abstract

In eukaryotes, microtubule polymers are essential for cellular plasticity and fate decisions. End-binding (EB) proteins serve as scaffolds for orchestrating microtubule polymer dynamics and are essential for cellular dynamics and chromosome segregation in mitosis. Here, we show that EB1 forms molecular condensates with TIP150 and MCAK through liquid–liquid phase separation to compartmentalize the kinetochore–microtubule plus-end machinery, ensuring accurate kinetochore–microtubule interactions during chromosome segregation in mitosis. Perturbation of EB1–TIP150 polymer formation by a competing peptide prevents phase separation of the EB1-mediated complex and chromosome alignment at the metaphase equator in both cultured cells and Drosophila embryos. Lys220 of EB1 is dynamically acetylated by p300/CBP-associated factor in early mitosis, and persistent acetylation at Lys220 attenuates phase separation of the EB1-mediated complex, dissolves droplets in vitro, and harnesses accurate chromosome segregation. Our data suggest a novel framework for understanding the organization and regulation of eukaryotic spindle for accurate chromosome segregation in mitosis.

Keywords: phase separation, mitosis, microtubule dynamics, EB1, acetylation

Introduction

In addition to intracellular transport, microtubule cytoskeleton polymers are essential for cell division and migration. Many fast-growing end-localized microtubule proteins are well known as plus-end-binding proteins (+TIPs), which can bind to each other to form a plus-end, membraneless, comet-like structure (Akhmanova and Steinmetz, 2008; Cheeseman and Desai, 2008, 2015). In mammalian cells, these comets are typically 1–2 μm in length and contain hundreds of plus-end-binding molecules (Akhmanova and Steinmetz, 2008). The highly dynamic turnover of these characterized +TIPs at the plus-ends orchestrates the dynamic instability and physiological function of microtubules (Howard and Hyman, 2003). However, it remains elusive how this comet-like structure modifies its morphology and tunes its mechanical properties and how +TIPs concentrate at the continuously growing and shrinking plus-ends.

End-binding (EB) family members are evolutionarily conserved proteins including EB1, EB2, and EB3 (Bu and Su, 2003; Vaughan, 2005). The N-terminus of EB1 consists of a calponin homology domain, which is necessary and sufficient for binding to microtubules and recognizing microtubule plus-ends (Vitre et al., 2008). The C-terminal coiled-coil (C-coil)-containing end-binding homology (EBH) domain mediates EB1 dimerization and microtubule plus-end binding (Bu and Su, 2003). The C-terminal tail of EB1 is flexible and contains a highly conserved acidic aromatic EEY motif. EB1 acts as a commander and recruits other +TIPs (Vaughan, 2005), such as TIP150, MCAK, p150Glued, and CLIP-170, to the plus-end comet (Perez et al., 1999; Askham et al., 2002; Slep and Vale, 2007; Lee et al., 2008; Jiang et al., 2009; Adams et al., 2016). These +TIPs can be categorized into two groups based on their distinct protein modules and linear sequence motifs that mediate their interaction characteristics (Akhmanova and Steinmetz, 2008). TIP150 and MCAK recognize the EBH domain of EB1 through the serine–any amino acid–isoleucine–proline (SxIP) sequence motif (Mennella et al., 2005; Jiang et al., 2009); however, p150Glued and CLIP-170 recognize the EEY motif of EB1 through the cytoskeleton-associated protein-glycine-rich (CAP-Gly) domain (Ligon et al., 2006; Hayashi et al., 2007; Weisbrich et al., 2007). Our recent work has demonstrated the importance of a hydrophobic cavity at the dimerized EB1 C-terminus (Xia et al., 2012), which is responsible for the interaction with +TIPs containing the SxIP motif. Although a recent cryo-EM study provided a mechanistic view of how EB proteins modulate structural transitions at growing microtubule plus-ends (Zhang et al., 2015a), the high-resolution 3D structure of EB1 remains unavailable due to its unstructured linker region.

Emerging evidence indicates the functional relevance of biomolecular condensates generated by liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) (Hyman et al., 2014; Su et al., 2016; Case et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2019a; Peeples and Rosen, 2021; Boyd-Shiwarski et al., 2022; Dall'Agnese et al., 2022; Sang et al., 2022). LLPS is driven by proteins containing intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) and facilitates interactions and biochemical reactions in locally confined compartments (Molliex et al., 2015; Nott et al., 2015; Wright and Dyson, 2015; Bergeron-Sandoval et al., 2016). Importantly, our recent studies suggest that microtubule plus-ends are compartmentalized by LLPS (Zhang et al., 2022; Song et al., 2023). Based on these findings, here, we show that EB1 undergoes synergistic LLPS with +TIPs TIP150 and MCAK, which is essential for accurate chromosome segregation in fly embryos and human cells. In addition, the LLPS-mediated organization of microtubule plus-end dynamics is regulated by acetylation of EB1 in mitosis.

Results

EB1 selectively forms coacervates with TIP150 and MCAK

Microtubule dynamics are driven by guanosine-5′-triphosphate hydrolysis within the lattice and by a number of microtubule plus-end regulators, such as EB1. In living cells, EB1 tracks growing microtubule ends, recognizing a structural state of the microtubule lattice that is dependent on its nucleotide content. Using grazing incidence structured illumination microscopy, we visualized that EB1 formed discrete comets in the cytoplasm and tracked microtubules in living cells (Jiang et al., 2009; Akhmanova and Steinmetz, 2015; Shin et al., 2017). However, to our surprise, EB1 comets underwent dynamic fusion. Additional characterization revealed that EB1 undergoes LLPS both in vitro and in vivo (Song et al., 2023).

