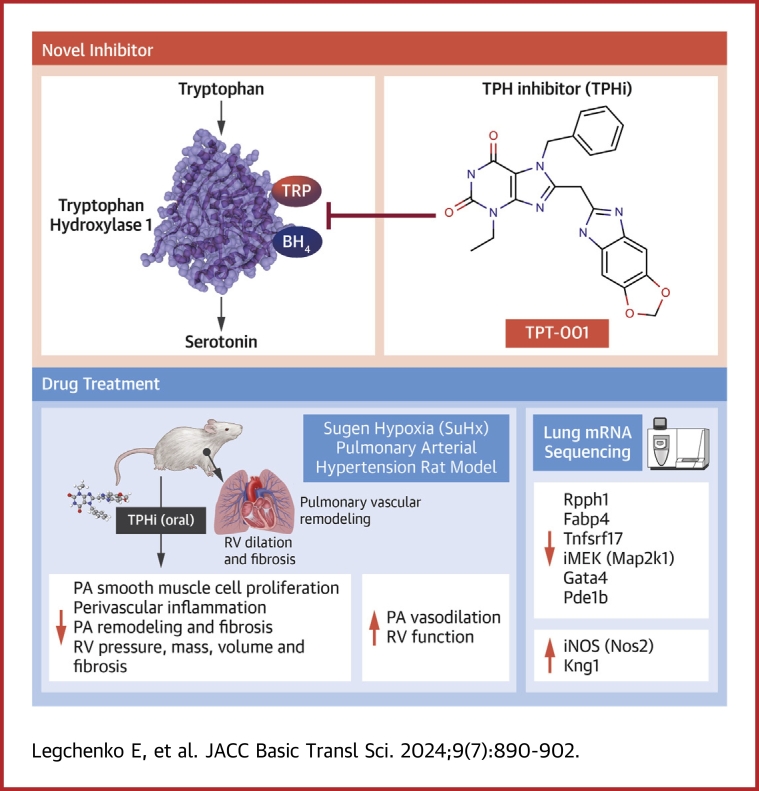

Visual Abstract

Key Words: drug discovery, pulmonary arterial hypertension, serotonin, tryptophan hydroxylase inhibitor

Highlights

-

•

Peripheral serotonin, synthesized by the enzyme TPH1, is a pathogenic factor in PAH.

-

•

Oral TPT-001, a novel class drug of TPHi, reverses severe PAH and prevents associated RV dysfunction in the clinically relevant SuHx rat model of PAH.

-

•

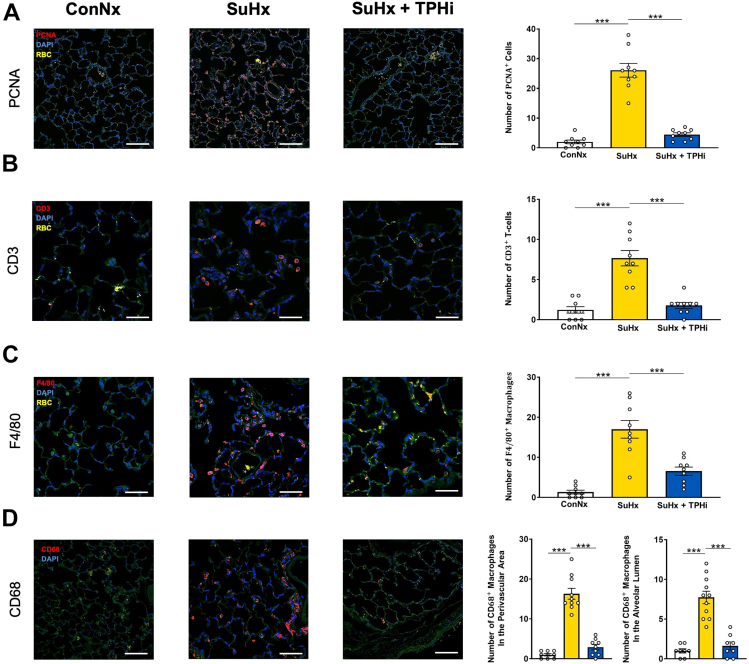

TPT-001 suppresses perivascular infiltration of CD3+ T cells, proinflammatory F4/80+/CD68+ macrophages, and PCNA+ alveolar epithelial cells, found in the SuHx PAH rat lung.

-

•

Lung mRNA-sequencing unraveled distinct gene expression patterns in SuHx-rat lungs related to PASMC proliferation, reactive oxygen species, inflammation, and vasodilation, all of which are beneficially affected by the oral TPH1-inhibitor TPT-001.

-

•

TPH1 inhibitors are promising options for oral or inhalative treatment of PAH, and should be studied in clinical trials.

Summary

The serotonin pathway has long been proposed as a promising target for pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)—a progressive and uncurable disease. We developed a highly specific inhibitor of the serotonin synthesizing enzyme tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1), TPT-001 (TPHi). In this study, the authors sought to treat severe PAH in the Sugen/hypoxia (SuHx) rat model with the oral TPHi TPT-001. Male Sprague Dawley rats were divided into 3 groups: 1) ConNx, control animals; 2) SuHx, injected subcutaneously with SU5416 and exposed to chronic hypoxia for 3 weeks, followed by 6 weeks in room air; and 3) SuHx+TPHi, SuHx animals treated orally with TPHi for 5 weeks. Closed-chest right- and left heart catheterization and echocardiography were performed. Lungs were subject to histologic and mRNA sequencing analyses. Compared with SuHx-exposed rats, which developed severe PAH and right ventricular (RV) dysfunction, TPHi-treated SuHx rats had greatly lowered RV systolic (mean ± SEM: 41 ± 2.3 mm Hg vs 86 ± 6.5 mm Hg; P < 0.001) and end-diastolic (mean ± SEM: 4 ± 0.7 mm Hg vs 14 ± 1.7 mm Hg; P < 0.001) pressures, decreased RV hypertrophy and dilation (all not significantly different from control rats), and reversed pulmonary vascular remodeling. We identified perivascular infiltration of CD3+ T cells and proinflammatory F4/80+ and CD68+ macrophages and proliferating cell nuclear antigen–positive alveolar epithelial cells all suppressed by TPHi treatment. Whole-lung mRNA sequencing in SuHx rats showed distinct gene expression patterns related to pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell proliferation (Rpph1, Lgals3, Gata4), reactive oxygen species, inflammation (Tnfsrf17, iNOS), and vasodilation (Pde1b, Kng1), which reversed expression with TPHi treatment. Inhibition of TPH1 with a new class of drugs (here, TPT-001) has the potential to attenuate or even reverse severe PAH and associated RV dysfunction in vivo by blocking the serotonin pathway.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a rapidly progressive condition with a poor prognosis and currently no cure.1 The pathobiology of the underlying pulmonary vascular disease (PVD) is multifactorial, encompassing altered cellular and systemic glucose and lipid metabolism and heightened proliferation of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) along with inflammation, endothelial cell apoptosis, and vasoconstriction. These cellular and molecular changes lead to an increase in pulmonary vascular resistance and right ventricular (RV) pressure afterload, heart failure, and death.2,3 Both the incidence and the prevalence of PAH are increasing worldwide,4, 5, 6 and the available treatment options remain very limited. Despite a recent introduction of new efficient drugs, such as riociguat,7 selexipag,8 and, most recently, sotatercept,9 it has not been shown in clinical trials that long-term transplant-free survival improves with PAH-targeted pharmacotherapy.

