Abstract

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) may decrease patient quality of life and often leads to acute urinary retention and surgical intervention. While effective treatments are available, many BPH patients do not respond or develop resistance to treatment. To understand molecular determinants of clinical symptom persistence after initiating BPH treatment, we investigated gene expression profiles before and after treatments in the prostate transitional zone of 108 participants in the Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms (MTOPS) Trial. Unsupervised clustering revealed molecular subgroups characterized by expression changes in a large set of genes associated with resistance to finasteride, a 5α-reductase inhibitor. Pathway analyses within this gene cluster found finasteride administration induced changes in fatty acid metabolism, amino acid metabolism, immune response, steroid hormone metabolism, and kinase activity within the transitional zone. We found that patients without this transcriptional response were highly likely to develop clinical progression, which is expected in 13.2% of finasteride-treated patients. Importantly, a patient’s transcriptional response to finasteride was associated with their pre-treatment kinase expression. Further, we identified novel expression signatures of finasteride resistance among the transcriptionally responded patients. These patients showed different gene expression profiles at baseline and increased prostate transitional zone volume compared to the patients who responded to the treatment. Our work suggests molecular mechanisms of clinical resistance to finasteride treatment that could be potentially helpful for personalized BPH treatment as well as new drug development to increase patient drug response.

Keywords: Benign prostatic hyperplasia, RNA-Seq, Finasteride, Alpha blocker, 5α-Reducase inhibitor, Doxazosin

Subject terms: Prostate, Genetics research, Gene expression

Introduction

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) include frequency of urination, urgency, urinary incontinence, and a sense of incomplete emptying, and often leads to the diagnosis of clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia (LUTS/BPH). With advancing age, up to 75% of older men may experience some form of LUTS1,2, and LUTS/BPH treatment imposes high costs on the healthcare system3. If left untreated, LUTS/BPH will continue to progress and patients may develop bladder dysfunction or acute urinary retention requiring surgical intervention.

First-line medical treatment for LUTS/BPH usually includes an α-adrenergic blocker (α-blocker) or a 5α-reductase inhibitor (5ARI). Oral α-blockers are effective when LUTS/BPH is responsive to acetylcholine activity via α1 adrenoceptors to relax the smooth muscle in the prostate or bladder. In contrast, oral 5ARIs reduce prostate size by inhibiting 5α-reductase conversion of testosterone (T) to dihydrotestosterone (DHT), the dominant androgen receptor (AR) agonist. LUTS/BPH treatment approaches are based primarily on results from the Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms (MTOPS), a prospective, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. Initial analysis of MTOPS data found that doxazosin, an α-blocker, and finasteride, a 5ARI, were each effective in a subset of patients, and that the combination (doxazosin + finasteride) decreased LUTS severity and the risk of urinary retention more than either drug alone4–6.

Importantly, many patients experience LUTS that do not respond to either α-blockers or 5ARIs, while other patients experience LUTS progression over time and appear to develop resistance to these treatments6. Further development of LUTS/BPH treatment options will require a deeper understanding of the causes of symptom progression after treatment initiation. However, the underlying causes and pathophysiology of progressive LUTS/BPH are so poorly understood that targeting and refinement of existing treatments is challenging. Furthermore, the diagnosis of LUTS/BPH is, in large part, reliant on the willingness and ability of patients to report LUTS. Similarly, changes in prostate tissue architecture and nodule formation associated with LUTS/BPH progression requires tissue sampling or imaging over time that is not often feasible7. At present, there is incomplete understanding of the impact of the medications on cellular activity in patients, and there is no method to identify those LUTS/BPH patients that would be resistant to medical treatment.

The MTOPS protocol included creating a prostate tissue biorepository within a subset of patients. The biorepository included pre-treatment and post-treatment transitional zone (TZ) biopsy tissue collection and linkage with clinical datasets. The goal of this analysis is to investigate within-person change in TZ gene expression across the four MTOPS study arms (doxazosin, finasteride, combination, placebo). A second goal is to investigate changes in TZ gene expression profiles associated with LUTS/BPH progression after treatment initiation. Results will provide a deeper understanding of the effects of LUTS/BPH treatment on prostate tissue, inform mechanisms for clinical progression, and provide candidate biomarkers to identify LUTS/BPH patients who will respond to medical treatment.

Results

Study participants were 108 patients with average age of 62.7 years, average BMI of 27.4, and approximately 27% were considered to have high blood pressure at baseline (Table 1). As per MTOPS eligibility requirements, AUA symptom scores ranged from 8 to 30. Prostate transition zone volume at baseline ranged from 2.0 to 95.3 ml.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of MTOPS participants by randomization.

| Placebo (N = 37) | Doxazosin (N = 28) | Finasteride (N = 28) | Combination (N = 15) | Overall (N = 108) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical response | |||||

| Responsive | 18 (48.6%) | 12 (42.9%) | 15 (53.6%) | 10 (66.7%) | 55 (50.9%) |

| Resistant | 19 (51.4%) | 16 (57.1%) | 13 (46.4%) | 5 (33.3%) | 53 (49.1%) |

| Race | |||||

| White | 32 (86.5%) | 26 (92.9%) | 24 (85.7%) | 12 (80.0%) | 94 (87.0%) |

| Non-white | 5 (13.5%) | 2 (7.1%) | 4 (14.3%) | 3 (20.0%) | 14 (13.0%) |

| Age at baseline | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 61.7 (7.53) | 64.4 (6.48) | 61.8 (7.11) | 63.5 (5.72) | 62.7 (6.94) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 61.0 [50.0, 86.0] | 64.5 [52.0, 79.0] | 60.0 [51.0, 75.0] | 63.0 [52.0, 75.0] | 62.0 [50.0, 86.0] |

| BMI at baseline | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 27.1 (3.65) | 27.7 (3.54) | 26.8 (4.45) | 28.4 (4.50) | 27.4 (3.95) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 26.9 [21.2, 35.0] | 27.8 [20.4, 36.1] | 26.5 [18.6, 41.8] | 26.5 [23.9, 41.8] | 27.1 [18.6, 41.8] |

| Blood pressure at baseline | |||||

| Low | 29 (78.4%) | 22 (78.6%) | 19 (67.9%) | 9 (60.0%) | 79 (73.1%) |

| High | 8 (21.6%) | 6 (21.4%) | 9 (32.1%) | 6 (40.0%) | 29 (26.9%) |

| Urinary maximum flow rate at baseline | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 9.99 (2.44) | 9.15 (2.46) | 10.1 (2.61) | 11.0 (2.60) | 9.94 (2.55) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 10.0 [5.30, 14.8] | 8.80 [4.50, 14.6] | 10.2 [5.10, 14.6] | 11.7 [6.50, 14.7] | 9.90 [4.50, 14.8] |

| Prostate transition zone (TZ) volume at baseline | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 20.4 (17.8) | 25.5 (23.3) | 15.6 (10.5) | 21.3 (14.0) | 20.6 (17.6) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 15.4 [2.10, 87.3] | 17.2 [4.00, 95.3] | 11.2 [4.70, 40.0] | 17.7 [3.00, 53.0] | 14.6 [2.10, 95.3] |

| AUA symptom score at baseline | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 17.6 (5.80) | 18.5 (6.11) | 17.3 (6.22) | 16.3 (6.37) | 17.6 (6.02) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 18.0 [8.00, 30.0] | 19.0 [8.00, 30.0] | 17.5 [8.00, 28.0] | 14.0 [8.00, 27.0] | 18.0 [8.00, 30.0] |

For continuous variables, means (with SD) and medians (with minimum and maximum) are shown.

SD Standard deviation, Min Minimum, Max Maximum.

Finasteride and combination drug regimens significantly alter gene expression of patients over time.

