Abstract

Background

This study examined inpatient mortality factors in geriatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) using data from the 2016 to 2020 National Inpatient Sample.

Methods

Identifying patients through ICD-10 codes, a total of 127,985 individuals with AML were classified into age categories as follows: 50.58% were 65 to 74 years, 37.74% were 75 to 84 years, and 11.68% were 85 years or older. Statistical analysis, conducted with STATA, involved Fisher’s exact and Student’s t tests for variable comparisons. Mortality predictors were identified through multivariate logistic regression.

Results

Various hospital and patient-level factors, including an increase in age, race, a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index score, insurance status, and specific comorbidities such as atrial fibrillation and protein-calorie malnutrition, independently elevated the risk of inpatient mortality. Asthma, hyperlipidemia, and inpatient chemotherapy were linked to lower mortality. Although there was no statistically significant mortality rate change from 2016 to 2020, a decline in chemotherapy use in the eldest age group was noted.

Conclusion

This study highlights the complexity of factors influencing inpatient mortality among geriatric patients with AML, emphasizing the need for personalized clinical approaches in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: Acute myeloid leukemia, comorbidities, geriatrics, inpatient chemotherapy, inpatient mortality, National Inpatient Sample

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a diverse form of blood cancer resulting from genetic and epigenetic alterations in hematopoietic stem and/or progenitor cells, leading to abnormal growth and differentiation. AML is largely a disease of older adults, characterized by disproportionately worse survival associated with increasing age.1,2 As a result, only 2% of elderly patients are expected to live for 5 years after diagnosis.3

Geriatric patients with AML represent a unique and challenging population due to age-related physiological changes, increased vulnerability to treatment-related toxicities, and the presence of multiple comorbidities. Poor survival outcomes in older AML patients can be attributed to the higher prevalence of adverse prognostic factors and comorbidities, as well as a tendency among physicians to opt for less aggressive treatments, anticipating reduced benefits from intensive therapies in this population.4 Patients with AML may be hospitalized due to diagnosis and initial assessment, induction chemotherapy, treatment-related complications, infections, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and supportive care. Previous studies have demonstrated that the presence of comorbidities is associated with higher mortality rates and resource utilization; however, there is limited data about the impact of comorbidities on all-cause inpatient mortality for AML patients.

The National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database is a valuable resource for investigating population-based health outcomes and disparities.5 It provides a large sample size and a diverse patient population, allowing for robust analyses of various factors affecting inpatient outcomes. In this retrospective analysis utilizing NIS data from 2016 to 2020, we aimed to explore the impact of multiple patient and hospital-level characteristics, including various comorbidities, on all-cause inpatient mortality rates among hospitalized geriatric patients with AML, while concurrently investigating the 5-year trajectories of inpatient mortality and chemotherapy usage in this group. By identifying the most significant comorbidities and trends, we aim to better inform clinical decision-making, optimize treatment strategies, and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

METHODS

Study design and database description

This retrospective investigation focused on the hospitalization of geriatric patients associated with AML utilizing data from the NIS6 between 2016 and 2020. Covering 98% of the US population, the NIS is part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), which is sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.7 The NIS is the most all-encompassing, deidentified, and publicly accessible inpatient database in the United States. It is designed as a stratified 20% sample of all hospital stays across the country, with each discharge being weighted to achieve a representative national sample.

In this study, patient demographics included factors such as age, sex, ethnicity, median household earnings, and insurance coverage. To address comorbidities, we employed the Charlson Comorbidity Index8 and took into account various clinically significant comorbid conditions by using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes.

Hospitals were grouped based on characteristics like bed capacity, geographical area, teaching status, and urban or rural location. Moreover, hospital admissions were designated as elective or nonelective, and the day of admission was distinguished as a weekday or weekend occurrence.

