Abstract

Background

Most people living with HIV (PLWH) are sedentary. This study aimed to synthesize the findings of qualitative studies to understand barriers and facilitators of physical activity (PA) among PLWH, categorized using the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behavior (COM-B) model and Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF).

Methods

Systematic searches of four databases were conducted to identify eligible studies. Thematic synthesis was used to inductively code, develop, and generate themes from the barriers and facilitators identified. Inductive data-driven themes were deductively categorized using the relevant domains of the COM-B model and the TDF.

Results

Fourteen articles were included. The most prominent TDF domain for barriers was skills, particularly symptoms/health issues such as fatigue and pain, while the most prominent TDF domain for facilitators was reinforcement, particularly experiencing benefits from PA.

Conclusion

The breadth of factors identified suggests the need for comprehensive strategies to address these challenges effectively and support PLWH in adopting and sustaining PA routines.

Keywords: physical activity, HIV, barriers, facilitators, qualitative review

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 39 million people worldwide were estimated to be living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) by the end of 2022; in the United States, the number is approximately 1.2 million. 1 Due to the introduction of effective antiretroviral therapy (ART), life expectancy in people living with HIV (PLWH) has significantly improved, leading to HIV being increasingly considered a chronic disease. 2 While the life expectancy of PLWH has increased, they tend to live with a higher burden of chronic diseases. 3 Compared to their non-HIV-infected counterparts, PLWH are at an elevated risk for various comorbid conditions, including cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and cognitive impairment, primarily due to prolonged HIV-associated inflammation, psychological distress, and side effects of ART.4,5 Studies have shown that PLWH are 50% more likely to develop CVD 6 and 58% more likely to develop dementia, 7 conditions that can often interfere with medication adherence 8 and are associated with higher mortality rates. 9

Physical activity (PA) is an established lifestyle intervention that plays a crucial role in promoting overall well-being. 10 Among PLWH, substantial research evidence has revealed the benefits of PA, including increased fitness, improved cardiovascular outcomes, enhanced mental health, and better quality of life. 11 To achieve substantial health benefits, PA needs to be performed regularly and maintained across the lifespan. The WHO guidelines recommend at least 150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic PA per week, along with muscle-strengthening activities on two or more days per week. 12 However, globally 50% to 80% of PLWH do not meet the guidelines.13-15 To encourage participation in PA among PLWH, understanding barriers and facilitators of participation in PA in PLWH is an essential first step.

A series of studies have employed quantitative methodologies to identify correlates of participation in PA in PLWH, as exemplified in a recent quantitative systematic review by Vancampfort et al. 16 Their review included 45 survey studies and highlighted factors associated with PA participation among PLWH. Older age, lower educational level, decreased CD4+ T cells/mm3, exposure to antiviral therapy, body pain, and depression emerged as primary barriers to PA. Conversely, higher cardiorespiratory fitness, greater self-efficacy, perceived benefits, and enhanced health motivation were identified as significant facilitators of PA. Although these quantitative studies have generated important objective correlates of PA, they do not allow in-depth consideration of barriers and enablers that are important to participants. To complement this understanding, qualitative research methodologies can offer valuable insights into participants’ perspectives. 17 Over the past decade, emerging studies have used qualitative investigations to understand the PLWH's views on barriers and enablers of PA participation. However, a synthesis of these qualitative studies is still lacking to produce larger interpretive representations of studies examined and to inform health-related policy and practice.

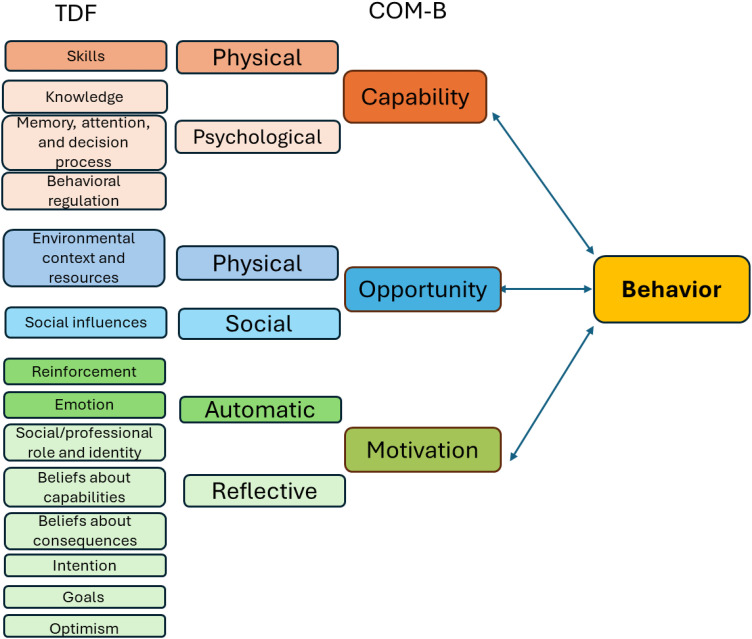

The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) encompasses 14 theoretical domains synthesized from 33 behavior change theories and 84 theoretical constructs in a single framework. 18 This framework comprehensively explores influences on behaviors and aligns with the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behavior (COM-B) model, delineating how capability, opportunity, and motivation interact to shape behavior (Figure 1). 19 By aligning the TDF with COM-B, one can elucidate how TDF domains interplay to impact behavior, facilitating the identification of potential behavior change techniques to inform interventions. The TDF is recommended for identifying and categorizing barriers and facilitators to behavior change and has been widely applied in clinical and community settings.20,21 It has been increasingly used in systematic reviews as a structured coding framework for understanding barriers and facilitators of behavior change.22,23

Figure 1.

