation of additional FcγR-IgG binding events. This effect is likely of physiological relevance for the initial interaction between the macrophage and target cell when initial pooling of diffusing IgG via interaction with FcγR may overcome inhibitory phosphatase signals such as in the case of actin-disrupted target cells. Additionally, the mobile surface affords intense and highly localized grouping of the IgG-FcγR at the leading edge of the phagosome promoting significant recruitment of Syk (Fig. 6 A), reinforcing actin polymerization and pseudopod extension. The events imaged on a freely mobile bilayer may exaggerate this effect; however, the overall microclustering and patching phenomena is highly like that observed in our lattice light-sheet and confocal imaging (Figs. 1 A and 2, Videos S3 and S4), suggesting that these events contribute to the crossing of activating thresholds needed to complete ADCP.

Video duration is 4 min (image panels are 16.5 μm × 13 μm).

Video duration is 4 min (image panels are 14.5 μm × 14.5 μm).

Video duration is 4 min (image panels are 12 μm × 12 μm).

Video duration is 4 min (image panels are 10 μm × 10 μm).

Arp2/3 contributes to the organization and formation of leading-edge IgG-FcγR microclusters

Given the striking cell-spreading defect that we observed in Arp2/3-inhibited macrophages and the observation that Syk was most strongly recruited to IgG microclusters at the leading edge of the forming pseudopod, we quantified the strength of these defects using our TIRF-Epi imaging approach. Indeed, microclusters were able to form in CK-666-treated FLMs, and these clusters recruited Syk-mScarlet (Fig. 7, Video S10). However, these clusters were disorganized and displayed diminished Syk recruitment relative to that observed in non-treated FLMs (compare Fig. 7, A and B with Fig. 6, A and B). This defect was even more pronounced when FLMs were presented with immobile IgG surfaces, resulting in minimal Syk recruitment (Video S11). Aggregate comparisons of Syk recruitment to the contact site (Fig. 7 N) demonstrated that Syk was maximally recruited to mobile IgG surfaces and secondarily to immobile IgG surfaces, and that Arp2/3 function was required in both cases. We conclude that Arp2/3 function is important for the formation of a pseudopod and promoting the engagement of FcγRs with IgG in all cases, and that on mobile surfaces Arp2/3 retains the formation of FcγR-IgG microclusters at the leading edge to promote Syk recruitment at the leading edge.

Discussion

The finding that CD20-RTX-FcγRs undergo spatial rearrangements during ADCP and that these arrangements potentiate signaling has significant ramifications for the development of cell-depleting therapeutic antibodies and immunomodulators. Specifically, this work implies that there is more to consider in the activation of FcγRs than simply a requirement for high densities of IgG to increase the lateral density of IgG-FcγRs on the macrophage plasma membrane to initiate kinase cascades and recruit Syk (73). For immobile IgG, high densities will be needed to increase in local density of IgG-FcγRs above inhibitory thresholds to sustain actin-mediated advance of the pseudopod in zippering fashion along this surface by creating new contacts (32,33,34,35,74). While the zipper model likely holds for many pathogen targets displaying immobile IgG, including gram-positive bacteria and yeast, cellular host targets with fluid bilayers are likely to behave differently. While other mechanical properties of the target, including shape, size, and stiffness, can influence phagocytic efficiency (75,76), our results demonstrate that surface mobility of the phagocytic ligand is another important factor that has particular relevance for ADCP of host cells. Moving forward, an important question will be to delineate how phagocytic ligand surface mobility intersects with these other physical parameters affecting phagocytic efficacy. Additionally, local microclustering events of IgG on lymphoma cells and mobile surfaces were associated with maximal Syk recruitment, suggesting an important role in signal amplification. This process is highly consistent with the observation that grouping of IgG into smaller patches by DNA origami promoted phagocytosis of beads, whereas the same number distributed over the target could not (30). Moreover, we observed that the extent of clustering was counteracted by the target cell’s cytoskeleton, with Lat-treated targets resulting in much of the available RTX accumulating at the base of the phagosome and a modest improvement in phagocytic efficiency in two of the three target-cell types tested. That a macrophage can form phagosomes even when the majority of IgG is pooled on one side of the target cell suggests that the “trigger model” still contributes via longer-range signaling to provide super-threshold signaling and extensive actin polymerization and supports successful ADCP. More work is needed to understand how IgG and antigen reorganization contributes to cell-depleting therapeutic antibody efficacy (34).

