Abstract

Introduction

A dynamic molecular biomarker that can identify early efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy remains an unmet clinical need. Here we evaluate if a novel circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) assay, xM, used for treatment response monitoring (TRM), that quantifies changes in ctDNA tumor fraction (TF), can predict outcome benefits in patients treated with ICI alone or in combination with chemotherapy in a real-world (RW) cohort.

Methods

This retrospective study consisted of patients with advanced cancer from the Tempus de-identified clinical genomic database who received longitudinal liquid-based next-generation sequencing. Eligible patients had a blood sample ≤ 40 days prior to the start of ICI initiation and an on-treatment blood sample 15–180 days post ICI initiation. TF was calculated via an ensemble algorithm that utilizes TF estimates derived from variants and copy number information. Patients with molecular response (MR) were defined as patients with a ≥ 50% decrease in TF between tests. In the subset of patients with rw-imaging data between 2 and 18 weeks of ICI initiation, the predictive value of MR in addition to rw-imaging was compared to a model of rw-imaging alone.

Results

The evaluable cohort (N = 86) was composed of 14 solid cancer types. Patients received either ICI monotherapy (38.4%, N = 33) or ICI in combination with chemotherapy (61.6%, N = 53). Patients with MR had significantly longer rw-overall survival (rwOS) (hazard ratio (HR) 0.4, P = 0.004) and rw-progression free survival (rwPFS) (HR 0.4, P = 0.005) than patients with molecular non-response (nMR). Similar results were seen in the ICI monotherapy subcohort; HR 0.2, P = 0.02 for rwOS and HR 0.2, P = 0.01 for rwPFS. In the subset of patients with matched rw-imaging data (N = 51), a model incorporating both MR and rw-imaging was superior in predicting rwOS than rw-imaging alone (P = 0.02).

Conclusions

xM used for TRM is a novel serial quantitative TF algorithm that can be used clinically to evaluate ICI therapy efficacy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40487-024-00287-2.

Keywords: Immune checkpoint inhibitors, Real-world data, ctDNA longitudinal biomarkers, Treatment response monitoring

Key Summary Points

| In this study, we present a novel algorithm to quantify longitudinal changes in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) via liquid biopsy at varied on-treatment timepoints in a real-world (RW) cohort of patients with advanced pan-cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) alone or in combination with chemotherapy. |

| Patients with molecular response (MR) had significantly longer real-world overall survival (rwOS) and real-world progression free survival (rwPFS) than patients with molecular non-response (nMR). |

| In the subset of patients with matched rw-imaging data, MR in combination with rw-imaging response had a stronger association with rwOS than rw-imaging response alone. |

| These data demonstrate the robustness of a longitudinal, non-invasive molecular biomarker that may be used clinically to evaluate ICI efficacy. |

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have demonstrated survival benefit across a range of solid tumor indications [1–6], and are administered routinely for multiple cancer types alone or in combination with chemotherapy [7–11]. Despite their widespread use, only a subset of patients derive long-term benefits [12–14], highlighting the need for a robust, dynamic, predictive biomarker that can be utilized to evaluate ICI efficacy early in the course of a patient’s therapeutic journey.

Serial testing of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) has the potential to transform ICI therapy management as a minimally invasive, dynamic monitoring biomarker that can track quantitative changes in tumor burden and complement current standard of care computed tomography (CT) imaging. These changes may serve as a predictive biomarker for ICI therapy response, as they have been shown to be associated with clinical outcomes [15–18]. Studies have shown that molecular progression may be detected prior to CT imaging, as early as 3 weeks after ICI initiation [19], which represents an earlier opportunity to intervene therapeutically and potentially improve clinical outcomes. Furthermore, longitudinal ctDNA-based biomarkers can identify patients with radiographic stable disease assessments that are molecular non-responders (nMRs) with poor survival outcomes [17, 20] that may benefit from early treatment intervention. Such biomarkers can also identify patients with pseudo-progression via imaging and may be useful in preventing premature therapy change or discontinuation [21].

Several algorithms to estimate circulating tumor fractions (TF) have emerged. Most algorithms include a combination of somatic single nucleotide variants, insertions and deletions, and fusions to estimate TF. Our algorithm additionally incorporates copy number variants (CNVs) for a more robust estimation of TF [22]. Through this approach we reduce the impact of possible stochastic sampling bias through single measurements including maximum somatic variant allele frequency (VAF), account for non-mutational events, such as CNVs, which often drive tumorigenesis [23], and limit potential noise from regions with loss of heterozygosity (LOH) detected.

Here we describe xM used for treatment response monitoring (TRM), a dynamic ctDNA biomarker, which quantifies ctDNA TF changes across two sequential patient blood samples, and its association with real-world (RW) outcomes in a pan-solid tumor cohort treated with ICI alone or in combination with chemotherapy. Further, we assess if xM for TRM has predictive value in stratifying real-world overall survival (rwOS) outcomes beyond rw-imaging responses alone.

Methods

Study Design and Cohort Description

This is a retrospective pan-solid tumor cohort study consisting of patients with advanced-stage solid tumor cancer from the Tempus deidentified clinical genomic database who received at least two longitudinal Tempus liquid-based next generation sequencing (NGS) tests between 2019 and 2023. Figure 1a delineates the study CONSORT diagram. Eligible patients had a pre-treatment blood sample collected 0–40 days prior to ICI initiation and an on-treatment blood sample collected within 15–180 days of ICI initiation. If a patient had a liquid biopsy within 40 days of terminating ICI therapy or starting a new therapy they were considered eligible for the study. For patients with no medication end date information or start of next therapy information, we assumed patients remained on therapy until the last known date of follow-up. If patients had more than two blood samples, the two blood samples closest to the start of ICI treatment were included. All patients were treated with US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved ICIs (atezolizumab, avelumab, cemiplimab, dostarlimab, durvalumab, ipilimumab, nivolumab, ipilimumab in combination with nivolumab, tremelimumab, and pembrolizumab). An additional analysis was performed on the subset of evaluable patients with rw-imaging within 2–18 weeks of ICI therapy initiation (denoted rw-imaging subcohort). For patients with multiple imaging results, we utilized the imaging evaluation at the timepoint closest to the on-treatment test.

