Abstract

The young adulthood years are demographically dense. Dr. Ronald Rindfuss made this claim when he was Population Association of America (PAA) president in 1991 (Rindfuss 1991), and this conclusion holds today. I offer both an update of his work by including Millennials and a new view on young adulthood by focusing on an increasingly common experience: cohabitation. I believe we need to move away from our marriage-centric lens of young adulthood and embrace the complexity that cohabitation offers. The cohabitation boom is continuing with no evidence of a slowdown. Young adults are experiencing complex relationship biographies, and social science research is struggling to keep pace. Increasingly, there is a decoupling of cohabitation and marriage, suggesting new ways of framing our understanding of relationships in young adulthood. As a field, we can do better to ensure that our theories, methods, and data collections better reflect the new relationship reality faced by young adults.

Keywords: Cohabitation, Cohorts, Marriage, Family, Measurement

Demographically Dense Young Adulthood

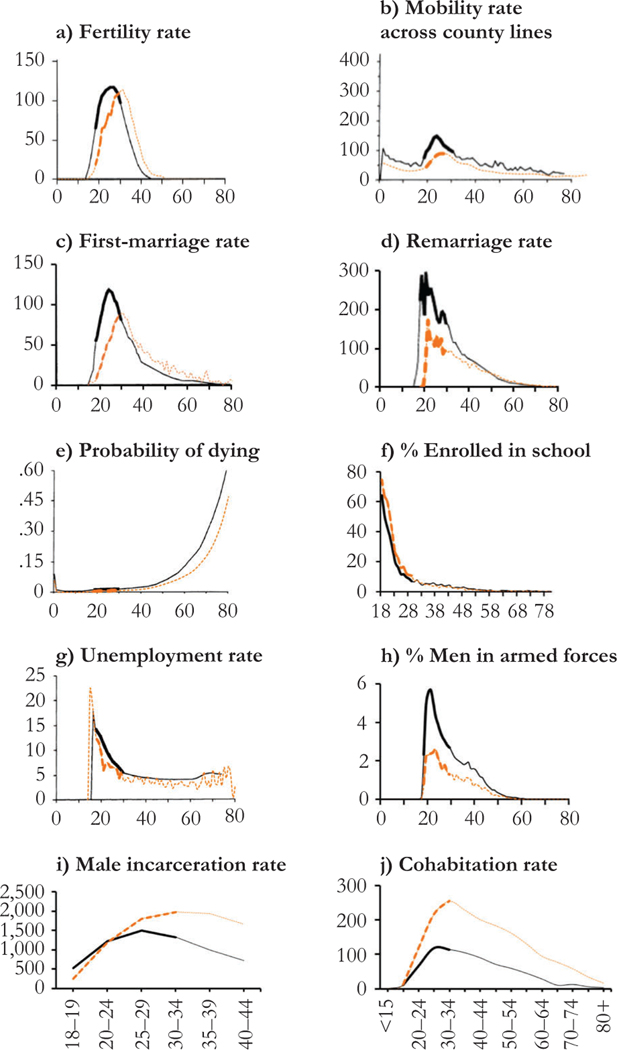

Rindfuss’s PAA presidential address nearly 30 years ago was visually effective (Rindfuss 1991). He included a set of age-specific rates in clear graphs that showed the concentration of events in the young adult years. I build on his portrait by contrasting the young adult Baby Boomers of his address with the Millennials of today.1 As demographers, we are well aware of these birth cohort distinctions. I am not reifying these cohort definitions but instead using them as tools—a set of bookends—to demonstrate change over time for an age group. In the panels of Fig. 1, I replicate the Rindfuss (1991) graphs but include cohabitation, add incarceration and military service for men, and update with a new cohort. The dashed lines represent Millennials in young adulthood, and the solid lines are the Rindfuss Baby Boomers (most of his data reference behavior in the 1980s). The bold areas in the graphs indicate the young adult years. These graphs present general patterns for age groups and two cohorts; there certainly is variation in these experiences across social and economic groups that is not shown here.

Fig. 1.

Age-specific rates and percentages for Baby Boomers and Millennials in young adulthood. The solid line represents the Baby Boomer cohort in young adulthood, and the dashed line represents the Millennial cohort in young adulthood. Sources: Panel a: 1989, National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS); 2016, ACS one-year estimates fertility rates per 1,000 women. Panel b: 1989, U.S. Census Bureau; 2013, U.S. Census Bureau, CPS. Panel c: 1990, NCHS; 2016, ACS one-year estimate first marriage rates per 1,000 never-married women. Panel d: 1990, NCHS; 2016, ACS one-year estimate remarriage rates per 1,000 previously married women. Panel e: 1990, NCHS; 2011, Centers for Disease Control/NCHS National Vital Statistics System. Panel f: IPUMS-CPS, University of Minnesota. Panel g: 1989, March CPS; 2017, IPUMS-CPS, University of Minnesota. Panel h: 1990 Decennial Census 1990; 2016 ACS one-year estimates. Panel i: 1997 Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS); 2016 BJS national prison statistics rates per 100,000 U.S. residents. Panel j: 1995 and 2017, IPUMS-CPS, University of Minnesota currently cohabiting rates per 1,000 not currently living with a spouse.

Cohabitation is a significant demographic event that was excluded from the Rindfuss (1991) depiction of young adulthood. As shown in panel j of Fig. 1, cohabitation peaks in young adulthood, and the rates are much higher for Millennials than for Baby Boomers. Although many of the rates of other demographic events are lower today than in the 1980s, the rates still peak in the young adult years. Specifically, fertility, mobility, marriage, divorce, and remarriage rates are higher in young adulthood than later in the life course. An obvious exception is mortality: death rates are still highest at older ages. In addition, Rindfuss showcased that young adulthood represents the peak years for building human capital, such as school enrollment, as well as employment transitions. Two key American institutions relevant for young adults—the military and incarceration system—were not part of the Rindfuss portrait. Both military service and incarceration rates are highest in the young adult years.2 Taken together, it is just as apparent now as in 1991 that the young adult years continue to be demographically dense. I join many other social scientists who argue that we need to expand how we contextualize young adulthood by including all these events and roles to provide a more comprehensive portrait.

Since the Rindfuss (1991) address, there have been new streams of work on young adulthood, each employing unique perspectives. Frank Furstenberg, sociologist and demographer, formed and led the MacArthur Network on Transitions to Adulthood in 2000. That body of work showcased the prolonged path into adulthood and differential patterning of transitions based on socioeconomic status (Furstenberg 2010; Settersten et al. 2005). Around the same time, developmental psychologist Jeffrey Arnett coined the term “emerging adulthood” and established a journal and national conference on this topic. He argued that these were the in-between years that included exploration of identities, resulting in a “winding path through adulthood” (Arnett 2000, 2004). The more recent work of Jennifer Silva (2012, 2013) has focused on the uncertain futures of young adults of the working class and their concerns, which potentially lead them to avoid relationships. As she stated (Silva 2013:59), “the working class seem trapped between rigidity of the past and flexibility of the present.” Stefanie DeLuca et al. (2016) introduced the term “expedited adulthood,” portraying how some young adults who do not have the luxury of a college degree acquire independence by pursuing the shortest path to adulthood.

Despite healthy debates about young adulthood, there seems to be consensus around the idea that it is increasingly challenging to achieve the traditional markers of adulthood. Although this body of work on young adulthood acknowledges cohabitation, it is most often treated as an indicator of the shifting centrality of marriage and not the central theme of young adult lives. A marker of adulthood for young adults today may indeed be cohabitation because it is increasingly how young adults start their relationships and children are increasingly born and raised in cohabiting-parent families. Because cohabitation has become the most common family experience during young adulthood, beating out parenthood and marriage (Hemez 2018), it merits more attention.

