Abstract

In 2020 Medicare began reimbursing for opioid treatment program (OTP) services, including methadone maintenance treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD), for the first time. Methadone is highly effective for OUD, yet its availability is restricted to OTPs. We used 2021 data from the National Directory of Drug and Alcohol Abuse Treatment Facilities to examine county-level factors associated with OTPs accepting Medicare. In 2021, 16.3 percent of counties had at least one OTP that accepted Medicare. In 124 counties the OTP was the only specialty treatment facility offering any form of medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD). Regression results showed that the odds of a county having an OTP that accepted Medicare were lower for counties with higher versus lower percentages of rural residents and lower for counties located in the Midwest, South, and West compared with the Northeast. The new OTP benefit improved the availability of MOUD treatment for beneficiaries, although geographic gaps in access remain.

The prevalence of opioid use disorder (OUD) and opioid overdose deaths is rising rapidly among the nation’s 64.9 million Medicare enrollees,1–3 7.8 million of whom have a qualifying disability.4 In 2021 an estimated 1.1 million Medicare beneficiaries were diagnosed with OUD—a 15 percent increase from 2019—and more than 50,000 Medicare beneficiaries experienced a fatal or nonfatal opioid overdose.5,6 Medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD)—that is, methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone—especially when provided in conjunction with behavioral therapy, are the effective, evidence-based standard of care for OUD.7–9 However, beneficiaries’ access to MOUD has been limited, as evidenced by low Medicare acceptance among specialty substance use disorder (SUD) treatment facilities and the scarcity of SUD services tailored to older adults.10–14

The specialty SUD treatment system in the US is composed of about 16,000 facilities, including roughly 1,700 opioid treatment programs (OTPs), which are licensed by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to dispense methadone, and 14,000 SUD treatment programs without OTP certification (“non-OTPs”), which cannot dispense methadone but may offer one or both of the two other MOUD approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In contrast to methadone, which is a full opioid agonist and Schedule II narcotic, buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist (Schedule III), and naltrexone is an opioid antagonist (that is, not a controlled substance). Importantly, buprenorphine and naltrexone are not subject to as high a degree of federal and state regulation as methadone, which means that US patients with OUD often encounter fewer barriers to access to them.15

A particular issue for Medicare beneficiaries with OUD has been the lack of Medicare coverage of methadone. Before 2020, Medicare did not cover treatment of OUD with methadone, despite the fact that methadone is a well-established treatment for OUD and is the optimal treatment for many patients.16 Furthermore, the increasing prevalence of illicit fentanyl, which is a highly potent opioid, makes access to methadone all the more critical; emerging evidence suggests that methadone is less likely than buprenorphine to precipitate withdrawal during treatment induction among fentanyl users.17

To address the Medicare OUD treatment coverage gap, services provided in OTPs were added as a Medicare benefit beginning January 1, 2020, under the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities (SUPPORT) Act, which became law in 2018. A weekly Medicare OTP bundled fee includes dispensing or administration of methadone (or another FDA-approved MOUD), substance use counseling, individual and group therapy, and toxicology testing. This is the first study to document geographic variation in the availability of OTPs that accept Medicare after the OTP Medicare benefit was implemented.

Study Data And Methods

DATA

We used data from the 2022 edition of the National Directory of Drug and Alcohol Abuse Treatment Facilities to examine county-level factors associated with OTP acceptance of Medicare insurance. The 2022 directory represents data from the 2021 National Substance Use and Mental Health Services Survey conducted by SAMHSA.18 Our key outcome variable was a dichotomous measure that took a value of 1 if a county had at least one OTP that offered methadone maintenance treatment and accepted Medicare in 2021, and 0 otherwise. To compare the MOUD landscape for Medicare beneficiaries after the 2020 implementation of the OTP benefit with the availability of MOUD before the implementation of the benefit, we created a dichotomous variable measuring whether a county had a non-OTP that accepted Medicare and offered buprenorphine or naltrexone in 2019, using data from the 2020 directory.

County-level variables from the Medicare Geographic Variation file included the percentage of Medicare fee-for-service, dual-eligible (both Medicare and Medicaid), and female beneficiaries; average beneficiary age; and average Hierarchical Condition Categories risk score, which assigns a numeric value to overall beneficiary health (with higher values indicating worse health). Variables from the Census Bureau included the racial and ethnic composition of counties’ population ages sixty-five and older and the percentage of counties’ population in rural areas, in poverty, and uninsured. The Area Health Resources File provided the percentage of county labor-force participation. We created dichotomous variables for census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West). We also controlled for county prevalence of illicit drug use (other than marijuana) in the past month from the SAMHSA National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2018–20 substate estimates. Finally, we included the state average (2018–20) age-adjusted opioid overdose death rate among people ages fifty-five and older from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER) database.

