Significance

Miscarriage in women is commonly associated with chromosomal errors, yet they are seldom associated with clinically detected pregnancy loss (PL) in other mammalian species. Here, we assessed equine products of conception following naturally occurring PL for the presence of a range of chromosomal errors across the entirety of gestation. Over the embryonic period, coinciding to a period rarely accessible in women, equine miscarriage was associated with a high prevalence of triploidy (three haploid sets of chromosomes). Similar to women, late first-trimester losses were dominated by whole chromosome and subchromosomal aberrations. The high synteny between human and horse chromosomes and the similar pace of embryonic development and gestation length support the horse as a unique model organism to study miscarriage.

Keywords: embryo, pregnancy, miscarriage, genetics, chromosome

Abstract

Chromosomal abnormalities are a common cause of human miscarriage but rarely reported in any other species. As a result, there are currently inadequate animal models available to study this condition. Horses present one potential model since mares receive intense gynecological care. This allowed us to investigate the prevalence of chromosomal copy number aberrations in 256 products of conception (POC) in a naturally occurring model of pregnancy loss (PL). Triploidy (three haploid sets of chromosomes) was the most common aberration, found in 42% of POCs following PL over the embryonic period. Over the same period, trisomies and monosomies were identified in 11.6% of POCs and subchromosomal aberrations in 4.2%. Whole and subchromosomal aberrations involved 17 autosomes, with chromosomes 3, 4, and 20 having the highest number of aberrations. Triploid fetuses had clear gross developmental anomalies of the brain. Collectively, data demonstrate that alterations in chromosome number contribute to PL similarly in women and mares, with triploidy the dominant ploidy type over the key period of organogenesis. These findings, along with highly conserved synteny between human and horse chromosomes, similar gestation lengths, and the shared single greatest risk for PL being advancing maternal age, provide strong evidence for the first animal model to truly recapitulate many key features of human miscarriage arising due to chromosomal aberrations, with shared benefits for humans and equids.

Miscarriage is a devastating condition, affecting over one in six recognized human pregnancies (1). Numerical and structural chromosomal aberrations are identified in up to 82% of pregnancy losses (PL) (2) defining them as the leading cause of PL in women from week 7 of gestation onwards. Aneuploidy is the most common type reported, defined as a deviation in the number of chromosomes in a cell due to loss or gain of chromosome(s) (3). In humans, it most commonly originates from aberrant maternal meiosis due to segregation errors such as those that involve the spindle architecture (4) but can also arise due to fertilization, paternal meiotic, and postzygotic mitotic errors (4, 5). Surprisingly, genome wide and autosomal chromosomal aberrations are seldom reported in products of conception (POC) following naturally occurring miscarriage in most other mammalian species (6, 7), leading to speculation that chromosomal instability leading to miscarriage is a phenomenon primarily confined to humans (8). Barriers in the research of chromosomal aberrations in human pregnancy arise from the difficulty in routinely detecting PL prior to week 6 to 7 of gestation, in obtaining POCs from these early losses, and the absence of gestationally age matched tissue from clinically normal pregnancies needed to determine the relevance of aberrations. Further, interventional studies and clinical trials have clear ethical restrictions leading to researchers and clinicians to explore alternative models. In the case of non-human primates, these alternatives are difficult to access and expensive, and standard models such as rodents have lower rates of chromosomal aberrations and very different pregnancy characteristics (9, 10).

Mares receive high levels of gynecological monitoring and care (11). Pregnancy diagnosis is performed 14 d after conception and POC can be obtained relatively easily from both healthy and failing pregnancies (12). Horses and humans share a similar gestation length (11 and 9 mo) and pace of early embryonic development compared with 14 other species (13). In a previous study, we found evidence of aneuploidy in equine POC lost prior to 65 d (7). Here, we performed Chromosomal Microarray Analysis (CMA), high-throughput sequencing, and short tandem repeat (STR) profiling to comprehensively investigate the prevalence of genome-wide, whole chromosome and subchromosomal copy number variations in equine POC following naturally occurring PL across the entirety of pregnancy in the mare.

