Abstract

Background

Therapeutic resistance is a main obstacle to achieve long-term benefits from immune checkpoint inhibitors. The underlying mechanism of neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 resistance remains unclear.

Methods

Multi-omics analysis, including mass cytometry, single-cell RNA-seq, bulk RNA-seq, and polychromatic flow cytometry, was conducted using the resected tumor samples in a cohort of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients received neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy. Tumor and paired lung samples acquired from treatment-naïve patients were used as a control. In vitro experiments were conducted using primary cells isolated from fresh tissues and lung cancer cell lines. A Lewis-bearing mouse model was used in the in vivo experiment.

Results

The quantity, differentiation status, and clonal expansion of tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells (CD8+ TRMs) are positively correlated with therapeutic efficacy of neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy in human NSCLC. In contrast, the quantity of immature CD1c+ classical type 2 dendritic cells (imcDC2) and galectin-9+ cancer cells is negatively correlated with therapeutic efficacy. An epithelium/imDC2 suppressive axis that restrains the antitumor response of CD8+ TRMs via galectin-9/TIM-3 was uncovered. The expression level of CD8+ TRMs and galectin-9+ cancer cell-related genes predict the clinical outcome of anti-PD-1 neoadjuvant therapy in human NSCLC patients. Finally, blockade of TIM-3 and PD-1 could improve the survival of tumor-bearing mouse by promoting the antigen presentation of imcDC2 and CD8+ TRMs-mediated tumor-killing.

Conclusion

Galectin-9 expressing tumor cells sustained the primary resistance of neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy in NSCLC through galectin-9/TIM-3-mediated suppression of imcDC2 and CD8+ TRMs. Supplement of anti-TIM-3 could break the epithelium/imcDC2/CD8+ TRMs suppressive loop to overcome anti-PD-1 resistance.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, CD8-Positive T-Lymphocytes, Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Tumor-related intrinsic factors, such as driver gene mutation, in therapeutic resistance of anti-PD-1 in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have mostly been elucidated. However, the factors in tumor microenvironment (TME) which participate in neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 resistance in resectable NSCLC remain unclear.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

An epithelium/immature CD1c+ classical type 2 dendritic cells (imDC2) suppressive axis that restrains the antitumor response of CD8+ TRMs via galectin-9/TIM-3 in TME of NSCLC is uncovered. Combination therapy of anti-TIM-3 and anti-PD-1 overcomes the suppression of imcDC2 and CD8+ TRMs and improve the survival of tumor-bearing mouse.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Monotherapy of anti-PD-1 is not sufficiently effective in the neoadjuvant therapy of NSCLC. Our study reveals the mechanism of neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 resistance in NSCLC and suggests that combination therapy of anti-TIM-3 and anti-PD-1 is a promising strategy to overcome treatment resistance.

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy provides durable clinical responses and improves overall patient survival in multiple cancers.1 However, only a fraction of patients with specific tumor types respond to ICIs.2 In addition, emerging resistance to these agents restricts the number of patients who are able to achieve durable responses, and immune-related adverse events further complicate treatment.3 Thus, a better understanding of treatment resistance and the development of novel approaches to overcome such resistance is drastically needed.4

ICI resistance can be classified into primary and acquired resistances, depending on whether an initial response is acquired.3 Previous studies have shown that tumorous and systemic changes in the immune system following therapy form the basis for both efficacy and resistance of ICIs.5 For instance, an increase in distinct immune cell subsets, activation of specific transcriptional networks, and upregulation of immune checkpoint genes are more pronounced in patients with response during anti-PD-1 therapy.6 In addition, a correlation between T-cell clonal expansion and neoantigen loss is also observed.6 CD8+ T cells express immune checkpoint molecules, such as PD-1 and CTLA-4, which are the key target of ICIs.7,10 Previous studies have shown that the expansion of tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells, both in the tumor microenvironment (TME) and peripheral blood, is associated with the response of ICIs.11,13 These findings highlight the fundamental role that tumor-reactive T cells play in the response and resistance of ICI therapy.

Tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells (CD8+ TRMs) are an emerging subset of CD8+ T cells with a crucial role in immune surveillance of cancers.14,16 Accumulating evidence demonstrates that CD8+ TRMs are positively correlated with the prognosis of multiple human cancers.17,22 In addition, single-cell sequencing studies found that tumor-infiltrating CD8+ TRMs exhibited an increased expression level of immune checkpoint molecules and correlated with the efficacy of ICI therapy in multiple human cancers.18 23 24 Increased numbers of CD8+ TRMs were associated with improved survival in immunotherapy-naive melanoma patients.25 Single-cell analysis of immune cells from melanoma patients treated with ICI therapy revealed that a stem-like CD8+ T cell subset with CD8+ TRMs feature was associated with a positive outcome of patients.10 A recent study in human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) showed that the inactivation of tumor antigen-specific CD8+ TRMs was correlated with the primary resistance of neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy.26 Together, these data suggest that CD8+ TRMs play a critical role in the resistance of ICI therapy. Despite these studies, the regulatory mechanism of CD8+ TRM response in the TME underlying ICI therapy remains elusive.

Here, we conducted a comprehensive study using mass cytometry, single-cell sequencing, TCR repertoire sequencing, histological analysis, confocal immunofluorescence analysis, and in vitro coculture to decode the dynamic changes of the TME of human NSCLC on neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy. Our results show that the expansion of terminally differentiated CD8+ TRM effector cells is closely related to the efficacy of neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy. We also identified a precursor of CD8+ TRMs that can clonally expand into terminal effector cells on anti-PD-1 treatment. Furthermore, we observed the accumulation of immature CD1c+ classical type 2 dendritic cell (imcDC2) was observed in the tumors with primary resistance of neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy. Mechanistically, we demonstrated that a cancer cell-derived galectin-9/TIM-3/imcDC2 loop, which inhibits the activation of CD8+ TRMs in the TME, is essential for primary resistance of anti-PD-1 therapy in human NSCLC. Blockade of TIM-3 on imcDC2 can break the epithelium/imcDC2 suppressive loop to improve anti-PD-1 therapy. Collectively, our study provides a mechanistic insight into understanding ICI resistance in human NSCLC.

Results

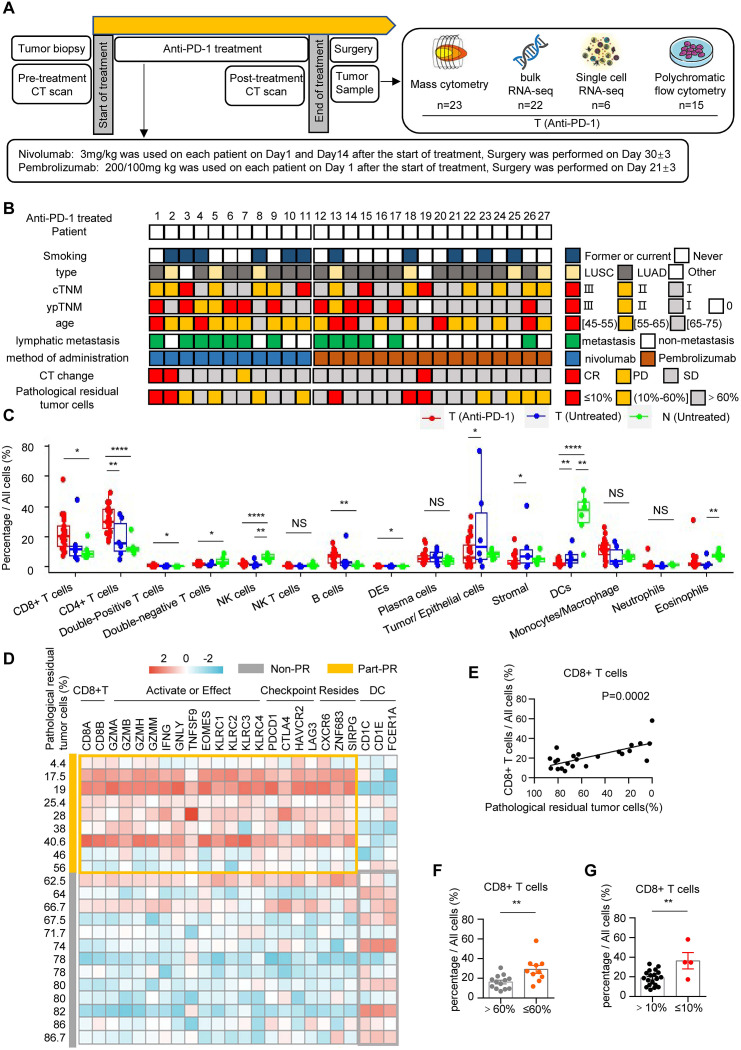

Neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy remodels the TME of human NSCLC