ANALYSIS

We calculated descriptive statistics for all study variables. We mapped county-level access to an OTP that accepted Medicare in 2021. We also mapped county-level access to MOUD in non-OTPs for Medicare beneficiaries in 2019 (before the implementation of the OTP benefit) and compared it with overall access to facilities (OTP and non-OTP) offering MOUD in 2021 (after the implementation of the benefit). Finally, we fit a multivariable logistic regression model that examined whether a county had an OTP that accepted Medicare in 2021, adjusting for the county-level characteristics reported above. Because of missing values for several control variables, 159 counties were not included in the regression model, leaving us with a study sample of 2,983 counties. Data were analyzed using Stata, version 17.0.

LIMITATIONS

Our study had several limitations. First, the directory data are self-reported by treatment facilities; we did not observe whether facilities provided services to Medicare beneficiaries. Similarly, Medicare beneficiary characteristics and health outcomes associated with service use were not included in this data set. In addition, counties might not accurately reflect a provider’s service area. Finally, our focus was the specialty SUD treatment system; we did not observe buprenorphine or naltrexone providers in other settings.

Study Results

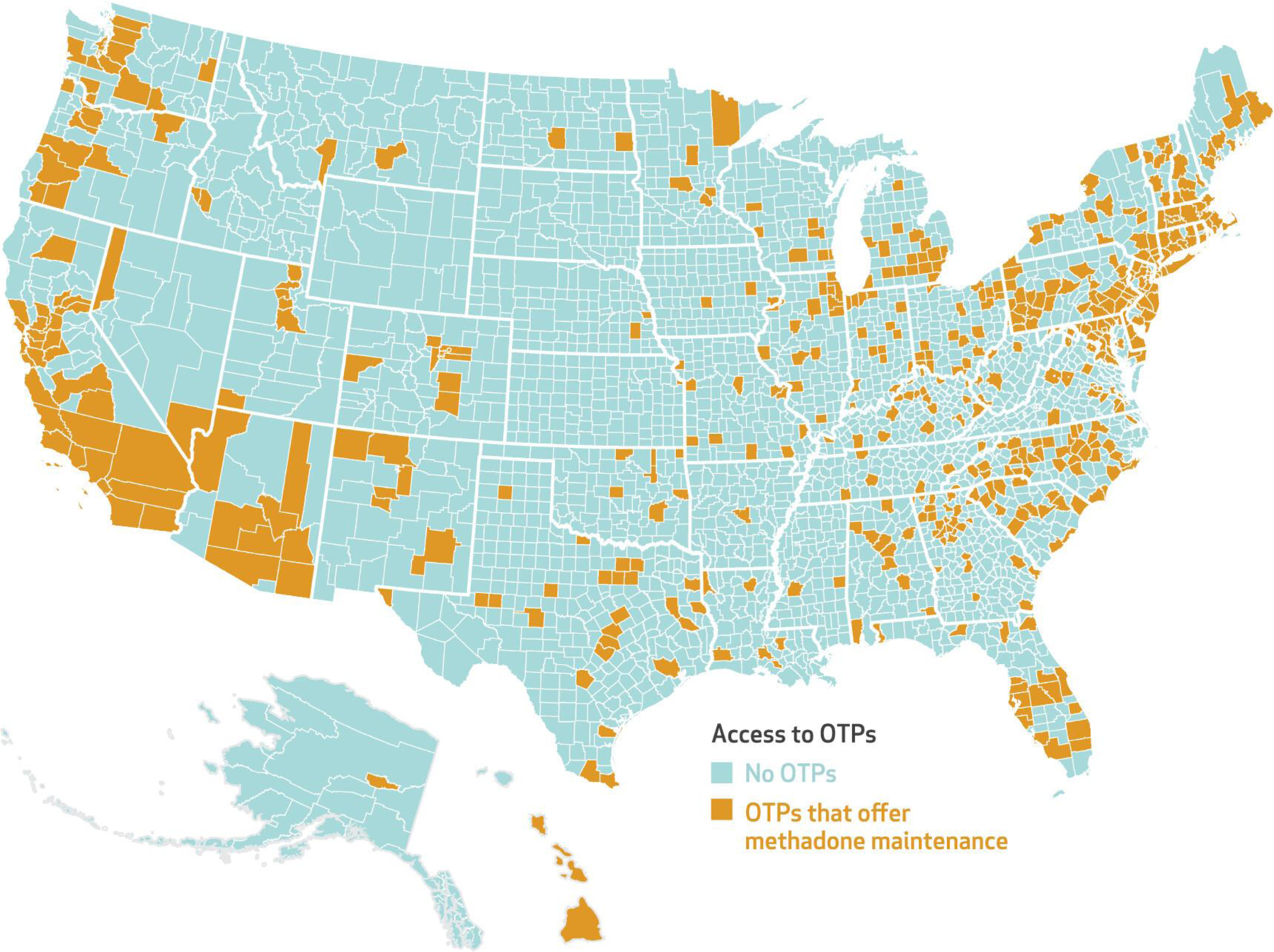

After the implementation of the new OTP benefit, 513 (16.3 percent) counties, home to 36.4 million Medicare beneficiaries, had an OTP that accepted Medicare in 2021 (exhibit 1). However, approximately 21.6 million beneficiaries lived in a county without an OTP that accepted Medicare in 2021 (data not shown). In 124 counties, home to 3.5 million beneficiaries, the OTP was the only treatment facility offering any form of MOUD and accepting Medicare. Analyses also identified seventy-seven counties with an OTP that did not accept Medicare (data not shown). OTPs may decide not to accept Medicare for a number of reasons, including the administrative burden of applying to become a certified Medicare provider and processing claims or an unwillingness to accept the Medicare reimbursement rate for services. They may also, correctly or incorrectly, perceive insufficient demand among the local Medicare population. If an existing OTP in these counties had begun accepting Medicare after the implementation of the new benefit, an additional three million beneficiaries would have gained access to methadone.

EXHIBIT 1.

County-level access to opioid treatment programs (OTPs) in the US that accept Medicare, 2021

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of 2021 data from the National Directory of Drug and Alcohol Abuse Treatment Facilities (2022 edition).

NOTE The map shows county-level access to an OTP that accepted Medicare in 2021 and offered methadone maintenance treatment.

