Abstract

Depot-type drug delivery systems are designed to deliver drugs at an effective rate over an extended period. Minimizing initial “burst” can also be important, especially with drugs causing systemic toxicity. Both goals are challenging with small hydrophilic molecules. The delivery of molecules such as the ultrapotent local anesthetic tetrodotoxin (TTX) exemplifies both challenges. Toxicity can be mitigated by conjugating TTX to polymers with ester bonds, but the slow ester hydrolysis can result in subtherapeutic TTX release. Here, we developed a prodrug strategy, based on dynamic covalent chemistry utilizing a reversible reaction between the diol TTX and phenylboronic acids. These polymeric prodrugs exhibited TTX encapsulation efficiencies exceeding 90% and the resulting polymeric nanoparticles showed a range of TTX release rates. In vivo injection of the TTX polymeric prodrugs at the sciatic nerve reduced TTX systemic toxicity and produced nerve block lasting 9.7 ± 2.0 h, in comparison to 1.6 ± 0.6 h from free TTX. This approach could also be used to co-deliver the diol dexamethasone, which prolonged nerve block to 21.8 ± 5.1 h. This work emphasized the usefulness of dynamic covalent chemistry for depot-type drug delivery systems with slow and effective drug release kinetics.

Keywords: Drug delivery, Local anesthesia, Dynamic covalent chemistry, Tetrodotoxin, Polymeric prodrug

Introduction

In depot-type drug delivery, the goal is often to minimize the initial “burst” release.[1] Initial burst release can cause toxicity and—by wasting payload—limit duration of effect.[1,2] Conversely, excessively slow drug release can prevent therapeutic effect.[3] Another important goal is often to prolong the duration of release and therefore of therapeutic effect.[4,5] These goals are particularly important with payloads with the potential for systemic toxicity, and particularly challenging with small hydrophilic molecules.[6,7]

Injectable depot systems for prolonged local anesthesia have the potential to effectively treat perioperative and chronic pain.[8] Such systems could potentially obviate the need for opioids, with all their drawbacks including nausea, constipation and other systemic symptoms, but especially addiction, diversion, and overdose.[9] Site 1 sodium channel blockers (S1SCBs) such as tetrodotoxin (TTX) are useful in sustained release systems for pain due to their high potency as local anesthetics and minimal local toxicity.[10–12] However, burst release from systems containing S1SCBs can cause severe systemic toxicity, and their high hydrophilicity makes their release difficult to control.[13–16]

One approach to controlling burst release and extending duration of effect is to create polymeric prodrugs, where the drug molecules are covalently attached to a polymer carrier.[17–20] Conjugation of drugs through esterification can effectively slow release, but drug release by hydrolysis can be so slow that tissue levels are subtherapeutic.[21] For example, if TTX is conjugated to polymers by esterification,[14] release can be ineffective in vivo unless adjuvant compounds are added,[22,23] with their potential for local tissue toxicity.

Here we describe the use of dynamic covalent boronate ester bonds to create TTX polymeric prodrugs where the release of TTX is slow enough to enhance safety but fast enough to provide effective local anesthesia. Boronate ester bonds conjugate TTX’s 1,2 diols to polymers containing phenylboronic acid (PBA).[24] The formation of dynamic covalent boronate ester bonds uses gentle reaction conditions,[25–28] in contrast to the conditions for forming covalent ester bonds. The reversible nature of dynamic covalent boronate ester bonds makes it possible to design prodrugs with a range of hydrolysis rates.[29–35] We created polymers comprising 10 kDa poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) linked by cyano-methylbutanoate to chains of poly(3-acrylamidophenylboronic acid) with differing degrees of polymerization (DP, i.e., the number of PBA units, Scheme 1). The resulting polymers are abbreviated P-PBAn (P: PEG segments, n: the DP of the PBA segments). These polymers were conjugated to TTX, with high TTX encapsulation efficiency (EE%, >90%). PEG was selected so that the polymers would self-assemble into nanoparticles, with the hydrophobic PBA in the core and the hydrophilic PEG on the outside. Nanoparticles made from these materials demonstrated controlled TTX release kinetics and provided prolonged local anesthesia in vivo. We also demonstrated that this approach works with concurrent delivery of a second drug with diol groups, dexamethasone, with enhancement of therapeutic effect.

Scheme 1.

Chains of phenylboronic acid appended to a 10 kDa PEG are conjugated to TTX, then formed into nanoparticles. After injection at the sciatic nerve, the TTX diffuses away from the nanoparticle depot and blocks sodium channels, causing nerve block.

