Abstract

Background

Standard assessment and management protocols exist for first episode psychosis (FEP) in high income countries. Due to cultural and resource differences, these need to be modified for application in low-and middle-income countries.

Aims

To assess the applicability of standard assessment and management protocols across two cohorts of FEP patients in North and South India by examining trajectories of psychopathology, functioning, quality of life and family burden in both.

Method

FEP patients at two sites (108 at AIIMS, North India, and 115 at SCARF, South India) were assessed using structured instruments at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months. Standard management protocols consisted of treatment with antipsychotics and psychoeducation for patients and their families. Generalised estimating equation (GEE) modelling was carried out to test for changes in outcomes both across and between sites at follow-up.

Results

There was an overall significant improvement in both cohorts for psychopathology and other outcome measures. The trajectories of improvement differed between the two sites with steeper improvement in non-affective psychosis in the first three months at SCARF, and affective symptoms in the first three months at AIIMS. The reduction in family burden and improvement in quality of life were greater at AIIMS than at SCARF during the first three months.

Conclusions

Despite variations in cultural contexts and norms, it is possible to implement FEP standard assessment and management protocols in North and South India. Preliminary findings indicate that FEP services lead to significant improvements in psychopathology, functioning, quality of life, and family burden within these contexts.

Keywords: FEP, First episode psychosis, India, Psychopathology, Functioning, Family burden, Quality of life

1. Introduction

Psychotic disorders cause significant disability in individuals, resulting in heavy burden on families and society. Long-term disability and poor outcomes can be mitigated by identification and management in the early stages of psychosis, especially during first episode psychosis (FEP). Studies suggests that long-term disability can be prevented by intervening early in the course of the psychoses as the initial stages are critical in predicting the outcome in terms of quality of life, functioning, and negative symptoms (Salazar de Pablo et al., 2024). Therefore, the patients with FEP have better chances of recovery in comparison to persons with chronic illness (McGorry et al., 2007).

Early treatment for FEP is an important strategy for reducing the disability and early intervention services (EIS) have been established in high income countries (HIC) based (Singh et al., 2015). A study conducted in Melbourne in individuals with FEP showed that psychosocial interventions with placebo are not inferior to psychosocial interventions with antipsychotics (Francey et al., 2020). This study indicated that certain young individuals experiencing FEP with a short duration of untreated psychosis may experience improvement in their functioning and achieve symptom remission without the use of antipsychotic medication, provided they receive psychosocial interventions and comprehensive case management.

Currently, the majority of patients with FEP residing in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs), such as India, receive inadequate care due to the limited mental health resources (Rathod et al., 2017, Shiers and Lester, 2004, Sudharsanan et al., 2018). Multicentric studies in India carried out in the 1970s-80s under the auspices of the World Health Organisation and the Indian Council of Medical Research demonstrated that individuals with acute-onset FEP remitted at 2 and 5 years of follow-up (Verghese et al., 1989, Varma et al., 1997; Malhotra et al., 2007). However, these studies examined only the sociodemographic and clinical aspects, excluding the management-related aspects, hence they were essentially not early intervention studies. Furthermore, questions remain in comparing the methodology across different countries and cultures (Kulhara et al., 2009).

Research gaps in early intervention for psychosis in India include insufficient controlled studies, limited literature on feasibility, and a need for comprehensive understanding. Systemic constraints, limited resources, and manpower disparities hinder successful delivery, interfering with outcome (Keshavan et al., 2010). Although there are initiatives to create healthcare models for FEP in LMICs to provide affordable and efficient early care, implementation of early intervention services (EIS) remains a challenge (Chatterjee et al., 2009). Specific obstacles include a lack of qualified mental health professionals, fragmented healthcare systems (Chokshi et al., 2016), limited resources for research and implementation (Lamers et al., 2006, Singh, 2015), and variation in utilisation of and accessibility to healthcare services across different regions in India with southern states having better indices (Kumar and Rani, 2019). A systematic review of early intervention in psychosis services in LMIC revealed very few studies, particularly with non-pharmacological approaches and had weaker methodology. However, it was concluded that early intervention can be provided in LMIC with cultural adaptation and available resources (Farooq et al., 2024). It may thus be feasible to use principles and therapeutic components of EIS programmes developed in HICS into locally contextualised mental healthcare in LMICs.

In the current study, we aimed to assess the applicability of standard FEP assessment and management protocols across two culturally diverse cohorts of FEP patients in North (All India Institute of Medical Sciences, i.e., AIIMS, New Delhi) and South (Schizophrenia Research Foundation, i.e., SCARF, Chennai) India by examining trajectories of psychopathology, functioning, quality of life and family burden in both. With the help of this study, we aimed at addressing gaps in controlled studies, sparse literature on feasibility, and systemic constraints in the Indian mental health system. By comparing FEP management in different cultural contexts, the research seeks to contribute valuable insights into improving early intervention strategies for psychotic disorders in India.

