Abstract

Understanding how land use types embedded in agricultural landscapes support forest biodiversity is critical, especially during this period of continuing fragmentation and habitat losses in natural ecosystems. Here, we explored the floristic species composition with respect to land use types in the agroecosystem of west Oromia, Ethiopia. For this, a systematic sampling method was employed to collect floristic data from 122 main quadrats and 610 sub-quadrats, following transects laid out with a 1500-m interval. The main quadrats were arranged on transects with an 800-m interval to assess woody species, and five sub-quadrats (i.e., four at the corners and one at the center) were taken within each main plot to assess herbaceous plants. Accordingly, the floristics were assessed with respect to the identified five land use types, including crop land, forest, grazing land, home gardens, and riverine. We used a one-way ANOVA to test the difference in species diversity among the land use types. Adonis 2 and indval functions were used to describe the species composition and indicator species in relation to the land use types. Moreover, NMDS was applied to visualize the associations of the species composition with environmental variables in ordination space. A total of 285 plant species belonging to 220 genera and 89 families were recorded. Our results showed significant differences in species diversity, dissimilarity in species composition, and species indicator values among the land use types. These results indicate that the potentiality of the land use types in supporting plant diversity is significantly different; for example, species diversity and abundances were higher in grazing lands and home gardens when compared with other land use types. Overall, our findings suggest that conservation strategies in agricultural landscapes should take into account the differences in capacity for supporting biodiversity among land use types when planning.

Keywords: Dry afromontane, Degradation, Matrix land, Refugia, Species richness, Vegetation

1. Introduction

Plant biodiversity has faced a serious degradation problem because of the declining extent of vegetation cover and its qualities from time to time [[1], [2], [3]]. The decline of vegetation in extent and quality could enhance the increasing loss of suitable habitats that can support biological diversities in their natural ecosystem settings [[4], [5], [6]]. Deforestation is the cause of the loss of suitable habitats that can support a wide range of different groups of organisms in the vegetation of natural and semi-natural ecosystems [[7], [8], [9]].

Agricultural land expansion is the main driving factor for the destruction of vegetation and, hence, the loss of habitats for plant biodiversity [[10], [11], [12]]. The agricultural land expansion facilitated through deforestation could lead to the formation of variegated landscapes with mosaics of semi-natural vegetation intermixed with agricultural farm lands [[13], [14], [15], [16]]. This gradual vegetation degradation could result in the formation of semi-natural habitat forms identified as crop land, fragmented forest patches, grazing land, home gardens, and riverine/stream habitats, which are in general known as land use types.

This implies that vegetation studies can be conducted in such landscapes with fragmented forest patches intermixed with other land use forms [17,18]. For example, the diversity of trees and shrubs in fragmented patch forests distributed in agricultural landscapes may show a variation in abundance and richness, as explained in the study [19]. Similarly, plant species that may be absent in the surrounding intact forest could be abundant in nearby agricultural matrix land that is intermixed with mosaics of various fragmented forest patches [20].

Similarly, the strips of riverine vegetation and trees found scattered in farm lands are explained as good indicative remnant marks in agricultural landscapes [21,22]. Patches of shrubs found scattered on the margins of farm lands can also be considered part of vegetation and contribute to the study of the diversity of plant species in agricultural landscapes [20,23]. This indicates that studying plant diversity in agricultural landscapes can contribute to generating a sort of knowledge that attributes biodiversity conservation aspects to such landscapes [[24], [25], [26]].

Similarly, deforestation practiced for a long period could bring considerable changes to the extent of vegetation cover and its qualities at different corners of Ethiopia [27]. Increasing farmer demand for agricultural land, settlements, and intensive state farm expansions practiced in the country were the main causes for the destruction of vegetation cover in wide areas of the country [[28], [29], [30]]. Most previous studies done on vegetation in Ethiopia focused on dense forests and explained the status and changes brought on them due to impacts from anthropogenic pressure [[31], [32], [33]]. The studies could also explain gradual changes that could bring forested areas to fragmented patches intermixed with different land use types that can be explained as agricultural landscapes.

So, conducting vegetation studies in agricultural landscapes is paramount to understanding the diversity of plant species among different land use types. Furthermore, having an understanding of plant species diversity and richness in various land use variables can initiate insights on biodiversity conservation for potential management plans. In west Oromia, where agricultural activities have been widely practiced and could bring considered changes to the land feature for long periods, we intended to conduct a vegetation study in the agricultural landscape, comprising various land use types such as crop land, forest, grazing land, home gardens, and riverine. Here, we hypothesized that there were significant differences in plant species composition and species diversity among different land use types in agricultural landscapes in west Oromia. To test the hypothesis, we analyzed sample vegetation data collected within each of the five land use types in Gudeya Bila District.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

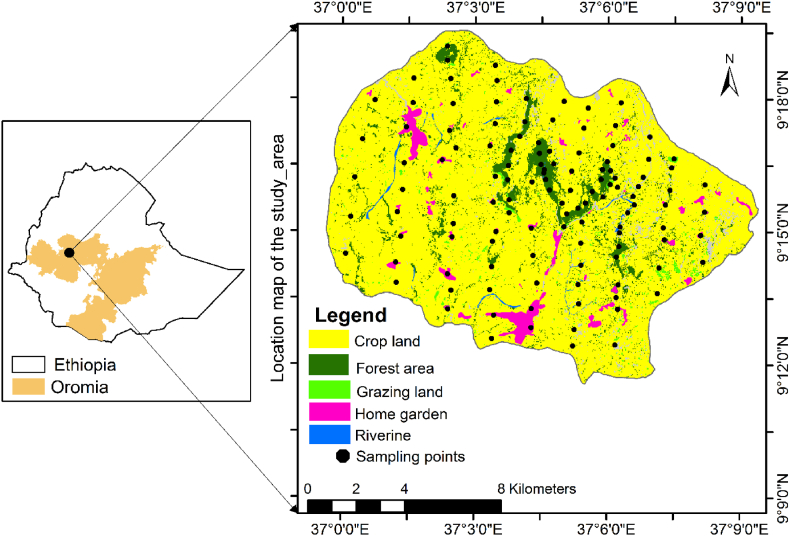

The study was conducted in Gudeya Bila District, which is situated in west Oromia Region, Ethiopia, between the geographical coordinates of 9o11′33″–9o19′40″ N and 37o0′05″–37o9′24″ E (Fig. 1). The topography of the study area is characterized by a flat land platform, undulating ups and bottoms, rocky hills, and belts of escarpments with steady slopes directing towards the Gibe basin. The study area extends within the altitudinal range of 1970–2899 m.a.s.l. The main soil types in the study area are nitosols and vertisols [34]. The area receives rainfall in a unimodal pattern [35], where the annual average ranges between 1400 and 2000 mm [36]. The vegetation types of the study area belong to the Combretum-Terminalia woodland and Dry evergreen afromontane forest and grassland complex [37]. The agricultural landscape of the study area is heterogeneous and composed of fragmented forest patches, crop land, grassland, grazing land, shrub lands and built-up areas.

Fig. 1.

The map of the study area shown in relation to the Oromia region and Ethiopia.

2.2. Study design

Taking into account our previous knowledge of vegetation fragmentation and ecological degradation around the study area, we selected agricultural landscape to study plant species diversity in different land use types. Firstly, we observed the satellite images in Google Earth to identify the landscape that encompasses different land use structures such as crop land, forest patches grazing land, riverine area, and home garden (Fig. 1). The total area of the study landscape is 164.3787 km2. Secondly, we laid out parallel transects with a 1500 m interval in the study landscape. On each transect, quadrats of different sizes were arranged with an 800 m interval, and the coordinates of each plot were recorded with a hand-held GPS. Accordingly, to assess woody species, 50 m × 50 m main quadrats were used for crop land, grazing land, and home gardens; for forest and riverine, 20 m × 20 m and 10 m × 50 m were used, respectively. Similarly, five 2 m × 2 m smaller quadrats laid out within the main quadrats (four at the corners and one at the center) were used to assess the data of herbaceous plants. In total, 122 main quadrats and 610 sub-quadrats were used to collect floristic data.

2.3. Data collection

From each main quadrat and subquadrat, trees, shrubs, and herbaceous floristic species were assessed, and the number of stems of shrubs and trees was recorded for the land use types encountered on transects. Here, five land use types, such as forest, riverine, grazing crop land, and home garden, were identified during the assessment. Along with this, the topographic aspect, altitude, and slope of each plot were recorded using a hand-held GPS. Plant specimens were collected, pressed, dried, and transported to the national herbarium of Addis Ababa University for later identification at the species level.

