Abstract

Female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) and male genital schistosomiasis (MGS) are gender-specific manifestations of urogenital schistosomiasis. Morbidity is a consequence of prolonged inflammation in the human genital tract caused by the entrapped eggs of the waterborne parasite, Schistosoma (S.) haematobium. Both diseases affect the sexual and reproductive health (SRH) of millions of people globally, especially in sub-Sahara Africa (SSA). Awareness and knowledge of these diseases is largely absent among affected communities and healthcare workers in endemic countries. Accurate burden of FGS and MGS disease estimates, single and combined, are absent, mostly due to the absence of standardized methods for individual or population-based screening and diagnosis. In addition, there are disparities in country-specific FGS and MGS knowledge, research and implementation approaches, and diagnosis and treatment. There are currently no WHO guidelines to inform practice. The BILGENSA (Genital Bilharzia in Southern Africa) Research Network aimed to create a collaborative multidisciplinary network to advance clinical research of FGS and MGS across Southern African endemic countries. The workshop was held in Lusaka, Zambia over two days in November 2022. Over 150 researchers and stakeholders from different schistosomiasis endemic settings attended. Attendees identified challenges and research priorities around FGS and MGS from their respective countries. Key research themes identified across settings included: 1) To increase the knowledge about the local burden of FGS and MGS; 2) To raise awareness among local communities and healthcare workers; 3) To develop effective and scalable guidelines for disease diagnosis and management; 4) To understand the effect of treatment interventions on disease progression, and 5) To integrate FGS and MGS within other existing sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services. In its first meeting, the BILGENSA Network set forth a common research agenda across S. haematobium endemic countries for the control of FGS and MGS.

Keywords: Female genital schistosomiasis, FGS, male genital schistosomiasis, MGS, Schistosoma haematobium, research, needs, priorities, Southern Africa

Introduction

Female and male genital schistosomiasis are gender-specific chronic manifestations of urogenital schistosomiasis, a waterborne parasitic disease caused by the blood fluke Schistosoma (S.) haematobium 1, 2 . Globally, female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) affects an estimated 20–56 million girls and women, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) 2 . Male genital schistosomiasis (MGS), is 1, 3– 5 estimated to affect between 1% and 20% of males at risk 1 . Prevalence of FGS and MGS, is extrapolated from a small number of studies and underestimate the true burden of disease 1, 2 . To date, only approximately 15,000 girls and women in endemic settings have been assessed for FGS 1, 3 . MGS is also understudied and only six African countries (Madagascar, Nigeria, Egypt, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Ghana) have conducted MGS studies.

The FGS and MGS epidemiology is closely related to the distribution and transmission dynamics of the parasite S. haematobium 6, 7 . Individuals are exposed to the parasite through skin-contact with larvae (cercariae) in contaminated freshwater sources 6, 7 . Inside the human host, parasites mature into adults and reside in the blood vessels where they produce eggs 6, 7 . While some eggs are excreted in urine, others become lodged in the urogenital and genital organs, inducing granulomatous inflammation, and pathological changes 2, 8, 9 . This can result in adverse reproductive health outcomes, organ dysfunction, and reproductive morbidity 1 . Importantly, in cross-sectional studies, there was strong evidence that FGS was associated with prevalent HIV and high-risk (HR-) human papillomavirus (HPV), the primary etiological agent of cervical cancer 2, 7, 10, 11 . No epidemiological study has evaluated the association between MGS and HIV. S. haematobium induced inflammation in the male genital tract is hypothesized to increase HIV-1 viral load shedding in semen and contribute to HIV-1 transmission 12 . Work from Madagascar showed S. haematobium egg excretion in semen is associated with leukocytospermia and elevated inflammatory cytokines 13 . Further work in participants with MGS showed some evidence of a decline in semen viral load after praziquantel treatment (p = 0.08) 14 . These findings may lend biological plausibility to an association of MGS with HIV transmission, but further research is needed. Despite these significant health impacts, awareness of FGS and MGS is largely absent in S. haematobium-endemic settings.

