Abstract

Background:

Jianpi Jiedu Recipe has been used to treat digestive tract tumors in China since ancient times, and its reliability has been proven by clinical research. Currently, the specific biological mechanism of JPJDR in treating tumors is unclear.

Methodology:

CCK-8 assay was used to detect cell viability. Clone formation assay and EdU assay were used to detect cell proliferation potential. DCFH-DA probe and JC-1 probe were used to detect total intracellular reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial membrane potential, respectively. Western blotting and immunofluorescence were used to detect protein expression level and subcellular localization of cells. The RFP-GFP-LC3B reporter system was used to observe the type of autophagy in cells. The xenograft tumor model was used to study the therapeutic effect of JPJDR in vivo.

Results:

JPJDR has an excellent inhibitory effect on various colorectal cancer cells and effectively reduces the proliferation ability of HT29 cells. After treatment with JPJDR, the amount of reactive oxygen species in HT29 cells increased significantly, and the mitochondrial membrane potential decreased. JPJDR induced the accumulation of autophagosomes in HT29 cells and was shown to be incomplete autophagy. At the same time, JPJDR reduced the expression of PD-L1. Meanwhile, JPJDR can exert an excellent therapeutic effect in xenograft tumor mice.

Conclusion:

JPJDR is a low-toxicity and effective anti-tumor agent that can effectively treat colon cancer in vitro and in vivo. Its mechanism may be inducing mitochondrial dysfunction and incomplete autophagy injury to inhibit the proliferation of colon cancer cells.

Keywords: jianpi jiedu recipe, incomplete autophagy, reactive oxygen species, colon cancer, PD-L1

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers globally, posing a significant threat to global public health. According to data from the American Cancer Society, an estimated 153 020 new cases of colorectal cancer will be diagnosed in 2023, and 52 550 people will die from the disease. 1 The 5-year survival rate for colorectal cancer is currently 58%-65%, which seems to be a comforting figure, as malignancies such as lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, and liver cancer currently have 5-year survival rates of less than 20%.1,2 However, this can only be partially attributed to the development of medical care, as the 5-year survival rate for colorectal cancer was 48%-51% in 1975, indicating that our treatment options for colorectal cancer remain limited. 1 Among patients diagnosed with metastatic colorectal cancer, fewer than 20% survive for more than 5 years. For unresectable metastatic colorectal cancer, chemotherapy is the mainstay of therapy, as drugs can often diffuse to various parts of the body. 3 Currently, there is a lack of specific markers to identify high-risk patients who may benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy, and the efficacy of chemotherapy is often limited. 4 Therefore, there is an urgent need to find new drugs for the treatment of colorectal cancer.

China has used traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) to treat tumors for thousands of years and has demonstrated significant efficacy. 5 Additionally, natural compounds often have a richer structural and biological profile, making them an increasingly attractive resource for drug development. 6 Numerous studies have shown that the integration of TCM into the clinical treatment of tumors can significantly enhance treatment outcomes and reduce the occurrence of chemotherapy-related side effects.7,8 Jianpi Jiedu Recipe (JPJDR) is a traditional Chinese medicine formula that is commonly used in China to treat gastrointestinal tumors. Recent studies have shown that JPJDR has the effects of inhibiting tumorigenesis, metastasis, and angiogenesis in colorectal cancer.9,10 However, the specific mechanism by which JPJDR inhibits colorectal cancer remains unclear. It is urgently needed to elucidate its specific pharmacological effects to further guide its clinical application.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are a by-product of oxygen metabolism in living organisms, and the most important one is peroxide, which has been shown to maintain and activate some signaling transduction in tumor cells, promoting tumor progression at multiple stages. 11 Current research indicates that increasing the production of active oxygen can effectively kill tumor cells on the basis of their original high levels of active oxygen. 12 However, tumor cells experiencing oxidative stress can inactivate excessive active oxygen through autophagy and dispose of some damaged organelles and proteins to maintain internal environment stability. 13 Therefore, clinical trials have reported that blocking autophagy by chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine combined with chemotherapy drugs can produce better therapeutic effects. 14 Even without the interference of autophagy inhibitors, some compounds-induced autophagosomes are unable to fuse with lysosomes. These compounds have strong inhibitory effects on tumor cells and are considered as compounds with potential for tumor therapy. 15 Some studies have shown that blocking autophagy can increase the expression of PD-L1 in gastric cancer. 16 Typically, high expression of PD-L1 helps tumor cells evade immunity. Chemotherapy or antibodies that reduce PD-L1 expression have shown great potential as a treatment strategy and have been used in clinical trials. 17 Although PD-L1 expression does not significantly correlate with the prognosis of colorectal cancer, 18 these results still suggest that blocking autophagy as a treatment strategy may hide some concerning risks. This study demonstrates that JPJDR plays a significant regulatory role in a series of cellular activities including active oxygen, mitochondrial membrane potential, autophagy, and PD-L1.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Jianpi Jiedu Decoction

The ingredients of JPJDR were purchased from Yancheng Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital and identified by traditional Chinese medicine practitioner Lingling Cheng. The following are the traditional Chinese names, Latin names, and dosages of the ingredients: “Huangqi” Astragalus membranaceus (Fisch.) Bunge 30 g; “Dangshen” Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 30 g; “Baizhu” Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g; “Zhuling” Polyporus umbellatus (Pers.) Fr. 15 g; “Yiyiren” Coix lacryma-jobi L. var.mayuen (Roman.) Stapf 15 g; “Bayuezha” Fruit of Fiverleaf Akebia 15 g; “Yeputaoteng” Vitis quinquangularis Rehd. 15 g; “Hongteng” Sargentodoxa cuneata. 15 g. The preparation of the drug was completed by Liangfeng Xu from the Pharmacy Department. All the herbs were soaked in water for 30 minutes and then boiled for 30 minutes. After filtering the drug liquid with gauze, it was poured into the beaker. Then, it was continuously heated and evaporated until only 100 ml of liquid remained. After that, it was centrifuged at 14 000g for 1 hour. The supernatant was collected, filtered through a 0.22 μm filter to sterilize, and stored at −80°C. The drug was then aliquoted and stored in this concentration of 1500 mg/ml.