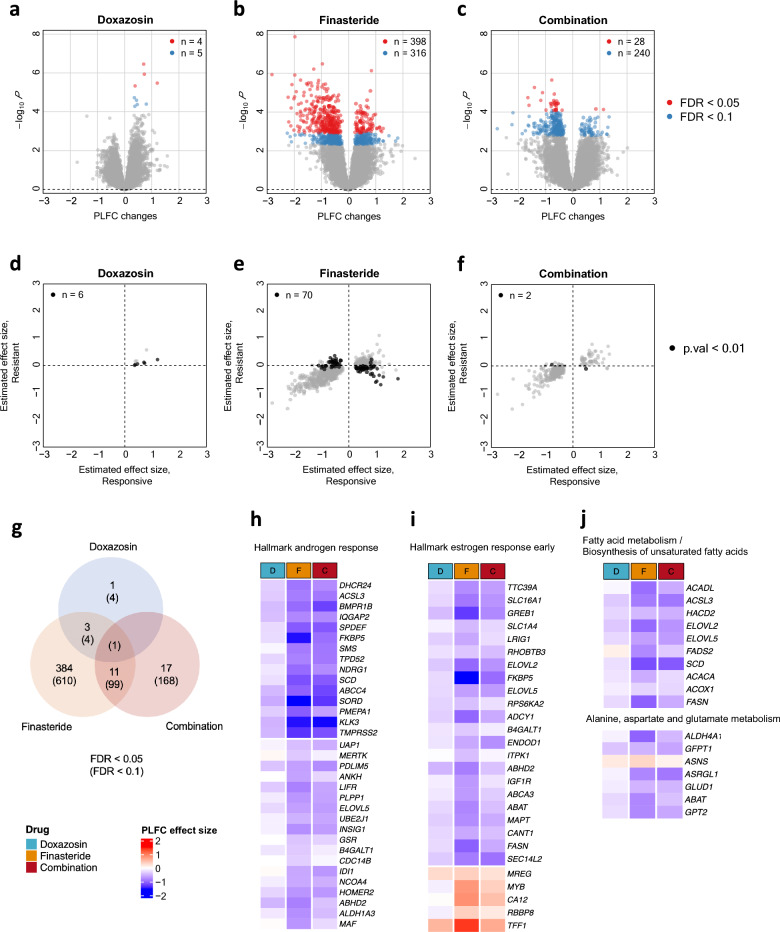

To examine the impact of each treatment on the gene expression profiles, we used the paired structure of the study cohort by constructing a paired log2 fold change (PLFC) for each gene, i.e. log2(follow-up/baseline) within each patient. We first explored changes in gene expression after drug treatments compared to gene expression change within the placebo group. We observed > 400 genes (FDR < 0.05) that had significant differences in the PLFC profiles for the drug-treated groups compared to the placebo-treated group. Specifically, we identified 398 differentially expressed genes for finasteride, 4 genes for doxazosin, and 28 genes for combined therapy (FDR < 0.05, Fig. 1a–c, Extended Data File 1). There were 11 genes that resulted in significant gene expression changes in both finasteride and combined treatments and 3 genes that were significant in both finasteride and doxazosin (Fig. 1g; Supplementary Table 1). Considering the genes that were significant under FDR < 0.1, 14% of the significant genes in the finasteride-treated group were also differentially changed in the combined therapy group, which might suggest a closer affinity of the combination drug to the finasteride than to the doxazosin (Fig. 1g). Many of the genes were down-regulated after drug treatments (70% for the finasteride and 80% for the combined drug).

Figure 1.

Significantly altered genes over time after treatments compared to the placebo. A linear model was fitted for each gene with PLFC values, i.e. log2(FU/BL), as a response variable and other clinical variables as covariates. (a–c) Volcano plots with the estimated effect sizes (drug effect; PLFC differences between each treatment and the placebo) for each gene are displayed for Doxazosin (a), Finasteride (b), and Combination (c). The number of significantly associated genes (FDR < 0.05 in red; FDR < 0.1 in blue) is displayed in each plot. (d–f) The estimated effect sizes are compared between the clinically responsive (x-axis) and resistant (y-axis) groups for Doxazosin (d), Finasteride (e), and Combination (f). Here, only significant genes in (a), (b), and (c) based on FDR < 0.1 were displayed. The number of genes with a raw p-value < 0.01 for the interaction effect of the drug depending on case (clinically resistant) or control (clinically responsive) groups were highlighted by black is displayed in each plot. (g) Summary of the number of significant genes that are overlapping between different treatments. (h–j) Summary of enriched Hallmark pathways and KEGG/Reactome pathways10 for genes significantly altered after the finasteride treatment (FDR < 0.05). The heatmap shows the estimated effect size for each drug at the genes in the significant pathways. FU Follow-up, BL baseline.

We assessed the gene sets significantly altered by each treatment for enrichment in hallmark pathways and KEGG pathways8–10 from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDb)11,12. Among the hallmark gene sets, 6 hallmarks returned as significant at FDR < 0.1 for the significantly altered genes by finasteride. The ‘androgen response’ hallmark was the most significant pathway (FDR = 2.4 × e−16) followed by the estrogen response early’ pathway (FDR = 0.0001) and the genes in these pathways were predominantly down-regulated in the post-treatment samples by finasteride (Fig. 1h,i). We also identified 5 KEGG pathways in which the gene set significantly altered by finasteride was enriched (FDR < 0.1) (Supplementary Table 2) including fatty acid metabolism, alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism, and biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids. We observed that the selected genes from the enriched pathways tended to be down-regulated by the finasteride treatment (Fig. 1j). Additionally, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) once again highlighted that treatment with finasteride had decreased expression of fatty acids genes, steroid hormone biosynthesis genes, and primary immunodeficiency genes, which is consistent with the differential gene expression analysis (Supplementary Table 3).

Next, we examined the interaction effects in the linear model to see if there was any PLFC differences between cases showing clinical progression during the trial (i.e., resistant) and control without defined clinical progression during the trial (i.e., responsive) groups dependent on drug treatment. For each treatment, we only focused on the genes that had significant expression changes compared to the placebo. We did not observe significant differences based on stringent cutoffs (FDR < 0.1), but some genes showed different case/control effects within each treatment compared to the placebo based on a more permissive screening with a raw P value less than 0.01 (Supplementary Fig. 1). By separating the gross drug effects into case and control groups, we investigated differences in gene expression patterns between the two groups (Fig. 1d–f). Most of the genes showed similar patterns of expression changes in both groups whereas the genes with P < 0.01 showed some level of expression changes in the clinically responsive groups but little changes in the clinically resistant group particularly for the finasteride treatment. Although the level of significance was less stringent, the observation that the expression changes were consistent in the clinically responsive group but not in the clinically resistant group coherently suggests that the changes were induced by the finasteride treatment but possibly confounded by some unknown factors. In the following sections, we address these challenges by uncovering the underlying factors which could potentially determine the drug response status for BPH patients.

Patients clinically resistant versus responsive to finasteride show different global patterns of altered gene expression

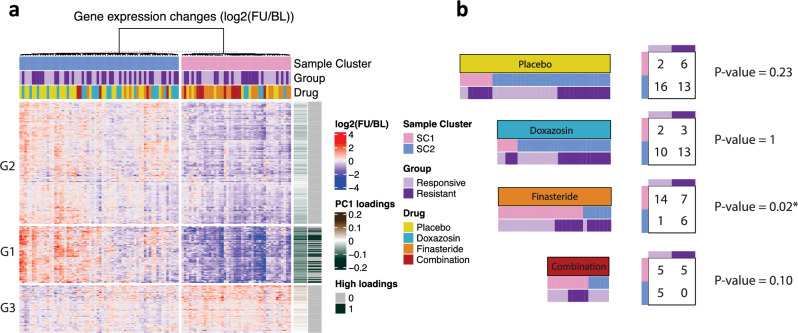

To gain a global overview of altered expression patterns across all patients in the four treatment arms we employed K-means clustering and visualized the results in a 2-dimensional plane (Supplementary Fig. 2). We applied the K-means clustering to the PLFC profiles of the collection of the differentially expressed genes (n = 416) from each drug treatment based on FDR < 0.05. This unsupervised analysis discovered two sample clusters (SC1 and SC2). SC1 mostly consists of patients treated by finasteride or combined therapy whereas SC2 is largely dominated by the patients treated by doxazosin or placebo (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 2). The two clusters are distinctively separated by the first principal component of the PLFC space constructed by 416 genes which explained 53% of the total variation (Supplementary Fig. 2). Perhaps not unexpectedly, these results show that finasteride and combination regimens led to similar expression changes across a large set of genes by similar mechanism. In line with this concept, the patients in SC1 showed evident and concordant expression changes within the cluster while the patients in SC2 showed unvaried and discordant expression, which indicates that the alteration in gene expression was induced by the common mechanism of the finasteride and combined treatments whereas doxazosin or placebo did not involve significant alteration in gene expression.

