Abstract

Utilizing waste heat to drive thermodynamic systems is imperative for improving energy efficiency, thereby improving sustainability. A combined cooling and power systems (CCP) utilizes heat from a temperature source to deliver both power and cooling. However, CCP systems utilizing LNG cold energy suffers from low second law efficiency due to significant temperature differences. To address this, an “Advanced Power and Cooling with LNG Utilization (ACPLU)” system is proposed, integrating a cascaded transcritical carbon dioxide (TCO2)-LNG cycle with an Organic Rankine cycle (ORC) for improved power generation and an absorption refrigeration system (ARS) for simultaneous cooling. This study evaluates the second law efficiency, net work output, and exergy destruction performance through a sensitivity analysis, optimizing variables such as heat source temperature, superheater temperature difference, ORC and CO2 turbine inlet and condenser pressures, evaporator temperature, and pinch point temperatures of heat exchangers and generator. Compared to previous studies on CCP systems, the ACPLU shows a superior performance, with a second law efficiency of 27.3 % and a net work output of 11.76 MW. Cyclopentane as an ORC working fluid resulted in the highest second law efficiency of 29.06 % and net work output of 12.27 MW. Parametric analysis suggested that heat source temperature significantly impacts net power output. The exergy analysis concluded that a high-pressure ratio and good thermal match between the heat exchangers enhance overall performance. Utilizing artificial neural network (ANN) to produce a multiple-input-multiple-output (MIMO) objective function and performing multi-objective optimization (MOO) using genetic algorithm (GA), an improved second law efficiency and net power output by 28.11 % and 14.16 MW respectively, with pentane as the working fluid, is demonstrated. An average cost rate of 9.121 $/GJ was observed through a thermo-economic analysis. The ACPLU system is promising for medium temperature waste heat recovery, such as, pharmaceutical manufacturing plants.

Keywords: Waste heat recovery, Multi-objective optimization, Exergy analysis, Cascade power cycle, Absorption refrigeration, Thermo-economic analysis

Highlights

-

•

A novel advanced cascaded combined cooling and power (CCP) system is proposed.

-

•

LNG cold energy is utilized as a heat sink for Transcritical CO2 cycle and ARS.

-

•

The ACPLU system achieves greater performance than previously reported systems.

-

•

A maximum second law efficiency and net work of 29.06 % and 12.27 MW is reported.

-

•

Multi-objective optimization using Artificial Neural Network and Genetic Algorithm.

Nomenclature

| Abbreviation | |

|---|---|

| ORC | Organic Rankine cycle |

| TCO2 | Transcritical carbon dioxide |

| LNG | Liquefied natural gas |

| ARS | Absorption refrigeration system |

| HPHE | High-pressure heat exchanger |

| LPHE | Low-pressure heat exchanger |

| ARSHE | ARS heat exchanger |

| SHX | Solution heat exchanger |

| EV1, EV2 | Expansion valve/throttling valves |

| CRF | Capital recovery factor |

| CEPCI | Chemical Engineering Plant Cost Index |

| Symbols | |

| T | Temperature [°C] |

| P | Pressure [bar] |

| h | Enthalpy [kJ kg−1] |

| s | Entropy [kJ kg−1] |

| Heat transfer rate of a system component [kW] | |

| Work done by a component in the system [kW] | |

| Net work done [kW] | |

| Specific exergy at state point: 1,2 … n [kJ kg−1] | |

| Rate of exergy at state point 1,2 ….n [kW] | |

| Exergy destruction [kW] | |

| Isentropic efficiency [%] | |

| ψ | Second law efficiency [%] |

| Δ | Difference |

| ξ | Effectiveness of ARS heat exchanger |

| Heat transfer coefficient of a system component [kW/m2.K] | |

| Area of heat transfer of a system component [m2] | |

| Capital cost of a system component [$] | |

| Capital cost rate of a system component [$/h] | |

| ir | Interest rate |

| n | Time of operation [years] |

| Operation and maintenance factor | |

| τ | Annual operation time of the system system [h] |

| csystem | Average cost per unit energy [$/GJ] |

| Subscripts | |

| 1, 2, 3,4 …. | State points |

| in | Inlet |

| out | Outlet |

| 0 | Dead state |

| VG | Vapor generator |

| sup | Superheater |

| gen | Generator |

| cond | Condenser |

| evp | Evaporator |

| abs | Absorber |

| tur | Turbine |

| CF | Counter-flow |

| PF | Parallel-flow |

| w | Water |

| wof | Working fluid |

| ph | Physical exergy |

| ch | Chemical exergy |

| ki | Kinetic exergy |

| po | Potential exergy |

| s | isentropic |

1. Introduction

Thermal energy loss, or waste heat, is a major issue in industries, especially those which involves complex systems made up of a large number of components [1]. Approximately 60 % of the waste heat produced by these systems is reportedly emitted back into the atmosphere [2], contributing significantly to global warming. Therefore, waste heat recovery (WHR) is seen as one potential solution for enhancing system efficiency and reducing its environmental impact [3]. WHR systems utilizes the high temperature of exhaust gases of primary systems to produce useful work [4]. The most common heat sources for waste heat are internal combustion engines, gas turbines, diesel engines and industrial processes such as cement-production [5]. Developing a good WHR system, works in tandem with developing a more efficient thermodynamic system with a strong emphasis on sustainability.

1.1. Organic Rankine cycle (ORC)

Over the past 20 years, the market for Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) plants has experienced a remarkable expansion, especially in developing WHR systems. By the end of 2016, there were about 563 powerplants with ORCs installed, generating an additional power of 2.75 GWe [6]. Due to its capacity for heat recovery from a wide range of temperatures (especially low heat), compactness, simple structure, high efficiency, low pollution, and minimal erosion, the ORC's development came with numerous potential application [2,4]. Low-temperature waste heat recovery from solar [6], geothermal [7] etc. have been used in ORC systems to produce energy. ORC systems can also be connected to various energy systems like power plants [8], biogas plants [9], energy storage systems [10] and even absorption refrigeration systems [11] because of its adaptability and reliable operation. Numerous studies have also found links between the ORC and high- and moderate-temperature heat sources (450 °C and above) [12]. The configuration of ORC plants can also be altered, and a variety of working fluids can be used in them. To enhance power output and achieve high efficiency, both factors must be optimized [13]. Due to the already-low operating temperatures of the ORC, cascading it with different cycles proves to be challenging, and only a handful of working fluids such as carbon dioxide (CO2) [4] or liquid nitrogen [2] are suitable.

1.2. Transcritical CO2 cycle (TCO2) and LNG cold utilization

The high performance of a supercritical or transcritical CO2 cycle, especially on electricity generation from a low-temperature heat source are recognized [14]. Furthermore, CO2 is easy to obtain, non-toxic, non-flammable, non-explosive, and does not produce any detrimental environmental effects when utilized in a cycle [14,15]. However, the condensation of CO2 is a significant issue in practice due to its low critical temperature. For low-temperature heat sources (specifically below 400 °C), ORC proves to be superior to CO2-cycles when water is available as a cooling medium [13]. However, if a working fluid with a lower operating temperature than water is used in the heat sink, CO2 power cycles would offer a relatively better performance for low-temperature heat recovery. To that end, a low temperature heat sink medium such as liquified natural gas (LNG) offers itself as a potential option.

LNG, in its liquid form, possesses a substantial amount of utilizable cold energy. The cold energy in one tonne of LNG can produce roughly 240 kWh of electricity, if fully utilized [16]. Re-gasification is also required before LNG can be used for its conventional use in heating or cooking. Typically, sea water is used to heat up the cold LNG liquid. However, in addition to energy consumption to run the sea water pump, the process may also harm the marine habitat. Hence, this process leads to substantial amounts of the cold exergy in the liquified LNG being wasted [17]. LNG has both thermal and mechanical energy. The expansion process is the only technique employed to utilize its mechanical exergy. The thermal side, however, offers additional choices, especially as a heat sink. Designing a power plant with nearly no emissions can also help with CO2 capture [18].

It is generally known that the exergy efficiency of a heat exchanger suffers because of the substantial difference in the average temperatures between the hot and cold streams [5]. This issue arises because the LNG cycle operates at a relatively lower temperature than most working fluid's condensation temperature. To address this, many waste heat recovery systems utilizing low-temperature heat sources such as geothermal energy [19], solar energy [20] etc have been proposed that use a TCO2 cycle with an LNG stream heat sink. However, such single-stage cycles still shared the common problem of having a large difference in temperature between the hot and cold side of the heat exchanger that was coupled with the LNG stream [21]. Hence, it can be concluded that, the usage of LNG as a heat sink for an efficient power cycle like a TCO2 cycle should be combined with a cycle that allows the CO2 to operate in the transcritical region, while also providing a facile development of power and LNG gas without having a significant difference in operating temperatures, i.e an ORC. LNG for a combined cycle, such as ORC and TCO2 [22], shows great promise in providing effective waste heat utilization from a medium temperature heat source of 250 °C.

