Abstract

Background

The increasing complexity of the healthcare environment and the necessity of multidisciplinary teamwork have highlighted the importance of interprofessional education (IPE). IPE aims to enhance the quality of patient care through collaborative education involving various healthcare professionals, such as doctors, nurses, and pharmacists. This study sought to analyze how game-based IPE activities influence students’ perceptions and reflective thinking. It also aimed to identify the shifts in perception and effectiveness caused by this educational approach.

Methods

The study is based on a game-based IPE program conducted at University A, involving medical and nursing students in structured learning and team-based activities. Data were collected using essays written by the students after they had participated in IPE activities. Text network analysis was conducted by extracting key terms, performing centrality analysis, and visualizing topic modeling to identify changes in students’ perceptions and reflective thinking.

Results

Keywords such as “patient,” “thought,” “group,” “doctor,” “nurse,” and “communication” played a crucial role in the network, indicating that students prioritized enhancing their communication and problem-solving skills within the educational environment. The topic modeling results identified three main topics, each demonstrating the positive influence of game-based collaborative activities, interprofessional perspectives, and interdisciplinary educational experiences on students. Topic 3 (interdisciplinary educational experience) acted as a significant mediator connecting Topic 1 (game-based collaborative activity experience) and Topic 2 (interprofessional perspectives).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that game-based IPE activities are an effective educational approach for enhancing students’ team building skills, particularly communication and interprofessional perspectives. Based on these findings, future IPE programs should focus on creating collaborative learning environments, strengthening communication skills, and promoting interdisciplinary education. The findings provide essential insights for educational designers and medical educators to enhance the effectiveness of IPE programs. Future research should assess the long-term impacts of game-based IPE on clinical practice, patient outcomes, and participants’ professional development.

Keywords: Interprofessional education, Game-based learning, Text network analysis, Reflective thinking, Collaborative learning

Background

With rapid changes in the healthcare environment and the advancement of systems, effective collaboration among various healthcare professionals is crucial to meet patients’ high expectations [1]. This underscores the growing importance of interprofessional education (IPE), which aims to develop the ability to collaborate efficiently as multidisciplinary teams [2, 3]. IPE involves students from two or more healthcare professions learning about, from, and with each other through collaborative education. The primary objective of IPE is to assist healthcare professionals, including doctors, pharmacists, and nurses, in developing the competence to collaborate more effectively in multidisciplinary teams to enhance patient care [4]. Its history began in the early twentieth century and has evolved to include numerous healthcare professionals such as nurses, pharmacists, and dentists [5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that IPE provides highly collaborative teamwork experiences that improve job satisfaction and enhance access to and safety in patient care [6]. Recent studies have also shown that IPE is pivotal not only in promoting professional autonomy, understanding of professional roles, teamwork, and collaboration, but also in providing essential knowledge and skills for improving healthcare services [7–13].

One innovative approach to enhancing IPE involves game-based learning, which integrates educational content with interactive gaming elements to create engaging and effective learning experiences. Game-based learning has been shown to enhance students’ motivation, participation, and retention of knowledge by providing a dynamic and immersive learning environment [14–16]. In the context of IPE, these activities can simulate real-life clinical scenarios that require collaboration, communication, and problem-solving among diverse healthcare professionals [17]. This method allows students to practice and develop these critical skills in a safe and controlled setting, thereby preparing them for actual clinical practice [18].

Previous IPE studies involving students primarily used surveys, interviews, and participant observations to assess changes in students’ knowledge acquisition, collaboration, teamwork skills, and attitudes [19–23]. While these approaches have provided valuable information for evaluating the effectiveness of IPE programs, they have limitations in terms of exploring students’ direct expressions and deep thinking. Recent research has started exploring game-based learning in IPE, emphasizing its potential to enhance collaboration, communication, and problem-solving skills among healthcare students [24, 25]. Game-based learning activities, such as serious games and simulations, offer engaging experiences that promote interprofessional collaboration and reflective thinking [17]. However, there is still a scarcity of research on students’ personal experiences, changing perceptions, and in-depth understanding of interprofessional collaboration through game-based learning. Addressing this gap can provide better relevance and context to the study of IPE.

Medical education literature has highlighted the importance of various educational strategies in enhancing reflective thinking skills [26, 27]. Dewey defines reflective thinking as conscious thought in the problem-solving process, which can be considered as the active utilization of knowledge gained through experience [28]. Narrative materials, such as essays, are useful tools for gaining an in-depth understanding of students’ experiences and perceptions. Thus, analyzing reflective thinking through essays can help students better understand their learning experiences and improve their problem-solving abilities through effective collaboration across different disciplines [29, 30].

This study aimed to analyze students’ perceptions of collaboration by examining essays they wrote after participating in game-based IPE activities, thereby providing evidence for the effectiveness of such education. The results of this study are expected to serve as foundational data to help design and implement more effective collaborative learning strategies for IPE programs.

Methods

Course design

The IPE program at a South Korean university targeted fifth-year medical and fourth-year nursing students to prepare them for clinical training. The course was divided into two phases: a six-day shadowing period and a four-day IPE activity period.