Serotonin has long been suspected to be a potential therapeutic target in PAH. Increased serotonin plasma levels were found in PAH patients,10 and serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been associated with persistent pulmonary hypertension (PH) of the newborn.11 Serotonin is one of the neurotransmitters in the central nervous system, but it is unable to cross the blood-brain barrier and is produced separately in the central nervous system and peripherally. The main production source of serotonin is in the gastrointestinal tract, where it is then absorbed by platelets, but it also originates from other places, such as the lungs, immune cells, and blood vessels.12 The serotonin hypothesis of PH gained more support with the identification of drug-induced etiology of PAH in patients who took appetite suppressors, ie, drugs such as amphetamine, fenfluramine, and aminoxaphen, that induce serotonin release (as reviewed by MacLean et al13).

The rate-limiting step in serotonin synthesis is catalyzed by tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH). TPH has 2 isoforms: TPH1, associated with the peripheral synthesis of serotonin, mainly in the gut, and TPH2, involved in the central nervous synthesis of serotonin.14,15 Both in preclinical models of PH and in PAH patients, TPH1 expression in pulmonary endothelial cells has been shown to be increased.16,17 Further studies suggested that the use of pharmacologic inhibitors of TPH1 (TPHis) and its genetic manipulation may protect from or ameliorate already established experimental PH.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 With the current shortage and continuous search for new classes of PAH-targeted medications, the interest in using pharmacologic TPHis in the clinical setting has risen.24,25

Recently, we successfully developed a new class of TPHis that are unable to pass the blood-brain barrier, thus remaining and acting in the periphery. We demonstrated that these new TPHis are superior in their TPH1-inhibiting properties compared with telotristat etiprate, a clinically approved TPHi, and that they also quench serotonin formation in vitro and in vivo in mice.26

Here, we report the successful treatment of progressive angio-obliterative PAH in the Sugen/hypoxia (SuHx) rat model with the new TPHi, TPT-001 (formerly called KM-05-166) (Supplemental Figure 1). Five weeks of oral treatment with TPT-001 reversed PAH and PVD and prevented heart failure in SuHx-exposed rats. By means of comprehensive pulmonary mRNA sequencing analysis, we created potential mechanistic networks that can explain how the inhibition of TPH1 exerts beneficial effects in severe PAH.

Methods

Animal studies

All animal experiments were conducted under the approval of the Niedersächsisches Landesamt für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit (Lower Saxony, Germany; no. 15/2022).

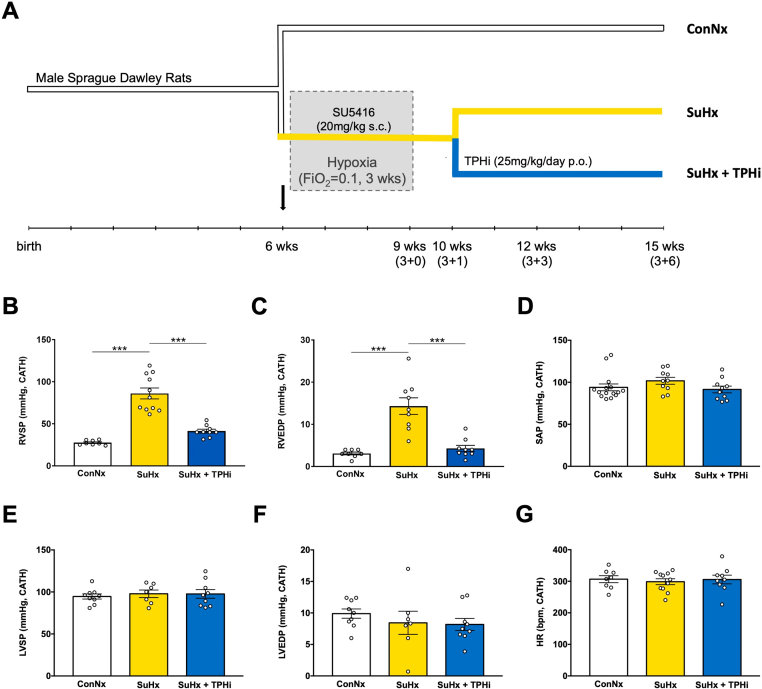

SuHx rat PAH model

As previously described by our group,27 male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing ∼180 to 200 g were purchased from Charles River and divided into 3 groups, according to the experimental design (Figure 1A): 1) control normoxia (ConNx); 2) Sugen/hypoxia (SuHx), ie, rats injected subcutaneously with the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 inhibitor SU5416 (Sigma), 20 mg/kg/dose dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide, and subsequently exposed to chronic hypoxia for 3 weeks, followed by 6 weeks of room air, and 3) Sugen/hypoxia–exposed rats treated orally with TPH inhibitor TPT-001 (SuHx+TPHi), 25 mg/kg/day incorporated into the diet, starting 1 week after the end of chronic hypoxia (recovery), for 5 weeks. We had previously reported that SuHx rats 1 week after the end of 3 weeks hypoxia have PAH, but no RV failure yet.27

Figure 1.

TPHi Attenuates Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in the SuHx Rat Model: Invasive Hemodynamic Measurements

(A) Experimental design. Three age-matched groups: 1) control (ConNx); 2) SuHx (injected with SU5416, 20 mg/kg per dose, subcutaneous, and then exposed to hypoxia for 3 weeks, followed by 6 weeks of room air); and 3) SuHx+TPHi (treated orally with TPHi [TPT-001, 25 mg/kg /day] for 5 weeks). (B to G) Invasive hemodynamic measurements performed 6 weeks after the end of hypoxia to assess the right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP), right ventricular end-diastolic pressure (RVEDP), systolic blood pressure (SAP), left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP), left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP), and heart rate (HR). Mean ± SEM, n = 7-11, ANOVA–Bonferroni post hoc test. ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

Drug incorporation

TPT-001 was incorporated into the regular diet (Altromin 1324), based on an estimated food intake of 30 g/day.

