Abstract

Background

Childhood obesity is a growing concern, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a significant consequence. Currently, there are no approved drugs to treat NAFLD in children. However, a recent study explored the potential of vitamin E enriched with tocotrienol (TRF) as a powerful antioxidant for NAFLD. The aims of the present study were to investigate the effectiveness and safety of TRF in managing children with obesity and NAFLD.

Methods

A total of 29 patients aged 10 to 18 received a daily oral dose of 50 mg TRF for six months (January 2020 to February 2022), and all had fatty liver disease were detected by ultrasonography and abnormally high alanine transaminase levels (at least two-fold higher than the upper limits for their respective genders). Various parameters, including biochemical markers, FibroScan, LiverFASt, DNA damage, and cytokine expression, were monitored.

Results

APO-A1 and AST levels decreased significantly from 1.39 ± 0.3 to 1.22 ± 0.2 g/L (P = 0.002) and from 30 ± 12 to 22 ± 10 g/L (P = 0.038), respectively, in the TRF group post-intervention. Hepatic steatosis was significantly reduced in the placebo group from 309.38 ± 53.60 db/m to 277.62 ± 39.55 db/m (p = 0.048), but not in the TRF group. Comet assay analysis showed a significant reduction in the DNA damage parameters in the TRF group in the post-intervention period compared to the baseline, with tail length decreasing from 28.34 ± 10.9 to 21.69 ± 9.84; (p = 0.049) and with tail DNA (%) decreasing from 54.13 ± 22.1to 46.23 ± 17.9; (p = 0.043). Pro-inflammatory cytokine expression levels were significantly lower in the TRF group compared to baseline levels for IL-6 (2.10 6.3 to 0.7 1.0 pg/mL; p = 0.047 pg/mL) and TNF-1 (1.73 5.5 pg/mL to 0.7 0.5 pg/mL; p = 0.045).

Conclusion

The study provides evidence that TRF supplementation may offer a risk-free treatment option for children with obesity and NAFLD. The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of TRF offer a promising adjuvant therapy for NAFLD treatment. In combination with lifestyle modifications such as exercise and calorie restriction, TRF could play an essential role in the prevention of NAFLD in the future. However, further studies are needed to explore the long-term effects of TRF supplementation on NAFLD in children.

Trial registration

The study has been registered with the International Clinical Trial Registry under reference number (NCT05905185) retrospective registration on (15/06/2023).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12887-024-04993-8.

Keywords: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, Oxidative stress, Tocotrienols, Antioxidants, Anti-inflammatory agent

Background

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has emerged as a growing health concern in children worldwide, with its prevalence escalating alongside the rise in childhood obesity and associated metabolic risk factors [1]. The pathogenesis of pediatric NAFLD is unknown; however, it is likely to be a multifactorial, multistep, and progressive condition. Accumulation of free fatty acids and triglycerides in the liver cells causes damage, leading to inflammation, and cellular injury, biochemical and histological derangements seen in children with NAFLD [2]. This can trigger a cascade of events that can lead to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and liver failure [3, 4]. Alterations in gut microbiota, genetic predisposition, and environmental toxins are other variables that may be incorporated into the development of pediatric NAFLD.

Globally, the frequency of NAFLD in children is rising, and in the overall pediatric population, it is believed to be between 7 and 10% [5]. However, the incidence varies according to age groups, racial and cultural backgrounds, and geographic areas. In children who are overweight or obese, the prevalence of NAFLD is higher and is predicted to range from 34 to 76% [6]. Although there is a paucity of information on the incidence of NAFLD among Malaysian children, it is likely that the condition is becoming more common as a result of the country's rising rates of childhood obesity and bad lifestyle choices. The percentage of overweight children in Malaysia ranging from 5 to 19 years old was 12.7% in a survey conducted by the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) [7]. A study by Mohamed et al. (2020) investigated the prevalence and predictors of NAFLD among children with obesity in Malaysia. The study included 33 children ranging from 5.5 to 18.5 years who were diagnosed with obesity and underwent screening for NAFLD. They found that of the 33 patients, 21 (63.6%) had NAFLD. Several predictors of NAFLD were identified in this population, including age, waist circumference, body mass index (BMI), and high blood pressure [8]. It is crucial to highlight that this study focused on a obese children, and the prevalence of NAFLD in Malaysia's general pediatric population may differ.

Currently, the FDA has authorized a new drug, Rezdiffra (resmetirom) for the treatment of NAFLD. The drug's safety and efficacy in children NAFLD are still up for debate, and further research is needed to determine whether or not this medication can be used in paediatric populations as it is primarily intended for adult patients [9]. As with previous clinical guidelines, the main strategy for paediatric NAFLD is still lifestyle changes [10, 11]. A study by Ratziu et al. 2020 discussed the current understanding of the pathophysiology of NAFLD and NASH, including the role of oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and gut microbiota in the development and progression of these conditions [12]. Emerging therapies, such as GLP-1 receptor agonists and FXR agonists, are currently being evaluated in clinical trials [13]. Recent studies have suggested that vitamin E, an antioxidant-rich fat-soluble vitamin, is a potential therapy in pediatric NAFLD [14, 15]. The management of NAFLD was discussed by a panel of experts from the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) who also offer pharmacological treatments including vitamin E, pioglitazone, and GLP-1 receptor agonists as well as lifestyle strategies like diet and exercise [16]. Another randomized, placebo-controlled trial investigated the effects of supplementing δ-tocotrienol on biochemical markers of liver injury and steatosis in patients with NAFLD. In comparison to the placebo group, δ-tocotrienol supplementation improved the level of ALT, AST, hs-CRP and HOMA-IR levels [17]. The American Association of Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline offered suggestions and methods for controlling NAFLD in pediatric patients that were supported by research. These strategies include pharmacological methods like vitamin E and metformin, as well as lifestyle changes, including healthier eating along with increased exercise. The recommendation prioritizes recognizing and managing comorbid conditions, such as obesity and insulin resistance, which frequently accompany NAFLD [18]. This study aimed to investigate the supplementation of tocotrienol-rich fraction vitamin E (TRF) as part of the management of NAFLD among children with obesity in Malaysia.