During the shadowing period, students observed various healthcare professionals in different clinical settings, including emergency rooms (ERs), ambulatory care, critical care, and outpatient environments. This phase emphasized understanding interprofessional roles and the importance of collaborative practice skills.

In the subsequent IPE activity period, students were grouped into teams of five or six, consisting of both medical and nursing students, to engage in team building exercises. These activities aimed to promote students’ collaboration, communication skills, mutual understanding in clinical settings. The activities during this phase were meticulously designed to develop essential soft skills through structured game-based exercises. These included the Marshmallow Challenge, which aimed to enhance understanding of team building dynamics; the Puzzle Game, which focused on defining roles and fostering teamwork to achieve a common objective; and the Message Game, which underscored the importance of clear and effective communication. Additional activities, such as the Drawing Shapes Game and the Drawing the Story Game, were designed to improve skills in accurate verbal description and to enhance understanding of the SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation) communication protocol, respectively. Finally, the Board Game was specifically developed to reinforce systems thinking and to illustrate the need for interdisciplinary collaboration in addressing complex issues in a hospital. Table 1 outlines the key activities included in this period.

Table 1.

Course structure of game-based IPE program

| Course | Game item | How to practice | Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| IPE activity | Marshmallow challenge |

Group competition Make the marshmallow stand at the highest point |

Understanding the concept of team building |

| Puzzle game |

Group competition Solve a 200-piece puzzle fastest Hidden mission is searching for the last piece, which is with the other group |

Find your own role and work together to achieve your goals | |

| Message game |

Whisper a simple newspaper article from person to person |

Understanding the importance of a clear message and writing down and reading back between the healthcare professionals | |

| Drawing shapes game | A game in which one person looks at a shape and explains it verbally to another group member to draw it |

Understanding the importance of accurate descriptions and learning the meaning of the 5 rights of the medication process |

|

| Drawing the story game | A game in which one person sees a scene from an Aesop’s fable, explains it verbally to the group, and then asks them to draw it | Understanding the SBARa protocol for accurate and efficient communication | |

| Board game |

Self-developed Select the person in charge of the emergency room, operating room, general ward, and intensive care unit area to make decisions about patients coming into the emergency room as a board game |

Reinforce systems thinking Understand that collaboration between various departments is necessary to solve problems that occur in the hospital |

aSBAR Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation is a structured communication tool used in healthcare to facilitate precise and efficient information transfer among professionals

This study aimed to analyze essays written by students after participating in the IPE activities to assess their reflections and learning outcomes.

Research procedure

The fundamental premise of text network analysis is to extract keywords representing the core content from the literature [31]. This study focused on understanding students’ thoughts and perceptions by analyzing their essays. The research process comprised (1) data collection, (2) keyword selection and data processing, (3) core keyword extraction and network construction, (4) network connectivity and centrality analysis, and (5) topic modeling. This approach facilitated a nuanced understanding of the conceptual relationships within the text, yielding deeper insights into students’ reflective thinking and experiences with interprofessional collaboration, thereby aligning with the objectives of this study.

Data collection

Data were collected in 2021 after the IPE program. Of the 82 medical students who participated in the program, 77 voluntarily submitted essays, representing a 93.9% response rate from the entire cohort enrolled in the IPE program. The essays were collected after the completion of the entire program, capturing students’ reflections and feelings about the course. These essays were not intended for assessment or evaluation purposes but were written freely by students to express their thoughts and experiences regarding the program. The primary aim was to gather qualitative insights into how students perceived and internalized the IPE activities, which aligns with the study’s objective to understand the impact of game-based learning on developing interprofessional collaboration, communication, and team building skills. We focused on medical students’ essays to explore their specific perspectives and experiences within the IPE program, as these students often play crucial roles in multidisciplinary teams. Therefore, understanding their views can provide valuable insights for improving IPE programs and enhancing interprofessional collaboration in clinical practice [32].

Keyword selection and data pre-processing

The student essays were collected using MS Office Excel. Pre-processing involved an initial review using Excel’s Spell Check, followed by manual corrections to fix typographical errors. Morphological analysis was performed using Netminer 4.5.1.c (CYRAM), which automatically removed pronouns and adverbs, leaving only nouns. To extract the words, 25 designated words, 40 synonyms, and 321 excluded words were pre-registered. Designated words are terms that convey specific meanings when grouped [33]. In this study, terms such as “interprofessional education” and “Friday Night at the ER” were classified as such. Synonyms, a group of words that have similar meanings, were processed as a single term that can represent the common meaning of those words [34]. For instance, “Friday night ER,” “FNER,” and “Friday night in the ER” were extracted as “Friday Night at ER.” Words considered irrelevant to the current research focus or general words that did not contribute to meaningful analysis were excluded (e.g., “and,” “or,” “front,” “inside,” “during”). Three professors specializing in emergency medicine and one medical educator handled word extraction and refinement, and the final selection was reviewed by the entire research team.

The data analysis utilized was qualitative content analysis, focusing on both the identification and contextual usage of keywords. This approach involved the descriptive counting of keywords as well as an in-depth analysis of their usage within the essays. This rigorous process ensured that the keywords selected were relevant to the study’s focus on IPE and collaboration, providing both quantitative and qualitative insights into the students’ reflections and experiences.