Reagents and Antibodies

The Cell Counting Kit-8 (Catalog number: C0039), EdU Cell Proliferation Kit with Alexa Fluor 488 (Catalog number: C0071S), Enhanced mitochondrial membrane potential assay kit with JC-1 (Catalog number: C2003S), and Reactive Oxygen Species Assay Kit (Catalog number: S0033M) was purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (China). The following antibodies were all purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (USA): PCNA (Catalog number: 13110S), LC3B (Catalog number: 3868S), and P62 (Catalog number: 23214S). The following antibodies were all purchased from Proteintech Group (USA): GAPDH (Catalog number: 66248-1-Ig) and PD-L1 (Catalog number: 66248-1-Ig). The following reagents were all purchased from MedChemExpress (USA): Rapamycin (Catalog number: HY-10219) and Chloroquine (Catalog number: HY-17589A).

Cell Culture

HCT-116 (RRID: CVCL_0291), HT-29 (RRID: CVCL_0320), and SW480 (RRID: CVCL_0546) cells were purchased from Wuhan Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd (China). Cell culture was strictly carried out according to the manual provided by the company. HCT116 and HT29 cells were cultured in McCoy’s 5A (catalog number: PM150710), and SW480 was cultured in DMEM (catalog number: PM150210). The medium was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, 1009914C) without any antibiotics. Cells were placed in a constant temperature incubator with parameters set at 37°C, 5% CO2, and saturated humidity. The culture medium was changed every 2-3 days, and the cells were passaged once.

Cell Vitality Detection

The effect of JPJDR on cell viability was detected using the CCK-8 method. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates, with 10 000 cells per well, and incubated overnight. After the cells resumed their morphology the next day, the cells were treated with the specified concentration of drug for 24 or 48 hours. An appropriate amount of CCK-8 reagent was added to each well to make the working concentration 10%, and gently mixed. It was incubated in the incubator for 1 hour, and the optical density (OD) value of each well was measured using an enzyme microplate reader at a wavelength of 450 nm. The relative viability or inhibition rate of the cells was calculated based on the measured OD value.

Clone Formation

The clone formation assay was used to detect the long-term effect of JPJDR on colon cancer cells. Briefly, 800 colon cancer cells were counted after treatment with a specified concentration of JPJDR for 24 hours and inoculated into a 6-well plate. Then, the cells were cultured in a drug-free medium for 14 days, with the medium replaced every 3 days. After fixation with 3.7% paraformaldehyde, the cells were stained with 0.1% crystal violet, washed 5 times, and photographed.

Proliferation Detection

The proliferation rate of cells was accurately detected using the EdU method. Colon cancer cells were seeded in a 6-well plate, and when the morphology recovered and the cells grew to 60% confluence, and they were treated with a specified concentration of drug for 24 hours. EdU was added to the original culture medium at a 2-fold concentration to make it a 1-fold concentration. After culturing for another 2 hours, EdU was allowed to penetrate the replicating DNA. After fixing and permeabilizing the cells, a click reaction was performed to label EdU with Alexa Fluor 488. Finally, the cell nuclei were stained with DAPI and photographed.

Western Blot

The relative protein abundance in cells was detected by Western blotting. After treating the cells with JPJDR for 24 hours, cells were washed twice with PBS, and then lysed at 4°C for 30 minutes using RIPA. Cell lysate was collected and centrifuged at 14 000g for 30 minutes, and the protein concentration of each protein sample determined using the BCA method. The same amount of protein lysate and loading buffer was mixed in the appropriate ratio and heated at 100°C for 5 minutes to denature the protein thoroughly. The prepared protein sample was subjected to SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis, and then the protein was transferred to the PVDF membrane using horizontal electrophoresis. Five percent skimmed milk powder was used to block the gaps on the PVDF membrane, and it was washed with TBST 3 times, each for 5 minutes. The primary antibody is usually incubated overnight at 4°C (usually for more than 14 hours). The secondary antibody is usually incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. Images were then acquired in the imager using chemiluminescence.

Immunofluorescence

The cells were seeded on special glass slides (the thickness must be less than 0.17 mm) and cultured for 1-2 days to wait for the complete recovery of cell morphology. After 24 hours of treatment with JPJDR or control, the cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. The blocking process was carried out in 5% skimmed milk and incubated at room temperature for 2 hours. According to the instructions for the primary antibody, the primary antibody was diluted with the appropriate dilution buffer, and the blocking solution was aspirated with blotting paper. Each glass slide was dropped with the diluted primary antibody, placed in a humid box, and incubated overnight at 4°C. After incubating the primary antibody, the cells were washed 3 times in PBST solution for 5 minutes each time. After washing, the secondary antibody labeled with fluorescence was added. According to the instructions for the secondary antibody, it was diluted with the appropriate dilution buffer and added to the glass slide for incubation. After incubating the secondary antibody, the cells were washed again and then observed under a fluorescence microscope. Before observation, the glass slide was dropped with a fluorescence quenching agent, and then sealed.

ROS Detection

The determination of total intracellular ROS level was carried out by the DCFH-DA probe. The DCFH-DA probe itself has no fluorescence and can freely cross the cell membrane. After entering the cell, DCFH-DA probe is hydrolyzed into DCFH, which cannot freely cross the cell membrane, thus enriching the probe in the cells. The intracellular ROS oxidizes DCFH to DCF, and DCF can be excited to emit bright green fluorescence. The specific operation process is as follows: cells were cultured in 6-well plates, and when the cells recovered their morphology and reached about 60% confluence, they were intervened with drugs. After 24 hours, DCFH-DA probe was incubated with the cells for 30 minutes, washed with PBS once, and then collected cells are immediately detected on a flow cytometer. Due to the short lifespan and rapid change of ROS, to ensure the accuracy of the results, the total detection time should not exceed 1 hour from the time when the cells were digested and suspended.

Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Detection

The JC-1 probe was used to detect mitochondrial membrane potential depolarization levels. When the mitochondrial membrane potential is at a high level of polarization, the JC-1 accumulates in the mitochondrial matrix and emits red fluorescence. When the mitochondrial membrane potential is at a low level of polarization, the JC-1 probe is scattered in the cytoplasm and emits green fluorescence. By comparing the ratio of red/green fluorescence intensity, it can be used to measure mitochondrial depolarization levels. Cells were cultured in 6-well plates, and when the cells recovered their morphology and reached about 60% confluence, they were treated with different concentrations of JPJDR or control conditions. After 24 hours, the culture medium was removed and fresh medium containing the JC-1 probe was added, and the cells were incubated for 40 minutes. Then, the cells were gently washed 3 times and imaged immediately using a fluorescence microscope.