Clinical manifestations of FGS and MGS are non-specific and often overlap with those of other sexual and reproductive health (SRH) conditions 2, 15 . Girls and women with FGS report symptoms including abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, and genital itching 2 . These are often attributed to other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) by both healthcare workers and the patients, leading to overlooking FGS and unnecessary treatment of STIs 2 . Symptoms of MGS include changes in sperm consistency, presence of blood in semen, coital and ejaculatory pain, abnormal ejaculates, and erection discomfort or dysfunction 1 . Compared to FGS, the level of morbidity associated with MGS in endemic areas remains largely understudied, with most of the evidence coming from individual case reports and post-mortem studies 1 . The stigma and misconception associated with these symptoms further contribute to the challenges of underreporting and incorrect diagnosis of MGS in endemic areas 1 .

There are no standardized methods for individual or population-based screening and diagnosis of FGS and MGS, resulting in substantial underreporting of their prevalence and associated morbidity 2, 15, 16 . Conventional diagnosis of FGS involves the use of a colposcope to visually identify FGS associated lesions 6 . This is costly and requires high-level specialized training and advanced clinical infrastructure, which are often unavailable in S. haematobium endemic settings 6 . In addition, visual diagnosis of FGS may lack specificity, as the FGS mucosal changes visually observed with colposcopy have been associated with malignancy and STIs 11, 17 . Microscopy of semen samples is currently the most accurate diagnostic method available for MGS 1 . However, its acceptance and availability in endemic communities is hindered by local beliefs and perceptions, posing significant challenges to its widespread implementation 1 . More recent research studies in SSA countries have validate closer-to the-user strategies for FGS screening and diagnosis 15 . Community-based screening and diagnostic strategies at the point-of-care could offer a promising opportunity for surveillance at scale 2, 15, 18 .

FGS and MGS treatment and control relies on schistosomiasis public health guidelines, which promote mass drug administration (MDA) of praziquantel, as preventive chemotherapy 19 . Although praziquantel effectively reduces urinary egg excretion, its efficacy in treating genital schistosomiasis remains uncertain due to lack of robust clinical evidence 2 . WHO recommends the rollout of MDA treatment strategies based on schistosomiasis population-based prevalence, using a 10% threshold to determine the targeted age groups for treatment 19 . Yet, this approach is likely to overlook individuals affected by FGS and MGS who are not included in the treatment programs, contributing to the ineffective control of FGS and MGS in endemic regions.

In November 2022, the first BILGENSA (Genital Bilharzia in Southern Africa) workshop, took place in Lusaka, Zambia. The aim of the workshop was to advance the field at country-level and as part of a wider strategy for the control of schistosomiasis worldwide. Researchers from various S. haematobium endemic countries gathered to discuss the research gaps and needs for FGS and MGS research. This paper reports the key research needs and priorities that emerged during the workshop.

The BILGENSA Research Network

The BILGENSA Research Network was a multi-country workshop held on the 9 th and 10 th of November 2022 in Lusaka, Zambia. The workshop aimed to establish a collaborative multidisciplinary network to share expertise and advance clinical research on FGS and MGS across S. haematobium endemic countries. The workshop was conducted over two days and used a hybrid approach with delegates and discussion both in-person and virtually. Over 150 researchers specializing in FGS, MGS, HIV, STIs and cervical cancer (CC) from around the globe attended the workshop. Attendees with a specialty in schistosomiasis research represented diverse research areas including disease epidemiology, diagnostics, parasitology, program implementation, and qualitative research on disease awareness. Delegates from S. haematobium endemic countries, including Zambia, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Nigeria, South Africa, Madagascar, Ghana, Malawi, and Mozambique attended the workshop in Lusaka, Zambia.

The event was hosted by Zambart ( https://www.zambart.org.zm), a Zambian research institution with extensive experience in HIV, TB, and SRH research. Sessions were held in English and translated in French for online participants. The workshop’s aim and objectives are presented in Extended data, Figure 1 20 . The workshop was conducted over two days ( Extended data, Text 1). Day one comprised of didactic sessions in which participants presented in-country FGS and MGS research, as well as sharing their country’s perceived research priorities, challenges, and needs. The afternoon sessions were interactive with participants grouped in their respective countries to discuss country-specific research priorities ( Extended data, Text 1). At the conclusion of Day One, outcomes of the interactive session were shared with the wider group. During Day Two, participants discussed the diagnostic opportunities and challenges for genital schistosomiasis and integration within SRH services. Specific interventions suggested included integrating FGS within existing cervical cancer, and FGS/MGS within HIV care screening programs ( Extended data, Figure 1). We identified common themes that emerged during the workshop.