The adjusted charges for each year were computed in 2020-equivalent dollars by utilizing consumer price index data to account for inflation.9

Study patients

The study included patients hospitalized with AML, as identified by ICD-10-CM codes, which have been in use in the US since October 2015. Patients <65 years of age were excluded from the study. The study population was then divided into three age-based groups, with a comparison of their characteristics outlined in Table 1. The specific ICD-10-CM codes employed are available in Supplementary Table 1. Although institutional review board approval was sought for this research, it was deemed exempt due to its retrospective nature and the use of previously collected data.

Table 1.

Patient and hospital characteristics

| Variable | Age (years) |

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65–74 | 75–84 | ≥85 | ||

| N (%) | 64,730 (50.58%) | 48,300 (37.74%) | 14,955 (11.86%) | |

| Female, (%) | 41.15 | 39.98 | 46.53 | <0.001 |

| Age, years (mean) | 69.60 | 78.91 | 87.67 | <0.001 |

| Race (%) | <0.001 | |||

| White | 76.99 | 79.77 | 80.46 | |

| Black | 9.56 | 7.29 | 7.88 | |

| Hispanics | 6.08 | 5.78 | 6.14 | |

| Native Americans/ Pacific Islanders/ Other | 7.36 | 7.16 | 5.52 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (%) | <0.001 | |||

| ≤2 | 35.08 | 30.17 | 24.74 | |

| 3 | 26.38 | 24.40 | 22.03 | |

| 4 | 16.74 | 18.00 | 19.73 | |

| ≥5 | 21.81 | 27.43 | 33.50 | |

| Insurance status (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Medicare | 83.73 | 92.47 | 94.42 | |

| Medicaid | 1.61 | 0.85 | 0.75 | |

| Private | 14.01 | 6.26 | 4.56 | |

| Uninsured | 0.66 | 0.41 | 0.27 | |

| Median household income (quartile) (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 1st (0–25th) | 22.67 | 21.43 | 19.78 | |

| 2nd (25–50th) | 25.71 | 23.90 | 24.10 | |

| 3rd (50–75th) | 25.97 | 26.00 | 26.70 | |

| 4th (75–100th) | 25.65 | 28.67 | 29.43 | |

| Hospital region (%) | 0.006 | |||

| Northeast | 19.69 | 21.65 | 23.30 | |

| Midwest | 22.23 | 22.61 | 23.07 | |

| South | 37.55 | 37.04 | 33.97 | |

| West | 20.53 | 18.71 | 19.66 | |

| Hospital bed-size (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Small | 12.45 | 15.83 | 18.72 | |

| Medium | 20.81 | 25.09 | 27.52 | |

| Large | 66.74 | 59.08 | 53.76 | |

| Teaching status | <0.001 | |||

| Nonteaching | 15.05 | 22.86 | 26.71 | |

| Teaching | 84.95 | 77.14 | 73.29 | |

| Hospital location | <0.001 | |||

| Rural | 3.69 | 5.35 | 6.15 | |

| Urban | 96.31 | 94.65 | 93.85 | |

| Admission day (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Weekday | 81.45 | 78.73 | 76.73 | |

| Weekend | 18.55 | 21.27 | 23.27 | |

| Elective versus nonelective (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Nonelective | 80.45 | 89.18 | 93.33 | |

| Elective | 19.55 | 10.82 | 6. 67 | |

| Comorbidities (%) | ||||

| COPD | 14.52 | 15.45 | 13.04 | 0.007 |

| Asthma | 4.58 | 4.40 | 3.44 | 0.036 |

| CKD5/ESRD | 6.38 | 8.24 | 9.50 | <0.001 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 1.68 | 1.25 | 0.53 | <0.001 |

| CHF | 14.78 | 19.76 | 26.88 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 16.42 | 23.60 | 28.52 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 43.45 | 39.29 | 36.91 | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 32.96 | 37.61 | 39.79 | <0.001 |

| H/O CVA with neurological deficits | 1.39 | 1.17 | 1.71 | 0.080 |

| Neutropenia | 19.92 | 16.42 | 11.57 | <0.001 |

| Coagulopathy | 0.74 | 0.90 | 1.04 | 0.199 |

| HIV | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0 | 0.112 |

| HCV | 1.12 | 0.27 | 0.33 | <0.001 |

| Marijuana | 0.39 | 0.09 | 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Opioid abuse | 0.59 | 0.27 | 0.13 | 0.001 |