Fig. 1.

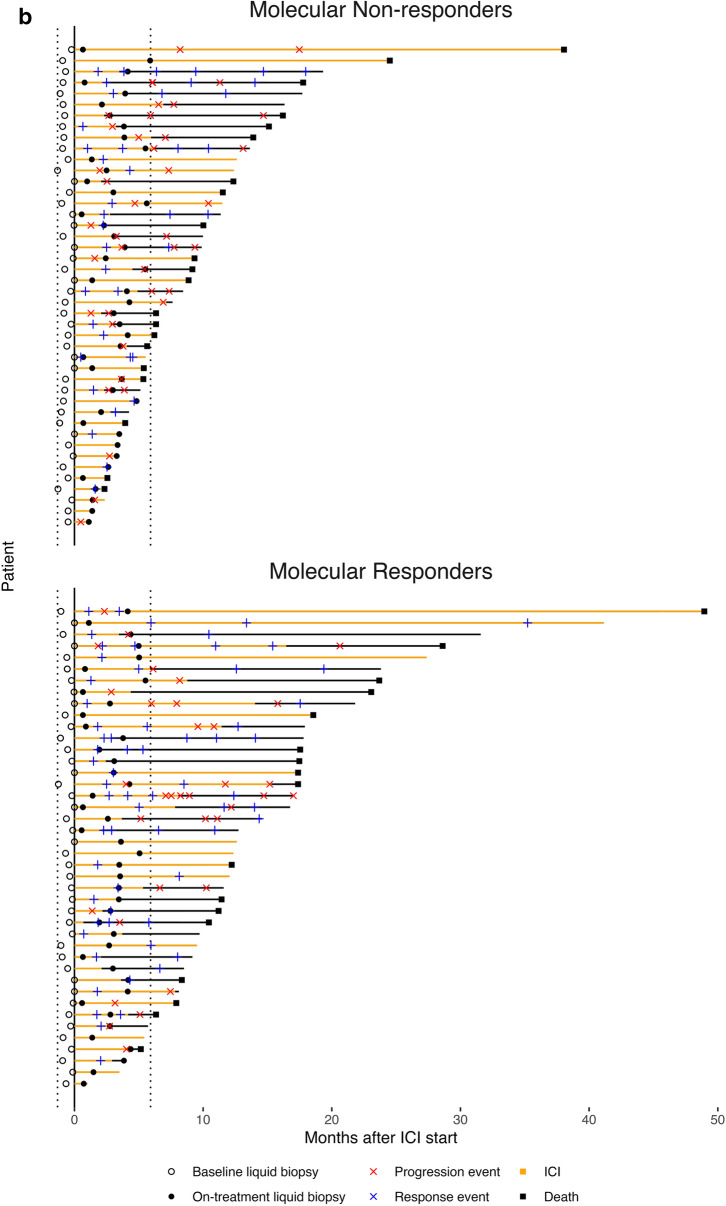

a CONSORT diagram showing the numbers of patients included in the study; b swimmers plot showing timing of baseline and on-treatment testing, ICI duration, last known follow-up, rw-imaging and death, grouped by MR. ICI immune checkpoint inhibitor, LOB limit of blank, MR molecular response, rw real world

Tempus AI, Inc. has been granted an institutional review board (IRB) exemption (Advarra Pro00072742) permitting the use of deidentified clinical, molecular, and multimodal data in order to derive or capture results, insights, or discoveries. All patient-level data were deidentified in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). This study follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies.

Liquid Biopsy NGS Assay

Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) was extracted, library prepped, sequenced, and run through the 105-gene liquid biopsy assay and bioinformatics pipeline as previously described [22].

ctDNA Tumor Fraction Estimation

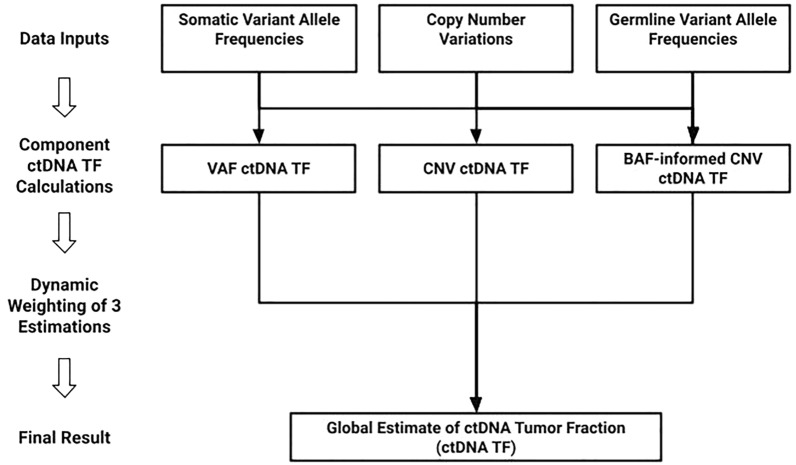

The ctDNA TF was calculated from three intermediate tumor fraction estimates derived from different genomic events: CNVs, somatic variant allele frequencies (VAFs), and germline VAFs (Fig. 2; see Supplementary Material for a detailed description of the algorithm). The CNV TF was estimated from on- and off-target genomic regions. Somatic VAFs evaluated were from a curated list of pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants. Germline variants likely in LOH regions were used to calculate an informed CNV TF.

Fig. 2.

ctDNA TF methodology. BAF B allele frequency, CNV copy number variants, VAF variant allele frequency, ctDNA circulating tumor DNA, TF tumor fraction

Samples are assigned to different weights for each intermediate TF estimate depending upon the CNV, somatic, and germline variant informed TF. To calculate an ensemble ctDNA TF estimate from the three intermediate TFs, Boltzmann sigmoid functions were trained to yield dynamic weights applicable to each of the intermediate TF estimates such that the weights sum to 1 (see Supplementary Material).