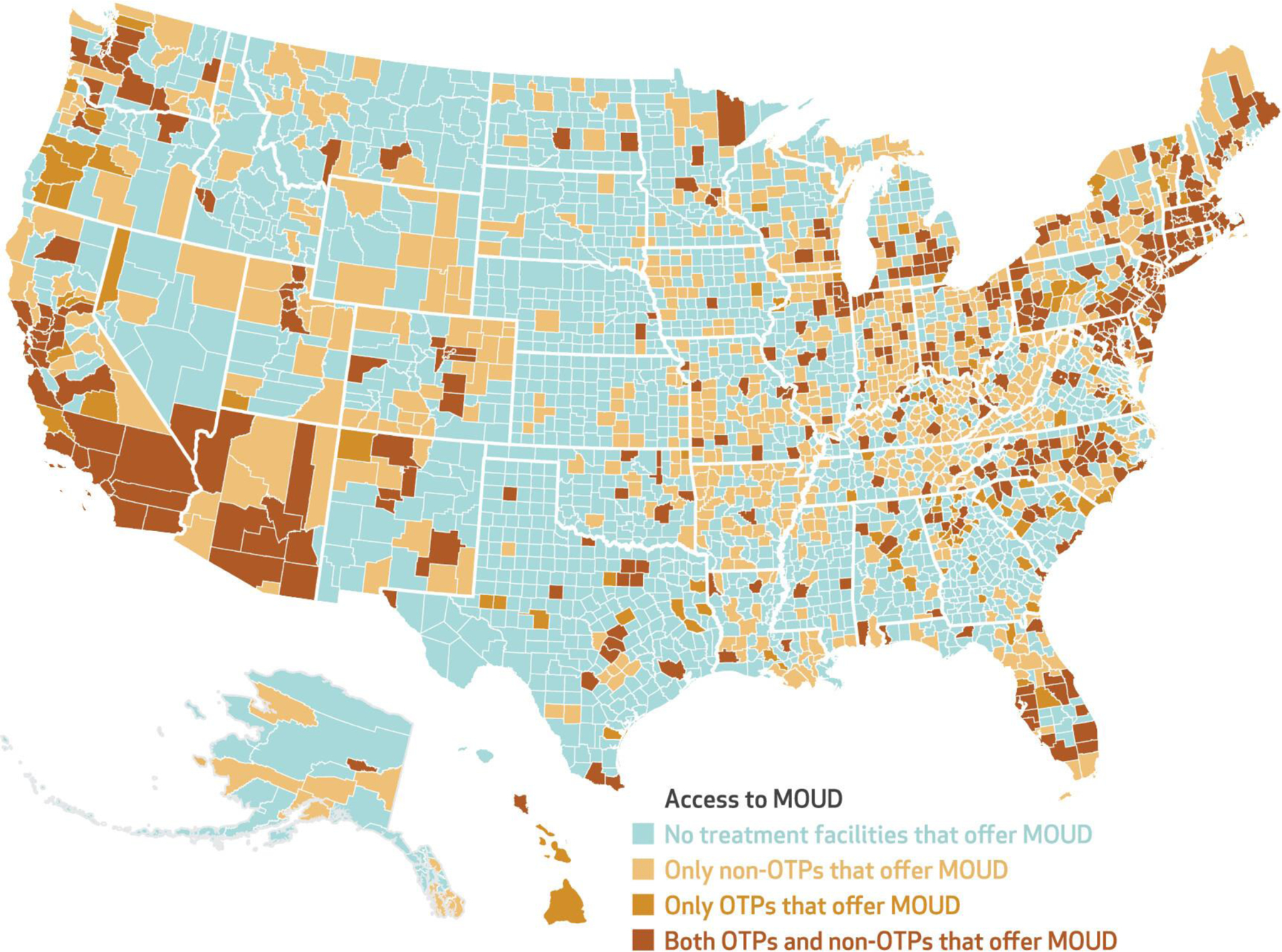

Turning to overall access to MOUD, in 2019, before the new Medicare OTP benefit, 1,031 counties (32.8 percent of all US counties) had at least one non-OTP that reported accepting Medicare and offering buprenorphine or naltrexone. The distribution of these facilities is shown in a map in online appendix exhibit 1.19 By 2021, 1,169 counties (37.2 percent) had a non-OTP that accepted Medicare and offered buprenorphine or naltrexone (exhibit 2). In addition, overall access to MOUD increased to 1,293 counties (41.2 percent of counties) that had access to a treatment facility accepting Medicare and offering some form of MOUD—an OTP offering methadone maintenance treatment or a non-OTP offering buprenorphine or naltrexone. However, 1,849 counties (58.8 percent) had no specialty SUD treatment program offering any form of MOUD and accepting Medicare in 2021, leaving approximately 10.41 million beneficiaries with no within-county access to MOUD. Additional descriptive statistics are in the appendix.19

EXHIBIT 2.

County-level access to medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) for Medicare beneficiaries in opioid treatment programs (OTPs) and non-OTP specialty substance use treatment facilities in the US, 2021

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of 2021 data from the National Directory of Drug and Alcohol Abuse Treatment Facilities (2022 edition).