| Alcohol abuse | 1.62 | 0.90 | 0.40 | <0.001 |

| Protein-calorie malnutrition | 13.80 | 13.19 | 10.0 | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 11.11 | 6.90 | 3.78 | <0.001 |

| Inpatient chemotherapy use | 23.71 | 12.81 | 5.42 | <0.001 |

CHF indicates congestive heart failure; CKD5, chronic kidney disease stage 5; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; H/O CVA, history of cerebrovascular accident; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Statistical analysis

We conducted our analyses utilizing STATA MP 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). NIS data is the product of a multifaceted sampling design that combines stratification, clustering, and weighting. We applied weights to patient-level observations to create estimates for the total population of hospitalizations related to AML patients. To compare proportions, we applied the Fisher exact test, and for continuous variables, we used the Student t test.10 Multivariate logistic regression analysis was executed to identify potential independent factors predicting all-cause inpatient mortality, incorporating hospital and patient characteristics deemed clinically significant to the outcome from the literature. For trends analysis, we employed a multivariate regression model adjusted for gender and race. All P values were calculated using a two-sided test, and a value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

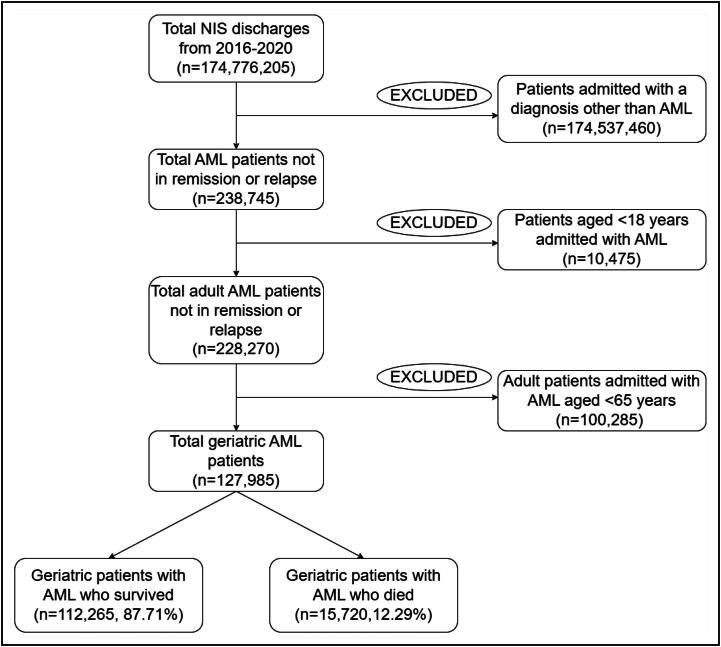

Spanning the years from 2016 to 2020, the NIS database registered 174,776,205 weighted discharges. The flowchart in Figure 1 depicts the process of selecting study participants according to the inclusion criteria. Among these 238,745 patients were classified as having AML not in remission or experiencing a relapse. Upon narrowing this subset by age, we found 127,985 patients who were 65 years or older, aligning with the demographic requirements for our study.

Figure 1.

Patient selection flow diagram. AML indicates acute myeloid leukemia; NIS, National Inpatient Sample.

Within this group of elderly patients, the mean length of hospital stay was 9.99 days, resulting in a total of 1,278,725 days of hospitalization of the study population over the period of 5 years. The mean charge amounted to $127,317, while the mean cost was $31,030. This led to a total charge of approximately $16.2 billion and a cost of $3.94 billion over the given period. Moreover, 12.29% (n = 15,720) of these hospitalized individuals did not survive their inpatient stay.

Patient and hospital characteristics

Table 1 provides data on the geriatric patients diagnosed with AML by three age segments (65–74, 75–84, and ≥85), with the groups containing 64,730, 48,300, and 14,955 patients, respectively. A comparative analysis revealed significant statistical disparities among these groups concerning various parameters, including gender, mean age, racial background, Charlson Comorbidity Index, insurance coverage type, average household income, geographic region of the hospital, hospital bed size, the teaching status of the hospital, hospital location, day of admission, and the nature of admission (elective or nonelective).