1.3. Features of absorption refrigeration system (ARS)

An ongoing field of study in refrigeration focuses on developing systems that does not wholly depend on electricity to regulate pressure such as the extensively studied vapor compression refrigeration (VCR) system [[23], [24], [25]]. An absorption refrigeration system (ARS) is a potential solution as it is a type of cooling appliance that draws its cooling power from an external heat source, such as waste heat [26], solar [27], geothermal [28], and biomass [29] in addition to electricity, making it a thermally active system. By absorbing a fluid vapor (e.g., ammonia, lithium bromide) into another carrier liquid (e.g., water), then pumping this solution to a high-pressure cycle with a basic pump and, finally producing vapours of the mixed solution by absorbing heat from the environment, produces the desired refrigeration effect. The development of ARS is mainly focused towards improving its refrigeration effect [11,30,31]. One way to improve the refrigeration effect is the integrating of the ARS with a traditional VCR system [32,33]. Different modifications of the ARS can also have an effect in its performance. For example, changing a double-effect ARS from a series to parallel arrangement can improve the coefficient of performance (COP) from 1.39 to 1.44 [34].

ARS technology has shown great potential in using waste heat as its energy source. An ARS system integrated with a bulk carrier engine to recover heat and produce refrigeration can, theoretically, reduce electricity consumed for air-conditioning by about 70 % and 61 % in ISO and tropical conditions respectively. This is estimated to save about 95 tonnes of fuel annually [35]. Furthermore, the integration of ARS utilizing waste heat to an existing plant, such as an LNG producing plant for sub-cooling of the LNG, can lead to a COP improvement of about 63 % [36]. Experimental evaluation of ARS utilizing exhaust heat have shown satisfactory performance in between the temperature range of 150 °C–350 °C [37]. In conclusion, ARS technology is dependable, reasonably priced, and has great prospects as a sustainable refrigeration system. However, due to stand-alone ARS's providing inadequate cooling for high-level industrial use, the adoption of the ARS is still not feasible. Thereby, in order to improve the feasibility of the ARS, combing them with power-producing systems to make a combined cooling and power system (CCP) is a potential solution.

1.4. Combined cooling and power systems (CCPs)

A combined cooling, heating, and power (CCHP) system has many advantages compared to a conventional stand-alone system, such as: higher efficiency and power, along with reduced emission of CO2 gas [38,39]. A simpler derivation of the CCHP is the combined cooling and power (CCP) system, which have been extensively used for developing WHR systems.

For performance evaluation of a WHR system, one of the crucial assessment areas is the reduction of the waste heat outlet temperature, i.e., more effective utilization of the heat possessed by the waste stream before being exhausted out. To achieve that, recent studies have focused on the effect of integrating an ARS into power cycles, such as: combining supercritical CO2 with ORC or recompression Brayton cycle, or both [40,41]; TCO2 cycles [42], and ORCs with CO2 capturing storage (CCS) [43]. The combination of ARS and LNG subsystems for enhanced cooling was also explored [44]. CCP systems such as a Kalina cycle integrated with an ARS improved the COP from 0.256 to 0.360, and the second law efficiency from 18.5 % to 46.8 %, in addition to producing 493 kW of power [45]. The integration of supercritical CO2 (sCO2) cycle with ARS studied by Li et al. [46], also reported an improvement in COP. The prior references elucidate the immense potential of integrating an ARS with CCPs. However, a research gap is presented on the usage of ARS systems with efficient cascaded systems such as ORC-TCO2 systems with LNG energy utilization.

1.5. Problem statement and research scope

In this paper, an augmented combined cooling and power (CCP) waste heat recovery system is proposed. To better match the LNG cycle's low temperature, a transcritical carbon dioxide (TCO2) cycle is used. However, as the average temperature between the heat source and the operable temperature range of the TCO2 cycle is large, using the TCO2 cycle for power generation severely limits effective heat energy utilization, especially for moderate to high temperature heat sources. Consequently, the second law efficiency suffers significantly. This novel “Advanced cooling and power with LNG utilization (ACPLU)” system addresses this concern by making use of an ORC, that has been reported by previous studies to have a good thermal match with waste heat in between the medium to high temperature range, as the top cycle. To enhance the utilization of the waste heat and the applicability of the ACPLU, an absorption refrigeration system (ARS) is integrated into the combined system to provide refrigeration, while using the LNG cycle as its condenser. This dual functionality of the LNG cold energy can increase the temperature of the LNG working fluid, which can then be used to rotate a turbine to produce additional useful work output. The LNG can also be assumed to be re-gasified by this time and can be redistributed to systems that uses gaseous LNG, such as chemical plants for manufacturing paint, or fertilizers and even medicine. A comparative analysis of different working fluids in the ORC of the ACPLU will be performed to identify which working fluid provides the best performance. To study whether the issue about the high exergy destruction is mitigated by the ACPLU, second law efficiency and net work output, as well as on the exergy destruction performance will be assessed through a sensitivity analysis. Finally, a multi-objective optimization (MOO) using artificial neural network (ANN) and genetic algorithm (GA) will be conducted to find the optimum combination of parameters. A pharmaceutical manufacturing plant boiler usually exhausts heat at a moderate temperature (at about 260 °C). The ACPLU is expected to utilize this exhaust heat to produce enough refrigeration to be utilized to store blood samples, vaccines, and medical drugs, while also generating power. Additionally, the re-gasified LNG can be used for in-house heating and cooking.

2. System description

2.1. Cascaded power cycle with LNG cold energy utilization

The heat source is assumed to be the moderate temperature exhaust gases at around 300 °C [5]. An illustration of the cascaded power system is depicted in Fig. 1. A vapor generator absorbs heat from the exhaust stream through an economizer, a heat exchanger, and an evaporator. The vapor generator exchanges heat with the ORC working fluid (top cycle). The superheated working fluid then expands in the turbine to generate power (state 7 to 8). Subsequently, it passes through the high-pressure heat exchanger, HPHE, condensing into a saturated liquid phase for the top cycle (from state 3 to 4). The bottom cycle consists of the transcritical CO2 (TCO2) cycle absorbs heat from the HPHE, effectively turning into supercritical vapor (state 9). After generating power by expansion by the turbine (state 10), the working fluid goes through the low-pressure heat exchanger (LPHE). An LNG open cycle is pumped into the LPHE from ambient pressure (1.01 bar) to 70 bar at −162 °C (state 13 to 14). The LNG is responsible for absorbing the heat from the LPHE (state 10 to 11) while also heating up the LNG stream (state 14 to 15). To utilize the cold energy further, a chiller is added in the LNG stream to produce cold water (state 15 to 16). This dual-effect cold energy utilization of the LNG increases working fluid temperature. Finally, this vaporized LNG is forced through a turbine and generates extra power before being sent out in its re-gasified form for further use.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the ORC-TCO2-LNG power cycle.

2.2. Absorption refrigeration system (ARS)

Fig. 2 shows an illustration of a single-effect ARS. The generator is supplied with heat, which consists of a binary mixture of a fluid (LiBr) with water, water being the refrigerant. By absorbing heat, the lower boiling temperature fluid, i.e., water, vaporizes. The fluid is then condensed by expelling heat to the surrounding (state 2). The throttling valve (EV-1) expands the working fluid, which is then transferred into the evaporator (state 3). The throttling process is characterized by the pressure reduction of the working fluid, which also reduces its temperature. The heat from the surrounding is absorbed by the evaporator's low-temperature fluid, resulting in the desired cooling. In the absorber, the concentrated LiBr solution absorbs the refrigerant (at state 4). This absorption process causes a reduction in evaporator pressure, resulting in the temperature of the fluid to reduce further. Hence, even after the heat is absorbed by the surrounding, the low temperature of the cold fluid can be maintained. When the solution cannot continue this absorption process, the once-again-binary solution is pumped back into the generator. A significant exergy destruction can occur after the binary solution is pumped into the generator again (state 7) as the generator needs to heat the binary fluid again to evaporate out the water and start the absorption process again. Hence, a solution heat exchanger, SHX, is used (state 6 to 7) which can preheat the binary solution by transferring heat from the concentrated LiBr solution (state 8 to 9) before it enters the generator. An additional throttling valve (EV-2) is used to cool the concentrated LiBr solution after it transfer heat to the binary solution (state 9 to 10).

Fig. 2.

Single-effect absorption refrigeration system.

2.3. Proposed ACPLU system

The schematic diagram shown in Fig. 3 shows the proposed CCP system. The ACPLU system combines a cascaded power cycle consisting of a vapor generator, three turbines, three pumps, two heat exchangers, and a preheater with a single-effect ARS that consists of a generator, a condenser (ARSHE), an evaporator and absorber, one heat exchanger (SHX), a pump, and two throttling valves. The integration is implemented using a heat exchanger between the generator and the outlet air stream of the vapor generator, where the outlet temperature of the vapor generator and a predetermined pinch temperature determines the generator outlet temperature. The same principle is used to enhance the LNG cold energy utilization. This is facilitated by the implementation of another heat exchanger (i.e., ARSHE) that takes advantage of the colder LNG stream to act as the condenser for the ARS.

Fig. 3.

Proposed ACPLU system.