Specifically, we addressed the following research questions: (i) Can a standard FEP assessment and management protocol be applied across two settings in North and South India? (ii) Does a standard FEP assessment and management protocol led to improvement in symptoms, functioning, quality of life, and family burden? (iii) Do trajectories of the outcome variables differ across the two sites?

2. Methods

The current study is part of the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Global Health Group: The Warwick-India-Canada (WIC) programme. The WIC programme had five work packages and the current study comprised work package (WP) – 2. WP-2 aimed at developing assessment and management protocol based on evidence-based intervention developed in UK and Canada, and findings from WP-1 on partnerships and stakeholders’ engagement. The goal of WP-2 was to develop psychosocial care model for patients with FEP tailored to local context, and assess their short and medium-term outcomes. Further details on the programme and study methods have been described previously (Singh et al., 2021). The study was approved by the University of Warwick’s Biomedical and Scientific Research Ethics Committee and the local ethical committees. All study participants provided written informed consent.

2.1. Treatment settings

The study was carried out at two sites: All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi (https://www.aiims.edu) and Schizophrenia Research Foundation (SCARF), Chennai (https://scarfindia.org). AIIMS, New Delhi is a premier public funded tertiary care general hospital and medical school with catchment area spread over the mega city of Delhi with a population of over 25 million, and north, east, and west India. The department of psychiatry is one of 50 departments in the hospital, providing outpatient and inpatient care for all psychiatric disorders besides running consultation-liaison, addiction, emergency and community clinical services. The department also provides education to medical and nursing undergraduates and runs postgraduate courses in psychiatry and addiction psychiatry. SCARF is based in Chennai (a population of 7 million) and is a mental health focussed non-profit, non-governmental, WHO collaborating centre. It has a FEP program, pioneered research in schizophrenia and psychotic illnesses and provides holistic clinical care to patients with psychotic disorders.

At AIIMS, participants were recruited from 1st Aug 2019–31 st December 2020. At SCARF, participants were recruited from 1st April 2018–31 st December 2020.

2.2. Selection criteria

FEP has been defined differently in various studies (Breitborde et al., 2009). In the current study, FEP was defined as patients suffering their first episode of psychosis (affective or non-affective) and seeking treatment for their psychotic symptoms for the first time, which was defined as having taken antipsychotic medication for fewer than 30 days prior to recruitment in the study, as also observed in Prevention and Early intervention Programme for Psychoses (PEPP) (Malla et al., 2003).

All patients between aged 16–45 presenting with psychotic symptoms, diagnosed with any of the following (as per ICD-10): schizophrenia (F20), persistent delusional disorder (F22), acute and transient psychotic disorders (F23), schizoaffective disorder (F25), other and unspecified psychosis (F28 & F29), manic episode-severe with psychotic symptoms (F30.2), and severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms (F32.3) were recruited. Individuals with pervasive developmental disorder, specific learning disability and mental retardation (ascertained on history and clinical examination), comorbid substance use in a dependent pattern (except tobacco), organic brain damage or epilepsy, were excluded.

Caregivers were included if they were staying with the patient, and fulfilled any three of the following criteria: being a parent/spouse, having most frequent contact with the patient, helping to support the patient financially, had most frequently been a participant in patient’s treatment, or could be contacted by treatment staff in case of an emergency (Maji et al., 2012).

2.3. Assessment protocol

A semi-structured proforma was used at baseline for assessing sociodemographic and clinical details including age, sex, education, marital status, occupation, monthly income, religion, place of residence and contact details.

Psychopathology was assessed using the following instruments at baseline, 3, 6, and 12-month follow-up: Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (Andreasen, 1984), Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (Andreasen, 1989), Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (Young et al., 1978), and Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery and Asberg, 1979).

Functioning was assessed with two scales: Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (Hall, 1995), and Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). GAF is a scoring system for mental health professionals to subjectively rate the social, occupational, and psychological functioning of an individual in their daily lives. SOFAS is a clinician-rated 100-point scale used to assess an individual’s level of social and occupational functioning along a continuum ranging from optimum functioning to important functional impairment. It has been validated in Indian settings (Saraswat et al., 2006).

Quality of life was assessed with the EQ-5D-5L, a simple generic health-related quality of life (HRQoL) instrument for the measurement, description and valuation of health (EuroQol Research Foundation, 2019). EQ-5D-5L consists of two pages: the descriptive system and the Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS). The descriptive system comprises five domains (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/ discomfort, anxiety/depression), each one with five possible levels (no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems and unable to do/ extreme problems). This scale has also been validated in Indian settings recently (Jyani et al., 2022).

The Family Burden Interview Schedule (FBIS) was used to assess caregiver burden (Pai and Kapur, 1981). Both subjective and objective domains were assessed. FBIS is developed and validated in Indian settings with high inter-rater reliability.

Inter-rater reliability between sites was assessed for all scales in five randomly selected cases. A relatively high degree of agreement was achieved with intra-class correlation coefficients ranging between 0.89 and 0.97.