The dramatic short- and long-range reorganization of CD20-RTX-FcγR complexes during ADCP suggests a new model for phagocytosis that specifically accounts for signal amplification at microclusters acting as a trigger, such as the TCR and BCR, by producing pro-phagocytic signals that exceed local inhibitory thresholds (70,77). Most notably, the formation of microclusters followed by pooling of RTX-FcγRs toward the base of phagocytic cup is highly reminiscent of the stages of immune synapse formation in T cells (78) and pooling of B cell receptors (52). Unlike the TCR immune synapse, which accumulates receptors into a stabilized structure, the IgG-FcγR clusters and patches tend to remain more disbursed, owing to restriction by the target-cell actin, and become nearly uniformly distributed over the completed phagosome, suggesting a sliding movement that is distinct from the TCR and BCR and retaining a key aspect of the zipper model (Fig. 2 and Video S2). Importantly, and like the TCR and BCR, our findings suggest that the formation of IgG-FcγR microclusters support phosphorylation that exceeds constitutive dephosphorylation by CD45 and CD148, which may be excluded from these tight-fitting contact sites (29,78,79). Thus, the surface mobility of the antigen should be considered when developing therapeutic antibodies. A direct implication of this finding is that target cells with dense or active actin networks that restrict the mobility of surface antigens are likely to be increasingly resistant to ADCP, requiring higher densities of therapeutic antibody. In corollary, treatments that depolymerize or somehow disrupt actin corralling of surface antigens on target cells may act as adjuvants for antibody therapies acting through ADCP.

While the exact cellular mechanisms by which macrophages promote microclustering and reorganization of the IgG-FcγR complexes are still unclear, this study implicates a positive feedback loop involving Arp2/3 and Syk. Arp2/3-mediated nucleation and actin branching, like that observed in spatial patterning of the BCR (52) and TCR (53,80), likely plays a critical role in facilitating pseudopod advancement and structure at the target interface which, in turn, drives IgG-FcγR binding events. The precise mechanism that retains these microclusters at the leading edge prior to their pooling and retrograde movement will be an important future direction. Specifically, the contributions of membrane tension, localized myosin activity, and remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton are likely contribute to the dynamics of microcluster formation and pooling dynamics during ADCP (54,66,81). Likewise, the transition of IgG-FcγRs into larger patches may involve other actin-remodeling factors that may mediate the formation of podosome-like structures (82). These findings predict that Syk signaling to Arp2/3 through enhanced activation of the Arp2/3 nucleators WAVE2 and WASP should also be strong predictors of the efficacy of ADCP.

Author contributions

S.J. and B.R.F. acquired and analyzed data and co-wrote the manuscript. N.M.C., N.P.D.N., and E.M.B. acquired and analyzed data. J.G.K. designed plasmid constructs and generated FLM cell lines. Y.M.L. developed the analysis for the LLSM data. R.B.A. built the LLSM and analysis cluster and provided supervision. B.L.S. planned experiments and assisted with analysis. A.D.H. planned experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the South Dakota Board of Regents through BioSNTR SDRIC and the SDBOR FY20 collaborative research award “IMAGEN: Biomaterials in South Dakota.” Additional funding was provided by the National 388 Science Foundation through research award CNS-1626579 “MRI: Development of a Scalable High-Performance Computing System in Support of the Lattice Light-Sheet Microscope (LSSM) for Real-Time Three-Dimensional Imaging of Living Cells.” This publication has been made possible in part by CZI grant DAF2019-198104 and grant at https://doi.org/10.37921/428626xtaktp from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative DAF, an advised fund of Silicon Valley Community Foundation (funder DOI 10.13039/100014989). Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number U01AI148153 and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number P20GM135008. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The data visualization and analyses were performed using UCSF ChimeraX, developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, with support from National Institutes of Health R01-GM129325 and the Office of Cyber Infrastructure and Computational Biology, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The LLSM referenced in this research was developed under license from Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Janelia Farms Research Campus (“Bessel Beam” patent applications 13/160,492 and 13/844,405).

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Editor: Anne Kenworthy.

