Abstract

Purpose

Due to the Coronavirus Disease-19 pandemic, the fellowship application process has transitioned from in-person interviews to virtual interviews. Although several studies have assessed the impact of Coronavirus Disease-19 on residency and fellowship interviews, fewer studies have investigated the program director’s perspective. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the experience of virtual interviews on hand fellowship program directors and understand some of the important factors that may make an applicant more competitive.

Methods

A 21-question survey was conducted through Google Forms and distributed through a standardized email to hand fellowship program directors and coordinators. Questions used a 5-point Likert scale with the opportunity for respondents to answer some questions in a free-response format. Statistical analysis was conducted with significance assigned to P values < .05.

Results

Ninety-three surveys were distributed, of which 35 responses were obtained, corresponding to a 37.6% survey response rate. Program directors reported that they tended to place more emphasis on applicant’s curriculum vitae, calls from colleagues, and applicants that they had previously met. In addition, program directors felt that applicants were able to accurately represent themselves through the virtual format. Finally, most program directors stated that they were highly likely to continue to offer virtual interviews.

Conclusions

With several parenting organizations and program directors affirming that they are comfortable with proceeding with virtual interviews, it is essential for hand fellowship applicants to understand what factors program directors may perceive as more important. It is possible that the virtual interview process may effectively achieve suitable matches between applicants and institutions.

Type of study/level of evidence

Decision analysis IIIb.

Key words: Hand fellowship, Hand surgery, Interviews, Surgical education, Virtual

The interview is a critical aspect of the fellowship selection process.1, 2, 3 Historically, applicants apply for hand fellowship using the online American Society for Surgery of the Hand Fellowship System and, if selected, are invited for a formal in-person interview.4,5 However, the Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) pandemic vastly changed the residency and fellowship application process.6,7 In May 2020, the Association of American Medical Colleges encouraged the transition from in-person to virtual interviews, which applied to medical school, residency, and fellowship.4,5,8 Furthermore, this statement was supported by the American Orthopaedic Association, the Council of Orthopaedic Residency Directors, and the American Council of Academic Plastic Surgeons.9

Virtual interviews in graduate medical education are typically composed of a two-way interview on video-conferencing platforms, such as Skype, WebEx, Microsoft Teams, and Zoom.10 Similar to a traditional interview, virtual interviews can involve group interviews, real-time content sharing, and multiple rooms for interviewees to participate in.10 Through the utilization of virtual interviews, applicants have stressed that this shift has allowed for an increase in scheduling flexibility, decreased financial expenses associated with the traditional interview process, and minimized lost clinical time.2, 3, 4,9,11, 12, 13 Still, there are several limitations that may hinder both applicants and institutions due to the virtual interview process. For instance, it has become more difficult for programs to give facility tours, introduce current residents and faculty, and showcase their culture and attributes to applicants through virtual software.14,15 Therefore, the virtual format requires a strong online presence and digital footprint to generate a comprehensive perspective of the program. Applicants may also encounter difficulties with demonstrating their personality and fit solely in the virtual setting.

Applicants for hand fellowship programs include general, plastic, and orthopedic surgery residents. The American Society for Surgery of the Hand surveyed hand fellowship applicants and program directors about the 2020–2021 cycle.16 The results of the survey found that 81% of applicants were satisfied with the virtual process, and only 20% desired in-person interviews in the future. Forty-three percent of programs stated that the quality of virtual interviews was lower than that of in-person interviews, but 53% stated that virtual interviews were as good as or better than in-person interviews. Finally, another study concerning the 2020–2021 cycle found that nearly 80% of surveyed hand surgery fellowship applicants preferred virtual interviews.12 Although several studies about the impact of COVID-19 on residency and fellowship interviews have been published from the applicants’ perspective, fewer studies have investigated the educators’ perspective.17

The aim of this study was to assess the experience of virtual interviews on hand fellowship program directors. This study is unique in that it investigates the hand fellowship interview process from the educator’s perspective—something that is invaluable to the applicant and has not been notably explored in the literature. The anonymity of this study allowed for honest feedback and responses from the surveyed program directors.

