SUMMARY.

Avian influenza virus (AIV) prevalence in wild aquatic bird populations varies with season, geographic location, host species, and age. It is not clear how age at infection affects the extent of viral shedding. To better understand the influence of age at infection on viral shedding of wild bird–origin low pathogenicity avian influenza (LPAI) viruses, mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) of increasing age (2 wk, 1 mo, 2 mo, 3 mo, and 4 mo) were experimentally inoculated via choanal cleft with a 106 median embryo infectious dose (EID50) of either A/Mallard/MN/355779/00 (H5N2) or A/Mallard/MN/199106/99 (H3N8). Exposed birds in all five age groups were infected by both AIV isolates and excreted virus via the oropharynx and cloaca. The 1-month and older groups consistently shed virus from 1 to 4 d post inoculation (dpi), whereas, viral shedding was delayed by 1 d in the 2-wk-old group. Past 4 dpi, viral shedding in all groups varied between individual birds, but virus was isolated from some birds in each group up to 21 dpi when the trial was terminated. The 1-mo-old group had the most productive shedding with a higher number of cloacal swabs that tested positive for virus over the study period and lower cycle threshold values on real-time reverse-transcription PCR. The viral shedding pattern observed in this study suggests that, although mallards from different age groups can become infected and shed LPAI viruses, age at time of infection might have an effect on the extent of viral shedding and thereby impact transmission of LPAI viruses within the wild bird reservoir system. This information may help us better understand the natural history of these viruses, interpret field and experimental data, and plan future experimental trials.

Keywords: Anas platyrhynchos, avian influenza virus, mallard, age, viral shedding

RESUMEN.

Nota de Investigación—Efecto de la edad en la diseminación del virus de influenza aviar en patos de collar (Anas platyrhychos).

La prevalencia del virus de influenza aviar en poblaciones de aves silvestres acuáticas varía de acuerdo con la estación, con la locación geográfica, la especie hospedadora y con la edad. No esta definido como la edad afecta el nivel de diseminación viral. Para entender mejor la influencia de la edad en el momento de infección sobre la diseminación del virus de la influenza aviar de baja patogenicidad provenientes de aves silvestres, se inocularon experimentalmente patos de diferentes edades (dos semanas, un mes, tres y cuatro meses) por vía de la hendidura palatina con 106 dosis infecciosas 50% en embrión (EID50) de un virus denominado A/pato de collar/MN/355779/00 (H5N2) o con otro denominado A/pato de collar/MN/199106/99 (H3N8). Aves de los cinco grupos de edad se infectaron con ambos aislados del virus de influenza aviar y mostraron excreción del virus por vía de la orofaringe y por la cloaca. Las aves de un mes y de mayor edad diseminaron virus de manera consistente desde el día uno al día 4 post inoculación, mientras que en el grupo de dos semanas de edad la diseminación se retardo un día. Después del día cuatro después de la inoculación, la diseminación en todos los grupos presentó variaciones entre individuos, pero el virus fue aislado de algunas aves en cada grupo hasta los 21 días post infección cuando se terminó el experimento. El grupo de aves de un mes de edad mostró la mayor diseminación con mayor número de hisopos cloacales positivos para el virus durante el periodo del estudio y con los valores de ciclos umbrales más bajos por la prueba de transcripción reversa y reacción en cadena de la polimerasa en tiempo real. El patrón de diseminación observado en este estudio sugiere que aun cuando patos de diferente grupos de edad pueden infectarse y diseminar el virus de influenza aviar de baja patogenicidad, la edad en el momento de la infección puede tener un efecto en los niveles de diseminación viral y por consecuencia un impacto en la transmisión de estos virus dentro del sistema de reservorios en las aves silvestres. Esta información puede ser útil para el mejor conocimiento de la historia natural de estos virus, la interpretación de datos experimentales y para la planificación de futuros experimentos.