Extraction of core keywords and network construction

Core keyword extraction was based on the term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) method. The frequency of word occurrences is expressed as “term frequency (TF),” which indicates how often a word appears within a document [35]. By contrast, “inverse document frequency (IDF)” is calculated using the logarithmic value of the inverse of document frequency [36]. The TF-IDF value is computed by multiplying TF by IDF. A high value indicates that a word is important in a specific document but rarely appears in others [37]. This method allows the assessment of the importance of words in documents. For network analysis, the 2-mode word-document network was converted into a 1-mode word-word network. The co-occurrence frequency was set to occur at least twice, and the word proximity (window size) was set to two, following previous studies on text network analysis [38].

Network connectivity and centrality analysis

Network size and density, as well as the average degree and distance at the node level, were identified to understand the overall characteristics of the network. Network size denotes the total number of nodes (keywords). Density measures the ratio of actual connections to possible connections, indicating network cohesion. The average degree reflects the average number of connections per node, while the average distance shows the typical number of steps between nodes, revealing the network’s connectivity and compactness [35, 38]. Centrality analysis included degree, betweenness, and eigenvector centrality, whereas closeness centrality was excluded due to poor performance in lengthy texts [39]. Degree centrality measures how well a node is connected within a network, helping to identify keywords that play a central role in the network [40]. Betweenness centrality measures how frequently a node appears on the shortest path between other nodes, indicating how well it acts as an intermediary between two nodes [41]. Eigenvector centrality assesses the influence of a node by considering the importance of its neighboring nodes beyond the degree of connection [42]. This study extracted the top 30 words for each degree, betweenness, and eigenvector centrality. Finally, a spring map was used to visualize the keywords and their connection structures in the network.

Text network analysis was chosen because it provides a detailed understanding of relationships between concepts, unlike traditional methods that focus on theme frequency. It visualizes keyword interactions, highlighting central themes and their connections, offering insights into students’ reflections on IPE and their thought patterns.

Topic modeling

Latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) is a statistical text-processing technique that clusters keywords based on their probabilities and distributions to infer topics [43]. In this study, keywords extracted from essays were compiled into a matrix for LDA. To determine the optimal number of topics, combinations of α = 0.01–0.03, β = 0.01–0.03, topic model = 3–8, and 1,000 iterations were tested. The optimal model was selected based on the coherence score (c_v), with the highest coherence score ensuring the validity and reliability of the inferred topics [44–46].

Results

Key keywords

Table 2 presents the keywords derived from analyzing medical students’ essays selected through the TF and TF-IDF analyses. In the TF analysis, “thought” appeared most frequently (365 times), followed by “group” 359 times, “class” 322 times, and “game” 278 times. The top 20 keywords in TF-IDF included “patient,” “game,” “group,” and “person.” Keywords that appeared in both TF and TF-IDF analyses included “nursing school,” “nurse,” “game,” “hospital,” “person,” “mutual,” “communication,” “time,” “group,” “important,” “progress,” “puzzle,” “patient,” and “activity.” Comparing the keywords between TF and TF-IDF, new terms that emerged in TF-IDF included “IPE,” “room,” and “clinical practice.”

Table 2.

Top 20 keywords for TF and TF-IDF

| Rank | TF | TF-IDF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keywords | Frequency | Keywords | TF-IDF | |

| 1 | Thought | 365 | Patient | 62 |

| 2 | Group | 359 | Game | 61 |

| 3 | Class | 322 | Group | 60 |

| 4 | Game | 278 | Person | 56 |

| 5 | Doctor | 276 | Time | 55 |

| 6 | Patient | 245 | Mutual | 55 |

| 7 | Communication | 222 | Nurse | 55 |

| 8 | Hospital | 206 | Progress | 54 |

| 9 | Nurse | 176 | Important | 53 |

| 10 | Activity | 175 | Activity | 52 |

| 11 | Puzzle | 174 | Puzzle | 51 |

| 12 | Mutual | 150 | Communication | 51 |

| 13 | Nursing school | 149 | Nursing school | 51 |

| 14 | Time | 148 | Hospital | 50 |

| 15 | Person | 148 | Clinical practice | 47 |

| 16 | Progress | 146 | Room | 47 |

| 17 | Important | 135 | IPE | 46 |

| 18 | Delivery | 131 | Professor | 45 |

| 19 | Room | 104 | Delivery | 44 |

| 20 | Student | 102 | Situation | 44 |

TF Term Frequency, TF-IDF Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency

Text network analysis

Network structure

In this study, a network was constructed based on a co-occurrence frequency of at least two words with word proximity (window size) set to two words. The resulting network comprised 1,218 nodes and 627 links. The network density was 0.012, with an average degree and distance of 3.919 and 3.447, respectively.

