Abstract

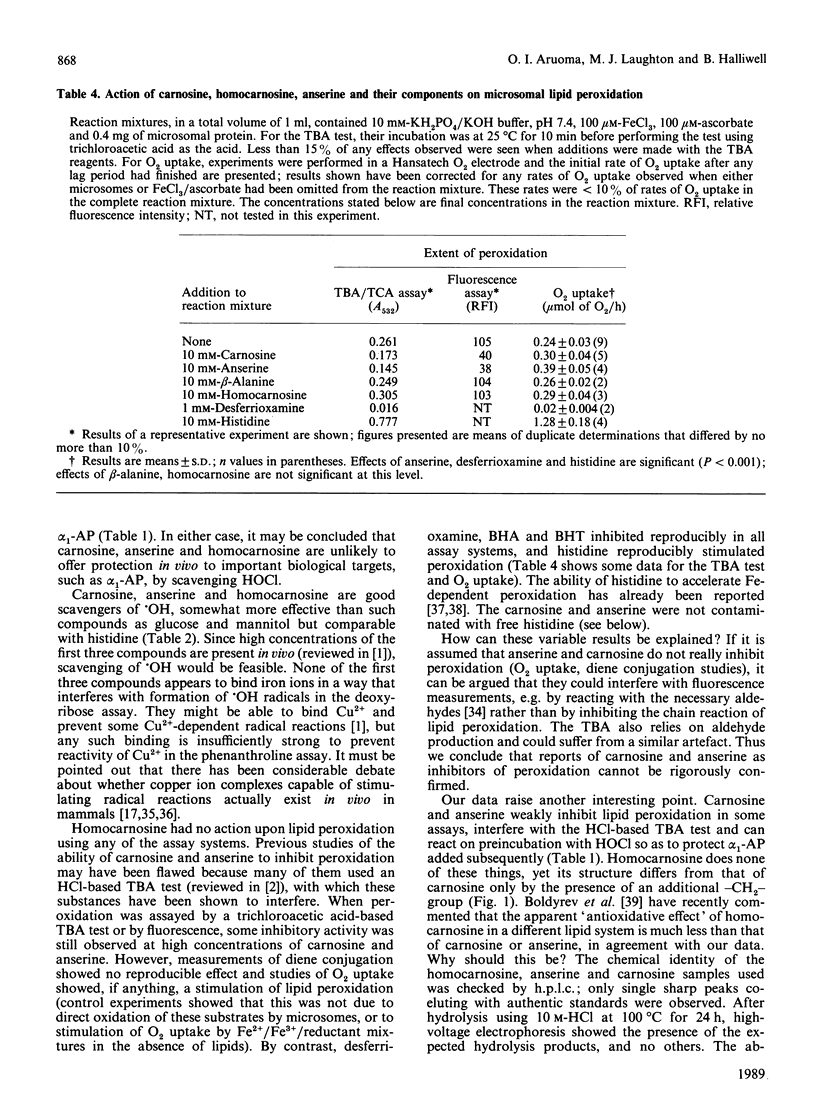

Carnosine, homocarnosine and anserine have been proposed to act as antioxidants in vivo. Our studies show that all three compounds are good scavengers of the hydroxyl radical (.OH) but that none of them can react with superoxide radical, hydrogen peroxide or hypochlorous acid at biologically significant rates. None of them can bind iron ions in ways that interfere with 'site-specific' iron-dependent radical damage to the sugar deoxyribose, nor can they restrict the availability of Cu2+ to phenanthroline. Homocarnosine has no effect on iron ion-dependent lipid peroxidation; carnosine and anserine have weak inhibitory effects when used at high concentrations in some (but not all) assay systems. However, the ability of these compounds to interfere with a commonly used version of the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) test may have led to an overestimate of their ability to inhibit lipid peroxidation in some previous studies. By contrast, histidine stimulated iron ion-dependent lipid peroxidation. It is concluded that, because of the high concentrations present in vivo, carnosine and anserine could conceivably act as physiological antioxidants by scavenging .OH, but that they do not have a broad spectrum of antioxidant activity, and their ability to inhibit lipid peroxidation is not well established. It may be that they have a function other than antioxidant protection (e.g. buffering), but that they are safer to accumulate than histidine, which has a marked pro-oxidant action upon iron ion-dependent lipid peroxidation. The inability of homocarnosine to react with HOCl, interfere with the TBA test or affect lipid peroxidation systems in the same way as carnosine is surprising in view of the apparent structural similarity between these two molecules.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aruoma O. I., Halliwell B., Hoey B. M., Butler J. The antioxidant action of taurine, hypotaurine and their metabolic precursors. Biochem J. 1988 Nov 15;256(1):251–255. doi: 10.1042/bj2560251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruoma O. I., Halliwell B. The iron-binding and hydroxyl radical scavenging action of anti-inflammatory drugs. Xenobiotica. 1988 Apr;18(4):459–470. doi: 10.3109/00498258809041682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp C., Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase: improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1971 Nov;44(1):276–287. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(71)90370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldyrev A. A., Dupin A. M., Bunin AYa, Babizhaev M. A., Severin S. E. The antioxidative properties of carnosine, a natural histidine containing dipeptide. Biochem Int. 1987 Dec;15(6):1105–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldyrev A. A., Dupin A. M., Pindel E. V., Severin S. E. Antioxidative properties of histidine-containing dipeptides from skeletal muscles of vertebrates. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 1988;89(2):245–250. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(88)90218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buege J. A., Aust S. D. Microsomal lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1978;52:302–310. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)52032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler J., Koppenol W. H., Margoliash E. Kinetics and mechanism of the reduction of ferricytochrome c by the superoxide anion. J Biol Chem. 1982 Sep 25;257(18):10747–10750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl T. A., Midden W. R., Hartman P. E. Some prevalent biomolecules as defenses against singlet oxygen damage. Photochem Photobiol. 