Abstract

Background

Hyaluronic acid injections are increasingly administered for correction of infraorbital hollows (IOHs).

Objectives

The objective of this study was to examine the effectiveness (IOH correction) and safety of Restylane Eyelight hyaluronic acid (HAEYE) injections.

Methods

Patients with moderate/severe IOHs, assessed with the Galderma infraorbital hollows scale (GIHS), were randomized to HAEYE injections (by needle/cannula) (Day 1 + optional Month 1 touch-up) or no-treatment control. The primary endpoint was blinded evaluator–reported Month 3 response, defined as ≥1-point GIHS improvement from baseline (both sides, concurrently). Other endpoints examined investigator-reported aesthetic improvement on the Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (GAIS), patient-reported satisfaction (FACE-Q satisfaction with outcome; satisfaction questionnaire), and adverse events.

Results

Overall, 333 patients were randomized. Month 3 GIHS responder rate was significantly higher for HAEYE (87.4%) vs control (17.7%; P < .001), and comparable between HAEYE-needle and HAEYE-cannula groups (P = .967). HAEYE GAIS responder rate was 87.5-97.7% (Months 3-12). Mean FACE-Q Rasch-transformed scores were 64.3-73.5 (HAEYE) vs 14.1-16.2 (control) through Month 12. Patients reported looking younger (≥71%) and less tired (≥79%) with reduced undereye shadows (≥76%) and recovered within 3-5 hours posttreatment. Efficacy was maintained through Month 12 (63.5% GIHS responders) and through Month 18, after Month 12 retreatment (80.3% GIHS responders; 99.4% GAIS responders; FACE-Q scores 72.5-72.8). Forty patients (12.7%) reported typically mild adverse events (4.9% HAEYE-needle; 20.9% HAEYE-cannula).

Conclusions

HAEYE treatment was effective in correcting moderate/severe IOHs at the primary endpoint (Month 3). Efficacy was sustained through Month 12 after first treatment for 63.5% and through Month 18 for 80.3% (after 1 retreatment) with needle or cannula administration. Safety outcomes were reassuring.

Level of Evidence: 1

Changes in the infraorbital (tear trough) area of the face can result in “hollowing” around the eye.1-3 There is growing interest in hyaluronic acid (HA) injections as an effective nonsurgical approach to correct volume loss and the appearance of infraorbital hollows (IOHs).3-10 The tear trough is a notoriously challenging area to treat, requiring precision and an extensive understanding of the changes that affect anatomical structure of the face.3,9 Restylane Eyelight HA filler (HAEYE; Galderma, Uppsala, Sweden) is formulated with NASHA technology, resulting in a firm/strong gel (high G′) with a low degree of modification and low water absorption ability, making it suitable for this anatomical location.11,12 Case series data have shown effectiveness, durability, and high satisfaction with HAEYE in the treatment of IOHs, accompanied by a good safety profile.10,13-15 Treatment satisfaction is an important measure of success when assessing nonsurgical aesthetic treatments, particularly when examining therapies that target the infraorbital area, because the eyes are instrumental in projecting emotion as well as influencing perceptions of tiredness and age.3,16,17

The current study was a large randomized, controlled investigation to examine effectiveness, safety, and treatment satisfaction following administration of HAEYE treatment for injection in the correction of IOHs. The study aimed to compare treatment outcomes with HAEYE against a no-treatment control among patients with moderate or severe hollowing around the tear trough area.

METHODS

Randomized Study Design

A prospective, randomized, evaluator-blinded, no-treatment controlled, parallel group, multicenter study was conducted between November 2019 and April 2022, to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of HAEYE in the correction of IOHs (clinical trial registration no. NCT04154930). The study was carried out in accordance with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Food and Drug Administration as well as the Institutional Review Board for each participating study center. The study followed the international standard for clinical study of medical devices for human patients, ISO14155:2011, as applicable, for US regulations, and the International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use guideline for GCP (E6) as applicable for medical devices. Patients gave written informed consent. The study objective was to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of HAEYE in the correction of IOHs when administered by needle/cannula injection, with the primary objective of evaluating effectiveness at Month 3 compared with a no-treatment control.

Study Schedule and Treatment

Assessment scales applied throughout the study are shown in Table 1. Live blinded evaluator assessments were conducted at baseline and then during follow-up visits at Months 3, 6, 9 and 12. Treating investigator assessments were conducted at baseline and then at Months 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12.

Table 1.

Summary of Assessment Scales

| GIHS (Blinded evaluator assessment) |

GAIS (Treating investigator assessment) |

FACE-Q Psychological function (response scale) (Patient-reported) |

Patient satisfaction questionnaire (Patient-reported) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (none) | Very much improved | 1 (definitely disagree) | Very satisfied |

| 1 (mild) | Much improved | 2 (somewhat disagree) | Satisfied |

| 2 (moderate) | Improved | 3 (somewhat agree) | Neutral |

| 3 (severe) | No change | 4 (definitely agree) | Dissatisfied |

| Worse | Very dissatisfied | ||

| Much worse | |||

| Very much worse |

GAIS, Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale; GIHS, Galderma infraorbital hollow scale.

Patients were randomized 6:1 to receive either HAEYE treatment in the infraorbital area or no treatment (control). For patients randomized to HAEYE, the first treatment was administered at baseline with an optional touch-up treatment at Month 1. An additional (optional) retreatment was offered at Month 12 for patients treated with HAEYE at baseline in whom optimal aesthetic improvement had not been maintained. Patients in the no-treatment control group were also offered an HAEYE treatment at Month 12.

HAEYE was supplied in syringes containing 0.5 mL HAEYE (20 mg/mL stabilized HA and 3 mg/mL lidocaine). Approximately half of all study sites were selected to administer HAEYE treatment by needle (HAEYE-needle group) and the remaining sites administered treatment by cannula (HAEYE-cannula group) for all patients randomized to treatment. The same injection method (needle or cannula) performed at baseline was implemented at each subsequent touch-up treatment. The injection technique was at the discretion of the treating investigator. However, the trial protocol recommended serial puncture for needle injection and the fanning technique for cannula administration. HAEYE was placed in the supraperiosteal plane, at the junction of the lower eyelid and midface where a volume deficit had formed. This part of the face comprises the area bordered by the nasal sidewall medially, the temporal region of the bony orbit laterally, the bulk of the lower eyelid superiorly, and the superior aspect of the midface inferiorly.