The limit of blank (LOB) was determined using 29 presumed healthy subjects using the classical non-parametric rank-based approach. The 95th percentile of the TF in these patients was found to be 0.6% and was used as the LOB threshold. Patients were considered evaluable if they had a baseline or on-treatment TF above the LOB threshold.

Orthogonal Methods for Assessing ctDNA TF Linearity

Our method of calculating ctDNA TF was compared against a tumor-informed ctDNA TF estimate [24]. Briefly, somatic variants called in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) matched tumor-normal samples (xT; 648 gene panel) whose VAFs are within two standard deviations of the mean VAF are then queried in the corresponding liquid biopsy isolate. The median VAF for the variants in the liquid biopsy isolate is the tumor-informed ctDNA TF. The tumor-informed ctDNA TF had a limit of detection (LOD) of ≤ 0.1% [24]. The linearity of the tumor-informed ctDNA TF was evaluated against ichorCNA TF, an alternative approach to estimating ctDNA TF that utilizes copy number alterations in ultra low-pass whole genome sequencing (LPWGS) [25]. In addition to the tumor-informed ctDNA TF, we also compared our method of calculating ctDNA TF to ichorCNA utilizing a cohort of clinical tumor isolates that underwent LPWGS (N = 375) [25].

RW-Outcomes

Clinical data were retrospectively abstracted from the Tempus multimodal clinical genomic database of longitudinal structured and unstructured physician progress notes from diverse oncology practices, including both academic medical centers and community practices. Dates of death were captured either from retrospectively abstracted patient medical records or from third-party data sources that come from obituary documentation that was augmented to the death master file from the Social Security Administration. The resulting death information was integrated with Tempus data via an encrypted token system. Dates of progression were retrospectively abstracted from patient medical records including imaging, laboratory tests, physician dictation, and physical exam notes captured in clinical records. For the rw-imaging subcohort only rw-imaging results via physician dictation or imaging were included. Patients were classified as responders via rw-imaging if they had a complete response (CR), partial response (RD), or stable disease (SD). Patients were classified as non-responders via rw-imaging if they had progressive disease (PD).

MR Threshold Definition

Consistent with the Friends of Cancer research (FOCR) ctDNA for Monitoring Treatment Response (ctMoniTR) Project [26], published data [17, 27, 28], and widespread clinical use, if both timepoints were above the LOB, a ≥ 50% reduction in TF from baseline to on-treatment timepoint was used as a binary measure to define patients with MR. Additionally, patients with TF above LOB at baseline and below LOB at the on-treatment timepoint were classified as MRs. Patients with TF below LOB at baseline and above LOB at the on-treatment timepoint were classified as nMRs.

Statistical Methods

rwOS was defined as the time from on-treatment testing to death, with event-free patients censored at the last known date of follow-up. rwPFS was defined as the time from on-treatment testing to a progression event or death, with event-free patients being right censored at the earliest of ICI medication end date, start of the next line of therapy, or last known date of follow-up. rwPFS and rwOS were compared by MR status using Kaplan–Meier curves, truncated at 18 months after the index date. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) for MR status (MR vs. nMR) and tests for significance were conducted using 2-sided Wald tests at a 5% significance level. Similar analyses were performed for the following subsets of patients: patients treated with ICI monotherapy, patients treated with combination ICI-chemotherapy, and patients with an on-treatment liquid biopsy ≤ 12 weeks after the start of ICI therapy. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were fit to estimate the effect of MR on rwOS and rwPFS after adjustment for cancer cohort.

An additional analysis was performed on the rw-imaging subcohort to evaluate the predictive value of MR in addition to rw-imaging. The date of rw-imaging was used as the index date to evaluate rwOS. A likelihood ratio test at a 5% significance level was used to compare a Cox proportional hazards model incorporating both MR and rw-imaging response (full model) to a model with rw-imaging response as the only covariate (reduced model). The HR for MR status and the associated 95% confidence interval were estimated and provided on the basis of the full model. Median rwOS by MR and rw-imaging response category were estimated from the full Cox proportional hazards model.

Sensitivity Analyses

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the impact of the quantitative threshold used to define MR on rwOS and rwPFS in the evaluable cohort. Specifically, similar to FOCR ctMoniTR, we reevaluated the association between MR and rwOS and rwPFS using different percentage decreases of baseline TF relative to on-treatment TF [26, 27].

Additionally, with the aim of determining how early MR could have hypothetically been used to inform treatment decisions in this cohort, we explored how incrementally shorter on-treatment testing windows, accompanied by concomitant decreases in sample size, impacted associations with rwOS and rwPFS.

Results

Cohort Characteristics

The retrospective pan-solid-tumor evaluable cohort (N = 86) represented patients with non-small cell lung cancer (31.4%, N = 27), breast cancer (14.0%, N = 12), small cell lung cancer (18.6%, N = 16), and 11 additional cancer types (36.0%, N = 31). Median age of the cohort was 65, and 50.0% (N = 43) of the patients were female. Twenty-three percent of the cohort (N = 20) were Asian, Black, African American, or a race other than white. The majority of patients had stage IV disease (88.4%, N = 76). Thirty-eight percent of the cohort (N = 33) were treated with ICI therapy alone and 61.6% (N = 53) were treated with ICI + chemotherapy combinations (Table 1). The majority of patients in the cohort (53.5%, N = 46) were treated with an ICI agent as first-line therapy, while 45.3% (N = 39) of the patients were treated with ICI at or beyond second line (one patient was unknown); further stratified by cancer type in Supplementary Materials Table S1. The median time from baseline testing to ICI start was 15.0 days and the median time from ICI start to on-treatment testing was 91.0 days. Timing of on-treatment testing, dates and outcomes of rw-imaging, and death events when applicable in each group are shown in Fig. 1b.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients evaluable for molecular response analysis

