Abstract

The global incidence of non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) infections is on the rise. This study systematically searched several databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and two Chinese libraries (Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang) to identify relevant published between 2013 and 2023 related to the isolation of NTM in clinical specimens from various countries and provinces of China. Furthermore, a comprehensive literature review was conducted in PubMed and Google Scholar to identify randomized clinical trials, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and observational studies that evaluated the diagnostic accuracy and impact of laboratory detection methods on clinical outcomes. This review presented the most recent epidemiological data and species distributions of NTM isolates in several countries and provinces of China. Moreover, it provided insights into laboratory bacteriological detection, including the identified strains, advantages and disadvantages, recent advancements, and the commercial Mycobacterium identification kits available for clinical use. This review aimed to aid healthcare workers in understanding this aspect, enhance the standards of clinical diagnosis and treatment, and enlighten them on the existing gaps and future research priorities.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Molecular diagnostic technique, Mycobacterium identification kit, Non-tuberculous mycobacteria, Species identification

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

The most common non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) species were M. avium complex, M. gordonae, M. xenopi, whereas in China, M. intracellulare, M. abscessus, and M. kansasii were frequently isolated.

-

•

In China, M. chelonae/abscessus was more prevalent in the south, while M. kansasii exhibited greater prevalence in the north.

-

•

As molecular technology advances, healthcare workers will gain deeper insights, enhancing comprehensive epidemiological investigations into NTM.

1. Introduction

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), also known as atypical mycobacteria, refer to mycobacterial species other than those belonging to the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC, including M. africanum, M. bovis, M. caprae, M. canetti, M. microti, and M. pinnipedii) and M. leprae [1,2]. NTM are environmental and opportunistic pathogens that are found primarily in water and soil, predominantly infecting individuals with risk factors [3,4]. With over 200 species/subspecies identified (http://www.bacterio.net/mycobacterium.html), approximately 60 are responsible for the disease [5]. The incidence of NTM infections has been steadily rising, posing significant public health challenge and threatening human health [6], probably owing to the increased number of patients with underlying respiratory diseases or immunosuppression coupled with advancements in diagnostic techniques [7]. NTM infections can cause four different clinical symptoms: chronic lung disease, lymphadenitis, skin disease, and disseminated disease, with non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) being the most prevalent. The diagnosis of NTM-PD necessitates fulfillment of all clinical, radiographic, and microbiological criteria [8]. Moreover, extrapulmonary mycobacterial infections can affect a plethora of anatomical sites including the brain, eye, mouth, tongue, lymph nodes, bones, muscles, skin, pleura, pericardium, gastrointestinal tract, peritoneum, and genitourinary system [9]. The differential diagnosis between M. tuberculosis (MTB) and NTM is intricate due to their similar smear acid-fast staining positivity, often leading to diagnostic confusion [10]. In many epidemiological investigations, NTM has demonstrated resistance to anti-tuberculosis (TB) drugs, and antimicrobial susceptibilities vary among species, further complicating clinical management [11,12]. Therefore, improving understanding of NTM and accurately identifying the species is imperative for prompt and precise treatment of NTM-related diseases. This review presented the most recent epidemiological data and species distributions of NTM isolates in various countries and provinces of China. Moreover, it elucidated advancements in laboratory bacteriological detection and catalogs commercial Mycobacterium identification kits. This review aimed to aid healthcare workers in understanding the epidemiology and laboratory detection of NTM, enhance the standards of clinical diagnosis and treatment, and enlighten them of the existing gaps and future research priorities.

2. Methods

Several databases, such as PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and two Chinese libraries (Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang), were searched for studies published between 2013 and 2023 that investigated the isolation of NTM in clinical specimens from various countries and provinces of China, especially in high-TB burden and developing countries. Additionally, a comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed and Google Scholar to identify randomized clinical trials, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and observational studies to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy and impact of laboratory detection methods on clinical outcomes. The search terms used were “non-tuberculous mycobacteria,” “NTM,” “China,” “India,” “Africa,” “epidemiology,” “prevalence,” “isolation,” “molecular diagnostics,” “multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR),” “real-time PCR,” and “detection.” Epidemiological studies were excluded from the analysis if they only focused on TB; involved specific patient groups, such as patients with HIV-positive test results; and involved animal/nonhuman studies. In cases where multiple articles used epidemiological data from the same geographic area, preference was given to the most recent, comprehensive, and representative study.

3. Epidemiology

The incidence and prevalence of NTM are increasing at the national level in many countries [7,13,14]. In a study spanning 30 countries across 6 continents, the most common NTM species isolated from pulmonary specimens were the M. avium complex (MAC, including M. avium and M. intracellulare), followed by M. gordonae, M. xenopi, M. fortuitum, M. abscessus complex (MABC), and M. kansasii [15]. The common NTM species found in extrapulmonary specimens included MABC, M. fortuitum, and M. scrofulaceum [9]. The distribution of NTM species isolated from clinical samples exhibits geographic specificity, and the species of NTM can vary within the same country [16]. Upon examining Table 1, in China, the most commonly isolated NTM species were M. intracellulare, M. abscessus, and M. kansasii. In India, the prevalent NTM species included M. abscessus, M. fortuitum, and M. porcinum. Meanwhile, in Iran, the frequently isolated NTM species were M. simiae, M. fortuitum, M. kansasii, and M. marinum.

Table 1.

Three most prevalent non-tuberculous mycobacteria species found in various clinical specimens in several countries.

|

Region |

Study period | NTM isolates (n) | Ranking of most commonly isolated NTM species (% of isolates) |

Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | ||||

| Singapore | 2012–2016 | 2026 | M. abscessus complex (49.9 %) | M. fortuitum group (17.0 %) | M. avium complex (15.4 %) | [17] |

| Korea | 2016–2020 | 2521 | M. intracellulare (45.8 %) | M. avium (21.4 %) | M. abscessus (7.9 %) | [18] |

| China | 2017–2019 | 513 | M. intracellulare (46.5 %) | M. abscessus (28.6 %) | M. kansasii (17.4 %) | [19] |

| Japan | 2012–2013 | 26,059 | M. avium (61.8 %) | M. intracellulare (31.1 %) | M. kansasii (2.1 %) | [20] |

| South India | 2018–2020 | 45 | M. intracellulare (25.5 %) | M. abscessus (15.3 %) | M. scrofulaceum (12.2 %) | [21] |

| North India | 2014–2016 | 42 | M. abscessus (35.7 %) | M. intracellulare (28.6 %) | M. simiae (11.9 %) | [22] |

| India | 2015–2020 | 69 | M. abscessus (33.3 %) | M. fortuitum (24.6 %) | M. porcinum (5.8 %) | [23] |

| Cambodia | 2012–2014 | 123 | M. fortuitum (22.3 %) | M. intracellulare (18.7 %) | M. abscessus (11.3 %) | [24] |

| Pakistan | 2016–2019 | 191 | M. avium complex (61 %) | M. abscessus (24 %) | M. fortuitum (5.5 %), M. kansasii (5.5 %) | [25] |

| Saudi Arabia | 2006–2012 | 380 | M. avium complex (35 %) | M. fortuitum (24 %) | M. abscessus complex (17 %) | [26] |

| Iran | 2020–2021 | 62 | M. simiae (29.0 %) | M. fortuitum (21.1 %) | M. kansasii (14.5 %), M. marinum (14.5 %) | [27] |

| Indonesia | 2020–2021 | 94 | M. fortuitum (51 %) | M. abscessus (38.3 %) | M. intracellulare (3.1 %) | [28] |

| American | 2019–2020 | 231 | M. avium (41.6 %) | M. intracellulare (18.6 %) | M. abscessus complex (8.7 %) | [29] |

| Brazil | 2003–2013 | 100 | M. avium complex (35 %) | M. kansasii (17 %) | M. abscessus (12 %) | [30] |

| UK | 2007–2014 | 853 | M. intracellulare (31.3 %) | M. avium (21.2 %) | M. gordonae (15.2 %) | [31] |

| French | 2002–2013 | 170 | M. avium (31.8 %) | M. intracellulare (20 %) | M. marinum (13.5 %) | [32] |

| Poland | 2013–2022 | 395 | M. kansasii (34 %) | M. avium (30 %) | M. gordonae (10 %) | [33] |

| Belgium | 2010–2017 | 384 | M. avium (25 %) | M. intracellulare (16.7 %) | M. gordonae (14.6 %) | [34] |

| Tunisia | 2002–2016 | 27 | M. kansasii (23.3 %) | M. fortuitum (16.6 %), M. novocastrense (16.6 %) | M. chelonae (10.0 %) | [35] |

| South Africa | 2010 | 133 | M. intracellulare (45.9 %) | M. avium (11.3 %) | M. gordonae (6 %) | [36] |

| Nigeria | 2010–2011 | 69 | M. intracellulare (30.4 %) | M. abscessus (11.6 %) | M. fortuitum (5.8 %) | [37] |

MAC was the dominant species in most location, as shown in Table 1. However, the prevalence of MAC ranged from 0 % in Iran [27] to 93.3 % in Japan [20]. Upon examining Table 1 and it was evident that M. abscessus was the most common isolated NTM species in Singapore and India, M. kansasii in Poland and Tunisia, M. simiae in Iran, M. fortuitum in Indonesia.

