Abstract

Background

The vulnerability of buffalo sperm to cryoinjury necessitates the improvement of sperm cryo‐resistance as a critical strategy for the widespread use of assisted reproductive technologies in buffalo.

Objectives

The main aim of the present study was to evaluate the effects of different concentrations of rutin and chlorogenic acid (CGA) on buffalo semen quality, antioxidant activity and fertility during cryopreservation.

Methods

The semen was collected and pooled from the 3 buffaloes using an artificial vagina (18 ejaculations). The pooled sperm were divided into nine different groups: control (Tris‐based extender); 0.4, 0.6, 0.8 and 1 mM rutin (rutin + Tris‐based extender); and 50, 100, 150 and 200 µM CGG (CGA + Tris‐based extender). Sperm kinematics, viability, hypo‐osmotic swelling test, mitochondrial activity, antioxidant activities and malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration of frozen and thawed buffalo sperm were evaluated. In addition, 48 buffalo were finally inseminated, and pregnancy was rectally determined 1 month after insemination.

Results

Compared to the control group, adding R‐0.4, R‐0.6, CGA‐100 and CGA‐150 can improve total and progressive motility, motility characteristics, viability, PMF and DNA damage in buffalo sperm. In addition, the results showed that R‐0.4, R‐0.6, CGA‐50, CGA‐100 and CGA‐150 increased total antioxidant capacity, catalase, glutathione peroxidase and glutathione activities and decreased MDA levels compared to the control group. Furthermore, it has been shown that adding 150 µM CGA and 0.6 mM rutin to an extender can increase in vivo fertility compared to the control group.

Conclusions

In conclusion, adding rutin and CGA to the extender improves membrane stability and in vivo fertility of buffalo sperm by reducing oxidative stress.

Keywords: chlorogenic acid, rutin, sperm cryo‐resistance, thawed buffalo sperm

Adding rutin and chlorogenic acid to semen extender enhances sperm motility, improves PMF, reduces sperm viability damage and boosts sperm antioxidant capacity. Thus, their inclusion can enhance the quality of frozen and thawed buffalo semen. This research also indicates that rutin and chlorogenic acid may be beneficial in enhancing in vivo fertility.

1. INTRODUCTION

The Azari ecotype is characterized by its tiny size, black skin and notable attributes like a high‐quality milk production rate, elevated fat content and extended milking time each year (pour Azary et al., 2004; Borghese & Mazzi, 2005). The widespread use of artificial insemination (AI) technology has significantly increased the consumption rate of buffalo semen. AI and cryopreservation of sperm are crucial in conserving buffalo genetic resources within this particular livestock species (Ramazani et al., 2023a). Additionally, the cryopreservation of gametes in the banking system provides a reliable and effective means of protecting biodiversity and endangered species. Cryopreservation, which involves storing sperm in liquid nitrogen at an extremely low temperature of −196°C, can preserve sperm. According to Li et al. (2023), this phenomenon extends the lifespan of the cells. AI may be conducted with prolonged or frozen‐thawed semen. Cryogenic damage can result from various factors, including osmotic stress, cold shock, intracellular ice crystal formation, excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and alterations in antioxidant defence mechanisms. As part of regular physiological processes, ROS and antioxidant enzymes are produced harmoniously. However, excessive ROS formation coupled with a decrease in the activity of antioxidant defence mechanisms leads to reduced sperm motility and viability, DNA damage and protein denaturation (Archana et al., 2023).

Buffalo sperm are prone to membrane damage, which may be due to the increased content of long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in the sperm membrane. This high concentration makes the membrane more sensitive to lipid peroxidation (LPO) when ROS are present (Yuan et al., 2023). Buffalo semen is known to have several antioxidant systems that can lower ROS levels and mitigate internal cellular damage (Gao et al., 2017; Luo et al., 2023; Turaja et al., 2019). However, the cryopreservation process poses a challenge as semen has low levels of these antioxidants, leaving the endogenous defence system unable to combat this stress (Ansari et al., 2012). So, it is essential to have an outside, robust antioxidant system to stop or lessen the effects of LPO and boost sperm function, which keeps fertility at its best (Izanloo et al., 2021, 2022; Ramazani et al., 2023b; Sheikholeslami et al., 2020; Soleimanzadeh et al., 2020; Soleimanzadeh & Saberivand, 2013; Soleimanzadeh et al., 2014). Numerous studies have investigated the influence of different extenders on the cryopreservation of buffalo semen to improve the quality of buffalo semen during storage. However, it has been found that results vary depending on the specific type and concentration of antioxidants used (Dorostkar et al., 2012; Iqbal et al., 2016; Kumaresan et al., 2006; Luo et al., 2023; Mostafa et al., 2019; Swami et al., 2017).

Rutin, a flavonoid glycoside often referred to as vitamin P or purple quercetin, is derived from several natural sources, including Ruta graveolens, tobacco, jujube, apricot, orange, tomato and buckwheat. Several scientific studies have shown evidence of the antioxidant activity and anti‐inflammatory effects of rutin (Cândido et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2018). The effectiveness of rutin in removing ROS directly by donating electrons to free radicals has been shown in other studies (Ghiasi et al., 2012). According to recent studies by Jamalan et al. (2016) and Mehfooz et al. (2018), there is evidence that rutin may have a potentially protective effect on male reproductive function both in vivo and in vitro; according to the findings of Xu et al. (2020), the addition of rutin to the cryopreservation extender enhances the antioxidant defence mechanism and protects boar sperm from ROS attack. In another study by Najafi et al. (2023), rutin could improve epididymal sperm quality in sheep after the cryopreservation procedure.

Chlorogenic acid (CGA) is a phenolic acid compound abundant in many food sources, such as coffee and tea (Meng et al., 2013; Venditti et al., 2015). CGA has been shown to have remarkable biological properties, such as its ability to act as an antioxidant (Mussatto et al., 2011), exert anti‐inflammatory effects (Guo et al., 2015) and exhibit anti‐tumour effects (Granado‐Serrano et al., 2007). Castro et al. (2018) discovered that CGA could scavenge free radicals and inhibit the progression of oxidative reactions in vitro. Previous research has shown that incorporating 4.5 mg/mL CGA into boar semen can improve the quality of insemination doses, particularly for storage periods exceeding 24 hr (Pereira et al., 2014). In a study by Namula et al. (2018), it was shown that adding 100 µM CGA during the process of freezing boar semen resulted in a significant improvement in various sperm properties, including motility, viability and plasma membrane functionality (PMF).

However, a thorough review of the existing literature has shown that the influence of rutin and CGA on buffalo sperm has not yet been investigated in vivo or in vitro. Therefore, the main aim of this research was to examine the influence of rutin and CGA on maintaining the quality of buffalo sperm after cryopreservation when used as supplements in the Tris‐based extender.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Collection and processing of the semen

All animals used in this study were healthy and housed under identical conditions. The artificial vagina technique was used to collect sperm twice a week. Three Iranian water buffalo bulls (Bubalus bubalis) with 7 weeks of proven fertility produced 18 ejaculations. Only semen samples subjected to a quality assessment that satisfied specific requirements were used for the research. Specimens with a concentration of more than 500 × 106 cells/mL, a volume between 2 and 6 mL, total motility of more than 65% and abnormal morphology of less than 20% per ejaculation were considered normal and included in the study. The animals involved in the study were well cared for, and they received the same treatment. The regulations of the Animal Ethics Committee carried out the study Islamic Azad University, Iran.