Results and Discussion

Boronic acids can conjugate with TTX through its 1,2 diols to form dynamic covalent boronate esters. After overnight co-incubation of TTX and 4-acetylphenylboronic acid (4-APBA) in methanol at room temperature (Figure 1a), the formation of 4-APBA/TTX complexes was demonstrated by signals at 447.1 (indicating complexation with 10B) and 448.1 (indicating complexation with 11B) on liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC–MS, Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Formation of PBA/TTX. (a). Schema of conjugation of TTX to 4-APBA. (b). LC–MS signal for 4-APBA/TTX. (c). Schema of conjugation of TTX to 4-triF-PBA. (d, e). Effects of the conjugation between TTX and 4-triF-PBA on the position and intensity of the fluorine signal from 4-triF-PBA or 4-triF-PBA/TTX on 19F NMR. (d) 19F spectra and (e) plot of the data in the dotted box in panel d. [4-triF-PBA] = 20 mM.

The conjugation between boronic acids and TTX was also confirmed by 19F NMR.[36] A 19F labeled phenylboronic acid, 4-(trifluoromethyl) phenylboronic acid (4-triF-PBA, 20 mM), was mixed with 0 to 1 mM TTX. Once the conjugation between 4-triF-PBA and TTX occurred, it produced a new 19F labeled compound (4-triF-PBA/TTX complex) with a new 19F signal (Figure 1c). After overnight co-incubation of TTX and 4-triF-PBA in a mixed solvent (methanol: deuterium water: water = 80:15:5, v/v/v), a new 19F signal at −63 ppm was observed (Figure 1d), confirming the formation of 4-triF-PBA/TTX complex. The intensity of this 19F signal increased linearly with TTX concentration, further proving that the new peak related to the formation of a 4-triF-PBA/TTX complex (Figure 1e, stacked 19F NMR spectra in Figure S1).

The efficacy of complexes of 4-ABPA and TTX was studied in vivo (Figure S2). Since they did not prolong block duration, they were not pursued further.

The syntheses of P-PBAn were performed and their abilities to self-assemble into nanoparticles were tested. In brief, P-PBAn with PBA DP of 25, 35, and 50 were synthesized by reversible addition fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization (Figure S3a).[37,38] The DP of the PBA segments and the molecular weights of the obtained P-PBAn were characterized by 1H NMR (Figure S3b; Table S1). Dropwise addition of P-PBAn in methanol into saline created spherical nanoparticles (termed NP-P-PBAn), as evidenced by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Figures 2a–c) and dynamic light scattering (DLS, Figure 2d). The diameters of NP–P-PBAn increased as the DP of the PBA segments increased (118, 146, 151 nm for DP 25, 35 and 50, all p<0.001, Table S2). All nanoparticles had zeta potentials around −20 mV (Table S2).

Figure 2.

Physicochemical characterizations of nanoparticles of P-PBA n. (a-c) Transmission electron microscopy images of NP–P-PBAn. DP for PBA segments is (a) 25, (b) 35 and (c) 50. Scale bar: 500 nm. (d). Diameters of NP–P-PBAn measured by dynamic light scattering. (e). Effect of reaction time between P-PBA50 and TTX at 37°C in methanol on the efficiency of TTX encapsulation in NP–P-PBA50. Data are means ± s.d., n = 3. (f). Effect of PBA DP on the efficiency of TTX encapsulation in NP–P-PBAn. Data are means ± s.d., n = 3. (g). Effect of PBA DP on the release kinetics of TTX from TTX@NP–P-PBAn, compared to free TTX. Data are means ± s.d., n = 4. p-Values are from unpaired two-tailed t test.

Since nanoparticle formulations can slow the release of drugs and thus can have longer durations of drug effects than free drugs,[2] we conjugated TTX to P-PBAn forming TTX polymeric prodrugs. These TTX polymeric prodrugs self-assembled into nanoparticles (TTX@NP–P-PBAn), serving as TTX sustained release depots (Scheme 1). In brief, TTX was conjugated to P-PBAn by co-incubating TTX and P-PBAn in methanol at 37°C (see Methods for the concentration details of TTX and P-PBAn). The resultant prodrugs in methanol were added dropwise into saline to form TTX@NP–P-PBAn. The unencapsulated (free) TTX was separated by ultracentrifugation and its concentration in the supernatant was quantified by LC–MS (standard curve in Figure S4a). The amount of TTX in TTX@NP–P-PBAn was calculated by subtracting the amount of free TTX from the amount of total feeding TTX. The amount of TTX in TTX@NP–P-PBAn was used to calculate the encapsulation efficiency (EE%) and the drug loading percentage (DL%) of TTX (See Methods). To determine the reaction time to conjugate TTX to P-PBAn, the TTX EE% was assessed during the reaction between TTX and P-PBA50 at selected time intervals. As the reaction time increased, the concentration of free TTX decreased and the EE% of TTX by PPBA50 reached a plateau within 3 h (EE% = 93.0% at 160 min compared with 93.8% at 16 h, p = 0.82; Figure 2e).

