Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Lymphatic valves are specialized structures in collecting lymphatic vessels and are crucial for preventing retrograde lymph flow. Mutations in valve-forming genes have been clinically implicated in the pathology of congenital lymphedema. Lymphatic valves form when oscillatory shear stress from lymph flow signals through the PI3K/AKT pathway to promote the transcription of valve-forming genes that trigger the growth and maintenance of lymphatic valves. Conventionally, in many cell types, AKT is phosphorylated at Ser473 by the mTORC2 (mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2). However, mTORC2 has not yet been implicated in lymphatic valve formation.

METHODS:

In vivo and in vitro techniques were used to investigate the role of Rictor, a critical component of mTORC2, in lymphatic endothelium.

RESULTS:

Here, we showed that embryonic and postnatal lymphatic deletion of Rictor, a critical component of mTORC2, led to a significant decrease in lymphatic valves and prevented the maturation of collecting lymphatic vessels. RICTOR knockdown in human dermal lymphatic endothelial cells not only reduced the level of activated AKT and the expression of valve-forming genes under no-flow conditions but also abolished the upregulation of AKT activity and valve-forming genes in response to oscillatory shear stress. We further showed that the AKT target, FOXO1 (forkhead box protein O1), a repressor of lymphatic valve formation, had increased nuclear activity in Rictor knockout mesenteric lymphatic endothelial cells in vivo. Deletion of Foxo1 in Rictor knockout mice restored the number of valves to control levels in lymphatic vessels of the ear and mesentery.

CONCLUSIONS:

Our work identifies a novel role for RICTOR in the mechanotransduction signaling pathway, wherein it activates AKT and prevents the nuclear accumulation of the valve repressor, FOXO1, which ultimately enables the formation and maintenance of lymphatic valves.

Keywords: AKT1 protein, cellular mechanotransduction, FOXO1 protein, lymphatic system, mice, RICTOR protein

Highlights.

RictorLEC-KO mice experience lymphatic valve loss and a defect in collecting lymphatic vessel transport.

RICTOR knockdown human dermal lymphatic endothelial cells in vitro fail to upregulate critical lymphatic valve genes, such as FOXC2 and ITGA9, in response to oscillatory shear stress.

RICTOR knockdown human dermal lymphatic endothelial cells in vitro fail to phosphorylate and activate AKT (protein kinase B) in response to oscillatory shear stress.

RictorLEC-KO mice exhibit nuclear retention of FOXO1 (forkhead box protein O1) in lymphatic endothelial cells.

Double deletion of Foxo1 and Rictor rescues the valve loss seen in RictorLEC-KO mice.

The lymphatic vasculature is critical for maintaining tissue fluid homeostasis in the body. Interstitial fluids, immune cells, and lipids enter lymphatic capillaries to form lymph, and collecting lymphatic vessels transport lymph to the bloodstream.1–5 Intraluminal bicuspid valves in collecting lymphatic vessels prevent retrograde lymph flow generated by the hydrostatic pressure gradient to maintain the unidirectional lymph flow. Lymphatic valves are comprised of dual lymphatic endothelial cell (LEC) layers with an extracellular matrix core.6 Defective lymphatic valves have been implicated in human lymphatic diseases, such as lymphedema, which is characterized by tissue swelling due to the accumulation of interstitial fluids, adipose tissue deposition, fibrosis, and susceptibility to infections.7–9 Mutations in many valve genes that are involved in human congenital lymphedema, such as FOXC2 (forkhead box protein C2), GATA2 (GATA-binding factor 2), ITGA9 (integrin subunit alpha 9), and CX43, cause valve defects in their knockout mouse models, implicating defective lymphatic valves in lymphedema.10–18

The formation of lymphatic valves is regulated by the mechanotransduction signaling pathway. LECs at vessel branch points experience oscillatory shear stress (OSS) due to disturbed lymph flow, and they respond by upregulating valve transcription factors, such as Prox1 (prospero homeobox protein 1), Foxc2, and Gata2, to form lymphatic valves.19 OSS recognized by the mechanosensors on the cell membrane of LECs activates the β-catenin and PI3K (phosphoinositide 3-kinase)/AKT (protein kinase B) cellular pathways to regulate valve formation and maintenance.20,21 As a key component in the mechanotransduction signaling pathway, the activity of AKT regulates many cellular processes, including lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic valve formation.22 In support of this, injection of a small molecule AKT activator into WT mice augmented lymphatic valve growth.20 In many cell types, the activation of AKT requires the phosphorylation of 2 critical residues: threonine 308, which is phosphorylated by the PDK1 (protein-dependent kinase 1), and serine 473, which is phosphorylated by the mTORC2 (mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2).23 mTORC2 is involved in many downstream cellular events, such as cell migration, proliferation, survival, and cytoskeletal rearrangement.23 RICTOR is a critical component in the multiprotein mTORC2 complex, and its interaction with the mTOR protein is crucial for Ser473 (Serine 473) phosphorylation of AKT.24 However, whether the function of RICTOR in AKT activation is important in the lymphatic vasculature remains unknown. Here, we showed that lymphatic-specific deletion of Rictor led to a significant loss of lymphatic valves in the mesenteric, ear, axillary, and diaphragm lymphatic vessels. RICTOR knockdown in cultured human dermal LECs (hdLECs) decreased AKT activation and reduced lymphatic valve gene expression. We showed that Rictor knockout LECs, in vivo, displayed increased levels of nuclear FOXO1 (forkhead box protein O1), which is a downstream target of AKT and a potent repressor of lymphatic valve gene expression. Furthermore, we showed that ablation of Foxo1 restored the number of valves to control levels in Rictor knockout mice. Therefore, RICTOR-induced AKT activation in the mechanotransduction signaling pathway is critical for lymphatic valve formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Availability

The data that supports the findings of the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Animals and Treatments

Mouse husbandry and experiments were conducted under the guidelines of the University of South Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The Rictorflox/flox and Foxo1flox/flox mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. The use of Foxo1flox/flox and Prox1CreERT2 mice has been described before.25–29 The Prox1CreERT2 and Prox1-GFP mouse models were procured through the material transfer agreement. The R26Foxo1AAA mouse model was generated by Ingenious. All the mouse models were maintained on a mixed genetic background (C57BL/6J×FVB). Embryonic deletion of Rictor was achieved by 2 intraperitoneal injections of tamoxifen (5 mg) into pregnant dams on embryonic day (E) 13.5 and E14.5. Postnatal deletion of Rictor and Foxo1 was induced by injecting pups with 100-μg tamoxifen on postnatal day (P) 1 and P3. BODIPY FL C-16 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) dissolved in olive oil was administered to P14 pups by oral gavage at a concentration of 10 μg/μL. The pups were then isolated from the mother for 45 minutes before being euthanized and analyzed for functional triglyceride transportation. The sex difference was not determined, and data from both sexes were combined.

Ex Vivo Analysis of Lymphatic Vessel Length, Lymphatic Valve, and Vessel Diameter Quantification

Pregnant dams and Prox1-GFP reporter–expressing postnatal pups were euthanized using the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee–approved methods and analyzed at the indicated experimental timepoint. To collect embryos, the uterine horn was detached from the dam and placed in cold PBS. Embryonic mesenteries were pinned ex vivo on a homemade Sylgard 184 pad. For postnatal pups, the mesentery was imaged in situ (without being detached from the body). Both embryonic and postnatal mesenteries were imaged under a Zeiss V16 microscope. The length of GFP-positive large collecting lymphatic vessels appearing from the lymph node and the thinner branched precollector vessels toward the intestinal wall29 (Figures 1B, 1C, and 3) were measured using the segmented line tool in Fiji (ImageJ), and the GFPhigh valves were counted using the multipoint tool in Fiji. Ears from postnatal pups were excised from the mouse body at the indicated timepoint. The inner dermal layer was separated from the outer collagen layer. After the dermal layer was pinned on a Sylgard 184 pad, it was analyzed under a Zeiss V16 microscope. In the ear, collecting lymphatic vessels toward the base of the ear were measured using the line tool in Fiji, and GFPhigh valves were counted using the multipoint tool in Fiji. The diameter of lymphatic vessels was measured using the line tool in Fiji.30 Four knockout mice and 4 littermate controls were used for each experiment.

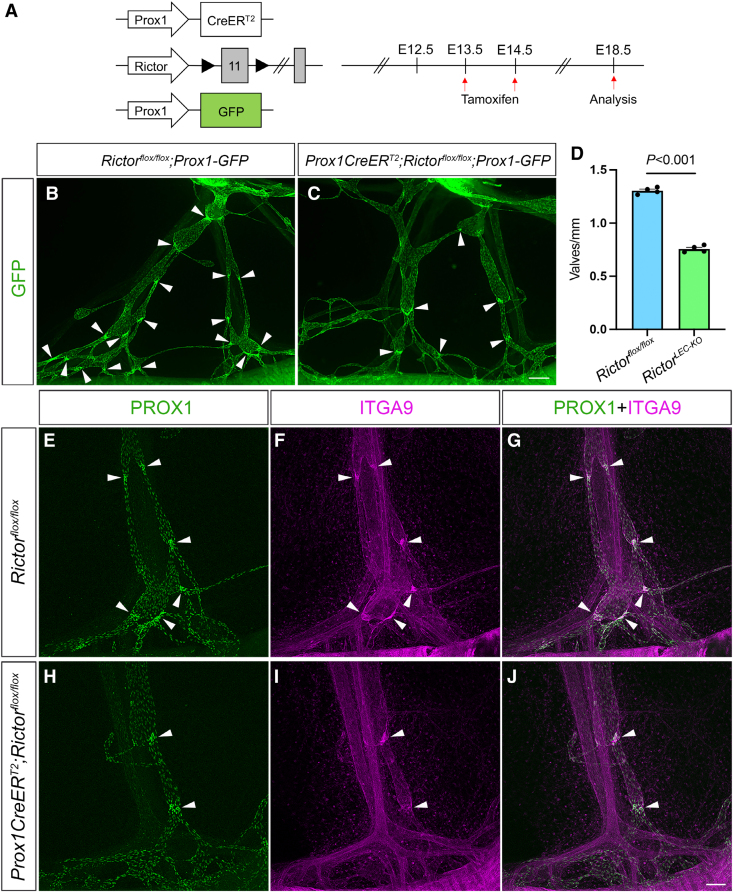

Figure 1.

Rictor deletion leads to valve loss in embryonic mesentery. A, Tamoxifen injection schedule for embryonic Rictor deletion. B and C, Fluorescence images of the mesenteric lymphatic vessels from the lymph node (top) to the gut (bottom) represented by GFP (green fluorescent protein) expression from embryonic day (E) 18.5 embryos. Arrowheads point to GFPhigh valves. D, Valves per millimeter from each mesentery. E through J, Whole-mount immunostaining of E18.5 mesenteries after E13.5/E14.5 tamoxifen injections with PROX1 (prospero homeobox 1; green) and ITGA9 (integrin subunit alpha 9; magenta). G, Merged image of E and F. J, Merged image of H and I. Arrowheads point to Prox1high valves. Scale bars are 200 µm for B and C and 100 µm for E through J. All values are mean±SEM. Four control and 4 RictorLEC-KO mesenteries were used for every analysis. Analysis was performed using the unpaired Student t test.

