Abstract

Introduction

Hepatic visceral crisis (VC), characterized by a rapid total bilirubin increase with disease progression, poses a life-threatening risk in advanced breast cancer (ABC). International consensus guidelines define VC and touch on impending VC (IVC). Limited data exist on systemic treatments for hepatic VC/IVC. This study explores the safety and efficacy of cisplatin monotherapy in patients with Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2- negative breast cancer (BC) and hepatic IVC/VC.

Methods

In this retrospective single-center cohort study data of patients treated with cisplatin monotherapy (60–80 mg/m2, every 3–4 weeks) between 2016 and 2023 at a reference Cancer Centre in Southern Poland were analyzed.

Results

33 female patients (24/33 hormonal-positive) with the mean age 53.84 years were included. Participants progressed on median 2 prior palliative systemic treatment lines. In 10/23 patients hepatic VC and in 23/33 IVC (rapid, symptomatic liver progression; extensive liver involvement; alanine or aspartate aminotransferase > 2 × normal limit; significant increases in lactate dehydrogenase, alkaline phosphatase, or gamma-glutamyl transferase) were identified. Median progression-free survival was 1.87 months and median overall survival 2.67 months. 33% of the patients presented stable disease or partial response. Eight patients experienced adverse events grade ≥ 3: in five the dose of cisplatin was reduced; two stopped the treatment.

Conclusion

Due to the hepatotoxicity of BC-active drugs, specific recommendations for systemic treatment are scarce. Our study explored cisplatin's potential use, finding it to be a viable option in patients with performance status 0 or 1 experiencing hepatic IVC/VC, irrespective of liver function parameters and other factors.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40487-024-00280-9.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Visceral crisis, Overall survival, Metastases, Chemotherapy, Cisplatin

Key Summary Points

| Limited options exist for patients with breast cancer (BC) and active hepatic visceral crisis (VC). Lack of specific recommendations for systemic treatment in liver failure is due to the hepatotoxic nature of most drugs effective in BC. |

| This real-world retrospective single-center cohort study investigates the efficacy and safety of cisplatin monotherapy in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative, hormone receptor-positive BC treated between 2016 and 2023 who experienced impending hepatic VC or VC. |

| Among 33 female patients, median progression-free survival was 1.9 months, and median overall survival was 2.7 months, with 33% of patients showing stable disease or partial response. The treatment was well tolerated. |

| Cisplatin monotherapy showed potential as a treatment option, particularly for patients with good performance status (0 or 1), regardless of liver function parameters. |

| These findings underscore a need for academic clinical trials addressing this pressing medical gap. |

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most prevalent cancer and the leading cause of cancer deaths among women worldwide [1]. Although up to 90% of cases are diagnosed in the early stages (I-III) and treated with curative intent, recurrence occurs in 20–30%. The diagnosis rate of de novo advanced breast cancer (ABC) (stage IV) is approximately 6% [2]. The clinical presentation of BC dissemination is heterogeneous, ranging from asymptomatic metastases found in imaging procedures, through pain, respiratory, abdominal, and neurological symptoms, to life-threatening organ dysfunctions. The appearance of critical organ impairment is referred to as 'visceral crisis' (VC), occurring in about 10–15% of ABC diagnoses [3].

According to the fifth European School of Oncology (ESO)—European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 5), VC is defined as severe organ dysfunction, assessed through signs and symptoms, laboratory studies, and rapid disease progression [3]. In routine clinical practice, the primary manifestations of VC include pulmonary lymphangitis carcinomatosa with dyspnea, bone marrow metastasis with hematopoietic dysfunction, diffuse liver metastasis with laboratory tests confirming liver insufficiency, leptomeningeal carcinomatosis with signs of meningeal irritation, and superior vena cava syndrome caused by lymph node compression [4]. The ABC 5 definition of VC is not stringent and allows for individual interpretation of the clinical situation by the physician. Therefore, the ABC 5 guidelines also specify that the presence of VC must prompt an urgent need for the most effective therapy and outline a few clinical scenarios [3].

The most common type of VC is associated with diffuse liver metastases [4, 5]. It is characterized by a rapid increase in total bilirubin > 1.5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), in the absence of Gilbert's syndrome or biliary tract obstruction [3]. However, in retrospective trials, criteria for liver VC vary, including not only hyperbilirubinemia > 1.5 ULN, but also a combination of it with elevated aminotransferases (aspartate and/or alanine aminotransferases [AST and/or ALT] > 1.5 ULN or AST > 200 U/L, ALT > 200 U/L) [5, 6]. In some cohort series, hepatic VC is simply referred to as liver dysfunction or impairment without specific cutoffs for laboratory tests [4, 7]. A complex scenario to subjectively delineate is the presence of an 'impending visceral crisis' (IVC) marked by conditions that do not align with the ABC 5 criteria for VC, but are expected to unfold without swift and effective interventions. For example, a situation where the majority of the liver is occupied by metastases, causing notable changes in liver enzymes while bilirubin level still remains within the normal range.The recommended clinical management of VC is the most efficacious therapy, which depends on BC subtype and germline BReast CAncer susceptibility genes (BRCA) status [3, 8]. VC predominantly arises in the hormone receptor-positive (HR +) Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2)-negative subtype, owing to the epidemiology and unique natural history of the disease. Limited data, mainly retrospective analyses, regarding the systemic treatment for hepatic VC in patients with HER2-negative BC are summarized in Supplementary Materials (Table S1 [4–6, 9–11]).

Cisplatin, also known as (SP-4–2)-diamminedichloridoplatinum(II), is a widely used and potent chemotherapy agent for various solid cancers. Its mechanism of action involves interaction with purine bases, generating inter-strand and intra-strand crosslinks in DNA leading to DNA damage; activation of signal transduction pathways culminating in apoptosis; inhibition of cancer metastasis e.g., by blocking early steps of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [12–16]. However, challenges like side effects and drug resistance persist, prompting the use of combination therapies for enhanced efficacy [12–17].

