Abstract

Reducing energy consumption in the operation of airports has been identified as one of the approaches to achieve the commitments of the countries in reducing their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The first step in this approach is the development of an energy diagnostic. However, multiple practical aspects remain unresolved when applying the existing methodologies to perform energy diagnostics, especially in the case of small and medium-scale airports. Seeking to address these issues, this work presents energy diagnostics of two Mexican international airports so that it can be used to carry out energy diagnostics in other airports with similar characteristics. Emphasis is given to identifying and prioritizing, from a sustainable point of view, the strategies to reduce energy consumption and GHG emissions. The Ciudad del Carmen Airport (CME) is located in a nearshore region with high ambient temperatures (27 °C) and humidities. It was found that in 2019, the CME airport consumed 123 MWh with an average of 577 Wh per passenger, with the HVAC system being the primary energy consumer. Critical strategies for the CME airport include photovoltaic systems and HVAC renovation. In contrast, the Puebla airport (PBC) is located in a region with comfortable ambient conditions (16 °C). In 2019, the PBC airport consumed 61.31 MWh/year and 442 Wh per passenger. The main strategies for PBC include expanding its photovoltaic energy generation system, employee awareness programs, and renewing the vehicle fleet with electric vehicles.

Keywords: Energy diagnostic, Energy audit, GHG emissions, Sustainable development goals, Climate action, Airport, Landside

Nomenclature

| ACA | air carbon accreditation |

| investment cost criterion | |

| average annual cost of electricity | |

| investment cost | |

| CME | Carmen International Airport |

| CNG | compressed natural gas |

| DEL | diesel equivalent liters |

| EF | emission factors |

| GHG | greenhouse gas |

| HVAC | heating, ventilation, air conditioning |

| IATA | International Air Transport Association |

| IRR | internal rate of return |

| LATAM | Latin-American And Caribbean Countries |

| LHV | low heating value |

| LPD | lighting power density |

| LPG | liquefied petroleum gas |

| NPV | net present value |

| nominal power | |

| PBC | Puebla International Airport |

| nominal refrigeration capacity | |

| ROI | payback period |

| RWTP | residual water treatment plant |

| SEER | seasonal energy efficiency ratio |

| average number of hours of use per year |

1. Introduction

Airports have been identified as one of the largest emitters of greenhouse gases (GHG). Thus, national governments look to reduce the energy consumption of their airports as a strategy to comply with their commitments to reducing GHG emissions. The first step in this approach is the development of an energy diagnostic. However, multiple practical aspects remain unresolved in applying the existing general methodologies to perform energy diagnostics, especially in the case of small and medium-scale airports and even more, under the context of Latin-American and Caribbean countries (LATAM).

The aviation industry accounts for around 2.1 % of man-made CO2 emissions and is responsible for 12 % of emissions from all transport sources. The transportation sector alone accounts for 16.2 % of global GHG emissions [1]. In addition, these emissions are estimated to increase by about 4 % per year due to the growth of the industry [2]. It is estimated that by 2050, more than 10 billion passengers will be transported globally [2] and that passenger demand will rise to 750 million by 2036 in LATAM, generating a significant increase in GHG emissions [3].

To align air transport with the Paris Agreement's goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 °C, the International Air Transport Association (IATA) committed to achieving net-zero carbon emissions from its operations by 2050 [4,5]. To achieve this goal, IATA developed the Air Carbon Accreditation (ACA), a global standard for carbon management in the airport industry. In 2019, there were already 274 accredited airports worldwide, achieving an annual reduction of 322,297 tons of CO2. However, only 8 % of these airports are in LATAM [6].

In 2021, Mexico had 1714 airstrips visible from the sky, placing it as the third country with the most airstrips worldwide. However, Mexico's Federal Civil Aviation Agency (AFAC) recognized only 76 airports [7,8]. In 2022, 23 airports were already ACA certified [4]. These facts illustrate the relevance of decarbonization in the Mexican aviation industry.

1.1. Energy diagnostic

To achieve the ACA certification, airports must carry out an energy diagnostic as a first step. This is an evaluation of the efficiency with which different types of energy are used in an industry, building, or process, looking for opportunities to reduce their energy consumption. The most important part of an energy diagnostic is the identification of the measures to reduce energy consumption and, therefore, GHG emissions. There are three levels of energy diagnostics [9].

-

•

Level 1 or basic diagnostic, which is carried out by visually examining the industrial process or installation to identify potential energy savings alternatives.

-

•

Level 2 or fundamental diagnostics, which provides information on electrical and thermal energy consumption by functional areas or specific operating processes. Subsystems with the most significant energy waste are detected. This level offers data about energy savings and, consequently, cost reduction.

-

•

Level 3 or advanced diagnostic, which provides accurate and understandable information on each relevant point of the industrial process diagram or installation and the energy losses of each piece of equipment involved.

Level 2 diagnostics are the most useful for knowing the energy-saving potentials of an installation [10].

From the perspective of quantifying GHG emissions, energy diagnostics can be carried out with three scopes. Scope 1 quantifies the GHG emission directly generated by the operation of the company or process under study. Scope 2 adds indirect emissions, such as emissions from generating electricity that the company or process consumes. Scope 3 adds all indirect GHG emissions linked to the operation of the company or process, such as the emissions of all providers or raw materials and distributors of the company's products [11].

Aiming to carry out an energy diagnostic, airports can be divided into two areas of activity: i) The land side, which includes terminal buildings, parking lots, access roads, and ground transportation. ii.) The airside which comprises all areas accessible to aircraft, including the control tower and airfield.

The development of land and air activities demands energy, where electricity, natural gas, and fossil fuels are the primary energy sources. This work focuses on the land side area of airports, where energy is used for heating, ventilation, air conditioning (HVAC), lighting, electric appliances, and domestic cold and hot water [[12], [13], [14], [15], [16]].

Airport administrators look after measurements to reduce energy consumption in their terminal buildings and airport infrastructure [17,18]. Table 1 lists recent studies that aim to address this need.

Table 1.

Literature review on energy diagnostics in airports.

| Year | Title | Autor | Place | Experimental | Energy Diagnosis | Proponed strategies | Energy saving potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | Reduction of energy consumption and CO2 emissions of HVAC system in airport terminal buildings | O.F.Yildiz et al. [16] | Turkey | – | Energy consumption: 6.301 GWh/annual, heating 9.99 %, lightning 11.92 %, pumps and fans 8.89 %, water heating 4.29 %, refrigeration system 2.54 %, electrical equipment 2.38 %. | Heating/cooling temperature adjustment. Night ventilation. Free cooling – water-side economizer. Heat exchanger in AHUs. Use of variable speed circulation pumps. |

57.24 % savings in annual energy consumption and displaced annual CO2 emissions are reduced by 48.79 % |

| 2021 | Fully solar powered Doncaster Sheffield Airport: Energy evaluation, glare analysis and CO2 mitigation | Sher F. et al. [27] | United Kingdom | – | Electrical consumption: 6951.5 MWh/annual. | Photovoltaic panels. | Reduction of 11,642.91 tons of CO2/year |

| 2021 | Energy audit and evaluation of indoor environment condition inside Assiut International Airport terminal building, Egypt | Abdallah, A et al. [20] | Egypt | x | Consumption: HVAC system 70 %, lightning 20 %, electrical equipment 10 %. | Increasing the temperature set point. Lighting System Controls. Use of LED luminaires. |