Figure 2.

Association between gene expression alteration and drug response. (a) Global view of gene expression alteration associated with treatments. Paired log fold change (PLFC), log2(FU/BL), are displayed for significantly altered genes (n = 416) from the linear model in Fig. 1. Two sample clusters (SC1 and SC2) were identified by K-means clustering method and samples (columns) within each cluster are further ordered by hierarchical clustering. The genes (rows) are ordered by hierarchical clustering with three gene clusters (G1, G2, and G3). The row annotation bars indicate the loadings corresponding to the first principal component of the PLFC values (PC1 loadings) and the top 50 genes in the absolute values of the loadings (High loadings). (b) Association between sample clusters (Sample Cluster: SC1 and SC2) and clinical resistance (Group: Responsive and Resistance) within each drug treatment (Drug). For each drug treatment, samples were re-ordered by clusters and drug resistance (left) and counts are shown in the contingency table with the p-values based on Fisher’s exact test (right).

Three gene sets were identified by hierarchical clustering and showed a distinctive gene expression pattern (Fig. 2a). The distinct PLFC profiles of each gene set were mainly driven by the evident expression changes of the SC1 (predominated by finasteride and combination-treated patients) whereas the SC2 (predominated by placebo and doxazosin-treated patients) generally remain unchanged across the gene sets, which is consistent with the results from the differential gene expression analysis. Particularly, the genes in the gene set 1 exhibited a clear separation between the two sample clusters most of which substantially decreased after the drug treatment in the SC1 (Fig. 2a). The analysis of the PC loadings of the differentially expressed genes in the first principal component revealed that the top 50 genes with the highest loadings were all included in the gene set 1, which suggests that the gene set 1 had the largest contribution to the cluster separation, i.e. SC1 vs SC2, (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table 4). Pathway analysis revealed that the genes related to metabolic pathways were over-represented in this gene set.

Having observed that the two sample clusters were distinguished by changes in gene expression over time, we next asked whether such gene expression alteration is associated with clinical response. We categorized the patients within each treatment arm into a contingency table based on the clinical response (i.e., Responsive or Resistant) and their sample cluster (i.e., SC1 or SC2). Among the finasteride-treated patients, the patients in SC1 were significantly enriched in the clinically responsive group compared to the resistant group. Specifically, nearly all patients who were clinically responsive to finasteride showed gene expression changes over time (14 out of 15, 93.3%). In contrast, only one-half of patients clinically resistant to finasteride had gene expression changes (7 out of 13, 53.8%). Differences were significant by the Fisher’s exact test (p-value = 0.02) (Fig. 2b). This finding suggests that the finasteride response could be heavily dependent on overall gene expression changes following drug treatment. In contrast, and somewhat unexpectedly, the combined treatment showed a different pattern such that patients that did not have global gene expression changes (SC2) all showed a clinical response to the treatment (5 out of 5, 100%). The same analysis was performed in patients administered placebo and doxazosin but there was not a significant association between the drug response and the cluster state. The placebo and doxazosin drug regimens showed similar breakdown in which only a small proportion of patients had altered gene expression for both clinically responsive and resistant groups.

Collectively, our unsupervised analyses reveal that patient response to finasteride and combination treatments can be subdivided into SC1 and SC2 gene expression changes. The combined treatment of doxazosin and finasteride also showed gene expression changes that were similar to the finasteride gene set. An important difference between finasteride and combination treatments is that the finasteride-treated patients rarely showed a clinical response to the drug without the alteration in gene expression whereas many of the combination-treated patients responded to therapy without expression changes. This difference may be explained if those patients classified as responsive in the combined therapy arm have reduced LUTS in response to doxazosin rather than in response to the finasteride.

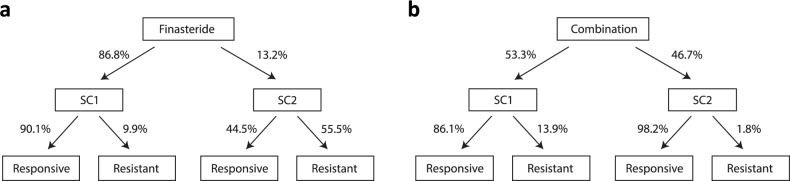

Finasteride clinical resistance decomposition: transcriptional resistance and resistance after transcriptional response

To understand how the clinical response of finasteride and combination treatments is associated with gene expression changes at the population level, we decomposed the mode of drug response into SC1 vs. SC2 gene expression profiles as described in the tree diagrams (Fig. 3a,b). We next asked how many of the patients treated by finasteride would be expected to have gene expression changes and how many of those who had gene expression changes would clinically respond to the drug. We employed Bayes’ theorem to quantify these probabilities at the population level from the current study cohort.

Figure 3.

Predicted clinical response decomposition for finasteride and combination. (a) Applying the Bayes theorem to the obtained contingency table of the finasteride-treated arm (Fig. 2b) with the prior probabilities (P(finasteride-responsive = 0.84) & P(finasteride-resistant) = 0.16), it is expected that 86.8% of the finasteride-treated patients would have significant gene expression changes over time (SC1) whereas the other 13.2% would not show gene expression changes (SC2). While 90.1% of SC1 is expected to be responsive to the drug, only 44.5% is expected to be responsive in SC2. (b) Similarly, we applied the Bayes theorem to the combination-treated group with the prior probabilities (P(combination-responsive = 0.92) & P(combination-resistant) = 0.08), it is expected that 53.3% would have significant gene expression changes over time (SC1) and 86.1% of them are expected to be responsive to the drug. On the other hand, 46.7% of combination-treated patients are expected to be classified in SC2 and 98.2% of them are expected to be responsive whereas only 9.1% are estimated to show drug-resistance with clinical progression.

For the finasteride treatment arm, we previously observed the proportion of patients who had gene expression changes within each of the responsive and resistant groups, i.e. P(SC1|F-responsive) = 0.93 (14 out of 15) and P(SC1|F-resistant) = 0.54 (7 out of 13). Additionally, the analysis of MTOPS data found that about 84% patients clinically responded to the finasteride in the study duration of 5.5 years, i.e., P(F-responsive) = 0.84. By applying the Bayes’ rule, we estimated that 86.8% of finasteride-treated patients would have significant gene expression change (P(SC1) = 0.868) whereas the other 13.2% would show relatively little or no expression changes (P(SC2) = 0.132). We additionally estimated that almost 90.1% patients in SC1 would respond to finasteride while the other 9.9% might develop resistance. In contrast, only 44.5% patients in SC2 are expected to respond the drug while 55.5% would develop LUTS/BPH clinical progression. Thus, there appears to be a clear difference in drug response between the SC1 and SC2 clusters.

The same analysis was applied to participants in the combination treatment arm. We observed the proportions of the combination-treated patients who had gene expression changes within each of the responsive and resistant groups, i.e. P(SC1|C-responsive) = 0.5 and P(SC1|C-resistant) = 1. It is also known by the analysis of MTOPS data that about 92% of patients administered combined therapy responded in the 5.5 year study duration (i.e., P(C-responsive) = 0.92). Given this information, we estimated that 53.3% of combination-treated patients would be classified into SC1, and 86.1% of these SC1-classified patients would be responsive to the drug, which is consistent with the results observed in the finasteride treatment (Fig. 3b). Notably, it was estimated that 98.2% of the patients in SC2 would clinically respond to the combination drug, which is somewhat unexpected compared to the 44.5% estimated with finasteride. As mentioned earlier, patients receiving combination therapy could be responding to doxazosin as well as finasteride, and thus patients responsive to combined therapy may have a separate pathophysiology of LUTS/BPH compared to those patients responsive to finasteride alone.

In summary, about 90% of the SC1-classified patients in the finasteride cohort showed positive clinical response to treatment whereas only 44.5% of the SC2-classified patients responded to treatment. This clearly shows the response to finasteride heavily depends on presence of expression changes. Second, the finasteride and combination treatments have a similar gene expression change profile (SC1) as well as both groups of participants being responsive within the SC1-classified patients. This shows that similar mechanisms might work in both treatments as expected if a combination-treated patient would have responded to the finasteride. In contrast, the results revealed a strong difference within the SC2-classified patients between the two treatments. Only 44.5% would be expected to respond to the finasteride-only treatment whereas 98.2% would be expected to respond to the combination therapy. In line with the earlier results, this further suggests the efficacy of the combined therapy that could work for both groups of patients who would respond to either of doxazosin or/and finasteride.