Methods

Participant population

A study regarding the perception of the virtual interview process among hand surgery fellowship program directors was conducted. Individuals from orthopedic surgery, plastic surgery, or combined fellowship programs were eligible to participate.

Survey creation and distribution

A 21-question survey was created and distributed to all American Society for Surgery of the Hand program directors and coordinators through Google Forms to better understand the program director’s perception of the virtual interview process (Table). The survey was created by our research team to ensure that our questions encapsulated the most crucial factors that contributed to a program director’s perception of an applicant through the virtual interview experience. Questions were formatted to be clear and concise to minimize response bias and survey fatigue. Within the 21 questions, there were opportunities for respondents to answer follow-ups to some questions in a free-response format. Survey links were distributed to program directors and coordinators in a standardized email on December 16, 2022 that notified the respondents of the nature of the survey and that all responses were voluntary and anonymous. Reminders for the survey were sent on January 5, 2023 and January 24, 2023 in order to ensure adequate response. The survey was closed on January 31, 2023. All survey results were collected in a deidentified manner, with an option for respondents to receive a copy of their responses through email.

Table.

Relevant Questions Included in Survey of Hand Fellowship Program Directors

| Question | Possible Responses |

|---|---|

|

orthopedic surgery, plastic surgery, combined |

|

31–40, 41–50, 51–60, 61–70, 70+ |

|

0–5, 6+ |

|

1–5, with 1 being not satisfied and 5 being extremely satisfied |

|

1–5, with 1 being not convenient and 5 being extremely convenient |

|

Yes/No with opportunity for free response |

|

1–5, with 1 being not difficult and 5 being extremely difficult |

|

1–5, with 1 being not confident and 5 being extremely confident |

|

1–5, with 1 being minimal emphasis placed and 5 being extreme emphasis placed |

|

1–5, with 1 being minimal emphasis placed and 5 being extreme emphasis placed |

|

1–5, with 1 being minimal emphasis placed and 5 being extreme emphasis placed |

|

1–5, with 1 being minimal contribution and 5 being extreme contribution |

|

1–5, with 1 being that candidates were not able to accurately present themselves and 5 being that candidates were accurately able to represent themselves |

|

1–5, with 1 being not able to establish rapport and 5 being able to establish rapport |

|

1–5, with 1 not being able to portray the program and 5 being able to portray the program |

|

1–5 with 1 being not able to and 5 being able to with opportunity for free response |

|

1–5, with 1 being not considering and 5 being highly likely to consider |

|

Northeast, Midwest, South, West, Other |

|

Free response |

|

Free response |

|

Yes/No |

Outcomes and statistical analysis

The primary outcome of this study was to assess what factors program directors deemed important for applicants to successfully match at their institution. Additionally, we used questions that would help us understand the strengths and weaknesses of the virtual interview process, along with how preferences toward certain factors in an applicant’s application may have shifted because of virtual interviews. Through free-response questions, we wanted to assess if program directors had made any changes during the interview process to better portray their institutions in comparison to previous years. Furthermore, we wanted to determine if hand fellowship directors were likely to continue offering virtual interviews. Finally, we wanted to evaluate the frequency and types of technical difficulties that program directors ran into. Most questions used a 5-point Likert scale with some being free responses and others that were answered on a yes/no basis. All data were imported into Microsoft Excel, which was used to create tables and figures and perform statistical analysis. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to obtain statistical significance for two independent samples of ordinal variables. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to obtain statistical significance for greater than two independent samples. P values < .05 were considered to be statistically significant results.