2.4. Data analysis

The species richness, Shannon-Weier diversity index, and the number of stems of trees/shrubs were compared for each plot, and a one-way ANOVA was used to test for differences among the five land use types. After we found the significance difference, we executed the multiple comparisons of the means using the Tukey Honest Significance Difference (Tukey's HSD) with Bonferroni adjusted p-values within the multcomp package. The dissimilarity in species composition among the land use types and the indicator species values were analyzed by employing the Adonis2 function with 999 permutations. Adonis2 is a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (MNOVA) used for partitioning distance matrices among sources of variations among samples by measuring the dissimilarity with the Bray-Curtis distance method. To identify the characteristic and commonly occurring species in relation to the land use types, the indicator species analysis was carried out using indval functions within the labdsv package. Moreover, non-metric multidimensional scaling ordination (NMDS) was applied using the Bray-Curtis distance method to visualize the species composition along with the environmental variables in the ordination space. All statistical analyses were performed using the R statistical computing environment (version 4.2.1., R Core Team 2022).

3. Results

3.1. Species composition

A total of 285 plant species belonging to 220 genera and 89 families were recorded in the study area (Appendix 1). From the families recorded, 11.24 % were represented by more than five species, and this has contributed to 48.07 % of the total species. From these, Asteraceae, Fabaceae, Poaceae, Lamiaceae, and Solanaceae are the top five families. About 47.2 % of each of the recorded families is represented only by one species. For example, those species include Apodytes dimidiata (Icacinaceae), Celtis africana (Ulmaceae), Combretum paniculatum (Combretaceae), Grewia ferruginea (Tiliaceae), and Pittosporum viridiflorum (Pittosporaceae).

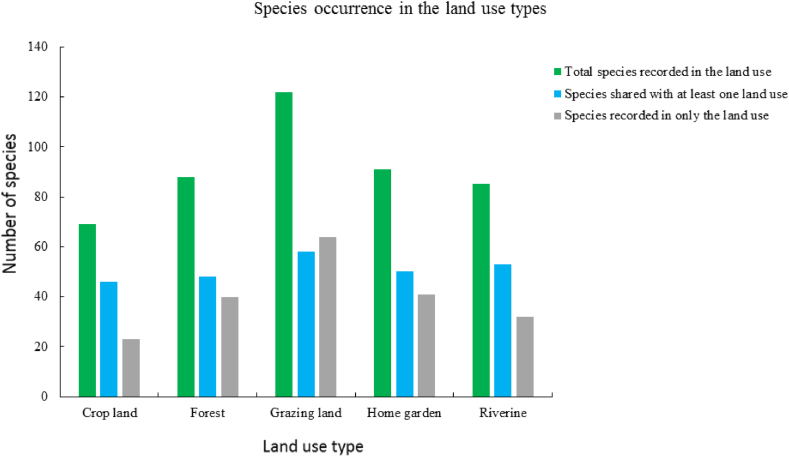

From the total species, grazing land shares the highest proportion (20.35 %), followed by riverine (18.60 %), home garden (17.54 %), forest (16.84 %), and crop land (16.14 %) with other land use types (Fig. 2). However, the unique species for each land use type is higher for grazing land (22.46 %), followed by home gardens (14.39 %), and crop land (8.07 %).

Fig. 2.

The bar graph showing the shared and unique and total species richness with respect to the land us types.

The species composition was significantly dissimilar among the land use types (Adonis2, p < 0.001). This dissimilarity was clearly indicated by the significant differences in indicator species values among the land use types (Table 1). Accordingly, Ficus vasta, Cordia africana and Achyranthes aspera are common in crop land; Hypoestes forskaolii, Vernonia myriantha, Calpurnia aurea, Carissa spinarum, Allophylus abyssinicus, Apodytes dimidiata and Teclea nobilis in forest land use; Erythrococca abyssinica, Tapinanthus heteromorphus, Hygrophila schulli and Erythrina brucei in grazing land; Coffea arabica, Justicia schimperiana, Caesalpinia decapetala, Musa paradisiaca, Vernonia amygdalina, Catha edulis in home gardens; and Celtis africana, Vangueria apiculata, Phytolacca dodecandra, Ficus sur, Dracaena steudneri and Millettia ferruginea were the indicator species in riverine land use types (Table 1).

Table 1.

Indicator species showing the diversity of the land use types with significant statistical value (p < 0.05).

| Species | Crop land | Forest | Grazing land | Homegarden | Riverine | p-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caesalpinia decapetala | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.266 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| Celtis africana | 0.054 | 0.164 | 0.042 | 0.001 | 0.315 | 0.001 |

| Coffea arabica | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.345 | 0.040 | 0.001 |

| Dracaena steudneri | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.233 | 0.001 |

| Ficus vasta | 0.268 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| Hypoestes forskaolii | 0.000 | 0.400 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| Justicia schimperiana | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.318 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| Musa paradisiaca | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.233 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| Phytolacca dodecandra | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.250 | 0.001 |

| Vangueria apiculata | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.266 | 0.001 |

| Allophylus abyssinicus | 0.000 | 0.217 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.036 | 0.002 |

| Carissa spinarum | 0.000 | 0.241 | 0.017 | 0.000 | 0.105 | 0.002 |

| Millettia ferruginea | 0.000 | 0.046 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.230 | 0.002 |

| Apodytes dimidiata | 0.023 | 0.204 | 0.021 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.003 |

| Cordia africana | 0.260 | 0.050 | 0.020 | 0.120 | 0.030 | 0.003 |

| Erythrococca abyssinica | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.187 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 |

| Ricinus communis | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.200 | 0.000 | 0.003 |

| Teclea nobilis | 0.000 | 0.180 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.037 | 0.003 |

| Catha edulis | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.200 | 0.000 | 0.004 |

| Vernonia myriantha | 0.008 | 0.290 | 0.102 | 0.013 | 0.050 | 0.004 |

| Vernonia amygdalina | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.220 | 0.127 | 0.005 |

| Adiantum poiretii | 0.000 | 0.150 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.006 |

| Hygrophila schulli | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.165 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.007 |

| Mangifera indica | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.166 | 0.000 | 0.007 |

| Solanecio gigas | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.187 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.007 |

| Dombeya torrida | 0.000 | 0.150 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.008 |

| Ficus sur | 0.015 | 0.178 | 0.032 | 0.000 | 0.244 | 0.009 |

| Vepris dainellii | 0.000 | 0.150 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.010 |

| Rhamnus prinoides | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.177 | 0.044 | 0.011 |

| Plectranthus punctatus | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.133 | 0.012 |

| Urera hypselodendron | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.133 | 0.013 |

| Ensete ventricosum | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.166 | 0.000 | 0.014 |

| Erythrina brucei | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.157 | 0.001 | 0.064 | 0.015 |

| Calpurnia aurea | 0.044 | 0.257 | 0.103 | 0.113 | 0.027 | 0.016 |

| Persea americana | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.133 | 0.000 | 0.016 |

| Rumex abyssinica | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.133 | 0.016 |

| Eucalyptus camaldulensis | 0.113 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.178 | 0.000 | 0.020 |

| Schefflera abyssinica | 0.014 | 0.143 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.020 |

| Maesa lanceolata | 0.000 | 0.163 | 0.012 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.022 |

| Desmodium repandum | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.133 | 0.024 |

| Rosa abyssinica | 0.000 | 0.124 | 0.010 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.024 |

| Tapinanthus heteromorphus | 0.057 | 0.118 | 0.185 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.024 |

| Hypericum quartinianum | 0.000 | 0.110 | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.025 |

| Mikaniopsis clematoides | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.125 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.027 |

| Rumex nervosus | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.120 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.027 |

| Laggera crispata | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.125 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.037 |

| Rubus apetalus | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 0.101 | 0.038 |

| Solanum aculeatissom | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.125 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.039 |

| Achyranthes aspera | 0.122 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.044 |

| Salix mucronata | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.106 | 0.049 |

The NMDS analysis indicated that the species composition in forest, riverine and grazing land has relatively more association with aspect, slope and altitude gradients as compared crop land, and home garden (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

A non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plot of the data set by land use types with the aspect, altitude, and slope showing the species dissimilarity composition among the different land use types in the study area.

