Abstract

Despite the widespread prevalence and important medical impact of insomnia, effective agents with few side effects are lacking in clinics. This is most likely due to relatively poor understanding of the etiology and pathophysiology of insomnia, and the lack of appropriate animal models for screening new compounds. As the main homeostatic, circadian, and neurochemical modulations of sleep remain essentially similar between humans and rodents, rodent models are often used to elucidate the mechanisms of insomnia and to develop novel therapeutic targets. In this article, we focus on several rodent models of insomnia induced by stress, diseases, drugs, disruption of the circadian clock, and other means such as genetic manipulation of specific neuronal activity, respectively, which could be used to screen for novel hypnotics. Moreover, important advantages and constraints of some animal models are discussed. Finally, this review highlights that the rodent models of insomnia may play a crucial role in novel drug development to optimize the management of insomnia.

Keywords: rodent models, insomnia, drug discovery, hypnotics, sleep–wake profile

Introduction

Overview and prevalence of insomnia

Sleep is a highly conserved innate behavior. With the rapid advancement and application of state-of-the-art technologies, significant progress has been made in the study of neural circuits governing sleep–wake regulation. Recent studies have revealed the presence of an intricate sleep and wake regulation system in the brain, consisting of numerous neural nuclei and transmitters that form an interconnected neural network responsible for mutual interaction and regulation [1–3]. The neuronal circuits underlying the sleep–wake system are modulated by both circadian rhythm and homeostasis, which collectively determine the initiation and maintenance of sleep and wakefulness. However, insomnia has emerged as an increasingly grave social and medical concern due to societal competition, work-related stressors, an ageing population, and, particularly, unhealthy lifestyle habits prevalent in today’s information-driven society.

Insomnia is the most common sleep disorder, which is characterized by persistent challenges in sleep initiation, duration, consolidation, or quality, despite adequate opportunity for sleep, coupled with resultant daytime dysfunction in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders Third Edition (ICSD-3). It has been seen that 33% of the adult population reported insomnia (symptoms) [4]. Insomnia can be classified into three categories based on ICSD-3: chronic insomnia disorder, short-term insomnia disorder, and other insomnia disorder.

Insomnia is characterized by dissatisfaction with the quantity or quality of sleep, associated with difficulty falling asleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, frequent nighttime awakenings with difficulty returning to sleep, and/or awakening earlier in the morning than desired for a period of time, such as at least three months. The disorder results in a set of significantly impaired daytime functioning, including reduced alertness, fatigue, exhaustion, dysphoria and other symptoms. Insomnia negatively affects physical and social performance, the ability to work efficiently, and the quality of life, and has thus become an important public health issue.

Current treatment and limitations

Treatment options for patients with insomnia include sleep hygiene education, cognitive and behavioral therapies, and pharmacotherapy [5, 6]. Maintaining good sleep hygiene may sometimes become difficult in modern societies, and cognitive and behavioral therapies can be time-consuming, although quite effective [7]. For pharmacological treatment, the benzodiazepines and the non-benzodiazepines ‘Z’ drugs (zolpidem, zopiclone and zaleplon) that target the GABAergic system are the most widely used hypnotics [8, 9]. Although these medications are recognized for their safety and therapeutic benefits, their use is not without adverse effects. These include residual drowsiness, the risk of abuse and dependence, as well as possible impairments in memory, cognitive function, and psychomotor abilities. Additionally, they are associated with an increased risk of falls, accidents, and could potentially increase mortality. Therefore, their use for long-term treatment is not recommended [10–12].

In addition to GABA agonists, selective melatonin receptor agonist ramelteon has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of insomnia characterized by delayed onset of sleep. In chronic insomnia, ramelteon decreases sleep latency but is ineffective in improving sleep maintenance [13]. Selective histamine H1 receptor antagonist doxepin is a tricyclic antidepressant originally approved in 1969 for the treatment of depression at doses up to 300 mg. In 2010, the FDA approved 3 mg and 6 mg doses for the treatment of insomnia characterized by difficulty with sleep maintenance. However, doxepin is not considered a first-line pharmacological treatment, perhaps due to side effects and limited evidence for efficacy [5, 14]. These results suggest that drug options for treating insomnia are limited by side effects and an inability to mimic physiological sleep.

Need of animal models in drug discovery

Although pharmacologic therapy for insomnia has advanced over time, ideal drugs that induce physiological sleep without significant adverse effects such as sedation, drowsiness or dependence are deficient in clinic [15]. This is most likely due to our relatively poor understanding of the etiology and pathophysiology of insomnia, as well as the lack of appropriate animal models for screening new compounds. Although rodent sleep is characterized by short bouts of sleep with rapid changes in sleep stage, more discontinuous compared to normal human sleep, the main homeostatic, circadian and neurochemical modulations of sleep remain essentially similar between species [16–19], suggesting that insomnia in human and rodent also share common underlying mechanisms. Sleep parameters in human subjects such as sleep onset latency, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep onset latency, slow-wave activity, total sleep time and number of awakenings can easily be measured in rodents, and the effect of pharmacological challenges on these parameters in rodents is a good predictor of likely human response [20]. In addition, rodent models offer a significantly better option for studying the neuroanatomical and neurochemical components of the sleep–wake cycle, and for identifying the brain circuitry involved in normal sleep and disease states. Therefore, modelling human insomnia in rodents thus paves the way for the discovery of potential therapeutic targets and their underlying molecular interactions.

The current article summarizes the potential and existing rodent models of insomnia, including stress-related models, models derived from disease and pathophysiological conditions, pharmacological models, models based on perturbations of the circadian system, and genetic manipulation models (Table 1).

Table 1.

Models in rodents of insomnia.

| Models in rodents of insomnia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Paradigm | Typical sleep characteristics | Advantages | Disadvantages | Reference |

| Stress-related models | |||||

| Cage exchange | Mice moved to a clean cage | Increased in latency to REM and NREM sleep and the amount of wakefulness, and decreases in the amount of NREM and REM sleep, with a lower power density of NREM sleep, increased fragmentation, and decreased stage transitions from NREM sleep to wake | Simple, similar to the “first night effect” in human beings, have been well built in drug screening | – | [21–24] |

| Electric foot shock | Rodents receive electric shocks from the floor to prevent physiological sleep | Sleep fragmentation, the total duration of wakefulness was significantly increased, and REM sleep was significantly decreased | Simple, the stress-induced sleep fragmentation can be prevented by certain drugs, mimicking the stress-induced insomnia | No physiological insomnia, long-term footshock causes REM sleep increase, ethical issues | [26, 36] |

| Pain | Sciatic nerve injury (CCI and PSL) | Increased sleep latency and total waking time, sleep fragmentation, reduced NREM sleep | Sleep disturbances similar to those of human suffering pain, have been well built in drug screening | Ethical issues | [41, 42] |

| Environmental noise | Chronic exposed to environmental noise, intermittent broad-band noise | Increased wakefulness and reduced sleep, disturbed NREM and REM sleep; increased fragmentation of NREM and REM sleep. | Mimicking human conditions | Not yet validated with hypnotic drugs | [49, 50] |

| Gentle handling | Keeping the animal awake by stimulating it whenever it was observed to be drowsy | Keep awake, both NREM and REM sleep were decreased | Simple | Long- term operation | [56] |

| Communication box model | Subjects exposed to residents, footshocks, predators directly. The example is social defeats model, which based on the resident-intruder paradigm, in which the resident animal will attack the intruder in its home cage | Reduced active waking and enhanced light sleep during the dark phase, and increased frequency of transitions from light sleep to quiet wakefulness | Simple, dose-dependent | High stress, not physiological, different effects on sleep between one time and repeated social defeat stress, ethical issues | [61, 62] |

| Predator threat | Subjects exposed to awakening odors (predator, congeners, etc) | Difficulty in falling asleep, increased wakefulness, reduced NREM and REM sleep, increased wake and NREM bout frequencies, reduced NREM sleep duration and power | Simple, mimicking the stress-induced insomnia | Not yet validated with hypnotic drugs, difficulty in controlling odor spreading and concentration | [63] |

| Immobilization | Chronic immobilization | Large decrease in sleep efficiency (total sleep time), NREM and REM sleep | Simple | Ethical issues | [64] |

| Food deprivation | Food deprivation | Fasting enhances arousal effect of caffeine | Simple, mimicking fasting | Ethical issues | [67] |

| Grid suspended over water | Placing animals on a grid suspended over water up to 1 cm under the grid surface | Increase in sleep latency and the amount of wakefulness, reduced NREM and REM sleep | Simple, useful to evaluate the hypnotic properties of drugs | Ethical issues | [71] |

