Abstract

BACKGROUND

Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy and camrelizumab plus apatinib (TRIPLET protocol) is promising for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (Ad-HCC). However, the usefulness of microwave ablation (MWA) after TRIPLET is still controversial.

AIM

To compare the efficacy and safety of TRIPLET alone (T-A) vs TRIPLET-MWA (T-M) for Ad-HCC.

METHODS

From January 2018 to March 2022, 217 Ad-HCC patients were retrospectively enrolled. Among them, 122 were included in the T-A group, and 95 were included in the T-M group. A propensity score matching (PSM) was applied to balance bias. Overall survival (OS) was compared using the Kaplan-Meier curve with the log-rank test. The overall objective response rate (ORR) and major complications were also assessed.

RESULTS

After PSM, 82 patients were included both the T-A group and the T-M group. The ORR (85.4%) in the T-M group was significantly higher than that (65.9%) in the T-A group (P < 0.001). The cumulative 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS rates were 98.7%, 93.4%, and 82.0% in the T-M group and 85.1%, 63.1%, and 55.0% in the T-A group (hazard ratio = 0.22; 95% confidence interval: 0.10-0.49; P < 0.001). The incidence of major complications was 4.9% (6/122) in the T-A group and 5.3% (5/95) in the T-M group, which were not significantly different (P = 1.000).

CONCLUSION

T-M can provide better survival outcomes and comparable safety for Ad-HCC than T-A.

Keywords: Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Molecular targeting agent, Programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors, Microwave ablation

Core Tip: Microwave ablation (MWA) and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) are important locoregional therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). HAIC with anti-angiogenesis agents and programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitiors [camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy (TRIPLET)] followed by MWA contribute to better outcome than TRIPLET alone. Combination of locoregional therapy improve prognosis of advanced HCC.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for the majority of primary liver cancers and is the fifth most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-associated mortality according to 2020 cancer statistics from the World Health Organization[1,2]. Unfortunately, > 70% of HCC patients are already in the advanced stage when they are diagnosed initially, with a dismal overall survival (OS)[3,4]. Although the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend systematic chemotherapy, radiotherapy and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) as first-line treatments in advanced HCC (Ad-HCC) patients with good hepatic function reserve, poor objective response rates (ORRs) and high postoperative recurrence rates remain major challenges[5,6].

Recently, several new therapeutic methods have gradually entered the physicians’ field of vision. For example, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) can effectively reduce the intrahepatic tumor burden via direct delivery of chemotherapeutic agents into the tumor-feeding arteries. HAIC using the FOLFOX regimen (oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil and leucovorin) has been suggested to improve ORR and OS[7,8]. Lyu et al[9] reported the efficacy and safety of HAIC, which achieved a greater survival benefit than sorafenib. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab was applied in Ad-HCC, with ORR 27.3% by RECIST 1.1 and 33.2% by mRECIST, and it has been recommended as a first-line treatment in Ad-HCC in the 2022 updated Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) guidelines[10]. Chemotherapeutic agents have been shown to exert synergistic anticancer effects with TKIs[11]. Moreover, chemotherapeutic agents can also improve the effect of immune checkpoint inhibitors by promoting the release of tumor-associated antigens and enhancing the function of antigen-presenting cells[12]. Therefore, our team designed a combination protocol by HAIC and camrelizumab plus apatinib (TRIPLET protocol) for treatment in patients with Ad-HCC, and the preliminary results of this TRIPLET treatment have been reported in ASCO 2020.

Previously, some scholars have reported that TKIs could decrease blood flow and increase the extent of thermal ablation (TA)-induced coagulation necrosis in HCC[13]. In addition, combination therapy with TA and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitors has been shown to reduce postablation recurrence and improve the survival of patients with Ad-HCC[14,15]. However, few studies have focused on the subsequent therapy of TRIPLET protocol. Microwave ablation (MWA), as an effective local therapy, was comprehensively applied in HCC, and maybe a potential way to eliminating the residual lesion after TRIPLET protocol in Ad-HCC. To verify our hypothesis and find a new treatment strategy for Ad-HCC, we compared the safety and efficacy between TRIPLET alone (T-A) and TRIPLET plus MWA (T-M) in this retrospective study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

The TRIPLET as an II stage clinical trail has been registered (NCT4191889). This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou, China (B2023-411-01) and conformed to the principles of the 1975 Helsinki Declaration. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, the requirement for written informed consent was waived. The study has been registered at Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (https://www.chictr.org.cn/, ChiCTR2300075828).

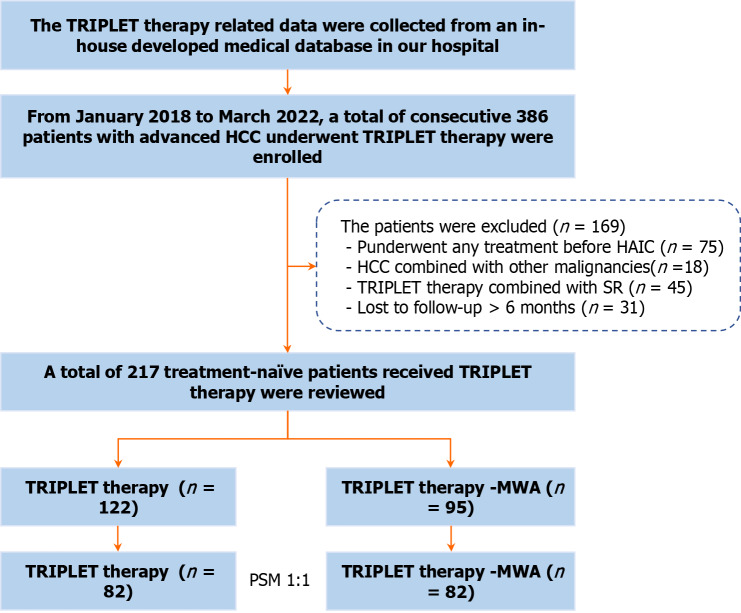

Between January 2018 and March 2022, a total of 386 consecutive patients with HCC who underwent initial TRIPLET combination therapy were reviewed using our in-house medical database. All HCC patients were diagnosed based on the European Association for the Study of Liver and the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease guidelines. Suspicious cases were confirmed by imaging-guided needle biopsy. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Aged 18-75 years; (2) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status < 2; (3) Child-Pugh class A or B liver function; and (4) Advanced HCC confirmed to meet BCLC C stage. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Previous treatment before TRIPLET therapy; (2) The presence of other malignancies confirmed by positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) or dynamic contrast-enhanced CT/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); (3) TRIPLET therapy combined with sequential liver resection surgery; and (4) Lost to follow-up > 6 months. Finally, a total of 217 patients (25 females and 192 males; mean age, 53.2 ± 11.1 years) with Ad-HCC were enrolled in this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The illustrated flowchart of selecting patient for comparing between camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy alone and camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy combined with microwave ablation treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; MWA: Microwave ablation; TRIPLET: Camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy; SR: Liver resection surgery; HAIC: Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy; PSM: Propensity score matching.