Wild aquatic birds, especially those from the orders Anseriformes and Charadriiformes, are believed to be the natural reservoir for avian influenza virus (AIV) (11,13). Within this reservoir system, AIV prevalence varies with season, geographic location, and host species (12). Movement and age of birds appear to be important in the natural history of AIV and are correlated with seasonal effects (4). In wild duck populations, peak AIV prevalence occurs in the late summer and early fall, when high concentrations of susceptible juvenile ducks (approximately 2–3 mo old) congregate at premigrational staging areas (2,3,4).

Age can affect the outcome of infection with avian reovirus in chickens (7,9), hepatitis B virus (5) and highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses (8) in Pekin ducks (Anas platyrhynchos domesticus). These effects have been attributed to both increasing maturation of the immune system with age and a link between host cell maturation and the capacity to support viral replication (5). Adult Japanese quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica) experimentally inoculated with H9N2 AIV developed a more protective immunity than juvenile and aged individuals as measured by clinical and serologic responses (6). At present there is little information on the potential effects of the age at infection on extent of viral shedding associated with a low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) virus infection in ducks. Such information is needed to fully evaluate experimental and field data often derived from birds of varying ages. The objective of this study was to investigate the viral shedding pattern of different age classes of mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) inoculated with two LPAI viruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses.

LPAI viruses A/Mallard/MN/355779/00 (H5N2) and A/Mallard/MN/199106/99 (H3N8) were used in this study. These viruses were originally isolated in specific pathogen free (SPF) embryonated chicken eggs (ECE) from cloacal swab material. Virus stocks were propagated by second passage in 9- to 11-day-old SPF ECE. A sham inoculum was prepared using uninfected brain heart infusion solution. Serial titrations were performed in SPF ECE and median embryo infectious dose (EID50) titers were determined by testing hemagglutination activity as previously described (14).

Animals.

One-day-old mallards were purchased from a commercial source (Murray McMurray Hatchery, Webster City, IA) and raised under confined conditions until they were utilized in this study. Both males and females were included in approximately equal numbers. In order to acclimatize the birds, 3 days before inoculation the birds were housed in groups of five in self-contained isolation units ventilated under negative pressure with high-efficiency particulate air–filtered air. Food and water were provided ad libitum. All birds were negative for antibodies to type A influenza virus by agar gel precipitation (AGP) test and negative for AIV by virus isolation (VI) and real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR), on cloacal and oropharyngeal (OP) swabs, tested on 0 days postinoculation (dpi). General animal care was provided under an animal use protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Georgia.

Experimental design.

Five age classes of Mallards were used: 2-wk-old, and 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-mo-old. For each age class, 15 mallards were evenly divided between two treatments and one negative control group, with five birds in each group. Treatment groups were inoculated via choanal cleft with a volume of 0.1 ml containing an infectious titer of 106 EID50 of one of the two LPAI viruses. Back titers varied from 105.27 to 106.36 EID50. Control groups were sham inoculated with 0.1 ml of brain heart infusion solution via choanal cleft. Animals were evaluated twice daily. Oropharyngeal and cloacal swabs were collected on 0, 1, 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 14, 16, and 21 dpi and blood samples were collected on 0, 14, and 21 dpi. At 21 dpi, birds were humanely euthanatized by CO2 inhalation. Experimental infections were performed in a BSL-Ag2+ facility at the Poultry Diagnostic and Research Center, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Georgia.

Virus isolation.

Cloacal and OP swabs were stored at −70°C until analyses were performed. Previously described procedures were used to test the swabs by VI in ECE (14).

RNA extraction.

RNA was extracted from cloacal and oropharyngeal swab material by using the MagMAX™-96 AI/ND Viral RNA Isolation Kit (Ambiron, Austin, TX) using the Thermo Electron KingFisher magnetic particle processor (Thermo Electron Corporation, Waltham, MA).

Real time RT-PCR.

RNA was tested for AIV by quantitative rRT-PCR targeted to the influenza matrix gene as previously described (10). Samples with a cycle threshold (Ct) value equal or less than 40.00 were considered positive on rRT-PCR.

Serology.

Blood samples were collected from the right jugular vein, and serum samples were stored at −20°C until they were tested using AGP as previously described (14). Serum samples of the 21 dpi also were tested with the multiS-screen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (bELISA) AIV antibody test kit (IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, ME) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis.

