Abstract

Background

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia. The incidence of AD rises exponentially with age and its prevalence will increase significantly worldwide in the next few decades. Inflammatory processes have been suspected in the pathogenesis of the disease.

Objectives

To review the efficacy and side effects of aspirin, steroidal and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in the treatment of AD, compared to placebo.

Search methods

We searched ALOIS: the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group’s Specialized Register on 12 April 2011 using the terms: aspirin OR "cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor" OR aceclofenac OR acemetacin OR betamethasone OR celecoxib OR cortisone OR deflazacort OR dexamethasone OR dexibruprofen OR dexketoprofen OR diclofenac sodium OR diflunisal OR diflusinal OR etodolac OR etoricoxib OR fenbufen OR fenoprofen OR flurbiprofen OR hydrocortisone OR ibuprofen OR indometacin OR indomethacin OR ketoprofen OR lumiracoxib OR mefenamic OR meloxicam OR methylprednisolone OR nabumetone OR naproxen OR nimesulide OR "anti‐inflammatory" OR prednisone OR piroxicam OR sulindac OR tenoxicam OR tiaprofenic acid OR triamcinolone OR NSAIDS OR NSAID. ALOIS contains records of clinical trials identified from monthly searches of a number of major healthcare databases (including MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, LILACS), numerous trial registries (including national, international and pharmacuetical registries) and grey literature sources.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials assessing the efficacy of aspirin, steroidal and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs in AD.

Data collection and analysis

One author assessed risk of bias of each study and extracted data. A second author verified data selection.

Main results

Our search identified 604 potentially relevant studies. Of these, 14 studies (15 interventions) were RCTs and met our inclusion criteria. The numbers of participants were 352, 138 and 1745 for aspirin, steroid and NSAIDs groups, respectively. One selected study comprised two separate interventions. Interventions assessed in these studies were grouped into four categories: aspirin (three interventions), steroids (one intervention), traditional NSAIDs (six interventions), and selective cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) inhibitors (five interventions). All studies were evaluated for internal validity using a risk of bias assessment tool. The risk of bias was low for five studies, high for seven studies, and unclear for two studies.There was no significant improvement in cognitive decline for aspirin, steroid, traditional NSAIDs and selective COX‐2 inhibitors. Compared to controls, patients receiving aspirin experienced more bleeding while patients receiving steroid experienced more hyperglycaemia, abnormal lab results and face edema. Patients receiving NSAIDs experienced nausea, vomiting, elevated creatinine, elevated LFT and hypertension. A trend towards higher death rates was observed among patients treated with NSAIDS compared with placebo and this was somewhat higher for selective COX‐2 inhibitors than for traditional NSAIDs.

Authors' conclusions

Based on the studies carried out so far, the efficacy of aspirin, steroid and NSAIDs (traditional NSAIDs and COX‐2 inhibitors) is not proven. Therefore, these drugs cannot be recommended for the treatment of AD.

Keywords: Aged; Aged, 80 and over; Humans; Alzheimer Disease; Alzheimer Disease/drug therapy; Alzheimer Disease/etiology; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents/adverse effects; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents/therapeutic use; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal/adverse effects; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal/therapeutic use; Aspirin; Aspirin/adverse effects; Aspirin/therapeutic use; Cyclooxygenase 2 Inhibitors; Cyclooxygenase 2 Inhibitors/adverse effects; Cyclooxygenase 2 Inhibitors/therapeutic use; Glucocorticoids; Glucocorticoids/adverse effects; Glucocorticoids/therapeutic use; Inflammation; Inflammation/complications; Inflammation/drug therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Treatment Outcome

Plain language summary

Aspirin, steroid and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs use for treating Alzheimer's disease

Inflammation may play an important role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. There is also some evidence from community surveys that people receiving anti‐inflammatory drugs for various medical conditions may be less likely to develop Alzheimer's disease. Fourteen studies met our inclusion criteria for this review and none of the exclusion criteria. Aspirin, steroid and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (traditional and the selective cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) inhibitors) showed no significant benefit in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Therefore, the use of these drugs cannot be recommended for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease.

Background

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia, and its incidence increases exponentially with age. AD affects 1‐2% of people aged 65‐70 and approximately 20% of those over 80 years (Jorm 2003). It results in a progressive deterioration of intellect, memory and personality. AD is an important health problem that has a significant impact on national economies. In the United States, there are approximately 5.2 million AD patients and the cost of care for an average patient is about 24,500 dollars per year (Wimo 2005). By 2030, an estimated 7.7 million Americans aged 65 and older will have AD (Hebert 2003). The disease is increasing worldwide.

The exact mechanism underlying the pathogenesis of AD is still unclear and remains a topic of intense debate. However, two hypotheses revolving around amyloid and inflammation have been particularly influential in trying to understand the neuropathological processes underlying AD. Beta amyloid (AB) is a proteolytic fragment of 40‐42 residues derived from Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP). In vitro, the longer AB‐42 fragment aggregates much more readily, and is hypothesised to be the main pathological agent in the pathogenesis of AD ( Joachim 1992; Selkoe 1991; Younkin 1995). Altered production, aggregation and deposition of AB may play a critical role in the development of AD (Citron 1992; Haass 1994). Significantly, it is suspected that this deposition of amyloid may directly contribute to the inflammatory environment seen (Ruan 2009; Salminen 2009). The inflammatory hypothesis of AD proposes that specific inflammatory mechanisms, including the cytokine‐driven acute‐phase response, complement activation and microglial activation, contribute to neurodegeneration (Aisen 1994; McGeer 1989). In addition, AD may be associated with loss of the capacity to control inflammation in the brain (Bazan 2009).

In view of the strong association between inflammation and AD, attempts have been made to assess whether anti‐inflammatory pharmaceutical agents may have a role in the management of AD. An important mechanism of attenuating inflammatory processes can be achieved through inhibition of the activity of the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX) which is critical to the production of prostaglandins (Fiebich 1997). This inhibition can occur through the use of various non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) which might thereby diminish the inflammatory response in degenerative dementias. There is evidence that the enzyme cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) might be involved in neurodegenerative mechanisms in AD (Ho 1999; Pasinetti 1998). This has given rise to the hypothesis that drugs which inhibit COX‐2 in the brain, including certain steroids, aspirin, traditional non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAIDs) and selective COX‐2 inhibitors could possibly slow the rate of progression or alleviate the symptoms of AD. Likewise, it has also been suspected that corticosteroids (namely synthetic glucocorticoids) may offer some neuroprotection in AD patients (Aisen 1998) through their well characterised anti‐inflammatory action.

Anti‐inflammatory medications such as non‐selective and selective NSAIDs and corticosteroids have been the subject of epidemiological (Launer 2003) and clinical research in AD. The possibility of benefit from non‐selective COX inhibitors (such as indomethacin, naproxen, ibuprofen and diclofenac) and/or selective COX‐2 inhibitors (such as celecoxib and meloxicam) is supported by several lines of evidence. Less work has been carried out for corticosteroids such as prednisolone, but their potential usefulness is of interest.