Statistics

Values from multiple experiments are expressed as mean ± SEM. The normality of data distributions was tested by means of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

For multiple comparisons, statistical significance was determined using one-way analysis of variance followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test for multiple pairwise comparisons unless stated otherwise. Student’s 2-tailed t-test was applied for comparisons of 2 groups. A significance level of 0.05 was used in all tests. The size of each group is indicated in the legends.

Sample size was determined as reported previously.27 In the study we used 45 male Sprague-Dawley rats: ConNx n = 15; SuHx: n = 17; and SuHx+TPHi: n = 11.

The animals were arbitrarily randomized at the beginning of the experiment into the control group and the group receiving SU5416/hypoxia. One week after hypoxia, randomly picked animals from the second group received TPHi orally.

Extended methods text are provided in the Supplemental Appendix.

Results

Oral application of TPT-001 reverses severe PAH in the SuHx rat

To determine whether pharmacologic inhibition of TPH1 would reverse severe PAH, we orally administered the TPHi TPT-001 (25 mg/kg/day) to hypertensive SuHx rats starting 1 week after hypoxia (Figure 1A). We had previously reported that SuHx rats 1 week after the end of 3 weeks hypoxia have PAH, but no RV failure yet. In the present study, after 5 subsequent weeks of oral treatment with TPT-001, SuHx-exposed rats had decreased right ventricular systolic (RVSP) and diastolic (RVEDP) pressures compared with untreated SuHx-exposed rats (41.35 ± 2.34 mm Hg vs 86.12 ± 6.46 mm Hg [P = 0.001] and 4.28 ± 0.73 mm Hg vs 13.53 ± 1.68 mm Hg [P = 0.001], respectively); RVSP and RVEDP in treated animals were not significantly different from healthy control animals (who were not exposed to SuHx; P = 0.17 and P > 0.99, respectively) (Figures 1B and 1C). The systemic arterial pressure (Figure 1D), LV systolic pressure, and LV end-diastolic pressure were not significantly different among the 3 groups (Figures 1E and 1F, Table 1), indicating the absence of LV diastolic dysfunction and any postcapillary component contributing PA pressure elevation. Heart rate (Figure 1G), LV mass, and LV dimensions were very similar among the 3 groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Invasive Hemodynamic (Cardiac Catheterization, Closed Chest Technique) and Echocardiographic Measurements in Male Sprague-Dawley Rats 6 Weeks After the End of 3 Weeks of Hypoxia (SuHx PAH Rat Model)

| ConNx | SuHx | SuHx+TPHi | Significance | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive hemodynamics (cardiac catheterization) | |||||

| Body weight, g | 529.8 ± 8.7 | 481.5 ± 10.4 | 482.4 ± 12.0a | SuHx vs ConNxb SuHx+TPHi vs ConNxa |

11-17 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 306 ± 11 | 299 ± 9 | 306 ± 14 | ns | 8-11 |

| RVSP, mm Hg | 27.58 ± 0.99 | 86.12 ± 6.46 | 41.35 ± 2.34 | SuHx vs ConNxc SuHx vs SuHx+TPHic |

8-11 |

| RVEDP, mm Hg | 3.09 ± 0.33 | 13.53 ± 1.68 | 4.28 ± 0.73 | SuHx vs ConNxc SuHx vs SuHx+TPHic |

8-11 |

| RV dp/dt max, mm Hg/s | 1,485 ± 124 | 2,989 ± 262 | 1,905 ± 199 | SuHx vs ConNxc SuHx vs SuHx+TPHib |

8-11 |

| RV dp/dt min, mm Hg/s | −1,177 ± 86 | −2,399 ± 272 | −1,663 ± 140 | SuHx vs ConNxc SuHx vs SuHx+TPHia |

8-11 |

| Systolic BP, aorta, mm Hg | 93.9 ± 4.1 | 101.8 ± 4.1 | 91.5 ± 4.0 | ns | 10-15 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 59.2 ± 3.4 | 70.4 ± 4.0 | 63.2 ± 4.4 | ns | 10-15 |

| LVEDP, mm Hg | 9.9 ± 0.7 | 8.4 ± 1.8 | 8.2 ± 1.0 | ns | 7-9 |

| Echocardiography | |||||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 322 ± 7 | 318 ± 9 | 312 ± 10 | ns | 7-14 |

| PAAT, ms | 32.55 ± 1.98 | 17.39 ± 0.71 | 25.20 ± 1.45 | SuHx vs ConNxc SuHx vs SuHx+TPHib |

7-14 |

| PAET, ms | 76.71 ± 3.28 | 83.03 ± 2.18 | 83.89 ± 1.76 | ns | 7-14 |

| PAAT/PAET | 0.42 ± 0.02 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.30 ± 0.02 | SuHx vs ConNxc SuHx vs SuHx+TPHia |

7-14 |

| RVEDD, mm | 2.32 ± 0.07 | 3.80 ± 0.18 | 2.83 ± 0.30 | SuHx vs ConNxc SuHx vs SuHx+TPHib |

7-14 |

| RVAWD, mm | 0.89 ± 0.04 | 1.75 ± 0.06 | 1.28 ± 0.10 | SuHx vs ConNxc | 7-14 |

| LVEDD, mm | 6.87 ± 0.22 | 7.50 ± 0.30 | 7.42 ± 0.13 | ns | 7-14 |

| LVEDS, mm | 3.83 ± 0.07 | 4.23 ± 0.15 | 4.11 ± 0.19 | ns | 7-14 |

| LVPWD, mm | 2.06 ± 0.17 | 2.08 ± 0.13 | 2.35 ± 0.14 | ns | 7-14 |

Values are mean ± SEM and compared by means of ANOVA–Bonferroni post hoc test. For experimental design, see Figure 1. Clarification regarding animal numbers: The right heart catheterization sets are complete (RVSP, RVEDP, RV dp/dt). The LV catheter was performed in the same animals as well as in the dedicated subset of animals. In some animals we could insert the catheter into the carotid artery to record systolic arterial pressure, but not retrograde into the LV; therefore, the number for systolic and diastolic arterial pressure is higher than for LVSP and LVEDP.

