Abstract

The current study was assigned to determine the putative preventive role of vinpocetine (VIN) in cervical hyperkeratosis (CHK) in female rats. Estradiol Benzoate (EB) was utilized in a dose f (60 μg/100 g, i.m) three times/week for 4 weeks to induce cervical hyperkeratosis. VIN was administered alone in a dose of (10 mg/kg/day, orally) for 4 weeks and in the presence of EB. Levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), total nitrites (NOx), reduced glutathione (GSH), interleukin-18 (IL-18), IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) were measured in cervical tissue. The expression of NLRP3/GSDMD/Caspase-1, and SIRT1/Nrf2 was determined using ELISA. Cervical histopathological examination was also done. EB significantly raised MDA, NOx, TNF-α, IL-18, IL-1β, and GSDMD and up-regulated NLRP3/Caspase-1 proteins. However, GSH, SIRT1, and Nrf2 levels were reduced in cervical tissue. VIN significantly alleviates all biochemical and histopathological abnormalities. VIN considerably mitigates EB-induced cervical hyperkeratosis via NLRP3-induced pyroptosis and SIRT1/Nrf2 signaling pathway.

Keywords: Hyperkeratosis, Estradiol, Vinpocetine, NLRP3, Nrf2

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Cancer

Introduction

The presence of a thicker keratin layer on the surface of stratified squamous epithelium is known as cervical hyperkeratosis (CHK)1,2. CHK is typically associated with inflammation, trauma, or infection, and it frequently affects women who use diaphragms3. A benign structural change of the cervical squamous epithelium, CHK may mask dysplastic lesions and complicate a reliable colpo-cytological examination4.

Estrogen strongly affects the uterine cervix5,6. With rising estrogen levels throughout the monthly cycle, cervical epithelial cells divide and multiply, producing hyperplastic epithelium without pathogenic alterations. High dosages or long-term use of estrogen can lead to cervical lesions as CHK7. Animal models exposed to estradiol benzoate (EB) displayed characteristics that might be indicative of stromal invasion and cervical cancer3,8. So, EB was utilized in the current study to induce CHK in female rats.

Pyroptosis is a highly inflammatory form of cell death that is closely linked to oxidative stress and the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. This process plays a crucial role in the initiation and amplification of inflammatory responses, with important implications for the understanding and treatment of various pathological conditions9.

Inflammation in the uterus is brought on by exposure to unopposed estrogen10. Proinflammatory cytokines and inflammatory mediators contribute to uterine hyperplastic alterations and carcinoma11. This can boost estrogen production and disturb the estrogen-progestogen balance, potentially leading to carcinogenesis12. Rapid cell division brought on by inflammation raises the concentration of free radicals, which damages DNA and induces oxidative stress12,13. Numerous investigations have revealed a close correlation between the inflammatory response triggered by estrogen and the activation of the NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, which in turn activates inflammatory mediators including IL1β, IL18, and TNF-α14–16. Cervical cancer is also strongly associated with up-regulation of NLRP317.

The cytoprotective properties of nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like-2 factors (Nrf2) against oxidative stress and inflammation play a vital role in the removal of free radicals18,19. Since Nrf2 prevents normal cells from transforming, it is regarded as a trustworthy marker in cervical cancer20,21. Additionally, Silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog 1 (SIRT1), a member of the large Sirtuin family, regulates stress responses and cell survival through its histone deacetylase activity22. The expression SIRT1 is significantly correlated with endometrial cancer risk factors. Targeting SIRT1 is thought to be an effective way to treat cervical cancer23.

Vinpocetine (VIN) is a synthetically produced derivative of the periwinkle plant Vinca minor's alkaloid vincamine24. Around 1978, VIN was first created and promoted in Hungary. For the prevention and treatment of stroke, senile dementia, and memory problems, VIN has been utilized in numerous Asian and European countries. Additionally, a variety of brands of nutritional supplements with VIN in them are being offered all over the world. Previous studies have proven beyond doubt that vinpocetine has an excellent safety profile, consequently, increasing efforts have been put into exploring the novel therapeutic effects and mechanism of actions of vinpocetine in various cell types and disease models25. VIN demonstrated antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties in a variety of animal studies including hepatic and renal ischemia–reperfusion injury26,27, neurodegeneration induced by aluminum chloride28, and cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury29. Furthermore, VIN downregulated the NLRP3 inflammasome, decreased inflammatory mediators, and provided protection against ischemic stroke30 and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis31 as well as its potential to mitigate pancreatitis via SIRT1/ Nrf2/TNF-α signaling pathway32. Based on these findings, it is possible to hypothesize that VIN via suppression of inflammation, might be effective in attenuating EB-induced CHK in female rats.