3.1.1. Species diversity

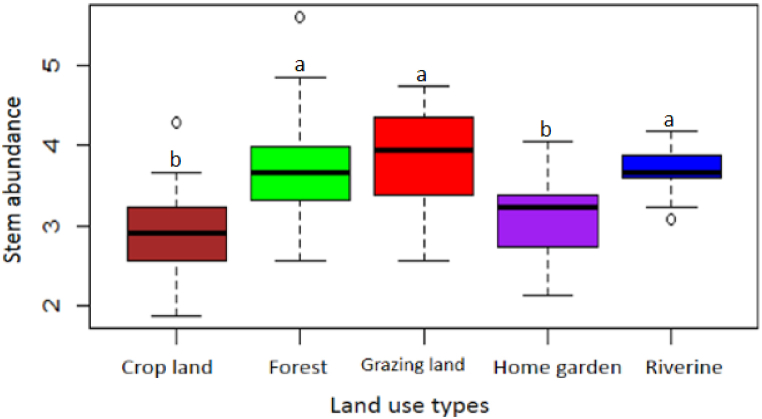

The result of the one-way ANOVA showed that species richness and stem abundance significantly vary among the land use types (P < 0.05). The mean species richness was highest in grazing land (7.63 ± 0.82), followed by riverine (5.67 ± 1.1), forest (4.40 ± 1.23), home garden (3.03 ± 0.67) and crop land (1.68 ± 1.11). However, the Shannon-Weiner diversity is higher for forest land use (2.99) but lower for the home garden (1.06); (Fig. 4). The species stem density per hectare is higher in grazing land and forest when compared with the other land use types (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

The boxplot showing the species diversity across the land use types (using square root of species diversity). The difference in the lowercase letters on the boxplots shows significant differences in species diversity among the land use types (P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

The boxplot showing the abundance of woody stem across the land use types (using square root of species stem abundance). The difference in the lowercase letters on the boxplots shows significant differences in woody stem abundance among the land use types (P < 0.05).

4. Discussions

In agricultural landscapes, different land use systems have emerged as a result of habitat loss and forest fragmentation, which are the main factors contributing to the decline of natural ecosystems. It is crucial to investigate how a variety of plant species are supported by such diverse land use systems embedded in agricultural landscapes. To do this, we evaluated and analyzed the floristic composition, species diversity, species richness, woody stem abundance, and indicator species for diverse plant species across a range of land use systems in the agricultural landscape of west Oromia. The overall findings of the study are consistent with data compiled on the flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea since the Asteraceae, Fabaceae, and Poaceae families consist of the most prevalent species in the agroecosystem (Appendix I). Their dominant position could perhaps be due to efficient pollination and successful seed dispersal mechanisms that might have contributed to their adaptation to spread over a wide range of ecological conditions [38,39]. Contrarily, families like Icacinaceae, Ulmaceae, Combretaceae, Tiliaceae, and Pittosporaceae, which are represented by only species, may be lost from the area because of environmental impacts like human overexploitation.

The proportions of total species shared and unique within each land use type may explain the association among the land use types (Fig. 2). In grazing land, 22.46 % of the total species that were unique to the land use type could contribute to the extent of dissimilarity it has from the other land use types. Similarly, the lowest value evaluated for the proportion of species unique to crop land (8.07 %) indicated that its dissimilarity with the other land use types is lower. On the contrary, the highest and lowest proportions of species shared by grazing land (20.35 %) and crop land (16.14 %), respectively, could contribute to the similarity the various land use types have in common. The higher proportion of species found in grazing land (20.35 %) and riverine (18.60 %) compared to other land use types indicated that they are playing important roles in conserving plant species diversities in the landscape.

Despite the land use types that are making this important contribution, most tree species like Albizia schimperiana, Celtis africana, Cordia africana and Vachellia abyssinica were found standing without representative seedlings in the crop land, grazing land, and home garden. The highest proportion of species occurrence only in the grazing land contributes to the highest records of herbaceous plants obtained from the land use type than in the others.

The output of species dissimilarity analysis indicated that the contribution of species composition to the variation of land use types was based on the contribution of indicator species (Table 1). The fact that Hypoestes forskaolii, Vernoni amyriantha, Calpurnia aurea, Carissa spinarum, Allophylus abyssinicus, Apodytes dimidiata and Teclea nobilis species contributed to the dissimilarity of the forest indicates that these species have higher occurrence records in the forest than the rest of the land use types. Similarly, the species Erythrococca abyssinica, Solanecio gigas, Hygrophila schulli and Erythrina brucei in the grazing land and Ficus vasta, Cordia africana and Achyranthes aspera in the crop land showed the dissimilarity of the land use types due to their higher occurrence proportions. Focusing on the home garden, Coffea arabica, Musa paradisiaca, Catha edulis, Rhamnu sprinoides, Mangifera indica, Ensete ventricosum and Persea americana played an important role in the variation of land use types in species composition. Here, the dissimilarity of species composition played a role in the variation and could be contributed to by a human-assisted conservation intervention because of the economic significance of the species.

Conversely, species such as Vangueria apiculata, Ficus sur, Dracaena steudneri, Millettia ferruginea, and Salix mucronata played a role in land use variation in the riverine area. The species contribution to this dissimilarity in the riverine area could be due to their affinity to survive in wetland d environments. Land use cover change can contribute to the variation of species composition observed among the land use types due to anthropogenic impacts exerted on land features when utilizing them for different purposes [40,41].

The NMDS ordination analysis indicated that altitude and slope determined the distributions of plant species in the forest, grazing land, and riverine, while their influences were slightly moderate on those distributed in the crop land and home garden (Fig. 3). On the other hand, despite aspects that seem to have a contribution to influence the species distribution in the forest, grazing land, and riverine, their influence is low as compared with the altitude and slope (Fig. 3). This aspect could have little influence on the plant species distribution in the study landscape because Ethiopia is located in a tropical region where sunlight is almost fully available in all directions [42]. In the landscape, the highest species diversity index (i.e., with greater equitability) achieved by the forest (2.99) and crop land (1.86) allowed them to be more stable in species composition. Conversely, grazing land, the most species-rich land use type (7.63 ± 0.82), achieved a lower value of the species diversity index (1.53) and a lower value of equitability. This may be due to the fact that plant species found in the forest are comparatively less exposed to destruction and due to the contribution of remnant standing shade trees left in the crop land for a long time [43,44]. Moreover, grazing land and home garden land use types consisting of 122 and 91 species, respectively, comprise the most species-rich positions in the landscape and can be explained as semi-natural potential refugia for implementing species conservation management practices [45,46]. In general, the variations observed in the distribution patterns of species richness and stem abundance among the different land use types (Fig. 4, Fig. 5) may be attributed to selective cuttings exerted on some woody species [[47], [48], [49]] by local communities for different purposes. However, as our objective did not include seeing the regeneration status of the vegetation, this study has focused only on species composition and diversity aspects. So, not making an assessment of the regeneration status of the plant species recorded in the land use habitats is a limitation of the study, and thus interested researchers can fill the potential gap.

5. Conclusion

A landscape comprising different land use management units utilized for crop cultivation, cattle grazing, human settlement, and traditionally conserving fragmented forest patches can be considered an agricultural landscape. Such land use types can support a vast number of biological diversities and thus play important roles in maintaining the overall well-being of local ecosystems. Based on the results of our study, it is clear that a variety of plant species are distributed across different land use patterns identified in the agricultural landscape. The fact that the grazing land and home garden took the most species-rich position indicated that these human-modified habitats can be considered as potential refugia for conserving important plant species. Additionally, despite some economically important plant species being managed in some home gardens, they are lacking in most home gardens of the local community. Moreover, remnant patch forests found in the study landscape are still experiencing serious degradation and thus need close conservation management attention. Therefore, plant biodiversity conservationists should pay close attention to the roles played by land use types in conserving diverse plant species in agroecosystems and incorporate conservation strategies into their plans for their further implementation. In conclusion, studying the regeneration status, soil seed bank, and carbon sequestration are future potential research areas in the ecological area.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Data availability statement

The data used in the study will be made available on request from the corresponding author.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zerihun Tadesse: Validation, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Sileshi Nemomissa: Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. Debissa Lemessa: Supervision, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

We express our gratitude to Addis Ababa University and Wollega University for their financial support. We thank the Gudeya Bila District Administration and local communities for allowing us to collect data. Our thanks also go to Shitaye Deti, Kemal Mustefa, and Habtamu Getachew for their full assistance during the data collection.