2.4. Management protocol

Management protocol was based on standard treatment guidelines as followed locally as well as a consensus among the investigators based on the facilities available. Patients with FEP were treated using standard management protocols including antipsychotics and psychosocial interventions. Oral antipsychotics in lowest possible effective dose were used taking into account effectiveness, tolerability, and patient preference. Choice of antipsychotic medication was made jointly by the service user and healthcare professional. Psychosocial interventions were mainly in form of patient and family psychoeducation. Psychoeducation booklets for patients and caregivers were developed based on extant literature and taking elements from early intervention services (Singh, 2015). Patient psychoeducation included information about illness, benefits and risks of antipsychotics and the need for adherence, identification of warning signs and relapse, lifestyle changes if needed, risk of illicit substance and alcohol use, and how to initiate functional recovery. Family psychoeducation included ways of coping with crises, interventions to reduce high expressed emotions, and avoiding caregiver burnout.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data was analysed using SPSS version 21. The Shapiro-Wilk test for normality was used. Since the majority of the data was not normally distributed, non-parametric tests were applied. Generalised estimating equations (GEEs) were carried out incorporating time, site, and time-site interaction as fixed effects to examine trajectories of outcomes over time. GEE is a method of modelling longitudinal clustered data with non-normal distribution, which takes into account missing data and controls for baseline differences between sites (Ghisletta and Spini, 2004). A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For post-hoc pairwise comparisons at different time-points, Wilcoxon-signed rank test was used after adjusting p-value for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni’s corrections).

3. Results

3.1. Recruitment and follow-up at two sites

It was proposed to have sample of at least 100 patients from each centre. We recruited 108 (AIIMS, North India) and 115 (SCARF, South India) patients. The cumulative percentage loss to follow-up was 43.5 % at AIIMS and 10.4 % at SCARF. There were no significant differences in the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients retained and those lost to attrition (supplementary material).

3.1.1. Baseline characteristics of patients: similarities and differences across two sites

Table 1 presents a comparison of socio-demographic and clinical characteristics between sites at baseline.

Table 1.

Comparison of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants at two sites at baseline.

| Characteristics | Total (n = 223) Mean (SD) Frequency (%) |

North India (n= 108) Mean (SD) Frequency (%) |

South India (n= 115) Mean (SD) Frequency (%) |

Comparison between sites χ2/ Mann Whitney U (p value) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 27.7 (7.8) | 27.1 (7.8) | 28.3 (7.8) | 5752.5 (0.341) | |

| Gender | Male | 116 (52.1 %) | 63 (58.3 %) | 53 (46.1 %) | 3.35 (0.045) * |

| Female | 107 (27.9 %) | 45 (41.7 %) | 62 (53.9 %) | ||

| Marital status | Married | 92 (41.3 %) | 40 (37.0 %) | 52 (45.2 %) | 2.381 (0.304) |

| Unmarried | 122 (54.7 %) | 62 (57.4 %) | 60 (52.2 %) | ||

| Separated | 9 (40.3 %) | 6 (5.6 %) | 3 (2.6 %) | ||

| Education | Up to 10th | 114 (51,1 %) | 100 (92.6 %) | 14 (12.2 %) | 144.15 (< 0.001)*** |

| Above 10th | 109 (48.9 %) | 8 (7.4 %) | 101 (87.8 %) | ||

| Occupation | Employed | 85 (38.1 %) | 37 (34.3 %) | 48 (41.7 %) | 19.653 (< 0.001)*** |

| Homemaker | 44 (19.7 %) | 16 (14.8 %) | 28 (24.3 %) | ||

| Student | 57 (25.5 %) | 25 (23.1 %) | 32 (27.8 %) | ||

| Unemployed | 37 (16.6 %) | 30 (27.8 %) | 7 (6.1 %) | ||

| Family income | <10,000 | 28 (12.6 %) | 26 (24.1 %) | 2 (1.7 %) | 25.437 (< 0.001)*** |

| 10,000–20,000 | 91 (40.8 %) | 37 (34.3 %) | 54 (46.9 %) | ||

| >20,000 | 104 (46.6 %) | 45 (41.7 %) | 59 (51.3 %) | ||

| Residence | Urban | 183 (82.1 %) | 68 (62.9 %) | 115 (100 %) | 51.902# < 0.001)*** |

| Rural | 40 (17.9 %) | 40 (37.0 %) | 0 (0) | ||

| Distance from centre (km) | 111 (290.5) | 219.6 (388.7) | 9.1 (29.5) | 1130.5 (< 0.001)*** | |

| Family history of psychiatric illness | 57 (25.6 %) | 33 (30.6 %) | 24 (20.9 %) | 2.746 (0.066) | |

| ICD-10 diagnosis | F20–29 | 194 (86.9 %) | 87 (80.6 %) | 107 (93.0 %) | 7.677 (0.005)** |