All patients who received optional retreatment/treatment at Month 12 were followed up for effectiveness and safety outcomes for another 6 months. Treating investigators performed effectiveness and safety assessments at Months 13, 15 and 18 (ie, 1, 3 and 6 months postretreatment or post first treatment at Month 12 for controls). Blinded evaluator effectiveness assessments were also conducted at Months 15 and 18. A maximum injection volume of 1 mL (per side) was administered for each baseline treatment, touch-up, and optional treatment.

Study Population

Males and females, age >21 years, who had normal visual function test results were included in the study. Patients were required to have grade 2 (moderate) or 3 (severe) hollowing in the infraorbital area, according to blinded evaluator assessments, graded with the 4-point Galderma infraorbital hollows scale (GIHS): 0 (none), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), or 3 (severe).18

Patients were excluded if they had a known or previous allergy or hypersensitivity to any injectable HAs, any HAEYE constituents, or gram-positive bacterial proteins. Patients were not allowed to enter the study if they had previous or planned facial plastic surgery or cosmetic procedure(s) (eg, laser or chemical resurfacing, needling, facelift, or radiofrequency) that might interfere with effectiveness assessments. Any history of recurrent or chronic infraorbital edema, rosacea, uncontrolled severe seasonal allergies, inflammation, or pigmentation abnormalities around the eye area, retinal disease, detached retina or other condition associated with declining visual acuity precluded inclusion in the study. Patients could not participate if they had demonstrated weight loss or gain (≥2 body mass index [BMI] units) within 90 days of the study or planned to significantly gain or reduce their weight during the study period, or if they were pregnant, planning a pregnancy, or breastfeeding. In addition, patients were excluded if they had undergone previous lower eyelid surgery, including orbital or midface surgery; if they had a permanent implant or fat grafting or fat injections in the midfacial region that could interfere with effectiveness assessments; if they had lower lid retraction or exophthalmos, ectropium, entropion, or trichiasis of the lower eyelid; if they had a tendency to accumulate eyelid edema, had developed festoons, or had large or herniating infraorbital fat pads, skin or fat atrophy other than age-related in the midfacial or periorbicular regions; or if they had been diagnosed with a connective tissue disorder, skin laxity, or sun damage beyond typical for the patient's age.

Treatment Effectiveness and Patient Satisfaction Assessments

The primary effectiveness endpoint was the responder rate at Month 3, defined as those patients achieving ≥1-point improvement from baseline GIHS score on both sides of the face, concurrently, based upon blinded evaluator live assessment. Secondary effectiveness endpoints included responder rate (blinded evaluator assessments) at Months 6, 9, and 12 posttreatment and at Months 15 and 18 after optional retreatment/treatment (ie, 1, 3 and 6 months following retreatment or post first treatment at Month 12 for controls). Overall aesthetic improvement was evaluated as the proportion of patients achieving a Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale (GAIS) rating of “improved” or above (Table 1), based upon separate treating investigator and patient self-assessment evaluations, at all follow-up visits from baseline through Month 12 and at Months 15 and 18 (equivalent to 3 and 6 months following optional retreatment/treatment at Month 12).

Satisfaction with treatment results was assessed with the FACE-Q satisfaction with outcome questionnaire and patient satisfaction questionnaire. Responses for both questionnaires were reported at Months 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 from baseline, and at Months 15 and 18 (equivalent to 3 and 6 months following optional retreatment/treatment at Month 12). FACE-Q responses were converted to Rasch-transformed total scores to examine the change in patient satisfaction at each study visit.

Recovery time after treatment was reported according to the time taken for patients to feel comfortable returning to social engagement (eg, workplace, social event), based on patient diary card reporting.

Assessment of Safety

Adverse events (AEs) were reported throughout the study period by treating investigators. Visual function assessments (including Snellen visual acuity [VA], extraocular muscle function, and confrontation visual field testing) were performed both before and 30 minutes postinjection at baseline, optional touch-up, and optional retreatment/treatment. In addition, visual function assessments were performed on Day 14 after each treatment. Changes in Snellen VA of 1 line or more were reported as AEs of special interest (AESIs). Patients also reported in their diaries any incidence of predefined/expected symptoms (bruising, redness, pain, tenderness, lumps/bumps, itching, or swelling) or any other symptoms occurring during the first 28 days after treatment.

Statistical Methods

All statistical analyses were conducted with the SAS Version 9.4. Most variables were analyzed and reported according to the injection tool and group: HAEYE-needle, HAEYE-cannula, HAEYE-pooled (all patients receiving HAEYE treatment by needle or cannula) and control (no-treatment).

Randomization of patients to treatment was performed with a computer-generated randomization list stratified by Fitzpatrick skin type (FST) group (I-III, IV, and V-VI) and study site. The FST IV and FST V-VI groups were further stratified at needle or cannula level (needle sites were pooled into a needle stratum, and cannula sites pooled into a cannula stratum). Randomization numbers were allocated in ascending sequential order to each patient.

The intention-to-treat (ITT) population comprised all patients randomized at baseline. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, some patients had remote visits during the study. Therefore a modified intention-to-treat (mITT) population was created which included all patients in the ITT who did not have a GIHS outcome reported by remote assessment at Month 3. The per protocol population included all patients in the mITT population who completed the Month 3 posttreatment visit without any deviations considered to have a substantial impact on the primary effectiveness. The safety population included all patients who were treated with HAEYE or randomized to the control group and were analyzed according to the as-treated principle.

The primary effectiveness analysis for Month 3 GIHS responder rate vs control was performed for the mITT population with the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (CMH) test stratified by injection tool, with a sensitivity analysis conducted with the ITT population. Missing values were handled with multiple imputation. The Breslow-Day test for homogeneity of odds ratios was performed to assess consistency of treatment effect across injection tools. Secondary GIHS responder rates were analyzed with the CMH test stratified by injection tool on the ITT population (observed cases). Confidence intervals were calculated with normal approximation (Wald) throughout. All other endpoints were analyzed descriptively only.