In the United States, MAC was more common in the South, while MABC and M. chelonae were more common in the West [38]. In Japan, the isolation rate of MABC was higher in the northern region [39]. In India, M. intracellulare was the most common NTM species in South India, and M. abscessus in North India (Table 1). Furthermore, differences within China were also noted, as outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of studies on non-tuberculous mycobacteria in China.

|

Province |

Study period | NTM isolation rate (%) | Predominant species | Age ratio of NTM-PD patients | Complications of NTM- PD patients | Clinical symptoms of NTM-PD patients | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing (north region) | 2019 | 6.5 |

M. intracellulare (24.69 %) M. abscessus (24.69 %) M. kansasii (19.75 %) |

0–40:32.10 % 40–60:13.58 % ≥60:54.32 % |

NA | NA | [40] |

| Tianjin (north region) | 2018~2019 | NA |

M. intracellulare (29.08 %) M. chelonae/abscessus (26.60 %) M. kansasii (23.41 %) |

15–40:26.60 % 40–60:29.79 % ≥60:43.62 % |

NA | NA | [41] |

| Jilin (north region) | 2017~2018 | 2.68 |

M. intracellulare (40.59 %) M. kansasii (26.73 %) M. avium (4.95 %) |

≤40:5.94 % 40–60:21.78 % ≥60:72.28 % |

NA | NA | [42] |

| Liaoning (north region) | 2016~2021 | 3.95 |

M. intracellulare (55.91 %) M. abscessus (25.20 %) M. kansasii (8.66 %) |

NA | TB:4.85 % COPD:4.85 % Diabetes:10.68 % Cancer:5.83 % |

NA | [43] |

| Shandong (north region) | 2015~2019 | 11.6 |

M. intracellulare (69.77 %) M. kansasii (12.71 %) M. abscessus (9.89 %) |

<45:15.25 % 45–60:35.88 % 60–90:48.87 % |

NA | NA | [44] |

| Henan (north region) | 2018~2020 | 3.93 |

M. intracellulare (74.93 %) M. kansasii (9.37 %) M. abscessus (5.79 %) |

<50:22.87 % ≥50:77.13 % |

NA | NA | [45] |

| Shaanxi (north region) | 2019~2021 | 3.5 |

M. intracellulare (36.7 %) M. chelonae/abscessus (26.6 %) M. kansasii (25.0 %) |

14–39:32.58 % 40–65:44.94 % >65:19.10 % |

NA | Cough/Expectoration:82.56 % Hemoptysis:27.91 % Fever:36.05 % Asthma:48.84 % |

[46] |

| Gansu (north region) | 2012~2014 | 4.91 |

M. intracellulare (72.09 %) M. kansasii (6.97 %) |

NA | NA | NA | [47] |

| Xinjiang (north region) | 2009~2011 | 4.98 |

M. avium/intracellulare (43.72 %) M. chelonae/abscessus (13.12 %) |

NA | NA | NA | [48] |

| Chongqing (south region) | 2016~2017 | NA |

M. abscessus (38.75 %) M. intracellulare (31.25 %) M. fortuitum (17.50 %) |

<30:23.18 % 30–40:10.53 % 40–50:22.11 % 50–60:15.79 % 60–80:25.28 % |

NA | NA | [49] |

| Sichuan (south region) | 2016~2021 | 2.75 |

M. chelonae/abscessus (31.06 %) M. avium (26.52 %) M. intracellulare (26.52 %) |

<20:3.4 % 20–40:27.3 % 40–60:40.2 % ≥60:29.3 % |

AIDS:14.8 % Bronchiectasis:18.2 % COPD:3.8 % Diabetes:6.1 % |

NA | [50] |

| Hubei (south region) | 2016~2020 | 6.66 |

M. intracellulare (37.88 %) M. abscessus (13.63 %) M. gordonae (5.01 %) |

<35:10.22 % 35–54:23.65 % 55–64:24.05 % >64:42.09 % |

Bronchiectasis:11.22 % COPD:4.21 % Cancer:1.20 % AIDS:0.40 % |

NA | [51] |

| Anhui (south region) | 2021~2022 | 8.2 |

M. intracellulare (74.5 %) M. abscessus (13.6 %) M. kansasii (7.6 %) |

20–39:5.5 % 40–59:36.7 % ≥60:57.8 % |

Bronchiectasis:33.76 % COPD:13.92 % AIDS: 13.92 % Cancer:2.53 % Diabetes:5.06 % |

Cough/Expectoration:71.73 % Hemoptysis:21.94 % Fever:10.97 % Asthma:16.88 % |

[52] |

| Jiangsu (south region) | 2017~2020 | 22.3 |

M. intracellulare (60.7 %) M. chelonae/abscessus (16.1 %) M. avium (10.7 %) |

NA | NA | NA | [53] |

| Shanghai (south region) | 2017~2018 | NA |

M. intracellulare (54.4 %) M. abscessus (22.2 %) M. kansasii (7.8 %) |

NA | NA | Cough:83.58 % Expectoration:80.60 % Hemoptysis:25.37 % Fever:47.76 % Dyspnea:22.39 % |

[54] |

| Zhejiang (south region) | 2009~2014 | 25.8 |

M. intracellulare (60.74 %) M. kansasii (13.33 %) M. avium (4.44 %) |

15–35:16.1 % 35–45:13.6 % 45–55:23.5 % 55–65:19.8 % ≥65:31.5 % |

NA | NA | [55] |

| Fujian (south region) | 2016~2019 | 6.35 |

M. intracellulare (65.73 %) M. chelonae/abscessus (18.78 %) M. kansasii (4.23 %) |

NA | NA | NA | [56] |

| Jiangxi (south region) | 2017~2020 | NA |

M. avium (50 %) M. intracellulare (21.15 %), M. chelonae/abscessus (14.23 %) |

NA | Bronchiectasis:21.15 % COPD:19.23 % AIDS: 3.85 % Cancer:28.85 % Diabetes:6.73 % |

Cough:53.85 % Expectoration:40.38 % Hemoptysis:18.27 % Fever:32.69 % |

[57] |

| Hunan (south region) | 2019~2020 | 8.06 |

M. abscessus (38.29 %), M. intracellulare (33.14 %) M. avium (12.19 %) |

NA | NA | NA | [58] |

| Guizhou (south region) | 2012~2013 | 2.64 |

M. intracellulare (32.26 %), M. chelonae/abscessus (29.03 %) M. avium (25.81 %) |

NA | NA | NA | [59] |

| Yunnan (south region) | 2013~2015 | 1.61 |

M. intracellulare (44.83 %) M. abscessus (27.59 %) M. avium (11.49 %) |

<20:1.15 % 20–39:18.39 % ≥40:80.46 % |

NA | NA | [60] |

| Guangdong (south region) | 2018~2019 | 30.3 |

M. chelonae/abscessus (41.2 %) M. avium/intracellulare (40.5 %) |

<30: 19.35 % 30–40:10.99 % 40–50:14.09 % 50–60:21.98 % 60–70:24.43 % >70:12.09 % |

NA | NA | [61] |

| Hainan (south region) | 2016~2021 | 13.4 |

M. intracellulare (39.49 %) M. chelonae/abscessus (32.91 %) M. avium (7.59 %) |

≤40:8.9 % >40:91.1 % |

NA | NA | [62] |

| Taiwan (south region) | 2000~2012 | 56.9 |

M. avium/intracellulare (41.51 %) M. abscessus (30.81 %) M. fortuitum (13.36 %) |

NA | NA | NA | [63] |

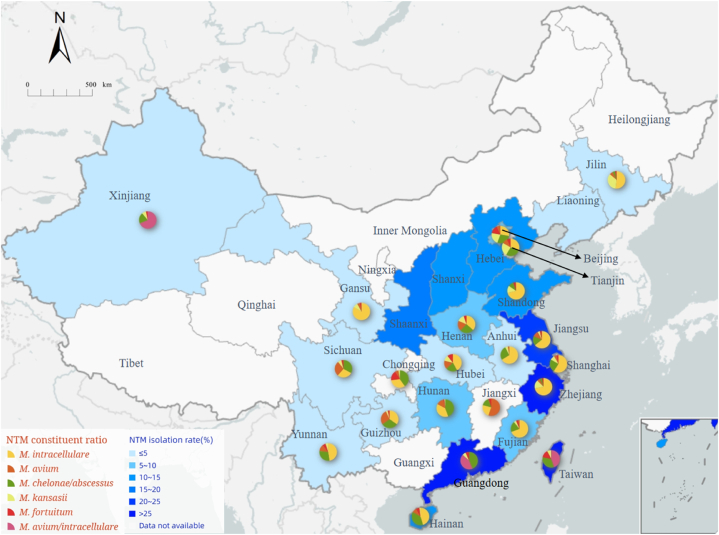

According to Table 2 and Fig. 1, notable differences in NTM isolation rates were observed among provinces, especially between the southern and northern regions. Coastal areas such as Taiwan, Guangdong, Zhejiang, and Jiangsu provinces exhibited the highest NTM isolation rates. Moreover, the isolation rate of NTM in coastal areas was higher than that in inland areas. Overall, M. intracellulare and M. avium/intracellulare emerged as the most common NTM species in China, with isolation rates reaching as high as 70 % in some provinces. Conversely, M. chelonae/abscessus was more prevalent in the south than in the north, while M. kansasii exhibited greater prevalence in the north.

