Abstract

This study empirically examined the threshold effect of exchange rate pass-through (ERPT) on inflation in Kenya, while augmenting the exchange rate depreciation in the monetary policy rate using the Taylor rule. The monthly time series data spanning January 2005 to November 2023 was collected for analysis, in which the non-linear threshold autoregressive (TAR) model was employed as the main econometric model. This study's ERPT results reveal that, exchange rate depreciation has positive and significant effect on inflation only when it raises above the monthly threshold level of 0.51 %. In contrast, the Taylor rule analysis results reveal that the exchange rate depreciation has a positive and significant effect the monetary policy rate regardless of the threshold level of 0.67 %. Therefore, keeping domestic currency depreciation below a monthly growth rate of 0.51 % will control the pass-through effect on inflation, and the exchange rate depreciation at any level should always act as a reaction function for the monetary policy rate setting. This study also found that the relationship between exchange rate depreciation and inflation, as well as monetary policy rate is non-linear, which implies a greater pass-through effect when exchange rate depreciation is high. Therefore, we recommend the monetary authority in Kenya to pay attention to the depreciation of the exchange rate depreciation at any level when adjusting the policy rate to tame inflation.

Keywords: Exchange rate, Inflation, Threshold auto-regressive model, Kenya

1. Introduction

In the realm of economic dynamics, managing exchange rate fluctuation remains critical given that it often shapes the macroeconomic performance of a nation. In Kenya, just like other developing countries, the performance of the Kenyan shilling against major international currencies such as the US dollar, British Pound, and Euro is believed to affect the domestic policies due to overdependence on imports which is dominated by foreign currency [1]. Generally, it is believed that exchange rate depreciation could be a major driver of the domestic inflation via a pass-through effect. This is so because as domestic currency depreciates, more of it is required to purchase the same amount of goods or services in the international markets which makes imports to be sold at higher prices in the domestic markets leading to inflation [2]. This is the proposition of the purchasing power parity (PPP) theory which states that, exchange rate fluctuation tends to have severe negative effect on macroeconomic stability when a country's trade is dominated by foreign currency due to depreciation of the weaker currency [3].

The exchange rate pass-through effect refers to the responsiveness of domestic or international prices (inflation) to the fluctuations in the exchange rate, usually measured as a percentage change in inflation due to unit change in the nominal exchange rate [4]. With the recent increase in globalization, all world open economies have become dependent on one another. This means that financial liberalization policy in one country will always tend to expose other free market economies to economic turmoil and fluctuations in macroeconomic variables such as inflation [5]. Therefore, monitoring the movement of the local currencies in developing countries that are net importers is crucial in a bid to achieve macroeconomic stability [3]. The concern of macroeconomic pass through effect of exchange rate movements in developing countries can be traced back to early 1970s when most countries accumulated interest on internationally borrowed funds due to change in capital flow between economies leading to inflation phenomena [6]. Although it is argued that it is possible for domestic firms to cushion themselves against exchange rate fluctuation through currency hedging, this can only happen in the short run and is not sustainable in the medium and the long-run which still exposes them to exchange rate depreciation risks [7]. The medium and long-run exchange rate depreciation affect firms’ investments as well as production decisions which tempers with the flow of goods and services causing demand pull inflation [8]. Therefore, knowing the exchange rate pass through effect on the main macroeconomic variables would help a great deal in combating its adverse effects in an economy.

In managing exchange depreciation and inflation rate fluctuations, most countries, including Kenya, operate a floating exchange rate monetary policy where the value of local currency is determined through the forces of demand and supply in the foreign exchange rate markets. It is only, in rare special cases where central banks intervene to prevent excess exchange rate volatility through either depleting foreign reserves or constituting policies that limit the outflow of a stronger foreign currency such as dollar. On the other hand, inflation targeting is a common phenomenon among open economies because of its diverse sources, which varies from local to foreign factors. In Kenya for example, the CBK formally adopted the inflation target as a monetary policy framework in 2013, where the target inflation rate was set at 5 % with a standard deviation of 2.5 %. According to this policy, the inflation rate in the country was allowed to move down to as low as 2.5 % and up to as high as 7.5 % without being considered a threat to the country's macroeconomic stability [9]. This study covers the period before and after the adoption of the inflation target to see whether this policy affects the management of the inflation rate.

There exist a number of studies, which have analyzed the exchange rate pass-through effect on inflation both at local and in the international scope. However, most the studies are based on developed economies with advanced market and financial systems to manage the effect of exchange rate fluctuation on macroeconomic variables such as inflation. For instance, studies such as [5,[10], [11], [12], [13]], have all been conducted in advanced economies. Among the developing economies in Africa and Kenya in particular, studies such as [[14], [15], [16], [17], [18]] are available, but less has been done especially in designing the optimal exchange rate depreciation level below which it does not harm macroeconomic variables. This is important since it is evident that exchange rate depreciation below certain level is desired in the economy to simulate export and foreign direct investment inflow. Similarly, there has been little attempt to check on the possibility of the non-linear relationship between exchange rate and inflation among developing countries such that the effect tends to be higher when the depreciation rate goes beyond certain level. In addition, there is yet an attempt to augment Taylor rule with exchange rate fluctuation to enable the Central Bank of Kenya control inflation by considering exchange rate trends while setting monetary policy rate. These three points form the basis of our study.

This study makes the following contribution in the field of research. First, it examines the exchange rate pass-through effect on inflation using the most current Kenyan data up to November 2023, which updates on the available literature. The second the study considers a threshold effect analysis to help design an optimal level of exchange rate depreciation beyond which there will be need to control movement of the Kenya shilling against the US dollar other than relying on market forces. Third, the current study uses Wald test to determine whether the pass-through effect between exchange rate depreciation and inflation is non-linear. This is necessary to determine whether a unit increase in exchange rate is likely to cause more inflation when it goes beyond certain critical level in order to design appropriate policy control. Lastly, the current study uses Taylor rule to augment the exchange rate fluctuation and monetary policy rate. This will enable the Central Bank of Kenya to control for inflation by designing monetary policy rate while simultaneously observing exchange rate movements.

Kenya was selected for the purpose of this study based on the following stylized facts. First, the nominal exchange rate in the country has been increasing, implying depreciation of the Kenyan shilling against the US dollar, which poses serious domestic macroeconomic challenges. For instance, according to reports from the Central Bank of Kenya, the country continued to experience exchange rate depreciation over a long time. The most recent one and highest in history being in the financial year 2023/24, which saw the Kenya shilling lose more than 30 % of its value between November 2022 and November 2023. The exchange rate stood at KES 152.04 per US dollar in November 2023 against KES 121.06 in the same period in 2022 [19]. The continued weakening of the Kenya shilling has made the government seek alternatives to reduce pressure on the dollar such as the government-to-government (G-to-G) fuel deal between Kenya and the governments of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates countries. The deal was to see the Kenyan government import crude oil from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates using local currency to reduce demand pressure on the dollar [20].

