Abstract

Serologic tools for Influenza A virus (FLUAV) antibody testing of wild birds are currently limited. In the present study, 2 commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) for detection of FLUAV antibodies, the IDEXX AI MultiS-Screen Ab Test and the ID VET ID Screen Influenza A Antibody Competition, were compared. Sera obtained from mallards (Anas platyrhynchos), experimentally infected with 8 FLUAV subtypes (N = 48), and field serum samples, collected from 11 wild bird species (N = 247), were tested. Overall, a substantial agreement was obtained between the 2 assays as applied to both experimental (86.5% agreement, κ = 0.69) and field samples (89.9% agreement, κ = 0.78). Based on the current study, doubtful results obtained with the ID VET assay should be re-tested to confirm their antibody status. Additionally, increasing the incubation period for the ID VET assay increases the test sensitivity but also increases the likelihood of generating false positive results. Overall, it is concluded that the 2 ELISAs can be used for FLUAV antibody screening in wild birds and that the sensitivity of the ID VET assay can be increased with slight modifications of the manufacturer’s instructions.

Keywords: Avian influenza, blocking enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, serology, wild birds

Surveillance for Influenza A virus (FLUAV) strains in wild bird populations in North America and Europe has provided valuable information related to the epidemiology and ecology of this virus.7,10 Historically, such studies have been based on viral isolation or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques. While these approaches are effective, FLUAV detection can be limited by a relatively short duration of viral excretion by the infected hosts9 and by spatial and temporal variation in prevalence of infection.10

Testing for antibodies to FLUAV is a common diagnostic tool used in poultry populations.12 The utility of this approach also has been demonstrated for influenza surveillance in wild birds.1–3 In wild waterbird populations of the orders Anseriformes, Charadriiformes, and Gruiformes, FLUAV antibody prevalence can be high (e.g., 30–50%)1,3; however, it is not clear how long these detectable antibodies persist. Although heterosubtypic immunity has been reported,4,6 the potential role of population immunity in regulating FLUAV prevalence or subtype diversity in waterbird populations also is unknown.

Hemagglutination and neuraminidase inhibition tests are commonly used in domestic poultry to screen populations for exposure to specific hemagglutinin or neuraminidase subtypes, respectively. Considering the potential subtype diversity of FLUAV strains in wild bird populations, these subtype-specific serologic tests are not well suited for wild bird serologic testing. The agar gel immunodiffusion test can be used as a group-specific serologic assay for FLUAV in wild birds but reportedly lacks sensitivity in waterfowl,5 and was shown to be less sensitive than a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).1 Over the last decade, multiple commercial ELISAs have been developed for detection of FLUAV antibodies in wild birds, and it is necessary to evaluate the performance of such tests in order to compare results and conclusions derived from studies utilizing these assays.1,11

In the current study, 2 commercial ELISAs for rapid screening of FLUAV nucleoprotein (NP) antibodies were tested. All FLUAV subtypes share the NP antigen and present little genetic variation, as compared to the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase proteins; therefore, the NP antigen represents a type A influenza–specific antigen. The sensitivity of the commercial assays was investigated to detect antibodies in sera obtained from mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) experimentally infected with 8 low pathogenic (LP) FLUAV subtypes and field serum samples collected from 11 wild bird species.

Serum samples were obtained from 40 mallards experimentally infected with 8 different subtypes of LP FLUAV strains and from 8 sham-inoculated birds (Table 1). Virus isolation and PCR testing verified infections of inoculated birds (unpublished data). Blood samples were collected at the end of the experiments (14 or 21 days postinfection), centrifuged for 30 min at 405 rcf, and sera stored at −20°C until testing. Also tested were 247 field serum samples collected from 11 species of wild birds representing 4 avian orders. Whole blood was collected via jugular, medial metatarsal, or basilic veins, as appropriate for each species (up to 1% of blood volume based on bird body weight).1 Blood samples were centrifuged within 24 hr of collection, and sera were held at −20°C until tested.

Table 1.