To explore the changes of TME in human NSCLC during neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy, a cohort of 30 NSCLC patients were recruited and 27 patients (90%) had completed all cycles of planned treatment (online supplemental figure 1A). For nivolumab, 3 mg/kg was used for each patient on day 1 and day 14 and the surgery was performed on day 30±3 (figure 1A). For pembrolizumab, 200 mg or 100 mg was used on day 1 and the surgery was performed on day 21±3 (figure 1A). The details of cohort information and study design are presented in figure 1A,B, online supplemental figure 1A, onlinesupplemental tables 13 (approved by The National Institutes of Health (NIH)). In this cohort, 18.5% of patients (5/27) reached MPR (major pathological response, pathological residual tumor cells ≤10%), and 11.1% (3/27) patients reached radiographic PR (partial response, the sum of maximum diameter of tumor target lesions decreased by ≥30%) (figure 1B and online supplemental figure 1B,C). The tumor and adjacent tissues were collected and analyzed by mass flow cytometry, bulk RNA-seq, single-cell RNA-seq, and multicolor flow cytometric analysis (figure 1B). The raw mass spectrometry flow cytometry data, bulk RNA-seq data have been deposited in the OMIX. The raw scRNA-seq data reported has been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive in National Genomics Data Center. Using a panel of 42 markers, 13 immune cell clusters were identified by the CyTOF analysis (online supplemental table 4, online supplemental table 5 and online supplemental figure 2A,B). As expected, we found the immune landscape of tumors in anti-PD-1 treatment group was obviously different from the tumor and paired normal lung tissue of untreated patients (online supplemental figure 2C). Quantitative analysis showed the proportions of CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, double-positive (CD4+ CD8+) T cells, and B cells in the tumor of anti-PD-1 group were significantly higher than normal lung tissues, but the proportions of double-negative (CD4− CD8−) T cells, NK cells, and dendritic cells (DCs) were higher in normal lung tissues (figure 1C and online supplemental figure 2D). When compared with untreated tumors, the proportion of CD4+ T cells in the tumor of anti-PD-1 group was significantly increased, whereas the proportions of tumor cells, stromal cells, and DCs decreased (figure 1C). Bulk RNA-seq analysis revealed that the gene expression patterns of anti-PD-1 treated tumors were different from untreated tumors and normal tissues (online supplemental figure 3A). Analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) showed that higher levels of CD8+ effector T cell-related genes (CD3D, CD8B, GZMB, GNLY, and PDCD1) were noted in anti-PD-1 group (online supplemental figure 3B). Using the median of pathological residual rate of cancer cells (60%) as the definition of part-pathological response (Part-PR, pathological residual rate between 60% and 0%), principal component analysis (PCA) showed the gene expression patterns of NSCLC in the Part-PR group were different from untreated tumors and normal lung tissues (online supplemental figure 3C). In addition, we found that the expression levels of CD8+ TRMs-related genes (CD8A, CD8B, CXCR6, and ZNF683) were significantly higher in Part-PR group than Non-PR group and untreated group (online supplemental figure 3D,E). Further analysis showed that the expression levels of genes related to terminal effector of CD8+ TRMs in Part-PR group were significantly higher than Non-PR group, including CD8+ T cell genes (CD8A and CD8B), tissue residency genes (CXCR6, ZNF683), activation or effector genes (KLRC family, GZM family, IFNG, GNLY, TNFSF9, and EOMES) and immune checkpoint genes (PDCD1, CTLA4, HAVCR2, and LAG3) (figure 1D). Interestingly, the expression levels of DCs-related genes (CD1C, CD1E, and FCGBP) were significantly higher in Non-PR group (figure 1D). Gene set enrichment analysis revealed that the signaling pathways involved in immune system process, T cell activation, and cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction were significantly enriched in the tumors of Part-PR group (online supplemental figure 3F). Consistently, single-cell RNA-seq showed that CD8+ T cells enriched in Part-PR group (online supplemental figure 4A–J). Further correlation analysis showed that the quantity of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells was positively correlated with PR of neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy (figure 1E). Consistently, the proportions of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells were significantly higher in the Part-PR group than in the Non-PR group (figure 1F). A consistent result was obtained in the MPR group (figure 1G). Collectively, these results demonstrate that neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 immunotherapy modulates NSCLC TME immune landscape such as alterations of the quantity, constitution, and gene signatures of tumor-infiltrating immune cells, especially CD8+ T cells.

Figure 1. Tumor microenvironment remodeling after anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. (A) Trial schema and the timing of the biopsy and surgery sample collections. (B) Clinical information and pathological outcomes of each anti-PD-1 treated patients. (C) The box plot shows the percentage of each cell type in all cells. Data are shown as mean±SEM; T (Anti-PD-1) (red, tumor after anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, n=23), T (Untreated) (blue, untreated tumor tissues, n=6), N (Untreated) (green, untreated adjacent normal tissues, n=6); NS p≥0.05; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ****p<0.0001. (D) Correlation analysis showing the correlation between each cell type and the correlation between each cell type and pathological residual rate in tumor after anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. n=23, *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001. (E) Heatmaps showing relative abundance of representative differentially expressed genes between Part-PR (≤60%, n=9) and Non-PR (>60%, n=13), standardized by Z score. (F) Correlation analysis shows a correlation between the percentage of CD8+ T cells and the rate of pathological tumor residual. (G) The bar graph shows the percentage of CD8+ T cells in all cells ≤60% (orange, pathological residual tumor cells ≤60%, n=10), >60% (gray, pathological residual tumor cells >60%, n=13); **p<0.01. (H) The bar graph shows the percentages of CD8+ T cells in all cells ≤10% (red, pathological residual tumor cells ≤10%, n=4), >10% (black, pathological residual tumor cells >10%, n=19); **p<0.01.

CD8+ TRMs correlate with a favorable neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 treatment response

Growing evidence suggests that tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells (CD8+ TRMs) play a crucial role in cancer immunosurveillance and correlate with the survival of multiple advanced cancers.16 27 28 However, the correlation between CD8+ TRMs and neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy of human NSCLC remains largely unclear. Using CD69 and CD103 as the markers of CD8+ TRMs, we classified tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells into three major subsets, CD69+ CD103+ CD8+ TRMs, CD69+ CD103− CD8+ T cells and CD69− CD103− CD8+ T cells (online supplemental figure 5A–C). We found that the composition of different CD8+ T cell subsets was different among the samples of anti-PD-1-treated tumors, untreated tumors, and untreated normal lung tissues (figure 2A and online supplemental figure 5D). Further quantitative analyses showed that CD8+ TRM is the only subset of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells which increased in anti-PD-1-treated and untreated tumors (figure 2B). In contrast, CD69− CD103− CD8+ T cells which are circulatory subset of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells was decreased in anti-PD-1-treated and untreated tumors (figure 2B). More importantly, we found that the percentage and absolute number of CD8+ TRMs in the anti-PD-1-treated tumors of MPR (pathological residual rate between 10% and 0%) showed an upward trend compared with the no pathological response (NPR) group (figure 2C,D). Correlation analysis further demonstrated a positive correlation between the percentage and absolute number of CD8+ TRMs with the efficacy of neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy (figure 2E). In contrast, both the percentage and absolute number of CD69− CD103− CD8+ T cells were negatively correlated with the efficacy of neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy (figure 2F). Single-cell RNA-seq further demonstrated enrichment of CD8+ TRMs in the TME of the Part-PR group, while CD69+ CD103− CD8+ T cells showed a decreasing trend (online supplemental figure 5E–H). Correlation analysis revealed that the quantity of CD8+ TRMs was positively correlated with the efficacy of neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy, whereas CD69+ CD103− CD8+ T cells did not show a significant correlation (online supplemental figure 5I,J). Flow cytometric analysis of paired tumor samples before and after treatment showed that tumor-infiltrating CD8+ TRMs increased significantly after anti-PD-1 therapy (figure 2G,H). In contrast, the percentage of CD69− CD103− CD8+ T cells was significantly decreased in TME after anti-PD-1 therapy (figure 2H). In addition, we found that the expression levels of activated-markers, such as CD38, CD39, and HLA-DR, were increased on anti-PD-1-treated tumor-infiltrating CD8+ TRMs, and further elevated by anti-PD-1 therapy (figure 2I). Moreover, tumor-infiltrating CD8+ TRMs in the MPR group expressed significantly higher levels of CD38 and CD39 than the NPR group (figure 2I). Consistently, ENTPD1 and GZMB were highly expressed in the Part-PR groups, while IL7R was highly expressed in the Non-PR groups (figure 2J). Our results demonstrate that CD8+ TRM is the key subset of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells which specifically correlates with a favorable anti-PD-1 response in NSCLC.

Figure 2. CD8+ TRMs are positively correlated with the efficacy of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. (A) t-SNE plots embedding of CD8+ T cells grouped by organizational source from NSCLC tumor after anti-PD-1 immunotherapy (T (Anti-PD-1), n=23), untreated tumor tissues (T (Untreated), n=6) and untreated paired normal tissues (N (Untreated), n=6) by CyTOF using a PhenoGraph clustering scheme, with each cell color coded to indicate the associated cell types. (B) The box plot shows the percentages (left) and the absolute number (right) of different subgroups in CD8+ T cells. T (Anti-PD-1) (red, n=23); T (Untreated) (blue, n=6); N (Untreated) (green, n=6). NS p≥0.05; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001. (C) The same t-SNE as (A), grouped by different therapeutic effect. MPR (pathological residual tumor cells ≤10%, n=4), NPR (pathological residual tumor cells >10%, n=19). (D) The box plot shows the percentages (left) and the absolute number (right) of different subgroups in CD8+ T cells. MPR (orange, pathological residual tumor cells ≤10%, n=4); NPR (gray, pathological residual tumor cells >10%, n=19). NS p≥0.05; ***p<0.001. (E) Correlation analysis shows the correlation between the percentages (left) or the absolute number (right) of TRMs (CD69+ CD103+ T cells) and pathological residual rate in tumor after anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. n=23. (F) Correlation analysis shows the correlation between the percentages (left) or the absolute number (right) of CD69− CD103− CD8+ T cells and pathological residual rate in tumor after anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. n=23. (G) Representative flow cytometric analysis of the expression of CD69 and CD103 in CD8+ T cells pre- or post-anti-PD-1 treatment in NSCLC. Numbers in plots indicate the percentages of cells in respective gates. (H) The bar graph shows the percentages of TRMs, CD69+ CD103− T cells and CD69− CD103− in CD8+ T cells pre- or post-anti-PD-1 treatment in NSCLC. Pre (blue, n=15); post (red, n=15). NS p≥0.05; *p<0.05. Pretreatment: tumor samples obtained at the time of lung puncture, post-treatment: tumor samples obtained at the time of surgery after completion of the 1-month course of anti-PD-1 treatment. (I) Heatmap of mean log-normalized expression of different proteins in CD8+ TRMs. T (Anti-PD-1), n=23; T (Untreated), n=6; N (Untreated), n=6; MPR, n=4; NPR, n=19. (J) Normalized expression of IL7R, ENTPD1, and GZMB genes between all samples in ITGAE+ CD69+ CD8+ T cells. Violin plot indicates the range of normalized expression; each black dot refers to a captured cell; width indicates number of cells at the indicated expression level. MPR, major pathological response; NPR, no pathological response; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; t-SNE, t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding.