The aim of this retrospective single center cohort study was to assess the safety and efficacy of cisplatin monotherapy used in a population of patients with HER2-negative BC presenting with hepatic IVC/VC. The second goal was to propose a predictive factor to define a population which could benefit from cisplatin monotherapy in this setting.

Methods

That is a single-center retrospective cohort study conducted according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

Patients

Patients who received a diagnosis of BC were identified through the hospital registry system at the Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology Branch Krakow. The subset of interest included those who had cisplatin monotherapy initiated between September 2016 and May 2023. Specifically, only patients with hepatic VC or impeding hepatic VC were eligible for inclusion. Other criteria for inclusion involved individuals with a confirmed BC diagnosis in either postsurgical or core biopsy pathology reports. Exclusion criteria encompassed patients without an original pathology report, tumors classified as HER2 positive (in any available immunohistochemistry or fluorescence in situ hybridization [FISH]), or those concurrently dealing with other active malignancies. There were no limitations based on gender or age.

Information pertaining to age and gender, histopathological data (including histology, estrogen receptor [ER], progesterone receptor [PgR], HER-2, Ki-67 status, presence of ductal carcinoma in situ [DCIS]), tumor grade as well as clinical details such as staging, location of metastatic disease, number and size of metastatic lesions, dates and types of previous systemic treatment, survival status, response rates, dates of disease progression, reason for treatment discontinuation, dates of the last visit, numerous laboratory data: ALT, AST, total bilirubin, morphology, alkaline phosphatase, lactate dehydrogenase [LDH], comorbidities, performance status (PS) and BRCA germline mutation status were collected. Information on the dates of cisplatin administration, dosage details, regimen types, and the associated side effects of the treatment was also gathered. Grading of adverse events (AEs) was performed using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v 5.0. The deadline for follow-up in the study was 31st December 2023.

Definitions

Hepatic VC is characterized by the coexistence of documented liver metastases identified through imaging studies (such as ultrasound, computerized tomography, positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging) prior to study entry and by abnormalities in hepatic tests, including hyperbilirubinemia (> 1.5 ULN]) observed at the initiation of cisplatin treatment in the absence of Gilbert syndrome. Hepatic IVC is diagnosed in individuals with a significant portion of the liver occupied by metastases, rapid progression evident in recent imaging studies, and a swift increase in liver enzymes, including but not limited to elevated AST and/or ALT (> 1.5 ULN). These manifestations are attributed to rapid disease progression and the liver burden associated with clinical symptoms. These definitions reflect the 5th ESO-ESMO international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 5) [3].

Overall survival (OS) is calculated as the time from the initiation of cisplatin to the date of death, while progression-free survival (PFS) as the time from cisplatin initiation to death or progression. Patients are categorized as having received treatment in the final month of their lives if the duration between these two dates was 30 days [5].

The response to treatment is assessed as stable disease (SD), partial response (PR), or complete response (CR) in imaging studies. Non-responders are defined as patients who experience progressive disease (PD) as the best radiological response, according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1 criteria, or patients who experience clinical progression or die due to disease progression before the planned radiological assessment.

Ethical Considerations

The Ethical Committee of the Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology Branch Krakow granted ethical approval, as indicated by decision number 1/2023 dated 18 April 2023. In accordance with the Ethical Committee's decision, written informed consent was not mandatory due to the retrospective nature of the study. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional Ethical Committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Statistical Considerations

Univariate logistic regression was employed to model the impact of potential predictors on a dichotomous variable. odds ratios (ORs) alongside the 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were presented. Univariate Cox regression (proportional hazards model) was employed to model the impact of potential predictors on a time to event. Hazard ratios (HRs), alongside the 95% CIs, were presented.

Conditional Inference Tree (CTree) algorithm was used to derive groups of patients that differ in probability of radiological response to the treatment. There were numerous factors assessed: PS; patient's age; blood laboratory parameters including levels of ALT, AST, bilirubin, or LDH, comorbidities; location, size and number of metastases; the coexistence of a second visceral crisis; and a history of previously received treatment.

Significance level was set to 0.05. All the analyses were conducted in R software, version 4.3.2.

Results

Population Characteristics

33 female participants entered the study with the mean age (standard deviation [sd]) 53.84 years (11.6) and median age (quartiles) 54.26 age (44.64–61.32) (range 34.75–77.14).

Population characteristics regarding clinicopathological data as well as the previous treatment received are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological patients characteristics

| Parameter | Total (N = 33) | |

|---|---|---|

| Time from primary diagnosis to cisplatin treatment [years] | Mean (sd) | 4.62 (3.35) |

| Median (quartiles) | 4.22 (2–5.34) | |

| Range | 0.73–15.36 | |

| n | 33 | |

| Time from dissemination to the liver to cisplatin treatment [months] | Mean (sd) | 11.91 (11.71) |

| Median (quartiles) | 9.13 (1.48–18) | |

| Range | 0.03–39.49 | |

| n | 33 | |

| Time from hepatic IVC/VC diagnosis to cisplatin treatment [months] | Mean (sd) | 2.32 (2.74) |

| Median (quartiles) | 1.28 (0.13–3.65) | |

| Range | 0–9.72 | |

| n | 33 | |

| Primary BC diagnosis | Local or locoregional | 26 (78.79%) |

| Disseminated disease | 7 (21.21%) | |

| Prior systemic palliative treatment | No | 8 (24.24%) |

| Yes | 25 (75.76%) | |

| Number of prior palliative systemic treatment lines | Mean (sd) | 1.97 (1.57) |