These young adult years are consequential: young adults are often the engines or drivers of social change. As Kingsley Davis implied in his 1963 presidential address, it is the actions of young adults that provide the well-known “multiphasic responses” (Davis 1963). It is not hard to imagine that the decisions and actions of young adults are far-reaching. For example, just take the Baby Boomers of the Rindfuss address, who are now navigating older age. Brown and Lin (2012) showed the ripple effects of Baby Boomers’ early family decisions, such as divorce and repartnering, on the well-being and caregiving of aging Baby Boomers. Questions that merit consideration include the long-term ramifications of Millennials’ early adult decisions on how they navigate their own middle and older years. However, these questions will remain unanswered unless we broaden our relationship scope in all surveys to include full cohabitation histories.

Cohabitation Boom

Until recently, young adult nonmarital romantic relationships were not viewed as particularly formative or important. However, in recognition of the consequences that these relationships can have for individual well-being, behavior, and later union experiences, we have begun to acknowledge their developmental significance (e.g., Fincham and Cui 2010; Giordano et al. 2012). Rather than imposing a marriage blueprint on these nonmarital relationships, we need to study them in their own right and assess their meaning for this new generation of young adults.

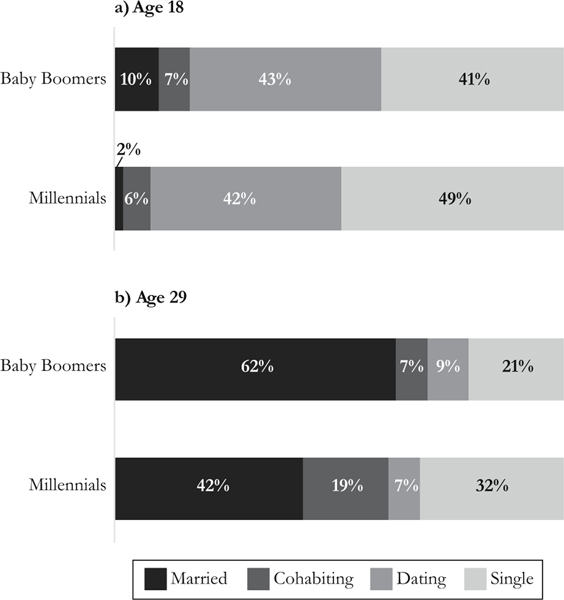

Figure 2 presents a snapshot of relationships for U.S. Baby Boomer and Millennial cohorts using data based on the National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH) and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 (NLSY97). At the beginning of adulthood, age 18 (panel a), the relationship circumstances of Baby Boomers and Millennials are not so different across cohorts. However, at the end of early adulthood, age 29 (panel b), clear cohort differences emerge. There has been a large shift away from marriage, a nearly threefold increase in cohabitation, a remaining substantial share who are in relationships, and many who are single (32%).

Fig. 2.

Young adult relationship statuses at ages 18 and 29. Sources: NSFH 1987/1988 and NLSY-97.

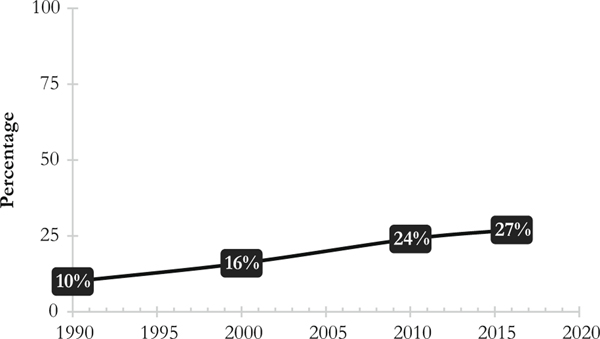

The increase in cohabitation in young adulthood is not limited to the United States. Cohabitation is advancing worldwide, as we have learned through excellent research across the globe (e.g., Esteve et al. 2016; Perelli-Harris and Lyons-Amos 2015; Raymo et al. 2015). Esteve and colleagues have called this growth in cohabitation a “cohabitation boom,” referring to the increase in cohabitation across North and South America (from Canada to Chile).3 The indicator they used is the share of women cohabiting (or living in consensual unions) among women aged 25–29 residing in a union. In 1970, there were 25 regions where at least one-half of women in unions were cohabiting; today, the overwhelming majority, outside the United States, have reached these high levels. Although the U.S. boom is not as high as the rest of North and South America, it has moved forward at a rapid pace. Building on work by Lesthaeghe et al. (2016), Fig. 3 shows that the level in the United States has nearly tripled over about a 25-year time span, from 10% at the time of the Rindfuss (1991) PAA presidential address to 27% in 2016. Although cohabitation has sometimes been characterized as a family experience for those who are the least well off, the rise has been fairly even across socioeconomic groups, with no current differences in this measure in the United States according to education level. Like many other nations, cohabitation is not just experienced by the disadvantaged, but there appears to be a convergence: it crosscuts all social classes. This measure allows important comparisons but is limited because it represents only a snapshot, and the basis of the indicator is women who have formed a coresidential union.

Fig. 3.

Percentage cohabiting among women aged 25–29 coresiding in a union. Sources: 1990 and 2000 decennial censuses, Lesthaeghe et al. (2016), and 2010 and 2016 ACS one-year estimates.

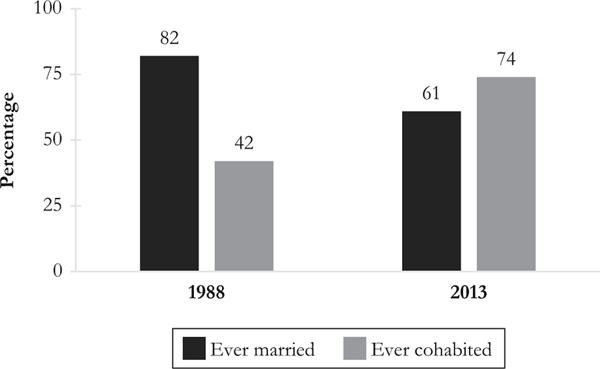

Another way to encapsulate and compare experiences is by focusing on whether young adults ever experienced cohabitation. Baby Boomers and Millennials are similar in that almost all have had sex, dated, and formed a coresidential union during young adulthood. Among coresidential relationship types, cohabitation has surpassed marriage as the most common family experience in young adulthood. Based on the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), Fig. 4 indicates that cohabitation for young adult Baby Boomer women was a minority experience: 42% ever cohabited by their late 20s. Comparatively, cohabitation has become a majority experience for Millennials, with nearly three-quarters experiencing cohabitation by the end of young adulthood (see also Hemez 2018).4

Fig. 4.

Percentage of young adult women aged 29–31 who ever married and ever cohabited. Sources: 1988 NSFG and 2011–2015 NSFG.