TRIPLET protocol

Patients received the TRIPLET combination therapy until unacceptable toxic effects occurred or there was loss of clinical benefit. Patients could continue treatment beyond disease progression if the investigator observed evidence of clinical benefit and if symptoms and signs indicating unequivocal disease progression were absent. Dose interruption and sequential reduction were permitted for medication-related adverse events (AEs). Patients who transiently or permanently discontinued either of the 3 treatments because of an AE were allowed to continue taking the other two or a single agent therapy as long as the investigator determined that there was clinical benefit. HAIC of the FOLFOX7 regimen and the combined protocols of TKI and PD-1 inhibitor therapy are shown in Supplementary material. The criteria for TRIPLET combination therapy discontinuation are described in Supplementary material and Figure 1.

Follow-up protocol

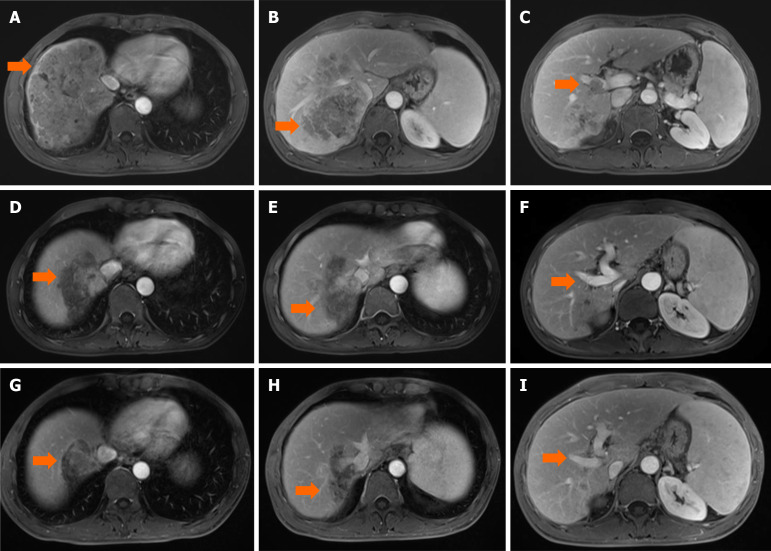

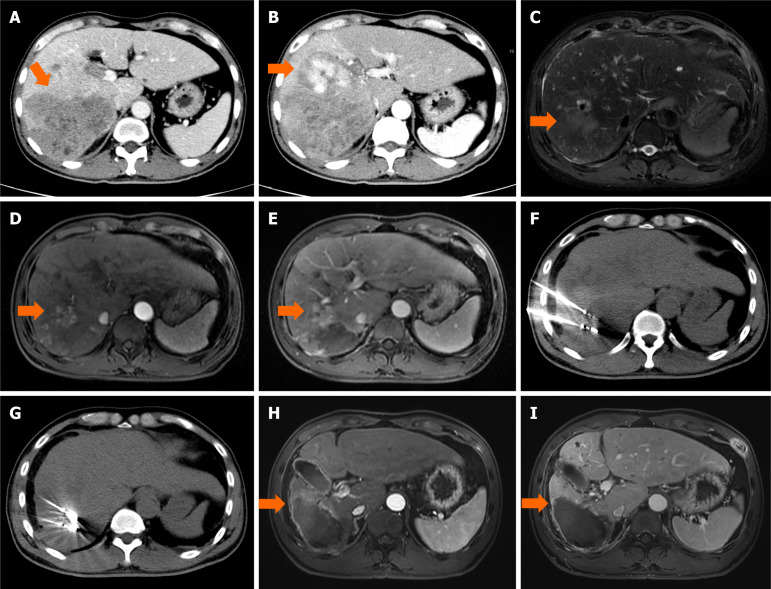

The patients were censored at the last follow-up (May 31, 2023). Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging (CT and MRI) were assessed every 3 months in the first postprocedural year and every 6 months thereafter. If suspicious metastasis was detected, chest, whole-body bone scan, or PET-CT was then performed accordingly. Dynamic contrast-enhanced CT or MRI was performed every 4-6 weeks after initial TRIPLET therapy and evaluated independently by two radiologists with 10 years of experience who were blinded to the procedures. Based on contrast-enhanced imaging findings, the response was categorized into complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD) as per the mRECIST[16]. CR is disappearance of any intratumoural arterial enhancement in all target lesions; PR is at least a 30% decrease in the sum of diameters of the lesions with arterial enhancement, compared with the baseline sum of the diameters of the target lesions; PD is an increase of at least 20% in the sum of the diameters of the lesions with arterial enhancement, compared with the baseline sum of the diameters of the target lesions; SD is any cases that do not qualify for either PR or PD. The medical records of the two patients with Ad-HCC who received TRIPLET therapy alone and T-M therapy are shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

An example of follow-up medical record of camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with tumor thrombus of right inferior portal vein. A 48-year-old male patient with hepatocellular carcinoma (arrow) were examined [the maximum diameter, 13.1 cm; location in S4/8; alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), > 121000 ng/mL] by contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging scanning on July 2021. A-C: Preoperative scan [T1WI portal phase]; D-F: After two-cycle camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy (TRIPLET), the tumor (arrow) has shrunk (the maximum diameter, 7.7 cm; AFP, 10616.0 ng/mL) (T1WI portal phase); G-I: After four-cycle TRIPLET, the tumor (arrow) has shrunk significantly (the maximum diameter, 7.0 cm; AFP, 6183.00 ng/mL) (T1WI portal phase).

Figure 3.

An example of follow-up medical record of camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy combined with microwave ablation treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. A 54-year-old male patient with hepatocellular carcinoma (arrow) were examined [the maximum diameter, 8.7 cm; alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), 1765 ng/mL] by contrast enhanced computed tomography scanning on September 2020. A and B: The tumor was diffusely distributed (arrow) and the right main branch of portal vein showed filling defect (arterial phase and portal phase); C-E: After four-cycle camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy, the tumor (arrow) has shrunk significantly, but the tumor periphery remained active (arrow) and showed enhanced activity [T2-weighted imaging (T2WI), T1WI arterial phase and portal phase]; F and G: The residual lesions were ablated by two microwave antennas at the same time. The ablation power was 60 W and the ablation time was 10 minutes; H and I: Six months after microwave ablation, magnetic resonance imaging (T1WI arterial phase and portal phase) showed that the tumor activity had completely disappeared (arrow) and the tumor markers had returned to normal.