| Novel object | Mice were exposed to novel object or running wheel | Increased wakefulness, decreased NREM and REM sleep | Simple | – | [73] |

| Disease-related models | |||||

| Psychological stress (PTSD) | Subjects exposed to repeated stressors or various stressors in a time order, such as repeated social defeats, single prolonged stress, and repeated foodshock | Increased wakefulness, reduced NREM and REM sleep, sleep fragmentation, PTSD-like sleep–wake and qEEG spectral power abnormalities | Mimicking humans suffering from unexpected severe mental/physic damages, well built in drug screening | High stress, not physiological insomnia, ethical issues | [77, 79] |

| Menopausal transition | Ovariectomy (OVX), daily injection of 4-vinylcyclohexene diepoxide (VCD) | In OVX model, NREM and REM sleep increased during dark phase; In VCD model, REM and NREM sleep decreased | VCD model mimics the physiological changes to the hormonal milieu that characterize the perimenopausal transition to menopause; Providing an insight of opportunity for preventing insomnia in menopausal women | A drawback of the OVX model is that the sudden loss of ovarian steroids is not a characteristic of the vast majority of menopausal women; the model is not exactly the same as humans | [87] |

| Depression | |||||

| Olfactory bulbectomy (OBX) | Olfactory bulbectomy (OBX) | REM sleep increased | Well known model for depression | Increasing REM sleep, ethical issues | [96] |

| Chronic mild stress model | Rearing on a wire net for 3 weeks | Attenuated NREM sleep, with decreased mean bout duration of NREM sleep and increased episode number of NREM sleep | Simple | Ethical issues | [97] |

| Genetic helpless model | Genetic helpless model | Exhibited more sleep fragmentation, and increased REM sleep amounts and decreased latency | Helpful for investigating the neurobiological mechanisms and possibly genetic substrates underlying sleep alterations associated with depression | – | [98, 99] |

| Neurodegenerative diseases | |||||

| Alzheimer’s disease | Transgenic mice models of Alzheimer’s disease | Frequent arousals from sleep and fragmented sleep, NREM and REM sleep reduced | Insomnia and pathological characteristics are consistent with the changes seen in AD patients | Not yet validated with hypnotic drugs, restricted to transgenic mice only | [105, 107, 108] |

| Parkinson’s disease | Treated by 6-OHDA, MPTP, or Rotenone; Transgenic Thy1-aSyn mice models of PD | Decreased NREM sleep and enhanced wakefulness in 6-OHDA and MPTP-treated rodents; Increased NREM sleep during the light phase, increased active wake during the dark phase, decreased REM sleep over a 24-h period, and a significant decrease in gamma power in wakefulness in Thy1-aSyn mice | Thy1-aSyn mice mimic the PD disease and help to assess the mechanisms and therapeutic strategies for sleep dysfunction in PD | Ethical issues in toxin-based animal models | [114, 125] |

| Narcolepsy | OX-tTA; Pmch-tTA; TetODTA mice | Increased wake and cataplexy, both NREM and REM sleep were decreased | Beneficial to new drugs for co-morbidity of insomnia and narcolepsy | Unspecific insomnia | [130, 131] |

| Pharmacological intervention-related models | |||||

| Caffeine | Blocks adenosine A2A receptors | Increased sleep latency, decreased NREM sleep, decreased delta activity | Simple, peripheral administration, as a suitable tool for drug screening | There are differences in hypnotic effects of caffeine | [140–142] |

| Histamine | To increase histamine by H1 receptors agonist, and blocks histamine H3 receptor neurotransmission | H1R agonist or H3R antagonist caused an increase in wakefulness and decrease in NREM sleep | Simple and consistent models of insomnia, peripheral administration | Not yet validated with hypnotic drugs | [153, 154] |

| Dopamine and psychostimulants | Enhances monoamines (dopamine) neurotransmission | Increased wakefulness, prolonged the latency of NREM sleep, reduced NREM sleep | Simple, peripheral administration, strong awakening | Psychostimulants may be limited due to their potential for abuse and side effects such as addiction | [163, 167] |

| Morphine | Vigilance enhancement (mode of action not yet resolved) | Increased wakefulness and decreased NREM and REM sleep in a dose-dependent manner | Simple, peripheral administration | Addiction, abuse potential | [177, 178] |

| Ethanol exposure and withdrawal | Cessation of chronic ethanol administration causes transient sleep loss | During ethanol withdrawal, wakefulness increased, sleep decreased | Peripheral administration | Abuse potential | [188] |

| Hypocretin | Hyperactive hypocretin system can result in hyperarousal episodes and insomnia | Increased wakefulness, decreased NREM and REM sleep | Peripheral administration, validated with hypnotic drugs | Side-effects is next day somnolence | [193] |

| Circadian clock-related models | |||||

| Light intensity and photoperiod | Animals were submitted for 14 days light–dark 16:8, and had a sleep deprivation after LD 16:8 photoperiod | The sleep rebound and sleep intensity related to sleep deprivation recovery after LD 16:8 photoperiod was lower for at least 24 h | – | The experimental process is complex, ethical issues | [201, 202] |

| Clock gene mutant | Mice bearing a mutation in the circadian clock gene | Sleep fragmentation increased in Bmal1 mice, whereas mPer2 mutants had less NREM sleep and REM sleep in the last 3 h before dark onset, and the phase advance of motor activity onset | mPer2 mutations are suitable for the study of advanced sleep phase syndrome | Restricted to mice only, not yet validated with hypnotic drugs | [206, 209] |

| Delayed or advanced sleep phase (DSPS) | Clock mutant mice | Constant light (LL) housing significantly caused a delayed onset of locomotor activity, resulting in evening preference | Mimicking the delayed sleep phase syndrome | Restricted to mice only, not yet validated with hypnotic drugs | [213] |

| Genetic manipulation models | Genetic activation, inhibition, or ablation of specific neurons in local brain regions | Induced long time wakefulness in rodents | Invasive, useful to mimic different types of insomnia with temporal-spatial specificity, a good tool to test new drugs for co-morbidity of insomnia | Ethical issues | [161, 214, 216–218] |

Stress-related models

Cage exchange

The unfamiliar environment is generally considered to disturb sleep during the first night, which is called the “first night effect”. In humans, the first-night effect is most frequently characterized by lower sleep efficiency, increased wakefulness, longer non-rapid eye movement (non-REM, NREM) and REM sleep latency, and decreased duration of REM sleep during initial lab recording nights compared to subsequent nights [21, 22].

To mimic the insomnia symptom in humans induced by a new environment, cage change is used to evaluate the sleep behaviors of the first-night effect in rodents by analyzing the EEG/Electromyography (EMG) recordings. Mice moved to a clean cage (MCC) showed increases in latency to REM and NREM sleep and the amount of wakefulness, and decreases in the amount of NREM and REM sleep, with a lower power density of NREM sleep, increased fragmentation and decreased stage transitions from NREM sleep to wake, and higher variation in plasma corticosterone levels during the first 3 h after cage change (Fig. 1a) [23, 24]. Hypnotics zolpidem and diazepam suppressed cage change-induced wakefulness, accelerated the recovery of NREM sleep, and significantly increased NREM and REM sleep [24]. These results suggest that an MCC mouse can mimic the first-night effect phenotype in humans, thus providing a model for drug screening.

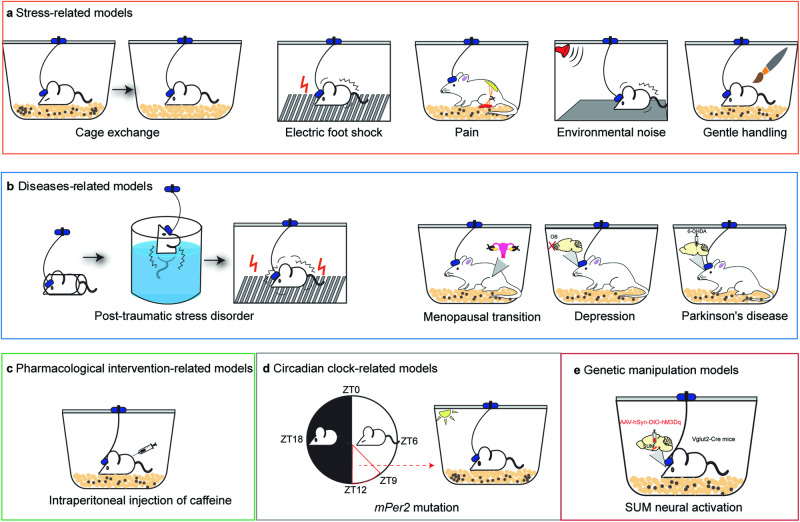

Fig. 1. Modeling of insomnia in rodents.

a Stress-related factors increase wakefulness in rodents, such as cage exchange, electric foot shock, pain, environmental noise, and gentle handling. b Diseased-related models are often used to characterize increased arousal or non-restorative sleep. c Pharmacological intervention increases wakefulness by intraperitoneal injection of caffeine, adenosine, histamine, morphine, and so on. d Mutation of circadian clock genes, such as mPer2, leads to the disruptions of sleep–wake cycles. e There are lots of potential insomnia models in rodents. As is shown, chemogenetic activation of glutamatergic neurons in the SUM induced prolonged wakefulness in mice.