Centrality analysis

Table 3 lists the top 30 keywords according to degree, betweenness, and eigenvector centralities, providing insight into the overall network characteristics. The top three keywords across all three centrality analyses included “patient,” “thought,” “group,” “doctor,” “nurse,” and “communication.” The ranking and composition of the keywords were similar in both degree and betweenness centrality analyses. In the eigenvector results, “doctor,” “nurse,” and “communication” were ranked highest. When comparing the top 30 keywords from eigenvector centrality with those from degree and betweenness centrality, new terms such as “future,” “society,” and “need” emerged. These findings are presented in Fig. 1, which illustrates the spring network map of centrality.

Table 3.

Top 30 keywords for centrality results

| Rank | Keywords | Degree centrality | Keywords | Betweenness centrality | Keywords | Eigenvector centrality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Patient | 0.14734 | Patient | 0.21587 | Doctor | 0.66566 |

| 2 | Thought | 0.12853 | Thought | 0.14818 | Nurse | 0.59275 |

| 3 | Group | 0.11599 | Group | 0.11374 | Communication | 0.30280 |

| 4 | Game | 0.11285 | Game | 0.10038 | Patient | 0.14435 |

| 5 | Class | 0.10658 | Doctor | 0.09311 | Thought | 0.10681 |

| 6 | Doctor | 0.10345 | Hospital | 0.08930 | Hospital | 0.09846 |

| 7 | Hospital | 0.08777 | Class | 0.08862 | Group | 0.08477 |

| 8 | Communication | 0.08150 | Nurse | 0.06368 | Important | 0.07725 |

| 9 | Mutual | 0.07837 | Communication | 0.05344 | Collaboration | 0.07277 |

| 10 | Nurse | 0.07837 | Progress | 0.05143 | Mutual | 0.06964 |

| 11 | Progress | 0.07524 | Delivery | 0.05125 | Need | 0.06382 |

| 12 | Delivery | 0.07524 | Mutual | 0.04792 | Medicine | 0.06128 |

| 13 | Activity | 0.06270 | Person | 0.04597 | Class | 0.06021 |

| 14 | Important | 0.05643 | Medicine | 0.04194 | Progress | 0.05190 |

| 15 | Puzzle | 0.05329 | Activity | 0.03620 | Game | 0.04533 |

| 16 | Medicine | 0.05329 | Situation | 0.03422 | Society | 0.04306 |

| 17 | Collaboration | 0.05016 | Important | 0.03273 | Mr. or Ms.a | 0.04300 |

| 18 | First | 0.05016 | Professor | 0.03131 | Role | 0.04264 |

| 19 | Person | 0.04702 | Room | 0.03024 | Puzzle | 0.04246 |

| 20 | Room | 0.04389 | First | 0.02886 | Person | 0.04161 |

| 21 | Professor | 0.04075 | Role | 0.02869 | Future | 0.03820 |

| 22 | Nursing school | 0.04075 | Nursing school | 0.02665 | Relationship | 0.03816 |

| 23 | Need | 0.03762 | Time | 0.02476 | Stance | 0.03447 |

| 24 | Role | 0.03762 | Clinical practice | 0.02475 | Task | 0.03258 |

| 25 | Student | 0.03448 | Student | 0.02295 | Respect | 0.03222 |

| 26 | Situation | 0.03448 | Puzzle | 0.01993 | Cooperation | 0.03169 |

| 27 | Healthcare professional | 0.03135 | Result | 0.01776 | Delivery | 0.03087 |

| 28 | Process | 0.03135 | Drug | 0.01768 | Healthcare professional | 0.03051 |

| 29 | Stance | 0.02821 | Relationship | 0.01738 | Colleague | 0.02813 |

| 30 | Medical school | 0.02821 | Content | 0.01620 | Life | 0.02719 |

aThe original Korean word (“sensayngnim”), which can be translated into Mr. or Ms., is often used as an honorific title in combination with the words “doctor” or “nurse”

Fig. 1.

Spring network map of centrality. a Degree centrality. b Betweenness centrality. c Eigenvector centrality

Topic modeling: selection of the number of topics

To determine the optimal number of topics, 54 combinations of options were tested, including α = 0.01–0.03, β = 0.01–0.03, topic models = 3–8, and 1,000 iterations. Three topics were identified.