RESULTS

Study Population

Demographic and baseline characteristic data are shown in Table 2. Overall, 333 patients at 16 study sites in the US were randomized. Most patients were female (87.1%), White (88.9%), and not of Hispanic or Latino origin (77.5%). Mean (standard deviation [SD]) age was 44.4 (11.67) years (range 22-73 years). The majority had Fitzpatrick skin type III (41.1%) or II (25.8%), and mean BMI was 25.4 kg/m2. All patients had GIHS scores of 2 (51.4% right; 52.3% left) or 3 (48.6% right; 47.7% left) at baseline. In total, 287 were randomized to receive HAEYE treatment (HAEYE-pooled); 148 were in the HAEYE-needle group and 139 in the HAEYE-cannula group. The control group (no treatment) contained 46 patients.

Table 2.

Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics (ITT Population)

| HAEYE-needle (n = 148) |

HAEYE-cannula (n = 139) |

HAEYE-pooled (n = 287) |

Control (n = 46) |

Total (n = 333) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 44.3 (12.15) | 44.2 (10.98) | 44.3 (11.58) | 45.5 (12.27) | 44.4 (11.67) | |||||

| Range | 22-73 | 24-72 | 22-73 | 24-63 | 22-73 | |||||

| >45 years, n (%) | 71 (48.0) | 69 (49.6) | 140 (48.8) | 22 (47.8) | 162 (48.6) | |||||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Female | 130 (87.8) | 122 (87.8) | 252 (87.8) | 38 (82.6) | 290 (87.1) | |||||

| Male | 18 (12.2) | 17 (12.2) | 35 (12.2) | 8 (17.4) | 43 (12.9) | |||||

| Race, n (%) | ||||||||||

| White | 133 (89.9) | 124 (89.2) | 257 (89.5) | 39 (84.8) | 296 (88.9) | |||||

| Black/African American | 5 (3.4) | 12 (8.6) | 17 (5.9) | 4 (8.7) | 21 (6.3) | |||||

| Asian | 3 (2.0) | 1 (0.7) | 4 (1.4) | 1 (2.2) | 5 (1.5) | |||||

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | |||||

| Other | 7 (4.7) | 1 (0.7) | 8 (2.8) | 2 (4.3) | 10 (3.0) | |||||

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 40 (27.0) | 26 (18.7) | 66 (23.0) | 9 (19.6) | 75 (22.5) | |||||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 108 (73.0) | 113 (81.3) | 221 (77.0) | 37 (80.4) | 258 (77.5) | |||||

| Fitzpatrick skin type, n (%) | ||||||||||

| I–III | 97 (65.5) | 100 (71.9) | 197 (68.6) | 31 (67.4) | 228 (68.5) | |||||

| IV | 36 (24.3) | 26 (18.7) | 62 (21.6) | 10 (21.7) | 72 (21.6) | |||||

| V | 9 (6.1) | 4 (2.9) | 13 (4.5) | 3 (6.5) | 16 (4.8) | |||||

| VI | 6 (4.1) | 9 (6.5) | 15 (5.2) | 2 (4.3) | 17 (5.1) | |||||

| Blinded evaluator GIHS score, n (%) | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | Left |

| 2 | 79 (53.4) | 76 (51.4) | 68 (48.9) | 71 (51.1) | 147 (51.2) | 147 (51.2) | 24 (52.2) | 27 (58.7) | 171 (51.4) | 174 (52.3) |

| 3 | 69 (46.6) | 72 (48.6) | 71 (51.1) | 68 (48.9) | 140 (48.8) | 140 (48.8) | 22 (47.8) | 19 (41.3) | 162 (48.6) | 159 (47.7) |

A no-treatment control arm was utilized for comparison with HAEYE-needle and HAEYE-cannula treatment groups throughout the study. The ITT population comprised all patients who were randomized to the study at baseline. HAEYE-pooled included all patients receiving HAEYE treatment by needle or cannula. GIHS, Galderma infraorbital hollow scale; HAEYE, Restylane Eyelight hyaluronic acid treatment; ITT, intention-to-treat; SD, standard deviation.

Table 3 shows the injection volumes administered at each treatment and touch-up visit. The mean total injection volume, including baseline treatment and touch-up treatments, was similar for patients treated with HAEYE by needle (2.0 mL) and those treated by cannula (2.3 mL). Overall, 164 patients received HAEYE retreatment at Month 12; 88 by needle (mean volume 1.0 mL) and 76 by cannula (mean volume 1.2 mL). All HAEYE-needle participants received supraperiosteal injections only, whereas 99.3% of patients who received HAEYE-cannula had supraperiosteal injections and 16.7% also received injections at other depths. At the baseline treatment, 73.2% and 26.8% of patients received HAEYE-cannula treatment by a 25-gauge and a 27-gauge cannula, respectively. At Month 12, 32 patients in the control group opted to receive HAEYE treatment; 17 were injected by needle (100% supraperiosteal injections only; mean volume 1.5 mL) and 15 by cannula (100% had supraperiosteal injections and 13.3% had other depths; mean volume 1.5 mL). At Month 12, the controls received HAEYE-cannula treatment by 25-gauge (80.0%) and 27-gauge (20.0%) cannula. With both needle and cannula, various injection techniques were employed, the most common being serial puncture (as recommended) for needle injections, performed in 59% to 80% of patients across the treatment occasions, and linear retrograde for cannula injections, in 79% to 96% of patients. Around 20% to 33% of patients were injected with the recommended fanning technique for the cannula. A summary of the injection techniques administered at each treatment occasion is presented in Table 4.

Table 3.