The demographic group aged 65 to 74 years, which we term the “youngest old,” had the highest frequency of hospital admissions. The average age within this segment was 69.60 years, with women representing 41.15% of cases. In contrast, those aged 85 or older, referred to as the “oldest old,” registered the fewest hospital stays. The mean age in this group was 87.67 years, and females comprised 46.53% of the cases.

Across all age categories, the White population represented the majority. However, their representation was most pronounced in the oldest age group, accounting for 80.46% of the total. With advancing age, there was a shift toward higher Charlson Comorbidity Index scores and increased use of Medicare.

When considering hospital-related characteristics, hospitals in the Northeast and Midwest regions had the greatest proportion of patients in the oldest age group, at 23.3% and 23.07%, respectively. This trend was observed in small hospitals (18.72%), medium hospitals (27.52%), and hospitals located in rural areas (6.15%). Admissions during weekends and under nonelective circumstances were more prevalent among this elderly group.

In the realm of concurrent diseases, the “oldest old” group frequently exhibited chronic kidney disease stage 5/end-stage renal disease (9.5%), congestive heart failure (26.8%), atrial fibrillation (28.52%), and hyperlipidemia (39.79%). Meanwhile, the “youngest old” group tended to have higher rates of asthma (4.58%), liver cirrhosis (1.68%), hypertension (43.45%), neutropenia (19.92%), HIV (0.13%), marijuana use (0.39%), opioid abuse (0.59%), alcohol abuse (1.62%), obesity (1.11%), and protein-calorie malnutrition (13.8%). Furthermore, this group was the major recipient of inpatient chemotherapy as well.

Predictors of all-cause inpatient mortality

Table 2 summarizes the predictors of all-cause inpatient mortality for geriatric patients with AML. The likelihood of mortality increased with age, with those >85 (odds ratio of 1.27) being significantly more likely to die in the hospital than those aged 65 to 74 (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Predictors of all-cause inpatient mortality for geriatric patients with AML

| Adjusted odds ratio for mortality | Confidence interval | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 0.95 | 0.88–1.03 | 0.236 |

| Age (years) | |||

| 65–74 | Reference | ||

| 75–84 | 1.11 | 1.02–1.22 | 0.021 |

| ≥85 | 1.27 | 1.12–1.44 | <0.001 |

| Race | |||

| White | Reference | ||

| Black | 1.00 | 0.86–1.16 | 0.977 |

| Hispanics | 0.96 | 0.81–1.14 | 0.669 |

| Native Americans/ Pacific Islanders/ Other | 1.24 | 1.07–1.43 | 0.004 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |||