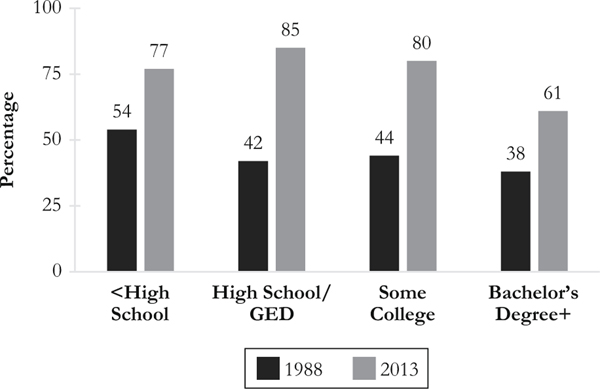

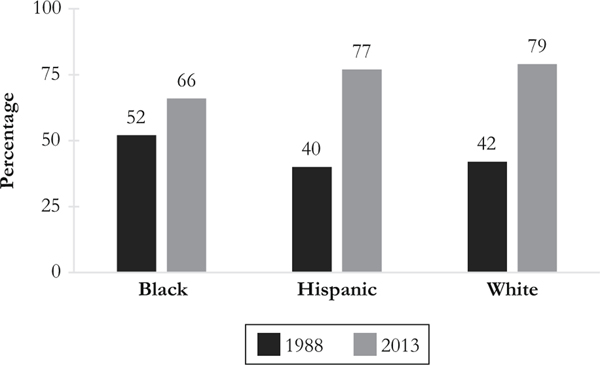

The education gradient in experiencing cohabitation in young adulthood is widening. Among Millennial women in 2013, the majority of every education group cohabited by age 30, ranging from 85% among high school graduates to 61% among college graduates (Fig. 5). Among Baby Boomers, just over one-half (54%) of women without a high school diploma cohabited by age 30 in contrast to about 4 in 10 of every other education group. The racial/ethnic differences are less marked across cohorts, with most of the growth occurring among Whites and Hispanics. Among Millennials, two-thirds (66%) of Black, 77% of Hispanic, and 79% of White women reported having ever cohabited in young adulthood (by age 30) (see Fig. 6). Even though there is growth in cohabitation across socioeconomic groups, it certainly does not mean that cohabitation carries the same meaning for all (Sassler and Miller 2017).

Fig. 5.

Percentage of young adult women aged 29–31 who ever cohabited, by education level. Sources: 1988 NSFG and 2011–2015 NSFG.

Fig. 6.

Percentage of young adult women aged 29–31 who ever cohabited, by race/ethnicity. Sources: 1988 NSFG and 2011–2015 NSFG.

Ready, Willing, and Able

In the United States, the social context has shifted and spawned the rise in cohabitation. One way the cohabitation boom has been explained is through the use of Ansley Coale’s “ready, willing, and able” (RWA) framework (Esteve et al. 2016). Coale was PAA President 50 years ago and developed this framework to explain marital fertility transitions in Europe. Drawing on Esteve’s research and Coale’s (1973) framework, I outline how Americans are ready, willing, and able to further support the cohabitation boom. A premise of the RWA framework is that all conditions have to be jointly met to create any behavior change. Another asset of this perspective is that it highlights the importance of demographic, economic, social, and cultural factors.

Ready

Ready suggests that young adults view advantages to cohabitation. As Valerie Oppenheimer (2003:131) summarized in her work on Baby Boomers, “cohabiting may now partly represent an adaptive strategy for those whose life is still somewhat on hold in other ways.” This statement applies today: cohabitation is a relationship that permits flexibility and avoids long-term commitments. In fact, this might be a smart or savvy strategy for young couples to do relationships.

Young adults want to be financially secure before they get married, and marriage is a signal of economic independence (Smock et al. 2005). Based on analysis of the NSFG (1987/1988) and the Families and Relationships Study (FRS) (2010), both Baby Boomer and Millennial unmarried young adults reported that it is important to have enough money (61% of Baby Boomers vs. 57% of Millennials) as well as be and finish schooling before marriage. To put it another way, young adults cannot get married, but they may be able to cohabit if they have not achieved financial independence and are relying on parents or loans for car payments, rent, insurance, or cellphone service. Mills and Blossfeld (2005) showed that in Europe, globalization generated more uncertain labor markets and thereby created opportunities for more flexible relationships, such as cohabitation. Oppenheimer and Kalmijn (1995) argued 25 years ago that the reliance on stop-gap jobs—in today’s terms, a gig economy—sets the stage for cohabitation both in terms of social and economic factors.

Cohabitation has emerged against a backdrop in which the economic circumstances of Millennials are not bright. Young adults today fare worse than their Baby Boomer counterparts at the same age. For example, men have higher unemployment rates and have been slow to move into the gold standard of adulthood: a full-time job with benefits (Sum and Khatiwada 2010). About three in five Millennials have student debt, and their level of student debt is higher than prior generations, which represents an important barrier to moving up the economic ladder (Arnett 2015; Kantrowitz 2015). Even though there has been an expansion in college education, it is not an option for all, largely because of affordability concerns. Homeownership rates are lower among Millennials than Baby Boomers, and housing costs are higher in general for both purchasing or renting (Fry 2013). As a result, Millennials are not acquiring wealth at the same pace as did Baby Boomers. With regard to intergenerational processes, Chetty and colleagues (2017) argued that Millennials are unique in that they have only a 50–50 shot of doing as well as their parents. The majority of young adults (70%) state that they will go back for more education and training in their 30s or 40s, and they expect to change career paths, with two of three reporting that their current job is not in the field in which they hope to work in 10 years (Arnett 2015). The Great Recession casts a long shadow, and the new reality for young adults is an uncertain economic future. These unsettled economic circumstances have had implications for relationship trajectories of young adults.

Beyond affecting jobs, these uncertain futures may mean that Millennials are not yet reaching a more settled lifestyle that would align with marriage, such as moving away from substance use and delinquent behaviors (Copp et al. 2019). Young adults view cohabitation as a way to figure out whether they are compatible and reference relatively mundane albeit important issues: it is a way to determine whether their partner will pick up their socks (Smock et al. 2005). Cohabitation can serve a practical need to share housing or save money (e.g., two can live more cheaply than one) or a way to take their relationship to the next level and make some form of a commitment. Even though cohabitation appears to have several advantages, it seems young adults do not want to lock into a long-term relationship (such as marriage) until they feel they are ready.

A sense of whether as a society we are ready for cohabitation is reflected in the behavior of both older and young adults. The older generation is cohabiting at historically high levels: about one in seven unmarried men and women over age 50 are cohabiting (Brown and Wright 2016). Older Americans tend to cohabit to avoid legal entanglements, which serves as a way to protect financial assets (Brown et al. 2012). Although most young adults have not built financial assets or possess inheritances, older adults may feel the need to protect pensions or Social Security benefits and may also view cohabitation as a way to avoid legal entanglements (such as divorce) (Manning and Smock 2009; Miller et al. 2011). Cohabitation seems to offer an easier way out of a relationship that is not working; on this front, marriage seems risky for the young. Many of the legal benefits of marriage are not as salient for young adults until they are close to the end of life, or these benefits may appear during moments of crisis, such as death or a sudden health trauma. In fact, several research teams using longitudinal data (e.g., Amato 2014; Musick and Bumpass 2012) have shown that cohabitors accrue many of the same psychological and health benefits as their married counterparts.

There are not just financial issues at stake but caretaking responsibilities. An unsettled feature of cohabitation for older adults is potentially intense caretaking that will certainly arise in old age. It is not clear whether cohabiting partners are obligated to stick around during times of intense need (Noel-Miller 2011). In contrast, the primary caretaking responsibility in young adulthood is parenting. Young adults who cohabit with children feel that they are making a commitment to their children by living together and co-parenting, and they see themselves as a family (Manning et al. 2009). Powell et al. (2010) found that in the United States, there is strong consensus that cohabiting parents with children are viewed as a family. Taken together, older Americans along with young adults may be providing a strong case for cohabitation and indicate a readiness for even higher levels.

Willing

Willing indicates that there is some legitimacy of cohabitation and/or willingness to overcome potential moral objections. The social norms supporting cohabitation have rapidly increased. In terms of religion, young adults today are certainly less religious than their counterparts in prior generations (Pew Research Center 2018), so the barriers to cohabitation on moral ground may not be as high. Also, many religions now embrace all couples and families regardless of marital status.