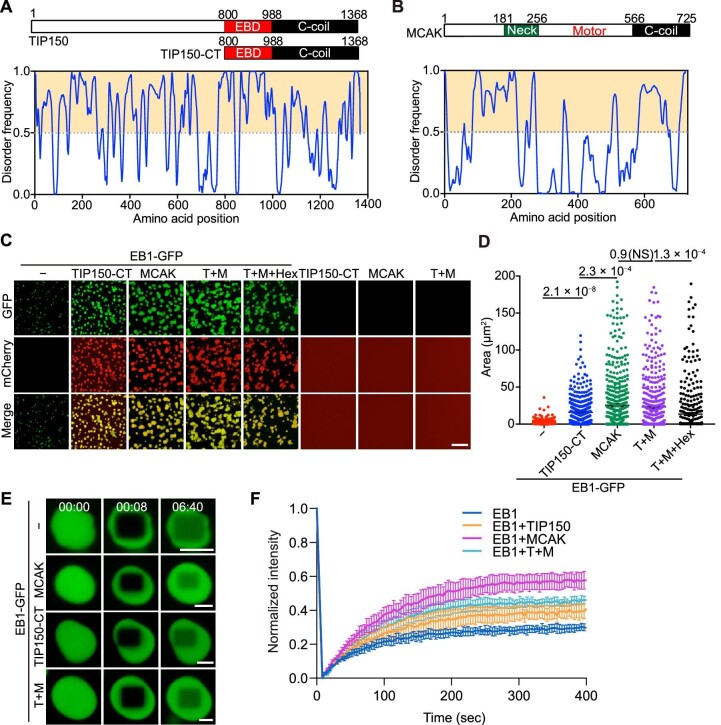

Hierarchical EB1–TIP150–MCAK interactions are known to be essential for chromosome alignment in mitosis (Jiang et al., 2009; Xia et al., 2012; Ward et al., 2013). However, the molecular delineation of these interactions has been hindered by the challenge of engineering soluble recombinant TIP150 protein. Full-length TIP150 appears to be largely unfolded and contains many IDRs (Figure 1A), which are important for interactions with EB1 and MCAK. The SLLP motif in the EB1 binding domain (EBD) of TIP150 is responsible for the interaction with EB1, and the C-coil domain of TIP150 is responsible for the interaction with MCAK (Jiang et al., 2009). Interestingly, the N-terminus of MCAK (aa 1–256), involved in TIP150 binding, also appears unfolded as predicted (Figure 1B). Next, we purified the C-terminal region of TIP150 (TIP150-CT; aa 800–1368), which specifies EB1 binding and MCAK binding (Supplementary Figure S1A). However, under the same experimental conditions as that for EB1, TIP150-CT or MCAK failed to form droplets in vitro over a wide range of protein and salt concentrations. Only in the presence of 5% PEG-8000 could TIP150-CT or MCAK form droplets in vitro (Supplementary Figure S1B). Then, we investigated the stoichiometry of the EB1–TIP150–MCAK association in droplet formation with the constant EB1 concentration and varying TIP150-CT and MCAK concentrations (Supplementary Figure S1C). Incubation of EB1 with TIP150-CT and/or MCAK additionally increased the spherical droplet size and number (Figure 1C). The addition of 1,6-hexanediol, known to induce the disruption of plus-end comets in vivo, also disrupted co-droplet formation in vitro (Figure 1C). Interestingly, no droplets were observed when TIP150-CT was mixed with MCAK, indicating that EB1 serves as the scaffold for organizing the compartmentalization of the protein mixtures (Figure 1C). Quantitative analyses demonstrated that TIP150 and MCAK synergistically promoted the formation of coacervates by decreasing the threshold of the EB1 condensate (Figure 1D). In the presence of PEG-8000 but absence of EB1, MCAK and TIP150 could form droplets, while the CAP-Gly domain-containing truncations of CLIP-1701–481 and p150Glued-1–120 could not (Supplementary Figure S1B). CLIP-170 and p150Glued are generally considered as modules for tubulin binding (Weisbrich et al., 2007), and our results indicated that the CAP-Gly domain of CLIP-170 and p150Glued play minimal roles in EB1 co-droplet formation. Interestingly, in the absence of PEG-8000, the addition of TIP150-CT or MCAK to EB1 promoted the formation and growth of co-droplets (Supplementary Figure S1C). These co-droplets of EB1 with TIP150-CT and/or MCAK exhibited greater resistance to high salt concentrations, up to 150 mM KCl, compared with EB1 droplets (Supplementary Figure S1D–F), suggesting that the EB1 coacervates are physiologically relevant.

Figure 1.

EB1 selectively forms coacervates with TIP150 and MCAK. (A and B) Schematic representations of the domain structures (upper) and sequence features (lower) of human TIP150 (A) and MCAK (B). TIP150-CT (aa 800–1368), containing the EBD and the C-coil domain, was used in this study. The line at 0.5 (y-axis) is the cut-off for disorder (>0.5) and order (<0.5) predictions. The VLXT predictor was used for disordered dispositions. (C) Representative micrographs showing enrichment of TIP150-CT and/or MCAK in EB1 droplets in BRB80 buffer. All protein concentrations were 20 μM. All groups are displayed using identical fluorescence image settings. TIP150-CT, TIP150-CT-mCherry; MCAK, MCAK-mCherry; T+M, TIP150-CT-mCherry + MCAK-mCherry. Hex, 1,6-hexanediol. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Statistical analyses of the droplet area shown in C (n = 560 droplets for each group). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (n = 3 bilogical repeats) and were examined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's multiple comparisons test. P-values are indicated. NS, not significant. (E) FRAP analysis of co-droplets formed by TIP150-CT and/or MCAK with EB1 (time shown as min:sec). All protein concentrations were 20 μM. Scale bar, 5 μm. (F) Quantitative analyses of the fluorescence inside the droplet over time shown in E. Data are presented as mean ± SEM at each time point (n = 6 droplets combined from three independent repeats).

EB1 binds to a large collection of accessory proteins and organizes fast exchanges at microtubule plus-ends. To test whether the synergistic formation of coacervates is a unique feature of co-condensation, fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) of the co-droplets was performed for molecular dynamics analysis. Surprisingly, FRAP analyses demonstrated that the fluorescence recovery of EB1 was dramatically promoted by the addition of TIP150-CT and/or MCAK, reflecting the synergistic effect of TIP150 and/or MCAK on the local rearrangement of EB1 molecules within the droplet (Figure 1E). Quantitative analyses indicated that coacervates formed by EB1 and TIP150/MCAK are highly dynamic (Figure 1F). Thus, we reasoned that EB1 selectively forms dynamic coacervates with TIP150 and MCAK to safeguard EB1 compartment turnover speed.