| F30–39 | 29 (13.0 %) | 21 (19.4 %) | 8 (6.9 %) | ||

| Age of onset (years) | 27.2 (7.8) | 26.3 (7.9) | 28 (7.7) | 5463.5 (0.121) | |

| Total duration (months) | 10.3 (14.4) | 12.2 (18.3) | 8.5 (9) | 5665 (0.257) | |

| SAPS Global | 7.9 (3.6) | 7.9 (4.1) | 7.9 (3.2) | 6074 (0.776) | |

| SANS Global | 9.5 (5.7) | 9.7 (5.8) | 9.2 (5.6) | 5904 (0.524) | |

| YMRS | 10 (10.6) | 16 (10.1) | 4.3 (7.6) | 1537.5 (< 0.001)*** | |

| MADRS | 9.2 (9.2) | 13.6 (9.2) | 5.1 (7.2) | 2419.5 (< 0.001)*** | |

| GAF | 44.9 (16.3) | 54.2 (17.1) | 36.1 (9) | 2271.5 (< 0.001)*** | |

| SOFAS | 45.9 (16.4) | 54.7 (17.4) | 37.6 (9.9) | 2567 (< 0.001)*** | |

| EQ-5D-5 L index value | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 5614.5 (0.213) | |

| EQ-5D-5 L subjective score | 67.3 (19.1) | 65.8 (21.7) | 68.7 (16.1) | 5548 (0.168) | |

| FBIS objective burden | 7.8 (7.6) | 12.7 (7) | 3.2 (4.7) | 1422 (< 0.001)*** | |

| FBIS subjective burden | 0.7 (0.7) | 1.1 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.5) | 2358 (< 0.001)*** | |

*p value < 0.05.

**p value < 0.01.

***p value < 0.001.

χ2: chi-square test.

#Fischer’s exact test.

ICD-10: International classification of diseases; SD: standard deviation; SAPS: Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms; SANS: Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms; YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale; MADRS; Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning; SOFAS: Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale; EQ-5D-5 L: generic health-related quality of life (HRQoL) instrument for the measurement, description and valuation of health; FBIS: Family Burden Interview Schedule.

Sociodemographic characteristics: Mean age was comparable across sites. At AIIMS, there were significantly more male patients, more patients had lower education status, were unemployed, and had lower family income (p< 0.05). All patients at SCARF came from urban areas, whilst more than one third patients at AIIMS were from rural areas. The catchment area of AIIMS (range: 2–1367 km) was significantly greater than SCARF (range: 1–300 km). While the majority patients at SCARF came from nearby localities, patients at AIIMS came from six different states: Delhi (63), Uttar Pradesh (17), Bihar (14), Haryana (10), Uttarakhand (3), and Rajasthan (1).

Clinical characteristics: A significantly higher number of individuals at AIIMS were suffering from affective psychosis, which was also reflected in higher mean scores on the YMRS and MADRS. No significant differences were seen in SAPS and SANS scores or age of onset, duration of illness, and family history of any psychiatric illness between the two sites. Significantly higher functioning was noted on GAF and SOFAS scores at AIIMS. Quality of life as reflected on EQ-5D-5 L did not differ between sites. Family burden scores as reflected on FBIS (both subjective and objective) were higher at AIIMS (p< 0.001).

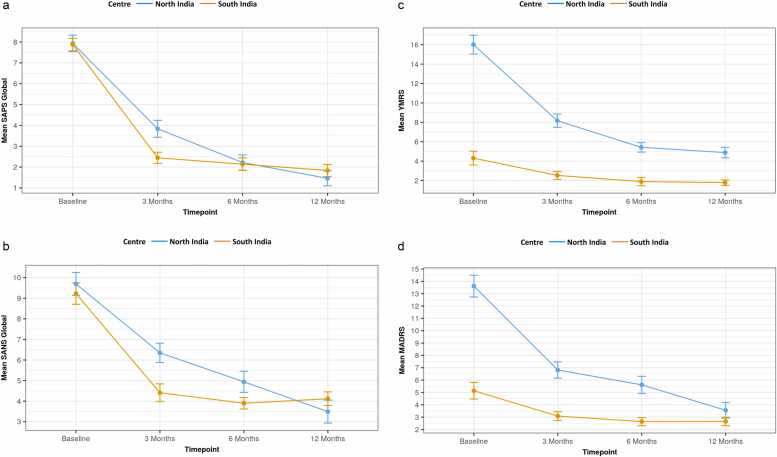

3.1.2. Follow-up analysis: similarities and differences in outcome variables across sites and time

Table 2 shows GEE model details for effect of group (site), time, and group*time interaction on dependent variables, viz., various scales assessing psychopathology, functioning, quality of life, etc. There was a significant time effect noted for all variables, which indicates that significant improvements were seen across all variables, indicating that all parameters (psychopathology, quality of life, functioning, and family burden) improved over time irrespective of site. Significant site-effect was noted for all variables except SAPS and SANS. This reflected fundamental differences between the sites across all variables (except SAPS and SANS) irrespective of the time of assessment. There were significant time*site interactions for all outcomes except scales for functioning (GAF and SOFAS). This indicates that the trajectories of improvement over time were comparable for functioning, but other trajectories showed statistically significant differences. Steeper improvement was seen in non-affective psychosis (SAPS and SANS) in the first three months at SCARF, and steeper improvement in affective symptoms (YMRS and MADRS) in the first three months at AIIMS. The reduction in family burden (FBIS) and improvement in quality of life (EQ-5D-5 L) were steeper at AIIMS during the first three months (see Figs. 1a–d and 2a–e). Pairwise analysis is shown in supplementary material.