Altogether, the clinical response decomposition recapitulates the potential mechanisms of how the LUTS/BPH progression is generally expected after treatment initiation for a patient. The results demonstrate that further classification of clinical responses is possible based on the gene expression changes, indicating that there might exist underlying differences between the new subdivided groups beyond the binary responsive/resistant states, which will be further explored in the following sections.

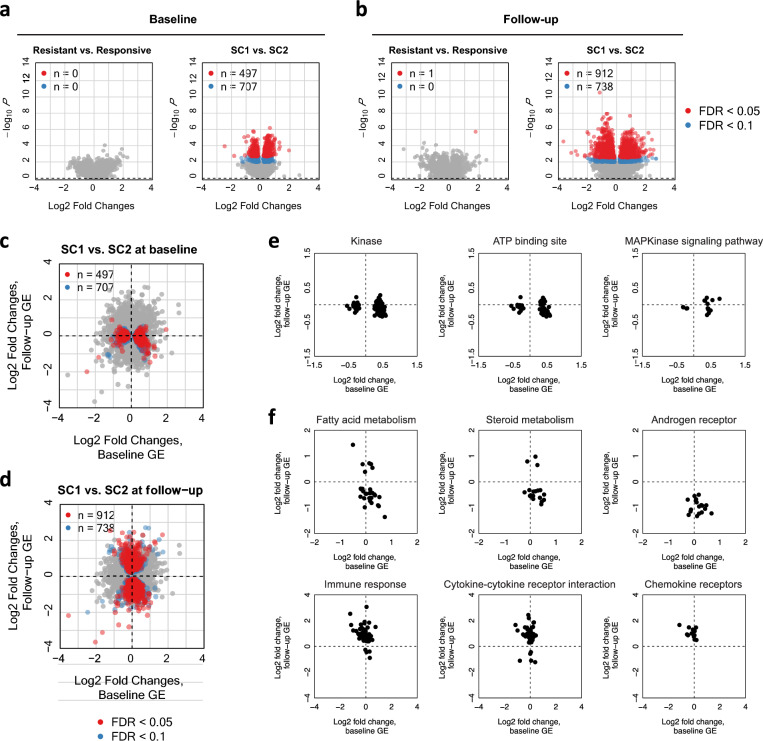

Finasteride transcription-based subgroups (SC1/SC2) have distinct molecular characteristics at baseline as well as follow-up

We next asked if gene expression profiles at baseline or follow-up are associated with LUTS/BPH progression during study follow-up. We first searched for genes differentially expressed between the resistance/responsive groups for each treatment arm separately by applying DESeq2 adjusted for the available baseline covariates (Supplementary Fig. 3; “Methods”). For both time points, only a small number of genes were identified to be differentially expressed between the clinically resistant and responsive patients. At baseline, specifically, we identified three genes (PRKX, PCDH17, SPIB) for doxazosin, three genes (SLC4A4, UPK3BL2, PI15) for finasteride, and four genes (PI16, MLC1, LAMC3, MAG) for the combined therapy (FDR < 0.05, Supplementary Table 5). At follow-up, 17 genes were identified to be differentially expressed between resistant and responsive groups for placebo and additionally six genes and nine genes were identified for finasteride and combination treatments, respectively (FDR < 0.05, Supplementary Table 6).

As we observed heterogeneity in transcriptional signatures between finasteride vs. combination patients (Figs. 2 and 3), we hypothesized that there might be distinct molecular profiles at baseline associated clinical response for each treatment. We assessed this by comparing gene expression at baseline between patients in SC1 and SC2. In this analysis, we merged the patients treated by finasteride and combination as they showed similar patterns in gene expression changes as described earlier. While gene expression at baseline was not obviously different between the clinically resistant vs. responsive groups, larger differences existed between the transcriptional-response-based groups (SC1 vs. SC2) (Fig. 4a). Notably, we identified 497 genes that were differentially expressed at baseline between SC1 and SC2 (FDR < 0.05). Many of these genes showed significant differences only at the baseline and their expression levels have converged to be similar over time after the treatments (Fig. 4c). We found that the identified genes were enriched (FDR < 0.1) in Gene Ontology (GO) categories related to Kinase and ATP binding sites (Fig. 4e, Extended Data File 2). Overall, patients in the SC1 group showed higher baseline gene expression at genes related to Kinase and ATP binding sites. This finding indicates that the patients with lower expression of the genes related to kinase pathways are less likely to develop transcriptional response and therefore are more susceptible to finasteride treatment resistance.

Figure 4.

Baseline/follow-up RNA-seq profiles differentially expressed between SC1 and SC2 within finasteride and combination. (a) Results from differential gene expression analysis using DESeq2 are presented for baseline. Here, we merged the finasteride and combination treatment arms (n = 43). The results comparing between case/control (resistant/responsive) are presented on the left and the results for SC1/SC2 comparison are presented on the right. The genes that are significant are highlighted by red for FDR < 0.05 and blue for 0.05 < FDR < 0.1. (b) The same analysis was performed for the gene expression profiles at follow-up. (c,d) Gene expression differentially expressed between SC1 and SC2 at baseline and follow-up. Log2 fold changes of SC1 with respect to SC2 at the baseline gene expression (GE) vs follow-up GE. Only finasteride and combination treatments were considered. Significant genes at the baseline GE (c) and follow-up GE (d) are highlighted using red (FDR < 0.05) and blue (FDR < 0.1). (e) Log2 fold changes for significantly enriched GO categories or KEGG/Reactome pathways (FDR < 0.1) with genes differentially expressed at baseline (FDR < 0.10). (f) Log2 fold changes for significantly enriched GO categories or KEGG/Reactome pathways10 (FDR < 0.1) with genes differentially expressed at follow-up (FDR < 0.10).

Next, we applied the same analysis to gene expression at the follow-up biopsy. Similar to the baseline expression analysis, there was only one gene (SERTM2, FDR < 0.05) differentially expressed between the clinically drug resistant vs. responsive groups whereas we observed 912 differentially expressed genes between the transcriptional-response-based groups (SC1 vs. SC2) (FDR < 0.05, Fig. 4b,d). We found a global enrichment (FDR < 0.1) for GO categories and KEGG/Reactome pathways related to fatty acid metabolism, steroid hormone activity, androgen receptor (AR) activity, and cytokine-cytokine and chemokine receptors, etc. (Fig. 4f, Extended Data File 3). Overall, SC1 showed lower follow-up expression at genes involved with fatty acid metabolism and steroid and AR activity, but higher follow-up expression at genes related to immune response, cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions, and chemokine receptors.

Clinical and molecular determinants of LUTS/BPH progression within those patients who developed a transcriptional response to assigned treatment

We observed that overall expression changes at the identified genes might be necessary to show a clinical response to finasteride (i.e., the patients who were classified into SC 1). Of these patients, however, there are still a non-ignorable fraction of patients who could develop LUTS/BPH progression. We further investigated if there were any underlying factors that were possibly associated with drug response within the patients that presented the gene expression changes. For the analysis, we only considered the patients classified into SC 1 within the finasteride and combination treatment arms (n = 31; 19 clinically responsive and 12 resistant patients with clinical progression included).

We first explored the available patient-level variables (race, age, BMI, blood pressure, urinary maximum flow rate, prostate transition zone (TZ) volume, and AUA symptom score) collected at baseline to see if they are associated with clinical progression after drug administration. Notably, we found that the prostate TZ volume was significantly associated with clinical response (Fig. 5a). The patients with high TZ volume tended to be resistant to the treatment. We also investigated available clinical variables at baseline and the association with SC1 and SC2 transcriptional responses using univariate (Fisher’s exact test for discrete variables and Wilcoxon test for continuous variables) and multivariate analysis (Logistic regression). No variable showed significant associations.

