Abstract

Introduction

This study reports psychometric testing of the facial and total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index quantitative clinical instruments (F-VASI [range: 0–3], T-VASI [range: 0–100], respectively) using data from two phase 3 randomized, vehicle-controlled studies of ruxolitinib cream (TRuE-V1/TRuE-V2), the largest vitiligo trials conducted to date. Because VASI assessment is required by regulatory authorities, we evaluated the psychometric properties of the VASI instruments and confirmed thresholds for clinically meaningful change.

Methods

The TRuE-V1/TRuE-V2 full analysis set population included 652 patients (≥ 12 years old with nonsegmental vitiligo affecting ≤ 10% total body surface area, F-VASI ≥ 0.5, and T-VASI ≥ 3 at baseline). Data collected using the facial and total Patient Global Impression of Change–Vitiligo (PaGIC-V) and Physician’s Global Vitiligo Assessment (PhGVA) scales were used as anchors to assess F-VASI and T-VASI for reliability, validity, sensitivity to change, and clinically meaningful change.

Results

Median F-VASI and T-VASI scores were 0.70 and 6.76, respectively, at baseline, decreasing to 0.48 and 4.80 at week 24. Test–retest reliability was excellent between screening and baseline for F-VASI (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC]: 0.943) and T-VASI (ICC: 0.945). Among stable patients per PaGIC-V and PhGVA, reliability was moderate to good for both F-VASI (ICC: 0.891 and 0.739, respectively) and T-VASI (ICC: 0.768 and 0.686). F-VASI and T-VASI differentiated well among PhGVA categories mild/moderate/severe at baseline and week 24. Both VASI instruments detected changes assessed by correlations with PaGIC-V scores at week 24 (F-VASI, r = 0.610; T-VASI, r = 0.512) and changes in PhGVA scores from baseline to week 24 (F-VASI, r = 0.501; T-VASI, r = 0.344). Thresholds for clinically meaningful improvement per PaGIC-V and PhGVA were 0.38–0.60 for F-VASI and 1.69–3.88 for T-VASI.

Conclusions

Data from the TRuE-V1/TRuE-V2 studies confirmed that F-VASI and T-VASI are reliable, valid, and responsive to change, with defined clinically meaningful change from baseline in patients with nonsegmental vitiligo.

Trial Registration: The original studies were registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04052425/NCT04057573.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-024-01223-y.

Keywords: Repigmentation, Ruxolitinib cream, VASI, Vitiligo

Plain Language Summary

Vitiligo is a skin disease that causes patches of white (depigmented) skin and affects 0.5–2.0% of people worldwide. People with vitiligo often say that restoring color to white patches of skin (repigmentation) is important. Ruxolitinib cream is approved in the USA and Europe for topical treatment of vitiligo in adults and adolescents based on results from the phase 3 TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies. In these studies, applying ruxolitinib cream twice daily up to 52 weeks resulted in substantial repigmentation, as assessed by the facial and total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI/T-VASI). We aimed to confirm which changes in F-VASI/T-VASI scores represented meaningful improvement for doctors and people with vitiligo. We compared changes in VASI scores with results from two other tools used to assess vitiligo. One tool was based on doctor assessment (Physician’s Global Vitiligo Assessment [PhGVA]); the other was based on patient assessment (Patient Global Impression of Change–Vitiligo [PaGIC-V]). The analysis included clinical trial data for 652 people with vitiligo. After 6 months of treatment, median F-VASI and T-VASI scores decreased considerably, indicating improvement in repigmentation. We saw higher VASI scores for disease considered more severe per the PhGVA and PaGIC-V. Changes in VASI scores largely aligned with changes in PhGVA and PaGIC-V scores. We found that F-VASI and T-VASI are reliable tools to assess vitiligo and confirmed that improvement of 0.38–0.60 for F-VASI and 1.69–3.88 for T-VASI scores represent meaningful repigmentation in people with vitiligo on up to 10% of their bodies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-024-01223-y.

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| We previously confirmed the reliability and validity of the facial and total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI and T-VASI, respectively) measures of efficacy in 157 patients with vitiligo from the phase 2 randomized, controlled trial of ruxolitinib cream, with meaningful changes from baseline determined to be 57% for F-VASI and 42% for T-VASI. |

| In two phase 3 studies (TRuE-V1/TRuE-V2), significant repigmentation per the F-VASI and T-VASI was achieved in patients with nonsegmental vitiligo following application of 1.5% ruxolitinib cream twice daily for up to 52 weeks. |

| To further support the regulatory use of VASI instruments for assessing repigmentation in clinical trials, this study evaluated the psychometric properties of F-VASI and T-VASI and sought to confirm thresholds for clinically meaningful change using data from the largest phase 3 studies of vitiligo conducted to date. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| F-VASI and T-VASI scales are reliable and valid, can differentiate between anchor-derived disease severity at baseline, and are responsive to change, with thresholds for clinically meaningful improvement determined to be 0.38–0.60 for F-VASI and 1.69–3.88 for T-VASI. |

| These instruments are considered to be fit-for-purpose for evaluating facial and total vitiligo in adolescents and adults with nonsegmental vitiligo affecting ≤ 10% of body surface area. |

