Abstract

Patient: Male, 67-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Myelophthisis • pneumonia • SARS-CoV2

Symptoms: Cough • desaturation • dynpnea • fever

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Infectious Diseases • Hematology

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

SARS-CoV-2 infection can persist in immunocompromised patients with hematological malignancies, despite antiviral treatment. This report is of a 67-year-old man with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), secondary hypogammaglobulinemia, and thrombocytopenia on maintenance therapy with ibrutinib, with persistent SARSCoV-2 infection unresponsive to antiviral treatment, including remdesivir, nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid), and tixagevimab/cilgavimab (Evusheld).

Case Report:

The patient was admitted to our hospital 3 times. During his first hospitalization, he was treated with 5-day course of remdesivir and intravenous steroids; however, antigen and molecular nasopharyngeal swabs were persistently positive, and he was discharged home. Due to respiratory worsening, he was rehospitalized, and despite being treated initially with tixagevimab/cilgavimab, and subsequently with a remdesivir course of 5 days, SARS-CoV-2 tests remained persistently positive. During his third hospital stay, our patient was subjected to combined therapy with remdesivir and nirmatrelvir/ritonavir for 5 days, obtaining a significant reduction of viral load at both antigen and molecular testing. As an ultimate attempt to achieve a negative status before discharge, a 10-day course of combined remdesivir and nirmatrelvir/ritonavir was administered, with a temporary reduction of viral load, followed by a sudden increase immediately after the discontinuation of Paxlovid. Due to worsening hematological disease and bacterial over-infections, the patient gradually worsened until death.

Conclusions:

This is an emblematic case of correlation between persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection and immunosuppression status in hematological hosts. In these patients, the viral load remains high, favoring the evolution of the virus, and the immunodeficiency makes it difficult to identify the appropriate therapeutic approach.

Keywords: Case Reports, COVID-19, Immunocompromised Host, Nirmatrelvir and Ritonavir Drug Combination, SARS-CoV-2, Remdesivir

Introduction

Immunocompromised patients bear a significant morbidity and mortality burden from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), developing a more severe disease with higher hospitalization rates than immunocompetent patients [1,2]. The immunosuppression state caused by the underlying disease and specific chemotherapy can determine the establishment of persistent viral replication [2]. Currently, there are several drugs available for the treatment of COVID-19. In detail, remdesivir, an intravenous antiviral, was the first drug authorized by the European Medicines Agency (EMA; June 25, 2020) for the treatment of pneumonia with respiratory failure, with a 5-day course [3]. Subsequently, oral antivirals, such as nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid), have been authorized, with the indication to treat patients who are at high risk of progression to severe COVID-19 [4]. In addition, since August 2022, the EMA has extended the use of combination of monoclonal antibodies tixagevimab-cilgavimab, previously authorized only for pre-exposure prophylaxis of SARS-CoV-2 infections, to the treatment of SARSCoV-2-positive patients at risk of a severe form of COVID-19 [5].

However, it has been shown that immunocompromised hosts, such as patients with hematological malignancies, present a high risk of clinical failure with the aforementioned common anti-SARS-CoV-2 treatments, supporting the establishment of a persistent infection [6].

In particular, persistent SARS-CoV-2 PCR positivity beyond 28 days is common in immunodeficient patients, with depletion of B cells and antibodies despite receipt of currently available treatments, and it represents the active replication of virus [7]. Therefore, during persistent infection, SARS-CoV-2 can evolve rapidly and give rise to significant mutations, including those implicated in worrying variants [8,9]. In relation to clinical and treatment difficulty, there are many cases described in the literature concerning the use of alternative therapeutic regimens based on antivirals and monoclonal antibodies in order to obtain negativization from SARS-CoV-2 (Table 1). Achieving this goal quickly is crucial to restart chemotherapy, which is often postponed to reduce immunosuppression [10] and reduce risk of hematological disease progression; on the other hand, it is necessary in order to decrease the risk of nocosomal infectious complications due to long hospitalization [1]. For instance, Chatzikonstantinou et al report a significant correlation between severe COVID-19 forms and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) therapy and suggest a possible protective role of specific therapies against an unfavorable evolution of SARS-CoV-2 infection, especially anti-leukemic treatment with Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors [11].