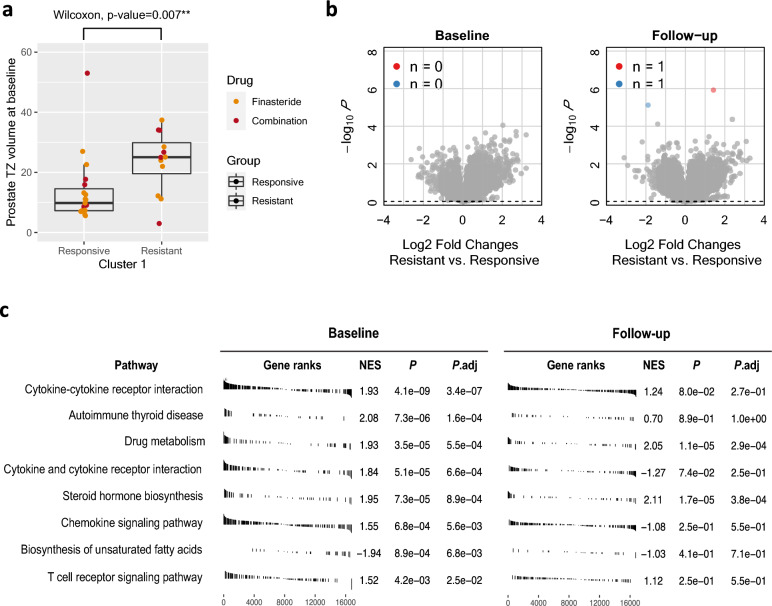

Figure 5.

Underlying factors associated with clinical resistance within SC1 (only finasteride and combination treatments considered). (a) Box plot showing prostate TZ volume values that significantly differed between clinically responsive and resistant groups within the SC1 cluster. (b) Volcano plots describing the log2 fold changes and the p-values from the DESeq2 analysis for comparing gene expression of the resistant and responsive groups for baseline (left) and follow-up (right). (c) Significant KEGG pathways10 from the GSEA analysis with the baseline gene expression (FDR < 0.05) are shown and compared between baseline (left) and follow-up (right). Only two of the significant pathways identified at baseline were also significantly enriched at follow-up (FDR < 0.05). TZ Transition zone.

We then fit a multivariate logistic regression model with clinical response (responsive/resistant) as a binary outcome and all available patient-level variables as predictors. We identified TZ volume and race were associated with clinical progression after adjusting for other variables (p-value < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 4). An increase of 23 mls TZ volume (2 × SD) is associated with an increase of 3.4 times the odds of drug resistance. We also estimated that non-white patients had about 7 times the odds of white patients of showing LUTS/BPH clinical progression during study follow-up.

We next asked if baseline expression might determine clinical response within SC1 participants. To see this, we searched for genes differentially expressed between clinically resistant and clinically responsive groups (Fig. 5b). Although no individual gene was significantly different between the two groups at baseline, GSEA analysis detected enrichment of gene sets in the pathways related to cytokine and cytokine receptor, autoimmune disease, drug metabolism, steroid hormone biosynthesis, chemokine signaling, and fatty acids (FDR < 0.05, Fig. 5c—baseline). The same analysis was applied to follow-up expression (Fig. 5b,c—follow-up). We found only one gene (ATCAY) that was differentially expressed between the groups (FDR < 0.05). The GSEA analysis confirmed that the pathways related to steroid hormone and drug metabolism were also enriched at follow-up whereas the other pathways that were significant at baseline were no longer enriched at follow-up. This finding implicates that clinical progression within the transcriptionally finasteride responded group (SC1) might be correlated with molecular characteristics at baseline.

Individual genes identified as significant between resistant/responsive patients within finasteride and combination treatment

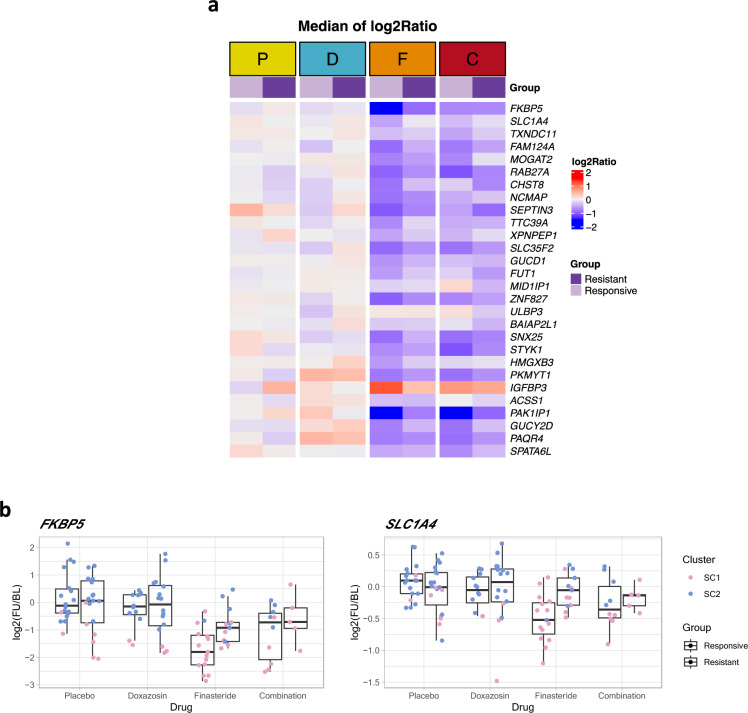

Given our observations of significant changes in SC1 profile gene expression after finasteride and combination treatments, we sought to characterize gene expression patterns of drug response within SC1. Focusing on samples classified into cluster 1 within the finasteride/combination treatments only, we applied a linear model to the PLFC values to explore any differential changes between clinically resistant and responsive groups. We identified 28 genes with significantly different expression changes between resistant and responsive groups (p-value < 0.05, Supplementary Table 7). It should be noted that we chose to include genes with no gene expression changes in the placebo treatment arm but significant differences between the SC1 and SC2 within finasteride/combination treated patients, enabling converged analyses by filtering irrelevant genes. We found that most of the identified genes that showed more pronounced expression changes in the clinically responsive group than the resistant group were in SC1 (Fig. 6a). For example, the top ranked genes FKBP5 and SLC1A4 showed no changes in expression within the placebo and doxazosin treatments whereas FKBP5 and SLC1A4 expression significantly increased with finasteride and combination treatments in the responsive group. (Fig. 6b). Responsive patients showed a decrease in FKBP5 and SLC1A4 relative to placebo, while the patients with clinical progression showed no or relatively small change in these genes.

Figure 6.

Individual genes that had significant differential changes between clinically resistant/responsive patients within the finasteride and combination treatments. (a) Median of expression changes (log2(FU/BL)) for each group is shown for the 28 identified genes (p-value < 0.05). The genes were sorted by their significance level (p-value). (b) Examples of significant expression changes in the top ranked genes: FKBP5 (top) and SLC1A4 (bottom). For each gene, the PLFC distributions for each group are shown using box-plots.

Discussion

This analysis investigated changes in gene expression profiles in the TZ associated with doxazosin and finasteride administration relative to placebo, and explored changes in gene expression profiles associated with resistance to LUTS/BPH treatment. We identified over 400 genes that changed expression (FDR < 0.05) in response to finasteride administration. Furthermore, a gene profile cluster analysis identified two sample clusters (SC1 and SC2) that separated patients responsive to finasteride from patients that were resistance to finasteride with LUTS/BPH progression. Pathway analyses indicated that clinical progression with finasteride involved steroid hormone activity including androgen and estrogen response, and suppression of fatty acid metabolism, amino acid metabolism, and immune system signaling. Exploration of individual genes associated with finasteride resistance included several candidates such as FKBP5 involved in activity of the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. In contrast to finasteride administration, doxazosin had little impact on TZ tissue gene expression.