All generations are reporting growing approval of cohabitation. High school seniors’ acceptance of cohabitation as “a testing ground for marriage” moved from less than one-half in the 1970s to approaching three-quarters today (Allred 2019a). Among young adults in the General Social Survey, supportive attitudes toward cohabitation increased from 50% in 1994 to nearly three-quarters in 2012. Brown and Wright (2016) showed a change in support among older Americans, increasing from 31% in 1994 to more than one-half in 2012 among 50- to 59-year-olds. Thus, growth in support for cohabitation has not been limited to the young and suggests that complex processes may be driving change. Indeed, Larry Bumpass (1990) argued in his 1990 PAA presidential address that there are important feedback mechanisms across generations, with shifting attitudes supporting cohabitation and growth in cohabitation experience. Despite pockets of Americans who oppose cohabitation, levels of willingness to cohabit generally appear to be high.

Able

The third part of the RWA framework is able. Young adults’ ability to cohabit is determined in part by the costs of housing to live together as well as legal issues. The norm for cohabitation and marriage is to live independently. Based on analysis of the Current Population Survey (CPS), today most young adult cohabitors live on their own (72%), but some live with their parents (8%) or other adults (20%) (Payne 2019). Growing housing costs make it difficult for couples to launch on their own. Thus, housing is certainly a constraint but can be overcome by living with others.

In terms of legal matters, cohabiting without the benefit of marriage was once illegal, and such laws are still on the books in a few states albeit not enforced. The legal protections offered for cohabitation in the United States are minimal. Comparatively, Canada has legal processes for splitting assets for couples ending cohabiting unions (Laplante and Fostik 2016). Such a process does not exist in the United States, which experienced an expansion of legal recognition of domestic partnerships at different levels of government and among some employers, based largely on an effort to support same-gender couples who could not legally marry. These partnerships offered many benefits on par with marriage to same-gender and different-gender cohabiting couples. Yet, some domestic partnership policies have been retracted because marriage is available to all. In addition, government policies and programs regarding support for cohabiting couples are uneven and inconsistent: some policies base benefits, such as SNAP, on the consuming unit (including cohabitors), and others ignore cohabiting partners altogether. The United States differs from many other countries in the lack of legal recognition and treatment of cohabitation in the policy realm.

The ability to cohabit has grown with delays in marriage. Lower shares of Millennials have married in young adulthood than have Baby Boomers. In 1990, most (62%) marriages occurred among young adults, compared with only (42%) today. The age at marriage is postponed, and the nation as a whole has reached a historic highpoint of the median age at first marriage: 29.8 for men and 28.0 for women (U.S. Census Bureau 2019). Baby Boomers experienced marriage during the midpoint of their young adult years (median ages of 26.1 for men and 23.9 for women in 1990), whereas Millennials experienced marriage at the end of young adulthood, leaving more space in the life course for cohabitation during young adulthood.

It seems that all the elements are in place for the cohabitation boom to continue in the United States, which despite some constraints has probably not reached its maximum cohabitation levels. It seems that for young adults, cohabitation may be an adaptive strategy to the shifting economic reality, the delay or drift away from marriage, and changes in social norms fueled in part by intergenerational support. The experience in the United States is quite distinct from that of other countries.

Decoupling of Marriage and Cohabitation in Young Adulthood

Although the growth in cohabitation is clear, it remains uncertain what this means for the future of marriage. Our field is often confronted with the question of whether marriage is obsolete for young adults today. However, this specific question about the retreat from marriage has been on the minds of demographers for more than 35 years, dating back to when marriage rates were much higher, marriages started at younger ages, and divorce rates were higher (Davis 1983). Americans are unique in their enthusiasm for marriage: if the first marriage does not work out, they often marry again. Cherlin (2009) termed this American experience the “marriage-go-round.”

Many in our society (as well as the wedding industry complex) breathe a collective sigh of relief when they learn that teenagers and young adults still want to get married. The Monitoring the Future survey data for 1976–2017 indicate that a steady and high share of high school seniors expect to marry over time (Allred 2019b). These levels have remained high for Baby Boomers and Millennials, with about three-quarters expecting to marry (Allred 2019b). Similarly, the prominence of marriage over cohabitation is supported, with young adult single women expressing greater expectations to marry than cohabit (Manning et al. 2019b). Further, expectations to marry remain high across education and racial/ethnic groups (Manning et al. 2019b). Given actual differences in patterns of marriage showing lower levels of marriage among the more disadvantaged and African Americans, marriage expectations have been classified as only “hopes” (Waller 2001). These hopes appear to persist through young adulthood even when their relationships are tested by the harsh realities of everyday life. A clear gap remains between our marriage idealism and reality.

The value of marriage became quite apparent during the recent battle for marriage equality, which brought to the forefront the worth of the powerful institution of marriage. In the United States, marriage ensures many benefits related to multiple domains of life, including immigration, health care, inheritance, taxes, social security, adoption, and parenthood. Based on Gallup data, support for marriages to same-gender couples shifted from only 27% in 1990 to 67% in 2018 (McCarthy 2018). Despite the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in 2016 to support marriage for all, in 2018 there were still counties in the United States where marriage for gay men and lesbian women was denied, including in Alabama, Oklahoma, Indiana, Kentucky, Montana, and Missouri.

The marriage rates of young adult gay men and lesbian women have been slow to catch up with those of different-sex couples (Jones 2016). These Gallup Poll data indicate that older gay men and lesbian women, most often in longer-term relationships, have experienced greater increases in marriage levels than their younger counterparts—a trend that may shift as the marriage equality becomes more firmly established. These young gay men and lesbian women did not grow up with marriage as a relationship option and may eventually experience marriage levels on par with different-gender young adults as they move into parenting roles. This does not mean that gay men and lesbian women are avoiding relationships: the age at union formation for LGB young adults is roughly on par with that for different-gender couples (Prince et al. 2020). In a new climate of growing acceptance and support of sexual minorities and improved legal protections, young adult sexual minorities will most likely cohabit at levels similar to those of their sexual majority counterparts.

Growing shares of Millennials will not reach the traditional adulthood marker of marriage until their 30s, and many may never marry. Analysis of American Community Survey (ACS) data indicates that by age 40, about 90% of Baby Boomers had married, and this level declined among Gen Xers (birth cohort 1965–1979) to only 80% of women and 75% of men. Martin et al. (2014) projected that if the post–Great Recession marriage rates continued, only 69% of Millennial women and 65% of Millennial men will marry by age 40. Despite delays in marriage across the board, a growing share of Blacks, Hispanics, and adults without a college degree are projected to never marry (Martin et al. 2014). Thus, new opportunities for cohabitation may arise during some of the never-married years not only in young adulthood but also during middle age and older ages.

Young adult Millennials who do marry are marrying in different ways than their Baby Boomer counterparts; today, very few marriages occur without the benefit of cohabitation. In other words, there are few direct marriages—marriages to couples who did not live together before they walked down the aisle. Evidence from analyses of the 1985 and 2011– 2015 NSFG data indicates that among those who got married, most Baby Boomers did not cohabit before they got married, but the majority (70%) of Millennials have done so. Further, a growing share of all women have lived with someone besides their husband before marriage. In the early 1980s, about 13% of women who cohabited prior to marriage lived with someone else, compared with one-third in 2013.

Even though most Millennials are not marrying in young adulthood, they are not giving up on all relationships. Today, nearly all single young adults have had sexual relationships, and most have lived with a cohabiting partner (Hemez et al. 2018). Millennials have had more sexual relationships than Baby Boomers. The definition of the exact context of sexual relationships is not always clear, given that some are short- or long term, others are romantic or dating with boyfriends or girlfriends or cohabiting partners, and others are casual sexual relationships often with friends (i.e., “friends with benefits,” “hooking up,” or someone they were talking to).