Appendix 1. List of plant species recorded from the study landscape in Gudeya Bila District: crop land (Cl), fragmented forest (Fr), grazing land (Gl), home garden (Hg) and riverine (Rv)

| No | Species | Family | Land use types | Coll. code | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acanthus eminens C.B.Clarke | Acanthaceae | Rv | ZT176 | ||||

| 2 | Acanthus polystachius Delile | Amaranthaceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Rv | ZT001 | |

| 3 | Achyranthes aspera L. | Amarantaceae | Cl | Hg | ZT145 | |||

| 4 | Adiantum poiretii Wikstr. | Adiantaceae | Fr | ZT148 | ||||

| 5 | Aeschynomene schimperi Hochst. exA. Rich. | Fabaceae | Hg | ZT149 | ||||

| 6 | Agave sisenara Perrine ex Engl. | Aloaceae | Cl | Hg | ZT158 | |||

| 7 | Ageratum conyzoides L. | Asteraceae | Hg | ZT159 | ||||

| 8 | Albizia schimperiana Oliv. | Fabaceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT004 |

| 9 | Allophylus abyssinicus (Hochst.) Radlk. | Sapindaceae | Fr | Rv | ZT006 | |||

| 10 | Alcea roseus L. | Malvaceae | Hg | ZT003 | ||||

| 11 | Amaranthus spinosus L. | Amaranthaceae | Hg | Rv | ZT002 | |||

| 12 | Amorphophallus abyssinicus (A. Rich.) N.E. Sr. | Araceae | Rv | ZT011 | ||||

| 13 | Amphicarpa africana (Hook. f.) Harms | Fabaceae | Fr | ZT089 | ||||

| 14 | Anagalis arvensis L. | Primulaceae | Fr | ZT239 | ||||

| 15 | Andropogon abyssinicus Fresen. | Poaceae | Cl | Hg | ZT173 | |||

| 16 | Anethum graveolens L. | Apiaceae | Gl | ZT223 | ||||

| 17 | Apodytes dimidiata E. Mey. ex Am | Icacinaceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Hg | ZT224 | |

| 18 | Argemone mexicana L | Solanaceae | Cl | Gl | ZT241 | |||

| 19 | Arisaema schimperiana Schott | Araceae | Rv | ZT016 | ||||

| 20 | Arundinaria alpina K.Schum. | Poaceae | Cl | ZT123 | ||||

| 21 | Arundo donax L. | Poaceae | Hg | ZT187 | ||||

| 22 | Asparagus africanus Lam. | Asparagaceae | Fr | ZT210 | ||||

| 23 | Bartsia trixago L. | Scrophulariaceae | Gl | ZT268 | ||||

| 24 | Berkheya spekeana Oliv. | Asteraceae | Cl | ZT042 | ||||

| 25 | Bersama abyssinica Fresen. | Melianthaceae | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT069 | |

| 26 | Bidens biternata (Lour.) Merr. & Sherfft | Asteraceae | Hg | ZT012 | ||||

| 27 | Bidens pilosa L. | Asteraceae | Hg | ZT019 | ||||

| 28 | Bidens prestinaria (Sch, Bip.) Cufod. | Asteraceae | Hg | ZT240 | ||||

| 29 | Bougainvillea spectabilis Witld. | Nyctaginaceae | Hg | ZT206 | ||||

| 30 | Brucea antidysenterica J.F.Mill. | Simaroubaceae | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT101 | |

| 31 | Buddleja cordata B.K. | Loganiaceae | Fr | ZT204 | ||||

| 32 | Buddleja polystachya Fresen. | Loganiaceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT264 |

| 33 | Caesalpinia decapetala (Roth) Alston | Fabaceae | Hg | ZT022 | ||||

| 34 | Callistemon citrinus (Curtis) Skeels | Myrtaceae | Hg | ZT007 | ||||

| 35 | Callistemon salignus(Sm.) Sweet | Myrtaceae | Hg | ZT024 | ||||

| 36 | Calpurnia aurea (Ait.) Benth. | Fabaceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT026 |

| 37 | Canarina abyssinica Engl. | Campanulaceae | Fr | ZT027 | ||||

| 38 | Capparis tomentosa Lam. | Capparidaceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT028 |

| 39 | Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medic. | Brassicaceae | Cl | ZT040 | ||||

| 40 | Carduus nyassanus (S. Moore) R.E. Fries | Asteraceae | Cl | ZT051 | ||||

| 41 | Carica papaya L. | Caricaceae | Hg | ZT052 | ||||

| 42 | Carissa spinarum L. | Apocynaceae | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT053 | |

| 43 | Casimiroa edulis La Llave | Rutaceae | Hg | ZT071 | ||||

| 44 | Cassipourea malosana (Baker) Alston | Rhizophoraceae | Fr | ZT074 | ||||

| 45 | Catha edulis (Vahl) Forssk. a Endl. | Celastraceae | Hg | ZT075 | ||||

| 46 | Caylusea abyssinica (Fresen.) Fisch. & Mey. | Resedaceae | Cl | Gl | Hg | ZT076 | ||

| 47 | Celtis africana Burm.f. | Ulmaceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT077 |

| 48 | Chenopodium album L. | Chenopodiaceae | Gl | ZT078 | ||||

| 49 | Chenopodium ambrosioides L. | Chenopodiaceae | Cl | ZT079 | ||||

| 50 | Chionanthus mildbraedii (Gilg & Schel/enb.) Stearn | Oleaceae | Rv | ZT093 | ||||

| 51 | Cinenaria deltoidea Sond. | Asteraceae | Rv | ZT103 | ||||

| 52 | Cirsium englerainum O. | Asteraceae | Gl | ZT104 | ||||

| 53 | Cirsium schimperi (Vatke) C. Jeffrey ex Cufod. | Asteraceae | Cl | ZT124 | ||||

| 54 | Citrus limon (L.) Bunnf. | Rutaceae | Hg | ZT125 | ||||

| 55 | Citrus medica L. | Rutaceae | Hg | ZT131 | ||||

| 56 | Citrus sinensis (L.) Osb. | Rutaceae | Hg | ZT136 | ||||

| 57 | Clausena anisata (Willd). Benth. | Rutaceae | Cl | Fr | ZT137 | |||

| 58 | Clematis longicauda Steud.ex A. Rich. | Ranunculaceae | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT139 | |

| 59 | Clematis sinensis Fresen. | Rununculaceae | Rv | ZT153 | ||||

| 60 | Clerodendron myricoides (Hochst.) Vatke | Lamiaceae | Gl | ZT163 | ||||

| 61 | Clutia abyssinica Jaub. &- Spach. | Euphorbiaceae | Fr | ZT165 | ||||

| 62 | Coffea arabica L. | Rubiaceae | Hg | Rv | ZT177 | |||

| 63 | Combretum paniculatum Vent. | Combretaceae | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT250 | |

| 64 | Commelina africana L. | Commelinaceae | Fr | ZT257 | ||||

| 65 | Commelina bengalensis L. | Commelinaceae | Fr | Rv | ZT258 | |||

| 66 | Commelina diffusa Burm.f. | Commelinaceae | Gl | ZT279 | ||||

| 67 | Commelina subulata Roth | Commelinaceae | Gl | ZT280 | ||||

| 68 | Gomphocarpus fruticosus (L.) Ait. f. | Apocynaceae | Gl | ZT281 | ||||

| 69 | Convolvulus kilimandschari Engl. | Convolvulaceae | Hg | ZT282 | ||||

| 70 | Conyza stricta Willd. | Asteraceae | Cl | Gl | Hg | ZT283 | ||

| 71 | Copressus lustanica Mill. | Cupressaceae | Cl | Hg | ZT284 | |||

| 72 | Cordia africana L. | Boraginaceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT285 |

| 73 | Cotula abyssinica Sch. Bip. exA. Rich. | Asteraceae | Fr | ZT150 | ||||

| 74 | Crassocephalum crepidioides (Benth.) S. Moore | Asteraceae | Cl | ZT151 | ||||

| 75 | Crassocephalum macropappum (Sch. Bip. ex A. Rich.) S. Moore | Asteraceae | Cl | ZT155 | ||||