Results

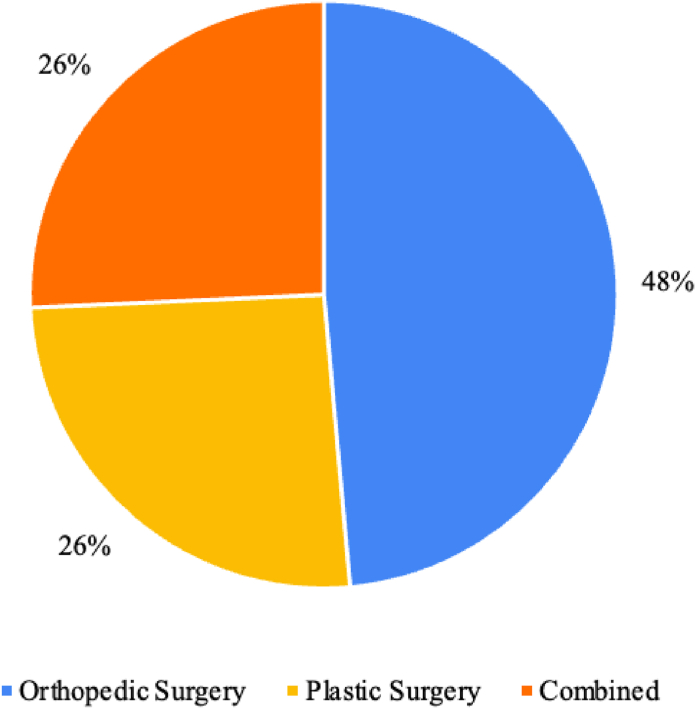

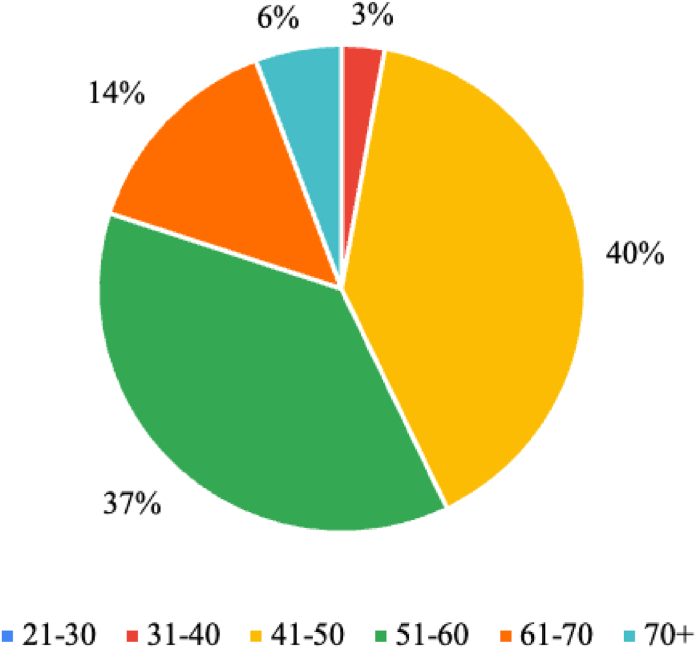

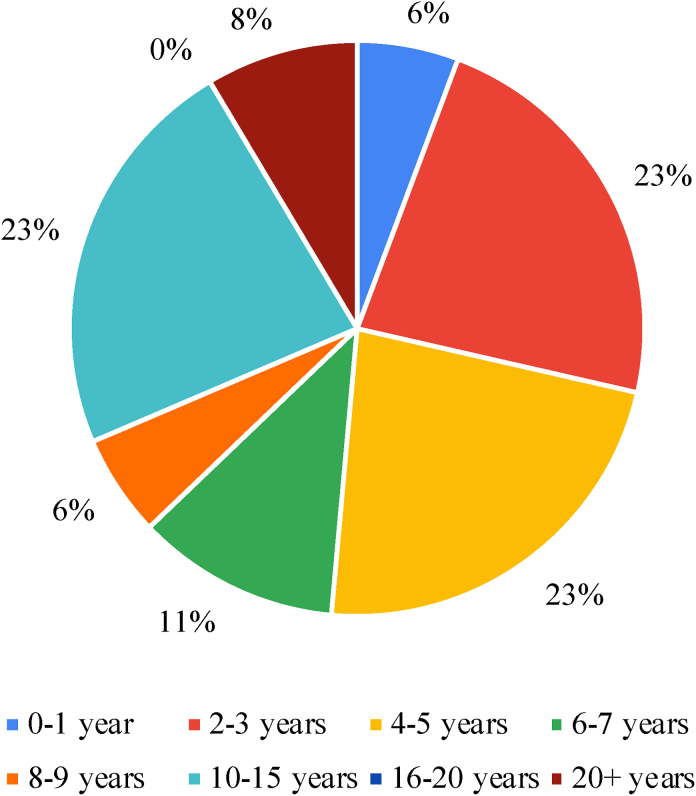

A total of 93 surveys were distributed through a standardized email to program directors and respective program coordinators, of which 35 responses were obtained, corresponding to a 37.6% survey response rate (Table). Most questions were answered in full, with four Likert scale questions and one free-response question not being answered by all participants. The majority of responses came from an orthopedic-based training program with 17 program directors (48.6%) representing an orthopedic surgery fellowship, nine program directors (25.7%) reported being a plastic surgery hand fellowship, and nine program directors (25.7%) reported being a combined orthopedic and plastic surgery hand fellowship (Fig. 1). Our study population reported being predominantly 41–50 years in age (40%), which was followed by 51–60 years (37.1%), 61–70 years (14.3%), 71+ years (5.7%), and 31–40 years (2.9%) (Fig. 2). Fellowship directors reported that they had been fellowship directors for 2–5 years (45.8%), 10–15 years (22.9%), 6–9 years (17.1%), and 20+ years (8.6%) (Fig. 3).

Figure 1.

Hand fellowship institution type.

Figure 2.

Age breakdown of program directors.

Figure 3.

Length of tenure breakdown for program directors.

Additionally, 62.9% of program directors (n = 22) reported moderate to high levels of satisfaction with the virtual match fellowship process, with aggregate data demonstrating an overall neutral response with a score of 3.69 ± 1.18, and 54.3% of program directors (n = 19) reported moderate to high levels of convenience with the virtual interview (3.43 ± 1.09). In addition, 82.9% of program directors (n = 29) stated that they did not encounter any technical difficulties that interfered with the interview process. Of the program directors