Millennials continue to enter coresidential relationships, and there has been nearly no change in the age at which they enter unions. Millennials are forming their relationships at the same age as Baby Boomers did, at around age 22 or 23 (Manning et al. 2014). The mean age of cohabitation is consistently about 22, while the age at marriage has continued to rise. Today, for four of five (81%) women, the first coresidential relationship is cohabitation and not marriage. Although the vast majority of Baby Boomers (89%) and Millennials (90%) had married or cohabited in young adulthood, the first person Millennials live with is now a cohabiting partner, whereas for Baby Boomers, it was a husband or wife. Cohabitation has accounted for virtually all the decline in marriage in young adulthood. These findings are consistent with the cohabitation boom described earlier. Although there is a retreat from marriage in young adulthood, there does not appear to be an equivalent retreat from living together.

Evidence of the decoupling of cohabitation and marriage is that cohabiting unions are no longer only a pathway to marriage. Bumpass et al. (1991) reported in the late 1980s that about three-quarters of cohabitors expected to marry their partner, but this percentage declined substantially about 20 years later, with a minority (approximately 40%) expecting to marry (Guzzo 2014; Vespa 2014). The marital expectations today do not vary by social class: the college-educated and more modestly educated cohabitors share similar expectations to marry (Kuo and Raley 2016). Further, fewer cohabitors are transitioning into marriage (Guzzo 2014; Lamidi et al. 2019). Lamidi et al. (2019) showed that for the Baby Boomer cohabitation cohort, marriage was the most common outcome, and today it is the least common pathway out of cohabitation. Among more recent cohabitation cohorts, the way out of cohabiting unions is more often a breakup than marriage. The college-educated have not experienced this same decline, and they are the group that still more often marry; notably, though, only 40% did so by the third year of cohabitation (Lamidi et al. 2019). Taken together, declining shares of cohabiting couples report expecting to marry, fewer actually marry, and those who marry seem to be in no big hurry to do so.

Cohabitation and Relationship Instability

How does cohabitation influence marital stability among the minority of cohabiting couples that marry? One argument against cohabitation for Baby Boomers was that it was associated with lower levels of subsequent marital stability (Smock 2000). However, most evidence suggests that this is no longer the case: cohabitation does not seem to hurt or help. If marriage is the way out of a cohabiting union, it no longer appears to be linked to lower levels of marital stability (Kuperberg 2014; Manning and Cohen 2012; Manning et al. forthcoming; Reinhold 2010). Even among couples with children, Musick and Michelmore (2018) showed that those cohabiting at birth who subsequently marry are no more likely to end their marriages than parents who married without cohabitation. In the future, it is possible that as cohabitation becomes more widespread, brides and grooms who do not cohabit are increasingly select (traditional couples with strong religious convictions). As a result, lower levels of marital instability may be observed among those who do not cohabit. Further, researchers have called for better assessments of how and when different types of relationships are associated with relationship stability (Kuperberg 2014; Rosenfeld and Roesler 2019; Sassler et al. 2018).

Although cohabitation is common, it typically does not last long and is consistently shorter in duration than marriages. This is why simple snapshots of cross-sectional data on cohabitation provide a biased portrait. Analysis of the 2011–2015 NSFG data indicates that about one-half of young adult first cohabiting relationships last just over two years—a duration that is eight months or at least 50% longer than cohabitations in the late 1970s and early 1980s (median duration = 1.3) across all ages in the NSFH (Bumpass and Sweet 1989). It appears that longer-term cohabitations may be on the rise.

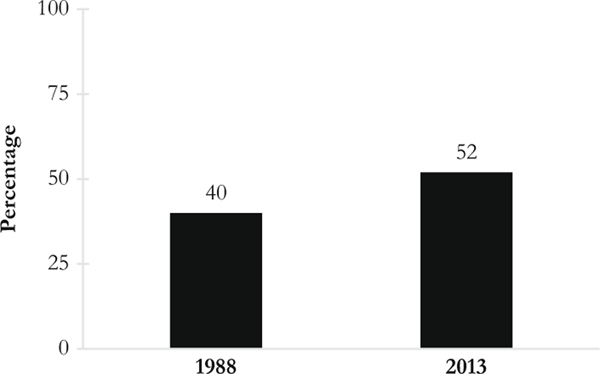

About one-half of Millennial young adults who have been in a coresidential relationship will experience the dissolution of at least one relationship, compared with only 40% of Baby Boomers (Fig. 7). This finding is not surprising given the declining divorce rates among young adults (Allred 2019c), but the growth in cohabitation means that the likelihood of experiencing the dissolution of a coresidential union has increased. Kennedy and Ruggles (2014:596) stated that “the rapid rise of cohabitation among the young will neutralize any decline of divorce.” In fact, this is supported by empirical evidence showing that young adults’ higher rates of union dissolution are due to cohabitation (Eickmeyer 2019). The majority of union dissolutions among Millennials are cohabiting dissolutions, but the majority among Baby Boomers were marital dissolutions. Analyses of the 2011–2015 NSFG indicate that the rates of coresidential dissolution in young adulthood are highest for women with a high school diploma (70%) and much lower for the college-educated (28%). Among those in coresidential relationships, 70% of Black women, 50% of White women, and 44% of Hispanic women experienced dissolution. Not only are young adults more likely to experience a relationship ending, but they experience multiple endings. Nearly 1 in 10 Millennials who were in a coresidential relationship (marriage or cohabitation) experienced two or more breakups (Eickmeyer and Manning 2018). The implications of these breakups are likely important in terms of economic well-being, emotional health, subsequent family formation, and responsibilities for children. These questions about the implications of relationship instability—not just divorces—need to be fully explored in the new relationship context.

Fig. 7.

Percentage of young adult women aged 29–31 who experienced union dissolution among women ever in a coresidential union. Sources: 1988 NSFG and 2011–2015 NSFG.

Breakups are not always final because a substantial share of cohabiting couples break up and get back together. Churning, or cyclical cohabitation, is fairly common in young adulthood. Halpern-Meekin et al. (2013) reported that two in five cohabiting young adults reported churning. On one hand, this indicates some optimism and desire for couples to stay together as they work through issues. These types of churning make it complicated to study relationship endings and are associated with a potentially troubled relationship. Notably, a parallel issue exists when studying marriage. Divorce is a legal status, but there are varying lengths of time spent in a separated status. Tumin et al. (2015) found that 11% of separated individuals reconcile within five years, and 22% remain separated without a legal divorce five years after separation. Just as it is hard to capture relationship beginnings (Manning and Smock 2005), it is challenging to measure the end of a relationship even when studying marriage.

If Millennials break up, they often try again to live with someone new. Three-quarters of cohabiting breakups result in a new cohabiting relationship (Eickmeyer and Manning 2018). Millennials more often go on to form a second cohabiting relationship than did Baby Boomers (Eickmeyer and Manning 2018). Millennials also form a second cohabiting partnership faster than their older counterparts (on average, two years rather than four years). This means that Millennials have more often experienced a series of relationships by the time they reach their 30th birthday than their Baby Boomer counterparts.

These increasingly complex relationship biographies may have both positive and negative implications. A positive spin is that Millennials have more relationship experience and may become better at doing relationships as they learn critical skills about what works and what does not work as well as how to best navigate the starting and ending of partnerships. In essence, there is a relationship learning curve (Giordano et al. 2012), and Millennials may be gaining relationship competencies that are carrying forward to contribute to positive relationship habits and functioning. A negative spin is that young adults are bringing forward potentially poor relational practices and behaviors from prior relationships, which present challenges as they move into new partnerships. Further, children from prior relationships may present challenges as couples have to work out relationships with ex-partners in efforts to co-parent. Both positive and negative processes are likely to be operating, and both warrant research attention.