| Category | Overall cohort, N = 86 |

|---|---|

| Cancer indication, n (%) | |

| Breast | 12 (14%) |

| NSCLC | 27 (31.4%) |

| SCLC | 16 (18.6%) |

| Other | 31 (36.0%) |

| Age at ICI Start | |

| Median (range) | 65.1 (39.8–87.3) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 43 (50.0%) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Asian | 2 (2.3%) |

| Black or African American | 13 (15.1%) |

| White | 44 (51.2%) |

| Other | 5 (5.8%) |

| Unknown | 22 (25.6%) |

| Stage, n (%) | |

| Stage III | 8 (9.3%) |

| Stage IV | 76 (88.4%) |

| Unknown | 2 (2.3%) |

| Treatment type, n (%) | |

| ICI monotherapy | 33 (38.4%) |

| ICI + chemotherapy | 53 (61.6%) |

| PD-L1 status, n (%) | |

| Negative | 12 (14.0%) |

| Positive | 13 (15.1%) |

| Unknown | 61 (70.9%) |

| Line of therapy, n (%) | |

| 1L | 46 (53.5%) |

| 2L | 39 (45.3%) |

| Unknown | 1 (1.2%) |

“Other” includes, in order of descending prevalence: melanoma, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, kidney cancer, biliary cancer, bladder cancer, endocrine tumor, head and neck cancer, liver cancer, oropharyngeal cancer

ctDNA TF Correlation with Tumor-Informed TF Outperforms Mean VAF

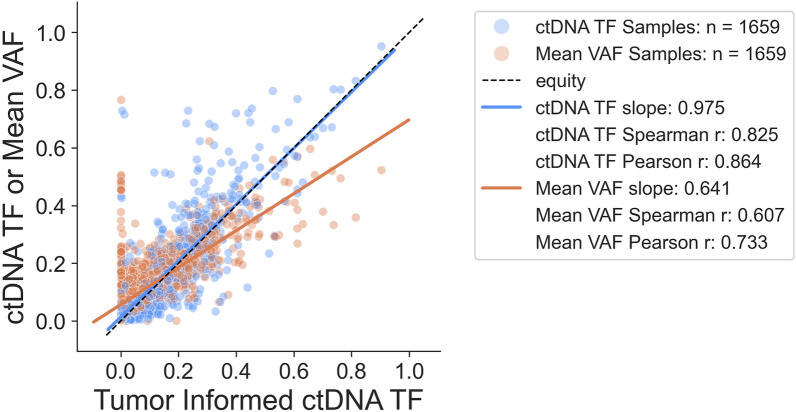

The calculation of the ctDNA TF is described in “Methods” (see Fig. 2). TF linearity was evaluated in a historical pan-cancer cohort (N = 1659 samples) using the tumor-informed TF as a reference (see “Methods”). We compared the linearity of ctDNA TF to that of mean VAF, a common estimate for TF in liquid biopsy. The linearity of ctDNA TF (Pearson R = 0.9, Spearman R = 0.8, slope = 0.9, P < 0.0001) outperformed the mean VAF (Pearson R = 0.7, Spearman R = 0.6, slope = 0.6, P < 0.0001, Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of ctDNA TF with a tumor-informed ctDNA TF. ctDNA circulating tumor DNA, TF tumor fraction, VAF variant allele frequency

We also compared ctDNA TF and mean VAF using randomly selected liquid biopsy samples that underwent LPWGS and ichorCNA TF estimates (see “Methods”, N = 375), an orthogonal measure of ctDNA that had correlation with the tumor-informed ctDNA TF (N = 79 clinical tumor isolates that underwent LPWGS, Pearson R2 = 0.844, Spearman R2 = 0.771, slope = 0.884) [24]. The linearity of the ctDNA TF (Pearson R = 0.9, Spearman R = 0.7, slope = 0.7, P < 0.0001) outperformed the mean VAF (Pearson R = 0.3, Spearman R = 0.4, slope = 0.2, P < 0.0001, Supplementary Materials Fig. S1).