Introduction

Vitiligo is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by the destruction of melanocytes, resulting in depigmented skin lesions [1]. The worldwide prevalence of vitiligo is approximately 0.5–2.0% [2, 3], with a similar frequency for either sex and across races [4]. Although commonly misinterpreted as a cosmetic condition, vitiligo can cause significant psychological distress, including low self-esteem, embarrassment, social isolation, anxiety, and depression, negatively impacting a patient’s quality of life [5, 6].

The cream formulation of ruxolitinib, a selective Janus kinase (JAK) 1/JAK2 inhibitor, is approved in the USA, UK, and Europe for topical treatment of nonsegmental vitiligo in patients aged ≥ 12 years [7–9]. In a phase 2 dose-ranging, randomized study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03099304) and two phase 3, double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled studies (TRuE-V1 [ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04052425]/TRuE-V2 [ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04057573]), significant repigmentation was achieved in patients with vitiligo following application of ruxolitinib cream twice daily (BID) for up to 52 weeks [10, 11]. In all three studies, the efficacy of ruxolitinib cream was assessed using the facial and total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI and T-VASI, respectively), among other endpoints, to evaluate repigmentation. Although no gold standard currently exists for assessment of the extent of vitiligo involvement, the VASI is widely used, with generally high inter- and intra-rater reliability [12, 13].

As clinical trials measure change over time, the adequacy of an instrument used in a clinical trial depends on its reliability or ability to yield consistent, reproducible estimates of true treatment effects. In addition, an instrument must have construct validity such that it measures what it is designed to measure in the intended population [14]. The reliability and validity of F-VASI and T-VASI as measures of treatment efficacy in patients with vitiligo were confirmed post hoc using data from the phase 2 ruxolitinib cream study, with respective percentage change from baseline of 57% (i.e., F-VASI57) and 42% (i.e., T-VASI42), indicating a clinically meaningful change [10]. To further support the regulatory use of VASI instruments in clinical trials, we evaluated the psychometric properties of the F-VASI and T-VASI and confirmed the thresholds for clinically meaningful change, analyzing data from the phase 3 TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies, which are the largest vitiligo trials conducted to date.

Methods

Patients

Patients aged ≥ 12 years with a diagnosis of nonsegmental vitiligo and depigmented areas covering ≤ 10% total body surface area (BSA), including ≥ 0.5% BSA on the face and ≥ 3% BSA on nonfacial areas, were eligible for enrollment in TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 [11]. Patients were also required to have a score ≥ 0.5 for F-VASI (range: 0–3) and ≥ 3 for T-VASI (range: 0–100).

Study Design and Treatment

TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 were phase 3, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled studies. Full details of the study design and patient inclusion/exclusion criteria have been published previously [11]. Briefly, patients were randomized 2:1 to apply 1.5% ruxolitinib cream or vehicle cream BID for 24 weeks. This was followed by a 28-week treatment extension period, during which all patients could apply 1.5% ruxolitinib cream BID.

The trial protocols were approved by an institutional review board or ethics committee at participating centers. Trials were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and adhered to trial protocols, Good Clinical Practice, and applicable country-specific laws and regulations. Written informed consent or assent was provided by all patients.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint in the TRuE-V studies was the percentage of patients experiencing ≥ 75% improvement in F-VASI (F-VASI75) from baseline at week 24. The percentage of patients achieving ≥ 50% improvement in T-VASI (T-VASI50) at week 24 was a key secondary endpoint. Assessment of clinical outcomes using the facial and total Physician’s Global Vitiligo Assessment (F-PhGVA and T-PhGVA, respectively) and the facial and total Patient Global Impression of Change–Vitiligo (F-PaGIC-V and T-PaGIC-V, respectively) instruments were included as exploratory endpoints.

Data collected in the TRuE-V studies using the four clinical outcome instruments (F-PhGVA, T-PhGVA, F-PaGIC-V, T-PaGIC-V) were used as anchors to assess the F-VASI and T-VASI instruments for reliability, validity, sensitivity to change, and clinically meaningful change. To further support anchor-based determination of clinically meaningful change, telephone exit interviews (duration: 60 min) were conducted with patients at week 24 (Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] Methods).

Study Measures

VASI Score

The VASI is a sensitive, quantitative, clinician-reported clinical tool based on a composite estimate of the overall area of vitiligo patches and degree of macular repigmentation [12]. The VASI is measured by the percentage of vitiligo involvement (percentage of affected BSA) and the degree of depigmentation, thereby accounting for lesion integrity. For further detail on F-VASI and T-VASI determination in the TRuE-V studies, see ESM Methods and ESM Fig. 1).