Injection Volumes at Baseline Treatment and Touch-up (Safety Population)

| Injection volume, mL | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| HAEYE-needle (n = 163) |

HAEYE-cannula (n = 153) | HAEYE-pooled (n = 316) | |

| Baseline treatment | |||

| n | 146 | 138 | 284 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.5) | 1.3 (0.5) |

| Median | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Min, max | 0.4, 2.0 | 0.4, 2.0 | 0.4, 2.0 |

| Optional touch-up | |||

| n | 113 | 108 | 221 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.0 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.0 (0.5) |

| Median | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Min, max | 0.2, 2.0 | 0.2, 2.0 | 0.2, 2.0 |

| Baseline treatment + touch-up | |||

| n | 146 | 138 | 284 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.0 (0.8) | 2.3 (0.9) | 2.1 (0.9) |

| Median | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Min, max | 0.45, 4.0 | 0.4, 4.0 | 0.4, 4.0 |

| Optional retreatment | |||

| n | 88 | 76 | 164 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.0 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.6) | 1.1 (0.5) |

| Median | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Min, max | 0.2, 2.0 | 0.3, 2.0 | 0.2, 2.0 |

| Optional first treatment (no-treatment control) |

|||

| n | 17 | 15 | 32 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.5 (0.6) | 1.5 (0.5) | 1.5 (0.5) |

| Median | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| Min, max | 0.1, 2.0 | 0.5, 2.0 | 0.1, 2.0 |

Baseline treatment, optional touch-up treatment, and optional retreatment all refer to patients randomized to HAEYE treatment at baseline. Optional baseline treatment only refers to those patients in the no-treatment control group at baseline who were offered HAEYE treatment at Month 12. HAEYE-pooled includes all patients receiving HAEYE treatment by needle or cannula. HAEYE, Restylane Eyelight hyaluronic acid treatment; max, maximum; min, minimum; SD, standard deviation.

Table 4.

Injection Techniques at Each Treatment (Safety Population)

| n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| HAEYE-needle (n = 163) |

HAEYE-cannula (n = 153) |

HAEYE-pooled (n = 316) |

|

| Baseline treatment | |||

| n | 146 | 138 | 284 |

| Linear antegrade | 20 (13.7) | 12 (8.7) | 32 (11.3) |

| Linear retrograde | 13 (8.9) | 126 (91.3) | 139 (48.9) |

| Fanning | 0 | 46 (33.3) | 46 (16.2) |

| Microbolus | 67 (45.9) | 18 (13.0) | 85 (29.9) |

| Serial puncture | 117 (80.1) | 0 | 117 (41.2) |

| Optional touch-up | |||

| n | 113 | 108 | 221 |

| Linear antegrade | 17 (15.0) | 5 (4.6) | 22 (10.0) |

| Linear retrograde | 7 (6.2) | 104 (96.3) | 111 (50.2) |

| Fanning | 0 | 29 (26.9) | 29 (13.1) |

| Microbolus | 49 (43.4) | 17 (15.7) | 66 (29.9) |

| Serial puncture | 84 (74.3) | 0 | 84 (38.0) |

| Optional retreatment | |||

| n | 88 | 76 | 164 |

| Linear antegrade | 14 (15.9) | 12 (15.8) | 26 (15.9) |

| Linear retrograde | 14 (15.9) | 60 (78.9) | 74 (45.1) |

| Fanning | 0 | 23 (30.3) | 23 (14.0) |

| Microbolus | 45 (51.1) | 21 (27.6) | 66 (40.2) |

| Serial puncture | 60 (68.2) | 0 | 60 (36.6) |

| Optional first treatment (no-treatment control) |

|||

| n | 17 | 15 | 32 |

| Linear antegrade | 2 (11.8) | 0 | 2 (6.3) |

| Linear retrograde | 3 (17.6) | 14 (93.3) | 17 (53.1) |

| Fanning | 0 | 3 (20.0) | 3 (9.4) |

| Microbolus | 10 (58.8) | 4 (26.7) | 14 (43.8) |

| Serial puncture | 10 (58.8) | 0 | 10 (31.3) |

Baseline treatment, optional touch-up treatment, and optional retreatment all refer to patients randomized to HAEYE treatment at baseline. Optional first treatment only refers to those patients in the no-treatment control group at baseline who were offered HAEYE treatment at Month 12. HAEYE-pooled includes all patients receiving HAEYE treatment by needle or cannula. HAEYE, Restylane Eyelight hyaluronic acid treatment.

Effectiveness Outcomes

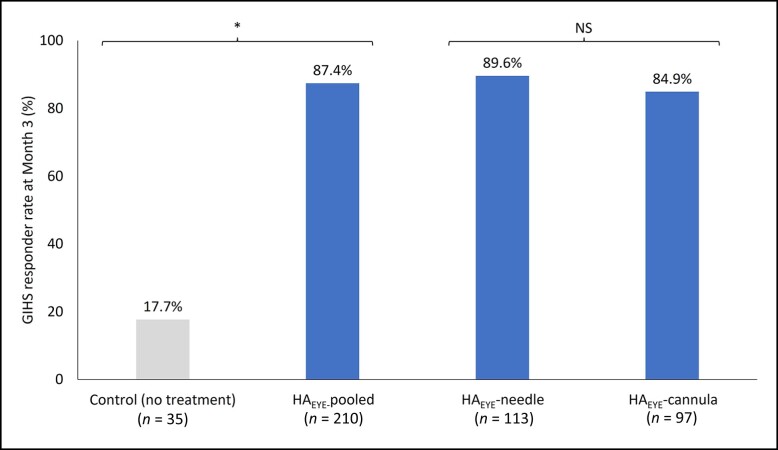

Figure 1 shows the Month 3 GIHS responder rate based upon blinded evaluator assessment. The GIHS responder rate at Month 3 after first treatment for all HAEYE recipients (87.4%) was statistically significantly higher (P < .001) than in the no-treatment control group (17.7%). The responder rate was 89.6% in the needle group and 84.9% in the cannula group. The difference in effect of HAEYE when administered by needle or cannula was not statistically significant (P = .967). Results were similar for the per protocol population and other sensitivity analyses.

Figure 1.

GIHS responder rate at Month 3: blinded evaluator assessment (mITT population). The difference between GIHS responder rates in the HAEYE-pooled group and the control group was statistically significant (P < .001) at Month 3. The analysis was performed with multiple imputation for missing data and the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test stratified by injection tool. The difference in effect of HAEYE when administered by needle or by cannula was not statistically significant (P = .967). Breslow-Day test was performed to assess the homogeneity of the odds ratios across injection tools. The mITT population included all patients who were randomized at baseline and who did not have their GIHS Month 3 visit assessment conducted remotely. HAEYE-pooled included all patients receiving HAEYE treatment by needle or cannula. GIHS, Galderma infraorbital hollow scale; HAEYE, Restylane Eyelight hyaluronic acid treatment; mITT, modified intention-to-treat; NS, not significant.