Research needs and priorities identified in the workshop

During the BILGENSA workshop, endemic countries reported being at different stages in advancing FGS and MGS research. Despite these differences, common themes identified across countries include lack of expertise in identifying and correctly diagnosing FGS/MGS, and lack of disease awareness. The scarcity of available diagnostics and specialized equipment and health facilities infrastructure are notable hurdles. Another limitation is the limited number of trained clinicians available with specific expertise in FGS screening and identification. All country delegates reported limited availability of routine treatment with praziquantel, a drug not commonly found in clinics in SSA 21 . Further common issues include lack of financial resources from the ministry of health (MoH) to support community education and mobilization. There is a clear need for enhanced collaboration across countries and sectors.

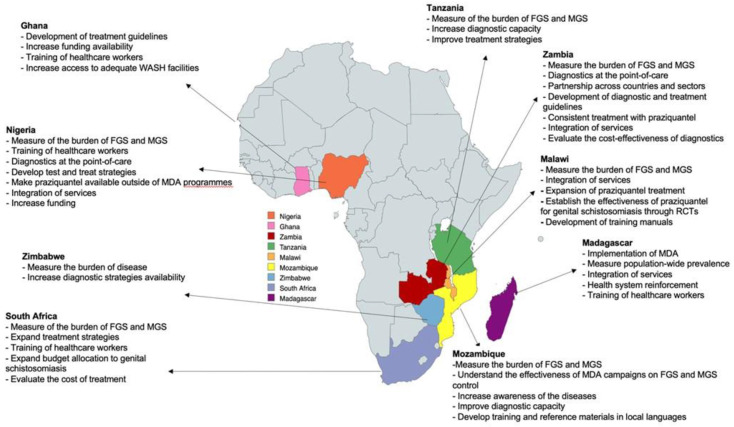

Following the identification of the above challenges, the research priorities, and strategies to address them set forth by country delegates, as follows ( Figure 1/ Table1).

Figure 1. Map showing the countries represented during the BILGENSA Research Network and their research needs and priorities to advance research on female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) and male genital schistosomiasis (MGS).

Table 1. Summary of the recommendations for future research discussed during the BILGENSA Research Network to address the female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) and male genital schistosomiasis (MGS) research needs and priorities in endemic settings.

| Research need | Recommendations for future research | |

|---|---|---|

| FGS | MGS | |

|

Raising awareness and

knowledge |

Provide further training to healthcare workers

and patients on etiology, transmission, symptoms, screening, and management |

Develop and disseminate educational

and training material |

|

Improving diagnostic

capabilities |

Validate and implement decentralized and field-

deployable screening and diagnostic strategies for community-based surveillance at scale. Evaluate the scalability and cost-effectiveness of different screening and diagnostic strategies |

Develop and validate accessible,

scalable, and low-cost molecular test. |

|

Developing standardized

treatment guidelines |

Conduct randomized control trials (RCTs) to evaluate the effectiveness of praziquantel for FGS

and MGS Develop and implement FGS/MGS specific treatment guidelines. |

|

|

Integration of SRH

screening strategies |

Evaluate the integration of FGS within the wider

schistosomiasis and SRH control guidelines. |

Identify potential opportunities for

integration of MGS into ongoing HIV interventions |

|

Surveillance and

monitoring |

Develop routine and integrated surveillance of FGS

Increase collaborative efforts and financial resources available to implement and expand FGS and MGS control strategies. |

|

Raising knowledge and awareness of FGS and MGS

During the workshop, delegates highlighted the urgent need to increase awareness and education on FGS and MGS in endemic settings through community engagement and sensitization programs. Community-wide campaigns should be initiated to disseminate information on the diseases’ etiology, modes of transmission, symptoms, and prevention strategies. These campaigns can leverage existing community structures and engagement programs, to ensure all members of the community are included. It is imperative to provide additional training to healthcare workers in S. haematobium endemic regions on the acquisition, screening, and treatment of FGS and MGS. This training could be integrated into ongoing educational programs for Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) and SRH 3, 22 . The development of training manuals, standard operating procedures (SOPs) and standardized guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of FGS and MGS are necessary to ensure effective disease control. An FGS training document for the community and healthcare workers, as well as a manual about raising awareness on FGS using drama, have recently been developed as a first step towards increasing education about and information on the disease, respectively 23– 25 . In contrast, the lack of knowledge and awareness of MGS has not yet been adequately addressed.