| Median (quartiles) | 2 (1–3) | |

| Range | 0–5 | |

| n | 33 | |

| Number of prior palliative chemotherapy lines | Mean (sd) | 1.09 (1.1) |

| Median (quartiles) | 1 (0–2) | |

| Range | 0–4 | |

| n | 33 | |

| Number of prior palliative systemic treatment lines administered due to hepatic IVC/VC | Mean (sd) | 0.39 (0.62) |

| Median (quartiles) | 0 (0–1) | |

| Range | 0–2 | |

| n | 32 | |

| Previous exposure to anthracyclines | No | 3 (9.09%) |

| Yes | 30 (90.91%) | |

| Previous exposure to taxanes | No | 7 (21.21%) |

| Yes | 26 (78.79%) | |

| Previous exposure to platins | No | 31 (93.94%) |

| Yes | 2 (6.06%) | |

| Progression after anthracyclines and taxanes | No | 9 (27.27%) |

| Yes | 24 (72.73%) | |

| HR positive status | No | 9 (27.27%) |

| Yes | 24 (72.73%) | |

| BC subtype | Luminal A | 5 (15.15%) |

| Luminal B | 19 (57.58%) | |

| TNBC | 9 (27.27%) | |

| Ki67 [%] | Mean (sd) | 34.91 (22.19) |

| Median (quartiles) | 30 (20–38.75) | |

| Range | 7–95 | |

| n | 22 | |

| Largest liver metastatic tumor size [mm] | Mean (sd) | 57.5 (32.03) |

| Median (quartiles) | 57 (32.25–75.75) | |

| Range | 11–150 | |

| n | 30 | |

| Number of liver metastases |

1–3 4–10 > 10 |

2 (6.06%) 2 (6.06%) 29 (87.88%) |

| Dissemination to sites other than liver | No | 3 (9.09%) |

| Yes | 30 (90.91%) | |

| Coexisting VC other than hepatic | No | 29 (87.88%) |

| Yes | 4 (12.12%) | |

| Increase in total bilirubin level meeting the ABC 5 criteria for VC |

No Yes |

23 (69.70) 10 (30.30) |

| Comorbidities | No | 28 (84.85%) |

| Yes | 5 (15.15%) | |

| Postmenopausal status | No | 10 (30.30%) |

| Yes | 23 (69.70%) | |

| Performance status | 0 | 1 (3.03%) |

| 1 | 14 (42.42%) | |

| 2 | 11 (33.33%) | |

| 3 | 7 (21.21%) | |

| Platelets level [109/l] (normal range: 150–400) | Mean (sd) | 298.36 (138.16) |

| Median (quartiles) | 285 (191–410) | |

| Range | 63–688 | |

| n | 33 | |

| Abnormal platelets level | No | 23 (69.70%) |

| Yes | 10 (30.30%) | |

| Platelets to lymphocytes ratio | Mean (sd) | 285.85 (188.06) |

| Median (quartiles) | 228.57 (152.5–391.43) | |

| Range | 84.76–1051.28 | |

| n | 33 | |

| Hemoglobin level [g/dl] (normal range: 12–16) | Mean (sd) | 12.35 (2) |

| Median (quartiles) | 12.3 (10.7–13.9) | |

| Range | 8.5–16.4 | |

| n | 33 | |

| Anemia grade* | None | 20 (60.61%) |

| Grade 1 | 4 (12.12%) | |

| Grade 2 | 9 (27.27%) | |

| Neutrophiles [109/l] (normal range: 2.2–7.0) | Mean (sd) | 7.47 (4.62) |

| Median (quartiles) | 6.44 (4.09–8.74) | |

| Range | 1.66–18.11 | |

| n | 33 | |

| Lymphocytes [109/l] (normal range: 1.0–3.5) | Mean (sd) | 1.21 (0.47) |

| Median (quartiles) | 1.11 (0.9–1.55) | |

| Range | 0.35–2.22 | |

| n | 33 | |

| Neutrophiles to lymphocytes ratio | Mean (sd) | 7.74 (8.15) |

| Median (quartiles) | 4.87 (3.92–8.5) | |

| Range | 1–46.44 | |

| n | 33 | |

| ALT [U/l] (normal range: 5–35) | Mean (sd) | 106.58 (68.88) |

| Median (quartiles) | 101 (55–144.7) | |

| Range | 13–274 | |

| n | 33 | |

| AST [U/l] (normal range: 5–32) | Mean (sd) | 186.84 (154.8) |

| Median (quartiles) | 135 (73–250) | |

| Range | 14.1–645 | |

| n | 33 | |

| Highest grade of transaminases elevation | None | 0 (0.00%) |

| Grade 1 | 12 (36.36%) | |

| Grade 2 | 8 (24.24%) | |

| Grade 3 | 12 (36.36%) | |

| Grade 4 | 1 (3.03%) | |

| AST/ALT | Mean (sd) | 1.94 (1.21) |

| Median (quartiles) | 1.69 (1.02–2.48) | |

| Range | 0.23–5.62 | |

| n | 33 | |

| Alkaline phosphatase [U/l] (normal range: 35–104) | Mean (sd) | 509.83 (352.84) |

| Median (quartiles) | 436 (198–745) | |

| Range | 61.2–1606 | |

| n | 33 | |

| GGTP [U/l] (normal range: 5–45) | Mean (sd) | 890.94 (800.99) |

| Median (quartiles) | 635 (296–1363) | |

| Range | 53–3070 | |

| n | 33 | |

| Total bilirubin [µmol/l] (normal range: 2.0–18.0) | Mean (sd) | 34.15 (62.04) |

| Median (quartiles) | 16.7 (8.2–22.1) | |

| Range | 3.8–330.3 | |

| n | 33 | |

| LDH [U/l] (normal range: 100–214) | Mean (sd) | 1100.6 (1174.81) |

| Median (quartiles) | 710 (395.2–990.5) | |

| Range | 184–4733 | |

| n | 33 | |

| Significant electrolyte disturbances* | No | 28 (84.85%) |

| Yes | (15.15%) | |

ABC/BC advanced/ breast cancer, ALT alanine transaminase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, GGTP gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, HR hormone receptor, IVC/VC impending/visceral crisis, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, sd standard deviation

*Requiring pharmacological intervention

All patients identified as hepatic IVC had a recent diagnosis of rapid liver progression, with a majority of the organ involved. Additionally, ALT or AST was elevated (minimum > 2 × ULN, although > 1.5 × ULN was required by the definition), and there were significant increases in LDH, alkaline phosphatase, or GGTP, along with the presence of disease symptoms.