| 76 | Crassocephalum rubens (Juss. ex Jacq.) S. Moore | Asteraceae | Gl | Rv | ZT259 | |||

| 77 | Crepis rueppel Sch. Bip. | Asteraceae | Cl | Gl | ZT262 | |||

| 78 | Crepis tenerrima (Seh. Hip. ex A. Rich.) R. E. Fries. | Asteraceae | Gl | ZT073 | ||||

| 79 | Crotalaria emarginella Vatke | Fabaceae | Rv | ZT086 | ||||

| 80 | Crotalaria incana L. | Fabaceae | Gl | ZT105 | ||||

| 81 | Croton macrostachyus Del. | Euphorbiaceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT141 |

| 82 | Cyanotis caespitosa Kot1lchy & Peyr. | Commelinaceae | Gl | ZT265 | ||||

| 83 | Cyathula cylinderica Moq. | Amaranthaceae | Rv | ZT045 | ||||

| 84 | Cynodon aethiopicus Clayton & Harlan | Poaceae | Gl | ZT039 | ||||

| 85 | Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. | Poaceae | Gl | ZT037 | ||||

| 86 | Cynodon nlemfuensis Vanderyst | Poaceae | Gl | ZT038 | ||||

| 87 | Cynoglossum coeruleum Hochst. exA.DC. in DC. | Boraginaceae | Gl | ZT226 | ||||

| 88 | Cyperus mundtii (Nees) Kunth | Cyperaceae | Fr | ZT041 | ||||

| 89 | Cyperus triceps Endl | Cyperaceae | Fr | ZT273 | ||||

| 90 | Dalbergia lactea Vatke | Fabaceae | Fr | ZT143 | ||||

| 91 | Datura stramonium L. | Solanaceae | Cl | ZT144 | ||||

| 92 | Desmodium repandum (Vahl) DC. | Fabaceae | Rv | ZT174 | ||||

| 93 | Dicrocephala integrifolia (L.f) Kuntze | Asteraceae | Cl | Gl | ZT175 | |||

| 94 | Digitalia ternata (A. Rich.) Staf | Poaceae | Gl | ZT048 | ||||

| 95 | Digitalia velutina (Forssk.) P.Beauv | Poaceae | Gl | ZT049 | ||||

| 96 | Dodonaea angustifolia L. f. | Sapindaceae | Fr | ZT063 | ||||

| 97 | Dolichos sericeus E. Mey. | Fabaceae | Gl | ZT064 | ||||

| 98 | Dombeya torrida (G.F. Gmel.) P. Bamps | Sterculiaceae | Fr | ZT065 | ||||

| 99 | Dovyalis abyssinica (A. Rich.) Warb. | Flacourtiaceae | Fr | ZT066 | ||||

| 100 | Dracaena steudneri Engl. | Dracaenaceae | Fr | Rv | ZT067 | |||

| 101 | Dregea schimperi (Decne.) Bullock | Asclepiadaceae | Gl | ZT068 | ||||

| 102 | Drynaria volkensii Hieron. | Polypodiaceae | Fr | ZT070 | ||||

| 103 | Echinops giganteus A. Rich. | Asteraceae | Gl | ZT160 | ||||

| 104 | Echinops macrochaetus Fresen. | Asteraceae | Gl | ZT161 | ||||

| 105 | Ehretia cymosa Thonn. | Boraginaceae | Cl | Hg | Rv | ZT162 | ||

| 106 | Ekebergia capensis Sparrm. | Meliaceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT171 |

| 107 | Eleusine floccifolia (Forssk.) Spreng. | Poaceae | Gl | ZT072 | ||||

| 108 | Embelia schimperi Vatke | Myrsinaceae | Rv | ZT157 | ||||

| 109 | Englerina woodfordioides (Schweinf.)M. Gilbert | Loranthaceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT087 |

| 110 | Ensete ventricosum (Welw.) Cheesman | Musaceae | Hg | ZT088 | ||||

| 111 | Erythrina brucei Schweinf. | Fabaceae | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT100 | |

| 112 | Erythrococca abyssinica Pax | Euphorbiaceae | Gl | ZT061 | ||||

| 113 | Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh. | Myrtaceae | Cl | Hg | ZT082 | |||

| 114 | Eucalyptus globulus (F.Muell.) J.B.Kirkp. | Mytaceae | Cl | Hg | ZT112 | |||

| 115 | Euphorbia ampliphylla Pax | Euphorbiaceae | Fr | Hg | Rv | ZT115 | ||

| 116 | Euphorbia buchananii Pax | Euphorbiaceae | Hg | ZT116 | ||||

| 117 | Euphorbia cotinifolia L. | Euphorbiaceae | Hg | ZT117 | ||||

| 118 | Ficus mucuso Ficalho. | Moraceae | Rv | ZT225 | ||||

| 119 | Ficus sur Forssk. | Moraceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT269 |

| 120 | Ficus thonningii Blume | Moraceae | Cl | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT270 | |

| 121 | Ficus vasta Forssk. | Moraceae | Cl | ZT005 | ||||

| 122 | Flacourtia indica (Burm.f.) Merr | Flacourtiaceae | Fr | Rv | ZT008 | |||

| 123 | Foeniculum vulgare Miller | Apiaceae | Cl | ZT013 | ||||

| 124 | Galinsoga parviflora Cav. | Asteraceae | Gl | ZT033 | ||||

| 125 | Galinsoga quadriradiata Ruiz & Pavon | Asteraceae | Gl | ZT036 | ||||

| 126 | Galium spurium L. | Runiaceae | Gl | ZT080 | ||||

| 127 | Gardenia ternifolia Schumach. &Thonn. | Rubiaceae | Cl | ZT081 | ||||

| 128 | Geranium arabicum Forssk. | Geranaceae | Gl | ZT090 | ||||

| 129 | Girardinia bullosa (Steudel) Wedd. | Urticaceae | Gl | ZT092 | ||||

| 130 | Girardinia diversifolia (Link) Friis | Urticaceae | Gl | ZT097 | ||||

| 131 | Gnaphalium rubriflorum Hilliard | Asteraceae | Fr | ZT111 | ||||

| 132 | Gnidia glauca (Fresen.) Gilg | Thymelaeaceae | Fr | ZT152 | ||||

| 133 | Gradiolus muriclae Kelway | Iridaceaea | Gl | ZT167 | ||||

| 134 | Grevillea robusta A. Cunn. ex R. Br. | Gravelliaceae | Hg | ZT178 | ||||

| 135 | Grewia ferruginea Hochst.ex A. Rich. | Tiliaceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Hg | ZT220 | |

| 136 | Guizotia scabra (Vis.) Chiov. | Asteraceae | Gl | ZT244 | ||||

| 137 | Guizotia schimperi Sch. Bip. ex Walp. | Asteraceae | Gl | ZT245 | ||||

| 138 | Hagenia abyssinica (Broce) I.F. Gmel. | Rosaceae | Cl | ZT246 | ||||

| 139 | Haplocarpha schimperi (Sch. Rip.) Beauv. | Asteraceae | Cl | ZT247 | ||||

| 140 | Helinus mystacinus (Ait.) E. Mey. ex Steud. | Rhamnaceae | Rv | ZT272 | ||||

| 141 | Heliotropium zeylanicum (Burm f.) Lam. | Boraginaceae | Cl | ZT275 | ||||

| 142 | Hibiscus vitifolius L. | Malvaceae | Rv | ZT099 | ||||

| 143 | Hippocratea africana (Willd.) Loes. | Celastraceae | Rv | ZT122 | ||||

| 144 | Hippocratea goetezi Loes. | Celastraceae | Cl | ZT128 | ||||

| 145 | Hygrophila schulli (Hamilt.) M.R. & S.M | Acanthaceae | Cl | Gl | ZT198 | |||

| 146 | Hyparrhenia anthistirioides (Hochst. ex A. Rich) | Poaceae | Rv | ZT134 | ||||

| 147 | Hypericum quartinianum A. Rich. | Guttiferae | Fr | Gl | ZT147 | |||

| 148 | Hypoestes forskaolii (Vahl) R. Br. | Acanthaceae | Fr | ZT219 | ||||

| 149 | Hypoestes triflora (Forssk.) Roem & Schult. | Acanthaceae | Rv | ZT017 | ||||