Results and Discussion

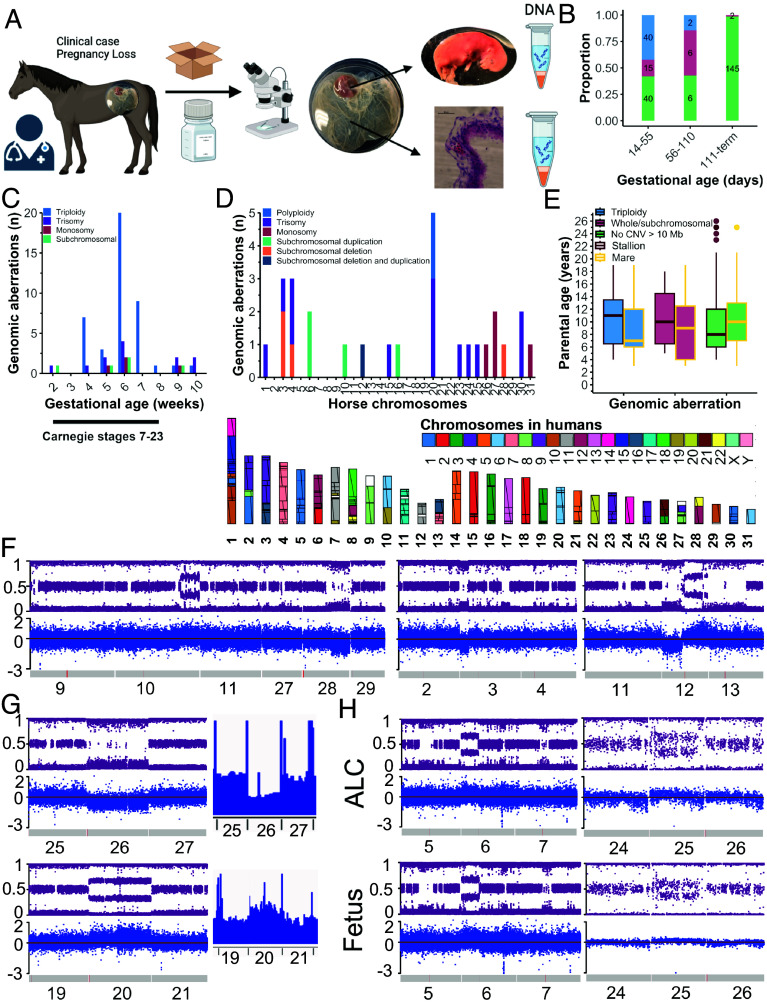

Two sources of equine POC were obtained: i) conceptuses submitted by clinicians to the laboratory following detection of a failed pregnancy and ii) placental and fetal tissue submitted to a diagnostic laboratory for postmortem investigation, following PL after day 110 of gestation (Fig. 1A). The 256 POC were obtained from 244 mares sired by 105 stallions managed on 44 premises by 26 veterinarians. CMA applied to DNA isolated from POC revealed chromosomal aberrations in 57.9% of PLs between pregnancy diagnosis and day 55 of gestation, 57.2% of PLs between 56 and110 d and 1.4% of PLs between 111 d and term (Fig. 1B). Triploidy was the most common aberration type, identified in 42.1% of POCs lost prior to 55 d (Fig. 1 B and C). Aneuploidy involving loss or gain of a single whole chromosome was associated with lethality across the first 10 wk of gestation while only subchromosomal deletions and duplications were identified after 110 d (Fig. 1C). This incidence of chromosomal aberrations is remarkably similar to that observed across eight large studies assessing human POC (2, 14). The cut-off of 55 d was selected to assess aberrations corresponding to embryo carnegie stage 7 to 23 [47 d in the mare (13) and accounted for the maximum uterine retention time (8 d) of embryos following pregnancy failure (15)]. This period is rarely investigated in women due to the scarcity of available material (2, 8, 14). To our knowledge, this is the first report of a substantial number of triploidy POC outside of humans. These findings quantify the predominance of triploidy over whole and subchromosomal errors present during the period of organogenesis, previously poorly characterized in any species including women due to scarcity of available material (8).

Fig. 1.