BP = blood pressure; dp/dt max = maximal rate of pressure development (systolic RV function); dp/dt min = maximal rate of pressure decay (diastolic RV function); LVEDD = left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEDP = left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; LVEDS = left ventricular end-systolic diameter; LVPWD = left ventricular posterior wall thickness in diastole; PAAT = pulmonary artery acceleration time; PAET = pulmonary artery ejection time; RV = right ventricular; RVAWD = right ventricular anterior wall thickness; RVEDD = right ventricular end-diastolic diameter; RVEDP = right ventricular end-diastolic pressure; RVSP = right ventricular systolic pressure.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

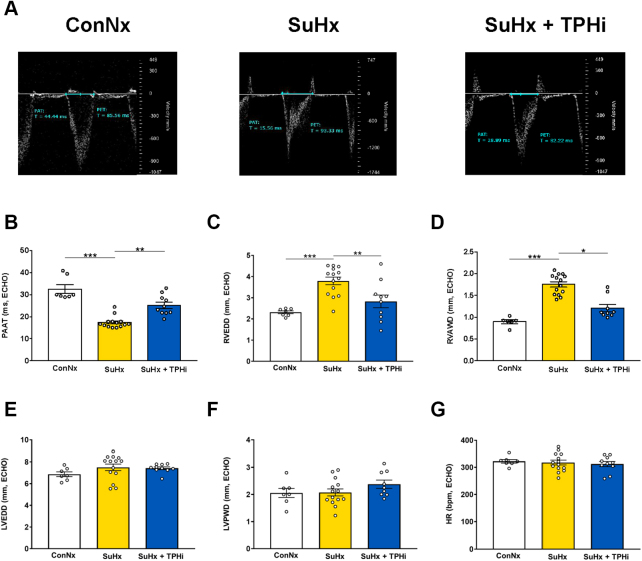

Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated restoration of pulmonary artery acceleration time (an inverse surrogate of PA pressure and pulmonary vascular resistance) (Figures 2A and 2B) and right heart dimensions (RV end-diastolic wall thickness and diameter) (Figures 2C and 2D) in TPHi-treated vs untreated SuHx-exposed rats without the left side being affected (Figures 2E to 2G). TPHi treatment decreased RV mass, that is, RV hypertrophy (RV anterior wall thickness 1.28 ± 0.1 mm vs 1.75 ± 0.06 mm; P = 0.021) (Figure 2D), and prevented RV dilation (RV end-diastolic diameter 2.83 ± 0.30 mm vs 3.80 ± 0.18 mm; P = 0.001) (Figure 2C), that is, besides the demonstrated elevation of RV filling pressures (RVEDP), another surrogate for RV failure in rats several weeks after SuHx exposure. Taken together, our invasive and noninvasive in vivo data suggest that the novel TPH inhibitor TPT-001, when given orally over 5 weeks, reversed PAH/PVD and prevented RV failure in SuHx-exposed rats.

Figure 2.

TPHi Attenuates Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in the SuHx Rat Model: Noninvasive Echocardiographic Measurements

(A) Representative pulsed-wave Doppler images for pulmonary artery acceleration time (PAAT) measurement in the 3 groups at the end of the study. The SuHx group has a mid-systolic notch, which is no longer present in the group treated with TPHi. (B to G) PAAT as a surrogate of mean pulmonary arterial pressure and pulmonary vascular resistance, RV end-diastolic diameter (RVEDD) and end-diastolic anterior wall thickness (RVAWD), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) and end-diastolic posterior wall thickness (LVPWD), and heart rate (HR). Mean ± SEM, n = 7-14, ANOVA–Bonferroni post hoc test. ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

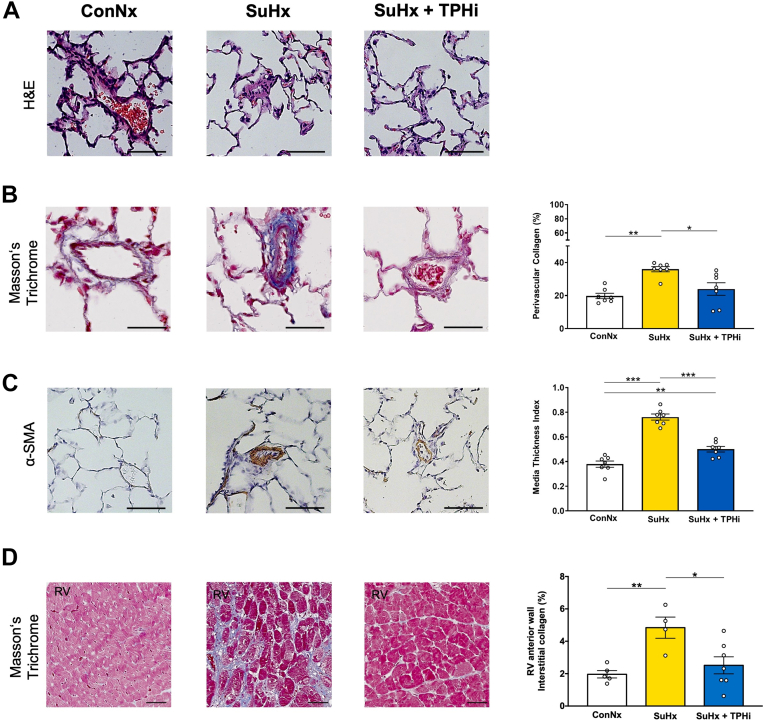

TPT-001 suppresses pulmonary vascular remodeling and cardiac fibrosis

To estimate the impact of oral TPH1 inhibition on the lung vasculature, we performed histologic assessment of serial lung sections. The SuHx-exposed rats exhibited an increase in the perivascular collagen deposition as assessed by Masson’s Trichrome staining (Figure 3B). These animals also showed prominent medial hypertrophy and lumen narrowing in peripheral (small) pulmonary arteries (Figure 3C). The heart histology demonstrated that the SuHx-exposed rats had heightened percentage of interstitial fibrosis in the RV free wall (Figure 3D). All these characteristics of PAH pathology were largely reversed in SuHx-exposed rats receiving oral TPT-001 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

TPHi Attenuates Muscularization of Small Pulmonary Arteries and Cardiac Fibrosis in the SuHx Rat Model

(A to C) Representative images of small peripheral pulmonary arteries in hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Masson’s Trichrome, and α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) staining, respectively. Scale bars: 25 μm. Bar graphs: (B) percentage of perivascular collagen. n = 20-40 vessels per animal; n = 7-8 animals. (C): Peripheral pulmonary artery muscularization. n = 20-40 vessels per animal; n = 7-8 animals. (D) Masson’s Trichrome staining of interstitial collagen in RV tissue. n = 4-7 individual animals. Mean ± SEM, ANOVA–Bonferroni post hoc test. ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

Compartmental signals in rat SuHx-PAH lungs and their reversal with TPHi treatment