MR Association with RW-Outcomes

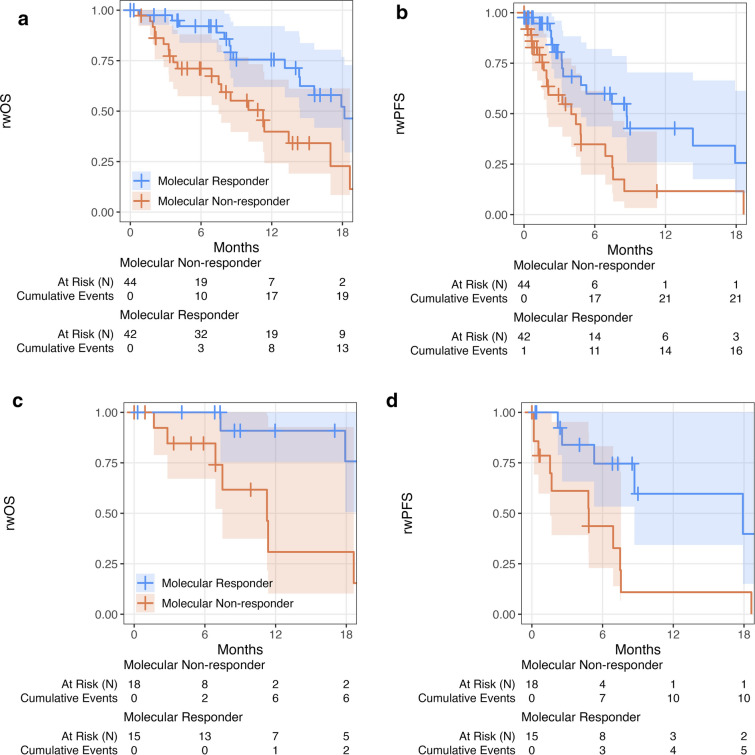

We first evaluated whether MR was associated with rwOS and rwPFS in the evaluable pan-solid tumor cohort (N = 86, ICI ± chemotherapy). Median time from ICI start to on-treatment testing was 88.0 days for patients with MR and 91.5 days for patients with nMR. rwOS was significantly longer among patients with MR (N = 42) versus patients with nMR (N = 44); median rwOS was 18.2 months for patients with MR and 11.3 months for patients with nMR (HR 0.4, 95% CI 0.2–0.7, P = 0.004, Fig. 4a). rwPFS was significantly longer among patients with MR versus patients with nMR, median rwPFS was 8.7 months for patients with MR and 4.0 months for patients with nMR, (HR 0.4, 95% CI 0.2–0.8, P = 0.005, Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Association of ctDNA MR in patients treated with any ICI ± chemotherapy regimen and a rwOS (HR 0.4, P = 0.004) and b rwPFS (HR 0.4, P = 0.005). Association of ctDNA MR in patients treated with ICI monotherapy and c rwOS (HR 0.2, P = 0.02) and d rwPFS (HR 0.2, P = 0.01). ctDNA circulating tumor DNA, HR hazard ratio, ICI immune checkpoint inhibitor, MR molecular response, rwOS real-world overall survival, rwPFS real-world progression free survival

Next we evaluated the association of MR with rwOS and rwPFS in the ICI monotherapy cohort (N = 34) and in the ICI + chemotherapy cohort separately (N = 53). In the ICI monotherapy cohort, rwOS was significantly longer among patients with MR versus patients with nMR, median rwOS was not reached for patients with MR versus 11.3 months for patients with nMR, (HR 0.2, 95% CI 0.05–0.7, P = 0.02, Fig. 4c). In this same ICI alone cohort, rwPFS was also significantly longer in the patients with MR relative to the patients with nMR (median rwPFS was 17.9 months for patients with MR versus 4.8 months for patients with nMR; HR 0.2, 95% CI 0.08–0.7, P = 0.01, Fig. 4d).

Similar trends were seen in rwOS and rwPFS within the ICI + CT cohort, though statistical significance was not reached (Supplementary Materials Fig. S2). rwOS was longer among patients with MR versus those with nMR, with a median rwOS of 14.4 months for patients with MR versus 10.0 months for patients with nMR (HR 0.5, 95% CI 0.2–1.1, P = 0.07, Fig. S2a). rwPFS was longer in the patients with MR relative to the patients with nMR (median rwPFS was 4.8 months for patients with MR versus 3.3 months for patients with nMR; HR 0.5, 95% CI 0.2–1.3, P = 0.2, Fig. S2b).

Given the heterogeneity of cancer types within our pan-cancer cohort, we reevaluated the association of MR with rw-outcomes, while accounting for cancer type. MR was significantly associated with rwOS after adjustment for cancer type (HR 0.4, 95% CI 0.2–0.7, P = 0.004, Supplementary Materials Table S2) and was significantly associated with rwPFS after adjustment for cancer type (HR 0.2, CI 0.1–0.5, P < 0.001, Supplementary Materials Table S3).

Nine patients (9%) whose baseline and on-treatment TF were both below the LOB were considered clinically as TF undetected. Timing of on-treatment testing, rw-imaging, and death events when applicable for patients consistently below LOB are shown in Supplementary Materials Fig. S3. Patient demographics for patients consistently below LOB are shown in Supplementary Materials Table S4. These patients had no death events and were not evaluable for rwOS analysis.

Predictive Value of MR in Addition to RW-Imaging

In the rw-imaging subcohort (N = 51, see “Methods”), we evaluated whether MR had predictive value beyond rw-imaging. Patient demographics for this cohort are shown in Supplementary Materials Table S5. Additionally, timing of on-treatment testing, rw-imaging, and death events are shown in Supplementary Materials Fig. S5. While the majority of patients within this cohort had concordant MR and rw-imaging response results, a subset (35.3%, N = 18) had discordant results (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5.

a Risk stratifications based on MR, rw-imaging response and b predicted rwOS probability using a model combining MR and rw-imaging response (see “Methods”). CR complete response, MR molecular response, PD progressive disease, PR partial response, rwOS real-world overall survival, SD stable disease

We compared a reduced model of rw-imaging only versus a full model (rw-imaging combined with MR) to investigate whether the addition of MR to rw-imaging could better predict rwOS than rw-imaging alone (see “Methods”). Our results show that the full model (HR 0.3, CI 0.1–0.8, P = 0.02 for MR vs. nMR, HR 0.7, CI 0.3–1.5, P = 0.3 for rw-imaging response vs. rw-imaging non-response) is superior in predicting rwOS (P = 0.02) than the reduced model of response via rw-imaging alone (HR 0.5, CI 0.2–1.2, P = 0.1, for rw-imaging response vs. rw-imaging non-response). Patients with nMR and rw-imaging response (N = 13) had a shorter model-predicted median rwOS than patients with MR and rw-imaging response (N = 19, 9.9 months vs. 16.0 months, respectively, Fig. 5b). Similarly, patients with nMR and PD via rw-imaging (N = 14) had a shorter model-predicted median rwOS than patients with MR and PD (N = 5, 7.8 months vs. 15.3 months, respectively, Fig. 5b).

MR Association with RW-Outcomes in Patients with Early On-treatment Timepoints

Given that standard of care CT imaging typically occurs 12 weeks post ICI treatment initiation, we evaluated the association of MR with rwOS and rwPFS for the subset of patients with an on-treatment timepoint ≤ 12 weeks of ICI treatment initiation (N = 40). Timing of on-treatment testing, rw-imaging, and death events are shown in Supplementary Materials Fig. S6. rwOS was significantly longer for patients with MR versus patients with nMR, with median rwOS of 22.4 months for patients with MR versus 11.4 months for patients with nMR (HR 0.2, 95% CI 0.08–0.7, P = 0.01, Supplementary Materials Fig. S7). Similarly, rwPFS was longer among patients with MR versus patients with nMR, though this finding was not statistically significant, with median rwPFS of 8.7 months for patients with MR versus 4.8 months for patients with nMR (HR 0.5, 95% CI 0.2–1.2, P = 0.1 Supplementary Materials Fig. S7). For five patients that had nMR and PD via rw-imaging following their on-treatment liquid biopsy, the median lead time from molecular progression to PD via rw-imaging was 134.0 days.