High prevalence of triploidy and aneuploidy in equine POC. (A) Methodology to obtain POC (created in Biorender). (B) Proportion of equine POC with chromosomal deletions and duplications >10 Mb following pregnancy loss prior to 55 d (n = 95), between 56 and 110 d (n = 14), and 111 d to term (n = 147). Actual numbers shown in columns. (C) Number of aberrations by type and week of early gestation. (D) Number of aberrations by equine autosome with synteny with human chromosomes indicated. (E) Median stallion (Left) and mare (Right) age by aberration type. (F) BAF and log R ratio (LogRR) plots for subchromosomal aberrations in day 42 POC (chromosomes 10 and 28, left), day 26 POC (chromosome 3, middle), and day 44 (chromosome 12, right). Red line indicates location of the centromere. (G) BAF, logRR, and coverage on WGS for day 46 POC with monosomy 26 (Top) and day 62 POC with trisomy 20 (Bottom). (H) Matched allantochorion (ALC) and fetal DNA plots from day 63 POC with duplication of the p arm of chromosome 6 and day 66 POC with trisomy 25 (Right).

Whole Chromosome and Subchromosomal Aberrations.

Whole chromosome or subchromosomal deletions or duplications were identified on 17/31 equine autosomes, consistent with studies of human POC (16/22 autosomes) (Fig. 1D) (2). Monosomies were confined to the shorter chromosomes; we therefore propose monosomy of the larger chromosomes results in PL prior to clinical detection. Equine chromosome 20 exhibited the most ploidy aberrations, followed by chromosomes 3 and 4. Equine chromosomes 3 and 4 have synteny with human chromosomes 16, 4, and 7 (Fig. 1D). Human chromosomes 16 and 7 were recently found to be the most commonly impacted by aberrations in human POC (2). This suggests that there may be features of the centromeres or associated error correction machinery of these chromosomes that leads to an increased risk of chromosomal instability (16). Like human trisomy 13, 18, and 21, not all equine trisomies are lethal in utero with live born individuals reported with trisomy 23, 26, 27, 28, 30, and 31 (17–22). Apart from two trisomy 30 POC, all chromosomal aberrations reported here (including the smaller subchromosomal aberrations), are thus far confined to an in utero lethal phenotype (17). Of the 256 POC assessed, 236 were from pregnancies established following natural mating illustrating relevance beyond assisted reproductive technologies. Surprisingly, there was no significant association between maternal age and ploidy aberrations (P = 0.22) (Fig. 1E). While unexpected, since mare oocytes are subject to age related aneuploidy (23), it may reflect age related endometrial degenerative conditions in the comparison group (euploid PLs), common in the mare (11). Paternal age was modeled as a categorical variable with 13 to 17 y old stallions having an increased risk for ploidy aberrations (odds ratio = 3.0, 95% CI 1.3 to 6.5, P = 0.01) compared with <13 and >18 y old groups. Detrimental effects of advancing paternal age on fetal outcome are described in human pregnancy (24). While the reduced odds in the oldest stallions is unexpected, it may be reflective of a selection bias in the male horse breeding population leading to a “healthy worker effect.”

Similar to observations of human POC, trisomies were the most common of the whole and subchromosomal aberrations [n = 12, includes 8 previously published (7)], followed by subchromosomal duplications and deletions greater than 10 Mb (n = 7) and monosomies [n = 4, includes 3 previously reported (7) (Fig. 1 F and G)]. The breakpoint of subchromosomal aberrations varied, both aligning with the position of the centromere (chromosomes 4, 6, 12) and not [chromosome 3, 10 and 28) (Fig. 1 F and H)]. This observation suggests that these aberrations may arise not only due to centromeric errors (16) but also genomic instability (25). A subset of trisomies and monosomies were also confirmed using low pass sequencing (n = 4, Fig. 1G). Mosaicism across the placental and fetal compartments was explored in a subset of POC. Chromosome number matched in both placental and fetal tissues in 7/7 whole chromosomal and subchromosomal aberrations assessed (Fig. 1H). This suggests the origins of these two aberration types are likely in maternal meiotic errors (26), further supported by the high rate of aneuploidy in equine oocytes retrieved from mares of advanced age (23). Mitotic errors as demonstrated in mouse early cleavage stage embryos are also plausible (27). Mosaicism has been demonstrated in a limited number of in vitro produced equine embryos (28), although how relevant these aberrations are to miscarriage after 2 wk is untested and brought into question here.

Whole-Genome Aberrations.