In rodents, dirty cage change also induces a significant delay in both latency for NREM and REM sleep, and an increase in wakefulness and decreases in NREM and REM sleep, furthermore, there are fewer transitions from NREM to REM sleep, and more to wakefulness, indicating sleep fragmentation [24, 25]. However, compared to the dirty cage change, the clean cage change is a better rodent model to mimic the first night effect in humans [24].

Electric foot shock

Stress is one of the main factors that can cause sleep problems. Electric foot shock is a commonly used stress paradigm (Fig. 1a), including both physical as well as emotional components, and it is used as a direct (physical stress) or an indirect stressor (psychological stress).

Electric foot shock as a physical stressor

Direct application of electric foot shocks to animals creates physical stress to induce sleep behavioral changes. The effect of electric foot shock on sleep depends on different stress patterns. For instance, the inescapable foot shock (IS) stimuli significantly reduce REM sleep, while the escapable foot shock stimuli increase REM sleep [26, 27]. Rats were subjected to 5 days of IS, days 1 and 2 of stress increased wakefulness, NREM sleep latency, and REM sleep latency, but decreased the total amount of REM sleep, however, there was a reduction in wakefulness, NREM and REM sleep latency, and an increase in the total amount of REM sleep at days 3–5 [28]. Electric foot shock can cause changes in sleep architecture. Several studies have shown that inescapable footshock significantly decreases NREM episode duration and increases NREM episode number, and the stress-induced sleep fragmentation can be prevented by certain drugs (such as paroxetine and d-cycloserine) [27, 29]. Optogenetics inhibiting glutamatergic cells in the basolateral nuclei of the amygdala during the presentation of IS attenuates an immediate reduction in REM sleep after IS and produces a significant overall increase in REM sleep [30]. In rodents, exposure to foot electroshock is most commonly used to establish various fear stress models (such as post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD)), which show wakefulness after shock and continue to 21 days post-stress [31, 32]. Thus, a foot shock may be a way to establish a model of stress-related insomnia.

Electric foot shock as a psychological stressor

Physical and psychological stress can be induced simultaneously in different rats by means of a communication box. Psychological stress is generated by exposure to emotional responses without direct physical stress, for example, the visual, olfactory and auditory stimuli that arise from foot-shock stressed animals [33, 34]. Several studies showed that communication box-mediated psychological stress reduced REM sleep latency, and significantly enhanced the total amount of REM sleep by prolonging the average duration of REM sleep episodes during the first 3 h of sleep, whereas the total amount of NREM sleep was not influenced [35–37].

Pain

Patients with chronic pain, together with postherpetic neuralgia, diabetic peripheral neuropathy and complex regional pain syndromes, frequently experienced sleep disturbances, such as delayed sleep onset, sleep fragmentation, and difficulty in maintaining sleep and remaining asleep [38–40]. In animals, the sleep–wake cycle is also disrupted in a variety of pain models. In the neuropathic pain models, sciatic nerve injury is often used to mimic human neuropathic pain. When chronic constriction injury (CCI) rats were placed on sandpaper, a significant increase was observed in sleep latency and total waking time compared with the sham group [41, 42]. Partial sciatic nerve-ligated mice exhibited delayed sleep onset, sleep fragmentation, an increase in wakefulness and a decrease in NREM sleep, and the sleep disturbances in neuropathic pain-like conditions lasted for at least 28 days after partial sciatic nerve ligation (PSL) (Fig. 1a) [43–46]. In the inflammatory pain models, Freund adjuvant is administered subcutaneously to mimic human rheumatoid polyarthritis, arthritic rats present a reduction of total sleep time, increased latency to synchronized sleep, augmented number of episodes of synchronized sleep, reduction of sleep efficiency, more stage shifts, and increased total alert time [47, 48].

Environmental noise

Noise is an irritating, screeching sound that is harmful to health. With the development of human activities, noise pollution (such as airports, road traffic, and railway transport) continues to grow. Noise affects both the auditory system and extra-acoustic systems. Sleep disturbance is part of the extra-auditory effect of noise. Moreover, the influence of environmental noise on sleep disturbances extends to its frequencies and intensities, with higher decibel levels and particular frequency ranges typically exacerbating sleep disruption. In order to better understand the underlying mechanisms of environmental noise-induced human sleep disturbances, it is imperative for us to develop a valid and appropriate animal model. To determine the effects of chronic exposure to environmental noise (EN) on sleep–wake cycle, animals were exposed to EN during 9 days. This chronic exposure to EN increases wakefulness and reduces both NREM and REM sleep amounts (Fig. 1a). Subsequent to a nine-day exposure period to EN, there was a notable increase in wakefulness by 16 h, coupled with a decrease in NREM sleep by 10 h, and a deficit of 6 h in REM sleep [49]. Moreover, the experimental group is divided into two subgroups. One subgroup had little or no debt of sleep (Resistant rats or “R” rats), while the other subgroup had a great debt of sleep around 25 h (Vulnerable rats or “V” rats). Evolution of NREM sleep debt showed that a chronic EN exposure induced a more NREM debt in “V” rats than in “R” rats [49, 50]. The EN exposure induced an increase in the number of NREM bouts and a decrease in the duration of NREM bouts compared to the control. In addition, “V” rats have significantly more frequent NREM epochs and shorter NREM bout duration than “R” rats [49]. Rabat observed that exposure to EN led to a marked rise in wakefulness, along with significant reductions in both NREM and REM sleep during the light phase of the cycle. However, EN induced a slight increase in wakefulness and a profound decrease in REM sleep without changes in NREM sleep amount for the dark period [51]. Moreover, continuous broad-band noise (CBBN) and intermittent broad-band noise (IBBN) were used to explore the effect of physical components of EN on sleep–wake cycle, including intensity, intermittency and frequency spectrum. However, CBBN acts indirectly on REM sleep through a reduction of NREM sleep bout duration, whereas IBBN and EN strongly disturbed both NREM and REM sleep. Finally, EN fragments NREM sleep and decreases REM sleep amount during the dark period, whereas IBBN only fragments REM [51]. Some human studies agreed with these findings, showing a stronger and longer deleterious effect of intermittent noise on sleep compared to those of continuous noise [52, 53]. These data demonstrate that all the physical components of EN contribute to the disturbances of NREM and REM sleep. However, it is important to recognize that white noise does not universally promote sleep; certain frequencies can have varying effects. For instance, prolonged exposure to white noise has been observed to reduce sleep latency in humans, highlighting the complexity of noise’s impact on sleep [54].

Gentle handling

Experimental procedures of sleep deprivation (SD), both in humans and in animal models, have been widely employed to study the effects of sleep loss on subsequent brain function at the molecular, cellular, physiological, and cognitive levels [55]. Animals, usually kept in their home cages during the SD procedure, were actively monitored by the experimenter, with or without the support of EEG and EMG recordings. The gentle handling procedure consisted of keeping the animals awake by tapping on their cage and, if necessary, by gently touching or brushing them (Fig. 1a) [56]. The researchers were tasked with keeping the animal awake by stimulating it whenever it was observed to be drowsy or attempting to assume a sleeping position and/or showing signs of low-frequency activity on its EEG.

Communication box model

Communication box models are a type of rodent experimental setup designed for social behavior tests and also induce insomnia-like conditions. These models typically involve subjecting rodents to various environmental or physiological stressors known to disrupt sleep patterns, such as social interaction, and social defeats. In contrast to other models, which suppress NREM sleep or REM sleep, communication box stress facilitates REM sleep. It may serve as a protective function related to a reversal of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation. The study showed the plasma corticosterone was not increased significantly and the HPA axis was not activated in the psychological stress group during sleep recording after stress [36]. Therefore, the psychological stress group may be related more to non-HPA axis factors.

Social interactions

The social environment can affect sleep. In the communication box, rodents normally prefer to spend more time with another rodent (sociability) and will investigate a novel intruder more so than a familiar one (social novelty) [57]. Studies found that rats had high arousal in response to exposure to an environment as social interaction lasted 5 h, which is prevented by selective chemical lesions of the Locus Coeruleus [58].