The COM-B (capability-opportunity-motivation-behavior) and TDF (theoretical domains framework) matrix.

To provide guidance to policymakers and health care professionals, this study aimed to undertake a qualitative systematic review to understand barriers and facilitators influencing the participation of PA among PLWH, categorizing these using the TDF domains. The outcomes of this study will complement quantitative evidence, enhancing our comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing PA engagement among PLWH. Additionally, it will offer valuable insights for developing interventions, providing strategies to address the unique challenges that PLWH face in maintaining an active lifestyle.

Methods

This review was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (CRD42024516815) and is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Supplemental File 1).

Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria for this review were: (1) a diagnosis of HIV, regardless of the assessment method used, (2) participants aged 18 years or older, (3) studies utilizing qualitative research methods, and (4) studies investigating the barriers and facilitators of PA participation. For this review, a barrier was defined as “a circumstance or obstacle that keeps people or things apart or prevents communication or progress,” while a facilitator was defined as “a person or thing that makes something possible.” 24 Studies were excluded if they were not published in peer-reviewed journals or not written in English.

Search Strategy

A systematic search was conducted on February 29, 2024. Four databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL, SPORTDiscus, and EMBASE) were searched from inception to present. Search terms included “HIV,” “human immunodeficiency virus,” “AIDS,” “acquired immunodeficiency syndrome,” “Physical activity,” “Exercise,” “Walking,” “Activities of daily living,” “Barrier,” “Obstacle,” “Challenge,” “Facilitator,” “Enabler,” “Determinant,” “Influences,” “Attitudes,” “Experiences,” and “Adherence.” Two review authors (DS and YJY) independently conducted the literature search. Any discrepancies were resolved by a third review author (JW). The full search strategies for Medline are presented in Supplemental File 2.

Methodological Quality Appraisal

The quality assessment was conducted using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program checklist for qualitative studies. 25 The assessment covered domains such as research design, sampling and selection bias, attrition bias, performance bias, data collection, data analysis, and ethical considerations (Supplemental File 3). Each domain was evaluated by answering questions, with responses categorized as positive (+), negative (−), or not reported (NR). Quality was rated as strong (no risk of bias or risk of bias in one of the assessed domains), moderate (risk of bias in two domains), or weak (risk of bias in three or more domains). DS and YJY independently conducted the quality assessment. Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved, and consensus was reached on the final quality assessment ratings by both reviewers.

Data Collection

For each eligible study, study characteristics, participant's characteristics, and reported barriers and facilitators to PA were extracted using a self-designed standardized form. DS extracted data from all included studies, and YJY reviewed the extraction. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Data Synthesis

Data were analyzed and synthesized using a data-driven bottom-up approach. Thomas and Harden's method of thematic synthesis 26 was employed to inductively code, develop, and generate themes from the barriers and facilitators identified across the included studies. Inductive data-driven themes were deductively categorized using the relevant domains of the COM-B model and the TDF. Frequency of reporting was utilized to determine how often the barriers and facilitators were discussed across the included studies. Two review authors (DS and YJY) independently coded the barriers and facilitators identified in the included studies to the relevant COM-B constructs and TDF domains, guided by the operational definitions prespecified by the authors (DS and YJY) (Supplemental File 4), based on definitions from Cane et al. 18 Any discrepancies were resolved by a third review author (JW).

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

Ethics approval and informed consent were not required for this systematic review.

Results

Study Selection

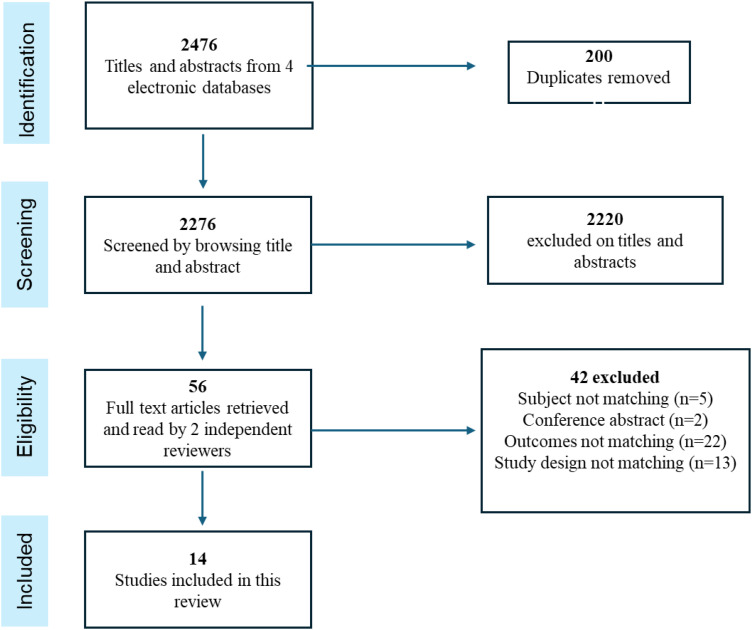

The search yielded 2476 articles; after removing duplicates, 2276 remained. Following title and abstract screening, 56 were assessed for full-text review, leading to the exclusion of 42 articles (Figure 2). A total of 14 articles were included in the systematic review.27-40

Figure 2.