Table 1.

Representation of previous similar clinical cases described in the literature and involving different anti-SARS-CoV-2 therapeutic regimens associated with hematological disease and outcome.

| Author | Diagnosis | Disease related to Covid-19 | Oxygen therapy | Positive period | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Helleberg et al (2020) [22] | Chronic lymph. leukemia | Interstitial pneumonia | Yes | 65 days |

| Magyari et al (2022) [21] | B-cell depleted hematological patients | Interstitial pneumonia | Yes | Unknown | |

| 3 | Seki et al (2022) [23] | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Interstitial pneumonia | Yes | 60 days |

| 4 | Seki et al (2022) [23] | Multiple myeloma | Interstitial pneumonia | Yes | >30 days |

| 5 | Baldi et al (2022) [13] | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Interstitial pneumonia | Yes | 40 days |

| 6 | Graziani et al 2022) [14] | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Interstitial pneumonia | Yes | 55 days |

| 7 | Graziani et al (2022) [14] | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Interstitial pneumonia | Yes | >50 days |

| 8 | Ford et al (2022) [16] | B-cell acute lymph, leukemia | Interstitial pneumonia | Yes | 120 days |

| Anti-Covid-19 therapeutic regimens | Outcome | Immunosuppressive therapy | Anti-sars-CoV-2 vaccine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | – Remdesivir 10 days i.v. – Remdesivir 10 days i.v. + convalescent plasma i.v. |

Negative | Fludarabina, cyclophosphamide rituximab | Unknown |

| 2 | – Remdesivir 5 days i.v. – convalescent plasma i.v. |

Negative | Rituximab | Unknown |

| 3 | – Sotrovimab i.v. – Remdesivir 5 days i.v.+ Corticosteroids i.v. – Molnupiravir 5 days p.o. + gamma globulin i.v. + corticosteroids i.v. |

Death | CHOP, baricitinib | Yes |

| 4 | – Remdesivir 5 days + sotrovimab i.v. – Corticosteroids i.v. vMolnupiravir 5 days p.o. + sotrovimab i.v. |

Persistent positive | Lenalidomide, dexamethasone | Yes |

| 5 | – Sotrovimab i.v. – Remdesivir 7 days i.v. + Paxlovid 5 days p.o. + corticosteroids i.v. |

Negative | Rituximab | Yes |

| 6 | – Sotrovimab i.v. – Paxlovid 5 days p.o. |

Negative | Obinutuzumab | Unknown |

| 7 | – Sotrovimab i.v. – Remdesivir 5 days i.v. – Paxlovid 5 days p.o. |

Persistent positive | Rituximab | Unknown |

| 8 | – Sotrovimab i.v. – Remdesivir 10 days i.v. – Remdesivir 5 days i.v. + Paxlovid 10 days p.o. + Paxlovid 10 days p.o. (corticosteroids i.v.) |

Negative | Rituximab | Unknown |

This table presents some clinical cases described in the literature with explication of the following details: authors with bibliographic references, diagnosis of patient’s hematological disease, disease related to COVID-19, oxygen-therapy in relation to the presence of respiratory failure, positive time (expressed in days), anti-COVID-19 therapeutic regimens (remdesivir, sotrovimab, corticosteroids, convalescent plasma, nirmatrelvir/ritonavir as Paxlovid, molnupiravir) with reference to the mode of administration (i.v.: intravenous; p.o.: oral), outcome expressed as positivity or negativity to SARS-CoV-2 antigenic or molecular test, immunosuppressive therapy before starting anti-SARS-CoV-2 treatment, and anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (expressed as Yes, Not or Unknown).

In this report, we described the case of a 67-year-old man with CLL, secondary hypogammaglobulinemia, and thrombocytopenia on maintenance therapy with ibrutinib, with persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection unresponsive to different treatments, including remdesivir, nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid), and tixagevimab/cilgavimab (Evusheld).

Case Report

In June 2022, a 67-year-old man with stage IV CLL with TP53 mutation, thrombocytopenia (diagnosis 2014), and secondary hypogammaglobulinemia, vaccinated with mRNA vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 (4 doses, Comirnaty), presented a flu syndrome and tested positive for the first time to the nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) for SARS-CoV-2. In this context, therapy with ibrutinib was suspended and he received only symptomatological treatment.