Epidemiological studies have found a lower prevalence of dementia in people who have regularly taken NSAIDs, usually for rheumatological disorders (McGeer 1996, Stewart 1997). There has also been a cohort study reporting a lower incidence of AD in users of NSAIDs than in non‐users (In't Veld 2001). There is in vitro evidence that, independently of their inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis, some NSAIDs can directly influence the processing of amyloid precursor protein (APP) which is thought to be implicated in the pathogenesis of AD (Avramovich 2002; Blasko 2001). Likewise, an open‐label pilot study of low‐dose prednisolone showed the suppression of peripheral markers of the acute phase response and complement activation in AD without systemic toxicity (Aisen 1996).

In recent years attempts have been made to determine whether anti‐inflammatory agents may be efficacious in the treatment of AD. The purpose of this review is to establish the effectiveness, or otherwise, of such medication. It is now known that all anti‐inflammatory drugs, including selective COX‐2 inhibitors, can carry significant side effects profile and may occasionally be fatal. Hence, it is now important to ascertain whether there is a place for these drugs in the treatment of AD.

Objectives

To systematically review the evidence examining the efficacy and side effects of aspirin, steroidal and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs in the treatment of AD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials assessing the efficacy of aspirin, steroidal and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs in the treatment of AD.

Types of participants

Patients of any age diagnosed with probable AD according to internationally recognised criteria including the 'National Institute of Neurologic and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS‐ADRDA), the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and the World Health Organisation classification of mental and behavioural disorders (ICD‐10) (APA 1995; McKhann 1984; WHO 1992) .

Types of interventions

Aspirin, steroidal and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory agents (traditional and selective COX‐2 inhibitors) at any dose.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Cognition (using objective psychometric rating instruments, e.g. the Alzheimer's disease assessment scale ‐ cognitive sub‐scale or ADAS‐COG) or Mini‐Mental Status Examination (MMSE)

Adverse events

Death

Secondary outcome

Clinical global impression of change

Mood/depression

Behavioural disturbance

Activities of daily living

Quality of life

Caregiver burden

Institutionalization

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched ALOIS (www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/alois) ‐ the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group’s Specialized Register on 12 April 2011. The search terms used were: aspirin OR "cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor" OR aceclofenac OR acemetacin OR betamethasone OR celecoxib OR cortisone OR deflazacort OR dexamethasone OR dexibruprofen OR dexketoprofen OR diclofenac sodium OR diflunisal OR diflusinal OR etodolac OR etoricoxib OR fenbufen OR fenoprofen OR flurbiprofen OR hydrocortisone OR ibuprofen OR indometacin OR indomethacin OR ketoprofen OR lumiracoxib OR mefenamic OR meloxicam OR methylprednisolone OR nabumetone OR naproxen OR nimesulide OR "anti‐inflammatory" OR prednisone OR piroxicam OR sulindac OR tenoxicam OR tiaprofenic acid OR triamcinolone OR NSAIDS OR NSAID.

ALOIS is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator for the Cochrane Dementia Group and contains studies in the areas of dementia prevention, dementia treatment and cognitive enhancement in healthy. The studies are identified from:

Monthly searches of a number of major healthcare databases: Medline, Embase, Cinahl, Psycinfo and Lilacs

Monthly searches of a number of trial registers: ISRCTN; UMIN (Japan's Trial Register); the WHO portal (which covers ClinicalTrials.gov; ISRCTN; the Chinese Clinical Trials Register; the German Clinical Trials Register; the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials and the Netherlands National Trials Register, plus others)

Quarterly search of The Cochrane Library’s Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Six‐monthly searches of a number of grey literature sources: ISI Web of Knowledge Conference Proceedings; Index to Theses; Australasian Digital Theses

To view a list of all sources searched for ALOIS see About ALOIS on the ALOIS website.

Details of the search strategies used for the retrieval of reports of trials from the healthcare databases, CENTRAL and conference proceedings can be viewed in the ‘methods used in reviews’ section within the editorial information about the Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group.

Additional searches were performed in many of the sources listed above to cover the timeframe from the last searches performed for ALOIS to ensure that the search for the review was as up‐to‐date and as comprehensive as possible. The search strategies used can be seen in Appendix 1.

Details of the initial search carried out for this review can be viewed in Appendix 2.

The latest search (April 2011) retrieved a total of 1223 results. After a first‐assess and a de‐duplication of these results the authors were left with 116 references/records to further assess.

Searching other resources

The first authors of important identified RCTs that were potentially suitable for inclusion were contacted to request additional information on related new, unpublished, or in press studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two authors (DJ, MI) independently examined the titles and abstracts of the trials identified in the search and considered them for inclusion according to the pre‐determined eligibility criteria. Any disparity was resolved by retrieval of the cited articles and further discussion with the third author (NT).

Data extraction and management

A double‐check process was used for risk of bias and outcome data including clinical outcomes and side effects. As mentioned, there were 14 included studies with 15 interventions as one study was comprised two interventions. Initially, the first author (DJ) extracted the data on all 14 included studies (15 interventions) and this was followed by verification by the other two authors (MI and NT). All authors had a data extraction form for this process. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion between DJ and the other author involved (either MI or NT depending on the study in question).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The quality of the methods used in each study was examined by the two reviewers using the domain‐based evaluation as shown in Table 1. In conclusion, risk of bias are summarised for each study as described in Table 2. The Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group (GRADE Working Group) approach was used to define the quality of data presented in this systematic review. The GRADE approach specifies four levels of quality as shown in Table 3.

1. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias.

| Domain | Description | Review authors’ judgment |

| Sequence generation. | Describe the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups. | Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? |

| Allocation concealment. | Describe the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to determine whether intervention allocations could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, enrolment. | Was allocation adequately concealed? |

| Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessorsAssessments should be made for each main outcome (or class of outcomes). | Describe all measures used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. Provide any information relating to whether the intended blinding was effective. | Was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the study? |

| Incomplete outcome dataAssessments should be made for each main outcome (or class of outcomes). | Describe the completeness of outcome data for each main outcome, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. State whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers in each intervention group (compared with total randomised participants), reasons for attrition/exclusions where reported, and any re‐inclusions in analyses performed by the review authors. | Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed? |

| Selective outcome reporting. | State how the possibility of selective outcome reporting was examined by the review authors, and what was found. | Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting? |

| Other sources of bias. | State any important concerns about bias not addressed in the other domains in the tool. If particular questions/entries were pre‐specified in the review’s protocol, responses should be provided for each question/entry. |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias? |

2. Risk of bias within a study and across studies.

| Risk of bias | Interpretation | Within a study | Across studies |

| Low risk of bias. | Plausible bias unlikely to seriously alter the results. | Low risk of bias for all key domains. | Most information is from studies at low risk of bias. |

| Unclear risk of bias. | Plausible bias that raises some doubt about the results. | Unclear risk of bias for one or more key domains. | Most information is from studies at low or unclear risk of bias. |

| High risk of bias. | Plausible bias that seriously weakens confidence in the results. | High risk of bias for one or more key domains. | The proportion of information from studies at high risk of bias is sufficient to affect the interpretation of results. |

3. Levels of quality of a body of evidence in the GRADE approach for RCT.

| Underlying methodology | Quality rating | |||

| Randomised trials | High | |||

| Downgraded randomised trials | Moderate | |||

| Double‐downgraded randomised trials | Low | |||

| Triple‐downgraded randomised trials | Very low |

Measures of treatment effect

The data presented in this review included dichotomous and continuous data. In dichotomous data (side effects, institutionalisation and death), each individual outcome comprised two possible categorical responses. Continuous data included the rest of clinical outcomes which were presented in a numerical quantity as a score format.