The logistics of obtaining normal prostate tissue from otherwise healthy men for BPH research presents many challenges. Prior investigations often studied hyperplasia in tissue obtained at prostatectomy from prostate cancer patients or among patients that were nonresponsive to BPH medical therapies13–16. Several biomarkers in clinical or animal models have been associated BPH progression including growth factors such as FGF17 and EGF18, as well as COX-2/prostaglandin activity19,20. Further exploration of urinary proteins found biomarkers of an inflammatory response and cytoskeletal components21. Whether these marker panels reflect processes within the human TZ or are influenced by comorbidities or prior treatments is not always clear. Jin et al. recently analyzed gene expression signatures in prostate tissue from BPH patients scheduled for surgical intervention, identifying foundational pathways in DNA repair, cholesterol synthesis, cell cycle regulation, and immune system regulation22. Prior 5ARI exposure was linked to differences predominantly in androgen-regulated pathways. Despite some similarities in pathways identified, substantial methodological differences exist between this work and that of Jin et al.22. While MTOPS participants were treatment naïve at baseline and treatments were randomly assigned, Jin et al.’s cross-sectional design only involved 30 BPH patients clinically progressing and needing surgery through prior treatments which were determined by the practicing physician. Additionally, Jin et al. used low-grade cancer patient tissue as a control while this MTOPS used each participant has his own control.

There are few opportunities outside of MTOPS to target analyses to the human TZ and explore response to LUTS/BPH treatment. Prior analysis of immune cell infiltration into the TZ using FFPE tissue at MTOPS baseline was correlated with LUTS progression23. Additionally, analysis of FFPE TZ biopsy tissue at MTOPS Year 5 follow-up found tissue fibrosis related to resistance to combination therapy, although not to doxazosin or finasteride administered as single agents24.

Our approach was to explore changes in gene expression from baseline to follow-up using fresh-frozen TZ tissue from MTOPS patients in each treatment arm. We identified 416 genes that changed expression (FDR < 0.05) in the TZ in response finasteride relative to placebo. Overall, the effect of finasteride administration was a reduction in gene expression across pathways involved in androgen response, estrogen response, fatty acid metabolism, fatty acid synthesis, and amino acid metabolism. In contrast, only 5 genes were identified in the doxazosin study arm as distinct from placebo (FDR < 0.05), and only 1 gene change was unique to doxazosin administration. While TZ cellular composition includes a substantial smooth muscle component25, adrenergic pathway innervation to the TZ appears insufficient to induce a measurable change in gene transcription associated with an α-adrenergic blocker such as doxazosin.

We observed that gene expression changes emerged as important determinants in predicting the drug response of the finasteride and combination drugs. While many of the patients were classified as SC1, only a subset of the SC1 patients responded to therapy. Specifically, 66.7% (14/21) of the finasteride-treated SC1 patients and 50% (5/10) of the combination-treated SC1 patients responded to therapy. This separation of patients within the SC1 classification suggests that a simple binary state of responsive/resistant classification may not be adequately sensitive to capture the full range of possible responses to treatment.

Contrasting SC1 against SC2 identified a gene expression profile for clinical resistance to finasteride administration. Approximately 13% of finasteride patients expressed the SC2 profile, and 44.5% of patients with this SC2 profile developed clinical resistance to finasteride. These gene clusters were independent of clinical biomarkers of LUTS/BPH such as prostate size or PSA level. Pathway analyses identified changes in mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), fatty acid metabolism, steroid metabolism, and cytokine/immune response (FDR < 0.10). Phosphorylation via MAPK, as with other kinase pathways, is an intracellular signaling mechanism to regulate transcription, protein synthesis, and cell proliferation. MAPK also interacts with the PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathways, perhaps in a compensatory manner, to affect cell survival and apoptosis26,27. Altered MAPK activity remains a strong candidate in regulating cell proliferation or altering steroid synthesis necessary for clinical resistance to finasteride.

Exploration of individual genes predicting finasteride resistance identified several new candidates. These included SLC1A7 involved in glutamine transport and regulated by AR and PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathways. Unfortunately, we are unaware of a prior analysis investigating ATCAY in LUTS/BPH and thus our ability to infer a potential mechanism is limited. An interesting and novel result was that the most significant identified gene expression change associated with finasteride resistance was in FKBP5 (FK506 binding protein 5; 6p21.31). FKBP5 encodes the protein FKBP51, a phospholipase with broad roles in modulating the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis in response to environmental stressors and elevated cortisol levels. FKBP5 or FKBP51 have been linked to the progression of multiple cancers as well as clinical outcomes related to depression, suicide, cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance, blood lipid levels, and obesity/diabetes28–31. Data from The Cancer Genome Atlas found high FKBP5 expression in the prostate32. FKBP51 stimulates AR dimerization in LNCaP cells while having little impact in AR-independent cell lines32,33. In response to finasteride and loss of DHT, FKBP5 and AR dimerization may increase to enhance AR function and lead to finasteride resistance. FKBP5 may also impact estrogen metabolism34 and NF-κB signaling via the Akt signaling pathway, consistent with our pathway analyses. FKBP51 is the target of FDA approved immunosuppressive drugs such as HSP90 inhibitors, cyclosporine and tacrolimus35, and future BPH treatment options may consider an adaptation of these approaches to increase finasteride response in patients resistant to therapy.

We also explored baseline differences in gene expression profiles SC1 vs. SC2 that might predict future resistance to finasteride. We found 470 genes that differed between SC1 and SC2 at baseline, and pathway analyses indicated genes related to kinase pathways and ATP binding sites. Exploration of individual genes at baseline identified several candidates, including SLC4A4 and MLC1 that have recently linked to prostate cancer progression36,37. Thus, it may be feasible to develop a marker panel that could serve as a susceptibility panel for finasteride treatment resistance. Indeed, over 800 genes were differentially expressed at follow-up between SC1 and SC2. Overall, SC1 showed lower follow-up expression at the genes related to fatty acid, steroid, and AR whereas follow-up expression was higher for the genes related to immune response, cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions, and chemokine receptors. Such a broad-based change at follow-up may indicate that resistance is mediated at least in part by a foundational signaling mechanism such as MAPK. These candidates require further investigation to confirm any connection with LUTS/BPH treatment resistance.

Although approximately one-third of patients in the combination therapy study arm also had the SC2 gene expression profile, this profile did not generalize to patients receiving combination therapy. It is important to remember that the definition of a response to combination therapy includes those patients that responded to doxazosin as well as finasteride, and thus the definition of a treatment response in the combination group is substantially different from a treatment responsive in the finasteride-only group. Prostate enlargement is often claimed as the underlying cause of LUTS leading to a BPH diagnosis, but indeed there are multiple causes of LUTS including bladder dysfunction and neuropathy that likely factor into who responds to BPH treatment.

Several clinical and demographic factors were also associated with response to treatment. For example, finasteride resistance was associated with increased TZ volume, but not with clinical measures of symptom severity such as AUA symptom index. The high correlation between drug resistance and TZ volume remains unclear, but potential explanations include the possibility of a shared pathway that increases both resistance and TZ volume, issues with patient compliance, or variations in drug penetration. The reason that non-white race was also associated with treatment resistance is unclear. The number of non-white patients in this analysis was small and we were unable to identify a race-specific gene expression signature. Alternatively, racial differences may be a consequence of study patient selection protocols or other characteristics that are correlated with race, and a full-scale analysis of a racially diverse study population is needed.

Strengths of this analysis include use of MTOPS as a resource for fresh-frozen tissue and rigorously collected clinical data. Patient eligibility criteria targets LUTS/BPH patients with moderate symptoms and thus reflects a clinical population likely benefit from medical LUTS/BPH treatments. The TZ of the prostate is the target prostate zone most strongly associated with LUTS/BPH. Whereas clinical BPH studies that focus attention on LUTS severity as an outcome must infer a connection to the prostate usually through prostate volume measurement. MTOPS protocols collected a wide range of clinical and patient-level data such that we could characterize and control for alternative explanations. Our analysis of changes in gene expression will help to target of underlying pathobiology and identify those likely susceptible to treatment.

A major limitation of this analysis was the lack of sample size across treatment and treatment response groups necessary to support all subanalyses. Replication is feasible however in a future MTOPS analysis. Treatment options have expanded since the MTOPS trial, and we were unable consider additional α-blockers, 5ARIs, or phosphodiasteride inhibitors. While the bulk RNA-seq approach in the current study provides a snapshot of the overall transcriptional state, it could mask the heterogeneity within cell populations, potentially obscuring dynamic changes occurring at the single-cell level. This can be improved by cell-type deconvolution approach or single-cell RNA-seq, which will be addressed in our future study.