Fig. 1.

Isolation rate and composition of NTM in parts of China.

NTM can be detected not only in respiratory tract specimens but also in extrapulmonary specimens such as ascites, hydrothorax, urine, cerebrospinal fluid, skin/soft tissue, and pericardial effusion [9]. This indicates that NTM extrapulmonary infections include meningitis, pleurisy, pericarditis, and skin diseases. During the epidemiological investigation, sputum was used as the primary NTM sample. Colonized NTM may be present in sputum, such as M. gordonae. Therefore, the calculation of isolation rates often includes contaminating bacteria.

The average age of patients with NTM infections reportedly falls between 50 and 70 years [64]. Table 2 demonstrates that individuals aged >60 years constitute the largest age group among patients with NTM-PD. Hypoimmunity serves as a risk factor for NTM, and certain underlying diseases, such as bronchiectasis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and diabetes, are observed in a proportion of patients listed in Table 2. The clinical symptoms of patients with NTM-PD include cough, expectoration, hemoptysis, and extrapulmonary NTM infections, characterized by myalgia, ulcers, diarrhea, necrotic abscesses, and edematous lesions [9,10]. These symptoms are nonspecific and resemble those of TB [10].

Understanding the epidemiology of NTM aids in the clinical diagnosis of NTM and its subspecies. However, recent data shows compositional differences compared with those reported in previous years [65]. The epidemiological patterns may vary depending on the study period. Therefore, we conducted searches to obtain the most recent data available from various countries and provinces.

4. Detection methods

The detection methods include smears, cultures and molecular methods. Molecular diagnostic techniques include polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based molecular biology, chips, probes and sequencing technologies. Compared with traditional phenotypic and biochemical methods, molecular diagnostic techniques exhibit superior sensitivity, accuracy, and efficiency. Each method has its advantages and disadvantages and is constantly evolving. The following section provides an overview of the identified strains, advantages and disadvantages, the recent advancements, and the commercial Mycobacterium identification kits (Table 3) available for clinical use. The discussion of these aspects offers a more comprehensive understanding of the NTM identification technology used, facilitates the application of appropriate identification methods in clinical settings, and inspires the development of a more rapid, accurate, and efficient identification method that can be applied in clinical and laboratory settings in the future.

Table 3.

Examples of commercial Mycobacterium identification kit.

|

Technique |

Product | Target gene | Manufacturer | Pathogen(s) detected | Detection time | Detection type | Sensitivity, specificity | Concordance | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real-time PCR | AdvanSure™ TB/NTM Detection Kit | MTBC: IS6110 NTM: ITS |

LG Life Sciences | MTB and NTM | 140 min | cultures | NA | 100 % | [66] |

| GENEDIA® MTB/NTM Detection Kit | MTBC: IS6110 NTM: ITS and rpoB |

Green Cross Medical Science Corp | MTB and NTM | 140 min | cultures | NA | 98.8 % | [66] | |

| Real-Q MTB & NTM kit | MTBC: IS6110 NTM: ITS |

BioSewoom, Seoul | MTB and NTM | 135 min | cultures | NA | 98.8 % | [66] | |

| Real Myco-ID® | rpoB | Optipharm | MTBC, M. avium/intracellulare, M. abscessus/massiliense, M. chelonae, M. fortuitum complex, M. ulcerans/marinum, M. kansasii/gastri, M. celatum, M. terrae/nonchromogenicum, M. gordonae/szulgai, and M. mucogenicum | 4 h | cultures | NA | 100 % | [67] | |

| Melting curve analysis | LightCycler® Mycobacterium Detection Kit | 16SrRNA | Roche | M. tuberculosis, M. avium and M. kansasii | 90 min | clinical samples | NA | NA | [68] |

| MeltPro Myco assay (MMCA®) | ITS | Zeesan Biotech | MTBC, M. avium, M. intracellulare, M. absessus, M. chelonae, M. kansasii, M. fortuitum, M. gordonae, M. scrofulaceum/intracellulare, M. malmoense, M. interjectum, M. szulgai, M. marinum/ulcerans, and M. xenopi, M. simiae, M. terrae, M. nonchromogenicum, M. malmoense, M. lentiflavum, M. bovis/BCG |

4 h | clinical samples | NA | NA | [69] | |

| Biochip assay | Mycobacterial Species Identification Kit | 16SrRNA | CapitalBio | M. tuberculosis, M. intracellulare, M. chelonae/abscessus, M. kansasii, M. avium, M. gordonae, M. fortuitum, M. scrofulaceum, M. gilvum, M. terrae, M. phlei, M. nonchromogenicum, M. marinum/ulcerans, M. aurum, M. szulgai/malmoense, M. xenopi, and M. smegmatis | 6 h | clinical samples | 82 %, 99.6 % |

NA | [70] |

| Line Probe assay | INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria V2 assay |

ITS | Innogenetics | MTBC, M. avium, M. intracellulare, M. scrofulaceum, M. kansasii, M. xenopi, M. chelonae, M. gordonae, M. fortuitum complex, M. malmoense, M. genavense, M. simiae, M. smegmatis, M. haemophilum, M. marinum/ulcerans and M. celatum | 2 h | cultures | 100 %, 94.4 % |

NA | [71] |

| GenoType Mycobacterium CM/AS assay | 23SrRNA | Hain Lifescience GmbH | CM: MTBC, M. avium, M. chelonae, M. abscessus, M. fortuitum, M. gordonae, M. intracellulare, M. scrofulaceum, M. interjectum, M. kansasii, M. malmoense, M. marinum/ulcerans, M. peregrinum, M. xenopi AS: M. simiae, M. mucogrnicum, M. goodii, M. celatum, M. smegmatis, M. genavense, M. lentiflavum, M. szulgai, M. phlei, M. heckeshornense, M. haemophilum, M. kansasii, M. ulcerans, M. gastri, M. asiaticum, M. shimoidei |

CM:6 h AS:5 h |

cultures | 93.7~100 %, 100 %. | NA | [72,73] | |

| GenoType Mycobacterium NTM-DR assay | 23SrRNA | Hain Lifescience GmbH |

M. abscessus subsp. abscessus, M. abscessus subsp.massiliense, M. abscessus subsp. Bolletii, M. chelonae, M. avium, M. intercelleulare, M. chimaera |

5 h | cultures | 100 %, 100 % |

100 % | [74] | |

| Speed-oligo Mycobacteria assay | 16SrRNA and ITS | Vircell | MTBC, M. abscessus, M. marinum/ulcerans complex, M. kansasii, M. xenopi, M. intracellulare, M. avium, M. scrofulaceum, M. malmoense, M. gordonae, M. interjectum, M. chelonae, M. fortuitum and M. peregrinum |

2 h30 min | cultures | NA | 93.5 % | [75] | |

| AdvanSure Mycobacteria GenoBlot assay | ITS | LG Life Sciences Inc. | MTBC, M. avium, M. intracellulare, M. scroflaceum, M. abscessus, M. chelonae, M. kansasii, M. szulgai, M. gordonae, M. celatum, M. marinum/ulcerans, M. simiae, M. lentiflavum/genavense, M. xenopi, M. smegmatis, M. malmoense, M. gastri, M. flavescennse, M. vaccae, M. fortuitum complex |

NA | clinical samples | 100 %, 98.5 % |

89.7 % | [76] | |

| PCR-reverse blot hybridization assay | MolecuTech REBA Myco-ID® | rpoB | YD Diagnostics | MTBC, M. avium, M. intracellulare, M. scroflaceum, M. abscessus, M. massilience, M. chelonae, M. fortuitum complex, M. marinum/ulcerans, M. kansasii, M. genavense/simiae, M. celatum, M. terrae/nonchromogenicum, M. gordonae, M. szulgai, M. mucogenicum, and M. aubagnense |

NA | cultures | NA | 94.3 % | [67,77] |

| PCR-REBA Myco-ID | 16S rRNA | Yaneng BioSciences | MTB, M. smegmatis, M. intracellulare, M. kansasii, M. chelonae, M. marinum, M. fortuitum, M. terrae, M. nonchromogenicum, M. avium, M. scrofulaceum, M. abscessus, M. xenopi, M. gilvum, M. phlei, M. triviale, M. gordonae, M. gastri, M. vaccae, M. szulgai, M. diernhoferi, M. simiae | 4 h | clinical samples | 99 %, 100 % |