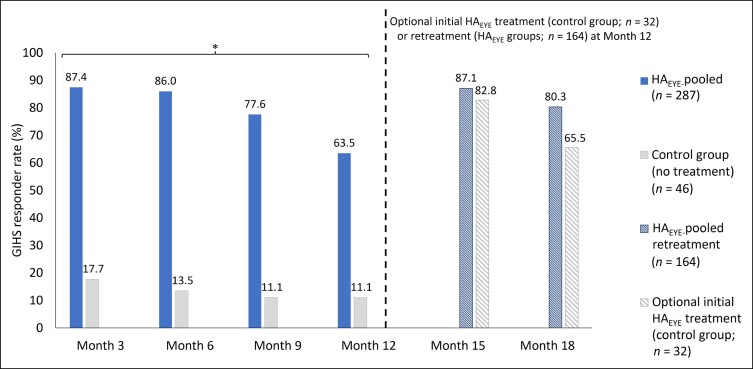

The GIHS responder rate remained statistically significantly higher in the HAEYE-pooled group compared with the control group at Months 6, 9 and 12 after first treatment (P < .001; Figure 2). GIHS responder rates were 86.0% (Month 6), 77.6% (Month 9) and 63.5% (Month 12) in the HAEYE-pooled group. Respective GIHS responder rates in the no-treatment control group were 13.5%, 11.1%, and 11.1%.

Figure 2.

Blinded evaluator–reported GIHS responder rate at Months 6, 9, and 12 and at Months 15 and 18 (3 and 6 months after optional treatment/retreatment at Month 12) (observed cases; ITT population). The difference between GIHS responder rates in the HAEYE-pooled group and the control (no-treatment) group was statistically significant at months 6, 9 and 12 (P < .001; Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test stratified by injection tool). An optional HAEYE treatment was offered at Month 12 to patients treated at baseline in whom optimal aesthetic improvement had not been maintained, and to patients in the control group. Only patients who had optional HAEYE retreatment (n = 164) or initial treatment at Month 12 (control group; n = 32) attended visits at Months 15 and 18 (corresponding to 3 and 6 months after retreatment/treatment). The ITT population included all patients who were randomized at baseline. HAEYE-pooled included all patients receiving HAEYE treatment by needle or cannula. GIHS, Galderma infraorbital hollow scale; HAEYE, Restylane Eyelight hyaluronic acid treatment; ITT, intention-to-treat.

HAEYE-pooled data showed that patients receiving an optional retreatment at Month 12 demonstrated GIHS responder rates of 87.1% and 80.3% at follow-up visits 3 and 6 months later (Month 15 and Month 18). Patients in the no-treatment control group who received an HAEYE treatment at Month 12 demonstrated GIHS responder rates of 82.8% and 65.5% at follow-up visits 3 and 6 months later.

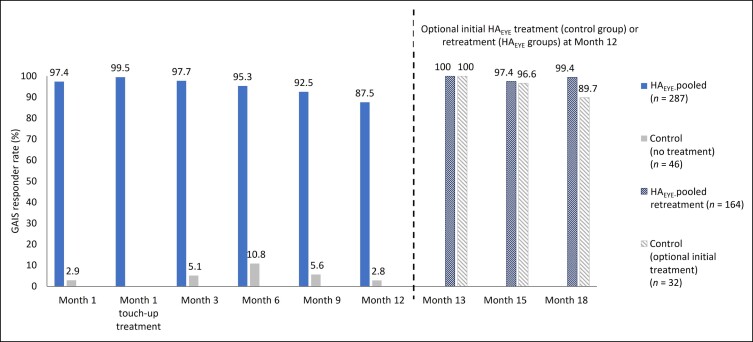

GAIS responder rates according to treating investigator assessments at each study visit are shown in Figure 3. GAIS responder rate for HAEYE-pooled patients was 97.4% at Month 1 and rose to 99.5% among those receiving a touch-up treatment. HAEYE-pooled data showed that GAIS responder rates were 97.7% at Month 3, 95.3% at Month 6, 92.5% at Month 9, and 87.5% at Month 12 after first treatment. HAEYE injection methods by needle and by cannula resulted in similar responder rates. GAIS responder rates ranged between 2.9% and 10.8% in the control group during the 12-month study period. HAEYE recipients who had an optional retreatment at Month 12 continued to show high GAIS responder rates at Months 13 (100%), 15 (97.4%), and 18 (99.4%). Patients in the control group who chose to receive an HAEYE treatment at Month 12 demonstrated GAIS responder rates of 100% (Month 13), 96.6% (Month 15), and 89.7% (Month 18). Patient-reported GAIS responder rates showed a similar pattern to those assessed by treating investigators throughout the study period (with responder rates of 95.0%, 79.8%, and 93.0% at Months 3, 12, and 18 in the group randomized to HAEYE).

Figure 3.

Treating investigator–reported GAIS responder rate at each study visit following HAEYE treatment (observed cases; ITT population). A responder was defined as a patient who indicated that their appearance was “improved,” “much improved,” or “very much improved” on the GAIS. An optional additional HAEYE treatment was offered at Month 12 to patients already treated at baseline in whom optimal aesthetic improvement had not been maintained, and to patients in the control group. Only patients who had HAEYE retreatment/treatment at Month 12 attended visits at Months 13, 15 and 18 (corresponding to 1, 3, and 6 months after retreatment/treatment at Month 12). The ITT population included all patients who were randomized at baseline. HAEYE-pooled included all patients receiving HAEYE treatment by needle or cannula. GAIS, Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale; HAEYE, Restylane Eyelight hyaluronic acid treatment; ITT, intention-to-treat.

Photographic outcomes are provided in Figure 4 for 3 patients, showing the treatment area before HAEYE injections, at Month 3, and at Month 12.

Figure 4.