Materials and methods

Drugs and chemicals

VIN was obtained from Amirya Co., Egypt. Estradiol Benzoate (EB) powder was obtained from Misr Co., Egypt. The present study employed the highest commercially available analytical grade for all other chemical reagents.

Animals and experimental design

Female Wistar albino rats weighing 180–210 g and aged 8–10 weeks were procured from Egypt's National Research Centre in Cairo. Before commencing the experiment, rats were acclimatized in their cages (6 rats per cage) for 1 week in a regular light–dark cycle with unrestricted access to tap water and normal food. Our experimental protocol received permission from the Study Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Minia University (Approval number: 393:2022), and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant scientific guidelines and regulations. The current study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Twenty-four Rats were randomly divided into the following 4 groups (n = 6):

Group I (Control): rats were given carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) orally and olive oil intramuscular injection (i.m.) three times/week for a duration of 4 weeks3.

Group II (VIN): rats administered VIN (10 mg/kg/day, orally)33,34 suspended in CMC and i.m injection of olive oil three times/week for a duration of 4 weeks.

Group III (EB): rats administered EB in a dose of (60 μg/100 g, i.m) three times/week for a duration of 4 weeks3.

Group IV (EB/VIN): rats received VIN (10 mg/kg/day, orally)33,34 plus EB in a dose of (60 μg/100 g, i.m) three times/week for a duration of 4 weeks3.

Sample collection

At the close of the experiment, rats received an i.p. injection of urethane (25% in a dose of 1.6 g/kg)35. Rats were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and their cervices were removed and cleansed with saline to eliminate any blood. A portion was kept for histological examination. The other parts were split into two portions, the first of which was immediately frozen at -80°C until utilized for western blot analysis. For measuring biochemical parameters, the second portion was homogenised with phosphate buffer (0.01 M, pH 7.4; 20% w/v) (tissue weight (g): phosphate buffer (mL) volume = 1:5)36, then the homogenate was centrifuged for 15 min at 5000 rpm, and the supernatant was kept at – 80 °C.

Biochemical investigations

Assessment of oxidative stress parameters

Cervical reduced glutathione (GSH); (Cat. No.: GR 25 11), and malondialdehyde (MDA); (Cat. No.: MD 25 29) were measured by kits provided by Biodiagnositic, Giza, Egypt. Total nitrite/nitrate (NOx) was determined using the Griess reaction between nitrite and a mixture of naphthyl ethylenediamine and sulfanilamide; the NO level was detected at 540 nm37.

Assessment of inflammatory markers

Cervical TNF-α (Cat. No.: E-EL-R0019), IL-18 (Cat. No.: E-EL-R0567), and IL-1β (Cat. No.: E-EL-R0012), were evaluated using ELISA kits (Elabscience, Houston, TX, USA) following the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Assessment of SIRT1/Nrf2 signaling pathway

Cervical SIRT1; (Cat. No.: MBS2600246), and Nrf2; (Cat. No.: MBS012148) were measured using ELISA kits provided by MyBioSource, San Diego, California, USA according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Assessment of NLRP3/GSDMD/Caspase 1 signaling pathway

Cervical NLRP3 (Cat. No.: ab277086, Abcam, UK), GSDMD; (Cat. No.: MBS2705517, MyBioSource, San Diego, California, USA), and caspase 1 (Cat. No.: E-EL-R0371, Elabscience, Houston, TX, USA) were evaluated using ELISA kits following the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Histopathological study

The cervices of the female rats were removed, processed, and embedded in paraffin after being submerged in a 10% formalin solution for 24 h. With a microtome, cross-sections 5 μm thick were cut. Hematoxylin–eosin stain was applied to these tissue sections, and they were examined using an Olympus light microscope for a histological assessment.