PhGVA and PaGIC-V

The PhGVA is a 5-point Likert scale that reports on the severity of total body vitiligo (T-PhGVA) and facial vitiligo (F-PhGVA) as assessed by the physician. The scale ranges from 0 (clear), representing no signs of vitiligo or complete/near complete repigmentation, to 4 (severe disease), representing extensive areas of vitiligo with complete depigmentation (ESM Table 1). The PaGIC-V scale is a patient’s global evaluation of change from baseline of their treated areas of total body vitiligo (T-PaGIC-V) and facial vitiligo (F-PaGIC-V). The PaGIC-V is based on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse).

Statistical Analysis

Test–retest reliability (i.e., stability of the VASI instruments over time) was assessed on the pooled treatment arms across TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) between two time points for stable patients. Three test–retest pairs were considered for F-VASI and T-VASI scores: definition 1, screening to baseline; definition 2, no change in PaGIC-V at week 24 (with respect to baseline); and definition 3, no change in PhGVA scores between baseline and week 24. Only patients with nonmissing data at both screening and baseline (definition 1) and baseline and week 24 (definitions 2 and 3) were included in the analysis. ICC values of 0.50–0.90 were considered to represent moderate to good reliability; values > 0.90 represent excellent reliability [15].

Construct validity of VASI was evaluated from two aspects: convergent validity and known group validity. Convergent validity was assessed by evaluating the relationship between the VASI and PhGVA at baseline and week 24 using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient. Values of 0.50–0.70, ≥ 0.70–0.90, and ≥ 0.90 represented moderate, high, and very high correlations, respectively [16]. Known-group validity analysis was conducted to determine the ability of F-VASI and T-VASI to distinguish between patients known to differ by PhGVA severity. Mean F-VASI and T-VASI scores were compared at baseline and week 24 for the following groups based on F-PhGVA/T-PhGVA scores: clear (0) or almost clear (1); mild disease (2); moderate disease (3); and severe disease (4). The F-PhGVA and T-PhGVA clear and almost clear groups were merged due to low sample size and designated as “clear.” Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the mean score at baseline and week 24 between groups, with the known groups as the independent variable and F-VASI and T-VASI scores as dependent variables (α = 0.05 level). A nonparametric test (e.g., Kruskal–Wallis test) was conducted if the sample size was low (i.e., < 30 patients per category).

Effect size between adjacent PhGVA severity categories (mild vs. clear [including clear and almost clear], moderate vs. mild, severe vs moderate) for F-VASI and T-VASI was calculated at baseline and week 24 based on Cohen's d to assess the magnitude of group differences. Effect sizes ≥ 0.50 to < 0.80 and ≥ 0.80 were interpreted as moderate and large, respectively [17].

Sensitivity to change was examined using Spearman correlation to test if a change in VASI was concurrent with change in PhGVA from baseline to week 24 and PaGIC-V at week 24. An anchor was considered adequate if the correlation coefficient was > 0.30 [18].

Clinically meaningful thresholds for F-VASI and T-VASI were derived using anchor-based methods, supplemented by distribution-based methods, and descriptive statistics for patients reporting meaningful change in exit interviews. In addition, empirical cumulative distribution function (eCDF) curves and probability density function (PDF) curves were examined visually to ensure separation in the curves between anchor groups. For the anchor-based method, descriptive statistics were calculated for all categories of the PaGIC-V and PhGVA anchors as well as for revised groupings that provided a clearer difference between patients who had and had not experienced meaningful change (i.e., categorized as moderate or large improvement, small or moderate improvement, any improvement, or worsening). Two distribution-based approaches were also taken employing baseline VASI scores: one-half standard deviation (SD) and 1 standard error of the measurement (SEM).

Results

Study Population

The full analysis set included 652 patients from TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 [11], with 36 patients completing exit interviews at week 24. During the 24-week study period, compliance with outcomes assessment using F-VASI and T-VASI was high (93.0% [598/643] to 100.0% [652/652]), as was compliance with assessment for the anchors (F-PhGVA and T-PhGVA: 94.3% [597/633] to 99.4% [648/652]; F-PaGIC-V: 96.2% [609/633] to 99.0% [593/599]; T-PaGIC-V: 96.4% [610/633] to 99.0% [593/599]).

Clinical Outcome Assessment Descriptive Statistics

Baseline median (range) F-VASI and T-VASI scores among all patients were 0.70 (0.40–3.00) and 6.76 (2.65–10.00), respectively, and decreased to 0.48 (0.00–3.00) and 4.80 (0.30–13.66) at week 24, indicating that vitiligo lesions were repigmented.