Social defeats

Social defeat is a potent social stressor with etiological and face validity to several stress-related disorders in humans [59] and has been utilized in several sleep studies to date associated with bullying [60]. In rodent models, the resident-intruder paradigm shows the resident animal or aggressive will attack the intruder. Acute social defeat stress increases sleep in rodents [61] while rodents exposed to repeated social defeat stress are followed by reduced active waking and enhanced light sleep during the dark phase, and increased frequency of transitions from light sleep to quiet wakefulness, indicating sleep instability [62].

Predator threat model

Rodents are macrosmatic animals that rely on odors to convey crucial environmental information, including the presence of food, potential mates, or predators. In this model, mice subjected to the stressor of predator odor exhibit pronounced sleep disturbances. Specifically, they demonstrate challenges in initiating sleep, heightened periods of wakefulness, and reductions in both NREM and REM sleep. Additionally, these mice experience an increased frequency of wake and NREM episodes, alongside a reduction in the duration and intensity of NREM sleep. These behavioral changes mirror the persistent and severe sleep disruptions commonly seen in human PTSD, thereby validating the use of this model to study the disorder [63].

Immobilization

Immobilization is thought to be primarily a ‘psychological’ stressor because there is no pain involved; it is the inability to escape that induces psychological stress. The intensity of stress affects subsequent sleep alterations. Although acute immobilization stress (1–8 h restraint stress) increases sleep [64], extremely long periods of immobilization were associated with decreases in REM and NREM sleep. Papale et al. [65] found that rats subjected to 22 h of immobilization stress each day for 4 consecutive days showed large decreases in sleep efficiency (total sleep time/total recording time), SWS, and REM sleep.

Food deprivation

Fasting has been reported to activate histaminergic neurons in the tuberomammillary nucleus, increase arousal for goal-directed behavior, and also enhance the arousal effect of caffeine in rodents [66, 67]. In addition, food deprivation affects not only histaminergic neurons but also other systems involved in sleep–wake regulation, such as orexin [68] and ghrelin release [69].

Grid suspended over water

The model was built by placing mice or rats on a grid suspended over water up to 1 cm under the grid surface [70, 71]. When the rodents were placed on the grid, there was a significant increase in sleep latency and the amount of wakefulness, compared to subjects placed on sawdust. On the other hand, rodents placed on the grid had significantly lower levels of NREM sleep and REM sleep compared to those placed on sawdust. The model was used to evaluate the protective effect of medicines on behavioral and biochemical alterations by producing sleep-disturbed rodent model [70, 72].

Novel object

Mice subjected to awake during the day via exposure to the novel objects or running wheels [73]. Researchers used novel objects to elicit active exploration, which is different from passive wake via gentle handling (cage shaking, lid removal, etc.) with the specific goal of limiting novelty exposure. Unlike the singleness of the controlled environment of the gentle handling model, the novel object model introduces unfamiliar objects into the rodent’s living space, therefore enhancing environmental complexity. The introduction of novel objects stimulates arousal in mice through the active process of exploring novelty, as opposed to the passive sleep disruption caused by gentle handling. Moreover, the novel object model offers a more ecologically relevant and less stressful simulation of real-world insomnia triggers compared to stress-inducing stimuli like gentle handling or electric foot shock.

Disease-related models

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a complex psychiatric condition that is experienced by a subset of individuals after exposure to a life-threatening event that elicits fear, helplessness, and/or horror. Sleep disturbances including frequent awakenings, nightmares, and reduced slow-wave sleep are hallmark features of PTSD [74]. Polysomnographic studies in chronic PTSD patients as well as recently traumatized individuals have revealed deficits in both REM and NREM sleep, including reduced and fragmented NREM and REM sleep, shortened latency to REM sleep, and increased REM density [75, 76].

Several animal models have been developed and used to understand the pathophysiology of PTSD. The predator threat model is a reliable model of human PTSD that satisfies several criteria of PTSD as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [77, 78]. For the details of the model please see the section in ‘Sensory contact’.

Single prolonged stress (SPS) is a rodent model of PTSD that has been shown to induce multiple PTSD-like physiological and behavioral abnormalities (Fig. 1b) [77]. In an SPS model, rats subjected to various stressors (including restraint stress, forced swim, and ether exposure) displayed an acute and persistent increase in wakefulness with concurrent reductions in time spent in NREM and REM sleep during the light (rodent quiescent) phase, accompanied by state-dependent alterations in quantitative electroencephalography (qEEG) power spectra indicative of cortical hyperarousal, and SPS induces PTSD-like sleep–wake and qEEG spectral power abnormalities that correlate with changes in central serotonin and neuropeptide Y signaling in rats [79]. Thus, SPS represents a preclinical model of PTSD-related sleep–wake and qEEG disturbances with underlying alterations in neurotransmitter systems known to modulate both the sleep–wake architecture and neural fear circuitry.

In another PTSD model, after being exposed to two unavoidable electric foot-shocks in the presence of an object (i.e. a plastic prism), shocked mice displayed sleep fragmentation, the total duration of wakefulness was significantly increased, and REM sleep was significantly decreased, whereas sleep disturbances were prevented by 5-HT reuptake inhibitor paroxetine and NMDA receptor agonist d-cycloserine, which have demonstrated clinical efficacy against PTSD [29, 31]. Thus, this animal model can be used to screen medications for PTSD treatment.

Menopausal transition period

Sleep disturbances are a major complaint of women transitioning to menopause and have a far-reaching impact on the quality of life, mood, productivity, and physical health [80–82]. Approximately 40%–60% of menopausal women generally experience difficulty falling asleep, wake up several times, and wake up early [83–85]. Several rodent models of gonadal hormonal loss have been used to determine how female sex hormones modulate spontaneous (baseline) sleep. Ovariectomy (OVX) is an ideal model to evaluate the specific effects of gonadal hormone deprivation and subsequent exogenous hormone treatments [86]. Compared with intact rats, OVX rats had more NREM sleep and REM sleep, and administration of estradiol decreased spontaneous NREM and REM sleep during the dark phase (Fig. 1b) [87, 88]. However, a drawback of the OVX model in the context of translational studies is that the sudden loss of ovarian steroids is not a characteristic of the vast majority of menopausal women; compounded with this, the post-menopausal ovary continues to release androgens and low levels of other steroids [86].

Daily injection of 4-vinylcyclohexene diepoxide (VCD), a chemical that selectively targets and depletes the non-growing ovarian follicle pool in rodents via atresia, can result in a progressive loss of ovarian follicles. Stromal cells remain intact and continue to produce androgens, thus mimicking the physiological changes to the hormonal milieu that characterize the perimenopausal transition to menopause [89–91]. The VCD model is gaining popularity in the field of menopause. Recently, ICR mice induced by VCD represented REM and NREM sleep decreased, which provides an insight into the opportunity for preventing insomnia in women [92].

Depression

Most depressed people suffer from sleep disturbances, one of the key symptoms of depression. Sleep disturbances in depression include difficulty in falling asleep, frequent awakenings during the night and non-restorative sleep, shortened REM sleep latency, prolonged REM sleep period, enhanced REM sleep density [93, 94]. It is important to note that while insomnia is prevalent in depression, with approximately 75% of patients experiencing difficulties initiating or maintaining sleep, a subset of individuals with depression experience hypersomnia. This condition, characterized by excessive sleepiness or prolonged sleep duration, is particularly associated with the depressive phase of bipolar disorder. This duality of sleep-related symptoms in mood disorders underscores the heterogeneity of depression and the necessity to personalize treatment approaches [95]. Similar sleep disturbances have been reproduced in several rodent models of depression (Fig. 1b).

Olfactory bulbectomy (OBX) rats exhibited a significant increase in REM sleep, administration with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine abolished the OBX-induced increase in REM sleep [96]. Chronic mild stress mice (rearing on a wire net for 3 weeks) showed attenuated NREM sleep, with decreased mean bout duration of NREM sleep and increased episode number of NREM sleep, suggesting sleep fragmentation [97]. Rats exposed to repeated social defeat stress also indicated sleep instability [62], please see the section in ‘Phasic contact’ for the details. The helpless mouse is a genetic model of depression. Compared to non-helpless mice, the helpless mice exhibited more sleep fragmentation, increased REM sleep amounts and decreased latency, thus, this genetic model might be of particular interest for investigating the neurobiological mechanisms and possibly genetic substrates underlying sleep alterations associated with depression [98, 99].