24.5 % reduction |

| 2017 | Assessment of Energy Consumption Pattern and Energy Conservation Potential at Indian Airports | Malik, Kanika [19] | India | x | Annual electricity consumption: Udaipur, 3574140 kWh, Raipur: 4453739 kWh and Aurangabad: 2941950 kWh. | Reduction: | |

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

| 2015 | Concepto Aeropuerto Verde. Medidas de reducción de emisiones en aeropuertos y aplicación al Aeropuerto de Sevilla | Nuñez Baladrón, A [22] | Sevilla | x | Electricity consumption 2009–2014: 15.126 MWh. HVAC 56 %, lightning 13 % and electrical signage 7 %. |

|

Reduction:

|

| 2015 | Determinación de la huella de carbono en el aeropuerto internacional el dorado a la luz del protocolo greenhouse gas (GHG) | Jurado Bolaños C. and Lizcano Sandoval Y [21] | Colombia | x | Electricity consumption: 35.622.238 Kwh %CO2e: electricity 89.38 %, waste 7.50 %, vehicles 2.37 %, electric generator 0.74 %. | Use of electric or hybrid vehicles. Periodic maintenance of vehicles used. Alternative energies for cell phone charging Training Programs Reforestation |

– |

| 2013 | Exploring design scenarios for large-scale implementation of electric vehicles; the Amsterdam Airport Schiphol case | Silvester, S et al. [26] | Germany | – | – | Implementation of electric vehicles | – |

| 2012 | Scenarios to reduce electricity consumption and CO2 emission at Terminal 3 Soekarno-Hatta International Airport | Perdamaian, L et al. [24] | Indonesia | – | Annual electricity consumption: 7694 MWh: HVAC system 86.59 %, lightning 9.33 %, electrical equipment 2.41 %. |

|

Reduction: |

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|||||||

| 2003 | Energy conservation potential, HVAC installations and operational issues in Hellenic airports | CA Balarás et al. [23] | Greece | x | The total annual energy consumption of all Hellenic airports is about 234 kWh/m2. On average over a 4-year period (1995–1998) | Thermal insulation of the walls and ceiling. Double glazing. Ceiling fans. Sun protection: outdoor shading. Staff training. Update electrical light wiring. Uses of CHP systems. |

Potential energy savings range from 15 to 20 % for airport A and 35–40 % for airports B and C |

Malik, K [19]. are weather conditions, occupancy level, and hours of operation. Previous studies have reported that depending on the local prevailing weather conditions, the operation of the HVAC system accounts for the highest energy consumption (81.6 % for the terminal building of Erzurum Airport, Turkey [16]; 70 % for the Assiut airport, Egypt [20]; 63 % for airports in India [19]). The second largest energy consumer is the lighting system. Few studies have been reported on the case of medium-sized airports typical of the LATAM countries [21].

Among the most popular strategies identified to reduce energy consumption and emission of GHG in airports are.

-

•

The replacement of old dated HVAC systems with more efficient ones and lowering their operating temperatures. Nuñez Baladrón [22] found that they could have a reduction of 1.7 ktCO2/year at Seville Airport with the replacement of more efficient HVAC systems. Abdallah et al. [20], in 2021, proposed to lower the operating temperature of the HVAC system of the Assiut Airport (Egypt) to achieve a reduction of 24.5 % in electricity consumption. Balaras et al. [23] (2003) estimated energy savings between 15 % and 35 % in the operation of the HVAC system of airports in Greece.

-

•

The use or replacement of window film. Perdamaian et al. [24] estimated that window film replacement could reduce the emission of 289.9 kt of GHG per year at Terminal 3 of Soekarno-Hatta Airport.

-

•

The use of photovoltaic plants. Sher F. et al. (2021) [25] estimated that a 12 MW solar photovoltaic plant could remove up to 11.6 ktCO2/year in the operation of the Doncaster Sheffield Airport (UK). Nuñez Baladrón [22] estimated a reduction of 5.2 ktCO2/year at Seville Airport with the installation of photovoltaic panels.

-

•

The integration of electric vehicles. Silvester et al. [26] examined scenarios for the integration of electric vehicles for the Amsterdam Airport Schiphol.

Through the deployment of these strategies, relevant reductions in energy consumption and GHG emissions are being obtained in the operation of airports worldwide. Yildiz et al. (2022) [16] reported energy savings between 0.4 % and 48.0 % and GHG emissions reduction between 0.8 % and 40.1 % in the terminal building of Erzurum Airport (Turkey).

However, gaps of knowledge remain on i.) how to conduct the energy diagnostics, from a practical point of view, especially under the local conditions of LATAM countries, using historical data frequently available in the operation of airports, ii.) the identification of a baseline of comparison on energy consumption, iii.) the process of identification of additional strategies to reduce energy consumption that take into consideration the local conditions, and iv) The prioritization of the strategies to be implemented from a sustainable point of view. i.e., on an analysis that includes economic, environmental, and social aspects.

Aiming to address previous needs, this paper describes in detail a methodology for carrying out energy diagnostics in medium-sized airports and illustrates its application through two cases of study in Mexico.

Contribution to new knowledge.

-

•

A methodology to conduct energy diagnostics in airports, especially under the local conditions of LATAM countries, using historical data frequently available in the operation of airports,

-

•

The identification of a baseline of comparison for the energy consumption in airports,

-

•

The process of identification of additional strategies to reduce energy consumption in airports that take into consideration the local conditions.

-

•

A methodology to prioritize strategies to reduce energy consumption in airports using the concept of sustainability as a criterion. i.e., on an analysis that includes economic, environmental, and social aspects

Finally, this work contributes to the advancement of the UN's sustainable development goals, in particular SDG 7 (Affordable and clean energy) and SDG 13 (Climate Action).

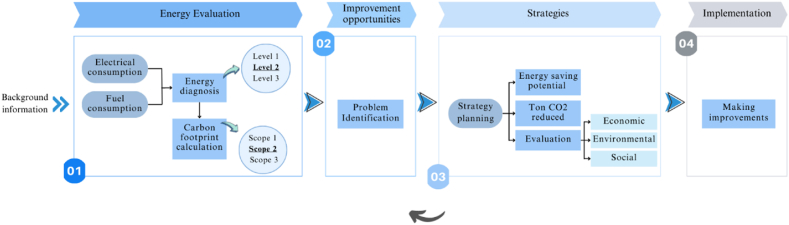

2. Methodology

The series of standards ISO 52000-1 and 2 specify the requirements and procedures for carrying out an energy audit [28,29]. They provide guidelines to establish, manage, and improve energy consumption and efficiency in buildings and organizations [30]. The ISO 14064 standard provides a set of tools for designing programs aimed at reducing GHG emissions [31]. Based on these general methodologies, we proposed a specific methodology for carrying out energy diagnostics in airports (Fig. 1). It includes four general steps: Background information, energy assessment, opportunity identification, and strategy prioritization. Next, we describe each of these steps.