| ≤2 | Reference | ||

| 3 | 1.35 | 1.20–1.52 | <0.001 |

| 4 | 1.50 | 1.31–1.70 | <0.001 |

| ≥5 | 1.82 | 1.59–2.09 | <0.001 |

| Insurance status | |||

| Medicare | Reference | ||

| Medicaid | 0.98 | 0.68–1.41 | 0.911 |

| Private | 1.52 | 1.34–1.73 | <0.001 |

| Uninsured | 2.19 | 1.36–3.55 | 0.001 |

| Median household income (quartile) | |||

| 1st (0–25th) | Reference | ||

| 2nd (25–50th) | 0.76 | 0.84–1.06 | 0.340 |

| 3rd (50–75th) | 0.77 | 0.76–0.97 | 0.013 |

| 4th (75–100th) | 0.87 | 0.78–0.99 | 0.032 |

| Hospital region | |||

| Northeast | Reference | ||

| Midwest | 0.76 | 0.67–0.86 | <0.001 |

| South | 0.77 | 0.69–0.86 | <0.001 |

| West | 0.87 | 0.77–0.98 | 0.027 |

| Hospital bed-size | |||

| Small | Reference | ||

| Medium | 1.14 | 0.99–1.30 | 0.058 |

| Large | 1.19 | 1.06–1.35 | 0.003 |

| Hospital teaching status | |||

| Nonteaching | Reference | ||

| Teaching | 1.03 | 0.92–1.16 | 0.607 |

| Hospital location | |||

| Rural | Reference | ||

| Urban | 1.16 | 0.92–1.46 | 0.204 |

| Admission day | |||

| Weekday | Reference | ||

| Weekend | 1.15 | 1.04–1.27 | 0.003 |

| Elective versus nonelective | |||

| Nonelective | Reference | ||

| Elective | 0.69 | 0.60–0.80 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| COPD | 0.97 | 0.87–1.09 | 0.619 |

| Asthma | 0.67 | 0.54–0.83 | <0.001 |

| CKD5/ESRD | 1.14 | 0.98–1.32 | 0.079 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 1.07 | 0.78–1.48 | 0.673 |

| CHF | 1.10 | 0.99–1.22 | 0.091 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.41 | 1.28–1.56 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0.94 | 0.85–1.03 | 0.180 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0. 75 | 0.68–0.82 | <0.001 |

| H/o CVA with neurological deficits | 1.17 | 0.86–1.60 | 0.327 |

| Neutropenia | 1.04 | 0.94–1.16 | 0.440 |

| Coagulopathy | 1.41 | 0.95–2.08 | 0.084 |

| HIV | 1.95 | 0.65–5.89 | 0.234 |

| HCV | 0.95 | 0.58–1.58 | 0.855 |

| Marijuana | 1.20 | 0.57–2.52 | 0.624 |

| Opioid abuse | 0.81 | 0.41–1.59 | 0.537 |

| Alcohol abuse | 0.95 | 0.65–1.37 | 0.770 |

| Protein-calorie malnutrition | 1.31 | 1.17–1.46 | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 0.92 | 0.80–1.07 | 0.281 |

| Inpatient chemotherapy | 0.85 | 0.75–0.96 | 0.009 |

Native Americans/Pacific islanders/other races.

CHF indicates congestive heart failure; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; CKD5, chronic kidney disease stage 5; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

In terms of race, Native Americans/Pacific Islanders/other races had a significantly higher chance of mortality compared to Whites (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.24, P = 0.004). However, there was no significant difference between Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. Patients with higher Charlson Comorbidity Index scores (a measure of the number and seriousness of comorbid conditions) have a greater mortality risk. Those with scores ≥5 were significantly more likely to die in the hospital (aOR 1.82, P < 0.001) than those with scores of ≤2.

Patients with private insurance (aOR 1.52) or those uninsured (aOR 2.19) had a significantly higher adjusted odds of inpatient mortality compared to those with Medicare. The mortality risk decreased with higher household income quartiles, with the fourth quartile having a significantly lower risk than the first quartile (aOR 0.87, P = 0.03). Regarding hospital characteristics, patients in large hospitals, admitted over the weekend, or admitted electively had higher odds of mortality. Meanwhile, patients in hospitals in the Midwest, South, or West regions had lower mortality odds than those in the Northeast.

The presence of specific comorbidities, including atrial fibrillation and protein-calorie malnutrition, considerably raised the risk of inpatient mortality, as indicated by their respective aOR of 1.41 (P < 0.001) and 1.31 (P < 0.001). Conversely, asthma (aOR 0.67, P < 0.001) and hyperlipidemia (aOR 0.75, P < 0.001) significantly decreased the odds of inpatient mortality by 33% and 75%, respectively. Additionally, inpatient chemotherapy reduced the mortality risk (odds ratio 0.85, P = 0.009).

However, after adjusting for other variables, in our multivariate logistic regression model, the impact of other factors lacked statistical significance.