CD8+ TRMs differentiation is critical for neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 treatment response

Having demonstrated that both the quantity and activated state of CD8+ TRMs are altered on anti-PD-1 treatment, we further focused on the correlation between CD8+ TRM differentiation and neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 response. We first divided CD8+ TRMs into four subgroups based on the expression of CD38 and CD39 identified previously (figure 2I and online supplemental figure 6A,B). Among CD8+ TRMs subgroups, the proportion of CD38+ CD39+ CD8+ TRMs was significantly elevated in neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 treated patients (figure 3A,B and online supplemental figure 6C). Moreover, CD38+ CD39+ CD8+ TRMs was enriched in the MPR groups (figure 3C,D and online supplemental figure 1). Correlation analysis showed that CD38+ CD39+ CD8+ TRMs were positively correlated with anti-PD1 therapeutic efficacy, while CD38− CD39− CD8+ TRMs were opposite (figure 3E,F and online supplemental figure 6E–G). Notably, this classification of CD8+ TRMs was verified at the genomic level based on a single-cell RNA-seq analysis (online supplemental figure 6H,I). Remarkably, UMAP showed a significant enrichment of CD38+ CD39+ CD8+ TRMs in the Part-PR group (figure 3G and online supplemental figure 6J–L). Further quantitative analysis and correlation analysis also showed CD38+ CD39+ CD8+ TRMs had a positive correlation with therapy efficacy (online supplemental figure 6M–O). In addition, clonal expansion of CD38+ CD39+ CD8+ TRMs was noted in the TME of patients received neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 treatment (figure 3H,I). Subgroup analysis showed that the clonal expansion of CD38− CD39− CD8+ TRMs was more significant in the Part-PR group than the Non-PR group, while the clonal expansion of CD38+ CD39− CD8+ TRMs and CD38+ CD39+ CD8+ TRMs showed the same trend (figure 3J). Interestingly, TCR diversity in CD38− CD39− CD8+ TRMs was more profound in the Part-PR group, while TCR diversity of CD38+ CD39− CD8+ TRMs and CD38+ CD39+ CD8+ TRMs was relatively low in the Part-PR group (figure 3K). Genomic analyses showed that the expression levels of precursor-related genes (IL7R, KLF2, TCF7, CCR7, LEF1, and SELL) were high in CD38− CD39− CD8+ TRMs (figure 3L). In addition, CD38+ CD39+ CD8+ TRMs expressed more cytotoxic (GZMH, GZMB, GZMA, and PRF1), effector (GNLY, NKG7, TNFRSF9, CD38, ENTPD1, and HLA-DRA), and immune checkpoint-related (PDCD1, LAYN, CTLA4, HAVCR2, TIGIT, and LAG3) genes (figure 3L). To further define the differentiation relationship between each subpopulation, pseudo-temporal analyses revealed that CD8+ TRMs evolved from CD38− CD39− precursor cells to CD38+ CD39+ terminal effector cells (figure 3M). These results suggest that the differentiation of CD8+ TRM effector cells from precursor cells holds the key for neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 response in NSCLC.

Figure 3. CD8+ TRMs differentiation correlates with the efficacy of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. (A) t-SNE plots embedding of CD8+ TRMs grouped by organizational source from non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tumor after anti-PD-1 immunotherapy (T (Anti-PD-1), n=23), untreated tumor tissues (T (Untreated), n=6) and untreated paired normal tissues (N (Untreated), n=6) by CyTOF using a PhenoGraph clustering scheme, with each cell color coded to indicate the associated cell types. (B) The box plot shows the percentages (left) and the absolute number (right) of different subgroups in CD8+ TRMs. T (Anti-PD-1) (red, n=23); T (Untreated) (blue, n=6); N (Untreated) (green, n=6). NS p≥0.05; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001. (C) The same t-SNE as (A), grouped by and different therapeutic effect. MPR (pathological residual tumor cells ≤10%, n=4), NPR (pathological residual tumor cells >10%, n=19). (D) The box plot shows the absolute number of different subgroups in CD8+ TRMs. MPR (orange, pathological residual tumor cells ≤10%, n=4); NPR (gray, pathological residual tumor cells >10%, n=19). NS p≥0.05; ***p<0.001. (E) Correlation analysis shows the correlation between the percentages of CD38+ CD39+ CD8+ TRMs and pathological residual rate in tumor after anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. n=23. (F) Correlation analysis shows the correlation between the percentages of CD38− CD39− CD8+ TRMs and pathological residual rate in tumor after anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. n=23. (G) UMAP embedding of transcriptional profiles for ITGAE+ CD69+ CD8+ T cells grouped by and different therapeutic effect from all NSCLC samples after anti-PD-1 treatment (n=6). Each dot represents a single cell, and each cell color coded to indicate the associated cell types. Non-PR (pathological residual tumor cells >60%, n=3), Part-PR (pathological residual tumor cells ≤60%, n=3). (H) The same UMAP as (G). Colors represent the types of clonotype. (I) The pie chart shows the proportion of different clonotypes in different CD8+ TRM subsets. T (Anti-PD-1), n=6. Colors represent the types of clonotype. (J) The bar graph shows the types of clonotype in different CD8+ TRM subsets. Non-PR (pathological residual tumor cells >60%, n=3), Part-PR (pathological residual tumor cells ≤60%, n=3). (K) The bar graph shows the count of TCR diversity in different CD8+ TRM subsets. Non-PR (pathological residual tumor cells >60%, n=3), Part-PR (pathological residual tumor cells ≤60%, n=3). (L) Heatmap of mean log-normalized expression of different genes in CD8+ T cells, standardized by Z score. T (Anti-PD-1), n=6. (M) Pseudotemporal analysis (Monocle2) of ITGAE+ CD69+ CD8+ T cells from all samples. T (Anti-PD-1), n=6. Arrows indicate possible differentiation directions. MPR, major pathological response; NPR, no pathological response; t-SNE, t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding.

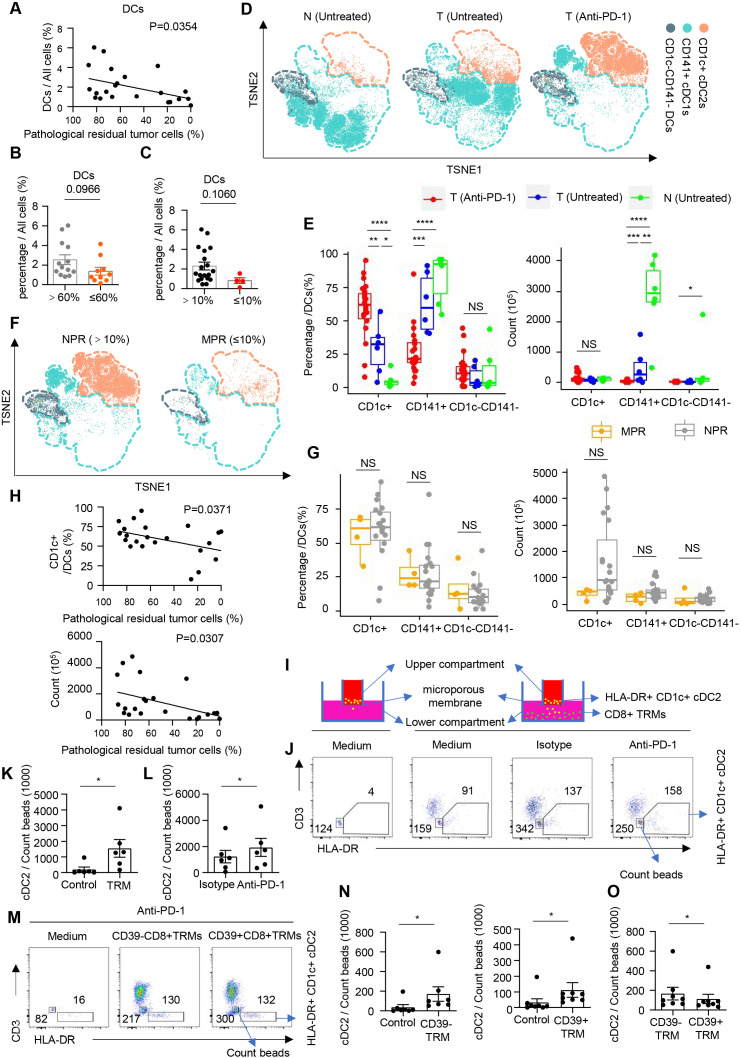

CD1c+ cDC2s are correlated with a poor neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 response

DCs are crucial for the priming, activation, and differentiation of CD8+ TRMs, but little is known about their role in the neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 response in human cancers. Surprisingly, the quantity of tumor-infiltrating DCs was negatively correlated with the PR of patients (figure 4A). Further analysis revealed that the proportion of tumor-infiltrating DCs had an upward trend in the Non-PR (pathological residual rate between 60% and 0%) groups than in the Part-PR (pathological residual rate higher than 60%) groups (figure 4B). According to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (seventh edition), the consistent conclusion was obtained using 10% as the threshold for the efficacy of pathological reactions (figure 4C). Using markers for different DC subsets, cDC1 (CD141+), and cDC2 (CD1c+), were identified, and the distribution of DC subsets within each group was compared (figure 4D and online supplemental figure 7A,B). We observed that CD141+ cDC1s exhibited different subsets or shifts in functional status among untreated normal lung tissue, untreated tumor tissue, and anti-PD-1 treated tumor tissue (figure 4D). In addition, we observed a considerable increase in the percentage of cDC2s in the anti-PD-1 group (figure 4E and online supplemental figure 7C). The percentage and the absolute number of cDC2s tended to be more in the Non-PR groups (figure 4F,G). Correlation analysis also showed that cDC2s were negatively correlated with immunotherapeutic efficacy (figure 4H). In contrast, the quantity of tumor-infiltrating cDC1 was decreased on anti-PD-1 therapy and was not correlated with immunotherapeutic efficacy (figure 4E and online supplemental figure 7D). To explore the underlying mechanism by which cDC2s were enriched in the NPR group and the connection between cDC2s and CD8+ TRMs, we sorted out CD8+ TRMs and CD1c+ cDC2s and used trans-well plates for a recruitment experiment (figure 4I and online supplemental figure 7E,F). We found that CD8+ TRMs could recruit cDC2s (figure 4J,K), and this recruitment was further enhanced by PD-1 blocking (figure 4L). Next, we separated the precursor of CD8+ TRMs and the effector cell of CD8+ TRMs to investigate the recruitment of cDC2s in vitro, and found that the recruitment of cDC2s was mainly induced by CD39− CD8+ TRM and CD39+ CD8+ TRM precursor on PD-1 blocking (figure 4M,N and online supplemental figure 7G), especial CD39− CD8+ TRM (figure 4O). Through single-cell RNA-seq analysis, we preliminarily listed the possible chemokines secreted by CD39− CD8+ TRM precursor (online supplemental figure 7H). These results show that the accumulation of CD1c+ cDC2s, which correlates with poor neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 treatment response, is mainly induced by CD8+TRM precursor on PD-1 blockade.