For dichotomous outcome, we used risk ratio (relative risk) to compare intervention and placebo. Risk ratio describes the probability with which side effects, institutionalisation and death will occur in the intervention group compared to placebo. In addition to risk ratio, 95% confidence interval was also calculated to determine the range of the effect.

For continuous data, we used both the mean difference (MD) and the standardized mean difference (SMD).

Mean difference was used for all outcomes that used the same scale. If an outcome was measured using more than one scale, then we calculated a standardised mean difference (SMD) where

SMD = Difference in mean outcome between group

SD of outcome among participants

Heterogeneity may exist among studies in a meta‐analysis and whenever possible the causes of the heterogeneity need to be explored. One way of exploring this is to carry out a subgroup analysis. However, this approach is problematic when there are very few included studies in each meta‐analysis which is the case in this review Another approach to address the potential consequences of heterogeneity is to use the random‐effects meta‐analysis (Cochrane Handbook). In this review, and in line with current guidelines, I2 was used to quantify inconsistency across studies which then move the focus away from testing whether heterogeneity is present to assessing its impact on the meta‐analysis (Cochrane Handbook). Here, the intention was to use I2 level of >30% (this is a conservative estimate and was preferred to 40%) as an indicator of potential heterogeneity. Hence, for I2<30%, the fixed‐effects meta‐analysis method was determined to be appropriate. For I2>30% the random‐effects meta‐analysis method would be more fitting. This division is not ideal but is in line with current guidelines and does represent an effort to deal with the possible effects of heterogeneity on meta‐analysis results.

Unit of analysis issues

In this review only Aisen 2003a had two active interventions: a traditional NSAIDs and a selective COX‐2 inhibitor group. The approach to overcome a potential unit‐of‐analysis error for such a study which included multiple groups but with clear separation of subgroups was to “split” the shared group (the placebo group) into two subgroups each with a smaller sample size.

Dealing with missing data

Missing data could be a source of bias and affect the validity of the study. For considered studies with potential missing data, the authors were contacted to request more information.

In studies where the SD for continuous outcomes was missing, then SD was calculated from available P value.

For included studies with high risk of bias because of missing data, a sensitivity analyses was conducted to take into account the high bias risk. This was applied to studies with both dichotomous and continuous outcome data.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

For this review, interventions were grouped according to the established and accepted classification of the different groups of drugs studied (aspirin, steroid and NSAIDs). As aspirin, steroid and NSAID drugs differed significantly in chemical structure and mode of action, overall analyses under "anti‐inflammatory drugs" would not have been useful. Therefore, separate analyses were needed to differentiate between the potential efficacy and adverse events of these three groups of drugs. As far as the NSAID drugs are concerned, a subgroup analysis was justified to differentiate between the traditional NSAIDs and selective COX‐2 inhibitors subgroups. In essence, they were similar enough to be included as one group in the initial analysis and different enough to justify a further subgroup analyses. Hence, analyses undertaken included: aspirin VS Placebo; steroids VS Placebo; NSAIDs VS Placebo, then traditional NSAIDs VS Placebo and selective COX‐2 inhibitors VS Placebo.

Heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic which was interpreted as follows:

0%‐40%: might not be important

30%‐60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity

50%‐90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity

70%‐100%: considerable heterogeneity

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

604 references were retrieved by the electronic searches, from which 14 relevant RCTs were selected. Kappa statistic for agreement among 2 authors was 0.793 as shown in Appendix 3 which implied excellent agreement.

Included studies

From 15 interventions (14 studies in total), there were three interventions for aspirin, one for steroids, six for traditional NSAIDs and five interventions for selective COX‐2 inhibitors. One study had two interventions including both a traditional NSAIDs and a selective COX‐2 inhibitor (Aisen 2003a). The 14 selected studies enrolled a total of 2445 AD patients. The characteristics of participants in each study are presented in Table 4.

4. Characteristics of participants from each study.

| Study | Mean age (SD) | Female (%) | year of education (SD) | Duration of disease, yr (SD) | ApoE (% >/=1allele) | MMSE (SD) | Hypertension (%) |

| Bentham 2008 (Aspirin, N=156) |

75 | 63 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 19 | 19 |

| Zhou 2004a (Aspirin, N=13) |

71.1 (10.6) | 57.14 | N/A | 2.65 (3.15) | N/A | 14.65 (5.93) | N/A |

| Zhou 2004 (Aspirin, N=8) |

69.5 (9.8) | 37.50 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 14.5 (6.8) | N/A |

| Aisen 2000 (Prednisone, N=69) |

73.4 (7.2) | 49.3 | 14.1 (3) | 3.5 (2.4) | 65.6 | 21.2 (4.4) | N/A |

| Aisen 2002 (Nimesulide, N=21) |

73(2) | 38.09 | 13.1 (11.2) | 2 (0.5) | N/A | 21.1 (1.1) | N/A |

| Aisen 2003 (Naproxen, N=118) |

74.1 (7.8) | 48.3 | 13.8 (3.2) | 4.1 (2.3) | 70.4 | 20.7 (3.6) | N/A |

| Aisen 2003 (Rofecoxib, N=122) |

73.7 (7.2) | 54.9 | 13.8 (3.2) | 4.1 (2.3) | 68.1 | 21.2 (3.8) | N/A |

| de Jong 2008 (Indomethacin, N=26) | 72.7 (6.9) | 53.85 | 2.4 (1.3) | 2.74 (1.75) | 50 | 19.1 (4.1) | N/A |

| Pasqualetti 2009 (Ibuprofen, N=66) | 73.7 (7.3) | 61 | 7.4 (3.7) | 2 (0.5‐5.41) | 20.4 | 19.7 (3.0) | N/A |

| Rogers 1993 (Indoethacin, N=14) |

78 (2) | 35.71 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Hull 1999 (Piroxicam, N=6) |

range of 55‐75 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Scharf 1999 (Diclofenac, N=12) |

71.8 (2.3) | 66.67 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 18.5 (0.99) |

| Jhee 2004 (Celecoxib, N=15) | 71.17 | 26.67 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Reines 2004 (Rofecoxib, N=346) |

76 (8) | 54 | N/A | 2.17 (1.83) | N/A | N/A | 21 (4) |

| Soininen 2007 (Celecoxib, N=285) | 73.7 (8.2) | 53 | N/A | 1.37 (1.7) | N/A | 19.8 (4.2) | 31.9 |

Excluded studies

Studies were excluded if they were non‐RCTs, did not include AD patients and did not use one of the drugs under investigation. In total:

529 studies were excluded because they were not RCTs; (Of these 470 studies were excluded at the begining if they were reviews or animal studies, therefore, there were only 59 studies included in the references for the excluded studies)

35 RCTs were excluded because participants were not diagnosed as suffering from AD;

18 RCTs were excluded because the interventions were not aspirin, steroidal or non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs;

6 RCTs were excluded because they were based on the same data used in other included RCTs;

2 RCTs identified from trial registers were excluded because there was no published data and no response from the authors to a request for information.