He was first admitted to Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS on day 1 with COVID-19-related pneumonia and respiratory failure. On admission, he presented a blood count with hemoglobin level of 13.4 g/dL (reference range: 14–18 g/dL), platelet count of 162 000 cells/mcL (range: 150 000–450 000 cells/mcL), white blood cells (WBC) of 48 460/mcL (range 4000–10 000 cells/mcL), neutrophil count of 4650/mcL, lymphocyte count of 43 320/mcL, and SARS-CoV-2 antigenic test with cut off index (COI) of 5000 pg/mL (normal range <1 pg/mL, positive range 1–5000 pg/mL). Ibrutinib was stopped, and he was treated with intravenous (i.v.) dexamethasone for 10 days and remdesivir for 5 days, with no complications. During hospitalization, both antigen and molecular NPS were persistently positive, with a COI of 5000 pg/mL, and the cycle threshold (Ct) values were 15, 16, and 15 for envelope €, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP)/spike (S), and nucleoprotein (N) encoding genes. The serological test, which showed no significant virological response, was performed twice, with the following results: first test with IgG 2.4, IgA 0.1, and second test with IgG 6.4, IgA 0.2 (positivity cut off value 1.1). Sequencing analysis revealed the variant of concern BA.5.1.

After discharge, the patient remained persistently positive for SARS-CoV-2; therefore, it was not possible to restart therapy with ibrutinib and follow-up.

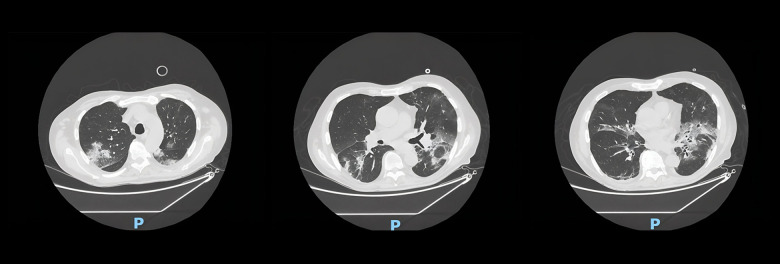

About 3 months after the first positive swab, he was read-mitted to our hospital for a complicated urinary tract infection caused by Escherichia coli, being still positive for SARSCoV-2 NPS (COI 5000 pg/mL) and blood count with emoglobin 7.5 g/dL, platelet count of 32 000/mcL, and WBC of 37 220/mcL (L 35 620/mcL). Due to the onset of worsening dyspnea, our patient required oxygen therapy. Chest computed tomography (CT) showed bilateral ground-glass interstitial disease, associated with features of organizational pneumonia (Figure 1). Due to the persistent positivity and the radiographic result, the role of COVID-19 on the pulmonary picture could not be excluded. Therefore, in accordance with the national guidelines available in August 2022 [5], he initially received tixagevimab/cilgavimab (300 mg+300 mg, intramuscular injection) on day 65 and subsequently a second remdesivir course of 5 days, associated with i.v. steroids and oxygen therapy. Progressively, there was a decreased oxygen requirement and an improvement of respiratory picture and general clinical condition. Nonetheless, he tested persistently positive in serial SARS-CoV-2 swabs and remained positive even after discharge. During this admission, the serological test presented the following results: IgG 5.6 and IgA 0.2.

Figure 1.

Three scans of chest computed tomography (CT) that appear from left to right following the longitudinal axis of the body. This CT, performed during the second hospitalization, shows bilateral ground-glass interstitial disease, associated with features of organizational pneumonia.

On day 110, he was readmitted for the third time with a high fever and respiratory failure due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia with pleural empyema. Contextually, he presented lymphocytosis, neutropenia (about 450/mcL) and worsening thrombocytopenia (around 10 000/mcL). The patient was treated accordingly and appropriately supported, and was still positive for SARS-CoV-2 (NPS COI of 5000 pg/mL). During his hospital stay, combination therapies were performed to clear SARS-CoV-2 infection. Therefore, a single patient authorization was obtained by the Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (AIFA) for a further 5-day treatment course of remdesivir, with nirmatrelvir/ritonavir. The patient showed a significant reduction of viral load at both antigen and molecular testing, with a COI of 88 pg/mL, results of molecular testing (Ct 27, 25, and 26 for E, RdRP/S, and N genes).