Figure 4. CD1C+ DCs recruited by precursor CD8+ TRMs are enriched in anti-PD-1 resistance groups. (A) Correlation analysis shows a correlation between the percentage of DCs and the rate of pathological tumor residual. Heatmap of mean log-normalized expression of different proteins in DCs. n=35. (B) The bar graph shows the percentage of DCs in all cells ≤60% (orange, pathological residual tumor cells ≤60%, n=10), >60% (gray, pathological residual tumor cells >60%, n=13). (C) The bar graph shows the percentages of DCs in all cells ≤10% (red, pathological residual tumor cells ≤10%, n=4), >10% (black, pathological residual tumor cells >10%, n=19). (D) t-SNE plots embedding of DCs grouped by organizational source from non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tumor after anti-PD-1 immunotherapy (T (Anti-PD-1), n=23), untreated tumor tissues (T (Untreated), n=6), and untreated paired normal tissues (N (Untreated), n=6) by CyTOF using a PhenoGraph clustering scheme, with each cell color coded to indicate the associated cell types. (E) The box plot shows the percentages (top) and the absolute number (bottom) of different subgroups in DCs. T (Anti-PD-1) (red, n=23); T (Untreated) (blue, n=6); N (Untreated) (green, n=6). NS p≥0.05; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001. (F) The same t-SNE as (B), grouped by different therapeutic effect. MPR (pathological residual tumor cells ≤10%, n=4), NPR (pathological residual tumor cells >10%, n=19). (G) The box plot shows the percentages (left) and the absolute number (right) of different subgroups in DCs. MPR (orange, pathological residual tumor cells ≤10%), n=4; NPR (gray, pathological residual tumor cells >10%), n=19. NS p≥0.05. (H) Correlation analysis shows the correlation between the percentages (top) or the absolute number (bottom) of CD1c+ DC2s and pathological residual rate in tumor after anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. n=23. (I) Experimental setup of in vitro recruitment assay. CD1c+ DC2s are cultured on transwell inserts (5 mm pore size) and CD8+ TRMs are plated in the bottom well. (J) Representative flow cytometric analysis of CD8+ TRMs and CD1c+ DCs in all live (7-AAD+) cells from NSCLC. CD1c+ DCs are cultured on transwell inserts and CD8+ TRMs are plated in the bottom well with nothing (medium), isotype (10 µg/mL) or anti-PD-1 (10 µg/mL) (DC: T=1:4). Cells sorting from untreated tumors were analyzed by flow cytometry. Numbers in plots indicate the absolute number of cells in respective gates. (K) The bar plot shows the absolute number of CD1c+ DCs per 1000 count beads. n=6. *p<0.05. (L) The bar plot shows the absolute number of CD1c+ DCs per 1000 count beads. n=6. *p<0.05. (M) Representative flow cytometric analysis of CD39+/− CD8+ TRM cells and CD1c+ DCs in all live (7-AAD+) cells from NSCLC. CD1c+ DCs are cultured on transwell inserts and CD39+/− CD8+ TRMs are plated in the bottom well with anti-PD-1 (10 µg/mL) (DC: T=1:4). Cells sorting from untreated tumors are analyzed by flow cytometry. Numbers in plots indicate the absolute number of cells in respective gates. (N) The bar plot shows the absolute number of CD1c+ DCs per 1000 count beads. n=8. *p<0.05. (O) The bar plot shows the absolute number of CD1c+ DCs per 1000 count beads. n=8. *p<0.05. DC, dendritic cell; MPR, major pathological response; NPR, no pathological response; t-SNE, t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding.

Galectin-9+ tumor cells inhibit cDC2 maturation via TIM-3

Conventionally, CD1c+ cDC2s have been considered as antigen presenting cells for CD4+ T cells.29 A recent study showed that CD11b+ cDC2s expressed MHC class I complexes and could promote the antitumor role of CD8+ T cells.30 We found no significant difference in the expression of PD-L1, PD-L2, and CTLA-4 among tumor-infiltrating CD1c+ cDC2 and CD141+ cDC1, while the expression of TIM-3 was specifically increased on tumor-infiltrating CD1c+ cDC2s and CD141+ cDC1, especially CD1c+ cDC2s (figure 5A,B). Further analysis showed that the expression of TIM-3 on tumor-infiltrating CD1c+ cDC2s was significantly increased in the anti-PD-1 group compared with untreated tumor, while CD141+ cDC1s showed no difference in TIM-3 expression (figure 5C). Meanwhile, the expression of TIM-3 was significantly increased in both tumor-infiltrating CD1c+ cDC2s and CD141+ cDC1s compared with untreated normal lung tissue (figure 5C). Subgroup analysis showed that TIM-3 expression on tumor-infiltrating CD1c+ cDC2s was increased in the Non-PR group (figure 5D). In contrast, TIM-3 expression on tumor-infiltrating CD141+ cDC1s was not different among groups (figure 5D). The elevated expression of HAVCR2 in tumor-infiltrating CD1C+ cDC2s was further validated by single-cell RNA-seq (figure 5E and online supplemental figure 8A–D). First, we also analyzed the expression of receptor genes related to DCs corresponding to CD39− CD8+ TRM cells, and found that the high expression of CXCR3, CXCR4, and CXCR6 was associated with CLEC10A+ CD1C+ cDC2s (online supplemental figure 8E). Recent studies have shown that TIM-3 inhibits DC maturation and function.31 32 Therefore, we detected the expression of CD86 and MHC class I complexes. We found that tumor-infiltrating CD1c+ cDC2s had a higher per cent of HLA-A/B/C positive cells than CD1c+ cDC2s in paired normal tissues, but the per cent of CD86 positive cells was decreased in tumor-infiltrating CD1c+ cDC2s (figure 5F and online supplemental figure 8F,G). Meanwhile, CD141+ cDC1s showed no difference (online supplemental figure 8H). When compared with CD86+ CD1c+ cDC2s, the per cent of HLA-A/B/C positive cells on tumor-infiltrating CD86− CD1c+ cDC2s was significantly decreased (figure 5G). Single-cell RNA-seq analysis also showed that the expression of HLA-A/B/C and CD86 in tumor-infiltrating CD1c+ cDC2s was significantly lower in the Non-PR group (figure 5H). Incorporating the latest research, these results suggest that tumor-infiltrating CD1c+ cDC2, especially in the Non-PR group, may be restrained for the expression of MHC class I complexes and CD86, which may result from its TIM-3 overexpression.31 Galectin-9 has been reported to interact with TIM3 and PD-1 to induce T cell death.33 To determine whether galectin-9 expression on tumor cells impact on cDC2 phenotype via TIM3, we sorted galectin-9+ tumor cells and cocultured them with tumor-infiltrating CD1c+ cDC2 in vitro (online supplemental figure 9A,B). Indeed, anti-TIM-3 significantly prevented galectin-9+ tumor cells from inhibiting the maturation and expression of MHC class I complexes on CD1c+ cDC2 (figure 5I and online supplemental figure 9C). Taken together, our results suggest that galectin-9+ tumor cells could inhibit the maturation and MHC class I complexes expression of tumor-infiltrating CD1c+ cDC2s via galectin-9/TIM-3 interaction, which ultimately restrain CD8+ TRMs antitumor activity.

Figure 5. Tumor cells inhibit the maturity of CD1c+ DC2 via galectin-9. (A) Heatmap of mean log-normalized expression of different proteins in dendritic cells (DCs). n=35. (B) The box plot shows the mean log-normalized expression of PD-L1, PD-L2, CTLA-4, and TIM-3 in DCs. n=35. NS p≥0.05; *p<0.05; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001. (C) The box plot shows the mean log-normalized expression of TIM-3 in CD141+ DC1s and CD1c+ DC2s. T (Anti-PD-1), n=23; T (Untreated), n=6; N (Untreated), n=6. NS p≥0.05; *p<0.05; ***p<0.001. (D) The box plot shows the mean log-normalized expression of TIM-3 in CD141+ DC1s and CD1c+ DC2s. Part-PR, n=10; Non-PR, n=13; T (Untreated), n=6. NS p≥0.05; *p<0.05. (E) Expression plots depict average Z-transformed normalized expression of common immune checkpoint genes in each subgroup of DCs in NSCLC after anti-PD-1 treatment. n=6. (F) The box plot shows the percentage of HLA-A/B/C+ (left) and CD86+ (right) in CD1c+ DC2s. T (Untreated), n=4; N (Untreated), n=4. *p<0.05. (G) The box plot shows the percentage of HLA-A/B/C+ in CD86− or CD86+ CD1c+ DC2s. T (Untreated), n=4; N (Untreated), n=4. **p<0.01. (H) Normalized expression of HLA-A and CD86 genes between all samples in CD1C+ CLEC10A+ DC2s. Violin plot indicates the range of normalized expression; each black dot refers to a captured cell; width indicates the number of cells at the indicated expression level. (I) CD1c+ DC2s and CD8+ TRMs are cocultured with galectin-9+ epithelial cells (Epi) with control, isotype (10 µg/mL) or anti-TIM-3 (10 µg/mL) treatment for 24 hours after anti-PD-1 (10 µg/mL) treatment in vitro (Epi:DC:T=5:1:1). Cells sorting from T (Untreated) (n=6) were analyzed by flow cytometry. The line graph shows the percentage of CD86 (left) and HLA-A/B/C (right) in CD1c+ DC2s. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Anti-TIM-3 promotes tumor killing activity of CD8+ TRMs and improves anti-PD-1 response