Methods

Study design and patient recruitment

This is a randomized, single-blinded clinical trial involving children in the pediatric clinic at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre (UKMMC). The study has been registered with the International Clinical Trial Registry under reference number NCT05905185, retrospective registration on (15/06/2023). This study was approved by the institutional review board ([UKM PPI/111/8/JEP-2018621]. Informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from all participants. For participants who were younger than the age of 16, consent was obtained from their parents or legal guardians. We ensured that all ethical guidelines for conducting research with minors were strictly followed. A total number of 32 children between the ages of 10 and 18 who were overweight or obese (BMI between the 85th and 95th percentile for their age) were enrolled. This age range was selected because it includes the critical developmental period of late childhood and adolescence, during which it is most possible to study the onset and progression of NAFLD [19, 20]. Previous research has shown that the incidence of obesity and metabolic syndrome, which are critical risk factors for the development of NAFLD, is greater among children and adolescents aged 10 to 18 [21, 22]. The inclusion criteria included being able to swallow a small, soft gel capsule and an abdominal ultrasound confirmed the diagnosis of NAFLD. Also, a controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) score on the FibroScan must be > 263 dB/m, with an elevated alanine transaminase level of ≥ two-fold the upper limit (26 U/L for boys and 22 U/L for girls, respectively). We excluded subjects who had hepatitis C, hepatitis B, autoimmune hepatic disorders or primary chronic liver disease. Prior to the start of the trial, the children were instructed to avoid using any dietary supplements for at least four weeks. According to the Malaysian Clinical Practice Guidelines, the Children’s clinical parameters, such as their height, weight, waist circumference, and BMI was evaluated prior to the intervention [23]. All study parameters were measured before the intervention and again six months after. Patient interviews were done every two months to check on compliance. Using a computer model built on Microsoft Excel, the recruited patients were enrolled in the study and randomly assigned (1:1) to either the TRF treatment or the placebo group. The randomized procedure was carried out by the lead investigator because she knew the allocation order. The patients were given bottles containing either the TRF or placebo supplements following completion of all baseline assessments for both groups.

Treatment product and procedure

Sime Darby Oils Nutrition Sdn. Bhd. Malaysia supplied the TRF pills utilized in the study. Each TRF pill, containing 50 mg of vitamin E isomers, comprised 7.4 mg of δ-tocotrienol, 2.02 mg of β-tocotrienol, 22.3 mg of γ-tocotrienol, 18.28 mg of α-tocotrienol, and 17.1 mg of α-tocopherol. Over a six-month duration, participants were directed to ingest either the oral TRF (50 mg) or a placebo after meals. The children were advised to maintain their regular dietary habits, refrain from incorporating vitamin E-rich supplements, and also not to alter their exercise routines. After randomization, follow-up visits were made every eight weeks for the duration of the trial. Every two weeks, a telephone follow-up was conducted to check on the patient's health. At their initial visit, patients were given 10 bottles containing 10 capsules (either TRF or placebo) for two distinct sessions, along with instructions on how frequently to take the supplements, the patients were blinded to the contents of the bottles. There was no way to distinguish the placebo from the TRF pills based on how they tasted, smelled, or appearance because they were stored in similar bottles. The two bottles each had an A or B label. The participants were instructed to keep the pill sachets in dry conditions, out of the sun, at or below 25 °C. The pills’ shelf life was two years. Before and after the study's two-month session, pill counting was used to gauge the patient's compliance. The acceptable compliance rate was 85 to 100% [24].

Outcome measures

The primary result was the mean difference (dB/m) in hepatic steatosis as evaluated by the controlled attenuated parameter (CAP) after TRF supplementation versus placebo. Secondary outcomes were mean differences in biochemical blood tests, FibroScan fibrosis score, and LIVERFASt calculated scores for fibrosis, activity, steatosis, DNA damage, and pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ). Assessments were conducted on 29 participants (15 in the TRF group and 14 in the placebo group) at baseline and end of trial.

Evaluation of biochemical blood and liverFASt

LiverFASt, a non-biopsy method, produces an algorithm that correlates with the simple grading/staging of the NAFLD based on the three basic features of the disease which are: inflammation, fibrosis, and steatosis. To perform this test, the patients were instructed to fast overnight for at least eight hours before conducting the test. A series of blood tests were conducted that included total bilirubin, haptoglobin, apolipoprotein-A1 (ApoA1), fasting serum total cholesterol, fasting blood glucose, [25] and (ALT), alpha-2-macroglobulin (a2M), and fasting triglyceride levels, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) were measured. These measurements were utilized in the LiverFASt algorithm along with BMI, gender, and age to calculate the extent of the disease. These data were compared with liver stiffness measurements obtained by the FibroScan device in order to provide an objective diagnosis of hepatic steatosis, fibrosis, and inflammatory activity scores in NAFLD patients [26, 27].

FibroScan examination

Using FibroScan 502, data for liver stiffness measurement (LSM), a marker for liver fibrosis, and controlled attenuated parameter (CAP), an indicator of hepatic fat deposition, were obtained (Echosens, Paris, France). Liver stiffness of > 8 kPa indicates advanced fibrosis while CAP of > 263 indicates fatty liver [28]. The measurement was considered reliable if the interquartile range/median (IQR/M) was < 20% and the success reading rate of ≥ 70%. The procedure was carried out by a single, experienced operator to eliminate bias and inter-operator variability. The sizes of the patients were considered when calculating the probe and CAP values.

Comet assay

The comet assay was employed to quantify DNA damage in an alkaline environment. The slides were prepared according to Singh et al. [29]. The slides were observed with the epifluorescence microscope (Olympus BH-2 System), equipped with a DPlanApo 20 UV objective and an Olympus SPlan 10. The images were captured with the aid of the OpenComet v1.3.1 program that was installed on the computer. For each sample, 100 randomly chosen cells were examined (50 cells from each of the two replicate slides) [30, 31]. The degree of DNA damage was then measured based on the length and percentage of the tail DNA.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) of inflammatory cytokines

Total RNA was isolated from fresh blood samples using the RNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany). Using a Denovix spectrophotometer, the quantity and quality of the extracted RNA were determined by calculating its absorbance at 260 and 280 nm. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using the RT2 First Strand Kit (Qiagen, Germany). Quantitative PCR was carried out using the RT2 SYBR Green Mastermix (Qiagen, Germany) via the Bio-Rad CFX96 instrument [Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA]. The PCR conditions were set with the initial step at 95 °C for 15 s, followed by 60 °C for 1 min. Finally, the melting curve of the product gradient analysis was calculated at a rate of 0.5 °C/10 s, starting from 65 °C to 95 °C. The RT-qPCR assess the mRNA expression of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, TNF-α and IFN-γ (Qiagen, Germany). All analyses were done in triplicates after normalized with the housekeeping genes (GAPDH). The relative gene expression analysis was done by the 2–ΔΔCT method.

Sample size

According to Mofdi et al. (2017), the sample size was estimated based on the mean of hepatic steatosis, with a controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) score evaluated by FibroScan as the primary outcome. To calculate the proper sample size for detecting a difference between two independent samples, and based on the previous study's mean difference and standard deviation, the appropriate sample size for each arm should be 14 patients for each group, TRF and placebo. The sample size for each group has been determined to 16 patients per arm, taking into consideration 20% dropout and non-compliance [32].