Comparison of the sensitivity of the 2 commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) for the detection of Influenza A virus in serum samples from experimentally infected mallards.

| Commercial ELISA* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Subtype | Strain | IDEXX | ID VET |

| H3N8 | A/Mallard/MN/Sg-00169/2007 | 5/5 | 3/5 |

| H4N6 | A/Surface water/MN/NW1-T/2006 | 5/5 | 4/5(+1) |

| H4N8 | A/Mallard/MN/Sg-00219/2007 | 5/5 | 4/5 |

| H5N2 | A/Mallard/MN/355779/2000 | 4/5 | 4/5 |

| H6N1 | A/Mallard/MN/Sg-00170/2007 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| H6N2 | A/Mallard duck/MN/Sg-00107/2007 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| H6N8 | A/Green-winged teal/MN/Sg-00197/2007 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| H8N4 | A/Mallard/MN/AI08–2721/2008 | 4/5 | 2/5 (+1) |

| Sham-inoculated birds | 0/8 | 0/8 | |

No. of positive/tested samples. Numbers in parentheses represent samples considered doubtful for the ID VET assayb (sample-to-negative control ratio value: 0.45–0.50).

All samples were tested with 2 commercial ELISA kits: 1) IDEXX IA MultiS-Screen Antibody Testa (hereafter, IDEXX assay) and 2) ID VET ID Screen Influenza A Antibody Competitionb (hereafter, ID VET assay). Both assays work in a blocking ELISA format. Briefly, serum samples are incubated in ELISA plates allowing anti-NP antibodies to bind to the antigen. After washing, an anti–antigen-conjugate is incubated and, if the test sample contains anti-NP antibodies, the conjugate is blocked from binding. After a second washing, an enzyme substrate is added. Color development depends on the presence or absence of anti-NP antibodies in the test samples. Although the 2 assays allow for the detection of FLUAV antibodies, further serologic tests, such as hemagglutination inhibition tests, are required to identify subtype-specific antibodies.

Serum samples were thawed and tested with both ELISAs within 24 hr. Samples were maintained at 4°C between testing with the 2 assays. Sera and reagents were maintained at room temperature for 1 hr before the testing was performed. The ELISAs were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, serum samples were diluted 1:10 (IDEXX) or 1:20 (ID VET) with sample diluent provided by the manufacturers, and 100 μl (IDEXX) or 200 μl (ID VET) of the diluted samples were dispensed into the antigen-coated test plates. Samples were incubated for 1 hr at 23°C (IDEXX) or 36°C (ID VET) and washed 3–5 times with approximately 350 μl of wash solution (provided in kits), per well. Next, 100 μl (IDEXX) or 50 μl (ID VET) of conjugate were added to each well, and plates were incubated for 30 min at 23°C. Each well was washed again 3 times, as described above. Finally, 100 μl (IDEXX) or 50 μl (ID VET) of substrate solution was added to each well, and plates were incubated at 23°C in the dark for 15 min (IDEXX) or 10 min (ID VET). The reactions were stopped by adding 100 μl (IDEXX) or 50 μl (ID VET) of stop solution. Sample absorbance was measured at 655 nm (IDEXX) and 450 nm (ID VET) with a microplate reader.c For both assays, serum samples with a sample-to-negative control (S/N) ratio value greater than or equal to 0.50 were considered negative. For the ID VET assay, S/N ratio values of 0.45–0.50 were considered as doubtful, according to the manufacturer instructions. Serum samples with S/N ratio values below 0.50 (IDEXX) and 0.45 (ID VET) were considered positive for the presence of FLUAV antibodies.

The ID VET assay protocol indicates that increased sensitivity can be obtained by overnight incubation of serum samples. The effect of the incubation period on FLUAV antibody detection was investigated by testing 40 samples from experimentally infected mallards and 8 samples from shaminoculated mallards, with incubation periods of 1, 2, 4, 6, and 12 hr.