Flurbiprofen, a traditional NSAID, was included as a search term. Several studies were identified which proved on closer investigation to have used R‐flurbiprofen. This enantiomer has little activity against cyclooxygenase, the target of traditional NSAIDs, and undergoes minimal chiral conversion in humans to the cyclooxygenase‐inhibiting S‐enantiomer. It cannot, therefore, be classed as an NSAID, but has been investigated as a potential modulator of AB‐42 production in AD (Wilcock 2006a). Trials using R‐flurbiprofen were therefore excluded from this review.

Risk of bias in included studies

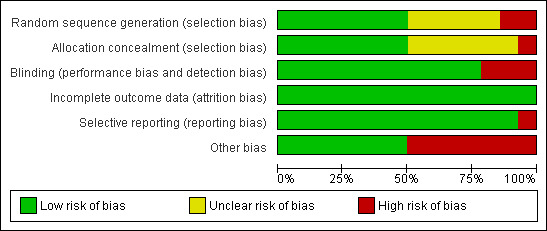

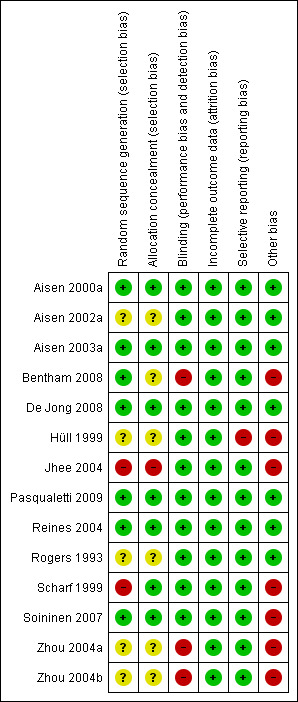

Risk of bias assessment tool was used to assess the validity of each included study. A range from low (five studies) to high (seven studies) was observed. Two studies had unclear risk of bias (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

There were seven included studies that used proper allocation concealment method, while six studies were unclear and only Jhee 2004 did not apply allocation concealment.

Blinding

Eleven included studies properly blinded participants and outcome assessors. The remaining three studies were open‐label studies (Bentham 2008; Zhou 2004a; Zhou 2004b).

Incomplete outcome data

All studies properly addressed the issue of incomplete outcome data and reasons for missing outcome data were unlikely to be related to true outcome.

Selective reporting

Of all included studies, only Hüll 1999 did not report all stated outcomes. In this particular study the data was presented in an abstract form and no full text article was available. This could have resulted from negative findings or no measurement for these outcomes. This may represent a selective reporting bias.

Effects of interventions

Aspirin

All three selected studies (Bentham 2008; Zhou 2004a; Zhou 2004b) were open‐label and unsuitable for meta‐analysis due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity. Total numbers of participants from both Zhou 2004a and Zhou 2004b were 42, compared to 310 in Bentham 2008. Bentham 2008, Zhou 2004b and Zhou 2004a had different follow up time length which was 3 years, 36 weeks and 6 months respectively. Further, most patients (75%) in Bentham 2008 study took donepezil in the control group, while patients from Zhou 2004a and Zhou 2004b took hyperzine and nigocerline. All three studies also used different doses of aspirin, namely 75 mg, 150 mg and 50 mg per day.

In addition, an issue of lacking and missing data should be taken into account as neither Zhou 2004 nor Zhou 2004a provided data on side effects and detailed data on cognitive improvements. For example, there was no specific p‐value or mean difference shown in the studies.

None of these studies reported significant cognitive improvement in the group treated with aspirin.

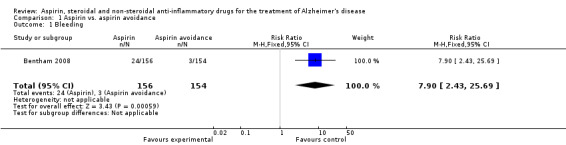

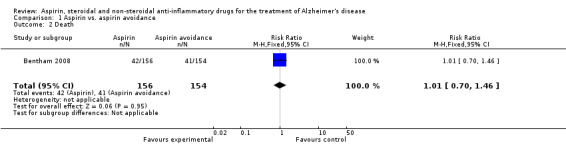

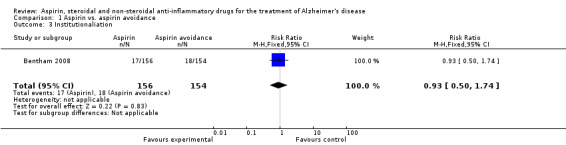

However, Bentham 2008 showed significant bleedings from various sites (RR 7.90, 95% CI 2.43 to 25.69; Analysis 1.1), but there was no difference in terms of death (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.46; Analysis 1.2) and institutionalisation rate (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.74; Analysis 1.3), compared to aspirin avoidance group.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Aspirin vs. aspirin avoidance, Outcome 1 Bleeding.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Aspirin vs. aspirin avoidance, Outcome 2 Death.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Aspirin vs. aspirin avoidance, Outcome 3 Institutionaliation.

Steroid

Only one selected study assessed a steroidal anti‐inflammatory agent, prednisone (Aisen 2000a).This study was classified as being at low risk of bias. A total of 138 subjects with probable AD were randomised to either the drug or the placebo groups. This was a double‐blind two‐group parallel design comparing prednisone treatment with placebo. The primary outcome measure for this trial was the 1‐year change in the cognitive subscale of the AD Assessment Scale (ADAS‐cog) score.