The most common other sites of metastatic disease were bones in 21 patients (63.64%); lungs in 14 patients (42.42%) and distal lymph nodes in 13 patients (39.39%). In 25 patients (75.76%) BRCA mutation status remained unknown, with only 1 patient with known BRCA1 mutation.

Mean time from the diagnosis of disseminated disease to IVC/VC was 18.16 months (sd, 18.6) while mean time from the diagnosis of disseminated disease to the liver to IVC/VC was 9.59 months (sd, 11.15).

Current and Previous Therapy

Patients received median dose of 70 mg/m2 of cisplatin (range 60-80 mg) per one cycle in single dose (15 patients, 45.45%), during 2-day cycle (16 patients, 48.48%) or 3 day-cycle (2 patients, 6.06%) every 3–4 weeks. Patients underwent one to six cycles of cisplatin chemotherapy (median: 1, mean: 2.42 cycles): 17 patients (51.52%) received only one cycle, 6 patients (18.18%) two cycles and 10 patients (30.30%) ≥ 3 cycles of cisplatin. Twelve (36.36%) patients started subsequent lines of treatment after progression on cisplatin (including 2 patients who received 2 subsequent lines of palliative systemic treatment). Only in six (18.18%) patients did laboratory parameters normalize (after median number of cycles 2.5). None of the parameters, whether clinical or laboratory, correlated with laboratory parameters normalization (p > 0.05).

Eight (24.24%) patients received one line of treatment (prior to cisplatin monotherapy), and two (6.06%) patients received two lines of treatment while already being diagnosed with IVC/VC. The regimens were anthracycline-based (in 6 cases), taxanes (2 cases), capecitabine (2 cases), and hormonal agents (2 cases).

Treatment Safety Data

Two (6.06%) patients stopped the treatment due to AEs. These included nephrotoxicity G2 as per CTCAE v 5.0 in one patients and recurrent neutropenia G3 in one patient. In three (9.09%) patients we have observed hepatotoxicity G4, but at the same time disease progression was documented in all these patients and hepatotoxicity was assessed as not related to cisplatin. Eight (24.24%) patients experienced AEs grade 3 or higher including: fatigue (4 cases), hepatotoxicity (3 cases, already mentioned) and neutropenia (1 case). In 5 (15.15%) patients the dose of cisplatin was reduced due to poor treatment tolerance. In 1 (3.03%) patient the treatment was ceased after 5 cycles and in 4 after 6 cycles due to ‘maximal clinical benefit’. In four of these patients progression was noted within one month, in one patient hormonal therapy was initiated and that patients experienced longer response.

Progression-Free Survival

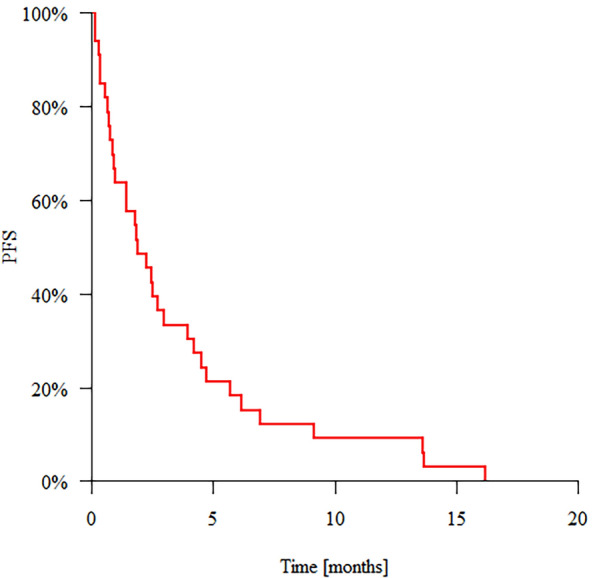

Data regarding PFS are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 1.

Table 2.

Data regarding progression-free survival

| Patients | Events | Progression-free survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 months | 3 months | 6 months | Median [months] | ||

| 33 | 33 | 63.64% | 33.33% | 18.18% | 1.87 |

Fig. 1.

Progression-free survival (PFS)

Overall Survival

Data regarding OS are presented in Table 3 and Fig. 2.

Table 3.

Data regarding overall survival

| Patients | Events | Overall survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 months | 3 months | 6 months | Median [months] | ||

| 33 | 33 | 69.70% | 45.45% | 36.36% | 2.69 |

Fig. 2.

Overall survival (OS)

Factors Influencing Progression-Free Survival and Overall Survival

Due to low patient number only univariate Cox analysis was performed showing that PS ≥ 2 increases the probability of progression or death at any given time by 3.143 times (HR = 3.143) compared to PS 0 or 1; each additional 109/l neutrophils by 14.8% (HR = 1.148); an increase in the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio by 1 by 7.3% (HR = 1.073), each additional 1 U/l ALT by 0.6% (HR = 1.006) each additional U/l AST by 0.4% (because HR = 1.004), elevation of transaminases of grade ≥ 3 by 2.413 times (HR = 2.413) compared to elevation of grade 1.