Statistical analysis

The SPSS software ver. 20.0 from SPSS Inc. in Chicago, Illinois, USA, was used to analyze the data. Independent t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests and Wilcoxon Paired Rank Test or Paired t-tests were used to compare differences between pre-and post-intervention values in each group. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value of less than 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 32 patients were randomly assigned to either the placebo or TRF groups. Two patients withdrew from the trial; their excuse was that they were unable to attend follow-up appointments because of scheduling conflicts with their parents' jobs and academic exams. As a result, they did not get the intervention. One patient dropped out of the trial because their parents’ work obligations prevented them from attending the follow-up appointments. According to the consort diagram for patient recruitment, no patient reported issues with compliance during the 6-month intervention period due to TRF or placebo supplements adverse effects (Fig. 1). The baseline demographic information gathered from the patients is shown in Table 1. There was no statistically significant difference in baseline values between the two groups.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow diagram depicts how participants progressed through each stage of the randomized controlled trial, which used either tocotrienol-rich fraction vitamin E (TRF) or placebo

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at the baseline in tocotrienol-treated (TRF) and placebo group

| TRF (n = 15) | Placebo (n = 14) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 11.8 (2.1) | 12.5 (2.6) | 0.591 |

| BMI (Percentile)a | 99.5 (2.0) | 99.8 (0.7) | 0.400 |

| Fasting glucose, mmol/L | 4.6 (0.3) | 4.7(0.4) | 0.354 |

| ALT IU/L a | 29.0 (15) | 30.4(10.7) | 0425 |

| AST IU/L a | 30.0 (12) | 27.4(9.7) | 0.505 |

| Total Cholesterol mmol/L | 4.54(0.8) | 4.41(1.0) | 0.523 |

| APO-A1g/L | 1.39 (0.3) | 1.32(0.3) | 0.405 |

| GGT IU/La | 29 (20) | 27(20.7) | 0.652 |

| Haptoglobin g/L | 1.29 (0.5) | 1.40(0.5) | 0.235 |

| Total bilirubin µmol/La | 7.9 (2.1) | 7.7(3.1) | 0.476 |

| α-2-M g/L a | 2.38(0.3) | 2.46(0.4) | 0.780 |

| Triglycerides mmol/L a | 1.53(0.6) | 1.29(0.4) | 0.477 |

| Serum LiverFASt | |||

| Steatosis Scorea | 0.33 (0.2) | 0.39 (0.5) | 0.425 |

| Activity Scorea | 0.11 (0.1) | 0.12 (0.06) | 0.377 |

| Fibrosis Score | 0.13 (0.07) | 0.13 (0.04) | 0.902 |

| Transient elastography | |||

| CAP dB/m | 307.14(50.4) | 309.38(53.6) | 0.518 |

| Liver stiffness kPa | 4.85(1.17) | 4.58(1.07) | 0.201 |

Data are presented as the mean (SD)

ALT Alanine Aminotransferase, AST Aspartate Aminotransferase, APO-A1 Apolipoprotein A1, GGT Gamma-glutamyl transferase, α-2-M alpha-2-Macroglobulin, CAP Controlled Attenuation Parameter, BMI Body mass index

aData are presented as the median

Blood biochemical measurements

The biochemical tests demonstrated that patients who took TRF supplements daily for six months had significantly lower serum apolipoprotein- APO-A1 and aspartate aminotransferase AST levels than the baseline (P = 0.002) and (P = 0.038) respectively. Total cholesterol levels did not differ significantly post-TRF supplementation compared to the baseline. The level was, however, significantly higher in the placebo group (p < 0.05) when compared to the baseline after six months. However, no significant difference was observed in other serum biomarkers such as ALT, fasting blood glucose, α-2-M, GGT, haptoglobin, total bilirubin and triglycerides was seen at the end of the intervention for either group, as shown in (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparisons of the changes from baseline to endpoint of study outcomes of NAFLD patients

| TRF (n = 15) | Placebo (n = 14) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | After 6 months | p-value | Baseline | After 6 months | p-value | |

| BMI (Percentile)a | 99.5(2.0) | 99.7(0.9) | 0.859 | 99.8 (0.7) | 99.9(0.5) | 0.527 |

| Fasting glucose, mmol/L | 4.6 (0.3) | 4.8(0.8) | 0.156 | 4.7(0.4) | 4.8(0.6) | 0.591 |

| ALT IU/L a | 29.0(15) | 34.0(16) | 0.726 | 30.4(10.7) | 33.2(10.3) | 0.450 |

| AST IU/L a | 30.0(12) | 22.0(10) | 0.038* | 27.4(9.7) | 23.9(7.7) | 0.138 |

| Total Cholesterol,mmol/L | 4.54(0.8) | 4.59(0.9) | 0.670 | 4.41(1.0) | 4.70(0.9) | 0.021* |

| APO-A1g/L a | 1.39(0.3) | 1.22(0.2) | 0.002* | 1.32(0.3) | 1.22(0.2) | 0.077 |

| GGT U/L a | 29(20) | 32(19) | 0.975 | 27(20.7) | 21(30.5) | 0.345 |

| Haptoglobin g/L | 1.29(0.5) | 1.28(0.4) | 0.941 | 1.43(0.5) | 1.51(0.6) | 0.366 |

| Total bilirubin µmol/La | 7.9(2.1) | 7.2(5.7) | 0.156 | 7.7(3.1) | 8.6(2.6) | 0.370 |

| α-2-M g/L | 2.38(0.3) | 2.40(0.2) | 0.126 | 2.46(0.4) | 2.35(0.4) | 0.283 |

| Triglycerides mmol/L | 1.53(0.6) | 1.70(0.8) | 0.131 | 1.29(0.4) | 1.35(0.4) | 0.609 |

| Serum LiverFASt | ||||||

| Steatosis Score | 0.33 (0.2) S0 | 0.35(0.3) | 0.078 | 0.39(0.5) | 0.39(0.5) | 0.060 |

| Activity Score | 0.11 (0.1) A0 | 0.15(0.1) | 0.955 | 0.12(0.06) | 0.14(0.09) | 0.424 |

| Fibrosis Score | 0.13 (0.07) S0 | 0.18(0.1) | 0.094 | 0.13(0.04) | 0.14(0.04) | 0.31 |

| Transient elastography | ||||||

| CAP dB/m | 307.14(50.4) | 286.07(67.5) | 0.189 | 309.38(53.6) | 277.62(39.5) | 0.048* |

| Liver stiffness kPa a | 4.85(1.17) | 4.65(1.53) | 0.167 | 4.58(1.07) | 5.42(2.01) | 0.075 |

aData are presented as the median

LiverFASt scores

The LiverFASt test was used to determine three hepatic parameters, i.e., hepatic fibrosis, activity scores and liver steatosis. The test results showed that patients in the treatment group did not significantly improve in any parameters (i.e., fibrosis score: p = 0.094; activity score: p = 0.955; steatosis score: p = 0.078). Also, there was no improvement was noted in the placebo group (fibrosis score: p = 0.31; activity score: p = 0.424; steatosis score: p = 0.060) (Table 2).