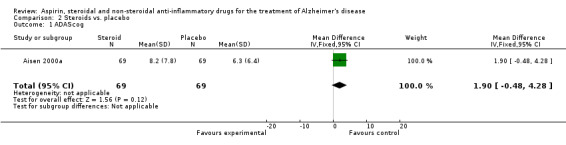

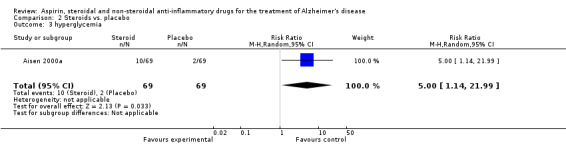

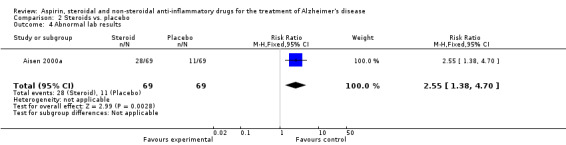

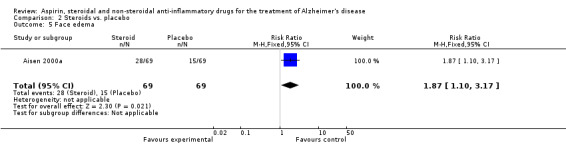

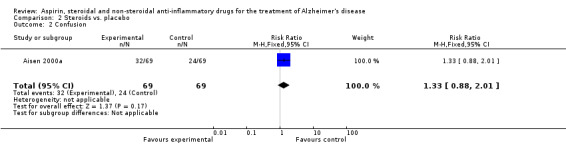

No significant effect on cognition or mood at 12 months was observed (Analysis 2.1). Prednisone was associated with hyperglycaemia (RR 5.00, 95% CI 1.14 to 21.99; Analysis 2.3), abnormal lab results (RR 2.55, 95% CI 1.38 to 4.70; Analysis 2.4) and face edema (RR 1.87, 95% CI 1.10 to 3.17; Analysis 2.5).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Steroids vs. placebo, Outcome 1 ADAScog.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Steroids vs. placebo, Outcome 3 hyperglycemia.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Steroids vs. placebo, Outcome 4 Abnormal lab results.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Steroids vs. placebo, Outcome 5 Face edema.

NSAIDs

Ten studies investigated NSAIDs in AD. There were eleven interventions: six traditional NSAIDs and five selective COX‐2 inhibitors. Analysis was initially undertaken on the NSAIDs group as a whole (all 11 interventions). Subsequently, subgroup analysis was carried out to establish whether any difference existed between traditional NSAIDs and selective COX‐2 inhibitors.

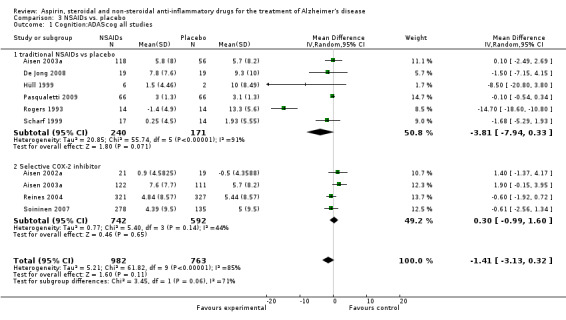

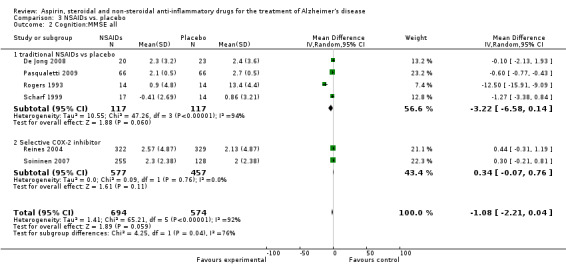

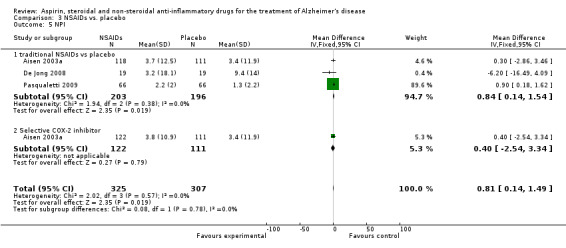

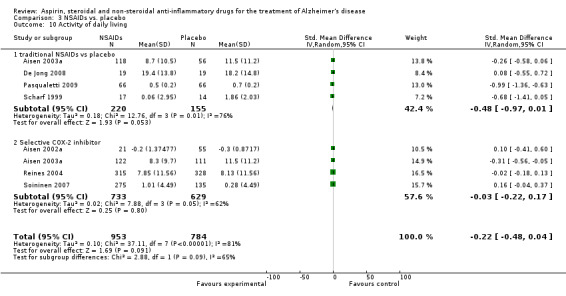

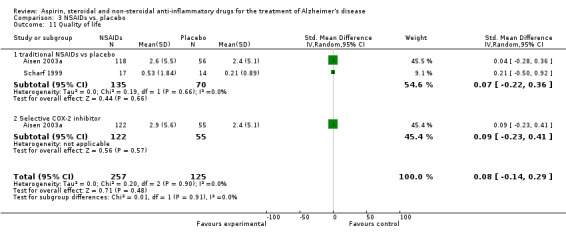

All NSAIDs interventions used ADAS‐cog scores as an outcome measure, but there was not enough data from Jhee 2004 to perform an analysis. In these studies, which included 1745 participants, the meta‐analysis showed no significant difference between the scores of the treatment and placebo groups (MD ‐1.41, 95% CI ‐3.13 to 0.32; Analysis 3.1). Six studies involving 1268 participants also used the MMSE as an outcome measure (De Jong 2008; Pasqualetti 2009; Reines 2004; Rogers 1993; Scharf 1999; Soininen 2007). These studies showed no significant change in rate of MMSE scores decline in the treatment group (MD ‐1.08, 95%CI ‐2.21 to 0.12; Analysis 3.2).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 1 Cognition:ADAScog all studies.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 2 Cognition:MMSE all.

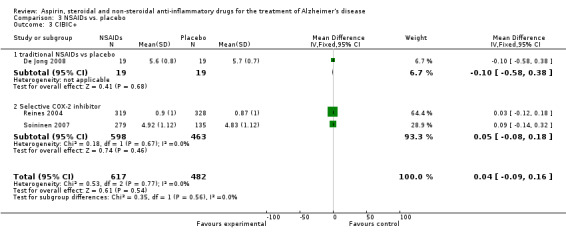

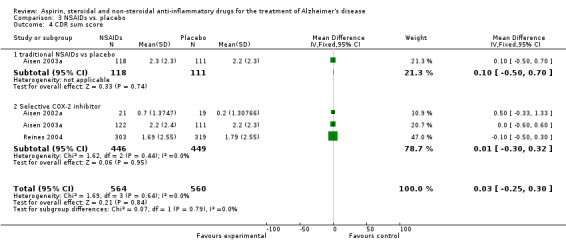

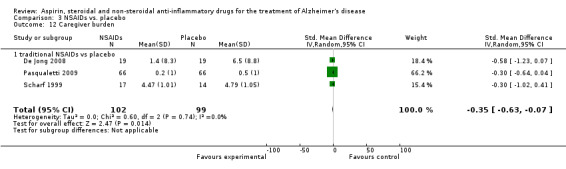

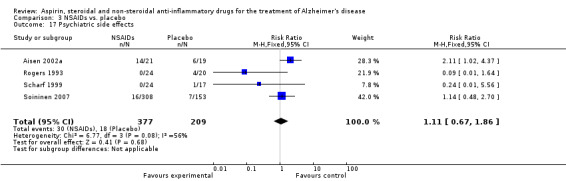

In the subgroup analyses, no significant difference in the rate of cognitive decline overall was observed in the traditional NSAIDs group for ADAScog (MD ‐3.81, 95% CI ‐7.94 to 0.33; Analysis 3.1) and MMSE scores (MD ‐3.22, 95% CI ‐6.58 to 0.14; Analysis 3.2). Similarly, for the selective COX‐2 inhibitors studies, no overall significant change was reported for both ADAScog (MD 0.30, 95% CI ‐0.99 to 1.60; Analysis 3.1) and MMSE scores (MD 0.34, 95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.76; Analysis 3.2). For all NSAIDs, no significant improvement was obtained for Clinician's Interview‐Based Impression of Change (CIBIC+) (MD 0.04; 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.16: Analysis 3.3). The same also applied for the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes (CDR‐SOB), neuropsychiatric inventory (NPI) and other measures where no significant differences between the treatment and the placebo groups were observed (Analysis 3.4 to Analysis 3.12).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 3 CIBIC+.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 4 CDR sum score.