MWA therapy selection

In this study, patients were treated with MWA by a multidisciplinary expert group when the following three conditions were met: (1) CR of primary tumors occurred after TRIPLET combination therapy, but PD was found simultaneously in other intrahepatic regions; (2) PR occurred after TRIPLET combination therapy. Therefore, MWA was performed with the intention of curing visible tumors on enhanced imaging; and (3) When the tumor was controlled by TRIPLET combination therapy, the purpose of MWA was to further reduce the tumor burden. The reason for MWA execution was explained to the patient and their families, and consent was obtained. The CT-guided MWA protocol is shown in Supplementary material.

Endpoints and definitions

Clinical data selection is shown in Supplementary material. Complete ablation was defined as the absence of any enhancing lesion (indicating residual tumor) at the ablation site on contrast material–enhanced CT or MRI performed 1 month after MWA, which was decided by the consensus of two diagnostic radiologists with 10 years of experience in abdominal imaging. The primary endpoints were ORR, including hepatic ORR of the first cycle of TRIPLET therapy, the optimal hepatic ORR after multiple cycles of TRIPLET therapy and the overall ORR. ORR was defined as the percentage of patients with CR and PR lasting for over 4 weeks from the first radiological confirmation. The secondary endpoints were survival outcomes, including OS, progression-free survival (PFS), intrahepatic PFS (IPFS) and extrahepatic PFS (EPFS). OS was calculated from the date of initial TRIPLET therapy to the date of death from any cause or final follow-up. PFS was calculated from the date of initial TRIPLET therapy to the date of PD or final follow-up. The third endpoint was safety, which was assessed using physical examination findings, laboratory tests, complications and AEs according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 5.0[17].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp., NY, United States) and the RMS package of R software version 3.5.1 (http://www.r-project.org/). The quantitative variables are presented as the mean ± SD or median with interquartile range (IQR) and were compared by the Kruskal-Wallis test. The qualitative variables presented as frequencies were compared using the χ2 test. Propensity score matching (PSM) was applied using a nearest-neighbor algorithm (1:1) to adjust the potential unbalanced variables in both groups. The propensity scores obtained from PSM were further used for case-weight estimation [inverse probability treatment weighting (IPTW)]. Weights for the T-A group were the inverse of the propensity score, and those for the T-M group were the inverse of one minus the propensity score. The cumulative survival was compared using the Kaplan-Meier method with the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariable analyses of independent prognostic factors were evaluated by means of the forward stepwise Cox regression model. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was interpreted to carry statistical significance.

RESULTS

Patients enrolled

In this study, 122 in the T-A group and 95 in the T-M group were reviewed. The baseline characteristics stratified by therapeutic modality before and after PSM are shown in Table 1. Except for ascites and albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grade (P = 0.011 and 0.041), the distributions of other variables between the T-A group and T-M group are comparable. After PSM 1:1, all variables showed no significant difference (all, P > 0.05) (Supplementary Figures 1 and 2). Of the 217 eligible patients, 32 (14.7%) patients with tumors who received blood supply from extrahepatic arteries simultaneously were found. Among them, 157 (72.4%) underwent unilateral hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy, whereas 34 (15.7%) underwent proper hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy. The MWA parameters after TRIPLET for Ad-HCC are outlined in Table 2. The median interval time between TRIPLET and MWA was 40 days (range, 32-83 days). The complete ablation rates of intrahepatic tumors and overall all tumors were 60% (57/95) and 35.8% (34/95), respectively. The median sessions of Ad-HCC patients who underwent MWA in the liver, lung and adrenal gland were 2, 1, and 1, respectively. Among all patients with complete ablation, only one experienced recurrence after 2.5 months.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients with Ad-hepatocellular carcinoma who received camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy therapy

| Variables |

Unmatched

|

PSM (1:1)

|

||||

|

TRIPLET alone group (n = 122)

|

TRIPLET-MWA group (n = 95)

|

P value

|

TRIPLET alone group (n = 82)

|

TRIPLET-MWA group (n = 82)

|

P value

|

|

| Age, year | 0.930 | 1.000 | ||||

| ≤ 65 | 112 (91.80) | 86 (90.53) | 76 (92.68) | 77 (93.90) | ||

| > 65 | 10 (8.20) | 9 (9.47) | 6 (7.32) | 5 (6.10) | 1.000 | |

| Gender | 0.505 | |||||

| Female | 12 (9.84) | 13 (13.68) | 8 (9.76) | 9 (10.98) | 1.000 | |

| Male | 110 (90.16) | 82 (86.32) | 74 (90.24) | 73 (89.02) | ||

| ECOG | 0.900 | 1.000 | ||||

| 0 | 122 (100.00) | 94 (98.95) | 82 (100.00) | 81 (98.78) | ||

| 1 | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.05) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.22) | ||