The EE% of TTX was calculated from the concentration of free TTX, so any TTX degradation could lower the free TTX concentration, resulting in falsely elevated calculated EE%. To exclude the effects of TTX degradation on the EE % of TTX, TTX was placed in methanol at 37°C. The concentration of free TTX did not change (97% of TTX at 16 h compared with 100% of TTX at the beginning, p = 0.29; Figure S5), demonstrating that there was no TTX degradation under the reaction conditions.

In all experiments below, the concentration of PBA was kept constant between P-PBAn with different DP. Specifically, 8.0 mg/mL of P-PBA25, 6.6 mg/mL of P-PBA35, and 5.0 mg/mL of P-PBA50 have the same concentration of PBA. Thus, for example, reference to P-PBA25 implies a concentration of 8.0 mg/mL. The concentration of TTX could be constant or varied depending on the experiments.

To investigate the effect of increasing DP of P-PBAn on TTX encapsulation, EE% and DL% of TTX were measured in all P-PBAn. P-PBAn were incubated in methanol with TTX. The EE% was >90% with all polymers irrespective of DP (Figure 2f). The DL% of TTX were 0.8%, 1.0% and 1.2% for P-PBAn with DP of 25, 35 and 50, respectively.

The zeta potentials of TTX@NP–P-PBAn after conjuga tion to TTX were all approximately −20 mV, indicating that the incorporation of TTX did not change their surface charge (Table S2). The size of TTX@NP−P-PBAn decreased after conjugation to TTX (from 117, 146, 151 nm to 78, 101, 127 nm for DP 25, 35, 50; p<0.001 for all comparisons; Figure S6; Table S2). The decreased nanoparticle size after the incorporation of TTX was possibly due to the hydrophilicity of TTX that destabilized the hydrophobic core of the nanoparticles.[37,39]

The ability of TTX@NP–P-PBAn to release TTX in a sustained manner was studied in vitro (Figure 2g; Figure S7a shows release over 45 h). 300 μL of saline containing free TTX or TTX@NP–P-PBAn with DP of 25, 35 and 50 were dialyzed against 14 mL saline at 37°C. The concentration of TTX in all these formulations was kept at 67 μg/mL. The amount of TTX released was quantified by ELISA at selected time intervals (standard curve in Figure S4b). With free TTX, 93% was released in 10 h. TTX@NP–P-PBA25 showed slower release (76% TTX release in the same period; p = 0.0052). Release further slowed as the DP of PBA segments increased, so that with TTX@NP–P-PBA50, only 25% TTX was released at 10 h (p<0.0001). The slower TTX release with higher PBA length may be due to the increasing hydrophobicity of the core and the larger nanoparticle size caused by higher hydrophobic PBA content, limiting access of water to hydrolyze the boronate ester and to TTX to allow its release.

The efficacy and safety of TTX@NP–P-PBAn were evaluated in a rat model of peripheral nerve block. TTX@NP–P-PBAn were injected at the left sciatic nerve in male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 4 or 6 per group; Scheme 1) with varying concentrations of TTX. Sensory nerve block was assessed with a modified hotplate test performed at predetermined intervals (see Methods). The thermal latency, which is the time in seconds a rat leaves its hindpaws on the hotplate, was measured in both hindpaws (2 s was baseline and 12 s was maximal block). Representative time courses of thermal latency are shown in Figure S8. Nerve block was considered to be successful if latency exceeded 7 s. Neurobehavioral deficits in the injected limb reflected nerve block, from which the duration of block was calculated. Deficits in the contralateral limb and the mortality reflected the effects of systemically distributed TTX (i.e., systemic toxicity).

Doses of free TTX were selected based on previous reports.[10] Injection of 4 μg free TTX resulted in nerve block in the injected limb lasting 1.6 ± 0.6 h (Figure 3a). This dose caused contralateral nerve block in all rats (Figure 3b), indicating systemic distribution. Injection of 5 μg of TTX caused 100% mortality (Figure 3c).