1988 Mar;47(3):357–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1988.tb02737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duane P., Peters T. J. Serum carnosinase activities in patients with alcoholic chronic skeletal muscle myopathy. Clin Sci (Lond) 1988 Aug;75(2):185–190. doi: 10.1042/cs0750185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esterbauer H., Koller E., Slee R. G., Koster J. F. Possible involvement of the lipid-peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal in the formation of fluorescent chromolipids. Biochem J. 1986 Oct 15;239(2):405–409. doi: 10.1042/bj2390405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridovich I. Biological effects of the superoxide radical. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1986 May 15;247(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(86)90526-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutteridge J. M. Aspects to consider when detecting and measuring lipid peroxidation. Free Radic Res Commun. 1986;1(3):173–184. doi: 10.3109/10715768609083149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutteridge J. M. Copper-phenanthroline-induced site-specific oxygen-radical damage to DNA. Detection of loosely bound trace copper in biological fluids. Biochem J. 1984 Mar 15;218(3):983–985. doi: 10.1042/bj2180983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutteridge J. M. Ferrous-salt-promoted damage to deoxyribose and benzoate. The increased effectiveness of hydroxyl-radical scavengers in the presence of EDTA. Biochem J. 1987 May 1;243(3):709–714. doi: 10.1042/bj2430709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutteridge J. M., Quinlan G. J., Clark I., Halliwell B. Aluminium salts accelerate peroxidation of membrane lipids stimulated by iron salts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985 Jul 31;835(3):441–447. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(85)90113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutteridge J. M. Reactivity of hydroxyl and hydroxyl-like radicals discriminated by release of thiobarbituric acid-reactive material from deoxy sugars, nucleosides and benzoate. Biochem J. 1984 Dec 15;224(3):761–767. doi: 10.1042/bj2240761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutteridge J. M., Richmond R., Halliwell B. Inhibition of the iron-catalysed formation of hydroxyl radicals from superoxide and of lipid peroxidation by desferrioxamine. Biochem J. 1979 Nov 15;184(2):469–472. doi: 10.1042/bj1840469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B., Gutteridge J. M., Aruoma O. I. The deoxyribose method: a simple "test-tube" assay for determination of rate constants for reactions of hydroxyl radicals. Anal Biochem. 1987 Aug 15;165(1):215–219. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B., Gutteridge J. M. Oxygen free radicals and iron in relation to biology and medicine: some problems and concepts. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1986 May 1;246(2):501–514. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(86)90305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. Lipid peroxidation in vivo and in vitro in relation to atherosclerosis: some fundamental questions. Agents Actions Suppl. 1988;26:223–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. Use of desferrioxamine as a 'probe' for iron-dependent formation of hydroxyl radicals. Evidence for a direct reaction between desferal and the superoxide radical. Biochem Pharmacol. 1985 Jan 15;34(2):229–233. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(85)90129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoey B. M., Butler J., Halliwell B. On the specificity of allopurinol and oxypurinol as inhibitors of xanthine oxidase. A pulse radiolysis determination of rate constants for reaction of allopurinol and oxypurinol with hydroxyl radicals. Free Radic Res Commun. 