The trend in the exchange rate from January 2005 to November 2023 can be visualized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The trend in Kenya's exchange rate against US dollar.

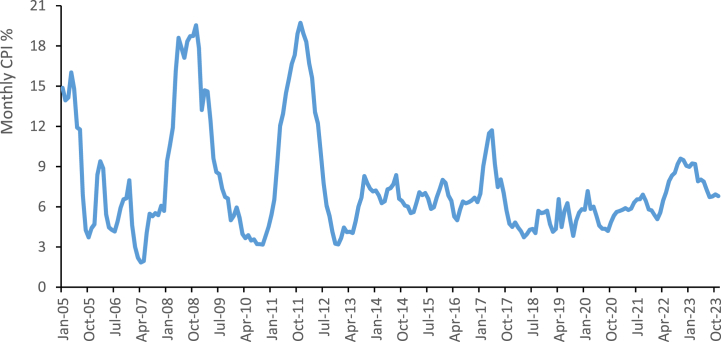

The second stylized fact is that the change in the price level (inflation) in Kenya has been unstable over time. In most cases, the upward movement in the price level has exceeded the current government's inflation target of 5 %. The monetary authority in Kenya aims at keeping the inflation rate within the range of 7.5 % at maximum and 2.5 % at minimum with an average rate of 5 %. However, this is not the case in the country since the inflation rate has often exceeded the maximum level of 7.5 %. Some months such as April 2005, June to November 2008, November 2011 and May 2017 for instance, have recording double-digit inflation rate level. The months of November 2008 and November 2011 in particular recorded the highest inflation rate over the sampled period at 19.54 % and 19.72 % respectively. After 2017, the inflation rate in the country reduced significantly, as implied in Fig. 2. The reduction in the inflation rate in the country from double digits experienced in previous years is attributed to the active involvement of the CBK in managing inflation through its commitment to maintain a low inflation rate, which saw the rate come down as low as 4.6 % on average in the year 2018 [21].

Fig. 2.

The trend in inflation rate in Kenya over time.

Over the last decade, although the inflation rate has significantly, the rate remains relatively high, with the period between June 2022 and June 2023 recording inflation rate of 8.7 % on average and the month of October 2022 recording the highest level at 9.6 %. The high inflation rate has been attributed to a number of factors, among them the depreciation of Kenya's shilling against major world currencies such as the US dollar, the sterling Pound and the Euro since the country heavily depends on imports for domestic consumption as well as raw material for manufacturing [1].

The inflation trend in the country over the study period can be visualized in Fig. 2.

The rest of this study is structured as follows: section 2 provides a literature review; sections 3, 4 cover the study methodology, results and discussion. Section 5 covers the conclusion and the policy implications.

2. Literature review

This section explores both theoretical and empirical literature regarding the exchange rates and inflation nexus. Theoretically, this study delves into two main theories that explain the relationship between inflation rate and exchange rate depreciation, which are the purchasing power parity (PPP) and the Taylor rule theories.

2.1. Purchasing power parity

Purchasing power parity (PPP) is an economic theory, which argues that the exchange rate of two currencies is at equilibrium if their value (purchasing power) is the same in either country. Otherwise, a state of disequilibrium occurs, which causes the depreciation of the weaker currency [2]. The PPP concept defines domestic prices as the ratio of two countries’ currencies such that one unit of domestic currency should be able to purchase the same amount of goods in the foreign country as the foreign currency. This concept implies that in case of depreciation of the local currency, then more of it would be needed to purchase the same amount of goods in foreign countries as foreign currency. This in turn translates to higher prices (inflation) of imported goods due to exchange rate depreciation. Therefore, this theory assumes that domestic price variations occur because of changes in long-run equilibrium between two currencies and inflation in an economy is a product of exchange rate depreciation.

Holding on to this view, numerous studies have analyzed the exchange rate pass-through effects on domestic inflation. These studies have found varying results leading to no consensus between on the relationship between exchange rate inflation especially in the threshold analysis between these variables. For example [12], confirmed evidence of PPP while studying long-run relationship between exchange rates and inflation in 19 European countries. The study employed the error correction and co-integration models on the panel data spanning 1980 to 2015 and found that exchange rate depreciation positively influences inflation. Among the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), a study by Ref. [16] on the exchange rate and inflation convergence found that exchange rate depreciation is a major cause of growing inflation in the region. This study used Granger causality test as the primary analytical model to establish a pass-through relationship between exchange rate and inflation. To add one [18], also found that exchange rate depreciation positively influences domestic growth and inflation in Nigeria. The study employed the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model on the time series data between 1981 and 2021. In Kenya, some studies have also analyzed the exchange rate depreciation and inflation rate nexus. Although the literature on this subject is still scanty, and some crucial aspects, such as threshold analysis and testing for non-linearity between these variables has not been emphasized on. For instance, recent studies such as [3,4,6,22], have revealed a pass-through relationship between exchange rate and inflation considering different analytical models as well as different periods. Therefore, it is worth mentioning that the difference between the current and previous studies lies in determining the threshold pass-through effect and checking the asymmetric relationship between the study variables.

Regarding threshold analysis [23], studied the nexus between exchange rate depreciation, money supply and inflation in Indonesia and found a significant threshold relationship between money supply and inflation but not exchange depreciation and inflation in the country. This study employed threshold analysis techniques as well as Philips curve equation analysis on the time series data spanning 1980–2008 in which it found the exchange rate depreciation to have a threshold level of 0.84 % per month, although this effect was not statistically different above and below this limit as suggested by the F-test statistic. The insignificant threshold relationship between exchange rate and inflation is further supported by Ref. [24] study on the threshold effect of exchange rate depreciation and money supply growth on inflation in Pakistan between 1982 and 2012. This study applied the Hansen technique of threshold analysis where the generalized methods of moments (GMM) model was employed to evaluate the relationship between these variables. The study supports a threshold level of exchange rate beyond which the exchange rate influences price level though the effect is insignificant. On the other hand, a study by Ref. [25] on the exchange rate pass-through effect on inflation in Iran found that exchange rate depreciation above a monthly average rate of 9.1 % has a significant positive impact on inflation. In this study, the threshold autoregressive model (TAR) model was applied as the main econometric model on time series data from 1983 to 2014. is the findings are also supported by Ref. [7], who studied the effect of exchange rate on inflation in Ghana using the monthly time series data between 2002 and 2018 and threshold autoregressive model in the analysis and found that exchange rate depreciation has a positive and significant effect on inflation in Ghana. In this study, the threshold level of exchange rate depreciation was found to be 0.71 % per month. Furthermore [26], study on the impact of exchange rate on inflation in Iran revealed that the pass-through effect of the exchange rate on inflation depends on the levels of inflation. According to this study, the threshold relationship between exchange rate and inflation is only significant when inflation rate is below 5.4 %. Otherwise, above 5.4 % rate, the central bank has a freedom to control the inflation rate, which renders the pass-through effect insignificant.