Based on F-PhGVA and T-PhGVA scores, almost all patients (> 90%) were rated as having mild or moderate disease at baseline, with very few patients reporting clear/almost clear or severe disease. There were fewer patients in the moderate disease category for F-PhGVA at baseline than in the moderate disease category for T-PhGVA (39.8% [258/648] and 60.5% [392/648], respectively). There was a shift toward lower PhGVA severity (i.e., improvement) over time for F-PhGVA and T-PhGVA, with fewer patients in the moderate disease category at week 24 (23.1% [135/585] and 45.3% [265/585]) than at baseline.

Based on F-PaGIC-V and T-PaGIC-V scores, > 20% (31.5% [187/593] and 21.7% [129/593], respectively) reported medium or high levels of improvement (i.e., much improved or very much improved) in both total and facial ratings at week 24; approximately two-thirds of patients (F-PaGIC-V: 63.7% [378/593]; T-PaGIC-V: 70.2% [416/593]) reported some improvement or stability (i.e., minimally improved or no change). Few patients (< 10%) reported any level of worsening (i.e., minimally worse, much worse, or very much worse).

Test–Retest Reliability

Test–retest reliability was excellent (> 0.9) between screening and baseline for F-VASI (ICC 0.943, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.934–0.951 [n = 651]) and T-VASI (ICC 0.945, 95% CI 0.936–0.953 [n = 651]). Among stable patients (i.e., no change in PaGIC-V or PhGVA between baseline and week 24), reliability was moderate to good (0.5–0.9) for F-VASI (F-PaGIC-V: ICC 0.891, 95% CI 0.841–0.924 [n = 192]; F-PhGVA: ICC 0.739, 95% CI 0.494–0.848 [n = 321]) and T-VASI (T-PaGIC-V: ICC 0.768, 95% CI 0.690–0.827 [n = 162]; T-PhGVA: ICC 0.686, 95% CI 0.395–0.818 [n = 384]; Table 1).

Table 1.

Intraclass correlation coefficients within stable patients as defined by the PaGIC-V and PhGVA scales at screening/baseline and week 24

| Scale | Definition | n | ICC | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-VASIa | 1. Screening and baseline periods | 651 | 0.943 | 0.934, 0.951 |

| 2. No change in F-PaGIC-V between baseline and week 24 | 192 | 0.891 | 0.841, 0.924 | |

| 3. No change in F-PhGVA between baseline and week 24 | 321 | 0.739 | 0.494, 0.848 | |

| T-VASIa | 1. Screening and baseline periods | 651 | 0.945 | 0.936, 0.953 |

| 2. No change in T-PaGIC-V between baseline and week 24 | 162 | 0.768 | 0.690, 0.827 | |

| 3. No change in T-PhGVA between baseline and week 24 | 384 | 0.686 | 0.395, 0.818 |

F-PaGIC-V facial Patient Global Impression of Change–Vitiligo; F-PhGVA facial Physician’s Global Vitiligo Assessment; F-VASI facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index; ICC intraclass correlation coefficient; T-PaGIC-V total Patient Global Impression of Change–Vitiligo; T-PhGVA total Physician’s Global Vitiligo Assessment; T-VASI total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index

aF-VASI was compared with the corresponding F-PaGIC-V and F-PhGVA scales; T-VASI was compared with the corresponding T-PaGIC-V and T-PhGVA scales

Construct Validity

Convergent Validity

Convergent validity was assessed by evaluating the relationship between VASI and PhGVA measures at baseline and week 24. Using this approach, Spearman rank correlations showed correlation between VASI and PhGVA scores, with higher correlations reported at week 24 compared with baseline for both F-VASI (r = 0.577 [n = 584] vs. r = 0.339 [n = 648]) and T-VASI (r = 0.490 [n = 585] vs. r = 0.310 [n = 648]).