Statistical analysis

The mean ± SEM was used to present all the data. The Tukey-Kramar test was conducted after a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine the data. Significant P values were defined as those less than 0.05. The statistical analysis was carried out with GraphPad Prism®, Version 10.00 for Windows.

Results

Impact of VIN on oxidative stress parameters in cervical tissue

As presented in Table 1, EB significantly increased MDA and NO and reduced GSH, as compared to control group. On the other hand, VIN when co-administered with EB, significantly reduced both MDA and NOx and increased GSH, relative to EB groups.

Table 1.

Impact of VIN on oxidative stress parameters.

| Groups | Cervical MDA (nmol/g tissue) | Cervical GSH (nmol/g tissue) | Cervical NOx (µmol/g tissue) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 12.1 ± 0.68 | 54.3 ± 2.52 | 47.7 ± 2.82 |

| VIN | 11.7 ± 0.73 | 51.8 ± 1.53 | 48.9 ± 1.80 |

| EB | 35.7 ± 2.33### | 28.9 ± 2.42### | 100 ± 3.26### |

| EB/VIN | 12.1 ± 0.85*** | 53.0 ± 2.55*** | 51.0 ± 3.96*** |

Results represent the mean ± SEM (n = 6), where ###p < 0.001, relative to control group, and ***p < 0.001 relative to EB group. VIN; Vinpocetine, EB; Estradiol-benzoate.

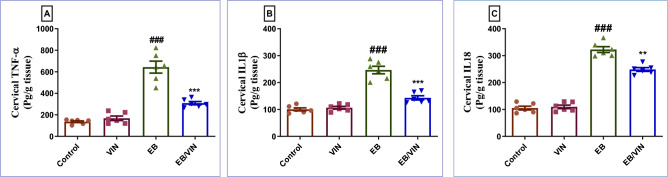

Impact of VIN on cervical inflammatory markers

In group received EB, TNF-α, IL-18, and IL-1β were increased significantly, relative to control group. In contrast, in EB/VIN group, a significant reduction in TNF-α, IL-18, and IL-1β occurred, as compared to EB group (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Cervical tissue levels of TNF-α (A), IL1β (B), and IL18 (C). Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6). Where ###p < 0.001, relative to control group, **p < 0.01 relative to EB group and ***p < 0.001 relative to EB group. VIN; Vinpocetine, EB; Estradiol-benzoate, TNF-α; Tumor necrosis factor-alpha, IL18; Interleukin 18, and IL1β; Interleukin 1β.

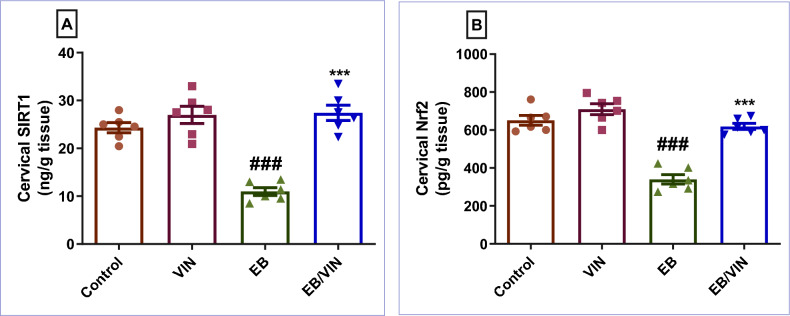

Impact of VIN on cervical SIRT1/Nrf2 signaling pathway

As presented in Fig. 2, EB significantly reduced SIRT1 and Nrf2, relative to control group. However, VIN when co-administered with EB, significantly reversed the condition as it increased both SIRT1 and Nrf2, as compared to EB group.

Figure 2.

Cervical tissue levels of SIRT1 (A), and Nrf2 (B). Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6). Where ###p < 0.001, relative to control group, and ***p < 0.001 relative to EB group. VIN; vinpocetine, EB; Estradiol-benzoate, SIRT1; Silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog 1, and Nrf2; Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2.