Literature search flowchart.

Study and Participant Characteristics

A description of the included studies is presented in Table 1. Out of the 14 qualitative studies included, focus group methods were utilized in six studies,27,29-31,35,38,40 while semistructured interview methods were employed in another six studies.28,29,33,34,36,39 One study utilized both focus groups and semistructured interviews, 37 while one study 35 did not specify the method used. Half of these studies (n = 7) were conducted in the United States,27,30,31,35,36,38,40 three in Canada,33,34,39 three in Africa,28,32,37 and one in France. 29 Most of the included studies (n = 12) focused on participants’ perceptions regarding general PA and walking. Only two studies33,34 specifically inquired about PLWH's perceptions regarding community-based structured exercise. Across all 14 studies, a total of 524 PLWH were included, with 43% being female. Among the 12 studies that reported the mean or median age, the range of mean or median ages spanned from 38.7 to 57 years old.

Table 1.

Study and Participant Characteristics (n = 14).

| Study (first author, year) Country | Study design | Participant demographics | Type of PA | Methodological quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capili, 2014 United States |

Qualitative (focus groups) | n = 123 age (y): mean = 48 (SD ±7.3) % female: 40 |

General PA | Strong |

| Roos, 2015 South Africa |

Qualitative (not specified) | n = 42 age (y): mean = 38.7 (SD ±8.9) % female: 83.3 |

Walking program | Weak |

| Webel, 2017 United States |

Qualitative (focus groups) | n = 135 age (y): mean = 48 (SD ±10.8) % female: 49.6 |

General PA | Moderate |

| Montgomery, 2017 Canada |

Qualitative (semistructured interviews) | n = 11 age (y): median = 52 (48–60) % female: 36 |

Community-based structured exercise | Strong |

| Li, 2017 Canada |

Qualitative (semistructured interviews) | n = 7 age (y): not reported % female: 0 |

Community-based structured exercise | Strong |

| Vader, 2017 Canada |

Qualitative (semistructured interviews) | n = 14 age (y): median = 50 (46–53) % female: 35 |

General PA | Strong |

| Quigley, 2019 United States |

Qualitative (semistructured interviews) | n = 12 age (y): mean = 56.6 (SD ±8.8) % female: 25 |

General PA | Strong |

| Neff, 2019 United States |

Qualitative (focus groups) | n = 19 age (y): mean = 56.9 (SD ±5.4) % female: 0 |

General PA | Strong |

| Johs, 2019 United States |

Qualitative (focus groups) | n = 29 age (y): median = 57 (53–61) % female: 14% |

General PA | Strong |

| Henry, 2019 United States |

Qualitative (focus groups) | n = 20 age (y): mean = 54.5(SD ±7.2) % female: 20% |

Walking | Strong |

| Gray, 2021 France |

Qualitative (semistructured interviews) | n = 15 age (y): mean = 46.6 (SD ±10.3) % female: 53% |

General PA | Strong |

| Chetty, 2022 South Africa |

Qualitative (semistructured interviews) | n = 13 age (y): above 50 % female: 44% |

General PA | Strong |

| Kitilya, 2023 Tanzania |

Qualitative (semistructured interviews and focus groups) | n = 43 age (y): range:18–65 % female: 53.5% |

General PA | Strong |

| Sanabria, 2023 United States |

Qualitative focus groups | n = 41 age (y): mean = 50 (SD ±10.1) % female: 37% |

Walking | Strong |

Abbreviation: PA, physical activity.

Quality Assessment

Overall, the 14 included studies demonstrated satisfactory quality. Among them, 12 studies exhibited a risk of bias in one of the ten assessed domains. One study 38 demonstrated a risk of bias in two assessed domains. Only one study 37 showed a risk of bias in four domains. The most prevalent risk of bias was observed in the relationship between the researcher and participants, with only one study clearly describing their approach to reflexivity. 39 Details of quality assessment can be found in Supplemental File 3.

Barriers

As shown in Table 2, all the identified barriers were relevant to all the COM-B constructs and to 11 of the 14 TDF domains (skills; knowledge; memory, attention, and decision process; behavioral regulation, environmental context and resources; social influences; beliefs about capabilities; beliefs about consequences; social/professional role and identity; intentions; emotion).

Table 2.