Merck and Sigma supplied all necessary chemicals. The present study used a typical Tris‐based extender as the base extender for semen dilution (Ramazani et al., 2023a). Semen samples (n = 3) from each replication were pooled, divided into nine parts and diluted to a final concentration of 15 × 106 spermatozoa/mL (Soleimanzadeh, Talavi et al., 2020) with one of the following extenders. The extender was used as a control group (C). In addition to the control group, eight additional groups were formed by incorporating different concentrations of antioxidants into the extender. Rutin (Xu et al., 2020) and CGA (Namula et al., 2018) were added to the Tris‐Base extender at concentrations of 0.4, 0.6, 0.8 and 1 mM (R‐0.4, R‐0.6, R‐0.8 and R‐1) and 50, 100, 150 and 200 µM (CGA‐50, CGA‐100, CGA‐150 and CGA‐200), respectively. The frozen samples were defrosted after 1 week and then prepared for analysis by thawing at 38°C in a water bath (Soleimanzadeh, Talavi et al., 2020).

2.2. Semen analysis

2.2.1. Motility and motion parameters

Researchers can gain important information about the quality of the semen sample and its potential impact on male fertility by using a computer‐assisted semen analysis (CASA) system to assess semen motility characteristics. A CASA (Test Sperm 3.2; video test) system was used to determine sperm motility parameters. Some motility parameters were measured using the system. These were total motility, progressive motility, curvilinear velocity (VCL), straight‐line velocity (VSL), average path velocity (VAP), straightness, linearity (LIN), amplitude of lateral head displacement and beat‐cross frequency (BCF). Each analysis required 10 µL of thawed sperm, and a minimum of 500 sperm were examined in 5 microscopic areas (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Parameter settings for the computer‐assisted semen analysis (CASA).

| Parameter | Setting |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Slide‐coverslip (22 × 22 mm2) |

| Volume per slide |

|

| Chamber depth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

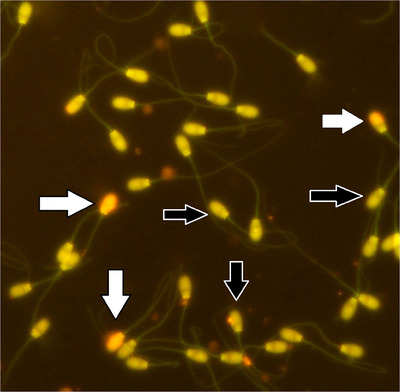

2.2.2. DNA damage evaluation

A low pH technique called acridine orange (AO) staining was used to check for DNA damage and find broken double‐stranded DNA segments in sperm chromatin (Narayana et al., 2002). The semen sample was formed into a thick swab, which was then fixed in Carnoy's fixative (a 1:3 mixture of methanol and acetic acid) for 2 h. The smear was then extracted and air‐dried for 5 min at room temperature. The smear was then incubated for 5 min at 4°C in the dark with a stock solution of 1 mg AO and 1000 mL of distilled water (Soleimanzadeh, Kian et al., 2020). Sperm were examined with a fluorescence microscope (Model GS7, Nikon Co.). Yellow or red fluorescent sperm were considered damaged and aberrant, suggesting possible DNA fragmentation.

2.2.3. Sperm plasma membrane functionality

The hypo‐osmotic swelling test is a helpful tool for assessing the function of the sperm membrane. For this test, a small amount of semen is diluted in a hypo‐osmotic solution containing fructose and sodium citrate and then incubated at 37°C. The plasma membrane of the sperm is evaluated after incubation with a contrast phase microscope (Olympus, BX41) at 400× magnification. The percentage of sperm with intact membranes is often calculated by counting 200 straight or curled sperm (Khan & Ijaz, 2007; Ramazani et al., 2023a).

2.2.4. Viability

Eosin–nigrosine staining was used to assess viability, according to a World Health Organization (WHO) (1999). The pigments eosin and nigrosine were formed in distilled water. One volume of semen was combined with two volumes of 1 % eosin, and the combination was then examined at 400× magnification with a light microscope (Olympus, BX41). Viable sperm remain colourless, but non‐viable sperm turn red due to eosin staining (Ramazani et al., 2023a).

2.3. Assessment of enzymatic antioxidant activity

Six straws were used for the biochemical examination of semen, one for each extender. Thawed sperm of 120 µL was taken and centrifuged at 1600 × g and 25°C for 5 min. To extract the sperm enzymes, the supernatant was removed and then treated with 360 µL of 1% Triton X‐100. The mixture was subjected to precipitation for 20 min before being centrifuged at 4000 × g for 30 min at 25°C (Ramazani et al., 2023b).

The levels of total antioxidant capacity (TAC), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione (GSH) and malondialdehyde (MDA) in semen samples were analysed using kits from Navand Salamat Company. The TAC levels were reported in mmol/L, whereas the GPx levels were in mU/mL. On the other hand, the SOD, CAT and GSH activities in the seminal plasma were expressed in U/mL, the GPx activity was given in mU/mL and the MDA values were shown in nmol/mL (Ramazani et al., 2023b). For 2,2‐diphenyl‐1‐picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging evaluation, in a cuvette that held 970 mL of mixed methanol, 5 mL (10 mM) of DPPH radicals were added. The absorbance at 517 nm (A517) was measured after incubating this mixture at 20°C for 3 min. After adding and mixing 25 mL of each sample and 25 mL of a 9.50 M acetonitrile solution as a negative control, the mixture was incubated at 20°C for 3 min. It was then determined how much the A517 value had fallen as a result of the breakdown of the DPPH radicals (Chrzczanowicz et al., 2008).

2.4. Fertility rate following artificial insemination

We conducted a fertility study in vivo on a selected group of 48 adult wheeled buffalo aged 5–8 years with no known reproductive issues, similar nutrition (Table 2) and body condition scores of 2–3 (Escalante et al., 2013). To compare fertility based on post‐thaw results, we divided the buffalo into three groups: the control group, the CGA‐150 (150 µM CGA) group and the R‐0.6 (0.6 mM rutin) group (best groups). After an experienced inseminator performed inseminations, each buffalo underwent inseminations by an inseminator, and a rectal pregnancy diagnosis was made at least 60 days after insemination (Ramazani et al., 2023a).

TABLE 2.

Composition of concentrate mixtures fed to adult wheeled buffalo.

| Ingredients | Lactating cows (kg) |

|---|---|

| Corn | 470.00 |

| Soybean meal | 150.00 |

| Full‐fat soy flour | 80.00 |

| Fish meal | 50.00 |

| Bran | 120.00 |

| Calcium carbonate | 12.00 |

| Dicalcium phosphate | 4.00 |

| Molasses | 40.00 |

| Salt | 8.00 |

| Saponification of fat powder | 50.00 |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 13.00 |

| Vitamins a | 1.00 |

| Minerals b | 2.00 |

| Total | 1000.00 |

Vitamin premix formula: vitamin A, 16,000,000 IU; vitamin D3, 6,000,000 IU; and vitamin E, 100,000 mg.