NOTE The map shows county-level access to an OTP that accepted Medicare and offered methadone maintenance treatment, a non-OTP that accepted Medicare and offered buprenorphine or naltrexone, or both in 2021.

In our multivariable logistic regression model, counties with higher proportions of rural residents were less likely to have an OTP that accepted Medicare than counties with lower proportions of rural residents (odds ratio: 0.96; exhibit 3), and counties located in the Midwest (OR: 0.15), South (OR: 0.26), and West (OR: 0.42) were less likely to have such an OTP than counties in the Northeast. Counties with a non-OTP that accepted Medicare and offered buprenorphine or naltrexone in 2019 (before the OTP benefit) were more likely to have an OTP that accepted Medicare in 2021 (OR: 2.72), as were counties with higher opioid mortality among adults ages fifty-five and older (OR: 1.09). Full adjusted multivariable regression model results are in the appendix.19

EXHIBIT 3.

Odds of a county having at least one opioid treatment program (OTP) that accepted Medicare in 2021, by region and selected characteristics, United States

| Characteristics | Odds ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Region (ref: Northeast) | ||

| Midwest | 0.15**** | 0.09, 0.23 |

| South | 0.26**** | 0.16, 0.43 |

| West | 0.42**** | 0.23, 0.75 |

| Percent rural population | 0.96**** | 0.95, 0.97 |

| Age-adjusted opioid overdose death rate, ages 55+, 2018–20 | 1.09**** | 1.06, 1.13 |