Table 2.

Generalised estimation equation model details for effect of group and time on various dependent variables.

|

(Intercept) |

site |

time |

site*time |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wald Chi-Square | df | Sig. | Wald Chi-Square | df | Sig. | Wald Chi-Square | df | Sig. | Wald Chi-Square | df | Sig. | |

| SAPS GLOBAL | 601.150 | 1 | < 0.001*** | 0.955 | 1 | 0.328 | 407.961 | 3 | < 0.001*** | 13.302 | 3 | 0.004** |

| SANS GLOBAL | 625.254 | 1 | < 0.001*** | 2.462 | 1 | 0.117 | 214.307 | 3 | < 0.001*** | 12.045 | 3 | 0.007** |

| YMRS | 518.775 | 1 | < 0.001*** | 147.073 | 1 | < 0.001*** | 114.292 | 3 | < 0.001*** | 45.308 | 3 | < 0.001*** |

| MADRS | 326.614 | 1 | < 0.001*** | 48.428 | 1 | < 0.001*** | 116.896 | 3 | < 0.001*** | 41.476 | 3 | < 0.001*** |

| GAF | 9561.292 | 1 | < 0.001*** | 111.768 | 1 | < 0.001*** | 664.790 | 3 | < 0.001*** | 5.001 | 3 | 0.172 |

| SOFAS | 9624.006 | 1 | < 0.001*** | 105.094 | 1 | < 0.001*** | 595.150 | 3 | < 0.001*** | 4.143 | 3 | 0.246 |

| EQ 5D 5L INDEX VALUE | 64,601.465 | 1 | < 0.001*** | 39.101 | 1 | < 0.001*** | 125.415 | 3 | < 0.001*** | 14.992 | 3 | 0.002** |

| EQ 5D 5L SUBJECTIVE SCORE | 8055.700 | 1 | < 0.001*** | 9.147 | 1 | 0.002** | 125.228 | 3 | < 0.001*** | 31.114 | 3 | < 0.001*** |

| FBIS OBJECTIVE BURDEN | 260.419 | 1 | < 0.001*** | 27.422 | 1 | < 0.001*** | 212.109 | 3 | < 0.001*** | 194.439 | 3 | < 0.001*** |

| FBIS SUBJECTIVE BURDEN | 101.623 | 1 | < 0.001*** | 20.602 | 1 | < 0.001*** | 49.519 | 2 | < 0.001*** | 67.029 | 2 | < 0.001*** |

*p value < 0.05.

**p value < 0.01.

***p value < 0.001

EQ-5D-5L: generic health-related quality of life (HRQoL) instrument for the measurement, description and valuation of health; FBIS: Family Burden Interview Schedule; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning; MADRS: Montgomery Asberg Depression rating Scale; SANS: Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SAPS: Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms SOFAS: Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale; YMRS: Young’s Mania Rating Scale.

Fig. 1.

(a): Change in SAPS Global Over Time, (b): Change in SANS Global Over Time, (c): Change in YMRS Over Time, (d): Change in MADRS Over Time.

Fig. 2.

(a): Change in GAF Over Time, (b): Change in SOFAS Over Time, (c): Change in EQ-5D-5L index value Over Time, (d): Change in EQ-5D-5L subjective score Over Time, (e): Change in FBIS: Objective Burden Over Time. Description of figures: scores on all scales improved over time in both sites represented by the slopes of lines in both sites: downward slope in SAPS, SANS, YMRS, MADRS, and FBIS indicating reduction in psychopathology and family burden; and upward slope in EQ-5D-5L, GAF and SOFAS indicating improvement in quality of life and general as well as socio-occupational functioning. However, the steepness of slopes varies between different time points (except GAF and SOFAS). For example, in figure 4(a), where reduction in SAPS occurred drastically in the first three months at SCARF (South India) and nearly plateauing thereafter. However, at AIIMS (North India), the slope in the first three months is less steep than SCARF (South India), but the reduction continued for the subsequent three months as well.

4. Discussion

Two FEP cohorts being treated with a standard management protocol at sites in North (AIIMS) and South (SCARF) India were followed up prospectively at 3, 6 and 12 months, and assessed on psychopathology, functioning, quality of life, and family burden.