Mineral premix formula (per kg): ferrous sulphate, 60.00 g; manganese sulphate, 50.00 g; copper sulphate, 12.50 g; sodium selenite, 0.40 g; zinc sulphate, 50.00 g; and cobalt carbonate, 0.15 g.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Study data were analysed using SPSS software (version 26.0, IBM). A one‐way analysis of variance was performed to determine if there were significant differences between the groups studied. Tukey's post hoc test was then used to determine which groups were significantly different from each other. A p‐value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Motility of the sperm and movement features

Based on the results presented in Table 3, it appears that groups R‐0.4, R‐0.6, R‐1, CGA‐50, CGA‐100 and CGA‐150 in terms of sperm total and progressive motility provide better outcomes compared to the control group (p ≤ 0.05; Table 3). CASA evaluated these factors after the freezing process. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in the R‐0.8 and CGA‐200 groups compared to the control group (p > 0.05; Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Effects of different concentrations of rutin (R) and chlorogenic acid (CGA) on buffalo sperm total and progressive at the post‐thaw stage of cryopreservation.

| Analysis | Control | R‐0.4 | R‐0.6 | R‐0.8 | R‐1 | CGA‐50 | CGA‐100 | CGA‐150 | CGA‐200 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total motility (%) | 54.03 ± 1.54fg | 61.05 ± 1.20cd | 65.18 ± 1.36ab | 57.32 ± 1.42ef | 59.03 ± 1.19de | 61.49 ± 1.73cd | 64.59 ± 1.51bc | 68.24 ± 1.14a | 53.72 ± 1.30g |

| Progressive motility (%) | 22.19 ± 1.40f | 30.82 ± 1.89cd | 34.03 ± 1.65ab | 25.92 ± 1.15ef | 27.45 ± 1.37de | 30.35 ± 1.63cd | 33.54 ± 1.90bc | 37.89 ± 1.78a | 23.45 ± 1.20f |

Note: Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. R‐0.4: Tris‐based extender + rutin (0.4 mM); R‐0.6: Tris‐based extender + rutin (0.6 mM); R‐0.8: Tris‐based extender + rutin (0.8 mM); R‐1: Tris‐based extender + rutin (1 mM); CGA‐50: Tris‐based extender + chlorogenic acid (50 µM); CGA‐100: Tris‐based extender + chlorogenic acid (100 µM); CGA‐150: Tris‐based extender + chlorogenic acid (150 µM); CGA‐200: Tris‐based extender + chlorogenic acid (200 µM). Different superscripts within the same row demonstrate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05).

Table 4 shows the characteristics of buffalo sperm motility rates. According to Table 4, the groups receiving R‐0.4, R‐0.6, R‐1, CGA‐50, CGA‐100 and CGA‐150 showed increased VAP, LIN and BCF compared to the control group (p ≤ 0.05; Table 4). However, adding R‐0.8 and CGA‐200 to the extender in VAP and LIN and CGA‐200 in BCF had no significant effects compared to the control group (p ≤ 0.05, Table 4). VCL analysis showed that groups R‐0.4, R‐0.6, R‐0.8, R‐1, CGA‐50, CGA‐100 and CGA‐150 had higher values than the control group (p ≤ 0.05, Table 4). In addition, the R‐0.4, R‐0.6, CGA‐50, CGA‐100 and CGA‐150 groups performed better than the control group on VSL analysis (p ≤ 0.05, Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Mean (±SEM) sperm motility characteristics of frozen–thawed buffalo semen after the addition of different concentrations of rutin (R) and chlorogenic acid (CGA) in the semen extender.

| Analysis | Control | R‐0.4 | R‐0.6 | R‐0.8 | R‐1 | CGA‐50 | CGA‐100 | CGA‐150 | CGA‐200 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAP (µm/s) | 21.30 ± 1.32e | 27.74 ± 1.97bcd | 29.45 ± 1.87bc | 23.92 ± 1.81e | 24.01 ± 1.69de | 26.80 ± 1.73cd | 30.15 ± 1.60ab | 33.20 ± 1.36a | 21.40 ± 1.49e |

| VCL (µm/s) | 31.54 ± 1.57e | 39.10 ± 0.48bc | 42.59 ± 1.57b | 34.40 ± 1.65d | 36.47 ± 1.07cde | 40.24 ± 1.20b | 42.27 ± 1.03b | 46.77 ± 1.69a | 32.85 ± 1.70e |

| VSL (µm/s) | 16.08 ± 1.61c | 21.41 ± 1.76b | 25.45 ± 1.80a | 17.09 ± 1.17c | 17.51 ± 1.40c | 20.37 ± 1.48b | 25.13 ± 1.95a | 27.05 ± 1.56a | 15.91 ± 1.27c |

| LIN (%) | 42.19 ± 1.15f | 51.73 ± 1.36c | 54.38 ± 1.39b | 44.72 ± 1.76ef | 47.53 ± 1.28de | 49.78 ± 1.67cd | 56.94 ± 1.12ab | 58.27 ± 1.71a | 42.10 ± 1.33f |

| ALH (µm/s) | 2.47 ± 0.10a | 2.45 ± 0.12a | 2.46 ± 0.11a | 2.45 ± 0.13a | 2.47 ± 0.10a | 2.48 ± 0.14a | 2.48 ± 0.13a | 2.50 ± 0.16a | 2.47 ± 0.14a |

| STR (%) | 72.05 ± 1.32a | 72.39 ± 1.47a | 72.85 ± 1.25a | 73.05 ± 2.30a | 72.40 ± 1.19a | 72.66 ± 1.51a | 72.26 ± 1.50a | 73.19 ± 1.83a | 72.19 ± 1.59a |

| BCF (Hz) | 4.61 ± 0.19e | 5.30 ± 0.16cd | 6.32 ± 0.34b | 4.83 ± 0.15d | 5.07 ± 0.23d | 5.39 ± 0.29cd | 5.82 ± 0.26c | 7.05 ± 0.30a | 4.60 ± 0.24e |

Note: R‐0.4: Tris‐based extender + rutin (0.4 mM); R‐0.6: Tris‐based extender + rutin (0.6 mM); R‐0.8: Tris‐based extender + rutin (0.8 mM); R‐1: Tris‐based extender + rutin (1 mM); CGA‐50: Tris‐based extender + chlorogenic acid (50 µM); CGA‐100: Tris‐based extender + chlorogenic acid (100 µM); CGA‐150: Tris‐based extender + chlorogenic acid (150 µM); CGA‐200: Tris‐based extender + chlorogenic acid (200 µM); VAP: average path velocity; VCL: curvilinear velocity; VSL: straight‐line velocity; LIN: linearity; ALH: amplitude of lateral head displacement; BCF: beat‐cross frequency; STR: straightness. Different superscripts within the same row demonstrate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05).