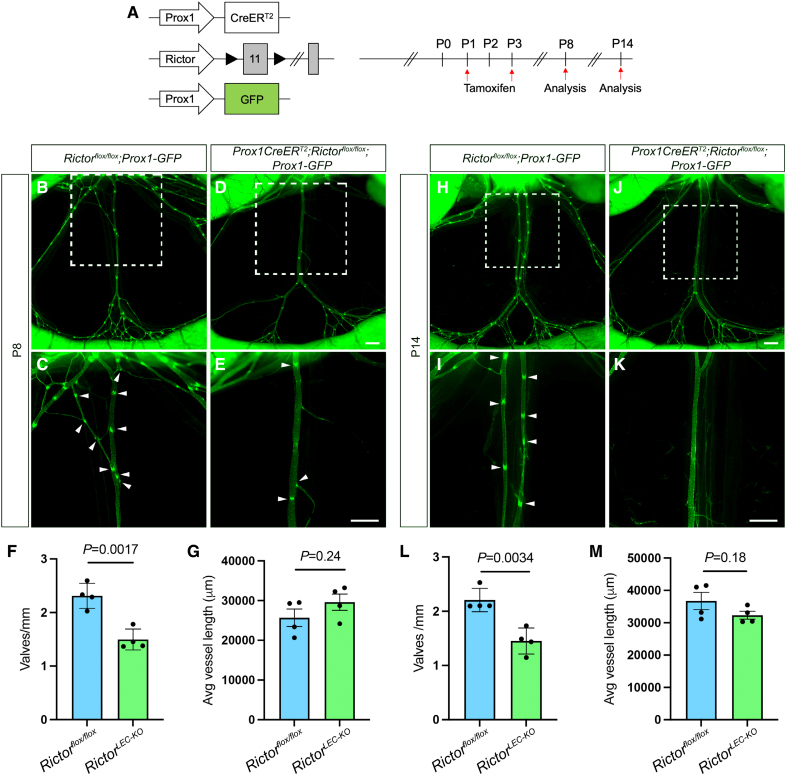

Figure 3.

Postnatal deletion of Rictor leads to valve loss in the mesentery. A, Tamoxifen injection procedure for postnatal deletion of Rictor. B through E and H through K, Fluorescence images of the mesenteric lymphatic vasculature represented by GFP (green fluorescent protein) expression from postnatal day (P) 8 (B–E) and P14 (H–K). C, E, I, and K, Higher magnification images of the white squared areas from B, D, H, and J. F, Valves per millimeter from each mesentery of control (blue bar) and RictorLEC-KO (green bar) at P8. G, Average vessel length of each vessel from control (blue bar) and RictorLEC-KO (green bar) at P8. L, Valves per millimeter from each mesentery of control (blue bar) and RictorLEC-KO (green bar) at P14. M, Average vessel length of each vessel from control (blue bar) and RictorLEC-KO (green bar) at P14. Scale bars are 500 µm in B through E and H through K. All values are mean±SEM. Four control and 4 RictorLEC-KO mesenteries were used for the analysis. Analysis was performed using the unpaired Student t test.

Quantification of Cell Proliferation

P21 ear skin tissue was stained with GFP and Ki67, and confocal images were acquired. GFP and Ki67 double-positive LECs were counted using the multipoint tool in Fiji. The percentage of Ki67-positive cells was obtained by dividing the Ki67+ cells by the GFP+ cells and multiplying the ratio by 100. Four mice from each group were used for analysis.

Smooth Muscle Cell Coverage and LYVE1-Expression Area Quantification

GFP/SMA (smooth muscle actin) or GFP/LYVE1 stained slides were imaged under a Zeiss V16 microscope at ×32 and ×25 magnification, respectively. The GFP/SMA or GFP/LYVE1 images were merged using the color and merge tool in Fiji (ImageJ). The areas of GFP-positive collecting lymphatic vessels, avoiding the smooth muscle cell (SMC) rich blood vessels in GFP/SMA and LYVE1-positive capillaries in the GFP/LYVE1 tissues, were measured using the polygonal tool in Fiji, and the areas were saved as a region of interest (ROI). The ROI was then applied to individual GFP and SMA or GFP and LYVE1 V16 images, and the threshold of color was set using the image and adjust threshold option in Fiji. The threshold allows the measurement of the area fraction of staining, which is then totaled individually. SMA% is obtained by dividing the total SMA area by the total GFP area and multiplying the ratio by 100. Similarly, LYVE1% is obtained by dividing the total LYVE1 area by the total GFP area and multiplying the ratio by 100.

Quantification of BODIPY Transport per Vessel Area

Mice were euthanized after 45 minutes after BODIPY FL C-16 administration. Postnatal mesenteries were imaged ex vivo under a fluorescence Zeiss V16 microscope. The vessel area was demarcated using the polygonal tool in Fiji, and the region was saved as ROI. The BODIPY fluorescence in the vessel area was then set to a threshold from which an area fraction of fluorescence per vessel area was obtained. This ratio was multiplied by 100 to obtain a % decrease in BODIOPY fluorescent area per vessel area.

Whole-Mount Immunostaining Procedure

All procedures were performed at 4 °C on an orbital shaker (Belly Dancer, IBI Scientific) unless otherwise specified. Tissues were harvested and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde overnight. Fixed tissues were washed with PBS thrice for 10 minutes each time. The tissues were then permeabilized with PBS+0.3% Triton X-100 (PBST) for 1 hour after which they were blocked with 3% donkey serum in PBST for 2 hours. Primary antibodies were prepared in PBST, added to the tissue, and allowed to incubate overnight. The next day, the primary antibody was washed off with PBST (5× of 7 minutes each). The secondary and conjugated antibodies were prepared in PBST, added to the tissues, and left to incubate in a blackout box at room temperature for 1.5 hours on an orbital shaker (Belly Button, IBI Scientific). Tissues were then washed 4× of 10 minutes each with PBST. For nuclear visualization, DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Invitrogen) was dissolved in PBS, added to the tissues, and allowed to incubate for 10 minutes after which it was washed off with PBS once. The tissue was mounted onto glass slides (Superfrost Plus Microscope Slides, Fisherbrand), covered in ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant (Invitrogen), and stored at 4 °C overnight.30 The slides were imaged using a Leica SP8 confocal microscope and acquired using Fiji, and figures were created using Adobe Photoshop. The primary and secondary antibodies used are listed in Table S1.

Calculation of FOXO1 Expression in LEC Nucleus In Vivo

Mouse embryonic mesenteries were harvested and stained with PROX1 and FOXO1. PROX1 positive nuclei were labeled using the polygonal tool in ImageJ (Fiji), and their areas were saved as an ROI. The ROI was applied to the FOXO1 staining, and the threshold of staining was adjusted accordingly. Next, the analyze features on Fiji <Set measurements, <Area, <Area fraction, and <RawIntDensity were selected sequentially. The Measure button on the ROI tab of Fiji was selected, and the results were pasted into an Excel sheet. Each RawIntDen*Area fraction was multiplied, and the average RawIntDen of Foxo1 was calculated by the average of RawIntDen (SUM).

Cell Culture, shRNA, and OSS

Primary hdLECs (PromoCell, C-12216) were cultured in EBM-V2 (PromoCell, C-22121) media on fibronectin (20 μL)-coated 6 well plates. A culture passage of ≤6 was used for the knockdown experiments. For the experiment, hdLECs were infected with lentiviral particles either harboring an shRNA against RICTOR or a scramble shRNA construct expressing GFP for 48 hours. The hdLECs were then taken off infection and exposed to OSS conditions (0.3 dynes/cm2) on a test tube rocker (Thermolyne Speci-Mix Aliquot Mixer Model M71015, Barnstead International) in a 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2. The lentiviral shRICTOR and shScramble were purchased from VectorBuilder.30

RNA Isolation and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from hdLECs using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA from the total RNA was synthesized using the Advantage RT-for-PCR kit (Takara) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. qPCR (quantitative polymerase chain reaction) was performed with Taqman probes (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher) in a QuantStudio 6 real-time system (Applied Biosystems). The Cq (the quantification cycle) value of each gene was normalized to the Cq value of GAPDH.

Western Blot

Western blot was performed according to standard protocol. Protein lysates were harvested, after OSS treatment for 30 minutes or 48 hours, using RIPA buffer (Pierce, Thermo Fisher). Protein gel electrophoresis was performed using the Invitrogen mini gel tank, the protein transfer was performed using the iBlot 2 Dry Blotting system, and the antibodies were blotted using the iBind Western Systems. Protein bands were visualized using the SuperSignal West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher). Densitometric analysis was performed using the Imagelab 6.1 software as instructed by BIORAD. Western blot quantification was performed according to the protocol for densitometric quantification by BIORAD. Each protein band was normalized to its corresponding ACTB (beta-actin) band.

Statistics

All data are depicted as mean±SEM. Data sets comprising 2 groups were analyzed using an unpaired 2-sided Student t test, and significance was achieved at P<0.05. Data sets containing 1 independent variable were analyzed using 1-way ANOVA with the Tukey multiple comparison test, and data sets containing 2 independent variables were analyzed using 2-way ANOVA with the Tukey multiple comparison test to determine significant differences at P<0.05. GraphPad Prism software (version 9) was used to plot quantified data and perform statistical analysis.

Study Approval

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the University of South Florida guidelines and were approved by the respective Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All procedures complied with the standards stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health, revised 2011).

RESULTS

Embryonic Deletion of Rictor Leads to Loss of Valves in Mesenteric Lymphatic Vessels

To investigate the unknown role of Rictor, a critical component of mTORC2, in lymphatic valve formation, we used a tamoxifen-inducible LEC-specific Cre (Cre recombinase) line Prox1CreERT2,31 to conditionally delete exon 11 of Rictor (Rictorflox/flox) in the lymphatics, but not in the blood vasculature. To aid in visualizing the lymphatic vasculature, an LEC reporter line, Prox1-GFP (green fluorescent protein),32 was crossed with the Prox1CreERT2;Rictorflox/flox mice to generate the Prox1CreERT2;Rictorflox/flox;Prox1-GFP mice (also referred to as RictorLEC-KO). Pregnant dams were injected with tamoxifen on E13.5 and E14.5 when the embryonic mesenteric lymphatic vessels began to develop (Figure 1A). The mesenteries were analyzed on E18.5 when the lymphatic vessel network is established as well as the first timepoint when mature valves were observed (Figure 1A). Although there were no structural differences between the lymphatic vessels of RictorLEC-KO and control embryos, RictorLEC-KO mesenteric vessels had fewer GFPhigh positive valves compared with the control (Figure 1B and 1C, arrowheads). To confirm the reduction in GFPhigh valves in the RictorLEC-KO mesentery, we measured the length (millimeter) of each vessel and counted the number of GFPhigh valves per vessel to generate valves per millimeter.30 RictorLEC-KO mesenteries had 40% fewer valves per millimeter compared with control animals (Figure 1D). Whole-mount immunostaining for PROX1 revealed fewer PROX1high valves in RictorLEC-KO lymphatic vessels compared with control (Figure 1E and 1H, arrowheads). Valve LECs deposit fibronectin EIIIA as part of their extracellular matrix. The fibronectin receptor protein, integrin α9, a receptor for fibronectin, is highly expressed in mature lymphatic valve leaflets, and its deficiency during development leads to morphologically abnormal and dysfunctional lymphatic valves.11,33,34 Whole-mount immunostaining revealed that although the RictorLEC-KO mesenteries have fewer valves compared with the control, the expression of integrin α9 is retained in the remaining valves (Figure 1F, 1G, 1I, and 1J). Together, Rictor is needed for the formation of adequate lymphatic valves during embryonic development of the lymphatic vasculature.