NA | [78] | |

| Myco-Panel | NA | Medical & Biological Laboratories Co., Ltd. | M. tuberculosis var. tuberculosis, M. tuberculosis var. BCG, M. avium, M. intracellulare, M. kansasii, M. abscessus subsp. abscessus, M. abscessus subsp. bolletii, M. abscessus subsp. massiliense, M. chelonae, M. gordonae, M. xenopi, M. fortuitum, M. szulgai, M. marinum/ulcerans, M. scrofulaceum, M. simiae, M. asiaticum, M. lentiflavum, M. nonchromogenicum, M. shimoidei, M. terrae, M. shinjukuense, M. mucogenicum, M. peregrinum, M. triviale, M. malmoense, M. chimaera, and M. heckeshornense | NA | clinical samples and cultures |

NA | 83.1 % | [79] | |

| DNA-DNA hybridization test | Genotype CM Direct® (GTCMD) | NA | Bruker, Billerica | MTBC, M. avium, M. intracellulare, M. absessus complex, M. chelonae, M. kansasii, M. fortuitum group, M. gordonae, M. scrofulaceum/intracellulare, M. malmoense, M. interjectum, M. szulgai, M. marinum/ulcerans, and M. xenopi | NA | clinical samples | 89.2 %, 81.5 % |

NA | [80] |

| VisionArray MyCo®(VAM) 2.0 |

NA | ZytoVision, | MTBC, M. avium complex, M. chimaera, M. absessus complex, M. chelonae, M. kansasii, M. fortuitum, M. gordonae, M. malmoense, M. scrofulaceum/parascrofulaceum, M. haemophilum, M. genavense, M. marinum/ulcerans, M. smegmatis, M. simiae, and M. xenopi | NA | clinical samples | 73.0 %, 96.3 % |

NA | [80] |

4.1. Acid-fast bacilli smear

Mycobacteria contain mycolic acids in their cell walls and acid-fast bacilli (AFB) can be visualized under a light microscope as reddish-pink bacilli [81]. Although, smears can identify mycobacteria, they cannot distinguish between MTB and NTM. AFB smears offer rapid and cost-effective identification but exhibit poor specificity [81]. A previous study demonstrated the sensitivities of AFB smears for MTB and NTM were 51.6 % and 53.1 %, respectively [82].

4.2. NTM culture

Various methods are available for pathogen culture, with common clinical approaches including the BACTEC MGIT 960 method and the Lowenstein-Jensen (L-J) culture medium, which can be used for preliminary identification. Mature colonies of rapidly growing mycobacteria (RGM) typically appear on solid media within 7 days, while those of slowly growing mycobacteria (SGM) may take longer than 7 days to manifest [83]. MGIT instruments detect growth by reading the fluorescent indicator in MGIT tubes, which fluoresce as bacterial respiration occurs and O2 is depleted. The culture time of liquid medium was shorter than that in the solid medium; however, the liquid medium could not distinguish between mixed infections [81]. Some studies involved incubating both solid and liquid cultures for 6–8 weeks after inoculation [84]. In addition, specimens should be centrifuged, digested, or decontaminated prior to inoculation into the medium. This process serves to minimize the contaminating bacteria and reduce NTM recovery [85]. Ditommaso et al. reported a new culture method utilizing an NTM Elite agar, which does not require a decontamination step. This novel method successfully detected NTM in 27.7 % (30/108) of water samples analyzed [86].

4.3. Multiplex PCR

Multiplex PCR (mPCR) involves adding two or more pairs of primers to the same mPCR system to amplify multiple nucleic acid fragments simultaneously. Singh et al. investigated a one-step mPCR method for detecting Mycobacterium, including MAC, M. kansaii, M. abscessus based on 16SrRNA, and ITS [87]. Recently, Kim et al. developed a two-step mPCR method to identify the causative agents of major mycobacterial infections. MTB, M. intracellulare, and M. avium were distinguished in the first mPCR step, while M. kansasii, M. fortuitum, M. abscessus, and M. massiliense were distinguished in the second step [88]. Shin et al. conducted a study employing a five-target mPCR to effectively distinguish M. avium complex species and subspecies. This assay relied on the amplification of specific genetic markers such as 16SrRNA, IS900, IS901, IS1311, and DT1 [89]. Chae et al. developed a one-step mPCR assay for the differential detection of Mycobacterium species, MTBC, MTB, the MTB Beijing family, M. avium, M. intracellulare, M. abscessus, M. massiliense, and M. kansaii. This assay relied on the amplification of specific genetic markers such as 16SrRNA, rv0577, RD9, mtbk_20680, IS1311, DT1, mass_3210, and mkan_rs12360 [90]. Multiplex PCR is a simple, rapid, convenient, and reliable technique for identifying NTM at a relatively low cost. It has the advantage of being able to detect mixed infection cases of MTB and NTM. Many commercial kits utilize multiplex PCR amplification, with the PCR product combined with a probe, thereby significantly reducing gene fragment amplification time. This method can be used to identify the most common NTM in pulmonary specimens. However, multiplex PCR does not simply mix multiple pairs of specific primers into a single reaction system. Owing to the incompatibility of amplification conditions among multiple targets, the formation of dimers between primers, and mutual inhibition, the practical application of multiplex PCR is subject to many limitations.

4.4. Real-time PCR

Real-time PCR was employed to monitor the entire PCR amplification process using a fluorescence signal, enabling real-time observation of the PCR dynamics. In a study by Franciele Costa Leite Morais, the utilization of quantitative PCR to detect NTM species using 16S rRNA as a target exhibited the potential to swiftly and effectively differentiate NTMs from M. tuberculosis [91]. An Australian laboratory developed a real-time PCR method targeting IS2404 for the direct detection of M. ulcerans [92]. Kim et al. developed a multiplex real-time PCR assay capable of directly detecting 20 mycobacterial species in clinical specimens, with a sensitivity and a specificity for detecting NTM isolates of 53.3 % and 99.9 %, respectively [93]. Numerous commercial kits based on real-time PCR, such as GENEDIA® MTB/NTM Detection Kit, AdvanSure TB/NTM Detection Kit, and Real-Q MTB/NTM Detection Kit, are used to distinguish between MTB and NTM [66]. In addition, Real Myco-ID® (Optipharm) was developed for the rapid and accurate detection and identification of 17 Mycobacterium species (Table 3) [67]. Real-time PCR is a highly sensitive, specific, and rapid molecular assay. A closed PCR system reduces the risk of contamination and the probability of false-positive results [66]. However, the presence of PCR inhibitors in samples may reduce the sensitivity of real-time PCR.

4.5. Melting curve analysis

The principle of melting curve analysis involves heating the PCR products to generate a fluorescence signal curve, from which the melting curve is obtained. The melting temperature corresponding to the peak value of the melting curve is the melting temperature value of double-stranded DNA. This method is primarily based on real-time PCR. Keerthirathne et al. conducted a real-time mPCR assay in two separate reactions. Reaction I utilized primers specific for MTB and MAC, while reaction II employed primers specific for the M. chelonae/abscessus group and M. fortuitum, aiding in the identification of RGM and SGM, respectively, by obtaining the melting curve [94]. The LightCycler® Mycobacterium Detection Kit can detect M. tuberculosis, M. avium, and M. kansasii by performing a melting curve analysis on the LightCycler® 2.0 (Roche Diagnostics, Germany) [68]. Recently, a system known as the MeltPro Myco assay has been developed, capable of identifying 19 species of mycobacteria (Table 3). The test sample can be a liquid medium stored in the laboratory or institute, or sputum samples with positive acid-fast staining [69]. This method offers advantages such as rapidity, high accuracy, sensitivity, and high throughput; reduces the risk of contamination; and detects mixed infections [69]. However, in clinical detection, various influencing factors such as primers, probes, and Taq enzymes can affect the curve.

4.6. Biochip assay (DNA microarray chip)

The principle of a biochip assay involves arranging various DNA probes on a carrier, such as a glass sheet or fiber membrane, using microarray technology. These probes are then hybridized with labeled samples to obtain the hybridization signal intensity of each probe molecule. The Mycobacterium identification array kit (CapitalBio, Beijing, China) is a gene chip product designed for Mycobacterium species identification in China capable of identifying 17 common species or groups (Table 3) [70]. Compared with traditional methods, DNA microarray chips have the characteristics of rapidity, reliable results, good repeatability, and high throughput. This method enables strain identification within 6–8 h, providing a timely and accurate laboratory basis for patients to receive appropriate treatment [82]. However, the reagent costs approximately US$9.8 for the identification of a single strain, and it cannot distinguish between M. abscessus and M. chelonae, M. marinum and M. ulcerans [82].

4.7. Line probe assay

Line probe assay (LPA) operates on the principle of reverse hybridization of PCR products with complementary probes, with the results displayed using enzyme-linked immunocolorimetry. The different line probe assays utilized the INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria v2 assay (Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium), GenoType Mycobacterium CM/AS and NTM-DR (Hain Lifescience GmbH, Nehren, Germany), Speed-oligo Mycobacteria assay (Vircell, Spain), and AdvanSure Mycobacteria GenoBlot assay (LG Life Sciences Inc., Hour, Korea). Only GenoType Mycobacterium NTM-DR could identify the M. abscessus subspecies [95]. LPA offers several advantages such as rapidity, high accuracy, a wide range of identification, and low technical requirements [96]. In addition, multiple strains can be identified using a single probe, and NTM in mixed cultures can be detected simultaneously. However, due to the heterogeneity of the probe-binding region resulting in unsuccessful hybridization, each detection method may yield false-positive or false-negative results. LPA also carries the risk of contamination of amplified products, has limited types of identification, involves relatively complex operations, and is greatly influenced by the proficiency of the operator.