Transfection of LC3B-GFP-RFP

The virus sequence was designed and packaged by Genechem Company (Shanghai). We strictly followed the company’s instructions to infect the HT29 cell line. The cells were seeded in a 6-well plate at a confluence of 20%, and once they recovered their normal cell morphology, a serum-free medium containing virus particles (the virus titer was calculated based on the MOI value provided by the company) was added. After culturing the cells with the virus for approximately 16 hours, the cell was washed 3 times with PBS, and the medium was replaced with a complete medium containing 10% serum. The cells were cultured for about 3 days, followed by continuous selection with 8 μg/ml puromycin for 48 hours. When each cell emitted bright fluorescence under a fluorescence microscope, the cell line was considered successfully constructed.

The infected HT-29 cell line could express the LC3B-GFP-RFP reporter system stably. Since the green fluorescent protein (GFP) is not tolerant to acidic environments, it is destroyed by the acidic environment after the LC3B protein enters the lysosome, while the red fluorescent protein (RFP) can remain stable in acidic environments. Therefore, when autophagosomes are just produced, they emit both red and green light. However, when autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes, the green light is quenched, and the autophagosomes emit only red light. Therefore, the LC3B-GFP-RFP reporter system can be used to reveal whether autophagy is blocked in the late stage.

Animal Experiment

Thirty SPF-grade BALB/c nude female mice, 4-5 weeks old, were purchased from Changzhou Calvin Experimental Animal Co., Ltd (China). After 4 days of adjustable feeding, 200 μl PBS containing 1 × 107 cells was injected subcutaneously into the mice. About 16 days after injection, 18 mice with tumors that had reached a volume of 100 mm3 were selected. The mice were randomly divided into 3 groups. The mice in the JPJDR group were administered a dose of 22 g/kg (calculated based on the patient’s dosage, the dosage for mice is 12.3 times that for humans), the mice in the positive control group were injected intraperitoneally with 5-FU (50 mg/kg) every 3 days, and the model group mice were given an equal volume of water (290 μl). On the 14th day, the mice were anesthetized, and the tumors were separated and fixed. During the experiment, all animals were kept in an SPF-grade barrier environment with a temperature of 22°C, relative humidity of 60%, and a 12-hour light cycle. During the whole experiment, the estimated volume of the tumor was not allowed to exceed 2000 mm; otherwise, the mouse would be euthanized ahead of time.

Immunohistochemistry

Briefly, the paraffin-embedded tissue is cut into a thickness of 4 μm, adsorbed on a glass slide, and heated at 72°C for 2 hours. Subsequently, the tissue is gradually dewaxed in ethanol, and finally soaked in water for 5 minutes. The sections are heated by microwave for 3 minutes to repair the antigen, and 3% H2O2 is used to block endogenous peroxidase. The primary antibody is incubated overnight at 4°C, and the secondary antibody is incubated at room temperature for half an hour. The protein is quantitatively expressed by DAB. The data analysis was completed using the IHC Profiler plugin in the ImageJ software. The protein expression level was quantified by calculating the product of the average gray value and the percentage of positive area of positive cells in 1 image. The quantification method for PCNA is to estimate the number of positive cell nuclei. Finally, these products were normalized.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed at least 3 times. Statistical analysis was conducted by GraphPad Prism software. Differences between 3 (or more) groups were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Significance was designated as follows: *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001.