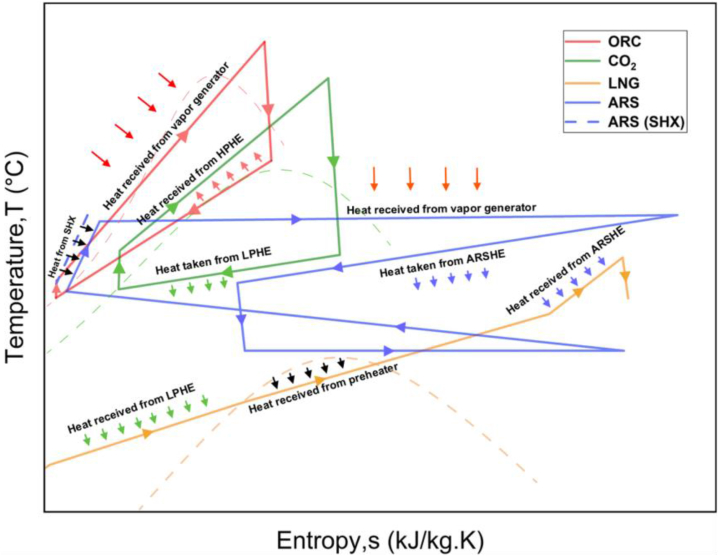

After going through the vapor generator, the waste exhaust stream goes through another heat exchanger connected to the generator of the ARS. The heat extracted by the generator/heat exchanger is used to separate the binary mixture of LiBr and water. As mentioned before, water in the ARS system then goes through another heat exchanger (ARSHE), where the condensation process is facilitated by the cold LNG stream (state 22 to 23). As the enthalpy required in the condensation process is provided by the system itself, the cooling capacity, i.e., the COP, is likely to increase. Furthermore, the LNG stream temperature increases, which improves the work output from the LNG turbine. A tentative temperature-entropy (T-s) diagram for the proposed ACPLU system is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Temperature-entropy (T-s) diagram for the proposed ACPLU system.

3. Selection of working fluids

A comparison analysis is conducted by choosing organic fluids to be used in the ORC of the ACPLU system. In this paper, pentane is selected as the working fluid for the ORC [5] and LiBr-water solution is used as the working fluid for the refrigeration cycle for the parametric analysis.

The performance of an ARS is also significantly influenced by the chemical and thermodynamic characteristics of its working fluid [47]. The combination of the absorbent and refrigerant must have a predetermined level of miscibility when operating in the temperature range in order to achieve optimal results [48]. Chemical inertness, non-explosiveness and non-toxicity is also favoured. Moreover, the evaporator temperature cannot be below the freezing point of water at a given pressure [49]. Some desirable characteristics of the ARS working fluid are: [50].

-

⁃

The difference between the absorbent/refrigerant boiling temperatures should be high at a given pressure.

⁃A refrigerant with a high heat of vaporization.

⁃High LiBr concentration in the solution so that circulation ratio per unit of cooling capacity is low between the generator and the absorber.

As of today, 200 absorbent and 40 refrigerant compounds are available [51]. The most prevalent combinations used in ARSs are ammonia-water (NH3–H2O) and lithium bromide-water (LiBr–H2O). NH3–H2O solution have had widespread applications in both heating and cooling. Ammonia-water has a large operating temperature range and boasts a high latent heat of vaporization that further facilitates effective system performance. Furthermore, ammonia's low specific volume and ability to operate at a high range of pressure means the ARS can be made more compact when using NH3–H2O.

However, NH3–H2O is less stable and usually requires a rectifier to separate water vapor from ammonia. This leads to increased heat loss, reduced efficiency, and introduces complexity to the cycle [52]. A significant drawback of using NH3–H2O solution is its inherent cytotoxicity. It's high working pressure range and corrosiveness, also limits the system's choice of material to corrosive resistant materials like carbon steel [53]. Conversely, the LiBr solution is more robust and cost-effective. The difference in boiling temperatures between LiBr and H2O is higher, hence a rectifier is not necessary. However, the danger of crystallization of the solution limits it to operate in a narrow concentration range with an absorber temperature lower than approximately 40 °C [54].

4. Research methodology

4.1. Assumptions

The following assumptions taken from previous studies are used for the modelling of the ACPLU [5,55,56].

-

⁃

Steady state conditions are maintained in all the systems.

-

⁃

The waste stream that acts as the heat source is an ideal gas.

-

⁃

Supercritical condition is assumed in the turbine inlet of the TCO2 cycle, while superheated condition is assumed for the turbine inlet of the ORC.

-

⁃

HPHE, LPHE, ARSHE outlet is always saturated liquid.

-

⁃

The working fluid is in saturated liquid phase at the evaporator outlet.

-

⁃

The working fluid is a weak solution at absorber outlet, at absorber temperature.

-

⁃

The working fluid is a strong solution at generator outlet.

-

⁃

Hydrostatic pressure and heat losses from the generator are at negligible levels.

-

⁃

The exhaust air came out of the vapor generator at 100 °C and at 60 °C out of the generator.

-

⁃

The isentropic efficiency for pumps and turbines is fixed at a constant value due to the inherent challenges associated with turbomachine modelling.

-

⁃

The working fluid of the LNG stream is assumed to be methane.

-

⁃

Working fluid through piping and condenser does not cause any pressure drop.

-

⁃

Environmental condition is taken at 25 °C and 1 atm.

-

⁃

The standard reference state for the International Institute of Refrigeration (IIR) is used ORC and LNG working fluids, and Normal Boiling Point (NBP) reference state was used for the TCO2 cycle.

Steady state conditions allow for predictable and repeatable system performance. This is crucial for control, optimization, and safety in various engineering applications. Assuming steady-state conditions simplifies mathematical modelling and analysis. In many engineering applications, gases are approximated as ideal and pressure drop is neglected to streamline design and analysis. Moreover, assuming that the fluid comes out as a saturated liquid out of every condenser and the evaporator, the simplicity of the model is further enhanced. The assumption for taking a weak solution out of the evaporator outlet aligns with the thermodynamic equilibrium conditions. At the outlet of the absorber, the solution reaches a state where it has absorbed as much refrigerant vapor as it can at the given absorber temperature and pressure, forming a weak solution. Likewise, at the ARS generator outlet, the solution reaches a thermodynamic equilibrium where most of the refrigerant has been vaporized due to the applied heat, therefore producing a strong solution.

4.2. Thermodynamic energy equations

The mass, energy and exergy balance equations, along with the aforementioned assumptions, can be utilized to find the state properties of each of the components. The general form of the equations are as follows.

4.2.1. Integrated ORC-TCO2-LNG system

The equations for the power cycle are taken from previous studies on cascaded ORC-TCO2-LNG power cycles [5]. The temperature in the top cycle is considered superheated, so the temperature of the turbine inlet is given Equation (1):

| (1) |

The steady flow energy balance formula shown in Equation (2) can be used to calculate the total energy throughout the system [57].

| (2) |

Where is the mass flow rate, and h is the enthalpy of the stream at a specific state. and is the energy associated with heat and work respectively. As the potential and kinetic energy of the flow is relatively negligible, the formula can be simplified as follows:

| (3) |

Equation (4) is used to calculate power generation in the turbine:

| (4) |

where hout can be found using the turbine efficiency formula shown in Equation (5):

| (5) |

Power consumed by pump is calculated using Equation (6):

| (6) |

is negative as energy is consumed. The efficiency of the pump is given by Equation (7), which is used to find the outlet state properties of the pump, hout

| (7) |

The heat exchanger HPHE, LPHE, and ARSHE acts as the condenser for the higher temperature stream and as the boiler for the lower temperature stream (i.e., HPHE acts as the ORC condenser and as the boiler for the TCO2 cycle). The temperature of the cold side outlet of the counter flow and parallel flow heat exchangers that are acting as condensers is given by Equation (8a) and Equation (8b) respectively:

| (8a) |

| (8b) |

The energy balance equation of the heat exchangers in Equation (9) is used to find the mass flow rate, given that enthalpy of the states is known.

| (9) |

The mass flow rate in the preheater is found using the following energy balance formula in Equation (10):

| (10) |

4.2.2. Refrigeration cycle

The waste heat exhaust, after passing through the power cycle, can be used to thermally drive the ARS. The heat from the waste gas can be correlated with the heat utilized by the generator of the ARS using Equation (11):

| (11) |

The components of the system can be assumed as a control volume. The continuity principle can be utilized to develop the mass balance equation:

| (12) |

The solution concentration balance is taken from a previous study on modified ARS [55]:

| (13) |

Heat absorbed or rejected by the components of the absorption refrigeration cycle is given by

| (14) |

As heat exchanger effectiveness has a significant effect on the cooling effect of the ARS, it was included during the modelling of the refrigeration cycle. The effectiveness can be explained as the ratio between the difference in temperature inlet and outlet on the hot side of the solution heat exchanger SHX and the absolute temperature difference of the working fluids that goes into the SHX. Equation (15) shows the effectiveness for the ARS preheater:

| (15) |

4.2.3. Overall proposed CCP system

Finally, the net power output of the ACPLU system can be computed by finding the sum total of the power produced and consumed in the ORC, TCO2, LNG turbine and ORC, TCO2, LNG, and ARS pump, respectively, as shown in.

| (16) |

The following obtains the COP for refrigeration of the ACPLU:

| (17) |

But as the work done by the ARS pump is negligible compared to the power input by the generator, the equation is simplified as follows:

| (18) |

4.3. Exergy analysis

The maximum net work output from a system from a specific state to a reference state (usually the state of its surrounding) is called exergy. The exergy of a control volume is computed using the following equation:

| (19) |

represents the exergy associated with heat transfer:

| (20) |

represents the exergy associated with work:

| (21) |

Exergy transfer through mass transfer is found using Equation (22):

| (22) |

Where e is the specific exergy. The specific exergy can be divided into four subcategories: kinetic, potential, physical and chemical exergy as shown below:

| (23) |

Due to negligible changes in the kinetic and potential exergy, the first two terms can be assumed negligible. Moreover, as the proposed system does not involve any chemical reactions, the chemical exergy can also be deemed negligible. Hence, the exergy transfer equation is simplified and expanded to Equation (24):

| (24) |

The exergy destruction is the exergy used up by a component of a system. The general exergy destruction equation of each component is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Exergy destruction of each component in the system.