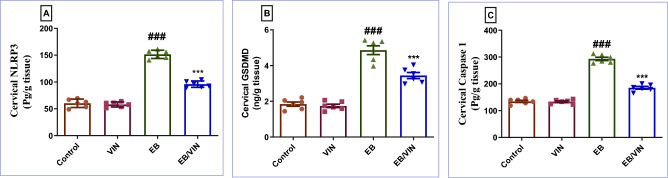

Impact of VIN on cervical NLRP3/GSDMD/Caspase 1 signaling pathway

In the EB group, NLRP3, GSDMD, and caspase-1 levels were all considerably increased, in relation to the control group. In contrast to EB group, In EB/VIN group, a significant decrease was observed in NLRP3, GSDMD, and caspase 1 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Cervical tissue levels of NLRP3 (A), GSDMD (B), and Caspase 1 (C). Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6). Where ###p < 0.001, relative to control group, and ***p < 0.001 relative to EB group. VIN; vinpocetine, EB; Estradiol-benzoate, and NLRP3 = NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3.

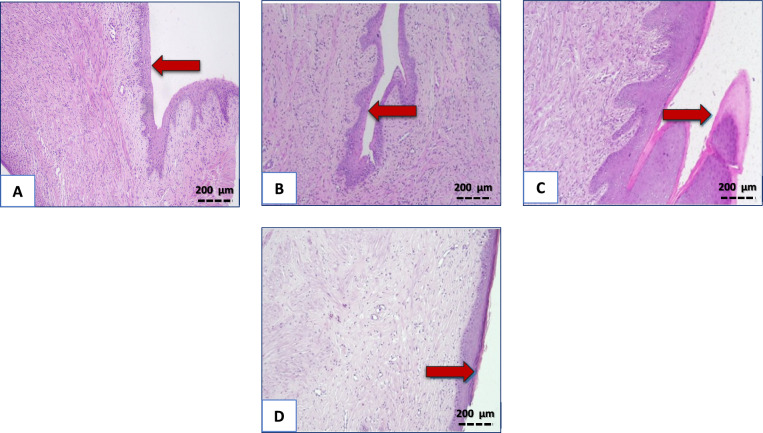

Histopathological results

Sections examined from control and VIN groups showed normal cervices lined by stratified squamous non keratinized epithelium. In contrast, cervices of group received EB showed marked and diffuse areas of hyperkeratosis. On the other hand, group in which VIN was co-administered with EB, only mild focal areas of hyperkeratosis were noticed (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Impact of VIN on histopathological picture of rats’ cervices. Control group, and VIN group (A,B) displaying normal cervices lined by stratified squamous non keratinized epithelium. EB group (C) showing diffuse and marked cervical hyperkeratosis. EB + VIN group (D) displaying only mild and focal areas of hyperkeratosis, (×200). EB; Estradiol-benzoate, VIN; Vinpocetine.

Discussion

CHK is a prevalent gynecological condition caused by excessive administration of estrogen5.

Over-administration of estrogen contributes significantly to CHK and cervical cancer by inducing cytokines, oxidative stress, and the generation of free radicals10. Estrogen administration, particularly when combined with other substantial risk factors such as multiparity and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, can lead to cervical cancer38. In the current study, EB used as a positive control drug that induced CHK as mentioned in previous studies and confirmed by a typical histopathological alterations3,39. The development of CHK is heavily influenced by oxidative stress3. We investigated oxidative stress markers such as MDA, NOX, and GSH to assess the oxidative stress effect of EB therapy. The negative impacts of EB were demonstrated by a considerable rise in cervical MDA, and NOx, as well as a significant decrease in cervical GSH relative to the control group. Co-administration of VIN with EB in the current study significantly improved oxidative stress status as shown by reduction in MDA, NOx and increase in GSH. This result indicates an antioxidant effect of vinpocetine in CHK. This is also documented by recent Fattori et al., study showing that vinpocetine has a considerable oxidative stress ameliorating effect40.

Earlier studies demonstrated that EB administration can trigger CHK by stimulating inflammation and releasing inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, and IL1β3,41,42.Our study showed a significant rise in TNF-α, IL18, and IL1β levels in the EB group. Fortunately, VIN significantly reduced TNF-α, IL18, and IL1β levels, demonstrating its protective effect against EB-induced CHK, which is in line with previous studies that reported the antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties of VIN in several animal models, including acute kidney injury, lung inflammation caused by lipopolysaccharide, otitis media in mice, and inflammatory pain43–45.