Known-Group Validity

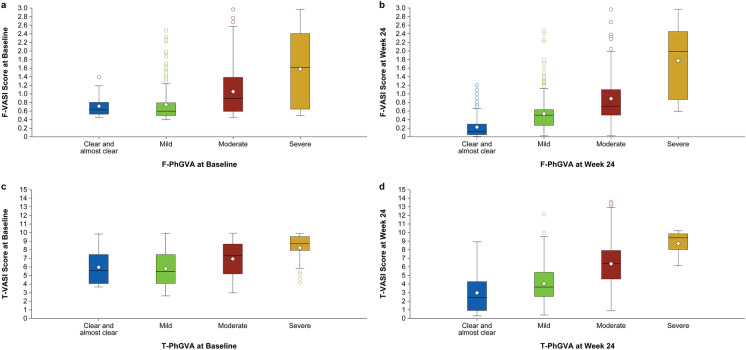

F-VASI and T-VASI differentiated well among most PhGVA severity groups, showing higher VASI scores for more severe disease at baseline and week 24, thereby demonstrating known-group validity (Fig. 1). Mean differences for F-VASI and T-VASI between PhGVA severity groups were statistically significant at baseline and week 24 (P < 0.0001). Effect sizes were moderate to large (≥ 0.5) in most cases; the effect size range was 0.620–1.460 for F-VASI and 0.589–1.006 for T-VASI for the difference between mild versus moderate, and moderate versus severe disease at baseline and week 24. For the difference between clear/almost clear and mild disease, the effect size was small at baseline where category sample sizes were low (F-VASI: 0.095 [n = 20]; T-VASI: – 0.078 [n = 15]). However, as more patients moved into the clear/almost clear PhGVA category at week 24, F-VASI (n = 139; effect size: 0.896) and to a lesser extent T-VASI (n = 34; effect size: 0.470) differentiated well between clear/almost clear and mild disease.

Fig. 1.

Known-group validity based on the correlation of F-VASI Scores by F-PhGVA Severity Groupsa at baseline (a) and week 24 (b) and T-VASI scores by T-PhGVA Severity Groupsa at baseline (c) and week 24 (d). F-PhGVA Facial Physician’s Global Vitiligo Assessment, F-VASI facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index, T-PhGVA total Physician’s Global Vitiligo Assessment; T-VASI total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index. aThe F-PhGVA and T-PhGVA clear and almost clear groups were merged together due to low sample size

Ability to Detect Change

Both VASI instruments were able to detect changes from baseline to week 24, as indicated by correlations with the PhGVA and PaGIC-V scores. The correlation between F-VASI and F-PhGVA change scores from baseline to week 24 was 0.501 (n = 580), and 0.610 (n = 591) between F-VASI change scores and F-PaGIC-V scores at week 24. The corresponding correlation between T-VASI and T-PhGVA change scores from baseline to week 24 was 0.344 (n = 581), and 0.512 (n = 592) between T-VASI change scores and T-PaGIC-V scores at week 24. These correlations (all r > 0.3) were sufficient to suggest that PhGVA and PaGIC-V are adequate anchors for estimating clinically meaningful within-patient change.

Clinically Meaningful Within-Patient Change

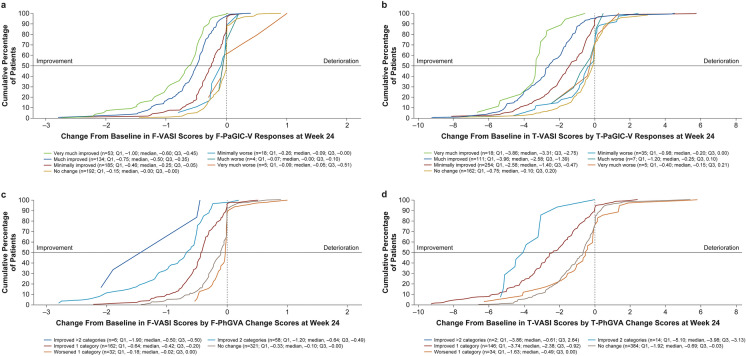

Distribution-based approaches for F-VASI (n = 652) yielded values of 0.28 for both 1/2 SD at baseline and SEM; for T-VASI (n = 652), values were 1.03 for 1/2 SD at baseline and 1.16 for SEM. Using PhGVA and PaGIC-V as anchors to determine clinically meaningful within-patient change, anchor-based meaningful within-patient improvement thresholds ranged from a median of 0.38–0.60 for F-VASI and 1.69–3.88 for T-VASI (Table 2), which exceeded distribution-based estimates. Similar thresholds were obtained from patient exit interviews for F-VASI and T-VASI. Median (SD) change from baseline to week 24 for patients who reported a meaningful improvement in exit interviews at week 24 was 0.51 (0.61) for F-VASI (n = 26) and 2.40 (1.98) for T-VASI (n = 25), with both values falling in the middle of the intervals obtained by the anchor-based estimates (F-VASI: median 0.38–0.60; T-VASI: median 1.69–3.88). eCDF curves showed clear separation of PaGIC-V improvement categories (i.e., very much improved, much improved, and minimally improved) from each other and with the “no change” category for both F-VASI and T-VASI (Fig. 2a, b), as well as for PhGVA change categories for both F-VASI and T-VASI (Fig. 2c, d). Similarly, PDF curves showed clear separation for PaGIC-V (ESM Fig. 2a, 2b) and for PhGVA change categories for both F-VASI and T-VASI (ESM Fig. 2c, 2d).

Table 2.