To further investigate the impact of tumor cells on tumor-infiltrating CD1c+cDC2 s and CD8+ TRMs, we conducted an in-depth analysis in bulk RNA-seq and single-cell RNA-seq data. First, we validated the protein expression of galectin-9 through immunofluorescent staining (figure 6A). Then, referring to the annotation of airway epithelium,34 35 we identified seven subpopulations of cancer cells, including AGER+ alveolar epithelial type 1-like cells, AREG+ alveolar epithelial type 2-like cells, ASCL1+ neuroendocrine like cells, KRT17+ basal like cells, MUC5B+ goblet like cells, STMN1+ proliferation cells, and TPPP3+ ciliated like cells (online supplemental figure 9D,E). Among these cancer cell subpopulations, AREG+ alveolar epithelial type 2-like cells formed the major subset of cancer cells in most samples (online supplemental figure 9F,G). In addition, the quantity of AGER+ alveolar epithelial type 1-like cells, AREG+ alveolar epithelial type 2-like cells and MUC5B+ goblet like cells showed a tendency to accumulate in Non-PR samples (online supplemental figure 9F,G). By inferring copy number variation analysis, we confirmed that these epithelial cells were cancer cells (online supplemental figure 9H). More importantly, we found that AGER+ alveolar epithelial type 1-like cells, AREG+ alveolar epithelial type 2-like cells, and MUC5B+ goblet like cells expressed a higher level of LGALS9 (galectin-9), which is the ligand of TIM-3, than other cancer cell subsets (figure 6B). Combining with the bulk RNA-seq, we found that the expression levels of airway epithelium related genes were significantly higher in the Non-PR groups (figure 6C). Further analysis showed that AGER+ alveolar epithelial type 1-like cells and AREG+ alveolar epithelial type 2-like cells uniquely expressed a high level of genes, including PIGR, PGC, CEACAM6, RAP1GAP, AQP4, CAPN8, PRR15L, SLC34A2, and TMPRSS2 (figure 6D). The unique genes expressed in MUC5B+ goblet like cells were also identified, including SCGB3A1, CAPN13, SPDEF, TSPAN8, and CCNO (figure 6D). According to the analysis of galectin-9+ epithelial cells-related genes detected by both bulk RNA-seq and mass spectrometry, the samples were divided into galectin-9 high and galectin-9 low groups. As the data from bulk RNA-seq show, galectin-9 high group expressed higher level of cDC2-related genes and lower level of CD8+ TRM-related genes (figure 6E). In addition, mass spectrometry showed that the galectin-9 high group had a higher proportion of tumor-infiltrating CD39−CD38− CD8+ TRMs and cCD1c+ cDC2, and a lower proportion of CD39+ CD38+ CD8+ TRMs (figure 6F). More importantly, the galectin-9 high group showed worse immunotherapy efficacy (figure 6F). To further investigate whether cancer cells can inhibit the antitumor role of CD8+ TRMs, we sorted tumor-infiltrating CD1c+ cDC2s and tumor-infiltrating CD8+ TRMs and cocultured them with human NSCLC A549 cells, which expressed a high level of galectin-9, in vitro (online supplemental figure 10A,B). We found that the percentage of CD39+ CD8+ TRMs was significantly increased in the presence of anti-TIM-3 (figure 6G and online supplemental figure 10C). In addition, we demonstrated that imcDC2s could enhance the cancer-killing activity of CD8+ TRMs, and TIM-3 blockade further enhanced the promoting effect of imcDC2s (figure 6H and online supplemental figure 10D). More importantly, the combination of TIM-3 with PD-1 blockade further enhanced the cancer-killing ability of CD8+ TRMs in vitro (figure 6I and online supplemental figure 10E). Collectedly, our results suggest that galectin-9+ tumor cells, such as AGER+ alveolar epithelial type 1-like cells, AREG+ alveolar epithelial type 2-like cells, and MUC5B+ goblet like cells, establish epithelium/imcDC2/CD8+ TRMs suppressive loop that is responsible for the resistance of neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy in NSCLC and can be reversed by anti-TIM-3.

Figure 6. Galectin-9+ epithelial cells (Epi) correlates with poor neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 response and limited tumor killing capacity of CD8+ TRMs. (A) Paraffin sections from non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients (scale bars represent 50 µm) were stained with anti-human Epcam (green), anti-human galectin-9 (red), and DAPI (blue) for immunofluorescent (IF) staining. (B) Expression plots depict average Z-transformed normalized expression of common immune checkpoint ligands genes in each subgroup of Epi in NSCLC after anti-PD-1 treatment. n=6. (C) Volcano plots presenting the differentially expressed genes between Part-PR groups and Non-PR groups. P<0.05, |LogFC|>1. (D) Expression plots depict average Z-transformed normalized expression of representative genes in each subgroup of Epi in NSCLC after anti-PD-1 treatment. n=6. (E) Heatmaps showing relative genes expression of galectin-9+ Epcam, cDC2, and CD8+ TRM. n=19. Standardized by Z score. (F) The box plot shows the percentage of CD39+ CD38+ TRM, CD39− CD38− TRM, CD1c+ cDC2 and pathological residual tumor cells in galecin-9 low or galecin-9 high tumor. n=19, *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ****p<0.0001. (G) A549 were cocultured with CD8+ TRMs and CD1c+ DC2s (1:2:2) for 24 hours with or without anti-TIM-3 (10 µg/mL) treatment in vitro. The line graph shows the percentage of CD39+ in CD8+ TRMs. T (Untreated), n=6; **p<0.01. (H) A549 were cocultured with CD8+ TRMs and CD1c+ DC2s (1:2:2) for 24 hours with or without anti-TIM-3 (10 µg/mL) treatment in vitro. The line graph shows the percentage of 7-AAD+ in A549. T (Untreated), n=9; *p<0.05, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. (I) A549 were cocultured with CD8+ TRMs and CD1c+ DC2s (1:2:2) for 24 hours with or without anti-PD-1 (10 µg/mL) or anti-TIM-3 (10 µg/mL) treatment in vitro. The line graph shows the percentage of 7-AAD+ in A549. T (Untreated), n=9; *p<0.05; **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

CD8+ TRMs and galectin-9 expression on tumor cells predict the outcome of anti-PD-1 therapy

To further integrate our results with clinical applications, we used the Kaplan-Meier plotter (www.kmplot.com) to investigate the predictive value of CD8+ TRMs and galectin-9+ tumor cells in a cohort of 797 patients with cancer receiving anti-PD-1 therapy.36 The datasets included multiple cancers, including bladder cancer, esophageal adenocarcinoma, glioblastoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, melanoma, and NSCLC, and all samples were taken before treatment. Using the marker genes of CD8+ TRMs and galectin-9+ tumor cells, we found that patients with higher expression levels of CD8+ TRMs-related genes (CD8A, ITGAE, and ZNF683) in their tumor had a better overall survival (OS) from anti-PD-1 immunotherapy (online supplemental figure 11A). In contrast, patients with higher expression levels of galectin-9+ tumor cell-related genes (CAPN13, SCGB3A1, CCNO, CYP4B1, TMPRSS2, and CEACAM6) had a worse OS from anti-PD-1 immunotherapy (online supplemental figure 11B). These results suggest that the marker genes of CD8+ TRMs and galectin-9+ tumor cell could be used to predict the outcome of anti-PD-1 therapy in multiple human cancers.

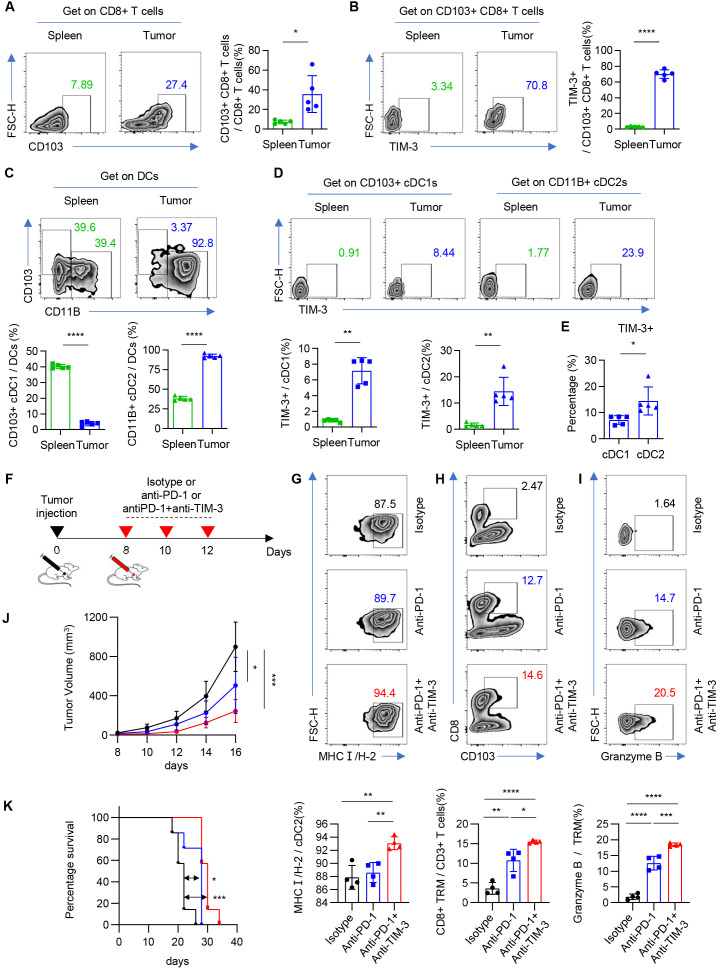

Combination of anti-TIM-3 and anti-PD-1 improves therapy efficacy and survival of tumor-bearing mouse through cDC2 and CD8+ TRMs

To further confirm our findings in vivo, we established an in vivo subcutaneous graft tumor model using Lewis cells (mouse lung carcinoma). We found that the number of galectin-9+ epithelial cells increased significantly in tumor than in normal lung tissue (online supplemental figure 12A,B). The flow gate strategy was shown in online supplemental figure 12A. The proportion of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ CD103+ T cells (TRMs) was significantly higher than spleen, and the percentage of TIM-3+ CD8+ CD103+ T cells was also significantly increased (figure 7A,B and online supplemental figure 12C). Meanwhile, we found that cDC2 was significantly accumulated in tumor, while cDC1 was mainly enriched in spleen (figure 7C). Although the expression of TIM-3 was significantly increased in both cDC1 and cDC2, the percent of TIM-3 expression in cDC2 is higher than that in cDC1 (figure 7D,E). In summary, the enrichment of TIM-3+ cDC2 and CD8+ TRMs was further verified in immune competent murine tumor model.