There was a significant effect of time on all outcomes across sites indicating improvements at both sites in clinical and functional outcomes during the one-year period. This suggests that a standard FEP management protocol delivered in two different regions of India can yield significant improvements despite differing cohort characteristics, which appear reflective of national statistics with higher employment levels, education, and family income in southern states as compared to northern states (Government of India, 2019; Statistics times 2022). Despite experiencing higher family burden at baseline, the North Indian cohort experienced a steeper reduction in family burden during the first three months of management, indicating that the management protocol (which included family psychoeducation) was successful in ameliorating high levels of family burden. Whilst there is a lack of Indian research examining family burden longitudinally in FEP, recent qualitative studies have shown that caregivers expect and value psychoeducation and psychosocial interventions (Kumar et al., 2019; Sadath et al., 2014).

While improvements were noted in all outcome variables over the course of one year, trajectories varied for most variables (except SOFAS and GAF) across sites. The rate of improvement on SAPS and SANS was greater in the first three months in South India as compared to North India, while the rate of improvement in YMRS and MADRS was steeper in the first three months in North India. This could be indicative of the population representation at the two sites with individuals with non-effective psychosis significantly higher in South India and individuals with affective psychosis higher in North India. Our Post-hoc analysis indicated that positive, negative, and affective symptoms improved most sharply during the initial 3–6 months of management. This finding echoes previous studies (Lally et al., 2017 Dec, Mangala et al.,), including from India (Mangala et al., 2012). Quality of life aligned with symptom remission also consistent with previous studies (Stouten et al., 2017).

Recent research on early intervention services for FEP patients has shifted its focus from symptom remission to functional recovery (Lally et al., 2017; Santesteban-Echarri et al., 2017). In our study, we observed that general and socio-occupational functioning improved in the first six months, which was likely attributable to the psychosocial elements of the treatment protocol. Previous prospective observational studies from India have reported positive outcomes at one-year follow-up for FEP patients (Saravanan et al., 2010, Iyer et al., 2010 Aug 1; Prakash et al., 2021). Of these, Iyer et al. (2010) compared FEP patients from South India and Canada and demonstrated greater improvement in negative symptoms and functioning in Indian patients, highlighting the role of clinical and socio-cultural factors in their recovery. Our study extends these findings by demonstrating that functional improvements in FEP can be achieved through management protocols (combining pharmacology and psychosocial intervention) in both North and South Indian cohorts.

This study has strengths. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first study to implement similar standard FEP assessment and management protocols across two settings in North and South India. Certain limitations should also be considered when interpreting our findings. First, due to a large amount of missing data in the North India cohort, we suspect a reduction in precision, and statistical power. However, attrition analysis demonstrated no significant differences in the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients retained compared to those who dropped out. Future work might examine reasons for (and strategies to reduce) high levels of treatment drop out, which likely include accessibility in rural and North Indian regions, and potentially attitudes and stigma towards psychiatrists (Mungee et al., 2016). Second, there were significant differences in participant characteristics (e.g., employment levels) between the two sites. Controlling for baseline differences between the two cohorts will have likely minimised but might not have completely eliminated the bias. Third, the relatively short follow-up duration of the study limits our ability to comment on longer-term outcomes. Finally, we did not assess pre-morbid functioning, adjustment, or cognitive functions, which could influence illness course and outcome, including functional recovery.

5. Conclusion

Our findings indicate that it is possible to implement standard FEP management protocols in low resource settings. The study having been done in a teaching hospital and psychiatric setting located 2000 km apart with many service and sociocultural differences demonstrated that the same standard FEP management protocol yielded positive clinical and functional outcomes in two regions in India, despite wide variations in culture and norms. Future research might consider strategies to ensure that FEP services are accessible in Northern and rural regions, e.g., telepsychiatry, collaborative work with traditional faith healers (Jain et al., 2012).

Author agreement

All authors have significantly contributed to the study. They have read and approved the revised manuscript for submission.

Ethical statement

The study was approved by the University of Warwick’s Biomedical and Scientific Research Ethics Committee and the local ethical committees. All study participants provided written informed consent. They could withdraw participation from the study at any time. Their treatment was not affected based on their participation in the study.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jai Shah: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Project administration. Rakesh K. Chadda: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Srividya Iyer: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Project administration. Max Birchwood: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Project administration. Nishtha Chawla: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Jason Madan: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Project administration. Mamta Sood: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. R.J. Lilford: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Project administration. Rangaswamy Thara: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Caroline Meyer: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Project administration. R. Padmavati: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Vijaya Raghavan: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Vivek Furtado: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Project administration. Swaran P. Singh: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Vaibhav Patil: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Graeme Currie: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Project administration. Tulika Shukla: Writing – original draft, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Mohapradeep Mohan: Visualization, Validation, Resources, Project administration. Mahadev Singh Sen: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2024.104103.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

References

- American Psychiatric Association A, 2000. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders IV-TR. American Psychiatric Association Washington, DC,.

- Andreasen, N.C., 1984. Scale for the assessment of positive symptoms (SAPS). University of Iowa Iowa City..