Five-year trends in all-cause hospital mortality and inpatient chemotherapy use in geriatric patients with AML

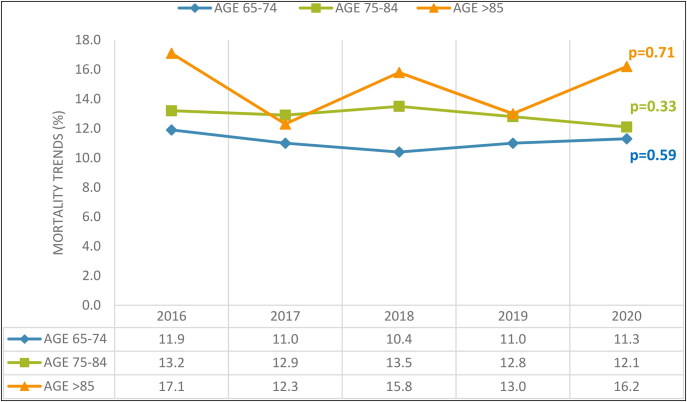

Figure 2 depicts the 5-year trend for all-cause inpatient mortality in elderly patients with AML, with adjustments for race and gender. While there was a noticeably higher adjusted mortality rate among the oldest compared to the less old group, the 5-year trend did not provide any statistically significant variations in the mortality rates across all age brackets.

Figure 2.

Trends in inpatient mortality for geriatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia.

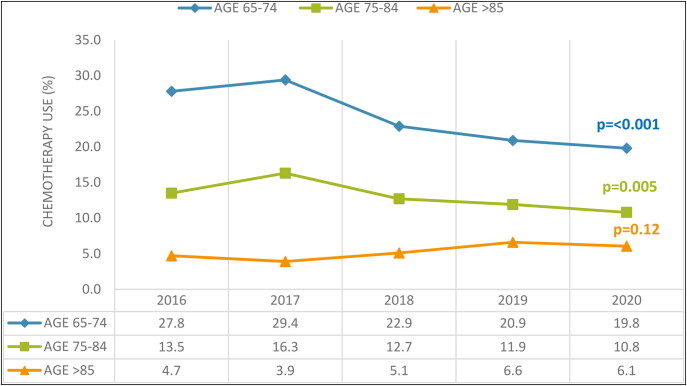

When considering inpatient chemotherapy use, there was a discernible decrease over 5 years in the youngest and middle-aged groups after adjustment for race and gender. The rate of inpatient chemotherapy use fell from 27.77% in 2016 to 19.83% in 2020 (P < 0.001), and from 13.59% to 10.83% (P = 0.005) in the same periods, respectively. Conversely, the oldest group, despite having a significantly lower adjusted inpatient chemotherapy rate than the other two groups, showed no statistically substantial change from 2016 to 2020. These trends are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Trends in inpatient chemotherapy use for geriatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia.

DISCUSSION

Our retrospective analysis using NIS data offers valuable insights into the key determinants of inpatient mortality among geriatric AML patients. This demographic is marked by extended hospital stays and significant related costs. In our 5-year analysis from 2016 to 2020, we found a sobering mortality rate of 12.29% during hospitalization. Several crucial variables emerged as significant influences on inpatient mortality, encompassing age, race, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, insurance coverage, median household income, hospital region, hospital bed size, and the day of admission. Among these, comorbidities like asthma, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, protein-calorie malnutrition, and the application of chemotherapy were found to substantially affect inpatient mortality rates.

Previous retrospective research using NIS data revealed an AML-related hospitalization mortality rate of 10.5% in 2018 for patients 60 years and older.11 However, our analysis, spanning 5 years, demonstrated a marginally higher mortality rate of 12.29%. This discrepancy might be explained by the fact that our study focused on a population aged 65 and above, hence older than the one in the prior study, leading to a higher mortality rate within our specific population. With advancing age and a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index, the risk of inpatient mortality rises in geriatric AML patients due to the cumulative effect of multiple chronic conditions and reduced physiological reserve, which can limit the tolerance to aggressive treatments and increase vulnerability to complications.12,13 Additionally, an elevated mortality rate among races other than the Black and Hispanic populations, in comparison to Whites, has been noted in earlier studies.11

The elevated odds of inpatient mortality seen in uninsured individuals and those with private insurance might be correlated to difficulties in accessing healthcare, disruptions in sustained care, and financial constraints stemming from the expensive nature of cancer treatments. This trend is paralleled in patients residing in low-income areas, possibly linked to the rising expenses of AML treatment, as indicated in past research.14,15 The increase in inpatient mortality rates in urban and larger hospitals, as displayed in Table 2, may be due to their frequent treatment of more complex and advanced-stage cases.