| Component | Exergy destruction |

|---|---|

| Vapor generator | |

| Turbine | |

| Pump | |

| Condenser/Heat exchanger; Generator; Evaporator; Absorber | |

| Preheater | = |

For the ACPLU system, the net rate of the exergy input is the summation of the exergy input from the heat source and the LNG stream, as shown in Equation (25). This is primarily due to the LNG stream having an abundance of chemical exergy that can be used be utilized in some other process [5].

| (25) |

Where the rate of exergy from is heat source in calculated using Equation (26):

| (26) |

The exergy input from the LNG stream, which is the exergy rate between the inlet and outlet of the LNG system, is calculated using Equation (27):

| (27) |

The net rate of useful exergy by the ACPLU system can also be divided into three categories: (a) The net work done by the proposed system; (b) The useful exergy developed in the form of cooling by the ARS evaporator and (c) The useful exergy in the form of chilled water in the water chiller. The useful exergy developed by the ARS evaporator and the preheater is given by Equation (28) and Equation (29) respectively:

| (28) |

| (29) |

Finally, second law efficiency of the combined cycle is calculated using Equation (30):

| (30) |

4.4. Thermo-economic analysis

After confirming the thermodynamic viability of the system, assessing its economic feasibility requires determining its implementation costs. Usually, the cost of implementing such a system consists of capital investments, and the operation and maintenance costs of the system over a period of time. The cost function equations of the thermodynamic components, Zcomponents, which is the capital needed to acquire the components according to the boundary conditions and performance (power output and/or input) is shown in Table 2. Here, the capital cost of the ARS components, excluding the solution pump, has been taken from the study undertaken by Wang et al. [41], using a reference heat transfer area of 100 m2 and the reference capital cost values given in Table 3. The basic cost data of the ARS component at 2000 is transferred to the 2018 cost data using the Chemical Engineering Plant Cost Index (CEPCI) values shown in Table 8.

Table 2.

| Components | Capital cost function of the system component |

|---|---|

| Vapor generator, HPHE, LPHE | |

| Preheater | |

| ORC/TCO2/LNG turbine | |

| ORC/TCO2/LNG/solution pump | |

| Generator, ARSHE, evaporator, absorber, SHX | |

| EV1, EV2 |

Table 3.

Reference capital cost of ARS components [41].

| Components | Capital cost ($) |

|---|---|

| Generator | 17,500 |

| ARSHE | 8000 |

| Evaporator | 16,000 |

| Absorber | 16,500 |

| SHX | 12,000 |

| EV1, EV2 | 300 |

The capital cost recovery function, CRF, is determined using Equation (33).

Table 8.

| Parameter | Formula | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference temperature (ambient) | °C | 25 | |

| Reference pressure (ambient) | bar | 1.01 | |

| Heat source inlet temperature | °C | 300 | |

| Heat source outlet temperature | °C | 100 | |

| Temperature of exhaust gas after passing ARS generator | T21 | °C | 60 |

| Heat source mass flow rate | kg/s | 120 | |

| ARS mass flow rate | kg/s | 1 | |

| ORC turbine inlet pressure | bar | 33 | |

| ORC condenser pressure | bar | 1.4653 | |

| TCO2 turbine inlet pressure | bar | 80.13 | |

| TCO2 condenser pressure | bar | 6 | |

| Isentropic efficiency of turbine | % | 85 | |

| Isentropic efficiency of pump | % | 75 | |

| LNG inlet temperature | °C | −161.7 | |

| LNG inlet pressure | bar | 1.01 | |

| LNG turbine outlet pressure | bar | 40 | |

| Superheated temperature | °C | 28.1 | |

| Pinch temperature in HPHE | °C | 8 | |

| Pinch temperature in LPHE | °C | 50 | |

| Pinch temperature in preheater | °C | 50 | |

| Pinch temperature in ARSHE | °C | 50 | |

| Pinch temperature in generator heat exchanger | °C | 25 | |

| Inlet temperature of preheater (hot side) | °C | 25 | |

| Outlet temperature of preheater (hot side) | °C | 5 | |

| Temperature at evaporator outlet | °C | −5 | |

| Temperature at absorber outlet | °C | 30 | |

| Temperature at condenser outlet | °C | 30 | |

| Effectiveness of solution heat exchanger | % | 90 | |

| Heat transfer coefficient of vapor generator, HPHE, LPHE | Uheat exchanger | kW/m2.K | 1.6 |

| Heat transfer coefficient of preheater | Upreheater | kW/m2.K | 2.0 |

| Heat transfer coefficient of generator | Ugen | kW/m2.K | 1.3 |

| Heat transfer coefficient of ARSHE | UARSHE | kW/m2.K | 0.5 |

| Heat transfer coefficient of evaporator | Uevp | kW/m2.K | 1.1 |

| Heat transfer coefficient of absorber | Uabs | kW/m2.K | 0.8 |

| Heat transfer coefficient of solution heat exchanger | USHX | kW/m2.K | 0.7 |

| Logarithmic mean temperature difference at generator | °C | 6.28 | |

| Logarithmic mean temperature difference at evaporator | °C | 13 | |

| Logarithmic mean temperature difference at absorber | °C | 10 | |

| Interest rate | ir | – | 0.12 |

| Operation and maintenance factor | – | 1.06 | |

| Lifetime of system | n | years | 20 |

| Annual operation time of the system | hours | 8000 |

Using the heat transfer coefficient values given in Table 8, the heat transfer area is found using Equation (31):

| (31) |

Where U is the heat transfer coefficient and , is the logarithmic mean temperature difference, given by Equation (32a) and Equation (32b) for counter flow and parallel flow heat exchangers respectively:

| (32a) |

| (32b) |

The logarithmic mean temperature difference of the generator, evaporator and absorber is given in Table 8.

| (33) |

where is the interest rate, and n is the years of operation of the ACPLU.

The cost rate for a component, , is given by Equation (34):

| (34) |

Where is the maintenance factor to consider the costs of operation and maintenance, and denotes the annual hours of operation of the ACPLU.

Finally, the average cost per unit of useful energy is calculated using Equation (35):

| (35) |

Where N is the total number of components.

5. Mathematical modelling

The components are computed as a control volume, using the assumptions given in 4.1. Assumptions. The temperature, mass, energy balance equations for the standalone power cycle and ARS are given in Table 4, Table 5 respectively. Table 6 represents the equations for temperature, mass, and energy balance for the ACPLU with state points corresponding to Fig. 3. Additionally, the equations for exergy destruction rate for the ACPLU system are shown in Table 7.

Table 4.

Governing mass, temperature, and energy balance equations for the cascaded power cycle.

| Component | Mass balance | Temperature balance | Energy balance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vapor generator |

|

||

| ORC turbine | - | ||

| HPHE |

|

||

| ORC pump | - | ||

| CO2 turbine | - | ||

| LPHE |

|

||

| CO2 pump | - | ||

| LNG pump | - | ||

| Preheater |

|

||

| LNG turbine | - |

*The state points in this table corresponds to the state points of the system depicted in Fig. 1.

Table 5.

Governing mass, temperature, and energy balance equations for ARS system.

| Component | Mass balance | Temperature balance | Energy balance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generator |

|

|

|

| Condenser | |||

| EV-1 | - | ||

| Evaporator |

|

||

| Absorber | - | ||

| SHX |

|

- | |

| EV-2 | |||

| Solution pump |

|

*The state points correspond to the state points for the system depicted in Fig. 2.

Table 6.

Governing mass, temperature, and energy balance equations for the proposed CCP system.

| Component | Mass balance | Temperature balance | Energy balance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vapor generator |

|

||

| ORC turbine | - | ||

| HPHE |

|

||

| ORC pump | - | ||

| CO2 turbine | - | ||

| LPHE |

|

- | |

| CO2 pump | - | ||

| LNG pump | - | ||

| Preheater |

|

||

| ARSHE (cold side) | - | ||

| LNG turbine | - | ||

| Generator |

|

|

|

| ARSHE (hot side) | |||

| EV-1 | - | ||

| Evaporator | |||

| Absorber | |||

| SHX |

|

- | |

| EV-2 | |||

| Solution pump |

|

* The state points correspond to the state points for the system depicted in Fig. 3.

Table 7.

Exergy destruction equations for the proposed CCP system.

| Component | Exergy destruction |

|---|---|

| Vapor generator | |

| ORC turbine | |

| HPHE | |

| ORC pump | |

| CO2 turbine | |

| LPHE | |

| CO2 pump | |

| LNG pump | |

| Preheater | |

| ARSHE | |

| LNG turbine | |

| Generator | |

| EV-1 | |

| Evaporator | |

| Absorber | |

| SHX | |

| EV-2 | |

| Solution pump |

* The state points correspond to the state points for the system depicted in Fig. 3.