To acquire a better understanding of the mechanism of VIN's protective impact against EB-induced CHK, NLRP3, Caspase-1, and GSDMD levels were investigated. NLRP3 (nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain receptors) are intracellular proteins that play a function in mammalian immunity and are highly expressed in cervical carcinoma17. To form an inflammasome complex, NLRP3 binds to ASC and subsequently activates procaspase 1. Mature IL-1β and IL-18 are produced from pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 by active caspase1, However, caspase1 also encourages GSDMD to become cleaved GSDMD, which causes the plasma membrane to open up significantly and starts the process of pyroptosis46. Our study showed a significant rise in cervical NLRP3, Caspase-1, and GSDMD levels in the EB group demonstrating that NLRP3 inflammasome is strongly associated with CHK. Conversely, VIN resulted in a markedly reduced expression of NLRP3, Caspase-1, and GSDMD. This is consistent with the findings of Dong Han et al. (2020), whereby the NLRP3 signaling pathway was suggested as a plausible explanation for VIN's ability to mitigate ischemic stroke47.

In the same vein, EB injection induced histological alterations, characterized by prominent hyperkeratosis with a thicker keratin layer on the surface of stratified squamous epithelium with underlying significant stromal inflammatory cell infiltration. These findings are in line with previous studies48,49. In EB/VIN group, there is marked improvement of these histopathological alterations. As only mild focal areas of hyperkeratosis were noticed. Additionally, the improvement of histopathological aberrations was supported by the downregulation of cervical inflammatory cytokines, NLRP3, caspase 1, and oxidative stress markers.

To provide more insight into the potential protective mechanism of VIN against EB-induced CHK, an evaluation of the SIRT1/Nrf2 signaling pathway was conducted. As many of its downstream target genes and enzymes are in charge of avoiding or reversing intracellular redox imbalances, Nrf2 is regarded as a master regulator of the antioxidant response50,51. Well-known stress response protein SIRT1 is essential for a variety of cellular and physiological processes including cell damage, and mitochondrial biogenesis and its expression is correlated with endometrial cancer23,52. Moreover, some investigations have suggested that SIRT1 may activate Nrf2 in order to exhibit its antioxidative actions53,54. Earlier studies demonstrated that downregulating Nrf2 is associated with NLRP3 activation and release of inflammatory mediators supporting the connection between the two investigated pathways in the current work55,56. According to the results of the current investigation, the SIRT1 and Nrf2 levels were lower in the EB-treated group. Inversely, VIN increased SIRT1 and Nrf2 expression. Additionally, these results are consistent with previous research showing the stimulatory effect of VIN on SIRT1/Nrf2 in acute pancreatitis produced by l-arginine32.

Conclusion

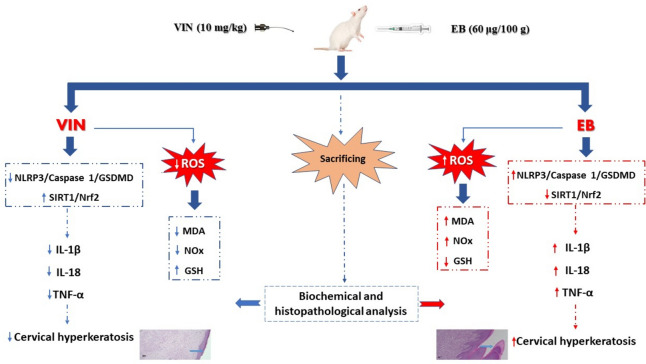

In the current study, collectively, VIN antagonized oxidative stress, and inflammation induced by EB as evidenced by reduction in MDA, NOx, TNF-α, IL18, and IL1β with increase in GSH and via stimulation of SIRT1/Nrf2 signaling pathway and subsequent inhibition of NLRP3/Caspase 1/ GSDMD signaling pathway as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

Graph outlining the mechanism of EB-induced CHK and the potential protective effect of VIN. One of the authors, Ehab E. Sharata, used Microsoft PowerPoint to create this graph.