| 150 | Impatiens hocshtetteri Warb. | Balsaminaceae | Fr | ZT133 | ||||

| 151 | Impatiens rothii Hook. F | Balsaminaceae | Fr | ZT060 | ||||

| 152 | Indigofera arrecta Hochst. exA. Rich. | Fabaceae | Rv | ZT154 | ||||

| 153 | Inula confertiflora A.Rich. | Asteraceae | Gl | ZT168 | ||||

| 154 | Isodon schimperi (Vatke) J.K. Morton | Lamiaceae | Gl | ZT169 | ||||

| 155 | Jacaranda mimosifolia D. Don | Bignonaceae | Hg | ZT185 | ||||

| 156 | Jasminum abyssinicum Hochst. ex DC. | Oleaceae | Rv | ZT186 | ||||

| 157 | Juniperus procera Hochst. ex Endl. | Cupressaceae | Hg | ZT214 | ||||

| 158 | Justicia diclipteroide Lindau | Acanthaceae | Rv | ZT215 | ||||

| 159 | Justicia schimperiana (Hochst. ex Nees) T. | Acanthaceae | Gl | Hg | ZT237 | |||

| 160 | Kalanchoe densiflora Rolfe | Crassulaceae | Gl | ZT256 | ||||

| 161 | Kalanchoe petitiana A. Rich. | Crassulaceae | Gl | ZT238 | ||||

| 162 | Lagenaria abyssinica (Hookf.) C. Jeffrey | Cucurbitaceae | Gl | Rv | ZT205 | |||

| 163 | Laggera crispata (Vahl) Hepper & Wood | Asteraceae | Gl | ZT031 | ||||

| 164 | Lantana camara L. | Verbenaceae | Hg | ZT032 | ||||

| 165 | Launaea cornuta (Hochst. ex Oliv. & Hiem) C. Jeffrey | Asteraceae | Gl | ZT184 | ||||

| 166 | Lepidotrichilia volkensii (Gilrke) Leroy | Meliaceae | Fr | ZT109 | ||||

| 167 | Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.] De Wit | Fabaceae | Gl | Hg | ZT207 | |||

| 168 | Leucas deflexa Hook.f. | Lamiaceae | Gl | ZT266 | ||||

| 169 | Leucas martinicensis (Jacq.) R. Br. | Lamiaceae | Gl | ZT010 | ||||

| 170 | Lippia adoensis Hochst. ex Walp | Verbenaceae | Gl | ZT142 | ||||

| 171 | Luffa cylinderica (L.)M J. Roem | Cucurbitaceae | Hg | ZT196 | ||||

| 172 | Maesa lanceolata Forssk. | Myrsinaceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT197 |

| 173 | Mangifera indica L. | Anacardiaceae | Hg | ZT248 | ||||

| 174 | Maytenus arbutifolia (A.Rich.) Wilczek | Celastraceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | ZT106 | ||

| 175 | Maytenus gracilipes (Welw. ex Oliv.) Exell | Celastraceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Rv | ZT166 | |

| 176 | Melia azederach L. | Meliaceae | Hg | ZT025 | ||||

| 177 | Mikaniopsis clematoides (Sch. Bip. ex A. Rich.) | Asteraceae | Gl | ZT261 | ||||

| 178 | Millettia ferruginea (Hochst.) Bak. | Fabaceae | Fr | Rv | ZT118 | |||

| 179 | Morus alba L. | Rosaceae | Hg | ZT119 | ||||

| 180 | Musa paradisiaca L. | Musaceae | Hg | ZT120 | ||||

| 181 | Myrica salicifolia A.Rich. | Myricaceae | Fr | Gl | Hg | ZT121 | ||

| 182 | Nicandra physaloide (L.) Gaertn. | Solanaceae | Cl | Fr | ZT110 | |||

| 183 | Nicotiana tabacum L. | Solanaceae | Hg | ZT180 | ||||

| 184 | Nuxia congesta R.Br. ex Fresen. | Loganiaceae | Fr | Gl | ZT181 | |||

| 185 | Ocimum lamiifolium Hochst. ex. Benth. | Lamiaceae | Fr | ZT108 | ||||

| 186 | Ocimum urticifolium Roth. | Lamiaceae | Gl | ZT172 | ||||

| 187 | Oenanthe procumbens (Wolff) Norman | Apiaceae | Cl | Rv | ZT034 | |||

| 188 | Olea capensis subspecies macrocarpa (C.H. Wright) Verdc. | Oleaceae | Fr | ZT035 | ||||

| 189 | Olea europaea subspecies cuspidata (Wall.ex G.Don) Cif. | Oleaceae | Cl | Gl | Hg | ZT113 | ||

| 190 | Olinia rochetiana A.Juss. | Oliniaceae | Cl | ZT263 | ||||

| 191 | Oplismenus hirtellus (L.) P. Beauv. | Poaceae | Gl | Rv | ZT114 | |||

| 192 | Orobanchae minor Smit | Orobanchaceae | Gl | Hg | ZT029 | |||

| 193 | Osyris quadripartita Decne | Santalaceae | Fr | ZT050 | ||||

| 194 | Panicum monticola Hook.f. | Poaceae | Fr | ZT156 | ||||

| 195 | Pavetta abyssinica Fresen. | Rubiaceae | Fr | ZT188 | ||||

| 196 | Pavonia burchellii (DC.) Dyer | Malvaceae | Fr | ZT189 | ||||

| 197 | Pavonia urens Cav. | Malvaceae | Hg | Rv | ZT242 | |||

| 198 | Pelargonium multibracteatum Hochst. exA. Rich. | Geraniaceae | Hg | ZT190 | ||||

| 199 | Pennisetum clandestinum Chiov. | Poaceae | Gl | ZT232 | ||||

| 200 | Pennisetum schimperi A. Rich. | Poaceae | Gl | ZT233 | ||||

| 201 | Pennisetum sphacelatum (Nees) Th. Dur. | Poaceae | Gl | ZT271 | ||||

| 202 | Pennisetum thunbergii Kunth | Poaceae | Gl | ZT192 | ||||

| 203 | Periploca linearifolia Quart.-Dill. & A. Rich. | Asclepiadaceae | Fr | ZT211 | ||||

| 204 | Persicaria decipiens (R. Br.) K.L. Wilson | Polygonaceae | Cl | Hg | ZT209 | |||

| 205 | Persea americana Mill. | Lauraceae | Hg | ZT212 | ||||

| 206 | Phoenix reclinata Jacq. | Arecaceae | Rv | ZT213 | ||||

| 207 | Phragmanthera macrosolen (A. Rich.] M. Gilbert | Loranthaceae | Cl | ZT015 | ||||

| 208 | Physalis peruviana L. | Solanaceae | Gl | ZT020 | ||||

| 209 | Phytolacca dodecandra L'Herit. | Phytolaccaceae | Hg | Rv | ZT021 | |||

| 210 | Pimpinella oreophila Hook. J | Apiaceae | Rv | ZT083 | ||||

| 211 | Pinus radiata D. Don | Pinaceae | Hg | ZT084 | ||||

| 212 | Pittosporum viridiflorum Sims | Pittosporaceae | Cl | Gl | Rv | ZT085 | ||

| 213 | Plantago lanceolata L. | Plantaginaceae | Cl | ZT094 | ||||

| 214 | Platostoma roundifolia (Briq.) AJ. Paton | Lamiaceae | Rv | ZT095 | ||||

| 215 | Plectranthus punctatus (L.f.) L'H'er. | Lamiaceae | Rv | ZT107 | ||||

| 216 | Podocarpus falcatus (Thunb.) R.B. ex. Mirb. | Podocarpaceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT146 |

| 217 | Pouteria adolfi-friederici (Engl.) Baehni | Sapotaceae | Rv | ZT191 | ||||

| 218 | Prunus africana (Hook.f.) Kalkm. | Rosaceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT194 |

| 219 | Pteridium aqulinium (L.) Kuhn | Hypolepidaceae | Rv | ZT199 | ||||

| 220 | Pterolobium stellantum (Forssk.) Brenan | Fabaceae | Fr | Gl | ZT200 | |||

| 221 | Rhamnus prinoides L'Herit. | Rhamnaceae | Hg | Rv | ZT201 | |||

| 222 | Rhiocissus tridentata (L. f.) Wild & Drummond | Vitaceae | Gl | Rv | ZT202 | |||