The mathematical modelling chronology is followed in the way shown in Fig. 5. Thermodynamic properties of all the working fluids are taken from the EES library and the program is simulated using the operating parameters depicted in Table 8. The operating parameters are taken after careful deliberations of the operating parameters used in previous studies [5,19,41,55,58,59]. The difference in operating temperature range between the LPHE, streams is kept to an absolute minimum and the supercritical condition of the LPHE outlet means that effectiveness of the heat exchanger is high [5]. The range of and the assumed value of is taken in a way that crystallization of the working fluid does not occur [55]. The evaporator temperature, Tevp is assumed to be 5 °C. Even though the evaporator temperature is below the melting temperature of water, it can still be assumed that water stays in liquid phase. This is because, as the water is moving at a very low mass flow rate, the water can be assumed to be a bulk liquid. Bulk water is reported to freeze with temperatures below −30 °C [60] which can only be increased to the range of −8 °C to −15 °C using ice-binding surfaces. Furthermore, water in small spaces composed of minerals (i.e., pipes), is observed to freeze below 0 °C [61]. Even so, freezing of water may occur if an evaporator temperature around is taken. Nevertheless, to prevent the possibility for the water to even freeze partially, a minimum evaporator temperature of −5 °C is taken. By addressing these assumptions and their impacts, we tried to provide a clearer understanding of the potential limitations of our study. We acknowledge that these assumptions introduce certain constraints and potential deviations which can be validated with sensitivity analysis in future to refine the model and ensure its robustness in real-world applications.

Fig. 5.

Framework for mathematical modelling of the proposed CCP system.

6. Multi-objective optimization (MOO)

Finding the proper combination of operating parameters is pertinent with overall system performance. Multi-objective optimization (MOO) can help in finding the suitable combination of operating parameters that favors one or multiple aspects of system performance, i.e., net work output or 2nd law efficiency, or both. In this paper, MOO is conducted using the steps shown in Fig. 6. The different sections used in the MOO are discussed below.

Fig. 6.

Mult-objective optimization flow chart.

6.1. Artificial neural network (ANN) model

Artificial neural networks (ANNs) are used to form a parametric model, that is regulated by trainable parameters, by using a large set of trainable data. This parametric model can be used to predict the values of unknown parameters, in between and even outside the dataset range, classify patterns, categorize, as well as functionalize a set of data [62]. ANNs are based on the nerve call or neuron (hence, the name Artificial Neural Network). Just like the biological nerve cell, a neuron of the ANN gets a multitude of inputs from other neurons, and based on the weighted total of the inputs, the output is either 0 or 1 [63]. The back-propagation learning algorithm in MATLAB 2021b (MathWorks, Massachusetts, United States) was used to acquire the objective function. A visual depiction of an ANN with back-propagation learning is shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Illustration of an ANN model with back-propagation.

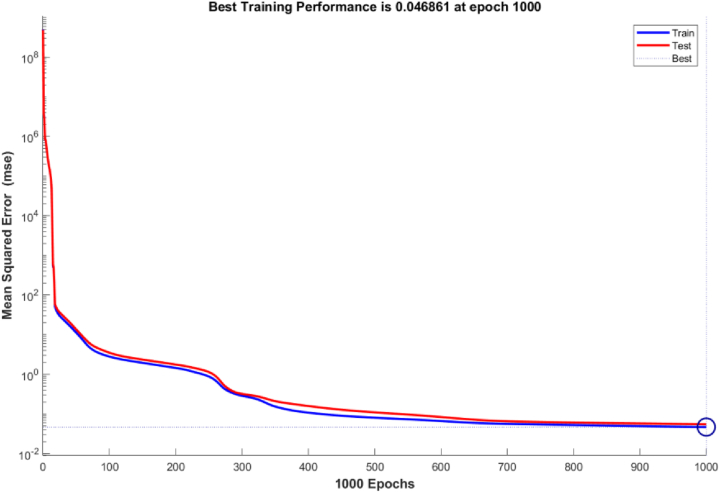

A dataset of 1188 observations with 3 inputs and 2 outputs is used. The data vision is set randomly, and the Bayesian regularization training algorithm is employed with a hidden layer size of 27. Among available training algorithms, Bayesian regularization training algorithm is chosen for better generalization of the data. The cost function: Mean Squared Error is calculated using Equation (36), to find the accuracy of the trained model [64].

| (36) |

Where , are the real and predicted value respectively and N is the number of data.

6.2. Multi-objective optimization genetic algorithm (GA)

The capability of solving incredibly complex and nonlinear problems with a relatively low computational power requirement makes the genetic algorithm (GA) a very useful tool [65]. Integrating ANN before finding the optimal solution with GA reduces the computation time substantially [66]. This makes the GA an ideal choice for the optimization of thermodynamic systems [64]. Using the upper and lower constraints of the input parameters shown in Table 9 and the GA parameters shown in Table 10, a multi-objective optimization was conducted using the gamultiobj solver in MATLAB 2021b (MathWorks, Massachusetts, United States) for the combinations of input parameters for (A) Maximum net work output; (B) Optimal point and (C) Maximum second law efficiency. The other GA parameters were kept in default settings.

Table 9.

Constraints used in the GA algorithm to conduct the MOO.

| Parameters | Unit | Lower limit | Upper limit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat source temperature | °C | 250 | 450 |

| CO2 condenser pressure | bar | 6 | 14 |

| ARSHE pinch | °C | 8 | 63 |

Table 10.

Operating parameters used in the GA.

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Population size | 200 |

| Crossover function | singlepointcrossover |

| Mutation function | mutationadaptfeasible |

7. Model validation

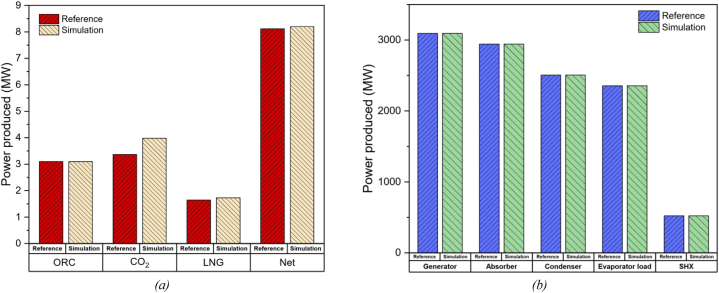

Due to the novelty of the ACPLU system, the mathematical model cannot be validated using existing systems in the literature. The different sub-systems, however, are validated against existing literature. The power cycle is modelled and validated against the previous study on the double cascade ORC-TCO2-LNG cycle proposed by Sadreddini et al. [5] and the refrigeration cycle is validated against the single-effect ARS proposed by Modi et al. [56], as shown in Fig. 8 and Table 11.

Fig. 8.

Bar charts comparing important parameters of reference values and calculated values of: (a) Power cycle and (b) Absorption refrigeration system.

Table 11.

Comparison of the calculated value and the reference values for the ORC-TCO2-LNG system and ARS.

| Cascaded ORC-TCO2-LNG cycle |

ARS |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Reference value [5] | Calculated value | Error (%) | Parameters | Reference value [56] | Calculated value | Error (%) |

| Power produced by ORC, (kW) | 3.10 | 3.098 | 0.07 | Generator input, (kW) | 3093 | 3094 | 0.03 |

| Power produced by TCO2 cycle, (kW) | 3.37 | 3.398 | 0.20 | Absorber heat rejected, (kW) | 2943 | 2943 | 0 |

| Power produced by LNG cycle, (kW) | 1.65 | 1.730 | 4.85 | Condenser heat rejected, (kW) | 2506 | 2506 | 0 |

| Power output, (kW) | 8.12 | 8.196 | 0.94 | Evaporator load, (kW) | 2355 | 2356 | 0.03 |

| Heat rejected by hot side of solution heat exchanger, (kW) | 522.6 | 522.9 | 0.57 | ||||

| COP | 0.7615 | 0.7615 | 0 | ||||

The results indicate that the parameters chosen for the validation of the ARS are highly consistent with the previous study, with a maximum error having a value of only 0.57 %. However, for the power cycle, the work output from the LNG cycle shows a significant error of 4.85 % between the reference and simulated model. This discrepancy in the LNG cycle's performance stems from the previous study only accounting for pressure drop within the LNG cycle. Even though our mathematical model accounts for that pressure drop, there are still differences in the state values for the LNG cycle. Another possible reason could be the differences in the library used. In our study, we have modelled the system with Engineering Equation Solver (EES), using the integrated fluid property library to find the state properties of the cycle, while the system for the reference study was developed in MATLAB and used fluid properties from the REFPROP library [67]. Here, the fluid property of methane (the chosen working fluid for the LNG cycle) differed between the two libraries. Nevertheless, aggregating the work output from each cycle to find the net work done, the error between the reference model and simulated model reduced to 0.94 %, concluding that the power cycle is also highly consistent.

8. Results and discussion

The computed state properties with pentane as the ORC working fluid are presented in Table 12. Using the assumed parameters, outlined in Table 8, a second law efficiency of 27.3 %, a net work output of 11.761 MW, and a COP of 0.7403 is achieved. Pentane is chosen as it shows one of the highest exergy efficiencies among the organic fluids that are tested for a comparative thermal analysis (shown in Table 12). Moreover, a sensitivity analysis is performed by varying several operating parameters to evaluate the effect on performance metrics such as: net work by each cycle, mass flow rates, COP, second law efficiency, exergy destruction as well as heat absorbed by the evaporator of the ARS. Finally, multi-objective optimization is conducted to identify combinations that yield the highest second law efficiency, highest net work done, and an optimal performance.

Table 12.