who responded to having experienced technical difficulties, the most common difficulty was Zoom or Webex connectivity issues (n = 5), time zone differences (n = 3), audio and visual issues (n = 2), and issues with internet connectivity (n = 2). Although 25.7% of program directors (n = 9) reported a moderate to high level of difficulty in determining the best fit of applicants for their program, 22.9% (n = 8) of fellowship directors reported moderate to low levels of difficulty, with the overall data demonstrating a moderately low/neutral response (2.74 ± 1.12). Program directors demonstrated mixed responses for their confidence in their ability to match their top choice to the same extent as they would have with in-person interviews, with 48.6% (n = 17) of program directors stating that they were moderate to highly confident and 28.6% (n = 10) showing moderate to low confidence, with the aggregate data demonstrating moderately high confidence (3.37 ± 1.17).

Additionally, 45.7% of program directors (n = 16) reported no change in the level of emphasis placed on applicant’s curriculum vitae (CV)s compared with in-person interviews, with an overall neutral response to the question (3.17 ± 0.89). Similarly, 54.3% of program directors (n = 19) reported no change in the emphasis placed on an applicant’s institution compared with in-person interviews, with the overall response receiving a neutral score of 2.91 ± 0.95. The majority of program directors (51.4%) reported no change in the emphasis they placed on calls from colleagues compared with in-person interviews, with 28.6% (n = 10) reporting a moderately higher emphasis that was placed, with an overall neutral response by program directors (3.23 ± 0.84), and 22.9% of program directors (n = 8) stated that they would tend to rank applicants that they were familiar with higher with an overall response of 2.91 ± 1.09.