In terms of factors influencing OS: the coexisting VC other than hepatic increases the probability of death at any given time by 3.738 times (HR = 3.738); PS ≥ 2 by 2.949 times (HR = 2.949) compared to PS 0 or 1, each additional 109/l neutrophils by 18.0% (HR = 1.18), an increase in the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio by 1 by 8.6% (HR = 1.086), each additional 1 U/l ALT by 0.6% (HR = 1.006), each additional 1 U/l AST by 0.3% (HR = 1.003).

Number of prior palliative systemic treatment lines, number of prior palliative chemotherapy lines, number of prior palliative systemic treatment lines administered due to hepatic IVC/VC; prior usage of anthracyclines or/and taxanes did not influence OS or PFS in our population.

Tables S2 and S3 in Supplementary Materials show analysis for all factors influencing PFS and OS.

Patients Receiving the Treatment in the Final Month of Life

There were 9 patients (27.27%) in whom the treatment with cisplatin was initiated within the last 30 days of life. Univariate logistic regression model showed that: coexisting VC other than hepatic increases risk of death within a month by 11.2 times (OR = 11.2); PS ≥ 2 by 11.2 times (OR = 11.2) compared to PS 0 or 1; each additional 109/l neutrophils by 32.0% (OR = 1.32); an increase in the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio by 1 by 37.0% (OR = 1.37) and each additional 1 U/l increase in AST by 0.6% (OR = 1.006). Analysis of factors influencing the risk of dying within a month after day 1 cycle 1 is presented in Table S4 in Suppementary Materials.

Best Response to the Treatment

11 patients (33.33%) had SD or PR as per RECIST 1.1 criteria as the best response to the treatment. Mean time from the first day of the first cycle of cisplatin administration to imaging studies was 2.68 months (SD, 1.37). Univariate logistic regression model showed that: PS ≥ 2 decreased the chances of present response to the treatment by 97.1% (OR = 0.029) when compared to PS ≤ 1. Whole analysis regarding resent response to the treatment it presented in Table S5 in Supplemetary Marierials.

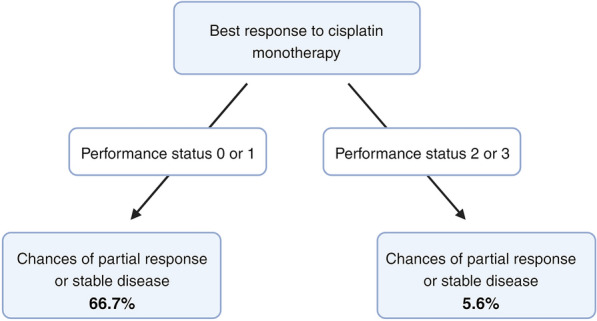

Using the CTree algorithm allowed to assess that patients with PS 0 or 1 (15 patients [45.45%] in our population) have a 66.67% chance of achieving SD or PR, while patients with PS 2 or 3 (18 patients [54.55%]) have a 5.6% chance of achieving an SD or PR. No additional parameters improved or enhanced the prediction. The results are presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Conditional Inference Tree algorithm grouping for differences in the probability of radiological response to the treatment as per RECIST 1.1 criteria

Discussion

In this paper, we present the study assessing the safety and efficacy of cisplatin monotherapy in patients with HER2-negative BC and impeding or ongoing hepatic VC. We also discuss the factors that should be considered when determining the eligibility of patients for this particular treatment.

Systemic treatment of patients with BC and VC is the only situation in which guidelines recommend a different treatment over the first-line standard one. Interestingly, the phase II RIGHT Choice trial, presented at the 2022 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, was the first prospective study to evaluate a Cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6 inhibitor (CDK4/6i) combined with an aromatase inhibitor (AI) versus combination chemotherapy (CTH) [18]. Careful analysis of the inclusion and exclusion criteria reveals that the study population comprised patients with clinically aggressive disease, not VC. Consequently, the study did not alter the management of HR + /HER2-negaive ABC with VC. CTH is favored over endocrine therapy (ET), and polychemotherapy is favored over single-agent CTH [3, 8, 19]. This recommendation is substantiated by data indicating a higher objective response rate (ORR) and longer PFS, with no significant benefit reported for OS [20, 21]. However, the preferred CTH regimen is not specified. The decision made by the physician is highly challenging, and its difficulties stem from several factors. Firstly, VC is a common exclusion criterion from clinical trials. Safety and treatment efficacy data are mainly obtained from retrospective series (see Table S1 in Supplementary Materials). Secondly, the decision-making process is based on a subjective evaluation of a constellation of patient and drug features, such as the toxicity profile, PS, and hepatic metabolism. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), but not ESMO guidelines, recommend poly ADP-ribose polymerase inhibitors (PARPi) for BRCA mutation carriers in the case of VC as a first-line treatment, irrespective of the BC subtype [8]. The treatment of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and HER2-positive ABC with VC aligns with guidelines [3, 8, 19]. For TNBC, it depends on the BRCA and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) status, tested by the combined positive score (CPS). Deciding on subsequent therapy lines becomes even more challenging due to the poor prognosis, compromised PS, and lack of specific recommendations; hence, the consideration of best supportive care should always be taken into account.

Cisplatin is not among preferred choices for HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer (mBC) as for ESMO or NCCN guidelines. According to NCCN guidelines cisplatin in HER2-negative BC is only recommended as an option (as category 1, preferred) in case of PD-L1 CPS < 10 and germline BRCA1/2 mutation [8]. ESMO Metastatic Breast Cancer Living Guideline for mTNBC do not mention cisplatin, while carboplatin stays as an option for first line combine treatment with pembrolizumab in patients with PD-L1 + status and platins are preferred among other chemotherapy agents in individuals with BRCA mutation. In the ESMO Metastatic Breast Cancer Living Guideline for metastatic hormone-positive HER2-negative BC platins are used as one of the options for patients with tumors that are endocrine resistant or in patients at risk of imminent organ failure [22, 23].