Barriers to Physical Activity Identified Across the Included Studies (N = 14).

| Themes | Frequency | Citation(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Capability-related barriers | ||

| C1: Physical capability | ||

| C1.1 Symptoms/health issues (TDF: skills) | ||

| C1.1.1: Fatigue/low energy | 6 | 28, 29, 31, 33, 35, 37 |

| C1.1.2: Pain | 4 | 28, 29, 35, 39 |

| C1.1.3: Medication side effects | 2 | 31, 36 |

| C1.1.4: Limited fitness capacity | 3 | 29,35,36 |

| C1.1.5: Digestive symptoms | 3 | 29,31,33 |

| C1.1.6: Comorbidities and injuries | 4 | 36,31,33,34 |

| C1.1.6: Respiratory symptoms | 2 | 29,31 |

| C1.1.7: Aging | 1 | 37 |

| C1.1.8: Dermatological symptoms | 1 | 31 |

| C1.1.9: Stress | 1 | 38 |

| C1.2 Substance use (TDF: skills) | 1 | 34 |

| C2: Psychological capability | ||

| C2.1 Lack of knowledge (TDF: knowledge) | ||

| C2.1.1: Lack of familiarity with physical activity | 3 | 29,35,36 |

| C2.1.2: Lack of understanding regarding the equipment use | 1 | 36 |

| C2.2 Difficult to memorize a routine (TDF: memory, attention, decision processes) | 1 | 36 |

| C2.3 falling out of an exercise routine (TDF: behavioural regulation) | 1 | 33 |

| Opportunity-related barriers | ||

| O1: Physical opportunity | ||

| O1.1 Lack of time (TDF: environmental context and resources) | 7 | 28,29,30,31,32,33,35,37 |

| O1.2 Lack of education/instructions/advice from professionals and the community (TDF: environmental context and resources) | 4 | 28, 32, 33, 36 |

| O1.3 Lack of tailored programs | ||

| O1.2.1: Lack of comfort at gym | 2 | 31,35 |

| O1.2.2: Lack of adaptive programs | 1 | 28 |

| O1.3 Environmental factors (TDF: environmental context and resources) | ||

| O1.3.1: Availability of, or access to, facilities or programs | 3 | 28, 32, 36 |

| O1.3.2: Weather | 3 | 34, 36, 37 |

| O1.3.3: Noise at the gym | 1 | 32 |

| O1.3.4: Crime (being active outdoors) | 1 | 37 |

| O2: Social opportunity | ||

| O2.1: Socioeconomic factors (TDF: social influences) | ||

| O2.1.1: Financial constraints, travel requirements, or work obligations | 6 | 31, 32, 33, 35, 36, 37 |

| O2.1.2: Lack of company or social support | 4 | 29, 31, 32, 33 |

| O2.1.3: Negative life events | 1 | 33 |

| O2.2 HIV-related stigma (TDF: social influences) | 3 | 28, 34, 36 |

| Motivation-related barriers | ||

| M1: Automatic motivation | ||

| M1.1: Psychological barriers (TDF: emotion) | ||

| M1.1.1: Lack of motivation/interest | 5 | 29, 31, 35, 36, 37 |

| M1.1.2: Anxiety/ depression/burnout | 1 | 36 |

| M2: Reflective motivation | ||

| M2.1: Fear of harm (TDF: beliefs about consequences) | ||

| M2.1.1: Fear of injury | 2 | 36, 39 |

| M2.1.2: Fear of falling | 1 | 39 |

| M2.1.2: Fear of germs or infection | 1 | 29 |

| M2.1.3: Fear of worsening condition due to physical activity | 1 | 32 |

| M2.2: Lack of self-efficacy (TDF: beliefs about capabilities) | 3 | 31, 35, 36 |

| M2.3: Physical activity is not a priority (TDF: intentions) | 1 | 29 |

| M2.4: Identity-related factors (TDF: psychosocial/professional role and identity) | ||

| M2.4.1: Small HIV community | 1 | 36 |

| M2.4.2: Fear of disclosure of HIV status | 1 | 35 |

Capability-Related Barriers

In terms of physical capability-related barriers, symptoms and health issues, including fatigue28,29,31,33,35,37 and pain,28,29,35,39 were the most frequently cited barriers to PA participation among PLWH. Other symptoms and health issues affecting their ability of PLWH to engage in PA included medication side effects,31,36 limited fitness capability,29,35,36 comorbidities,31,33,34,36 digestive issues,29,33 respiratory issues, 29 dermatological symptoms,37aging,31and stress. 38 Substance use was also identified as a barrier to PA in one study 34 (TDF skills). In terms of psychological capability-related barriers, lack of familiarity with PA35,36 and knowledge regarding the use of PA equipment 36 was identified as barriers (TDF knowledge). People living with HIV also expressed difficulty memorizing a routine 36 (TDF memory) and easily falling out of an exercise routine 33 (TDF behavioral regulation) as additional barriers to engaging in PA.

Opportunity-Related Barriers

In terms of physical opportunity-related barriers, the most frequently cited barrier to PA among PLWH was lack of time.28,29,31-33,35,37 People living with HIV also expressed the lack of tailored programs,28,3135and instructions from providers28,32,33,36 as barriers within this domain. Lack of access to and availability of facilities28,32,36 were identified as additional barriers. Other environmental-related barriers included weather,34,36,37 and noise at the gym 32 (TDF environmental context and resources). In terms of social opportunity-related barriers, financial constraints31-33,35-37 and lack of company or social support29,31-33 were cited most frequently by participants, followed by HIV-related stigma,28,34,36 unsafe neighborhood, 37 and negative life events 33 (TDF social influences).