To get insights into the compartmental distribution of proliferative and proinflammatory protein expression in the lungs of SuHx-PAH rats, and the according signal changes with TPHi (TPT-001) treatment, we performed immunofluorescence staining of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded sections. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen had a strong expression pattern in alveolar epithelial cells of SuHx rats (Figure 4A). Moreover, we identified alveolar septal and perivascular lung infiltration of CD3+ T cells (Figure 4B), and F4/80+ and CD68+ macrophages (Figures 4C and 4D) in SuHx rats with severe PAH. Intriguingly, this proliferative and proinflammatory marker expression (T cells, macrophages) was reversed and suppressed to control level in TPHi-treated SuHx-exposed rats (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Immunofluorescent Evaluation of Key Targets in the Rat Lung

(A) Representative photographs showing proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) staining. PCNA signal in red, 6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) in blue, and red blood cells in yellow, quantification to the right. (B) Representative photographs showing accumulation of CD3+ T cells in the lungs of SuHx animals, which is not present in the treated group. CD3 signal in red, DAPI in blue, and red blood cells in yellow, quantification to the right. (C and D) Representative photographs showing accumulation of F4/80+ and CD68+ macrophages in the lung of SuHx animals, which is absent after the treatment. CD68 signal in red, DAPI in blue, quantification to the right. Mean ± SEM, ANOVA–Bonferroni post hoc test. ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

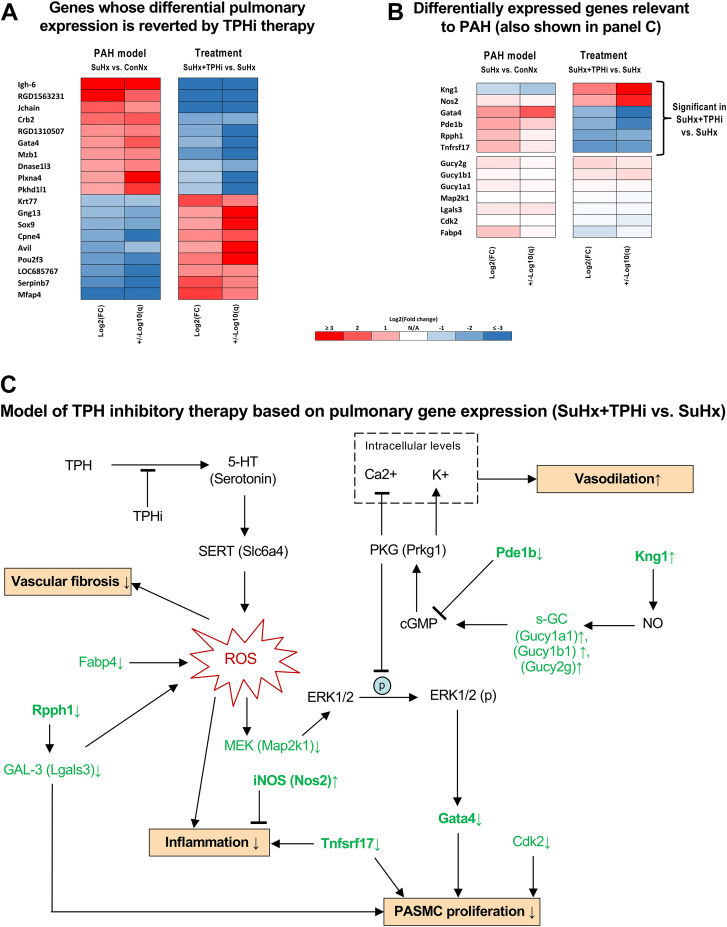

Oral TPH inhibition reverses PAH-associated gene expression in SuHx-exposed rat lungs

To understand the mechanisms by which TPHi exerted its beneficial properties on the vasculature, we performed mRNA sequencing in freshly frozen rat lungs. Gene expression analysis identified 112 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), 76 up-regulated and 36 down-regulated, in the PAH model comparison (SuHx [n = 6] vs ConNx [n = 4]) (Supplemental Table SD1). Treatment comparison (SuHx+TPHi [n = 4] vs SuHx [n = 6]) (Supplemental Table SD2) generated 142 DEGs (61 up-regulated and 81 down-regulated). Interestingly, 34 of the PAH model DEGs (25 up-regulated and 9 down-regulated) reversed their expression after the TPHi treatment (SuHx+TPHi vs SuHx), that is, up-regulated DEGs became down-regulated and vice versa (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Gene Expression Analysis (RNA-seq) of Rat Whole Lung Samples Reveals Key DEGs Likely Contributing to Beneficial Effects of TPHi Therapy

(A) Heatmap of DEGs whose differential expression was reverted by the TPHi therapy. These DEGs are likely involved in biological processes mediated by serotonin signaling and associated with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH); however, the roles of many of these genes remain unclear. (B) Heatmap of selected treatment DEGs (SuHx+TPHi vs SuHx) and their corresponding expression in the PAH model (SuHx vs ConNx). The selection is relevant to PAH based on the literature. (C) Proposed model of TPHi therapy based on observed gene expression (RNA-seq, no additional validation) indicates likely beneficial effects, ie, decrease in: 1) vasoconstriction; 2) pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell (PASMC) proliferation; 3) vascular fibrosis; and 4) inflammation. Targets indicated in bold were significantly differentially expressed (false discovery rate <0.05 and fold changes >2 or <0.5). The arrows next to targets indicate the observed up-regulation (↑) or down-regulation (↓). The arrows and T-bars in the models indicate the effects (induction or suppression, respectively) known from the literature. The arrows next to biological processes (↑ or ↓) follow from the observed regulation of the upstream targets. Sample sizes: ConNx, n = 4; SuHx, n = 6; SuHx+TPHi, n = 4. 5-HT = 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin); cGMP = cyclic guanosine monophosphate; ConNx = control group in normoxia; Hx = hypoxia; NO = nitric oxide; PKG = protein kinase G; ROS = reactive oxygen species; SuHx = Sugen 5416 in hypoxia; TPH, tryptophan hydroxylase.

Some of these genes (Gata4, Dnase1l3, Plxna4, Mfap4, and Sox9) are known to be involved in pathways relevant to PAH (Figure 5). These and other potentially PAH relevant genes are shown in Figure 5B, which is based on TPHi treatment DEGs and the matching PAH model genes (not necessarily differentially expressed). The key DEGs likely conferring beneficial effects associated with the TPHi treatment are indicated in bold in Figure 5C (up-regulated: Kng1 and Nos2; down-regulated: Pde1b, Rpph1, Gata4, and Tnfsrf17).