Transient elastography

After six months of intervention, the hepatic steatosis score decreased from 307.14 ± 50.4 to 286.07 ± 67.5 db/m. Yet, it was not statistically significant. In comparison, after six months of intervention, the score in the placebo group decreased significantly from 309.38 ± 53.6 db/m to 277.62 ± 39.5 db/m (p = 0.048). There was no improvement in fibrosis score in the NAFLD group supplemented with TRF compared to the baseline (4.85 ± 1.17 kPa vs 4.65 ± 1.53 kPa; p = 0.167). After six months of intervention, however, there was a trend toward an increase in the fibrosis score in NAFLD supplemented with placebo (4.58 ± 1.07 kPa to 5.42 ± 2.01 kPa; p = 0.075) (Table 2).

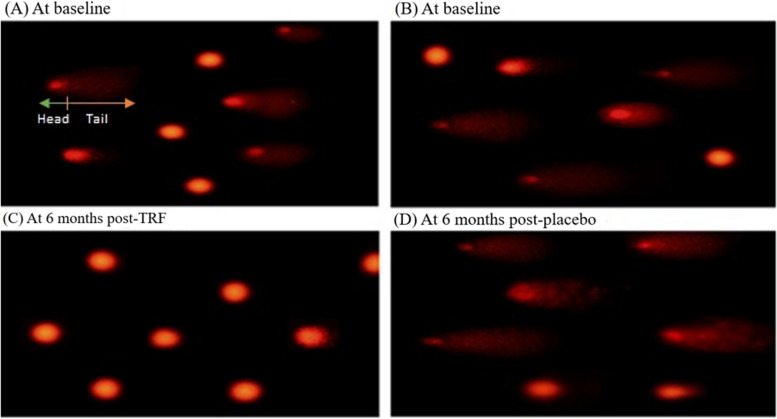

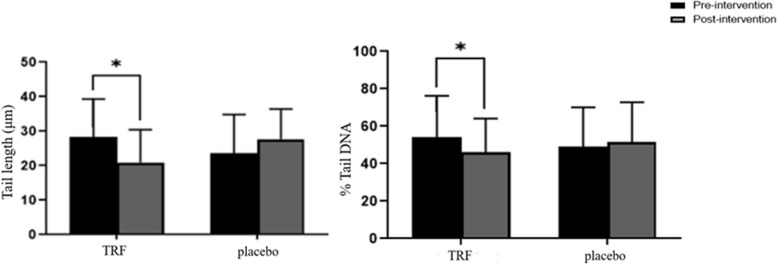

Comet assay analysis

Fluorescence microscopy was used to assess the DNA fragmentation following six months of intervention with either TRF or a placebo (Fig. 2A, B). Based on these results, the TRF group had less DNA damage than the control group, as shown by the reduced amount of stained comet tails (Fig. 2C). A high amount of stained comet tails, as seen in (Fig. 2 D), which suggests the placebo group experienced more DNA damage.

Fig. 2.

Alkaline single-cell gel electrophoresis was used to assess DNA damage. A Baseline TRF-treated group cells with DNA damage visible as comets. B Baseline placebo-treated group cells with DNA damage shown as comets. After six months, cells with TRF supplementation had less DNA damage. Cells with increased DNA damage following six months of placebo supplementation

The ImageJ software was used to analyze the comet and measure the DNA amount in the tail length (TL) and tail (% DNA) of the digital comet image. The results showed that after six months of the intervention, the mean tail length in the TRF group decreased significantly from 28.34 ± 10.9 to 21.6 ± 9.84 (p = 0.04), compared to the baseline. In the placebo group, however, the mean tail length increased from 23.67 ± 11.15 to 27.72 ± 8.7 (p = 0.19), yet this increase was not statistically significant. The percentage of tail DNA (% DNA) in the TRF group decreased significantly from 54.13 22.1 to 46.23 ± 17.9 (p 0.045), but not in the placebo group 48.56 ± 21.1 vs 51.78 ± 21.1 (p 0.48) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

DNA damage was determined using computerized image analysis for TRF and placebo at baseline and post-intervention. The comet assay method detected DNA damage in a whole blood sample by calculating the tail length (TL) and percentage of DNA in the tail (DNA%) of 100 randomly selected cells. A fluorescence microscope was used to examine the slide. ImageJ software was used to capture the photos and measure them. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, and a statistically significant value is deemed to be P < (0.05)

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Figure 4 shows the fold change in mRNA levels of inflammatory cytokines before and after TRF and placebo intervention. The TRF group showed significant downregulation in the IL-6 expression (p < 0.05). A comparable trend was noted for the TNF-α value in the TRF group, which showed significant downregulation of TNF-α gene expression after the intervention compared to the baseline values (p < 0.05). In both the pre and post-intervention TRF and placebo groups, the results indicated no significant difference in the IFN-γ expression.

Fig. 4.

Relative fold change of gene expression measured by quantitative real-time PCR for the vitamin E group & Placebo group at baseline and six months’ post-intervention. A Relative expression of IL-6 gene. B Relative expression of TNF-α. Relative expression of IFN-γ gene. Relative expression levels were normalised to GAPDH, and fold changes were calculated against the baseline. Values represent the means and SEM. Significant differences are highlighted as ∗ (P < 0.05)

Discussion

The aim of this study was to get more insight into the potential use of tocotrienol-rich fraction vitamin E (TRF) as a supplement in children with obesity who are suffering from non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Our study demonstrated that the TRF supplementation was safe and more effective as compared to the placebo after 24 weeks by significantly lowering apolipoprotein A1 and aspartate aminotransferase levels in children with obesity and NAFLD. The strength of this study lies in its comprehensive examination of inflammatory and oxidative stress markers, which provides robust evidence for the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant benefits of tocotrienols observed in our research. Our study showed that patients who received TRF supplementation had much less DNA damage in their blood samples based on the comet assay results. This test provides a relative measure of the number of DNA strand breaks. The substantial therapeutic advantages of TRF in NAFLD in children with obesity, particularly in cases of severe liver damage [11, 33]. This effect is likely due to TRF’s ability to act as an antioxidant by reducing oxidative damage. Additionally, Vitamin E may modulate mitochondrial biogenesis and regulate the production of superoxide and other reactive oxygen species [34] by influencing various mitochondrial enzymes and pathways. Vitamin E can enhance the activity of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD), an enzyme that converts superoxide radicals into less harmful molecules. It also helps to stabilize the inner mitochondrial membrane, thereby reducing electron leakage and subsequent ROS formation. These mechanisms collectively contribute to the reduction of oxidative stress within cells [35, 36].