Results

JPJDR Inhibited CRC Activity and Proliferative Potential

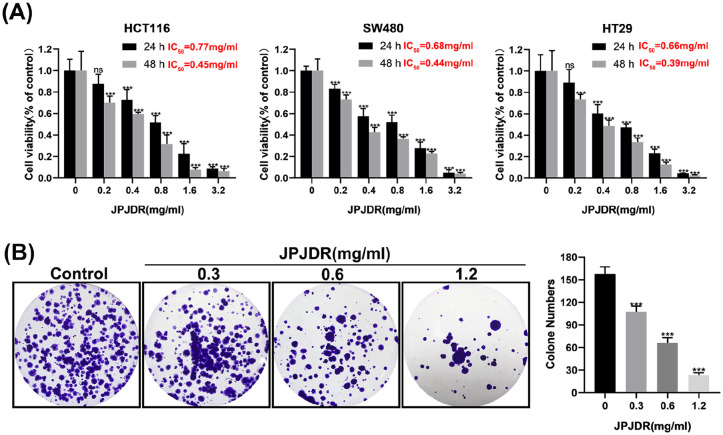

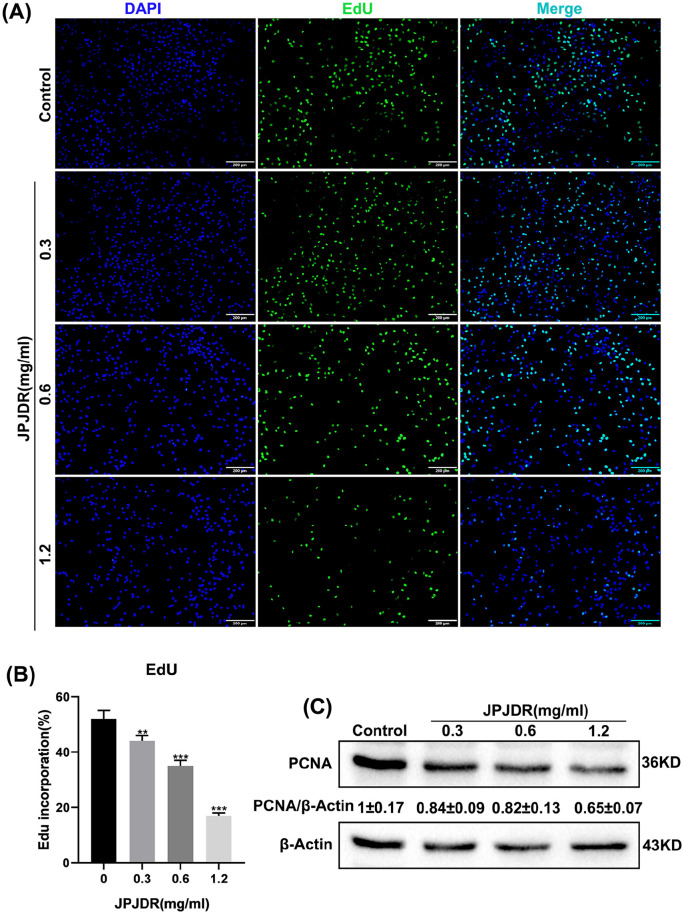

To preliminarily test the inhibitory effect of JPJDR on CRC, the CCK-8 assay was used to detect the activity of the cells. The activity of JPJDR-treated HCT116, SW480, and HT29 cells was reduced in a dose-dependent manner compared to the control group, with IC50s of 0.77, 0.68, and 0.66 mg/ml after 24 hours of treatment, and IC50 values of 0.45, 0.44, and 0.39 mg/ml after 48 hours of treatment (Figure 1A). Since HT29 cells were more sensitive to the drug treatment and had a good dose-inhibition curve fit, we chose HT29 for subsequent studies. JPJDR significantly reduced the clone formation ability of HT29 cells compared to the control group, indicating that their proliferative potential was down-regulated (Figure 1B). We next examined the proliferative capacity of HT29 using the EdU assay, which is a more sensitive way to detect proliferation. It showed that JPJDR significantly reduced the proliferative capacity of HT29 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2A and B). Meanwhile JPJDR substantially reduced the protein abundance of PCNA (Figure 2C), a proliferation marker for colorectal cancer. These results suggest that JPJDR has a favorable inhibitory effect on CRC.

Figure 1.

(A) Cell viability of HCT116, SW480, and HT29 after 24 or 48 hours of JPJDR treatment. (B) Representative images of HT-29 cell colony formation after 24 hours of JPJDR treatment.

Figure 2.

(A) EdU fluorescence image of HT-29 cells after 24 hours of JPJDR treatment. Scale bar 200 μm. (B) Compared with the control group, the differences were statistically significant. (C) After HT-29 cells were treated with JPJDR for 24 hours, the expression level of PCNA was detected by immunoblotting. GAPDH was used as an internal reference.

JPJDR Induced ROS Accumulation and Depolarized Mitochondrial Membrane Potential in CRC Cells

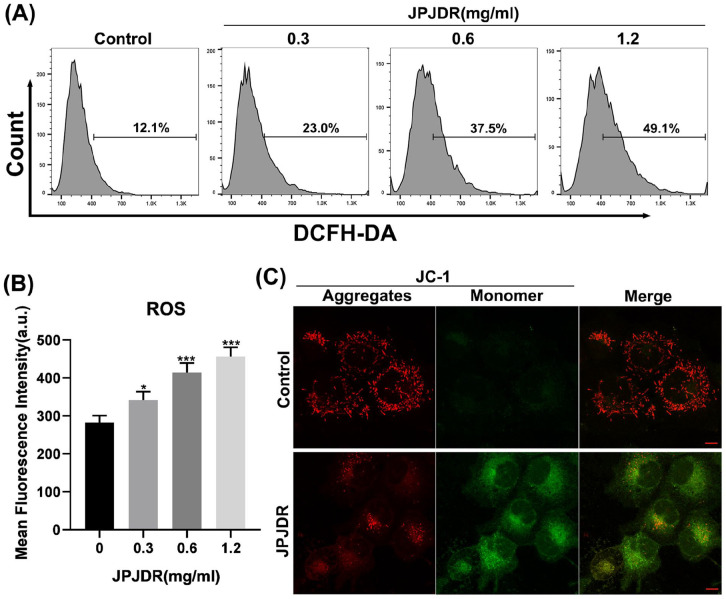

Subsequent studies found that JPJDR significantly increased reactive oxygen species levels in HT29 cells. Taking the control group as the standard, thresholds for positive cell populations were set. Different concentrations of JPJDR increased the ROS-positive cell population from 12.1% in the control group to 23.0%, 37.5%, and 49.1%, respectively (Figure 3A and B). Studies have shown that ROS can disrupt mitochondrial membrane potential and impair mitochondrial function.19,20 We subsequently examined the effect of JPJDR on mitochondrial membrane potential in HT29 cells using the JC-1 probe. In the control group, the JC-1 probe aggregated in the mitochondria and emitted red fluorescence, whereas, after JPJDR treatment, the JC-1 probe was difficult to aggregate in the mitochondria and dispersed in the cytoplasm or outside of the mitochondria in the form of monomers which emitted green fluorescence (Figure 3C), suggesting that the mitochondrial membrane potential had been significantly depolarized. These results indicate that JPJDR induces ROS accumulation and mitochondrial membrane potential depolarization in colorectal cancer cells.

Figure 3.

(A and B) After HT-29 cells were treated with JPJDR for 24 hours, the total reactive oxygen species level was detected by the DCFH-DA probe in combination with flow cytometry. (C) After HT29 cells were treated with JPJDR for 24 hours, mitochondrial membrane potential was detected by JC-1 probe, and the images were obtained by confocal microscopy. Scale bar 10 μm.

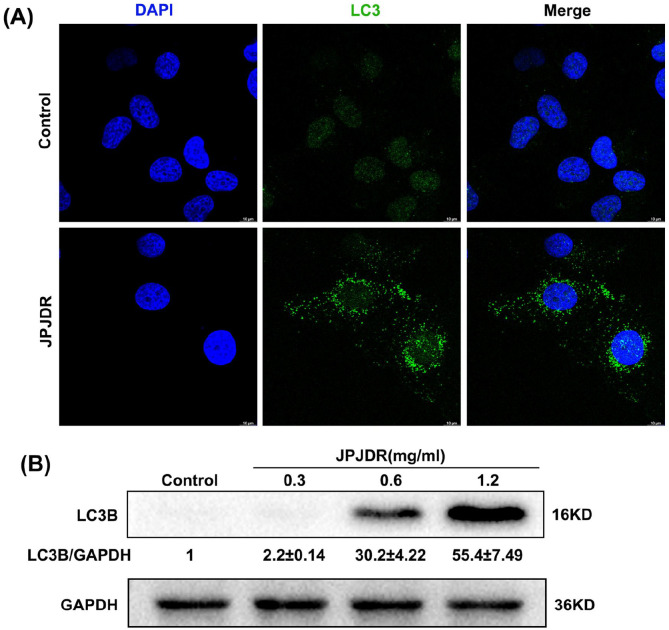

JPJDR Induces Incomplete Autophagy in CRC Cells

One critical study has shown that depolarization of mitochondrial membrane potential strongly induces autophagy activation, 21 while ROS has also been shown to be a potent autophagy activator. 22 Therefore, we next examined the expression and subcellular distribution of LC3B protein, a specific marker for autophagic vesicles. When in the control state, LC3B protein was dispersed in the cytoplasm and nucleus at very low abundance. The protein abundance of LC3B in HT29 cells treated with JPJDR increased dramatically and aggregated into puncta in the cytoplasm (Figure 4A and B), a hallmark of autophagic vesicle formation.