3.2. Plasma membrane functionality, DNA damage and sperm viability

Table 5 presents the PMF results of cryopreserved buffalo sperm. Compared to the control group, more sperm in the R‐0.4, R‐0.6, CGA‐50, CGA‐100 and CGA‐150 treatment groups had intact plasma membranes (p ≤ 0.05, Figure 1; Table 5). Moreover, Table 5 shows that the DNA integrity of the buffalo sperm was affected by different R and CGA values. Compared to the control group, adding R‐0.4, R‐0.6, R‐1, CGA‐50, CGA‐100 and CGA‐150 improved sperm DNA integrity (p ≤ 0.05, Figure 2; Table 5). In addition, the study found that sperm viability values were highest in the R‐0.4, R‐0.6, CGA‐100 and CGA‐150 groups compared to the control group (p ≤ 0.05, Table 5). However, there were no significant differences in the viability percentage between the R‐0.8, R‐1, CGA‐50 and CGA‐200 groups and the control group (p > 0.05; Figure 3; Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Effect of different concentrations of rutin (R) and chlorogenic acid (CGA) supplementation on DNA damage, viability and plasma membrane functionality (PMF) (mean ± SEM) in frozen–thawed buffalo sperm.

| Analysis | Control | R‐0.4 | R‐0.6 | R‐0.8 | R‐1 | CGA‐50 | CGA‐100 | CGA‐150 | CGA‐200 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viability (%) | 63.30 ± 1.71d | 68.94 ± 1.55bc | 71.05 ± 1.47ab | 64.46 ± 2.53d | 64.05 ± 1.81d | 66.78 ± 1.37cd | 70.93 ± 1.43ab | 73.42 ± 2.10a | 63.91 ± 2.36d |

| DNA damage (%) | 10.84 ± 0.26a | 7.82 ± 0.32d | 6.47 ± 0.29e | 10.41 ± 0.40a | 9.64 ± 0.35b | 8.05 ± 0.31c | 6.79 ± 0.28e | 5.46 ± 0.34f | 10.76 ± 0.41a |

| Sperm plasma membrane functionality (%) | 58.19 ± 1.65c | 64.15 ± 1.08b | 68.51 ± 1.73a | 59.82 ± 1.32c | 62.30 ± 1.83bc | 64.20 ± 1.72b | 67.92 ± 1.57ab | 70.85 ± 1.22a | 59.22 ± 1.74c |

Note: R‐0.4: Tris‐based extender + rutin (0.4 mM); R‐0.6: Tris‐based extender + rutin (0.6 mM); R‐0.8: Tris‐based extender + rutin (0.8 mM); R‐1: Tris‐based extender + rutin (1 mM); CGA‐50: Tris‐based extender + chlorogenic acid (50 µM); CGA‐100: Tris‐based extender + chlorogenic acid (100 µM); CGA‐150: Tris‐based extender + chlorogenic acid (150 µM); CGA‐200: Tris‐based extender + chlorogenic acid (200 µM). Different superscripts within the same row demonstrate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05).

FIGURE 1.

Sperm plasma membrane (PM) functionality. White arrows – buffalo spermatozoa with straight tails (nonfunctional PM); black arrows – buffalo spermatozoa with coiled tails (functional PM) (400×).

FIGURE 2.

Sperm DNA damage. Yellow arrows – normal spermatozoa (green); white arrows – DNA damaged spermatozoa (yellow‐red) (acridine orange, 400×).

FIGURE 3.

Sperm plasma membrane (PM) integrity. Black arrows – viable spermatozoa (colourless); white arrow – dead spermatozoa (red) (eosin/nigrosine, 200×).

3.3. Analysis of antioxidant activities

Figure 4 shows the results for antioxidant activities (TAC, GPx, CAT, GSH, DPPH and MDA) in buffalo spermatozoa treated with different concentrations of R and CGA. The groups supplemented with R‐0.4, R‐0.6, R‐0.8, R‐1, CGA‐50, CGA‐100 and CGA‐150 showed significantly higher levels of TAC, GSH and DPPH scavenger compared to the control group (p ≤ 0.05, Figure 4A–C). At the same time, there was no significant difference between treated with CGA‐200 in TAC and GSH levels and treated with R‐0.8 and CGA‐200 in DPPH scavenger with the control group (p > 0.05; Figure 4A–C). The GPx and CAT activity analyses showed a significant increase in the R‐0.4, R‐0.6, R‐1, CGA‐50, CGA‐100 and CGA‐150 groups compared to the control group (p ≤ 0.05, Figure 4D,E). Notably, the addition of R‐0.8 and CGA‐200 did not affect the GPx and CAT levels compared to the control group (p > 0.05; Figure 4D,E). The superoxide dismutase scores showed no significant differences between the groups (p > 0.05; Figure 4F). MDA analysis revealed that adding R‐0.4, R‐0.6, R‐0.8, R‐1, CGA‐50, CGA‐100 and CGA‐150 decreased MDA levels compared to the control group (p ≤ 0.05, Figure 4G).

FIGURE 4.

(a) Total antioxidant capacity (TAC); (b) glutathione (GSH) activities; (c) 2,2‐diphenyl‐1‐picrylhydrazyl (DPPH); (d) glutathione peroxidase (GPx); (e) catalase (CAT); (f) superoxide dismutase (SOD); (g) lipid peroxidation (MDA) of frozen–thawed buffalo semen after supplementation of different concentrations of rutin (R) and chlorogenic acid (CGA) to the semen extender. Control (c): Tris‐based extender without antioxidant; R‐0.4: Tris‐based extender + rutin (0.4 mM); R‐0.6: Tris‐based extender + rutin (0.6 mM); R‐0.8: Tris‐based extender + rutin (0.8 mM); R‐1: Tris‐based extender + rutin (1 mM); CGA‐50: Tris‐based extender + chlorogenic acid (50 µM); CGA‐100: Tris‐based extender + chlorogenic acid (100 µM); CGA‐150: Tris‐based extender + chlorogenic acid (150 µM); CGA‐200: Tris‐based extender + chlorogenic acid (200 µM). Different superscripts within the same row demonstrate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05; mean ± SEM).

3.4. Analysis of fertility rate

Table 6 provides data on in vivo fertility test results. Regarding fertility, there was no significant difference between the R and CGA groups. However, the 150 µM CGA and 0.6 mM rutin groups had higher conception rates than the control group (p ≤ 0.05; Table 6).

TABLE 6.

comparison of fertility rate of buffalo semen cryopreserved.

| Extender | Inseminations | Pregnancy rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 16 | 68.75 (11/16)b |

| CGA‐150 | 16 | 87.50 (14/16)a |

| R‐0.6 | 16 | 81.25 (13/16)a |

Note: CGA‐150: Tris‐based extender + chlorogenic acid (150 µM); R‐0.6: Tris‐based extender + rutin (0.6 mM); Different superscripts within the same column demonstrate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05).

4. DISCUSSION

Antioxidants are frequently employed to enhance the quality of thawed sperm, as oxidative stress can degrade the quality of frozen sperm. Our research indicates that the use of R and CGA may significantly enhance frozen buffalo semen. Other research on buffalo semen has demonstrated that the addition of various antioxidants to frozen–thawed semen can improve semen quality parameters (Ashabi et al., 2023; Farjami et al., 2023; Jahangiri Asl et al., 2021; Salehi et al., 2023; Soleimanzadeh et al., 2018, 2017; Soleimanzadeh et al., 2020).

Sperm motility is a crucial predictor of fertility, although it is not the sole determinant. Other factors, such as sperm viability and the integrity of mitochondria and cell membranes, also play significant roles (Ahmed et al., 2016). Reduced sperm motility during chilled storage can be attributed to both mitochondrial membrane failure and plasma membrane disruption (Pagl et al., 2006). Numerous studies have demonstrated that adding antioxidants to semen extenders can yield several benefits. These include improved sperm morphology, increased motility, protection of the plasma membrane and a reduction in ROS synthesis in frozen–thawed sperm (Shahzad et al., 2016; Tariq et al., 2015). For instance, caffeic acid, an antioxidant, not only protects against oxidative damage and cold shock but can also enhance sperm motility after thawing (Hu et al., 2010). Our study further supports these findings. Extenders treated with rutin and CGA significantly enhanced post‐thaw sperm kinematic properties, including progressive and total motility. This aligns with a previous study by Aksu et al. (2017), which reported improved rat sperm motility and reduced abnormalities with rutin therapy. Additionally, it has been shown that rutin supplementation positively impacted parameters such as VSL, VCL and VAP in post‐thawed sperm (Xu et al., 2020). Najafi et al. (2023) conducted a study demonstrating that supplementing ram sperm with rutin boosted mitochondrial activity and inhibited apoptosis. Their findings suggest that rutin enhances sperm motility and viability by improving mitochondrial function. Rutin possesses antioxidant properties, which protect cells from oxidative damage caused by ROS. By reducing oxidative stress and supporting mitochondrial health, rutin enhances energy production within sperm cells, ultimately boosting sperm motility. Additionally, a study found that CGA can increase the total motility of boar sperm stored for 72 h (Rabelo et al., 2020). Furthermore, dietary supplements containing arachidic acid or butylated hydroxytoluene have also been shown to increase motility in frozen and thawed buffalo sperm (Ejaz et al., 2014; Ijaz et al., 2009).