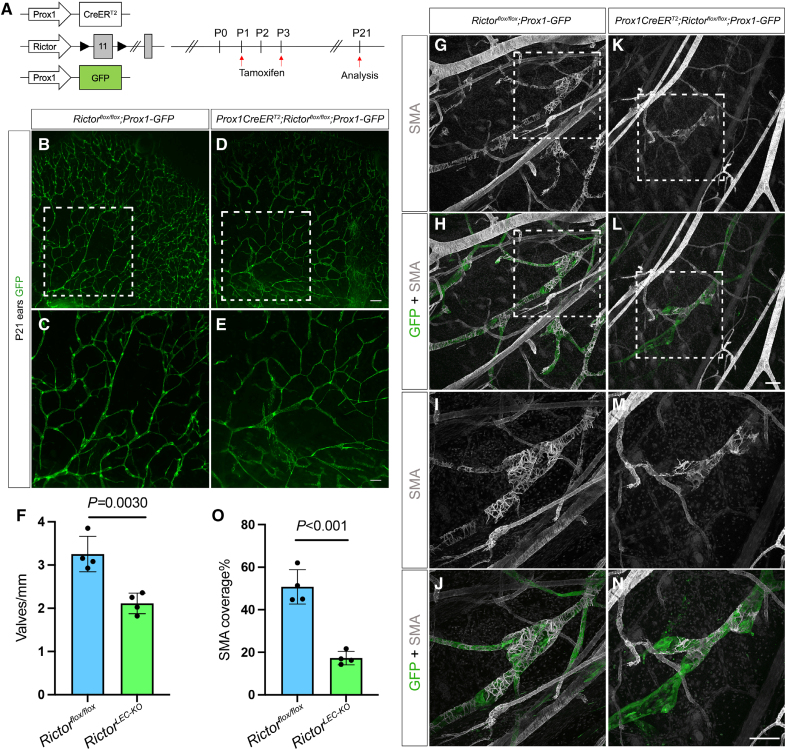

Ear Lymphatic Vessels Lose Valves and SMC Coverage on Postnatal Rictor Deletion

In addition to the embryonic deletion of Rictor, we induced lymphatic-specific Rictor deletion at P1 and P3 (P1/P3 tamoxifen) via tamoxifen injection and analyzed the ear lymphatic vessels at P21 (Figure 2A). Because we were not able to find a working Rictor antibody for immunostaining to confirm the deletion of the protein, we bred Prox1CreERT2;Rosa26mT/mG mice to verify the deletion efficiency and the specificity of the Cre line. To induce recombination, we injected tamoxifen at P1 and P3, the same tamoxifen injection schedule as in Figure 2A, and analyzed various tissues at P8, P14, and P21 (Figure S1A). We found that Cre-induced mGFP expression was present in all lymphatic vessels in both mesentery and ears from various stages (Figure S1B through S1BB). Immunostaining for PROX1 confirmed that the GFP signal was restricted to only PROX1-expressing LECs (Figure S1H through S1J). Because lymphatic valves in the ear begin developing after birth, it is an ideal tissue to investigate the role of Rictor in the formation of lymphatic valves postnatally. Like the embryonic mesentery, the RictorLEC-KO ears showed fewer GFPhigh valves in the collecting lymphatic vessels compared with the control ears (Figure 2B through 2E). Quantification revealed a 35% decrease in valves per millimeter in RictorLEC-KO ears compared with control ears (Figure 2F). Because we deleted Rictor before lymphatic vessels grow into the ear, our data show that Rictor regulates the formation of lymphatic valves, which is consistent with the results from embryonic deletion (Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Rictor deletion leads to valve loss and reduced smooth muscle cell (SMC) coverage in the ear lymphatics. A, Tamoxifen injection schedule for postnatal deletion of Rictor. B through E, Fluorescence images of the ear lymphatics from control (B and C) and RictorLEC-KO (D and E) represented by GFP (green fluorescent protein) expression at postnatal day (P) 21. C and E, Higher magnification images of the white boxed region from B and D. F, Valves per millimeter from each mouse of control (blue bar) and RictorLEC-KO (green bar). G through N, Whole-mount immunostaining of P21 ears with P1/P3 tamoxifen injection from control and RictorLEC-KO with SMA (smooth muscle actin; gray) and GFP (green). I, J, M, and N, Higher magnification images of the white boxed region from G, H, K, and L. O, Percentage of SMA coverage from each ear of control (blue bar) and RictorLEC-KO (green bar). Scale bars are 500 µm for B and D, 200 µm for C and E, and 100 µm for G through N. All values are mean±SEM. Four control and 4 RictorLEC-KO mice were used for every analysis. Analysis was performed using the unpaired Student t test.

Given that mTORC2 signaling is traditionally known to control cellular proliferation, we performed whole-mount immunostaining of P21 control and RictorLEC-KO ear skin tissue with antibodies against GFP and Ki67 (antigen kiel 67), a widely used proliferation marker35 (Figure S2A and S2B). Quantification of Ki67+/GFP+ and all GFP+ LECs revealed no significant difference in the percentage of Ki67+/GFP+ LECs between Rictor knockout and control animals (Figure S2C). Hence, the loss of valves in RictorLEC-KO tissues cannot be due to reduced LEC proliferation.

Because we found that Rictor regulates lymphatic valve development, we next wanted to investigate whether Rictor regulates other distinct features of collecting lymphatic vessels. One of the hallmarks of collecting lymphatic vessel maturation is the recruitment of SMCs to the vessel wall, specifically to the lymphangion regions that are devoid of valves.36 To test whether Rictor regulates SMC recruitment, we performed whole-mount immunostaining for αSMA in the P21 ear skin of RictorLEC-KO and control animals and subsequently quantified SMA coverage in the collecting lymphatic vessels. While the collecting lymphatic vessels in the control ear had abundant and continuous SMC coverage as revealed by SMA staining (Figure 2G through 2J), the RictorLEC-KO collecting lymphatic vessels had sparse coverage of SMCs (Figure 2K through 2N). Quantification of the amount of SMA-positive areas revealed a significant reduction in SMC coverage on the RictorLEC-KO ear collecting lymphatic vessels compared with the control (Figure 2O; 17% versus 48%). This suggests that Rictor plays a role in SMC recruitment to the collecting lymphatic vessels during development, and its deletion leads to incomplete vessel maturation.

Rictor Knockdown Regulates the Expression of SMC Recruitment Factors In Vitro

To further investigate the defect in SMC recruitment after Rictor deletion, we examined the expression of different vascular SMC recruitment factors in vitro using cultured hdLECs treated with (1) scramble shRNA (short-hairpin RNA; scramble control) and no flow (static), (2) hdLECs treated with shRICTOR and static, (3) hdLECs treated with scramble control and flow (OSS), and (4) hdLECs treated with shRICTOR and OSS.30 We analyzed the expression of PDGFB (platelet-derived growth factor B), PDGFD (platelet-derived growth factor D), EDN-1 (endothelin-1), TGFβ1 (transforming growth factor beta-1), ANGPT1 (angiopoietin-1), and HB-EGF (heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor) because they have previously been described as blood endothelial cell–derived pericyte recruitment factors.37 In addition, we investigated the expression of endothelial-expressed S1PR1 and SMAD5 because they are required for SMC migration and recruitment, respectively.38,39 A qRT-PCR was performed to check the mRNA expression, and the amount of secreted protein was quantified for selected proteins using available ELISA kits. Our qRT-PCR results showed that (1) RICTOR mRNA was efficiently knocked down using shRICTOR (Figure S3A); (2) RICTOR knockdown in hdLECs leads to the downregulation of SMC recruitment factors, such as PDGFD, TGFβ1, ANGPT1, and S1PR1, under static conditions (Figure S3A) compared with scramble; (3) the expression of some recruitment genes, such as PDGFD, TGFβ1, and ANGPT1, are downregulated in response to OSS compared with static in scramble control hdLECs (Figure S3A), supporting previous findings that the same shear stress that promotes lymphatic valve formation also negatively regulates SMC recruitment40; (4) RICTOR knockdown in hdLECs leads to the downregulation of recruitment genes, such as PDGFD and TGFβ1, in both static and OSS (Figure S3A) compared with scramble; (5) endothelial-derived SMC recruitment and migration factors, such as PDGFB, EDN-1, and SMAD5, are unchanged in all 4 groups; and (6) HB-EGF is the only gene, which is upregulated in response to shRICTOR treatment in hdLECs in both static and OSS conditions compared with scramble (Figure S3A). At the protein level, our ELISA results showed that (1) EC (endothelial cell)-secreted SMC recruitment factors, such as PDGFB, TGFβ1, and HB-EGF, were upregulated in response to shRICTOR treatment in both static and OSS conditions compared with scramble (Figure S3B); (2) the protein expression of HB-EGF was upregulated in response to OSS compared with static in scramble hdLECs (Figure S3B); and (3) the secreted protein expression of PDGFD, ET-1 (endothelin-1), and ANGPT1 remained unchanged among the 4 groups. Our data suggest that mTORC2 signaling may have a potential role in lymphatic SMC recruitment.

Atypical LYVE1 Expression in RictorLEC-KO Collecting Lymphatic Vessels

The observed decrease in valve formation and SMC recruitment to RictorLEC-KO ear collecting lymphatic vessels suggested a maturation defect. During maturation, collecting vessel LECs downregulate the expression of LYVE1 (lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1), whereas capillary LECs retain high LYVE1 expression.2 To confirm the presence of a maturation defect, we performed whole-mount immunostaining for LYVE1 in RictorLEC-KO and control mice (Figure S2D through S2L). Collecting lymphatic vessels of the P21 control ear skin, located at the base of the ear, did not display any LYVE1 staining (Figure S2I and S2J). The transition area between the collecting vessels and capillaries (ie, precollectors) displayed a gradual increase in LYVE1 expression in the controls (Figure S2E and S2F). In contrast, the collecting lymphatic vessels from the RictorLEC-KO ear skin retained abnormally high expression of LYVE1 at the ear base (Figure S2K and S2L), and the transition area maintained high expression of LYVE1 (Figure S2G and S2H). After we quantified the LYVE1+ area and normalized it to the total area of collecting lymphatic vessels, we found that 57% of collecting vessels were LYVE1+ in RictorLEC-KO mice, while only 8% of control vessels were LYVE1+ (Figure S2M). This demonstrates that the lymphatic vessels have a more capillary-like phenotype on Rictor deletion and confirms that mTORC2 signaling is required for collecting lymphatic vessel maturation.

Postnatal Deletion of Rictor Leads to Valve Loss in Mesenteric Lymphatic Vessels

After lymphatic valves are formed, they require constant mechanotransduction signaling to maintain their structure.20 To investigate the role of mTORC2 signaling in lymphatic valve formation and maintenance postnatally in mice, we induced the postnatal deletion of Rictor by administrating tamoxifen at P1 and P3 after the mesenteric lymphatic vessel network and valves were formed. Mesenteric lymphatic vessels were analyzed at P8, P14, and P21 (Figure 3A; Figure S4A). Both RictorLEC-KO and Rictorflox/flox littermate control were administrated the same dosage of tamoxifen. The recombination efficiency of the Prox1CreERT2 was confirmed using Prox1CreERT2;Rosa26mT/mG mesenteric lymphatic vessels at P8, P14, and P21 (Figure S1B through S1V). Although the overall morphology of the lymphatic vasculature was not altered on Rictor deletion, the number of GFPhigh valves was decreased in the RictorLEC-KO mesentery compared with their littermate controls at all the 3 stages (Figure 3B through 3E, and 3H through 3K; Figure S4B through S4E, arrowheads). To confirm that valve loss is not due to a reduction in vessel length, we measured the length of each collecting vessel and its associated precollectors and normalized valve number to the vessel length (mm) to obtain valves per millimeter. While the number of valves per millimeter was significantly lower in the RictorLEC-KO mesentery compared with controls at P8, P14, and P21 (Figure 3F, 35% decrease; Figure 3L, 36% decrease; and Figure S4F, 35% decrease), the average length of each vessel did not differ significantly (Figure 3G and 3M; Figure S4G). Thus, in addition to embryonic valve development, Rictor also regulates postnatal lymphatic valve maintenance.