Clinically meaningful thresholds using anchor-based estimates for F-VASI and T-VASI scores at week 24

| Anchor and categories | F-VASIa | T-VASIa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Median (Q1, Q3) | n | Median (Q1, Q3) | |

| PaGIC-Vb | ||||

| Moderate or large improvement | 187 | 0.53 (0.37, 0.84) | 129 | 2.75 (1.55, 3.93) |

| Small or moderate improvement | 372 | 0.41 (0.19, 0.67) | 383 | 1.78 (0.65, 3.12) |

| Any improvement | 319 | 0.38 (0.16, 0.59) | 365 | 1.69 (0.59, 2.97) |

| Worsening | 27 | 0.05 (0.00, 0.25) | 47 | 0.20 (− 0.08, 0.98) |

| PhGVAc | ||||

| Moderate or large improvement | 64 | 0.60 (0.49, 1.21) | 16 | 3.88 (3.10, 4.81) |

| Small or moderate improvement | 226 | 0.49 (0.30, 0.72) | 162 | 2.58 (0.99, 4.00) |

| Any improvement | 220 | 0.48 (0.30, 0.72) | 160 | 2.58 (1.00, 4.03) |

| Worsening | 33 | 0.00 (0.00, 0.17) | 35 | 0.42 (0.00, 1.63) |

F-VASI Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index, PaGIC-V Patient Global Impression of Change–Vitiligo, PhGVA Physician’s Global Vitiligo Assessment, Q1 first quartile, Q3 third quartile, T-VASI total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index

aF-VASI was compared with the corresponding F-PaGIC-V and F-PhGVA scales; T-VASI was compared with the corresponding T-PaGIC-V and T-PhGVA scales

bModerate or large improvement includes PaGIC-V categories of very much improved or much improved; small or moderate improvement includes PaGIC-V categories of much improved or minimally improved; any improvement includes PaGIC-V categories of very much improved, much improved, or minimally improved

cModerate or large improvement is indicated by a PhGVA change score ≤ − 2; small or moderate improvement is indicated by a PhGVA change score between − 2 and − 1; any improvement is indicated by PhGVA score ≤ − 1

Fig. 2.

Empirical cumulative function for F-VASI scores (a) and T-VASI scores (b) by PaGIC-V responses at week 24 and for F-VASI scores (c) and T-VASI scores (d) by PhGVA change scores at week 24. The horizontal line can be used as a visual guide to identify the approximate median change from baseline in the x-axis for each plotted category. Negative values (i.e., to the left of the x-axis zero) indicate improvement from baseline. FAS Full analysis set; F-PaGIC-V/T-PaGIC-V facial/total Patient Global Impression of Change–Vitiligo, F-PhGVA/T-PhGVA facial/total Physician’s Global Vitiligo Assessment, F-VASI facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index, T-VASI total Vitiligo Area Scoring Index

Discussion

This psychometric analysis provides the first large population clinical trial evidence of the reliability and validity of F-VASI and T-VASI as measures for assessing the extent of vitiligo involvement among a population of adolescent and adult patients with nonsegmental vitiligo. F-VASI and T-VASI had favorable measurement properties that were closely aligned with the expected psychometric thresholds for test–retest reliability, as evidenced by ICC values of approximately ≥ 0.70, and for convergent validity, showing moderate correlations (r ≈ 0.5) between F-VASI and F-PhGVA and between T-VASI and T-PhGVA at week 24.

F-VASI and T-VASI also demonstrated an ability to differentiate between groups known to be different based on PhGVA. F-VASI and T-VASI were able to differentiate between mild versus moderate disease, and moderate versus severe disease on the PhGVA scale with a moderate to large effect size. Of note, the effect size was small for differentiation between clear/almost clear and mild disease at baseline, likely due to the small number of patients in that category (≤ 20 patients for F-VASI and T-VASI). As the number of patients in the PhGVA category for clear/almost clear skin increased following repigmentation of lesions at week 24, F-VASI and T-VASI were able to differentiate well between clear/almost clear and mild disease.

Importantly, the responsiveness of F-VASI and T-VASI suggested a good ability to detect change in vitiligo when change was assessed either by the patient using PaGIC-V scores or by the physician using PhGVA scores. PaGIC-V and PhGVA were considered to be appropriate anchors (correlation with VASI > 0.3), with clear separation observed in eCDF plots between patients with an improvement in their vitiligo versus those who had no change or worsening of disease for both anchors. Of note, change categories for worse disease for PaGIC-V and PhGVA showed little difference in eCDF and PDF plots compared with the categories for no change. These may be due to the nature of this clinical trial, in which approximately three-quarters of patients had stable disease at baseline and relatively few patients applying either vehicle or ruxolitinib cream had worse disease at week 24 [11]. The meaningful change threshold analysis revealed that an appropriate individual-level threshold for identifying clinically relevant responders would be between 0.38 and 0.60 for F-VASI and between 1.69 and 3.88 for T-VASI. These thresholds were higher than distribution-based estimates and similar to median F-VASI and T-VASI scores of patients reporting improvement based on exit interviews.

Strengths and Limitations

This study benefitted from inclusion of a large sample of patients (n = 652), which exceeded the number of patients (n = 157) in the phase 2 study of ruxolitinib cream that included a post hoc analysis of the F-VASI and T-VASI instruments [10]. Furthermore, the use of both screening and baseline assessments ensured that test–retest reliability could be thoroughly evaluated.