Nevertheless, being persistently positive on NPS, convalescent plasma infusion from a donor recently affected (within 1 month) by BA.5.1 was administered. The variant of concern was administered, but the subgenomic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 performed after convalescent plasma treatment revealed persistent active replicative infection.

As a further attempt to achieve negative status in the patient before discharge, another single patient special authorization was obtained by the AIFA for a 10-day course of combined remdesivir and nirmatrelvir/ritonavir. Even in this case, a significant viral load reduction (COI of 88 pg/mL) at both antigen and molecular testing (Ct 25, 24, and 25 for E, RdRP/S, and N genes) was seen, without swab negativity. During both courses of combined therapy, a sudden increase in viral load immediately after the discontinuation of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir was observed. Repeated sequencing confirmed the variant of concern BA.5.1, and serological testing yielded not significant results (IgG 8.7 and IgA 3.2).

On day 205, he was admitted for the fourth time with sepsis and respiratory failure due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia relapse and CLL progression, with myelophthisis. SARSCoV-2 NPS resulted positive, with a COI of 5000 pg/mL. As a salvage regimen, venetoclax target therapy was started, but the patient died on day 215.

The authorized diagnostic tests used to diagnose SARS-CoV-2 infection were viral nucleic acid detection by RT-PCR and an antigen test. It should be noted that, according to our hospital policy, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the RT-PCR test was replaced by the antigen test due to the high number of intra-hospital requests and the shorter execution times, compared with that of the RT-PCR test. The antigen test was also used to define the course of infection and obtained negativization. During the treatment of the reported patient, in exceptional cases, it was possible for the treating doctor to request both tests to identify the replicative level of the virus.

Subsequent nasopharyngeal swab samples obtained from the patient were analyzed for SARS-CoV-2 RNA. To evaluate the presence of SARS-CoV-2, RT-PCR testing was performed using the Seegene Allplex 2019-nCoV assay, and Ct values for 3 SARSCoV-2 genes, such as E, RdRP/S, and N genes, were determined.

For subgenomic SARS-CoV-2 RNA (ie, E-gene sgRNA) detection, we used an in-house RT-PCR assay, which was essentially in accordance with a method described elsewhere [12].

For antigen detection, we used the LUMIPULSE G SARS-CoV-2 Ag (Fujirebio, https://www.fujirebio.com) immunoassay, and SARS-CoV-2 sequencing analysis was performed using the COVIDSeq assay kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

Serological evaluation consisted of a semiquantitative determination of IgG IgA antibodies against S1 (included RBD) of the spike protein and was performed using SARS-CoV-2 IgG and IgA ELISAs (IgG and IgA values ≥1.1; Euroimmune, Lübeck, Germany).

Discussion

This report presents a case of persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection in a patient with hematological malignancy, underlining the difficulty of obtaining negativization by the use of different therapeutic regimens, including remdesivir, tixagevimab/cilgavimab, and the off-label use of remdesivir, associated with nirmatrelvir/ritonavir, due to the patient’s immunosuppression state.