Valve Loss in Rictor Knockout Mice Is Not Organ-Specific

To investigate whether the loss of lymphatic valves in RictorLEC-KO mice was tissue-specific, we analyzed the axillary skin and diaphragm lymphatic vessels of the control and RictorLEC-KO mice on postnatal tamoxifen administration according to the schedule in Figure S4A. We found that there were fewer GFPhigh valves in the RictorLEC-KO axillary and diaphragm lymphatic vessels compared with their respective controls (Figure S4H through S4L). On quantification, we confirmed that there was a significant decrease in valves per millimeter in RictorLEC-KO axillary (62.5% decrease) and diaphragm (63% decrease) lymphatic vessels compared with controls (Figure S4J and S4M). Hence, we can conclude that the loss of valves on postnatal Rictor deletion in vivo is consistent among the lymphatic vessels of various organs.

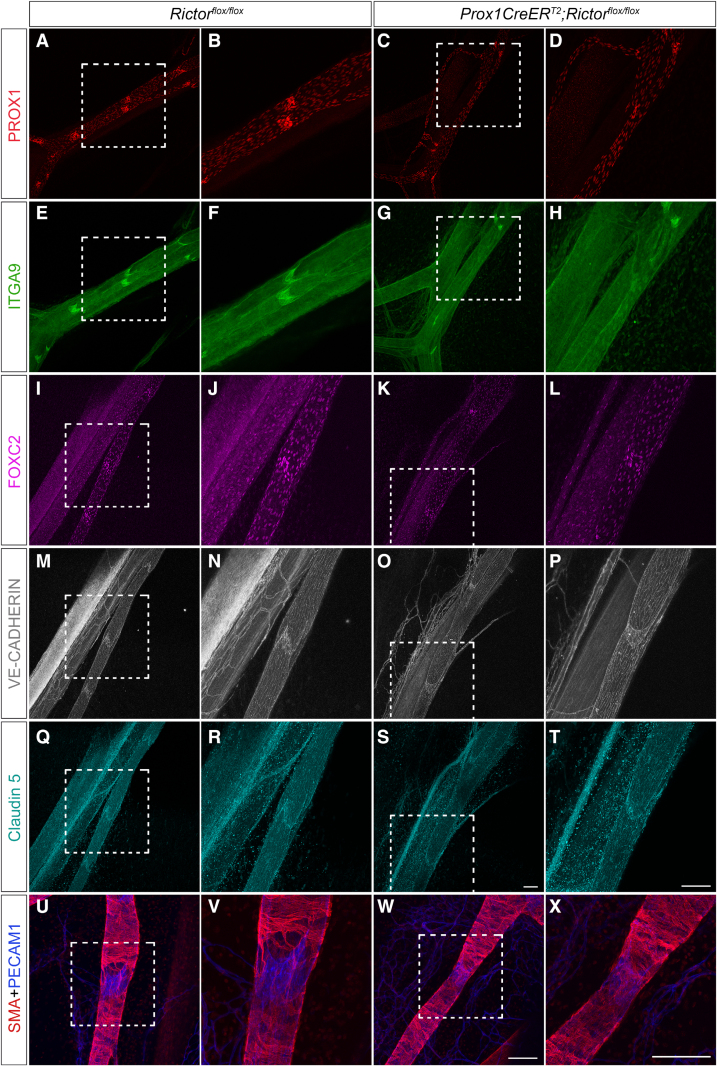

Valves in Postnatal RictorLEC-KO Mesenteric Lymphatic Vessels Retain Similar Morphology and Gene Expression as Control Valves

To investigate whether the remaining valves in RictorLEC-KO lymphatics retained the characteristics of wild-type valves, we performed whole-mount immunostaining of P8 mesenteries (tamoxifen schedule same as Figure 3A). The expression of PROX1, a marker for lymphatic identity,2–5,41 remained unchanged in control and RictorLEC-KO valves. However, the number of PROX1high valves was clearly reduced in RictorLEC-KO vessels (Figure 4A through 4D). Integrin α9 is highly expressed in valve LECs designating the bileaflet structure of a lymphatic valve. Itga9-deficient mice develop chylothorax and die perinatally, and this phenomenon is attributed specifically to the lack of lymphatic valves.11,33 Like the control valves, RictorLEC-KO remaining valves expressed a higher level of integrin α9 (Figure 4E through 4H) compared with the lymphangion (vessel segment flanked by 2 valves). Control valve LECs expressed elevated levels of FOXC2 compared with the lymphangion LECs as previously reported (Figure 4I and 4J).29,42 The valve LECs in RictorLEC-KO still expressed a higher level of FOXC2 compared with the lymphangion LECs (Figure 4I through 4L). Junctional proteins are imperative in maintaining vessel integrity and serving as signaling molecules that drive downstream regulation of valve genes. VE-cadherin is an adherens junction protein that regulates mechanotransduction signaling in response to OSS.20 VE-cadherin expression and localization appeared similar in LECs of RictorLEC-KO and control (Figure 4M through 4P). Claudin-5 is a tight junction protein, and its expression is required for collecting lymphatic vessel integrity because Cldn5 het mice have dilated and leaky lymphatics after a UV-B irradiation challenge.43 RictorLEC-KO and control LECs showed no disparity in claudin-5 expression (Figure 4Q through 4T). In contrast to the ears, control and RictorLEC-KO P14 mesenteric vessels displayed similar SMC wrapping patterns around the lymphangion (Figures 2G through 2N and 4U through 4X). In summary, these data show that RictorLEC-KO mesenteries maintain structurally intact lymphatic vessels, however, with fewer valves.

Figure 4.

The expression of valve genes, junctional proteins, and SMA (smooth muscle actin) is present in the lymphatic vessels of RictorLEC-KO mesentery with postnatal deletion. A through X, Representative whole-mount immunostaining of postnatal day (P) 8 mesenteries with P1/P3 tamoxifen injection from control and RictorLEC-KO with PROX1 (prospero homeobox 1; red; A–D), ITGA9 (integrin subunit alpha 9; green; E–H), FOXC2 (forkhead box protein C2; magenta; I–L), VE-cadherin (vascular endothelial-cadherin; gray; M–P), claudin-5 (cyan; Q–T), SMA (smooth muscle alpha actin; red; U–X), and PECAM1 (platelet and endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1; blue; U–X). B, D, F, H, J, L, N, P, R, T, V, and X, Higher magnification images of the white squared areas from A, C, E, G, I, K, M, O, Q, S, U, and W. Scale bars are 100 µm for A through X. Four controls and 4 knockouts were used in the analysis.

RictorLEC-KO Collecting Lymphatic Vessels Have Reduced Lymph Transport

To assess whether RictorLEC-KO mice had impaired lymph transport, we performed a functional BODIPY FL C-16 (4, 4-difluoro-5,7-dimethyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-hexadecanoic acid) assay. BODIPY is a neutral lipophilic dye that emits bright green fluorescence on binding to phospholipids.44 P14 control and RictorLEC-KO mice were administered BODIPY FL C-16 (10 μg) after postnatal Rictor deletion (Figure S5A). Mesenteric collecting lymphatic vessels were imaged ex vivo 45 minutes after the oral gavage. On average, in 45 minutes, 6 collecting lymphatic vessels from the mouse duodenum to the jejunum successfully transported the BODIPY dye indicated by a bright green fluorescence (data not shown). However, the collecting vessels from RictorLEC-KO appeared to have reduced BODIPY dye area. After we quantified the BODIPY areas and normalized them to the total vessel area, RictorLEC-KO mesenteric collecting lymphatic vessels exhibited only 39% BODIPY area per vessel area compared with 74% in control vessels (Figure S5B through S5D).

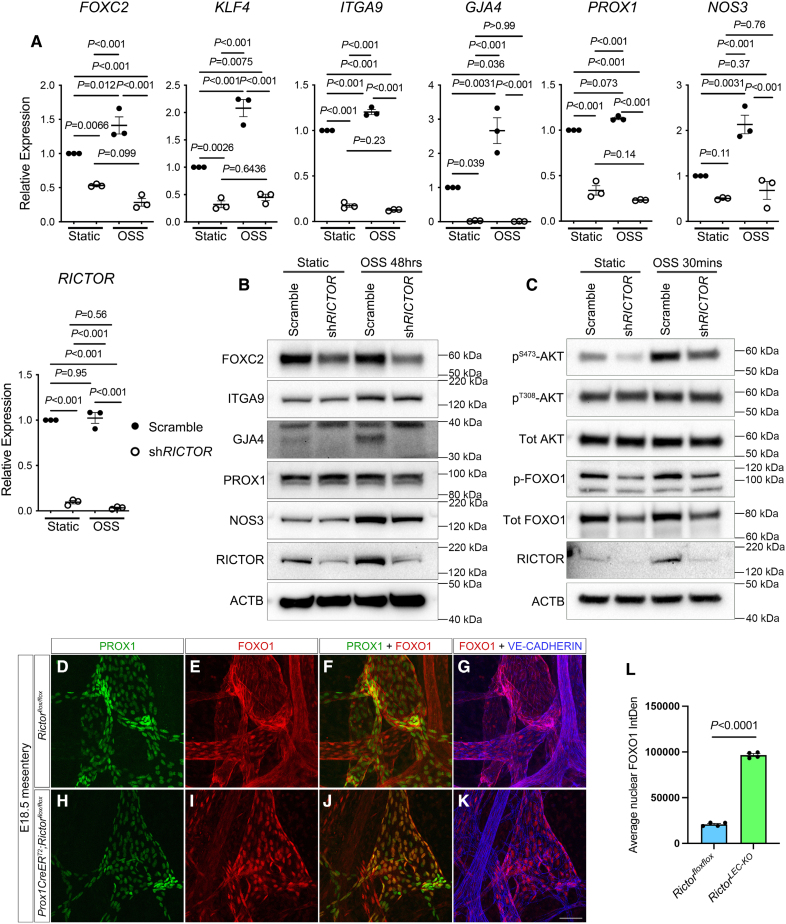

RICTOR Knockdown Impairs the Upregulation of Valve Genes in Response to OSS Due to Reduced AKT Activity