In conclusion, we identified a gene expression profile in prostate TZ tissue associated with response to finasteride administration. Finasteride administration affected multiple metabolic, inflammatory, and steroid hormone pathways. Further studies are needed to confirm these initial novel results.

Methods

MTOPS

Details of the MTOPS protocol are published4,6. Briefly, MTOPS was a prospective, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. This NIDDK sponsored clinical trial randomized 3047 men at least 50 years of age to one of four treatment arms: α-blocker (doxazosin, up to 8 mg per day), 5ARI (finasteride, 5 mg per day), the combination, or placebo. Recruitment occurred through 17 clinical centers, and all men provided written informed consent. Eligible men had moderate to severe LUTS assessed as a score between 8 and 30 (on a scale of 0–35) on the AUA symptom scores38 and relatively low urinary flow rate (Uroflow) between 4 and 15 ml per second with a voided volume of at least 125 ml. Men were excluded who had prior surgery for BPH, supine blood pressure less than 90/70 mmHg, or a serum PSA over 10 ng/ml.

During follow-up, LUTS severity was assessed with the AUA every three months. Similarly, urinary functioning was assessed by Uroflow meter every 3 months, and a digital rectal examination was performed, with a serum PSA measurement, annually. A transrectal ultrasound was performed at baseline and at five years follow-up or end of study to measure prostate volume. The trial endpoint was “overall clinical progression”, defined as: a four-point rise in the AUA over baseline, acute urinary retention, recurrent urinary tract infection, renal insufficiency, or urinary incontinence. This trial endpoint also served as our analysis outcome. Participants recorded as displaying overall clinical progression while receiving the assigned BPH therapy were labeled as clinically resistant to therapy, while those participants without overall clinical progression during study follow-up were labeled as clinically responsive to therapy.

The overall rate of clinical progression in the placebo group of MTOPS was 4.5 per 100 person-years. This was reduced to 2.7 and 2.9 per 100 person-years in the doxazosin and finasteride arms, respectively (each p < 0.01), while the combination reduced the risk to 1.5 per 100 person-years, less than placebo or either monotherapy treatment arm (p < 0.001). The risks of acute urinary retention or surgical intervention were reduced by finasteride alone or combined therapy, but not doxazosin alone, over placebo.

Biomarker SubStudy

Within the larger MTOPS protocol there was a biopsy tissue sub-study, where 1198 participants across all study arms provided written-consent to have baseline and follow-up prostate tissue biopsy cores stored in the NIDDK biorepository for future translational studies. Sample collection included two cores each taken from right and left transitional zone (TZ), and one taken from the left and right peripheral zone (PZ). One set of the TZ biopsies was flash-frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen. The rest of the biopsy cores were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE). We obtained NIDDK approval to access and extract RNA from fresh-frozen prostate tissue samples collected at baseline and after treatment in a nested case–control study within MTOPS.

Study design

We defined a case as a patient that resisted treatment and had clinical progression. We defined a control as a patient responsive to treatment and without clinical progression during the trial. We randomly selected 1 responsive control for each resistant case within each treatment arm from within the tissue sub-study. Tissue at baseline and follow-up were from the same side of the TZ. We also selected responsive controls such that the distributions for age (± 3 years) and baseline AUA-SI score (± 3 pts) were similar to that of identified resistant cases. We considered individually matching controls to cases, rather than simply matching distributions across groups but determined that any added precision might be small as our focus is on within-individual change in gene expression and MTOPS imposed eligibility constraints on age, clinical characteristics, data collection protocols, and duration of follow-up across all participants. Indeed, individual matching would limit opportunities to investigate matched factors in future ancillary studies or could induce a null bias39 if we individually matched on a panel of strong predictors of BPH progression. Demographic and clinical data at baseline including age, race, BMI, blood pressure (high/low), urinary maximum flow rate, TZ volume, and AUA symptom score were extracted from the MTOPS database. The final study population consisted of 108 MTOPS participants with adequate specimens available in the archive for both baseline and follow-up specimens and with successful RNA extraction and sequencing for both specimens across doxazosin (n = 28), finasteride (n = 28), combination (n = 15), and placebo (n = 37).

Tissue preparation and RNA sequencing

RNA was extracted from frozen TZ biopsies at baseline and follow-up. Prior to extraction, excess OCT from each biopsy sample was physically removed on an aluminum block surrounded by dry ice to ensure the tissue does not thaw. Frozen tissue was sectioned to 20 µM slices QIAzol ensuring that the sample is submerged in the liquid and stored at -80C. RNA extraction used the miRNAeasy kit from QIAgen (Item # 69989) following manufacturer instructions. RNA samples were sequenced at Novagene in a blinded manner by Illumina HiSeq 2500 and subjected to quality control using FastQC. RNA reads were aligned to the hg19 genome assembly using TopHat followed by quantification of gene-level raw reads counts using the HTseq. In the present study, we only considered protein-coding genes from the ENSEMBL database available on the biomaRt R package, which reduced the gene set to 19,217 genes.

Differential gene expression analysis for baseline RNA-seq and follow-up RNA-seq

To find differences at baseline TZ gene expression between responsive and resistant patient groups, we performed differential gene expression analysis for baseline expression using the DESeq2 R package40. Briefly, raw gene counts were normalized to adjust for sequencing depths and a negative binomial model was fitted to the normalized count data for individual genes with control for baseline effects including race, age in years, BMI, blood pressure (high/low), urinary maximum flow rate, prostate transition zone volume, and AUA symptom score. As a result, DESeq2 generated log2 fold change estimates using an empirical Bayes method by shrinking dispersion estimates based on information across all genes.

We performed separate analyses for each study arm: finasteride, doxazosin, combined therapy, and placebo. The resulting log2 fold changes were used to assess differences in gene expression between BPH cases and controls. Genes were considered differentially expressed if they had FDR < 0.05.

Normalization for paired gene expression change analysis

To accurately measure differences in gene expression between baseline and follow-up, it is critical to have gene expression profiles that are comparable across time points. We employed the trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) method which is a between-sample normalization method which uses a weighted trimmed mean of the log expression ratios between samples41,42. By adjusting the distribution of majority of genes to be similar across the paired RNA-seq within an individual, this approach enables accurate estimation of gene expression differences between the paired data in the present study.

Additionally, genes were filtered out from the downstream analysis if they had relatively low raw read counts to avoid possible inflation of expression changes in low-expressed genes. Specifically, genes with < 5 median reads counts were excluded (n = 2436). Consequently, the final RNA-seq data included n = 16,781 protein-coding genes and 108 individuals.

To incorporate the paired structure (baseline and follow-up) of the RNA-seq data into differential expression analysis, we considered paired log2 fold changes (PLFC) of the TMM-normalized follow-up gene expression with respect to the baseline normalized expression for every sample, i.e. log2(follow-up/baseline). The PLFC expression profiles characterize the expression changes of follow-up RNA-seq with respect to the paired baseline RNA-seq within individuals, which allows us to quickly compare expression changes at gene-level between the drug treatments as well as case/control groups. The PLFC = 0 corresponds to equal expression for the pair and PLFC > 0 (< 0) corresponds to increased expression (decreased expression) of follow-up compared to the baseline.

Differential gene expression analysis for paired RNA-seq

To evaluate the effect of finasteride, doxazosin, and combined treatment (finasteride + doxazosin) on gene expression, we fit a linear model to individual genes (n = 16,781) with the PLFC as a response variable and the four drug arms (including placebo) and drug responsive/resistant groups as main explanatory variables. A set of covariates recorded at baseline were adjusted in the model including race, age in years, BMI, blood pressure (high/low), urinary maximum flow rate, prostate transition zone volume, and AUA symptom score. The treatment arms were one-hot encoded with placebo as a reference category and drug resistance were also one-hot encoded with the BPH non-progression group as a reference. In the linear model, we included the interaction terms between drug therapies and BPH progression/non-progression to explore the treatment-specific response compared to the placebo group. Genes were determined to be differentially changed over time between groups if they had FDR < 0.05.

GO and KEGG/Reactome pathway enrichment

We performed GO and KEGG/Reactome pathway enrichment with the Bioconductor packages biomaRt and clusterProfiler. The number of genes used as background set is 16,781 protein-coding genes which were the final set of genes consistently used in our analysis.