X and Y copy number in triploid POC were confirmed by a combination of CMA and PCR for Y markers as XXY and XXX (Fig. 2A), with no XYY identified (Fig. 2A). XYY is also rarely found in human POC as it is thought they are lost prior to clinical detection (29). Three triploids had complex abnormalities involving additional whole chromosome aberrations (Fig. 2A, top panel). Analysis of allele frequency and sequencing depth of six POC confirmed a bimodal pattern in two triploid POC with allele frequency at 0.33 and 0.66, and unimodal allele frequency at 0.5 in four POC without these aberrations (Fig. 2B). CMA and/or STR testing (Fig. 2C) of both allantochorion and fetal tissues identified triallelic loci in both the fetal and placental compartments in 15/16 POC tested, with one POC being triallelic by CMA in the allantochorion and biallelic on STR testing of the fetus. While CMA of the parents of POC is required to determine origins (30), the presence of aberrations in both fetal and placental compartments suggests that mitotic errors in POC associated with equine PL are introduced in the first divisions (27) or may be less common compared to humans (2). The majority of triploid POC included an embryo proper (Fig. 2D) (15). Gross assessment of 14 fetuses from triploid POC reported in a previous study blinded to genetic analysis (15) revealed 8/14 triploid fetuses had anomalies of the brain (Fig. 2D), and an additional 2/14 had other abnormalities involving the cardiovascular system similar to what is observed in human triploid fetuses (29, 31). One additional triploid fetus presented with amniotic band syndrome (Fig. 2F), the first case reported in the horse. This pregnancy showed normal conceptus anatomy and growth on ultrasonographic evaluation at 15 and 29 d of pregnancy. At day 43, it was small for gestational stage with a heartbeat that was then absent at 54 d. Human amniotic band syndrome has been reported to have an overlapping phenotype with other congenital anomalies, the most prevalent being neural tube defects (32). The underlying cause of equine triploidy needs further investigation, but may be due to polyspermy, meiotic errors, or mitotic errors during the first few zygotic divisions (33).

Fig. 2.

Triploid conceptuses are triallelic in both the fetal and placental compartments and most commonly include a fetus with developmental anomalies. (A) BAF and log R ratio (LogRR) plots for a XXY and XXX complex triploid POC (Left) and ratio of XXX, XXY, XYY triploid POC (Right). (B) Allele depth patterns using whole-genome sequencing show a unimodal pattern centered around 0.5 indicating a diploid heterozygote, and bimodal around 0.33 and 0.66 indicating a triploid heterozygote. (C) STR profiling of allantochorion (ALC) and fetus from a Day 45 triploid POC that is triallelic at STR loci ASB2, HMS1, and CA425. Day 37 POC that is biallelic at these loci and diploid on CMA. Triploids can present as anembryonic (image not shown), with fetal remnants (D) or embryonic (E). Anomalies of triploid conceptuses include pathology of the brain and cardiovascular systems reported elsewhere (15), as well as amniotic band syndrome (E).

Our findings provide the first substantive report of whole genome, whole chromosome, and subchromosomal aberrations in POC outside humans, showing chromosomal aberrations in the embryo are not unique to humans as often postulated (8). We show that PLs over carnegie stages 7 to 23 are dominated by triploidy, with a prevalence of 42.1%. As research of human POC has rarely reported on pregnancies lost prior to 6 to 7 wk of gestation, this observation is unique and not contradictory to the human literature. Indeed, our findings here of the equivalent gestation period (56 to 110 d) similarly showed a predominance of whole chromosome aberrations over triploidy (2) and a remarkably similar prevalence for triploidy (approximately 10% of spontaneous pregnancy losses) (31). Other ploidy aberrations showed a more heterogenous presentation, suggesting aneuploid cells of multiple types are not always reduced over the embryonic period. We speculate that maintenance of these cell populations will be dependent on the chromosome number, gene content, together with the pace at which the specific ploidy type leads to further secondary genomic instability as has been shown in tumor cells (34). The exact types of lethal ploidy aberrations prior to carnegie stages 7 (clinical detection) remain elusive, although may involve hemizygosity of the larger chromosomes which we failed to identify here. Future insights will come from increased mapping of ploidy aberrations in arresting morulas and blastocysts directly against those identified across the remainder of gestation.