LECs recognize OSS generated by oscillatory lymph flow and signal via the mechanotransduction pathway to activate the expression of valve genes, such as Prox1, Foxc2, and Gata2, which leads to the formation of valves.19 Because lymphatic-specific deletion of Rictor led to defective lymphatic valve formation and maintenance, we investigated the role of Rictor in regulating the expression of valve genes in vitro. We performed qRT-PCR (quantitative real time-polymerase chain reaction) and Western blot to identify the expression of common valve and flow-responsive genes, such as PROX1, FOXC2, ITGA9, GJA4 (gap junction protein alpha 4), NOS3 (nitric oxide synthase 3), and KLF4, in cultured hdLECs treated with scramble control or shRICTOR and exposed to static or OSS conditions. We confirmed that RICTOR was efficiently knocked down with shRNA treatment using qRT-PCR and Western blot in both static and OSS conditions (Figure 5A and 5B; Figure S6A). The increased expression of the valve and flow-responsive genes, such as FOXC2, ITGA9, GJA4, and NOS3, in the presence of OSS has been reported before in scramble-treated cells29,45 (Figure 5A and 5B). Additionally, our qRT-PCR results showed that (1) critical valve genes, such as FOXC2, KLF4, ITGA9, GJA4, and PROX1, were downregulated in response to shRICTOR treatment under static condition compared with the scramble control and (2) the expression of FOXC2, KLF4, ITGA9, GJA4, PROX1, and NOS3 was downregulated in shRICTOR treatment even in the presence of OSS compared with the scramble control (Figure 5A). On the protein level, our Western blot results confirmed the upregulation of critical valve genes, such as ITGA9, GJA4, and NOS3, in response to OSS compared with scramble control under static conditions (Figure 5B; Figure S6A). Additionally, we showed that (1) RICTOR knockdown led to the downregulation of FOXC2 protein under static condition compared with the control (Figure 5B; Figure S6A); (2) the protein expression of ITGA9, GJA4, PROX1, and NOS3 remained unchanged on shRICTOR treatment compared with the scramble control under static condition; (3) in the presence of OSS, RICTOR knockdown led to the downregulation of FOXC2 and ITGA9 proteins compared with the scramble control (Figure 5B; Figure S6A); and (4) the protein expression of NOS3 and PROX1 remained unchanged on shRICTOR treatment compared with the scramble in the presence of OSS. These data confirmed that RICTOR regulates the expression of many critical valve and flow-responsive genes in response to OSS. Because Rictor activates AKT through serine 473 phosphorylation in many cell types, we next investigated the activity of AKT on RICTOR knockdown in LECs. Our Western blot data showed that the level of phospho-AKT (Ser473) was significantly upregulated in response to the 30-minute OSS treatment (Figure 5C; Figure S6B). However, this trend of upregulation was impaired in shRICTOR-treated hdLECs, suggesting that RICTOR regulates AKT activation in response to OSS in LECs (Figure 5C; Figure S6B). The expression of total AKT between the groups remained unchanged. In contrast to phospho-AKT (Ser473), the levels of phospho-AKT (threonine 308) were not changed in response to shRICTOR with or without OSS treatment, which supports previous reports that PDK1, not RICTOR, activates AKT through threonine 308 phosphorylation.24 Intriguingly, the level of RICTOR itself was upregulated significantly in response to the 30-minute OSS treatment (Figure 5C; Figure S6B), which indicates that RICTOR is upstream of AKT in the mechanotransduction signaling pathway.

Figure 5.

Loss of Rictor leads to downregulation in valve genes and increased nuclear FOXO1 (forkhead box protein O1) due to reduced AKT activity. A, qRT-PCR (quantitative real time-polymerase chain reaction) performed for indicated genes in human dermal lymphatic endothelial cells (hdLECs) transfected with a control scramble (closed circles) or shRICTOR (open circles) and exposed to either static or oscillatory shear stress (OSS) conditions (48 hours). B, Western blot was performed for the indicated genes using hdLECs transfected with a control scramble or shRICTOR and exposed to either static or OSS conditions (48 hours). C, Western blot was performed in hdLECs transfected with a control scramble or shRICTOR and exposed to OSS conditions for 30 minutes. D through K, Whole-mount immunostaining was performed for PROX1 (prospero homeobox 1; green), FOXO1 (forkhead box protein O1; red), and VE (vascular endothelial)-cadherin (blue) on E18.5 mesenteries (tamoxifen E13.5/14.5). L, Quantification of FOXO1 nuclear staining E18.5 mesenteric collecting lymphatic vessels. Scale bars are 50 µm in D through K. Four control and 4 RictorLEC-KO embryonic mesenteries were used for the analysis in D through K. Analysis was performed using the 2-way ANOVA with the Tukey multiple comparison test in A and the unpaired Student t test in L. ACTB indicates beta actin; AKT, protein kinase B; FOXC2, forkhead box protein C2; GJA4, gap junction protein alpha 4; ITGA9, integrin subunit alpha 9; NOS3, nitric oxide synthase 3; and RICTOR, RPTOR independent companion of mTOR complex 2.

Embryonic Deletion of Rictor Leads to Increased Nuclear Retention of Foxo1 in LECs

FOXO1 is a member of the FoxO (forkhead box O) class subfamily of the forkhead transcription factors and is involved in glucose metabolism, cell proliferation, and tumor suppression.46 Previously, we have shown that nuclear FOXO1 represses lymphatic valve genes and deletion of Foxo1 embryonically and postnatally induces the formation of new valves.29 AKT-induced phosphorylation of FOXO1 results in the translocation of FOXO1 out of the nucleus, which attenuates the FOXO1-mediated repression of valve genes and promotes valve formation.29 Because we showed that AKT phosphorylation was inhibited in the absence of Rictor in vitro, we hypothesized that the loss of Rictor results in the increased nuclear retention of FOXO1. Western blot results revealed that the level of p-FOXO1 (phosphorylated FOXO1), which is nonnuclear FOXO1, was upregulated in response to OSS compared with static when treated with scramble. However, treatment with shRICTOR led to reduced phosphorylation of FOXO1 under both static and OSS conditions (Figure 5C; Figure S6). Total FOXO1 remained unchanged between the groups. Furthermore, we performed whole-mount immunostaining of FOXO1 in E18.5 RictorLEC-KO and littermate control mesenteries (tamoxifen schedule from Figure 1A). In control mesenteric LECs, FOXO1 staining is mostly in the cytoplasm (Figure 5E through 5G); however, RictorLEC-KO mesenteric LECs showed intense FOXO1 staining in the nuclei (Figure 5I through 5K). We quantified the intensity of FOXO1 in PROX1+ mesenteric LEC nuclei and found a ≈300% increase in FOXO1 nuclear localization in RictorLEC-KO mesenteries compared with control (Figure 5L). These data together confirm that RICTOR regulates the cellular localization of FOXO1 through AKT phosphorylation.

Generation of a Conditional Foxo1 Nuclear Retention Mouse Model

Our data revealed that Rictor deletion leads to increased nuclear FOXO1 in LECs in vivo. To investigate if excess nuclear retention of FOXO1 inhibits lymphatic valve formation, we generated a knock-in mouse model with increased nuclear retention of FOXO1. AKT phosphorylates 3 residues in the wild-type murine Foxo1 that leads to FOXO1 trafficking from the nucleus: threonine 32, serine 253, and serine 315.47 In our mouse model, these residues were mutated to alanine (Figure S7A). In the targeting construct, the expression of the mutated mouse Foxo1 cDNA is contingent on the Cre-mediated excision of an upstream floxed STOP codon under the control of dual promoters: cytomegalovirus and EF-1α (elongation factor-1 alpha 1). The targeting construct was integrated into the R26 locus to generate a mutated FOXO1 protein that cannot be phosphorylated by AKT and constitutively remains in the nucleus. Additionally, an IRES sequence followed by a tdTomato reporter was linked to the mutated Foxo1AAA cDNA, which resulted in a red fluorescence signal in the cells with overexpression of the mutated FOXO1 protein. Therefore, this new mouse model is referred to as Rosa26-Foxo1AAA-tdTomato (R26Foxo1AAA; Figure S7A). We bred Prox1CreERT2 with R26Foxo1AAA and the Prox1-GFP reporter strain to generate Prox1CreERT2; R26Foxo1AAA;Prox1-GFP mice for conditional overexpression of Foxo1AAA protein in LECs (henceforth referred to as R26LEC-Foxo1AAA). The littermates without the Prox1CreERT2 allele were used as controls. Tamoxifen was injected at P1/P3, and postnatal mesentery tissues were analyzed at P6 (Figure S7B). As expected, the lymphatic vessels in the R26LEC-Foxo1AAA mesentery had fewer valves compared with the control (Figure S7C through S7F, arrowheads). Quantification revealed a 65% decrease in valves per millimeter in the R26LEC-Foxo1AAA mice compared with control animals (Figure S7G). These data strongly demonstrate that nuclear FOXO1 is a strong repressor for lymphatic valve formation and provides a mechanism for how the nuclear accumulation of FOXO1 caused by Rictor deletion results in the loss of lymphatic valves in vivo.

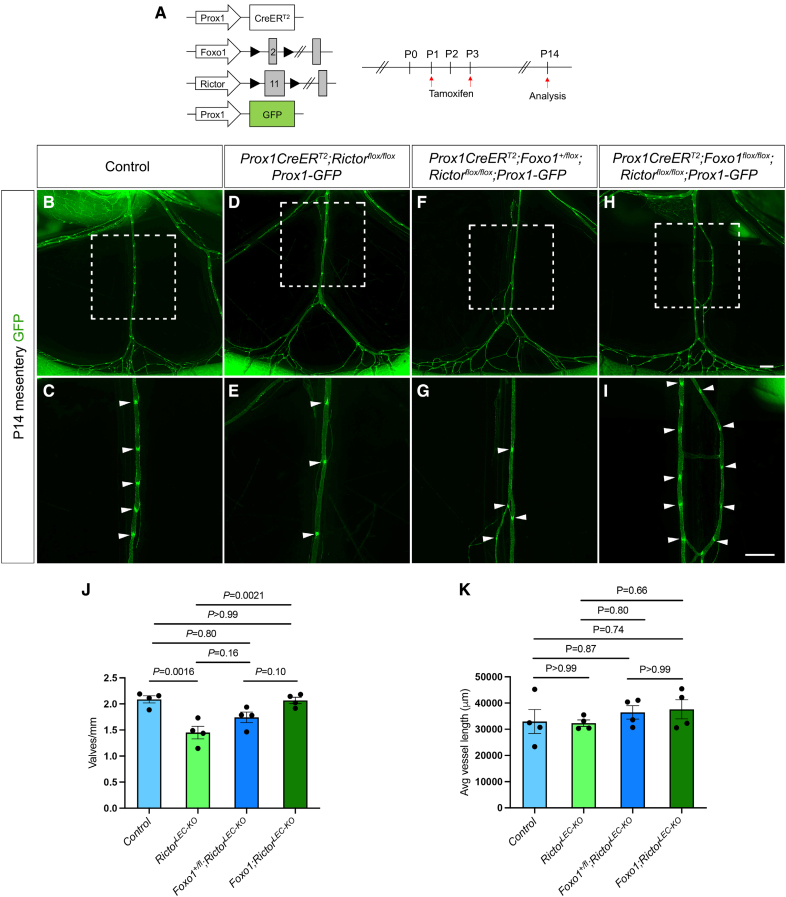

Homozygous Deletion of Foxo1 in Rictor Knockout Mouse Model Rescues the Loss of Valves in Mesenteric Lymphatics

We previously showed that LEC-specific Foxo1 ablation promotes the growth of new valves in wild-type mesenteric lymphatics and rescues valve loss in the Foxc2 heterozygous mouse model of lymphedema.29,48 Moreover, Rictor deletion increased the nuclear localization of FOXO1 in LECs in vivo, which was recapitulated in the R26LEC-Foxo1AAA mice (Figure 5L; Figure S7C through S7F). Therefore, we hypothesized that the deletion of Foxo1 would rescue the valve loss observed in RictorLEC-KO mice. We bred Foxo1flox/flox mice with Rictorflox/flox mice to create a double floxed mouse model (Foxo1flox/flox;Rictorflox/flox) and bred them with Prox1CreERT2 and Prox1-GFP reporter mice to generate double knockouts. This method allowed us to delete 1 or 2 alleles of Foxo1 to analyze the Prox1CreERT2;Foxo1+/flox;Rictorflox/flox and the Prox1CreERT2;Foxo1flox/flox;Rictorflox/flox mice (Figure 6A). We normalized the valve number on each vessel to the length of each vessel and found that while the number of GFPhigh valves per millimeter was significantly reduced in RictorLEC-KO mesentery, complete deletion of Foxo1 restored the valves per millimeter to control levels (Figure 6D, 6E, and 6H through 6J; Figure S8D, S8E, and S8Hthrough S8J). Although Foxo1 heterozygotes did not significantly reverse the valve loss in the Rictor knockouts, valve number per millimeter was partially increased (Figure 6F, 6G, and 6J; Figure S8F, S8G, and S8J). Moreover, double knockouts for Foxo1 and Rictor did not present any major defects in the mesenteric lymphatic vasculature in both Foxo1+/flox;RictorLEC-KO and Foxo1;RictorLEC-KO mice shown by no changes in average vessel length between the mice models (Figure 6K; Figure S8K). To show that the new valves produced by the Foxo1;RictorLEC-KO mesenteric lymphatic vessels were like the control valves, we performed whole-mount immunostaining of P14 control and Foxo1;RictorLEC-KO mesenteries. Like the control mesenteric lymphatic valve LECs, the Foxo1;RictorLEC-KO valves displayed brighter FOXC2, PROX1, and ITGA9 staining compared with the lymphangion (Figure S9A through S9P). Also, there was no difference in PECAM1 (platelet and endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1) and claudin-5 staining between the control and Foxo1;RictorLEC-KO mesenteric lymphatic vessels (Figure S9A through S9H). The Foxo1;RictorLEC-KO mesenteric collecting lymphatic vessels also exhibited abundant SMC coverage on the lymphangion, like the controls, represented by SMA staining (Figure S9I through S9L). Thus, the knockout of the valve repressor, Foxo1, led to a complete restoration of valve formation in RictorLEC-KO mice mesentery.