Cohabitation and Intergenerational Ties

In young adulthood, intergenerational ties are significant because there are two sets of key processes operating: moving out of parental homes and becoming parents themselves. As Bumpass (1990) and Smock (2000) argued, there are feedback loops as new generations of youth as well as parents are socialized in contexts with increasing levels of cohabitation.

The process of moving out has blurred: increasing shares of young adults are living with their parents, and more are boomeranging back to their parent’s home (Payne 2011). In terms of cohabitation, it is not very common for cohabiting couples to live with parents. According to the CPS, only 9% of young cohabitors (aged 18–24) in 2018 were living with their parents, and a slightly greater share (14%) of married young adults were living with their parents (Payne 2019). It is relatively rare for young adult cohabiting couples to live with their parents, but we may observe growth in the future if it becomes more challenging for couples to live on their own.

As described earlier, older and younger cohorts of Americans are increasingly accepting of cohabitation. The process of attitudes supporting cohabitation occurs within families with parents reporting more positive views toward cohabitation in response to their adult children’s cohabitation. This was evident among Baby Boomer cohorts (Axinn and Thornton 1993) and has been confirmed in my ongoing research with a cohort of Millennials in the 2011/2012 Toledo Adolescent Relationships Study. Intergenerational processes in cohabiting behavior are also empirically supported. Children who spent time with cohabiting parents experience greater odds of cohabiting in young adulthood (Sassler et al. 2009; Smock et al. 2013). Further, McClain (2011) showed that parents have even followed in their children’s footsteps, with greater odds of parental cohabitation among those who have adult children who have cohabited. Thus, the diffusion of cohabitation flows across generations in multiple ways. These patterns suggest a great potential for future high levels of cohabitation.

Cohabitation is increasingly a family form in which to have and raise children. In terms of attitudes, nearly three-quarters of young adults report that it is acceptable to have children in a cohabiting union (Stykes 2015), a view that is consistent across education and racial/ethnic groups. The growth in nonmarital childbearing has been driven largely by increases in cohabitation (Manning et al. 2015). As of 2013, 60% of nonmarital births are to cohabiting mothers. In fact, the share of children born into two-parent families has not changed, remaining stable at about 82% to 85% (Manning et al. 2015). Further, pregnant single women are more likely to cohabit (18%) than to get married (5%) before the birth of their child (Lichter et al. 2014). There is little pressure to marry in response to becoming pregnant while cohabiting. For example, Lichter et al. (2014) reported that nearly four in five women who were pregnant while cohabiting were still cohabiting at the time of birth. Taken together, these findings clearly indicate the growing acceptability of cohabitation as a family context in which to raise children.

In terms of overall child experience in cohabitation, increasing shares of children have spent some of their life with a cohabiting parent. In 1995, 28% of children had experienced parental cohabitation, compared with 40% about 20 years later (Brown et al. 2016). About one-half of children to mothers without a college degree lived in a cohabiting parent family, and nearly one in five (16%) children who had a college-educated mother did so in 2013. Many of these cohabiting families are stepfamilies, and children often live with their mother and her cohabiting partner (Manning 2015). Our field needs to continue to ask important questions about the well-being of children raised in cohabiting-parent families while accounting for biological relationships of children and parents, age at family formation and dissolution, and family complexity.

Measuring Cohabitation

Demographers’ knowledge base about young adult relationships is dependent on accurate measurement. Many have made arguments for new and improved data on cohabitation, and most major surveys include measures of cohabitation. There is wide variation in how we ask about cohabitation. The good news is that we are collecting new data on cohabitation, as evidenced by the new relationship options in the 2020 census. Same-gender and different-gender relationships can now be established with direct questions. On the census, cohabitation has been upgraded from the second to the bottom of the roster of relationship options (just above roomers and boarders) to second from the top on the roster for different-gender couples and fourth for same-gender couples. The bad news is that social media outlets, such as Facebook, do not include cohabitation as a relationship category. Facebook includes the terms domestic partnership and civil union, but I doubt that those terms resonate with very many cohabiting Millennials.

In our field, we consistently ask about marital status and marital history, but we are inconsistent in asking about cohabitation status and cohabitation history. My colleagues and I (Manning et al. 2019a) compared how cohabitation was measured across a number of national data sets for young adults of a similar age and cohort. We discovered wide-ranging measurement techniques, resulting in significant differences in levels of cohabitation. Cohabitation estimates based on household roster techniques (employed in the CPS, ACS, and Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP)) with the term unmarried partner result in substantially lower estimates of cohabitation than do direct questions about cohabitation (NSFG, NLSY97, National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health)). Further, some key data collections (SIPP, Add Health Wave 5, Health and Retirement Survey) exclude full cohabitation histories, so it is impossible to locate cohabitation experiences in the life course and detect the long-range implications of cohabitation on health and well-being at older ages. The wording of questions about cohabitation differs across surveys and does result in differing estimates of cohabitation (Manning et al. 2019a). Some large-scale surveys, such as the NLSY97, Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey, Birth Cohort, and Panel Study of Income Dynamics, still rely on a dated approach by asking about “marriage-like” relationships. Finally, some surveys, such as the NSFG, limit their questions to “opposite-sex” cohabiting couples, thereby eliminating same-gender cohabiting couples. I hope we can come up with greater consensus and consistency in our measurement of cohabitation. These constraints mean that we cannot assess the implications of cohabitation using some of our most prized and valued data.

These measurement constraints are consequential as we attempt to understand the implications of cohabitation for children’s lives. As stated earlier, cohabitation is a family context that is experienced by growing shares of children. However, data requirements to determine whether children are born and raised by biological parents outside of marriage are high. As Guzzo and colleagues (Guzzo and Dorius 2016; Stykes and Guzzo 2019) have effectively argued in their work on multiple-partner fertility, we often focus on the start and end dates of relationships and do not incorporate the biological relationships of children and parents. Rather than linking children based on dates alone, it is critical to ask about children’s biological parents so that we track whether mothers marry the fathers of their children or cohabit with the fathers of the children. In most data sets, it is challenging to trace whether children born outside of relationships are born to the same father. For example, we use dates to establish whether a pregnant mother moves in with the presumed father of her child before the birth of the child. If our goal is to study family stability, it is imperative to know who is in the family. One idea is to even follow the lead of many other countries by including on birth certificates the cohabitation status of parents, and not just marital status.

Discussion

Young adulthood remains demographically dense, and we need to work hard to capture these experiences and acknowledge the diversity of experience and the many ways to move through young adulthood. The challenge is that we continue to study relationships as if we are in a Baby Boomer reality. Marriage is no longer the only or primary relationship context in young adulthood. Taken together, my rationale for sharing these findings here is to make a case for cohabitation. We have spent most of our energy focusing on how it compares with marriage, but as Casper and Sayer (2000) reported, cohabitation can be conceptualized in many ways. It made sense at the time, but the marriage blueprint has limitations in our current era of uncertainty. It might be alright to not know where the relationship is headed for those facing uncertainty on multiple fronts. The United States is part of a worldwide cohabitation boom, but may never become a worldwide leader in cohabitation given the legal benefits of marriage.

Cohabitation experiences are not similar across all social and economic groups, with quite uneven levels of cohabitation experience. There is some convergence in cohabitation demonstrated by an increase for all groups, but the most rapid growth occurs among the modestly educated. Thus, a simple explanation of disadvantage may no longer apply, given that the highest levels of cohabitation in young adulthood are experienced by young adults with high school diplomas and among Whites. Certainly, the college-educated cohabit at the lowest levels, but the most advantaged are increasingly cohabiting.