Photographic outcomes for 3 patients before and after treatment with HAEYE. Images A-C show a White, 54-year-old, postmenopausal female treated with 2.0 mL HAEYE with a needle (1.0 mL on each side). (A) Before treatment, blinded evaluator GIHS score 3 (severe, both sides); (B) at Month 3, GIHS score 1 (mild, both sides); (C) at Month 12 before retreatment, GIHS score 0 (none, right) and 1 (mild, left). Images D-F show a White, 51-year-old male treated with 4.0 mL HAEYE (2.0 mL on each side) by cannula injection. (D) Before treatment, blinded evaluator GIHS score 3 (severe, both sides); (E) at Month 3, GIHS score 1 (mild, both sides); (F) at Month 12 before retreatment, GIHS scores 2 (moderate, right), 3 (severe, left). Images G-I show a White, 26-year-old female treated with 1.8 mL HAEYE (0.8 mL on right side and 1.0 mL on left side) by needle injection. (G) Before treatment, blinded evaluator GIHS score 2 (moderate, both sides); (H) at Month 3, GIHS score 0 (none, both sides); (I) at Month 12 before retreatment, GIHS score 1 (mild, both sides). GIHS, Galderma infraorbital hollow scale.

Satisfaction Outcomes

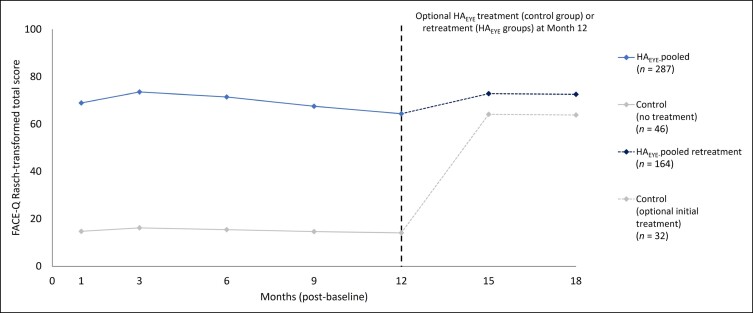

Mean FACE-Q satisfaction with outcome Rasch-transformed total scores ranged between 64.3 and 73.5 in HAEYE recipients (HAEYE-pooled) and between 14.1 and 16.2 in the control group through Month 12 after first treatment (Figure 5). Results were generally similar in the HAEYE-needle and HAEYE-cannula groups. Among those patients receiving retreatment or their first HAEYE treatment (control group) at Month 12, mean FACE-Q satisfaction with outcome scores was similar across previous HAEYE recipients (72.5-72.8) and former control group patients (63.8-64.1) at Months 15 and 18.

Figure 5.

FACE-Q satisfaction with outcome Rasch-transformed mean total scores at each visit (observed cases; ITT population). Satisfaction with outcome Rasch-transformed total scores ranged from 0 (worst) to 100 (best). Higher scores reflect a better outcome. Only patients who received an HAEYE retreatment (n = 164) or optional initial treatment (control group; n = 32) had visits at Months 15 and 18 (corresponding with 3 and 6 months after retreatment/treatment at Month 12). The ITT population included all patients who were randomized at baseline. HAEYE-pooled included all patients receiving HAEYE treatment by needle or cannula. HAEYE, Restylane Eyelight hyaluronic acid treatment; ITT, intention-to-treat.

From Month 1 through Month 12 after the first treatment, patient satisfaction questionnaire responses revealed that most patients treated with HAEYE felt that they looked younger (≥71%; Month 1: 71%; Month 3: 80%; Month 12: 72%) and less tired (≥79%; Month 1: 82%; Month 3: 87%; Month 12: 79%); had reduced shadows under their eyes (≥76%; Month 1: 79%; Month 3: 83%; Month 12: 76%); and felt better about themselves (≥74%; Month 1: 81%; Month 3: 82%; Month 12: 75%). Optional retreatment (HAEYE-pooled) or treatment (control group) at Month 12 resulted in continued high satisfaction scores at Months 15 and 18 regarding looking younger (HAEYE-pooled: ≥ 84%; control: ≥ 66%) and less tired (HAEYE-pooled: 87%; control: ≥ 76%); and having reduced shadows under the eye (HAEYE-pooled: ≥ 82%; control: ≥ 79%). In the group randomized to HAEYE-treatment, 93% responded “Yes” at both Months 12 and 18 when asked whether they would like to receive the treatment again. Patients also reported that the treatment results looked natural throughout the study in the HAEYE-pooled group (90%, 92%, and 89% at Months 1, 3, and 12, and 91% and 92% at Months 15 and 18 following retreatment).

HAEYE-pooled needle and cannula data showed that the median time for patients to feel comfortable returning to social engagements was 2.89 hours after baseline HAEYE treatment, 3.96 hours after receiving an optional touch-up treatment, and 4.70 hours after retreatment at Month 12.

Safety Outcomes

All AESIs (associated with changes in visual functioning) were mild and not related to study product or not clinically significant. Almost all patients in both treatment groups (92% [needle], 99% [cannula]) reported 1 or more of the predefined injection-related events (bruising [67% with needle, 59% with cannula]; redness [64%, 59%]; pain [49%, 71%]; tenderness [83%, 97%]; lumps/bumps [47%, 60%]; itching [11%, 18%]; or swelling [82%, 88%]) in patient diaries after treatment at baseline, and these were typically reported to be tolerable (≥74.7%), with a duration ≤7 days (≥57%). A similar pattern also was reported following touch-up and retreatment.

In addition, investigators reported mild/moderate treatment- or procedure-related AEs for 40 (12.7%) HAEYE recipients; 8 (4.9%) patients in the HAEYE-needle group and 32 (20.9%) in the HAEYE-cannula group after initial treatment (including touch-up). The most common types of treatment-related AEs (>1% of patients) were implant site swelling, implant site pain, headache, implant site bruising, implant site mass, and implant site edema (Table 5). The median time to onset of a treatment-related AE was 2 days and the median duration of AEs was 4 days. Following retreatment, 6 (3.7%) patients reported AEs related to HAEYE or the procedure, all of mild intensity; 4 (2.4%) reported AEs at the site of administration and 2 (1.2%) experienced headache. Median time to onset of an AE following retreatment was 1 day and median duration of these AEs was 5 days.

Table 5.