Furthermore, it was also noted that the TRF supplementation decreased DNA damage in healthy subjects after 12 and 24 weeks of supplementation. This effect was greater in females and older individuals above the age of 50 [37]. When patients with hypercholesterolemia were given four progressively increasing dosages of tocotrienol-rich fraction derived from palm oil (TRF): 125 mg/day, 250 mg/day, 500 mg/day, and 750 mg/day over four weeks, this provided more evidence that tocotrienol could also function as an anti-inflammatory agent. There were significantly lower levels of serum nitric oxide [38], C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), malondialdehyde (MDA) and gamma glutamyl-transferase compared to the placebo group for all concentrations of TRF [39].

Oxidative stress plays a crucial role in the pathophysiology of NAFLD. Imbalances between the production of reactive oxygen species [34] and the body's antioxidant defense capacity can disrupt normal lipid metabolism, contributing to the onset and progression of NAFLD [40]. Excess fat accumulation in adipose tissue leads to the release of free fatty acids into the bloodstream. The liver receives these fatty acids via transport, where they are normally processed and stored as triglycerides. However, individuals with insulin resistance, often associated with obesity, face challenges in the liver's ability to efficiently metabolize and export these lipids. Consequently, fat builds up within the liver [41]. Imbalances in the gut microbiota composition can escalate the severity of NAFLD. This disruption has the capacity to enhance fatty acid synthesis in the gut, elevate small bowel permeability, and facilitate increased absorption of fatty acids into the bloodstream. These combined effects contribute to the overall accumulation of fat in the liver, further deteriorating the condition. Presently, there is no FDA-approved medication for the treatment of this disease in pediatric population [42]. The primary approach to manage NAFLD involves lifestyle modifications such as weight loss, regular exercise, and the adoption of a healthy diet [43]. In addition, vitamin E, a well-known fat-soluble antioxidant, is utilized as an alternative in the management of pediatric NAFLD with obesity [44].

The present study revealed no differences in blood biochemical parameters after TRF supplementation, including ALT, fasting blood glucose, α-2-M, GGT, haptoglobin, total bilirubin, and triglycerides. A meta-analysis in 2020 of nine randomized controlled studies similarly indicated that vitamin E failed to show any reduction in biochemical tests such as ALT, GGT, and TG[45]. Furthermore, several other factors should be considered, including therapy dosage, average patient age, sample size, gender distribution, duration of the intervention, research location, and dietary patterns. Individual variability, including genetic factors, diet, lifestyle, and NAFLD severity, also influences how liver enzymes respond to TRF and vitamin E supplementation [46, 47]. A 96-week randomized controlled trial comparing the effects of 800 IU vitamin E and 1000 mg metformin on pediatric NAFLD found that neither vitamin E nor metformin outperformed placebo in terms of ALT levels. Lack of significant changes could be explained by the particular patient cohort or the characteristics of the therapies. This emphasizes the necessity for alternate therapeutic approaches, such as TRF, that may possess different mechanisms of action or efficacy profiles [48]. Magosso et al. (2013) conducted a clinical trial in 87 patients suffering from mild untreated hypercholesterolemic with NAFLD using a mixture of vitamin E (61.5 mg of α-tocotrienol, 112.8 mg of γ-tocotrienol, and 25.7 mg of δ-tocotrienol and 61.1 mg of α-tocopherol), taken twice a day for 12 months. The tocotrienol-treated group significantly outperformed the placebo groups in terms of normalization of the hepatic echogenic response. However, as the study did not include a pediatric population, there may be less direct relevance between the results and our investigation [49]. According to a study conducted by Murer et al. (2014), antioxidant supplementation decreased oxidative stress and stabilized liver function tests in children with NAFLD. The study enrolled 90 participants aged 8 to 17 years’ old who were randomly assigned to receive either an antioxidant supplement containing vitamin C (500 mg), alpha-tocopherol (400 IU), and selenium (50 mg) or a placebo for 12 weeks. One of its key advantages is that it focuses on a paediatric population similar to ours, and the findings are relevant to our study [50].

It is important to keep in mind that the dosage and duration of vitamin E supplementation may also influence its effectiveness. We employed 50 mg/kg TRF for six months as the intervention in the present study. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial study, 80 adolescents with biopsy-proven NAFLD received a lower dosage of vitamin E (10 mg) combined with 7.5 mg of hydroxytyrosol for a shorter duration (16 weeks). They examined the impacts of antioxidant supplementation on oxidative stress, liver function, and inflammation. The trial included 80 participants ranging in age from 4 to 16 years. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either two capsules containing vitamin E plus hydroxytyrosol or a placebo. The study demonstrated enhanced insulin resistance, reduced steatosis, and improved oxidative stress markers in children with NAFLD [51].

The genetic variants associated with NAFLD in children were revealed in a review that was published in 2019, emphasizing the importance of genes involved in lipid metabolism, inflammation, and insulin resistance. They hypothesized that investigating these genes could aid in discovering new treatment targets for NAFLD. Non-invasive diagnostic modalities, such as imaging techniques and biomarkers, emphasize the importance of accurate and non-invasive tools for detecting and monitoring of NAFLD in children [52]. This study employed the LiverFASt and FibroScan tests to detect hepatic steatosis, fibrosis, and activity scores for assessment of liver steatosis in children, as previously reported [53]. There was no significant improvement in the degree and grade of hepatic steatosis observed in the tocotrienol group after six months of the intervention in this study. This suggests that the reduction in intrahepatic fat may not have been significant enough to bring about a visible improvement in the radiological grade of hepatic steatosis. This finding is supported by a clinical study conducted by Pervez et al. in 2018, which revealed that δ-tocotrienol supplementation significantly decreased high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, malondialdehyde, and aminotransferase levels in NAFLD patients but not hepatic steatosis on ultrasound examination. The trial also emphasized the safety of tocotrienol administration because no negative effects were observed. This study provides a solid foundation and additional validation for the therapeutic potential of tocotrienol in managing conditions related to oxidative stress, and the consistency between studies highlights the dependability and relevance of our results [54].

A meta-analysis was conducted to investigate the impact of vitamin E supplementation on aminotransferase levels in adults and children. Interestingly, no significant decrease in aminotransferase levels was found, particularly in the pediatric age group [55]. Another meta-analysis of 15 RCTs involving NAFLD patients of various ages found that the group receiving vitamin E had a significant drop in ALT and AST levels among adults following short-, intermediate-, and long-term follow-ups. The findings of the study suggested that a significant change in biochemical markers in children occurred after 12 months [56]. Furthermore, increased ALT serum levels correlate with NAFLD activity score, liver triglyceride, and fasting insulin, establishing it as a reliable predictor of NAFLD [57]. In a randomized placebo-controlled trial involving 86 participants, Bril et al. (2019) revealed that vitamin E (tocopherol) administration did not significantly improve hepatic steatosis compared to the placebo group [58]. This could be explained by a short study period or an inadequate dosage of vitamin E administration, however keep in mind that high dosages of this vitamin especially tocopherol, may have unfavorable effects, including bleeding and an increased risk of prostate cancer especially in adults [59].

