Abstract

The occurrence of sporadic rickettsial infections has been consistently undervalued and overlooked, primarily owing to a limited emphasis on routine examinations for rickettsioses in clinical practice. At present, the immunofluorescence assay is the prevailing diagnostic method for suspected rickettsioses that enables the detection of specific antibodies against rickettsia in human serum. Herein, we present an exceptional instance of rickettsial infection that was characterized by a rare manifestation of extensive pericardial effusion leading to dyspnea and cardiac tamponade. A diagnosis of chronic fibrosing pericarditis was established based on pericardium tissue obtained through pericardiotomy, and a conclusive metagenomic next-generation sequencing test confirmed the presence of Rickettsia felis infection. The cat flea, scientifically known as Ctenocephalides felis, is the predominant carrier of R. felis. An escalating incidence of human R. felis infections has raised concerns, particularly in light of the burgeoning population of domesticated animals in many contemporary societies.

1. Introduction

Among the expansive array of arthropods, including fleas, ticks, mites, and lice, the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis) is widely acknowledged as the principal reservoir of Rickettsia felis bacteria [1]. A recent report highlighted the emergence of mosquitoes as carriers of R. felis in the United States [2].

The clinical manifestations of human R. felis infection, commonly referred to as flea-borne spotted fever or cat flea typhus, are similar to those of other rickettsial diseases. These similarities manifest as symptoms including fever, rash, myalgia, and headache. Furthermore, in more severe cases, individuals may exhibit additional manifestations such as hepatomegaly, myocarditis, meningoencephalitis, and acute respiratory distress syndrome [3].

Although it was initially recognized as a pathogenic agent in humans in the United States in 1994 [4], R. felis (an intracellular gram-negative bacterium) continues to be underestimated, despite advancements in serological and molecular diagnostic techniques such as immunofluorescence assay (IFA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR). This lack of recognition can be attributed to the limited emphasis placed on the routine examination of rickettsioses in clinical practice. Consequently, it is possible that a significant proportion of human cases are not accurately diagnosed.

In this report, we present a unique case of R. felis infection that was characterized by an uncommon clinical manifestation of dyspnea and cardiac tamponade caused by extensive pericardial effusion. The diagnosis was validated through an examination of the collected pericardial fluid using a novel metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) test, which provided conclusive results.

2. Case Presentation

A 79-year-old female patient was admitted to the intensive care unit with dyspnea lasting one week and cardiac tamponade, which was determined through echocardiography to be caused by substantial pericardial effusion of unclear origin. Her medical history included the following: (1) a history of breast cancer with a left mastectomy in 2008 and a partial right mastectomy in 2015; (2) prior instances of ventricular fibrillation and long QT syndrome, which prompted the implantation of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) in 2013; (3) paroxysmal atrial fibrillation under direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) since 2013; (4) type 2 diabetes mellitus; and (5) hyperlipidemia.

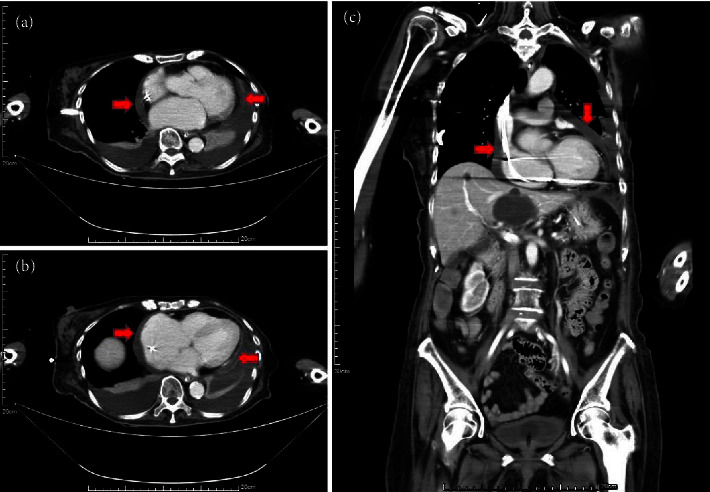

Computed tomography revealed bilateral pleural effusion and suggested the presence of cardiac tamponade caused by a substantial pericardial effusion (Figure 1). Initially, a pericardiocentesis procedure extracted 1030 cc of dark red drainage. The patient was additionally administered 4.5 g of tazocin (sodium piperacillin 2.0 g + sodium tazobactam 0.25 g) intravenously every 8 hours for 14 days, as part of a routine antibiotic treatment for suspected lung infection.