3.12. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 12 Caregiver burden.

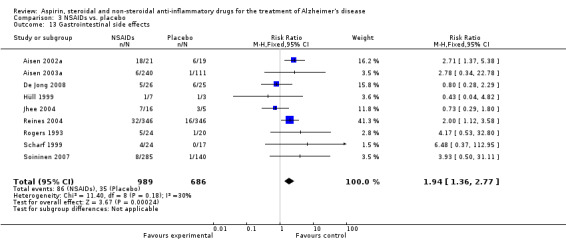

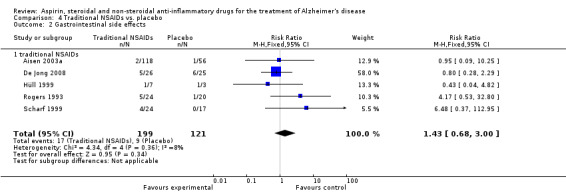

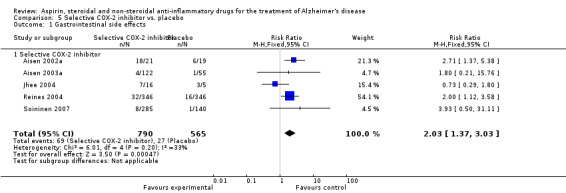

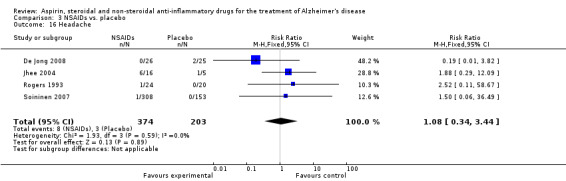

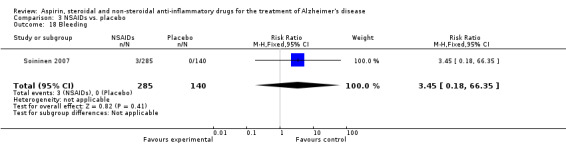

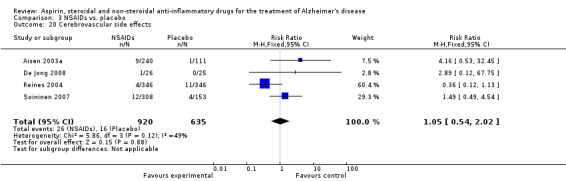

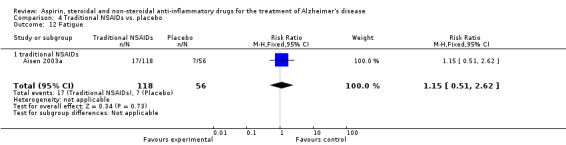

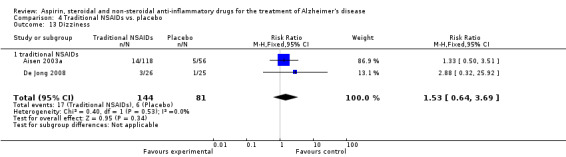

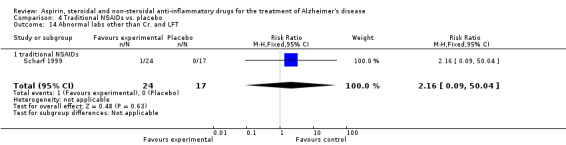

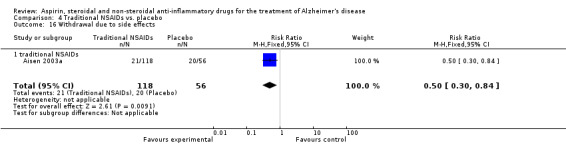

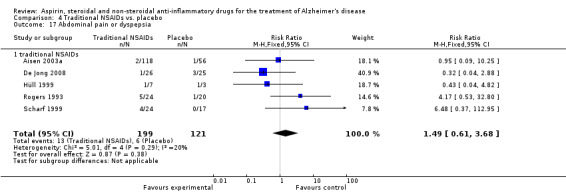

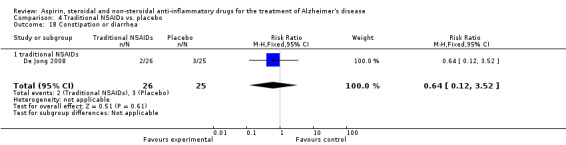

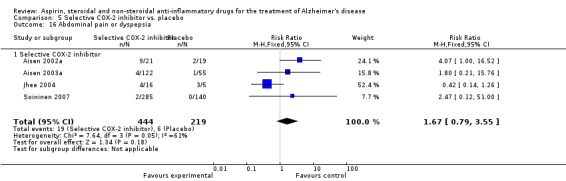

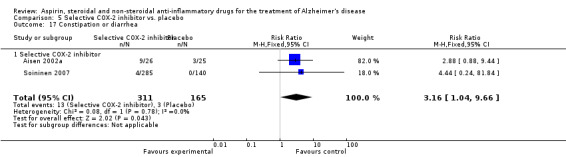

Gastrointestinal side effects were more common in the NSAIDs group (RR 1.94, 95% CI 1.36 to 2.77; Analysis 3.13) compared to placebo based on analysis of data from 1675 participants in 9 studies. Both traditional NSAIDs and selective COX‐2 inhibitors had higher rate of gastrointestinal side effects (RR 1.43, 95% CI 0.68 to 3.00 and RR 2.03, 95% CI 1.37 to 3.03; from Analysis 4.2 and Analysis 5.1, respectively).

3.13. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 13 Gastrointestinal side effects.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Traditional NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 2 Gastrointestinal side effects.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Selective COX‐2 inhibitor vs. placebo, Outcome 1 Gastrointestinal side effects.