Motivation-Related Barriers

Automatic motivation-related barriers include lack of motivation29,31,35-37 and anxiety/depression/burnout 36 (TDF emotion). In terms of reflective motivation-related barriers, fear of harm associated with PA29,32,36,39 (TDF beliefs about consequences) and lack of self-efficacy31,35,36 (TDF beliefs about capabilities) were the most cited barriers. People living with HIV also expressed PA is not a priority in life 29 (TDF intention). Additionally, identity-related barriers included fear of disclosure of HIV status 35 and lack of cohesiveness within the small HIV community 36 (TDF social/professional role and identity).

Facilitators

As shown in Table 3, all the identified facilitators were relevant to all the COM-B constructs and all the 14 TDF domains.

Table 3.

Facilitators of Physical Activity Identified Across the Included Studies (n = 14).

| Themes | Frequency | Citation(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Capability-related facilitators | ||

| C1: Physical capability (TDF: skills) | ||

| C1.1 Improved symptoms | ||

| C1.1.1: Reduced fatigue | 2 | 39, 31 |

| C1.1.2: Reduced pain | 1 | 29 |

| C2: Psychological capability | ||

| C2.1. Knowledge of physical activity (TDF: knowledge) | ||

| C2.1. 1 Knowledge of importance of physical activity | 2 | 29, 32 |

| C2.1.2 Knowledge of how to perform physical activity | 1 | 34 |

| C2.2. Lack of adverse effects of cognitive problems on exercise (TDF domain: memory, attention, decision processes) | 1 | 36 |

| C2.2. Developing a routine of physical activity (TDF: behavioural regulation) | ||

| C2.2.1: Adjusting daily habits with time | 2 | 36, 40 |

| C2.2.2: Combining exercise with other behaviours | 1 | 35 |

| Opportunity-related facilitators | ||

| O1: Physical opportunity | ||

| O1.1 Environmental support (TDF: environmental context and resources) | ||

| O1.1.1: Availability of facilities | 3 | 32, 34, 35 |

| O1.1.2: Walkable community environment | 1 | 37 |

| O1.1.3 Leisure activities as a driver (ie gardening) | 1 | 28 |

| O1.1.4 Convenient and fun activities | 1 | 35 |

| O1.1.5 Warm weather | 1 | 34 |

| O1.1.6 Nonjudgmental training atmosphere | 1 | 34 |

| O1.2 Technology support (TDF: environmental context and resources) | 2 | 35, 36 |

| O1.2.1 Receiving feedback text messages | 1 | 30 |

| O1.2.2 Use of technology to monitor progress | 2 | 36, 40 |

| O1.3 Financial support (TDF: environmental context and resources) | 2 | 29, 34 |

| O1.4 Tailored programs (TDF: environmental context and resources) | ||

| O1.4.1 Individualized programs adapted to fatigue and other concurrent conditions | 3 | 27, 29, 39 |

| O1.4.2 Graded and gradual approach | 1 | 39 |

| C1.5.1 Advice and education from healthcare providers | 2 | 33, 39 |

| O1.5.2 Inspiring fitness instructor | 1 | 34 |

| O1.5.3 Knowledgeable healthcare or fitness professionals | 1 | 33 |

| O2: Social opportunity | ||

| O2.1: Social support (TDF: social influences) | ||

| O2.1.1: Companion or encouragement from family/friends | 10 | 27, 28, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 36, 37, 40 |

| O2.1.2: Social ties/involvement in an organization | 4 | 28, 29, 31, 37 |

| O2.1.3: Pet to walk | 1 | 29 |

| Motivation-related facilitators | ||

| M1: Automatic motivation | ||

| M1.1: Acquired physical health benefits (TDF: reinforcement) | ||

| M1.1.1: Reduced fatigue/increased energy | 6 | 29, 31, 32, 34, 36, 39 |

| M1.1.2: Improved functional capability | 6 | 28, 33, 34, 35, 36, 39 |

| M1.1.3: Clearer thinking | 3 | 31, 34, 39 |

| M1.1.4: Better sleep | 1 | 34 |

| M1.2: Acquired mental health benefits (TDF: reinforcement) | ||

| M1.2.1: Improved mood | 6 | 31, 33,34,35, 36, 39 |

| M1.2.2: Elevate motivation | 1 | 33 |

| M1.3: Acquired social benefits (TDF: reinforcement) | ||

| M1.3.1: Improved relationship with family members and friends | 1 | 34 |

| M1.3.2: Prevention of isolation | 3 | 33, 35, 39 |

| M1.4: Enjoyment (TDF: emotion) | ||

| M1.4.1: Interest or enjoyment in participating | 4 | 28, 29, 33, 35 |

| M1.4.2: Sense of accomplishment | 2 | 31, 34 |

| M1.5: Viewing HIV manageable trough PA (TDF: Social/professional/identity) | ||

| M1.5.1: HIV diagnosis has reinforced positive behaviours | 1 | 36 |

| M1.5.2: Physical activity to normalization | 1 | 29 |

| M1.5.2: Accountability toward oneself and HIV group | 1 | 34 |

| M2: Reflective motivation | 1 | 35 |

| M2.1: Self-efficacy (TDF: beliefs about capabilities) | 5 | 29, 32, 34, 35, 40 |