Cisplatin is generally not regarded as hepatotoxic. It has been linked to a low incidence of mild hepatic enzyme elevations during treatment. Instances of clinically evident liver injury attributed to cisplatin have been rarely reported [24]. Cisplatin has been used in BC setting for decades [25, 26], although a meta-analysis examining platinum-containing treatment approaches for metastatic breast cancer indicates that, in women without TNBC, there is substantial evidence suggesting minimal to no survival advantage and an increased risk of toxicity associated with platinum-based regimens. However, there is less robust evidence suggesting a moderate survival benefit for women with metastatic TNBC undergoing platinum-based treatments. That meta-analysis did not include patients with hepatic IVC/VC [27]. While it is claimed that cisplatin activity in ABC decreases with number of prior systemic treatment lines [25], this was not confirmed in our cohort. Data regarding the potentially effective dose were published more than 40 years ago, suggesting doses higher than 100 mg/m2 to be potentially active, with doses close to the ones used in our study 60 mg/m2 being inactive [26, 28]. However, a study by Isakoff and colleagues regarding the treatment of metastatic TNBC advocated for a dose of 75 mg/m2 to be effective, showing even with higher numerical response rates than carboplatin in first or second-line treatment [29].

Even though, one third of patients with IVC/VC in our study achieved PR or SD, it is still much worse effect than in most recent studies of pretreated patients with HER2-negative BC without IVC/VC on CTH and also in studies regarding patients with IVC/VC ([30, 31] see Table S1 in Supplementary Materials). However real-world data should not be compared with data obtained in randomized controlled trials. Furthermore, the response to treatment had not remained for a long time—PFS is also much shorter than it was reported in the literature (see Table S1 in Supplementary Materials).

Our patients presented with a very poor OS. Similar outcomes are confirmed in some studies [11], but other papers report much longer survival [4, 10]. The reason for these differences can be an unclear/changing hepatic IVC/VC definition, a heterogenous population that includes all types of VC or different BC subtypes included (see Table S1 in Supplementary Materials).

The safety assessment of the treatment did not uncover any new data in comparison to those already known from cisplatin product characteristics. Some of the AEs overlapped with ABC symptoms, and the relationship between cisplatin activity and a symptom was evaluated on a case-by-case basis [13–16, 24]. There is a question regarding chemotherapy cessation after obtaining maximal clinical benefit, observed in five patients in our population. All of them, except for one who initiated hormonal therapy, experienced prompt progression. While initiating maintenance hormonal therapy appears to be a common and reasonable clinical practice, data regarding cisplatin continuation or switching to another type of maintenance systemic treatment are scarce, with only retrospective studies addressing patients with BC receiving platinum doublets [33].

PS is frequently named as a factor influencing patients’ survival, also in patients with BC and VC, confirming our results [4]. There are efforts to incorporate more complex scoring systems in order to predict OS in patients with hepatic VC [34]. Interestingly, in our study, PS could not only serve as a prognostic factor but also differentiate between groups in terms of predicting the response to cisplatin treatment. Almost one-third of our patients were administered treatment in the last 30 days of life, which might have had a negative impact on patients' quality of life, causing unnecessary suffering and costs [35]. Avoiding such situations is an important but challenging task in daily clinical practice. While we suggest as simple parameter as PS to distinguish between patients that are more prone to experience better treatment response, there are case reports suggesting potential benefit in patients with poor PS, however with no known hepatic IVC/VC [32]. At the same time, none of the other tested factors served as a predictive parameter when tested using the CTree algorithm.

Study Limitations

There are several primary limitations of this study: (1) it is a single-center analysis, (2) the population is relatively small, (3) it is retrospective in nature, (4) it includes patients with hepatic IVC, not exclusively those with VC and (5) the population is heterogenous as it includes patients with TNBC and luminal BC (mostly, hormone-resistant BC). We chose not to include patients treated before the end of 2016, as that population was managed differently before the era of CDK4/6 inhibitors, and the results might not accurately reflect the current everyday practice. However, despite these limitations, this study remains one of the largest evaluating the role of cisplatin in this cohort of patients with BC with an unfavorable prognosis. Notably, there are no studies (see Table S1 in Supplementary Materials) assessing the role of cisplatin monotherapy in this specific setting. Other published papers: (1) either do not specify which platinum agent was used or present highly heterogeneous treatment options with various platinum partners, (2) use various, outdated or unclear definitions for VC and IVC and (3) encompass populations of patients with both HER2-positive and negative BC collectively.

In our study, all patients identified with hepatic IVC had a recent diagnosis of rapid liver progression, with a majority of the organ involved. Additionally, ALT or AST was elevated (with minimum > 2 × ULN), and there were significant increases in LDH, alkaline phosphatase, or GGTP, along with the presence of disease symptoms. Thus, our criteria for IVC, not precisely defined in ABC 5, were strict [3]

For individuals with extensive or rapidly progressing VC, combination chemotherapy might be considered suitable as per available guidelines [3, 8]. In such cases, the anticipated higher response rates are weighed against the elevated risks of toxicity, primarily due to concerns about imminent organ dysfunction. Still, there is a lack of prospective data demonstrating that combination chemotherapy enhances OS when compared to the use of single-agent chemotherapy [36]. Moreover, there are practically no viable options for platinum partners in heavily pretreated patients with liver insufficiency.

Conclusions

The demarcation between IVC and ongoing VC lacks precise definition. While guidelines are available for patients with HER2-negative breast cancer confronting an impending VC in general, choices for those experiencing an active hepatic VC are cenetr severely limited. There are no specific recommendations for systemic treatment in patients with liver failure, given that most drugs displaying activity in BC possess hepatotoxic properties. Our study sought to investigate whether the utilization of cisplatin—an established agent with low hepatotoxicity—could be warranted in the absence of evidence from randomized clinical trials.