| Comorbidity | 1.000 | 0.677 | ||||

| Absence | 110 (90.16) | 86 (90.53) | 75 (91.46) | 74 (90.24) | ||

| Presence | 12 (9.84) | 9 (9.47) | 7 (8.54) | 8 (9.76) | ||

| HBV | 0.407 | 1.000 | ||||

| Absence | 6 (4.92) | 2 (2.11) | 4 (4.88) | 2 (2.44) | ||

| Presence | 116 (94.26) | 93 (95.79) | 78 (95.12) | 80 (97.56) | ||

| Ascites | 0.011a | 1.000 | ||||

| Absence | 93 (76.23) | 87 (91.58) | 75 (91.46) | 75 (91.46) | ||

| Presence | 29 (22.95) | 8 (8.42) | 7 (8.54) | 7 (8.54) | ||

| ALBI grade | 0.041a | 0.867 | ||||

| 1 | 67 (54.92) | 66 (69.47) | 55 (67.07) | 57 (69.51) | ||

| 2-3 | 55 (45.08) | 29 (30.53) | 27 (32.93) | 25 (30.49) | ||

| HCC number | 0.277 | 0.219 | ||||

| 1-3 | 54 (44.26) | 50 (52.63) | 50 (70.42) | 42 (59.15) | ||

| > 3 | 68 (55.74) | 45 (47.37) | 21 (29.58) | 29 (40.85) | ||

| HCC diameter, cm | 0.667 | 0.155 | ||||

| < 5 | 7 (5.74) | 6 (6.32) | 7 (8.54) | 4 (4.88) | ||

| 5-10 | 51 (41.80) | 34 (35.79) | 41 (50.00) | 32 (39.02) | ||

| > 10 | 64 (52.46) | 55 (57.89) | 34 (41.46) | 46 (56.10) | ||

| AFP, ng/mL | 0.605 | 0.428 | ||||

| ≤ 400 | 46 (37.70) | 40 (42.11) | 31 (37.80) | 37 (45.12) | ||

| > 400 | 76 (62.30) | 55 (57.89) | 51 (62.20) | 45 (54.88) | ||

| Vascular invasion | 0.077 | 0.346 | ||||

| Absence | 18 (14.75) | 24 (25.26) | 15 (18.29) | 21 (25.61) | ||

| Presence | 104 (85.25) | 71 (74.74) | 67 (81.71) | 61 (74.39) | ||

| Metastasis | 0.750 | 0.158 | ||||

| Absence | 68 (55.74) | 50 (52.63) | 50 (60.98) | 40 (48.78) | ||

| Presence | 54 (44.26) | 45 (47.37) | 32 (39.02) | 42 (51.22) | ||

| AST (U/L), median, IQR | 67 (31, 105) | 77 (32, 112) | 0.854 | 85 (28, 128) | 77 (35, 127) | 0.872 |

| ALT (U/L), median, IQR | 54 (22, 89) | 59 (22, 89) | 0.746 | 58 (22, 89) | 59 (25, 109) | 0.929 |

| TBIL (μmol/L), mean ± SD | 17.8 | 23.2 | 0.422 | 18.6 | 19.0 | 0.710 |

| ALB (g/L), mean ± SD | 37.0 ± 5.1 | 37.6 ± 4.2 | 0.564 | 37.2 ± 53 | 37.0 ± 4.2 | 0.567 |

| INR, mean ± SD | 1.1 ± 0.12 | 1.12 ± 0.10 | 0.901 | 1.10 ± 0.14 | 1.11 ± 0.10 | 0.892 |

| PT (s), mean ± SD | 12.4 ± 0.3 | 12.3 ± 0.6 | 0.940 | 12.4 ± 0.8 | 12.4 ± 0.6 | 1.000 |

| PLT (× 109), median, IQR | 208(59, 245) | 256 (67, 312) | 0.358 | 230 (55, 270) | 256 (78, 304) | 0.660 |

P value < 0.05 suggest statistically significant differences.

Data are number of patients; data in parentheses are percentage unless otherwise indicated. Data in bracket was percent of patients. The quantitative data with mean ± SD or median with interquartile range were compared by the Kruskal-Wallis test. The qualitative data in two groups were compared by using the χ2 test. HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; TRIPLET: Camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy; MWA: Microwave ablation; PSM: Propensity score match; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; AFP: α-fetoprotein; ALB: Albumin; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; PT: Prothrombin time; INR: International normalized ratio; TBIL: Total bilirubin; PLT: Platelet; IQR: Interquartile range.

Table 2.

Microwave ablation parameters after camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma

|

Parameters

|

MWA (n = 95)

|

| Ablation of residual tumor activity | 63 (66.3) |

| Ablation of recurrent tumor | 32 (33.7) |

| Maximum tumor diameter (cm) | |

| ≤ 5 | 58 (61.1) |

| > 5 | 37 (38.2) |

| No. of tumor | |

| Single | 74 (77.9) |

| Multiple | 21 (22.1) |

| Extrahepatic metastasis before MWA | 65 (68.4) |

| Ablation of tumor type number | |

| 1 | 73 (76.8) |

| 2 | 19 (20) |

| > 2 | 3 (3.2) |

| Ablation of liver tumor | 92 (96.8) |

| Ablation of lung tumor | 13 (13.7) |

| Ablation of adrenal gland tumor | 3 (3.2) |

| Ablation of breast tumor | 1 (1.1) |

| Hepatic tumors | |

| Ablative duration (minute) | 26 |

| Ablative power (W) | 55.8 ± 6 |

| Ablative sessions | 2 |

| Ablative points | 4 |

| Lung tumors | |

| Ablative duration (minute) | 14 |

| Ablative power (W) | 50.2 ± 3.4 |

| Ablative sessions | 1 |

| Ablative points | 2 |

| Adrenal gland tumors | |

| Ablative duration (minute) | 20 |

| Ablative power (W) | 45.6 ± 4.2 |

| Ablative sessions | 1 |

| Ablative points | 1 |

| Breast tumors | |

| Ablative duration (minute) | 16 |

| Ablative power (W) | 50 |

| Ablative sessions | 1 |

| Ablative points | 2 |

| The response to HAIC | |

| CR | 8 (8.4) |

| PR | 78 (82.1) |

| SD | 9 (9.5) |

| Complete ablation of hepatic tumors | 57 (60) |

| Complete ablation of all tumors | 34 (35.8) |

| Recurrence after MWA | 57 (60) |

| Combination of radiotherapy | 8 (8.4) |

Data are number of patients; data in parentheses are percentage unless otherwise indicated. Data in bracket was percent of patients. HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; MWA: Microwave ablation; HAIC: Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy; CR: Complete response; PR: Partial response; SD: Stable disease.

Antitumor activity comparison

Antitumor activity comparisons between the T-A group and T-M group are shown in Table 3. The median HAIC sessions were four (IQR, 2-6) in the two groups. For hepatic tumors, the first ORRs in the T-A group were comparable with those in the T-M group (P = 0.062). However, the optimal ORR in the T-A group was significantly higher than that in the T-M group (P < 0.001). Moreover, for overall tumors, the overall ORR in the T-A group was also significantly higher than that in the T-M group (P = 0.001). After PSM 1:1, these results remained consistent with the previous results.

Table 3.

Theraputic effectiveness comparison between camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy group and camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy-microwave ablation group

|

Variables

|

TRIPLET group (n = 122)

|

TRIPLET-MWA group (n = 95)

|

P value

|

TRIPLET group (n = 82)

|

TRIPLET-MWA group (n = 82)

|

P value

|

| Hepatic response | ||||||

| Tumor response to the first TRIPLET | 0.062 | 0.120 | ||||

| Non-OR | 90 (73.77) | 54 (60.67) | 58 (70.73) | 45 (57.69) | ||

| OR | 32 (26.23) | 35 (39.33) | 24 (29.27) | 33 (42.31) | ||

| The optimal tumor response | < 0.001 | 0.007 | ||||

| Non-OR | 38 (31.15) | 9 (9.47) | 21 (25.61) | 7 (8.54) | ||

| OR | 84 (68.85) | 86 (90.53) | 61 (74.39) | 75 (91.46) | 0.006 | |

| Overall response | 0.001 | |||||

| Non-OR | 46 (37.70) | 15 (15.79) | 28 (34.15) | 12 (14.63) | ||

| OR | 76 (62.30) | 80 (84.21) | 54 (65.85) | 70 (85.37) | ||

| HAIC sessions1 | 4 (2, 6) | 4 (2, 6) | 1.000 | 4 (2, 6) | 4 (2, 6) | 1.000 |

| Interval between TRIPLET and MWA, day1 | 40 (32, 53) | 36 (32, 48) |

The qualitative data using median with interquartile range in two groups were compared by using the χ2 test.