4.8. PCR-reverse blot hybridization assay

The principle of PCR-reverse blot hybridization assay (PCR-REBA) involves spotting the probe on the nylon membrane, hybridizing it with the PCR amplification products, and determining whether the probe hybridizes with the DNA fragment based on the color of the specific position of the membrane strip. The common kits used for this purpose are REBA Myco-ID® (YD Diagnostics, Yongin, South Korea) and PCR-REBA Myco-ID (Yaneng BIOsciences, Shenzhen). This method is rapid, inexpensive, and user-friendly, and suitable for use with clinical specimens [78]. However, it could not further classify M. abscessus subspecies. The PCR-REBA Myco-ID has not been widely adopted into the workflow of many mycobacterial laboratories [78]. Recently, a PCR-reverse sequence-specific oligonucleotide probe method based on the mycobacterial detection panel test was developed for the rapid identification of 28 mycobacterial species and subspecies (Table 3). This method can be utilized with clinical respiratory samples and mycobacterial suspensions to distinguish the M. abscessus subspecies [79].

4.9. DNA-DNA hybridization test

The basic principle of the DNA-DNA hybridization test involves the denaturation and renaturation of nucleic acid molecules to form hybrid double-stranded DNA fragments from different sources according to complementary base pairing. The common kits used for this test include Genotype CM Direct® (GTCMD) (Bruker, Billerica, Ma, USA) and VisionArray MyCo® (VAM) (ZytoVision, Bremerhaven, Germany). In a study by Hans-Ulrich Schildhaus [80], GTCMD showed sensitivity and specificity rates of 89.2 % and 81.5 %, respectively, while VAM demonstrated rates of 73.0 % and 96.3 %. These kits can be used to identify mycobacteria directly from clinical specimens, but cannot identify M. abscessus subspecies. However, only a few published studies have explored these two products.

4.10. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) operates by comparing spectral data from extracted proteins to a database. Mycobacterial species were identified by MALDI-TOF MS according to the reference spectra contained in the database. This method is fast and reliable, making it suitable for routine and high-throughput use in clinical laboratories. A previous study showed that MALDI-TOF MS accurately identified 97 % and 77 % of the strains from L-J and MGIT media, respectively [97]. However, mycobacteria require additional processing before analysis by MALDI-TOF MS due to biosafety concerns and their structural characteristics [98]. Identifying NTM strains using MALDI-TOF MS poses challenges due to their slow growth rate, limited number of ribosomal proteins, thick cell walls, and hydrophobicity. In addition, mass spectrometers are expensive. Although MALDI-TOF MS can distinguish between M. abscessus and M. chelonae, it cannot distinguish M. abscessus subspecies [99]. Upgrading the database can significantly improve the ability to identify NTM strains. The accuracy of the MALDI-TOF MS using the upgraded My-coDB v2.0-beta database was notably superior to that reported in previous studies [84].

Rindi et al. showed that MALDI-TOF MS can be used as a routine diagnostic tool to identify mycobacteria directly from positive primary MGIT cultures in only 30 min [100]; however, the study has some limitations, including the small sample size. Previous studies have shown that liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry can be used to identify clinically relevant M. abscessus complex organisms, with higher analytical performance compared with MALDI-TOF [99]. Nucleic MALDI-TOF MS detection integrates the high sensitivity of PCR technology, high throughput of chip technology, and high precision of MALDI-TOF MS, enabling the amplification of multiple genes used for analyzing single nucleotide polymorphisms, gene mutations, DNA methylation, and copy number identification. Li et al. demonstrated that the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of nucleotide MALDI-TOF MS for mycobacterial identification were 96.91 %, 100 %, and 97.22 %, respectively [101].

4.11. Sanger sequencing

This method can identify bacteria at the species level by analyzing the differences in homologous DNA sequence composition. The sequences commonly used for the identification of Mycobacterium species include 16SrRNA, 16S-23SrRNA (ITS), rpoB, and hsp65. Among these, RpoB is widely utilized [102], while Hsp65 demonstrates superior discriminatory ability compared with rpoB and ITS. However, 16S rRNA is not suitable for distinguishing closely related strains, such as pathogenic M. kansasii and non-pathogenic M. gastri, M. chelonae and M. abscessus, and cannot distinguish between MTB and M. avium [103]. Currently, ERM (41) [104], argH, and cya gene markers [105] are used to identify the M. abscessus subspecies (M. abscessus subsp. abscessus, M. abscessus subsp. massiliense, and M. abscessus subsp. bolletii). Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) defines different strains of bacteria by analyzing the sequence differences in several conserved internal segments that encode host genes. Diricks et al. developed a robust cgMLST scheme for the emerging pathogen M. abscessus, which delineates the MAB population structure, outbreaks, and within-patient diversity. Using open-source software or web-based tools, the whole-genome sequencing-based cgMLST approach has proven to be a powerful tool for high-resolution molecular epidemiological investigation of MAB strains [106]. Kolb et al. applied MLST technology to type M. avium strains of human, animal, and environmental origins and examined the degree of genetic diversity [107]. An important advantage of this methodology is its high level of reproducibility and the possibility of digitalizing the data for easy worldwide comparison [107].

Some researchers have developed an open-source software for the Sanger sequencing-based identification of NTM species, named SnackNTM. SnackNTM can analyze multiple samples simultaneously. In the processing time comparison test, the analysis and reporting of 30 samples, which required 150 min manually, were completed in just 40 min using SnackNTM [108].

4.12. Whole-genome sequencing

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) is a method that uses enzymatic hydrolysis or mechanical force to fragment gene sequences, and then sequences these fragments using bioinformatic methods to assemble the sequenced sequences from scratch into a complete genome. WGS of pathogenic microorganisms based on next-generation sequencing technology has been widely used in the detection of infectious diseases. It aids in diagnosing infections with two or more mixed NTM, and is also commonly used to identify rarely isolated species and understand resistance mechanisms by obtaining complete genome sequences [109]. WGS also allows the identification of NTMs at the clone level to determine the nature of the ongoing disease (relapse/reinfection) [110]. However, due to its high cost and complexity, it is not suitable for large-scale applications [111].

4.13. Mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit-variable number tandem repeat typing

This technique relies on analyzing the number of tandem repeats within a specific region of the genome. These specific regions, called mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units (MIRUs), contain a variable number of repeat sequences (variable number of tandem repeats, VNTRs) that may differ between strains. Owing to its high throughput, good repeatability, and easy standardization, the MIRU-VNTR classification method is widely used in molecular epidemiological studies of TB, especially for tracking transmission chains and exploring the spread and evolution of strains [112]. Zsuzsanna Rónai applied eight loci, MIRU-VNTR, contributing greatly to our knowledge of the genetic diversity of M. avium subspecies [113]. In a study by Kalvisa, MIRU-VNTR genotyping revealed 13 distinct genotypes, allowing the efficient discrimination of M. avium subspecies [114]. Understanding the impact of homoplasy among widely used repeating unit genotyping markers, such as MIRU-VNTR, is important for reducing the probability of misidentification of M. avium and other monomorphic and slowly growing mycobacteria.

5. Limitations and prospects

To the best of our knowledge, this was the only review of epidemiology and identification technology that presents the most recent epidemiological data and species distribution of NTM isolates in several countries and provinces of China, along with a comprehensive list of commercial Mycobacterium identification kits. In comparison to other similar studies, our research offered a more extensive examination of the current landscape. Currently, there are persistent challenges in epidemiological research on NTM. Only limited epidemiological studies have been conducted in the Philippines, Bangladesh, and other countries as well as in certain areas of northern and western China, resulting in a lack of up-to-date statistical data. Maintaining consistency in study periods across different regions posed challenges, potentially leading to errors in the comparative analyses. Moreover, some studies have overlooked the crucial clinical features of NTM diseases, contributing to gaps in our understanding of the epidemiology. NTM identification involves two to three steps: strain culture, nucleic acid extraction, and technical testing. Some studies involved incubating both solid and liquid cultures for 6–8 weeks after inoculation [84]. Standardized nucleic acid extraction procedures are crucial to ensure accuracy in testing. In the biochip assay, a matching nucleic acid extraction solution (Capital Bio, Beijing, China) was used to extract nucleic acids [70]. Similarly, the Real Myco-ID® kit has the matched DNA extraction solution (Optipharm) [67]. The conventional method for extracting DNA directly from cultures typically involves the use of conventional cetyltrimethylammonium bromide [87,89,91]. The direct extraction of nucleic acids from sputum specimens requires two steps: cell lysis and DNA purification. The methods include phenol-chloroform based methods, freeze-thaw-boiling, detergent-based procedures, Chelex 100 resins (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), QIAmp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), Roche Cobas TNAI-AMPLI-Prep, and the Promega DNA IQ Casework sample kit with Maxwell 16 robot [115]. The characteristics of various technical tests are described above. For example, MS is the fastest method for strain identification, but requires strain culture; therefore, the entire process is time-consuming. The Mycobacteria Identification Array Kit, MeltPro Myco assay, GTCMD and VAM enable direct testing on specimens, significantly reducing detection time. In the future, identification techniques will be developed to directly identify samples without the need for culture, with fewer influencing factors, higher identification accuracy and sensitivity, and a wider range of species/subspecies.