Most program directors (62.8%) felt that virtual interviews allowed candidates to represent themselves accurately and sufficiently. In addition, 48.6% of program directors felt that they were effectively able to establish rapport with the interviewee to the same extent they would have been able to during an in-person interview and that they were able to portray their program accurately and sufficiently to applicants. Program directors stated that familiarity with the online interview process, meet and greets, and updated institutional websites were factors that allowed programs to better represent themselves to applicants in comparison to previous years. If given the option, a majority of program directors (57.2%) stated that they would consider continuing to offer virtual interviews. On average, programs offer 37.56 ± 13.26 interview spots each year, with the range of fellows accepted per year varying widely from 1 to 8 and a median of 2.17 ± 1.62 fellows per year. Most program directors (75.8%) stated that the number of interviews offered has not changed since the implementation of virtual interviews. Finally, 33.3% of program directors (n = 11) were located in the Midwest, 33.3% (n = 11) in the Northeast, 21.2% (n = 7) in the West, and 12.1% (n = 4) in the South.

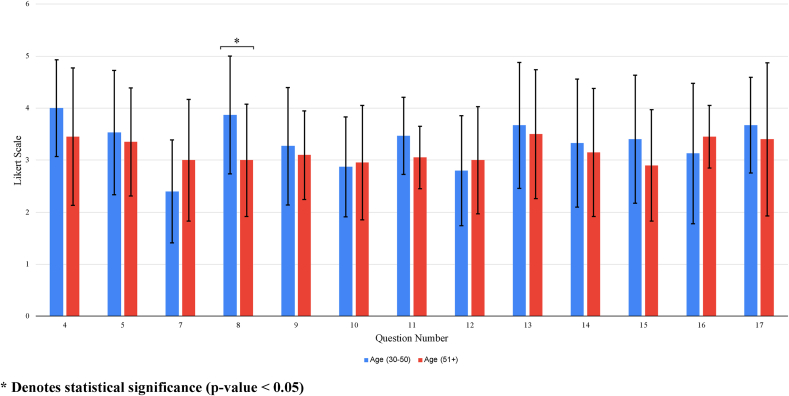

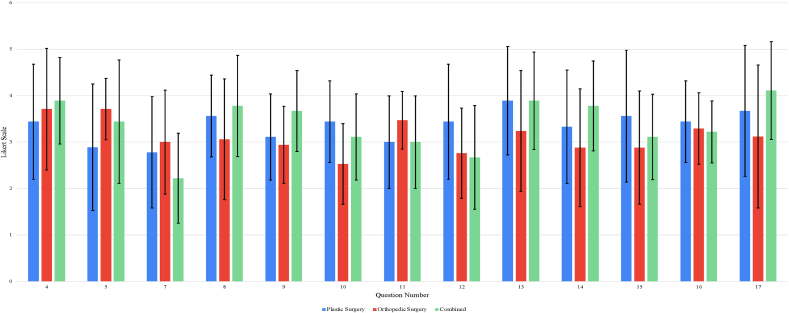

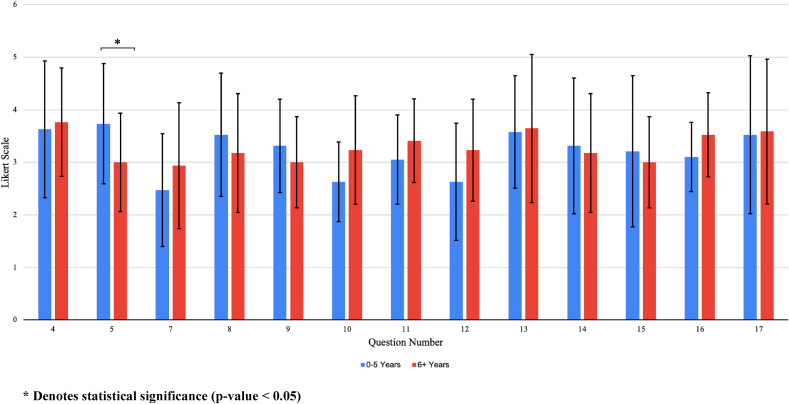

When the surveys were stratified by program director age (30–50 and 51+), we determined that there was a significant difference in respondents’ confidence in their ability to match their top choice to the same extent had interviews been in person (P = .036) (Fig. 4). Program directors between the ages of 30–50 (n = 15) scored a 3.86 ± 1.13, demonstrating being moderately comfortable, whereas program directors that were over the age of 51 (n = 20) scored a 3 ± 1.08, demonstrating an overall neutral response. There were no other significant differences found between questions when surveys were stratified by age. When surveys were stratified by type of program (plastic surgery, orthopedic surgery, or combined), we found that there were no significant differences between questions (Fig. 5). Finally, when surveys were stratified by length of program director tenure (0–5 years and 6+ years), we determined that there was a significant difference in the convenience of virtual interviews when compared with that of in-person interviews (P = .038) (Fig. 6). Program directors for fewer than 5 years (n = 18) scored a 3.74 ± 1.15, demonstrating moderately high convenience to the virtual interview process, whereas program directors for over 5 years (n = 17) scored a 3 ± 0.94, demonstrating an overall neutral response to the question. There were no other significant differences found between questions when surveys were stratified by program director tenure.

Figure 4.

Survey responses stratified by age.

Figure 5.

Survey responses stratified by program type.

Figure 6.

Survey responses stratified by duration of program director tenure.

Discussion