Computed results of combined power (Pentane-TCO2) and refrigeration cycle (LiBr–H2O).

| State | Temperature, T (°C) | Pressure, P (bar) | Enthalpy, h (kJ/K) | Entropy, s (kJ/kg-K) | Mass flow rate, (kg/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 25 | 1.013 | 577.1 | 7.521 | – |

| 1 | 300 | 1.013 | 579.2 | 7.525 | 120 |

| 2 | 100 | 1.013 | 374.1 | 7.085 | 120 |

| 3 | 47.2 | 1.465 | 27.2 | 0.086 | 37.91 |

| 4 | 49.12 | 33 | 34.2 | 0.092 | 37.91 |

| 5 | 195.2 | 33 | 490.7 | 1.234 | 37.91 |

| 6 | 195.2 | 33 | 548.1 | 1.357 | 37.91 |

| 7 | 223.3 | 33 | 683.3 | 1.639 | 37.91 |

| 8 | 141.6 | 1.465 | 565.1 | 1.690 | 37.91 |

| 9 | 133.6 | 80.13 | 562.2 | 2.114 | 43.67 |

| 10 | −32.68 | 6 | 450.2 | 2.200 | 43.67 |

| 11 | −53.12 | 6 | 86.8 | 0.552 | 43.67 |

| 12 | −49.81 | 80.13 | 95.2 | 0.561 | 43.67 |

| 13 | −161.7 | 1.013 | −0.8 | −0.007 | 77.73 |

| 14 | −158.4 | 70 | 20.9 | 0.041 | 77.73 |

| 15 | −103.1 | 70 | 225.1 | 1.484 | 77.73 |

| 16 | −25 | 70 | 691.8 | 3.759 | 77.73 |

| 17 | 5 | 1.013 | 21.1 | 0.076 | 432.9 |

| 18 | 25 | 1.013 | 104.9 | 0.367 | 432.9 |

| 19 | 25 | 70 | 840 | 4.305 | 77.73 |

| 20 | −11.22 | 40 | 779.5 | 4.346 | 77.73 |

| 21 | 60 | 1.013 | 333.6 | 6.970 | 120 |

| 22 | 75 | 0.0425 | 2640.0 | 8.713 | 1 |

| 23 | 30 | 0.0425 | 125.7 | 0.437 | 1 |

| 24 | −5 | 0.00402 | 125.7 | 0.492 | 1 |

| 25 | −5 | 0.00402 | 2491 | 9.314 | 1 |

| 26 | 30 | 0.00402 | 93.0 | 0.1643 | 35.56 |

| 27 | 30 | 0.0425 | 93.0 | 0.1643 | 35.56 |

| 28 | 71.3 | 0.0425 | 167.2 | 0.4111 | 35.56 |

| 29 | 75 | 0.0425 | 188.1 | 0.421 | 34.56 |

| 30 | 34.5 | 0.00431 | 111.7 | 0.1875 | 34.56 |

| 31 | 34.5 | 0.00431 | 111.7 | 0.1875 | 34.56 |

8.1. Comparison of working fluids in the ORC

The choice of the ORC working fluid significantly impacts the performance of the ACPLU system. For this study, 10 organic fluids were selected to compare their effects on overall system performance, as shown in Table 13, detailing their thermodynamic properties. Environmentally unsuitable refrigerant such as R11, R12, R113, R114, etc. was not chosen as part of the study. Table 14 shows the computed net work, first and second law efficiency of the ACPLU with different working fluid in the ORC. As the turbine inlet pressures of the ORC changes with its working fluid, a default value for each working fluid is chosen to be the nearest whole number below its corresponding critical pressure. It is observed that the degree of superheating provides a limiting factor to the maximum temperature allowed by the ORC. Hence, the optimum temperature of 28.1 °C is used for all the working fluids. Likewise, a pressure of 1.4653 bar is used as the default ORC condenser pressure. Pentane, R123, and cyclopentane are observed to operate with the default values. R123 shows a slightly better performance than pentane, and cyclopentane is observed to have the highest performance among the working fluids being studied, with a second law efficiency of 29.06 % and a net power output of 12,270 kW. This may be because, as the pressure drop during the expansion process for cyclopentane is the highest, and this is observed from the sensitivity analysis shown in the subsequent section of the paper, the work output from the expansion process was higher than the work input from pumping a fluid to a higher pressure. In that context, ethylbenzene is supposed to have the worst performance as it has the smallest pressure difference between the turbine and condenser. However, ethylene showed the lowest performance in terms of second law efficiency (13.99 %) and net work output (6693 kW). While ethylene has the 3rd smallest pressure difference, the main reason why ethylene showed an even worse performance is because it is a wet fluid (i.e., saturated vapor line has a negative slope in T-s diagram).

Table 13.

Fluid properties of carbon dioxide, methane and tested organic fluids [5,[68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74]].

| Working fluid | Tcrit (°C) | Pcrit (bar) | Type of fluid | Triple point (°C) | Maximum allowable temperature (°C) | Normal boiling point (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon dioxide | 30.98 | 73.77 | Wet | −56.41 | 1726.9 | −78.4 |

| Methane | −82.586 | 45.99 | Wet | −182.46 | 351.85 | −161.7 |

| Pentane | 196.55 | 33.7 | Dry | −129.68 | 326.85 | 36.06 |

| R123 | 183.68 | 36.72 | Dry | −107.15 | 326.85 | 27.82 |

| Isobutane | 134.66 | 32.29 | Dry | −159.42 | 301.85 | −11.75 |

| R24fa | 153.86 | 36.51 | Dry | −102.1 | 166.85 | 15.30 |

| Cyclopentane | 238.57 | 45.71 | Dry | −93.45 | 276.85 | 49.2 |

| Ethylene | 9.20 | 50.42 | Wet | −169.16 | 176.85 | −103.7 |

| Ethylbenzene | 343.97 | 36.22 | Dry | −94.95 | 426.85 | 136 |

| Toluene | 318.60 | 41.26 | Dry | −95.15 | 426.85 | 110.6 |

Table 14.

Computed performance parameters of the ACPLU with different working fluids.

| Working fluids | Net work (kW) | 1st law efficiency (%) | 2nd law efficiency (%) | Maximum temperature for superheating (°C) | ORC turbine inlet pressure range (bar) | ORC condenser pressure (bar) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pentane | 11761 | 39.91 | 27.3 | 28.1 | 33 | 1.4653 |

| R123 | 11807 | 40.06 | 27.45 | 28.1 | 36 | 1.4653 |

| Cyclopentane | 12270 | 41.63 | 29.06 | 28.1 | 45 | 1.4653 |

| Ethylbenzene | 10237 | 34.74 | 22.57 | 28.1 | 3 | 1.4653 |

| Ethylene | 6693 | 22.71 | 13.99 | 28.1 | 50 | 25 |

| R245fa | 11310 | 38.38 | 25.82 | 13.5 | 36 | 1.4653 |

| Isobutane | 11071 | 37.57 | 25.06 | 12.7 | 32 | 1.4653 |

| Toluene | 11801 | 27.43 | 28.68 | 28.1 | 10 | 0.6 |

A higher percentage of liquid during the expansion process can be detrimental to the turbine blades as it may cause cavitation. Therefore, the use of ethylene is not recommended unless a high degree of superheating can be provided. The degree of superheating is reduced for R245fa as the temperature at the turbine inlet exceeds its operable range. The same reduction is applied isobutane, where a temperature difference of 28.1 °C results in a negative exergy destruction rate in the component, HPHE, indicating system failure. For ethylene and toluene to be utilized as working fluids, the condenser pressure of ethylene must increase substantially, whereas it should slightly decrease for toluene. This is necessary for ethylene as the default condenser pressure lowers the temperature of carbon dioxide in the TCO2 cycle below its workable range. For toluene, reducing both the turbine inlet and condenser pressure ensures that there is no heat transfer from the ORC to the vapor generator at the default degree of superheating. Given that the model is validated based on the cascade ORC-TCO2-LNG cycle proposed by Sadreddini et al. [5], the proposed ACPLU aims to achieve two criteria: (1) A second law efficiency higher than 13.1 % and (2) A net work output above 8.12 MW. All working fluids, except for ethylene is observed to satisfy these criteria.

8.2. Sensitivity analysis

Utilizing the boundary conditions shown in Table 15, the effect of the various parameters on the mass flow rate, work output on each cycle, net work output and second law efficiency were examined. The boundary conditions for the power cycle were sourced from a previous study [5]. To ensure consistency with the previous study, pentane was chosen as the ORC working fluid. Given that the heat exchanger, ARSHE, and generator play crucial roles in integrating the power cycle with the ARS, greater emphasis must be given on validating this integration. Hence, a sensitivity analysis on the effect of pinch temperatures of ARSHE and the generator was conducted. Additionally, the influence of evaporator temperature on the overall performance of the ACPLU was bjstudied.

Table 15.

Boundary Conditions used for sensitivity analysis.

| Input Variable | Unit | Lower limit | Upper limit | Optimum value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat source temperature | °C | 250 | 450 | 300 |

| ΔTsup | °C | 0 | 50 | 28.1 |

| Turbine inlet pressure of ORC | bar | 16 | 33 | 33 |

| Condenser pressure of ORC | bar | 1 | 4 | 1.4653 |

| Turbine inlet pressure of TCO2 cycle | bar | 72 | 90 | 80.13 |

| Condenser pressure of TCO2 cycle | bar | 6 | 14 | 6 |

| Pinch (HPHE) | °C | 8 | 17 | 8 |

| Pinch (LPHE) | °C | 15 | 60 | 50 |

| Pinch (ARSHE) | °C | 8 | 63 | 50 |

| Pinch (Generator) | °C | 10 | 25 | 25 |

| Evaporator temperature | °C | −5 | 0 | −5 |

8.2.1. Effect of heat source temperature

Fig. 9(a) illustrates that an increase in heat source temperature results in more heat being absorbed by the vapor generator. Consequently, this increases the temperature of the working fluid, enabling higher mass flow rates in each cycle. This increase in mass flow rate means more superheated fluid enters the turbines, resulting in greater power generation.