Treatment-related Adverse Events After HAEYE Treatment: General Disorders and Administration Site (Safety Population)

| Events | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| System organ class preferred term | HAEYE-needle n (%) |

HAEYE-cannula n (%) |

HAEYE-pooled n (%) |

| Initial HAEYE treatment | (n = 163) | (n = 153) | (n = 316) |

| Patients with at least 1 adverse event related to study product or injection procedure | 8 (4.9) | 32 (20.9) | 40 (12.7) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 7 (4.3) | 22 (14.4) | 29 (9.2) |

| Implant site swelling | 4 (2.5) | 8 (5.2) | 12 (3.8) |

| Implant site pain | 0 | 8 (5.2) | 8 (2.5) |

| Implant site bruising | 1 (0.6) | 4 (2.6) | 5 (1.6) |

| Implant site mass | 2 (1.2) | 2 (1.3) | 4 (1.3) |

| Implant site edema | 0 | 4 (2.6) | 4 (1.3) |

| Implant site pruritus | 0 | 2 (1.3) | 2 (0.6) |

| Implant site discoloration | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Implant site induration | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Implant site paresthesia | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Nervous system disorders | 1 (0.6) | 8 (5.2) | 9 (2.8) |

| Headache | 1 (0.6) | 6 (3.9) | 7 (2.2) |

| Hypesthesia | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Syncope | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 1 (0.6) | 3 (2.0) | 4 (1.3) |

| Postinflammatory pigmentation change | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Skin discoloration | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Skin hyperpigmentation | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Telangiectasia | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Immune system disorders | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Immunization reaction | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Injury, poisoning, and procedural complications | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Contusion | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| HAEYE retreatment | (n = 88) | (n = 76) | (n = 164) |

| Patients with at least 1 adverse event related to study product or injection procedure | 1 (1.1) | 5 (6.6) | 6 (3.7) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 1 (1.1) | 3 (3.9) | 4 (2.4) |

| Implant site swelling | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.6) | 3 (1.8) |

| Implant site bruising | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) |

| Implant site edema | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) |

| Nervous system disorders | 0 | 2 (2.6) | 2 (1.2) |

| Headache | 0 | 2 (2.6) | 2 (1.2) |

Initial treatment includes AEs that started on or after baseline treatment until optional retreatment. Retreatment includes AEs from patients randomized to HAEYE that started on or after their optional retreatment. HAEYE-pooled includes all patients receiving HAEYE treatment by needle or cannula. AEs, adverse events; HAEYE, Restylane Eyelight hyaluronic acid treatment.

DISCUSSION

The results from this pivotal, randomized, no-treatment controlled study demonstrated that HAEYE administration provides an effective, durable, and well-tolerated option for the correction of moderate and severe IOHs, regardless of the injection method (needle or cannula). Reported outcomes were consistent with those seen in previous case series studies examining the effectiveness and safety of HAEYE injections in the correction of IOHs and provide further evidence of effectiveness and tolerability for this indication.7,8,13 Although the randomized controlled study design and study population size were overall robust for showing effectiveness and safety, one limitation was that the study population consisted mainly of White (89%) and female (87%) patients and therefore did not represent all ethnicities or both sexes to equal extent.

The pivotal randomized study met the primary endpoint. HAEYE treatment resulted in a higher GIHS responder rate when compared with the no-treatment control group at Month 3 after the first treatment, and the between-group difference was statistically significant (P < .001). HAEYE treatment effectiveness was durable and sustained throughout the study period, with the between-group difference in GIHS responder rate remaining statistically significant throughout the study period up to Month 12. (P < .001). This translated to a duration of 11 to 12 months after the last treatment, depending on whether patients received a touch-up treatment or not at Month 1. These results compare favorably with systematic review data from 8 published studies, which indicate that duration of treatment effect typically lasts for 10.8 months.7,19 Retreatment at Month 12 restored GIHS responder rate alongside GAIS and FACE-Q satisfaction scores, all of which remained high through Month 18. Further studies are needed to evaluate durations beyond 12 months without retreatment.

Investigator-assessed GAIS scores were above 87.5% in HAEYE recipients, highlighting the overall aesthetic results observed with IOH correction and tear trough rejuvenation, and remained similar throughout the study, irrespective of whether treatment was administered by needle or cannula. Patient-assessed GAIS responder rates were also similar to investigator-reported data. Systematic review data suggest that HA fillers provide aesthetic improvements for 6 to 12 months; the outcomes reported in the current study are therefore consistent with the longest durations published.19 These results are in line with other published studies, which typically show sustained and high levels of aesthetic improvement with HA fillers for correction of IOHs.

Patient satisfaction is an important indicator of treatment success and also a key factor in decisions to undergo further cosmetic procedures.20 Patient perspective when evaluating treatment effectiveness, as well as tolerability and safety aspects, should be included in studies. Patient-reported satisfaction is typically high in studies in which correction of tear trough abnormalities with HA filler products is investigated.19,21-23 Our results reflected those previously reported for HA fillers, with elevated levels of satisfaction after HAEYE treatment.19,21-23 High FACE-Q satisfaction with outcome Rasch-transformed total scores showed that HAEYE recipients were satisfied with their treatment from Month 1 through Month 12 after first treatment (mean range: 64.3 to 73.5) compared with the no-treatment control group (mean range: 14.1 to 16.2). Patients who received retreatment at Month 12 continued to report high satisfaction with HAEYE treatment through Month 18. Again, results were generally consistent between patients in the HAEYE-needle and HAEYE-cannula groups and reflected previous FACE-Q data associated with HA filler treatment in the tear trough area.7,23 HAEYE treatment was associated with high patient satisfaction questionnaire scores, with the majority indicating that they looked less tired (>78%) and younger (>70%), with reduced shadows under their eyes (>76%). Recovery time was rapid following HAEYE administration, with participants feeling comfortable to return to social engagement within 3 hours after baseline treatment and approximately 4 to 5 hours after touch-up or retreatment.

HAEYE treatment was generally well tolerated throughout the study, with typically mild treatment-related AEs reported, which occurred around the eye area (eg, edema, bruising) and were aligned with those reported in previous HAEYE studies.7,8,13 Visual function was unaffected by HAEYE injections and no AESIs were considered related to the study treatment. There were no confirmed cases of Tyndall effect in the current study, whereas Tyndall effect (bluish discoloration) has been reported following initial and repeat treatments with other HA filler products.22

The data reported here demonstrate that HAEYE injections provide an effective, durable, and well tolerated nonsurgical option for the correction of IOHs. Rapid recovery time and high response rates following retreatment (with typically mild complications reported) make HAEYE a convenient option that can be offered as a repeat treatment for corrections of abnormalities in this challenging facial area.