Sensitivity Analyses

Patients with MR showed consistently longer rwOS and rwPFS than patients with nMR across a broad range of potential MR thresholds (0–90% reduction in TF), demonstrating that our results are robust to the choice of percent-reduction threshold in TF. For rwOS, both the HRs and the corresponding p values trended downward as the threshold for MR became more stringent (Supplementary Materials Fig. S8). For rwPFS, the HRs and p values were similar across the explored range of MR thresholds (Supplementary Materials Fig. S8).

To assess how soon after ICI initiation we could detect significant separation in outcomes between patients with MR and patients with nMR, we reran our analysis using subcohorts with incrementally smaller on-treatment testing windows, from 182 to 28 days post ICI initiation. We observed significant separation in rwOS down to 42 days post ICI (N = 23) and significant separation in rwPFS down to 112 days post ICI (N = 61) (Supplementary Materials Fig. S9).

Discussion

In this study, we clinically validated Tempus xM for TRM, a sensitive, dynamic, and quantitative circulating TF biomarker for ICI response monitoring. Using a ≥ 50% decrease in TF from baseline as the binary threshold to define MR, similar to the threshold used in the results of the meta-analysis of ctMoniTR project led by FOCR and other published data [27–29], we demonstrated that the algorithm can significantly predict rw-outcomes (rwOS and rwPFS) in a clinically diverse RW cohort of patients with advanced, pan-solid-tumors.

Unlike other single input ctDNA biomarkers [27–29], the xM for TRM algorithm utilizes three different types of genomic data (CNV information, somatic VAFs, and germline VAFs) to globally estimate TF. We demonstrated that this algorithm is highly concordant with a tumor-informed method for estimating TF (Fig. 3).

Standard CT imaging response criteria are widely utilized clinically as the single most important modality for determining treatment decisions regarding continuation of ICI therapy. However, nMR may be detected prior to progression on imaging, providing an earlier window to intervene and switch therapy for patients that are not responding, limiting treatment-related toxicity from ineffective therapies, with the potential to improve patient outcomes. In a subset analysis of 40 patients that received an on-treatment liquid biopsy within 12 weeks of ICI treatment initiation, earlier than CT imaging, we observed a significant association of MR with rwOS (which remained significant with an on-treatment liquid biopsy as early as 6 weeks). Similar trends were seen with rwPFS, suggesting that xM for TRM can detect MR within one to two cycles of ICI therapy.

Earlier treatment decisions due to MR results may contribute to a more cost-effective care approach. Given that ICIs cost an average of $10,000 per dose [30, 31], treating nMR with ineffective therapy (e.g., nMR with controlled disease via imaging) may cause significant financial toxicity to the patient and health care system without an outcome benefit. Future research should couple an economic analysis with patient quality of life measures to understand how the use of molecular response biomarkers impact patient-reported and financial outcomes [32–34]. Long-term ICI toxicities include, but are not limited to, cardiac dysfunction, endocrine-like hypothyroidism, immune-related chronic pneumonitis, lung injury, and other rheumatological and neurological organ dysfunction [35].

Furthermore, there remains an inherent clinical gap in CT imaging response criteria, as patients with SD, by virtue of stability, will likely continue on therapy without an outcome benefit, while patients with pseudo-progression, reported in 2–8% of patients with advanced NSCLC receiving ICI [32–34], may be prematurely switched to different therapies [32–34]. In the rw-imaging analysis, we demonstrated that a model incorporating xM for TRM MR and rw-imaging is more predictive of rwOS outcomes than rw-imaging alone, and thus may help in differentiating patients with SD and reducing the incidence of pseudo-progression. Patients with rw-imaging response (CR, PR, or SD) that were nMRs (N = 13) had a shorter predicted rwOS (median model-predicted rwOS of 9.9 months) than those that were MRs (N = 19, median model-predicted rwOS of 16.6 months, Fig. 5). From this analysis, we demonstrated that there is a clear clinical benefit in adding molecular treatment response to standard of care CT imaging in order to predict patient rw-outcomes. Moreover, MR may add additional critical information to standard of care CT imaging results to enable optimal treatment decisions and improve patient outcomes.

ctDNA-guided treatment response monitoring for early identification of MR may be applied to other therapies beyond ICIs. We demonstrated that in subcohorts of patients treated with ICI alone or in combination with chemotherapy, MR was a significant or nearly significant, respectively, predictor of rwOS (Fig. 4, Suppementary Materials Fig. S2). Preliminary data has also shown that ctDNA may be used for TRM to targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors to predict rw-outcomes [36, 37].

The strength of our dataset is that it is derived from a diverse, RW, pan-solid-tumor patient population, who adhere to standard-of-care oncology guidelines that are more representative of clinical practice patterns than clinical trials. Despite the heterogeneity of our patient population across the continuum of RW clinical care, our molecular response assessment emerged as a robust biomarker that can be applied across diverse cancer types and may impact patient treatment decisions. The strengths of RW data have been echoed by recent FDA guidance, which specified the value of RW evidence to support regulatory decision-making for medical devices, recognizing that the wealth of RW data collected during clinical care may help inform or augment the FDA’s understanding of the risk–benefit profile of devices.

A limitation of our RW dataset is that it is retrospective and timing of liquid biopsies and rw-imaging were not pre-specified and are, therefore, heterogeneous. Furthermore, rw-imaging results do not use the stringent Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) independent review measurements utilized in prospective clinical trials. Finally, limitations in sample size restricted further subgroup analysis such as within cancer types and within imaging-specific response groups like SD. Further prospective studies are needed to assess the clinical utility of MR beyond clinical validation studies and whether molecular response-driven treatment changes will improve clinical outcomes.

Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrated that a ctDNA TF biomarker for monitoring response to ICIs, with or without chemotherapy, is predictive of rw-clinical outcomes in a rw-cohort of advanced stage pan-cancer patients. Furthermore, in patients with matched rw-imaging data, we demonstrated that the ctDNA TF biomarker in combination with rw-imaging results in better predictions of rwOS than rw-imaging-based response alone. These data demonstrate the robustness of a dynamic molecular biomarker that can be used clinically to evaluate ICI efficacy.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

The authors thank Vanessa M. Nepomuceno, Ph.D., of Tempus AI, Inc, for providing medical writing and editorial support in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines.

Author Contributions

John Guittar, Akash Mitra, Terri Driessen, Regina Schwind, Seung Won Hyun, Yan Liu, Adam J. Dugan, Halla Nimeiri and Rotem Ben-Shachar contributed to data analysis and manuscript writing. John Guittar, Akash Mitra, Terri Driessen, and Adam J. Dugan generated figures and tables for the manuscript. Ryan D. Gentzler, John Guittar, Akash Mitra, Wade T. Iams, Terri Driessen, Regina Schwind, Michelle M. Stein, Kristiyana Kaneva, Seung Won Hyun, Yan Liu, Adam J. Dugan, Cecile Rose T. Vibat, Chithra Sangli, Jonathan Freaney, Zachary Rivers, Josephine L. Feliciano, Christine Lo, Kate Sasser, Rotem Ben-Shachar, Halla Nimeiri, Jyoti D. Patel and Aadel A. Chaudhuri contributed to study design and results interpretation. All authors contributed to the final review of the manuscript.

Funding

This study and publication costs, including the journal’s Rapid Service Fee were supported by Tempus AI, Inc.

Data Availability

John Guittar, Akash Mitra, Terri Driessen, Rotem Ben-Shachar and Halla Nimeiri had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Deidentified data used in the research was collected in a real-world health care setting and is subject to controlled access for privacy and proprietary reasons. When possible, derived data supporting the findings of this study have been made available within the paper and its Supplementary Figures/Tables.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

John Guittar, Akash Mitra, Terri Driessen, Regina Schwind, Michelle M. Stein, Kristiyana Kaneva, Seung Won Hyun, Yan Liu, Adam J. Dugan, Cecile Rose T. Vibat, Chithra Sangli, Jonathan Freaney, Zachary Rivers, Christine Lo, Kate Sasser, Rotem Ben-Shachar, and Halla Nimeiri are employees of and receive stock options from Tempus AI, Inc. Akash Mitra is an inventor on a provisional patent 63/380,510 submitted by Guardant Health to assess the efficacy of blood tumor mutation burden in predicting response to immune checkpoint blockade in non-small cell lung cancer patients and reports stock ownership with Guardant Health. Wade T. Iams discloses: a consulting or advisory role at Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Amgen, Sanofi, Novocure, Merus, Guardant Health, Tempus AI, EMD Serono, Genentech, AstraZeneca, and Catalyst Pharmaceuticals. Jyoti D. Patel discloses: a consulting or advisory role with Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Takeda Science Foundation, Genentech, and Anheart Therapeutics; travel/accommodation expenses: Tempus AI. Aadel A. Chaudhuri discloses: stock and/or ownership interests with Geneoscopy, Droplet Biosciences and LiquidCellDX; a consulting or advisory role with Geneoscopy, Roche, Illumina, Myriad Genetics, Invitae, AstraZeneca, NuProbe, AlphaSights, GuideBio, Tempus AI, DeciBio, and Daiihi Sankyo; research funding from Roche, Illumina, and Tempus AI; patents, royalties and/or intellectual property with Droplet Biosciences, Tempus AI, LiquidCell Dx, and Biocognitive Labs; honoraria from Agielent, Roche and DAVA Oncology. Ryan D. Gentzler discloses: a consulting or advisory role at AstraZeneca, Takeda, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Regeneron, and Merus; research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck, Takeda, Jounce therapeutics, Pfizer, Mirati Therapeutics, Janssen, RTI International, AstraZeneca, Amgen, Chugai Pharma, Dizal Pharma; honoraria from OncLive, Clinical Care Options, Aptitude Health; travel/accommodation expenses: Tempus AI. Josephine L. Feliciano discloses: consulting or advisory role at AstraZeneca, Merck, Genentech, Pfizer, Lilly, Bristol Myers Squibb, Regeneron, Coherus Biosciences, and Janssen; travel/accommodation expenses: Regeneron; research funding: Merck, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Pfizer.

Ethical Approval

Tempus AI, Inc. has been granted an IRB exemption (Advarra Pro00072742) permitting the use of de-identified clinical, molecular, and multimodal data in order to derive or capture results, insights, or discoveries. All patient-level data were deidentified in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). This study follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: An abstract from the same study was published in the Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer (https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2023-SITC2023.0034) and will be published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology (2024 ASCO annual meeting May 31–June 3, 2024).

Ryan D. Gentzler and John Guittar contributed equally and share co-first authorship.