The LLPS-driven EB1 scaffold is regulated by PCAF-elicited acetylation

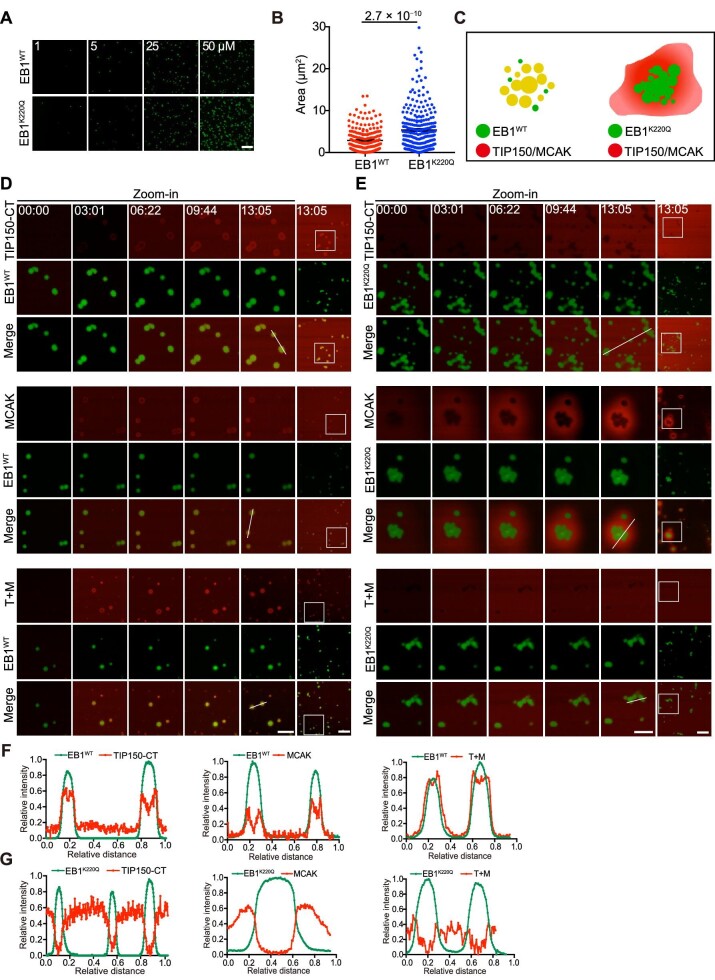

Despite extensive biochemical characterization of the interactions of EB1 with its binding proteins, the properties and dynamics of EB1 droplets/comets in vivo remain poorly illustrated. Having shown previously that dynamic acetylation of EB1 at Lys220 by p300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF) regulates kinetochore–microtubule attachments in mitosis (Xia et al., 2012), we next examined whether this modification also affects coacervate formation. Surprisingly, the acetylation-mimicking mutant of EB1 (EB1K220Q) exhibited a higher efficiency in droplet formation (Figure 2A), resulting in significantly larger droplet area compared with wild-type EB1 (EB1WT) (Figure 2B). FRAP analyses demonstrated similar molecular dynamics of the EB1K220Q droplets and EB1WT droplets (Supplementary Figure S2A). To assess whether the phase separation-driven compartmentalization of EB1 with TIP150 and/or MCAK is regulated as predicted by molecular modelling (Figure 2C), we developed a real-time monitoring method to observe co-droplet formation by adding TIP150 and/or MCAK to pre-existing EB1 droplets in vitro (Supplementary Figure S2B). As shown in Figure 2D, EB1WT formed micrometre-scale spherical droplets, and the added TIP150-CT and/or MCAK were prominently incorporated into EB1WT droplets. On the contrary, although EB1K220Q formed droplets, TIP150-CT or MCAK was not readily incorporated into these EB1K220Q droplets (Figure 2E). Line scans of fluorescence in the green and red channels confirmed that EB1WT droplets incorporated TIP150-CT and MCAK (Figure 2F) but EB1K220Q droplets excluded TIP150-CT or MCAK (Figure 2G), consistent with our previous finding that TIP150 failed to be incorporated into comets formed by EB1K220Q (Xia et al., 2012). Collectively, these results suggest that the LLPS-driven EB1 droplet serves as a scaffold for the selective enrichment of TIP150 and MCAK and the positive charge of Lys220 is important for recruiting EB1 clients.

Figure 2.

Lys220 is important for LLPS-driven EB1 scaffold organization. (A) Phase separation assay of purified GFP-tagged EB1WT and EB1K220Q at different concentrations. Images were acquired at room temperature. Scale bar, 20 μm. (B) Statistical analyses of the droplet area shown in A (n = 217 and 274 droplets for EB1WT and EB1K220Q, respectively). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3 biological repeats) and were examined by two-tailed Student's t-test. The P-value is indicated. (C) Schematic representation illustrating the co-phase separation between EB1 (EB1WT and EB1K220Q) and other +TIPs. (D and E) Time-lapse co-phase separation assay of GFP-tagged EB1WT (D) and EB1K220Q (E) with TIP150-CT and/or MCAK, observed by confocal microscopy (time is shown as min:sec). The left panels (scale bar, 5 μm) are enlarged views of the boxed area in the rightmost image (scale bar, 10 μm). TIP150-CT, TIP150-CT-mCherry; MCAK, MCAK-mCherry; T+M, TIP150-CT-mCherry + MCAK-mCherry. (F and G) Plot profiles of droplet fluorescence intensity along the indicated white lines shown in D and E, respectively.

The EB1–TIP150 interaction is essential for coacervate stability in vivo

Since the propensity for EB1 phase separation can be promoted by acetylation of EB1 at Lys220 and the interaction of EB1 with TIP150/MCAK, we examined whether manipulating the Lys220 acetylation status of EB1 and its interaction with TIP150 alters EB1 droplet/comet function and stability in microtubule tracking in live cells. To this end, we generated a membrane-permeable peptide containing aa 815–864 of TIP150 (the binding interface between EB1 and TIP150) and 11 amino acids derived from the TAT protein transduction domain with FITC label (FITC-TIP150-TAT peptide) to perturb the endogenous EB1–TIP150 interaction (Ward et al., 2013; Supplementary Figure S3A). As expected, the recombinant FITC-TIP150-TAT peptide competed with endogenous TIP150 and therefore disrupted the EB1–TIP150 association (Supplementary Figure S3B, lane 5).

Then, we determined EB1 droplet formation in COS-7 cells expressing OptoEB1, where a burst of blue light induced noticeable OptoEB1 droplets (Figure 3A; Supplementary Figure S3C). With phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) treatment, the OptoEB1 signal persisted for at least 30 min after blue light withdrawal, displaying consistent intensity (Figure 3A, top panel; enlarged inset). Conversely, FITC-TIP50-TAT peptide treatment reduced the intensity of these OptoEB1 droplets within 1 min (Figure 3A, bottom panel; enlarged inset). This observation, together with the quantified number of OptoEB1 droplets per unit area, suggests that disrupting the EB1–TIP150 interaction enhances the molecular dynamics of EB1, leading to the dissolution of EB1 droplets (Figure 3B). Thus, we concluded that the EB1–TIP150 interaction is essential for the LLPS scaffold property of EB1 in cells.

Figure 3.

The EB1–TIP150 interaction is essential for coacervate stability in vivo. (A) COS-7 cells transfected with EB1-mCherry-Cry2 were incubated with PBS or FITC-TIP150-TAT peptide (TIP150 peptide; at a final concentration of 10 μM) for 30 min and subjected to blue light opto-activation. Then, the light was switched off for droplet release (time is shown as min:sec). The rightmost panel (scale bar, 5 μm) shows the enlarged image of the boxed area in the left panels (scale bar, 10 μm) in each row. (B) Quantification of the number of OptoEB1 droplets during opto-activation and the subsequent release shown in A. (C) HeLa cells transfected with mCherry-H2B were treated with thymidine for 16 h and released from thymidine for 8 h. Then, the cells were treated with PBS or TIP150 peptide for 30 min before live cell imaging for 2 h. The paired white lines and arrows indicate the thickness of the metaphase plate and misaligned chromosomes, respectively. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Statistical analyses of the thickness of the metaphase plate shown in C. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3 biological repeats) and were examined by two-tailed Student's t-test. The P-value is indicated. For each group, 22 mitotic cells were quantified.

LLPS provides a potential mechanism for reducing noise in protein concentration, while droplet dissolution during mitosis results in the increased noise in protein concentration (Stoeger et al., 2016). To investigate the function of EB1 droplets in chromosome segregation during mitosis, we performed real-time imaging of HeLa cells expressing mCherry-H2B, pretreated with PBS or FITC-TIP150-TAT peptide. Cells pretreated with the PBS control entered anaphase at 30 min after nuclear envelope breakdown, while cells pretreated with FITC-TIP150-TAT peptide failed to reach anaphase onset even at 90 min after nuclear envelope breakdown (Figure 3C; Supplementary Figure S3D). To further examine chromosome congression (Zhang et al., 2015b), we examined the thickness of the metaphase plate in these cells. We found that in FITC-TIP150-TAT peptide-treated cells, most chromosomes congressed but were not fully aligned, and thus the thickness of the metaphase plate significantly increased (Figure 3D). In addition, FITC-TIP150-TAT peptide treatment also minimized the localization of MCAK at kinetochores during mitosis (Supplementary Figure S3D). These findings collectively indicated that the LLPS of EB1 induced by the EB1–TIP150 interaction plays a pivotal role in chromosome alignment, serving to filter out noise and ensure high precision in mitosis.