Although most interviews were conducted in person prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, several organizations such as the Association of American Medical Colleges and American Council of Academic Plastic Surgeons have requested that programs continue to offer virtual interviews in the current application cycle.18,19 With the potential for future interview cycles to be in the virtual setting, it is essential for applicants to understand what factors program directors may consider to a higher degree. Furthermore, we believe that our study is the first to characterize the impact of the virtual interview process on hand fellowship directors.

Our study determined that program directors were overall satisfied with the virtual interview process and found virtual interviews were more convenient than in-person interviews. Program directors with a shorter tenure felt a greater convenience associated with virtual interviews than more experienced program directors. The reason for this finding may be multifactorial—program director’s age, openness to try new interview environments, and a lack of tradition may be factors for our finding. Also, most program directors faced no technical difficulties during the interview process. It should be noted that for the National Resident Match Program results in 2022, in which all the interviews were conducted virtually by the enrolled 94 programs, 95.5% of applicants matched.20

After the introduction of virtual interviews, applicants had lower financial costs and less time off from academic activity associated with the virtual interview process.21 Furthermore, a study by Wang et al22 determined that although the virtual interview process is associated with significantly lower costs, applicants have found that the virtual interview format does not accurately represent institutions. Program directors were overall neutral in regard to whether they were better able to portray their institution in comparison to previous years. Program directors stated that informational sessions, videos, updated websites, meet and greets, and more experience in the virtual setting were factors that allowed them to better portray their organization. The disconnect between program directors and applicants in regard to institution perception may be improved through the addition of more virtual events, such as meet and greets and resident/fellow socials.23

Overall, most program directors stated that they faced little to no difficulty in determining which applicants would be the “best fit” for their program, with only 25.7% of program directors stating that they had a more difficult time assessing which candidates would fit well at their institution. In addition, program directors were overall neutral in their confidence to match their top choice to the same extent had the interviews been in person. Interestingly, our study determined that when program directors were stratified by ages 30–50 and 51+, there was a statistically significant difference among younger and older program directors in their confidence to match their top choice to the same extent had interviews been in-person. Younger program directors were overall more confident in their ability to match their top choice than older program directors, which may be secondary to younger program directors undergoing training more recently and, as a result, better connecting with applicants during virtual interviews.