| 223 | Rhus glutinosa A.Rich. | Anacardiaceae | Fr | ZT249 | ||||

| 224 | Rhus natalensis Krauss | Anacardiaceae | Fr | ZT260 | ||||

| 225 | Ricinus communis L. | Euphorbiaceae | Hg | ZT216 | ||||

| 226 | Ritchiea albersi Gilg | Capparidaceae | Cl | Gl | ZT203 | |||

| 227 | Rosa abyssinica Lindley | Rosaceae | Fr | Gl | ZT234 | |||

| 228 | Rothmannia urcelliformis (Hiem) Robyns | Rubiaceae | Rv | ZT102 | ||||

| 229 | Rubia cordifolia L. | Rubiaceae | Rv | ZT014 | ||||

| 230 | Rubus apetalus Poir. | Rosaceae | Gl | Rv | ZT058 | |||

| 231 | Rubus steudneri Schweinf. | Rosaceae | Gl | Rv | ZT046 | |||

| 232 | Rumex abyssinica Jacq. | Polygonaceae | Rv | ZT140 | ||||

| 233 | Rumex nepalensis Spreng. | Polygonaceae | Gl | ZT221 | ||||

| 234 | Rumex nervosus Vahl | Polygonaceae | Gl | ZT243 | ||||

| 235 | Rytigynia neglecta (Hiern) Robyns | Rubiaceae | Fr | Gl | Rv | ZT044 | ||

| 236 | Salix mucronata Thunb. (S. subserrata Willd) | Salicaceae | Hg | Rv | ZT138 | |||

| 237 | Salvia nilotica Jacq. | Lamiaceae | Gl | ZT179 | ||||

| 238 | Satureja paradoxa (Vatke) Engl. ex Seybold | Lamiaceae | Gl | ZT218 | ||||

| 239 | Scadoxus multiflorus (Martyn) Raf'. | Amaryllidaceae | Gl | Rv | ZT227 | |||

| 240 | Schefflera abyssinica (Hochst. ex A. Rich.) | Araliaceae | Cl | Fr | Hg | ZT230 | ||

| 241 | Schinus molle L. | Anacardiaceae | Hg | ZT231 | ||||

| 242 | Schrebera alata (Hochst.) Welw. | Oleaceae | Gl | ZT062 | ||||

| 243 | Scutia myrtina (Burm. f.) Kurz | Rhamnaceae | Rv | ZT127 | ||||

| 244 | Senna didymobotrya (Fresen.) Irwin& Bameby | Fabaceae | Gl | ZT195 | ||||

| 245 | Senna petersiana (Bolle) Lock | Fabaceae | Hg | Rv | ZT228 | |||

| 246 | Senna septemterioles (Viv.) Irwin & Bameby | Fabaceae | Hg | ZT229 | ||||

| 247 | Sesbania sesban (L) Merr | Fabaceae | Hg | ZT235 | ||||

| 248 | Sida rhombifolia L. | Malvaceae | Gl | ZT276 | ||||

| 249 | Snowdenia polystachya (Fresen.) Pilg. | Poaceae | Hg | ZT126 | ||||

| 250 | Solanecio gigas Boulos ex Humbert | Asteraceae | Gl | ZT059 | ||||

| 251 | Solanum aculeatissom Jacq. | Solanaceae | Gl | ZT043 | ||||

| 252 | Solanum anguivi Lam. | Solanaceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT054 |

| 253 | Solanum marginatum L.f. | Solanaceae | Gl | ZT055 | ||||

| 254 | Solanum nigrum L. | Solanaceae | Gl | ZT056 | ||||

| 255 | Discopodium penninervium Hochst. | Solanaceae | Gl | ZT057 | ||||

| 256 | Solenostemon autrani (Briq.) J.K. Morton | Lamiaceae | Cl | ZT267 | ||||

| 257 | Sonchus oleraceus L. | Asteraceae | Cl | ZT277 | ||||

| 258 | Sonchus schweinfurthii Olivo & Hiem | Asteraceae | Cl | ZT236 | ||||

| 259 | Spathodea campanulata P. Beauv. | Bignoniaceae | Hg | ZT193 | ||||

| 260 | Sporobolus africanus (Poir.) Robyns & Tourny | Poaceae | Cl | ZT009 | ||||

| 261 | Stephania abyssinica (Dillon & A. Rich.) Walp. | Menispermaceae | Fr | ZT096 | ||||

| 262 | Stereospermum kunthianum Cham. | Bignoniaceae | Fr | ZT217 | ||||

| 263 | Syzygium guineense (Willd.) DC. | Myrtaceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | ZT023 | ||

| 264 | Tacazzea conferta N.E. Br. | Asclepiadaceae | Fr | ZT278 | ||||

| 265 | Tagestes minuta L. | Asteraceae | Fr | Gl | Rv | ZT030 | ||

| 266 | Tapinanthus heteromorphus (A. Rich.] Danser | Loranthaceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | ZT018 | ||

| 267 | Teclea nobilis Del. | Rutaceae | Fr | Rv | ZT091 | |||

| 268 | Torilis arvensis (Hudson) Link | Apiaceae | Rv | ZT182 | ||||

| 269 | Tragia brevipes Pax | Euphorbiaceae | Rv | ZT183 | ||||

| 270 | Tragia doryodes AI. Gilbert | Euphorbiaceae | Fr | ZT208 | ||||

| 271 | Tridactyle filifolia (Schltr.) Schltr | Orchidaceae | Gl | ZT251 | ||||

| 272 | Trifolium rueppellianum Fresen. | Fabaceae | Gl | ZT252 | ||||

| 273 | Uebelinia abyssinica Hochst. | Caryophyllaceae | Hg | ZT253 | ||||

| 274 | Urera hypselodendron (A.Rich) Wedd. | Urticaceae | Rv | ZT254 | ||||

| 275 | Vachellia abyssinica (Hochst. ex Benth.) Kyal. & Boatwr. | Fabaceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT255 |

| 276 | Vangueria apiculata K. Schum. | Rubiaceae | Rv | ZT098 | ||||

| 277 | Vepris dainellii(Pichi-Serm.) Kokwaro | Rutaceae | Fr | ZT132 | ||||

| 278 | Verbsacum sinaiticum Benth. | Scrophulariaceae | Gl | ZT135 | ||||

| 279 | Vernonia amygdalina Del. | Asteraceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT047 |

| 280 | Vernonia bipontini Vatke | Asteraceae | Fr | ZT129 | ||||

| 281 | Vernonia brachycalyx O. Hoffm. | Asteraceae | Fr | ZT130 | ||||

| 282 | Vernonia hymenolepsi A. Rich. | Asteraceae | Fr | ZT274 | ||||

| 283 | Vernonia leopoldi (Sch. Bip. ex Walp.) Vatke | Asteraceae | Fr | Gl | ZT164 | |||

| 284 | Vernonia myriantha Hook.f. | Asteraceae | Cl | Fr | Gl | Hg | Rv | ZT170 |

| 285 | Vernonia thomsoniana Olivo & Hiern ex Oliv. | Asteraceae | Gl | ZT222 | ||||