Cryopreservation and thawing procedures induce LPO of PUFAs in sperm cell membranes, resulting in ultrastructural changes (Partyka et al., 2012). Excessive production of ROS during freezing and thawing disrupts sperm and seminal plasma antioxidant defences, impacting semen quality and fertilization ability (Peña et al., 2009). The sperm plasma membrane experiences heightened LPO, leading to membrane deterioration and increased permeability. This progressive permeability contributes to the depletion of intracellular antioxidant enzymes, ultimately impairing sperm function (Alvarez & Storey, 1995). Rutin treatment has been shown to reduce ROS formation, enhance viability and improve membrane integrity in sperm (Mata‐Campuzano et al., 2012; Najafi et al., 2023). Similarly, adding CGA to semen extenders improves sperm viability, motility and PMF after thawing (Namula et al., 2018). Our study supplemented the freezing extender with rutin and CGA, resulting in significantly increased sperm viability and PMF. These observations are consistent with a previous survey highlighting rutin's antioxidant activity and positive impact on mitochondrial function (Dudylina et al., 2019). Furthermore, antioxidant supplementation has enhanced post‐thaw viability in buffalo sperm (El‐Sheshtawy et al., 2008). Other studies suggest that royal jelly or green tea extract may also improve sperm viability in buffalo after preservation (Ahmed et al., 2020; Shahzad et al., 2016).

Research has demonstrated that the integrity of sperm chromatin may be compromised due to cryopreservation and thawing procedures (Anzar et al., 2002). Furthermore, the generation of ROS during cryopreservation leads to increased DNA damage (Kadirvel et al., 2009). Our investigation reveals that incorporating rutin and CGA into the semen extender can effectively reduce sperm DNA damage. Similarly, Dorostkar et al. (2012) found that adding sodium selenite to the extender mitigates DNA damage in buffalo sperm. Additionally, Topraggaleh et al. (2014) reported that including cysteine in the extender decreases DNA damage in buffalo sperm. Furthermore, Ejaz et al. (2014) demonstrated that adding arachidic acid to the extender improves the integrity of sperm chromatin in buffalo semen.

Cryopreservation and thawing procedures expose buffalo semen to cold shock and atmospheric oxygen, increasing the risk of LPO. This process damages the structural integrity of sperm membranes due to the heightened production of ROS (Ramazani et al., 2023a). Consequently, antioxidant enzyme activity decreases, and a negative correlation exists between sperm MDA levels, viability, PMF and overall motility. The plasma membrane experiences increased LPO during freezing and thawing, leading to membrane leakage, loss of integrity and depletion of intracellular antioxidant enzymes (Oldenhof et al., 2013). LPO occurs when partially reduced oxygen molecules oxidize membrane lipids (Ramazani et al., 2023b). Studies indicate that rutin enhances antioxidant capacity by activating CAT, GPx and superoxide dismutase in rat brain cells (Annapurna et al., 2013). Similarly, rutin improves antioxidant defences in cryopreserved boar semen, protecting against ROS attack (Xu et al., 2020). Khan et al. (2017) explored rutin's effects on sperm damage induced by ROS or LPO in rats. Our research supports the antioxidant benefits of R and CGA, as evidenced by increased TAC and reduced MDA levels. R and CGA enhance TAC, GPx, reduced GPx and CAT levels in buffalo semen after cryopreservation. Notably, R and CGA inhibit protein dephosphorylation during cryopreservation (Fu et al., 2018). Although antioxidants safeguard sperm during freezing, excessive doses may reduce effectiveness due to hypertonic extenders (Bucak et al., 2007). Additionally, taurine supplementation significantly enhances antioxidant levels in post‐preserved buffalo sperm (Reddy et al., 2010).

Research has revealed that alterations and damage can impact sperm fertility without necessarily affecting sperm motility. This suggests that sperm fertility may decline before other factors, such as motility, viability and sperm membrane functionality, exhibit noticeable changes (Chatterjee et al., 2001; Reddy et al., 2010). In a study by Xu et al. (2020), the addition of rutin to the boar semen extender resulted in improved cleavage and blastocyst rates after semen cryopreservation. Similarly, another study demonstrated that supplementing boar semen with CGA enhances in vitro fertilization outcomes (Namula et al., 2018). Our findings indicate that using 150 µM CGA and 0.6 mM rutin improves fertility in vivo compared to the control group. Additionally, other studies suggest that adding antioxidants to buffalo sperm extenders enhances fertility (Longobardi et al., 2017; Mohammadi et al., 2024; Ramazani et al., 2023a). Quercetin has also been found to enhance sperm fertility in vivo. Furthermore, adding cysteine during cryopreservation of buffalo sperm activates the antioxidant system, improves sperm motility and increases in vivo fertility (Iqbal et al., 2016).

5. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the supplementation of rutin and CGA to the seminal fluid extender results in enhanced sperm motility, improved PMF, decreased impairment of sperm viability and heightened sperm antioxidant capability. Hence, incorporating rutin and CGA holds promise for ameliorating the quality of cryopreserved buffalo semen. This investigation further posits that rutin and CGA may be beneficial for enhancing in vivo fertility.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Tohid Mohammadi was involved in the idea, design, data collecting, statistical analysis and paper preparation. Tohid Mohammadi and Mohammadreza Hosseinchi Gharehaghaji all contributed to the study's supervision as well as the manuscript's drafting. The final version was accepted for submission by all writers.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research has not been financially supported.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The authors confirm the ethical policies of the journal, as noted on the journal's author guidelines page. The study was carried out in accordance with the regulations of the Animal Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Iran (IR‐IAU‐2/37/29).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the members of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Islamic Azad University Urmia Branch Research Council, for the approval and support of this research.