Regarding comorbidities, atrial fibrillation independently elevated inpatient mortality. This comorbidity, potentially linked to chemotherapy,16 hasn’t been thoroughly studied in AML. Additionally, anticoagulation can be complicated by AML and increased fragility with age.17 Protein-calorie malnutrition in AML patients can weaken the immune system, increase susceptibility to infections, and reduce tolerance to treatment, consequently leading to higher inpatient mortality rates.18

Interestingly, our study demonstrated that asthma and hyperlipidemia correlated with a reduced mortality risk in patients with AML. This supports the theory of immune surveillance for asthma.19,20 As for hyperlipidemia, the reduced mortality odds might be due to the use of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, or statins. These drugs may boost the anticancer activity of numerous cytokines and chemotherapy agents, as indicated by multiple clinical trials. However, additional trials are needed to confirm their cancer-preventing and treating efficiency21 and link to a reduction in inpatient death rates, an outcome attributable either to its capacity to control the disease or the reality that patients with more severe disease or multiple health issues aren’t suitable candidates for this treatment.

Conditions like congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease stage 5/end-stage renal disease, liver cirrhosis, residual effects from strokes, neutropenia, coagulopathy, HIV, and marijuana abuse may increase all-cause in-hospital death risk in AML patients, but they were not standalone mortality predictors in our analysis. Their statistical significance diminished when assessed in combination with other patient characteristics, hospital factors, and comorbidities, as listed in Table 1.

The 5-year trend analysis indicated a decrease in inpatient chemotherapy usage, likely resulting from advancements in outpatient care and chemotherapy follow-up procedures. Moreover, lower rates of inpatient chemotherapy are seen in older patients, suggesting a collective decision by physicians and patients to focus on maintaining a good quality of life rather than pursuing intensive treatments due to the heightened risk of comorbidities and decreased chemotherapy tolerance in this demographic.

There are various limitations to our study. The lack of laboratory values, patient history, physical examination records, and imaging outcomes in the HCUP database prevented us from measuring disease severity accurately. However, to address the comorbidity burden, we employed the Charlson Comorbidity Index, a well-accepted and validated prognostic instrument. Additionally, the absence of AML staging information or cytogenetic abnormalities in the HCUP database hindered us from stratifying our data according to the stage of AML. To identify AML patients, we relied on ICD-10 codes rather than clinical parameters, which may introduce diagnostic misclassification. However, the application of ICD-10 codes to distinguish patients with AML has been validated in prior studies utilizing HCUP data.11

In our analysis, mortality was described as all-cause inpatient mortality among geriatric patients with AML who were hospitalized, since the database did not allow us to identify the specific cause of death. Moreover, the observational framework of our study also restricted our capacity to infer a cause-effect relationship between the studied variables and outcomes. Subsequent randomized controlled trials are crucial to address the limitations of our study and to reinforce the robustness of the evidence.

Irrespective of the above limitations, our study has several strengths. We employed the NIS, consisting of deidentified patient information reflecting varied hospital-level characteristics from over 48 states. As a result, our conclusions have a high degree of external validity and generalizability, accurately reflecting the nationwide hospital-admitted patient population. Also, the NIS, as the largest all-payer and publicly available database, circumvents the typical restrictions found in single-center studies due to its extensive scale. The nationwide scope of our data set permitted the utilization of unique hospital and patient variables such as household income and hospital region, among others. These elements would be unattainable in studies centered on a single location. Moreover, this approach helps mitigate biases associated with specific practices observed in studies conducted within single or multiple centers.