Fig. 9.

Effect of heat source temperature on: (a) Mass flow rate and work done of each cycle; (b) Second law efficiency and net work done.

In Fig. 9(b), the net work of the system increases rapidly with higher heat source temperature. However, despite the anticipated trend of an increasing second law efficiency with rising heat source temperature, the second law efficiency for the ACPLU decreased exponentially. This is attributed, and later proved in the subsequent exergy analysis section, to the increasing average temperature between the inlet and outlet of the heat source, which increases the net rate of exergy destruction of the ACPLU system. While the total useful work output does increase with higher heat source temperature, it does so in a slower rate, resulting in an overall decrease in second law efficiency.

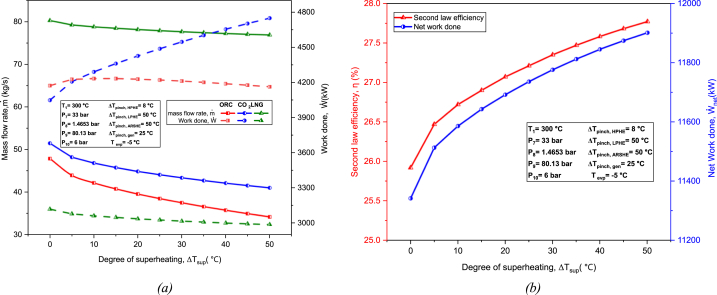

8.2.2. Effect of superheating

Degree of superheating describes the extent to which a fluid is superheated. Fig. 10(a) shows that, with an increase in the degree of superheating, the work output from the TCO2 cycle increases, but decreases for the LNG cycle. The work done for the ORC increases slightly till 5 °C and then decreases linearly, therefore showing an optimum value of 4233 kW at 5 °C. As both the ORC and LNG cycle exhibit a decrease in their power production rate with an increase in degree of superheating, the rate of increase in power produced by the TCO2 must offset it for an overall positive net work output. In the case of mass flow rates, all three cycles show a general decrease in mass flow rates.

Fig. 10.

Effect of degree of superheating on: (a) Mass flow rate and work done of each cycle; (b) Second law efficiency and net work.

Fig. 10(b) illustrates the net work output increases slightly with rising degree of superheating (5.4 % increase when degree of superheating is increased by 50 °C), were the net power output for the TCO2 cycle is the most sensitive to the degree of superheating. Simultaneously, the second law efficiency also increases significantly (from 25.92 % to 27.77 %). This may be attributed to the greater utilization of heat from the heat source. It can be concluded that increasing the degree of superheating will have little significance in improving the net work output of the proposed cycle but will contribute substantially in increasing the second law efficiency.

8.2.3. Effect of condenser pressure (lower pressure)

Variation in condenser pressure can alter the saturation temperature of the ORC's working fluid and impact the pressure ratio of the ORC turbine, resulting in a notable effect in performance. As shown in Fig. 11(a), increasing ORC condenser pressure leads to a significant decrease in the work done by the ORC, despite the slight rise in the ORC's mass flow rate. This is primarily attributed to the low-pressure ratio in the ORC turbine, which reduces its work output. However, both the TCO2 and LNG cycle has a slight increase in work output, which is evident by the rising mass flow rates in these cycles.

Fig. 11.

Effect of ORC condenser pressure: (a) Mass flow rate and work done of each cycle; (b) Second law efficiency and net work done.

Since the sensitivity of the ORC's work done to the ORC condenser pressure is more pronounced relative to the TCO2 and LNG cycle, the net work done by the ACPLU decreases with increase in ORC condenser pressure, as shown in Fig. 11(b). With the decrease in net work output, the second law efficiency also declines. This is evident because a lower pressure ratio leads to a lower expansion process. This observation leads to the conclusion that ORC condenser pressure significantly affects the work output of the ORC.

By examining the effect of CO2 condenser on mass flow rate and work done by each cycle, Fig. 12(a) reveals a decrease in work done for both the TCO2 and LNG cycle. For the LNG cycle, this decrease is accompanied by a corresponding drop in the mass flow rate. However, the mass flow rate of the TCO2 cycle increases slightly. Therefore, the reduction in work output for the TCO2 cycle may be attributed to a similar cause as the decrease in work output for the ORC, namely, the lower pressure ratio in the TCO2 cycle resulting from an increase in TCO2 cycle condenser pressure.

Fig. 12.

Effect of CO2 condenser pressure: (a) Mass flow rate and work done of each cycle; (b) Second law efficiency and net work done.

With respect to net work done, varying CO2 condenser pressure results in a trend similar to that of varying condenser pressure for ORC, as shown in Fig. 12(b). As the condenser pressure for TCO2 increases, the net work done decreases. In contrast to the decrease in second law efficiency observed with an increase in ORC condenser pressure, an increase in CO2 condenser pressure leads to a significant improvement in second law efficiency. This could be attributed to the decreased temperature difference between LPHE's hot and cold side. Compared to the proportional relationship between overall net work output and second law efficiency in the ORC, the inverse relationship in the TCO2 cycle elucidates that a smaller temperature difference between the hot and cold side of LPHE has a greater positive effect on second law efficiency than the negative effect from the reduced pressure ratio. This is further explored and explained in the subsequent sections.

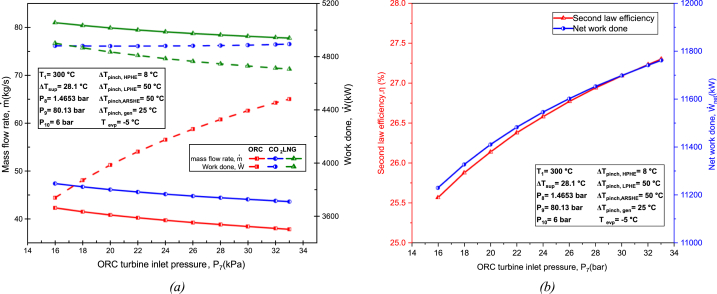

8.2.4. Effect of turbine inlet pressure (upper pressure)

Fig. 13(a) depicts that; mass flow rate decreases across all cycles. Altering ORC turbine inlet pressure increases the ORC work done significantly, while the LNG and TCO2 cycle experiences a slight decrease. Similar to the case of increasing condenser pressure, the increase in ORC work output is more sensitive compared to the decrease in TCO2 and LNG work output, with rising ORC turbine inlet pressure. The increase in ORC work output is likely a result of the higher-pressure ratio stemming from the higher turbine inlet pressure. Hence, the net work done increases significantly with rising ORC turbine inlet pressure, as illustrated in Fig. 13(b). Consequently, the second law efficiency also increases as more useful energy is utilized.

Fig. 13.

Effect of ORC turbine inlet pressure on: (a) Mass flow rate and work done of each cycle; (b) Second law efficiency and net work done.

For the TCO2 cycle to operate in transcritical conditions, the turbine inlet pressure must exceed the CO2 critical pressure (73.77 bar) while the condenser pressure must remain below it. As depicted in Fig. 14(a), the mass flow rate of the ORC remains constant with varying CO2 turbine inlet pressure, resulting in the ORC's constant work output. The mass flow rate, and consequently, the work output from the TCO2 increases very slightly as turbine inlet pressure increases. Conversely, there is a slight decrease in the mass flow rate with increasing CO2 turbine inlet pressure, resulting in a slight decreased work output in the LNG cycle. By combining all individual work outputs, it can be observed in Fig. 14(b), that the net work done increases slightly with the increase in the TCO2 turbine inlet pressure. Due to the development of the extra net work output, the second law efficiency also increases slightly.

Fig. 14.

Effect of CO2 turbine inlet pressure on: (a) Mass flow rate and work done of each cycle; (b) Second law efficiency and net work done.

8.2.5. Effect of pinch on system performance

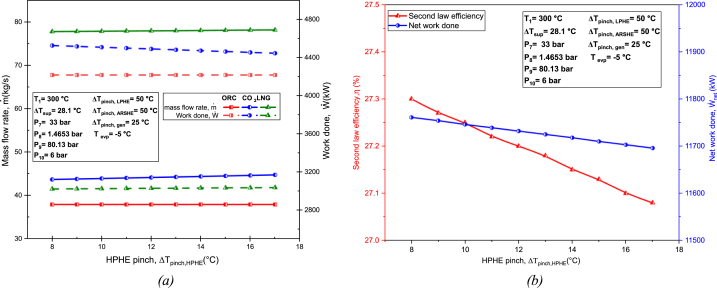

Fig. 15 illustrates the effect of the high-pressure heat exchanger, HPHE pinch temperature in system performance. The mass flow rate and work done by the ORC and LNG cycle remains relatively constant with increasing pinch temperature, as shown in Fig. 15(a). The mass flow rate of the TCO2 cycle increases slightly while the work output slightly decreases. This is attributed to the turbine's decreasing work output with increasing pinch temperature. In Fig. 15(b), at lower pinch temperatures, the system performs better. This may be due to less exergy destruction at lower pinch.