Figure 1.

Transverse plane (a, b) and coronal plane (c) computed tomography (CT): observed pericardial effusion (red arrows) with relative hyperdensity of the collections and suspected cardiac tamponade.

In response to the recurrent accumulation of pericardial and pleural effusions, a surgical pericardial-pleural window and pleurodesis were performed. To test for potential tuberculosis, the collected bloody pericardial fluid was subjected to routine analysis, cytology, and culture. Additionally, two pieces of pericardial tissue (measuring 3 × 4 cm and 2 × 6 cm) were excised anterior to the phrenic nerve for pathological examination.

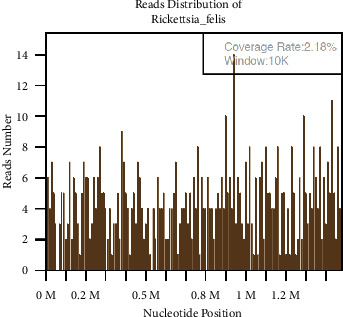

Conclusive pathological findings from the pericardial fluid and tissue demonstrated an absence of malignant cells. A subsequent mNGS test was performed to examine the pericardial fluid and serum blood samples for the presence of other infectious pathogens, owing to negative results obtained on a tuberculosis test. Nucleic acids were extracted from the collected samples using a TIANamp Micro DNA Kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) and then used for library construction with a MGIEasy Cell-free DNA Library Prep Kit (MGI Tech Co., Ltd, Shenzhen, China) and high-throughput sequencing on the MGISEQ-200 platform (MGI Tech Co., Ltd, Shenzhen, China). High-quality sequencing data were generated by removing short (<35 bp), low-quality, and low-complexity reads. Human reads were removed by mapping to the human reference genome hg38 (GRCh38, December 2017) using the Burrows–Wheeler Aligner. The remaining data were compared to the Microbial Genome Database (https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/) using the Burrows–Wheeler Alignment tool v0.7.10-r789. Our mNGS results indicated the presence of Rickettsia felis (275 reads) that accounted for 2.18% of nucleotide sequence coverage and showed 62.29% relative abundance in the pericardial fluid (Table 1, Figure 2) but was not detected in the blood. This prompted the addition of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily to the treatment regimen for 10 days, in accordance with relevant treatment guidelines [5]. A thorough investigation of the patient's history, as well as that of her family, revealed that the potential pathogen originated from a domesticated cat that lived in the patient's household.

Table 1.

Results of mNGS on our patient's pericardial fluid.

| Genus | Species | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Pathogen | Reads | Genus relative abundance (%)∗ | Pathogen | Reads | Coverage (%) | Species relative abundance (%)∗∗ |

| G-bacteria | Rickettsia | 910 | 93.15 | Rickettsia felis | 275 | 2.18 | 62.29 |

∗ Relative abundance at the genus level refers to the proportion of detected microorganisms within the genus in the entire sample. ∗∗Relative abundance at the species level refers to the proportion of detected microorganisms within the species in the entire sample.

Figure 2.

Results of mNGS analysis on the patient's pericardial fluid. The sequenced gene fragment regions were widely distributed across different locations on the Rickettsia felis genome. This indicated that the detected reads did not originate from single-fragmented DNA pieces through repeated sequencing but rather came from the entire genome, thus proving the presence of Rickettsia felis in the sample.

The patient recovered from the illness, showing regression of the lung infection on chest radiography, and a decrease in pleural and pericardial effusions. The patient was discharged after completing the doxycycline treatment.

3. Discussion

Rickettsial infections are categorized into four groups, based on phenotypic and genetic characteristics. These include (1) the ancestral group (AG); (2) the typhus group (TG)—of which Rickettsia typhi is the most common member; (3) the spotted fever group (SFG)—which includes Rickettsia rickettsia; and (4) the transitional group (TRG)—containing Rickettsia felis [6].

IFA has become the standard and most commonly used method to detect specific antibodies against R. felis in the serum. However, a notable limitation arises because of cross-reactivity among various Rickettsiae species. Higher concentrations of antibodies against R. felis may potentially aid in distinguishing R. felis infections from other rickettsial diseases [7]. An additional diagnostic technique used to detect R. felis infection involves the use of PCR to amplify specific gene fragments of R. felis—including gltA, ompA, ompB, and 17-kDa antigen [6–8]. In contrast to conventional pathogen detection techniques, novel mNGS analysis yields fast and precise pathogen detection and identification [9–11].