Footnotes

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2024.01.036.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Ackerman M.E., Dugast A.S., et al. Alter G. Enhanced phagocytic activity of HIV-specific antibodies correlates with natural production of immunoglobulins with skewed affinity for FcγR2a and FcγR2b. J. Virol. 2013;87:5468–5476. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03403-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshall M.J.E., Stopforth R.J., Cragg M.S. Therapeutic Antibodies: What Have We Learnt from Targeting CD20 and Where Are We Going? Front. Immunol. 2017;8:1245. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sips M., Krykbaeva M., et al. Alter G. Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis in tissues as a potent mechanism for preventive and therapeutic HIV vaccine strategies. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9:1584–1595. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordan S., Biburger M., Nimmerjahn F. bIgG time for large eaters: monocytes and macrophages as effector and target cells of antibody-mediated immune activation and repression. Immunol. Rev. 2015;268:52–65. doi: 10.1111/imr.12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He W., Chen C.J., et al. Tan G.S. Alveolar macrophages are critical for broadly- reactive antibody-mediated protection against influenza A virus in mice. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:846. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00928-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mullarkey C.E., Bailey M.J., et al. Palese P. Broadly Neutralizing Hemagglutinin Stalk-Specific Antibodies Induce Potent Phagocytosis of Immune Complexes by Neutrophils in an Fc-Dependent Manner. mBio. 2016;7:1–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01624-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alvey C., Discher D.E. Engineering macrophages to eat cancer: from “marker of self” CD47 and phagocytosis to differentiation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2017;102:31–40. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4RI1216-516R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahal L.N., Dou L., et al. Beers S.A. STING Activation Reverses Lymphoma-Mediated Resistance to Antibody Immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2017;77:3619–3631. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-16-2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kao D., Danzer H., et al. Nimmerjahn F. A Monosaccharide Residue Is Sufficient to Maintain Mouse and Human IgG Subclass Activity and Directs IgG Effector Functions to Cellular Fc Receptors. Cell Rep. 2015;13:2376–2385. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gül N., van Egmond M. Antibody-Dependent Phagocytosis of Tumor Cells by Macrophages: A Potent Effector Mechanism of Monoclonal Antibody Therapy of Cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75:5008–5013. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiskopf K., Weissman I.L. Macrophages are critical effectors of antibody therapies for cancer. mAbs. 2015;7:303–310. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2015.1011450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Church A.K., VanDerMeid K.R., et al. Zent C.S. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody-dependent phagocytosis of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia cells by autologous macrophages. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2016;183:90–101. doi: 10.1111/cei.12697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaughan A.T., Chan C.H.T., et al. Cragg M.S. Activatory and Inhibitory Fcγ Receptors Augment Rituximab-mediated Internalization of CD20 Independent of Signaling via the Cytoplasmic Domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:5424–5437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.593806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor R.P., Lindorfer M.A. Fcγ-receptor–mediated trogocytosis impacts mAb-based therapies: historical precedence and recent developments. Blood. 2015;125:762–766. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beers S.A., French R.R., et al. Cragg M.S. Antigenic modulation limits the efficacy of anti-CD20 antibodies: implications for antibody selection. Blood. 2010;115:5191–5201. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-263533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matlung H.L., Babes L., et al. van den Berg T.K. Neutrophils Kill Antibody-Opsonized Cancer Cells by Trogoptosis. Cell Rep. 2018;23:3946–3959.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Velmurugan R., Challa D.K., et al. Ward E.S. Macrophage-Mediated Trogocytosis Leads to Death of Antibody-Opsonized Tumor Cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2016;15:1879–1889. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barkal A.A., Weiskopf K., et al. Maute R.L. Engagement of MHC class I by the inhibitory receptor LILRB1 suppresses macrophages and is a target of cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Immunol. 2018;19:76–84. doi: 10.1038/s41590-017-0004-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon S.R., Maute R.L., et al. Weissman I.L. PD-1 expression by tumour-associated macrophages inhibits phagocytosis and tumour immunity. Nature Publishing Group. 2017;545:495–499. doi: 10.1038/nature22396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piccione E.C., Juarez S., et al. Majeti R. A bispecific antibody targeting CD47 and CD20 selectively binds and eliminates dual antigen expressing lymphoma cells. mAbs. 2015;7:946–956. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2015.1062192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chao M.P., Alizadeh A.A., et al. Majeti R. Anti-CD47 antibody synergizes with rituximab to promote phagocytosis and eradicate non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cell. 2010;142:699–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang H., Sun Y., et al. Gao Y. CD47/SIRPα blocking peptide identification and synergistic effect with irradiation for cancer immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2020;8 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willingham S.B., Volkmer J.P., et al. Weissman I.L. The CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPa) interaction is a therapeutic target for human solid tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:6662–6667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121623109/-/dcsupplemental. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrissey M.A., Williamson A.P., et al. Vale R.D. Chimeric antigen receptors that trigger phagocytosis. eLife. 2018;7:e36688. doi: 10.7554/eLife.36688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodridge H.S., Reyes C.N., et al. Underhill D.M. Activation of the innate immune receptor Dectin-1 upon formation of a ‘phagocytic synapse’. Nature. 2011;472:471–475. doi: 10.1038/nature10071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodridge H.S., Underhill D.M., Touret N. Mechanisms of Fc Receptor and Dectin-1 Activation for Phagocytosis. Traffic. 2012;13:1062–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrews N.L., Pfeiffer J.R., et al. Lidke D.S. Small, mobile FcepsilonRI receptor aggregates are signaling competent. Immunity. 2009;31:469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwartz S.L., Cleyrat C., et al. Lidke D.S. Differential mast cell outcomes are sensitive to FcεRI-Syk binding kinetics. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2017;28:3397–3414. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E17-06-0350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bakalar M.H., Joffe A.M., et al. Fletcher D.A. Size-Dependent Segregation Controls Macrophage Phagocytosis of Antibody-Opsonized Targets. Cell. 2018;174:131–142.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kern N., Dong R., et al. Morrissey M.A. Tight nanoscale clustering of Fcγ receptors using DNA origami promotes phagocytosis. eLife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.68311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bailey E.M., Choudhury A., et al. Hoppe A.D. Engineered IgG1-Fc Molecules Define Valency Control of Cell Surface Fcγ Receptor Inhibition and Activation in Endosomes. Front. Immunol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.617767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffin F.M., Griffin J.A., Silverstein S.C. Studies on the mechanism of phagocytosis. II. The interaction of macrophages with anti-immunoglobulin IgG-coated bone marrow-derived lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1976;144:788–809. doi: 10.1084/jem.144.3.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffin F.M., Griffin J.A., et al. Silverstein S.C. Studies on the mechanism of phagocytosis. I. Requirements for circumferential attachment of particle-bound ligands to specific receptors on the macrophage plasma membrane. J. Exp. Med. 1975;142:1263–1282. doi: 10.1084/jem.142.5.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swanson J.A., Hoppe A.D. The coordination of signaling during Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2004;76:1093–1103. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0804439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaumouillé V., Waterman C.M. Physical Constraints and Forces Involved in Phagocytosis. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:1097. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pham T., Mero P., Booth J.W. Dynamics of macrophage trogocytosis of rituximab-coated B cells. PLoS ONE. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin J., Kurilova S., et al. Hoppe A.D. TIRF imaging of Fc gamma receptor microclusters dynamics and signaling on macrophages during frustrated phagocytosis. BMC Immunol. 2016;17:5–9. doi: 10.1186/s12865-016-0143-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matlawska-Wasowska K., Ward E., et al. Wilson B.S. Macrophage and NK-mediated killing of precursor-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells targeted with a-fucosylated anti-CD19 humanized antibodies. Leukemia. 2013;27:1263–1274. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saphire E.O., Schendel S.L., et al. Viral Hemorrhagic Fever Immunotherapeutic Consortium Systematic analysis of monoclonal antibodies against Ebola Virus GP defines features that contribute to protection. Cell. 2018;174:938–952.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gunn B.M., Yu W.H., et al. Alter G. A Role for Fc Function in Therapeutic Monoclonal Antibody-Mediated Protection against Ebola Virus. Cell host & microbe. 2018;24:221–233.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.STEWART S.A., Dykxhoorn D.M., et al. Novina C.D. Lentivirus-delivered stable gene silencing by RNAi in primary cells. Rna. 2003;9:493–501. doi: 10.1261/rna.2192803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sancak Y., Peterson T.R., et al. Sabatini D.M. The Rag GTPases Bind Raptor and Mediate Amino Acid Signaling to mTORC1. Science. 2008;320:1496–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.1157535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scott B.L., Sochacki K.A., et al. Hoppe A.D. Membrane bending occurs at all stages of clathrin-coat assembly and defines endocytic dynamics. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:419. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-02818-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin J., Hoppe A.D. Uniform Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence Illumination Enables Live Cell Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer Microscopy. Microsc. Microanal. 2013;19:350–359. doi: 10.1017/S1431927612014420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., et al. Cardona A. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bray M.-A., Carpenter A.E. CellProfiler Tracer: exploring and validating high-throughput, time-lapse microscopy image data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2015;16:369. doi: 10.1186/s12859-015-0759-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quinn S.E., Huang L., et al. Scott B.L. The structural dynamics of macropinosome formation and PI3-kinase-mediated sealing revealed by lattice light sheet microscopy. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.12.01.390195. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lambert T., Shao L., Volker . tlambert03/LLSpy: v0.4.8. 2019. Version 0.4.8. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., et al. Ferrin T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 2021;30:70–82. doi: 10.1002/pro.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Virtanen P., Gommers R., et al. SciPy 1.0 Contributors SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods. 2020;17:261–272. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0686-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rougé L., Chiang N., et al. Rohou A. Structure of CD20 in complex with the therapeutic monoclonal antibody rituximab. Science. 2020;367:1224–1230. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz9356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bolger-Munro M., Choi K., et al. Gold M.R. Arp2/3 complex-driven spatial patterning of the BCR enhances immune synapse formation, BCR signaling and B cell activation. eLife. 2019;8:e44574. doi: 10.7554/eLife.44574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumari S., Depoil D., et al. Dustin M.L. Actin foci facilitate activation of the phospholipase C-γ in primary T lymphocytes via the WASP pathway. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.04953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beemiller P., Jacobelli J., Krummel M.F. Integration of the movement of signaling microclusters with cellular motility in immunological synapses. Nat. Immunol. 2012;13:787–795. doi: 10.1038/ni.2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen B.-C., Legant W.R., et al. Betzig E. Lattice light-sheet microscopy: imaging molecules to embryos at high spatiotemporal resolution. Science. 2014;346 doi: 10.1126/science.1257998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tomishige M., Sako Y., Kusumi A. Regulation Mechanism of the Lateral Diffusion of Band 3 in Erythrocyte Membranes by the Membrane Skeleton. J. Cell Biol. 1998;142:989–1000. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.4.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kusumi A., Suzuki K.G.N., et al. Fujiwara T.K. Hierarchical mesoscale domain organization of the plasma membrane. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011;36:604–615. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wong H.S., Jamouillé V., et al. Robinson L.A. Chemokine signaling enhances CD36 responsiveness toward oxidized low-density lipoproteins and accelerates foam cell formation. Cell Rep. 2016;26:2859–2871. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ostrowski P.P., Grinstein S., Freeman S.A. Diffusion Barriers, Mechanical Forces, and the Biophysics of Phagocytosis. Dev. Cell. 2016;38:135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rudnicka D., Oszmiana A., et al. Davis D.M. Rituximab causes a polarization of B cells that augments its therapeutic function in NK-cell–mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Blood. 2013;121:4694–4702. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-482570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilson C.A., Tsuchida M.A., et al. Theriot J.A. Myosin II contributes to cell-scale actin network treadmilling through network disassembly. Nature. 2010;465:373–377. doi: 10.1038/nature08994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lou J., Low-Nam S.T., et al. Hoppe A.D. Delivery of CSF-1R to the lumen of macropinosomes promotes its destruction in macrophages. J. Cell Sci. 2014;127:5228–5239. doi: 10.1242/jcs.154393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Freeman S.A., Grinstein S. Phagocytosis: receptors, signal integration, and the cytoskeleton. Immunol. Rev. 2014;262:193–215. doi: 10.1111/imr.12212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Freeman S.A., Vega A., et al. Grinstein S. Transmembrane Pickets Connect Cyto- and Pericellular Skeletons Forming Barriers to Receptor Engagement. Cell. 2018;172:305–317.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Imbert P.R., Saric A., et al. Freeman S.A. An Acquired and Endogenous Glycocalyx Forms a Bidirectional “Don’t Eat” and “Don’t Eat Me” Barrier to Phagocytosis. Curr. Biol. 2021;31:77–89.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.09.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vorselen D., Barger S.R., et al. Krendel M. Phagocytic ‘teeth’ and myosin-II ‘jaw’ power target constriction during phagocytosis. eLife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.68627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hetrick B., Han M.S., et al. Nolen B.J. Small Molecules CK-666 and CK-869 Inhibit Actin-Related Protein 2/3 Complex by Blocking an Activating Conformational Change. Chem. Biol. 2013;20:701–712. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Flannagan R.S., Harrison R.E., et al. Grinstein S. Dynamic macrophage “probing” is required for the efficient capture of phagocytic targets. J. Cell Biol. 2010;191:1205–1218. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jaumouillé V., Farkash Y., et al. Grinstein S. Actin Cytoskeleton Reorganization by Syk Regulates Fcγ Receptor Responsiveness by Increasing Its Lateral Mobility and Clustering. Dev. Cell. 2014;29:534–546. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang Y., Hoppe A.D., Swanson J.A. Coordination of Fc receptor signaling regulates cellular commitment to phagocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:19332–19337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008248107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hoppe A.D., Shorte S.L., et al. Heintzmann R. Three-dimensional FRET reconstruction microscopy for analysis of dynamic molecular interactions in live cells. Biophys. J. 2008;95:400–418. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.125385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]