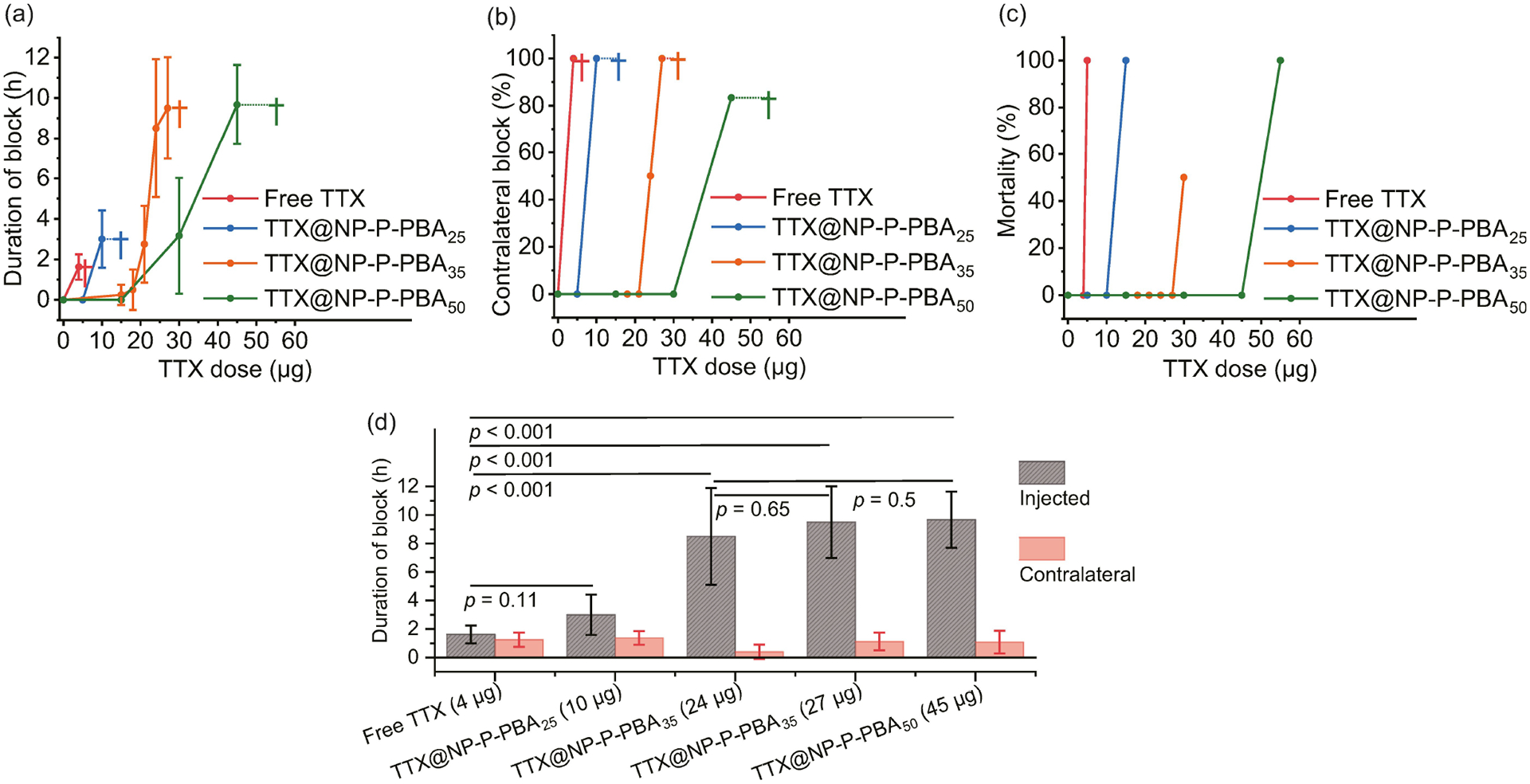

Figure 3.

Performance of TTX@NP–P-PBAn after injection at the sciatic nerve. (a) Duration of sensory nerve blockade in the injected leg from free TTX or TTX@NP–P-PBAn. (b) Frequency of block in the contralateral leg from free TTX or TTX@NP–P-PBAn. (c) Mortality from free TTX or TTX@NP–P-PBAn. (d) Summary of the maximum non-lethal durations of nerve block from free TTX or TTX@NP–P-PBAn. Daggers indicate animal death at specific TTX doses. Data are means ± SD; n = 4 for free TTX, TTX@NP–P-PBA25 and TTX@NP–P-PBA35; n = 6 for TTX@NP–P-PBA50. p-Values are from unpaired two-tailed t test.

With TTX@NP–P-PBAn, the slower release of TTX enabled the delivery of higher doses of TTX with reduced systemic toxicity. Consistent with the observed release kinetics, these effects correlated with increasing DP of the PBA. For example, TTX@NP–P-PBA25 containing 5 μg TTX, a lethal dose if given as free TTX, caused no block (Figure 3a), reflective of slowed release. With TTX@NP–P-PBA25 delivering 10 μg TTX, 3.0 ± 1.4 h of nerve block could be achieved without mortality. TTX@NP–P-PBA35 was able to deliver 24 μg of TTX (~5 times the lethal dose of free TTX), resulting in 8.5 ± 3.4 h of nerve block in the injected limb (Figure 3a). Contralateral block occurred in 50% of animals (Figure 3b), and there were no deaths (Figure 3c). The TTX dose could be increased to 27 μg in TTX@NP–P-PBA35 without morality, but the duration of block (9.5 ± 2.5 h, Figure 3a) did not increase statistically significantly (p = 0.65, Figure 3d). At this dose, contralateral block occurred in 100% of animals (Figure 3b). 30 μg of TTX in TTX@NP–P-PBA35 caused 50% mortality (Figure 3c).