Data are number of patients; data in parentheses are percentage unless otherwise indicated and data in bracket was percent of patients. TRIPLET: Camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; HAIC: Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy; MWA: Microwave ablation; PSM: Propensity score match; OR: Objective response.

Uni- and multivariate analyses

The univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses for OS and PFS are summarized in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. The univariate analysis showed that comorbidity, ascites, ALBI grade, number of tumors, metastasis and treatment allocation were associated with OS, whereas ascites, number of tumors, metastasis and treatment allocation were associated with PFS. Multivariate analysis showed that comorbidity [hazard ratio (HR) = 2.060; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.369-3.098; P = 0.001], number of tumors (HR = 2.78; 95%CI: 1.51-5.14; P = 0.001) and treatment allocation (HR = 0.16; 95%CI: 0.08-0.33; P < 0.001) were significant prognostic factors for OS and that number of tumors (HR = 1.60; 95%CI: 1.13-2.27; P = 0.008), metastasis (HR = 1.86; 95%CI: 1.32-2.62; P < 0.001) and treatment allocation (HR = 0.52; 95%CI: 0.37-0.74; P < 0.001) were significant prognostic factors for PFS. To further explore the risk factors affecting the OS and PFS of patients who underwent T-M, the univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses are shown in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4. Incomplete ablation was found to be an independent risk factor for PFS.

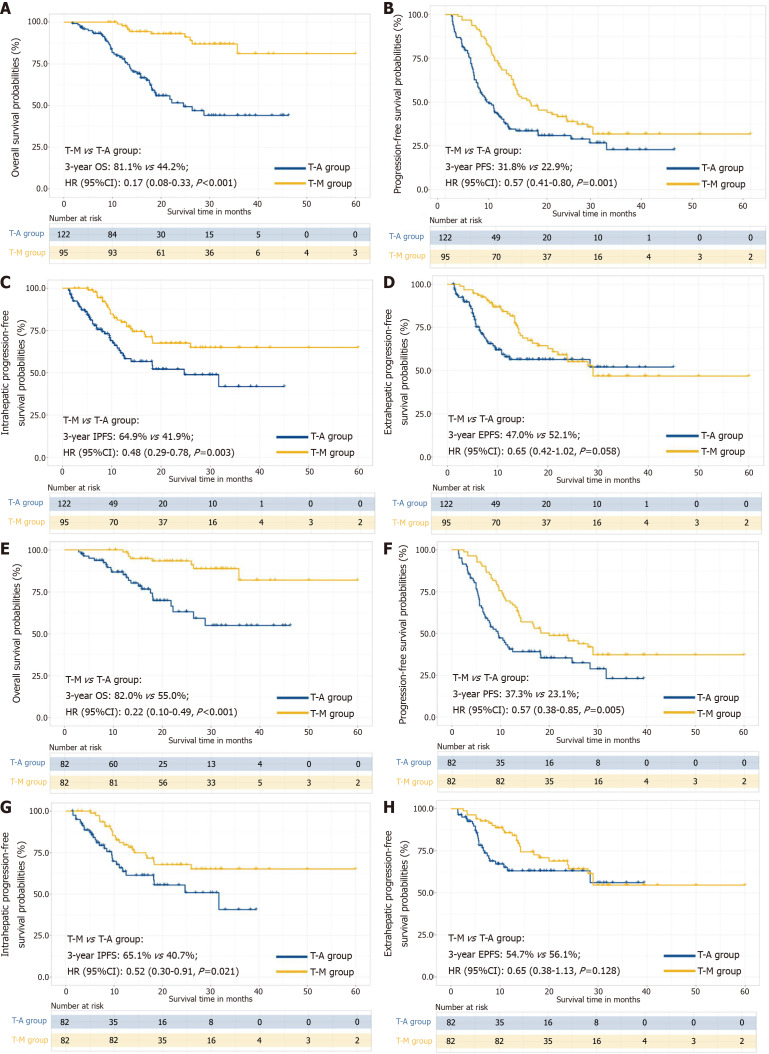

Survival outcomes comparison

The median follow-up duration for the T-A group and T-M group was 22.4 months (IQR, 12.7-51.3 months) and 24.8 months (IQR, 13.4-48.8 months), respectively. The sample size of this study is small, and the statistical power of the multivariate analysis might have been inadequate. Therefore, we used different analytical methods to evaluate OS and PFS (Supplementary Table 5). In the crude Kaplan-Meier analyses, significant differences were observed regarding OS (median, 24.6 months in T-A vs NA months T-M; P < 0.001; Figure 4A), PFS (median, 8.5 months in T-A vs 16.8 months T-M; P = 0.001; Figure 4B), IPFS (median, 24.7 months in T-A vs NA months T-M; P = 0.003; Figure 4C) and EPFS (median, NA months in T-A vs 29.0 months T-M; P = 0.058; Figure 4D) between the two groups before PSM. Similarly, the PSM-adjusted Kaplan-Meier analyses also showed that significant differences were observed regarding OS (median, NA months in T-A vs NA months T-M; P < 0.001; Figure 4E), PFS (median, 9.5 months in T-A vs 20.0 months T-M; P = 0.005; Figure 4F), IPFS (median, 31.7 months in T-A vs NA months T-M; P = 0.021; Figure 4G) and EPFS (median, NA months in T-A vs NA months T-M; P = 0.128; Figure 4H). The cumulative 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS rates were 98.7%, 93.4%, and 82.0% in the T-M group and 85.1%, 63.1%, and 55.0% in the T-A group (HR = 0.22; 95%CI: 0.10-0.49; P < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Comparing the survival of camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy alone and camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy combined with microwave ablation treatment for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. A-D: Kaplan-Meier curves for the overall survival (OS) (A), progression-free survival (PFS) (B), intrahepatic PFS (IPFS) (C) and extrahepatic PFS (EPFS) (D) of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma before propensity score matching (PSM); E-H: Kaplan-Meier curves for the OS (E), PFS (F), IPFS (G) and RPFS (H) of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma after PSM. T-M: Camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy combined with MWA; T-A: Camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy alone; OS: Overall survival; PFS: Progression-free survival; IPFS: Intrahepatic progression-free survival; EPFS: Extrahepatic progression-free survival; HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