Neurodegenerative diseases

Alzheimer’s disease

More than 60% of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) develop sleep disturbance, such as difficulty falling asleep, repeated nocturnal arousals, early arousals in the morning, and excessive sleepiness during daytime [100–102]. The impaired sleep observed in patients with AD has been linked to AD pathology, which impacts the brain regions responsible for regulating the sleep–wake cycle or circadian rhythm [103].

The increase in wakefulness and decrease in both NREM and REM sleep has been reported in most of the mouse models and is similar to the changes seen in AD patients. Tg2576 mice, a widely used mouse model of AD, model brain amyloid pathology. The increase in electroencephalographic delta power that occurs during NREM sleep after sleep deprivation (SD) was blunted in Tg2576 mice relative to wild type (WT) controls, and the wake-promoting efficacy of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor donepezil was lower in plaque bearing Tg2576 mice than in WT controls [104]. There were more frequent arousals from sleep and fragmented sleep in Tg2576 mice compared to WT mice [105]. REM sleep time/24 h in Tg2576 mice was reduced by 30% (6 months of age) and 50% (12 months of age) relative to age-matched WT mice, and the numbers of pedunculopontine tegmentum choline acetyltransferase-positive neurons were reduced in the Tg2576 mice at 6 and 12 month [106]. The occurrence of both sleep abnormalities and cholinergic deficits in Tg2576 mice provide a uniquely powerful tool for the study of the pathophysiology and treatments of sleep deficits and associated cholinergic abnormalities in AD.

In addition, TgCRND8 mice showed increased wakefulness and reduced NREM sleep during the resting and active phases, and amyloidosis in TgCRND8 mice is associated with sleep–wake cycle dysfunction [107]. 5XFAD mice exhibited shorter sleep bout lengths as compared to controls, the 5XFAD female mice showed less total sleep than WT [108]. There was an increase in wakefulness and a decrease in sleep during the light phase following plaque formation in APP/PS1 mice [109]. These transgenic AD mice may serve as useful models for testing therapeutic strategies to improve sleep consolidation in AD patients.

Parkinson’s disease

Sleep disturbance is a major non-motor complaint of Parkinson’s disease (PD) with extensive impact on patient quality of life. Approximately 40% to 90% PD patients exhibit sleep disturbances, including insomnia, excessive daytime sleepiness, REM sleep behavior disorder, nocturnal motor and nonmotor symptoms and a fragmented sleep–wake behavior [110–113].

Similar sleep disturbances occur in several mouse models of PD. The neurotoxin 6-hydroxy dopamine (6-OHDA), 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) or rotenone produces specific dopaminergic cell degeneration and symptoms reminiscent of PD in rodent animals [114–116]. 6-OHDA-treated rats spent more total time in the waking state and less time in the NREM sleep state during the light phase, compared to normal, and also had more REM epochs with muscle activity than control rats (Fig. 1b) [117]. MPTP-treated mice display changes in the sleep–wake architecture, with more consolidated vigilance states, a reduction of NREM sleep amount and an increase of REM sleep amount [118, 119]. Rotenone, as a pesticide, increases NREM and REM sleep in male Sprague-Dawley rats during the dark period, but decreases NREM sleep and enhances wakefulness during the light period [120, 121]. These toxin-based animal models are suitable for the study of sleep disturbances and therapies in PD.

A large number of transgenic mouse models of PD have been developed [122]. In the mouse, overexpression of human α-synuclein driven by the Thy-1 promoter (Thy1-αSyn) leads to a progressive disruption of the nigrostriatal pathway, resulting in a 40% decrease of striatal dopamine [123]. Thy1-aSyn mice increased NREM sleep during the light phase, increased active wake during the dark phase, and decreased REM sleep over a 24-h period, as well as a shift in the density of their EEG power spectra toward lower frequencies with a significant decrease in gamma power during wakefulness [124]. Thus, this model provides a novel platform to assess the mechanisms and therapeutic strategies for sleep dysfunction in PD.

A novel α-synucleinopathy-based REM sleep behavior disorders (RBD) mouse model was established. This model may further progress to exhibit parkinsonian locomotor dysfunction, depression-like disorder, olfactory dysfunction, and gastrointestinal dysmotility. Corresponding to that, α-synuclein pathology was determined in the substantia nigra pars compacta, olfactory bulb, enteral neuroplexus and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve, which could underlie the Parkinsonian manifestations in mice [125]. However, sleep–wake profile in this α-synucleinopathy-based RBD mouse model still needs further investigation.

Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy is a sleep disorder that makes people very drowsy during the day [126]. In individuals with narcolepsy, the hallmark symptoms encompass excessive daytime sleepiness, disrupted nocturnal sleep, and the erratic distribution of REM sleep episodes throughout the 24-h cycle, which can lead to sleep fragmentation at night and intrusion into periods of wakefulness during the day, manifesting as sleep attacks and cataplexy [127, 128]. The pathophysiology of narcolepsy, particularly narcolepsy with cataplexy, is chiefly associated with the dysregulation of the hypocretin (orexin) system, often due to the autoimmune-mediated loss of hypocretin-producing neurons in the lateral hypothalamus [129].

Nowadays, conditional rodent models of narcolepsy have been developed that can better mimic narcolepsy symptoms based on conditional ablation of melanin-concentrating hormone and hypocretin neurons, such as OX-tTA; Pmch-tTA; TetO-DTA mice, which increased wake and cataplexy with NREM and REM sleep decreased [130]. As new brain regions of potential therapeutic targets for narcolepsy have been found [131], these models could be good for testing new drugs for the co-morbidity of insomnia and narcolepsy.

Pharmacological intervention related models

Adenosine and caffeine

Adenosine has previously been proposed as an endogenous sleep substance. Administration of adenosine and stable adenosine analogs induce sleep in experimental animals, and adenosine A1 receptor (A1R) and A2A receptor (A2AR) subtypes are involved in sleep induction [132, 133].

Caffeine, the most commonly used psychoactive stimulant, is an antagonist of the adenosine A1 and A2A receptors. The detrimental effects of caffeine on sleep quality in humans are well documented [134, 135]. Nocturnal use of caffeine leads to insomnia symptoms, including decreased total sleep time, difficulty falling asleep, increased nocturnal awakenings, and daytime sleepiness [136, 137]. Polysomnographic sleep abnormalities seen after caffeine consumption have included increased sleep latency, decreased NREM sleep, sleep fragmentation with brief arousals from sleep, and decreased sleep duration [138, 139]. In rats, caffeine dose-dependently disrupted sleep: it prolonged sleep onset latency, increased wakefulness, decreased NREM sleep time and NREM bout duration, and decreased delta activity in NREM sleep [140, 141]. Caffeine increased wakefulness in WT mice in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1c), and adenosine A2A, but not A1, receptors mediate the arousal effect of caffeine [142, 143]. Furthermore, the caffeine-induced insomnia could be attenuated by the hypnotic zolpidem and trazodone which have different mechanisms of action [140]. Therefore, administration of caffeine or adenosine A2A antagonists may provide a quick and simple way to induce insomnia in rodents, and this model may represent a suitable tool for drug screening.

Histamine

Histaminergic neurons are located in the tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN) of the posterior hypothalamus, which plays an important role in arousal and maintenance of wakefulness [144, 145]. Histamine neurons cease firing immediately preceding sleep and resume immediately following awakening [146]. The central release of histamine exhibits circadian variation associated with wakefulness [147]. Acute optogenetic silencing and chemogenetic inhibition of histamine neurons during wakefulness induce NREM sleep, whereas acute chemogenetic stimulation of histamine neurons produces increased movement and arousal [148–150]. Histamine administration to cats or rats induces an increase in wakefulness and a decrease in NREM sleep [151, 152].

A growing body of evidence has implicated histamine increases wakefulness via H1 receptors (H1R). Microinjection of H1R agonist 2-thiazolylethylamine caused a long-lasting suppression of cortical slow activity and an increase in wakefulness, and the effects were attenuated by systemic pretreatment with H1R antagonist mepyramine [152]. H1R antagonists doxepin and diphenhydramine increased NREM sleep in WT mice not in the H1R KO mice [153]. H3R is a presynaptic autoreceptor that provides negative feedback to constrain histamine synthesis and release. H3R antagonist promoted wakefulness and increased histamine release, whereas H3R agonist enhanced cortical slow activity and increased slow wave sleep [144, 154]. Blockade of the histamine H3R is proposed to induce wakefulness by regulating the release of various wake-related transmitters, not only histamine [155]. H3R antagonist/inverse agonists enhance cortical activation and waking and, like modafinil, but unlike amphetamine and caffeine, their waking effects were not accompanied by behavioral excitation and sleep rebound [156, 157]. Thus, manipulation of central histaminergic activity by activating H1R or antagonizing H3R may yield simple and consistent models of insomnia in rodents.