1988;4(4):259–263. doi: 10.3109/10715768809055151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohen R., Yamamoto Y., Cundy K. C., Ames B. N. Antioxidant activity of carnosine, homocarnosine, and anserine present in muscle and brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 May;85(9):3175–3179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.9.3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. M., Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). J Biol Chem. 1969 Nov 25;244(22):6049–6055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Dowd J. J., Robins D. J., Miller D. J. Detection, characterisation, and quantification of carnosine and other histidyl derivatives in cardiac and skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988 Nov 17;967(2):241–249. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(88)90015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan G. J., Halliwell B., Moorhouse C. P., Gutteridge J. M. Action of lead(II) and aluminium (III) ions on iron-stimulated lipid peroxidation in liposomes, erythrocytes and rat liver microsomal fractions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988 Sep 23;962(2):196–200. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(88)90159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharaf El Din M., Schaur R. J., Schauenstein E. Uptake of ferrous iron histidinate, a promoter of lipid peroxidation, by Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988 Sep 2;962(1):37–41. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(88)90092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya H., Iwata K., Ohkawa Y., Inui N. Histidine increases the frequency of chromosomal aberrations induced by the xanthine oxidase-hypoxanthine system in V79 cells. Toxicol Lett. 1985 Nov;28(2-3):117–123. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(85)90019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasil M., Halliwell B., Grootveld M., Moorhouse C. P., Hutchison D. C., Baum H. The specificity of thiourea, dimethylthiourea and dimethyl sulphoxide as scavengers of hydroxyl radicals. Their protection of alpha 1-antiproteinase against inactivation by hypochlorous acid. Biochem J. 1987 May 1;243(3):867–870. doi: 10.1042/bj2430867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasil M., Halliwell B., Hutchison D. C., Baum H. The antioxidant action of human extracellular fluids. Effect of human serum and its protein components on the inactivation of alpha 1-antiproteinase by hypochlorous acid and by hydrogen peroxide. Biochem J. 1987 Apr 1;243(1):219–223. doi: 10.1042/bj2430219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasil M., Halliwell B., Moorhouse C. P., Hutchison D. C., Baum H. Biologically-significant scavenging of the myeloperoxidase-derived oxidant hypochlorous acid by some anti-inflammatory drugs. Biochem Pharmacol. 1987 Nov 15;36(22):3847–3850. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(87)90448-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss S. J. Oxygen, ischemia and inflammation. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1986;548:9–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills E. D. Lipid peroxide formation in microsomes. The role of non-haem iron. Biochem J. 1969 Jun;113(2):325–332. doi: 10.1042/bj1130325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler P., Schaur R. J., Schauenstein E. Selective promotion of ferrous ion-dependent lipid peroxidation in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells by histidine as compared with other amino acids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984 Dec 6;796(3):226–231. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(84)90121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winyard P. G., Pall H., Lunec J., Blake D. R. Non-caeruloplasmin-bound copper ('phenanthroline copper') is not detectable in fresh serum or synovial fluid from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Biochem J. 1987 Oct 1;247(1):245–246. doi: 10.1042/bj2470245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]