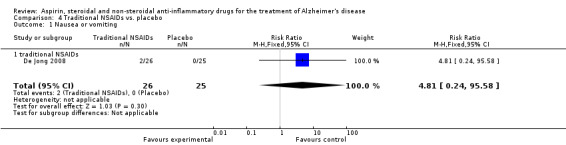

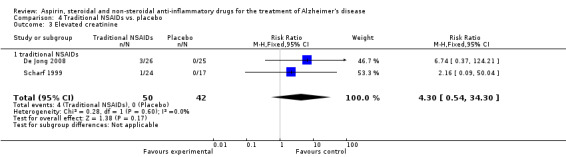

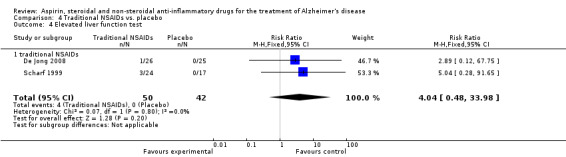

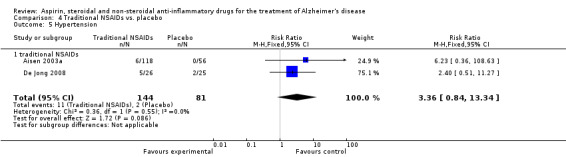

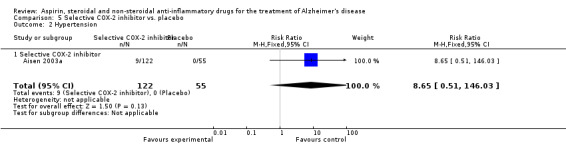

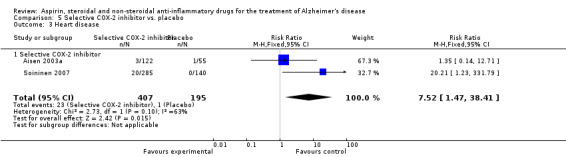

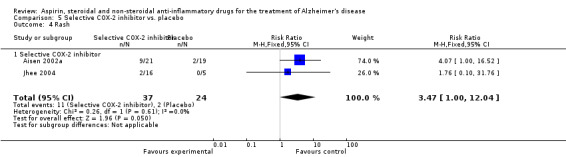

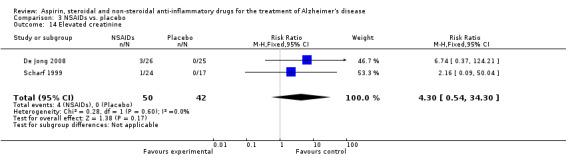

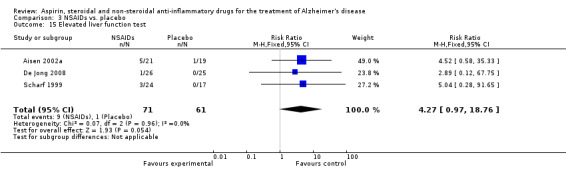

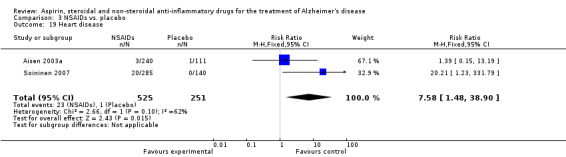

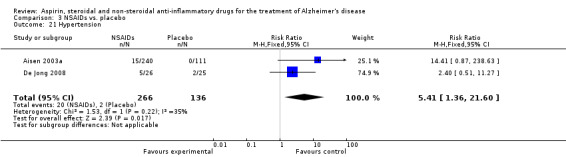

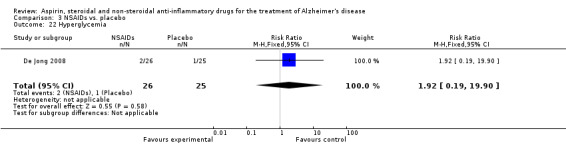

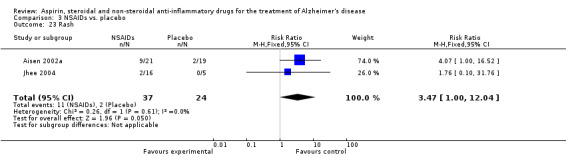

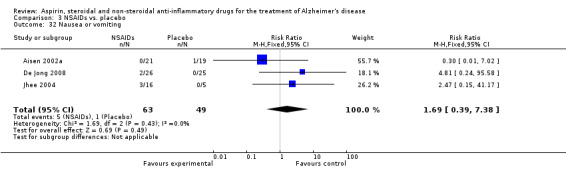

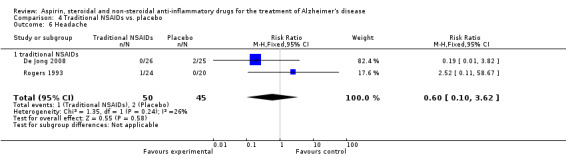

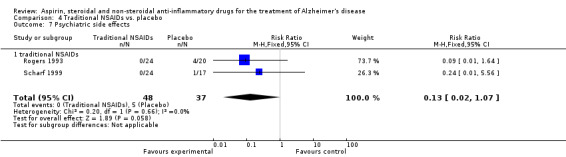

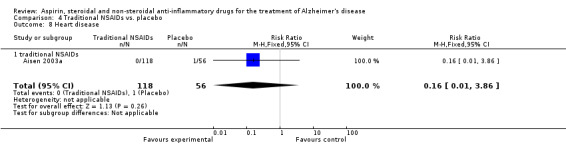

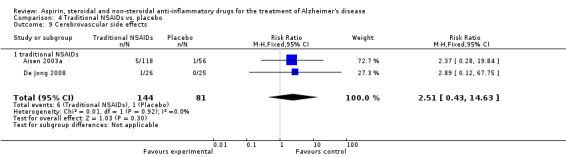

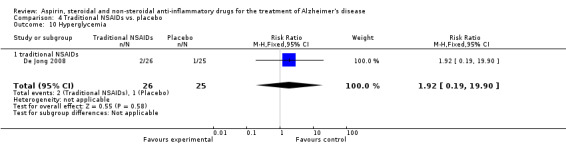

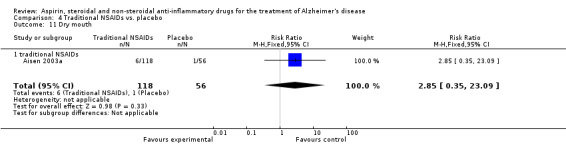

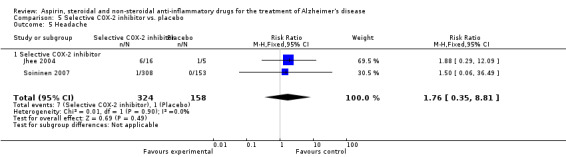

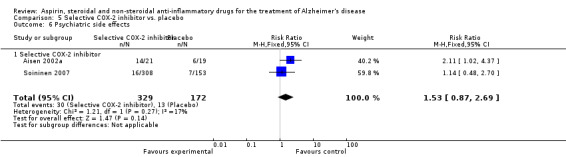

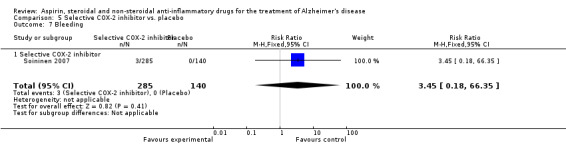

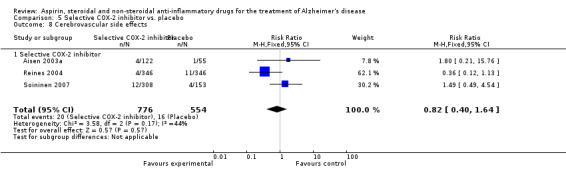

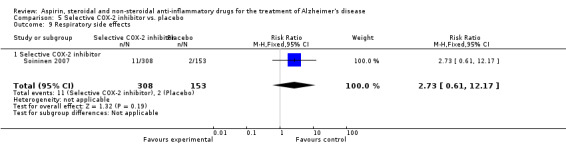

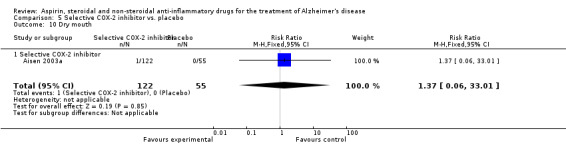

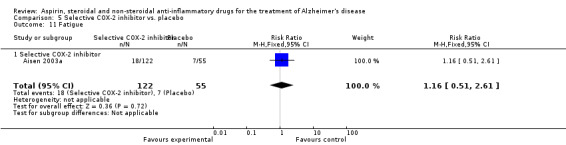

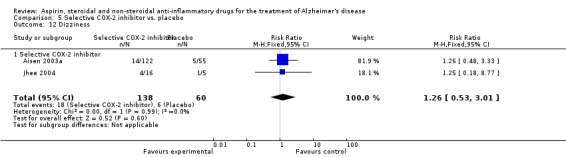

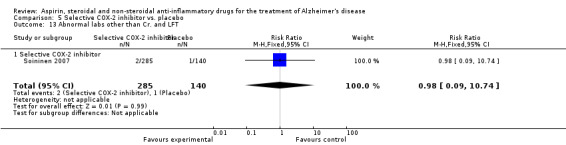

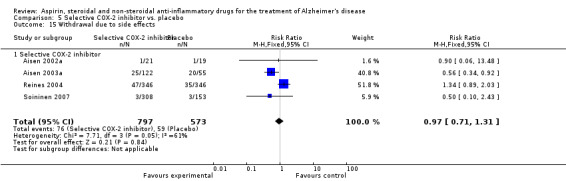

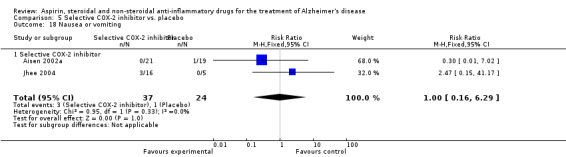

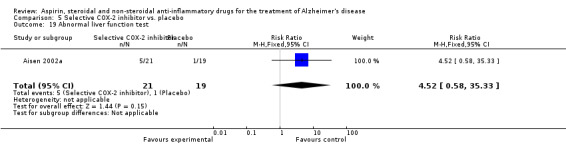

For traditional NSAIDs, common side effects compared to placebo included nausea and vomiting (RR 4.81, 95% CI 0.24 to 95.58; Analysis 4.1), elevated creatinine (RR 4.30, 95% CI 0.54 to 34.30; Analysis 4.3), elevated liver function test (RR 4.04, 95% CI 0.48 to 33.98; Analysis 4.4), and hypertension (RR 3.36, 95% CI 0.84 to 13.34; Analysis 4.5). For selective COX‐2 inhibitors, common side effects compared to placebo included hypertension (RR 8.65, 95% CI 0.51 to 146.03; Analysis 5.2), heart disease (RR 7.52, 95% CI 1.47 to 38.41; Analysis 5.3), and rash (RR 3.47, 95% CI 1.00 to 12.04; Analysis 5.4). The hypertension results came from only 229 participants in Aisen 2003b resulting from the use of rofecoxib. For cardiac side effects, subgroup analysis was performed for rofecoxib and celecoxib separately. There was no direct comparison between the two products. The result showed that celecoxib caused significant heart problems in AD (RR 20.21, 95% CI 1.23 to 331.79; Analysis 5.3), while rofecoxib did not (RR 2.73, 95% CI 0.29 to 25.86; Analysis 5.3).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Traditional NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 1 Nausea or vomiting.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Traditional NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 3 Elevated creatinine.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Traditional NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 4 Elevated liver function test.