Percentage agreement and Cohen kappa coefficient (κ) were calculated to estimate agreement between the 2 ELISAs and between samples tested twice with the same assay. For kappa coefficient, κ < 0.2 indicates a slight agreement, 0.2 < κ < 0.4 indicates a fair agreement, 0.4 < κ < 0.6 indicates a moderate agreement, 0.6 < κ < 0.8 indicates a substantial agreement, and κ > 0.8 indicates a perfect agreement.8 For the ID VET assay, doubtful samples were considered negative in the calculation of the percentage agreement and Cohen kappa coefficient. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to measure the association between S/N ratios obtained with the 2 ELISAs. Statistical analyses were performed with the R software version 2.10.1.d

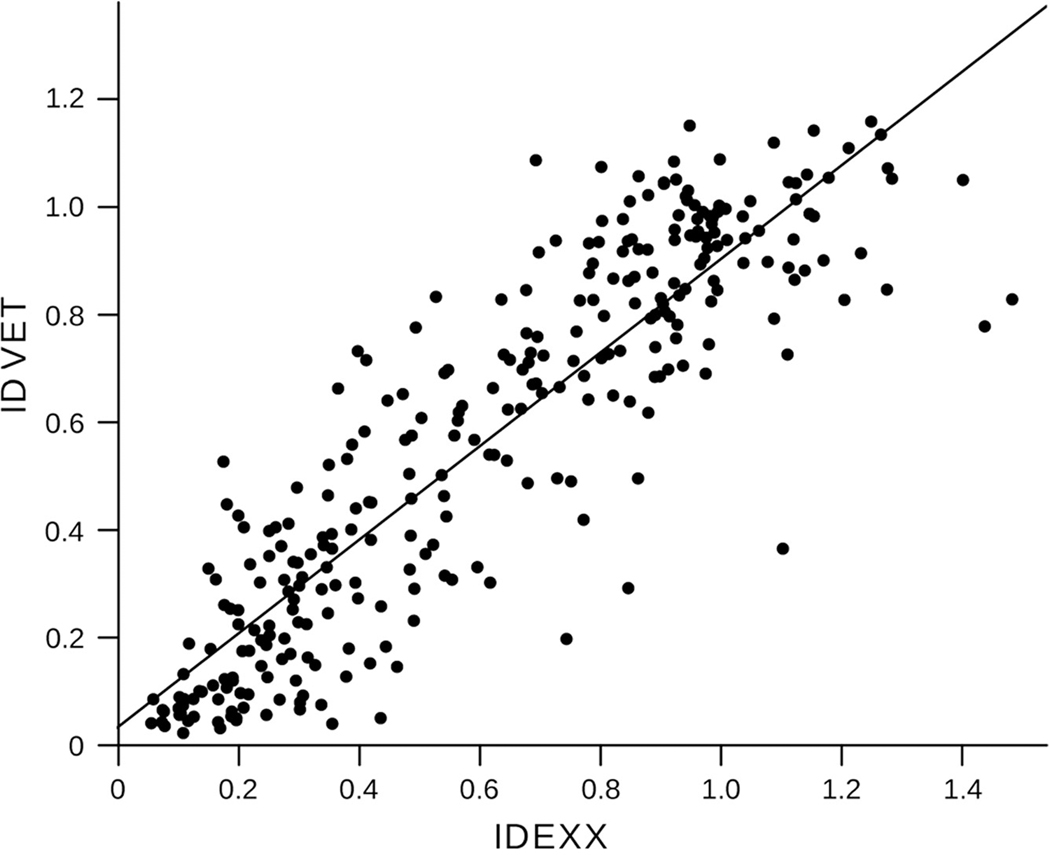

The ELISA results from the experimentally infected birds are presented in Table 1. Overall, a substantial agreement was obtained between the 2 assays (86.5% agreement, κ = 0.69). The S/N ratio values obtained with the 2 ELISAs were significantly correlated (r = 0.95, df = 46, P < 0.001; Fig. 1). Both assays failed to detect antibodies in 2 mallards with confirmed infections (inoculated with H5N2 and H8N4 LP FLUAV strains), which may have resulted from decreased sensitivity or the failure of these mallards to seroconvert following infection. In addition, the ID VET assay did not detect FLUAV antibodies in 6 infected mallards (4 negative plus 2 doubtful) that tested positive with the IDEXX assay. Neither assay yielded positive results for the sham-inoculated negative control birds. Collectively, results suggest that both assays have a good sensitivity for the detection of FLUAV antibodies in experimentally infected mallards. However, it also suggests that for the detection in field samples, false-negative results may lead to an overall underestimation of the antibody prevalence, which may be addressed by testing samples with different commercial ELISAs or other types of assays (e.g., agar gel immunodiffusion test).