R. felis infection is a global health concern in the human population, exhibiting a correlation with febrile ailments that can induce severe or even lethal complications. Its presenting symptoms resemble those observed in other rickettsial diseases—ranging from mild fever, skin rash, cutaneous eschar at the bite site, myalgia, and headache; to less frequent yet more intricate manifestations involving the visceral organs, neurological complications, and the heart [8].

Although relatively rare, a range of neurological manifestations associated with R. felis infection—including hearing loss, photophobia, meningitis, meningoencephalitis, and symptoms resembling polyneuropathy—were comprehensively summarized in a literature review conducted by Zeng et al., spanning the period between 2000 and 2020 [12].

While myocarditis and pericarditis have been extensively documented as the primary cardiac complications associated with various rickettsial infections–including Rickettsia rickettsii, Rickettsia conorii, Rickettsia africae, Rickettsia japonica, and Rickettsia tsutsugamushi [13–15]—there remains a dearth of case reports that have specifically documented cardiac complications related to R. felis infection. Pericardial effusion has been reported to be a manifestation of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi and Rickettsia typhi [16–18]. Additionally, a previous case study reported pericarditis and pericardial effusion associated with Bartonella quintana [19]. However, to date, no published reports have described pericarditis or pericardial effusion associated with R. felis infection.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report to document R. felis infection accompanied by pericarditis and pericardial effusion substantiated by direct pathological evidence obtained from the pericardial fluid, which was confirmed through mNGS.

Misdiagnosis of this type of infection is frequent, owing to inadequate awareness of it and the limited availability of specific laboratory testing required to confirm R. felis involvement. A recent review hypothesized that ∼33% of cat fleas collected from companion dogs and cats in Taiwan are infected with R. felis (although the available data were limited) [6].

Nevertheless, Lai et al. emphasized the long-standing underappreciation and neglect of spotted fever group rickettsioses in southern Taiwan, particularly focusing on species that are closely associated with R. felis [20]. Likewise, Yang et al. conducted a retrospective seroepidemiological analysis in Taiwan involving 122 patients who were suspected of having rickettsioses but tested negative for scrub typhus, murine typhus, or Q fever [21]. This study revealed a seropositivity rate of 19%, indicating exposure to rickettsia. Among these cases, eight individuals had antibodies that were responsive to R. felis—of whom four showed evidence of ongoing R. felis infection and one, whose doxycycline treatment was discontinued because negative results for scrub typhus, Q fever, and murine typhus experienced a fatal outcome.

4. Conclusion

In contrast to other rickettsial diseases in Taiwan, which are primarily transmitted by arthropods in natural habitats, the emergence of Rickettsia felis infection is thought to be associated with the expanding population of companion animals in contemporary society [6, 22, 23]. Therefore, it is imperative to engage in proactive surveillance of patients with unidentified causes of pericardial effusion. Furthermore, beyond conventional antibody detection using IFA, mNGS provides a new method for surveying rare infectious pathogens.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ching-Kai Chuang of Asia Pathogenomics Co., Ltd., for the help of technical assistance in the mNGS test.

Abbreviations

- AG:

Ancestral group

- DOAC:

Direct oral anticoagulants

- ICD:

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

- IFA:

Immunofluorescence assay

- mNGS:

Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing

- PCR:

Polymerase chain reaction

- SFG:

Spotted fever group

- TG:

Typhus group

- TRG:

Transitional group.