Ethics statement

We utilize pre-existing biopsy samples form the Medical Treatment of Prostate Symptoms (MTOPS) clinical trial. These samples have no patient identifiers, and there is no means to trace data back to participants. As such they fall outside of the definition of human research per §46.102 (f) (2) as applied by the National Institutes of Health. All protocols used in this research manuscript were approved by IRB committees at Vanderbilt University and the University of Tennessee Health Science Center. We confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

H.Y.C. performed data analysis, prepared figures/tables, and wrote the main manuscript text. J.H.F. designed and conceived the study and wrote the main manuscript text. W.Y.C. performed data analysis. H.Y.C., K.C.T., M.S.L., K.M., W.Y.C., P.E.C., and J.H.F. proofread, made comments, and approved the manuscript.

Data availability

The raw bulk RNA-seq data and the processed data generated in this study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession code GSE262946.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-69301-x.

References

- 1.Coyne, K. S. et al. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in the USA, the UK and Sweden: Results from the Epidemiology of LUTS (EpiLUTS) study. BJU Int.104(3), 352–360 (2009). 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08427.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kupelian, V. et al. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms and effect on quality of life in a racially and ethnically diverse random sample: The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Arch. Intern. Med.166(21), 2381–2387 (2006). 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Litwin, M. S., Saigal, C. S. Urologic diseases in America. In Chapter 14: Economic Impact of Urologic Diseases 464–496 (2012).

- 4.Bautista, O. M. et al. Study design of the Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms (MTOPS) trial. Control Clin. Trials24(2), 224–243 (2003). 10.1016/S0197-2456(02)00263-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan, S. A. et al. Long-term treatment with finasteride results in a clinically significant reduction in total prostate volume compared to placebo over the full range of baseline prostate sizes in men enrolled in the MTOPS trial. J. Urol.180(3), 1030–1032 (2008). 10.1016/j.juro.2008.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McConnell, J. D. et al. The long-term effect of doxazosin, finasteride, and combination therapy on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N. Engl. J. Med.349(25), 2387–2398 (2003). 10.1056/NEJMoa030656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berry, S. J. et al. The development of human benign prostatic hyperplasia with age. J. Urolol.132(3), 474–479 (1984). 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)49698-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci.28(11), 1947–1951 (2019). 10.1002/pro.3715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanehisa, M. et al. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res.51(D1), D587-d592 (2023). 10.1093/nar/gkac963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res.28(1), 27–30 (2000). 10.1093/nar/28.1.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liberzon, A. et al. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics27(12), 1739–1740 (2011). 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.102(43), 15545–15550 (2005). 10.1073/pnas.0506580102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu, D. et al. Integrative multiplatform molecular profiling of benign prostatic hyperplasia identifies distinct subtypes. Nat. Commun.11(1), 1987 (2020). 10.1038/s41467-020-15913-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin, R. et al. Glucocorticoids are induced while dihydrotestosterone levels are suppressed in 5-alpha reductase inhibitor treated human benign prostate hyperplasia patients. Prostate82(14), 1378–1388 (2022). 10.1002/pros.24410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Middleton, L. W., et al. Genomic analysis of benign prostatic hyperplasia implicates cellular re-landscaping in disease pathogenesis. JCI Insight.5(12) (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Liu, D. et al. Upregulated bone morphogenetic protein 5 enhances proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition process in benign prostatic hyperplasia via BMP/Smad signaling pathway. Prostate81(16), 1435–1449 (2021). 10.1002/pros.24241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lucia, M. S. & Lambert, J. R. Growth factors in benign prostatic hyperplasia: Basic science implications. Curr. Urol. Rep.9(4), 272–278 (2008). 10.1007/s11934-008-0048-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frantzi, M. et al. Urinary proteomic biomarkers in oncology: Ready for implementation?. Expert Rev. Proteom.16(1), 49–63 (2019). 10.1080/14789450.2018.1547193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu, S. et al. The prostaglandin synthases, COX-2 and L-PGDS, mediate prostate hyperplasia induced by low-dose bisphenol A. Sci. Rep.10(1), 13108 (2020). 10.1038/s41598-020-69809-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin, R. et al. The prostaglandin pathway is activated in patients who fail medical therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia with lower urinary tract symptoms. Prostate81(13), 944–955 (2021). 10.1002/pros.24190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greer, T. et al. Custom 4-Plex DiLeu isobaric labels enable relative quantification of urinary proteins in men with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). PLoS One10(8), e0135415 (2015). 10.1371/journal.pone.0135415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin, R. et al. Transcriptomic analysis of benign prostatic hyperplasia identifies critical pathways in prostatic overgrowth and 5-alpha reductase inhibitor resistance. Prostate84(5), 441–459 (2024). 10.1002/pros.24661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torkko, K. C. et al. Prostate biopsy markers of inflammation are associated with risk of clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia: Findings from the MTOPS study. J. Urol.194(2), 454–461 (2015). 10.1016/j.juro.2015.03.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macoska, J. A. et al. Prostate transition zone fibrosis is associated with clinical progression in the MTOPS study. J. Urol.202(6), 1240–1247 (2019). 10.1097/JU.0000000000000385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Babinski, M. A. et al. Significant decrease of extracellular matrix in prostatic urethra of patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Histol. Histopathol.29(1), 57–63 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee, E.-R. et al. Interplay between PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling pathways in DNA-damaging drug-induced apoptosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Mol. Cell. Res.1763(9), 958–968 (2006). 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corrales, E. et al. PI3K/AKT signaling allows for MAPK/ERK pathway independency mediating dedifferentiation-driven treatment resistance in melanoma. Cell Commun. Signal.20(1), 187 (2022). 10.1186/s12964-022-00989-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tufano, M. et al. FKBP51 plays an essential role in Akt ubiquitination that requires Hsp90 and PHLPP. Cell Death Dis.14(2), 116 (2023). 10.1038/s41419-023-05629-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soto, O. B. et al. Structure and function of the TPR-domain immunophilins FKBP51 and FKBP52 in normal physiology and disease. J. Cell. Biochem. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.González-Castro, T. B. et al. Gene-environment interaction between HPA-axis genes and trauma exposure in the suicide behavior: A systematic review. J. Psychiatr. Res.164, 162–170 (2023). 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fries, G. R., Gassen, N. C. & Rein, T. The FKBP51 glucocorticoid receptor co-chaperone: Regulation, function, and implications in health and disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci.18(12), 2614 (2017). 10.3390/ijms18122614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maeda, K. et al. FKBP51 and FKBP52 regulate androgen receptor dimerization and proliferation in prostate cancer cells. Mol. Oncol.16(4), 940–956 (2022). 10.1002/1878-0261.13030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Periyasamy, S. et al. FKBP51 and Cyp40 are positive regulators of androgen-dependent prostate cancer cell growth and the targets of FK506 and cyclosporin A. Oncogene29(11), 1691–1701 (2010). 10.1038/onc.2009.458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Habara, M. et al. FKBP52 and FKBP51 differentially regulate the stability of estrogen receptor in breast cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.119(15), e2110256119 (2022). 10.1073/pnas.2110256119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fedotcheva, T. A., Fedotcheva, N. I. & Shimanovsky, N. L. Progesterone as an anti-inflammatory drug and immunomodulator: New aspects in hormonal regulation of the inflammation. Biomolecules12(9), 1299 (2022). 10.3390/biom12091299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu, Z. et al. SLC4A4 promotes prostate cancer progression in vivo and in vitro via AKT-mediated signalling pathway. Cancer Cell Int.22(1), 127 (2022). 10.1186/s12935-022-02546-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao, X. et al. Database mining of genes of prognostic value for the prostate adenocarcinoma microenvironment using the cancer gene atlas. Biomed. Res. Int.2020, 5019793 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barry, M. J. et al. Overlap of different urological symptom complexes in a racially and ethnically diverse, community-based population of men and women. BJU Int.101(1), 45–51 (2008). 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07191.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rothman, K., Greenland, S., Lash, T. Modern Epidemiology, 3rd ed. (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008).

- 40.Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol.15(12), 550 (2014). 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robinson, M. D. & Oshlack, A. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol.11(3), R25 (2010). 10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-r25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: A bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics26(1), 139–140 (2009). 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw bulk RNA-seq data and the processed data generated in this study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession code GSE262946.