Surprisingly, after the intervention in the present study, the CAP scores in the placebo group significantly decreased. The suggested etiology of the placebo effect included patients in the placebo arms changing their behavior in response to their knowledge of being observed [60]. This phenomenon, known as the Hawthorne effect, typically causes patients' BMIs to fall with time. In the current study, the BMI of the individuals in the placebo group, however, remained the same.

In a rat model of NAFLD, the effect of tocotrienol on inflammatory response and oxidative stress was examined [61]. They discovered that tocotrienol was able to regulate the inflammatory response and reduce oxidative stress in rats with NAFLD. These findings offer more details on tocotrienol's possible application in the treatment of NAFLD [61]. Since NAFLD is linked to the accumulation of DNA damage, changes in the genetic material encoding proteins related to repair pathways may contribute to the development of the disease. This is particularly relevant when considering the intricate relationship between oxidative stress, DNA repair, and liver steatosis. One important factor that may be important in the development of NAFLD is the impairment of DNA repair mechanisms [62].

Tocotrienols have been well-established, and promising research has demonstrated that it has anti-inflammatory properties [63]. In comparison to the placebo group, TRF supplementation for 24 weeks reduced the expression of IL-6 and TNF-α in children with obesity with NAFLD in the current study. This finding was verified by an in vivo study that found γ-that tocotrienol supplementation reduced adipose tissue inflammation in mice fed a high-fat diet by lowering the production of cytokines and chemokines that promote inflammation. Additionally, γ-tocotrienol supplementation reduced the recruitment of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages in adipose tissue [64]. It was proven that tocotrienol can reduce inflammation in NAFLD in a double-blinded, active-controlled experiment utilizing 300 mg δ-tocotrienol daily for 48 weeks by significantly lowering serum IL-6 and TNF-α [65]. Inflammation induced by TNF-α in differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes exposed to various concentration of γ-tocotrienol (0.024—2.4 µM) for 6 h showed a significant reduction in the expression of MCP-1 and IL-6 [66].

There were limitations in this study that could have an impact on the outcomes and should be mentioned to create chances for improvement in future research endeavors. This study exhibits a limited sample size, and conducting a larger-scale study could mitigate the risk of random findings, offering more robust evidence regarding the efficacy of supplementation. Additionally, our study has inherent limitations, including a single-dose administration, which may impact the generalizability and comprehensiveness of the results. The use of a single dosing approach might not fully capture the broad spectrum of responses or account for variations that could arise under different dosing regimens. The duration of supplementation could impact the robustness of the findings. A longer duration might provide a more thorough comprehension of the impacts of the supplementation over time. The absence of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in this study is a notable limitation, as TDM is crucial for ensuring optimal therapeutic levels, adjusting dosages based on individual responses, and monitoring potential fluctuations in drug concentrations over time. It is important to highlight that the experiment was limited to a single health center, and the majority of participants were Malays. Therefore, the conclusions regarding the role of vitamin E could not fully reflect the views of the larger Malaysian population. Another study limitation was that we did not measure other oxidative stress markers such as glutathione (GSH), glutathione peroxidase (GPX), catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and malondialdehyde (MDA).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that children with obesity and having NAFLD receiving tocotrienol-rich vitamin E supplements at a dose of 50 mg/day experienced no side effects, indicating that these supplements are typically safe and well tolerated. Evidence of its effectiveness throughout the course of the six-month study included improvements in serum apolipoprotein-A1, aspartate aminotransferase levels, decreased DNA damage, and low expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. These findings offer preliminary support for the superiority of tocotrienol fraction of vitamin E as an adjuvant therapy in the medical management of pediatric NAFLD.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Sime Darby Oil Nutrition Sdn. Bhd. (FF-2020-180) and Fundamental Research Grant, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (FF-2020-180/1) and to all specialists and medical officers of the Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Center.

Authors’ contributions

N.M.M designed, give technical advice, writing an original draft preparation and data analysis, F.D.R. conducted the experiments and analyzing the data, N.M.M., and R.A.R.A supervised the study, K.N.M. involved in sample collection, and conducted FibroScan. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Sime Darby Oil Nutrition Sdn. Bhd. and Research University Grant, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (project code: FF-2020–180 and FF-2021–180/1).