Recent qualitative research in Cameroon, Tanzania, and Ghana highlighted a significant gap in knowledge and awareness on FGS among communities and healthcare workers 26– 28 . Girls and women have reported limited knowledge on the mode of transmission, symptoms, and potential risk factors associated with FGS 26– 28 . Simultaneously, healthcare workers often incorrectly diagnosed FGS, confusing its symptoms with those of other STIs 26– 28 . This results in the unnecessary STI treatment and contributes to the stigma faced by affected individuals seeking care in public health facilities 2 . Immediate action is necessary to implement further programs aimed at raising awareness and disseminating information and education on FGS among affected populations and healthcare workers, to effectively control and manage schistosomiasis. Further work is needed to develop educational material for MGS.

Improving diagnostic capabilities in-country

Many countries reported limited diagnostic capacity for FGS and MGS with some (such as Nigeria, Tanzania, and Malawi) relying solely on S. haematobium antigen, antibody, and pathogen-based diagnosis. Although these methods serve as a useful proxy, they have reduced sensitivity for FGS and MGS diagnosis as they do not confirm genital involvement 1, 2 . An additional common challenge identified across countries was the limited number of clinicians trained in colposcopy to identify FGS specific lesions, leading to a bottleneck in diagnosis.

Given the limited resources available in S. haematobium endemic countries, the BILGENSA Research Network highlighted the importance of decentralizing diagnostic methods for FGS. This includes bringing screening closer to the user for community-based surveillance at scale 2 . Hand-held colposcopy has been proposed as a more scalable diagnostic strategy compared to traditional colposcopy 2, 17, 29 . Hand-held colposcopes can be operated by primary healthcare workers (midwives), are mobile, cheaper and, rechargeable 2, 17, 29 . Furthermore, novel approaches for analysis of colposcopic images include using artificial intelligence visual reading algorithms to overcome some of the FGS diagnostic barriers including the lack of trained clinicians to identify FGS lesions and the subjectivity of FGS visual diagnosis 29 . Community-based screening and testing using home-based self-sampling and point-of-care (POC) diagnostics has also been proposed as a closer-to-the-user strategy for surveillance at scale 15 . Previous studies have shown the feasibility, acceptability, and cost-effectiveness of home-based genital self-sampling for cervical cancer screening, which has the potential to increase coverage by reaching women less likely to attend screening in clinic. A recent study in Zambia validated the use of genital self-sampling as a feasible, accurate, and feasible method for community-based screening of FGS 15, 30 . As part of the study they successfully piloted a rapid and portable recombinase polymerase assay (RPA) for FGS diagnosis 15, 31 . The RPA is a POC molecular assay which has high specificity, meaning detecting S. haematobium DNA in genital specimen confirms an FGS diagnosis 31, 32 . The promising results from these studies emphasize the need for further applications of these screening and diagnostic techniques across different endemic settings.

In contrast to FGS, there is limited research on novel MGS screening and diagnostic methods 5 . Accessible and low-cost molecular tests are urgently needed to address the diagnostic challenges associated with MGS. For both FGS and MGS, future research should evaluate the cost-effectiveness, scalability, and performance of field-deployable molecular assays designed for point-of-care applications. These efforts are crucial for advancing the implementation of decentralized diagnostic strategies, ultimately contributing to more effective and accessible community-based surveillance of FGS and MGS.

Developing standardized treatment guidelines

Treatment recommendations for FGS and MGS follow schistosomiasis public health guidelines, which promote mass drug administration (MDA) of praziquantel (typically offered at 40mg/kg), as preventive chemotherapy 2 . Praziquantel is an effective treatment for urinary schistosomiasis, but the evidence on its effectiveness for treating FGS and MGS remains limited. To date, only a small number of observational studies evaluated the performance of praziquantel for the treatment of FGS, and there have been no studies on its effectiveness for MGS 2 . In endemic settings, treatment programs are determined by the schistosomiasis prevalence 19 . The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends annual praziquantel treatment for all individuals aged two years and older in communities where the prevalence of egg-patent Schistosoma infection is 10% or greater 19 . In contrast, for communities with a prevalence below 10%, a test-and-treat strategy is advised 19 . Despite these guidelines, some countries, such as Mozambique and Tanzania, reported that MDA programs exclusively target school-aged-children (SAC), leaving older individuals and adults with limited access to treatment. Additionally, access to and uptake of praziquantel still remain a challenge 33