Figure 1.

Simple regression for the sample-to-negative control ratio values obtained with the 2 commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, including all tested samples (N = 295; adjusted R2 = 0.7856, P < 0.001).

The S/N ratio values obtained with both assays were also significantly correlated for field samples (r = 0.88, df = 245, P < 0.001; Fig. 1). The overall agreement between the assays was substantial (89.9% agreement, κ = 0.78). In total, 77 serum samples tested positive with both ELISAs, 25 tested positive with 1 assay (12 and 13 samples tested positive with the IDEXX assay and ID VET assay, respectively), and 145 tested negative with both assays. Agreement ranged from moderate to perfect in the species studied (Table 2). Such variation may have reflected species-specific variations in antibody response or the timing of infections, which could not be determined for the field samples.

Table 2.

Comparison of the 2 commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) for the detection of Influenza A virus in serum samples from wild birds.

| Commercial ELISA* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order/Common name | Scientific name | N | IDEXX | ID VET | Percent agreement | κ† |

| Anseriformes | ||||||

| Green-winged teal | Anas corolinensis | 30 | 12 | 13 (+3) | 83.3 | 0.66 |

| American wigeon | Anas americana | 20 | 6 | 6 | 100 | 1.0 |

| Mallard | Anas platyrhynchos | 30 | 13 | 13 (+1) | 80 | 0.59 |

| Canada goose | Branta canadensis | 30 | 15 | 11 | 86.7 | 0.73 |

| Charadriiformes | ||||||

| Laughing gull | Larus atricilla | 30 | 12 | 13 (+1) | 86.7 | 0.73 |

| Ruddy turnstone | Arenaria interpres | 30 | 19 | 18 (+1) | 96.7 | 0.93 |

| Sanderling | Calidris alba | 20 | 2 | 2 | 90 | 0.44 |

| Gruiformes | ||||||

| American coot | Fulica americana | 30 | 10 | 11 (+1) | 90 | 0.78 |

| Passeriformes | ||||||

| American crow | Corvus brochyrhynchos | 10 | 0 | 0 | 100 | NA |

| Common starling | Sturnus vulgaris | 10 | 0 | 0 | 100 | NA |

| White-throated sparrow | Zonotrichia albicollis | 7 | 0 | 0 | 100 | NA |

Number of positive samples. Numbers in parentheses represent samples considered doubtful for the ID VET assayb (sample-to-negative control ratio value: 0.45–0.50).

κ = Cohen kappa coefficient; NA = not applicable.

Also investigated was the repeatability of each assay by comparing the S/N ratio values obtained for replicate testing of samples (N = 48, tested twice with each assay). For the IDEXX assay, a perfect agreement was obtained between replicates (100% agreement, κ = 1), consistent with a previous study.1 For the ID VET assay, the agreement between replicates was almost perfect (92% agreement, κ = 0.81). Four samples had an S/N ratio value lower than 0.45 with one of the assays and between 0.45 and 0.50 on the other, highlighting the importance of retesting samples considered as doubtful, as recommended by the manufacturer.

The ID VET assay protocol suggests that the sensitivity of the assay can be increased by overnight incubation of serum samples. As part of the current study, the effect of increased incubation was investigated on the S/N ratio value for this assay (Table 3). Overall, the mean S/N ratio value decreased when incubation periods higher than 1 hr were performed (Table 3). In particular, an incubation of 4 hr provided perfect results as all FLUAV inoculated birds tested positive. A longer incubation (6 or 12 hr) provided consistent results for the FLUAV-infected birds, but several of the negative controls (sham-inoculated birds) also tested positive or doubtful. This suggests that increasing the incubation period for the ID VET assay will increase sensitivity, but will also increase the likelihood of false-positive results.