| M2.2: Positive attitude and confidence (TDF: optimism) | ||

| M2.2.1: Confidence in maintaining/initiating new exercise routine | 1 | 36 |

| M2.2.2: Positive attitude | 1 | 27 |

| M2.3: Perceptions of benefits of physical activity (TDF: beliefs about consequences) | ||

| M2.3.1: Improved physical condition | 3 | 29, 32, 36 |

| M2.3.2: Reducing the effects of aging | 1 | 29 |

| M2.4: Goal setting (TDF: goals) | ||

| M2.4.1: Reach the goal/goal achievement (step, weight loss) | 4 | 29, 31, 36, 40 |

| M2.4.2: Have a goal | 3 | 29, 33, 32 |

| M2.4.3: Goal monitoring | 2 | 34, 40 |

| M2.5: Motivators (TDF: intention) | ||

| M2.5.1 Desire to stay healthy | 3 | 31, 36, 40 |

| M2.5.2: To have social interaction | 2 | 36, 34 |

| M2.5.3: To resist aging | 1 | 34 |

| M2.5.4: Want to look better | 1 | 35 |

| M2.5.5: To get out of the house/ stay busy | 1 | 35 |

| M2.5.6: Physical activity as a distraction | 1 | 29 |

| M2.5.7: To attract admiration | 1 | 29 |

| M2.6: Intention (TDF: intention) | ||

| M2.6.1: Prioritizing physical activities over other activities | 2 | 36, 39 |

| M2.6.2: Physical activity is a therapy | 2 | 29, 34 |

| M2.6.2: Physical activity is an integral part of daily life | 1 | 39 |

| M2.6.3: Having an active lifestyle | 1 | 33 |

Capability-Related Facilitators

Physical capability-related facilitators included reduced fatigue and pain29,31 (TDF skills). In terms of psychological capability-related facilitators, awareness of the benefits of PA29,32 and knowledge of how to promote PA 34 were cited as facilitators to PA participation (TDF knowledge). The ability to develop a PA routine, including adjusting daily habits over time36,40 and combining PA with other behaviors, 35 was identified as a facilitator (TDF behavioral regulation). Additionally, the absence of adverse effects of cognitive problems on exercise was identified as a facilitator (TDF memory, attention, decision processes).

Opportunity-Related Facilitators

The physical opportunity-related facilitators included environmental opportunity such as availability of facilities,32,34,35 walkable community environment, 37 leisure 28 and convenient activities, 35 favorable weather, 34 and a nonjudgmental training atmosphere. 34 Tailored PA programs adapted to fatigue or other concurrent conditions27,29,39 and a gradual approach, 39 as well as technology support such as feedback messages 30 and technology-empowered self-monitoring36,40 were also facilitators. Professional's support33,34,39 and financial support29,34 (TDF environmental context and resources) were also noted. In terms of social opportunity, social support from family and friends,27-29,31,32,34-37,40 involvement in an organization,28,29,31,37 and having a pet 29 were identified as significant facilitators to PA participation (TDF social influences).

Motivation-related facilitators

In terms of automatic motivation-related facilitators, experiencing the physical benefits of being active was the most cited motivator for PLWH (TDF reinforcement). These benefits included reduced fatigue/increased energy,29,31,32,34,36,39 improved functional capability,28,33-36,39 clearer thinking,31,34,39 and better sleep. 34 Mental health benefits such as improved mood31,33-36,39 and elevated motivation, 33 as well as social benefits such as prevention of isolation33,34,39 and improved relationship, 34 were also noted. Some PLWH expressed interest or enjoyment28,29,33,35 and a sense of accomplishment31,34 in being physically active (TDF emotion), viewing PA as a crucial self-management component27,32,34 (TDF social/professional/identity). A positive attitude toward PA27,36 was also identified as a facilitator (TDF optimism). In terms of reflective motivation-related facilitators, self-efficacy29,32,34,35,40 was frequently cited as a facilitator to engaging in PA (TDF beliefs about capabilities). Goal setting as a behavioral change strategy was used by some PLWH to facilitate PA engagement29,31,36,40 (TDF goals). Belief in the health benefits of PA29,32,36 was also a strong facilitator. Motivators to PA participation included desire to stay healthy,31,36,40 social interaction,34,36 resistance to aging, 34 aesthetics, 35 admiration, 29 and distraction. 29 Moreover, some PLWH expressed an intention to participate in PA because they prioritized it over other activities,36,39 integrated it into their daily lives 39 and therapy routines,29,34 and maintained an active lifestyle as a personal norm 33 (TDF intention).

Discussion

This systematic review represents the first comprehensive synthesize of qualitative research on barriers and facilitators to PA among PLWH, mapping these factors to the COM-B and TDF. Our findings underscore the multifaceted nature of factors influencing PA engagement, which can act as both barriers and facilitators depending on individual contexts. Importantly, facilitators identified by PLWH inform strategies aimed at supporting PA engagement.