Program directors stated that they did not place more weight on an applicant’s institution during virtual interviews. Program directors did report that they placed more emphasis on applicant CV and calls from colleagues on behalf of applicants in comparison to when interviews were in-person. In addition, program directors were more likely to rank applicants they had previously met or were more familiar with. Taken altogether, our study demonstrates the importance of applicants conducting meaningful research, networking at events such as conferences, and forming professional relationships with faculty who would be willing to call program directors on an applicant’s behalf.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Silvestre et al24 found that between 2012 and 2020, the number of available positions grew from 150 to 177. Their analysis found that match rates for a hand fellowship increased because of additional positions that were available and a decline in the number of applicants. More specifically, the total number of hand fellowship applicants decreased by 5.5%, and the total number of available positions increased by 18.0%.24 During the same study period, there was a 20.2% and 11.1% increase in available positions within orthopedic and plastic hand surgery fellowships, respectively. The percentage of applicants who did not match decreased from 24.6% in 2012 to 5.9% in 2020.24 Our data set demonstrates that most institutions accept between one and eight fellows, with the median number of fellows accepted being 2.17. Additionally, program directors reported that the typical number of interviews varied between 20 and 80. Interestingly, 71% of program directors stated that since the implementation of virtual interviews, the number of interviews offered has not changed. As a result, it is quite possible to assume that due to the COVID-19 pandemic and a higher demand for fellowship-trained hand surgeons, there has been an increase in the number of individuals who are looking to pursue hand fellowships. The limited in-person interactions between program directors and applicants may mean that applicants will have to put additional time and effort into networking, research, and fostering relationships with faculty and other practicing hand surgeons.

Our study has several noteworthy limitations. Primarily, our survey response rate was 37.6%, and as such, we believe that our data set may be limited in its ability to make more general conclusions about program directors. There is the possibility that responders of our survey may not be representative of survey nonresponders, which could potentially lead to a fallacy of composition. In addition, at the time of the study, there were no standardized or validated surveys that had been used to assess program directors’ perceptions of the virtual interview process. As a result, there is the possibility that our survey does not encompass all the factors that program directors may deem crucial during the virtual interview process. Additionally, it is important to consider that program directors work alongside professors, fellows, and other faculty during the interview and review process; hence, their opinions might also influence the final acceptance. Finally, in an effort to keep our survey anonymous, personal questions were limited. Thus, our survey may not include additional details on what may impact applicants during the virtual hand fellowship match process.

Conflicts of Interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received related directly to this article.