LLPS-driven EB1 coacervates are functionally and evolutionarily conserved

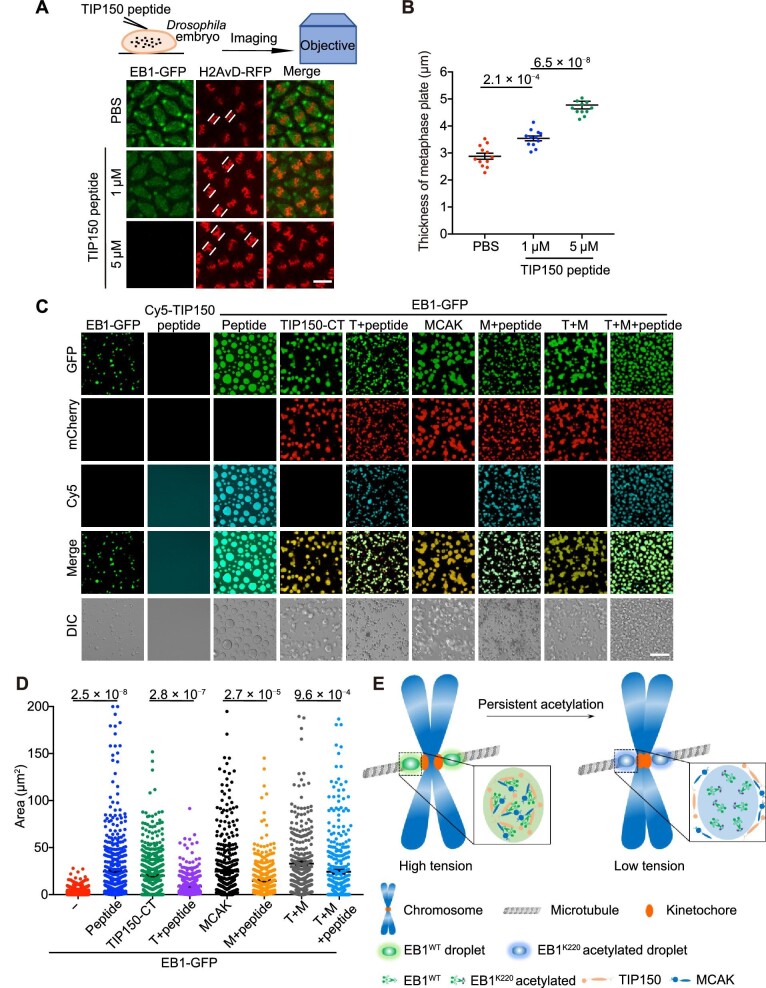

Drosophila melanogaster syncytial embryos provide an excellent model system for studying chromosome segregation, as metazoans have evolved an elaborate chromosome segregation machinery to ensure faithful genomic stability in mitosis (Wang et al., 2004; Huang et al., 2019b). Practically, Drosophila embryos also permit prompt delivery of competing peptides by microinjection techniques, thereby allowing manipulation of the protein machinery with ease and high precision. Microinjection of the EB1 antibody into Drosophila embryos resulted in defective chromosome segregation and anaphase onset (Rogers et al., 2002). Since the EB1–TIP150 interaction is conserved from Drosophila to humans (Jiang et al., 2009), we then employed real-time imaging to investigate chromosome movement in Drosophila embryos microinjected with EB1-GFP and Cy5-TIP150-TAT peptide (Figure 4A). Injected EB1-GFP readily localized to centrosomes and kinetochore microtubule plus-ends, consistent with earlier findings (Rogers et al., 2002). As shown in Figure 4A, proper chromosome segregation occurred during mitosis 13 in a PBS control-injected embryo (top panels). As predicted, microinjection of Cy5-TIP150-TAT peptide perturbed chromosome alignment, resulting in the typical phenotype of broad metaphase plates seen in EB1-depleted HeLa cells (Xia et al., 2012), which was concurrent with the reduction in EB1-GFP fluorescence at kinetochore microtubules and centrosomes (Figure 4A; middle panels), suggesting that EB1–TIP150 is important for the stable localization of EB1 droplets on kinetochore microtubules. Surprisingly, microinjection of a higher concentration of Cy5-TIP150-TAT peptide abolished the EB1 droplets at kinetochore microtubules and centrosomes, indicating that the formation of EB1 comets driven by LLPS in cells depends on the TIP150–EB1 interaction (Figure 4A; bottom panels). Consistent with the essential function of LLPS-driven EB1 droplets in mitosis, the loss of EB1 droplets resulted in persistent defects in chromosome alignment. Quantitative analyses of the thickness of the metaphase plate indicated that in Cy5-TIP150-TAT peptide-injected embryos, most chromosomes congressed but failed to align at the equator (Figure 4B). As correct kinetochore–microtubule attachments ensure accurate chromosome bi-orientation and segregation, we next examined kinetochore tension by measuring the interkinetochore distance across anti-centromere antibody (ACA)-labelled kinetochore pairs (Supplementary Figure S4A). As shown in Supplementary Figure S4B and C, Cy5-TIP150-TAT peptide treatment shortened the interkinetochore distance in a dose-depend manner, suggesting kinetochores under reduced tension. Furthermore, as shown in Supplementary Figure S4D, the addition of Cy5-TIP150-TAT peptide disrupted the localization of EB1, MCAK, and TIP150 at the kinetochore microtubule plus-ends. Thus, we concluded that EB1 droplets function in stabilizing microtubule–kinetochore associations.

Figure 4.

Phase separation of EB1 coacervates is functionally and evolutionarily conserved. (A) Schematic of the microinjection of EB1-GFP and Cy5-TIP150-TAT peptide (TIP150 peptide) into Drosophila embryos. Images show EB1-GFP and chromosome morphology in the absence or presence of TIP150 peptide at the indicated concentrations. The paired white lines indicate the thickness of the metaphase plate. Scale bar, 5 μm. (B) Statistical analyses of the thickness of the metaphase plate shown in A. For each group, 12 mitotic cells were quantified. (C) Representative micrographs showing the enrichment of TIP150-CT and/or MCAK in EB1-GFP droplets in the presence or absence of Cy5-TIP150-TAT peptide (peptide; 10 μM). All protein concentrations were 10 μM. TIP150-CT, TIP150-CT-mCherry; MCAK, MCAK-mCherry; T+M, TIP150-CT-mCherry + MCAK-mCherry. DIC, differential interference contrast. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Statistical analyses of the droplet area shown in C (n = 678, 503, 503, 539, 455, 471, 405, and 450 droplets, respectively). In B and D, data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3 biological repeats) and were examined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test. P-values are indicated. (E) This model illustrates how EB1 dynamically organizes compartmentalization to precisely distribute microtubule plus-end regulators, including MCAK and TIP150.

To confirm that the competing peptide disrupts EB1 droplets in vitro, Cy5-TIP150-TAT peptide was added into EB1 droplets and EB1–TIP150 co-droplets. As shown in Figure 4C and D, the addition of Cy5-TIP150-TAT peptide promoted the formation and growth of EB1 droplets due to the extension of multivalent interactions between EB1 and the peptide but inhibited and disrupted the growth of EB1 co-droplets with TIP150-CT and/or MCAK in vitro, indicating that the synthetic Cy5-TIP150-TAT peptide competes with the recombinant TIP150-CT protein for interacting with EB1. Thus, we concluded that TIP150 synergizes with EB1 for LLPS-driven compartmentalization to organize a dynamic hub for kinetochore–microtubule interactions to achieve accurate chromosome alignment.