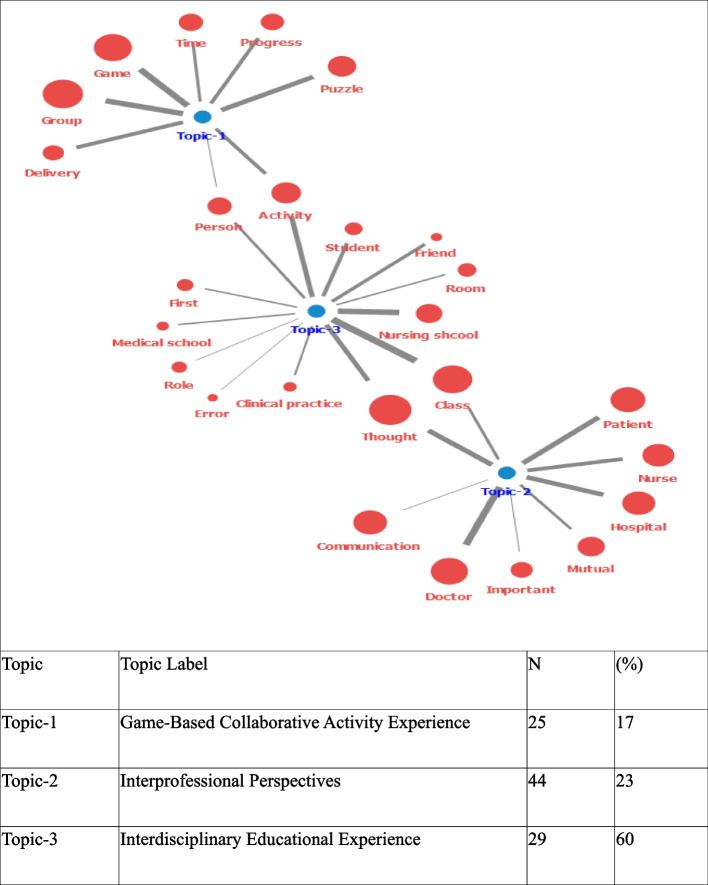

Topic modeling

In the topic modeling process, after reviewing the keywords and contents of the assigned original documents, the research team convened and named each topic to reflect the trend of the subject matter, as shown in Fig. 2. Following prior research, the final topic model was visualized using a topic-keyword map displaying the top eight to thirteen words [44]. Topic 1, accounting for 17% of the total topics, includes keywords such as “group,” “game,” “puzzle,” “delivery,” and “activity.” This reflects the inclusion of group-based, game-centric activities in the IPE classes; hence, it was named “game-based collaborative activity experience.” Topic 2 comprises 23% of the topics centered around the thoughts of doctors and nurses about patients in clinical settings, with keywords including “doctor,” “thought,” “patient,” “hospital,” and “nurse.” It was thus named “interprofessional perspectives.” Topic 3, with the largest share at 60%, incorporates keywords such as “class,” “nursing school,” “thought,” “activity,” and “student.” It primarily addresses class activities involving nursing students, thus the term “interdisciplinary educational experience.” Visually examining the entire network of topic modeling indicates that Topic 1, “game-based collaborative activity experience,” and Topic 3, “interdisciplinary educational experience,” are connected through the keywords “person” and “activity.” Topic 2, “Interprofessional Perspectives,” and Topic 3, are linked by “thought” and “class.” In the network, Topic 3 plays a vital role in connecting Topics 1 and 2, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Semantic keywords of topic modeling

Discussion

This study is the first attempt to demonstrate the educational impact of game-based IPE activities on fostering an interprofessional perspective, communication skills, and team building skills among healthcare professionals through a text network analysis of student essays. This distinguishes this study from previous studies. This approach can help students develop collaborative skills, thereby effectively addressing various challenges in clinical settings. The primary findings and implications of this study are as follows:

First, the keywords with the highest degree of centrality were “patient,” “thought,” and “group.” High-degree-centrality keywords play a central role in the entire network, suggesting that the overall program should be designed around these keywords. The keywords with high betweenness centrality were also “patient,” “thought,” and “group.” These keywords act as necessary connectors within the network, indicating that they are crucial for establishing communication channels between different professions and ensuring a smooth flow of information in medical education. Keywords with high eigenvector centrality included “doctor,” “nurse,” and “communication.” The prominence of keywords such as “doctor,” “nurse,” and “communication” in centrality measures signifies their strong connections to other important terms in the network. This highlights the pivotal role of doctors and nurses in collaborative practices and underscores the importance of communication skills in IPE programs. The central positioning of these keywords within the network emphasizes the need to prioritize interprofessional roles and communication competencies to enhance collaborative practices in clinical settings. These results align with previous findings emphasizing the importance of education in promoting effective collaboration and communication among healthcare professionals [47]. The centralities thus provide quantitative evidence supporting the critical roles and interactions that are essential for successful IPE.

The relevance of these keywords can be understood within the framework of the Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) Core Competencies, which emphasize patient-centered care, reflective thinking, and effective communication. The central keywords align with IPEC’s domains: values/ethics for interprofessional practice, roles/responsibilities, interprofessional communication, and teams/teamwork [4, 48]. For instance, “patient” and “group” correspond to the emphasis on patient-centered care and teamwork, while “thought” and “communication” are essential for reflective practice and effective interprofessional communication. Integrating IPE into medical education strengthens transparent and efficient teamwork across different specialties, minimizes errors in clinical decision-making, and improves patient outcomes. Consequently, medical schools should develop curricula that provide students with ample opportunities to collaborate with team members from various specialties [49].