The number of virus isolation per each bird for each age class was analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric one-way analysis of variance, followed by nonparametric Bonferroni multiple comparisons, using α = 0.10 overall comparisons.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

All the age classes were infected with both A/Mallard/MN/355779/00 (H5N2) (Table 1) and A/Mallard/MN/199106/99 (H3N8) (Table 2) as shown by viral shedding and seroconversion (Table 3) after inoculation, confirming the susceptibility of all the age classes to infection with these LPAI viruses. All treatment birds of the 2-, 3-, and 4-mo-old groups inoculated with either AIV isolate were seropositive on both 14 and 21 dpi (Table 3). Although all treatment birds in the 2-wk-old and 1-mo-old groups were seropositive on 14 dpi, two birds in the 2-wk-old group and one bird in the 1-mo-old group that were inoculated with A/Mallard/MN/199106/99 (H3N8) tested negative by AGP on 21 dpi; these three birds tested positive by bELISA on 21 dpi. The bELISA has been reported to be more sensitive than AGP for detecting antibodies to AIV infection in wild birds (1).

Table 1.

Virus shedding pattern as determined by VI and rRT-PCRA of mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) of different age classes inoculatedB with A/Mallard/MN/355779/00 (H5N2).

| Days post inoculation; number of positives (n = 5) |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

14 |

16 |

21 |

||||||||||||

| Age class | SwabC | VI | rRT-PCR | VI | rRT-PCR | VI | rRT-PCR | VI | rRT-PCR | VI | rRT-PCR | VI | rRT-PCR | VI | rRT-PCR | VI | rRT-PCR | VI | rRT-PCR | VI | rRT-PCR |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 wk | OP | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| CLO | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 mo | OP | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| CLO | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 mo | OP | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CLO | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 mo | OP | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| CLO | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 mo | OP | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CLO | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

rRT-PCR cut off: Ct 40.00.

Ducks were inoculated via choanal ccenter with a volume of 0.1 ml containing an infectious titer of 106 EID50.

CLO = cloacal swab.

Table 2.

Virus shedding pattern as determined by VI and rRT-PCRA of mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) of different age classes inoculatedB with A/Mallard/MN/199106/99 (H3N8).

| Days post inoculation; number of positives (n = 5) |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

14 |

16 |

21 |

||||||||||||

| Age class | Swab | VI | rRT-PCR | VI | rRT-PCR | VI | rRT-PCR | VI | rRT-PCR | VI | rRT-PCR | VI | rRT-PCR | VI | rRT-PCR | VI | rRT-PCR | VI | rRT-PCR | VI | rRT-PCR |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 wk | OP | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CLO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 mo | OP | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| CLO | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 mo | OP | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| CLO | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 mo | OP | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CLO | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 mo | OP | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| CLO | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

rRT-PCR: real time RT-PCR - cut off: Ct 40.00.

Ducks were inoculated via choanal cleft with a volume of 0.1 ml containing an infectious titer of 106 EID50.

Table 3.

SeroconversionA in mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) of different age classes inoculatedB with LPAI viruses.

| Age class |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VirusC | dpi | 2 wk | 1 mo | 2 mo | 3 mo | 4 mo |

|

| ||||||

| H5N2 | 14 | 5/5D | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| 21 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | |

| H3N8 | 14 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| 21 | 5/5F | 5/5E | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | |

As detected by the AGP test.

Ducks were inoculated via choanal cleft with a volume of 0.1 ml containing an infectious titer of 106 EID50 of one of the two LPAI viruses.

H5N2: A/Mallard/MN/355779/00 (H5N2); H3N8: A/Mallard/MN/199106/99 (H3N8).

Number of birds that seroconverted/total number of inoculated ducks.

Samples of 21 dpi were also tested by bELISA. For the H3N8 treatment group, two birds in the 2-wk-old group and one bird in the 1-mo-old group tested negative by AGP but positive by bELISA.