Figure 7. Mouse model and in vivo research. (A) Representative flow cytometric analysis of CD103+ CD8+ T cells in CD8+ T cells. Numbers in plots indicate the positive percentage of cells in respective gates (left). The bar graph shows the percentage of CD103+ CD8+ T cells in CD8+ T cells. n=5. *p<0.05 (right). (B) Representative flow cytometric analysis of TIM-3+ cells in CD103+ CD8+ T cells. Numbers in plots indicate the positive percentage of cells in respective gates (left). The bar graph shows the percentage of TIM-3+ cells in CD103+ CD8+ T cells. n=5. ****p<0.0001 (right). (C) Representative flow cytometric analysis of CD103+ cells or CD11B+ cells in cDCs. Numbers in plots indicate the positive percentage of cells in respective gates (top). The bar graph shows the percentage of CD103+ cells or CD11B+ cells in cDCs. n=5. ****p<0.0001 (bottom). (D) Representative flow cytometric analysis of TIM-3+ cells in CD103+ cDC1s or CD11B+ cDC2s. Numbers in plots indicate the positive percentage of cells in respective gates (top). The bar graph shows the percentage of TIM-3+ cells in CD103+ cDC1s or CD11B+ cDC2s. n=5. **p<0.01 (bottom). (E) The bar graph shows the percentage of TIM-3+ cells in CD103+ cDC1s or CD11B+ cDC2s. n=5. *p<0.05 (bottom). (F) Pattern diagram shows mice were given anti-TIM-3 antibody, anti-mPD-1 antibody, or isotype starting on the eighth day after tumor inoculation and treated on the indicated days for a total of three treatments. (G) Representative flow cytometric analysis of MHCI(H-2) cells in CD11B+ cDC2s. Numbers in plots indicate the positive percentage of cells in respective gates (top). The bar graph shows the percentage of MHCI(H-2) cells in CD11B+ cDC2s. n=4. **p<0.01 (bottom). (H) Representative flow cytometric analysis of CD103+ CD8+ T cells in CD3+ T cells. Numbers in plots indicate the positive percentage of cells in respective gates (top). The bar graph shows the percentage of CD103+ CD8+ T cells in CD3+ T cells. n=4. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001 (bottom). (I) Representative flow cytometric analysis of granzyme B+ cells in CD103+ CD8+ T cells. Numbers in plots indicate the positive percentage of cells in respective gates (top). The bar graph shows the percentage of granzyme B+ cells in CD103+ CD8+ T cells. n=4. ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 (bottom). (J) Tumor growth in mice bearing Lewis tumors. Mice were given anti-TIM-3 antibody, anti-mPD-1 antibody, or isotype. n=7. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001. Data are presented as the mean±SEM. (K) Survival of mice bearing Lewis tumors. Mice were given anti-TIM-3 antibody, anti-mPD-1 antibody, or isotype. n=7. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001.

In order to further verify the role of galectin-9/TIM-3/imcDC2 axis in ICI-resistance, we investigated the impact of anti-TIM-3 on the function of tumor-infiltrating cDC2 and CD8+ TRMs in vivo (figure 7F). Compared with anti-PD-1 and isotype therapy group, the percentage of MHC class I+ cDC2 was significantly increased in the anti-PD-1 and anti-TIM-3 combination therapy group, which was consistent with the finding of in vitro experiment (figure 7G). In addition, the proportion of CD8+ TRMs and the secretion of granzyme B were significantly increased in the group receiving anti-PD-1 and anti-TIM-3 combination therapy compared with anti-PD-1 and isotype therapy group (figure 7H,I). Finally, as expected, the group receiving combination therapy of anti-PD-1 and anti-TIM-3 showed more significantly slower tumor growth and longer survival than the group receiving anti-PD-1 therapy compared with isotype group (figure 7J,K). Therefore, our in vivo experiment verified the findings of in vitro coculture experiments and demonstrated that combination therapy of anti-TIM-3 and anti-PD-1 could improve the therapy efficacy and survival of tumor-bearing mouse through enhancing the antigen presentation of cDC2 and tumor killing effect of CD8+ TRMs.

Discussion

Understanding the mechanism of ICI resistance in advanced cancers is a rapidly growing research field.3 5 However, the underlying mechanism of neoadjuvant ICI therapy resistance in non-advanced cancer remains unclear. Our study was conducted in the early application of anti-PD-1, and the frequency and cycle of the study application are different from the current treatment regimen. But our study is credible and tries to provide some clues for the latest resistance research. Here, we used a cohort of non-advanced human NSCLC receiving short-term neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy, we discovered that this therapy induced a dramatic change in the TME of patients. Notably, we found a positive correlation between the quantity of effector cell subset of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ TRMs and the PR of patients, and the quantity of precursor cells of CD8+ TRMs and imcDC2s negatively correlated with the PR of patients. There was a possibility that CD8+ TRM enrichment was found in sites de-enriched for tumor cells, while it requires more research to explain the occurrence of this condition. Additionally, we discovered that anti-PD-1 therapy could induce the recruitment of DC2s by tumor-infiltrating CD8+ TRMs, especially CD8+ TRM precursors, but these cDC2s exhibited an immature phenotype with elevated TIM-3 expression that restrained the generation of CD8+ TRM effector cells. Subsequently, we identified that the cancer cell subpopulation that suppresses the maturation of cDC2 in a galectin-9-TIM-3 pathway-dependent manner. We demonstrated that combining anti-TIM-3 with anti-PD-1 could rescue the maturation of imcDC2 and promote the cancer-killing effect of CD8+ TRMs in vitro. Finally, we found that the marker genes of CD8+ TRMs and cancer cells could predict the outcome of patients receiving anti-PD-1 therapy. Based on these findings, we propose a working model outlining the key factors in the TME of human NSCLC that determine response versus resistance to neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy. Our data suggest that neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy resistance could be partially overcome by anti-TIM3 treatment.

As only a fraction of patients benefit from ICIs, predictive markers for ICIs therapy are urgently needed.2 37 Among tumor-infiltrating immune cells, the quantity of CD8+ T cells has been demonstrated to correlate with the response of ICIs in advanced cancers.7 10 11 13 38 39 However, the correlation between CD8+ T cells and response to neoadjuvant ICIs in non-advanced cancers is largely unknown. Recently, neoantigen-specific tumor-infiltrating T cells with the transcriptional feature of tissue residency were shown to correlate with the neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 response in breast cancer and NSCLC.18 26 Consistently, we demonstrated that the quantity of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ TRMs was positively correlated with neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 response of non-advanced NSCLC. In addition, we found that a higher proportion of effector cells (CD38+ CD39+ CD103+ CD69+ CD8+ T cells) in CD8+ TRMs correlated with better anti-PD-1 response, which is consistent with the finding of CD39+ CD8+ T cells in advanced NSCLC.40 While a higher proportion of precursors (CD38− CD39− CD103+ CD69+ CD8+ T cells) in CD8+ TRMs was correlated with worse anti-PD-1 response. Furthermore, we demonstrated that CD39− CD8+ TRM precursors predominately recruit imcDC2, another immune cell subpopulation which correlated with worse anti-PD-1 response. It is interesting that a previous study reported the tumor-infiltrating CD39+ CD8+ T cell population with exhausted phenotype was correlated with the non-response of anti-PD-1 palliative treatment in advanced melanoma,10 suggesting that tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells participating in the anti-PD-1 response are heterogenous depending on different cancer types, stages, and duration of treatment.

DCs are a heterogeneous population of specialized antigen-presenting cells with fundamental roles in the initiation and regulation of both innate and adaptive immune responses.41 Recently, CD1c+ cDC2s were demonstrated to promote the differentiation of CD8+ TRMs in a TGF-β-dependent manner.42 In addition, a CD163+ subset of human CD1c+ DC3s was reported to prime CD8+ TRMs and was correlated with CD8+ TRMs accumulation in breast tumor.43 These findings suggest that CD1c+ cDCs play a pivotal role in the accumulation and differentiation of human CD8+ TRMs in the TME. Unexpectedly, we found CD1c+ cDC2s were significantly accumulated in the TME of patients with poor response to neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy. These CD1c+ cDC2 were immature and showed a tolerogenic phenotype characterized by the elevated TIM-3 expression, which is analogous to the TIM-3+ cDCs in mouse models.44 Furthermore, we demonstrated that these tumor-infiltrating CD1c+ cDC2 could inhibit the differentiation and cancer cell-killing ability of CD8+ TRMs. Collectively, our study identifies a novel TIM-3+ subpopulation of tumor-infiltrating CD1c+ cDC2s that is involved in anti-PD-1 resistance by inhibiting CD8+ TRMs in the TME.

Accumulating evidence suggests that tumor-intrinsic factors, such as genetic and signaling defects of cancer cells, are correlated with the efficacy and resistance of ICIs therapy in advanced cancers.2 3 37 45 However, factors involved in resistance of neoadjuvant ICIs therapy of early NSCLC remain unclear. Our previous study showed that the epithelial origin of tumor cells plays a crucial role in the TME-formation and immune dysfunction of early thymic epithelial tumor.46 This finding implies that the epithelial origin of cancer cells may serve as an alternative intrinsic factor that impacts the TME-formation and ICIs therapy efficacy in early stage NSCLC. We further identified the epithelium-origin of cancer cells in NSCLC and demonstrated that cancer cells with elevated galectin-9 expression were associated with the immune desert TME and poor response of ICIs therapy. Furthermore, we observed that these cancer cells could secrete a high level of galectin-9 that inhibits the maturation of CD1c+ cDC2s through interaction with TIM-3. In addition, we found that combination of anti-TIM-3 and anti-PD-1 could promote cDC2 maturation and cancer cell-killing effect of CD8+ TRMs in vitro. Moreover, survival analysis in patients consistently demonstrated that the expression levels of marker genes of galectin-9+ cancer cells were negatively correlated with the survival of ICIs therapy in multiple cancers. Furthermore, we used the Lewis mouse model to test our idea. Taken together, our study suggested that patients with increased expression levels of marker genes of galectin-9+ cancer cells including CAPN13, SCGB3A1, CCNO, CYP4B1, TMPRSS2, and CEACAM6 detected by preoperative genetic testing or cDC2 highly enriched on immunohistochemistry should be advised to combination immunotherapy or anti-TIM-3 therapy after anti-PD-1 resistance. More importantly, our study identifies an epithelial/imcDC2 suppressive loop that supports galectin-9/TIM-3 guided primary resistance of neoadjuvant ICIs therapy in human NSCLC. It suggested that DCs were also an important target for immunotherapy in addition to CD8+ TRMs.

Resistance is a major obstacle for patients with cancer to benefit from ICIs. Uncovering the mechanism of ICIs resistance in cancer and developing strategy to overcome it is urgently needed. Here, we demonstrate that an intact CD1c+cDC2/CD8+ TRMs axis is key for successful neoadjuvant ICIs therapy in human NSCLC. Moreover, a tumor-intrinsic epithelium/imcDC2 suppressive loop is identified and demonstrated to promote ICIs resistance in human NSCLC. In addition, we demonstrate that the combination of anti-TIM-3 could overcome anti-PD-1 resistance by breaking the epithelium/imcDC2 suppressive loop. Collectively, our findings uncover the crucial role of the tumor-intrinsic suppressive loop in anti-PD-1 resistance and suggest that combined treatment of anti-TIM-3 and anti-PD-1 is a promising approach in the neoadjuvant ICIs therapy of human NSCLC.