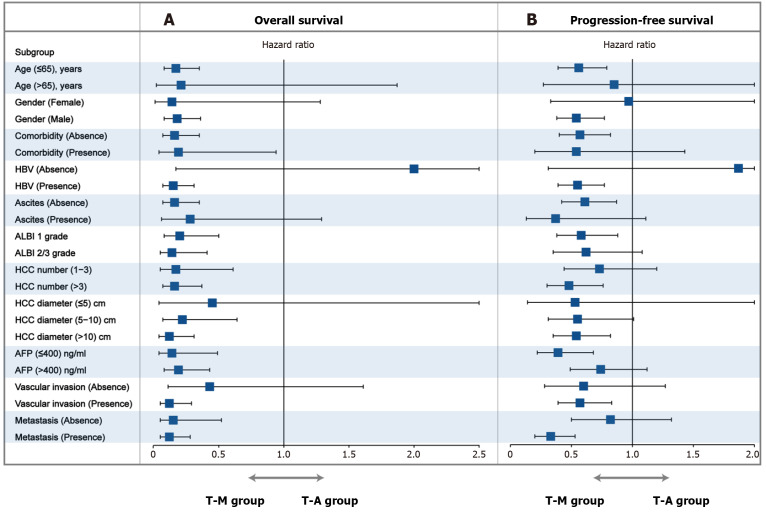

Subgroup analysis

The subgroup analyses of OS, and PFS based on clinical variables using forest plots are shown in Figure 5. Neither the subgroup nor sensitivity analyses changed our essential finding that TRIPLET combined with MWA provided a survival benefit outperforming TRIPLET in most clinical variables. These results suggested that the T-M appeared to particularly benefit patients at an older age (≤ 65 years), male, absence of comorbidity, absence of hepatitis B virus (HBV), absence of ascites, tumor diameter (> 5 cm), and vascular invasion based on OS. Furthermore, the T-M benefited patients at an older age (≤ 65 years), male sex, tumor diameter (> 10 cm), number of tumors (> 3), vascular invasion, AFP (≤ 400 ng/mL) and metastasis based on PFS. These results provide interventional treatment strategy for patients with different clinical factors.

Figure 5.

Forest plot showing the factors associated with overall survival and progression-free survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma who received camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy alone and camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy combined with microwave ablation. A: Overall survival in all patients; B: Progression-free survival in all patients. T-M: Camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy combined with MWA; T-A: Camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy alone; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; AFP: α-fetoprotein; ALBI: Ascites and albumin-bilirubin.

Safety

The TRIPLET-related AEs and complications between the two groups are shown in Supplementary Table 6 and Table 4. Liver dysfunction was the most common minor complication, including the presence of mild ascites and increased transaminase levels. Six major complications transpired in the T-A group, including one patient with peritoneal effusion, one with biliary fistula, three with liver abscess, and one with massive ascites. However, there were 5 major complications that occurred in the T-M group, including two patients with peritoneal effusion, one with liver abscess, and one with hepatic biloma. There was no significant difference in the major complications between the two groups (P = 1.000).

Table 4.

Complications comparison related to camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy or camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy-microwave ablation

|

Complications

|

TRIPLET alone group (n = 122)

|

TRIPLET-MWA group (n = 95)

|

P value

|

| Major complications | 6 (4.9) | 5 (5.3) | 1.000 |

| Peritoneal effusion | 1 (0.8) | - | |

| Liver abscess | 3 (2.5) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Biliary fistula | 1 (0.8) | - | |

| Biloma | - | 2 (2.0) | |

| Hydropneumothorax requiring drainage | - | - | |

| Massive ascites | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Seeding | - | 1 (1.1) | |

| Minor complications | 36 (29.5) | 22 (23.2) | 0.755 |

| Liver dysfunction | 18 (14.8) | 12 (12.6) | |

| Fever | 18 (14.8) | 10 (10.5) | |

| Abdominal nonspecific pain | 3 (2.4) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Bile duct dilatation | 1 (0.8) | 2 (2.0) | |

| Hemorrhage | 5 (4.0) | 3 (3.2) | |

| Mild pleural effusion | 10 (8.1) | - | |

| Mild ascites | 6 (4.8) | 3 (3.2) | |

| Jaundice | 4 (3.2) | 3 (3.2) | |

| Other | 7 (5.7) | 4 (4.0) |

Unless otherwise indicated, data are number of patients. Data in parentheses are percentages and were calculated by using the total number of patients in each group as the denominator. TRIPLET: Camrelizumab plus apatinib and hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy; MWA: Microwave ablation.

Summary

T-M can provide better survival outcomes and comparable safety for Ad-HCC than T-A. T-M showed the great potential in the treatment of Ad-HCC aged population with relatively high tumor burden.

DISCUSSION

To reduce selective bias, we strictly selected the enrolled population and used different analytical methods, such as PSM and IPTW. A series of satisfactory results were found and were consistent between the different analytical methods. TRIPLET yielded a better overall ORR (65.9%) than HAIC, TKIs or PD-1 inhibitors in previous reports[18-21]. This means that the synergistic effect of the three combined treatments is beneficial for improving the ORR. On this basis, the application of MWA after TRIPLET can further improve ORR (90.5%) over T-A. Moreover, T-M resulted in a longer OS than T-A in patients with Ad-HCC, which may be attributed to a longer RFS in patients who received MWA after multicycle TRIPLET (median PFS, T-M 20.0 months vs T-A 9.5 months). In particular, MWA also plays an important role in the control of extrahepatic metastatic lesions. In this study, except for MWA of hepatic tumors, lung metastasis, adrenal metastasis, and breast metastasis were also performed one by one, and better control for extrahepatic metastasis was achieved than T-A. In regard to safety, the spectrum, incidence, and severity of AEs observed in TRIPLET combination treatment were consistent with the known safety profile of each agent and the underlying disease. The combination of MWA with TRIPLET did not induce additional complications.