6. Conclusions

This review discussed the epidemic status and laboratory identification methods of NTM. It underscored the variability of NTM epidemiology across regions, emphasizing the importance of timely regional epidemiological investigation to understand and address evolving trends. Updates and advancements in identification methods are ongoing, and faster, more convenient, and more accurate methods will be developed in the future to enhance NTM detection.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Zhejiang Provincial Medical and Health Technology Project (grant.2023KY168).

Data availability statement

Data associated with the study were obtained from the relevant literature, the references have been marked. And no additional data was used for the research described in the review article. Chinese libraries: Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang.

Ethics statement

Not applicable.

Abbreviations list:

| NTM | Non-tuberculous Mycobacteria |

| MTB | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| MTBC | Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex |

| NTM-PD | Non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease |

| MAC | M. avium complex |

| MABC | M. abscessus complex |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| AIDS | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| AFB | Acid-fast bacilli |

| RGM | Rapidly growing mycobacteria |

| SGM | Slowly growing mycobacteria |

| LPA | Line probe assay |

| mPCR | Multiplex PCR |

| PCR-REBA | PCR-reverse blot hybridization assay |

| MALDI-TOF MS | Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry |

| MLST | Multilocus sequence typing |

| WGS | Whole genome sequencing |

| MIRU-VNTR | Mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit-variable number tandem repeat typing |