Regarding barriers, the most prominent TDF domain identified was skills, particularly symptoms and health issues such as fatigue and pain. These findings align with a previous quantitative systematic review of PA correlates for PLWH 16 indicating that physical capability-related barriers among PLWH, including comorbidities, treatment side effects, and pain, consistently hinder PA among PLWH. People living with HIV advocated for tailored PA programs accommodating their physical capabilities,27,29,39 viewing these as facilitators to PA. The domain of environmental context and resources emerged as the second most prominent barrier, highlighting issues such as inadequate facilities and time constraints. Addressing this domain through resource provision, including facilities and tailored programs, is crucial. 41 Additionally, wearable devices and mobile phones were endorsed as potential facilitators for future PA programs.30,36,40

Social influence was the third most prominent barrier domain, with lack of social support being a significant hindrance. Conversely, positive social support from family and friends emerged as the most cited facilitator to PA perceived, underscoring the importance of educating support networks about PA's benefits.

In terms of facilitators, reinforcement, social influences, and environmental context and resources were the most prominent TDF domains. Experiencing benefits from PA, such as improvements in physical health, mental well-being, and social connections, was highlighted as a crucial form of reinforcement. This positive reinforcement also influenced intention and optimism, as per the COM-B model, 19 suggesting that emphasizing positive outcomes and providing role model experiences could enhance engagement. Goal setting emerged as another prominent facilitator, emphasizing its role as a key behavioral change strategy. 42

Strengths and Limitations

Regarding strengths, firstly, this study complements the findings of previous reviews that focused solely on quantitative studies by including qualitative research. This inclusion deepens the understanding of the barriers and facilitators of PA engagement from the perspective of PLWH. Additionally, the application of a theoretical framework to classify the barriers and facilitators impacting PLWH's PA engagement enhances the robustness of this review. This systematic approach may aid researchers and professionals in selecting appropriate behavioral change techniques for designing future PA programs.

As for limitations, firstly, most studies were conducted in North America. This regional focus may limit the generalizability of findings, as barriers and facilitators of PA for PLWH in other jurisdictions could differ. Additionally, since many included qualitative studies utilized thematic analysis, our coding of barriers and facilitators may be constrained by the interpretations and analyses of the primary studies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this qualitative systematic review advances our understanding of theoretical factors influencing PA among PLWH. Given the challenges of inadequate PA guideline adherence among PLWH, these findings provide actionable insights for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to develop targeted, theory-based interventions supporting PA adoption and maintenance among PLWH.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-doc-1-jia-10.1177_23259582241275819 for Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity in People Living With HIV: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies by Dan Song, Lisa Hightow-Weidman, Yijiong Yang and Jing Wang in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-jia-10.1177_23259582241275819 for Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity in People Living With HIV: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies by Dan Song, Lisa Hightow-Weidman, Yijiong Yang and Jing Wang in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-jia-10.1177_23259582241275819 for Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity in People Living With HIV: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies by Dan Song, Lisa Hightow-Weidman, Yijiong Yang and Jing Wang in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-jia-10.1177_23259582241275819 for Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity in People Living With HIV: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies by Dan Song, Lisa Hightow-Weidman, Yijiong Yang and Jing Wang in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Dan Song https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8185-1397

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. 2023. HIV statistics, globally and by WHO region, 2023. Retrieved March 31, 2024.

- 2.Sarma P, Cassidy R, Corlett S, Katusiime B. Ageing with HIV: medicine optimisation challenges and support needs for older people living with HIV: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2023;40(3):179-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris TG, Rabkin M, El-Sadr WM. Achieving the fourth 90: healthy aging for people living with HIV. AIDS. 2018;32(12):1563-1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nou E, Lo J, Grinspoon SK. Inflammation, immune activation, and cardiovascular disease in HIV. AIDS. 2016;30(10):1495-1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aung HL, Kootar S, Gates TM, Brew BJ, Cysique LA. How all-type dementia risk factors and modifiable risk interventions may be relevant to the first-generation aging with HIV infection? Eur Geriatr Med. 2019;10(2):227-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruamtawee W, Tipayamongkholgul M, Aimyong N, Manosuthi W. Prevalence and risk factors of cardiovascular disease among people living with HIV in the Asia-Pacific region: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lam JO, Hou CE, Hojilla JC, et al. Comparison of dementia risk after age 50 between individuals with and without HIV infection. AIDS. 2021;35(5):821-828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel S, Parikh NU, Aalinkeel R, et al. United States national trends in mortality, length of stay (LOS) and associated costs of cognitive impairment in HIV population from 2005 to 2014. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(10):3198-3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naveed Z, Fox HS, Wichman CS, et al. Neurocognitive status and risk of mortality among people living with human immunodeficiency virus: an 18-year retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):3738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ. 2006;174(6):801-809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaggers JR, Hand GA. Health benefits of exercise for people living with HIV: a review of the literature. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2016;10(3):184-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1451-1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vancampfort D, Mugisha J, De Hert M, et al. Global physical activity levels among people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(4):388-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safeek RH, Hall KS, Lobelo F, et al. Low levels of physical activity among older persons living with HIV/AIDS are associated with poor physical function. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2018;34(11):929-935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harsono D, Deng Y, Chung S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of physical inactivity among individuals with HIV during the first COVID-19 wave: a cross-sectional survey. AIDS Behavior. 2024;28(5):1531-1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vancampfort D, Mugisha J, Richards J, De Hert M, Probst M, Stubbs B. Physical activity correlates in people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review of 45 studies. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(14):1618-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phoenix M, Nguyen T, Gentles SJ, VanderKaay S, Cross A, Nguyen L. Using qualitative research perspectives to inform patient engagement in research. Res Involv Engagem. 2018;4(20):1-5. doi: 10.1186/s40900-018-0107-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuti T, Nzinga J, Njoroge M, et al. A systematic review of electronic audit and feedback: intervention effectiveness and use of behaviour change theory. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):1-20. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0590-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, et al. A guide to using the theoretical domains framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):1-18. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mather M, Pettigrew LM, Navaratnam S. Barriers and facilitators to clinical behaviour change by primary care practitioners: a theory-informed systematic review of reviews using the theoretical domains framework and behaviour change wheel. Syst Rev. 2022;11(1):180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richardson M, Khouja CL, Sutcliffe K, Thomas J. Using the theoretical domains framework and the behavioural change wheel in an overarching synthesis of systematic reviews. BMJ open. 2019;9(6):e024950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oxford Dictionaries. n.d. In University Oxford.