We conclude that cisplatin may be a viable option in patients with PS 0 or 1 who have hepatic IVC/VC. Simultaneously, patients with PS ≥ 2 should be disqualified from cisplatin monotherapy, offered best supportive care and considered for alternative forms of therapy if feasible. Other factors, such as the patient's age, blood laboratory parameters including levels of ALT, AST, bilirubin, or LDH, the coexistence of a second visceral crisis, and a history of previously received treatment, did not manage to differentiate between groups of patients who could benefit in this setting. These data led to a change in the local policy at the Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology. While we still consider each patient on a case-by-case basis, patients with HER-2-negative BC with hepatic VC/IVC and PS 0–1 are candidates for cisplatin monotherapy, regardless of other factors traditionally considered predictors of a poor outcome.

Patients with liver insufficiency resulting from hepatic IVC/VC were not only excluded from clinical trials involving cisplatin mono- or combination therapy, but they were also excluded from clinical trials involving newer agents [5, 37]. Academic clinical trials should be organized to address this pressing medical gap.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional Ethical Committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Author Contributions

Mirosława Püsküllüoğlu contributed to the conception and design of the study, while searches within the Hospital registry system was carried out by Mirosława Püsküllüoğlu and Renata Pacholczak-Madej. The tasks of organizing the database and collecting patient data were undertaken by Mirosława Püsküllüoğlu, Agnieszka Pietruszka and Aleksandra Grela-Wojewoda, with Mirosława Püsküllüoğlu taking charge of the statistical analysis. Ethical Committee approval was obtained through the efforts of Mirosława Püsküllüoğlu and Marek Ziobro. The initial draft of the manuscript was authored by Mirosława Püsküllüoğlu and Małgorzata Pieniążek, with specific sections contributed by Agnieszka Rudzińska and Renata Pacholczak-Madej. All authors including Aleksandra Grela-Wojewoda, Agnieszka Pietruszka and Marek Ziobro participated in the revision of the manuscript and gave their approval for the final version to be submitted.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Data Availability

The data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests that could influence this study. Authors declare travel grants or lecture fees: Mirosława Püsküllüoğlu from Gilead, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Roche, Amgen and Janssen; Małgorzata Pieniążek Pfizer from Novartis, Gilead; Agnieszka Rudzińska from Sandoz; Agnieszka Pietruszka from Novartis, MSD, Merck; Renata Pacholczak-Madej from GSK, Accord, BMS; Aleksandra Grela-Wojewoda from Novartis, BMS, Pierre Fabre, Roche, Amgen, MSD, Gilead, Pfizer; Marek Ziobro from Pierre Fabre, Novartis, Ipsen.

Ethical Approval

The Ethical Committee of the Maria Sklodowska-Curie National Research Institute of Oncology Branch Krakow granted ethical approval, as indicated by decision number 1/2023 dated 18 April 2023. In accordance with the Ethical Committee's decision, written informed consent was not mandatory due to the retrospective nature of the study. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional Ethical Committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Feb 10];71:209–49. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33538338. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Miller KD, Kramer JL, Newman LA, Minihan A, et al. Breast Cancer Statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Jan 1];72:524–41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36190501/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Cardoso F, Paluch-Shimon S, Senkus E, Curigliano G, Aapro MS, André F, et al. 5th ESO-ESMO international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 5). Ann Oncol [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2023 Feb 17];31:1623–49. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32979513/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Yang R, Lu G, Lv Z, Jia L, Cui J. Different treatment regimens in breast cancer visceral crisis: a retrospective cohort study. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1048781. 10.3389/fonc.2022.1048781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franzoi MA, Saúde-Conde R, Ferreira SC, Eiger D, Awada A, de Azambuja E. Clinical outcomes of platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with advanced breast cancer: An 11-year single institutional experience. The Breast. 2021 [cited 2024 Jan 1];57:86. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC8044724/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Funasaka C, Naito Y, Kusuhara S, Nakao T, Fukasawa Y, Mamishin K, et al. The efficacy and safety of paclitaxel plus bevacizumab therapy in breast cancer patients with visceral crisis. Breast [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Nov 11];58:50–6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33901922/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Dawood SS, Brzozowski K. Efficacy of CDK4/6i in the visceral crisis setting: Result from a real-world database. 2021;39:1047–1047. 101200/JCO20213915_suppl1047.

- 8.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, Breast Cancer Version 5.2023 [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 27]. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf.

- 9.Parnes HL, Cirrincione C, Aisner J, Berry DA, Allen SL, Abrams J, et al. Phase III study of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and fluorouracil (CAF) plus leucovorin versus CAF for metastatic breast cancer: Cancer and Leukemia Group B 9140. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2003 [cited 2024 Jan 17];21:1819–24. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12721259/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Behrouzi R, Armstrong AC, Howell SJ. CDK4/6 inhibitors versus weekly paclitaxel for treatment of ER+/HER2- advanced breast cancer with impending or established visceral crisis. Breast Cancer Res Treat [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Nov 11];202:83–95. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37584881/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Sbitti Y, Slimani K, Debbagh A, Mokhlis A, Kadiri H, Laraqui A, et al. Visceral crisis means short survival among patients with luminal a metastatic breast cancer: a retrospective cohort study. World J Oncol [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2023 Nov 11];8:105–9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29147444/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Ali R, Aouida M, Sulaiman AA, Madhusudan S, Ramotar D. Can cisplatin therapy be improved? Pathways that can be targeted. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Dec 26];23:7241 Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35806243/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Ghosh S. Cisplatin: the first metal based anticancer drug. Bioorg Chem [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2023 Dec 22];88:102925 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31003078/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Minerva, Bhat A, Verma S, Chander G, Jamwal R, Sharma B, et al. Cisplatin-based combination therapy for cancer. J Cancer Res Ther [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 26];19:530–6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37470570/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Romani AMP. Cisplatin in cancer treatment. Biochem Pharmacol [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Dec 26];206:115323 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36368406/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Gold JM, Raja A. Cisplatin. StatPearls [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 26]; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547695/.