| L-J | Lowenstein-Jensen |

| NA | Data not available in article |

| Ref. | Reference |

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Nuo Xu: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation. Lihong Li: Data curation. Shenghai Wu: Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Haworth C.S., Banks J., Capstick T., et al. British Thoracic Society guidelines for the management of non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD) Thorax. 2017;72(Suppl 2):ii1–ii64. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210927. http://10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riojas M.A., McGough K.J., Rider-Riojas C.J., et al. Phylogenomic analysis of the species of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex demonstrates that Mycobacterium africanum, Mycobacterium bovis, Mycobacterium caprae, Mycobacterium microti and Mycobacterium pinnipedii are later heterotypic synonyms of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018;68(1):324–332. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002507. http://10.1099/ijsem.0.002507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gardini G., Ori M., Codecasa L.R., et al. Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial infections and environmental factors: a review of the literature. Respir. Med. 2021;189 doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106660. http://10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falkinham J.O. Nontuberculous mycobacteria in the environment. Tuberculosis. 2022;137 doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2022.102267. http://10.1016/j.tube.2022.102267 3rd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mortaz E., Moloudizargari M., Varahram M., et al. What immunological defects predispose to non-tuberculosis mycobacterial infections? Iran. J. Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 2018;17(2):100–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurz S.G., Zha B.S., Herman D.D., et al. Summary for clinicians: 2020 clinical practice guideline summary for the treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(9):1033–1039. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-222CME. http://10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-222CME [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jamal F., Hammer M.M. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Radiol. Clin. 2022;60(3):399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2022.01.012. http://10.1016/j.rcl.2022.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koh W.J. Nontuberculous mycobacteria-overview. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017;5(1) doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.tnmi7-0024-2016. http://10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0024-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gopalaswamy R., Subbian S., Shanmugam S., et al. Recent developments in the diagnosis and treatment of extrapulmonary non-tuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Int. J. Tubercul. Lung Dis. 2021;25(5):340–349. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.21.0002. http://10.5588/ijtld.21.0002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gopalaswamy R., Shanmugam S., Mondal R., et al. Of tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections - a comparative analysis of epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. J. Biomed. Sci. 2020;27(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s12929-020-00667-6. http://10.1186/s12929-020-00667-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Özkarataş M.H., Arslan N., Esen N., et al. [Evaluation of antimicrobial susceptibilities of rapidly growing mycobacteria] Mikrobiyoloji Bulteni. 2023;57(2):220–237. doi: 10.5578/mb.20239917. http://10.5578/mb.20239917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akrami S., Dokht Khosravi A., Hashemzadeh M. Drug resistance profiles and related gene mutations in slow-growing non-tuberculous mycobacteria isolated in regional tuberculosis reference laboratories of Iran: a three year cross-sectional study. Pathog. Glob. Health. 2023;117(1):52–62. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2022.2049029. http://10.1080/20477724.2022.2049029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park J.H., Shin S., Kim T.S., et al. Clinically refined epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease in South Korea: overestimation when relying only on diagnostic codes. BMC Pulm. Med. 2022;22(1):195. doi: 10.1186/s12890-022-01993-1. http://10.1186/s12890-022-01993-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun Q., Yan J., Liao X., et al. Trends and species diversity of non-tuberculous mycobacteria isolated from respiratory samples in northern China, 2014-2021. Front. Public Health. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.923968. http://10.3389/fpubh.2022.923968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoefsloot W., van Ingen J., Andrejak C., et al. The geographic diversity of nontuberculous mycobacteria isolated from pulmonary samples: an NTM-NET collaborative study. Eur. Respir. J. 2013;42(6):1604–1613. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00149212. http://10.1183/09031936.00149212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar K., Loebinger M.R. Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: clinical epidemiologic features, risk factors, and diagnosis: the nontuberculous mycobacterial series. Chest. 2022;161(3):637–646. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.10.003. http://10.1016/j.chest.2021.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Z.X., Cherng B.P.Z., Sng L.H., et al. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of non-tuberculous mycobacteria diseases in Singapore with a focus on pulmonary disease, 2012-2016. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019;19(1):436. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-3909-3. http://10.1186/s12879-019-3909-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim K.J., Oh S.H., Jeon D., et al. Isolation and antimicrobial susceptibility of nontuberculous mycobacteria in a tertiary hospital in Korea, 2016 to 2020. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2023;86(1):47–56. doi: 10.4046/trd.2022.0115. http://10.4046/trd.2022.0115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lou H., Zou A., Shen X., et al. Clinical features of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease in the yangtze river delta of China: a single-center, retrospective, observational study. Trav. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023;8(1) doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed8010050. http://10.3390/tropicalmed8010050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morimoto K., Hasegawa N., Izumi K., et al. A laboratory-based analysis of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in Japan from 2012 to 2013. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(1):49–56. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201607-573OC. http://10.1513/AnnalsATS.201607-573OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thangavelu K., Krishnakumariamma K., Pallam G., et al. Prevalence and speciation of non-tuberculous mycobacteria among pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis suspects in South India. J Infect Public Health. 2021;14(3):320–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.12.027. http://10.1016/j.jiph.2020.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma S.K., Sharma R., Singh B.K., et al. A prospective study of non-tuberculous mycobacterial disease among tuberculosis suspects at a tertiary care centre in north India. Indian J. Med. Res. 2019;150(5):458–467. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_194_19. http://10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_194_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suresh P., Kumar A., Biswas R., et al. Epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacterial infection in tuberculosis suspects. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021;105(5):1335–1338. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.21-0095. http://10.4269/ajtmh.21-0095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonnet M., San K.C., Pho Y., et al. Nontuberculous mycobacteria infections at a provincial reference hospital, Cambodia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017;23(7):1139–1147. doi: 10.3201/eid2307.170060. http://10.3201/eid2307.170060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karamat A., Ambreen A., Ishtiaq A., et al. Isolation of non-tuberculous mycobacteria among tuberculosis patients, a study from a tertiary care hospital in Lahore, Pakistan. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021;21(1):381. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06086-8. http://10.1186/s12879-021-06086-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Harbi A., Al-Jahdali H., Al-Johani S., et al. Frequency and clinical significance of respiratory isolates of non-tuberculous mycobacteria in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Clin. Res. J. 2016;10(2):198–203. doi: 10.1111/crj.12202. http://10.1111/crj.12202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarashi S., Sakhaee F., Masoumi M., et al. Molecular epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacteria isolated from tuberculosis-suspected patients. Amb. Express. 2023;13(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s13568-023-01557-4. http://10.1186/s13568-023-01557-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saptawati L., Primaningtyas W., Dirgahayu P., et al. Characteristics of clinical isolates of nontuberculous mycobacteria in Java-Indonesia: a multicenter study. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2022;16(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0011007. http://10.1371/journal.pntd.0011007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grigg C., Jackson K.A., Barter D., et al. Epidemiology of pulmonary and extrapulmonary nontuberculous mycobacteria infections at 4 US emerging infections program sites: a 6-month pilot. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023;77(4):629–637. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciad214. http://10.1093/cid/ciad214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carneiro M.D.S., Nunes L.S., David S.M.M., et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in a high tuberculosis incidence setting in Brazil. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2018;44(2):106–111. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37562017000000213. http://10.1590/s1806-37562017000000213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schiff H.F., Jones S., Achaiah A., et al. Clinical relevance of non-tuberculous mycobacteria isolated from respiratory specimens: seven year experience in a UK hospital. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):1730. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37350-8. http://10.1038/s41598-018-37350-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blanc P., Dutronc H., Peuchant O., et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections in a French hospital: a 12-year retrospective study. PLoS One. 2016;11(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168290. http://10.1371/journal.pone.0168290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Przybylski G., Bukowski J., Kowalska W., et al. Trends from the last decade with nontuberculous mycobacteria lung disease (NTM-LD): clinicians' perspectives in regional center of pulmonology in bydgoszcz, Poland. Pathogens. 2023;12(8) doi: 10.3390/pathogens12080988. http://10.3390/pathogens12080988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vande Weygaerde Y., Cardinaels N., Bomans P., et al. Clinical relevance of pulmonary non-tuberculous mycobacterial isolates in three reference centres in Belgium: a multicentre retrospective analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019;19(1):1061. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4683-y. http://10.1186/s12879-019-4683-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gharbi R., Mhenni B., Ben Fraj S., et al. Nontuberculous mycobacteria isolated from specimens of pulmonary tuberculosis suspects, Northern Tunisia: 2002-2016. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019;19(1):819. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4441-1. http://10.1186/s12879-019-4441-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sookan L., Coovadia Y.M. A laboratory-based study to identify and speciate non-tuberculous mycobacteria isolated from specimens submitted to a central tuberculosis laboratory from throughout KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 2014;104(11):766–768. doi: 10.7196/samj.8017. http://10.7196/samj.8017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aliyu G., El-Kamary S.S., Abimiku A., et al. Prevalence of non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections among tuberculosis suspects in Nigeria. PLoS One. 2013;8(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063170. http://10.1371/journal.pone.0063170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spaulding A.B., Lai Y.L., Zelazny A.M., et al. Geographic distribution of nontuberculous mycobacterial species identified among clinical isolates in the United States, 2009-2013. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(11):1655–1661. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201611-860OC. http://10.1513/AnnalsATS.201611-860OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kamada K., Yoshida A., Iguchi S., et al. Geographical distribution and regional differences in 532 clinical isolates of rapidly growing mycobacterial species in Japan. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):4960. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-84537-7. http://10.1038/s41598-021-84537-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang X.Y., Zhang J., Yi J.L., et al. Comparison of the epidemiological characteristics of nontuberculous mycobacteria in Beijing, 2009 and 2019. Capital Journal of Public Health. 2021;15(6):333–337. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou H.J., Wu M., Guo M.R., et al. Distribution and drug resistance of non-tuberculous Mycobacteria in Tianjin, 2018-2019. Shandong Med. J. 2021;61(9):77–79. http://10.3969/j.issn.1002-266X.2021.09.020 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao F., Zhou Y.L. Identification analysis of nontuberculous mycobacteria in Jilin region. Chinese Health Care. 2022;40(11):35–37. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Y.F., Song Q.S. Research of epidemiology and clinical characteristics of patients with nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease in Dalian. Chinese Journal of the Frontiers of Medical Science (Electronic Version) 2023;15(8):28–32. http://10.12037/YXQY.2023.08-04 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feng B.B., Jin F., Jing H., et al. Identification and drug resistance of 439 clinical isolates of non-tuberculosis mycobacterium in Shandong. Chin J Antituberc. 2021;43(5):516–520. http://10.3969/j.issn.1000-6621.2021.05.019 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang S.H., Chang W.J., Su R.Y., et al. Identification and drug resistance analysis of 363 strains of nontuberculous mycobacteria in Henan Province. Chin. J. Zoonoses. 2023;39(2):124–130. http://10.3969/j.issn.1002-2694.2022.00.193 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li J., Guo L., Bai G.H., et al. Species distribution and spread of non-tuberculous mycobacteria in patients of shaanxi provincial tuberculosis prevention and control hospital, 2019-2021. Dis Surveill. 2023;38(9):1039–1042. http://10.3784/jbjc.202302170048 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang X., Cai J., Jiang Y., et al. Species identification on 43 clinical non-tuberculosis Mycobacteria isolates from Gansu Province, China. Chin. J. Zoonoses. 2017;33(2):173–177. http://10.3969/j.issn.1002-2694.2017.02.015 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Q., Wu L.Z., Li J.Y., et al. Xinjiang region in 2009-2011 the mycobacterium tuberculosis drug sensitivity test results. J Pract Med. 2012;28(22):3827–3829. http://10.3969/j.issn.1006-5725.2012.22.060 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang H.Z., Chen Y.K., Yan X.F., et al. Species identification of prevailing non-tuberculosis mycobacteria and analysis of demographic characteristics of patients in Chongqing. China Trop. Med. 2019;19(4):330–334. http://10.13604/j.cnki.46-1064/r.2019.04.07 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luo J., Yu Q.J., Lin Y.L., et al. Clinical characteristics of nontuberculous Mycobacterium infection cases in sichuan, China in 2016–2021: a retrospective study. J. Sichuan Univ. 2022;53(5):890–895. doi: 10.12182/20220960503. http://10.12182/20220960503 (in Chinese) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hu X.H., Han Y., Zhuang Q., et al. Epidemic characteristics of non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection in Yichang area by fluorescence polymerase chain reaction melting curve method. Chin. J. Infect. Control. 