Figure 6.

Postnatal deletion of Foxo1 (forkhead box protein O1) in mesentery rescues valve loss in RictorLEC-KO mice. A, Tamoxifen injection procedure for postnatal deletion of Foxo1 and Rictor. B through I, Fluorescence images of the mesenteric lymphatic vasculature presented by GFP (green fluorescent protein) expression from postnatal day (P) 14. C, E, G, and I, Higher magnification images of the white squared areas from B, D, F, and H. Arrowheads point toward GFPhigh valves. J, Valves per millimeter from each mesentery: control (blue bar), RictorLEC-KO (green bar), Prox1CreERT2;Foxo1+/flox;Rictorflox/flox (Foxo1+/flox;RictorLEC-KO; dark blue bar), and Prox1CreERT2;Foxo1flox/flox;Rictorflox/flox (Foxo1;RictorLEC-KO; dark green bar). K, Average vessel length from each mesentery: control (blue bar), RictorLEC-KO (green bar), Prox1CreERT2;Foxo1flox/flox;Rictorflox/flox (Foxo1+/flox;RictorLEC-KO; dark blue bar), and Prox1CreERT2;Foxo1flox/flox;Rictorflox/flox (Foxo1;RictorLEC-KO; dark green bar). Scale bars are 500 µm in B through I. All values are mean±SEM. Four controls and 4 knockouts were used in the analysis. Analysis was performed using 1-way ANOVA with the Tukey multiple comparison test.

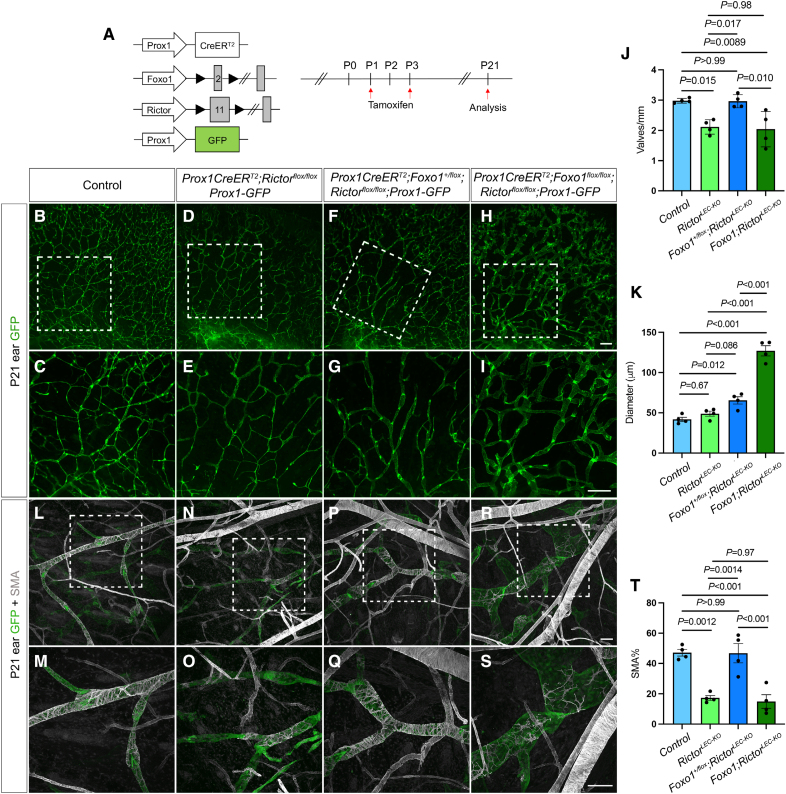

Postnatal Heterozygous Deletion of Foxo1 Restores Valve Loss and SMC Recruitment in RictorLEC-KO Mouse Ear Lymphatics

We have shown that deletion of Foxo1 can restore valve loss in RictorLEC-KO mesentery (Figure 6B and 6K; Figure S8B through S8J). Next, we tested whether the deletion of Foxo1 in RictorLEC-KO LECs can also rescue the valve loss in the ear tissue. Rictor and Foxo1 were deleted by tamoxifen injections on P1 and P3, and the ears were analyzed on P21 (Figure 7A). Our data showed that (1) heterozygous deletion of Foxo1 (Foxo1+/flox;RictorLEC-KO) in the ears led to a significant increase in valves per millimeter compared with the RictorLEC-KO ears and restored the valve number to control levels (Figure 7B through 7G and 7J), (2) heterozygous deletion of Foxo1 (Foxo1+/flox;RictorLEC-KO) in the ears significantly increased vessel diameter compared with the control (Figure 7B, 7C, 7F, 7G, and 7K), and (3) homozygous deletion of Foxo1 (Foxo1;RictorLEC-KO) resulted in a grossly significant increase in vessel diameter along with significantly fewer valves per millimeter (Figure 7H through 7K) compared with the control and Foxo1+/flox;RictorLEC-KO groups (Figure 7B, 7C, 7F, and 7G). The dilation of ear vessels in the homozygous Foxo1 knockouts was consistent with our previous data due to increased proliferation caused by Foxo1 inactivation during development, which prevents the formation of new valves.29 Additionally, we performed whole-mount immunostaining of SMA on control, RictorLEC-KO, Foxo1+/flox;RictorLEC-KO, and Foxo1;RictorLEC-KO ears and quantified the SMA coverage on ear lymphatic vessels of each group. We showed that Foxo1 heterozygotes on the RictorLEC-KO background restored the SMC coverage levels to that of control ears (Figure 7L, 7Q, and 7T). However, the complete knockout of Foxo1 in RictorLEC-KO ears did not rescue the loss of SMC coverage in RictorLEC-KO ear lymphatic vessels due to lymphatic vessel hyperplasia (Figure 7R and 7S). In addition to SMC coverage, we also performed whole-mount immunostaining of LYVE1 on P21 ear lymphatic vessels in control and Foxo1+flox;RictorLEC-KO mice and discovered that although valves per vessel length were rescued in Foxo1+flox;RictorLEC-KO to control levels, the collecting lymphatic vessels retained higher LYVE1 expression (Figure S10). This shows that the reduction in valves is due to the loss of mechanotransduction signaling and is not linked to collecting lymphatic vessel maturation. These data demonstrate that during tissue development, Foxo1 heterozygosity is sufficient to rescue valve loss and SMC recruitment in the absence of Rictor, and complete knockout of Foxo1 drives exaggerated LEC growth, which prevents valve formation and SMC coverage.

Figure 7.

Postnatal Foxo1 deletion rescues valve defect in RictorLEC-KO ears. A, Tamoxifen injection schedule to delete Foxo1 and Rictor. B through I, Fluorescence images of postnatal day (P) 21 ear lymphatic vessels identified with GFP (green fluorescent protein) expression. C, E, G, and I, Higher magnification images of white squared areas in B, D, F, and H. J, Valves per millimeter from control (blue bar), RictorLEC-KO (green bar), Prox1CreERT2;Foxo1+/flox;Rictorflox/flox (Foxo1+/flox;RictorLEC-KO; dark blue bar), and Prox1CreERT2;Foxo1flox/flox;Rictorflox/flox (Foxo1;RictorLEC-KO; dark green bar). K, Diameter of collecting lymphatic vessels from each ear of control (blue bar), RictorLEC-KO (green bar), Prox1CreERT2;Foxo1+/flox;Rictorflox/flox (Foxo1+/flox;RictorLEC-KO; dark blue bar), and Prox1CreERT2;Foxo1flox/flox;Rictorflox/flox (Foxo1;RictorLEC-KO; dark green bar). L through S, Whole-mount immunostaining of P21 ears (P1/P3 tamoxifen injection) with SMA (smooth muscle actin; gray) and GFP (green). M, O, Q, and S, Higher magnification images of the white squared areas in L, N, P, and R. T, Percentage of SMA coverage from each ear of control (blue bar), RictorLEC-KO (green bar), Prox1CreERT2;Foxo1+/flox;Rictorflox/flox (Foxo1+/flox;RictorLEC-KO; dark blue bar), and Prox1CreERT2;Foxo1flox/flox;Rictorflox/flox (Foxo1;RictorLEC-KO; dark green bar). Scale bars are 500 µm for B through I and 100 µm for L through S. All values are mean±SEM. Four control and 4 knockout (KO) mice were used for every analysis. Analysis was performed using the 1-way ANOVA and the Tukey multiple comparison test in J, K, and T.