It is important to know when people live together and when they live part. American society supports a legal status—marriage—that measures the beginnings (wedding) and endings (divorce). Yet in reality, some relationship statuses do not map neatly on the legal definitions. Most young adults start coresidential relationships outside of marriage and end relationships outside of marriage, clearly indicating that most young adults want to be in an intimate coresidential relationship and that most often start out cohabiting. There is more than one way to be living together in the United States. They all deserve to be studied and measured.

As I stated at the outset of this article, an issue for future research to consider is the long-term ramifications of young adults’ decisions in terms of how they will navigate their middle and older years. I suspect that cohabitation will play a pivotal role and may have broad demographic implications. We will not know the answer to such questions unless we extend our relationship scope in all surveys to include cohabitation histories.

Acknowledgments

The Population Association of America has provided an outstanding and welcoming intellectual home base over my career. I gratefully acknowledge my excellent colleagues at Bowling Green State University as well as my coauthors over the years for their amazing support. This work would not have been possible without all their insights and our interactions. My work on this address benefitted from the Center for Family and Demographic Research at Bowling Green State University, which has core funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2CHD0050959). Krista Payne was instrumental in the development of the figures and provided a great sounding board. I appreciate the excellent research and support provided by Kasey Eickmeyer and Paul Hemez.

Footnotes

Of the varying definitions of cohorts, I select the following for this article. Baby Boomers are individuals born between 1946 and 1964 and were age 30 between 1976 and 1994. Millennials are individuals born between 1980 and 1994, reaching age 30 between 2010 and 2024.

The figure represents time spent in prison and not in jail.

The term “cohabitation boom” might imply that there will be an explosive growth followed by a retreat akin to a baby boom. I use the term to focus on growth, and I am not suggesting that it is a temporary phenomenon.

The NSFG supplied weights produce estimates weighted to the midpoint of the data collection years. The midpoint between 2011 and 2015 is 2013. Thus, the weighted estimates reflect the share of women with those experiences in 2013.

References

- Allred C. (2019a). High school seniors’ attitudes toward cohabitation as a testing ground for marriage, 2017 (Family Profile No. FP-19–10). Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research, Bowling Green State University. 10.25035/ncfmr/fp-19-10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allred C. (2019b). High school seniors’ expectations to marry, 2017 (Family Profile No. FP-19–11). Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research, Bowling Green State University. 10.25035/ncfmr/fp-19-11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allred C. (2019c). Age variation in the divorce rate, 1990 & 2017 (Family Profile FP-19–13). Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research, Bowling Green State University. 10.25035/ncfmr/fp-19-13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amato P. (2014). Marriage, cohabitation and mental health. Family Matters, 96, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2015). Clark University poll of emerging adults: Work, education and identity. Worcester, MA: Clark University. [Google Scholar]

- Axinn WG, & Thornton A. (1993). Mothers, children, and cohabitation: The intergenerational effects of attitudes and behavior. American Sociological Review, 58, 233–246. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Bulanda JR, & Lee GR (2012). Transitions into and out of cohabitation in later life. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 774–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, & Lin I-F (2012). The gray divorce revolution: Rising divorce among middle-aged and older adults, 1990–2010. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 67, 731–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Stykes JB, & Manning WD (2016). Trends in children’s family instability, 1995–2010. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78, 1173–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, & Wright MR (2016). Older adults’ attitudes toward cohabitation: Two decades of change. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 71, 755–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass LL (1990). What’s happening to the family? Interactions between demographic and institutional change. Demography, 27, 483–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass LL, & Sweet JA (1989). National estimates of cohabitation. Demography, 26, 615–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass LL, Sweet JA, & Cherlin A. (1991). The role of cohabitation in declining rates of marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53, 913–927. [Google Scholar]

- Casper LM, & Sayer LC (2000, March). Cohabitation transitions: Different attitudes and purposes, different paths. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin A. (2009). The marriage-go-round: The state of marriage and family in America today. New York, NY: Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty R, Grusky D, Hell M, Henderson N, Manduca R, & Narang J. (2017). The fading American dream: Trends in absolute income mobility since 1940. Science, 356, 398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coale AJ (1973). The demographic transition revisited. In Proceedings of the International Population Conference, Liège (Vol. 1, pp. 53–72). Liège, Belgium: International Union for the Scientific Study of Population. [Google Scholar]

- Copp JE, Giordano PC, Longmore MA, & Manning WD (2019). Desistance from crime during the transition to adulthood: The influence of parents, peers, and shifts in identity. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. Advance online publication. 10.1177/0022427819878220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K. (1963). The theory of change and response in modern demographic history. Population Index, 29, 345–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K. (1983). The future of marriage. Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 36(8), 15–43. [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca S, Clampet-Lundquist S, & Edin K. (2016). Coming of age in the other America. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Eickmeyer KJ (2019). Cohort trends in union dissolution during young adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 81, 760–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickmeyer KJ, & Manning WD (2018). Serial cohabitation in young adulthood: Baby boomers to millennials. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80, 826–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteve A, Lopez-Gay A, Lopez-Colas J, Permanyer I, Kennedy S, Laplante B, . . . Cusido TA. (2016). A geography of cohabitation in the Americas, 1970–2010. In Esteve A. & Lesthaeghe RJ (Eds.), Cohabitation and marriage in the Americas: Geo-historical legacies and new trends (pp. 1–24). Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, & Cui M. (2010). Romantic relationships in emerging adulthood. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fry R. (2013). Young adults after the recession: Fewer homes, fewer cars, less debt. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/02/21/young-adults-after-the-recession-fewer-homes-fewer-cars-less-debt/3/

- Furstenberg FF Jr. (2010). On a new schedule: Transitions to adulthood and family change. Future of Children, 20(1), 67–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC, Manning WD, Longmore MA, & Flanigan CM (2012). Developmental shifts in the character of romantic and sexual relationships from adolescence to young adulthood. In Booth A, Brown SL, Landale NS, Manning WD, & McHale SM (Eds.), Early adulthood in family context (pp. 133–164). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo KB (2014). Trends in cohabitation outcomes: Compositional changes and engagement among never-married young adults. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 826–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo KB, & Dorius C. (2016). Challenges in measuring and studying multipartnered fertility in American survey data. Population Research and Policy Review, 35, 553–579. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern-Meekin S, Manning WD, Giordano PC, & Longmore MA (2013). Relationship churning in emerging adulthood: On/off relationships and sex with an ex. Journal of Adolescent Research, 28, 166–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemez P. (2018). Young adulthood: Cohabitation, birth and marriage experiences (Family Profile No. FP-18–22). Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research, Bowling Green State University. Retrieved from 10.25035/ncfmr/fp-18-22 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hemez P, Guzzo KB, Manning WD, Brown SL, & Payne KK (2018, April). Two decades of change in women’s ages at first sex, premarital cohabitation, marriage and birth. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, Denver, CO. [Google Scholar]

- Jones JM (2016). Same-sex marriages up one year after supreme court verdict. Gallup Social & Policy Issues. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/193055/sex-marriages-one-year-supreme-court-verdict.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Kantrowitz M. (2015). Who graduates with excessive student loan debt? (Student Aid Policy Analysis Papers). Retrieved from http://www.studentaidpolicy.com/excessive-debt/Excessive-Debt-at-Graduation.pdf

- Kennedy S, & Ruggles S. (2014). Breaking up is hard to count: The rise of divorce in the United States, 1980–2010. Demography, 51, 587–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo J, & Raley RK (2016). Diverging patterns of union transition among cohabitors by race/ethnicity and education: Trends and marital intentions in the United States. Demography, 53, 921–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperberg A. (2014). Age at co-residence, premarital cohabitation, and marriage dissolution, 1985–2009. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 352–369. [Google Scholar]