The mare represents a unique model organism, experiencing natural miscarriage that increases with advancing maternal age (9). Here, we have shown that we can access POC over the first 6 wk of gestation, currently an underexamined period in human PL yet a crucial time for embryonic development (13). Due to the high synteny between many of the horse and human chromosomes, with 53% of equine autosomes showing conserved synteny with a single human chromosome (35), the horse model provides advantages over rodents when interrogating the mechanisms of centromere-driven chromosomal errors both in vitro and in vivo. Trophoblast cells can be isolated from equine POCs following miscarriage (12) providing key material for functional studies of trophoblast with altered chromosome number. Human and horse pregnancy also share many features such as similar pace of embryonic development (13), gestation length, and singleton offspring. Here, we show their embryos also share the greatest barrier to life, alterations in chromosomal content.

Materials and Methods

Below is a brief description of the materials and methods applied in this study. Further details are provided in SI Appendix, Extended Materials and Methods.

Research was performed under Cornell IACUC 1986-0216 and Clinical Research and Ethical Review Board at the Royal Veterinary College (URN:2012-1169 and URN:2017-1660-3). POCs of spontaneous equine PLs were obtained between 2013 and 2023 from breeding farms located in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Following a positive ultrasound pregnancy diagnosis 14 to 16 d post ovulation, first trimester (110 d of gestation, n = 109) PL was diagnosed by a subsequent negative ultrasound scan, e.g., absence of fetal heartbeats. Mid-to-late-term PLs (day 111-term, in the horse 340 d, n = 147) were diagnosed following spontaneous or assisted expulsion of the failed pregnancy/foal by the mare, or transrectal/transabdominal ultrasound observation of no fetal heartbeats.

First-trimester PLs were obtained and processed as previously described (7, 12). Fetal (muscle and/or ear) biopsies were collected from mid to late term PL POC submitted for postmortem examination to a diagnostic laboratory in Newmarket, United Kingdom, or directly to our research laboratory. Clinical data were recorded at time of collection or retrospectively from the veterinary practices’ clinical records, stud farms, Weatherbys Ltd annual Return of Mares or from publicly available data sources (https://www.racingpost.com).

Genomic DNA extracted from the tissue biopsies was submitted for genotyping using Illumina’s Axiom Equine 670 K SNP Genotyping array (n = 217 DNA isolates, Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) or the GGP Equine 70 K SNP array (n = 76 isolates, Neogen, Lansing, MI). EquCab 3.0 was used as the reference genome for both arrays (36). The data files were analyzed in Axiom Analysis Suite or Genome Studio 2.0 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), respectively, then the log R ratio (LogRR), B Allele frequency (BAF), and positions of the probes for each sample were exported into R version 4.3.3 (37) for analysis and graphical visualization. The BAF and LogRR plots of each sample were generated and visually assessed to determine the presence of whole genome (triploidy and complexed polyploidies such as triploidy with tetrasomy), chromosomal (monosomy or trisomy of one or more chromosomes), and/or subchromosomal (deletions or duplications measuring ≥10 Mb) aberrations. CNV segments of the same type (deletions or duplication) were merged within chromosomes using a distance between consecutive segments cut-off value of a range of 5 kb to 50 kb. Merging resulted in the call of one sample changing which was found to have subchromosomal loss of chromosome 28 and subchromosomal gain of chromosome 10. The statistical package karyoploteR (38) was used to create LRR and BAF plots using information about horse chromosome lengths from EquCab 3.0 assembly and centromere locations (39) to create chromosomal ideograms. The prevalence of each aberration was then calculated for each PL phenotype.

Sex determination was carried out using a combination of the CMA computed sex results and either a nested PCR reaction for detection of a Y chromosome anchored repeat or using a multiplex PCR for the Sex determining Region of Y (SRY) as reported previously (40). Nextera sequencing was performed to 10x coverage of the horse genome on four POC samples identified as aneuploidy, five with triploidy, and two euploid on CMA. Additionally, a subset of samples (n = 8, 4 triploid, 3 euploid and one segmental with aneuploidy on CMA) were sequenced using 150 bp pair-end across four flow cells using Illumina NovaSeq 6000 S4 platform at 30X coverage. Detailed methods on processing whole-genome sequencing data are available in SI Appendix, Extended Materials and Methods. STR analysis of 12 to 28 markers was performed on 192 tissue samples. The morphological characteristics of 14/42 triploid fetuses were available having been assessed and described previously (15). Data analysis codes are available in GitHub (https://github.com/deMestre-lab/Pregnancy-Loss-Genetics).