2.2. Taylor rule theory

Taylor's rule is an economic theory proposed by Ref. [27], which determines the monetary policy rate that achieves the macroeconomic goals of low inflation and high economic growth in the economy. The underlying assumption behind the Taylor rule theory is that the performance of gross domestic product, inflation, and other macroeconomic variables influence how the central bank of any country reacts to setting the monetary policy rate. The Taylor rule has been used as the primary reaction function by the central banks of countries that operate an inflation rate targeting (IT) monetary policy framework. For instance, the Central Bank of Kenya, has always considered the performance of other macroeconomic variables such as exchange rate and gross national product while setting monetary policy rates to control inflation [28]. The Taylor rule was first coined by Ref. [27] as shown in Equation (1).

| (1) |

where, , is the central bank policy rate, while and denote inflation and output gaps respectively. The inflation and output gaps refer to the difference between the targeted variable performance and the actual performance realized within a given measurement period. and are the relative weights attached to inflation and output gap by the central bank. The Taylor rule proposes that the central bank should increase the policy rate anytime it realizes a positive inflation and output gap. That is, if the realized inflation and output are higher than the targeted in order to control domestic prices [5].

Given the integration of world's economic systems, the susceptibility to exchange rate fluctuation cannot be avoided. This calls for the need to augment the Taylor rule with exchange rate fluctuation in setting monetary policy rate. Augmenting the Taylor rule with exchange rate depreciation enables the central bank to control inflation through monetary policy actions while considering exchange rate movements in the country [10]. Empirically, this argument has been embraced by studies such as [29] who analyzed the relationship between inflation target and monetary policy in Ghana, used ordinary least squares, Probit and Logit models. However, this study found no impact of exchange rate depreciation on monetary rule in the country. On the other hand a study by Ref. [7] on the non-linear relationship between exchange rate and inflation also analyzed the Taylor rule using the threshold autoregressive model and found a significant positive relationship between the exchange rate and monetary policy rule in Ghana [7] suggest that assuming a linear relationship between exchange rate and monetary policy rule might be misleading especially in countries with high exchange rate depreciation. This might explain why the study by Ref. [29] found no significant relationship between the exchange rate and monetary policy rate in Ghana. The positive relationship between exchange rate depreciation and monetary policy rate is also confirmed by Ref. [30] in the study inflation targeting and exchange rate volatility in emerging economies. This study employed the ordinary least squares, fixed effect and system GMM as the empirical techniques in modeling the Taylor rule. Furthermore [31], argue that while analyzing monetary policy in emerging economies, it is essential to accurately augment exchange rates using non-linear economic models to capture this variable's behaviour. In this study, the augmented Taylor rule and the threshold non-linear GMM model were employed for analysis and a positive relationship between exchange rate fluctuation and monetary rate recorded.

The current study thus uses the augmented Taylor rule to determine the relationship between exchange rate fluctuation and monetary policy rate in Kenya considering a non-linear relationship between these variables. This analysis is relevant since in the country, very little has been done to establish the relationship between exchange rate depreciation and monetary policy rate, even though it is evident that economic integration exposes Kenya's economy to the adverse effect of local currency fluctuation [1].

Identifying the threshold levels in this study is crucial since the interaction between the macroeconomic variables tends always not to be direct but affected by other variables. Theoretically, this concept is featured in the threshold hypothesis analysis, which stresses on existence of a critical point (threshold level) beyond which a variable's behaviour and significance changes. At this point, the effect of one variable on the other may change from being non-existent or small to being more pronounced. The threshold analysis is important because in some cases, the relationship between variables is not linear but follows certain forms, such as quadratic or exponential. Similarly, the non-linearity in the study is due to the fact that there existence of a certain saturation point beyond which the variable exhibits diminishing returns to scale. In this case, an increase in the input variable (exchange rate) may not lead to a proportional increase in the output variable (inflation or monetary policy rate). To add on, the threshold relationship between variables is justified by the fact that some macroeconomic variables are not directly related but rather depend on other variables, which might have varying effect on the target variable. In this case, the magnitude of changes in the values of one variable is influenced by the value of other hidden variables (control variables) that are likely to cause more or less impact on target variable [32]. For instance, monetary policy rates may indirectly affect inflation through rising interest rates in the economy.

3. Methodology

3.1. Variable description and data

The data for this study was a monthly time series spanning January 2005 to November 2023. The selection of this period is based on data availability and it also with the period when Kenya officially adopted inflation targeting by the Central Bank of Kenya as a monetary policy framework. The data was collected from a number of sources, such as the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK), Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), China Economic Information Center (ceicdata.com), and www.indexmundi.com databases. In terms of measurement of study variables, this study measured inflation rate as the average consumer price index per month while the inflation gap was measured as the difference between the actual inflation rate and the inflation target rate by the CBK, which is at 4 % from 2005 to 2014 December and 5 % thereafter. The monetary policy rate was measured as the monthly CBK rate, while the exchange rate depreciation was expressed as the monthly change in the value of the Kenya shilling against the US dollar. The global oil price was measured as the average change in crude oil price in US dollars per barrel. The money supply was determined as the percentage change in broad money supply (M2) per month, which is the sum of all liquid assets held by the CBK and all other assets that can easily be converted into cash for the transaction. The selection of these variables, as well as the measurement units was based on the inflation theories as well as empirical studies such as [2,5,7,11] who have employed such variables in their work. A summary of the description of the variables and the source of data is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary data description.

| Variable | Abbreviation | Measurement unit/proxy | Expected sign | Data source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflation | INF | Monthly CPI% | CBK | |

| Exchange rate depreciation | EXR | A percentage change in the value of Kenya shilling against US dollar % | Positive on inflation and monetary policy rate | CBK |

| Inflation gap | INFG | The percentage difference between monthly CPI and target inflation rate | Positive on monetary policy rate | CBK |

| Monetary policy rate | MPR | Monthly CBK rate | Negative on inflation | CEIC database |

| Broad money supply | M2 | Monthly percentage change in broad money supply | Positive on inflation | KNBS |

| Global oil price | GOP | Monthly Percentage change in crude oil price per barrel in US dollars | Positive on inflation | indexmundi.com database |

Note: CBK, KNBS, CEIC denotes Central Bank of Kenya, National Bureau of Statistics and China Economic Information Center respectively.

3.2. Empirical model specification

This study first specified the empirical model for the exchange rate pass-through on inflation and then built the Taylor rule model to capture the reaction function of CBK using the threshold autoregressive model (TAR) model. The TAR model was selected for this study because it can deal with the evaluation of endogenous changes in asymmetric policy behaviors by the central bank following changes in regimes and financial crises [31,33].

To start with the threshold effect of exchange rate on inflation, this study implicated the work of [2,7], who modified the purchasing power parity model to analyze the behavior of the central bank by including the policy rate as follows.

| (2) |

where , denote domestic inflation rate, exchange rate depreciation, global oil price and monetary policy rate. … , are the parameters to be estimated and is the error term of the model. The inclusion of monetary policy rate is based on the facts that most central banks adopt inflation targeting policy through regulating exchange rate to lower inflation [13]. Global oil price was included in the model to capture the effect of external forces that influence domestic inflation. For instance, in Kenya, most of the key sectors, such as transport and manufacturing, rely on energy obtained from oil products such that when oil prices increase, the operation cost of these sectors also increases, which is passed to consumers through higher domestic prices [1].