Fig. 1.

General methodology followed in the present study to carry out energy diagnostics in medium-sized airports.

2.1. Background information

An energy diagnostic starts by describing the context under which the airport operates. This description includes geographic location, prevailing weather conditions, level of operation in terms of passengers, tons of load, and number of flights per year. It should include all information that could influence the decision-making process about the course of action to reduce energy consumption and GHG emissions.

To observe the evolution of energy consumption and GHG emissions over time, a base year is established. Energy consumption and emissions are compared against the ones of this year, referred to as the baseline.

Then, the operational and organizational boundaries of the study are established. As described previously, airports can be divided into two areas of activity: i) The land side, which includes terminal buildings, parking lots, access roads, and ground transportation. ii.) The airside includes all areas accessible to aircraft, including the control tower and airfield. For the purposes of the ACA certification, energy diagnostics focuses on land operation.

Finally, the level and scope of the energy diagnostic is established. This study focuses on level two or fundamental diagnostics, which provides information on the consumption of both electrical and thermal energy by functional areas or specific operating processes. Level one and three were described in the introduction section. This study also focuses on energy diagnostics with scope two, where the direct and indirect GHG emissions are determined. Scopes one and three were also described in the introduction section.

2.2. Assessment of the energy consumption and GHG emission

The objective of this phase is to quantify the annual energy consumption of the different areas involved in the operation of the airport, as well as the yearly GHG emissions. It includes the following sub-steps.

2.2.1. Energy matrix

The consumption of the different sources of energy is compared, looking to identify the main consumers and thus focus on them in the subsequent analysis. Aiming to compare the fuel energy consumption of technologies that use different sources of energy, the energy consumption was expressed in terms of diesel equivalent liters (DEL). The energy content of a diesel liter in Mexico is 37.7 MJ/L [32]. Thus, the fuel consumption of gasoline-fueled vehicles was expressed in terms of DEL. The gasoline has a density of 0.844 kg/m3 and an LHV of 46.31 MJ/kg. Thus, 1.06 L of gasoline is equivalent to 1 DEL [33]. Similarly, the energy consumption of electric devices was expressed in terms of DEL. In this case, 1 DEL of electricity corresponds to the electric energy that the national system of electricity generation can produce with 37.7 MJ (10.5 kWh) of energy. Thus, 5.55 kWh of electric energy is equivalent to 1 DEL [34], which was obtained considering an average efficiency of 53 % of the Mexican electric generation system. Table 2 lists the DEL for other sources of energy typically used in airports.

Table 2.

Emission factors used to quantify the GHG emitted yearly in the operation of airports.

| Source | Energy source | DEL | WtT |

TtW |

WtW |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 |

CH4 |

N2O |

|||||

| kg CO2e/DEL | kg/DEL | kg/DEL | kg/DEL | kg CO2e/DEL | |||

| Diesel | 1.0 L | 0.64a | 2.73 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 3.42 | |

| Mobile | CNG | 1.03 m3 | 0.45a | 2.18 | 0.0035 | 0.0001 | 2.76 |

| Electric | 5.55 kWh | 1.97 | 0.00 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.97 | |

| Gasoline | 1.06 L | 2.75 | 2.72 | 0.0028 | 0.0316 | 2.75 | |

| Stationary | Natural Gas | 1.03 m3 | 2.09 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

For the production, distribution, and transportation of diesel and CNG emission factors, the values reported by the United Kingdom were used [42].

2.2.2. Electricity consumption

Electricity bills provide information about electric consumption, power factors, and paid values. The power factor of an AC power system is the ratio of the real power absorbed by the load to the apparent power flowing in the circuit, and therefore, it should be greater than 0.9. Paid values during peak and intermediate hours of electric demand should be minimal. This information should be organized to observe historical consumption and seasonal behaviors.

2.2.2.1. Census of electrical loads

This analysis seeks to break down the consumption of electrical energy by type of use or area. Airports usually do not have this breakdown. Therefore, this analysis aims to provide a first approximation for this breakdown starting from information available at the airport administration offices.

Airports usually have an inventory of equipment. Therefore, the annual energy consumption can be obtained from the nominal power () of each equipment within area j, multiplied by an estimated average number of hours of use per year () (Equation (1)). The analysis should be carried out for lighting, HVAC, electric motors, commercial areas, and miscellaneous equipment.

| (1) |

-

•

HVAC: The annual energy consumption associated with the operation of air condition equipment is obtained from Equations (1), (2)), where is the nominal refrigeration capacity of equipment i located in area j, and is the corresponding Seasonal Energy Efficiency Ratio. SEER is the ratio of the total heat removed from the conditioned space during the annual cooling season divided by the total electrical energy consumed by the air conditioner during the same season. This last piece of information is provided by the equipment manufacturer. For Mexico, the NOM-011-ENER-2006 standard should be used [35]

| (2) |

-

•

Lighting system: The energy consumption associated with the operation of the lighting system can be obtained through Equation (1), where is directly provided by the manufacturer for each type of lamp. In some instances, the airports do not have an inventory of luminaries. In this case, an estimate can be obtained knowing the construction area of the airport and assuming that the lighting system satisfies the minimum requirements of Lighting Power Density (LPD) established in the local standards for office areas, lobby and hallways, commercial areas, bathrooms, and waiting rooms. LPD is defined as watts of lighting per unit area (W/m2). For Mexico, the standards NOM-007-ENER-2004, NOM-025-STPS-2008 should be used [36,37].

-

•

Electric motors: several electrical motors are used within airports to pump clean and disposed water, power transporting bands, air blowers, elevators, etc. They are included in the equipment inventory at the airport. Thus, the annual energy consumption associated with the operation of these motors can be calculated through Equation (1), where can be obtained from the manufacturer specifications or by using Equation (3), where V is the nominal voltage, I is the current, and Cos ϕ is the power factor. In Equation (3), the factor applies only for the case of motors operating in three-phase electric systems.

| (3) |

-

•

Commercial areas: Within airports, several areas are allocated to the operation of commercial businesses, such as restaurants, retail stores, and services, such as rental cars. In most instances, the energy consumption of those commercial areas is unknown. Thus, a sub-energy diagnostic should be carried out for each of these areas.

2.2.3. Fuel consumption

Airports consume diesel and gasoline to fuel vehicles used for the transport of personnel, provide fuel to airplanes, the operation of backup electric plants, emergency vehicles, and gardening. It also uses natural gas and LPG for cooking and warm water. Since the use of fuels directly affects the budget of the airports, airports frequently have records of their fuel consumption discriminated by vehicle and type of use.

2.2.4. Assessment of the GHG emissions

The direct (scope 1) and indirect emissions (scope 2) should be quantified based on the annual energy consumption obtained in the previous step. Direct emissions include emissions from ground vehicles, stationary combustion, fugitive emissions from the wastewater treatment plant, and direct fugitive GHG emissions from the HVAC systems. Indirect emissions include those emissions released by the national electric system associated to the electric consumption within the airport boundaries.