2023;22(8):939–944. http://10.12138/j.issn.1671-9638.20234121 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mei L., Liu S.S., Lin W.H., et al. Analysis of strain distribution, clinical characteristics and drug resistance of non-tuberculous Mycobacterium pulmonary disease in Anhui Chest Hospital. Chin. J. Antibiot. 2023;48(11):1288–1294. http://10.3969/j.issn.1001-8689.2023.11.011 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang H.X., Huang J., Xiao Y.Y., et al. Distribution and drug resistance analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and nontuberculosis mycobacteria in Nanjing from 2017 to 2020. Infect Dis Info. 2022;35(3):259–263. http://10.3969/j.issn.1007-8134.2022.03.015 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Y.Y., Hou D.N., Wang S.Z., et al. Identification and clinical analysis of nontuberculous mycobacteria lung disease. J Microbes Infect. 2020;15(3):172–178. http://10.3969/j.issn.1673-6184.2020.03.006 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu F., Chen X., Ji Z.K., et al. Prevalence of Nontuberculous mycobacteria in hangzhou during 2009-2014. Chin. J. Microecol. 2016;28(7):808–810. http://10.13381/j.cnki.cjm.201607015 815. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lin J., Zhao Y., Dai Z.S., et al. Identification and analysis of 261 strains of non-tuberculous mycobacteria in Fujian Province. Chinese Journal of Antituberculosis. 2021;43(6):590–595. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ouyang G.Q., Chen S.S., Xiao Z.K. Analysis of clinical characteristics between patients with non-tuberculosis mycobacterial pulmonary disease and pulmonary tuberculosis. Chin. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021;20(11):774–779. http://10.7507/1671-6205.202012053 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li W.B., Hu P.L., Chen Z.N., et al. Identification and epidemiological characteristics of 525 strains of nontuberculous mycobacteria isolated from a Hunan clinic. Chin. J. Zoonoses. 2022;38(5):417–422. http://10.3969/j.jssn.1002-2694.2022.00.050 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Y.Y., Ou W.Z., Xia M.N., et al. Prevalence analysis of non-tuberculosis Mycobacterium in a hospital in guiyang. J. Guiyang Med. Coll. 2017;42(3):322–326. http://10.19367/j.cnki.1000-2707.2017.03.017 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen T., Xu L., Yang H.J., et al. Analysis of epidemic and pathogenic spectrum on non-tuberculous mycobacteria strains of Yunnan. China Trop. Med. 2018;18(9):863–865. http://10.13604/j.cnki.46-1064/r.2018.09.01 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen H., Hu J.X., Chen P.R., et al. Epidemic status and distribution characteristics of non‐tuberculous mycobacteria in Guangzhou, 2018-2019. Journal of Molecular Imaging. 2021;44(2):378–382. http://10.12122/j.issn.1674-4500.2021.02.32 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhong Y.T., Chen Z.L., Wang J.Y., et al. Species identification of non-tuberculous Mycobacteria from patients with pulmonary infection in Hainan. Dis Surveill. 2022;37(8):1053–1058. http://10.3784/jbjc.202203070086 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chien J.Y., Lai C.C., Sheng W.H., et al. Pulmonary infection and colonization with nontuberculous mycobacteria, Taiwan, 2000-2012. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20(8):1382–1385. doi: 10.3201/eid2008.131673. http://10.3201/eid2008.131673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Verma A.K., Arora V.K. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections in geriatric patients-A neglected and emerging problem. Indian J. Tubercul. 2022;69(Suppl 2):S235–s240. doi: 10.1016/j.ijtb.2022.10.010. http://10.1016/j.ijtb.2022.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zweijpfenning S.M.H., Ingen J.V., Hoefsloot W. Geographic distribution of nontuberculous mycobacteria isolated from clinical specimens: a systematic review. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018;39(3):336–342. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1660864. http://10.1055/s-0038-1660864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jung Y.J., Kim J.Y., Song D.J., et al. Evaluation of three real-time PCR assays for differential identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and nontuberculous mycobacteria species in liquid culture media. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016;85(2):186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.03.014. http://10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang H.Y., Kim H., Kim S., et al. Performance of a real-time PCR assay for the rapid identification of Mycobacterium species. J. Microbiol. 2015;53(1):38–46. doi: 10.1007/s12275-015-4495-8. http://10.1007/s12275-015-4495-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Omar S.V., Roth A., Ismail N.A., et al. Analytical performance of the Roche LightCycler® Mycobacterium Detection Kit for the diagnosis of clinically important mycobacterial species. PLoS One. 2011;6(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024789. http://10.1371/journal.pone.0024789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu Y., Liang B., Du C., et al. Rapid identification of clinically relevant Mycobacterium species by multicolor melting curve analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019;57(1) doi: 10.1128/JCM.01096-18. http://10.1128/jcm.01096-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fang H., Shangguan Y., Wang H., et al. Multicenter evaluation of the biochip assay for rapid detection of mycobacterial isolates in smear-positive specimens. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2019;81:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.01.036. http://10.1016/j.ijid.2019.01.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Padilla E., González V., Manterola J.M., et al. Comparative evaluation of the new version of the INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria and genotype Mycobacterium assays for identification of Mycobacterium species from MB/BacT liquid cultures artificially inoculated with Mycobacterial strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42(7):3083–3088. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.7.3083-3088.2004. http://10.1128/jcm.42.7.3083-3088.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Richter E., Rüsch-Gerdes S., Hillemann D. Evaluation of the GenoType Mycobacterium Assay for identification of mycobacterial species from cultures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44(5):1769–1775. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.5.1769-1775.2006. http://10.1128/jcm.44.5.1769-1775.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang M., Huh H.J., Kwon H.J., et al. Comparative evaluation of the AdvanSure Mycobacteria GenoBlot assay and the GenoType Mycobacterium CM/AS assay for the identification of non-tuberculous mycobacteria. J. Med. Microbiol. 2016;65(12):1422–1428. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000376. http://10.1099/jmm.0.000376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huh H.J., Kim S.Y., Shim H.J., et al. GenoType NTM-DR performance evaluation for identification of Mycobacterium avium complex and Mycobacterium abscessus and determination of clarithromycin and amikacin resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019;57(8) doi: 10.1128/JCM.00516-19. http://10.1128/jcm.00516-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ramis I.B., Cnockaert M., Von Groll A., et al. Evaluation of the Speed-Oligo Mycobacteria assay for the identification of nontuberculous mycobacteria. J. Med. Microbiol. 2015;64(Pt 3):283–287. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000025. http://10.1099/jmm.0.000025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim S.H., Shin J.H. Identification of nontuberculous mycobacteria from clinical isolates and specimens using AdvanSure mycobacteria GenoBlot assay. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;73(4):278–281. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2019.111. http://10.7883/yoken.JJID.2019.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim J.A., Yu H.J., Hwang Y.Y., et al. Performance evaluation of MolecuTech REBA myco-ID using HybREAD480 for identification of nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin. Lab. 2023;69(7) doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2022.221115. http://10.7754/Clin.Lab.2022.221115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang Q., Xiao H., Yan L. PCR-reverse blot hybridization assay in respiratory specimens for rapid detection and differentiation of mycobacteria in HIV-negative population. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021;21(1):264. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-05934-x. http://10.1186/s12879-021-05934-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Uwamino Y., Aono A., Tomita Y., et al. Diagnostic utility of a Mycobacterium multiplex PCR detection panel for tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023;11(3) doi: 10.1128/spectrum.05162-22. http://10.1128/spectrum.05162-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schildhaus H.U., Steindor M., Kölsch B., et al. GenoType CM Direct(®) and VisionArray Myco(®) for the rapid identification of mycobacteria from clinical specimens. J. Clin. Med. 2022;11(9) doi: 10.3390/jcm11092404. http://10.3390/jcm11092404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Khare R., Brown-Elliott B.A. Culture, identification, and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin. Chest Med. 2023;44(4):743–755. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2023.06.001. http://10.1016/j.ccm.2023.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shen Y., Fang L., Xu X., et al. CapitalBio Mycobacterium real-time polymerase chain reaction detection test: rapid diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacterial infection. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;98:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.042. http://10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Runyon E.H. Pathogenic mycobacteria. Bibl. Tuberc. 1965;21:235–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Song J., Yoon S. In Y., et al. Substantial improvement in nontuberculous mycobacterial identification using ASTA MicroIDSys matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry with an upgraded database. Ann Lab Med. 2022;42(3):358–362. doi: 10.3343/alm.2022.42.3.358. http://10.3343/alm.2022.42.3.358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rotcheewaphan S., Odusanya O.E., Henderson C.M., et al. Performance of RGM medium for isolation of nontuberculous mycobacteria from respiratory specimens from non-cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019;57(2) doi: 10.1128/JCM.01519-18. http://10.1128/jcm.01519-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ditommaso S., Giacomuzzi M., Memoli G., et al. A new culture method for the detection of non-tuberculous mycobacteria in water samples from heater-cooler units and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation machines. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2022;19(17) doi: 10.3390/ijerph191710645. http://10.3390/ijerph191710645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Singh K., Kumari R., Tripathi R., et al. Detection of clinically important non tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) from pulmonary samples through one-step multiplex PCR assay. BMC Microbiol. 2020;20(1):267. doi: 10.1186/s12866-020-01952-y. http://10.1186/s12866-020-01952-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kim M.J., Kim K.M., Shin J.I., et al. Identification of nontuberculous mycobacteria in patients with pulmonary diseases in gyeongnam, Korea, using multiplex PCR and multigene sequence-based analysis. Can. J. Infect Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/8844306. http://10.1155/2021/8844306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shin S.J., Lee B.S., Koh W.J., et al. Efficient differentiation of Mycobacterium avium complex species and subspecies by use of five-target multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48(11):4057–4062. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00904-10. http://10.1128/jcm.00904-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chae H., Han S.J., Kim S.Y., et al. Development of a one-step multiplex PCR assay for differential detection of major Mycobacterium species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017;55(9):2736–2751. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00549-17. http://10.1128/jcm.00549-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Morais F.C.L., Bello G.L., Costi C., et al. vol. 117. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz; 2022. http://10.1590/0074-02760220031 (Detection of Non-tuberculosus Mycobacteria (NTMs) in Lung Samples Using 16S rRNA). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fyfe J.A.M., Lavender C.J. Detection of Mycobacterium ulcerans DNA using real-time PCR. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022;2387:71–80. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1779-3_8. http://10.1007/978-1-0716-1779-3_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kim J.U., Ryu D.S., Cha C.H., et al. Paradigm for diagnosing mycobacterial disease: direct detection and differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and non-tuberculous mycobacteria in clinical specimens using multiplex real-time PCR. J. Clin. Pathol. 2018;71(9):774–780. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2017-204945. http://10.1136/jclinpath-2017-204945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Keerthirathne T.P., Magana-Arachchi D.N., Madegedara D., et al. Real time PCR for the rapid identification and drug susceptibility of Mycobacteria present in Bronchial washings. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016;16(1):607. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1943-y. http://10.1186/s12879-016-1943-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kehrmann J., Kurt N., Rueger K., et al. GenoType NTM-DR for identifying Mycobacterium abscessus subspecies and determining molecular resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016;54(6):1653–1655. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00147-16. http://10.1128/jcm.00147-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lee A.S., Jelfs P., Sintchenko V., et al. Identification of non-tuberculous mycobacteria: utility of the GenoType Mycobacterium CM/AS assay compared with HPLC and 16S rRNA gene sequencing. J. Med. Microbiol. 2009;58(Pt 7):900–904. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.007484-0. http://10.1099/jmm.0.007484-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lotz A., Ferroni A., Beretti J.L., et al. Rapid identification of mycobacterial whole cells in solid and liquid culture media by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48(12):4481–4486. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01397-10. http://10.1128/jcm.01397-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Huh H.J., Kim S.Y., Jhun B.W., et al. Recent advances in molecular diagnostics and understanding mechanisms of drug resistance in nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019;72:169–182. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.10.003. http://10.1016/j.meegid.2018.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bajaj A.O., Slechta E.S., Barker A.P. Rapid and accurate differentiation of mycobacteroides abscessus complex species by liquid chromatography-ultra-high-resolution Orbitrap™ mass spectrometry. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.809348. http://10.3389/fcimb.2022.809348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rindi L., Puglisi V., Franconi I., et al. Rapid and accurate identification of nontuberculous mycobacteria directly from positive primary MGIT cultures by MALDI-TOF MS. Microorganisms. 2022;10(7) doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10071447. http://10.3390/microorganisms10071447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Li B., Zhu C., Sun L., et al. Performance evaluation and clinical validation of optimized nucleotide MALDI-TOF-MS for mycobacterial identification. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.1079184. http://10.3389/fcimb.2022.1079184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kim S.H., Shin J.H. Identification of nontuberculous mycobacteria using multilocous sequence analysis of 16S rRNA, hsp65, and rpoB. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2018;32(1) doi: 10.1002/jcla.22184. http://10.1002/jcla.22184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]