Second, the topic modeling analysis indicated that Topic 1 provides a collaborative experience through group-based gaming activities in an IPE course. This aligns with previous research, indicating that game-based learning can enhance participants’ socialization and communication skills. Thornton Bacon et al. [50] and Sanko et al. [51] reported that students who participated in the Friday Night at Emergency Room (FNER) game demonstrated a statistically significant increase in systems thinking scores. In addition, Fusco et al. [52] confirmed that gameplay positively affected students’ systematic thinking, effective collaboration, and socialization skills. This suggests that game-based learning is useful for developing collaborative problem-solving skills and can be effectively integrated into various educational designs of IPE programs. Topic 2 highlights the significant focus on the perspectives of healthcare professionals in clinical environments. According to Bridges et al. [53] and Prentice et al. [54], IPE provides opportunities to develop a better understanding of roles and improve communication among healthcare team members. In this process, improving knowledge about one’s own roles and responsibilities as well as those of other professions can enhance teamwork between professionals [55]. This finding suggests that IPE programs can improve the quality of healthcare delivery by fostering mutual respect and understanding among different healthcare professionals. Topic 3 primarily addressed class activities for nursing students and included interdisciplinary educational experiences. These results show that game-based IPE activities are an effective educational method for enhancing interprofessional perspectives and communication skills, going beyond traditional lectures that simply deliver knowledge to students.

Additionally, Bjerkvik and Hilli [56] stated that expressing thoughts through writing facilitates the understanding of personal experiences. This enables learners to explore their emotions and attitudes, ultimately leading them to deeper self-understanding and professional growth. Consequently, this study analyzed students’ reflective thinking through topic modeling and presented evidence that game-based IPE activities are crucial in promoting learners’ reflective thinking and professional growth.

This study has several limitations. First, a limited group of students from a specific university participated in this study, which may have restricted the generalizability of the findings. Additional research is required to verify the results of this study across multiple student groups from various backgrounds and environments. Second, the research methodology relied on text analysis of student essays, focusing only on students’ subjective experiences and perceptions. To address this limitation, we used a rigorous coding scheme, inter-rater reliability checks, and TF-IDF for keyword extraction. Our methodology included keyword selection, data pre-processing, network construction, and LDA-based topic modeling, optimized with the coherence score (c_v). These steps ensured that the data analysis was both robust and reliable. Additionally, incorporating multiple methods for data analysis allowed us to cross-verify the findings and enhance the overall rigor of the study. Future research should integrate a range of methods, including interviews and surveys, to achieve a more comprehensive evaluation. Third, the effects of IPE programs on students’ collaborative competencies in clinical practice and healthcare settings is limited. Future research should explore the long-term impacts of game-based IPE on clinical practice, patient outcomes, and students’ readiness for clinical environments. Additionally, tracking the career progression and professional development of participants will help assess the sustained benefits of these educational interventions.

Conclusions

This study is the first to explore changes in reflective thinking and perceptions among students who participated in IPE programs. This demonstrates the positive effects of IPE on professional healthcare students. Specifically, through the analysis of degree, betweenness, and eigenvector centrality, we identified keywords such as “patient,” “thought,” “group,” “doctor,” “nurse,” and “communication” as crucial to interprofessional perspectives and communication among healthcare professionals. Topic modeling further underscores the importance of game-based learning, interprofessional perspectives, and interdisciplinary educational experiences.

These findings emphasize the need for innovative teaching methods in medical education and reaffirm the importance of promoting effective inter-professional perspective, communication skills and team building skills. Medical schools should strive to improve the design and implementation of their IPE program by incorporating students’ experiences and reflective insights. This will ultimately improve the quality of medical education. This study can serve as valuable foundational data for future research. Future studies should investigate the long-term effects of game-based IPE on clinical practice and patient outcomes. Research should also explore the impact of game-based IPE on participants’ career progression and professional development to assess sustained benefits. Additionally, future research could examine how different game-based learning activities influence specific interprofessional competencies, such as teamwork, communication, and problem-solving skills, to identify the most effective approaches for IPE programs.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank all those who have contributed to this work through their support, insights, and encouragement.

Abbreviations

- IPE

Interprofessional education

- FNER

Friday night at emergency room

- LDA

Latent Dirichlet allocation

- TF

Term frequency

- TF-IDF

Term frequency-inverse document frequency

- IDF

Inverse document frequency

Authors’ contributions

Study conception and design: YK, MN, CK. Data collection: YK, MN, CK. Data analysis and interpretation: YK, MN, SM, EE, CK. Drafting of the article: YK, MN, SP, MK. Critical revision of the article: YK, MN, SP, SM, EE, CK.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical constraints but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Chung-Ang University determined that this study meets the criteria for an exemption from IRB review, as it involves research conducted in established or commonly accepted educational settings and involves normal educational practices. Approval Number: 1041078–20240321-HR-051. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating students. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fox A, Reeves S. Interprofessional collaborative patient-centred care: a critical exploration of two related discourses. J Interprof Care. 2015;29:113–8. 10.3109/13561820.2014.954284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilligan C, Outram S, Levett-Jones T. Recommendations from recent graduates in medicine, nursing and pharmacy on improving interprofessional education in university programs: A qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:52. 10.1186/1472-6920-14-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haresaku S, Naito T, Aoki H, Miyoshi M, Monji M, Umezaki Y, et al. Development of interprofessional education programmes in nursing care and oral healthcare for dental and nursing students. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24:381. 10.1186/s12909-024-05227-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohammed CA, Anand R, Saleena Ummer VS. Interprofessional education (IPE): A framework for introducing teamwork and collaboration in health professions curriculum. Med J Armed Forces India. 2021;77(Suppl 1):S16-21. 10.1016/j.mjafi.2021.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmitt MH, Gilbert JH, Brandt BF, Weinstein RS. The coming of age for interprofessional education and practice. Am J Med. 2013;126:284–8. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. p. 13–15.5.