Mohammadi, T. , & Hosseinchi Gharehaghaji, M. (2024). The influence of rutin and chlorogenic acid on oxidative stress and in vivo fertility: Evaluation of the quality and antioxidant status of post‐thaw semen from Azari water buffalo bulls. Veterinary Medicine and Science, 10, e31548. 10.1002/vms3.1548

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- Ahmed, H. , Andrabi, S. M. H. , & Jahan, S. (2016). Semen quality parameters as fertility predictors of water buffalo bull spermatozoa during low‐breeding season. Theriogenology, 86(6), 1516–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, H. , Jahan, S. , Khan, A. , Khan, L. , Khan, B. T. , Ullah, H. , Riaz, M. , & Ullah, K. (2020). Supplementation of green tea extract (GTE) in extender improves structural and functional characteristics, total antioxidant capacity and in vivo fertility of buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) bull spermatozoa. Theriogenology, 145, 190–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, H. , Jahan, S. , Salman, M. M. , & Ullah, F. (2019). Stimulating effects of quercetin (QUE) in tris citric acid extender on post thaw quality and in vivo fertility of buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) bull spermatozoa. Theriogenology, 134, 18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aksu, E. H. , Kandemir, F. M. , Özkaraca, M. , Ömür, A. D. , Küçükler, S. , & Çomaklı, S. (2017). Rutin ameliorates cisplatin‐induced reproductive damage via suppression of oxidative stress and apoptosis in adult male rats. Andrologia, 49(1), e12593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, J. G. , & Storey, B. T. (1995). Differential incorporation of fatty acids into and peroxidative loss of fatty acids from phospholipids of human spermatozoa. Molecular Reproduction and Development, 42(3), 334–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annapurna, A. , Ansari, M. A. , & Manjunath, P. M. (2013). Partial role of multiple pathways in infarct size limiting effect of quercetin and rutin against cerebral ischemia‐reperfusion injury in rats. European Review for Medical & Pharmacological Sciences, 17(4), 491–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, M. S. , Rakha, B. A. , Andrabi, S. M. H. , Ullah, N. , Iqbal, R. , Holt, W. V , & Akhter, S. (2012). Glutathione‐supplemented tris‐citric acid extender improves the post‐thaw quality and in vivo fertility of buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) bull spermatozoa. Reproductive Biology, 12(3), 271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anzar, M. , He, L. , Buhr, M. M. , Kroetsch, T. G. , & Pauls, K. P. (2002). Sperm apoptosis in fresh and cryopreserved bull semen detected by flow cytometry and its relationship with fertility. Biology of Reproduction, 66(2), 354–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archana, S. S. , Swathi, D. , Ramya, L. , Heena, H. S. , Krishnappa, B. , Binsila, B. K. , Rajendran, D. , & Selvaraju, S. (2023). Relationship among seminal antigenicity, antioxidant status and metabolically active sperm from Holstein‐Friesian (Bos taurus) bulls. Systems Biology in Reproductive Medicine, 69(5), 366–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashabi, M. , Soleimanzadeh, A. , & Ayen, E. (2023). Effect of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) on sperm quality during liquid storage of canine semen at 5°C. Veterinary Research & Biological Products, 37(2), 53‐61.

- Borghese, A. , & Mazzi, M. (2005). Buffalo population and strategies in the world. Buffalo Production and Research, 67, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bucak, M. N. , Ateşşahin, A. , Varışlı, Ö. , Yüce, A. , Tekin, N. , & Akçay, A. (2007). The influence of trehalose, taurine, cysteamine and hyaluronan on ram semen: Microscopic and oxidative stress parameters after freeze–thawing process. Theriogenology, 67(5), 1060–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cândido, T. M. , De Oliveira, C. A. , Ariede, M. B. , Velasco, M. V. R. , Rosado, C. , & Baby, A. R. (2018). Safety and antioxidant efficacy profiles of rutin‐loaded ethosomes for topical application. AAPS PharmSciTech, 19, 1773–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro, A. , Oda, F. B. , Almeida‐Cincotto, M. G. J. , Davanço, M. G. , Chiari‐Andréo, B. G. , Cicarelli, R. M. B. , Peccinini, R. G. , Zocolo, G. J. , Ribeiro, P. R. V , & Corrêa, M. A. (2018). Green coffee seed residue: A sustainable source of antioxidant compounds. Food Chemistry, 246, 48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, S. , de Lamirande, E. , & Gagnon, C. (2001). Cryopreservation alters membrane sulfhydryl status of bull spermatozoa: Protection by oxidized glutathione. Molecular Reproduction and Development: Incorporating Gamete Research, 60(4), 498–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrzczanowicz, J. , Gawron, A. , Zwolinska, A. , de Graft‐Johnson, J. , Krajewski, W. , Krol, M. , Markowski, J. , Kostka, T. , & Nowak, D. (2008). Simple method for determining human serum 2, 2‐diphenyl‐1‐picryl‐hydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity–possible application in clinical studies on dietary antioxidants. Clinical Chemical Laboratory Medicine, 46(3), 342–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorostkar, K. , Alavi‐Shoushtari, S. M. , & Mokarizadeh, A. (2012). Effects of in vitro selenium addition to the semen extender on the spermatozoa characteristics before and after freezing in water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis). Veterinary Research Forum, 3(4), 263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudylina, A. L. , Ivanova, M. V , Shumaev, K. B. , & Ruuge, E. K. (2019). Superoxide formation in cardiac mitochondria and effect of phenolic antioxidants. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics, 77, 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejaz, R. , Ansari, M. S. , Rakha, B. A. , Ullah, N. , Husna, A. U. , Iqbal, R. , & Akhter, S. (2014). Arachidic acid in extender improves post‐thaw parameters of cryopreserved Nili‐Ravi buffalo bull semen. Reproduction in Domestic Animals, 49(1), 122–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El‐Sheshtawy, R. I. , El‐Sisy, G. A. , & El‐Nattat, W. S. (2008). Use of selected amino acids to improve buffalo bull semen cryopreservation. Global Veterinaria, 2(4), 146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Escalante, R. C. , Poock, S. E. , Mathew, D. J. , Martin, W. R. , Newsom, E. M. , Hamilton, S. A. , Pohler, K. G. , & Lucy, M. C. (2013). Reproduction in grazing dairy cows treated with 14‐day controlled internal drug release for presynchronization before timed artificial insemination compared with artificial insemination after observed estrus. Journal of Dairy Science, 96(1), 300–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farjami, A. , Soleimanzadeh, A. , & Ayen, E. (2023). Evaluation of co‐supplementation of rutin in Simmental bull semen extender: Evaluation of kinetic parameters, sperm quality. Veterinary Research & Biological Products, 37(1), 79‐88.