Methods

Patients and specimens

27 patients with histologically proven NSCLC were allowed to participate in the study. The pathological diagnosis was confirmed by the pathology Department of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University. None of the patients had received radiotherapy or chemotherapy before surgery. Neoadjuvant therapy regimens are performed according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines on NSCLC. The clinical physician is responsible for the formal implementation of systemic therapy and the execution of surgery. Treated (anti-PD-1, homogeneous cellularity, without foci of necrosis) and untreated tumor tissues (T), untreated paired normal lung tissues (N) were obtained from patients with NSCLC who underwent surgical resection. Normal autologous tissue was obtained from a macroscopically normal part of the excised pulmonary lobe, at least 5 cm away from the tumor.

Clinical trial protocol

Clinical trial was approved by The National Institutes of Health (NIH). Anti-PD1 agents used in this clinical trial including nivolumab and pembrolizumab. The details of inclusion/exclusion criteria were listed in online supplemental table 1. Patients eligible for the clinical trial were selected by clinicians. The first CT scan of pretreatment and tumor biopsy before treatment was performed on day 0. For nivolumab, 3 mg/kg was used for each patient on day 1 and day 14 after the start of treatment, and surgery was performed on day 30±3. For pembrolizumab, 200 mg or 100 mg was used on day 1 after the start of treatment, and surgery was performed on day 21±3. Before the surgery was performed, the second CT scan post-treatment was taken.

Methodology to quantify PR

Percent response is calculated as residual volume of tumor/tumor bed, which was composed of necrosis, fibrosis, inflammation, and residual volume of tumor, and then averaged the calculation of five complete sections to obtain the final assessment. This methodology to quantify PR is recommended by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer for improving consistency of pathological assessment of treatment response and is generally accepted.

Tumor cell lines

A549 (human lung carcinoma) cells and Lewis (Mouse lung carcinoma) cells were grown in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 growth medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin and streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2 and maintained at a confluence of 70%–80%.

Preparation of cell suspensions

Freshly excised tissues were stored in sterile RPMI (Corning) supplemented with 10% FBS (Life Technologies) and 1% streptomycin and penicillin (Life Technologies) and processed within 2 hours. The tissues were cut into small pieces and then digested in RPMI containing 10% FBS, type I collagenase (1 mg/mL), and type IV collagenase (1 mg/mL) for 1 hour at 37°C using a gentleMACSTM Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting single-cell suspension was filtered sequentially through sterile 70 µm cell strainers. Then, the cell suspensions were stored in a complete medium at 4°C for subsequent experiments.

H&E staining and image acquisition

For H&E analyses, NSCLC tumor tissues and paired normal tissues were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned transversely. The 5 μm-thick formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections on glass slides were incubated at 37°C overnight, dewaxed in xylene, rehydrated through decreasing concentrations of ethanol, and washed in PBS. Then, the sections were stained with H&E. After staining, the sections were dehydrated through increasing concentrations of ethanol and xylene. The slides were scanned with a KF-PRO-120 scanner (KFBIO).

Antibodies and flow cytometry

The antibodies CD45-BV510 (Clone #2D1, Cat#:368525, diluted 1:100), CD45-APCCY7 (Clone #HI30, Cat#:304014, diluted 1:100), CD3-BV421 (Clone #UCHT1, Cat#:300433, diluted 1:100), CD3-BV605 (Clone #UCHT1, Cat#:300459, diluted 1:100), CD3-APCCY7 (Clone #UCHT1, Cat#:300425, diluted 1:100), CD3-PECY7 (Clone #UCHT1, Cat#:300420, diluted 1:100), CD8a-APCCY7 (Clone #RPA-T8, Cat#:301016, diluted 1:100), CD8a-AF700 (Clone #RPA-T8, Cat#:301028, diluted 1:100), CD103-BV605 (Clone #Ber-ACT8, Cat#:350218, diluted 1:100), CD103-FITC (Clone #Ber-ACT8, Cat#:350204, diluted 1:100), CD69-PECY7 (Clone #FN50, Cat#:310911, diluted 1:100), CD69-PerCP-Cy5.5 (Clone #FN50, Cat#:310925, diluted 1:100), CD39-PE (Clone #A1, Cat#:328207, diluted 1:100), EPCAM-PE (Clone #9C4, Cat#:324205, diluted 1:100), EPCAM-APC (Clone #CO17-1A, Cat#:369809, diluted 1:100), 7-AAD (Cat#:420404, diluted 1:200), CD3-FITC (Clone #UCHT1, Cat#:300406, diluted 1:100), CD19-FITC (Clone #HIB19, Cat#:302206, diluted 1:100), CD20-FITC (Clone #S18015E,Cat#:375508, diluted 1:100), CD56-FITC (Clone #HCD56,Cat#:318304, diluted 1:100), CD14-FITC (Clone #HCD14,Cat#:325604, diluted 1:100), CD11c-PECY7 (Clone #S-HCL-3, Cat#:371508, diluted 1:100), HLA-DR-BV510 (Clone #L243, Cat#:307646, diluted 1:100), CD1c-APC (Clone #L161,Cat#:331524, diluted 1:100), Galectin-9-APC (Clone #9M1-3, Cat#:348908, diluted 1:100), CD86-PE (Clone #IT2.2, Cat#:305406, diluted 1:100), HLA-A,B,C-FITC (Clone #W6/32, Cat#:311404, diluted 1:100), Zombie Violet Fixable Viability Kit (Cat#:423113), CD45-APCCY7 (Clone I3/2.3, Cat#:147718, diluted 1:100), H-2Kd/H-2Dd-PE (Clone 34-1-2S, Cat#:114708, diluted 1:100), CD11b-BV510 (Clone M1/70, Cat#:101263, diluted 1:100), I-A/I-E-FITC (Clone M5/114.15.2, Cat#:107606, diluted 1:100), CD3-AF700 (Clone 17A2, Cat#:100216, diluted 1:100), granzyme B-PE (Clone QA16A02, Cat#:372208, diluted 1:100), CD11c-PECY7 (Clone N418, Cat#:117318, diluted 1:100), CD8-FITC (Clone 5H10-1 Cat#:100804, diluted 1:100), CD103-BV605 (Clone 2E7 Cat#:121433, diluted 1:100), CD3-PECY7 (Clone 17A2 Cat#:100220, diluted 1:100), EPCAM-FITC (Clone #G8.8, Cat#:118207, diluted 1:100), galectin-9-PE (Clone #RG9-35, Cat#:136103, diluted 1:100) were procured from BioLegend.

For extracellular protein staining, we preincubated fresh tissue cells (1×106/mL) in a mixture of PBS, 2% fetal calf serum, and 0.1% (w/v) sodium azide with FcgIII/IIR-specific antibody to block non-specific binding and stained them with different combinations of fluorochrome-coupled antibodies for 15 min at room temperature. Cells were washed with PBS and passed through a 70 µm filter. 7-AAD Viability Staining Solution was added 15 min before data capture to screen out the dead cells and data was collected on a FACSCanto II system and FACSFortessa system (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (V.10.0.7). For intracellular factor (granzyme B) staining, we replaced 7-AAD with Zombie Violet dye, which was added at the time of extracellular protein staining. After completion of the extracellular protein staining, 250 µL Pharmingen Fixation Buffer (BD Biosciences) was added. The cells were incubated for 25 min at 4°C. The cells were resuspended in two times the volume of Permeabilization Buffer (BD Biosciences). Finally, the intracellular factor dye was added and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After resuspension, data were collected on a FACSCanto II system and FACSFortessa system (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (V.10.0.7).

Bulk RNA-seq acquisition and analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the sample tissue block using TRIzol reagent and isolated using a TRIzol-chloroform extraction. The RNA-containing aqueous layer was collected, purified using the RNeasy MinElute Cleanup Kit (QIAGEN) following manufacturer’s instructions, and submitted to The Beijing Genomics Institute for library preparation and sequencing. The data obtained were analyzed by R (V.4.1.3).

Mass cytometry (CyTOF) sample preparation

The 42 metal-conjugated antibodies used in this study are shown in online supplemental table 4. Briefly, the cells derived from the NSCLC samples were stained with 5 µM cisplatin (Fluidigm) in PBS without bovine serum albumin (BSA) for viability staining. Then, the samples were washed in PBS containing 2.5% BSA and blocked for 30 min at 4°C. After that, they were stained with cell-surface antibodies in PBS containing 5% goat serum and 30% BSA for 30 min at 4°C. Next, the samples were washed, fixed, and permeabilized using the Foxp3 fix and permeabilization kit (eBioscience) as well as 100 nM iridium nucleic acid intercalator (Fluidigm) according to the manufacturer’s instructions at 4°C overnight. The cells were then washed twice with Foxp3 permeabilization buffer and incubated with intracellular antibodies in permeabilization buffer for 30 min at 4°C. Finally, the cells were washed twice with ddH2O to prepare them for analysis.

CyTOF data acquisition and analysis

Immediately before acquisition, samples were washed and resuspended at a concentration of 1 million cells/mL in water containing EQ Four Element Calibration Beads (Fluidigm). Samples were acquired on a Helios CyTOF System (Fluidigm) at an event rate of <500 events/s. EQ beads (Fluidigm) were used as a loading control. All data were produced on a Helio3 CyTOF Mass Cytometer (Fluidigm). Mass cytometry data files were normalized using bead-based normalization software, which uses the intensity values of a sliding window of bead standards to correct for instrument fluctuations over time and between samples. CyTOF analyses were performed by PLTTech Inc. (Hangzhou, China) according to a previously described protocol.47 The data were gated to exclude residual normalization beads, debris, dead cells, and doublets for subsequent clustering and high dimensional analyses. 42 immune cell markers were all applied for clustering and visualization. The Phenograph,48 PARC, and Xshif algorithms were used to cluster the cells. A total of 50 000 cells were selected randomly for visualization by the t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) dimension reduction algorithm49 using the R package cytofkit (V.0.13). Immune subset cells were defined by the median values of specific expression markers in hierarchical clustering. Heatmaps of normalized marker expression, relative marker expression, and relative differences in population frequency were generated using the pHeatmap R package and Python (https://www.python.org/). Comparisons between two groups were performed by unpaired Student’s t-tests using GraphPad Prism (V.8). The use of these tests was justified based on an assessment of the normality and variance of the distribution of the data.