An important limitation of this study is that data from the analyses were from patients enrolled in TRuE-V trials, potentially limiting the generalizability of results. Indeed, T-VASI, which has a theoretical range of 0–100, ranged from 2.65 to 10.00 at baseline in this study, based on inclusion criteria for the TRuE-V trials, which limited enrollment to patients with total affected BSA ≤ 10%. Thus, the maximum possible improvement in T-VASI was 10.00 points, which may have resulted in an underestimation of the threshold of clinically meaningful change for T-VASI. In patients with higher T-VASI values (and thus more extensive vitiligo), further analysis may be required to confirm/identify clinically meaningful change. Additionally, evaluation of validation and thresholds for clinically meaningful change were not analyzed by skin type, and the majority of patients enrolled in TRuE-V trials had fairer skin (Fitzpatrick skin types I–III), with very few having skin types V or VI [11]. Patients with darker skin show greater contrast of depigmented lesions against their natural skin tone, and thresholds for clinically meaningful change may be different than those observed in patients with fairer skin. A further limitation is that methods for determining VASI, a semiobjective score, in clinical trials are heterogeneous and lack standardization [19]. This may result in reproducibility issues, especially for an instrument that has a relatively high score for smallest detectable change (intraobserver: 4.7%; interobserver, 7.1%) [13]. Harmonization of methods for determining VASI is necessary to ensure that results from this study may be reproducible. Using the fingertip unit for measurement of smaller lesions, especially when measuring F-VASI, may also improve precision of measurement [20].

Conclusion

Based on clinical data from the largest randomized controlled trials in vitiligo conducted to date, the F-VASI and T-VASI instruments were found to be reliable and valid measures for evaluating facial and total body vitiligo and demonstrated good responsiveness to change, including clinically meaningful within-patient change, among patients in this study population. Based on the good psychometric properties of F-VASI and T-VASI, both scales are considered to be fit-for-purpose to evaluate facial and total vitiligo in adolescents and adults with nonsegmental vitiligo and depigmented areas ≤ 10% total BSA.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Kang Sun, PhD, an employee of Incyte, for his critical review of the manuscript.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Medical writing assistance was provided by Lee Hohaia, PharmD, an employee of ICON (Blue Bell, PA, USA), and was funded by Incyte Corporation (Wilmington, DE, USA).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Kristen Bibeau, Iltefat H. Hamzavi. Methodology: Kristen Bibeau, Kathleen Butler, Mingyue Wang, Konstantina Skaltsa. Formal analysis and investigation: Mingyue Wang, Konstantina Skaltsa. Writing–original draft preparation: Kristen Bibeau, Konstantina Skaltsa. Writing—review and editing: all authors.

Funding

Incyte Corporation sponsored the trial, including providing the active trial drug and matching vehicle cream (without active ingredient), participated in trial design, and collaborated with authors in analyzing and interpreting the data and writing and approving the manuscript. Authors prepared the manuscript, with medical writing assistance funded by the sponsor. All authors confirm the accuracy and completeness of the data and analyses and adherence to the trial protocol. Agreements requiring investigators to maintain data confidentiality were in place between the sponsor and authors. The sponsor could not delay or interdict publication of the results of the trial. The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by Incyte.

Data Availability

Incyte Corporation (Wilmington, DE, USA) is committed to data sharing that advances science and medicine while protecting patient privacy. Qualified external scientific researchers may request anonymized datasets owned by Incyte for the purpose of conducting legitimate scientific research. Researchers may request anonymized datasets from any interventional study (except phase 1 studies) for which the product and indication have been approved on or after 1 January 2020 in at least one major market (e.g., USA, EU, Japan). Data will be available for request after the primary publication or 2 years after the study has ended. Information on Incyte’s clinical trial data sharing policy and instructions for submitting clinical trial data requests are available at: https://www.incyte.com/Portals/0/Assets/Compliance%20and%20Transparency/clinical-trial-data-sharing.pdf?ver=2020-05-21-132838-960.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

Kristen Bibeau (currently Moderna), Kathleen Butler (currently Astria Therapeutics, Inc.), and Mingyue Wang (currently Boehringer Ingelheim) are former employees of Incyte Corporation and are shareholders of Incyte. Konstantina Skaltsa is an employee of IQVIA contracted by Incyte Corporation to perform the psychometric analysis reported in this article. Iltefat H Hamzavi has served as an advisory board member for AbbVie; as a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, Galderma Laboratories LP, Incyte Corporation, Pfizer, and UCB; as a principal investigator for Avita, Bayer, Estée Lauder, Ferndale Laboratories, Incyte Corporation, Lenicura, L’Oréal, Pfizer, and Unigen; as a subinvestigator for Arcutis; as president of the HS Foundation; and as board member of the Global Vitiligo Foundation.