- Fu, J. , Yang, Q. , Li, Y. , Li, P. , Wang, L. , & Li, X. (2018). A mechanism by which Astragalus polysaccharide protects against ROS toxicity through inhibiting the protein dephosphorylation of boar sperm preserved at 4°C. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 233(7), 5267–5280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S. , Li, C. , Chen, L. , & Zhou, X. (2017). Actions and mechanisms of reactive oxygen species and antioxidative system in semen. Molecular & Cellular Toxicology, 13, 143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasi, M. , Azadnia, A. , Arabieh, M. , & Zahedi, M. (2012). Protective effect of rutin (vitamin p) against heme oxidation: A quantum mechanical approach. Computational and Theoretical Chemistry, 996, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Granado‐Serrano, A. B. , Angeles Martín, M. , Izquierdo‐Pulido, M. , Goya, L. , Bravo, L. , & Ramos, S. (2007). Molecular mechanisms of (−)‐epicatechin and chlorogenic acid on the regulation of the apoptotic and survival/proliferation pathways in a human hepatoma cell line. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 55(5), 2020–2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.‐J. , Luo, T. , Wu, F. , Mei, Y.‐W. , Peng, J. , Liu, H. , Li, H.‐R. , Zhang, S.‐L. , Dong, J.‐H. , & Fang, Y. (2015). Involvement of TLR2 and TLR9 in the anti‐inflammatory effects of chlorogenic acid in HSV‐1‐infected microglia. Life Sciences, 127, 12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.‐H. , Zan, L.‐S. , Zhao, X.‐L. , Li, Q.‐W. , Jiang, Z.‐L. , Li, Y.‐K. , & Li, X. (2010). Effects of trehalose supplementation on semen quality and oxidative stress variables in frozen‐thawed bovine semen. Journal of Animal Science, 88(5), 1657–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ijaz, A. , Hussain, A. , Aleem, M. , Yousaf, M. S. , & Rehman, H. (2009). Butylated hydroxytoluene inclusion in semen extender improves the post‐thawed semen quality of Nili‐Ravi buffalo (Bubalus bubalis). Theriogenology, 71(8), 1326–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, S. , Riaz, A. , Andrabi, S. M. H. , Shahzad, Q. , Durrani, A. Z. , & Ahmad, N. (2016). l‐Cysteine improves antioxidant enzyme activity, post‐thaw quality and fertility of Nili‐Ravi buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) bull spermatozoa. Andrologia, 48(9), 943–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izanloo, H. , Soleimanzadeh, A. , Bucak, M. N. , Imani, M. , & Zhandi, M. (2021). The effects of varying concentrations of glutathione and trehalose in improving microscopic and oxidative stress parameters in Turkey semen during liquid storage at 5°C. Cryobiology, 101, 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izanloo, H. , Soleimanzadeh, A. , Bucak, M. N. , Imani, M. , & Zhandi, M. (2022). The effects of glutathione supplementation on post‐thawed Turkey semen quality and oxidative stress parameters and fertilization, and hatching potential. Theriogenology, 179, 32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahangiri Asl, E. , Soleimanzadeh, A. , Javadi, S. , & Asri Rezaei, S. (2021). The effect of intratesticular injection of zinc oxide nanoparticles on plasma concentrations of LH, FSH, testosterone and corticosterone in Rat. Veterinary Research & Biological Products, 34(2), 103–194. [Google Scholar]

- Jamalan, M. , Ghaffari, M. A. , Hoseinzadeh, P. , Hashemitabar, M. , & Zeinali, M. (2016). Human sperm quality and metal toxicants: Protective effects of some flavonoids on male reproductive function. International Journal of Fertility & Sterility, 10(2), 215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadirvel, G. , Kumar, S. , & Kumaresan, A. (2009). Lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial membrane potential and DNA integrity of spermatozoa in relation to intracellular reactive oxygen species in liquid and frozen‐thawed buffalo semen. Animal Reproduction Science, 114(1–3), 125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M. , & Ijaz, A. (2007). Assessing undiluted, diluted and frozen‐thawed Nili‐Ravi buffalo bull sperm by using standard semen assays. Italian Journal of Animal Science, 6(Suppl 2), 784–787. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R. A. , Khan, M. R. , Ahmed, M. , Shah, M. S. , Rehman, S. U. , Khan, J. , Husain, M. , Khan, F. A. , Khan, M. M. , & Shifa, M. S. (2017). Effects of rutin on testicular antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxidation in rats. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, 51, 412–417. [Google Scholar]

- Kumaresan, A. , Ansari, M. R. , Garg, A. , & Kataria, M. (2006). Effect of oviductal proteins on sperm functions and lipid peroxidation levels during cryopreservation in buffaloes. Animal Reproduction Science, 93(3–4), 246–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, R. , Zhao, H. , Li, B. , Wang, S. , & Hua, S. (2023). Soybean lecithin and cholesterol‐loaded cyclodextrin in combination to enhances the cryosurvival of dairy goat semen. Cryobiology, 112, 104557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. , Wang, W. , Liu, X. , Wang, X. , Wang, J. , Wang, Y. , Li, N. , & Wang, X. (2018). Supplementation of cryopreservation medium with TAT‐peroxiredoxin 2 fusion protein improves human sperm quality and function. Fertility and Sterility, 110(6), 1058–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longobardi, V. , Zullo, G. , Salzano, A. , De Canditiis, C. , Cammarano, A. , De Luise, L. , Puzio, M. V. , Neglia, G. , & Gasparrini, B. (2017). Resveratrol prevents capacitation‐like changes and improves in vitro fertilizing capability of buffalo frozen‐thawed sperm. Theriogenology, 88, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X. , Wu, D. , Liang, M. , Huang, S. , Shi, D. , & Li, X. (2023). The effects of melatonin, glutathione and vitamin E on semen cryopreservation of Mediterranean buffalo. Theriogenology, 197, 94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata‐Campuzano, M. , Álvarez‐Rodríguez, M. , Del Olmo, E. , Fernández‐Santos, M. R. , Garde, J. J. , & Martínez‐Pastor, F. (2012). Quality, oxidative markers and DNA damage (DNA) fragmentation of red deer thawed spermatozoa after incubation at 37°C in presence of several antioxidants. Theriogenology, 78(5), 1005–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehfooz, A. , Wei, Q. , Zheng, K. , Fadlalla, M. B. , Maltasic, G. , & Shi, F. (2018). Protective roles of Rutin against restraint stress on spermatogenesis in testes of adult mice. Tissue and Cell, 50, 133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng, S. , Cao, J. , Feng, Q. , Peng, J. , & Hu, Y. (2013). Roles of chlorogenic acid on regulating glucose and lipids metabolism: A review. Evidence‐Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine: ECAM, 2013(1), 801457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, T. , hosseinchi Gharehaghaj, M. , & Novin, A. A. (2024). Effects of apigenin and trans‐ferulic acid on microscopic and oxidative stress parameters in the semen of water buffalo bulls during cryopreservation. Cryobiology, 115, 104868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, A. A. , El‐Belely, M. S. , Ismail, S. T. , El‐Sheshtawy, R. I. , & Shahba, M. I. (2019). Effect of butylated hydroxytoluene on quality of pre—Frozen and frozen buffalo semen. Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction, 8(1), 20. [Google Scholar]

- Mussatto, S. I. , Ballesteros, L. F. , Martins, S. , & Teixeira, J. A. (2011). Extraction of antioxidant phenolic compounds from spent coffee grounds. Separation and Purification Technology, 83, 173–179. [Google Scholar]

- Najafi, A. , Mohammadi, H. , & Sharifi, S. D. (2023). Enhancing post‐thaw quality of ram epididymal sperm by supplementation of rutin in cryopreservation extender. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 10873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namula, Z. , Hirata, M. , Wittayarat, M. , Tanihara, F. , Thi Nguyen, N. , Hirano, T. , Nii, M. , & Otoi, T. (2018). Effects of chlorogenic acid and caffeic acid on the quality of frozen‐thawed boar sperm. Reproduction in Domestic Animals, 53(6), 1600–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayana, K. , D'Souza, U. J. A. , & Rao, K. P. S. (2002). Ribavirin‐induced sperm shape abnormalities in Wistar rat. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis, 513(1), 193–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldenhof, H. , Gojowsky, M. , Wang, S. , Henke, S. , Yu, C. , Rohn, K. , Wolkers, W. F. , & Sieme, H. (2013). Osmotic stress and membrane phase changes during freezing of stallion sperm: Mode of action of cryoprotective agents. Biology of Reproduction, 88(3), 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagl, R. , Aurich, J. E. , Müller‐Schlösser, F. , Kankofer, M. , & Aurich, C. (2006). Comparison of an extender containing defined milk protein fractions with a skim milk‐based extender for storage of equine semen at 5°C. Theriogenology, 66(5), 1115–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partyka, A. , Łukaszewicz, E. , & Niżański, W. (2012). Effect of cryopreservation on sperm parameters, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes activity in fowl semen. Theriogenology, 77(8), 1497–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña, F. J. , Rodríguez Martínez, H. , Tapia, J. A. , Ortega Ferrusola, C. , Gonzalez Fernandez, L. , & Macias Garcia, B. (2009). Mitochondria in mammalian sperm physiology and pathology: A review. Reproduction in Domestic Animals, 44(2), 345–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, B. A. , Zangeronimo, M. G. , Sousa, R. V. , Teles, M. C. , Mendez, M. F. B. , & Rocha, L. G. P. (2014). Effet de l'acide chlorogénique sur la peroxydation lipidique et la capacité antioxydante du sperme de verrat. Journées de La Recherhe Porcine, 46, 293–294. [Google Scholar]

- pour Azary, M. A. , Pirmohammadi, R. , & Manafi Azar, Q. Breeding of buffaloes in West Azerbaijan of Iran. In Proceedings of the seventh world buffalo congress, manila, Philippines, 20 to 23 October 2004 (pp. 535–537).