Availability of data and materials

All supporting data this study is included in the paper.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia ethics committee [UKM PPI/111/8/JEP-2018621]. Informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from all participants. For participants who were younger than the age of 16, consent was obtained from their parents or legal guardians.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors hereby declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Marcinkiewicz K, Horodnicka-Józwa A, Jackowski T, Strączek K, Biczysko-Mokosa A, Walczak M, Petriczko E. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children with obesity–observations from one clinical centre in the Western Pomerania region. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13: 992264. 10.3389/fendo.2022.992264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phen C, Ramirez CM. Hepatic steatosis in the pediatric population: an overview of pathophysiology, genetics, and diagnostic workup. Clin Liver Dis. 2021;17(3):191. 10.1002/cld.1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng L, Wu S, Zhou N, Zhu S, Liu Q, Li X. Clinical characteristics and risk factors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children with obesity. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):1–8. 10.1186/s12887-021-02595-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ranucci G, Spagnuolo MI, Iorio R. Obese children with fatty liver: between reality and disease mongering. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(47): 8277. 10.3748/wjg.v23.i47.8277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J, Ren W. Diagnosis and therapeutic strategies for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children. Zhonghua gan Zang Bing za zhi= Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi= Chinese. J Hepatol. 2020;28(3):208–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mann JP, Valenti L, Scorletti E, Byrne CD, Nobili V: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children. In: Seminars in liver disease: 2018: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2018: 001–013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children 2019. Children, Food and Nutrition: Growing well in a changing world. New York: UNICEF; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohamed RZ, Jalaludin MY, Zaini AA. Predictors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) among children with obesity. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2020;33(2):247–53. 10.1515/jpem-2019-0403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison SA, Taub R, Neff GW, Lucas KJ, Labriola D, Moussa SE, Alkhouri N, Bashir MR. Resmetirom for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Nat Med. 2023;29(11):2919–28. 10.1038/s41591-023-02603-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldner D, Lavine JE. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children: unique considerations and challenges. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(7):1967–83 e1961. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Baiaty FD, Ismail A, Abdul Latiff Z, Muhammad Nawawi KN, Raja Ali RA, Mokhtar NM. Possible hepatoprotective effect of tocotrienol-rich fraction vitamin E in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obese children and adolescents. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:667247. 10.3389/fped.2021.667247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ratziu V, Friedman SL. Why do so many NASH trials fail? Gastroenterology. 2020;S0016–5085(0020):30680. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nevola R, Epifani R, Imbriani S, Tortorella G, Aprea C, Galiero R, Rinaldi L, Marfella R, Sasso FC. GLP-1 receptor agonists in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: current evidence and future perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(2): 1703. 10.3390/ijms24021703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perumpail BJ, Li AA, John N, Sallam S, Shah ND, Kwong W, Cholankeril G, Kim D, Ahmed A. The role of vitamin E in the treatment of NAFLD. Diseases. 2018;6(4): 86. 10.3390/diseases6040086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alberti G, Gana JC, Santos JL. Fructose, Omega 3 Fatty Acids, and Vitamin E: Involvement in Pediatric Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Nutrients. 2020;12(11): 3531. 10.3390/nu12113531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Charlton M, Cusi K, Rinella M, Harrison SA, Brunt EM, Sanyal AJ. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):328–57. 10.1002/hep.29367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pervez MA, Khan DA, Slehria AUR, Ijaz A. Delta-tocotrienol supplementation improves biochemical markers of hepatocellular injury and steatosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2020;52: 102494. 10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cusi K, Isaacs S, Barb D, Basu R, Caprio S, Garvey WT, Kashyap S, Mechanick JI, Mouzaki M, Nadolsky K. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in primary care and endocrinology clinical settings: co-sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD). Endocr Pract. 2022;28(5):528–62. 10.1016/j.eprac.2022.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elizabeth LY, Schwimmer JB. Epidemiology of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clinical Liver Disease. 2021;17(3):196–9. 10.1002/cld.1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harlow KE, Africa JA, Wells A, Belt PH, Behling CA, Jain AK, Molleston JP, Newton KP, Rosenthal P, Vos MB. Clinically actionable hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Pediatr. 2018;198(76–83): e72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gama A, Rosado-Marques V, Machado-Rodrigues AM, Nogueira H, Mourao I, Padez C. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in 3-to-10-year-old children: assessment of different cut-off criteria WHO-IOTF. An Acad Bras Ciênc. 2020;92: e20190449. 10.1590/0001-3765202020190449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ene-Obong H, Ibeanu V, Onuoha N, Ejekwu A. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and thinness among urban school-aged children and adolescents in southern Nigeria. Food Nutr Bull. 2012;33(4):242–50. 10.1177/156482651203300404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ismail IS, Bebakar W, Kamaruddin N, Abdullah N, Zin F, Taib S. Clinical practice guidelines on management of obesity. Putrajaya: Ministry of Health Malaysia, Academy of Medicine of Malaysia, Malaysian Association for the Study of Obesity, Malaysian Endocrine and Metabolic Society; 2004.