Data Availability

All relevant data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital

Consent

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the patient's family.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Brown L. D., Macaluso K. R. Rickettsia felis, an emerging flea-borne rickettsiosis. Current Tropical Medicine Reports . 2016;3(2):27–39. doi: 10.1007/s40475-016-0070-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barua S., Hoque M. M., Kelly P. J., et al. First report of Rickettsia felis in mosquitoes, USA. Emerging Microbes and Infections . 2020;9(1):1008–1010. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1760736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teng Z., Zhao N., Ren R., et al. Human Rickettsia felis infections in mainland China. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology . 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.997315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schriefer M. E., Sacci J. B., Jr., Dumler J. S., Bullen M. G., Azad A. F. Identification of a novel rickettsial infection in a patient diagnosed with murine typhus. Journal of Clinical Microbiology . 1994;32(4):949–954. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.949-954.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biggs H. M., Behravesh C. B., Bradley K. K., et al. Diagnosis and management of tickborne rickettsial diseases: Rocky mountain spotted fever and other spotted fever group rickettsioses, ehrlichioses, and anaplasmosis - United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Recommendations and Reports . 2016;65(2):1–44. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6502a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minahan N. T., Wu W. J., Tsai K. H. Rickettsia felis is an emerging human pathogen associated with cat fleas: A review of findings in Taiwan. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology, and Infection . 2023;56(1):10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2022.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hun L., Troyo A. An update on the detection and treatment of Rickettsia felis. Research and Reports in Tropical Medicine . 2012;3:47–55. doi: 10.2147/rrtm.s24753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reif K. E., Macaluso K. R. Ecology of Rickettsia felis: A review. Journal of Medical Entomology . 2009;46(4):723–736. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller S., Chiu C. The role of metagenomics and next-generation sequencing in infectious disease diagnosis. Clinical Chemistry . 2021;68(1):115–124. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvab173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xing X. W., Zhang J. T., Ma Y. B., et al. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing for diagnosis of infectious encephalitis and meningitis: A large, prospective case series of 213 patients. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology . 2020;10:p. 88. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stewart A. G., Stewart A. G. A. An update on the laboratory diagnosis of Rickettsia spp. infection. Pathogens . 2021;10(10):p. 1319. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10101319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeng Z., Wang C., Liu C., et al. Follow-up of a Rickettsia felis encephalitis: Some new insights into clinical and imaging features. International Journal of Infectious Diseases . 2021;104:300–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.12.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellini C., Monti M., Potin M., Ave A. D., Bille J., Greub G. Cardiac involvement in a patient with clinical and serological evidence of African tick-bite fever. BMC Infectious Diseases . 2005;5(1):p. 90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-5-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukuta Y., Mahara F., Nakatsu T., Yoshida T., Nishimura M. A case of Japanese spotted fever complicated with acute myocarditis. Japanese Journal of Infectious Diseases . 2007;60(1):59–61. doi: 10.7883/yoken.jjid.2007.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang J. H., Ju M. S., Chang J. E., et al. Pericarditis due to Tsutsugamushi disease. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases . 2000;32(1):101–102. doi: 10.1080/00365540050164344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ki Y. J., Kim D. M., Yoon N. R., Kim S. S., Kim C. M. A case report of scrub typhus complicated with myocarditis and rhabdomyolysis. BMC Infectious Diseases . 2018;18(1):p. 551. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3458-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang K.-W., Kim W. Scrub typhus with complications of acute myocarditis and cardiac tamponade in metropolitan areas: Two case reports. Kosin Medical Journal . 2023;38(3):210–214. doi: 10.7180/kmj.23.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kao P.-T., Lee C.-M., Liu C.-P., Lin H.-C., Tseng H. K. Murine typhus with pneumonitis and pleuropericarditis: A case report. 2003. https://icim2006-taipei.org.tw/journal/jour14-6/P14_301.PDF .

- 19.Levy P. Y., Fournier P. E., Carta M., Raoult D. Pericardial effusion in a homeless man due to Bartonella quintana. Journal of Clinical Microbiology . 2003;41(11):5291–5293. doi: 10.1128/jcm.41.11.5291-5293.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai C. H., Chang L. L., Lin J. N., et al. Human spotted fever group rickettsioses are underappreciated in southern Taiwan, particularly for the species closely-related to Rickettsia felis. PLoS One . 2014;9(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095810.e95810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang W. H., Hsu M. S., Shu P. Y., Tsai K. H., Fang C. T. Neglected human Rickettsia felis infection in Taiwan: A retrospective seroepidemiological survey of patients with suspected rickettsioses. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases . 2021;15(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009355.e0009355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoque M. M., Barua S., Kelly P. J., Chenoweth K., Kaltenboeck B., Wang C. Identification of Rickettsia felis DNA in the blood of domestic cats and dogs in the USA. Parasites and Vectors . 2020;13(1):p. 581. doi: 10.1186/s13071-020-04464-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perez-Osorio C. E., Zavala-Velazquez J. E., León J. J. A., Zavala-Castro J. E. Rickettsia felis as emergent global threat for humans. Emerging Infectious Diseases . 2008;14(7):1019–1023. doi: 10.3201/eid1407.071656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.