This study further modified Equation (2) to include the lagged exchange rate depreciation to capture how past exchange rate depreciation influences the current inflation rate. This is necessary since policymakers use past information when formulating inflation-targeting economic policies [7]. The change in money supply as a major determinant of inflation among most developing countries is was included in the final estimation model, as shown in Equation (3).

| (3) |

where and denote one period lagged exchange rate, and change in broad money supply respectively. The rest of the variables remain as defined in Equation (2). From this equation, we assumed that the relationship between the dependent variable (inflation) and all explanatory variables is positive; hence, positive coefficients for all independent variables.

Turning to exchange rate depreciation and monetary policy rate, the current study relied on the Taylor rule and modified the empirical models by Refs. [5,31] as in Equation (4).

| (4) |

where , , and are monetary policy rate, current period exchange rate depreciation, one period lagged exchange rate depreciation and inflation gap respectively. , and denote the constant term, the error term and the parameters to be estimated in the Taylor rule model. In Equation (3) we assume a positive relationship between exchange rate and inflation such that the coefficients of as well as are positive. If that is the case, then Equations (3), (4)) imply that it is possible to control both inflation and exchange rate fluctuation using same policy variables as stated by Ref. [34].

3.3. Threshold autoregressive model specification

In statistics, threshold models are special empirical framework, which argues that a statistical process under consideration may behave differently when the value of the concern variables exceed certain critical points (threshold values). The common threshold models employed in empirical analysis include the Markov-switching model, the smooth transition model, and the threshold autoregressive model [24]. The current study adopted the threshold autoregressive (TAR) model proposed by Ref. [35] The TAR model was selected because it can generate robust threshold results through which exchange rate pass-through effect and test for the non-linear relationship between variables beyond certain hold levels is expressed [5]. This property of the TAR model intermarry with our study objectives, hence, it is a suitable model for analysis. Based on the objective of this study, the monthly exchange rate depreciation was selected as the threshold variable, in which the effect of this variable was checked in both high and low regimes. The selection of TAR model over the Markov switching models is because while the latter assumes that the process that causes the non-linear dynamic relationship is latent, the former assumes that observable variables cause the non-linear effect. This makes it easy to estimate threshold levels of exchange rate in the model with the former (TAR) model. Similarly, the TAR provides an interpretable threshold since the threshold value presents a critical point beyond which the variable dynamics change, this influences policy decision [36].

Deduced from the empirical model by Ref. [37], this study specified the non-linear TAR model as in Equation (5).

| (5) |

where is the independent variables, for our case, inflation rate as in Equation (3) and monetary policy rate as in Equation 4. , r and m denote a vector of all independent variables, threshold value and dummy indicator functions respectively. The threshold value r splits exchange rate depreciation into two regions as low regime (below threshold value) and high regime (above the threshold value). This is defined in Equation (5) as and . , , and are constant terms and parameters to be estimated based on the threshold region.

Integrating our estimation variables, for the exchange rate pass-through effect model in Equation (3) as well as Taylor rule model in Equation (4), we modified the two threshold equations as in 6 and 7.

| (6) |

| (7) |

where all the variables are as defined in the previous equations. Equation (6) was used to estimate the threshold relationship between exchange rate and inflation, while Equation (7) estimated threshold relationship between exchange rate and monetary policy rule. To determine whether the model exhibits a non-linear trend across different estimation regimes and whether the threshold autoregressive estimation model is valid (significant), the bootstrap Langrage Multiplier (LM) test was employed to check the significance of the threshold model. The tests sought to reject the null hypothesis that there is no threshold relationship between the variables and that a simple linear model can be used to estimate the relationship between variables to give price results [38]. The non-linearity of the study model was further validated through the Wald test for parameter equality across regimes. The test also sought to reject a null hypothesis of equal parameters across different regimes (linear relationship) against an alternative hypothesis of the asymmetric relationship between independent and dependent variables across different regimes defined by the threshold variable [13].

4. Estimation results and discussion

This section analyses and discusses the estimated results. It starts by presenting the descriptive statistics of the variables used in the study and their stationarity test analysis before discussing the threshold autoregressive model estimation results, the validity of these results and lastly, the non-linearity test of the model.

4.1. Descriptive statistics

In describing the variables' characteristics, we considered the mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values. The descriptive statistics results are shown in Table 2. The variable mean measures the average value, while the standard deviation shows how these values are distributed around the mean. From Table 2, the monthly inflation rate in Kenya is 7.62 on average while that of the exchange rate depreciation is 0.32 %. The sampled period shows a combination of a high inflation rate at 19.72 maximum and a standard deviation of the exchange rate depreciation at 1.80 (almost three times its mean). This means that managing the inflation to a monetary policy target rate of 5 % continues to be a challenge, and the exchange rate volatility in the country is high. The combination of high inflation and exchange rate volatility poses a severe challenge other country's macroeconomic variables such as economic growth change in investment and balance of trade. Similarly, the monetary policy rate and Inflation gap have the mean values of 9.27 and 3.15, with the maximum values of 18 and 15.72. Inflation variation has a mean value of 3.15 greater than the target variation of 2.5 % basis point above or below the target level of 5 %, which implies high fluctuations in domestic prices in Kenya. The average monetary policy rate of 9.27 % is close to the mean inflation value of 7.62, suggesting a correlation between these variables in the country.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Standard deviation | Maximum value | Minimum value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INF | 227 | 7.617 | 3.991 | 1.852 | 19.720 |

| EXR | 227 | 0.316 | 1.801 | −4.491 | 7.551 |

| MPR | 227 | 9.273 | 2.362 | 5.750 | 18 |

| INFG | 227 | 3.153 | 4.182 | −2.150 | 15.720 |

| M2 | 227 | 0.981 | 1.258 | −4.758 | 6.795 |

| GOP | 227 | 0.881 | 9.592 | −39.641 | 44.390 |

Note: INF, EXR, INFG, MPR, M2 and GOP represents monthly inflation rate, exchange rate depreciation, monetary policy rate, inflation gap, change in broad money supply and change in global oil prices respectively.

4.2. Stationarity test

Non-stationary variables (presence of unit root) give rise to spurious regression results hence caution should be taken to ensure all the variables are stationary before analysis [39]. In line with the argument by Ref. [39], this study employed Augment Dickey-Fuller test by Ref. [40] and Philips Perron (P–P) proposed by Ref. [41] to check whether the variables used have unit root or otherwise. In both tests, the null hypothesis of variable non-stationarity is tested against the alternative of stationarity of variables in all cases seeking to reject the null hypothesis. Table 3 presents the stationarity test results. From this table, the stationarity test results reveal that all variables are stationary either at level l(0) or first difference l(1). Stationarity of the variables under the same order means that the statistical processes among the study variables under consideration are consistent over different moment regimes, which justifies the dynamic threshold autoregressive model analysis employed in this study [42].