- Andreasen N.C. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS): conceptual and theoretical foundations. Br. J. Psychiatry Suppl. 1989;7:49–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitborde N.J.K., Srihari V.H., Woods S.W. Review of the operational definition for first-episode psychosiseip. Early Inter. Psychiatry. 2009;3(4):259–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2009.00148.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S., Pillai A., Jain S., Cohen A., Patel V. Outcomes of people with psychotic disorders in a community-based rehabilitation programme in rural India. The British Journal of Psychiatry. Cambridge University Press; 2009 Nov;195(5):433–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chokshi M., Patil B., Khanna R., Neogi S.B., Sharma J., Paul V.K., et al. Health systems in India. J. Perinatol. 2016;36(3):S9–S12. doi: 10.1038/jp.2016.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EuroQol Research Foundation. EQ-5D–5L User Guide [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Nov 25]. Available from: https://euroqol.org/publications/user-guides.

- Farooq S., Fonseka N., Ali M.W., Milner A., Hamid S., Sheikh S., et al. Early Intervention in Psychosis and Management of First Episode Psychosis in Low- and Lower-Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Schizophr. Bull. 2024;50(3):521–532. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbae025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francey, S.M., O’Donoghue, B., Nelson, B., Graham, J., Baldwin, L., Yuen, H.P., , 2020. Psychosocial Intervention With or Without Antipsychotic Medication for First-Episode Psychosis: A Randomized Noninferiority Clinical Trial. Schizophrenia Bulletin Open. Jan 1;1(1):sgaa015..

- Ghisletta, P., Spini, D., 2004. An Introduction to Generalized Estimating Equations and an Application to Assess Selectivity Effects in a Longitudinal Study on Very Old Individuals. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. American Educational Research Association; Dec 1, 29(4):421–437..

- Government of India, 2019. Handbook of Statistics on Indian States. Mumbai: Jayant Printery LLP..

- Hall R.C. Global assessment of functioning: a modified scale. Psychosomatics. 1995;36(3):267–275. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(95)71666-8. (Elsevier) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer S.N., Mangala R., Thara R., Malla A.K. Preliminary findings from a study of first-episode psychosis in Montreal, Canada and Chennai, India: Comparison of outcomes. Schizophr. Res. 2010;121(1):227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain N., Gautam S., Jain S., Gupta I.D., Batra L., Sharma R., et al. Pathway to psychiatric care in a tertiary mental health facility in Jaipur, India. Asian J. Psychiatry Elsevier. 2012;5(4):303–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jyani G., Sharma A., Prinja S., Kar S.S., Trivedi M., Patro B.K., et al. Development of an EQ-5D Value Set for India Using an Extended Design (DEVINE) Study: the Indian 5-Level Version EQ-5D Value Set. Value Health. 2022;25(7):1218–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2021.11.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan M.S., Shrivastava A., Gangadhar B.N. Early intervention in psychotic disorders: Challenges and relevance in the Indian context. Indian J. Psychiatry. 2010;52(Suppl1):S153–S158. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.69228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulhara P., Shah R., Grover S. Is the course and outcome of schizophrenia better in the ‘developing’ world? Asian J. Psychiatry. 2009;2(2):55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N., Rani, R., 2019. Regional Disparities in Social Development: Evidence from States and Union Territories of India. South Asian Survey. SAGE Publications India. Mar 1;26(1):1–27..

- Kumar, G., Sood, M., Verma, R., Mahapatra, A., Chadda, R.K., 2019. Family caregivers’ needs of young patients with first episode psychosis: A qualitative study: International Journal of Social Psychiatry [Internet]. SAGE PublicationsSage UK: London, England. [cited 2022 Jan 15]; Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0020764019852650?casa_token=aXI3QZvN-q8AAAAA%3A_gd2n3o1EbXkh0Ms3lsOhaRs4g649wGdrzGyA2idnCY9sTrcqU_Q6-5p7UqbomdISnc7mtGpA_NZqA.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lally J., Ajnakina O., Stubbs B., Cullinane M., Murphy K.C., Gaughran F., et al. Remission and recovery from first-episode psychosis in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of long-term outcome studies. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2017;211(6):350–358. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.117.201475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers L.M., McDonnell J., Stalmeier P.F.M., Krabbe P.F.M., Busschbach J.J.V. The Dutch tariff: results and arguments for an effective design for national EQ-5D valuation studies. Health Econ. 2006;15(10):1121–1132. doi: 10.1002/hec.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maji K.R., Sood M., Sagar R., Khandelwal S.K. A follow-up study of family burden in patients with bipolar affective disorder. Int J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2012;58(2):217–223. doi: 10.1177/0020764010390442. (SAGE Publications Ltd) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, S., 2007. Acute and Transient Psychosis: A Paradigmatic Approach. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 49. Wolters Kluwer--Medknow Publications, p. 233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Malla A., Norman R., McLean T., Scholten D., Townsend L. A Canadian programme for early intervention in non-affective psychotic disorders. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2003;37(4):407–413. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangala, R., Mohan, G., Joseph, J., John, S., Rangaswamy, T., 2012. . Early intervention for first-episode psychosis in India. East Asian Archives of Psychiatry [Internet]. Jan [cited 2022 Jan 16]; Available from: https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/INFORMIT.783897342571823.. [PubMed]