Discussion

In this study we hypothesized that the novel TPHi TPT-001 is a potent treatment option of severe PAH in vivo, based on its selectivity, chemical properties, and inability to cross the blood-brain barrier.26 We had previously performed comprehensive phenotyping of the progressive SuHx PAH rat model and showed that 1 week after chronic hypoxia the animals have severe PAH but no early heart failure (which develops within 5 weeks), indicating the appropriate time window to start pharmacotherapy.27 Here, we demonstrate that the drug TPT-001, of the new class of TPHis,20 when given orally over 5 weeks, successfully reversed progressive PAH and prevented RV failure in the most accepted SuHx PAH rat model. On the tissue and cellular level, we could show that TPH inhibition impaired the hypermuscularization of peripheral (small) pulmonary arteries and inhibited cardiac fibrosis. We then unraveled the distinct gene expression profiles in the lungs of SuHx-exposed rats that reversed their expression pattern with TPHi treatment.

Initially, TPHis were developed and successfully passed phases 1-3 clinical trials for treating carcinoid syndrome, with telostristat etiprate being approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in early 2017.28 The drug design for TPHis, however, remains challenging: producing nonselective inhibitors without the capacity to cross the blood-brain barrier, or synthesizing highly specific TPHis,29 the latter being nearly impossible until recently, when a new allosteric binding site of TPH1 was discovered.30 Of note, the published TPHi rodatristat (KAR5585) at a dose of 100 mg/kg per day administered as monotherapy had no significant effect on pulmonary hemodynamics in the SuHx PAH rat model (mean pulmonary arterial pressure 40.7 mm Hg in SuHx+KAR5585 vs 43.3 mm Hg SuHx+vehicle; and pulmonary pulse pressure 48.6 mm Hg in SuHx+KAR5585 vs 45.7 mm Hg SuHx+vehicle; not significant).23 Moreover, KAR5585 at 100 mg/kg/day had only small effects on the relative pulmonary vessel wall thickness (0.381 SuHx+KAR5585 vs 0.467 SuHx+vehicle; P < 0.001).23 Only at a very high oral dose of 200 mg/kg/day was KAR5585 associated with slightly lower mean pulmonary arterial pressure (37.8 vs 48.2 mm Hg, P < 0.05), lower RV mass (RV/[LV + septum] ratio 0.47 vs 0.61; P < 0.001), and decreased relative vessel wall thickness (26.4% vs 47.0%, P < 0.01).23 Nevertheless, the ELEVATE2 clinical trial (NCT04712669) for KAR5585 enrolled WHO group 1 PH (ie, PAH) patients in functional classes 2 and 3, but as of February 2024 the results have not been made public.

The TPHi TPT-001, which we tested in the present study, has a novel mechanism of action, a high inhibitory efficacy, and no toxic effects.26 In contrast to the study by Aiello et al23 of KAR5585, oral TPT-001 treatment in our SuHx PAH rat study, compared with disease control rats, greatly decreased RVSP, a surrogate of PA pressure and PAH severity (41 mm Hg vs 86 mm Hg), lowered RVEDP, an indicator of diastolic RV dysfunction (4.3 vs 14.3 mm Hg), reduced RV mass, that is, RV hypertrophy (RV arterial wall thickness), and prevented RV dilation and RV failure. Indeed, our data suggest that oral TPT-001 given over 5 weeks reversed PAH/PVD and prevented RV failure in SuHx-exposed rats.

An extended discussion on the role of serotonin transporter and the clinical role of appetite-suppressing drugs (amphetamines) in the pathobiology of PAH is provided in the Supplemental Appendix.

Most recently, the selective and systemically restricted serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine 2B; 5-HT2B) partial agonist VU6047534 has been developed and applied in a SuHx PAH mouse model.31 VU6047534 moderately decreased RVSP (from ∼40 to 25 mm Hg), RV mass, peripheral PA muscularization, and vessel loss in SuHx-exposed mice.31 Blocking 5-HT2B signaling with antagonists in the heritable mouse model of PAH (bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2 [BMPR2] mutation) prevented increased RVSP, microvessel muscularization, and Src tyrosine signaling.32

Early experimental evidence suggesting that serotonin was implicated in PAH development in vivo also came from a BMPR2-deficient mouse study: Heterozygous null BMPR2+/− mice developed moderate PH in response to hypoxia in combination with serotonin infusions.33 Additional studies showed that genetic depletion of TPH1/serotonin protects mice from experimental PH.19, 20, 21,23

One possible mechanism by which pharmacologic TPH inhibition exerts its beneficial effects is the induction of the antiproliferative transcription factor peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) in PASMCs. We have previously demonstrated in several in vivo and in vitro models that PPARγ activation (ie, nuclear shuttling/DNA binding)—downstream of clinically highly important BMP2/BMPR234 or other pathways—inhibits SMC proliferation, reverses pulmonary arterial hypertension,34,35 and prevents right heart failure.27 Indeed, serotonin (5-HT) dose- and time-dependently decreased PPARγ protein expression in PASMCs and promoted their proliferation (as approximated by bromodeoxyuridine incorporation).36 Further elucidation of the according interactions and molecular mechanisms is needed.

Overall, from the therapeutic perspective, the pleiotropic actions of serotonin in the pathogenesis of PAH impedes the future use of drugs inhibiting only 1 5-HT receptor, or SERT, serotonin transporter, and favors the approach of serotonin reduction itself as therapeutic goal.29

Our analysis of DEGs induced by the TPHi pharmacotherapy in lungs of SuHx-exposed rats revealed several targets potentially mediating multiple PAH-associated biological processes (Figure 5). In particular, TPH1 inhibition and the resulting reduction in 5-HT signaling likely decreased reactive oxygen species (ROS)–associated Erk1/2–Gata4 signaling, which is known to drive PASMC proliferation,37,38 as corroborated by down-regulation of Mek (Map2k1) and Gata4 in our data. Interestingly, we observed a trend to down-regulation of Fabp4 in SuHx+TPHi vs SuHx lungs. Fabp4 is known to increase ROS and inflammation in murine and cell models of acute lung injury.39 Therefore, down-regulated Fabp4 would also likely contribute to the aforementioned ROS/Erk/Gata4–mediated inhibition of PASMC proliferation.

Moreover, several TPHi treatment DEGs in our data suggested induction of the nitric oxide (NO)/soluble guanylate cyclase (s-GC)/cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)/cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) axis conferring its beneficial effects via: 1) disruption of ERK1/2 phosphorylation38 and subsequent Gata4-induced PASMC proliferation (as discussed above); and 2) PKG-mediated vasodilation (suppression of Ca2+ and induction of K+ intracellular levels).40 In particular, our data suggest an increased synthesis of NO, corroborated by the observed up-regulation of kininogen (Kng1)41 and nonsignificant up-regulation of several subunits of the downstream s-GC: Gucy1a1, Gucy1b1, and Gucy2g. Because s-GC is a precursor of cGMP, we can expect boosted cGMP/PKG signaling. Moreover, down-regulation of Pde1b, an enzyme known to hydrolyze cGMP,42 further corroborates the increased cGMP/PKG signaling and the subsequent induction of vasodilation and disruption of proproliferative ERK1/2 pathway. In this respect, TPT-001 mimics the effect of the s-GC activator riociguat, which is already approved for the treatment of PAH.43

A long noncoding RNA, Rpph1, was reported to induce galectin-3 in mesangial cells, which further induced cell proliferation and inflammation.44 Galectin-3 is a biomarker of PAH and PAH severity45 that is known for its role in maladaptive pulmonary vascular remodeling via induction of ROS and the associated inflammation and vascular fibrosis, for example, in a monocrotaline model of PAH.46, 47, 48 In our TPHi treatment data, Rpph1 was significantly down-regulated and likely induced down-regulation of galectin-3.