Figure 4.

(A) After HT-29 cells were treated with JPJDR for 24 hours, the LC3B protein was detected by immunofluorescence. Scale bar 10 μm. (B) After HT-29 cells were treated with JPJDR for 24 hours, the LC3B protein level was detected by western blot. GAPDH was used as an internal reference.

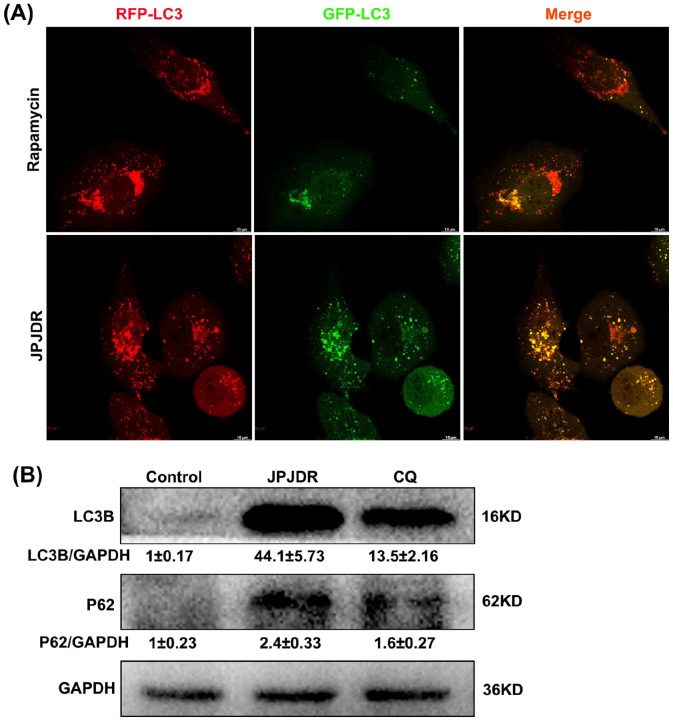

To investigate whether JPJDR increased autophagic flux, we reverse transcribed RFP-GFP-LC3B into HT29 cells. Rapamycin, a classical autophagy activator, induced an enhancement of autophagic flux through mTOR. Rapamycin-treated HT29 cells had a large number of red autophagic dots but only a minimal number of green dots, indicating that the majority of autophagosomes are formed and have completed fusion with lysosomes (the specific principle is described in the Materials and Methods section “Transfection of LC3B-GFP-RFP”). In contrast, red autophagic dots and green autophagic dots were co-expressed in JPJDR-treated HT-29 cells, indicating that autophagosomes failed to fuse with lysosomes (Figure 5A). These results suggest that JPJDR blocked the autophagic flow in HT29 cells. To further elucidate whether JPJDR simply blocked autophagic flow or activated incomplete autophagy, we examined the abundance of LC3B and p62 proteins. Co-upregulation of protein abundance of LC3B and P62 is a hallmark of autophagic flow blockade. 23 Chloroquine (CQ), a late autophagy blocker, 24 significantly increased the protein abundance of LC3B and P62, with LC3B protein abundance increasing by approximately 13-fold compared to the control group (Figure 5B). In contrast, the protein abundance of LC3B in HT-29 cells treated with JPJDR increased by approximately 44-fold. Therefore, JPJDR not only blocks autophagy flux at the terminal stage, but also promotes the formation of autophagosomes in the early stage of autophagy. These results suggest that JPJDR induced incomplete autophagy in CRC.

Figure 5.

(A) Live cell imaging of HT29 cells expressing the RFP-GFP-LC3B sequence, captured by a confocal microscope. The concentration of JPJDR and rapamycin are 1.2 mg/ml and 100 nM, respectively, and the treatment time is 24 hours. Scale bar 10 μm. (B) After HT-29 cells were treated with JPJDR or Chloroquine (CQ) for 24 hours, the LC3B and p62 protein level was detected by western blot. GAPDH was used as an internal reference. The concentration of JPJDR and CQ are 1.2 mg/ml and 20 μM, respectively.

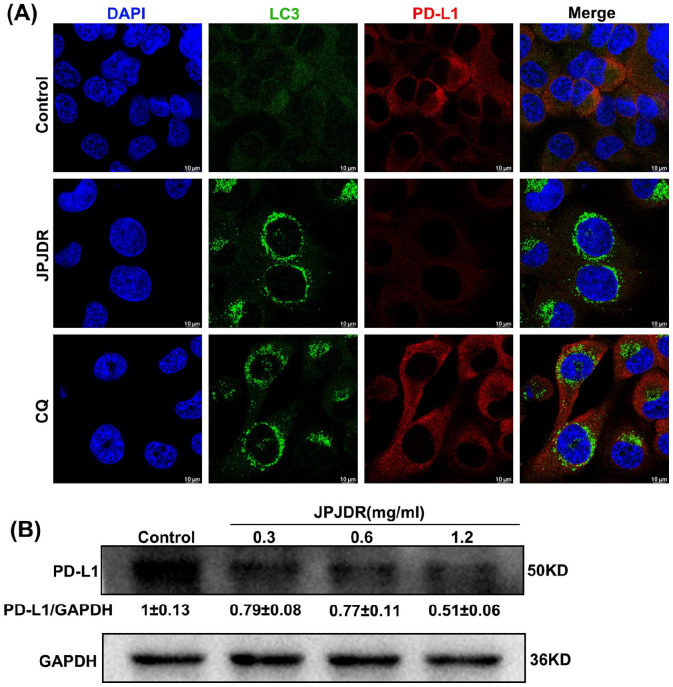

JPJDR Reduced the Expression of PD-L1 in CRC

The immunosuppression and immune escape of malignant tumors are among its 10 characteristics. Programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) is an important means for cancer cells to escape immunity and is considered a potential target. 25 One key study showed that blocking autophagy increases PD-L1 expression in gastric cancer cells, 16 so we focused on the effect of JPJDR on PD-L1 expression in CRC. After treatment with JPJDR, almost no PD-L1 expression was detected in HT29 cells, while more PD-L1 was detected in chloroquine (CQ)-treated HT29 cells (Figure 6A). To more accurately detect PD-L1 protein abundance, we performed the Western blot analysis. The results showed that JPJDR downregulated PD-L1 protein abundance in HT29 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6B). These results indicate that JPJDR can downregulate PD-L1 expression in CRC without upregulating PD-L1 due to autophagy.