Discussion

The mitotic spindle is a specialized membraneless organelle that contributes to maintaining genome stability during mitosis by orchestrating accurate chromosome segregation (Pearson and Bloom, 2004; Akhmanova and Steinmetz, 2008; Kiyomitsu and Cheeseman, 2012). Emerging evidence suggests a critical role for LLPS-driven assembly of compartments on mitotic chromosomes, such as centromeres and telomeres, in cell division control. Here, we demonstrated that EB1-mediated LLPS orchestrates the microtubule plus-end compartmentalization, a process regulated by PCAF-elicited acetylation during mitosis. Our results identified reversible acetylation of EB1 as a molecular mechanism underlying LLPS-driven compartmentalization at the kinetochore, and we offered a comprehensive perspective on the regulatory mechanism influencing interactions between EB1 and +TIPs, coupled with the control of droplet plasticity (Figure 4E). In follow-up work, it will be of great interest to delineate how the dimerization of TIP150 and EB1 is regulated during mitosis using context-oriented 3D organoids (Yao and Smolka, 2019; Yao, 2020).

Microtubule dynamics are essential for numerous biological events, such as cell division, cell migration, and intracellular material transport. Among the microtubule plus-end tracking proteins, EB1 assumes a central role in regulating microtubule dynamics. The collaboration between EB1 and +TIPs, facilitated by SxIP motif- and CAP-Gly domain-mediated EB1 binding, exhibits distinct abilities in promoting LLPS. These differences have significant implications for microtubule plus-end tracking and the regulation of EB1 droplets. Functional analyses of EB1-tracking proteins have shown that CAP-Gly domain-based EB1-binding proteins such as CLIP-170 and p150Glued are regulated by phosphorylation in a context-dependent manner (Vaughan et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2019), while SxIP motif-based EB1-binding proteins such as TIP150 and MCAK are regulated by acetylation during mitosis (Xia et al., 2012). Importantly, the synergistic LLPS of EB1–TIP150–MCAK was disrupted by the addition of a competing TIP150 peptide, confirming our previous discovery of hierarchical interactions among these three +TIPs (Jiang et al., 2009; Ward et al., 2013). During the revision of our manuscript, multiple studies, including our own, have reported the orchestration of microtubule plus-ends by LLPS by demonstrating the ability of plus-end tracking proteins to form condensates from yeast to humans (Maan et al., 2023; Meier et al., 2023; Miesch et al., 2023; Song et al., 2023). In particular, our findings indicated that positively charged amino acids within the IDR are essential for EB1 LLPS and the architecture of its microtubule plus-end tracking protein complex (Song et al., 2023). Collectively, our results suggest that phase separation is an important mechanism that enables passive noise filtering and organizes SxIP motif-based tracking mechanisms to robustly control condensation turnover and therefore provides ‘sequence’- and LLPS-based physicochemical specificity.

It has been reported that the spindle matrix protein BuGZ exhibits LLPS-elicited microtubule-binding activity and regulates spindle plasticity (Jiang et al., 2015). Using in vitro reconstitution, Siahaan et al. (2019) have shown that tau molecules on microtubules cooperatively form cohesive islands that are kinetically distinct from those diffusing individually on microtubules, suggesting that a microtubule-dependent LLPS involving tau constitutes an adaptable protective layer on the microtubule surface. Post-translational modifications of EB1, such as phosphorylation, acetylation, and crotonylation, play a crucial role in regulating microtubule dynamics, spindle assembly checkpoint signalling, and spindle organization (Xia et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2019; Song et al., 2021). Investigating the regulatory mechanisms of acetylation and crotonylation on plus-end condensates, with acetylation occurring at the kinetochore–microtubule interface and crotonylation taking place at the spindle pole to the cell cortex, holds great promise for future research. The exciting challenges ahead are to define the chemistry of the EB1 code in a physiological and pathological context-dependent manner.

Materials and methods

Plasmids

The EB1-GFP constructs were generated by inserting human EB1 into pEGFP-N1 (Clontech). To generate EB1-GFP-His, EB1 was amplified together with GFP from the pEGFP-N1-EB1 plasmid by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and cloned into the pET-22b(+) vector (Novagen) by NdeI and XhoI digestion. To generate TIP150-CT-mCherry-His, MCAK-mCherry-His, CLIP-1701–481-mCherry-His, and p150Glued-1–120-mCherry-His constructs, sequences of TIP150-CT (aa 800–1368), MCAK (aa 1–725), CLIP-170 (aa 1–481), and p150Glued (aa 1–120) were cloned into the pET-22b(+) vector by NdeI and BamHI digestion, followed by PCR-amplified mCherry gene insertion via BamHI and XhoI. The EB1 truncation plasmids were generated by PCR amplification as described for the EB1-GFP-His plasmid, and the mutants were introduced by the Mut Express II Fast Mutagenesis Kit (Vazyme). All the constructs were sequenced by General Biology Technology.

Antibodies and chemicals

The following antibodies were purchased: anti-EB1 antibody (BD Biosciences; 610534), anti-α-tubulin monoclonal antibody (Sigma, T9026), anti-α-tubulin antibody (FITC-DM1A; Sigma, F2168), ACA (Immunovision, HCT-0100), anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma, F3165), anti-GFP antibody (Sigma, G6539), and anti-MCAK antibody (Santa Cruz, sc81305). The anti-TIP150 antibody was homemade as described previously (Jiang et al., 2009). All the secondary antibodies used were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch. The following chemicals were used: PEG-8000 (Sangon Biotech, A600433) and 1,6-hexanediol (Sigma, 88571).

Protein purification

Recombinant proteins were purified from the Escherichia coli strain Rosetta (DE3) as described previously (Ding et al., 2019). Basically, the plasmids were transformed into the E. coli strain Rosetta (DE3), and protein expression was induced with 0.2 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside at 16°C. Bacteria expressing EB1 or other +TIPs were harvested and lysed by sonication in Ni-NTA binding buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, pH8.0, 300 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole) supplemented with 1 mM dithiothreitol and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 12000 rpm for 1 h at 4°C. The clarified lysate was incubated with Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) for 45 min at 4°C. The agarose was washed three times in Ni-NTA binding buffer supplemented with 20 mM imidazole and eluted with Ni-NTA binding buffer supplemented with 250 mM imidazole. The eluted protein was concentrated to ∼100 mM with Amicon Ultra-4 Centrifugal Filter Unit (Millipore, UFC803096) before frozen at −80°C or desalted in BRB80 buffer (80 mM PIPES, pH 6.8, 1 mM EGTA, and 1 mM MgCl2) for experiments.

Phase separation assay

Phase separation was induced by diluting the indicated amount of EB1 and other +TIPs in BRB80 buffer to achieve the indicated final concentrations of protein and KCl. To induce phase separation in the presence of a molecular crowding agent, EB1 or its truncation at the indicated concentration was incubated in BRB80 buffer containing 5% PEG-8000. Phase separation was observed by adding a drop of the reaction mixture onto glass-bottom culture dishes (MatTek) and then imaging the droplet on a Zeiss 880 laser confocal scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss) with a 63× Plan-Apochromat 1.4 oil immersion lens by fluorescence and differential interference contrast imaging. For time-lapse imaging of droplet fusion, droplets were formed under the indicated conditions and immediately imaged under a microscope every second.