| County had at least one non-OTP that accepted Medicare and offered buprenorphine or naltrexone, 2019 | 2.72**** | 2.07, 3.57 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the National Directory of Drug and Alcohol Abuse Treatment Facilities, 2022 and 2020 editions (representing survey responses from 2021 and 2019). Models are adjusted for county characteristics, using data from the Medicare Geographic Variation File, the Census Bureau, the Area Health Resources File, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER) database, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NOTES The exhibit presents odds ratios from logistic regression analysis results estimating factors associated with a county having at least one OTP that accepted Medicare. The reference group for the binary county variable is its complement. For the continuous variables, probabilities change in the same direction as the variable for an odds ratio greater than 1.00 and in the opposite direction for an odds ratio less than 1.00. Models include 2,983 county observations and control for county population and Medicare population characteristics, including the percentages of the White population older than age 65, percent uninsured, percent in poverty, percent in the labor force, and estimates of illicit drug use other than marijuana in the past month among the county population ages 12 and older.

p < 0.001

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that the Medicare OTP benefit improved the overall availability of MOUD for Medicare beneficiaries. In fact, 6.9 million beneficiaries gained new access to an OTP or non-OTP that accepted Medicare and offered MOUD between 2019 and 2021. However, in 2021 approximately 21.6 million Medicare beneficiaries lived in a county without an OTP that accepted Medicare, and 10.4 million beneficiaries lived in a county without any access to MOUD in a specialty SUD treatment facility (OTP or non-OTP; data not shown).

In most cases, the availability of OTP services for Medicare beneficiaries represented an expansion of therapeutic options among forms of MOUD (in addition to buprenorphine or naltrexone), rather than an introduction of new MOUD access in a county that previously lacked it. About 74 percent of counties with an OTP that accepted Medicare in 2021 already had non-OTP access to buprenorphine or naltrexone in 2019 (data not shown). In addition, regression results show that the odds of a county having an OTP that accepted Medicare in 2021 were 2.72 times higher in counties that already had at least one non-OTP that offered buprenorphine or naltrexone and accepted Medicare in 2019. Although promising, these findings highlight persistent geographic disparities in access to MOUD for Medicare beneficiaries.10,20

Our regression results are also consistent with those of prior research showing urban-rural and regional differences in access to MOUD.10,20–23 In particular, the odds of a county having an OTP that accepted Medicare were lower for counties with higher percentages of residents in rural areas and for counties located in the West, Midwest, and South compared with the Northeast. These results are also consistent with a recent report issued by the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General, which found that in 2020, the average percentage of Medicare beneficiaries with OUD receiving MOUD was more than twice as high in the Northeast (28.8 percent of beneficiaries) compared with other regions (13.4 percent of beneficiaries).24 One strategy to address these geographic disparities in access to methadone is to allow dispensing of methadone in pharmacies or federally qualified health centers. In particular, dispensing of methadone in the latter would likely address current rural OUD treatment coverage gaps, as these centers serve as safety-net providers for millions of underinsured and uninsured Americans across 14,000 sites in the US.25

Conclusion

By 2021, most Medicare beneficiaries lived in a county with an OTP that accepted Medicare, but a sizable number still lacked access to medications for OUD, including methadone. The SUPPORT Act’s Medicare OTP benefit marked a pivotal shift in Medicare coverage of OUD treatment. Other recent Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) regulations and federal legislation are also likely to help address remaining OUD treatment barriers for Medicare beneficiaries. For example, in January 2021 CMS expanded the OTP Medicare benefit to include coverage for hospital outpatient OTP services. In addition, the calendar year 2023 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule final rule upheld some pandemic emergency orders, such as flexible take-home dosing and mobile methadone coverage in Medicare, and importantly, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 removed the buprenorphine X-waiver requirement, which set patient limits on buprenorphine prescribing and required mandatory training for prescribers.26 Although these developments are promising, continued Medicare reform and innovations are needed to ensure access to SUD treatment for Medicare beneficiaries. ▪

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Samantha J. Harris, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

Courtney R. Yarbrough, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia.

Amanda J. Abraham, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia.