Fig. 15.

Effect of HPHE pinch temperature on: (a) Mass flow rate and work done of each cycle; (b) Second law efficiency and net work done.

In Fig. 16, variation in the low-pressure heat exchanger, LPHE, pinch temperature can significantly affect the ACPLU system performance. With increasing LPHE pinch temperatures, the LNG stream mass flow rate also increases. The increased mass flow rate elucidates the increased net work done. However, simultaneously, it leads to a decrease in second law efficiency. From this analysis, it can be concluded that a lower pinch temperature is recommended if the aim is to develop a more efficient CCP system utilizing LNG cold energy.

Fig. 16.

Effect of LPHE pinch temperature on system performance.

Cold energy from the LNG cycle is still available that can be used as a heat sink. Hence, integrating the ARSHE between the LNG and ARS cycle results in the general increase in LNG working fluid temperature (in state 19 of Fig. 3), resulting in a higher turbine work output. Shown in Fig. 17, the net work output and second law efficiency increases with increasing ARSHE pinch temperature. Similar to the heat exchanger, LPHE, increasing ARSHE pinch does not increase the overall exergy input rate while increasing the heat absorbed by the LNG stream, resulting in the increased system performance.

Fig. 17.

Effect of ARSHE pinch temperature on system performance.

8.2.6. Effect of ARS parameters on system performance

Studies have shown that variations in evaporator temperature, Tevp significantly affect the system performance of the ARS [75]. Since the generator pinch temperature, , is also a crucial operating parameter, a dual parametric analysis of the ACPLU system is conducted. As shown in Fig. 18(a), increasing generator and evaporator temperature improves the COP. This may be due to the higher heat absorption rate from the heat source. The generator pinch temperature does not have any effect on the second law efficiency and heat absorbed by the evaporator, while increasing evaporator temperature makes the second law efficiency suffer and increases the heat absorbed by the evaporator, as shown in Fig. 18(b) and (d) respectively. This may be due to the higher heat absorbed by the water from the concentrated LiBr solution inside the absorber. As shown in Fig. 18(c), temperature variations in the generator and evaporator does not have any effect on net work done by the ACPLU system, as the ARS is not responsible for power production and the power needed in the pumping process in the ARS is negligible.

Fig. 18.

Effect of generator pinch and evaporator temperature on: (a) COP (Coefficient of performance); (b) Second law efficiency; (c) Net work done; (d) Heat absorbed by evaporator.

8.3. Exergy analysis of the proposed ACPLU system

The flow of exergy rate of the ACPLU system and system components’ exergy destruction rate is depicted in Fig. 19. The negligible exergy destruction in the solution pump and expanders, is disregarded and put together as one outflow. The most significant exergy loss is shown to be in the LNG stream, with the maximum being in the preheater and LPHE. This may be due to most of the LNG stream being exhausted out. While the LNG can be used in its re-gasified state, which would facilitate its remaining exergy, it is not in our scope of study and remains a potential research gap to investigate. In the ARS system, it is expected that the solution heat exchanger (SHX) and the generator would be the chief contributors to the exergy destruction rate [76]. The relatively high exergy destruction in the generator (147.1 kW) and SHX (211,2 kW) in the ARS elucidates that. However, the highest exergy destruction rate in the ARS was observed to be in the evaporator (263.3 kW). This may be due to the environmental condition of the proposed system, which was assumed to be room temperature.

Fig. 19.

Flow diagram of exergy destruction for each component in the ACPLU system.

A comprehensive parametric analysis on the exergy destruction is shown from Fig. 20, Fig. 21, Fig. 22, Fig. 23, Fig. 24. As indicated in Fig. 20(a), the overall exergy destruction increases significantly with increase in pinch temperature. This can be elucidated further by understanding that the amount of heat wasted in the atmosphere is more when any of the system components transfers heat to the dead state, even if the net work done increases with rising heat source temperature. Furthermore, it is harder to maintain heat exchanger effectiveness at higher temperature, as shown by the increased exergy destruction in the preheater and LPHE. Due to the higher heat utilization of the waste heat source, the overall exergy destruction decreases with increasing degree of superheating, as shown in Fig. 20(b). Therefore, less heat is wasted to the surrounding. Evidently, the most significant decrease in exergy destruction of the component with increase in degree of superheating was in the vapor generator.

Fig. 20.

Effect of exergy destruction with: (a) Heat source temperature. (b) Degree of superheating.

Fig. 21.

Effect of exergy destruction with increase in: (a) ORC turbine inlet pressure (b) ORC condenser pressure. (c) CO2 turbine inlet pressure. (d) CO2 condenser pressure.

Fig. 22.

Effect of exergy destruction with decrease in: (a) Generator pinch temperature. (b) Evaporator temperature.

Fig. 23.

Effect of exergy destruction with increase in: (a) HPHE pinch temperature. (b) LPHE pinch temperature.

Fig. 24.

Effect of exergy destruction rate with increase in ARSHE pinch temperature.

Fig. 21(a) illustrates that, there is a slight decrease in exergy destruction with rising ORC turbine inlet pressure. At higher pressures, the utilization of heat from the heat source is enhanced [58]. This is elucidated by the significant decrease in the vapor generator exergy destruction rate. Conversely, Fig. 21(b), depicts an inverse trend with increasing ORC condenser pressure. While the vapor generator and ORC turbine exergy destruction rate decreases, it increases in all the other components of the power cycle, especially in the HPHE. This suggests that, increasing the ORC condenser pressure results in a lower pressure ratio in the cascaded cycle, resulting in more exergy being wasted, which may be due to the weakened heat transfer rate in the heat exchanger. Fig. 21(c) follows a similar trend to Fig. 21(a), albeit to a negligible extent. However, the increase in CO2 condenser pressure produces a significant reduction in overall exergy destruction, as illustrated in Fig. 21(d), due to the decrease in exergy destruction rate of both the HPHE and preheater. This may be attributed to the rise in LPHE hot side inlet temperature, which raises the LNG stream overall temperature, reducing the preheater's temperature difference between it's hot and cold side and, consequently, reducing its exergy destruction.

As depicted in Fig. 22(a) and (b), while increasing the generator temperature and evaporator reduces the generator's and absorber's exergy destruction rate as more heat is utilized from the waste heat source, the reduction is negligible relative to overall exergy destruction rate. Hence, the overall exergy destruction remains almost constant.

Although the higher HPHE pinch temperature makes the exergy destruction rate of the HPHE and LPHE increase due to the larger temperature difference between the heat exchanger's hot and cold side, the increase is very negligible relative to overall exergy destruction rate, as shown in Fig. 23(a). However, in Fig. 23(b), the rising LPHE pinch temperature increases the exergy destruction rate of the LPHE significantly. As the average temperature of the LNG stream is dependent on the pinch temperature of the LPHE, the temperature difference in the preheater increases significantly, resulting in the large rate of exergy destruction. In conclusion, the overall exergy destruction rate exhibits an almost linear increase with increasing pinch temperature Therefore, a lower pinch temperature in the LPHE is recommended.

Shown in Fig. 24, the exergy destruction of the ACPLU system increases slightly, reaching a maximum at 38 °C and then decreasing slightly, with increase in ARSHE pinch temperature. Beyond 38 °C, the rising exergy destruction rate of the evaporator, expansion valves and SHX is outweighed by destruction rate fall in the generator and absorber, resulting in a slightly decreasing overall exergy destruction.

8.4. Thermo-economic performance of the proposed ACPLU system

The economic performance of the ACPLU system, in terms of cost rate, is shown in Table 16. The cost rate of the ARS pump was negligible compared to the cost rate of the rest of the components, hence it was omitted. It can be observed that, among heat exchangers, the cost rate of the preheater is the highest, at 3.263 $/h followed by HPHE, SHX, LPHE, and ARSHE at 1.526 $/h, 1.308 $/h, 0.805 $/h, and 0.224 $/h respectively. The relatively high cost rate of the preheater may be attributed to the relatively low temperature difference between the hot and cold side. Implementing an additional preheater or putting the ARSHE before the preheater may mitigate this. Among all the components, after EV-1 and EV-2, that has no electrical load, the least cost is observed to be in ARSHE at 0.224 $/h. This can also outline that, the ARSHE should be put through the LNG stream before the preheater. This may incur additional costs, but may reduce the overall costs of the system. In average, the turbines show the highest cost rate, with the TCO2 turbine being the highest at 150.2 $/h. Moreover, the LNG pump is reported to have a relatively high cost rate, at 11.39 $/h, compared to the rest of the pumps. The average energy cost is 9.121 $/GJ. This can be reduced further by further optimization.

Table 16.

Capital cost rate of each component of the ACPLU system and total cost.

| Capital cost rate | Value ($/h) |

|---|---|

| 1.357 | |

| 1.526 | |

| 0.805 | |

| 3.263 | |

| 138.9 | |

| 150.2 | |

| 145.1 | |

| 3.126 | |

| 3.934 | |

| 11.39 | |

| 0.01 | |

| 0.01 | |

| 1.14 | |

| 0.224 | |

| 0.622 | |

| 1.057 | |

| 1.308 | |

| 463.8 | |

| Average cost per unit power |

Value ($/GJ) |

| cACPLU | 9.121 |

8.5. Optimization results and performance comparison with similar thermodynamic systems