Single-cell RNA sequencing

Trypan blue was used for quality evaluations of single-cell suspensions prepared as outlined earlier, and the cell survival rate was generally above 80%. The cells that passed the test were washed and resuspended to prepare a suitable cell concentration of 1000 cells/µL for 10× Genomics Chromium. Approximately 10,000 cells were loaded onto the 10× Chromium Single Cell Platform (Single Cell 5′ library and Gel Bead Kit V.3) as described in the manufacturer’s protocol. The generation of gel beads in emulsion (GEMs), barcoding, GEM-RT clean-up, complementary DNA amplification, and library construction were all performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Qubit (Agilent 2100) was used for library quantification before pooling. The final library pool was sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 instrument using 150 base-pair paired-end reads.

Single-cell gene expression analysis

Raw gene expression matrices were generated using CellRanger (10× Genomics) and analyzed using the Seurat V.3 R package. During the initial filtering process, cells expressing less than 300 genes and genes expressed in less than three cells were removed. Cells with high unique feature counts, high mitochondrial transcript counts, high ribosomal transcript counts, and high were filtered from the analysis. Samples were merged and normalized. Because every cell has a unique barcode, the scRNA-seq data could be linked with the scTCR-seq data.

scRNA-seq clustering analysis

The LogNormalize method of the “Normalization” function of Seurat software was used to calculate the expression values of genes. PCA was performed using the normalized expression value. Among all the PCs, the top 10 PCs were used to perform clustering and t-SNE analysis. We used the shared nearest neighbor graph-based clustering algorithm from the Seurat package (FindClusters function with default parameters) to identify clusters of cells. These clusters were then identified as distinct cell subtypes based on highly expressed genes from a literature review.

Differential expression and pathway analysis

The linear models for microarray data (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html) package in Bioconductor was used to identify DEGs. The corresponding p value of the gene symbols after t-test was used, and adjusted p<0.05 and log2FC>1 were used as the selection criteria.

The pHeatmap and volcano package (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/heatmaps.html) was used to draw a heatmap and volcano of the DEGs in R software.

GO is a major bioinformatics tool for annotating genes and analyzing their biological processes. KEGG is a database resource for understanding high-level functions and biological systems from large-scale molecular datasets generated by high-throughput experimental technologies. The clusterProfiler package (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html) in Bioconductor was used to perform the GO and KEGG pathway analysis of the DEGs. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Pseudotime reconstruction and trajectory inference

The R package Monocle (V.2) algorithm was used to reconstruct pseudotime trajectories to determine the potential lineage development among diverse T-cell subsets and epithelial cell subsets.50 For each analysis, PCA-based dimension reduction was performed on DEGs of each phenotype, followed by two-dimensional visualization on UMAP. Graph-based clustering (Louvain) sorted the TRM cells into seven subsets. The cell differentiation trajectory was then captured using the orderCells function. As described previously for differential gene expression analyses, the R package MAST was used to detect genes significantly covarying with pseudotime based on a log-likelihood ratio test between the model formula, including cell pseudotime, and a reduced model formula. Additional model covariates were included in the residual model formula. Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction was used to calculate the false discovery rate (FDR), and genes with an FDR<5% were considered to vary significantly with pseudotime. For T cells from different groups, the same process with the same signature genes and Monocle parameters was used to construct the clone-based trajectories.

TCR analysis

Full-length TCR V(D)J segments were enriched from amplified cDNA via PCR amplification using a Chromium Single-Cell V(D)J Enrichment kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (10× Genomics). 10× TCR-enriched libraries were mapped with the Cell Ranger Single-Cell Software Suite (V.4.0.0, 10× Genomics) to the custom reference provided by the manufacturer (V.2.0.0 GRCh38 VDJ reference). All assembled contigs were filtered to retain only those that were assigned a raw clonotype ID and categorized as being both full-length and productive. Each clonotype was assigned a unique identifier, consisting of the predicted amino acid sequences of the CDR3 regions of these two chains, which was used to match clonotypes across samples. Clonality, which reflects the dominance of particular clones across the TCR repertoire, was calculated for each sample. To visualize the proportion of TCR clonotypes shared between T-cell phenotypes, we used barcode information to project T cells with prevalent TCR clonotypes on UMAP plots.

Cell isolation and in vitro coculture

After antibody staining, CD45+ CD3+ CD8+ CD69+ CD103+ (CD39+/−) T cells, CD45+ CD3− CD19− CD20− CD56− HLA-DR+ CD11C+ CD1C+ DCs, CD45− EPCAM+ galectin-9+/− epithelial cells were sorted by an Aria II cell sorter (BD Biosciences), and 7-AAD was used to eliminate dead cells. The purity of all sorted cells was greater than 90%. For cell recruitment experiments, 5 mm pore size trans-well inserts were used. CD8+ (CD39+/−) TRMs were plated in the bottom well, while CD1C+ DCs were cultured on trans-well inserts (TRM: DC=4:1). Recruitment lasted for 2 hours. The counting microspheres were added before testing on the machine. For coculture experiments, CD1C+ DCs and CD8+ TRMs were placed in a 1: 1 ratio in a 96-well plate for 24 hours. While galectin-9+/− epithelial cells, CD1C+ DCs, and CD8+ TRMs were placed in a 5: 1: 1 ratio in a 96-well plate for 24 hours. Anti-PD-1, isotype, and anti-TIM-3 were used 10 µg/mL in all experiments. To visualize the tumor-killing power of CD8+ TRMs, the sorted CD1C+ DCs and CD8+ TRMs were resuspended in a 1: 1 ratio in a 96-well plate with 2 W medium per well. After standing for 24 hours, the A549 cell line was added for cocultivation according to E (effector cell): T (tumor cell line)=2:1. After 6 hours, use 7-AAD to detect the number of dead cells in A549. Anti-PD-1, isotype, and anti-TIM-3 were used 10 µg/mL in all experiments.

Immunofluorescence staining and image acquisition

The 5 μm-thick FFPE sections were also incubated at 37°C overnight, dewaxed in xylene, rehydrated through decreasing concentrations of ethanol, and washed in PBS. Antigen retrieval was performed in target retrieval solution citrate buffer (pH 6.0) using a pressure cooker. Then, the sections were blocked with a blocking buffer solution (5% FBS, 1% BSA, and 0.2% Triton) for 2 hours at room temperature and incubated with the primary antibody in blocking buffer (BioLegend) at 4°C overnight. After washing with PBS (pH 7.4), polymer horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated secondary antibody staining was performed at room temperature for 1 hour. Tyramide signal amplification-based visualization was performed with Opal fluorophores. Next, the sections were washed three times with PBST, and DAPI reagent was added for 10 min to detect cell nuclei. Antibodies against galectin-9 (#54330, diluted 1:300) were procured from Abcam. Antibodies against Epcam (ab223582, diluted 1:200) were procured from Cell Signaling. HRP conjugated Goat Anti-Mouse/Anti-Rabbit secondary antibodies (ab2891, 1:200) were procured from Abcam. Epifluorescence multispectral whole-slide images of all sections were acquired through the NIKON ECLIPSE C1 system (Nikon Corporation) and scanned at high resolution on a Pannoramic SCAN II system (3DHISTECH Ltd).

Mouse tumor model and in vivo research

Animals research ethics approval was approved by the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine ((2022)伦审研第(0523)号). Six-week-old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. Mice were maintained at the Zhejiang Chinese Medical University Laboratory Animal Research Center. Mice were maintained at specific-pathogen free (SPF) health status in individually ventilated cages at 21°C–22°C and 39%–50% humidity, under 12 hours of light-dark cycles. Mouse Lewis cells (5×104 cells) in 100 µL of 1640 complete culture medium were injected into the right armpit of mice. Eight days after inoculation, 100 µg mouse anti-PD-1 antibody (BioXcell, Clone: 29F.1A12, Cat#: BE0273), anti-TIM-3 antibody (BioXcell, Clone: RMT3-23, Cat#:BE0115) or isotype (BioXcell, Clone: 2A3, Cat#: BE0089) was injected intraperitoneally every other day for a total of three injections. Tumor volume was measured using the formula: 0.52×length×width,2 where length is the longest diameter of the tumor and width is the shortest diameter. Survival analysis was performed using Prism V.8.3 (GraphPad Software). A mouse tumor volume of 1500 mm3 was set as the endpoint. After the tumor volume reached the endpoint size, tumors were harvested and degraded into a single-cell suspension by collagenase four (BD Biosciences) for flow cytometry. Ethical approval for mouse experiments was obtained by The Animal Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism V.8.3 (GraphPad Software). Two-sided Student’s t-tests were used to identify differences between two groups. One-way analysis of variance was used to identify differences between three or more groups. All results are presented as the mean±SEM, and p values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, and ****p<0.0001).

Data availability

The OS was analyzed using an online database, Kaplan-Meier Plotter (www.kmplot.com). To analyze the OS, patient samples were split into two groups by median expression (high vs low expression) and assessed by a Kaplan-Meier survival plot, with the HR with 95% CIs and log-rank p value. The raw mass spectrometry flow cytometry data reported in this paper has been deposited in the OMIX in National Genomics Data Center under the accession number OMIX003278 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/omix/preview/yzqRgJcq). The bulk RNA-seq data reported in this paper has been deposited in the OMIX in National Genomics Data Center under the accession number OMIX003277 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/omix/preview/aGcthxdw). The data will be available for download after December 31, 2024. The raw scRNA-seq data reported in this paper has been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive in National Genomics Data Center under the accession number HRA003360. The data will be available for download after March 2, 2025. To comply with the “Guidance of the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) for the Review and Approval of Human Genetic Resources,” raw data can be obtained by request to the corresponding authors (pinwu@zju.edu.cn) and following the guidelines for Genome Sequence Archive for non-commercial use at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/request/HRA003360. There are no time restrictions once access has been granted. The guidance for making a data access request of GSA for humans can be downloaded from https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/document/GSA-Human_Request_Guide_for_Users_us.pdf. The remaining data were available within the Article, Supplementary Information, or Source Data file. Source data are provided in this paper.

This paper does not report original code.