Several tumor necrosis factor (TNF) ligand family receptors, including Tnfrsf17, were reported to be up-regulated in a rat monocrotaline model of PAH.49 In human kidney cell lines, Tnfsrf17 was shown to induce cell proliferation and proinflammatory signaling.50 Therefore, down-regulation of Tnfsrf17 by the TPHi treatment in our study likely confers beneficial effects (reduction of PASMC proliferation and suppression of proinflammatory signaling).

Interestingly, Nos2, a gene coding for inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) tended to be up-regulated in PAH and was significantly up-regulated with TPHi treatment (Figure 4B). Although iNOS can interfere with vasodilatory endothelial NOS by competing for the NO precursor l-arginine,51 its primary role is in modulation of inflammatory signaling.52 In particular, iNOS appears to play a proresolving role by negative regulation of proinflammatory M1 macrophage polarization, inhibition of production of interleukin (IL)-12 in macrophages, negative regulation of TH17 differentiation, down-regulation of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12, and IL-23 in dendritic cells (DCs), and thus suppression of effector DCs in favor of regulatory DCs (as reviewed by Xue et al52).

Study limitations

In this drug discovery study, we investigated the organismal effects of a novel TPHi in the established preclinical SuHx rat model of PAH, but the precise in-depth mechanism of TPHi action in vivo remains to be elucidated. To this end, we have explored quantitative lung vascular histology and the mRNA signaling networks associated with the treatment effect by means of bulk lung mRNA sequencing. Deeper phenotyping could be achieved by single-cell or single-nuclear sequencing of the lungs and the heart may be studied ex vivo after TPHi treatment in an isolated RV pressure overload model, such as PA banding. Whether other routes of TPHi drug application, such as aerosol or dry powder inhalation, may be safe and efficient should be investigated in future studies.

Conclusions

Taken together, this study suggests that inhibition of TPH1 with a new class of drugs has the potential to effectively treat severe PAH in vivo, even in the progressive PAH SuHx rat model, via blocking of the serotonin pathway.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: PAH is a debilitating disease with unmet medical need, with no cure other than lung transplantation and limited long-term perspective. Inhibition of tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1) with a new class of drugs (here, oral TPT-001) reverses severe PAH and prevents associated RV dysfunction in vivo by blocking the serotonin pathway. Perivascular infiltration of CD3+ T cells and proinflammatory F4/80+ and CD68+ macrophages, and PCNA+ alveolar epithelial cells occurs in the SuHx PAH rat model and was suppressed by TPHi treatment. Whole-lung mRNA sequencing showed distinct gene expression patterns in SuHx rat lungs related to PASMC proliferation, ROS, inflammation, and vasodilation, all of which were beneficially affected by oral treatment with TPH1 inhibitor TPT-001.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK: Additional research is needed to delineate the optimal route of application, target dose, and pulmonary hypertension group that may benefit the most from TPH1 inhibitor treatment. Our results lay the groundwork for exploratory clinical studies on the use of oral or parenteral TPH1 inhibitors for PAH patients.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

This study was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (01KC2001B and 03VP08053 to Dr Hansmann; 01KC2001A, 03VP08051, and 16GW0298 to Dr Bader). Dr Hansmann also receives funding from the German Research Foundation (DFG KFO311 grant HA4348/6-2) and the European Pediatric Pulmonary Vascular Disease Network. Dr Nazaré has received funding from the Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs (ZIM grant 16KN073251). Drs Specker, Nazaré, Matthes, and Bader hold patents on the novel class of TPHi. Drs Specker, Wesolowski, and Bader are founders of Trypto Therapeutics GmbH. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For supplemental methods, discussion, references, tables, and a figure, please see the online version of this paper.