Table 3.

Stationarity test results.

|

Variable |

ADF-test |

P–P- test |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| l(0) | l(1) | l(0) | l(1) | Remarks | |

| INF | −4.058** | −6.958*** | −4.058** | −4.055** | stationary |

| EXR | −4.005** | −4.011** | −4.605*** | −4.621*** | stationary |

| INFG | −5.693*** | −4.741*** | −5.693*** | −5.921*** | stationary |

| MPR | −3.847** | −3.523* | −3.847** | −3.847** | stationary |

| M2 | −4.410*** | −4.712*** | −4.410*** | −4.434*** | stationary |

| GOP | −3.780** | −5.716*** | −3.780** | −3.779** | stationary |

Note: INF, EXR, INFG, MPR, M2 and GOP represents monthly inflation rate, exchange rate depreciation, inflation gap, monetary policy rate, change in broad money supply and change in global oil prices respectively. *, **, and *** implies the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % significance levels respectively at which null hypothesis is rejected.

4.3. Threshold autoregressive (TAR) model estimation

Given that the study variables were free from unit root problem; this study proceeded to TAR model estimation. The model estimated the exchange rate pass-through effect on inflation and the exchange rate monetary policy nexus using Taylor rule and presented the results as in Table 4, Tables 5, respectively. In each estimation model, both linear and non-linear TAR models are presented, where the linear model is used as the baseline model for comparison purposes. To start with the exchange rate pass-through effect on inflation, the monthly threshold exchange rate level was found to be 0.51 %, equivalent to a yearly exchange rate depreciation rate of 6.12 % in Kenya. This is realistic since the country has, over time, experienced an annual exchange rate depreciation of between 3.6 % and 9.3 %, with the highest exchange rate depreciation rate being 21.9 % between September 2022 to September 2023 [19]. The results on the exchange rate pass-through effect on domestic inflation in Table 4 show that the effect of the exchange rate on inflation is positive and statically significant in both linear and non-linear models however, the significance is more inclined to the latter as implies by p < 0.00 in the non-linear TAR model. The coefficient of exchange rate in the upper region (high exchange rate regime) (EXR>0.51) shows that the current period, as well as lagged exchange rate depreciation, increases the inflation to rise by 0.29 % and 0.08 %, respectively, at a 1 % significance level. Below the threshold level established, the effect of exchange rate depreciation is positive but insignificant, while that of a lagged exchange rate is significant at a 5 % significance level. This means that a 1 % increase in the legged exchange rate in the lower regime increases inflation by 0.04 %, holding other factors constant. In the higher exchange rate depreciation regime, (above the threshold level) both the current period and lagged exchange rate variables have a positive and significant effect on inflation in Kenya. This is because the country's overreliance on imported products, such that high depreciation of Kenya shilling against major trade currencies leads to importation a few goods from international markets using a lot of local currency. The few imported products end up feting higher prices in the local market thus fueling domestic inflation [1].

Table 4.

Exchange rate pass through effect on inflation.

| Variable | Linear model | Non-linear mode |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower regime | Upper regime | ||

| EXR | 0.0246* (0.061) | 0.008 (0.968) | 0.286*** (0.000) |

| EXR_1 | 0.078** (0.006) | 0.041** (0.004) | 0.075*** (0.000) |

| MPR | −0.0709** (0.045) | −0.156* (0.063) | −0.0713* (0.066) |

| GOP | 0.0017 (0.562) | 0.0019* (0.056) | 0.0046 (0.162) |

| M2 | 1.72** (0.032) | 1.48 (0.185) | 1.1947** (0.003) |

| CON | 2.862*** (0.000) | 5.680*** (0.000) | 2.466*** (0.000) |

| BIC | 1356.4904 | 399.1177 | |

| Threshold value | 0.51 | ||

Note: EXR, EXR_1, MPR, M2 and GOP represents, current period exchange rate depreciation, lagged exchange rate depreciation, monetary policy rate, change in broad money supply and change in global oil prices respectively. *, **, and *** implies the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % significance levels respectively at which null hypothesis is rejected. The ensure the TAR model estimated does not suffer from serial correlation as well as heterogeneity problem, this model employed use of robust standard errors during estimation.

Tables 5.

Exchange rate threshold in Taylor rule results.

| Variable | Linear model | Non-linear mode |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower regime | Upper regime | ||

| EXR | 0.024 (0.159) | 0.059** (0.041) | 0.036* (0.067) |

| EXR_1 | 0.105* (0.073) | 0.372*** (0.000) | −0.1097* (0.070) |

| INFG | 0.073 (0.876) | 0.098** (0.032) | 0.015** (0.015) |

| CON | 8.358*** (0.000) | 8.608*** (0.000) | 8.322*** (0.000) |

| BIC | 315.4904 | 55.350 | |

| Threshold value | 0.67 | ||

Note: EXR, EXR_1, INFG and CON represents current period exchange rate depreciation, lagged exchange rate depreciation, inflation gap and constant term respectively. *, **, and *** implies the 10 %, 5 % and 1 % significance levels respectively at which null hypothesis is rejected. The ensure the threshold autoregressive model estimated does not suffer from serial correlation as well as heterogeneity problem, this model employed use of robust standard errors during estimation.

Empirically, the positive relationship between exchange rate and inflation has been supported by studies such as [13] in Fragile Five (Brazil, India, Indonesia, Turkey and South Africa) [43],in Bulgaria and [7] in Ghana. These studies argue that exchange rate volatility causes domestic inflation due to an increase in import prices whenever the domestic currency weakens against an international currency, making imported products expensive in the local markets. In contrast, the negative relationship between exchange rate and inflation has also been reported by Ref. [34] among the southern development communities (SADC) and [44] in Nigeria. According to these studies, low levels of exchange rate are necessary for stability of macroeconomic variables in the country because they attract foreign investors who tend to invest in sectors such as manufacturing and value addition; this lowers the demand for import thus reducing inflation.

The current study also reveals that, both monetary policy rate and money supply also have a significant effect on Inflation, although the former has a negative effect while the latter has a positive impact on inflation. The coefficients of these variables imply that holding all other factors constant, 1 % increase in the monetary policy rate reduces inflation by −0.071 % at a 10 % significance level. In comparison, the increase in broad money supply by 1 % increases inflation rate by 1.195 % at a 10 % significance level. The negative relationship between monetary policy rate and inflation could be due to the discouragement of domestic borrowing while encouraging saving by the households whenever the interest rate increases due to upward shift in monetary policy rate. Reduced borrowing and increased savings lower circulation of money in the economy hence a decline inflation rate [45]. To add on, a unit increase in money supply is associated with an over 1 % increase in Inflation, which supports Milton Friedman's famous quote, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. These results are consistent with the studies such as [46] in Europe, and [45] among 118 developing countries and contradicts the results by Ref. [7] in Ghana, who found a positive relationship between monetary policy rate and Inflation. This study's findings and those of [7] in regard to monetary policy and inflation are different because in Kenya, domestic inflation has always had an upward deviation from the CBK enacted rate of 5 %. This has often forced the central monetary authority in the country to increase interest rates in order to lower the money supply and ease inflation pressure [14]. This is also evident in Fig. 2, which shows that CPI has consistently been above the 5 % target rate by the CBK.