Figure 6.

(A) Immunofluorescence images of LC3B (green) and PD-L1 (red). The concentration of JPJDR and CQ are 1.2 mg/ml and 20 μM, respectively. Scale bar 10 μm. (B) After HT-29 cells were treated with JPJDR for 24 hours, the PD-L1 protein level was detected by western blot. GAPDH was used as an internal reference.

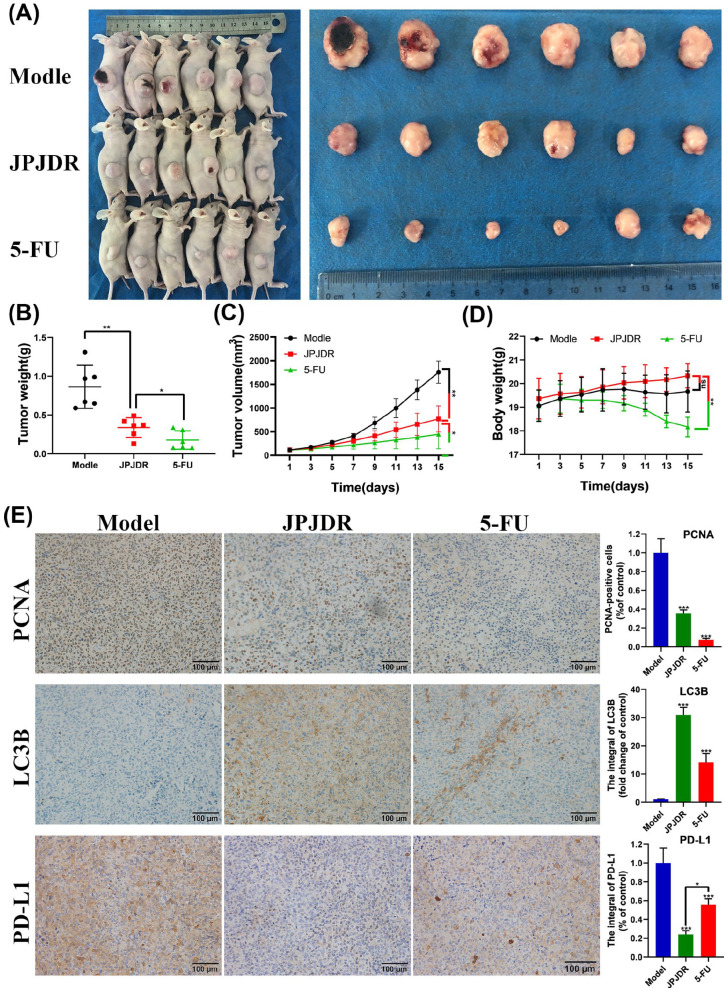

JPJDR Inhibited Colon Cancer Growth In Vivo

Next, we constructed a xenograft tumor model of HT-29 cells to investigate whether JPJDR produces these effects in vivo (Figure 7A-D). Compared with the control group, in mice treated with JPJDR (22 g/kg) for 14 days, the tumor volume was reduced from 2140.3 ± 735.6 to 867.2 ± 332.6 mm3, and the tumor weight was reduced from 0.86 ± 0.28 to 0.34 ± 0.13 g, both of which were significant. The tumor-suppressing efficacy of JPJDR differed significantly from that of the positive drug 5-FU (50 mg/kg), with the volume and weight of the tumor after 14 days of 5-FU treatment being 446.3 ± 0.28 and 446.3 ± 0.13 g, respectively. However, the weight of mice after 14 days of 5-FU treatment (18.2 ± 0.4 g) was significantly lower than that of the JPJDR group (20.3 ± 0.5 g). These results indicate that JPJDR can significantly inhibit the growth of colon cancer in mice. The therapeutic effect of 22 g/kg dose of JPJDR was significantly lower than that of 50 mg/kg dose of 5-FU, but compared with the control group, the 22 g/kg dose of JPJDR had no effect on the body weight of mice.

Figure 7.

(A) Images of the whole mouse and isolated tumor. (B-D) Statistical analysis of tumor volume, weight, and mouse weight. (E) Immunohistochemical images of PCNA, LC3B, and PD-L1 proteins in tumor tissue. Scale bar 100 μm. Magnification: 100×.

Mouse tumors were isolated and subjected to immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 7E). Compared with the control group, the positivity rate of tumor proliferation marker PCNA was significantly lower in the JPJDR group. At the same time, JPJDR increased the accumulation of LC3B in tumor tissues. Consistent with the results of cell experiments, JPJDR significantly downregulated the expression of PD-L1 in tumor tissues. The expression of PD-L1 in tumor tissues after 5-FU treatment was also reduced, but the effect of JPJDR was significantly better than 5-FU. These results preliminarily verified the consistency of JPJDR in the treatment of colon cancer in vitro and in vivo.

Discussions

Although in the past decades, the popularization of risk factors (such as smoking, increased use of aspirin, consumption of red meat and processed meat, obesity, and diabetes) and the application of colonoscopic polypectomy have reduced the incidence rate and mortality, nearly 50% of patients after surgical resection have the risk of recurrence and metastasis leading to death within 5 years after diagnosis. 3 Due to the frequent occurrence of drug resistance events and patients’ intolerance to drugs, many colorectal cancer patients eventually face the dilemma of having no drugs available. 12 Therefore, it is urgent to find new drugs and strategies for the treatment of colorectal cancer.