- 17.Benvenuti C, Gaudio M, Jacobs F, Saltalamacchia G, De Sanctis R, Torrisi R, et al. Clinical review on the management of breast cancer visceral crisis. Biomedicines [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Nov 11];11:1083.. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37189701/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Lu Y-S, Mahidin EIBM, Azim H, Eralp Y, Yap Y-S, Im S-A, et al. Abstract GS1-10: Primary results from the randomized Phase II RIGHT Choice trial of premenopausal patients with aggressive HR+/HER2− advanced breast cancer treated with ribociclib + endocrine therapy vs physician’s choice combination chemotherapy. Cancer Res [Internet]. 2023;83:1–10. 10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS22-GS1-10. 10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS22-GS1-10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gennari A, André F, Barrios CH, Cortés J, de Azambuja E, DeMichele A, et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Apr 29];32:1475–95. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34678411/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Sledge GW, Neuberg D, Bernardo P, Ingle JN, Martino S, Rowinsky EK, et al. Phase III trial of doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and the combination of doxorubicin and paclitaxel as front-line chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer: an Intergroup trial (E1193). J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:588–92. 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Shaughnessy J, Miles D, Vukelja S, Moiseyenko V, Ayoub JP, Cervantes G, et al. Superior survival with capecitabine plus docetaxel combination therapy in anthracycline-pretreated patients with advanced breast cancer: Phase III trial results. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2812–23. 10.1200/JCO.2002.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ESMO Metastatic Breast Cancer Living Guideline | ESMO [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 27]. https://www.esmo.org/living-guidelines/esmo-metastatic-breast-cancer-living-guideline/triple-negative-breast-cancer.

- 23.ESMO Metastatic Breast Cancer Living Guideline | ESMO [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 27]. https://www.esmo.org/living-guidelines/esmo-metastatic-breast-cancer-living-guideline/er-positive-her2-negative-breast-cancer.

- 24.Qi L, Luo Q, Zhang Y, Jia F, Zhao Y, Wang F. Advances in toxicological research of the anticancer drug cisplatin. Chem Res Toxicol [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2024 Jan 21];32:1469–86. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31353895/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Isakoff SJ. Triple negative breast cancer: role of specific chemotherapy agents. Cancer J [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2023 Dec 27];16:53. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC2882502/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Forastiere AA, Hakes TB, Wittes JT, Wittes RE. Cisplatin in the treatment of metastatic breast carcinoma: a prospective randomized trial of two dosage schedules. Am J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 1982 [cited 2024 Jan 21];5:243–7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7044098/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Egger SJ, Willson ML, Morgan J, Walker HS, Carrick S, Ghersi D, et al. Platinum‐containing regimens for metastatic breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2024 Jan 22];6:CD003374. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28643430/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Kolarić K, Roth A. Phase II clinical trial of cis-dichlorodiammine platinum (cis-DDP) for antitumorigenic activity in previously untreated patients with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol [Internet]. 1983 [cited 2024 Jan 21];11:108–12. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6685001/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Isakoff SJ, Mayer EL, He L, Traina TA, Carey LA, Krag KJ, et al. TBCRC009: a multicenter phase II clinical trial of platinum monotherapy with biomarker assessment in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2024 Jan 22];33:1902. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25847936/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Modi S, Saura C, Yamashita T, Park YH, Kim S-B, Tamura K, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Dec 11];382:610–21. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31825192/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Rugo HS, Bardia A, Marmé F, Cortés J, Schmid P, Loirat D, et al. Overall survival with sacituzumab govitecan in hormone receptor-positive and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancer (TROPiCS-02): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Jan 25];402:1423–33. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37633306/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Baek DW, Park J-Y, Lee SJ, Chae YS. Impressive effect of cisplatin monotherapy on a patient with heavily pretreated triple-negative breast cancer with poor performance. Yeungnam Univ J Med [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Jan 21];37:230. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7384912/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Joung EK, Yang JH, Oh S, Park SJ, Lee J. Maintenance chemotherapy after 6 cycles of platinum-doublet regimen in anthracycline-and taxane-pretreated metastatic breast cancer. Korean J Intern Med [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Jan 22];36:182–93. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32098457/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Tay F, Buyukkor M, Duran AO. prognostic importance of combined use of MELD scores and SII in hepatic visceral crisis in patients with solid tumours. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Jan 22];33:879–83. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37553926/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Edman Kessler L, Sigfridsson J, Hatzidaki D, Bergh J, Foukakis T, Georgoulias V, et al. Chemotherapy use near the end-of-life in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat [Internet]. 2020;181:645–51. 10.1007/s10549-020-05663-w. 10.1007/s10549-020-05663-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burch PA, Mailliard JA, Hillman DW, Perez EA, Krook JE, Rowland KM, et al. Phase II study of gemcitabine plus cisplatin in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a north central cancer treatment group trial. Am J Clin Oncol Cancer Clin Trials [Internet]. 2005 [cited 2024 Jan 22];28:195–200. https://journals.lww.com/amjclinicaloncology/fulltext/2005/04000/phase_ii_study_of_gemcitabine_plus_cisplatin_in.17.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Püsküllüoğlu M, Rudzińska A, Pacholczak-Madej R. Antibody-drug conjugates in HER-2 negative breast cancers with poor prognosis. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 17];1878:188991. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37758021/. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author upon request.