During the BILGENSA workshop, participants highlighted the need to expand FGS and MGS treatment strategies. There was a call for randomized control trials (RCTs) to evaluate the effectiveness of praziquantel for the treatment of FGS and MGS 2 . Results from these trials will play a pivotal role in the development of effective treatment protocols and guidelines 2 . Mapping surveys should also be conducted to assess the impact of MDA programs on the prevalence of FGS and MGS in endemic settings and to facilitate an assessment of MDA coverage in rural areas and among hard-to-reach-populations. These efforts are critical for improving treatment accessibility and effectiveness of control strategies in endemic regions.

Integration of SRH screening strategies

FGS and MGS surveillance are not yet included in wider schistosomiasis or SRH control strategies 2, 3 . Existing HIV and cervical cancer programs have been identified as opportunities to integrate FGS surveillance into the SRH agenda 2, 3, 18 . Healthcare delivery systems already in place for HIV and cervical cancer prevention and control can be used to increase access to FGS screening and treatment services 2, 3, 18 . An integrated home-based screening and testing package for different SRH conditions, including FGS, could be made available to individuals in S. haematobium endemic settings 2, 15 . This is currently being validated in an ongoing study in Zambia which aims to assess the feasibility and acceptability of an integrated home-based approach for multi-pathogen genital screening, including FGS, HPV, Trichomonas and HIV 34 . In addition, FGS screening using hand-held colposcopy could be integrated into the existing cervical cancer screening programs 17, 35 . In contrast, for men, there is still a need to identify potential opportunities for integration of MGS screening and control into ongoing HIV interventions. An integrated approach presents an opportunity to increase screening coverage of genital schistosomiasis while developing comprehensive policy frameworks that addresses the disease burden of FGS, MGS, HIV, and cervical cancer. Ultimately, this will accelerate the attainment of universal health coverage by strengthening different levels of the health system.

Surveillance and monitoring

FGS has been financially neglected, resulting in limited funding available for advancing research and control of these diseases across endemic settings. The shift from campaign-based programs to routine and integrated surveillance of FGS requires further financial resources and sustainable collaborations between sectors. Across countries, participants of the BILGENSA Research Network highlighted the need to increase collaborative efforts and financial resources available to implement and expand FGS control strategies. SRH programs have been proposed as a plausible platform for integration of FGS surveillance within national health systems and information systems. This still requires improved FGS diagnostics, and better understanding of the spatial distribution of disease.

Conclusions

FGS and MGS are specific genital tract manifestations of urogenital schistosomiasis. These diseases have been largely neglected and under-researched in S. haematobium endemic countries. The BILGENSA Research Network was created to bring together researchers and experts from different Southern African countries working on FGS, MGS, within the wider SRH landscape. Common key priorities included improving awareness and knowledge around genital schistosomiasis, increasing surveillance-at-scale by developing decentralized screening and diagnostic guidelines, and exploring the effectiveness of integration of control strategies within the broader schistosomiasis and SRH agendas. These actions are paramount for the control and elimination of these diseases in affected communities.

Acknowledgments

The BILGENSA Research Network initial workshop was hosted by Zambart with partners from the London School of School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), Global Schistosomiasis Alliance (GSA) and Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC). The online event was organized by the GSA who also facilitated the French translation of the event as well as all the speaker’s slides. The workshop and travel grants were funded by the Wellcome Trust Strategic Award, ISSF-3 to Prof. Bustinduy.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Wellcome [204928, <a href=https://doi.org/10.35802/204928>https://doi.org/10.35802/204928</a>].

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; peer review: 1 approved, 3 approved with reservations]

Data availability

Underlying data

No underlying data are associated with this study.

Extended data

Zenodo: The first BILGENSA Research Network Workshop in Zambia; Identifying Research Priorities, Challenges and Needs in Genital Bilharzia in Southern Africa. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11930644 20

This project contains the following extended data:

-

-

Supplementary document_12.06.2024.docx (Figure 1: Schematic figure presenting the aims and objectives of the BILGENSA Research Network, Text 1: Description of the proposed activities conducted during the BILGENSA Research Network, Table 1: Agenda for the BILGENSA Research Network)

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0).