Due to the high level of sugar metabolism, even with the presence of the Warburg effect, the level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) remains high in tumor cells. 26 Previous research has shown that ROS can promote the occurrence and development of cancer, such as maintaining the activity of PI3K signaling. 27 Until 2011, one key study showed that ROS can relieve the progress of some cancers and found that the redox state in cells is an important factor determining tumor formation. 28 Now the mainstream view is that continuously increasing the generation of ROS in tumor cells is a preferred strategy to eliminate tumor cells,29,30 because the change of metabolic characteristics maintains a very dangerous high level of ROS in tumor cells. Mitochondria are the main site of ROS production, especially complex I. The increase of ROS can lead to the opening of mitochondrial membrane permeability transport pores, which directly leads to the reduction of mitochondrial membrane potential and induces apoptosis. 31 Our findings are similar to these results. JPJDR significantly increased the ROS level in CRC cells and depolarized the mitochondrial membrane potential (Figure 3). Long-term clinical applications indicate that JPJDR is an effective compound preparation with extremely low toxicity. Meanwhile, in a pre-experiment on animals, a dose of 22.5 g/kg of JPJDR had no significant effect on the hepatic index and spleen index of nude mice (Table 1). Targeting mitochondrial ROS production is a strategy to eliminate tumor cells preferentially, 12 which might explain the effectiveness and low toxicity of JPJDR in cancer treatment. Animal experiments also show that JPJDR did not significantly reduce the body weight of mice, unlike the traditional chemotherapy drug 5-FU (Figure 7). In clinical treatment, patients receiving 5-FU chemotherapy often suffer from gastrointestinal tract injury, while the traditional application of JPJDR includes promoting appetite and digestive system function. Although JPJDR is not as effective as 5-FU in treating tumors in mice, almost all patients in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) hospitals in China will choose traditional Chinese medicine treatment. 32 On the one hand, patients who choose to go to TCM hospitals are more likely to prefer traditional Chinese medicine treatment. On the other hand, it may be due to the good compliance of patients brought by the low toxicity and side effects of JPJDR. We will subsequently conduct a detailed evaluation of the impact of JPJDR on patients’ symptom scores and survival duration.

Table 1.

JPJDR Effects on the Organs Indexes of Mice Bearing AGS Cells.

| Group | Dosages | Sample size, n | Hepatic index, mg/g | Spleen index, mg/g |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | – | 8 | 68.4 ± 4.3 | 8.5 ± 1.9 |

| JPJDR | 22.5 g/kg | 8 | 67.5 ± 6.7 | 9.6 ± 1.2 |

| 45 g/kg | 8 | 67.3 ± 9.2 | 11.9 ± 1.7** | |

| 5-Fu | 50 mg/kg | 8 | 71.2 ± 11.7 | 12.4 ± 2.3** |

Compared with the model group: *P < .05; **P < .01.

Autophagy is a highly conserved cytoplasmic process that allows cells to “eat” a portion of themselves in order to counteract external environmental stress. 24 There are many inducers of autophagy, including energy deficiency, growth factor deficiency, accumulation of reactive oxygen species, microbial infection, organelle damage, and misfolded proteins. 33 Typically, the role of autophagy in cancer cells can be bivalent: cancer cells can relieve energy stress and abnormal proteins and organelles caused by drugs through autophagy, which is beneficial to their survival and drug resistance. As shown in Figure 7E, there is an accumulation of LC3B protein in tumor tissues after 5-FU treatment, which is generally considered as an adaptive response by tumors to overcome chemotherapy drugs by activating autophagy to remove damaged organelles. However, if the autophagy process is interrupted, autophagosomes engulf various cell contents and accumulate in the cytoplasm without being digested, which can exacerbate damage and ultimately cause cell death, known as autophagic death. 34 Additionally, clinical applications have demonstrated that blocking autophagy is a good strategy for treating cancer. 35 Currently, there are a large number of compounds that have been shown to regulate autophagy, but their targets are relatively broad, which limits their clinical applications. This study demonstrated that JPJDR is an incomplete autophagy activator, leading to significant accumulation of LC3 protein in the cytoplasm and causing growth arrest in CRC cells (Figure 2). Compared to the autophagy inhibitor chloroquine, JPJDR resulted in more accumulation of LC3BⅡ in the cytoplasm. According to the results of Western blotting, JPJDR increased the autophagy level in CRC cells by approximately 3 times and prevented them from being digested at the end of the autophagy flux (Figure 5). These results provide more evidence and potential applications for the clinical use of JPJDR.

Currently, antibodies or inhibitors against PD-1/PD-L1 are being tested in more than 1000 clinical trials, and some of them have been approved for cancer treatment. 25 Although one large clinical study in 2012 showed that PD-1 antibody treatment had no significant effect on colon cancer patients, 18 a large number of studies have shown that PD-L1 blocking or ablation has good application potential in colorectal cancer. 36 At first, we were worried that autophagy blockage would increase the expression of PD-L1 in colon cancer cells, 16 which was a potential risk. However, our study showed that JPJDR, as a mixed preparation, not only did not increase the expression of PD-L1 due to autophagy blockage, but also reduced the expression of PD-L1 in HT-29 cells. Since the anti-PD-1 therapy failed in clinical trials of colorectal cancer, and the model we used was a non-immune mouse, we cannot determine the therapeutic effect of JPJDR downregulating PD-L1 expression in tumor cells in vivo, which is what we will study next.

Conclusion

In summary, we confirmed the efficacy of Jianpi Jiedu Recipe in treating colon cancer in vitro and in vivo, and revealed the mitochondrial dysfunction and incomplete autophagy induced by it. At the same time, this study identified a rare formula that blocks autophagy in colon cancer while reducing its PD-L1 expression. These findings will provide more evidence and guidance for the clinical application of JDJDR.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-ict-10.1177_15347354241268064 for Jianpi Jiedu Recipe Inhibits Proliferation through Reactive Oxygen Species-Induced Incomplete Autophagy and Reduces PD-L1 Expression in Colon Cancer by Lingling Cheng, Liangfeng Xu, Hua Yuan, Qihao Zhao, Wei Yue, Shuang Ma, Xiaojing Wu, Dandan Gu, Yurong Sun, Haifeng Shi and Jianlin Xu in Integrative Cancer Therapies

Acknowledgments

Thank you for the financial support from “2023 Medical Scientific Research Project of Yancheng Health Commission (YK2023074)” and the equipment support from Yancheng Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Lingling Cheng and Jianlin Xu: Conception and design. Lingling Cheng, Liangfeng Xu, HuaYuan, Qihao Zhao, and Wei Yue: Acquisition of data (provided animals, acquired and provided facilities). Shuang Ma, Xiaojing Wu, Dandan Gu, Yurong Sun, and Haifeng Shi: Analysis and interpretation of data. Lingling Cheng: Writing and review the manuscript. Jianlin Xu: Study supervision. All data were generated in-house, and no paper mill was used. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Thank you for the financial support from “2023 Medical Scientific Research Project of Yancheng Health Commission (YK2023074)” and the equipment support from Yancheng Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital.