Author contributions

Remon Roshdy Rofaeil, Reham H. Mohyeldin, Ehab E. Sharata, Walaa Yehia Abdelzaher, Hany Essawy and Osama A. Ibrahim participated in conceptualization, performing the experiments, data analysis, editing, and revising the manuscript. Mina Ezzat Attya performed and wrote the pathological examination. All the authors read, revised, and approved the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rosa, M. & Moore, G. Epidermalization of cervix and vagina: An unsolved dilemma. J. Low Genit. Tract. Dis.12(3), 217–219 (2008). 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318162013e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng, L. & Bostwick, D. G. Essentials of Anatomic Pathology (Springer, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Refaie, M. M. M. & El-Hussieny, M. Diacerein inhibits estradiol-benzoate induced cervical hyperkeratosis in female rats. Biomed. Pharmacother.95, 223–229 (2017). 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.08.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chogovadze, N., Jugeli, M., Gachechiladze, M. & Burkadze, G. Cytologic, colposcopic and histopathologic correlations of LSIL and HSIL in reproductive and menopausal patients with hyperkeratosis. Georgian Med. News217, 22–26 (2013). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung, S. H., Franceschi, S. & Lambert, P. F. Estrogen and ERalpha: Culprits in cervical cancer?. Trends Endocrinol.zA Metab.21(8), 504–511 (2010). 10.1016/j.tem.2010.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baggs, R. B., Miller, R. K. & Odoroff, C. L. Carcinogenicity of diethylstilbestrol in the Wistar rat: Effect of postnatal oral contraceptive steroids. Cancer Res.51(12), 3311–3315 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brake, T. & Lambert, P. F. Estrogen contributes to the onset, persistence, and malignant progression of cervical cancer in a human papillomavirus-transgenic mouse model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA102(7), 2490–2495 (2005). 10.1073/pnas.0409883102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koudstaal, J., Hardonk, M. J. & Hadders, H. N. The development of induced cervicovaginal carcinoma in intact and estrogen-treated, castrated mice studied by histochemical and enzyme histochemical methods. Cancer Res.26(9), 1943–1953 (1966). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang, Q. et al. Pyroptosis: A pro-inflammatory type of cell death in cardiovascular disease. Clin. Chim. Acta510, 62–72 (2020). 10.1016/j.cca.2020.06.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith, H. O. et al. The clinical significance of inflammatory cytokines in primary cell culture in endometrial carcinoma. Mol. Oncol.7(1), 41–54 (2013). 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balkwill, F. & Coussens, L. M. An inflammatory link. Nature431(7007), 405–406 (2004). 10.1038/431405a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Modugno, F., Ness, R. B., Chen, C. & Weiss, N. S. Inflammation and endometrial cancer: A hypothesis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev.14(12), 2840–2847 (2005). 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jabbour, H. N., Sales, K. J., Catalano, R. D. & Norman, J. E. Inflammatory pathways in female reproductive health and disease. Reproduction138(6), 903–919 (2009). 10.1530/REP-09-0247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu, S. G. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome activation by estrogen promotes the progression of human endometrial cancer. Onco Targets Ther.12, 6927–6936 (2019). 10.2147/OTT.S218240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng, T. et al. Pyroptosis: The dawn of a new era in endometrial cancer treatment. Front. Oncol.13, 1277639 (2023). 10.3389/fonc.2023.1277639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng, X. et al. NLRP3 promotes endometrial receptivity by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition of the endometrial epithelium. Mol. Hum. Reprod.10.1093/molehr/gaab056 (2021). 10.1093/molehr/gaab056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandes, F. P. et al. Cervical carcinoma induces NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1ß release in human peripheral blood monocytes affecting patients’ overall survival. Clin. Transl. Oncol.25(11), 3277–3286 (2023). 10.1007/s12094-023-03241-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmed, S. A. & Mohammed, W. I. Carvedilol induces the antiapoptotic proteins Nrf(2) and Bcl(2) and inhibits cellular apoptosis in aluminum-induced testicular toxicity in male Wistar rats. Biomed. Pharmacother.139, 111594 (2021). 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohyeldin, R. H. et al. LCZ696 attenuates sepsis-induced liver dysfunction in rats; the role of oxidative stress, apoptosis, and JNK1/2-P38 signaling pathways. Life Sci.334, 122210 (2023). 10.1016/j.lfs.2023.122210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdelzaher, W. Y. et al. Potential induction of h yperkeratosis in r ats’c ervi by gentamicin via induction of oxidative s tress, i nflammation and a poptosis. Hum. Exp. Toxicol.43, 09603271231225744 (2024). 