Direct and indirect GHG emissions from vehicles: Using the emission factors (Table 2) established by the local environmental authority (SEMARNAT), which are based on the emission factors established by the USEPA, the GHG emissions of vehicles were obtained per type of fuel. CO2, CH4, and N2O were considered the main GHG emitted by vehicles. The results were reported in terms of CO2 equivalent (CO2e) per kilometer traveled or kilometer ton transported, considering that CH4 and N2O have a global warming potential (GWP) equivalent to 28 and 265 times that of CO2, respectively. A life cycle analysis was carried out, which included emissions during fuel production (power source to fuel tank, WtT) and emissions during vehicle operation (from tank to wheel, TtW). It is important to highlight that there is significant variability in the reported values of GWP and N2O emission factors, especially in the case of the use of CNG. In this work, the values stipulated by the local environmental authority were used. Table 2 shows that, in a life cycle analysis (WtW), when a vehicle is powered by diesel, regardless of local conditions and specific technology, it emits 3.42 kg CO2e/DEL, and CNG and electric emissions are 19 % and 42 % lower using the energy sources available in Mexico [[38], [39], [40], [41]].

Stationary sources: Scope 2 emissions from stationary combustion were calculated based on the historically purchased quantities of commercial fuels (LGP, diesel, gasoline). Mexico-specific emission factors (EF) were used to estimate CO₂ emissions, while the default EF from the IPCC Guidelines was used to calculate CH₄ and N₂O emissions.

Fugitive emissions: Emissions from the wastewater treatment plant were calculated based on the defined methodology of the 2006 IPCC Guidelines.

2.3. Identification of strategies to reduce energy consumption and GHG emissions

According to the methodology illustrated in Fig. 1, the third step, after the evaluation of the energy consumption, is the identification of strategies to reduce energy consumption and GHG emissions that take into consideration the local conditions and are oriented to addressing the main energy consumers within the airport.

There are no rules or methodologies to identify strategies to reduce energy consumption for non-experts besides surveying the strategies explored in previous studies (Table 1). Trained personnel in HVAC systems know the existing technologies, typical values for the energy performance of the latest technologies, and best practices to reduce energy consumption. Similarly, this happens for personnel trained in lighting systems, boilers, vehicles, and so on. Thus, consulting experts who have been working in the region under consideration is the best way to identify these strategies. At this moment of the study, we recommend including all potential strategies.

2.4. Prioritization of the strategies to be implemented

Then, for each potential strategy, the energy savings and reductions in GHG emissions were calculated, along with their respective economic feasibility and social impacts. They were calculated and compared to the base scenario, which was defined as keeping the airport operation as usual. The scopes of the strategies were the most optimistic. i.e., the 100 % replacement of the existing technology or the auto-generation of 100 % of the electric energy consumed by the airport.

The reduction in energy consumption and GHG emissions were calculated using the same methodology used to evaluate the current situation (section 2.1). The economic feasibility of implementing each strategy was carried out using standard methodologies over the life span of the strategy, such as the calculation of the net present value (NPV), Internal rate of return (IRR), or payback period (ROI).

Finally, the quantification of the social impacts is the most challenging because there are no well-established methodologies to assess them quantitatively. We proposed to evaluate the social aspects through the social acceptance of the strategy and through the administrators' willingness to implement such a strategy. For social acceptance, we propose to interview a representative sample of the directly affected population, asking for their level of acceptance of implementing each strategy after they are informed of the benefits and damages of implementing each strategy. We also propose to evaluate the willingness of the airport administration to implement such a strategy based on the perception of the easiness of implementing it. For example, conducting a training campaign has a value of 1 because it does not affect the operation of the airport while implementing changes in the central HVAC system involves pausing activities and closing airport areas, so people perceive it as a strategy with a greater degree of difficulty. Therefore, this strategy has an intermediate value (∼0.7)

Aiming to prioritize the identified strategies, a set of criteria was established to evaluate the sustainability of each strategy. The initial investment cost and payback period were chosen to evaluate the economic aspects. The reduction in GHG expressed in tons of CO2e/year was chosen to evaluate the environmental aspects. Finally, the social aspects were evaluated through the technical easiness of implementation and social acceptance.

Each criterion was normalized so that zero was the least desirable situation and one the most desirable. In this way, the investment cost (Ci) was normalized with respect to the average annual cost of electricity (Ce), and therefore the investment cost criterion (C) was established as:

| (1) |

Similarly, a payback period (ROI) of less than three years was taken as acceptable, and therefore, payback period criterion (A) was defined as in equation (2), where, for ROI> 6, A assumes a value of zero and for ROI< 3, A assumes a value of 1.

| (2) |

For the reductions of GHG emissions criteria, the fraction of reduced emissions compared to the average annual emissions of the airport was taken as the criterion directly. The social aspects were already expressed on a scale from 0 to 1.

Finally, the sustainability of each strategy was reported as the weighted average of the economic, environmental, and social aspects. It was assigned a relative relevance to each of these criteria. Economic aspects were acknowledged with a relevance of 40 % distributed between the cost of investment (15 %) and ROI (25 %). Environmental aspects, measured as GHG emission reductions, received a relevance of 30 %. Finally, social aspects received a relevance of 30 %, measured as the acceptance of users and the technical easiness of implementing the proposed measure. Thus, the strategy with the highest weighted average should be implemented with the highest priority.

3. Results

In this section, we describe the results of carrying out energy diagnostics in two representative airports of LATAM following the methodology outlined above. Sensitive information for the Mexican airport administration office (ASA) has been removed from this report.

3.1. Background information

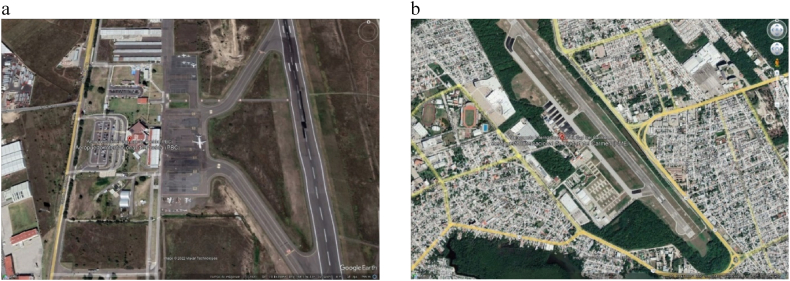

Ciudad del Carmen International Airport (CME) is located on an island, l.3 km north of the city of Ciudad del Carmen, Mexico, at an elevation of 3 masl (Fig. 2). The predominant climate is warm and humid, with rains of 1300–1500 mm in summer. The rainy season is from June to October. The average annual temperature is 27 °C, with 38 °C of maximum temperatures during the months of April to June and minimums of 14° in the months of January and February. There is no risk of frost, and as for hurricanes, its coastline is the one with the lowest incidences [43]. The CME airport has an area of approximately 192 ha and a platform for commercial aviation of 10,484 m2. It also has three positions and a track of 2.2 km in length.

Fig. 2.

PBC and MCI airports. a.) Puebla International Airport, and b.) Ciudad del Carmen International Airport (Fuente: Google Earth).