Appendix

References

- 1.Humbert M., Kovacs G., Hoeper M.M., et al. 2022 ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:3618–3731. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansmann G. Pulmonary hypertension in infants, children, and young adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:2551–2569. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Humbert M., Guignabert C., Bonnet S., et al. Pathology and pathobiology of pulmonary hypertension: state of the art and research perspectives. Eur Respir J. 2019;53 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01887-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wickremasinghe A.C., Rogers E.E., Piecuch R.E., et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes following two different treatment approaches (early ligation and selective ligation) for patent ductus arteriosus. J Pediatr. 2012;161:1065–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.05.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swinnen K., Quarck R., Godinas L., Belge C., Delcroix M. Learning from registries in pulmonary arterial hypertension: pitfalls and recommendations. Eur Respir Rev. 2019;28 doi: 10.1183/16000617.0050-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasan B., Hansmann G., Budts W., et al. Challenges and special aspects of pulmonary hypertension in middle- to low-income regions: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2463–2477. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghofrani H.A., Simonneau G., Rubin L.J. Riociguat for pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2268. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1312903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sitbon O., Channick R., Chin K.M., et al. Selexipag for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2522–2533. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Humbert M., McLaughlin V., Gibbs J.S.R., et al. Sotatercept for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1204–1215. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herve P., Launay J.M., Scrobohaci M.L., et al. Increased plasma serotonin in primary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Med. 1995;99:249–254. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chambers C.D., Hernandez-Diaz S., Van Marter L.J., et al. Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:579–587. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berger M., Gray J.A., Roth B.L. The expanded biology of serotonin. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:355–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.042307.110802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacLean M.R., Fanburg B., Hill N., et al. Serotonin and pulmonary hypertension; sex and drugs and ROCK and rho. Compr Physiol. 2022;12:4103–4118. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c220004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walther D.J., Bader M. A unique central tryptophan hydroxylase isoform. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:1673–1680. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00556-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walther D.J., Peter J.U., Bashammakh S., et al. Synthesis of serotonin by a second tryptophan hydroxylase isoform. Science. 2003;299:76. doi: 10.1126/science.1078197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eddahibi S., Guignabert C., Barlier-Mur A.M., et al. Cross talk between endothelial and smooth muscle cells in pulmonary hypertension: critical role for serotonin-induced smooth muscle hyperplasia. Circulation. 2006;113:1857–1864. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.591321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morecroft I., White K., Caruso P., et al. Gene therapy by targeted adenovirus-mediated knockdown of pulmonary endothelial Tph1 attenuates hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Mol Ther. 2012;20:1516–1528. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ciuclan L., Bonneau O., Hussey M., et al. A novel murine model of severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1171–1182. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0412OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dempsie Y., Morecroft I., Welsh D.J., et al. Converging evidence in support of the serotonin hypothesis of dexfenfluramine-induced pulmonary hypertension with novel transgenic mice. Circulation. 2008;117:2928–2937. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.767558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morecroft I., Dempsie Y., Bader M., et al. Effect of tryptophan hydroxylase 1 deficiency on the development of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49:232–236. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000252210.58849.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Izikki M., Hanoun N., Marcos E., et al. Tryptophan hydroxylase 1 knockout and tryptophan hydroxylase 2 polymorphism: effects on hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L1045–L1052. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00082.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abid S., Houssaini A., Chevarin C., et al. Inhibition of gut- and lung-derived serotonin attenuates pulmonary hypertension in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;303:L500–L508. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00049.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aiello R.J., Bourassa P.A., Zhang Q., et al. Tryptophan hydroxylase 1 inhibition impacts pulmonary vascular remodeling in two rat models of pulmonary hypertension. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017;360:267–279. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.237933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Condon D.F., Agarwal S., Chakraborty A., et al. Novel mechanisms targeted by drug trials in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2022;161:1060–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lazarus H.M., Denning J., Wring S., et al. A trial design to maximize knowledge of the effects of rodatristat ethyl in the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension (ELEVATE 2) Pulm Circ. 2022;12 doi: 10.1002/pul2.12088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Specker E., Matthes S., Wesolowski R., et al. Structure-based design of xanthine-benzimidazole derivatives as novel and potent tryptophan hydroxylase inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2022;65:11126–11149. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Legchenko E., Chouvarine P., Borchert P., et al. The PPARγ agonist pioglitazone reverses pulmonary hypertension and prevents right heart failure via fatty acid oxidation. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aao0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulke M.H., Horsch D., Caplin M.E., et al. Telotristat ethyl, a tryptophan hydroxylase inhibitor for the treatment of carcinoid syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:14–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bader M. Inhibition of serotonin synthesis: a novel therapeutic paradigm. Pharmacol Ther. 2020;205 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.107423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petrassi M., Barber R., Be C., et al. Identification of a novel allosteric inhibitory site on tryptophan hydroxylase 1 enabling unprecedented selectivity over all related hydroxylases. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:240. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valentine M.S., Bender A.M., Shay S., et al. Development of a peripherally restricted 5-HT2B partial agonist for treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2023;8:1379–1388. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2023.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.West J.D., Carrier E.J., Bloodworth N.C., et al. Serotonin 2B receptor antagonism prevents heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Long L., MacLean M.R., Jeffery T.K., et al. Serotonin increases susceptibility to pulmonary hypertension in BMPR2-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2006;98:818–827. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000215809.47923.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hansmann G., de Jesus Perez V.A., Alastalo T.P., et al. An antiproliferative BMP-2/PPARγ/apoE axis in human and murine SMCs and its role in pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1846–1857. doi: 10.1172/JCI32503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hansmann G., Wagner R.A., Schellong S., et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension is linked to insulin resistance and reversed by peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor-gamma activation. Circulation. 2007;115:1275–1284. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.663120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ke R., Xie X., Li S., et al. 5-HT induces PPAR γ reduction and proliferation of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells via modulating GSK-3β/β-catenin pathway. Oncotarget. 2017;8:72910–72920. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suzuki Y.J., Day R.M., Tan C.C., et al. Activation of GATA-4 by serotonin in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17525–17531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210465200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li M., Sun X., Li Z., Liu Y. Inhibition of cGMP phosphodiesterase 5 suppresses serotonin signalling in pulmonary artery smooth muscles cells. Pharmacol Res. 2009;59:312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gong Y., Yu Z., Gao Y., et al. FABP4 inhibitors suppress inflammation and oxidative stress in murine and cell models of acute lung injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;496:1115–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.01.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jackson W.F. Potassium channels in regulation of vascular smooth muscle contraction and growth. Adv Pharmacol. 2017;78:89–144. doi: 10.1016/bs.apha.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmaier A.H. Plasma kallikrein/kinin system: a revised hypothesis for its activation and its physiologic contributions. Curr Opin Hematol. 2000;7:261–265. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200009000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Samidurai A., Xi L., Das A., et al. Role of phosphodiesterase 1 in the pathophysiology of diseases and potential therapeutic opportunities. Pharmacol Ther. 2021;226 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghofrani H.A., Galie N., Grimminger F., et al. Riociguat for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:330–430. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang P., Sun Y., Peng R., et al. Long noncoding RNA Rpph1 promotes inflammation and proliferation of mesangial cells in diabetic nephropathy via an interaction with Gal-3. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:526. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1765-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calvier L., Legchenko E., Grimm L., et al. Galectin-3 and aldosterone as potential tandem biomarkers in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Heart. 2016;102:390–396. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fulton D.J.R., Li X., Bordan Z., et al. Galectin-3: a harbinger of reactive oxygen species, fibrosis, and inflammation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2019;31:1053–1069. doi: 10.1089/ars.2019.7753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barman S.A., Li X., Haigh S., et al. Galectin-3 is expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells and promotes pulmonary hypertension through changes in proliferation, apoptosis, and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2019;316:L784–L797. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00186.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barman S.A., Chen F., Li X., et al. Galectin-3 promotes vascular remodeling and contributes to pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:1488–1492. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201711-2308LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiao G., Wang T., Zhuang W., et al. RNA sequencing analysis of monocrotaline-induced PAH reveals dysregulated chemokine and neuroactive ligand receptor pathways. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:4953–4969. doi: 10.18632/aging.102922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hatzoglou A., Roussel J., Bourgeade M.F., et al. TNF receptor family member BCMA (B cell maturation) associates with TNF receptor–associated factor (TRAF) 1, TRAF2, and TRAF3 and activates NF-κB, Elk-1, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Immunol. 2000;165:1322–1330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miller J.T., Turner C.G., Otis J.S., et al. Inhibition of iNOS augments cutaneous endothelial NO-dependent vasodilation in prehypertensive non-Hispanic Whites and in non-Hispanic Blacks. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021;320:H190–H199. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00644.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xue Q., Yan Y., Zhang R., Xiong H. Regulation of iNOS on immune cells and its role in diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3805. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.