References

- 1. Kayuni S, Lampiao F, Makaula P, et al. : A systematic review with epidemiological update of Male Genital Schistosomiasis (MGS): a call for integrated case management across the health system in sub-Saharan Africa. Parasite Epidemiol Control. 2019;4: e00077. 10.1016/j.parepi.2018.e00077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bustinduy AL, Randriansolo B, Sturt AS, et al. : An update on Female and Male Genital Schistosomiasis and a call to integrate efforts to escalate diagnosis, treatment and awareness in endemic and non-endemic settings: the time is now. Adv Parasitol. Elsevier,2022;115:1–44. 10.1016/bs.apar.2021.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Engels D, Hotez PJ, Ducker C, et al. : Integration of prevention and control measures for Female Genital Schistosomiasis, HIV and cervical cancer. Bull World Health Organ. 2020;98(9):615–24. 10.2471/BLT.20.252270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Makene T, Zacharia A, Haule S, et al. : Sexual and reproductive health among men with genital schistosomiasis in southern Tanzania: a descriptive study. Standley CJ editor. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2024;4(3): e0002533. 10.1371/journal.pgph.0002533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kayuni SA, Alharbi MH, Shaw A, et al. : Detection of Male Genital Schistosomiasis (MGS) by real-time TaqMan® PCR analysis of semen from fishermen along the southern shoreline of Lake Malawi. Heliyon. 2023;9(7): e17338. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kjetland EF, Leutscher PDC, Ndhlovu PD: A review of Female Genital Schistosomiasis. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28(2):58–65. 10.1016/j.pt.2011.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sturt AS, Webb EL, Francis SC, et al. : Beyond the barrier: Female Genital Schistosomiasis as a potential risk factor for HIV-1 acquisition. Acta Trop. 2020;209: 105524. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2020.105524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Downs JA, Kabangila R, Verweij JJ, et al. : Detectable urogenital schistosome DNA and cervical abnormalities 6 months after single-dose praziquantel in women with Schistosoma haematobium infection. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18(9):1090–6. 10.1111/tmi.12154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wall KM, Kilembe W, Vwalika B, et al. : Schistosomiasis is associated with incident HIV transmission and death in Zambia. Bustinduy AL, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(12): e0006902. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kjetland EF, Ndhlovu PD, Gomo E, et al. : Association between genital schistosomiasis and HIV in rural Zimbabwean women. AIDS. 2006;20(4):593–600. 10.1097/01.aids.0000210614.45212.0a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kjetland EF, Ndhlovu PD, Mduluza T, et al. : Simple clinical manifestations of genital Schistosoma Haematobium infection in rural Zimbabwean women. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72(3):311–9. 10.4269/ajtmh.2005.72.311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kayuni SA, Abdullahi A, Alharbi MH, et al. : Prospective pilot study on the relationship between seminal HIV-1 shedding and genital schistosomiasis in men receiving antiretroviral therapy along Lake Malawi. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1): 14154. 10.1038/s41598-023-40756-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leutscher PDC, Pedersen M, Raharisolo C, et al. : Increased prevalence of leukocytes and elevated cytokine levels in semen from Schistosoma haematobium-infected individuals. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(10):1639–47. 10.1086/429334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Midzi N, Mduluza T, Mudenge B, et al. : Decrease in seminal HIV-1 RNA load after praziquantel treatment of urogenital schistosomiasis coinfection in HIV-positive men-an observational study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(4): ofx199. 10.1093/ofid/ofx199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sturt AS, Webb EL, Phiri CR, et al. : Genital self-sampling compared with cervicovaginal lavage for the diagnosis of Female Genital Schistosomiasis in Zambian women: the BILHIV study. Cools P, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(7): e0008337. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pillay P, Downs JA, Changalucha JM, et al. : Detection of Schistosoma DNA in genital specimens and urine: a comparison between five female African study populations originating from S. haematobium and/or S. mansoni endemic areas. Acta Trop. 2020;204: 105363. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2020.105363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sturt A, Bristowe H, Webb E, et al. : Visual diagnosis of Female Genital Schistosomiasis in Zambian women from hand-held colposcopy: agreement of expert image review and association with clinical symptoms [version 2; peer review: 6 approved]. Wellcome Open Res. 2023;8:14. 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.18737.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lamberti O, Bozzani F, Kiyoshi K, et al. : Time to bring Female Genital Schistosomiasis out of neglect. Br Med Bull. 2024;149(1):45–59. 10.1093/bmb/ldad034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. World Health Organization: WHO guideline on control and elimination of human schistosomiasis. [PubMed]