CONCLUSION

Our retrospective study provides valuable insights into the inpatient mortality of geriatric patients with AML influenced by various factors such as age, comorbidities, and insurance type. No significant variation was found in the 5-year mortality trends across different age groups. However, a notable decline in inpatient chemotherapy use was observed, except in the “oldest old” group. These findings hold the potential to inform clinical practice, guiding the refinement of treatment strategies, risk stratification, and patient counseling, ultimately enhancing the care of geriatric patients with AML.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure statement/Funding

The authors report no funding or conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Appelbaum FR, Gundacker H, Head DR, et al. Age and acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2006;107(9):3481–3485. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kantarjian H, O'brien S, Cortes J, et al. Results of intensive chemotherapy in 998 patients age 65 years or older with acute myeloid leukemia or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome: predictive prognostic models for outcome. Cancer. 2006;106(5):1090–1098. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Löwenberg B, Downing JR, Burnett A.. Acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(14):1051–1062. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909303411407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juliusson G, Billström R, Gruber A, et al. Attitude towards remission induction for elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia influences survival. Leukemia. 2006;20(1):42–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodla ZH, Hashmi M, Niaz F, et al. Independent predictors of mortality and 5-year trends in mortality and resource utilization in hospitalized patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2024;37(1):16–24. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2023.2267921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Inpatient Sample (NIS) Database . https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/nisdbdocumentation.jsp. Accessed November 27, 2023.

- 7.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. https://www.ahrq.gov/data/hcup/index.html. Accessed November 27, 2023.

- 8.Charlson ME, Carrozzino D, Guidi J, Patierno C.. Charlson Comorbidity Index: a critical review of clinimetric properties. Psychother Psychosom. 2022;91(1):8–35. doi: 10.1159/000521288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Bureau of Labor Statistics . CPI inflation calculator. https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl. Accessed December 13, 2023.

- 10.Bodla ZH, Hashmi M, Niaz F, et al. Timing matters: an analysis of the relationship between red cell transfusion timing and hospitalization outcomes in sickle cell crisis patients using the National Inpatient Sample database. Ann Hematol. 2023;102(7):1669–1676. doi: 10.1007/s00277-023-05275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alam ST, Dongarwar D, Lopez E, et al. Disparities in mortality among acute myeloid leukemia-related hospitalizations. Cancer Med. 2023;12(3):3387–3394. doi: 10.1002/cam4.5084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klepin HD, Rao AV, Pardee TS.. Acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes in older adults. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(24):2541–2552. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang ES. Treating acute myeloid leukemia in older adults. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2014;2014(1):14–20. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2014.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley CJ, Dahman B, Jin Y, Shickle LM, Ginder GD.. Acute myeloid leukemia: how the uninsured fare. Cancer. 2011;117(20):4772–4778. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menzin J, Lang K, Earle CC, Kerney D, Mallick R.. The outcomes and costs of acute myeloid leukemia among the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(14):1597–1603. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.14.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levine LB, Roddy JV, Kim M, Li J, Phillips G, Walker AR.. A comparison of toxicities in acute myeloid leukemia patients with and without renal impairment treated with decitabine. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2018;24(4):290–298. doi: 10.1177/1078155217702213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caro J, Navada S.. Safety of anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation and MDS/AML complicated by thrombocytopenia: an unresolved challenge: can they be managed? A report of three cases and literature review. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(5):E112–E114. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arends J, Baracos V, Bertz H, et al. ESPEN expert group recommendations for action against cancer-related malnutrition. Clin Nutr. 2017;36(5):1187–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Söderberg KC, Jonsson F, Winqvist O, Hagmar L, Feychting M.. Autoimmune diseases, asthma and risk of haematological malignancies: a nationwide case-control study in Sweden. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(17):3028–3033. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou MH, Yang QM.. Association of asthma with the risk of acute leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Mol Clin Oncol. 2015;3(4):859–864. doi: 10.3892/mco.2015.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hindler K, Cleeland CS, Rivera E, Collard CD.. The role of statins in cancer therapy. Oncologist. 2006;11(3):306–315. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-3-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.