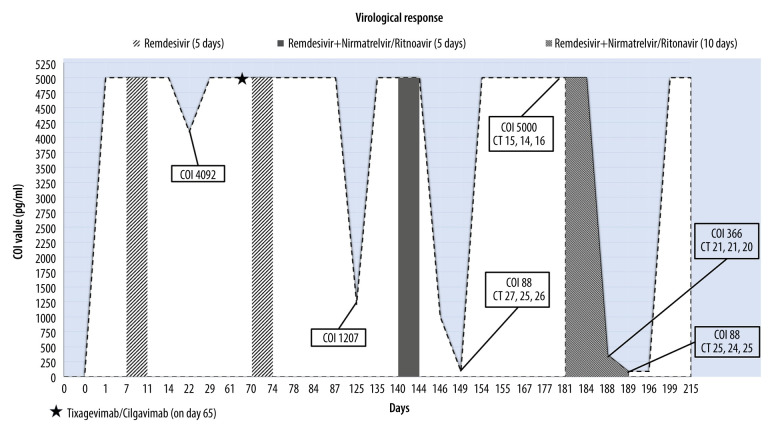

Analyzing the different therapeutic regimens and the course of the virological response as described in Figure 2, it is possible to note a significant reduction of the viral load following both combined therapy of remdesivir and nirmatrelvir/ritonavir. Moreover, the sudden increase of the viral load immediately after the interruption of the aforementioned therapy was evident (Figure 2). The off-label use of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir as a single prolonged antiviral therapy or in combination with other antivirals has shown symptom resolution and NPS negativity in some case reports, as presented in Table 1 [13–16]. In these cases, the negativization for SARSCoV-2 was achieved slowly (average value: 50 days), and the patients were affected by different hematological diseases than our patient, such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Focusing on the underlying disease, there is evidence in the literature describing the clearance of SARS-Cov-2 as being strongly dependent on the type of hematological disease, and underlying that, CLL patients are particularly prone to reduced viral clearance [17,18]. Our clinical case highlights the importance of immune impairment and subsequent hypogammaglobulinemia caused by the underlying hematological disease on the control of viral replication and the establishment of persistent infection despite vaccination, as some studies seem to suggest [19,20]. Precisely in order to improve the immunological status, our patient also underwent an infusion of convalescent plasma, but with negative results, and through some serological tests, we observed that he never developed an adequate virological response. In this regard, an effective strategy described in the literature is to combine convalescent plasma with antiviral therapy, as in the case of Magyari et al, and in the case of Helleberg et al, of a SARS-CoV-2-positive patient with CLL, while in our case, antiviral therapy and convalescent plasma were administered consecutively [21,22].

Figure 2.

The virological response is expressed with the cut off index (COI) on the Y axis. Significant values are reported in the tables, with COI value and cycle threshold (Ct) values. This figure shows the trend of the virological response during 3 different anti-SARS-CoV-2 therapeutic regimens to which our immunocompromised patient was subjected. In chronological order, the following were administered: a 5-day cycle of remdesivir twice in a 2-month period, a single administration of tixagevimab/cilgavimab, a cycle of combined therapy of remdesivir and nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid), and finally, a 10-day cycle of remdesivir and nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid). The graph shows significant reduction in viral load following a combined or prolonged regimen of remdesivir and nirmatrelvir/ritonavir.

In the literature, there are also clinical cases in which different anti-SARS-CoV-2 treatment regimens have failed, some of which concern patients who developed bone marrow suppression and inadequate virological response after long-term hospitalization and corticosteroid therapy for COVID-19 [23]. Also, in the case of our patient, the above issues played a role in the negative outcome. In fact, the persistent infection prolonged hospitalization and corticosteroid treatment, resulting in the discontinuation of CLL therapy, and witnessed a progressive worsening of hematological disease and the onset of nosocomial pneumonia that led to the patient’s death.

Conclusions

The typical immunosuppression status of the patient with hematological diseases is the basis for the establishment of SARSCoV-2 persistent infection that becomes difficult to treat even using combined or prolonged therapies, as in our case. In view of this, anti-SARS-CoV-2 therapeutic strategies in hematological patients should be deepened not only on the side of antiviral action but especially immunological.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their thanks to all technical and caregiving personnel of Policlinico Agostino Gemelli for supporting the patient and the authors during the case report production.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher

Institution Where Work Was Done

Catholic University of Sacred Heart, Rome, Italy.

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity

All figures submitted have been created by the authors who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

References:

- 1.Belsky JA, Tullius BP, Lamb MG, et al. COVID-19 in immunocompromised patients: A systematic review of cancer, hematopoietic cell and solid organ transplant patients. J Infect. 2021;82(3):329–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertini CD, Jr, Khawaja F, Sheshadri A. Coronavirus disease-2019 in the immunocompromised host. Clin Chest Med. 2023;44(2):395–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2022.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Italian Medicines Agency Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (AIFA) Medicines usable for treatment of COVID-19 disease. available from https://www.aifa.gov.it/en/aggiornamento-sui-farmaci-utilizzabili-per-iltrattamento-della-malattia-covid19.