- 7.Curran VR, Sharpe D, Flynn K, Button P. A longitudinal study of the effect of an interprofessional education curriculum on student satisfaction and attitudes towards interprofessional teamwork and education. J Interprof Care. 2010;24:41–52. 10.3109/13561820903011927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reeves S, Goldman J, Burton A, Sawatzky-Girling B. Synthesis of systematic review evidence of interprofessional education. J Allied Health. 2010;39(Suppl 1):198–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brock D, Abu-Rish E, Chiu CR, Hammer D, Wilson S, Vorvick L, et al. Interprofessional education in team communication: Working together to improve patient safety. Postgrad Med J. 2013;89:642–51. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-000952rep [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers O, Heck A, Kohnert L, Paode P, Harrell L. Occupational therapy’s role in an interprofessional student-run free clinic: Challenges and opportunities identified. Open J Occup Ther. 2017;5:7. 10.15453/2168-6408.1387 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peeters MJ, Sexton M, Metz AE, Hasbrouck CS. A team-based interprofessional education course for first-year health professions students. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2017;9:1099–110. 10.1016/j.cptl.2017.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imafuku R, Kataoka R, Ogura H, Suzuki H, Enokida M, Osakabe K. What did first-year students experience during their interprofessional education? A qualitative analysis of e-portfolios. J Interprof Care. 2018;32:358–66. 10.1080/13561820.2018.1427051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alzamil H, Meo SA. Medical students’ readiness and perceptions about interprofessional education: a cross sectional study. Pak J Med Sci. 2020;36:693–8. 10.12669/pjms.36.4.2214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu H, Xiao Y, Li H. The effectiveness of a serious game versus online lectures for improving medical students’ coronavirus disease 2019 knowledge. Games Health J. 2021;10:139–44. 10.1089/g4h.2020.0140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu M, Luo Y, Zhang Y, Xia R, Qian H, Zou X. Game-based learning in medical education. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1113682. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1113682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Surapaneni KM. Livogena: The Ikteros curse—A jaundice narrative card and board game for medical students. MedEdPORTAL. 2024;20:11381. 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fusco NM, Jacobsen LJ, Klem N, Krzyzanowicz R, Ohtake PJ. A serious game employed to introduce principles of interprofessional collaboration to students of multiple health professions. Simul Gaming. 2022;53:253–64. 10.1177/10468781221093816 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Umoren R, editor. Simulation and Game-Based Learning for the Health Professions. Hershey: IGI Global; 2022.

- 19.Thannhauser J, Russell-Mayhew S, Scott C. Measures of interprofessional education and collaboration. J Interprof Care. 2010;24:336–49. 10.3109/13561820903442903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenfield D, Oandasan I, Reeves S. Perceptions versus reality: a qualitative study of students’ expectations and experiences of interprofessional education. Med Educ. 2011;45:471–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03883.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darlow B, Donovan S, Coleman K, McKinlay E, Beckingsale L, Gallagher P, et al. What makes an interprofessional education programme meaningful to students? Findings from focus group interviews with students based in New Zealand. J Interprof Care. 2016;30:355–61. 10.3109/13561820.2016.1141189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Almoghirah H, Nazar H, Illing J. Assessment tools in pre-licensure interprofessional education: A systematic review, quality appraisal and narrative synthesis. Med Educ. 2021;55:795–807. 10.1111/medu.14453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gysin S, Huber M, Feusi E, Gerber-Grote A, Witt CM. Interprofessional education day 2019–A qualitative participant evaluation. GMS J Med Educ. 2022;39:Doc52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedrich C, Teaford H, Taubenheim A, Boland P, Sick B. Escaping the professional silo: an escape room implemented in an interprofessional education curriculum. J Interprof Care. 2019;33:573–5. 10.1080/13561820.2018.1538941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedrich C, Teaford H, Taubenheim A, Sick B. Interprofessional health care escape room for advanced learners. J Nurs Educ. 2020;59:46–50. 10.3928/01484834-20191223-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandars J. The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 4. Med Teach. 2009;31:685–95. 10.1080/01421590903050374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wald HS, Borkan JM, Taylor JS, Anthony D, Reis SP. Fostering and evaluating reflective capacity in medical education: Developing the REFLECT rubric for assessing reflective writing. Acad Med. 2012;87:41–50. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823b55fa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodgers C. Defining reflection: Another look at John Dewey and reflective thinking. Teach Coll Rec. 2002;104:842–66. 10.1177/016146810210400402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Entwistle N. Frameworks for understanding as experienced in essay writing and in preparing for examination. Educ Psychol. 1995;30:47–54. 10.1207/s15326985ep3001_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin CW, Lin MJ, Wen CC, Chu SY. A word-count approach to analyze linguistic patterns in the reflective writings of medical students. Med Educ Online. 2016;21:29522. 10.3402/meo.v21.29522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang L, Li K, Huang H. A new network model for extracting text keywords. Scientometrics. 2018;116:339–61. 10.1007/s11192-018-2743-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zechariah S, Ansa BE, Johnson SW, Gates AM, Leo GD. Interprofessional education and collaboration in healthcare: an exploratory study of the perspectives of medical students in the United States. Healthcare. 2019;7:117. 10.3390/healthcare7040117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee SS. A content analysis of journal articles using the language network analysis methods. J Korean Soc Inf Manag. 2014;31:49–68. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Won J, Kim K, Sohng KY, Chang SO, Chaung SK, Choi MJ, et al. Trends in nursing research on infections: semantic network analysis and topic modeling. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:6915. 10.3390/ijerph18136915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park ST, Liu C. A study on topic models using LDA and Word2Vec in travel route recommendation: Focus on convergence travel and tours reviews. Pers Ubiquitous Comput. 2022;26:429–45. 10.1007/s00779-020-01476-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robertson S. Understanding inverse document frequency: On theoretical arguments for IDF. J Doc. 2004;60:503–20. 10.1108/00220410410560582 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Dagvadorj A, Kim HS. Research trends of human resources management in hotel industry: Evidence from South Korea by semantic network analysis. Culinary Sci Hosp Res. 2021;27:68–78. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park MY, Jeong SH, Kim HS, Lee EJ. Images of nurses appeared in media reports before and after outbreak of COVID-19: Text network analysis and topic modeling. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2022;52:291–307. 10.4040/jkan.22002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boudin F. A comparison of centrality measures for graph-based keyphrase extraction. In: Proceedings of the sixth international joint conference on natural language processing. 2013. p. 834–8. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valente TW, Coronges K, Lakon C, Costenbader E. How correlated are network centrality measures? Connect (Tor). 2008;28:16–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ausiello G, Firmani D, Laura L. The (betweenness) centrality of critical nodes and network cores. In: 9th International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC), 2013. Sardinia: IEEE; 2013. p. 90–5.