FRAP analysis

FRAP experiments were performed on a Zeiss 880 laser confocal scanning microscope with a 63× Plan-Apochromat 1.4 oil immersion lens. A 488-nm laser beam was used for EB1WT-GFP-His and EB1K220Q-GFP-His, and a 594-nm laser beam was used for TIP150-CT-mCherry-His, MCAK-mCherry-His, CLIP-1701–481-mCherry-His, p150Glued-1–120-mCherry-His, and OptoEB1. Images were processed using ImageJ, and the statistical data were evaluated with GraphPad Prism 6 software.

Cell culture, immunofluorescence, and live cell imaging

HeLa, HEK293T, and COS-7 (American Type Culture Collection) cells were maintained as sub-confluent monolayers in advanced Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone), 100 units/ml penicillin (Gibco), and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco) at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells were transfected with plasmids using Lipofectamine 3000 according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). For immunofluorescence analysis, transfected cells were fixed with pre-cooled methanol or 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min (Xia et al., 2012). After blocking with PBST (PBS with 0.05% Tween-20) buffer containing 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) for 45 min at room temperature, the fixed cells were incubated with primary antibodies in a humidified chamber for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with secondary antibodies for 1 h at 37°C. The DNA was stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole from Sigma. Images were captured by DeltaVision softWoRx software (Applied Precision) and processed by deconvolution and z-stack projection.

For time-lapse imaging, HeLa cells were cultured in glass-bottom culture dishes and maintained in CO2-independent media supplemented with 10% FBS and 2 mM glutamine (Mo et al., 2016). During imaging, the dishes were placed in a sealed chamber at 37°C. Images of living cells were taken with a DeltaVision microscopy system.

OptoEB1 droplet assay

The OptoEB1 plasmid (EB1-mCherry-Cry2) was constructed by replacing FUSN with EB1 in the pHR-FUSN-mCh-Cry2WT plasmid (Addgene, 101223). COS-7 cells were cultured in glass-bottom culture dishes for 24 h and transfected with EB1-mCherry-Cry2. After 24 h, the cells were imaged using a Zeiss 880 laser confocal scanning microscope with a 63× Plan-Apochromat 1.4 oil immersion lens in a humidified chamber maintained at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. To induce phase separation, the cells were exposed to 488-nm-wavelength light every 5 sec, and single z-plane images were taken in the 568-nm channel to observe droplet formation. Quantification of droplet number was performed according to the online procedure (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Immunoprecipitation assay

For immunoprecipitation, HEK293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmids were trypsinized and lysed in EBC buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 120 mM NaCl, and 0.5% NP-40) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Mo et al., 2016; Ding et al., 2019). The lysate was incubated with FLAG M2 beads (Sigma) at 4°C for 4 h with gentle rotation (Yao et al., 2000). The FLAG M2 beads were then spun down and washed three times with lysis buffer before being resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies.

Microinjection and live imaging

Embryos of D. melanogaster stably expressing H2AvD-RFP were cultured on standard yeast-cornmeal-agar media. Before injection, we set up cages at 25°C using 3- to 6-day-old flies and changed the plates frequently. Embryos were collected on grape-agar plates for 30 min and then aged at 25°C to the appropriate stage. They were transferred with a fine brush into a nylon-mesh basket and washed at room temperature with distilled water. Embryos were dechorionated for 2 min in 50% bleach, washed thoroughly with distilled water, aligned under a dissecting microscope on a grape-agar plate, and affixed to a coverslip with glue made from Scotch double-sided tape (3M) immersed in heptane. The embryos were desiccated for 8–9 min (depending on the air humidity) and then covered in halocarbon oil (Sigma–Aldrich). Microinjection needles were made using a micropipette puller (WPI). Embryos were staged by viewing on a confocal microscope until the majority were at the appropriate stage, whereupon they were injected on an ortho-microscope. Embryos were imaged on a Zeiss 880 laser confocal scanning microscope.

Fluorescence intensity quantification

The fluorescence intensity of the droplets was quantified as described previously using ImageJ (Fu et al., 2009; Dou et al., 2015; Yuan and O'Farrell, 2015). In brief, the average pixel intensities from no less than the indicated number of randomly selected droplets were measured, and the background pixel intensities were subtracted.

Interkinetochore distance measurement

Interkinetochore distance was measured based on a previously published method (Yang et al., 2008). Images were acquired using a DeltaVision microscopy system. The fluorescence intensities of ACA-labelled kinetochore pairs were measured along the line between the two sister kinetochores, and the position of the peak intensity at each kinetochore was determined manually. The distance between paired sister kinetochores marked with ACA was statistically analysed using ImageJ.

Peptides

FITC-TIP150-TAT and Cy5-TIP150-TAT peptides were synthesized by Hefei KS-V Peptide Biological Technology Co., Ltd. The full sequence of the peptide is SADLKKASSSNAAKSNLPKSGLRPPGYSRLPAAKLAAFGFVRSSSVSSVS (aa 815–864 of TIP150)-YGRKKRRQRR (TAT), with FITC or Cy5 label in the first amino acid (serine). The peptides were reconstituted at 400 mM in BRB80 buffer for in vitro assays and in PBS for in vivo assays. Before use, the peptides were centrifuged at 13000 rpm at 4°C for 20 min.

Sequence analysis of the disordered and low-complexity protein regions

The PONDR (http://www.disprot.org/index.php) (Xue et al., 2010) and SEG (http://mendel.imp.ac.at/METHODS/seg.server.html) (Wootton, 1994) programs were used to analyse the disordered and low-complexity regions of EB1 and other +TIPs with default settings.

Statistics

All the statistical analyses are described in the figure legends.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Prof. Yunyu Shi and Prof. Xuebiao Yao (University of Science & Technology of China) for their support and Prof. Iain M. Cheeseman (Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research) for the reagents.

Contributor Information

Fengrui Yang, MOE Key Laboratory for Membraneless Organelles & Cellular Dynamics, Hefei National Research Center for Cross-disciplinary Sciences, Center for Advanced Interdisciplinary Science and Biomedicine of IHM, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China; Anhui Key Laboratory for Cellular Dynamics and Chemical Biology, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China; Keck Center for Organoids Plasticity, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30310, USA.

Mingrui Ding, MOE Key Laboratory for Membraneless Organelles & Cellular Dynamics, Hefei National Research Center for Cross-disciplinary Sciences, Center for Advanced Interdisciplinary Science and Biomedicine of IHM, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China.

Xiaoyu Song, MOE Key Laboratory for Membraneless Organelles & Cellular Dynamics, Hefei National Research Center for Cross-disciplinary Sciences, Center for Advanced Interdisciplinary Science and Biomedicine of IHM, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China; Anhui Key Laboratory for Cellular Dynamics and Chemical Biology, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China; Keck Center for Organoids Plasticity, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30310, USA.

Fang Chen, Hunan Key Laboratory of Molecular Precision Medicine, Central South University, Changsha 410083, China.