To add on the current study also found a positive relationship between the change in global oil prices and domestic inflation in Kenya, with the effect being significant in the non-linear model only in the low exchange rate regime. Above the threshold level, the effect remains positive but insignificant which could be because when the exchange rate depreciation is high the demand for the global oil tend to reduces because a lot of local currency is needed to be converted to US dollars in order to import crude oil. For instance companies tend to improvise some other means of generating their own energy such switch to renewable sources of energy such solar to lower the production cost. This in turn reduces crude oil consumption, which is attributed to the insignificant relationship between global oil prices and inflation [9]. Money supply positively affects inflation only in the upper regime in the non-linear TAR model, implying a combination of high exchange rate and money supply leads to inflation.

The pass-through effect of the exchange rate on inflation above the threshold level can be visualized as in Fig. 3. From the figure, it can be observed that Kenya's exchange rate fluctuation is high higher above the threshold value of 0.51 % over the period in which the study is conducted, supporting the results obtained in Table 4 that exchange rate depreciation has a pass-through effect on inflation above the threshold level and that the relationship between these variables is non-linear.

Fig. 3.

Exchanger rate classification bases on the threshold rete.

Turning to the Taylor rule threshold analysis, this study found that the current period exchange rate depreciation has positive and significant effect on monetary policy rate in the non-linear model. The positive relationship between the lagged exchange rate and monetary policy is also found in the linear model, while the negative relationship is expressed in the non-linear model above the threshold value (EXR>0.67). The lagged exchange rate has a significant effect on the monetary policy in both linear and non-linear models, which turns from positive to negative from low to higher exchange rate regime. This signifies the possibility of the Central Bank of Kenya paying more attention to the previous event (lagged exchange rate) while designing the policies in the country. The coefficient of Taylor rule estimation reveals that holding other factors constant, the current period exchange rate influences Kenya's monetary policy rate by 0.04 %. It can also be observed that this variable is significant in both high and low exchange rate regimes, suggesting that exchange rate depreciation influences the monetary policy rate regardless of whether it is low or high in the country.

From the Taylor rule results in Tables 5, it can be conclude the following about lagged exchange rate and monetary policy rate. That a unit increase in one period lagged exchange rate increases the monetary policy rate by 0.11 % in the linear model,0.37 % in the lower regime of the non-linear model and then reduced the policy rate by −0.11 % in higher exchange rate regime. The relationship between a lagged exchange rate and monetary policy rate in the low exchange rate regime is positive because in this region, as the local currency depreciates, the investors tend to be scared and withdraw their investment because they fear losing money in unstable economy. To counter this situation and bring back the lost confidence, the central bank tends to increase the policy rate to attract capital inflow, hence a positive relationship between these variables. In Kenya, this has been the case, since the country has often adjusted the policy rate to enhance FDI inflow [14]. The negative relationship between a lagged exchange rate and monetary rate could be because high exchange rate depreciation has a negative impact on economic growth due to the increased cost of import, which in turn lowers consumer purchasing power. To mitigate this risk, the central bank intend to lower the monetary policy rate to stimulate household borrowing and spending, which offsets the effect of depreciation [18]. It can also be noted that, though the effect of the exchange rate on monetary policy is significant in both low and higher regimes, it is stronger in the lower exchange rate regime, which is consistent with the work of [31]. This finding provides a possibility of augmenting the Taylor rule with the exchange rate as proposed by studies such as [5]. This study also found a positive and significant impact of inflation gap on Kenya's monetary policy rate in both low and high exchange rate regimes of the non-linear model. The coefficient of this variable implies that a unit deviation of inflation from the CBK inflation rate target (inflation gap) increases the monetary policy rate by 0.02 %, holding other factors constant. This seems realistic since Kenya's monetary authority has often adjusted the policy rate to control money circulation in the economy through increased lending rates and lower inflation volatility [21]. The Taylor rule model results' emphasizes on the importance of observing the exchange rate depreciation as a reaction variable when designing macroeconomic goals in the Country, regardless of the threshold level.

To test for the significance and specification of the threshold model [38],propose the bootstrap-based test uses the Langrage Multiplier (LM) statistic to check whether the estimated threshold relationship between the study variables is valid. This test provides a null hypothesis of no threshold relationship and an alternative hypothesis of the existence of the threshold level in the collected data. The bootstrap test was conducted with 5000 replication at 10 % data trimming and the results as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

LM-test for no threshold relationship between exchange rate and inflation.

| Exchange rate pass through effect on inflation | |

| Number of bootstrap replication | 5000 |

| Data trimming percentage | 10 % |

| Threshold value (exchange rate pass through effect) | 0.51 |

| LM-test statistics (no threshold relationship) | 97.22 |

| Bootstrap p-value |

0.000 |

| Exchange rate threshold in Taylor rule results | |

| Number of bootstrap replication | 1000 |

| Data trimming percentage | 10 % |

| Threshold value (Taylor rule estimation) | 0.67 |

| LM-test statistics (no threshold relationship) | 104.15 |

| Bootstrap p-value | 0.000 |

Based on the results, the LM-test statistics test for the exchange rate pass-through model and Taylor rule models are 97.22 and 104.15, respectively. Compared with the Chi-square critical value at 2 degrees of freedom at 5.991, this study rejected the LM test null hypothesis of no threshold relationship and concluded that there exists a threshold relationship between exchange rate and inflation as well as exchange rate and monetary policy rate. Similarly, the p-value for the bootstrap test is less than the critical value at a 5 % confidence level, further justifies the rejection of the null hypothesis of no threshold level in the data. Rejecting the LM test null hypothesis in favour of the alternative hypothesis means that the TAR model estimated is significant and the relationship between the variables under consideration is nonlinear.

The Wald test for nonlinear relationships between variables under different regimes was also tested on top of bootstrap test for threshold significance. The estimated results in Table 7 support an existence of a non-linear relationship between exchange rate and inflation in the TAR model and exchange rate with monetary policy rate in the Taylor rule model. This is justified by the probability values of 0.000 and 0.014 < 0.05, which implies high exchange rate depreciation is likely to be associated with higher fluctuation in the inflation rate as well as the monetary policy rate in Kenya. This could be due to persistent changes in the economy's business cycles, the country's geopolitics and the existence of different economic agents who behave differently during the period of persistent exchange rate depreciation [47]. The bootstrap LM test and Wald test imply that analyzing the relationship between exchange rate and inflation as well as the exchange rate depreciation and monetary policy using linear regression models might give misleading results.

Table 7.

Test for non-linearity.

| Model | Chi-square statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Exchange rate pass through model | 30.05 | 0.000 |

| Taylor rule model | 13.88 | 0.014 |

Note: The null hypothesis of linear relationship of exchange rate across all the regions is to be rejected at 5 % confidence level that is p-value <0.05.