References

- 1.Vieira I.C.G., Toledo P.d., Silva J.d., Higuchi H. Deforestation and threats to the biodiversity of Amazonia. Braz. J. Biol. 2008;68:949–956. doi: 10.1590/s1519-69842008000500004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chakravarty S., Ghosh S., Suresh C., Dey A., Shukla G. Deforestation: causes, effects and control strategies. Global perspectives on sustainable forest management. 2012;1:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ray R., Chandran M., Ramachandra T. Biodiversity and ecological assessments of Indian sacred groves. J. For. Res. 2014;25:21–28. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fischer J., Lindenmayer D.B. Landscape modification and habitat fragmentation: a synthesis. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 2007;16:265–280. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giam X., Bradshaw C.J., Tan H.T., Sodhi N.S. Future habitat loss and the conservation of plant biodiversity. Biol. Conserv. 2010;143:1594–1602. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mantyka‐pringle C.S., Martin T.G., Rhodes J.R. Interactions between climate and habitat loss effects on biodiversity: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Global Change Biol. 2012;18:1239–1252. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhumanova M., Mönnig C., Hergarten C., Darr D., Wrage-Mönnig N. Assessment of vegetation degradation in mountainous pastures of the Western Tien-Shan, Kyrgyzstan, using eMODIS NDVI. Ecol. Indicat. 2018;95:527–543. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zoungrana B.J., Conrad C., Thiel M., Amekudzi L.K., Da E.D. MODIS NDVI trends and fractional land cover change for improved assessments of vegetation degradation in Burkina Faso, West Africa. J. Arid Environ. 2018;153:66–75. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mengist W., Soromessa T., Feyisa G.L. Landscape change effects on habitat quality in a forest biosphere reserve: implications for the conservation of native habitats. J. Clean. Prod. 2021;329 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giam X. Global biodiversity loss from tropical deforestation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:5775–5777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706264114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Decaens T., Martins M.B., Feijoo A., Oszwald J., Dolédec S., Mathieu J., Arnaud de Sartre X., Bonilla D., Brown G.G., Cuellar, Criollo Y.A. Biodiversity loss along a gradient of deforestation in Amazonian agricultural landscapes. Conserv. Biol. 2018;32:1380–1391. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acheampong E.O., Macgregor C.J., Sloan S., Sayer J. Deforestation is driven by agricultural expansion in Ghana's forest reserves. Scientific African. 2019;5 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daye D.D. Bangor University; United Kingdom: 2012. Fragmented Forests in South-West Ethiopia: Impacts of Land-Use Change on Plant Species Composition and Priorities for Future Conservation. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitiku A.A. University of Pretoria; 2013. Afromontane Avian Assemblages and Land Use in the Bale Mountains of Ethiopia: Patterns, Processes and Conservation Implications. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peet R.K., Roberts D.W. Classification of natural and semi-natural vegetation. Vegetation ecology. 2013:28–70. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malhi Y., Gardner T.A., Goldsmith G.R., Silman M.R., Zelazowski P. Tropical forests in the anthropocene. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2014;39:125–159. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Southworth J., Munroe D., Nagendra H. Land cover change and landscape fragmentation—comparing the utility of continuous and discrete analyses for a western Honduras region. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2004;101:185–205. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartter J., Southworth J. Dwindling resources and fragmentation of landscapes around parks: wetlands and forest patches around Kibale National Park, Uganda. Landsc. Ecol. 2009;24:643–656. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adal H., Asfaw Z. 2016. A Pragmatic Comparison of Smallholder Farmers' Perceptions and Attitudes towards Integration of Trees in Farmed Landscapes in North Eastern Ethiopia. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindenmayer D.B., Franklin J.F. Island press; 2002. Conserving Forest Biodiversity: a Comprehensive Multiscaled Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angelstam P., Bergman P. Assessing actual landscapes for the maintenance of forest biodiversity: a pilot study using forest management data. Ecol. Bull. 2004:413–425. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plieninger T., Schleyer C., Mantel M., Hostert P. Is there a forest transition outside forests? Trajectories of farm trees and effects on ecosystem services in an agricultural landscape in Eastern Germany. Land Use Pol. 2012;29:233–243. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keeton W.S., Crow S.M. Ecological Economics and Sustainable Forest Management: Developing a Trans-disciplinary Approach for the Carpathian Mountains. 2009. Sustainable forest management alternatives for the Carpathian Mountain region: providing a broad array of ecosystem services; pp. 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharpe D., Guntenspergen G., Dunn C., Leitner L., Stearns F. Landscape Heterogeneity and Disturbance. Springer; 1987. Vegetation dynamics in a southern Wisconsin agricultural landscape; pp. 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lameire S., Hermy M., Honnay O. Two decades of change in the ground vegetation of a mixed deciduous forest in an agricultural landscape. J. Veg. Sci. 2000;11:695–704. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson M.C., Norman J.M., Kustas W.P., Li F., Prueger J.H., Mecikalski J.R. Effects of vegetation clumping on two–source model estimates of surface energy fluxes from an agricultural landscape during SMACEX. J. Hydrometeorol. 2005;6:892–909. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bishaw B. Deforestation and land degradation in the Ethiopian highlands: a strategy for physical recovery. NE Afr. Stud. 2001:7–25. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chimdesa G. The political economy of deforestation and forest degradation in Ethiopia. J. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2017;29:38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Getahun K., Poesen J., Van Rompaey A. Impacts of resettlement programs on deforestation of moist evergreen Afromontane forests in Southwest Ethiopia. Mt. Res. Dev. 2017;37:474–486. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abera A., Yirgu T., Uncha A. Impact of resettlement scheme on vegetation cover and its implications on conservation in Chewaka district of Ethiopia. Environmental Systems Research. 2020;9:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fetene A., Bekele T., Lemenih M. Diversity of Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) and their source species in Menagesha Suba Forest. Ethiop. J. Biol. Sci. 2010;9:11–34. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woldegeorgis G., Wube T. A survey on mammals of the Yayu forest in Southwest Ethiopia. Sinet. 2012;35:135–138. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tesfaye M.A., Gardi O., Bekele T., Blaser J. Temporal variation of ecosystem carbon pools along altitudinal gradient and slope: the case of Chilimo dry afromontane natural forest, Central Highlands of Ethiopia. Journal of Ecology and Environment. 2019;43:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Engdawork A. CASCAPE–Addis Ababa University; 2015. Characterization and Classification of the Major Agricultural Soils in Cascape Intervention Woredas in the Central Highlands of Oromia Region. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sieben E.J., Khubeka S.P., Sithole S., Job N.M., Kotze D.C. The classification of wetlands: integration of top-down and bottom-up approaches and their significance for ecosystem service determination. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2018;26:441–458. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edosa T.T., Kebede T., Shumeta Z. Analysis of price efficiency of smallholder farmers in maize production in Gudeya Bila district, Oromia national regional state, Ethiopia: stochastic, dual cost approach. International Journal of Contemporary Research and Review. 2019;10:21480–21487. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friis I., Demissew S., Van Breugel P. Atlas of the potential vegetation of Ethiopia, Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes. Selskab. 2010:307. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelbessa E., Soromessa T. Interfaces of regeneration, structure, diversity and uses of some plant species in Bonga Forest: a reservoir for wild coffee gene pool. Sinet. 2008;31:121–134. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kremer A., Ronce O., Robledo‐Arnuncio J.J., Guillaume F., Bohrer G., Nathan R., Bridle J.R., Gomulkiewicz R., Klein E.K., Ritland K. Long‐distance gene flow and adaptation of forest trees to rapid climate change. Ecol. Lett. 2012;15:378–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01746.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trinh L.N., Watson J.W., Hue N.N., De N.N., Minh N., Chu P., Sthapit B.R., Eyzaguirre P.B. Agrobiodiversity conservation and development in Vietnamese home gardens. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2003;97:317–344. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weiner C.N., Werner M., Linsenmair K.E., Blüthgen N. Land use intensity in grasslands: changes in biodiversity, species composition and specialisation in flower visitor networks. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2011;12:292–299. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gallardo-Cruz J.A., Pérez-García E.A., Meave J.A. β-Diversity and vegetation structure as influenced by slope aspect and altitude in a seasonally dry tropical landscape. Landsc. Ecol. 2009;24:473–482. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Danquah J.A., Pappinen A. Analyses of socioeconomic factors influencing on-farm conservation of remnant forest tree species: evidence from Ghana. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies. 2013;5:588–602. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dastidar D.G., Basu S., Venkatraman C., Chaudhuri P., Raj P.N. Remnant vegetation in farmland-its significance in ethnobotany and local ecosystem. Plant Science Today. 2022;9(4):900–908. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baiamonte G., Domina G., Raimondo F., Bazan G. Agricultural landscapes and biodiversity conservation: a case study in Sicily (Italy) Biodivers. Conserv. 2015;24:3201–3216. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duflot R., Aviron S., Ernoult A., Fahrig L., Burel F. Reconsidering the role of ‘semi-natural habitat’in agricultural landscape biodiversity: a case study. Ecol. Res. 2015;30:75–83. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rendón-Carmona H., Martínez-Yrízar A., Balvanera P., Pérez-Salicrup D. Selective cutting of woody species in a Mexican tropical dry forest: incompatibility between use and conservation. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009;257:567–579. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paillet Y., Bergès L., Hjältén J., Ódor P., Avon C., Bernhardt‐Römermann M., Bijlsma R.J., De Bruyn L., Fuhr M., Grandin U. Biodiversity differences between managed and unmanaged forests: meta‐analysis of species richness in Europe. Conserv. Biol. 2010;24:101–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Birhanu L., Bekele T., Demissew S. Woody species composition and structure of Amoro forest in west Gojjam zone, north western Ethiopia. J. Ecol. Nat. Environ. 2018;10:53–64. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in the study will be made available on request from the corresponding author.