References

- 1.Chang T.C., Hodapp E.A., Parrish R.K., et al. Virtual versus in-person surgical fellowship interviews and ranking variability: the COVID-19 experience. Preprint. Res Sq. 2021;rs.3 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pathak N., Schneble C.A., Petit L.M., Kahan J.B., Arsoy D., Rubin L.E. Adult reconstruction fellowship interviewee perceptions of virtual vs in-person interview formats. Arthroplast Today. 2021;10:154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2021.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bamba R., Bhagat N., Tran P.C., Westrick E., Hassanein A.H., Wooden W.A. Virtual interviews for the independent plastic surgery match: a modern convenience or a modern misrepresentation? J Surg Educ. 2021;78(2):612–621. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peyser A., Gulersen M., Nimaroff M., Mullin C., Goldman R.H. Virtual obstetrics and gynecology fellowship interviews during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: a survey study. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):449. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02893-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swendiman R.A., Jones R.E., Blinman T.A., Krummel T. Disrupting the fellowship match: COVID-19 and the applicant arms race. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(4):1069–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kebede S., Marxen T., Om A., Bakayoko N., Losken A. COVID-19 and the integrated plastic surgery match: an update on match trends by applicant location. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10(9) doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000004527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antezana L.A., Rode M., Muro-Cardenas J., Xie K., Weissler J., Bakri K. Home sweet home: the integrated plastic surgery residency match during the COVID-19 pandemic. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;150(2):492e–494e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000009288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tawfik A.M., Imbergamo C., Chen V., et al. Perspectives on the orthopaedic surgery residency application process during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2021;5(10) doi: 10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-21-00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yong T.M., Davis M.E., Coe M.P., Perdue A.M., Obremskey W.T., Gitajn I.L. Recommendations on the use of virtual interviews in the orthopaedic trauma fellowship match: a survey of applicant and fellowship director perspectives. OTA Int. 2021;4(2) doi: 10.1097/OI9.0000000000000130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagedorn J.C., 2nd, Chen J., Weiss W.M., Fredrickson S.W., Faillace J.J. Interviewing in the wake of COVID-19: how orthopaedic residencies, fellowships, and applicants should prepare for virtual interviews. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29(7):271–277. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-01148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peebles L.A., Kraeutler M.J., Waterman B.R., Sherman S.L., Mulcahey M.K. The impact of COVID-19 on the orthopaedic sports medicine fellowship application process. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2021;3(4):e1237–e1241. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2021.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Major M., Yoon J., Liang F., Shores J. Perception of the virtual interview format in hand surgery fellowship applicants. J Hand Surg Am. 2023;48(2):109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2022.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon J., Pan J., Major M., et al. Craniofacial fellowship applicant perceptions of virtual interviews. J Craniofac Surg. 2022;33(8):2379–2382. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000008759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh A., Haddad A.G., Krupp J.C. COVID-19, virtual interviews, and the selection quandary: how a program's digital footprint influences the plastic surgery match. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147(4):727e–728e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000007723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenwell O.K., Mahoney B.P., Rosenblatt M.A. A response to the challenges of virtual interviews and recruitment in the era of COVID-19. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(1):134–136. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-20-01288.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Granger C.J., Khosla A., Osei D.A., Dy C.J. Optimizing the virtual interview experience for hand surgery fellowships. J Hand Surg Am. 2022;47(4):379–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2021.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heaps B.M., Dugas J.R., Limpisvasti O. The impact of COVID-19 on orthopedic surgery fellowship training: a survey of fellowship program directors. HSS J. 2022;18(1):105–109. doi: 10.1177/15563316211012006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Match process FAQs Application Cycle; 2022 to 2023. American Council of Academic Plastic Surgeons. https://acaplasticsurgeons.org/Resources/match-faq.cgi#:∼:text=Does%20ACAPS%20have%20a%20policy,on%20interviews%20for%202022%2D2023

- 19.AAMC interview guidance for the 2022-2023 residency cycle The Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/about-us/mission-areas/medical-education/aamc-interview-guidance-2022-2023-residency-cycle

- 20.Match result statistics: Hand Surg. National Resident Matching Program. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Hand-Surgery-MRS-Report.pdf

- 21.Hampshire K., Shirley H., Teherani A. Interview without harm: reimagining medical training's financially and environmentally costly interview practices. Acad Med. 2023;98(2):171–174. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000005000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang S., Denham Z., Ungerman E.A., et al. Do lower costs for applicants come at the expense of program perception? A cross-sectional survey study of virtual residency interviews. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14(6):666–673. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-22-00332.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ponterio J.M., Levy L., Lakhi N.A. Evaluation of the virtual interviews for resident recruitment due to COVID-19 travel restrictions: a nationwide survey of US senior medical students. Fam Med. 2022;54(10):776–783. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2022.592364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silvestre J., Chang B., Wilson R.H. Charting outcomes in the hand surgery fellowship match. J Hand Surg Am. 2024;49(3):280.e1–280.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2022.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]