- 25.Buccheri RK, Sharifi C. Critical appraisal tools and reporting guidelines for evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2017;14(6):463-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(45):1-10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Capili B, Anastasi JK, Chang M, Ogedegbe O. Barriers and facilitators to engagement in lifestyle interventions among individuals with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2014;25(5):450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chetty L, Cobbing S, Chetty V. The perceptions of older people living with hiv/aids towards physical activity and exercise. AIDS Res Ther. 2022;19(1):67. 10.1186/s12981-022-00500-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gray L, Schuft L, Bergamaschi A, Filleul V, Colson SS, d’Arripe-Longueville F. Perceived barriers to and facilitators of physical activity in people living with HIV: a qualitative study in a French sample. Chronic Illn. 2021;17(2):111-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henry BL, Quintana E, Moore DJ, Garcia J, Montoya JL. Focus groups inform a mobile health intervention to promote adherence to a Mediterranean diet and engagement in physical activity among people living with HIV. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johs NA, Kellar-Guenther Y, Jankowski CM, Neff H, Erlandson KM. A qualitative focus group study of perceived barriers and benefits to exercise by self-described exercise status among older adults living with HIV. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e026294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitilya B, Sanga E, PrayGod G, et al. Perceptions, facilitators and barriers of physical activity among people living with HIV: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1-12. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15052-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li A, McCabe T, Silverstein E, et al. Community-based exercise in the context of HIV: factors to consider when developing and implementing community-based exercise programs for people living with HIV. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2017;16(3):267-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montgomery CA, Henning KJ, Kantarzhi SR, Kideckel TB, Yang CF, O'Brien KK. Experiences participating in a community-based exercise programme from the perspective of people living with HIV: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(4):e015861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neff HA, Kellar-Guenther Y, Jankowski CM, et al. Turning disability into ability: barriers and facilitators to initiating and maintaining exercise among older men living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2019;31(2):260-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quigley A, Baxter L, Keeler L, MacKay-Lyons M. Using the theoretical domains framework to identify barriers and facilitators to exercise among older adults living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2019;31(2):163-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roos R, Myezwa H, van Aswegen H. “Not easy at all but I am trying”: barriers and facilitators to physical activity in a South African cohort of people living with HIV participating in a home-based pedometer walking programme. AIDS Care. 2015;27(2):235-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Webel AR, Perazzo JD, Dawson-Rose C, et al. A multinational qualitative investigation of the perspectives and drivers of exercise and dietary behaviors in people living with HIV. Appl Nurs Res. 2017;37(4):13-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vader K, Simonik A, Ellis D, et al. Perceptions of ‘physical activity’ and ‘exercise’ among people living with HIV: a qualitative study. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2017;24(11):473-482. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanabria G, Bushover B, Ashrafnia S, Cordoba E, Schnall R. Understanding physical activity determinants in an HIV self-management intervention: qualitative analysis guided by the theory of planned behavior. JMIR Form Res. 2023;7:e47666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nau T, Smith BJ, Bauman A, Bellew B. Legal strategies to improve physical activity in populations. Bull World Health Organ. 2021;99(8):593-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pearson ES. Goal setting as a health behavior change strategy in overweight and obese adults: a systematic literature review examining intervention components. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87(1):32-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-doc-1-jia-10.1177_23259582241275819 for Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity in People Living With HIV: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies by Dan Song, Lisa Hightow-Weidman, Yijiong Yang and Jing Wang in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-jia-10.1177_23259582241275819 for Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity in People Living With HIV: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies by Dan Song, Lisa Hightow-Weidman, Yijiong Yang and Jing Wang in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-jia-10.1177_23259582241275819 for Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity in People Living With HIV: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies by Dan Song, Lisa Hightow-Weidman, Yijiong Yang and Jing Wang in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-jia-10.1177_23259582241275819 for Barriers and Facilitators of Physical Activity in People Living With HIV: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies by Dan Song, Lisa Hightow-Weidman, Yijiong Yang and Jing Wang in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)