CONCLUSIONS

This pivotal study demonstrated HAEYE to be effective and well tolerated for the correction of moderate to severe IOHs in patients over 21 years of age. The IOH correction was sustained in the majority of patients through Month 12 after the first treatment and up to Month 18 for individuals retreated at 12 months. GIHS improvement was similar regardless of whether treatment was performed with a needle or cannula. Aesthetic improvement (GAIS) and patient satisfaction (FACE-Q) were high throughout the study, and the treatment was well tolerated.

Acknowledgments

Anne Chapas, Deanna Mraz Robinson, Keith Marcus, Rob Schwarcz, Sherriff Ibrahim, and Brooke Sikora are acknowledged for their contributions as clinical investigators in the study.

Medical writing services were provided on behalf of the authors by Rebecca Down at Copperfox Communications Limited (Cambridge, UK) and Zenith Healthcare Communications Limited (Chester, UK).

Disclosures

Dr Biesman, Dr Green, Dr Jones, and Dr Grunebaum were investigators in the study. Dr Beer and Dr George are investigators and consultants for Galderma (Uppsala, Sweden), Allergan (Irvine, CA), and Merz (Frankfurt, Germany). Dr Jacob and Dr Joseph are investigators and speakers for Galderma. Dr Palm is an investigator, speaker, paid advisory board member, and consultant for Galderma. Dr Cho is an investigator for Galderma, a consultant for Galderma, Allergan, and Merz, and a speaker for Galderma and Allergan. Dr Almegård, Dr Weinberg, and Dr Bromée are employees of Galderma.

Funding

The study and medical writing support were funded by Galderma (Uppsala, Sweden) and Galderma Research and Development (GLLC; Dallas, TX). As stated in the affiliations and disclosures statements, Galderma employees Drs Almegård, Weinberg, and Bromée participated as coauthors and in journal selection.

REFERENCES

- 1. Farkas JP, Pessa JE, Hubbard B, Rohrich RJ. The science and theory behind facial aging. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2013;1(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0b013e31828ed1da [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Park KY, Kwon HJ, Youn CS, Seo SJ, Kim MN. Treatments of infra-orbital dark circles by various etiologies. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30(5):522–528. doi: 10.5021/ad.2018.30.5.522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anido J, Fernández JM, Genol I, Ribé N, Pérez Sevilla G. Recommendations for the treatment of tear trough deformity with cross-linked hyaluronic acid filler. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(1):6–17. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ziai K, Lighthall JG. Periocular rejuvenation using hyaluronic acid fillers. Plast Aesthet Res. 2020;7:53. 10.20517/2347-9264.2020.151. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Greene JJ, Sidle DM. The hyaluronic acid fillers: current understanding of the tissue device interface. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2015;23(4):423–432. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2015.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee JC, Lorenc ZP. Synthetic fillers for facial rejuvenation. Clin Plast Surg. 2016;43(3):497–503. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2016.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Trinh LN, Grond SE, Gupta A. Dermal fillers for tear trough rejuvenation: a systematic review. Facial Plast Surg. 2022;38(3):228–239. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1731348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Berguiga M, Galatoire O. Tear trough rejuvenation: a safety evaluation of the treatment by a semi-cross-linked hyaluronic acid filler. Orbit. 2017;36(1):22–26. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2017.1279641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nikolis A, Chesnut C, Biesman B, et al. Expert recommendations on the use of hyaluronic acid filler for tear trough rejuvenation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21(4):387–392. doi: 10.36849/JDD.6597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gorbea E, Kidwai S, Rosenberg J. Nonsurgical tear trough volumization: a systematic review of patient satisfaction. Aesthet Surg J. 2021;41(8):NP1053–NP1060. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjab116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Galderma US. Restylane EYELIGHT prescribing information . Accessed April 2024. https://www.restylaneusa.com/docs/Restylane-Eyelight-IFU.

- 12. Öhrlund Å. Water uptake of hyaluronic acid fillers. Poster Presented at IMCAS 2022, June 3-5, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goldberg RA, Fiaschetti D. Filling the periorbital hollows with hyaluronic acid gel: initial experience with 244 injections. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22(5):335–341; discussion 341-3. doi: 10.1097/01.iop.0000235820.00633.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Viana GAP, Osaki MH, Cariello AJ, Damasceno RW, Osaki TH. Treatment of the tear trough deformity with hyaluronic acid. Aesthet Surg J. 2011;31(2):225–231. doi: 10.1177/1090820X10395505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Donath AS, Glasgold RA, Meier J, Glasgold MJ. Quantitative evaluation of volume augmentation in the tear trough with a hyaluronic acid-based filler: a three-dimensional analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(5):1515–1522. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181d70317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wegrzyn M, Vogt M, Kireclioglu B, Schneider J, Kissler J. Mapping the emotional face. How individual face parts contribute to successful emotion recognition. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0177239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chatterjee A, Thomas A, Smith SE, Aguirre GK. The neural response to facial attractiveness. Neuropsychology. 2009;23(2):135–143. doi: 10.1037/a0014430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moradi A, Lin X, Allen S, Fagien S, Norberg M, Smith S. Validation of photonumeric assessment scales for temple volume deficit, infraorbital hollows, and chin retrusion. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46(9):1148–1154. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000002269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. D’Amato S, Fragola R, Bove P, et al. Is the treatment of the tear trough deformity with hyaluronic acid injections a safe procedure? A systematic review. Appl Sci. 2021;11(23):11489. doi: 10.3390/app112311489 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maisel A, Waldman A, Furlan K, et al. Self-reported patient motivations for seeking cosmetic procedures. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(10):1167. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Diwan Z, Trikha S, Etemad-Shahidi S, Alli Z, Rennie C, Penny A. A prospective study on safety, complications and satisfaction analysis for tear trough rejuvenation using hyaluronic acid dermal fillers. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(4):e2753. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fabi S, Zoumalan C, Fagien S, Yoelin S, Sartor M, Chawla S. A prospective, multicenter, single-blind, randomized, controlled study of VYC-15L, a hyaluronic acid filler, in adults for correction of infraorbital hollowing. Aesthet Surg J. 2021;41(11):NP1675–NP1685. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjab308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hall MB, Roy S, Buckingham ED. Novel use of a volumizing hyaluronic acid filler for treatment of infraorbital hollows. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2018;20(5):367–372. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2018.0230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]