Further increasing the DP of PBA to 50 (TTX@NP–P-PBA50) allowed the delivery of 45 μg TTX (9 times the lethal dose of free TTX), with contralateral block occurring in 83% of animals (Figure 3b) but no deaths (Figure 3c). Nerve block in the injected hindlimb lasted 9.7 ± 2.0 h (Figure 3a), which was not statistically significantly different from TTX@NP–P-PBA35 with 24 μg TTX (p = 0.5, Figure 3d). Increasing the TTX dose to 55 μg was uniformly fatal (Figure 3c).

In summary, delivery of TTX using TTX@NP–P-PBAn allowed for the delivery of greatly increased amounts of TTX without mortality, allowing prolongation of duration of block (Figure 3d).

Motor nerve block was assessed by a weight-bearing test[11] at the same time points where hotplate testing was done (see Methods). There were no statistically significant differences between the durations of sensory and motor nerve block (p>0.05 in all groups, Figure S9).

The duration of nerve block from sustained release systems containing TTX can be prolonged by co-delivery with glucocorticoid receptor agonists[11,40] such as dexamethasone (Dex). Dex has a 1,3 diol group, suggesting that it could also be conjugated by boron chemistry.[41] Dex itself does not cause nerve block; it only potentiates the effect of anesthetics.[42]

19F NMR studies were performed to confirm conjugation between boronic acid and the diol on Dex (Figure 4a). After overnight incubation of 0 to 1 mM 4-APBA with 1 mM Dex in deuterium methanol, the 19F signal derived from Dex (−164.4 ppm) decreased and a new 19F peak (−164.8 ppm) appeared, indicating the formation of 4-APBA/Dex complex (Figure 4b), which increased with increasing concentration of 4-APBA (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

Co-delivery of Dex and TTX using P-PBA 35. (a) Schema of the conjugation of Dex to 4-APBA. (b, c) Effects of the conjugation between Dex and 4-APBA on the fluorine signal position and intensity from Dex or 4-APBA/Dex on 19F NMR. (b) 19F spectra and (c) normalized 19F signal intensity of Dex and 4-APBA/Dex complex. 19F signal intensities were normalzied to the 19F signal from 1 mM Dex. The concentration of 4-APBA varied from 0 to 1 mM. (d) Cumulative release of Dex at 37°C from Dex@NP–P-PBA35 and TTX&Dex@NP–P-PBA35 (e) Effect of co-delivery of TTX and Dex on the duration of nerve block. Nerve blocks were from TTX@NP–P-PBA35 containing 27 μg TTX and TTX&Dex@NP–P-PBA35 containing 27 μg TTX and 60 μg Dex. Data are means ± SD; n = 4. p-Values are from unpaired two-tailed t test.

Dex was loaded into NP–P-PBAn (forming Dex@NP–P-PBAn). The process of Dex loading was similar to the process of TTX loading, as was the quantification of Dex in Dex@NP–P-PBAn (see Methods). Dex@NP–P-PBA35 had a Dex EE% of 74% and the DL% of Dex was 2.2%. Dex@NP–P-PBA35 showed less in vitro release at 10 h (39%) compared with free Dex (80%, p <0.001, Figure 4d; Figure S7b shows release over 45 h).

Nanoparticles loaded with TTX and Dex (TTX&Dex@NP–P-PBA35) had a lower EE% of Dex (61%) than did Dex@NP–P-PBA35 (74%, p<0.0001, Figure S10). The DL% of Dex in TTX&Dex@NP–P-PBA35 was 1.8%. Incorporation of TTX into Dex@NP–P-PBA35 accelerated Dex release (48% vs 39% at 10 h, p = 0.035, Figure 4d). The diminished Dex encapsulation and accelerated Dex release may be due to the enhanced hydrophilicity of the nanoparticle core after the incorporation of hydrophilic TTX.

TTX&Dex@NP–P-PBA35 also had a lower EE% of TTX (87%) than did TTX@NP–P-PBA35 (95%, p = 0.0014, Figure S11a). The DL% of TTX in TTX&Dex@NP–P-PBA35 was 1.1%. Incorporation of Dex into TTX@NP–P-PBA35 did not accelerate TTX release (69% vs 58% at 10 h, p = 0.38, Figure S11b).