NOTES

- 1.Parish WJ, Mark TL, Weber EM, Steinberg DG. Substance use disorders among Medicare beneficiaries: prevalence, mental and physical comorbidities, and treatment barriers. Am J Prev Med 2022;63(2):225–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shoff C, Yang TC, Shaw BA. Trends in opioid use disorder among older adults: analyzing Medicare data, 2013–2018. Am J Prev Med 2021; 60(6):850–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuerbis A Substance use among older adults: an update on prevalence, etiology, assessment, and intervention. Gerontology. 2020; 66(3):249–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare monthly enrollment [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2023. Jan [last updated 2023 Apr 25; cited 2023 May 2]. Available from: https://data.cms.gov/summary-statistics-on-beneficiaryenrollment/medicare-and-medicaid-reports/medicare-monthly-enrollment [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Opioid use in Medicare Part D continued to decline in 2019, but vigilance is needed as COVID-19 raises new concerns [Internet]. Washington (DC): HHS; 2020. Aug [cited 2023 May 2]. (Data Brief No. OEI-02-20-00320). Available from: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/OEI-02-20-00320.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Opioid overdoses and the limited treatment of opioid use disorder continue to be concerns for Medicare beneficiaries [Internet]. Washington (DC): HHS; 2022. Sep [cited 2023 Jun 5]. (Data Brief No. OEI-02-22-00390). Available from: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/OEI-02-22-00390.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mattick RP, Kimber J, Breen C, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; (3):CD002207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krupitsky E, Nunes EV, Ling W, Illeperuma A, Gastfriend DR, Silverman BL. Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence. Lancet. 2011;378(9792): 665, author reply 666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amato L, Minozzi S, Davoli M, Vecchi S. Psychosocial combined with agonist maintenance treatments versus agonist maintenance treatments alone for treatment of opioid dependence. Cochrane Data-base Syst Rev 2011;(10):CD004147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris SJ, Abraham AJ, Andrews CM, Yarbrough CR. Gaps in access to opioid use disorder treatment for Medicare beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(2):233–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantor JH, DeYoreo M, Hanson R, Kofner A, Kravitz D, Salas A, et al. Patterns in geographic distribution of substance use disorder treatment facilities in the US and accepted forms of payment from 2010 to 2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11): e2241128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Concerns persist about opioid overdoses and Medicare beneficiaries’ access to treatment and overdose-reversal drugs [Internet]. Washington (DC): HHS; 2021. Aug [cited 2023 May 2]. (Data Brief No. OEI-02-20-00401). Available from: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/OEI-02-20-00401.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi NG, DiNitto DM. Characteristics of mental health and substance use service facilities for older adults: findings from US national surveys. Clin Gerontol 2022;45(2):338–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinberg D, Weber E, Woodworth A. Medicare’s discriminatory coverage policies for substance use disorders. Health Affairs Blog [blog on the Internet]. 2021. Jun 22 [cited 2023 May 2]. Available from: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20210616.166523/ [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abraham AJ, Andrews CM, Harris SJ, Friedmann PD. Availability of medications for the treatment of alcohol and opioid use disorder in the USA. Neurotherapeutics. 2020; 17(1):55–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, Indave BI, Degenhardt L, Wiessing L, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ 2017;357:j1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varshneya NB, Thakrar AP, Hobelmann JG, Dunn KE, Huhn AS. Evidence of buprenorphine-precipitated withdrawal in persons who use fentanyl. J Addict Med 2022;16(4):e265–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The National Substance Use and Mental Health Services Survey replaced the National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services in 2021 (combining it with the National Mental Health Services Survey) and is conducted annually by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- 19.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abraham AJ, Adams GB, Bradford AC, Bradford WD. County-level access to opioid use disorder medications in Medicare Part D (2010–2015). Health Serv Res 2019;54(2): 390–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jehan S, Zahnd WE, Wooten NR, Seay KD. Geographic variation in availability of opioid treatment programs across U.S. communities. J Addict Dis 2023;1–11. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stein BD, Pacula RL, Gordon AJ, Burns RM, Leslie DL, Sorbero MJ, et al. Where is buprenorphine dispensed to treat opioid use disorders? The role of private offices, opioid treatment programs, and substance abuse treatment facilities in urban and rural counties. Milbank Q 2015;93(3):561–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abraham AJ, Andrews CM, Yingling ME, Shannon J. Geographic disparities in availability of opioid use disorder treatment for Medicaid enrollees. Health Serv Res 2018;53(1): 389–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Many Medicare beneficiaries are not receiving medication to treat their opioid use disorder [Internet]. Washington (DC): HHS; 2021. Dec [cited 2023 Jun 5]. (Data Brief No. OEI-02-20-00390). Available from: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/OEI-02-20-00390.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 25.Health Resources and Services Administration. Health Center Program: impact and growth [Internet]. Rockville (MD): HRSA; 2022. Aug [cited 2023 May 2]. Available from: https://bphc.hrsa.gov/about-health-centers/health-center-program-impact-growth [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Calendar year (CY 2023) Physician Fee Schedule final rule [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2022. Nov 1 [cited 2023 May 2]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2023-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-final-rule [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.