- 42.Maharani W, Adiwijaya AA, Gozali AA. Degree centrality and eigenvector centrality in Twitter. In: 8th International Conference on Telecommunication Systems Services and Applications (TSSA), 2014. Bali: IEEE; 2014. p. 1–5.

- 43.Blei DM, Lafferty JD. Topic models. In: Text Mining. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2009. p. 101–24.

- 44.Lee JW, Kim Y, Han DH. LDA-based topic modeling for COVID-19-related sports research trends. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1033872. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1033872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Colla D, Delsanto M, Agosto M, Vitiello B, Radicioni DP. Semantic coherence markers: The contribution of perplexity metrics. Artif Intell Med. 2022;134: 102393. 10.1016/j.artmed.2022.102393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jang JH, Masatsuku N. A study of factors influencing happiness in Korea: Topic modelling and neural network analysis. Data and Metadata. 2024;3:238–238. 10.56294/dm2024238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buring SM, Bhushan A, Broeseker A, Conway S, Duncan-Hewitt W, Hansen L, et al. Interprofessional education: definitions, student competencies, and guidelines for implementation. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73:59. 10.1016/S0002-9459(24)00554-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thistlethwaite JE, et al. Competencies and frameworks in interprofessional education: a comparative analysis. Acad Med. 2014;89:869–87. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barnsteiner JH, Disch JM, Hall L, Mayer D, Moore SM. Promoting interprofessional education. Nurs Outlook. 2007;55:144–50. 10.1016/j.outlook.2007.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thornton Bacon C, Trent P, McCoy TP. Enhancing systems thinking for undergraduate nursing students using Friday Night at the ER. J Nurs Educ. 2018;57:687–9. 10.3928/01484834-20181022-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanko JS, Gattamorta K, Young J, Durham CF, Sherwood G, Dolansky M. A multisite study demonstrates positive impacts to systems thinking using a table-top simulation experience. Nurse Educ. 2021;46:29–33. 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fusco NM, Foltz-Ramos K, Ohtake PJ, Mann C. Interprofessional simulation learning game increases socialization and teamwork among students of health professions programs. Nurse Educ. 2024;49:E32–5. 10.1097/NNE.0000000000001341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bridges D, Davidson RA, Soule Odegard P, Maki IV, Tomkowiak J. Interprofessional collaboration: three best practice models of interprofessional education. Med Educ Online. 2011;16(1):6035. 10.3402/meo.v16i0.6035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prentice D, Engel J, Taplay K, Stobbe K. Interprofessional collaboration: The experience of nursing and medical students’ interprofessional education. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2015;2:2333393614560566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilhelmsson M, Pelling S, Uhlin L, Owe Dahlgren L, Faresjö T, Forslund K. How to think about interprofessional competence: A metacognitive model. J Interprof Care. 2012;26:85–91. 10.3109/13561820.2011.644644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bjerkvik LK, Hilli Y. Reflective writing in undergraduate clinical nursing education: A literature review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2019;35:32–41. 10.1016/j.nepr.2018.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical constraints but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.