Nerve block from TTX&Dex@NP–P-PBA35 containing 27 μg TTX and 60 μg Dex lasted 21.8–5.1 h, which was 2.3 times longer than the 9.5–2.5 h from TTX@NP–P-PBA35 containing 27 μg TTX (p = 0.005, Figure 4e). There was no difference between the duration of sensory and motor nerve block (21.8–5.1 h vs 27.8–5.7 h, p = 0.46). The results demonstrated the benefits of conjugating two drugs by dynamic covalent chemistry. It also demonstrated the benefit of increased loading at higher DPs, even though they might not have resulted in longer block with TTX alone. The longer release without toxicity could enable the effectiveness of potentiating drug combinations, as was seen with Dex.

As TTX causes essentially no local tissue toxicity,[43] the in vitro and in vivo toxicity of the PBA-based drug delivery carriers were investigated without TTX. The in vitro cytotoxicities of NP–P-PBA35 and Dex@NP–P-PBA35 were tested in the myoblast C2C12 cell line for potential myotoxicity and the pheochromocytoma PC12 cell line for potential neurotoxicity (see Methods).[44,45] Cell viability was >90% in all groups, and was not statistically significantly different from cells treated with PBS (Figure S12).

The sciatic nerve and surrounding muscle tissue were harvested on days 4 and 14, after local injection of PBS, NP–P-PBA35 and Dex@NP–P-PBA35. Day 4 is useful for studying acute inflammation and myotoxicity, and day 14 is for chronic inflammation and the recovery of myotoxicity. The collected tissues were processed for histology (n = 4 or 5; representative images in Figure 5; statistical results in Table 1). The nanoparticles were not visible on Day 4 or Day 14. 1.5 mL of formulations were injected (vs 0.3 mL in the neurobehavioral studies) to minimize the possibility of erroneously sampling tissues that had not been injected with the formulations.[46] Injecting that volume of saline does not cause tissue injury.[46]

Figure 5.

Tissue reaction to PBS, NP–P-PBA35 and Dex@NP–P-PBA35, at 4 and 14 days after injection. H&E: Representative hematoxylin–eosin stained sections of muscles and adjacent loose connective tissue. Toluidine Blue: Representative toluidine blue stained sections of nerve. For H&E stained sections, n = 5, Scale bar: 200 μm. For toluidine blue stained sections, n = 4, Scale bar: 50 μm.

Table 1:

Myotoxicity and inflammation induced by PBS, NP–P-PBA35 and Dex@NP–P-PBA35, at 4 and 14 days after injection.[a]

| Sample | Myotoxicity Day 4 | Myotoxicity Day 14 | Inflammation Day 4 | Inflammation Day14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Treatment | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) |

| PBS | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) |

| p[b] > 0.05 | p> 0.05 | p> 0.05 | p > 0.05 | |

| NP–P-PBA35 | 3 (2–3) | 0 (0–0) | 1 (1–1.5) | 1 (1–1) |

| p[b] = 0.001 | p> 0.05 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |

| Dex@ | 3 (3–3.5) | 0 (0–0) | 2 (1.5–2) | 1 (1–2) |

| NP–P-PBA35 | ||||

| p[b] = 0.001 | p> 0.05 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

Inflammation scores: 0–4. Myotoxicity scores: 0–6. Data are medians with 25th and 75th percentiles in parentheses.

p-Values result from the comparison of injected formulations to the untreated group at Day 4 or Day 14. p-Values are from Mann-Whitney U-test. For all groups, n = 5.

Tissues were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) and slides were scored for inflammation (0–4) and myotoxicity (0–6; See Methods). Rats without treatment or injected with PBS had very minimal inflammation on days 4 and 14 after injection (median score = 0 for both). Rats injected with NP–P-PBA35 and Dex@NP–P-PBA35 showed mild inflammation on days 4 (median score = 1 for NP–P-PBA35 and median score = 2 for Dex@NP–P-PBA35, all p<0.001 compared with untreated rats in the same period) and day 14 (median score = 1 for both, all p<0.001 compared with untreated rats in the same period).

There was no myotoxicity in untreated rats or rats treated with PBS (median score = 0 for both). Moderate myotoxicity was observed in rats treated with NP–P-PBA35 and Dex@NP–P-PBA35 at day 4 (median score = 3 for both, all p<0.005 compared with untreated rats in the same period). Myotoxicity resolved completely for both NP–P-PBA35 and Dex@NP–P-PBA35 by day 14 (median score = 0 for both, all p>0.05 compared with untreated rats in the same period). Of note, the inflammation and myotoxicity scores of our formulations were comparable or better than those we have obtained with Exparel, a commercially available liposomal bupivacaine, in the same animal model.[47,48]

To examine neurotoxicity, the sciatic nerves were embedded in Epon and stained with toluidine blue. There was no nerve injury from NP–P-PBA35 and Dex@NP–P-PBA35 in any animal at either time point (Figure 5). These results demonstrated that our PBA based polymeric formulations have acceptable biocompatibility.