10.1177/09603271231225744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma, J. Q. et al. Functional role of NRF2 in cervical carcinogenesis. PLoS ONE10(8), e0133876 (2015). 10.1371/journal.pone.0133876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghazipour, A. M. et al. Cyclosporine A induces testicular injury via mitochondrial apoptotic pathway by regulation of mir-34a and sirt-1 in male rats: The rescue effect of curcumin. Chem. Biol. Interact.327, 109180 (2020). 10.1016/j.cbi.2020.109180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen, J., Chen, H. & Pan, L. SIRT1 and gynecological malignancies (review). Oncol. Rep.10.3892/or.2021.7994 (2021). 10.3892/or.2021.7994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gulyás, B. et al. Drug distribution in man: A positron emission tomography study after oral administration of the labelled neuroprotective drug vinpocetine. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging29(8), 1031–1038 (2002). 10.1007/s00259-002-0823-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bönöczk, P. et al. Role of sodium channel inhibition in neuroprotection: Effect of vinpocetine. Brain Res. Bull.53(3), 245–254 (2000). 10.1016/S0361-9230(00)00354-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaki, H. F. & Abdelsalam, R. M. Vinpocetine protects liver against ischemia–reperfusion injury. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol.91(12), 1064–1070 (2013). 10.1139/cjpp-2013-0097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Azouz, A. A., Hersi, F., Ali, F. E., Hussein Elkelawy, A. M. & Omar, H. A. Renoprotective effect of vinpocetine against ischemia/reperfusion injury: Modulation of NADPH oxidase/Nrf2, IKKβ/NF-κB p65, and cleaved caspase-3 expressions. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol.36(7), e23046 (2022). 10.1002/jbt.23046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdel-Salam, O. M. et al. Effect of piracetam, vincamine, vinpocetine, and donepezil on oxidative stress and neurodegeneration induced by aluminum chloride in rats. Compar. Clin. Pathol.25, 305–318 (2016). 10.1007/s00580-015-2182-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song, W. et al. Vinpocetine reduces cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury through inhibition of NF–κB pathway and activation of Nrf2/ARE pathway in rats. Int. Urol. Nephrol.52, 1389–1401 (2020). 10.1007/s11255-020-02485-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han, D. et al. Vinpocetine attenuates ischemic stroke through inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome expression in mice. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol.77(2), 208 (2021). 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu, Y. et al. Vinpocetine represses the progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice by mediating inflammasome components via NF-κB signaling. Gastroenterología y Hepatología47, 366–376 (2023). 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2023.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdelzaher, W. Y. et al. Vinpocetine ameliorates l-arginine induced acute pancreatitis via Sirt1/Nrf2/TNF pathway and inhibition of oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis. Biomed. Pharmacother.133, 110976 (2021). 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaki, H. F. & Abdelsalam, R. M. Vinpocetine protects liver against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol.91(12), 1064–1070 (2013). 10.1139/cjpp-2013-0097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hou, B. et al. Neuroprotective effects of vinpocetine against ischemia-reperfusion injury via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathway. Neuroscience526, 74–84 (2023). 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2023.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdelnaser, M., Alaaeldin, R., Attya, M. E. & Fathy, M. Hepatoprotective potential of gabapentin in cecal ligation and puncture-induced sepsis; targeting oxidative stress, apoptosis, and NF-kB/MAPK signaling pathways. Life Sci.320, 121562 (2023). 10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohyeldin, R. H. et al. Aprepitant boasted a protective effect against olanzapine-induced metabolic syndrome and its subsequent hepatic, renal, and ovarian dysfunction; Role of IGF1/p-AKT/FOXO1 and NFκB/IL-1β/TNF-α signaling pathways in female Wistar albino rats. Biochem. Pharmacol.221, 116020 (2024). 10.1016/j.bcp.2024.116020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Söğüt, S. et al. Changes in nitric oxide levels and antioxidant enzyme activities may have a role in the pathophysiological mechanisms involved in autism. Clin. Chim. Acta331(1–2), 111–117 (2003). 10.1016/S0009-8981(03)00119-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sugisawa, A. et al. Cytological characteristics of premalignant cervical epithelial lesions in postmenopausal women based on endocrine indices and parakeratosis. Menopause30(2), 193–200 (2023). 