Dopamine and psychostimulants

Dopamine (DA), a neurotransmitter from the catecholamine family, is critically involved in sleep–wake regulation [158, 159]. Using a dopamine sensor and simultaneous polysomnographic recordings, a recent study in our laboratory demonstrated that striatal dopamine levels were highest during wakefulness and dopamine fluctuations correlated with spontaneous sleep–wake transitions in mice [160]. Optogenetic activation and chemogenetic stimulation of dopamine D1 receptor (D1R)-expressing neurons in the nucleus accumbens induce and maintain wakefulness [161]. Genetic deletion of D2R significantly decreases wakefulness in mice [162]. Moreover, patients with Parkinson’s disease, who exhibit dopaminergic lesions in the striatum and nigrostriatal, suffer from severe sleep disorders including insomnia, sleep fragmentation, excessive daytime sleepiness, and REM sleep behavior disorders [110–113].

Dopamine D1 and D2 receptors play a key role in the wake-promoting effect of dopamine. In rodents, systemic administration of the selective D1 receptor agonist SKF 38393 induces behavioral arousal together with an increase in wakefulness and a reduction of NREM sleep [163, 164]. On the other hand, injection of a D2 receptor agonist gives rise to biphasic effects, such that low doses reduce wakefulness and augment NREM and REM sleep whereas large doses induce the opposite effects [164, 165].

Psychostimulant amphetamine exerts potent wake-promoting effects by inhibiting uptake and causing the release of dopamine from presynaptic terminals [166]. Both acute and chronic amphetamine administration prolongs the latency of NREM sleep and REM sleep in Wistar rats [167]. Amphetamine significantly increased wakefulness and decreased both NREM and REM sleep in narcoleptic and WT mice [164]. However, animal model of insomnia induced by psychostimulants may be limited due to their potential for abuse and side effects such as addiction.

Another psychostimulant modafinil is also a wake-promoting drug with low abuse potential used in the treatment of sleep-related disorders, such as narcolepsy, shift-work sleep disorder, and obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome [168, 169]. Studies showed that modafinil selectively blocked dopamine transporters and increased the extracellular concentration of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens to promote wakefulness [170, 171]. In mice, intraperitoneal modafinil increased wakefulness significantly in a dose-dependent manner, and D1R and D2R mediate the wake-promoting of modafinil [162]. Modafinil and armodafinil (the R-enantiomer of racemic modafinil) significantly and dose-dependently increased wakefulness, wake episode duration and latency to the onset of sleep in rats [172, 173]. Therefore, modafinil and armodafinil with low abuse potential may be a good approach for generating animal models of insomnia.

Morphine

Morphine is the most potent and widely prescribed treatment for pain. Unfortunately, morphine has numerous side effects including sleep disruption [174]. In healthy human volunteers, morphine (intravenous injections of 0.1 mg/kg) altered sleep architecture by reducing slow-wave sleep (NREM stages 3) and REM sleep, and by increasing NREM stage 2 sleep [175, 176]. In the rodent animal, acute administration of morphine (subcutaneously injected into rats at a dose of 0.3, 1, or 3 mg/kg) increased wakefulness and decreased NREM and REM sleep in a dose-dependent manner, and the wakefulness-promoting effect may be mediated by inhibiting sleep-promoting neurons in the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO) or decreasing GABAergic transmission in the oral pontine reticular formation by affecting μ-opioid receptors [177, 178]. Acute withdrawal from chronic morphine treatment resulted in a significant decrease in NREM sleep, REM sleep, and total sleep time. Meanwhile, the sleep latency was significantly longer [179].

In addition to morphine, other opioid μ receptor agonists used to treat pain also induce sleep disturbances. Methadone, a long-acting μ-opioid agonist, compared with healthy controls, early methadone treatment patients had lower sleep efficiency, shorter total sleep time, more awakenings and shorter slow wave sleep [180]. In rats and cats, infusion of μ receptor agonist DAMGO into the VLPO region or the medial pontine reticular formation increased wakefulness in a dose-dependent manner, and these effects were blocked by pre-injection of the μ receptor antagonists [181, 182]. Buprenorphine, a partial μ opioid receptor agonist, caused a significant increase in wakefulness and a decrease in both NREM and REM sleep in rats, these disruptions in sleep architecture were mitigated by coadministration of the non-benzodiazepine sedative/hypnotic eszopiclone [183].

Ethanol exposure and withdrawal

Ethanol is a widely abused psychoactive substance, known to have significant acute and chronic effects on the body. Numerous clinical studies have revealed that acute alcohol consumption profoundly affects sleep patterns [184, 185], while abrupt cessation in alcoholics leads to severe disruptions in sleep architecture and sleep quality [186, 187]. In the animal experiments, ethanol administration increased NREM sleep and reduced wakefulness in a dose-dependent manner, and REM sleep was decreased at a high dose of ethanol [188]. During ethanol withdrawal, there is an increase in wakefulness, a decrease in sleep duration, alterations in REM sleep, and changes in the EEG power spectrum [189–191]. Ethanol injection remarkably shortens the latency to NREM sleep and prolonged REM sleep latency, leading to an increase in the number of NREM sleep episodes with long durations, consistent with decreased wakefulness. Notably, there were no differences in the total number of wakefulness, NREM sleep and REM sleep episodes, nor in transition numbers, following ethanol administration [188]. However, after ethanol withdrawal, the latency to NREM sleep increased, accompanied by a decrease in mean duration and an increase in the number of NREM and REM sleep episodes, indicating fragmented sleep [190]. Ethanol withdrawal induced a decrease in delta and theta activity during NREM sleep [189], along with a remarkable reduction in the EEG power spectrum of delta, theta and beta activity, suggesting disruptions in sleep quality [192].

Hypocretin

Hypocretin, also known as orexin, is a neuropeptide that plays a crucial role in regulating wakefulnes. Dysregulation of the hypocretin system has been implicated in various sleep disorders, including insomnia [193]. Therefore, manipulating the hypocretin system in rodents has emerged. In this model, researchers typically use pharmacological agents that modulate the activity of hypocretin receptors or the synthesis and release of hypocretin. For example, Suvorexant, the hypocretin receptor antagonists block the binding of hypocretin to its receptors, thereby reducing wakefulness and promoting sleep in rodents as an insomnia medication medicine to treat sleep disorders in human [194]. Conversely, hypocretin agonists have the opposite effect and can induce insomnia.

Circadian clock dependent models

Circadian rhythm controls the timing of sleep across the light-dark cycle. Survey studies suggest that 10% of adult and 16% of adolescent population suffer from circadian rhythm sleep disorders (CRSD) [195, 196]. CRSD are a distinct class of sleep disorders characterized by a mismatch between the desired timing of sleep and the ability to fall asleep and remain asleep, and are associated with difficulty falling asleep, problems awakening on time (e.g., to meet work or school obligations), and daytime sleepiness [197, 198].

Light intensity and photoperiod

Light is the most potent cue in the initiation of circadian rhythms. Red light at intensities above 10 lx exerted potent sleep-inducing effects and changed the sleep architecture in terms of the duration and number of sleep episodes, the stage transition, and the EEG power density; however, red light at or below 10 lx did not affect sleep–wake behavior during the dark phase in mice [199]. Exposure to light has demonstrated considerable efficacy as a therapeutic intervention for a range of sleep disorders and disruptions in circadian rhythms. For instance, light therapy has been employed successfully to treat Delayed Sleep Phase Disorder (DSPD), which is characterized by a shifted sleep–wake cycle that leads to difficulties in falling asleep and waking up at conventional times. Specifically, exposure to bright light during the morning hours has been proven to realign the circadian phase, thereby reducing the time it takes to fall asleep (sleep onset latency) and enhancing overall sleep quality in individuals with DSPD [200].

The photoperiod has been shown to influence sleep regulation in rodents. Rats were submitted for 14 days to light–dark 12 h:12 h or light–dark 16 h:8 h, total sleep time and NREM sleep per 24 h and during extended light hours were higher after LD 16 h:8 h photoperiod compared with LD 12 h:12 h at baseline, and the sleep rebound and sleep intensity related to sleep deprivation recovery after LD 16 h:8 h photoperiod were lower for at least 24 h. This may represent a potential model of sleep extension in the laboratory animals [201]. Circadian rhythm disruption was caused by a short light-dark cycle regime (LD 11 h:11 h, LD 10.5 h:10.5 h, and LD 10 h:10 h) in mice, shortening of photoperiod caused a significant increase of slow wave activity during NREM sleep, suggesting an elevation of sleep pressure under such conditions [202].