With the exception of the 2-wk-old group, birds in all treatment groups consistently excreted virus via oropharynx and cloaca from 1 to 4 dpi, as detected on VI and rRT-PCR (Tables 1 and 2). Beyond 4 dpi viral shedding varied between individual birds, even within the same treatment group, with birds shedding virus via oropharynx up to 21 dpi. Viral shedding in the 2-wk-old group was delayed 1 day, with consistent shedding starting on 2 dpi and intermittent shedding by individual birds up to 16 dpi. This observed delay in young birds might be related to host cell maturation and the capacity to support viral replication, as previously observed for hepatitis B virus (5) and avian reovirus (7). To ensure accuracy, all the rRT-PCR tests were run with negative and positive controls, for both the RNA extraction and the rRT-PCR. The possible presence of PCR inhibitors in the swab samples might explain the apparent lack of sensitivity observed of the rRT-PCR compared to VI (Tables 1 and 2). However, further tests to investigate the presence of PCR inhibitors were not performed.

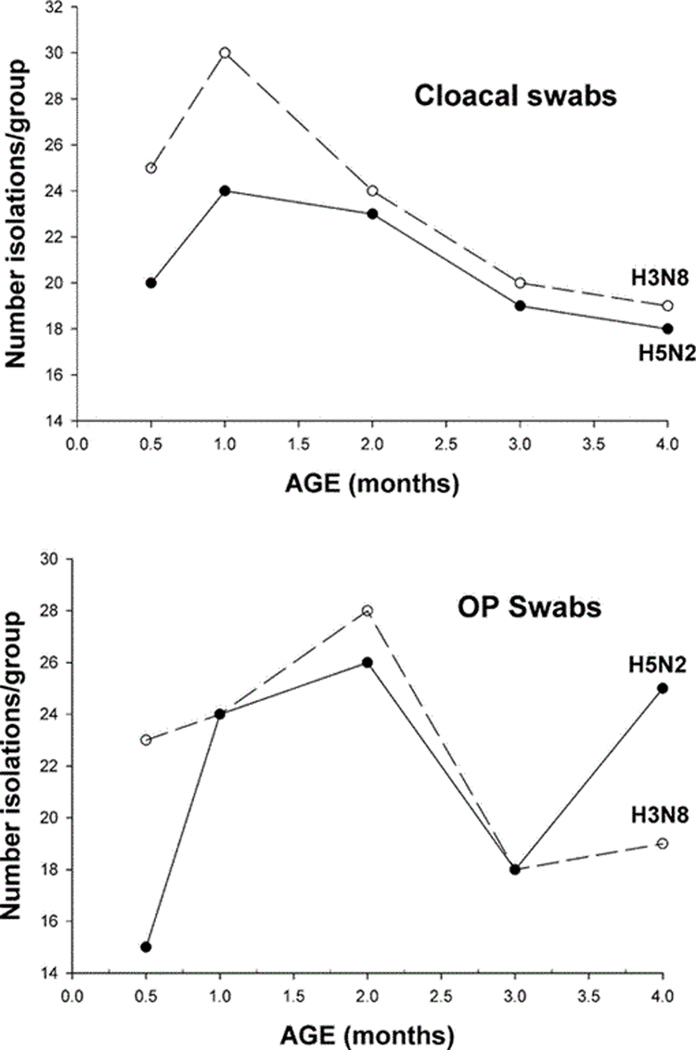

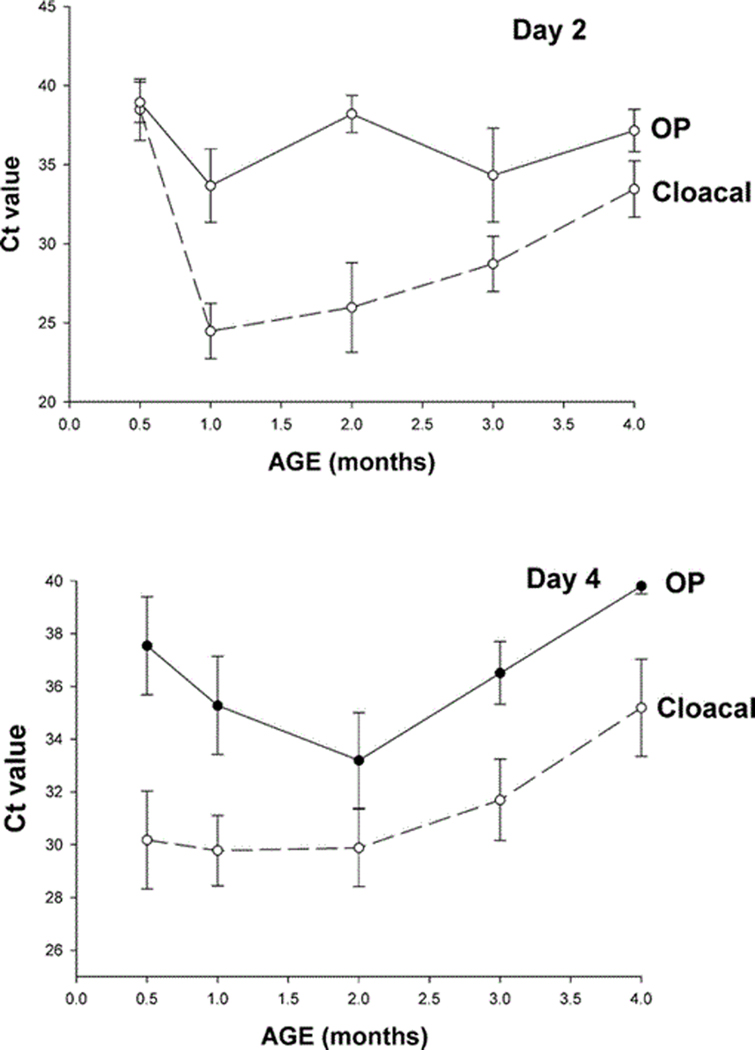

The 1-mo-old group had the highest number of virus isolations from cloaca compared to the other age groups (Fig. 1); this was consistent with both viruses. However, this difference was not statistically significant for the H5N2 group and was only statistically significant for the H3N8 group in the comparison between the 1-mo-old and the 4-mo-old groups (Kruskal–Wallis test P = 0.063, pairwise comparisons performed using a nonparametric Bonferroni test with α = 0.10 overall comparisons). Results were not as clear with virus