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

The Royal Veterinary College provided materials that contributed to this study. We would like to thank veterinarians from Rossdales Ltd, Newmarket Equine Hospital, Equine Reproductive Services as well as Dr. Jennie Henderson and Dr. Helen van Tuyll for submission of failed conceptuses. We thank Genomics Research Center at University of Rochester Wilmot Cancer Institute for library preparation and sequencing and Cornell University’s BioResource Center for STR fragment analysis. We graciously thank research technicians at the UC Davis Veterinary Genetics Laboratory for conducting STR genotyping. R.R.B. is affiliated with the University of California, Davis in the Veterinary Genetics Laboratory, a facility that offers animal genetic testing.

Author contributions

J.M.L., D.M., C.A.S., R.R.M., T.R., and A.M.d.M. designed research; J.M.L., S.E.S., D.M., A.K., W.J.v.d.B., C.A.S., T.S., D.J.H., A.K.F., J.S.B., R.J., and A.M.d.M. performed research; O.D.P., B.W.D., and R.R.B. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; J.M.L., S.E.S., D.M., W.J.v.d.B., J.W., and A.M.d.M. analyzed data; O.D.P. clinician who contributed the index case of triploidy and it’s clinical data; and J.M.L., S.E.S., D.M., and A.M.d.M. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