5. Conclusion and policy implication

This study analyzed the threshold pass-through effect of exchange rate depreciation on inflation in Kenya using the threshold autoregressive model (TAR) with monthly time series data from January 2005 to November 2023. Furthermore, the study tested for the non-linear relationship between exchange rate and inflation and determined the relevance of augmenting exchange rate depreciation with monetary policy rate using the Taylor rule. The current study's contribution to the policymakers is to provide an optimal level of exchange rate depreciation beyond which it causes macroeconomic instability (raising inflation). To the body of literature, the current study used a non-linear TAR model and checked whether the relationship between the study variables is asymmetric. This is relevant since most of previous studies have assumed a symmetric relationship between these variable. The findings of this study reveal that exchange rate depreciation beyond a monthly threshold level of 0.51 %, equivalent to an annual threshold level of 6.12 %, has a positive significant pass-through effect on inflation in Kenya. The TAR model estimated is significant as revealed by bootstrap and LM tests, which gives traction on the relevance of the threshold level obtained. Similarly, this study also found that regardless of the threshold level of 0.67 %, exchange rate depreciation has a positive significant effect on monetary policy rate as revealed by the Taylor rule estimation. This means that the exchange rate depreciation should always be the CBK reaction function when designing the monetary policy rate. Furthermore, this study found that lagged exchange rate and broad money supply have positive effect on Kenya's inflation while the monetary policy rate has a negative effect on inflation over the sampled period. Concerning the exchange rate and monetary policy rate nexus, this study found that exchange rate depreciation and inflation gap have a positive and significant effect on the monetary policy rate regardless of the threshold level of 0.67 %.

The main finding of this study is that the exchange rate pass-through effect on inflation only happens when the depreciation rate goes beyond a threshold level of 0.51 %. In particular, the positive effect of the exchange rate on inflation is non-linear, implying a higher positive impact of the exchange rate depreciation on inflation above the threshold level. Therefore, this study recommends policymakers, monetary policy regulators and other stakeholders in Kenya to work towards keeping exchange rate depreciation below the threshold level to control domestic inflation. This can be realized through actions and policies such as adoption of forward forex trading by CBK through availing enough foreign currency based on available foreign reserves to meet the demand for foreign currency (US dollar) whenever it is speculated to increase. This will ease the pressure on the US dollar and contain high exchange rate depreciation.

In addition, the exchange rate fluctuation has a higher impact on inflation in Kenya due to overreliance on imported goods. This makes the country to become vulnerable to macroeconomic instability every time the Kenyan shilling weakens against major currencies used in international markets such as dollar and pound due to imported inflation. To curb this, the government should aim at reducing overreliance on import by creating a conducive environment that favours public-private partnerships that can lead to the establishment of import substitution industries in the country. Similarly, the current campaign on “buy Kenya build Kenya initiative” should be intensified to reduce pressure on the import demand and lower inflation pressure. To add on, the government should check on the debt servicing cost, especially the foreign debt because it tends to increase the demand for the US dollar or any other foreign currency applicable whenever these loans are due leading to higher depreciation. This can be done by creating a domestic buffer and operating a budget surplus to reduce the country's debt as well as servicing costs. On the relevance of monetary policy rate, this study recommends that the monetary policy committee should view every exchange rate level as important for adjusting the policy rate to control the exchange rate effect on the economy. For instance, during a higher exchange rate depreciation period, the monetary authority should raise the interest rate to make local money market investments attractive. This will attract foreign investors and lead to increased demand for Kenya shilling, thus domestic currency appreciation.

6. Study limitation and suggestion for further research

This study has analyzed the exchange rate pass-through effect on inflation in Kenya using the TAR model, although there are other models for threshold analysis, such as Markov switching models. Future studies are encouraged to explore other methods of threshold analysis and check whether the results hold. Similarly, this study found a threshold relationship between the exchange rate and inflation in Kenya, which gives the possibility of the exchange rate having an adverse effect on other macroeconomic variables, such as gross domestic product, national savings, and consumption, among others. Future studies can test this relationship by considering other macroeconomic variables in the country.

Data availability statement

The data associated with this study is publicly available in Central Bank of Kenya (CBK), Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), China Economic Information Center (ceicdata.com), and www.indexmundi.com repositories.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jerry Ogutu Sumba: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Kennedy Ocharo Nyabuto: Supervision. Paul Joshua Mugambi: Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Jerry Ogutu Sumba, Email: sumbajerry@gmail.com.

Kennedy Ocharo Nyabuto, Email: ocharo.nyabuto@embuni.ac.ke.

Paul Joshua Mugambi, Email: mugambij64@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Lidiema C. Trade openness and crude oil price effects on food inflation: examining the Romer hypothesis in Kenya. J. World Econ. Res. 2020;9(2):91. doi: 10.11648/j.jwer.20200902.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monadjemi M., Lodewijks J. International evidence on purchasing power parity: a study of high and low inflation countries. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2021;4(3):p1. doi: 10.30560/jems.v4n3p1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ndongo D., Revelli P. WP-392-The exchange rate pass-through to inflation and its implications for monetary policy in Cameroon and Kenya. 2020. https://aercafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Research-Paper-392.pdf [Online]. Available:

- 4.Njenga J.K. Exchange rate pass-through dynamics : VAR evidence for Kenya. 2023;19(10):45–56. doi: 10.9734/ARJOM/2023/v19i10725. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Özdemir M. The role of exchange rate in inflation targeting: the case of Turkey. Appl. Econ. 2020;52(29):3138–3152. doi: 10.1080/00036846.2019.1706717. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiptarus N.S., Saina E.K. Journal of business management and exchange rate volatility and its effect on trade export performance in Kenya. 2022;6(3):91–107. doi: 10.29226/TR1001.2022.305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valogo M.K., Duodu E., Yusif H., Baidoo S.T. Effect of exchange rate on inflation in the inflation targeting framework: is the threshold level relevant? Res. Glob. 2023;6(September 2022) doi: 10.1016/j.resglo.2023.100119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang J., Lee S. An analysis of the determinants of inflation-linked bond prices in Korea. Asia-Pacific J. Financ. Stud. Oct. 2018;47(5):605–633. doi: 10.1111/ajfs.12232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nandelenga M.W., Simpasa A. Oil price and exchange rate dependence in selected countries. African Dev. Bank Gr. 2020;(334):1–45. Working Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lagoa S. Determinants of inflation differentials in the euro area: is the New Keynesian Phillips curve enough? J. Appl. Econ. May 2017;20(1):75–103. doi: 10.1016/S1514-0326(17)30004-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ha J., Stocker M.M., Yilmazkuday H. Inflation and exchange rate pass-through. 2019. http://www.worldbank.org/research [Online]. Available:

- 12.Arize A.C., Malindretos J. Exchange rate and long-run price relationship in 19 selected European and LDCs. 2019;12(1):97–120. doi: 10.1108/JFEP-08-2018-0117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Şen H., Kaya A., Kaptan S., Cömert M. Interest rates, inflation, and exchange rates in fragile EMEs: a fresh look at the long-run interrelationships. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. Apr. 2020;29(3):289–318. doi: 10.1080/09638199.2019.1663441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibson . 2020. Impact of external debt on inflation and exchange rate in Kenya Gibson Marienga Arisa a research project submitted to the Department of Economic Theory in the school of economics in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the award of a degree of master of economics of Kenyatta University. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kayongo A., Guloba A., Muvawala J. Asymmetric effects of exchange rate on monetary policy in emerging countries : a non-linear ARDL approach in Uganda. 2020;7(5):24–37. doi: 10.11114/aef.v7i5.4928. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ndiaye A. 2021. Exchange Rates and Inflation Rates Convergence in ECOWAS; pp. 1726–1747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohemeng W., Agyapong E.K., Ofori-boateng K. Exchange rate and inflation dynamics : does the month or quarter of the year Exchange rate and inflation dynamics : does the month or quarter of the year matter. SN Bus. Econ. 2021;1(6):1–24. doi: 10.1007/s43546-021-00074-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Udo A., Akpan B. The Nigerian Experience. 2023. “Exchange rate and inflation rate nexus : the Nigerian experience exchange rate and inflation rate nexus; pp. 10–23. August. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quarter T. May, 2009. “Quarterly Economic and Budgetary Review,” Econ. Aff. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gasoil A. Tender for supply of automotive gasoil through a. 2023;2023(3) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alper E., Clements B., Hobdari N., Moya Porcel R. Do interest rate controls work? Evidence from Kenya. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2020;24(3):910–926. doi: 10.1111/rode.12675. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sophie S. vol. 4. 2023. pp. 891–897. (Effects of Exchange Rate on Performance of Equity Funds in Kenya). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wimanda R.E. Threshold effects of exchange rate depreciation and money growth on inflation: evidence from Indonesia. J. Econ. Stud. 2014;41(2):196–215. doi: 10.1108/JES-02-2012-0011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sajid G.M., Muhammad M., Siddiqui Z. “Threshold effects of exchange rate depreciation and money growth on inflation rate: evidence from Pakistan. Artech J. Art Social Sci. 2018;1(1):1–8. Artech Journals. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seyyedkolaee M.A., Samimi A.J., Tehranchian A.M., Mojaverian M. The impact of exchange rate pass-through via domestic prices on inflation in Iran: new evidence from a threshold regression analysis 1. 2016;8(1):77–96. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tahsili H. “The impact of exchange rate shock on inflation in Iran ’ s economy : application of the threshold vector autoregression model یوگل ا دربراک : ناریا داصتقا رد مروت رب زرا خرن هناکت. یراذگرثا یا هناتسآ یرادرب نویسرگردوخ,”. 2022;27(91):257–285. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCallum B.T. Discretion versus policy rules in practice: two critical points. A comment. Carnegie-Rochester Conf. Ser. Public Policy. 1993;39(C):215–220. doi: 10.1016/0167-2231(93)90010-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nyakerario Misati R., Morekwa Nyamongo E., Kamau Njoroge L., Kaminchia S. Feasibility of inflation targeting in an emerging market: evidence from Kenya. J. Financ. Econ. Policy. 2012;4(2):146–159. doi: 10.1108/17576381211228998. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bleaney M., Morozumi A., Mumuni Z. Inflation targeting and monetary policy in Ghana. J. Afr. Econ. 2020;29(2):121–145. doi: 10.1093/jae/ejz021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ebeke C., Fouejieu A. Inflation targeting and exchange rate regimes in emerging markets. B E J. Macroecon. 2018;18(2):1–30. doi: 10.1515/bejm-2017-0146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caporale G.M., Helmi M.H., Çatık A.N., Menla Ali F., Akdeniz C. Monetary policy rules in emerging countries: is there an augmented nonlinear taylor rule? Econ. Modell. 2018;72:306–319. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2018.02.006. October 2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Max-Neef M. Economic growth and quality of life: a threshold hypothesis. Ecol. Econ. 1995;15(2):115–118. doi: 10.1016/0921-8009(95)00064-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boissay F., Collard F., Galà J., Manea C. Monetary policy and endogenous financial crises. SSRN Electron. J. 2022;2022(991) doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4201911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olamide E., Ogujiuba K., Maredza A. Exchange rate volatility, inflation and economic growth in developing countries: panel data approach for SADC. Economies. 2022;10(3) doi: 10.3390/economies10030067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tong H. Signal Process; 1978. “On a Threshold Model in Pattern Recognition and Signal Processing,” Pattern Recognit; pp. 575–586. January 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maitland-Smith J.K., Brooks C.S. Threshold autoregressive and markov switching models: an application to commercial real estate. J. Property Res. 1999;16(1):19. doi: 10.1080/095999199368238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sikhawal S. The non-linear impact of financial development on income inequality: evidence from dynamic panel threshold model. J. Econ. Stud. 2023 doi: 10.1108/JES-01-2023-0034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giannerini S., Goracci G., Rahbek A. The validity of bootstrap testing for threshold autoregression. J. Econom. 2024;239(1) doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2023.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Im K.S., Pesaran M.H., Shin Y. Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. J. Econom. 2003;115(1):53–74. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4076(03)00092-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kao C. Spurious regression and residual-based tests for cointegration in panel data. J. Econom. 1999;90(1):1–44. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00023-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pedroni P. Critical values for cointegration tests in heterogeneous panels with multiple regressors. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 1999;61(SUPPL):653–670. doi: 10.1111/1468-0084.61.s1.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ssebulime K., Edward B. Budget deficit and inflation nexus in Uganda 1980–2016: a cointegration and error correction modeling approach. J. Econ. Struct. Dec. 2019;8(1) doi: 10.1186/s40008-019-0136-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Charles S., Marie J. A note on the competing causes of high inflation in Bulgaria during the 1990s: money supply or exchange rate? Rev. Polit. Econ. Jul. 2020;32(3):433–443. doi: 10.1080/09538259.2020.1787002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adaramola O.A., Dada O. Impact of inflation on economic growth: evidence from Nigeria. Invest. Manag. Financ. Innovat. 2020;17(2):1–13. doi: 10.21511/imfi.17(2).2020.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garriga A.C., Rodriguez C.M. More effective than we thought: central bank independence and inflation in developing countries. Econ. Modell. 2020;85:87–105. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2019.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Christelis D., Georgarakos D., Jappelli T., van Rooij M. Trust in the central bank and inflation expectations. 2020;16(5) doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3540974. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Naliaka Kwoba M. Impact of selected macro economic variables on foreign direct investment in Kenya. Int. J. Econ. Finance Manag. Sci. 2016;4(3):107. doi: 10.11648/j.ijefm.20160403.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data associated with this study is publicly available in Central Bank of Kenya (CBK), Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), China Economic Information Center (ceicdata.com), and www.indexmundi.com repositories.