The Puebla International Airport (PBC) is located 25 km east of the city of Puebla, Mexico, at an elevation of 2241 masl (Fig. 2). Puebla has a subhumid climate with rain in summer. It has an average annual temperature of 16 °C with maximums of 33 °C in the months of May and June and minimums of 0 °C in the months of January and February. It has an annual rainfall of 834.9 mm of water, with the months of June to September being the rainiest [43]. The PBC airport has a platform with three category "D" positions and a runway of 3605 x 45 m. It has an area of 518.1 ha that is dedicated to commerce and a terminal building, as well as a parking lot for approximately 280 vehicles. This infrastructure has an approximate attention capacity of 400 passengers per hour. The PBC airport handles 2000 tons of products per year, ranging from textiles to automotive parts, as well as fruit, courier, and flower shipments.

3.2. Assessment of the energy consumption and GHG emission

During the energy evaluation of the airports under study, a detailed analysis of electricity and fuel consumption was carried out. Information was provided by the airport administration office and gathered through visits. The energy assessment includes the level 2 energy diagnostic and the calculation of carbon footprint emissions with scope 2.

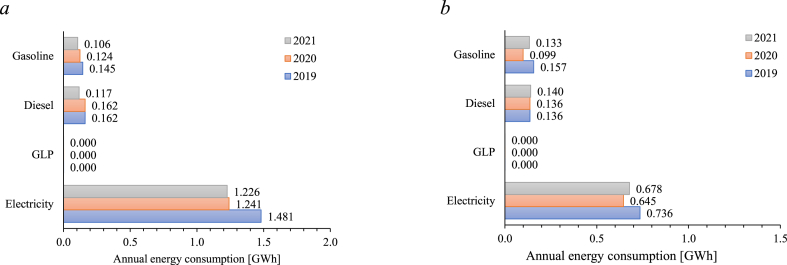

3.2.1. Determination of the energy matrix

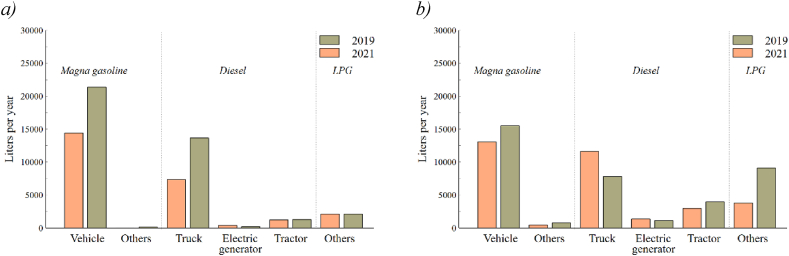

Fig. 3 shows the annual energy consumption, expressed in MWh, per energy source of the CME airport and PBC airports during the years 2019–2021. It is noted that electricity consumption represents the largest energy consumption for the two airports. During the year 2019 (prior to the COVID-19 pandemic), the annual electricity consumption was 1.48 GWh and 736 MWh for CME and PBC airports, respectively. Electricity consumption in the CME airport represented 81.6 % of total energy consumption, followed by diesel fuel consumption (9.7 %) and gasoline (8.7 %). Similarly, for the PBC airport, electricity consumption represented 71.5 %, while gasoline fuel consumption was 15.3 %, and diesel fuel consumption was 13.2 %. GPL consumption was negligible for both cases (<0.001 %).

Figs. 3.

2019–2021 annual energy consumption for the a) CME and b) PBC airports.

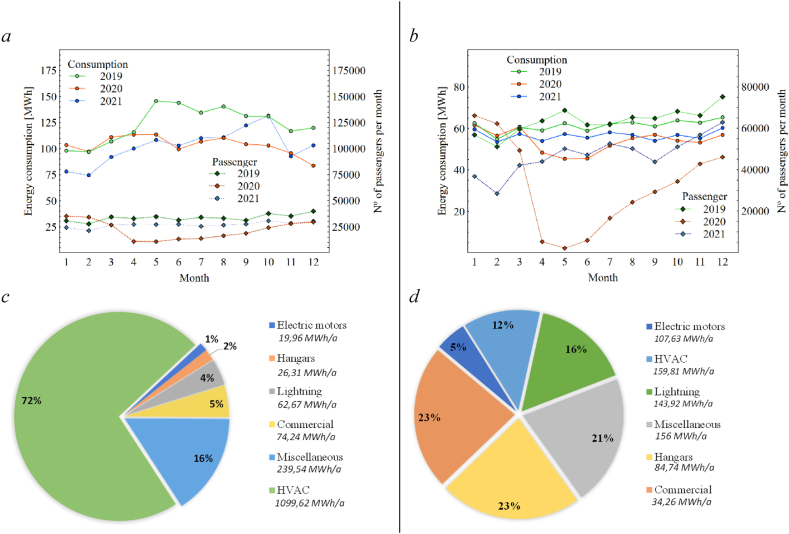

3.2.2. Electricity consumption

Fig. 4a and 4b shows the monthly variation in electricity consumption and number of passengers during 2019–2021. They show the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic that started in March 2020 and ended in March 2022 in Mexico. It is out of the scope of the present work to determine the impact of this pandemic on airport operations. These figures also show that the summer season (jun–aug) has a pronounced effect on the CME airport energy consumption while it has a minor effect on the electricity consumption of the PBC airport. On average, during 2019, the CME and PBC airports had an energy consumption of 4.08 and 0.9 kWh/pas, respectively. We did not find a reference value for this metric and observed that energy consumption does not have a linear correlation with the number of passengers served, at least during the three years observed in each airport in this study.

Fig. 4.

Annual energy consumption. Monthly electric energy consumption and passenger for the a) CME and b) PBC airports. Electric energy consumption shares for the a) CME and b) PBC airports.

We also found that the power factor of the CME airport decreased with time, reaching values of 0.83 in Dec 2020 while remaining approximately constant (0.94) at the PBC airport. These results indicate an opportunity to reduce the cost of electricity in the CME airport by correcting its power factor.

Fig. 4c and 4d shows the estimated electricity consumption share in both airports. They show that the electricity consumption associated with HVAC is the main consumer in the CME airport (72 %), while the commercial area is the main electric energy consumer (23 %) in the PBC airport.

3.2.2.1. Electricity consumption associated with the operation of the HVAC system

As explained in the methodology section, even though the airport administration offices know the total energy consumed well, they do not trace the energy consumption per area or per consumer. Thus, the energy consumption per consumer must be estimated. The annual electricity consumption of each HVAC equipment was estimated by dividing the nominal refrigeration capacity by its respective Seasonal Energy Efficiency Ratio (SEER) provided by the manufacturer and multiplying it by the estimated number of working hours.

Thus, we found that 72 % and 12 % of the annual electricity consumption of the CME and PBC airports, respectively, are due to the operation of their HVAC system. During the last three years, the CME airport has been replacing the central HVAC system, which is based on chillers of 25 tons of refrigeration (TR) and high energy efficiency (SEER = 18) with a set of mini-splits of low refrigeration capacity (∼3 TR) and low efficiency (SEER∼3.28). Currently, this airport has a cooling capacity of 132 TR, with 48 % of them served by mini-splits.

On the other hand, due to the mild climate conditions of Puebla, the PBC airport has negligible use of HVAC systems. It only has seven mini-splits with a total cooling capacity of 10 TR, which represents 16 % of the total energy consumption.