Tongtong Yang, MOE Key Laboratory for Membraneless Organelles & Cellular Dynamics, Hefei National Research Center for Cross-disciplinary Sciences, Center for Advanced Interdisciplinary Science and Biomedicine of IHM, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China; Anhui Key Laboratory for Cellular Dynamics and Chemical Biology, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China.

Chunyue Wang, MOE Key Laboratory for Membraneless Organelles & Cellular Dynamics, Hefei National Research Center for Cross-disciplinary Sciences, Center for Advanced Interdisciplinary Science and Biomedicine of IHM, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China; Anhui Key Laboratory for Cellular Dynamics and Chemical Biology, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China.

Chengcheng Hu, MOE Key Laboratory for Membraneless Organelles & Cellular Dynamics, Hefei National Research Center for Cross-disciplinary Sciences, Center for Advanced Interdisciplinary Science and Biomedicine of IHM, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China; Anhui Key Laboratory for Cellular Dynamics and Chemical Biology, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China.

Qing Hu, MOE Key Laboratory for Membraneless Organelles & Cellular Dynamics, Hefei National Research Center for Cross-disciplinary Sciences, Center for Advanced Interdisciplinary Science and Biomedicine of IHM, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China; Anhui Key Laboratory for Cellular Dynamics and Chemical Biology, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China.

Yihan Yao, MOE Key Laboratory for Membraneless Organelles & Cellular Dynamics, Hefei National Research Center for Cross-disciplinary Sciences, Center for Advanced Interdisciplinary Science and Biomedicine of IHM, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China.

Shihao Du, MOE Key Laboratory for Membraneless Organelles & Cellular Dynamics, Hefei National Research Center for Cross-disciplinary Sciences, Center for Advanced Interdisciplinary Science and Biomedicine of IHM, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China; Anhui Key Laboratory for Cellular Dynamics and Chemical Biology, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China.

Phil Y Yao, Anhui Key Laboratory for Cellular Dynamics and Chemical Biology, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China; Keck Center for Organoids Plasticity, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30310, USA.

Peng Xia, MOE Key Laboratory for Membraneless Organelles & Cellular Dynamics, Hefei National Research Center for Cross-disciplinary Sciences, Center for Advanced Interdisciplinary Science and Biomedicine of IHM, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China; Anhui Key Laboratory for Cellular Dynamics and Chemical Biology, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China.

Gregory Adams Jr, Anhui Key Laboratory for Cellular Dynamics and Chemical Biology, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China; Keck Center for Organoids Plasticity, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30310, USA.

Chuanhai Fu, MOE Key Laboratory for Membraneless Organelles & Cellular Dynamics, Hefei National Research Center for Cross-disciplinary Sciences, Center for Advanced Interdisciplinary Science and Biomedicine of IHM, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China; Anhui Key Laboratory for Cellular Dynamics and Chemical Biology, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China; Keck Center for Organoids Plasticity, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30310, USA.

Shengqi Xiang, MOE Key Laboratory for Membraneless Organelles & Cellular Dynamics, Hefei National Research Center for Cross-disciplinary Sciences, Center for Advanced Interdisciplinary Science and Biomedicine of IHM, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China.

Dan Liu, MOE Key Laboratory for Membraneless Organelles & Cellular Dynamics, Hefei National Research Center for Cross-disciplinary Sciences, Center for Advanced Interdisciplinary Science and Biomedicine of IHM, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China.

Zhikai Wang, MOE Key Laboratory for Membraneless Organelles & Cellular Dynamics, Hefei National Research Center for Cross-disciplinary Sciences, Center for Advanced Interdisciplinary Science and Biomedicine of IHM, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China; Anhui Key Laboratory for Cellular Dynamics and Chemical Biology, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China; Keck Center for Organoids Plasticity, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30310, USA.

Kai Yuan, Hunan Key Laboratory of Molecular Precision Medicine, Central South University, Changsha 410083, China.

Xing Liu, MOE Key Laboratory for Membraneless Organelles & Cellular Dynamics, Hefei National Research Center for Cross-disciplinary Sciences, Center for Advanced Interdisciplinary Science and Biomedicine of IHM, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China; Anhui Key Laboratory for Cellular Dynamics and Chemical Biology, University of Science & Technology of China, Hefei 230027, China.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFA1303100, 2022YFA0806800, 2022YFA1302700, and 2017YFA0503600), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32090040, 92153302, 92254302, 92253305, 31621002, 21922706, 92059102, and 92253301), the Plans for Major Provincial Science & Technology Projects of Anhui Province (202303a0702003), the Ministry of Education (IRT_17R102), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (KB9100000007 and KB9100000013).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Author contributions: X.L., K.Y., and Z.W. conceived the project. F.Y., M.D., X.S., T.Y., C.H., and Q.H. carried out the experiments. Y.Y., S.D., P.Y.Y., P.X., G.A., C.W., S.X., D.L., and C.F. contributed the reagents. K.Y., Z.W., and X.L. wrote the manuscript. All the authors commented on the manuscript.