Ethical Approval

The trial protocols were approved by an institutional review board or ethics committee at participating centers. Trials were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and adhered to trial protocols, Good Clinical Practice, and applicable country-specific laws and regulations. Written informed consent or assent was provided by all patients.

Footnotes

Prior Publication: Data included in this manuscript have previously been presented at: Maui Derm for Dermatologists, Grand Wailea, Maui, HI, USA, 24–28 January 2022, with encores at the Global Vitiligo Foundation Annual Scientific Symposium, Boston, MA, USA, 24 March 2022 and at the Innovations in Dermatology Spring Conference, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 27–30 April 2022.

References

- 1.Rodrigues M, Ezzedine K, Hamzavi I, Pandya AG, Harris JE, Vitiligo Working Group. New discoveries in the pathogenesis and classification of vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(1):1–13. 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bibeau K, Pandya AG, Ezzedine K, et al. Vitiligo prevalence and quality of life among adults in Europe, Japan and the USA. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(10):1831–44. 10.1111/jdv.18257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kruger C, Schallreuter KU. A review of the worldwide prevalence of vitiligo in children/adolescents and adults. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(10):1206–12. 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05377.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plensdorf S, Livieratos M, Dada N. Pigmentation disorders: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Phys. 2017;96(12):797–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osinubi O, Grainge MJ, Hong L, et al. The prevalence of psychological comorbidity in people with vitiligo: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(4):863–78. 10.1111/bjd.16049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Jones H, et al. Psychosocial effects of vitiligo: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(6):757–74. 10.1007/s40257-021-00631-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Incyte Biosciences UK Ltd. Opzelura™ (ruxolitinib cream). Summary of product characteristics. 2023. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/14903/smpc#about-medicine. Accessed 22 Feb 2024.

- 8.Incyte Biosciences Distribution B.V. Opzelura™ (ruxolitinib cream). Summary of product characteristics. 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/opzelura-epar-productinformation_en.pdf. Accessed 22 Feb 2024.

- 9.Incyte Corporation. Opzelura™ (ruxolitinib cream). Full prescribing information. 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215309s001lbl.pdf. Accessed 22 Feb 2024.

- 10.Rosmarin D, Pandya AG, Lebwohl M, et al. Ruxolitinib cream for treatment of vitiligo: a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10244):110–20. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30609-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosmarin D, Passeron T, Pandya AG, et al. Two phase 3, randomized, controlled trials of ruxolitinib cream for vitiligo. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1445–55. 10.1056/NEJMoa2118828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamzavi I, Jain H, McLean D, Shapiro J, Zeng H, Lui H. Parametric modeling of narrowband UV-B phototherapy for vitiligo using a novel quantitative tool: the Vitiligo Area Scoring Index. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140(6):677–83. 10.1001/archderm.140.6.677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komen L, da Graca V, Wolkerstorfer A, de Rie MA, Terwee CB, van der Veen JP. Vitiligo Area Scoring Index and Vitiligo European Task Force assessment: reliable and responsive instruments to measure the degree of depigmentation in vitiligo. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(2):437–43. 10.1111/bjd.13432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. 2009. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/patient-reported-outcome-measures-use-medical-product-development-support-labeling-claims. Accessed 1 Mar 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. 2016;15(2):155–63. 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukaka MM. Statistics corner: a guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Med J. 2012;24(3):69–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sullivan GM, Feinn R. Using effect size-or why the P value is not enough. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(3):279–82. 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00156.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coon CD, Cook KF. Moving from significance to real-world meaning: methods for interpreting change in clinical outcome assessment scores. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(1):33–40. 10.1007/s11136-017-1616-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ceresnie MS, Warbasse E, Gonzalez S, Pourang A, Hamzavi IH. Implementation of the Vitiligo Area Scoring Index in clinical studies of patients with vitiligo: a scoping review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315(8):2233–59. 10.1007/s00403-023-02608-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bae JM, Zubair R, Ju HJ, et al. Development and validation of the fingertip unit for assessing Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(2):387–93. 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Incyte Corporation (Wilmington, DE, USA) is committed to data sharing that advances science and medicine while protecting patient privacy. Qualified external scientific researchers may request anonymized datasets owned by Incyte for the purpose of conducting legitimate scientific research. Researchers may request anonymized datasets from any interventional study (except phase 1 studies) for which the product and indication have been approved on or after 1 January 2020 in at least one major market (e.g., USA, EU, Japan). Data will be available for request after the primary publication or 2 years after the study has ended. Information on Incyte’s clinical trial data sharing policy and instructions for submitting clinical trial data requests are available at: https://www.incyte.com/Portals/0/Assets/Compliance%20and%20Transparency/clinical-trial-data-sharing.pdf?ver=2020-05-21-132838-960.