- 4.Italian Medicines Agency Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (AIFA) Use of oral antivirals for COVID-19. available from: https://www.aifa.gov.it/en/uso-degli-antivirali-orali-per-covid-19.

- 5.Italian Medicines Agency Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (AIFA) Use of Monoclonal Antibodies for COVID-19. available from: https://www.aifa.gov.it/en/uso-degli-anticorpi-monoclonali.

- 6.Sun J, Zheng Q, Madhira V, et al. Association Between Immune Dysfunction and COVID-19 Breakthrough Infection After SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(2):153–62. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.7024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan M, Linn MMN, O’Hagan T, et al. Persistent SARS-CoV-2 PCR positivity despite anti-viral treatment in immunodeficient patients. J Clin Immunol. 2023;43(6):1083–92. doi: 10.1007/s10875-023-01504-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hettle D, Hutchings S, Muir P, Moran E, COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) consortium Persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection in immunocompromised patients facilitates rapid viral evolution: Retrospective cohort study and literature review. Clin Infect Pract. 2022;16:100210. doi: 10.1016/j.clinpr.2022.100210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corey L, Beyrer C, Cohen MS, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants in patients with immunosuppression. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(6):562–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2104756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laracy JC, Kamboj M, Vardhana SA. Long and persistent COVID-19 in patients with hematologic malignancies: from bench to bedside. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2022;35(4):271–79. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chatzikonstantinou T, Kapetanakis A, Scarfò L, et al. COVID-19 severity and mortality in patients with CLL: An update of the international ERIC and Campus CLL study. Leukemia. 2021;35(12):3444–454. doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01450-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casetti IC, Borsani O, Rumi E. COVID-19 in patients with hematologic diseases. Biomedicines. 2022;10(12):3069. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10123069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baldi F, Dentone C, Mikulska M, et al. Case report: Sotrovimab, remdesivir and nirmatrelvir/ritonavir combination as salvage treatment option in two immunocompromised patients hospitalized for COVID-19. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023;9:1062450. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.1062450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graziani L, Gori L, Manciulli T, et al. Successful use of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir in immunocompromised patients with persistent and/or relapsing COVID-19. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2023;78(2):555–58. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkac433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun F, Lin Y, Wang X, et al. Paxlovid in patients who are immunocompromised and hospitalised with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(9):1279. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00430-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ford ES, Simmons W, Karmarkar EN, et al. Successful treatment of prolonged, severe coronavirus disease 2019 lower respiratory tract disease in a B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia patient with an extended course of remdesivir and nirmatrelvir/ritonavir. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(5):926–29. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avanzato VA, Matson MJ, Seifert SN, et al. Case study: Prolonged infectious SARS-CoV-2 shedding from an asymptomatic immunocompromised individual with cancer. Cell. 2020;183(7):1901–1912.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritchie AI, Singanayagam A. Immunosuppression for hyperinflammation in COVID-19: A double-edged sword? Lancet. 2020;395(10230):1111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30691-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen Y, Freeman JA, Holland J, et al. COVID-19 vaccine failure in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and monoclonal B-lymphocytosis; humoural and cellular immunity. Br J Haematol. 2022;197(1):41–51. doi: 10.1111/bjh.18014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D’Abramo A, Vita S, Maffongelli G, et al. Clinical management of patients with B-cell depletion agents to treat or prevent prolonged and severe SARS-COV-2 infection: Defining a treatment pathway. Front Immunol. 2022;13:911339. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.911339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magyari F, Pinczés LI, Páyer E, et al. Early administration of remdesivir plus convalescent plasma therapy is effective to treat COVID-19 pneumonia in B-cell depleted patients with hematological malignancies. Ann Hematol. 2022;101(10):2337–45. doi: 10.1007/s00277-022-04924-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Helleberg M, Niemann CU, Moestrup KS, et al. Persistent COVID-19 in an immunocompromised patient temporarily responsive to two courses of remdesivir therapy. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(7):1103–7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seki M, Hashimoto K, Kondo N, et al. Sequential treatment by antiviral drugs followed by immunosuppressive agents for COVID-19 patients with hematological malignancy. Infect Drug Resist. 2022;15:7117–24. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S393198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]