DISCUSSION

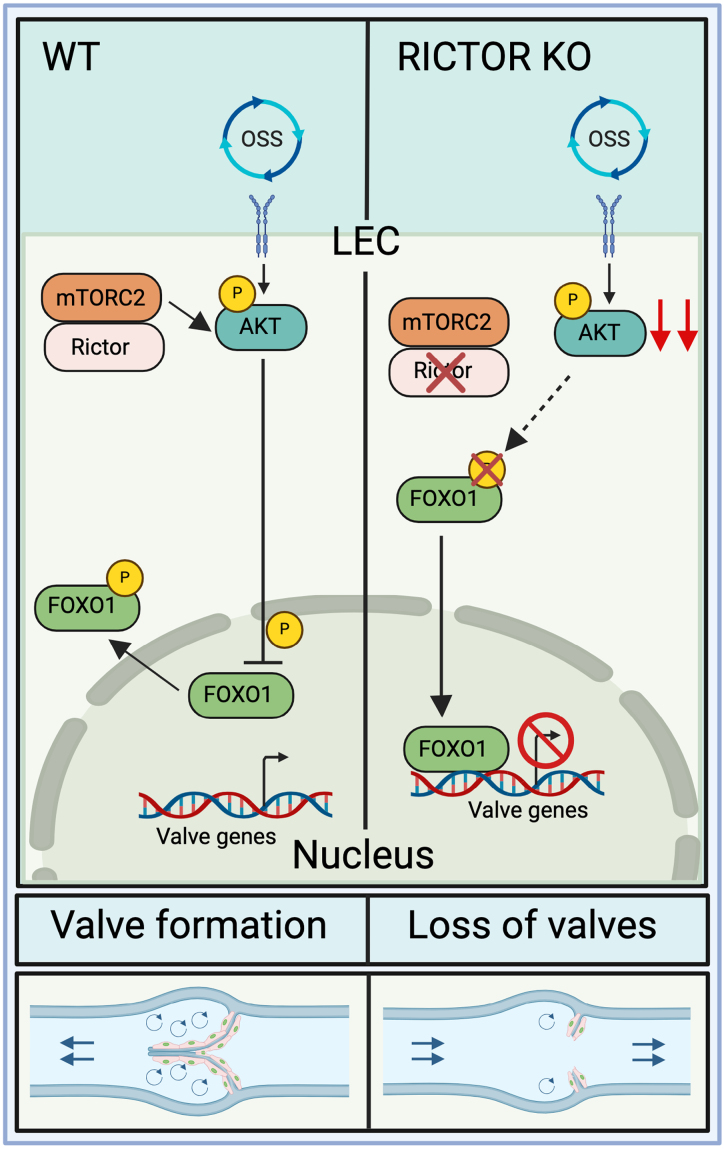

In our previous study, we showed that AKT activity was increased in response to OSS in LECs, which is critical for the upregulation of valve-forming genes in the mechanotransduction signaling pathway.20,29 Additionally, exogenous stimulation of AKT led to the production of new lymphatic valves in wild-type mice.20 These data are supported by a previous report that AKT is important for the formation of lymphatic valves.22 However, the mechanisms leading to AKT activation in LECs to stimulate lymphatic valve formation are to date unknown. In other cell types, mTORC2 signaling is involved in the phosphorylation and activation of AKT.49 Whether it does the same in the lymphatic vasculature, particularly in valve formation, is yet untested. Here, we discovered a novel role for Rictor, a crucial component of mTORC2, in the regulation of lymphatic valve formation and maintenance. The RICTOR protein assembles the components of the multiprotein kinase complex, mTORC2, and carries out downstream kinase activity. We showed that lymphatic-specific deletion of Rictor led to a significant reduction in valve number embryonically and postnatally in mice. These data were significant because the deletion of Rictor in postnatal LECs caused a 50% reduction in the lymph transport in collecting lymphatic vessels as shown by a BODIPY functional assay. Moreover, loss of Rictor severely affected the activity of AKT even under OSS, which, in turn, resulted in the decreased expression levels of valve-forming genes and increased nuclear FOXO1 accumulation, a downstream target of AKT. Because FOXO1 is a potent lymphatic valve repressor, we performed genetic ablation of Foxo1, and the valve number was restored in RictorLEC-KO mice. Therefore, our study identified the OSS-RICTOR-AKT-FOXO1 signaling axis in lymphatic valve formation (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Rictor, a critical component of mTORC2 (mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2), regulates lymphatic valve formation and maintenance via modulating AKT (protein kinase B) activation. In wild-type (WT) lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs), mTORC2 phosphorylates and activates AKT, which phosphorylates its downstream target, FOXO1 (forkhead box protein O1). FOXO1 is translocated out of the nucleus leading to the production of lymphatic valves. However, on the loss of mTORC2 signaling, reduced AKT activation leads to nuclear Foxo1 accumulation, which causes repression of valve genes, thereby causing lymphatic valve loss. KO indicates knockout; and OSS, oscillatory shear stress.

Rictor Regulates Lymphatic Valve Formation Through AKT-Nuclear Foxo1–Controlled Valve Gene Expression

Lymph flow is oscillatory at branch points of the embryonic lymphatic vasculature, and this oscillatory lymph flow stimulates the mechanotransduction signaling that initiates the activation of AKT and leads to the export of the lymphatic valve repressor, FOXO1, out of the nucleus.29 This allows the transcriptional upregulation of the lymphatic valve genes, such as Foxc2, Gata2, Prox1, Itga9, and Gja4 (Cx37), and flow-responsive genes, such as Klf4 and Klf2, which induces the formation and maintenance of lymphatic valves.2,13,40 In this study, our data revealed that mTORC2 is upstream of AKT in the mechanotransduction signaling pathway, and its critical component, RICTOR, is activated by OSS experienced by LECs during lymphatic valve formation. RICTOR phosphorylates AKT at Ser473, and AKT phosphorylates FOXO1, which causes its translocation out of the nucleus into the cytoplasm (Figure 8). We showed that when mTORC2 signaling was abolished by deletion of Rictor in LECs, there were fewer lymphatic valves in collecting lymphatic vessels in vivo, and this loss of lymphatic valves was observed in multiple types of lymphatic vessel–enriched tissues. Moreover, we revealed that the expression of important lymphatic valve genes and flow-response genes (eg, FOXC2, ITGA9, GJA4, and KLF4) were reduced in the absence of RICTOR in cultured hdLECs in vitro. The main cause of these phenotypes is due to the increased activity of FOXO1 in the RICTOR knockdown, and Rictor knockout LEC nucleus because nuclear FOXO1 inhibits the transcription of lymphatic valve genes, such as Foxc2, by directly binding to its upstream promoter.29 Additionally, we observed that valve formation was attenuated in our LEC-specific Foxo1 nuclear overexpression mouse model, R26LEC-Foxo1AAA, which confirms that increased nuclear FOXO1 inhibits the formation of lymphatic valves. These data showed that RICTOR-induced AKT signaling is involved in the mechanotransduction pathway of lymphatic valve formation and maintenance. In many cell types, the activity of mTORC2 signaling and AKT is increased in response to energetic stress, such as ligand-dependent activation by IGF (insulin growth factor) stimulation or dynamic mechanical signals experienced during tissue loading.50 Our data showed that the expression levels of RICTOR in cultured hdLECs were increased with the 30-minute OSS treatment, indicating that mTORC2 signaling is activated by shear stress in the lymphatic vasculature in a ligand-independent manner, leading to the increase of activated AKT and lymphatic valve formation. Yet, unanswered questions remain; for example, is RICTOR the only kinase in the mTORC2 complex that phosphorylates AKT?

In our postnatal lymphatic Rictor knockout mouse model, the percentage of valve loss was maintained at ≈40% up to 3 weeks after deletion, which was similar to the percentage of valve loss in Foxc2 heterozygous mice. Although the Rosa26mT/mG reporter assay indicated ≈100% deletion of Rictor, the valve number in Rictor LEC knockout mice was never reduced to zero. Additionally, our whole-mount immunostaining data of P8 mesenteries presented that the remaining lymphatic valves in the RictorLEC-KO lymphatic vasculature had the usual pattern of high expression of lymphatic valve genes (Foxc2, Prox1, and Itga9) in the valve LECs compared with the lymphangion. This suggests that although mTORC2 signaling is critical for lymphatic valve development, there are other factors upstream or downstream of mTORC2, which influence lymphatic valve formation and maintenance. Furthermore, despite that RICTOR was knocked down in cultured hdLECs, the level of phosphorylated AKT at Ser473 was not abolished but remained at a low level. Therefore, it is likely that other protein kinases in addition to RICTOR play a role in AKT activation in response to OSS. Another question is what is upstream of RICTOR in the mechanotransduction signaling pathway? Our data revealed that the protein level of RICTOR was significantly upregulated in just 30-minute flow treatment, which indicates a posttranslational modification of RICTOR in such a short period of time. However, other mechanisms, such as transcriptional regulation of RICTOR, cannot be ruled out for future studies.

Rictor Regulates Collecting Lymphatic Vessel Maturation

The mammalian lymphatic vasculature matures to form 2 distinct types of lymphatic vessels: lymphatic capillaries and collecting lymphatic vessels. Lymphatic capillaries express high levels of LYVE1, and collecting lymphatic vessels switch off the expression of LYVE1 during their maturation process.2 Additionally, collecting lymphatic vessels recruit abundant SMCs for contractile function, whereas lymphatic capillaries do no recruit SMCs.51 We showed that on postnatal Rictor deletion in mice, the SMC coverage was severely reduced on the ear collecting lymphatic vessels but not on the mesenteric vessels compared with the control. SMCs are recruited to the collecting lymphatic vessels after lymphatic valve formation, and in the postnatal mesentery, the collecting lymphatic vessels already possess most lymphatic valves.40 On the other hand, the mouse ear lymphatics develop after birth, and SMCs are not recruited until P12.52 Therefore, our results indicate that ablation of Rictor affects SMC recruitment to the collecting lymphatic vessels more in the developing vasculature than in the developed vasculature. Moreover, we showed that the Rictor knockout collecting lymphatic vessels in the ear expressed LYVE1, while the mature collecting lymphatic vessels in control mice did not. This suggests that the deletion of Rictor hampers the maturation of the lymphatics during development. Furthermore, we found that RICTOR knockdown in cultured hdLECs decreased the expression of many endothelial cell-expressed SMC recruitment factors, including PDGFD, TGFβ1, ANGPT1, and S1PR1 at the mRNA level.53–56 The upregulation seen in PDGFB but not Pdgfb was surprising on RICTOR knockdown, but not inexplicable. Mice transduced with adenoviral PDGFB exhibited displacement of SMCs away from LECs along with increased expression of LYVE1 in the ear lymphatic vessels.57

Postnatal Deletion of Foxo1 Rescues the Valve Loss in Rictor Knockout Mice

Because the R26LEC-Foxo1AAA mouse model confirmed that excess nuclear FOXO1 prevents lymphatic valve formation, we hypothesized that Foxo1 deletion in RictorLEC-KO mice would abolish the repressive activity of FOXO1 and restore valve growth to control levels. We showed that the deletion of Foxo1 induced new valves to grow in the RictorLEC-KO mice. Although valve number was not significantly increased in RictorLEC-KO mice with loss of 1 allele of Foxo1, homozygous deletion of Foxo1 completely and significantly rescued the lymphatic valve loss in Rictor knockout mesenteries. In contrast, the reduced number of valves seen in Rictor knockout ear skin tissue only required the loss of a single allele of Foxo1 to be restored to the wild-type level. These data suggest that the effect of Foxo1 inhibition works in a dose and developmental stage–dependent manner. As mentioned in the previous section, the difference is that Foxo1 and Rictor were deleted in a developed vasculature (the mesenteric vessels) versus in a developing vasculature (the ear vessels). Thus, our results suggest that LECs from developed vessels have higher nuclear FOXO1 activity than the developing vessels. Therefore, more FOXO1 is required to be translocated out of the nucleus in the developed vessels compared with actively developing vessels to stimulate lymphatic valve formation (Figure 8). Hence, complete deletion of Foxo1 was required to reverse the valve loss in RictorLEC-KO postnatal mesentery tissue, while 1 allele deletion of Foxo1 was enough to induce the growth of lymphatic valves in the ear lymphatics. Our previous work has shown that homozygous knockout of Foxo1 in the developing vasculature led to unregulated LEC proliferation, which drove the dilation of the collecting lymphatic vessels in the ears, and a defect in SMC recruitment, which explains the dilated lymphatic vessels of RictorLEC-KO;Foxo1LEC-KO ears.29

In summary, our findings reveal a critical and novel role of the mTORC2 protein, Rictor, upstream of AKT and downstream of the mechanosensing complex in the mechanotransduction signaling pathway. Our study demonstrates that OSS induced Rictor signals through AKT and inhibits nuclear Foxo1 to regulate the formation and maintenance of lymphatic valves and can serve as a potential therapeutic target for treating lymphedema.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs Taija Makinen and Young Kwon Hong for sharing the Prox1CreERT2 mice and the Prox1-GFP mice. R. Banerjee and Y. Yang performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the article. L.A. Knauer, D. Iyer, S.E. Barlow, H. Shalaby, R. Dehghan, and J.P. Scallan performed experiments and edited the article. All authors contributed to and approved the final version of the article.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants R01 HL145397 and R01 HL166981 to Y. Yang and R01 HL142905 and R01 HL164825 to J.P. Scallan and the American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship grant 827540 to D. Iyer.