Clock gene mutation

A specific set of genes is responsible for the control of the circadian system including Clock, Bmal1, Period1, Period2, Cryptochrome1 (cry1), and Cryptochrome2 (cry2). Clock and Bmal1 are components of a positive feedback loop that dimerizes with each other and subsequently activates the transcription of Period and Cryptochrome. Period and Cryptochrome then dimerize and act on the Clock/Bmal1 heterodimer to repress the transcription of Period and Cryptochrome [203]. The use of animal genetic models has been instrumental in understanding how the molecular components of the circadian clock affect sleep–wake behavior.

Genetic deletion of the circadian transcription factor Bmal1 in mice completely ablates circadian clock function, these mice showed increases in total sleep time, sleep fragmentation and EEG delta power under baseline conditions, and an attenuated compensatory response to acute sleep deprivation [204, 205]. Bmal1 knockdown caused an increase in sleep and a decrease in time spent awake during the dark phase in mice [206].

The cryptochrome 1 and 2 genes (cry1 and cry2) are necessary for the generation of circadian rhythms, as mice lacking both of these genes (cry1,2-/-) lack circadian rhythms. Under baseline, constant darkness, and sleep deprivation conditions, cry1,2-/- mice exhibit increases in NREM sleep duration, NREM sleep consolidation, and EEG delta power during NREM sleep. This unexpected phenotype was associated with elevated brain mRNA levels of period 1 and 2 (per1,2), which are known to be transcriptionally inhibited by cry1,2 [207]. Thus, cry1,2-/- mice appear to be a suitable model for the study of sleep regulation in the absence of an intact circadian clock.

Period circadian clock (Per) genes Per1 and Per2 have essential roles in circadian oscillation. There was no significant difference in the total daily amount of vigilance states between the mPer1, mPer2-mutant, and WT mice during the 24-h baseline period. The main difference between the genotypes occurs in the distribution of sleep, with mPer1 mutants sleeping more than the WT mice at the dark-light transition. Whereas mPer2 mutants had less NREM sleep and REM sleep than WT in the last 3 h before dark onset, and the phase advance of motor activity onset [208, 209]. Similarly, a mutation affecting the phosphorylation site of the human Per2 gene in certain cases of familial advanced sleep-phase syndrome (FASPS) leads to an earlier waking of these subjects [210]. Therefore, mice with mPer2 mutations are suitable for the study of advanced sleep phase syndrome (Fig. 1d).

Mutation in the human TIMELESS (hTIM) gene that causes familial advanced sleep phase (FASP). Tim CRISPR mutant mice exhibit phase advance of wakefulness and sleep at the transition from light to dark and from dark to light was ∼30 min, under light–dark (LD) 12 h:12 h, overall sleep duration, sleep bout length and number, and total NREM and REM sleep percentages were preserved, indicating that the advanced phase is gated by circadian parameters and does not affect sleep architecture [211].

Delayed or advanced phase of sleep

DSPS is very often seen among patients with sleep–wake rhythm disorders. Humans with the 3111 C allele of the human Clock gene tend to demonstrate a higher evening preference [212]. Housed under LD or constant dark (DD) conditions, both WT and Clock mutant mice did not show a phase-delay in the locomotor activity measured, whereas constant light (LL) housing significantly caused a delayed onset of locomotor activity, resulting in evening preference and/or DSPS. Thus, Clock mutant mice can function as an adequate animal model for the study of human DSPS [213].

Genetic manipulation models

Several studies reported that chemogenetic activation of specific neurons in some brain regions induced longterm wakefulness in rodents, such as the paraventricular thalamus (PVT), the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH), the supramammillary region (SuM), and so on. Ren et al. found that PVT glutamatergic neurons exhibit high activity during wakefulness. Suppression of PVT neuronal activity caused a reduction in wakefulness, whereas activation of PVT neurons induced a transition from sleep to wakefulness [214]. PVH glutamatergic neurons are most active during wakefulness. Chemogenetic activation of PVH glutamatergic neurons induced wakefulness for 9 h [215]. Glutamatergic neurons of the SuM produce sustained behavioral and EEG arousal when chemogenetically activated (Fig. 1e) [216, 217]. Moreover, optogenetics, chemogenetic inhibition, and neural-type-specific ablation may also be useful for building up specific insomnia models [218–220].

Discussion

Integrating rodent models into drug delivery research offers a multifaceted approach with distinct advantages and limitations, particularly concerning insomnia-related studies. Stress-related models, often employed to simulate insomnia-like conditions, provide valuable insights into the impact of stress on drug delivery efficacy in insomnia. However, the translational relevance of these findings may be limited by species-specific differences in sleep architecture and stress responses. Disease-related models, including PTSD and neurodegenerative disease models for insomnia, present opportunities for assessing targeted drug delivery strategies in insomnia. Nevertheless, accurately replicating the complexity of human sleep disorders in rodent models poses challenges, potentially hindering the applicability of results to clinical settings. Pharmacological intervention-related models facilitate the investigation of drug metabolism and bioavailability in the context of insomnia, aiding in the development of optimized treatment strategies. Yet, disparities in drug responses between rodents and humans may undermine the predictive utility of such models. Circadian clock-related models, essential for exploring chronotherapy and circadian rhythm disruptions in insomnia, contribute valuable insights into drug delivery kinetics and dosing schedules. However, interspecies variations in circadian regulation and the complexities of environmental control may introduce variability into experimental outcomes.

Although genetic manipulation models may not encapsulate the full spectrum of behavioral, physiological, and psychological characteristics of human insomnia, they nonetheless offer substantial benefits. These models allow for precise targeting of specific brain nuclei, thus facilitating the identification of genes that may ameliorate insomnia symptoms for future clinical and pharmacological research. For instance, researchers can initially determine the role of increased activity in a particular brain nucleus during wakefulness using techniques such as histochemistry, electrophysiological recording of neural activity, or calcium imaging. Subsequent targeted activation or inhibition of specific neuronal cell types or receptors through genetic manipulation can shed light on their functions in promoting wakefulness, thereby modelling certain aspects of insomnia. This is exemplified by the activation of glutamatergic neurons in the supramammillary region [216, 217] or the corticotropin-releasing factor neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus [221]. Similarly, inhibiting neurons that normally promote sleep, like adenosine A2A receptor neurons in the striatum [142, 222], can induce symptoms akin to insomnia. Moreover, genetic manipulation models are capable of simulating various forms of insomnia with remarkable temporal and spatial precision. A notable example is the optogenetic activation of the glutamatergic neural circuit in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a region implicated in processing the affective component of pain, which leads to an immediate increase in rodent wakefulness [160], thus mimicking the sleep disturbances associated with neuropathic pain [40]. Additionally, advanced genetic techniques such as optogenetics or chemogenetics hold the potential to enhance our understanding of sleep–wake regulation when used in conjunction with other insomnia models, like those induced by stress or pharmacological agents. By integrating various methodologies, we can achieve a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of insomnia, which can significantly advance the screening and development of new therapeutic drugs.

By utilizing these rodent insomnia models, researchers can gain insights into the various factors that contribute to insomnia. For example, human fMRI studies found that the hyperactivity of the amygdala [223], which may been induced by insufficient suppression of cortex or brainstem, as a cause of insomnia. Beside, by comparing the stress-related insomnia model with the non-stress model (novel object) by recording the activity of brain regions, it is possible to find out distinct intrinsically driven arousal nuclei and externally stimulus-driven arousal nuclei. Thus, it’s possible to address the question of the active and passive nature of awakening.

In summary, integrating findings from different insomnia-related rodent models can enhance our understanding of drug mechanisms in the insomnia and improve the translatability of preclinical research to clinical applications in insomnia treatments.

Conclusions

Rodent models have played a crucial role in the understanding of the pathophysiology of insomnia. These models are cost-effective, allow for genetic manipulation, have well-established protocols for many conditions associated with insomnia in humans, and have excellent reproducibility properties. In this review, the potential and existing rodent models of insomnia that are currently available are summarized. Some animal models share basic features similar to human insomnia, however, differences with human insomnia also limit the transfer to humans. Thus, more work is needed to characterize and optimize these models and further insights into the molecular biology of the mechanisms that contribute to insomnia have led to the discovery and testing of many novel therapeutic agents in rodents.