isolations from the OP swabs, but, with both viruses, the highest number of virus isolations was observed in the 2-mo-old group, which was significantly higher than the number of virus isolations in the 2-wk-old group infected with H5N2 using the same statistical tests (Kruskal–Wallis test for overall group comparisons, P = 0.006, and nonparametric Bonferroni test with α = 0.10 for pairwise comparison). The difference in virus isolation from oropharynx observed in the H3N8 group was statistically significant between age classes (P = 0.057); however the Bonferroni pairwise test found no significant difference between groups. To estimate the relative amount of virus in cloacal and OP swabs, mean Ct values (combined from both viruses, n = 10) were compared between groups on 2 and 4 dpi (Fig. 2). On both days, the lowest mean Ct values were observed in cloacal swabs from the 1-mo-old birds; this is consistent with virus isolation results. The average Ct values from OP swabs were always higher than those observed from cloacal swabs (Fig. 2) supporting replication of the viruses in the gastrointestinal tract, as previously reported for LPAI viruses (15).

Fig. 1.

Number of virus isolations from cloacal and OP swabs of mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) of different age classes inoculated with LPAI viruses A/Mallard/MN/355779/00 (H5N2) and A/Mallard/MN/199106/99 (H3N8).

Fig. 2.

Mean Ct values (combined from both viruses, n = 10) from cloacal and OP swabs of mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) of different age classes inoculated with LPAI viruses A/Mallard/MN/355779/00 (H5N2) and A/Mallard/MN/199106/99 (H3N8) on 2 and 4 days postinoculation.