The R code and an R data object containing the data used to generate the results in the current study are available at https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.12745505 (41). Twelve array intensity files used to generate data for subtypes of chromosomal aberrations are available at https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.12746246 (42). Due to privacy and ethical consent restrictions in place under owner consent agreements, the remainder of the array intensity files are available for private access from the corresponding author.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Quenby S., et al. , Miscarriage matters: The epidemiological, physical, psychological, and economic costs of early pregnancy loss. Lancet 397, 1658–1667 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Essers R., et al. , Prevalence of chromosomal alterations in first-trimester spontaneous pregnancy loss. Nat. Med. 29, 3233–3242 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan L., et al. , Analysis of chromosomal copy number in first-trimester pregnancy loss using next-generation sequencing. Front. Genet. 11, 545856 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charalambous C., Webster A., Schuh M., Aneuploidy in mammalian oocytes and the impact of maternal ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 27–44 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hassold T., Hall H., Hunt P., The origin of human aneuploidy: Where we have been, where we are going. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, R203–R208 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmutz S. M., Moker J. S., Clark E. G., Orr J. P., Chromosomal aneuploidy associated with spontaneous abortions and neonatal losses in cattle. J. VET Diagn. Invest. 8, 91–95 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shilton C. A., et al. , Whole genome analysis reveals aneuploidies in early pregnancy loss in the horse. Sci. Rep. 10, 13314 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esteki M. Z., The effect of embryonic genome imbalances on pregnancy. Nat. Med. 29, 3014–3015 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipták N., Gál Z., Biró B., Hiripi L., Hoffmann O. I., Rescuing lethal phenotypes induced by disruption of genes in mice: A review of novel strategies. Physiol. Res. 70, 3–12 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tosh J., Tybulewicz V., Fisher E. M. C., Mouse models of aneuploidy to understand chromosome disorders. Mamm Genome 33, 157–168 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shilton C. A., Kahler A., Roach J. M., Raudsepp T., de Mestre A. M., Lethal variants of equine pregnancy: Is it the placenta or foetus leading the conceptus in the wrong direction? Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 35, 51–69 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rose B. V., et al. , A method for isolating and culturing placental cells from failed early equine pregnancies. Placenta 38, 107–111 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halley A. C., The tempo of mammalian embryogenesis: Variation in the pace of brain and body development. Brain Behav. Evol. 97, 96–107 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozawa N., et al. , Maternal age, history of miscarriage, and embryonic/fetal size are associated with cytogenetic results of spontaneous early miscarriages. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 36, 749–757 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahler A., et al. , Fetal morphological features and abnormalities associated with equine early pregnancy loss. Equine Vet. J. 53, 530–541 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vázquez-Diez C., Paim L. M. G., FitzHarris G., Cell-size-independent spindle checkpoint failure underlies chromosome segregation error in mouse embryos. Curr. Biol. 29, 865–873.e3 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bugno-Poniewierska M., Raudsepp T., Horse clinical cytogenetics: Recurrent themes and novel findings. Animals 11, 831 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kubien E. M., Tischner M., Reproductive success of a mare with a mosaic karyotype: 64, XX/65, XX, +30. Equine Vet. J. 34, 99–100 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holl H. M., Lear T. L., Nolen-Walston R. D., Slack J., Brooks S. A., Detection of two equine trisomies using SNP-CGH. Mamm Genome 24, 252–256 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klunder L. R., McFeely R. A., Beech J., McClune W., Bilinski W. F., Autosomal trisomy in a standardbred colt. Equine Vet. J. 21, 69–70 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lear T. L., Cox J. H., Kennedy G. A., Autosomal trisomy in a Thoroughbred colt: 65, XY, +31. Equine Vet. J. 31, 85–88 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buoen L. C., et al. , Arthrogryposis in the foal and its possible relation to autosomal trisomy. Equine Vet. J. 29, 60–62 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rizzo M., et al. , The horse as a natural model to study reproductive aging-induced aneuploidy and weakened centromeric cohesion in oocytes. Aging 12, 22220–22232 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nybo Andersen A.-M., Hansen K. D., Andersen P. K., Davey Smith G., Advanced paternal age and risk of fetal death: A cohort study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 160, 1214–1222 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munisha M., Schimenti J. C., Genome maintenance during embryogenesis. DNA Repair 106, 103195 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gruhn J. R., et al. , Chromosome errors in human eggs shape natural fertility over reproductive life span. Science 365, 1466–1469 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allais A., FitzHarris G., Absence of a robust mitotic timer mechanism in early preimplantation mouse embryos leads to chromosome instability. Development 149, dev200391 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Coster T., et al. , Genome-wide equine preimplantation genetic testing enabled by simultaneous haplotyping and copy number detection. Sci. Rep. 14, 2003 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McFadden D. E., Phenotype of triploid embryos. J. Med. Genet. 43, 609–612 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gabriel A. S., et al. , An algorithm for determining the origin of trisomy and the positions of chiasmata from SNP genotype data. Chromosome Res. 19, 155–163 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Massalska D., et al. , Triploid pregnancy–Clinical implications. Clin. Genetics 100, 368–375 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bergman J. E. H., et al. , Amniotic band syndrome and limb body wall complex in Europe 1980–2019. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 191, 995–1006 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baumer A., Balmer D., Binkert F., Schinzel A., Parental origin and mechanisms of formation of triploidy: A study of 25 cases. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 8, 911–917 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Passerini V., et al. , The presence of extra chromosomes leads to genomic instability. Nat. Commun. 7, 10754 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wade C. M., et al. , Genome sequence, comparative analysis, and population genetics of the domestic horse. Science 326, 865–867 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalbfleisch T. S., et al. , Improved reference genome for the domestic horse increases assembly contiguity and composition. Commun. Biol. 1, 197 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.R Core Team, R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2024). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gel B., Serra E., karyoploteR: An R/Bioconductor package to plot customizable genomes displaying arbitrary data. Bioinformatics 33, 3088–3090 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giulotto E., Raimondi E., Sullivan K. F., The unique DNA sequences underlying equine centromeres. Prog. Mol. Subcell Biol. 56, 337–354 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raudsepp T., et al. , Molecular heterogeneity of XY sex reversal in horses. Anim. Genet. 41, 41–52 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lawson J. M., et al. , deMestre-lab/Pregnancy-Loss-Genetics-PNAS. Zenodo. https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.12745505. Deposited 15 July 2024.

- 42.Lawson J. M., et al. , GGP equine intensity files. Zenodo. https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.12746246. Deposited 15 July 2024.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

The R code and an R data object containing the data used to generate the results in the current study are available at https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.12745505 (41). Twelve array intensity files used to generate data for subtypes of chromosomal aberrations are available at https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.12746246 (42). Due to privacy and ethical consent restrictions in place under owner consent agreements, the remainder of the array intensity files are available for private access from the corresponding author.