- Lamidi EO, Manning WD, & Brown SL (2019). Change in the stability of first premarital cohabitation among women in the United States, 1983–2013. Demography, 56, 427–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante B, & Fostik A. (2016). Cohabitation and marriage in Canada. The geography, law and politics of competing views on gender equality. In Esteve A. & Lesthaeghe RJ (Eds.), Cohabitation and marriage in the Americas: Geo-historical legacies and new trends (pp. 59–100). Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe RJ, Lopez-Colas J, & Neidert L. (2016). The social geography of unmarried cohabitation in the USA, 2007–2011. In Esteve A. & Lesthaeghe RJ (Eds.), Cohabitation and marriage in the Americas: Geo-historical legacies and new trends (pp. 101–132). Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Sassler S, & Turner RN (2014). Cohabitation, post-conception unions and the rise of nonmarital fertility. Social Science Research, 47, 134–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD (2015). Cohabitation and child wellbeing. Future of Children, 25(2), 51–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Brown SL, & Payne KK (2014). Two decades of stability and change in age at first union formation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 247–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Brown SL, & Stykes B. (2015). Trends in births to single and cohabiting mothers (Family Profile No. FP-15–03). Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research, Bowling Green State University. Retrieved from https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/FP-15-03-birth-trends-single-cohabiting-moms.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, & Cohen JA (2012). Premarital cohabitation and marital dissolution: An examination of recent marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 377–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Joyner K, Hemez P, & Cupka C. (2019a). Measuring cohabitation in national surveys. Demography, 56, 1195–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, & Smock PJ (2005). Measuring and modeling cohabitation: New perspectives from qualitative data. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 989–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Manning W., & Smock P. (2009). Divorce-proofing marriage: Young adults’ views on the connections between cohabitation and marital longevity (NCFR Report 54). St. Paul, MN: National Council on Family Relations. [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Smock PJ, & Bergstrom-Lynch C. (2009). Cohabitation and parenthood: Lessons from focus groups and in-depth interviews. In Peters HE & Kamp Dush CM (Eds.), Marriage and family: Perspectives and complexities (pp. 115–142). New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Smock PJ, & Fettro MN (2019b). Cohabitation and marital expectations among single Millennials in the U.S. Population Research and Policy Review, 38, 327–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Smock PJ, & Kuperberg A. (Forthcoming). Cohabitation and marital dissolution: A comment on Rosenfeld and Roesler. Journal of Marriage and Family. [Google Scholar]

- Martin S, Astone N, & Peters H. (2014). Fewer marriages, more divergence: Marriage projections for millennials to age 40. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/22586/413110-Fewer-Marriages-More-Divergence-Marriage-Projections-for-Millennials-to-Age-.PDF [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy J. (2018, May 23). Two in three Americans support same-sex marriage. Gallup Politics. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/234866/two-three-americans-support-sex-marriage.aspx [Google Scholar]

- McClain LR (2011). Cohabitation: Parents following in their children’s footsteps? Sociological Inquiry, 81, 260–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AJ, Sassler S, & Kusi-Appouh D. (2011). The specter of divorce: Views from working-and middle-class cohabitors. Family Relations, 60, 602–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills M, & Blossfeld H-P (2005). Globalization, uncertainty and the early life course: A theoretical framework. In Blossfeld H-P, Klijzing E, Mills M, & Kurz K. (Eds.), Globalization, uncertainty, and youth in society (pp. 1–24). London, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Musick K, & Bumpass L. (2012). Reexamining the case for marriage: Union formation and changes in well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musick K, & Michelmore K. (2018). Cross-national comparisons of union stability in cohabiting and married families with children. Demography, 55, 1389–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel-Miller CM (2011). Partner caregiving in older cohabiting couples. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66B, 341–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK (2003). Cohabiting and marriage during young men’s career-development process. Demography, 40, 127–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK, & Kalmijn M. (1995). Life-cycle jobs. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 14, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Payne KK (2011). Leaving the parental home (Family Profile No. FP-11–02). Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research, Bowling Green State University. Retrieved from http://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/FP-11-02.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Payne KK (2019). Young adults in the parental home, 2007 & 2018 (Family Profile No. FP-19–04). Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research, Bowling Green State University. 10.25035/ncfmr/fp-19-04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perelli-Harris B, & Lyons-Amos M. (2015). Changes in partnership patterns across the life course: An examination of 14 countries in Europe and the United States. Demographic Research, 33, 145–178. 10.4054/DemRes.2015.33.6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2018). The age gap in religion around the world (Religion & Public Life Demographic Study). Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewforum.org/2018/06/13/the-age-gap-in-religion-around-the-world/ [Google Scholar]

- Powell B, Bolzendahl C, Geist C, & Steelman L. (2010). Counted out: Same-sex relations and Americans’ definitions of family. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Prince BF, Joyner K, & Manning WD (2020). Sexual minorities, social context, and union formation. Population Research and Policy Review, 39, 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Raymo JM, Park H, Xie Y, & Yeung WJ (2015). Marriage and family in east Asia: Continuity and change. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 471–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhold S. (2010). Reassessing the link between premarital cohabitation and marital instability. Demography, 47, 719–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss RR (1991). The young adult years: Diversity, structural change, and fertility. Demography, 28, 493–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld MJ, & Roesler K. (2019). Cohabitation experience and cohabitation’s association with marital dissolution. Journal of Marriage and Family, 81, 42–58. [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S, Cunningham A, & Lichter DT (2009). Intergenerational patterns of union formation and relationship quality. Journal of Family Issues, 30, 757–786. [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S., Michelmore K., & Qian Z. (2018). Transitions from sexual relationships into cohabitation and beyond. Demography, 55, 511–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S, & Miller AJ (2017). Cohabitation nation: Gender, class, and the remaking of relationships. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA Jr., Furstenberg FF Jr., & Rumbaut RG (Eds.). (2005). On the frontier of adulthood: Theory, research, and public policy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Silva JM (2012). Constructing adulthood in an age of uncertainty. American Sociological Review, 77, 505–522. [Google Scholar]

- Silva JM (2013). Coming up short: Working-class adulthood in an age of uncertainty. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smock PJ (2000). Cohabitation in the United States: An appraisal of research themes, findings, and implications. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Smock P, Manning W, & Dorius C. (2013). The intergenerational transmission of cohabitation in the U.S.: The role of parental union histories (PSC Research Report No. 13–791). Ann Arbor, MI: Population Studies Center. [Google Scholar]

- Smock PJ, Manning WD, & Porter M. (2005). “Everything’s there except the money”: How money shapes decisions to marry among cohabitors. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 680–696. [Google Scholar]

- Stykes B. (2015). Generation X and Millennials: Attitudes about having & raising children in cohabiting unions (Family Profile No. FP-15–13). Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research, Bowling Green State University. Retrieved from https://www.bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/stykes-gen-x-millennials-fp-15-13.html [Google Scholar]

- Stykes JB, & Guzzo KB (2019). Multiple-partner fertility: Variation across measurement approaches. In Schoen R. (Ed.), Analytical family demography (pp. 215–239). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Sum A, & Khatiwada I. (2010). The nation’s underemployed in the “Great Recession” of 2007–09. Monthly Labor Review, 133(11), 3–15 Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2010/11/art1full.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Tumin D, Han S, & Qian Z. (2015). Estimates and meanings of marital separation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 312–322. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). Table MS-2. Estimated median age at first marriage, by sex: 1890 to the present. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/families/marital.html [Google Scholar]

- Vespa J. (2014). Historical trends in the marital intentions of one-time and serial cohabitors. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 210–217. [Google Scholar]

- Waller MR (2001). High hopes: Unwed parents’ expectations about marriage. Children and Youth Services Review, 23, 457–484. [Google Scholar]