3.2.2.2. Lighting

The electricity consumption associated with the operation of the lighting system was ∼61 MWh/year and 107.6 MWh/year in the CME and PBC airports, respectively. The largest consumer areas were the terminal building (46 % and 51 % for CME and PBC airports, respectively) and the runway and taxiway (38 % and 22 % for CME and PBC airports, respectively). Most of the lamps used by these two airports are LED-type that have high energy efficiency. Corridors and bathrooms have presence sensors to automatically turn off lights when nobody is present in these areas.

3.2.3. Fuel consumption

Fig. 5 shows the annual 2019 and 2021 fuel consumption in L/year of gasoline and diesel-fueled vehicles, backup electric plants, and LPG heaters and cookers|. Fig. 5a shows that gasoline is the fuel most used (56 % and 44.1 % for CME and PBC airports, respectively, in 2019), followed by diesel (39 % and 33.6 % for CME and PBC airports, respectively).

Fig. 5.

Fuel consumption in the a) CME and b) PBC airports.

Most of these vehicles are used for short-distance trips, and therefore, they travel a few km per year (<10,000 km/year). Their average age is high (∼10 years). Usually, they are well maintained, but their energy efficiency is unknown. Their driving cycle is characterized by low speeds without frequent stops, and thus their fuel consumption cannot be compared to similar vehicles used in urban areas. It can be expected that the renewal of these vehicle fleets would have a minor effect in reducing fuel consumption, but preserving the actual fleet has a direct negative effect on the airport operation reliability due to their frequent malfunctioning.

3.2.4. Assessment of the GHG emissions

Following the methodology outlined in Section 2, the direct (scope 1) and indirect (scope 2) GHG emissions of the airport operation were obtained and listed in Table 3. In 2019, the CME airport emitted 875.2 tCO2e/year, of which 15 % were direct emissions. In the same year, the PBC airport emitted 473.6 tCO2e, of which 22 % were direct emissions. In both airports, >99 % of the GHG emissions were CO2.

Table 3.

Direct and indirect GHG emissions in the CME and PBC airports in 2019 expressed in t CO2e/year.

| Scope | Type | CME airport | PBC airport |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stationary combustion | 4.47 | 20.47 |

| Mobile sources | 96.24 | 79.29 | |

| Fugitive emissions due to the use of refrigerants | 26.48 | 1.77 | |

| Fugitive emission in the RWTP (Residual water treatment plant) system | 0.17 | 0.55 | |

| 2 | Electricity consumption | 747.87 | 371.52 |

| Total GHG emissions | 875.23 | 473.61 | |

The fugitive GHG emissions due to the use of refrigerant (HCFC-22 (R-22), HFC-134a (R-134a) and HFC-410a (R-410a) in the HVAC system were 26.48 tCO2e/year (3.02 %) for the CME airport and 1.77 (0.37 %) tCO2e/year for the PBC airports. The residual water treatment plant (RWTP) system generated negligible (<1 %) fugitive GHG (CH4 y N2O) emissions.

3.3. Identification of strategies to reduce energy consumption and GHG emissions

After visiting the operation of the airport, analyzing their operational variables, consulting experts in electric energy, vehicles, HVAC, and lighting systems, and interviewing maintenance department employees, the following alternatives to reduce energy consumption and GHG emissions were identified.

Photovoltaic electric generation system. This measure consists of implementing photovoltaic energy generation systems connected to the national grid without any energy storage system. It was suggested to implement them progressively until reaching self-supply in 5 years for the CME airport and three years for the PBC airport, where there is already a photovoltaic system in operation. The priority is to locate the panels on the roofs of the buildings to achieve a synergistic effect of providing shade to the building and thus reduce the thermal loads that must be removed by the HVAC system to keep the interior of the building under comfortable conditions. As a second priority for the location of photovoltaic panels, it was suggested that they be used as roofs to provide shade to vehicles in parking lots.

Implement an automatic light shutdown system in external areas. During the visits to the airports, a set of luminaires with manual on/off switches were identified. Some of these luminaires remain on during the day or when nobody is present. It was suggested that an automatic shutdown system be implemented, triggered by sensors of presence and/or lighting level.

Renewal of old-dated vehicles by electric vehicles. The vehicles used inside the airport are operated in cycles of very low autonomy (<5 km). Additionally, these vehicles remain parked most of the time. These circumstances are appropriate for the operation of electric vehicles. It is suggested to replace vehicles whose useful life has already been exceeded (>10 years) with similar vehicles in their electric version with a reduced level of batteries in such a way as to satisfy the daily autonomy and keep them charging while they remain parked.

Reduce the use of mini-splits, favoring the use of central HVAC systems. This measure consists of integrating the spaces that use mini-splits into the central HVAC system of the airport. This strategy satisfies the cooling needs with high-efficiency equipment (SEER>10). This measure is socially unattractive due to people's preference for having control over their own HVAC system rather than relying on a central system with long cooling response times. This measure should be complemented by the following best practices that reduce the electricity consumption associated with the operation of HVAC systems.

-

•

Keep closed doors and windows that connect the building(s) to the outside.

-

•

Provide preventive maintenance to the existing HVAC systems. This includes maintenance to the thermal insulation of the HVAC system pipes, evaporators (filters and coil), and condensers (coil, compressor area, electrical installations/connection boards, and fan).

-

•

Keep the operation of the HVAC system at a set point as high as possible during the summer season (∼24 °C).

-

•

Turn off the HVAC system when there are no people inside the conditioned spaces. It is suggested that an automatic shutdown system powered by presence sensors be included.

-

•

Condition the windows that communicate with the outside with UV reflective covers, blinds, and double glass.

-

•

Paint ceilings and external walls with reflective white paint.

Double door in external access points. It was recommended that double doors be installed at the main access point to reduce the free flow of hot air into the building each time a person enters.

Raise airport managers' and operators' awareness of energy efficiency issues. It consists of carrying out awareness campaigns for airport administrators and operators on the different actions they can take to reduce energy consumption and GHG emissions associated with the operation of the airport.

Energy consumption meters for each commercial local. The presence of commercial businesses within airports is essential to airport operation. These businesses use different devices or equipment that consume energy provided by the airport. Therefore, the relationship of the airport administration with these businesses based on a fixed rent independent of their electricity consumption makes it difficult to implement measures to reduce energy consumption in these areas. As a solution, it is suggested that electricity consumption meters be installed in each commercial area and that the cost of the energy consumed be added to the rent. This strategy facilitates the implementation of energy efficiency measures in these airport areas.

3.4. Prioritization of the strategies

For each measure, the potential of energy savings and the amount of GHG reduced with its implementation was estimated. In addition, an economic evaluation was carried out using the methods of net present value (NPV), internal rate of return (IRR), and number of years of return on investment (ROI). Table 4 shows the results obtained for the most relevant measures identified for the CME and PBC airports.

Table 4.