For these patients who underwent T-M, we have provided a detailed summary of the treatment parameters for MWA. The sessions, points, time, and power of MWA for intrahepatic lesions are higher than those for extrahepatic lesions, which may be closely related to the larger tumor burden of intrahepatic lesions. Among them, because of residual tumor activity after TRIPLET treatment, 87.4% of patients with HCC were treated with subsequent MWA to achieve complete eradication. However, 12.6% of patients experienced recurrent tumors after achieving OR, and they received MWA after TRIPLET, which suppressed tumor progression. Notably, incomplete ablation was an independent risk factor for PFS in the T-M group, which was consistent with previous studies[22]. Many experts have reported that inflammation induced by incomplete ablation accelerates tumor progression and hinders PD-1 immunotherapy. Several mechanisms underlying this process, such as an incomplete ablation-induced hypoxic microenvironment, activation of tumor-derived endothelial cells, epithelial-mesenchymal transition and autophagy, have been revealed[21,23,24].

In the subgroup analysis, T-M provided better disease control and long-term survival for Ad-HCC patients with a high tumor burden (e.g., maximum tumor diameter > 10 cm). The reason may be as follows: After multicycle TRIPLET, the vast majority of HCC shows necrosis and shrinkage, and TKIs in the TRIPLET protocol might block HCC cell proliferation and induce tumor cell apoptosis in HCC cells. MWA is prone to complete ablation for residual components. The results from previous studies indicate that a low intrahepatic tumor burden can improve the survival benefit in patients with Ad-HCC[25,26], which further proves the rationale for the concurrent application of TRIPLET with MWA to effectively control intrahepatic tumors[2]. Fukuda et al[13] found that sorafenib administered before TA could increase the ablation-induced coagulation necrosis range due to decreasing blood flow in the tumor and nontumor areas in patients with HCC, which contributed to improving the probability of complete ablation. However, some studies have proven that incomplete tumor ablation enhances local tumor angiogenesis and promotes the rapid progression of residual HCC. Therefore, complete ablation after TRIPLET can also be indicate its effectiveness for preventing tumor recurrence.

In the multivariate Cox regression analyses for OS, ALBI grade, tumor number and treatment allocation were risk factors. Tumor burden and liver function have always been the focus of HCC prognosis by clinicians[27,28]. More than three tumors were regarded as difficult to receive complete ablation with one session, and patients with poor liver function were not allowed to receive more sessions of MWA. In addition, tumor number, metastasis and treatment allocation were risk factors for PFS, and these results were consistent with previous reports. Therefore, MWA after TRIPLET should be advocated as an effective treatment for Ad-HCC. For those with vascular invasion and metastasis, T-M can also play an important role in preventing recurrence and prolonging survival time. This is mainly because the tumor after ablation releases many immune antigens, which not only improves the suppression of PD-1 inhibitors on tumors in the whole body but also effectively changes the tumor microenvironment in the liver[22,29,30].

This study also has several limitations. First, this is a small sample size, retrospective study with a relatively short follow-up period. Although the baseline demographics were matched well between the two groups, prospective randomized controlled trials are still needed. Second, this study enrolled most patients with large HCC and HBV infection as a predominant etiology of HCC in China. It remains to be elucidated whether the results could be widely applied in Western countries, where the majority of patients have a low tumor burden or alcoholic liver cirrhosis as the predominant etiology. Third, although subgroup analyses have been performed, the combination and time interval of multiple treatments over time and the fact that some conversion therapies were not adapted to systemic therapy as tumor progression was required in the international guidelines have contributed to a possible bias. Finally, because some unknown risk factors were not collected and analyzed, residual confounding is difficult to avoid.

CONCLUSION

T-M provides a better overall ORR and survival benefit than T-A with a comparable safety profile as a new therapeutic option for patients with Ad-HCC. Interventional radiologists should evaluate the age, sex, HBV, tumor diameter, and presence of vascular invasion before TRIPLET to balance the risk-benefit between T-M and T-A.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Yan Fu for assistance with the clinical management of the patients and preparation of figures.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou, China (B2023-411-01).

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the analysis.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

P-Reviewer: Chisthi MM, India; Pham TTT, Viet Nam S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang L

Contributor Information

Meng-Xuan Zuo, Department of Minimally Invasive Interventional Therapy, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou 510060, Guangdong Province, China.

Chao An, Department of Interventional Ultrasound, Chinese General PLA Hospital, Beijing 100853, China.

Yu-Zhe Cao, Department of Minimally Invasive Interventional Therapy, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou 510060, Guangdong Province, China.

Jia-Yu Pan, Department of Minimally Invasive Interventional Therapy, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou 510060, Guangdong Province, China.

Lu-Ping Xie, Department of Minimally Invasive Interventional Therapy, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou 510060, Guangdong Province, China.

Xin-Jing Yang, Department of Minimally Invasive Interventional Therapy, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou 510060, Guangdong Province, China.

Wang Li, Department of Medical Imaging and Interventional Radiology, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou 510060, Guangdong Province, China.

Pei-Hong Wu, Department of Medical Imaging and Interventional Radiology, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou 510060, Guangdong Province, China. wuph@sysucc.org.cn.