In conclusion, we utilized the reversible reactions between the diols on TTX and PBA to create a new method for TTX modification. TTX polymeric prodrugs were designed and prepared that had high EE% of TTX (>90%) and DL% of TTX of ~1%. The resultant TTX-loaded PBA-polymer nanoparticles provided sustained TTX release. These TTX sustained release depots provided prolonged local anesthesia with reduced systemic toxicity. Unlike conjugation to polymers by covalent ester bonds, this approach was able to provide nerve block without the need for concurrent use of chemical permeation enhancers.[14] We also proved that this strategy can co-deliver other drugs with diol groups, which can potentiate the effects of TTX, providing longer duration of local anesthesia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH R35GM131728 (to D.S.K.), the Anesthesia Research Ignition Award (to T.X. and D.S.K.), and NIH F32 CA257210 (to M.T.). We thank Dr. Bianca Silva from Analytical Chemistry Core Facility at Harvard Medical School for developing LC-MS method for TTX quantification. Figures are created with the support from BioRender.com

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The authors have cited additional references within the Supporting Information.[49]

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Tianrui Xue, Laboratory for Biomaterials and Drug Delivery, Department of Anesthesiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School Boston, Massachusetts, 02115, United States.

Yang Li, Laboratory for Biomaterials and Drug Delivery, Department of Anesthesiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School Boston, Massachusetts, 02115, United States.

Matthew Torre, Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School Boston, Massachusetts, 02115, United States.

Rachelle Shao, Laboratory for Biomaterials and Drug Delivery, Department of Anesthesiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School Boston, Massachusetts, 02115, United States.

Yiyuan Han, Laboratory for Biomaterials and Drug Delivery, Department of Anesthesiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School Boston, Massachusetts, 02115, United States.

Shuanglong Chen, Laboratory for Biomaterials and Drug Delivery, Department of Anesthesiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School Boston, Massachusetts, 02115, United States.

Daniel Lee, Laboratory for Biomaterials and Drug Delivery, Department of Anesthesiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School Boston, Massachusetts, 02115, United States.