- Rabelo, S. S. , Resende, C. O. , Pontelo, T. P. , Chaves, B. R. , Pereira, B. A. , da Silva, W. E. , Peixoto, J. V. , Pereira, L. J. , & Zangeronimo, M. G. (2020). Chlorogenic acid improves the quality of boar semen processed in Percoll. Animal Reproduction, 17, e20190021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramazani, N. , Mahd Gharebagh, F. , Soleimanzadeh, A. , Arslan, H. , Keles, E. , Gradinarska‐Yanakieva, D. G. , Arslan‐Acaröz, D. , Zhandi, M. , Baran, A. , & Ayen, E. (2023a). Reducing oxidative stress by κ‐carrageenan and C60HyFn: The post‐thaw quality and antioxidant status of Azari water buffalo bull semen. Cryobiology, 111, 104–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramazani, N. , Mahd Gharebagh, F. , Soleimanzadeh, A. , Arslan, H. O. , Keles, E. , Gradinarska‐Yanakieva, D. G. , Arslan‐Acaröz, D. , Zhandi, M. , Baran, A. , & Ayen, E. (2023b). The influence of l‐proline and fulvic acid on oxidative stress and semen quality of buffalo bull semen following cryopreservation. Veterinary Medicine and Science, 9(4), 1791–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, N. S. S. , Mohanarao, G. J. , & Atreja, S. K. (2010). Effects of adding taurine and trehalose to a tris‐based egg yolk extender on buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) sperm quality following cryopreservation. Animal Reproduction Science, 119(3–4), 183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi, S. , Soleimanzadeh, A. , Goericke‐Pesch, S. , & Ayen, E. (2023). Evaluation of the effects of crocin addition on canine semen dilution during refrigerated storage. Iranian Journal of Animal Science, 54(3), 303–315. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, Q. , Mehmood, M. U. , Khan, H. , ul Husna, A. , Qadeer, S. , Azam, A. , Naseer, Z. , Ahmad, E. , Safdar, M. , & Ahmad, M. (2016). Royal jelly supplementation in semen extender enhances post‐thaw quality and fertility of Nili‐Ravi buffalo bull sperm. Animal Reproduction Science, 167, 83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikholeslami, S. A. , Soleimanzadeh, A. , Rakhshanpour, A. , & Shirani, D. (2020). The evaluation of lycopene and cysteamine supplementation effects on sperm and oxidative stress parameters during chilled storage of canine semen. Reproduction in Domestic Animals, 55(9), 1229–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleimanzadeh, A. , Talavi, N. , Yourdshahi, V. S. , & Bucak, M. N. (2020). Caffeic acid improves microscopic sperm parameters and antioxidant status of buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) bull semen following freeze‐thawing process. Cryobiology, 95, 29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleimanzadeh, A. , Kian, M. , Moradi, S. , & Mahmoudi, S. (2020). Carob (Ceratonia siliqua L.) fruit hydro‐alcoholic extract alleviates reproductive toxicity of lead in male mice: Evidence on sperm parameters, sex hormones, oxidative stress biomarkers and expression of Nrf2 and iNOS. Avicenna Journal of Phytomedicine, 10(1), 35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleimanzadeh, A. , Kian, M. , Moradi, S. , & Malekifard, F. (2018). Protective effects of hydro‐alcoholic extract of Quercus brantii against lead‐induced oxidative stress in the reproductive system of male mice. Avicenna Journal of Phytomedicine, 8(5), 448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleimanzadeh, A. , Malekifard, F. , & Kabirian, A. R. (2017). Protective effects of hydro‐alcoholic garlic extract on spermatogenic disorders in streptozotocin‐induced diabetic C57BL/6 mice. Scientific Journal of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, 22(4), 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Soleimanzadeh, A. , Saberivand, A. , & Ahmadi, A. (2014). Effect of α‐tocopherol on spermatozoa of rat semen after the freeze‐thawing process. Urmia Medical Journal, 25(9), 826–834. [Google Scholar]

- Soleimanzadeh, A. , & Saberivand, A. (2013). Effect of curcumin on rat sperm morphology after the freeze‐thawing process. Veterinary Research Forum, 4(3), 185–189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swami, D. S. , Kumar, P. , Malik, R. K. , Saini, M. , Kumar, D. , & Jan, M. H. (2017). The cryoprotective effect of iodixanol in buffalo semen cryopreservation. Animal Reproduction Science, 179, 20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariq, M. , Khan, M. S. , Shah, M. G. , Nisha, A. R. , Umer, M. , Hasan, S. M. , Rahman, A. , & Rabbani, I. (2015). Exogenous antioxidants inclusion during semen cryopreservation of farm animals. Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research, 7(3), 2273–2280. [Google Scholar]

- Topraggaleh, T. R. , Shahverdi, A. , Rastegarnia, A. , Ebrahimi, B. , Shafiepour, V. , Sharbatoghli, M. , Esmaeili, V. , & Janzamin, E. (2014). Effect of cysteine and glutamine added to extender on post‐thaw sperm functional parameters of buffalo bull. Andrologia, 46(7), 777–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turaja, K. I. B. , Vega, R. S. A. , Saludes, T. A. , Tandang, A. G. , Bautista, J. A. N. , Salces, A. J. , & Rebancos, C. M. (2019). Influence and total antioxidant capacity of non‐enzymatic antioxidants on the quality and integrity of extended and cryopreserved semen of Murrah buffalo (Bubalus bubalis). Philippine Journal of Science, 148(4), 619–626. [Google Scholar]

- Venditti, A. , Bianco, A. , Frezza, C. , Conti, F. , Bini, L. M. , Giuliani, C. , Bramucci, M. , Quassinti, L. , Damiano, S. , & Lupidi, G. (2015). Essential oil composition, polar compounds, glandular trichomes and biological activity of Hyssopus officinalis subsp. aristatus (Godr.) Nyman from central Italy. Industrial Crops and Products, 77, 353–363. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) . (1999). WHO laboratory manual for the examination of human semen and sperm‐cervical mucus interaction. Cambridge university press. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D. , Wu, L. , Yang, L. , Liu, D. , Chen, H. , Geng, G. , & Li, Q. (2020). Rutin protects boar sperm from cryodamage via enhancing the antioxidative defense. Animal Science Journal, 91(1), e13328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, C. , Wang, J. , & Lu, W. (2023). Regulation of semen quality by fatty acids in diets, extender, and semen. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 10, 1119153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.