- McGorry P.D., Killackey E., Yung A.R. Early intervention in psychotic disorders: detection and treatment of the first episode and the critical early stages. Med. J. Aust. 2007;187(S7):S8–S10. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery S.A., Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mungee, Zieger A., Schomerus A., Ta TMT G., Dettling M., Angermeyer M.C., et al. Attitude towards psychiatrists: A comparison between two metropolitan cities in India. Asian J. Psychiatry Elsevier. 2016;22:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2016.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai S., Kapur R.L. The burden on the family of a psychiatric patient: development of an interview schedule. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1981;138:332–335. doi: 10.1192/bjp.138.4.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash J, Saini RK, Srivastava K, Chatterjee Kaushik, Basannar DR, Mohan Prafull, 2021. Longitudinal study of the course and outcome of first-episode psychosis. Medical Journal Armed Forces India [Internet]. [cited 16 Jan 2022]; Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377123721001155.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rathod, S., Pinninti, N., Irfan, M., Gorczynski, P., Rathod, P., Gega, L., , 2017. Mental health service provision in low-and middle-income countries. Health services insights. SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, England, 10:1178632917694350.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sadath A., Muralidhar D., Varambally S., Jose J.P., Gangadhar B.N. Caregiving and help seeking in first episode psychosis: a qualitative study. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. Ment. Health. 2014;1(2):47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar de Pablo G., Guinart D., Armendariz A., Aymerich C., Catalan A., Alameda L., et al. Duration of untreated psychosis and outcomes in first-episode psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis of early detection and intervention strategies. Schizophr. Bull. 2024 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbae017. Mar 16;sbae017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santesteban-Echarri O., Paino M., Rice S., González-Blanch C., McGorry P., Gleeson J., et al. Predictors of functional recovery in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017;58:59–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.09.007. Dec 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraswat N., Rao K., Subbakrishna D.K., Gangadhar B.N. The Social Occupational Functioning Scale (SOFS): a brief measure of functional status in persons with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2006;81(2):301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saravanan, B., Jacob, K.S., Johnson, S., Prince, M., Bhugra, D., David, A.S., 2010. Outcome of first-episode schizophrenia in India: longitudinal study of effect of insight and psychopathology. The British Journal of Psychiatry. Cambridge University Press, Jun;196(6):454–459.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Shiers, D., Lester, H., 2004. Early intervention for first episode psychosis. Bmj. British Medical Journal Publishing Group, 328(7454):1451–1452.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Singh S.P. In: Developments in Psychiatry in India: Clinical, Research and Policy Perspectives [Internet] Malhotra S., Chakrabarti S., editors. Springer India; New Delhi: 2015. Early intervention in the Indian context; pp. 89–98. cited 2022 Jan 15]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S.P., Brown L., Winsper C., Gajwani R., Islam Z., Jasani R., et al. Ethnicity and pathways to care during first episode psychosis: the role of cultural illness attributions. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15(1):287. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0665-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S.P., Mohan M., Iyer S.N., Meyer C., Currie G., Shah J., et al. Warwick-India-Canada (WIC) global mental health group: rationale, design and protocol. BMJ Open. Br. Med. J. Publ. Group. 2021;11(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics times. Indian States by GDP [Internet]. New Delhi: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation; 2022. Available from: https://statisticstimes.com/economy/india/indian-states-gdp.php.

- Stouten L.H., Veling W., Laan W., van der Helm M., van der Gaag M. Psychosocial functioning in first-episode psychosis and associations with neurocognition, social cognition, psychotic and affective symptoms. Early Inter. Psychiatry. 2017;11(1):23–36. doi: 10.1111/eip.12210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudharsanan N., Bloom D.E., Sudharsanan N. The Demography of Aging in Low-and Middle-income Countries: Chronological Versus Functional Perspectives. National Academies Press; 2018. US) Washington, DC; pp. 309–338. [Google Scholar]

- Varma V.K., Wig N.N., Phookun H.R., Misra A.K., Khare C.B., Tripathi B.M., et al. First-onset schizophrenia in the community: relationship of urbanization with onset, early manifestations and typology. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1997;96(6):431–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb09944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese, A., John, J.K., Rajkumar, S., Richard, J., Sethi, B.B., Trivedi, J.K., 1989. Factors Associated with the Course and Outcome of Schizophrenia in India Results of a Two-Year Multicentre Follow-Up Study. The British Journal of Psychiatry. Cambridge University Press.Apr;154(4):499–503.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Young R.C., Biggs J.T., Ziegler V.E., Meyer D.A. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material