Daniel S. Kohane, Laboratory for Biomaterials and Drug Delivery, Department of Anesthesiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School Boston, Massachusetts, 02115, United States.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- [1].Huang X, Brazel CS, J. Controlled Release 2001, 73, 121–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Natarajan JV, Nugraha C, Ng XW, Venkatraman S, J. Controlled Release 2014, 193, 122–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hardenia A, Maheshwari N, Hardenia SS, Dwivedi SK, Maheshwari R, Tekade RK, in Basic Fundamentals of Drug Delivery (Ed.: Tekade RK), Academic Press; 2019, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Langer R, Folkman J, Nature 1976, 263, 797–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hoffman A, Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 1998, 33, 185–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Vrignaud S, Benoit J-P, Saulnier P, Biomaterials 2011, 32, 8593–8604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Li Q, Li X, Zhao C, Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol 2020, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Santamaria CM, Woodruff A, Yang R, Kohane DS, Mater. Today 2017, 20, 22–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].White PF, Anesth. Analg 2005, 101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kohane DS, Yieh J, Lu NT, Langer R, Strichartz GR, Berde CB, Anesthesiology 1998, 89, 119–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kohane DS, Smith SE, Louis DN, Colombo G, Ghoroghchian P, Hunfeld NGM, Berde CB, Langer R, Pain 2003, 104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Makarova M, Rycek L, Hajicek J, Baidilov D, Hudlicky T, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 18338–18387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Epstein-Barash H, Shichor I, Kwon AH, Hall S, Lawlor MW, Langer R, Kohane DS, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 7125–7130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zhao C, Liu A, Santamaria CM, Shomorony A, Ji T, Wei T, Gordon A, Elofsson H, Mehta M, Yang R, Kohane DS, Nat. Commun 2019, 10, 2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ji T, Li Y, Deng X, Rwei AY, Offen A, Hall S, Zhang W, Zhao C, Mehta M, Kohane DS, Nat. Biomed. Eng 2021, 5, 1099–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wang D, Li Y, Deng X, Torre M, Zhang Z, Li X, Zhang W, Cullion K, Kohane DS, Weldon CB, Nat. Commun 2023, 14, 2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tong R, Cheng J, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2008, 47, 4830–4834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cheetham AG, Chakroun RW, Ma W, Cui H, Chem. Soc. Rev 2017, 46, 6638–6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ekladious I, Colson YL, Grinstaff MW, Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2019, 18, 273–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chien S-T, Suydam IT, Woodrow KA, Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 2023, 198, 114860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Khandare J, Minko T, Prog. Polym. Sci 2006, 31, 359–397. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Simons EJ, Bellas E, Lawlor MW, Kohane DS, Mol. Pharm 2009, 6, 265–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Santamaria CM, Zhan C, McAlvin JB, Zurakowski D, Kohane DS, Anesth. Analg 2017, 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kobayashi T, Nagashima Y, Kimura B, Fujii T, Shokuhin Eiseigaku Zasshi 2004, 45, 76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lu F, Zhang H, Pan W, Li N, Tang B, Chem. Commun 2021, 57, 7067–7082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Prossnitz AN, Pun SH, ACS Macro Lett. 2022, 11, 276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bapat AP, Roy D, Ray JG, Savin DA, Sumerlin BS, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 19832–19838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Li Y, Xiao W, Xiao K, Berti L, Luo J, Tseng HP, Fung G, Lam KS, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 2864–2869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cromwell OR, Chung J, Guan Z, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 6492–6495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Brooks WLA, Deng CC, Sumerlin BS, ACS Omega 2018, 3, 17863–17870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Liu Y, Wang Y, Yao Y, Zhang J, Liu W, Ji K, Wei X, Wang Y, Liu X, Zhang S, Wang J, Gu Z, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2023, 62, e202303097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kim KT, Cornelissen JJLM, Nolte RJM, v Hest JCM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 13908–13909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wang J, Wang Z, Yu J, Kahkoska AR, Buse JB, Gu Z, Adv. Mater 2020, 32, 1902004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Naito M, Ishii T, Matsumoto A, Miyata K, Miyahara Y, Kataoka K, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 10751–10755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Biswas S, Kinbara K, Niwa T, Taguchi H, Ishii N, Watanabe S, Miyata K, Kataoka K, Aida T, Nat. Chem 2013, 5, 613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Axthelm J, Askes SHC, Elstner M, Görls URGH, Bellstedt P, Schiller A, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 11413–11420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Roy D, Cambre JN, Sumerlin BS, Chem. Commun 2008, 2477–2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Chiefari J, Chong YK, Ercole F, Krstina J, Jeffery J, Le TPT, Mayadunne RTA, Meijs GF, Moad CL, Moad G, Rizzardo E, Thang SH, Macromolecules 1998, 31, 5559–5562. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Roy D, Sumerlin BS, ACS Macro Lett. 2012, 1, 529–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Li Y, Ji T, Torre M, Shao R, Zheng Y, Wang D, Li X, Liu A, Zhang W, Deng X, Yan R, Kohane DS, Nat. Commun 2023, 14, 6659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zhao C, Chen J, Ye J, Li Z, Su L, Wang J, Zhang Y, Chen J, Yang H, Shi J, Song J, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2021, 60, 14458–14466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Curley J, Castillo J, Hotz J, Uezono M, Hernandez S, Lim J-O, Tigner J, Chasin M, Langer R, Berde C, Anesthesiology 1996, 84, 1401–1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Padera RF, Tse JY, Bellas E, Kohane DS, Muscle Nerve 2006, 34, 747–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Slotkin Theodore A, MacKillop Emiko A, Ryde Ian T, Tate Charlotte A, Seidler Frederic J, Environ. Health Perspect 2007, 115, 93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lomonte B, Angulo Y, Rufini S, Cho W, Giglio JR, Ohno M, Daniele JJ, Geoghegan P, Gutiérrez JM, Toxicon 1999, 37, 145–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Barnet CS, Louis DN, Kohane DS, Anesth. Analg 2005, 101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Choi W, Aizik G, Ostertag-Hill CA, Kohane DS, Biomaterials 2024, 306, 122494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].McAlvin JB, Padera RF, Shankarappa SA, Reznor G,Kwon AH, Chiang HH, Yang J, Kohane DS, Biomaterials 2014, 35, 4557–4564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Turner AD, Dean KJ, Dhanji-Rapkova M, Dall’Ara S, Pino F, McVey C, Haughey S, Logan N, Elliott C, Gago-Martinez A, Leao JM, Giraldez J, Gibbs R, Thomas K, Perez-Calderon R, Faulkner D, McEneny H, Savar V, Reveillon D, Hess P, Arevalo F, Lamas JP, Cagide E, Alvarez M, Antelo A, Klijnstra MD, Oplatowska-Stachowiak M, Kleintjens T, Sajic N, Boundy MJ, Maskrey BH, Harwood DT, González Jartín JM, Alfonso A, Botana L, J. AOAC Int 2023, 106, 356–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.