Ethical Approval of Animal Studies: Approval for the conduct of animal studies is shown in Supplementary File 1.

ORCID iD: Lingling Cheng  https://orcid.org/0009-0003-8757-2174

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-8757-2174

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:17-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Biller LH, Schrag D. Diagnosis and treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: a review. JAMA. 2021;325:669-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bardia A, Loprinzi C, Grothey A, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for resected stage ii and iii colon cancer: comparison of two widely used prognostic calculators. Semin Oncol. 2010;37:39-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhao H, He M, Zhang M, et al. Colorectal cancer, gut microbiota and traditional chinese medicine: a systematic review. Am J Chin Med. 2021;49:805-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cragg GM, Newman DJ. Natural products: a continuing source of novel drug leads. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830:3670-3695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tian YM, Zhou X, Zhao C, Chen HG, Gong XJ. [Research progress on mechanism of active ingredients in traditional chinese medicine for gastric cancer]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2020;45:3584-3593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jin P, Ji X, Kang W, et al. Artificial intelligence in gastric cancer: a systematic review. J Cancer Res Clin. 2020;146:2339-2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li R, Zhou J, Wu X, et al. Jianpi jiedu recipe inhibits colorectal cancer liver metastasis via regulating itgbl1-rich extracellular vesicles mediated activation of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Phytomedicine. 2022;100:154082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Peng W, Zhang S, Zhang Z, et al. Jianpi jiedu decoction, a traditional chinese medicine formula, inhibits tumorigenesis, metastasis, and angiogenesis through the mtor/hif-1α/vegf pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;224:140-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cheung EC, Vousden KH. The role of ros in tumour development and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22:280-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhou J, Zhang L, Wang M, et al. CPX targeting DJ-1 triggers ROS-induced cell death and protective autophagy in colorectal cancer. Theranostics. 2019;9:5577-5594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Onorati AV, Dyczynski M, Ojha R, Amaravadi RK. Targeting autophagy in cancer. Cancer. 2018;124:3307-3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ascenzi F, De Vitis C, Maugeri-Saccà M, Napoli C, Ciliberto G, Mancini R. Scd1, autophagy and cancer: implications for therapy. J Exp Clin Canc Res. 2021;40:265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fares J, Petrosyan E, Kanojia D, et al. Metixene is an incomplete autophagy inducer in preclinical models of metastatic cancer and brain metastases. J Clin Invest. 2023;133:e161142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang X, Wu W, Gao J, et al. Autophagy inhibition enhances PD-L1 expression in gastric cancer. J Exp Clin Canc Res. 2019;38:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yi M, Zheng X, Niu M, Zhu S, Ge H, Wu K. Combination strategies with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: current advances and future directions. Mol Cancer. 2022;21:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. New Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443-2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guo Y, Guan T, Shafiq K, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in aging. Aging Res Rev. 2023;88:101955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhao M, Wang Y, Li L, et al. Mitochondrial ROS promote mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammation in ischemic acute kidney injury by disrupting tfam-mediated mtDNA maintenance. Theranostics. 2021;11:1845-1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Narendra DP, Jin SM, Tanaka A, et al. Pink1 is selectively stabilized on impaired mitochondria to activate parkin. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xing Y, Wei X, Liu Y, et al. Autophagy inhibition mediated by MCOLN1/TRPML1 suppresses cancer metastasis via regulating a ROS-driven tp53/p53 pathway. Autophagy. 2022;18:1932-1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Levine B. Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell. 2010;140:313-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ferreira P, Sousa R, Ferreira J, Militão G, Bezerra DP. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in antitumor therapies based on autophagy-related mechanisms. Pharmacol Res. 2021;168:105582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shen X, Zhao B. Efficacy of PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors and PD-L1 expression status in cancer: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;362:k3529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang J, Simpson CM, Berner J, et al. Systematic identification of anticancer drug targets reveals a nucleus-to-mitochondria ROS-sensing pathway. Cell. 2023;186:2361-2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moloney JN, Cotter TG. ROS signalling in the biology of cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2018;80:50-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. DeNicola GM, Karreth FA, Humpton TJ, et al. Oncogene-induced Nrf2 transcription promotes ROS detoxification and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2011;475:106-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Trachootham D, Alexandre J, Huang P. Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: a radical therapeutic approach? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:579-591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gorrini C, Harris IS, Mak TW. Modulation of oxidative stress as an anticancer strategy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:931-947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lv C, Huang Y, Wang Q, et al. Ainsliadimer A induces ROS-mediated apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells via directly targeting peroxiredoxin 1 and 2. Cell Chem Biol. 2023;30:295-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang Y, Jiang L, Ouyang J, Du X, Jiang L. Efficacy and safety of traditional Chinese medicine injections combined with Folfox4 regimen for gastric cancer: a protocol for systematic review and network meta-analysis. Medicine. 2021;100:e27525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Debnath J, Gammoh N, Ryan KM. Autophagy and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023;24:560-575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang Q, Cao S, Qiu F, Kang N. Incomplete autophagy: trouble is a friend. Med Res Rev. 2022;42:1545-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Levy J, Towers CG, Thorburn A. Targeting autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:528-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Payandeh Z, Khalili S, Somi MH, et al. PD-1/PD-L1-dependent immune response in colorectal cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235:5461-5475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-ict-10.1177_15347354241268064 for Jianpi Jiedu Recipe Inhibits Proliferation through Reactive Oxygen Species-Induced Incomplete Autophagy and Reduces PD-L1 Expression in Colon Cancer by Lingling Cheng, Liangfeng Xu, Hua Yuan, Qihao Zhao, Wei Yue, Shuang Ma, Xiaojing Wu, Dandan Gu, Yurong Sun, Haifeng Shi and Jianlin Xu in Integrative Cancer Therapies