Data sharing statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villanueva A. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1450–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1713263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, Zhu AX, Finn RS, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR, Heimbach JK. Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68:723–750. doi: 10.1002/hep.29913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torzilli G, Belghiti J, Kokudo N, Takayama T, Capussotti L, Nuzzo G, Vauthey JN, Choti MA, De Santibanes E, Donadon M, Morenghi E, Makuuchi M. A snapshot of the effective indications and results of surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma in tertiary referral centers: is it adherent to the EASL/AASLD recommendations?: an observational study of the HCC East-West study group. Ann Surg. 2013;257:929–937. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828329b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park JW, Chen M, Colombo M, Roberts LR, Schwartz M, Chen PJ, Kudo M, Johnson P, Wagner S, Orsini LS, Sherman M. Global patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma management from diagnosis to death: the BRIDGE Study. Liver Int. 2015;35:2155–2166. doi: 10.1111/liv.12818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benson AB, D'Angelica MI, Abbott DE, Anaya DA, Anders R, Are C, Bachini M, Borad M, Brown D, Burgoyne A, Chahal P, Chang DT, Cloyd J, Covey AM, Glazer ES, Goyal L, Hawkins WG, Iyer R, Jacob R, Kelley RK, Kim R, Levine M, Palta M, Park JO, Raman S, Reddy S, Sahai V, Schefter T, Singh G, Stein S, Vauthey JN, Venook AP, Yopp A, McMillian NR, Hochstetler C, Darlow SD. Hepatobiliary Cancers, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:541–565. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sidaway P. Axicabtagene effective in indolent NHL. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:150. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00596-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sidaway P. FOLFOX-HAIC active in large HCC. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:5. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00577-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyu N, Kong Y, Mu L, Lin Y, Li J, Liu Y, Zhang Z, Zheng L, Deng H, Li S, Xie Q, Guo R, Shi M, Xu L, Cai X, Wu P, Zhao M. Hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil/leucovorin vs. sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, Kudo M, Breder V, Merle P, Kaseb AO, Li D, Verret W, Xu DZ, Hernandez S, Liu J, Huang C, Mulla S, Wang Y, Lim HY, Zhu AX, Cheng AL IMbrave150 Investigators. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1894–1905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He M, Li Q, Zou R, Shen J, Fang W, Tan G, Zhou Y, Wu X, Xu L, Wei W, Le Y, Zhou Z, Zhao M, Guo Y, Guo R, Chen M, Shi M. Sorafenib Plus Hepatic Arterial Infusion of Oxaliplatin, Fluorouracil, and Leucovorin vs Sorafenib Alone for Hepatocellular Carcinoma With Portal Vein Invasion: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:953–960. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Q, Han J, Yang Y, Chen Y. PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1070961. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1070961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuda H, Numata K, Moriya S, Shimoyama Y, Ishii T, Nozaki A, Kondo M, Morimoto M, Maeda S, Sakamaki K, Morita S, Tanaka K. Hepatocellular carcinoma: concomitant sorafenib promotes necrosis after radiofrequency ablation--propensity score matching analysis. Radiology. 2014;272:598–604. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14131640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haber PK, Puigvehí M, Castet F, Lourdusamy V, Montal R, Tabrizian P, Buckstein M, Kim E, Villanueva A, Schwartz M, Llovet JM. Evidence-Based Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials (2002-2020) Gastroenterology. 2021;161:879–898. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kudo M. Scientific Rationale for Combined Immunotherapy with PD-1/PD-L1 Antibodies and VEGF Inhibitors in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12 doi: 10.3390/cancers12051089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:52–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel IJ, Rahim S, Davidson JC, Hanks SE, Tam AL, Walker TG, Wilkins LR, Sarode R, Weinberg I. Society of Interventional Radiology Consensus Guidelines for the Periprocedural Management of Thrombotic and Bleeding Risk in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Image-Guided Interventions-Part II: Recommendations: Endorsed by the Canadian Association for Interventional Radiology and the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2019;30:1168–1184.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2019.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li QJ, He MK, Chen HW, Fang WQ, Zhou YM, Xu L, Wei W, Zhang YJ, Guo Y, Guo RP, Chen MS, Shi M. Hepatic Arterial Infusion of Oxaliplatin, Fluorouracil, and Leucovorin Versus Transarterial Chemoembolization for Large Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Randomized Phase III Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:150–160. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ueshima K, Ogasawara S, Ikeda M, Yasui Y, Terashima T, Yamashita T, Obi S, Sato S, Aikata H, Ohmura T, Kuroda H, Ohki T, Nagashima K, Ooka Y, Takita M, Kurosaki M, Chayama K, Kaneko S, Izumi N, Kato N, Kudo M, Omata M. Hepatic Arterial Infusion Chemotherapy versus Sorafenib in Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2020;9:583–595. doi: 10.1159/000508724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rallis KS, Makrakis D, Ziogas IA, Tsoulfas G. Immunotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: From clinical trials to real-world data and future advances. World J Clin Oncol. 2022;13:448–472. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v13.i6.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mou L, Tian X, Zhou B, Zhan Y, Chen J, Lu Y, Deng J, Deng Y, Wu Z, Li Q, Song Y, Zhang H, Chen J, Tian K, Ni Y, Pu Z. Improving Outcomes of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: New Data and Ongoing Trials. Front Oncol. 2021;11:752725. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.752725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Brown RE, Martin RC. Incomplete thermal ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma: effects on tumor proliferation. J Surg Res. 2013;181:250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qi X, Yang M, Ma L, Sauer M, Avella D, Kaifi JT, Bryan J, Cheng K, Staveley-O'Carroll KF, Kimchi ET, Li G. Synergizing sunitinib and radiofrequency ablation to treat hepatocellular cancer by triggering the antitumor immune response. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu B, Yu M, Ma X, Sun J, Liu C, Wang C, Wu S, Fu P, Yang Z, He Y, Zhu Y, Huang C, Yang X, Shi Y, Qiu S, Sun H, Zhu AX, Zhou J, Xu Y, Zhu D, Fan J. IFNα Potentiates Anti-PD-1 Efficacy by Remodeling Glucose Metabolism in the Hepatocellular Carcinoma Microenvironment. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:1718–1741. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka K, Yabushita Y, Nakagawa K, Kumamoto T, Matsuo K, Taguri M, Endo I. Debulking surgery followed by intraarterial 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy plus subcutaneous interferon alfa for massive hepatocellular carcinoma with multiple intrahepatic metastases: a pilot study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:1364–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Stefano G, Iodice V, Signoriello G, Scognamiglio U, Farella N. P1325: Efficacy and safety of combined sequential treatment with RFA and sorafenib in patients with HCC in intermediate stage ineligible for tace: A prospective randomized open study. J Hepatol. 2015;62:S852. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, Ferrer-Fàbrega J, Burrel M, Garcia-Criado Á, Kelley RK, Galle PR, Mazzaferro V, Salem R, Sangro B, Singal AG, Vogel A, Fuster J, Ayuso C, Bruix J. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J Hepatol. 2022;76:681–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Kudo M, Hirooka M, Tsuji K, Itobayashi E, Kariyama K, Ishikawa T, Tajiri K, Ochi H, Tada T, Toyoda H, Nouso K, Joko K, Kawasaki H, Hiasa Y, Michitaka K Real-Life Practice Experts for HCC (RELPEC) Study Group and HCC 48 Group (hepatocellular carcinoma experts from 48 clinics) Albumin-Bilirubin (ALBI) Grade as Part of the Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline for HCC of the Japan Society of Hepatology: A Comparison with the Liver Damage and Child-Pugh Classifications. Liver Cancer. 2017;6:204–215. doi: 10.1159/000452846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen F, Bao H, Xie H, Tian G, Jiang T. Heat shock protein expression and autophagy after incomplete thermal ablation and their correlation. Int J Hyperthermia. 2019;36:95–103. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2018.1536285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdalla M, Collings AT, Dirks R, Onkendi E, Nelson D, Ozair A, Miraflor E, Rahman F, Whiteside J, Shah MM, Ayloo S, Abou-Setta A, Sucandy I, Kchaou A, Douglas S, Polanco P, Vreeland T, Buell J, Ansari MT, Pryor AD, Slater BJ, Awad Z, Richardson W, Alseidi A, Jeyarajah DR, Ceppa E. Surgical approach to microwave and radiofrequency liver ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma and colorectal liver metastases less than 5 cm: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:3340–3353. doi: 10.1007/s00464-022-09815-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.