References

- Adams G. Jr, Zhou J., Wang W.et al. (2016). The microtubule plus end tracking protein TIP150 interacts with cortactin to steer directional cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 20692–20706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhmanova A., Steinmetz M.O. (2008). Tracking the ends: a dynamic protein network controls the fate of microtubule tips. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 309–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhmanova A., Steinmetz M.O. (2015). Control of microtubule organization and dynamics: two ends in the limelight. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 711–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askham J.M., Vaughan K.T., Goodson H.V.et al. (2002). Evidence that an interaction between EB1 and p150Glued is required for the formation and maintenance of a radial microtubule array anchored at the centrosome. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 3627–3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron-Sandoval L.P., Safaee N., Michnick S.W. (2016). Mechanisms and consequences of macromolecular phase separation. Cell 165, 1067–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Shiwarski C.R., Shiwarski D.J., Griffiths S.E.et al. (2022). WNK kinases sense molecular crowding and rescue cell volume via phase separation. Cell 185, 4488–4506.e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu W., Su L.K. (2003). Characterization of functional domains of human EB1 family proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 49721–49731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case L.B., Zhang X., Ditlev J.A.et al. (2019). Stoichiometry controls activity of phase-separated clusters of actin signaling proteins. Science 363, 1093–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman I.M., Desai A. (2008). Molecular architecture of the kinetochore–microtubule interface. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Cao Y., Dong D.et al. (2019). Regulation of mitotic spindle orientation by phosphorylation of end binding protein 1. Exp. Cell. Res. 384, 111618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dall'Agnese A., Platt J.M., Zheng M.M.et al. (2022). The dynamic clustering of insulin receptor underlies its signaling and is disrupted in insulin resistance. Nat. Commun. 13, 7522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding M., Jiang J., Yang F.et al. (2019). Holliday junction recognition protein interacts with and specifies the centromeric assembly of CENP-T. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 968–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou Z., Liu X., Wang W.et al. (2015). Dynamic localization of Mps1 kinase to kinetochores is essential for accurate spindle microtubule attachment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, E4546–E4555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu C., Ward J.J., Loiodice I.et al. (2009). Phospho-regulated interaction between kinesin-6 Klp9p and microtubule bundler Ase1p promotes spindle elongation. Dev. Cell 17, 257–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi I., Plevin M.J., Ikura M. (2007). CLIP170 autoinhibition mimics intermolecular interactions with p150Glued or EB1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 980–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J., Hyman A.A. (2003). Dynamics and mechanics of the microtubule plus end. Nature 422, 753–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W.Y.C., Alvarez S., Kondo Y.et al. (2019). A molecular assembly phase transition and kinetic proofreading modulate Ras activation by SOS. Science 363, 1098–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Lin L., Liu X.et al. (2019). BubR1 phosphorylates CENP-E as a switch enabling the transition from lateral association to end-on capture of spindle microtubules. Cell Res. 29, 562–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman A.A., Weber C.A., Julicher F. (2014). Liquid–liquid phase separation in biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 30, 39–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Wang S., Huang Y.et al. (2015). Phase transition of spindle-associated protein regulate spindle apparatus assembly. Cell 163, 108–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang K., Wang J., Liu J.et al. (2009). TIP150 interacts with and targets MCAK at the microtubule plus ends. EMBO Rep. 10, 857–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyomitsu T., Cheeseman I.M. (2012). Chromosome- and spindle-pole-derived signals generate an intrinsic code for spindle position and orientation. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 311–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T., Langford K.J., Askham J.M.et al. (2008). MCAK associates with EB1. Oncogene 27, 2494–2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligon L.A., Shelly S.S., Tokito M.K.et al. (2006). Microtubule binding proteins CLIP-170, EB1, and p150Glued form distinct plus-end complexes. FEBS Lett. 580, 1327–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maan R., Reese L., Volkov V.A.et al. (2023). Multivalent interactions facilitate motor-dependent protein accumulation at growing microtubule plus-ends. Nat. Cell Biol. 25, 68–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier S.M., Farcas A.M., Kumar A.et al. (2023). Multivalency ensures persistence of a +TIP body at specialized microtubule ends. Nat. Cell Biol. 25, 56–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennella V., Rogers G.C., Rogers S.L.et al. (2005). Functionally distinct kinesin-13 family members cooperate to regulate microtubule dynamics during interphase. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 235–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miesch J., Wimbish R.T., Velluz M.C.et al. (2023). Phase separation of +TIP networks regulates microtubule dynamics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci USA 120, e2301457120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo F., Zhuang X., Liu X.et al. (2016). Acetylation of Aurora B by TIP60 ensures accurate chromosomal segregation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12, 226–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molliex A., Temirov J., Lee J.et al. (2015). Phase separation by low complexity domains promotes stress granule assembly and drives pathological fibrillization. Cell 163, 123–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nott T.J., Petsalaki E., Farber P.et al. (2015). Phase transition of a disordered nuage protein generates environmentally responsive membraneless organelles. Mol. Cell 57, 936–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson C.G., Bloom K. (2004). Dynamic microtubules lead the way for spindle positioning. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 481–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeples W., Rosen M.K. (2021). Mechanistic dissection of increased enzymatic rate in a phase-separated compartment. Nat. Chem. Biol. 17, 693–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez F., Diamantopoulos G.S., Stalder R.et al. (1999). CLIP-170 highlights growing microtubule ends in vivo. Cell 96, 517–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers S.L., Rogers G.C., Sharp D.J.et al. (2002). Drosophila EB1 is important for proper assembly, dynamics, and positioning of the mitotic spindle. J. Cell Biol. 158, 873–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang D., Shu T., Pantoja C.F.et al. (2022). Condensed-phase signaling can expand kinase specificity and respond to macromolecular crowding. Mol. Cell 82, 3693–3711.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin Y., Berry J., Pannucci N.et al. (2017). Spatiotemporal control of intracellular phase transitions using light-activated opto droplets. Cell 168, 159–171.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siahaan V., Krattenmacher J., Hyman A.A.et al. (2019). Kinetically distinct phases of tau on microtubules regulate kinesin motors and severing enzymes. Nat. Cell Biol. 21, 1086–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slep K.C., Vale R.D. (2007). Structural basis of microtubule plus end tracking by XMAP215, CLIP-170, and EB1. Mol. Cell 27, 976–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X., Yang F., Liu X.et al. (2021). Dynamic crotonylation of EB1 by TIP60 ensures accurate spindle positioning in mitosis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 17, 1314–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X., Yang F., Yang T.et al. (2023). Phase separation of EB1 guides microtubule plus-end dynamics. Nat. Cell Biol. 25, 79–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeger T., Battich N., Pelkmans L. (2016). Passive noise filtering by cellular compartmentalization. Cell 164, 1151–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X., Ditlev J.A., Hui E.et al. (2016). Phase separation of signaling molecules promotes T cell receptor signal transduction. Science 352, 595–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan K.T. (2005). TIP maker and TIP marker; EB1 as a master controller of microtubule plus ends. J. Cell Biol. 171, 197–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan P.S., Miura P., Henderson M.et al. (2002). A role for regulated binding of p150Glued to microtubule plus ends in organelle transport. J. Cell Biol. 158, 305–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitre B., Coquelle F.M., Heichette C.et al. (2008). EB1 regulates microtubule dynamics and tubulin sheet closure in vitro. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 415–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Hu X., Ding X.et al. (2004). Human Zwint-1 specifies localization of Zeste White 10 to kinetochores and is essential for mitotic checkpoint signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 54590–54598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward T., Wang M., Liu X.et al. (2013). Regulation of a dynamic interaction between two microtubule-binding proteins, EB1 and TIP150, by the mitotic p300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF) orchestrates kinetochore microtubule plasticity and chromosome stability during mitosis. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 15771–15785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisbrich A., Honnappa S., Jaussi R.et al. (2007). Structure–function relationship of CAP-Gly domains. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 959–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootton J.C. (1994). Non-globular domains in protein sequences: automated segmentation using complexity measures. Comput. Chem. 18, 269–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright P.E., Dyson H.J. (2015). Intrinsically disordered proteins in cellular signalling and regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia P., Wang Z., Liu X.et al. (2012). EB1 acetylation by P300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF) ensures accurate kinetochore–microtubule interactions in mitosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 16564–16569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue B., Dunbrack R.L., Williams R.W.et al. (2010). PONDR-FIT: a meta-predictor of intrinsically disordered amino acids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1804, 996–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Wu F., Ward T.et al. (2008). Phosphorylation of HsMis13 by Aurora B kinase is essential for assembly of functional kinetochore. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 26726–26736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X. (2020). Modeling cellular polarity, plasticity, and disease disparity in 4D. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 559–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X., Abrieu A., Zheng Y.et al. (2000). CENP-E forms a link between attachment of spindle microtubules to kinetochores and the mitotic checkpoint. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 484–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X., Smolka A.J. (2019). Gastric parietal cell physiology and helicobacter pylori-induced disease. Gastroenterology 156, 2158–2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan K., O'Farrell P.H. (2015). Cyclin B3 is a mitotic cyclin that promotes the metaphase–anaphase transition. Curr. Biol. 25, 811–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Yang F., Wang W.et al. (2022). SKAP interacts with Aurora B to guide end-on capture of spindle microtubules via phase separation. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 841–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Alushin G.M., Brown A.et al. (2015). Mechanistic origin of microtubule dynamic instability and its modulation by EB proteins. Cell 162, 849–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Zhu Q., Tian T.et al. (2015). Identification of RNAIII-binding proteins in Staphylococcus aureus using tethered RNAs and streptavidin aptamers based pull-down assay. BMC Microbiol. 15, 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.