- 24.Baumgartner PC, Haynes RB, Hersberger KE, Arnet I. A systematic review of medication adherence thresholds dependent of clinical outcomes. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9: 1290. 10.3389/fphar.2018.01290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castro-Mejia JL, Khakimov B, Krych L, Bulow J, Bechshoft RL, Hojfeldt G, Mertz KH, Garne ES, Schacht SR, Ahmad HF, et al. Physical fitness in community-dwelling older adults is linked to dietary intake, gut microbiota, and metabolomic signatures. Aging Cell. 2020;19(3): e13105. 10.1111/acel.13105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boursier J, Guillaume M, Leroy V, Irlès M, Roux M, Lannes A, Foucher J, Zuberbuhler F, Delabaudière C, Barthelon J. New sequential combinations of non-invasive fibrosis tests provide an accurate diagnosis of advanced fibrosis in NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2019;71(2):389–96. 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vali Y, Lee J, Boursier J, Spijker R, Verheij J, Brosnan MJ, Anstee QM, Bossuyt PM, Zafarmand MH, Team LSR. FibroTest for evaluating fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2021;10(11): 2415. 10.3390/jcm10112415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan WK, Nik Mustapha NR, Mahadeva S. Controlled attenuation parameter for the detection and quantification of hepatic steatosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29(7):1470–6. 10.1111/jgh.12557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh NP, McCoy MT, Tice RR, Schneider EL. A simple technique for quantitation of low levels of DNA damage in individual cells. Exp Cell Res. 1988;175(1):184–91. 10.1016/0014-4827(88)90265-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bankoglu EE, Seyfried F, Arnold C, Soliman A, Jurowich C, Germer CT, Otto C, Stopper H. Reduction of DNA damage in peripheral lymphocytes of obese patients after bariatric surgery-mediated weight loss. Mutagenesis. 2018;33(1):61–7. 10.1093/mutage/gex040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magenis ML, Damiani AP, de Marcos PS, de Pieri E, de Souza E, Vilela TC, de Andrade VM. Fructose consumption during pregnancy and lactation causes DNA damage and biochemical changes in female mice. Mutagenesis. 2020;35(2):179–87. 10.1093/mutage/geaa001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mofidi F, Poustchi H, Yari Z, Nourinayyer B, Merat S, Sharafkhah M, Malekzadeh R, Hekmatdoost A. Synbiotic supplementation in lean patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a pilot, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. Br J Nutr. 2017;117(5):662–8. 10.1017/S0007114517000204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao L, Fang X, Marshall MR, Chung S. Regulation of obesity and metabolic complications by gamma and delta tocotrienols. Molecules. 2016;21(3):344. 10.3390/molecules21030344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anhe FF, Roy D, Pilon G, Dudonne S, Matamoros S, Varin TV, Garofalo C, Moine Q, Desjardins Y, Levy E, et al. A polyphenol-rich cranberry extract protects from diet-induced obesity, insulin resistance and intestinal inflammation in association with increased Akkermansia spp. population in the gut microbiota of mice. Gut. 2015;64(6):872–83. 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Napolitano G, Fasciolo G, Di Meo S, Venditti P. Vitamin E supplementation and mitochondria in experimental and functional hyperthyroidism: a mini-review. Nutrients. 2019;11(12): 2900. 10.3390/nu11122900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.J Majima H, P Indo H, Suenaga S, Matsui H, Yen HC, Ozawa T. Mitochondria as possible pharmaceutical targets for the effects of vitamin E and its homologues in oxidative stress-related diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(21):2190-2195. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Goon JA, Azman NHEN, Ghani SMA, Hamid Z, Ngah WZW. Comparing palm oil tocotrienol rich fraction with α-tocopherol supplementation on oxidative stress in healthy older adults. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2017;21:1–12. 10.1016/j.clnesp.2017.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, Le Paslier D, Yamada T, Mende DR, Fernandes GR, Tap J, Bruls T, Batto JM, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011;473(7346):174–80. 10.1038/nature09944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qureshi A, Khan D, Mahjabeen W, Trias A, Silswal N, Qureshi N. Impact of δ-tocotrienol on inflammatory biomarkers and oxidative stress in hypercholesterolemic subjects. J Clin Exp Cardiolog. 2015;6(367):2. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Godoy-Matos AF, Júnior WSS, Valerio CM. NAFLD as a continuum: from obesity to metabolic syndrome and diabetes. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2020;12(1):1–20. 10.1186/s13098-020-00570-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Samuel VT, Shulman GI. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease as a nexus of metabolic and hepatic diseases. Cell Metab. 2018;27(1):22–41. 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J, Zou B, Yeo YH, Feng Y, Xie X, Lee DH, Fujii H, Wu Y, Kam LY, Ji F. Prevalence, incidence, and outcome of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Asia, 1999–2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4(5):389–98. 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30039-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller EF. Nutrition management strategies for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: treatment and prevention. Clin Liver Dis. 2020;15(4):144. 10.1002/cld.918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hadi HE, Vettor R, Rossato M. Vitamin E as a treatment for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: reality or myth? Antioxidants. 2018;7(1):12. 10.3390/antiox7010012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin M, Zeng H, Deng G, Lei J, Li J. Vitamin E in paediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2021;45(3): 101530. 10.1016/j.clinre.2020.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmölz L, Birringer M, Lorkowski S, Wallert M. Complexity of vitamin E metabolism. World J Biol Chem. 2016;7(1):14. 10.4331/wjbc.v7.i1.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Civelek M, Podszun MC. Genetic factors associated with response to vitamin E treatment in NAFLD. Antioxidants. 2022;11(7): 1284. 10.3390/antiox11071284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lavine JE, Schwimmer JB, Van Natta ML, Molleston JP, Murray KF, Rosenthal P, Abrams SH, Scheimann AO, Sanyal AJ, Chalasani N. Effect of vitamin E or metformin for treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adolescents: the TONIC randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(16):1659–68. 10.1001/jama.2011.520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Magosso E, Ansari MA, Gopalan Y, Shuaib IL, Wong J-W, Khan NAK, Abu Bakar MR, Ng B-H, Yuen K-H. Tocotrienols for normalisation of hepatic echogenic response in nonalcoholic fatty liver: a randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nutr J. 2013;12(1):1–8. 10.1186/1475-2891-12-166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murer SB, Aeberli I, Braegger CP, Gittermann M, Hersberger M, Leonard SW, Taylor AW, Traber MG, Zimmermann MB. Antioxidant supplements reduced oxidative stress and stabilized liver function tests but did not reduce inflammation in a randomized controlled trial in obese children and adolescents. J Nutr. 2014;144(2):193–201. 10.3945/jn.113.185561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nobili V, Alisi A, Mosca A, Crudele A, Zaffina S, Denaro M, Smeriglio A, Trombetta D. The antioxidant effects of hydroxytyrosol and vitamin E on pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, in a clinical trial: a new treatment? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2019;31(2):127–33. 10.1089/ars.2018.7704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nobili V, Alisi A, Valenti L, Miele L, Feldstein AE, Alkhouri N. NAFLD in children: new genes, new diagnostic modalities and new drugs. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(9):517–30. 10.1038/s41575-019-0169-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ferraioli G, Calcaterra V, Lissandrin R, Guazzotti M, Maiocchi L, Tinelli C, De Silvestri A, Regalbuto C, Pelizzo G, Larizza D. Noninvasive assessment of liver steatosis in children: the clinical value of controlled attenuation parameter. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17(1):1–9. 10.1186/s12876-017-0617-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pervez MA, Khan DA, Ijaz A, Khan S. Effects of delta-tocotrienol supplementation on liver enzymes, inflammation, oxidative stress and hepatic steatosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2018;29(2):170. 10.5152/tjg.2018.17297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Amanullah I, Khan YH, Anwar I, Gulzar A, Mallhi TH, Raja AA. Effect of vitamin E in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Postgrad Med J. 2019;95(1129):601–11. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2018-136364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abdel-Maboud M, Menshawy A, Menshawy E, Emara A, Alshandidy M, Eid M. The efficacy of vitamin E in reducing non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2020;13:1756284820974917. 10.1177/1756284820974917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martin-Rodriguez JL, Gonzalez-Cantero J, Gonzalez-Cantero A, Arrebola JP, Gonzalez-Calvin JL. Diagnostic accuracy of serum alanine aminotransferase as biomarker for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and insulin resistance in healthy subjects, using 3T MR spectroscopy. Medicine. 2017;96(17):e6770. 10.1097/MD.0000000000006770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bril F, Biernacki DM, Kalavalapalli S, Lomonaco R, Subbarayan SK, Lai J, Tio F, Suman A, Orsak BK, Hecht J. Role of vitamin E for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(8):1481–8. 10.2337/dc19-0167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Klein EA, Thompson IM, Tangen CM, Crowley JJ, Lucia MS, Goodman PJ, Minasian LM, Ford LG, Parnes HL, Gaziano JM, et al. Vitamin E and the Risk of Prostate Cancer: The Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA. 2011;306(14):1549–56. 10.1001/jama.2011.1437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Han MAT, Altayar O, Hamdeh S, Takyar V, Rotman Y, Etzion O, Lefebvre E, Safadi R, Ratziu V, Prokop LJ. Rates of and factors associated with placebo response in trials of pharmacotherapies for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(4):616–29 e626. 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wong SK, Chin K-Y, Ahmad F, Ima-Nirwana S. Regulation of inflammatory response and oxidative stress by tocotrienol in a rat model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Functional Foods. 2020;74: 104209. 10.1016/j.jff.2020.104209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ziółkowska S, Kosmalski M, Kołodziej Ł, Jabłkowska A, Szemraj JZ, Pietras T, Jabłkowski M, Czarny PL. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in base-excision repair-related genes involved in the risk of an occurrence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(14): 11307. 10.3390/ijms241411307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Trujillo M, Kharbanda A, Corley C, Simmons P, Allen AR. Tocotrienols as an anti-breast cancer agent. Antioxidants. 2021;10(9): 1383. 10.3390/antiox10091383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao L, Kang I, Fang X, Wang W, Lee MA, Hollins RR, Marshall MR, Chung S. Gamma-tocotrienol attenuates high-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance by inhibiting adipose inflammation and M1 macrophage recruitment. Int J Obes (Lond). 2015;39(3):438–46. 10.1038/ijo.2014.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pervez MA, Khan DA, Mirza SA, Slehria AUR, Nisar U, Aamir M. Comparison of delta-tocotrienol and alpha-tocopherol effects on hepatic steatosis and inflammatory biomarkers in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized double-blind active-controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2022;70: 102866. 10.1016/j.ctim.2022.102866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matsunaga T, Shoji A, Gu N, Joo E, Li S, Adachi T, Yamazaki H, Yasuda K, Kondoh T, Tsuda K. γ-Tocotrienol attenuates TNF-α-induced changes in secretion and gene expression of MCP-1, IL-6 and adiponectin in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol Med Rep. 2012;5(4):905–9. 10.3892/mmr.2012.770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All supporting data this study is included in the paper.