Acknowledgements

This study was partly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82020108014 and 32070984 to ZLH; 82071491 and 31871072 to WMQ), the STI2030-Major Project (2021ZD0203400 to ZLH), Program for Shanghai Outstanding Academic Leaders (to ZLH), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (2018SHZDZX01 to ZLH), Zhangjiang Lab, and Shanghai Center for Brain Science and Brain-Inspired Technology, Lingang Laboratory & National Key Laboratory of Human Factors Engineering Joint Grant (LG-TKN-202203-01).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Ze-ka Chen, Yuan-yuan Liu

Contributor Information

Chun-feng Liu, Email: liuchunfeng@suda.edu.cn.

Wei-min Qu, Email: quweimin@fudan.edu.cn.

Zhi-li Huang, Email: huangzl@fudan.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Bao WW, Jiang S, Qu WM, Li WX, Miao CH, Huang ZL. Understanding the neural mechanisms of general anesthesia from interaction with sleep-wake state: a decade of discovery. Pharmacol Rev. 2023;75:532–53. 10.1124/pharmrev.122.000717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang YQ, Liu WY, Li L, Qu WM, Huang ZL. Neural circuitry underlying rem sleep: a review of the literature and current concepts. Prog Neurobiol. 2021;204:102106. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2021.102106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu D, Dan Y. A motor theory of sleep-wake control: arousal-action circuit. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2019;42:27–46. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-080317-061813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhaskar S, Hemavathy D, Prasad S. Prevalence of chronic insomnia in adult patients and its correlation with medical comorbidities. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2016;5:780–4. 10.4103/2249-4863.201153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schutte-Rodin S, Broch L, Buysse D, Dorsey C, Sateia M. Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:487–504. 10.5664/jcsm.27286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benca RM. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic insomnia: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:332–43. 10.1176/appi.ps.56.3.332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Revel FG, Gottowik J, Gatti S, Wettstein JG, Moreau JL. Rodent models of insomnia: a review of experimental procedures that induce sleep disturbances. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:874–99. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilt TJ, MacDonald R, Brasure M, Olson CM, Carlyle M, Fuchs E, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of insomnia disorder: An evidence report for a clinical practice guideline by the american college of physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:103–12. 10.7326/M15-1781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costentin J. [treatment of insomnia. Pharmacological approaches and their limitations]. Bull Acad Natl Med. 2011;195:1583–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunja N. The clinical and forensic toxicology of Z-drugs. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9:155–62. 10.1007/s13181-013-0292-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morin AK. Strategies for treating chronic insomnia. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12:S230–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glass J, Lanctot KL, Herrmann N, Sproule BA, Busto UE. Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: Meta-analysis of risks and benefits. BMJ. 2005;331:1169. 10.1136/bmj.38623.768588.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spadoni G, Bedini A, Rivara S, Mor M. Melatonin receptor agonists: New options for insomnia and depression treatment. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2011;17:733–41. 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00197.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeung WF, Chung KF, Yung KP, Ng TH. Doxepin for insomnia: A systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;19:75–83. 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kay-Stacey M, Attarian H. Advances in the management of chronic insomnia. BMJ. 2016;354:i2123. 10.1136/bmj.i2123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veasey SC, Valladares O, Fenik P, Kapfhamer D, Sanford L, Benington J, et al. An automated system for recording and analysis of sleep in mice. Sleep. 2000;23:1025–40. 10.1093/sleep/23.8.1c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paterson LM, Nutt DJ, Wilson SJ. Sleep and its disorders in translational medicine. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:1226–34. 10.1177/0269881111400643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rea MS, Bierman A, Figueiro MG, Bullough JD. A new approach to understanding the impact of circadian disruption on human health. J Circadian Rhythms. 2008;6:7. 10.1186/1740-3391-6-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wisor JP, Jiang P, Striz M, O’Hara BF. Effects of ramelteon and triazolam in a mouse genetic model of early morning awakenings. Brain Res. 2009;1296:46–55. 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.07.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wafford KA, Ebert B. Emerging anti-insomnia drugs: Tackling sleeplessness and the quality of wake time. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:530–40. 10.1038/nrd2464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee DH, Cho CH, Han C, Bok KN, Moon JH, Lee E, et al. Sleep irregularity in the previous week influences the first-night effect in polysomnographic studies. Psychiatry Investig. 2016;13:203–9. 10.4306/pi.2016.13.2.203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toussaint M, Luthringer R, Schaltenbrand N, Carelli G, Lainey E, Jacqmin A, et al. First-night effect in normal subjects and psychiatric inpatients. Sleep. 1995;18:463–9. 10.1093/sleep/18.6.463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang X, Xiao J, Parris BS, Fang J, Sanford LD. Differential effects of two types of environmental novelty on activity and sleep in BALB/cJ and C57BL/6J mice. Physiol Behav. 2005;85:419–29. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu Q, Xu XH, Qu WM, Lazarus M, Urade Y, Huang ZL. A mouse model mimicking human first night effect for the evaluation of hypnotics. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2014;116:129–36. 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKenna JT, Gamble MC, Anderson-Chernishof MB, Shah SR, McCoy JG, Strecker RE. A rodent cage change insomnia model disrupts memory consolidation. J Sleep Res. 2019;28:e12792. 10.1111/jsr.12792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanford LD, Yang L, Wellman LL, Liu X, Tang X. Differential effects of controllable and uncontrollable footshock stress on sleep in mice. Sleep. 2010;33:621–30. 10.1093/sleep/33.5.621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wellman LL, Yang L, Sanford LD. Effects of corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) on sleep and temperature following predictable controllable and uncontrollable stress in mice. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:258. 10.3389/fnins.2015.00258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Malley MW, Fishman RL, Ciraulo DA, Datta S. Effect of five-consecutive-day exposure to an anxiogenic stressor on sleep-wake activity in rats. Front Neurol. 2013;4:15. 10.3389/fneur.2013.00015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Philbert J, Beeske S, Belzung C, Griebel G. The CRF(1) receptor antagonist SSR125543 prevents stress-induced long-lasting sleep disturbances in a mouse model of PTSD: Comparison with paroxetine and d-cycloserine. Behav Brain Res. 2015;279:41–6. 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Machida M, Wellman LL, Fitzpatrick Bs ME, Hallum Bs O, Sutton Bs AM, Lonart G, et al. Effects of optogenetic inhibition of BLA on sleep brief optogenetic inhibition of the basolateral amygdala in mice alters effects of stressful experiences on rapid eye movement sleep. Sleep. 2017;40:zsx020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Philbert J, Pichat P, Beeske S, Decobert M, Belzung C, Griebel G. Acute inescapable stress exposure induces long-term sleep disturbances and avoidance behavior: A mouse model of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Behav Brain Res. 2011;221:149–54. 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.02.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu B, Cui SY, Zhang XQ, Cui XY, Li SJ, Sheng ZF, et al. Mechanisms underlying footshock and psychological stress-induced abrupt awakening from posttraumatic “nightmares”. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;19:pyv113. 10.1093/ijnp/pyv113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oishi K, Nishio N, Konishi K, Shimokawa M, Okuda T, Kuriyama T, et al. Differential effects of physical and psychological stressors on immune functions of rats. Stress. 2003;6:33–40. 10.1080/1025389031000101330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Endo Y, Shiraki K. Behavior and body temperature in rats following chronic foot shock or psychological stress exposure. Physiol Behav. 2000;71:263–8. 10.1016/S0031-9384(00)00339-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cui R, Suemaru K, Li B, Araki H. The effects of atropine on changes in the sleep patterns induced by psychological stress in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;579:153–9. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.09.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cui R, Li B, Suemaru K, Araki H. Differential effects of psychological and physical stress on the sleep pattern in rats. Acta Med Okayama. 2007;61:319–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cui R, Li B, Suemaru K, Araki H. The effect of baclofen on alterations in the sleep patterns induced by different stressors in rats. J Pharm Sci. 2009;109:518–24. 10.1254/jphs.08068FP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roth T, van Seventer R, Murphy TK. The effect of pregabalin on pain-related sleep interference in diabetic peripheral neuropathy or postherpetic neuralgia: A review of nine clinical trials. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:2411–9. 10.1185/03007995.2010.516142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keilani M, Crevenna R, Dorner T. Sleep quality in subjects suffering from chronic pain. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2018;130:31–6. 10.1007/s00508-017-1256-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li YD, Luo YJ, Su WK, Ge J, Crowther A, Chen ZK, et al. Anterior cingulate cortex projections to the dorsal medial striatum underlie insomnia associated with chronic pain. Neuron. 2024:S0896-6273(24)00040-0. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Tokunaga S, Takeda Y, Shinomiya K, Yamamo’ro W, Utsu Y, Toide K, et al. Changes of sleep patterns in rats with chronic constriction injury under aversive conditions. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30:2088–90. 10.1248/bpb.30.2088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]