- 20. Lamberti O, Ndubani R, Bustinduy A, et al. : The first BILGENSA Research Network Workshop in Zambia; Identifying Research Priorities, Challenges and Needs in Genital Bilharzia in Southern Africa.In: Wellcome Open Research. Zenodo. [Dataset].2024. 10.5281/zenodo.11930644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21. World Health Organization: The selection and use of essential medicines 2023" executive summary of the report of the 24th WHO expert committee on the selection and use of essential medicine.2023. Reference Source.

- 22. UNAIDS: No more neglect: Female Genital Schistosomiasis and HIV.2019. Reference Source

- 23. Countdown: Health worker training guide for Female Genital Schistosomiasis (FGS) in Primary Health Care.Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, UK2021. Reference Source

- 24. Jacobson J, Pantelias A, Williamson M, et al. : Addressing a silent and neglected scourge in sexual and reproductive health in Sub-Saharan Africa by development of training competencies to improve prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of Female Genital Schistosomiasis (FGS) for health workers. Reprod Health. 2022;19(1): 20. 10.1186/s12978-021-01252-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blantyre Institute for Community Outreach in Malawi, Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences in Tanzania, Zambart in Zambia: Using Drama to Raise Awareness About Female Genital Schistosomiasis.2022. Reference Source

- 26. Masong MC, Wepnje GB, Marlene NT, et al. : Female Genital Schistosomiasis (FGS) in Cameroon: A formative epidemiological and socioeconomic investigation in eleven rural fishing communities.Tappis H, editor. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2021;1(10): e0000007. 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yirenya-Tawiah D, Amoah C, Apea-Kubi K, et al. : A survey of Female Genital Schistosomiasis of the lower reproductive tract in the volta basin of Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2011;45(1):16–21. 10.4314/gmj.v45i1.68917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ursini T, Scarso S, Mugassa S, et al. : Assessing the prevalence of Female Genital Schistosomiasis and comparing the acceptability and performance of health worker-collected and self-collected cervical-vaginal swabs using PCR testing among women in North-Western Tanzania: The ShWAB study.Ekpo UF, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023;17(7): e0011465. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0011465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Holmen SD, Kleppa E, Lillebø K, et al. : The First Step Toward Diagnosing Female Genital Schistosomiasis by computer image analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93(1):80–86. 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rutty Phiri C, Sturt AS, Webb EL, et al. : Acceptability and feasibility of genital self-sampling for the diagnosis of Female Genital Schistosomiasis: a cross-sectional study in Zambia [version 2; peer review: 2 approved]. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5:61. 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15482.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Archer J, Patwary FK, Sturt AS, et al. : Validation of the isothermal Schistosoma haematobium Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) assay, coupled with simplified sample preparation, for diagnosing Female Genital Schistosomiasis using cervicovaginal lavage and vaginal self-swab samples.Santos VS, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16(3): e0010276. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Archer J, Barksby R, Pennance T, et al. : Analytical and Clinical Assessment of a Portable, Isothermal Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) Assay for the Molecular Diagnosis of Urogenital Schistosomiasis. Molecules. 2020;25(18): 4175. 10.3390/molecules25184175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tuhebwe D, Bagonza J, Kiracho EE, et al. : Uptake of Mass Drug Administration programme for schistosomiasis control in Koome Islands, Central Uganda.Garcia-Lerma JG, editor. PLoS One. 2015;10(4): e0123673. 10.1371/journal.pone.0123673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shanaube K, Ndubani R, Kelly H, et al. : The Zipime-Weka-Schista study protocol: a longitudinal cohort study of an integrated home-based approach for genital multi-pathogen screening in women, including Female Genital Schistosomiasis, HPV Trichomonas and HIV in Zambia.Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Søfteland S, Sebitloane MH, Taylor M, et al. : A systematic review of handheld tools in lieu of colposcopy for cervical neoplasia and Female Genital Schistosomiasis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;153(2):190–199. 10.1002/ijgo.13538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]