References

- 1.Leonardi GC, Candido S, Falzone L, Spandidos DA, Libra M. Cutaneous melanoma and the immunotherapy revolution (review). Int J Oncol. 2020;57:609–18. 10.3892/ijo.2020.5088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoneda K, Imanishi N, Ichiki Y, Tanaka F. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J UOEH. 2018;40:173–89. 10.7888/juoeh.40.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai J, Liang P, Li Q, Feng R, Liu J. Cancer immunotherapy—immune checkpoint inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2021;16:239–48. 10.2174/1574892816666210212145107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muraro E, Romanò R, Fanetti G, et al. Tissue and circulating PD-L2: moving from health and immune-mediated diseases to head and neck oncology. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2022;175:103707. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2022.103707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lorusso D, Ceni V, Muratore M, et al. Emerging role of immune checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2020;25:445–53. 10.1080/14728214.2020.1836155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Segal Y, Bukstein F, Raz M, Aizenstein O, Alcalay Y, Gadoth A. PD-1-inhibitor-induced PCA-2 (MAP1B) autoimmunity in a patient with renal cell carcinoma. Cerebellum. 2022;21:328–31. 10.1007/s12311-021-01298-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horn L, Mansfield AS, Szczęsna A, et al. First-line atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2220–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa1809064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paz-Ares L, Ciuleanu T-E, Cobo M, et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab combined with two cycles of chemotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 9LA): an international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:198–211. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30641-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burtness B, Harrington KJ, Greil R, et al. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;394:1915–28. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32591-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cetin B, Gumusay O. Pembrolizumab for early triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;2020:e108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hellmann MD, Paz-Ares L, Bernabe Caro R, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2020–31. 10.1056/NEJMoa1910231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma P, Hu-Lieskovan S, Wargo JA, Ribas A. Primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance to cancer immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;168:707–23. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudin CM, Awad MM, Navarro A, et al. Pembrolizumab or placebo plus etoposide and platinum as first-line therapy for extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: randomized, double-blind, phase III KEYNOTE-604 study. J Clin Orthod. 2020;38:2369–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Castro G, Kudaba K, Wu Y-L, et al. Five-year outcomes with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy as first-line therapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and programmed death ligand-1 tumor proportion score ≥ 1% in the KEYNOTE-042 study. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:1986–91. 10.1200/JCO.21.02885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis AA, Iams WT, Chan D, et al. Early assessment of molecular progression and response by whole-genome circulating tumor DNA in advanced solid tumors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2020;19:1486–96. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-19-1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raja R, Kuziora M, Brohawn PZ, et al. Early Reduction in ctDNA predicts survival in patients with lung and bladder cancer treated with durvalumab. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:6212–22. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Q, Luo J, Wu S, et al. Prognostic and predictive impact of circulating tumor DNA in patients with advanced cancers treated with immune checkpoint blockade. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:1842–53. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kasi PM, Sawyer S, Guilford J, et al. BESPOKE study protocol: a multicentre, prospective observational study to evaluate the impact of circulating tumour DNA guided therapy on patients with colorectal cancer. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e047831. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anagnostou V, Ho C, Nicholas G, et al. ctDNA response after pembrolizumab in non-small cell lung cancer: phase 2 adaptive trial results. Nat Med. 2023;29:2559–69. 10.1038/s41591-023-02598-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anagnostou V, Forde PM, White JR, et al. Dynamics of tumor and immune responses during immune checkpoint blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2019;79:1214–25. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JH, Long GV, Menzies AM, et al. Association between circulating tumor DNA and pseudoprogression in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with anti-programmed cell death 1 antibodies. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:717–21. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finkle JD, Boulos H, Driessen TM, et al. Validation of a liquid biopsy assay with molecular and clinical profiling of circulating tumor DNA. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2021;5:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steele CD, Abbasi A, Islam SMA, et al. Signatures of copy number alterations in human cancer. Nature. 2022;606:984–91. 10.1038/s41586-022-04738-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Driessen T, Lo C, Zhu W, et al. A novel combination of tissue-informed, comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) and non-bespoke blood-based profiling for quantifying circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). Cancer Res. 2024;84:3498. 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2024-3498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adalsteinsson VA, Ha G, Freeman SS, et al. Scalable whole-exome sequencing of cell-free DNA reveals high concordance with metastatic tumors. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1324. 10.1038/s41467-017-00965-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stires H. Collaborative meta-analytical approaches to advance the use of ctDNA in clinical cancer research: the friends of cancer research ctMoniTR project. Nat Commun. 2022;2022:89. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vega DM, Nishimura KK, Zariffa N, et al. Changes in circulating tumor dna reflect clinical benefit across multiple studies of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022;6:e2100372. 10.1200/PO.21.00372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson JC, Carpenter EL, Silva BA, et al. Serial monitoring of circulating tumor DNA by next-generation gene sequencing as a biomarker of response and survival in patients with advanced NSCLC receiving pembrolizumab-based therapy. JCO Precis Oncol. 2021;2021:5. 10.1200/PO.20.00321. 10.1200/PO.20.00321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bratman SV, Yang SYC, Iafolla MAJ, et al. Personalized circulating tumor DNA analysis as a predictive biomarker in solid tumor patients treated with pembrolizumab. Nat Cancer. 2020;1:873–81. 10.1038/s43018-020-0096-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guirgis HM. The impact of PD-L1 on survival and value of the immune check point inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer; proposal, policies and perspective. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:15. 10.1186/s40425-018-0320-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jansen JP, Ragavan MV, Chen C, Douglas MP, Phillips KA. The health inequality impact of liquid biopsy to inform first-line treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a distributional cost-effectiveness analysis. Value Health. 2023;26:1697–710. 10.1016/j.jval.2023.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferrara R, Caramella C, Besse B, Champiat S. Pseudoprogression in non-small cell lung cancer upon immunotherapy: few drops in the ocean? J Thorac Oncol. 2019;2019:328–31. 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katz SI, Hammer M, Bagley SJ, et al. Radiologic pseudoprogression during anti-PD-1 therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:978–86. 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferrara R, Mezquita L, Texier M, et al. Hyperprogressive disease in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors or with single-agent chemotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1543–52. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson DB, Nebhan CA, Moslehi JJ, Balko JM. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors: long-term implications of toxicity. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:254–67. 10.1038/s41571-022-00600-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mack PC, Miao J, Redman MW, et al. Circulating tumor DNA kinetics predict progression-free and overall survival in EGFR TKI-treated patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC (SWOG S1403). Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28:3752–60. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-0741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soo RA, Martini J-F, van der Wekken AJ, et al. Early circulating tumor DNA dynamics and efficacy of lorlatinib in patients with treatment-naive, advanced ALK-positive NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2023;18:1568–80. 10.1016/j.jtho.2023.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

John Guittar, Akash Mitra, Terri Driessen, Rotem Ben-Shachar and Halla Nimeiri had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Deidentified data used in the research was collected in a real-world health care setting and is subject to controlled access for privacy and proprietary reasons. When possible, derived data supporting the findings of this study have been made available within the paper and its Supplementary Figures/Tables.