Disclosures

None.

Supplemental Material

Table S1

Figures S1–S10

Major Resources Table

Supplementary Material

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ANGPT1

- angiopoietin-1

- E

- embryonic day

- EF-1α

- elongation factor-1 alpha 1

- FoxO

- forkhead box O

- FOXO1

- forkhead box protein O1

- HB-EGF

- heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor

- hdLEC

- human dermal lymphatic endothelial cell

- LEC

- lymphatic endothelial cell

- mTORC2

- mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2

- OSS

- oscillatory shear stress

- P

- postnatal day

- PBST

- PBS+0.3% Triton X-100

- PDGFB

- platelet-derived growth factor B

- PDK1

- protein-dependent kinase 1

- p-FOXO1

- phosphorylated forkhead box protein O1

- ROI

- region of interest

- SMA

- smooth muscle actin

- SMC

- smooth muscle cell

- TGFβ1

- transforming growth factor beta-1

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 2021.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/ATVBAHA.124.321164.

REFERENCES

- 1.Breslin JW, Yang Y, Scallan JP, Sweat RS, Adderley SP, Murfee WL. Lymphatic vessel network structure and physiology. Compr Physiol. 2018;9:207–299. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c180015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Y, Oliver G. Development of the mammalian lymphatic vasculature. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:888–897. doi: 10.1172/JCI71609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang Y, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Soriano-Navarro M, Srinivasan RS, Scallan JP, Singh MK, Epstein JA, Oliver G. Lymphatic endothelial progenitors bud from the cardinal vein and intersomitic vessels in mammalian embryos. Blood. 2012;120:2340–2348. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-428607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srinivasan RS, Geng X, Yang Y, Wang Y, Mukatira S, Studer M, Porto MP, Lagutin O, Oliver G. The nuclear hormone receptor Coup-TFII is required for the initiation and early maintenance of Prox1 expression in lymphatic endothelial cells. Genes Dev. 2010;24:696–707. doi: 10.1101/gad.1859310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srinivasan RS, Escobedo N, Yang Y, Interiano A, Dillard ME, Finkelstein D, Mukatira S, Gil HJ, Nurmi H, Alitalo K, et al. The Prox1-Vegfr3 feedback loop maintains the identity and the number of lymphatic endothelial cell progenitors. Genes Dev. 2014;28:2175–2187. doi: 10.1101/gad.216226.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koltowska K, Betterman KL, Harvey NL, Hogan BM. Getting out and about: the emergence and morphogenesis of the vertebrate lymphatic vasculature. Development. 2013;140:1857–1870. doi: 10.1242/dev.089565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrova TV, Karpanen T, Norrmen C, Mellor R, Tamakoshi T, Finegold D, Ferrell R, Kerjaschki D, Mortimer P, Yla-Herttuala S, et al. Defective valves and abnormal mural cell recruitment underlie lymphatic vascular failure in lymphedema distichiasis. Nat Med. 2004;10:974–981. doi: 10.1038/nm1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grada AA, Phillips TJ. Lymphedema: pathophysiology and clinical manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:1009–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neligan PC, Kung TA, Maki JH. MR lymphangiography in the treatment of lymphedema. J Surg Oncol. 2017;115:18–22. doi: 10.1002/jso.24337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kriederman BM, Myloyde TL, Witte MH, Dagenais SL, Witte CL, Rennels M, Bernas MJ, Lynch MT, Erickson RP, Caulder MS, et al. FOXC2 haploinsufficient mice are a model for human autosomal dominant lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1179–1185. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bazigou E, Xie S, Chen C, Weston A, Miura N, Sorokin L, Adams R, Muro AF, Sheppard D, Makinen T. Integrin-alpha9 is required for fibronectin matrix assembly during lymphatic valve morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2009;17:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ostergaard P, Simpson MA, Connell FC, Steward CG, Brice G, Woollard WJ, Dafou D, Kilo T, Smithson S, Lunt P, et al. Mutations in GATA2 cause primary lymphedema associated with a predisposition to acute myeloid leukemia (Emberger syndrome). Nat Genet. 2011;43:929–931. doi: 10.1038/ng.923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabine A, Bovay E, Demir CS, Kimura W, Jaquet M, Agalarov Y, Zangger N, Scallan JP, Graber W, Gulpinar E, et al. FOXC2 and fluid shear stress stabilize postnatal lymphatic vasculature. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3861–3877. doi: 10.1172/JCI80454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma GC, Liu CS, Chang SP, Yeh KT, Ke YY, Chen TH, Wang BB, Kuo SJ, Shih JC, Chen M. A recurrent ITGA9 missense mutation in human fetuses with severe chylothorax: possible correlation with poor response to fetal therapy. Prenat Diagn. 2008;28:1057–1063. doi: 10.1002/pd.2130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kazenwadel J, Betterman KL, Chong CE, Stokes PH, Lee YK, Secker GA, Agalarov Y, Demir CS, Lawrence DM, Sutton DL, et al. GATA2 is required for lymphatic vessel valve development and maintenance. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:2979–2994. doi: 10.1172/JCI78888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrell RE, Baty CJ, Kimak MA, Karlsson JM, Lawrence EC, Franke-Snyder M, Meriney SD, Feingold E, Finegold DN. GJC2 missense mutations cause human lymphedema. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:943–948. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ostergaard P, Simpson MA, Brice G, Mansour S, Connell FC, Onoufriadis A, Child AH, Hwang J, Kalidas K, Mortimer PS, et al. Rapid identification of mutations in GJC2 in primary lymphoedema using whole exome sequencing combined with linkage analysis with delineation of the phenotype. J Med Genet. 2011;48:251–255. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.085563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munger SJ, Davis MJ, Simon AM. Defective lymphatic valve development and chylothorax in mice with a lymphatic-specific deletion of Connexin43. Dev Biol. 2017;421:204–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geng X, Ho YC, Srinivasan RS. Biochemical and mechanical signals in the lymphatic vasculature. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78:5903–5923. doi: 10.1007/s00018-021-03886-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Y, Cha B, Motawe ZY, Srinivasan RS, Scallan JP. VE-cadherin is required for lymphatic valve formation and maintenance. Cell Rep. 2019;28:2397–2412.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.07.072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cha B, Geng X, Mahamud MR, Fu J, Mukherjee A, Kim Y, Jho EH, Kim TH, Kahn ML, Xia L, et al. Mechanotransduction activates canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling to promote lymphatic vascular patterning and the development of lymphatic and lymphovenous valves. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1454–1469. doi: 10.1101/gad.282400.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou F, Chang Z, Zhang L, Hong YK, Shen B, Wang B, Zhang F, Lu G, Tvorogov D, Alitalo K, et al. Akt/protein kinase B is required for lymphatic network formation, remodeling, and valve development. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:2124–2133. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jhanwar-Uniyal M, Wainwright JV, Mohan AL, Tobias ME, Murali R, Gandhi CD, Schmidt MH. Diverse signaling mechanisms of mTOR complexes: mTORC1 and mTORC2 in forming a formidable relationship. Adv Biol Regul. 2019;72:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2019.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guertin DA, Stevens DM, Thoreen CC, Burds AA, Kalaany NY, Moffat J, Brown M, Fitzgerald KJ, Sabatini DM. Ablation in mice of the mTORC components raptor, rictor, or mLST8 reveals that mTORC2 is required for signaling to Akt-FOXO and PKCalpha, but not S6K1. Dev Cell. 2006;11:859–871. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paik JH, Kollipara R, Chu G, Ji H, Xiao Y, Ding Z, Miao L, Tothova Z, Horner JW, Carrasco DR, et al. FoxOs are lineage-restricted redundant tumor suppressors and regulate endothelial cell homeostasis. Cell. 2007;128:309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sabine A, Agalarov Y, Maby-El Hajjami H, Jaquet M, Hagerling R, Pollmann C, Bebber D, Pfenniger A, Miura N, Dormond O, et al. Mechanotransduction, PROX1, and FOXC2 cooperate to control connexin37 and calcineurin during lymphatic-valve formation. Dev Cell. 2012;22:430–445. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tatin F, Taddei A, Weston A, Fuchs E, Devenport D, Tissir F, Makinen T. Planar cell polarity protein celsr1 regulates endothelial adherens junctions and directed cell rearrangements during valve morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2013;26:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rouhani SJ, Eccles JD, Riccardi P, Peske JD, Tewalt EF, Cohen JN, Liblau R, Makinen T, Engelhard VH. Roles of lymphatic endothelial cells expressing peripheral tissue antigens in CD4 T-cell tolerance induction. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6771. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scallan JP, Knauer LA, Hou H, Castorena-Gonzalez JA, Davis MJ, Yang Y. Foxo1 deletion promotes the growth of new lymphatic valves. J Clin Invest. 2021;131:e142341. doi: 10.1172/JCI142341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banerjee R, Knauer LA, Yang Y. Protocol for in vivo and in vitro study of lymphatic valve formation driven by shear stress signaling pathway. STAR Protoc. 2023;4:102141. doi: 10.1016/j.xpro.2023.102141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bazigou E, Lyons OT, Smith A, Venn GE, Cope C, Brown NA, Makinen T. Genes regulating lymphangiogenesis control venous valve formation and maintenance in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2984–2992. doi: 10.1172/JCI58050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi I, Chung HK, Ramu S, Lee HN, Kim KE, Lee S, Yoo J, Choi D, Lee YS, Aguilar B, et al. Visualization of lymphatic vessels by Prox1-promoter directed GFP reporter in a bacterial artificial chromosome-based transgenic mouse. Blood. 2011;117:362–365. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-298562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang XZ, Wu JF, Ferrando R, Lee JH, Wang YL, Farese RV, Jr, Sheppard D. Fatal bilateral chylothorax in mice lacking the integrin alpha9beta1. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5208–5215. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.14.5208-5215.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Altiok E, Ecoiffier T, Sessa R, Yuen D, Grimaldo S, Tran C, Li D, Rosner M, Lee N, Uede T, et al. Integrin alpha-9 mediates lymphatic valve formation in corneal lymphangiogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:6313–6319. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saxton RA, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell. 2017;169:361–371. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oliver G, Kipnis J, Randolph GJ, Harvey NL. The lymphatic vasculature in the 21st century: novel functional roles in homeostasis and disease. Cell. 2020;182:270–296. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kemp SS, Aguera KN, Cha B, Davis GE. Defining endothelial cell-derived factors that promote pericyte recruitment and capillary network assembly. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40:2632–2648. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.314948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, Wada R, Yamashita T, Mi Y, Deng CX, Hobson JP, Rosenfeldt HM, Nava VE, Chae SS, Lee MJ, et al. Edg-1, the G protein-coupled receptor for sphingosine-1-phosphate, is essential for vascular maturation. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:951–961. doi: 10.1172/JCI10905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang X, Castilla LH, Xu X, Li C, Gotay J, Weinstein M, Liu PP, Deng CX. Angiogenesis defects and mesenchymal apoptosis in mice lacking SMAD5. Development. 1999;126:1571–1580. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.8.1571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sweet DT, Jimenez JM, Chang J, Hess PR, Mericko-Ishizuka P, Fu J, Xia L, Davies PF, Kahn ML. Lymph flow regulates collecting lymphatic vessel maturation in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:2995–3007. doi: 10.1172/JCI79386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wigle JT, Oliver G. Prox1 function is required for the development of the murine lymphatic system. Cell. 1999;98:769–778. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81511-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]