Energy savings, GHG reductions, and economic analysis of implementation for the most relevant measure to reduce energy consumption and GHG emissions in the CME and PBC airports.

| Strategy | Energy savings MWh/y | GHG reduction tCO2e/y | Cost of investment USD$ | Annual investments USD$/y | Scope y | NPV USD$ |

IRR % |

ROI y | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CME airport | HVAC | 142 | 71.5 | 70,902 | 5028 | 20 | 117,905 | 20.7 | 5.5 |

| Photovoltaic panels | 1316 | 664.6 | 487,773 | 21,208 | 20 | 1,588,535 | 33.8 | 3.3 | |

| Electric vehicles | 206 | 9.4 | 67,488 | 11,365 | 10 | 20,695 | 16.0 | 7.2 | |

| Raising awareness | 39 | 19.9 | 3000 | 2332 | 20 | 26,308 | 77.7 | 1.3 | |

| PBC airport | Photovoltaic panels | 660 | 333.3 | 212,720 | 10,636 | 20 | 796,681 | 33.8 | 3.3 |

| Electric vehicles | 239 | 9.1 | 84,045 | 10,977 | 10 | 1127 | 11.6 | 9.8 | |

| Raising awareness | 20 | 10 | 2500 | 446 | 20 | 3109 | 17.1 | 5.1 |

For the case of the CME airport, the integration of all spaces that currently use mini-splits into a central HVAC system was considered as scope. In practice, this scope is not feasible mainly due to the resistance of users to this change and the existence of spaces located far from the central building. Under this scope, it was obtained that with an investment of USD ∼71,000, an IRR of 18.53 % was obtained, and an NPV of USD 99,937 after 20 years and 6.2 years of ROI. These results show that this strategy is not economically attractive compared to the metrics expected by local investors (IRR∼20 %, ROI<3 years). Considering that the reduction of GHG emissions can be sold at 20 USD$/tCO2e in the carbon credit market, an IRR = 20.7 % and an ROI of 5.5 years was obtained, as shown in Table 4.

For the photovoltaic panel strategy, the self-generation of the average annual consumption of 1.4 GWh for the CME airport and 0.66 GWh for the PBC airport was used as a scope. Using commercially available technologies, considering the location of the airport and the average levels of solar irradiation, it was found that 3500 m2 of solar panels are required for the CME airport, which represents an approximate investment of USD487,773. After 20 years of operation, this measure has an NPV of USD 1,421,478, an IRR of 31 %, and a 6.6-year payback period. When considering the possibility of carbon credits at 20 USD/t CO2e, an NPV of USD 1,588,535 and 3.3 years of return on investment were obtained, as shown in Table 4. For the case of the PBC airport, it was found that 1855 m2 of solar panels are required, with an investment of approximately USD 212,720. After 20 years, this investment has an NPV of USD 796,681, an IRR of 33.8 %, and 3.3 years of return on investment. These data were obtained considering the possibility of carbon credits at 20 USD/tCO2e.

The decision to implement any of these measures to reduce energy consumption and GHG emissions obeys economic, environmental, and social criteria. A weighted average was calculated to obtain a global metric of prioritization (Table 5).

Table 5.

Prioritization of strategies to reduce energy consumption and GHG emissions in the CME and PBC airports.

| Economic |

Environmental |

Social |

Weighted average | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost of investment |

ROI |

GHG reduction |

Easy implementation |

Social acceptance |

|||

| Weighting factor | 15 % | 25 % | 30 % | 15 % | 15 % | ||

| Airport | Strategy | ||||||

| CME | HVAC | 0.72 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.37 |

| Photovoltaic panels | 0.00 | 0.91 | 0.76 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 0.74 | |

| Electric vehicles | 0.62 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.70 | 1.00 | 0.35 | |

| Raising awareness | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.70 | |

| PBC | Photovoltaic panels | 0.00 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 0.81 |

| Electric vehicles | 0.53 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.70 | 1.00 | 0.34 | |

| Raising awareness | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.71 | |

These results indicate that for the CME airport, the generation of electricity through solar panels was the most recommended measure (74 %), followed by raising awareness (70 %), the consolidation of the central HVAC system reducing the use of mini-splits (37 %) and the use of electric vehicles (35 %). Similarly, For the PBC airport, the generation of electricity through solar panels was the most recommended measure (81 %), followed by raising awareness (71 %) and vehicle renewal by electric vehicles (34 %).

4. Conclusions

Based on the existing general methodologies to carry out energy diagnostics in buildings and processes, we proposed a specific methodology for the case of medium-sized airports in the context of Latin American countries. It consists of four steps.

-

•

Description of the context under which the airport operates.

-

•

Assessment of the energy consumption and the direct and the indirect GHG emissions to identify the largest energy consumers and GHG emitters.

-

•

Identification of strategies to reduce energy consumption and GHG emissions.

-

•

Prioritization, from a sustainability perspective (economic, environmental, and social) of the strategies to be implemented.

Using the proposed methodology, we carried out energy diagnostics for two airports in Mexico (Ciudad del Carmen-CME and Puebla-PBC). This paper describes how the methodology can be reproduced in other airports.

During the base year (2019), the CME airport consumed 123.41 MWh, averaging 577.41 Wh per passenger served. Due to the high average temperatures (27 °C) and humidity (74 %), the operation of the HVAC system is the primary energy consumer (72 %) with a pronounced seasonal effect on jun–sep. In 2019, the CME airport emitted 875.2 tCO2e/year, of which 15 % were direct emissions. It was found that the most acceptable measures to reduce energy consumption and GHG emissions in this airport are i.) the self-generation of photovoltaic electric energy, ii.) the reconstruction of the central HVAC system, and iii.) raising awareness among airport employees.

Similarly, in 2019, the PBC airport consumed 61.31 MWh/year and 442 Wh/pas. Prevailing atmospheric temperatures (24 °C) and humidity (35 %) are comfortable; therefore, this airport exhibits a negligible demand for HVAC. The primary energy consumers are the commercial area and the lighting system. In the base year (2019), the PBC airport emitted 473.6 tCO2e, of which 22 % were direct emissions. In both airports, >99 % of the GHG emissions were CO2. The most acceptable measures to reduce energy consumption and GHG emissions in the PBC airport are i.) expanding the photovoltaic electricity generation system, ii.) rising awareness among airport employees, and iii.) vehicle fleet renewal by electric vehicles.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jose I. Huertas: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Anggie Z. Rincon: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis. Angelica Velazquez: Formal analysis. Claudia Marquez: Formal analysis. Julio A. Diaz: Resources. Miguel A. Florez: Resources.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Mexican airport administration office ASA, Eng. Mariana Colchado, and the Latin American Network for Research in Energy and Vehicles RELIEVE (Ref. 720RT0014) within the framework of the Ibero-American Program of Science and Technology (CYTED) for their support in the development of this work.

References

- 1.Bakır H., et al. Forecasting of future greenhouse gas emission trajectory for India using energy and economic indexes with various metaheuristic algorithms. J. Clean. Prod. Aug. 2022;360 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131946. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ATAG, "Air Transport Action Group, Facts & figures," https://www.atag.org/facts-figures.html.2020.

- 3.Air transport action group . 2020. Aviation: Benefits beyond Borders Report. [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNFCCC . 2015. Paris Agreement. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar A., A A., Gupta H. Evaluating green performance of the airports using hybrid BWM and VIKOR methodology. Tour Manag. 2020;76(Feb) doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2019.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Airports Control International . 2019. Annual Report Airport Carbon Acreditation 2018 - 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Central Inteligence Agency (CIA), "Transportation in Mexico ," https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/mexico/#transportation.