Our results suggest that, although age does not affect susceptibility to infection with LPAI virus, it does influence the extent of viral shedding. The higher prevalence of infection observed in juvenile ducks under field situations (2,3,4) has generally been attributed to acquisition of population immunity to these viruses. It is further apparent from our results that even minor differences in age can influence experimental outcomes; and, in order to compare such results, it would be beneficial to utilize birds of similar age.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this work was provided by the ARS CRIS project #6612-32000-048-00D and the Specific Cooperative Agreement #58-6612-2-0220 between the Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory and the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study. Additionally, this work was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. HHSN266200700007C. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Abbreviations:

- AGP

agar gel precipitation

- AIV

avian influenza virus

- bELISA

blocking enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- Ct

cycle threshold

- dpi

days postinoculation

- ECE

embryonated chicken eggs

- EID50

median embryo infectious dose

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- HPAI

highly pathogenic avian influenza

- LPAI

low pathogenicity avian influenza

- OP

oropharyngeal

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- rRT-PCR

real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

- SPF

specific pathogen free

- VI

virus isolation

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown JD, Stallknecht DE, Berghaus RD, Luttrell MP, Velek K, Kistler W, Costa T, Yabsley MJ, and Swayne D. Evaluation of a commercial blocking ELISA as a serologic assay for detecting avian influenza virus infection in multiple experimentally infected avian species. Clin. Vaccine Immunol 16:824–829. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deibel R, Emord DE, Dukelow W, Hinshaw VS, and Wood JM. Influenza viruses and paramyxoviruses in ducks in the Atlantic flyway, 1977–1983, including an H5N2 isolate related to the virulent chicken virus. Avian Dis. 29:970–985. 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halvorson DA, Kelleher CJ, and Senne DA. Epizootiology of avian influenza: effect of season on incidence in sentinel ducks and domestic turkeys in Minnesota. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 49:914–919. 1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hinshaw VS, Wood JM, Webster RG, Deibel R, and Turner B. Circulation of influenza viruses and paramyxoviruses in waterfowl originating from two different areas of North America. Bull. World Health Organ 63:711–719. 1985. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jilbert AR, Botten JA, Miller DS, Bertram EM, Hall PM, Kotlarski J, and Burrell CJ. Characterization of age- and dose-related outcomes of duck hepatitis B virus infection. Virology 244:273–282. 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavoie ET, Sorrell EM, Perez DR, and Ottinger MA. Immunosenescence and age-related susceptibility to influenza virus in Japanese quail. Dev. Comp. Immunol 31:407–414. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montgomery RD, Villegas P, and Kleven SH. Role of route of exposure, age, sex, and type of chicken on the pathogenicity of avian reovirus strain 81–176. Avian Dis. 30:460–467. 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pantin-Jackwood MJ, Suarez DL, Spackman E, and Swayne DE. Age at infection affects the pathogenicity of Asian highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 viruses in ducks. Virus Res. 130:151–161. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roessler DE, and Rosenberger JK. In vitro and in vivo characterization of avian reoviruses. III. Host factors affecting virulence and persistence. Avian Dis. 33:555–565. 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spackman E, and Suarez DL. Type A influenza virus detection and quantitation by real-time RT-PCR. In: Avian influenza virus. Spackman E, ed. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. pp. 19–26, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stallknecht DE. Ecology and epidemiology of avian influenza viruses in wild bird populations: waterfowl, shorebirds, pelicans, cormorants, etc et al. Avian Dis. 47:61–69. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stallknecht DE, and Brown JD. Wild birds and the epidemiology of avian influenza. J. Wildl. Dis 43:S15–S20. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swayne DE, and Halvorson DA. Influenza. In: Diseases of poultry, 11th ed. Saif YM, Barnes HJ, Fadly AM, Glisson LR, McDougald LR, and Swayne DE, eds. Iowa State Press, Ames, IA. pp. 135–160. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swayne DE, Senne DA, and Beard CW. Avian influenza. In: A laboratory manual for the isolation and identification of avian pathogens, 4th ed. Swayne DE, Glisson JR, Jackwood MW, Pearson JE, and Reed WM, eds. American Association of Avian Pathologists, Kennett Square, PA. pp. 150–155. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webster RG, Yakhno M, Hinshaw VS, Bean WJ, and Murti KG. Intestinal influenza: replication and characterization of influenza viruses in ducks. Virology 84:268–278. 1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]