Table 3.

Effect of the incubation period on the results obtained with the ID VET enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of Influenza A virus in experimentally infected and sham-inoculated mallards.*

| 1 hr | 2 hr | 4 hr | 6 hr | 12 hr | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | N | Mean S/N | POS | Mean S/N | POS | Mean S/N | POS | Mean S/N | POS | Mean S/N | POS |

| Sham-inoculated | 8 | 0.91 | 0 | 0.93 | 0 | 0.75 | 0 | 0.70 | 0 (+1) | 0.48 | 4 (+1) |

| Experimertally-infected birds | 40 | 0.33 | 32 (+2) | 0.27 | 34 (+3) | 0.17 | 40 | 0.12 | 40 | 0.17 | 40 |

S/N = sample-to-negative control ratio; POS = positive. Numbers in parentheses represent samples considered doubtful (S/N value: 0.45–0.50).

To conclude, a substantial agreement between the IDEXX and ID VET assays was found, suggesting that results and conclusion derived from the 2 ELISAs can reasonably be compared. For the ID VET assay, doubtful results need to be retested to confirm their status, and in spite of possible increase in test sensitivity, overnight incubation may result in increased false-positive results.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Taiana Costa and Whitney Kistler for providing serum samples.

Funding

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Health and Human Services, under contract no. HHSN266200700007C, funded the current work. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Sources and manufacturers

IDEXX Laboratories Inc., Westbrook, ME.

ID VET, Montpellier, France.

Benchmark microplate reader, Microplate Manager v. 5.0.1; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Brown JD, Luttrell MP, Berghaus RD, et al. : 2010, Prevalence of antibodies to type A influenza virus in wild avian species using two serologic assays. J Wildl Dis 46:896–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown JD, Stallknecht DE, Berghaus RD, et al. : 2009, Evaluation of a commercial blocking enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to detect avian influenza virus antibodies in multiple experimentally infected avian species. Clin Vaccine Immunol 16:824–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Marco MA, Campitelli L, Foni E, et al. : 2004, Influenza surveillance in birds in Italian wetlands (1992–1998): is there a host restricted circulation of influenza viruses in sympatric ducks and coots? Vet Microbiol 98:197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fereidouni SR, Starick E, Beer M, et al. : 2009, Highly pathogenic avian influenza virus infection of mallards with homo- and heterosubtypic immunity induced by low pathogenic avian influenza viruses. PLoS One 4:e6706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higgins DA: 1998, Comparative immunology of avian species. In: Poultry immunology, ed. Davison TF, Morris TR, Payne LN, pp. 149–205. Carfax Publishing, Abingdon, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jourdain E, Gunnarsson G, Wahlgren J, et al. : 2010, Influenza virus in a natural host, the mallard: experimental infection data. PLoS One 5:e8935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krauss S, Walker D, Pryor SP, et al. : 2004, Influenza A viruses of migrating wild aquatic birds in North America. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 4:177–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landis JR, Koch GG: 1977, The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Latorre-Margalef N, Gunnarsson G, Munster VJ, et al. : 2009, Effects of influenza A virus infection on migrating mallard ducks. Proc Biol Sci 276:1029–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munster VJ, Baas C, Lexmond P, et al. : 2007, Spatial, temporal, and species variation in prevalence of influenza A viruses in wild migratory birds. PLoS Pathog 3:e61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pérez-Ramírez E, Rodríguez V, Sommer D, et al. : 2010, Serologic testing for avian influenza viruses in wild birds: comparison of two commercial competition enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Avian Dis 54:729–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spackman E, Suarez DL, Senne DA: 2008, Avian influenza diagnostics and surveillance methods. In: influenza Avian, ed. Swayne DE, pp. 299–308. Blackwell, Ames, IA. [Google Scholar]