- 8.Dirección General Adjunta de Aviación . Agencia Federal de Aviación Civil, Directorio de Aeropuertos (Comandancias Regionales y de aeropuerto) (XLS) 2021. https://www.gob.mx/afac/acciones-y-programas/directorio-282636 (accessed February 20, 2023) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan C., Wang S., Xiao F., ce Gao D. A multi-level energy performance diagnosis method for energy information poor buildings. Energy. Apr. 2015;83:189–203. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2015.02.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geng Y., Ji W., Lin B., Hong J., Zhu Y. Building energy performance diagnosis using energy bills and weather data. Energy Build. Aug. 2018;172:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2018.04.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guidance manual: airport greenhouse gas emissions management. Nov. 2009. www.aci.aero [Online]. Available:

- 12.Alba S.O., Manana M. Energy research in airports: a review. Energies. 2016;9(5) doi: 10.3390/en9050349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greer F., Rakas J., Horvath A. vol. 15. IOP Publishing Ltd; Oct. 01, 2020. Airports and environmental sustainability: a comprehensive review. (Environmental Research Letters). 10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koroneos C., Xydis G., Polyzakis A. The optimal use of renewable energy sources—the case of the new international 'Makedonia' airport of Thessaloniki, Greece. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. Aug. 2010;14(6):1622–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2010.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.AENA “Corporate responsibility report 2014 aeropuertos españoles navegación aérea (AENA) 2015. www.aena.es/csee/Satellite/sostenibilidad/es/Page/1237564421395//Informe-anual.html (first ed.),” Madrid, Spain.

- 16.Yildiz O.F., Yilmaz M., Celik A. Reduction of energy consumption and CO2 emissions of HVAC system in airport terminal buildings. Build. Environ. Jan. 2022;208 doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Upham P., Thomas C., Gillingwater D., Raper D. Environmental capacity and airport operations: current issues and future prospects. J Air Transp Manag. May 2003;9(3):145–151. doi: 10.1016/S0969-6997(02)00078-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baxter G., Srisaeng P., Wild G. An assessment of airport sustainability, Part 2—energy management at Copenhagen airport. Resources. May 2018;7(2):32. doi: 10.3390/resources7020032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malik K. Assessment of energy consumption pattern and energy conservation potential at Indian airports. J. Constr. Dev. Ctries. (JCDC) 2017;22(1):97–119. doi: 10.21315/jcdc2017.22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdallah A.S.H., Makram A., Abdel-Azim Nayel M. Energy audit and evaluation of indoor environment condition inside Assiut International Airport terminal building, Egypt. Ain Shams Eng. J. Sep. 2021;12(3):3241–3253. doi: 10.1016/j.asej.2021.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jurado Bolaños C., Lizcano Sandoval Y. Facultad de Ingeniería; 2015. Calculo de la huella de carbono Aeropuerto el dorado. Bogota: Universidad Libre. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nuñez Baladrón A.N. Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingeniería. 2015. Concepto Aeropuerto Verde. Medidas de reducción de emisiones en aeropuertos y aplicación al Aeropuerto de Sevilla. Sevilla. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balaras C.A., Dascalaki E., Gaglia A., Droutsa K. Energy conservation potential, HVAC installations and operational issues in Hellenic airports. Energy Build. 2003;35(11):1105–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2003.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perdamaian L.G., Budiarto R., Ridwan M.K. Scenarios to reduce electricity consumption and CO2 emission at terminal 3 soekarno-hatta international airport. Procedia Environ Sci. 2013;17:576–585. doi: 10.1016/j.proenv.2013.02.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sher F., et al. Fully solar powered Doncaster Sheffield Airport: energy evaluation, glare analysis and CO2 mitigation. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assessments. Jun. 2021;45 doi: 10.1016/j.seta.2021.101122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silvester S., Beella S.K., van Timmeren A., Bauer P., Quist J., van Dijk S. Exploring design scenarios for large-scale implementation of electric vehicles; the Amsterdam Airport Schiphol case. J. Clean. Prod. Jun. 2013;48:211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.07.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sher F., et al. Fully solar powered Doncaster Sheffield Airport: energy evaluation, glare analysis and CO2 mitigation. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assessments. Jun. 2021;45 doi: 10.1016/j.seta.2021.101122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Organization for Standardization Energy performance of buildings-Overarching EPB assessment-Part 2: explanation and justification of ISO 52000-2. Jun. 2017. www.iso.org [Online]. Available:

- 29.International Organization for Standardization Energy performance of buildings-Overarching EPB assessment-Part 1: general framework and procedures ISO 52000-1. Jun. 2017. www.iso.org Online]. Available:

- 30.International Organization for Standarization . Aug. 2018. Energy Management Systems ISO 50001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.International Organization for Standardization . 2018. Greenhouse Gases-Part 1: Specification with Guidance at the Organization Level for Quantification and Reporting of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Removals ISO 14064. [Google Scholar]

- 32.CRE, NOM-016-CRE-2016. Mexico. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33.SECRE, NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-001-SECRE-2010 . 2010. Especificaciones del gas natural. Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serrano-Guevara O.S., Huertas J.I., Quirama L.F., Mogro A.E. Energy efficiency of heavy-duty vehicles in Mexico. Energies. Jan. 2023;16(1) doi: 10.3390/en16010459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Comisión Nacional para el Ahorro de Energía . Jun. 2007. Eficiencia energética en acondicionadores de aire tipo central, paquete o dividido. Límites, métodos de prueba y etiquetado NOM-011-ENER-2006. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Norma oficial Mexicana, eficiencia enrgética en sistemas de alumbrado en edificios no residenciales NOM-007-ENER-2004. Apr. 2005. Comité Consultivo Nacional de Normalización para la Preservación y Uso Racional de los Recursos Energéticos. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Secretaria del Trabajo y Prevension Social . Dec. 2008. Condiciones de iluminación en los centros de trabajo NOM-025-STPS-2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.SEMARNAT and INECC . 2019. Inventario Nacional de Emisiones de Gases y Compuestos de Efecto Invernadero. Mexico City. [Google Scholar]

- 39.IPCC . 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution. [Google Scholar]

- 40.SEMARNAT . Mexico City; 2019. Inventario Nacional de Emisiones de Contaminantes Criterio (INEM) [Google Scholar]

- 41.INECC . Factores de emisión para los diferentes tipos de combustibles fósiles y alternativos que se consumen en México. 2014. pp. 1–46.https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/110131/CGCCDBC_2014_FE_tipos_combustibles_fosiles.pdf (accessed March 6, 2023) [Google Scholar]

- 42.DBEIS and DEFR . 2022. Greenhouse Gas Reporting: Conversion Factors 2021. London. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Servicio Meteorológico Nacional Mexico (SMN), “Información Estadística Climatológica,” NORMALES CLIMATOLÓGICAS ESTACION: 00021046 HUEJOTZINGO PERIODO: 1951-2010. . Accessed: February. 6, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/es/climatologia/informacion-climatologica/informacion-estadistica-climatologica.