10.1097/GME.0000000000002125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones, L. A., Verjan, R. P., Mills, K. T. & Bern, H. A. Prevention by progesterone of cervicovaginal lesions in neonatally estrogenized BALB/c mice. Cancer Lett.23(2), 123–128 (1984). 10.1016/0304-3835(84)90144-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fattori, V. et al. Vinpocetine reduces diclofenac-induced acute kidney injury through inhibition of oxidative stress, apoptosis, cytokine production, and NF-κB activation in mice. Pharmacol. Res.120, 10–22 (2017). 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.12.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lian, Z. et al. Preventive effects of isoflavones, genistein and daidzein, on estradiol-17beta-related endometrial carcinogenesis in mice. Jpn. J. Cancer Res.92(7), 726–734 (2001). 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2001.tb01154.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Niwa, K. et al. Inhibitory effects of toremifene on N-methyl-N-nitrosourea and estradiol-17beta-induced endometrial carcinogenesis in mice. Jpn. J. Cancer Res.93(6), 626–635 (2002). 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2002.tb01300.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jeon, K. I. et al. Vinpocetine inhibits NF-kappaB-dependent inflammation via an IKK-dependent but PDE-independent mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA107(21), 9795–9800 (2010). 10.1073/pnas.0914414107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruiz-Miyazawa, K. W. et al. Vinpocetine reduces lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory pain and neutrophil recruitment in mice by targeting oxidative stress, cytokines and NF-κB. Chem. Biol. Interact.237, 9–17 (2015). 10.1016/j.cbi.2015.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee, J. Y. et al. Vinpocetine inhibits Streptococcus pneumoniae-induced upregulation of mucin MUC5AC expression via induction of MKP-1 phosphatase in the pathogenesis of otitis media. J. Immunol.194(12), 5990–5998 (2015). 10.4049/jimmunol.1401489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khallaf, W. A. I., Sharata, E. E., Attya, M. E., Abo-Youssef, A. M. & Hemeida, R. A. M. LCZ696 (sacubitril/valsartan) mitigates cyclophosphamide-induced premature ovarian failure in rats; the role of TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3/Caspase-1 signaling pathway. Life Sci.326, 121789 (2023). 10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Han, D. et al. Vinpocetine attenuates ischemic stroke through inhibiting nlrp3 inflammasome expression in mice. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol.77(2), 208–216 (2020). 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramos, A. M., Camargos, A. F. & Pereira, F. E. Effects of simultaneous treatment with estrogen and testosterone on the uterus of female adult rats. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol.34(1), 52–54 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kir, G., Sarbay, B. C. & Seneldir, H. The significance of parakeratosis alone in cervicovaginal cytology of Turkish women. Diagn. Cytopathol.45(4), 297–302 (2017). 10.1002/dc.23674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kerins, M. J. & Ooi, A. The roles of NRF2 in modulating cellular iron homeostasis. Antioxid. Redox Signal.29(17), 1756–1773 (2018). 10.1089/ars.2017.7176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abdelnaser, M., Alaaeldin, R., Attya, M. E. & Fathy, M. Modulating Nrf-2/HO-1, apoptosis and oxidative stress signaling pathways by gabapentin ameliorates sepsis-induced acute kidney injury. Naunyn-schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol.397(2), 947–958 (2024). 10.1007/s00210-023-02650-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun, Z. et al. Dihydromyricetin alleviates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome through activation of SIRT1. Biochem. Pharmacol.175, 113888 (2020). 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.113888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Samimi, F. et al. Possible antioxidant mechanism of coenzyme Q10 in diabetes: Impact on Sirt1/Nrf2 signaling pathways. Res. Pharm. Sci.14(6), 524–533 (2019). 10.4103/1735-5362.272561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang, G. et al. Resveratrol ameliorates rheumatoid arthritis via activation of SIRT1-Nrf2 signaling pathway. Biofactors46(3), 441–453 (2020). 10.1002/biof.1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen, Z. et al. Inhibition of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling leads to increased activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther.21(1), 300 (2019). 10.1186/s13075-019-2085-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu, Y. et al. Honokiol alleviates LPS-induced acute lung injury by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis via Nrf2 activation in vitro and in vivo. Chin. Med.16(1), 127 (2021). 10.1186/s13020-021-00541-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.