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Traditional NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 5 Hypertension.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Selective COX‐2 inhibitor vs. placebo, Outcome 2 Hypertension.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Selective COX‐2 inhibitor vs. placebo, Outcome 3 Heart disease.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Selective COX‐2 inhibitor vs. placebo, Outcome 4 Rash.

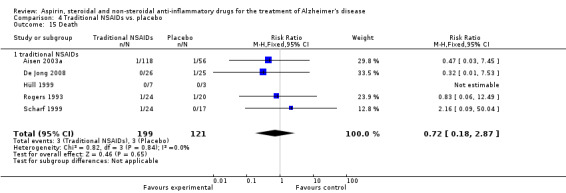

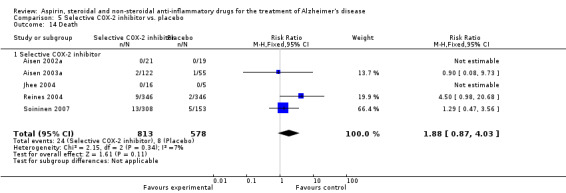

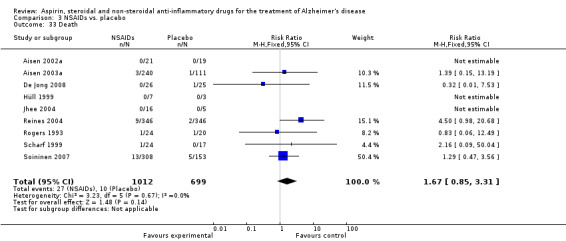

Death rate was higher in the NSAIDs group although this did not reach statistical significant (RR 1.67, 95% CI 0.85 to 3.31; Analysis 3.3). Death rate for traditional NSAIDs (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.18 to 2.87; Analysis 4.15) and selective COX‐2 inhibitor groups (RR 1.88, 95% CI 0.87 to 4.07; Analysis 5.14). Data presented in this meta‐analysis was from 1711 participants from 9 included studies.

4.15. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Traditional NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 15 Death.

5.14. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Selective COX‐2 inhibitor vs. placebo, Outcome 14 Death.

Discussion

Aspirin, steroids and NSAIDs (traditional NSAIDs and selective COX‐2 inhibitors) do not slow down the decline in cognitive function in AD patients and do not improve non‐cognitive and behavioural outcome measures such as depression, behavioral disturbance, activity of daily living, quality of life, clinical global impression of change and caregiver burden.

All anti‐inflammatory agents are known to be associated with a host of side effects. In the selected studies aspirin significantly increased bleeding in AD patients. Steroid medication was associated with hyperglycaemia, abnormal laboratory parameters, and face edema. Traditional NSAIDs were associated with nausea, vomiting, elevated creatinine, elevated liver function tests, and hypertension. Selective COX‐2 inhibitors were associated with hypertension, heart problems, and rash. Celecoxib tended to cause higher rate of heart problems compared to rofecoxib, however the baseline characteristic of celecoxib group had significantly higher rate of hypertension, diabetes and higher numbers of bypass patients. Gastrointestinal side effects were commonly found in both traditional NSAIDs and Selective COX‐2 inhibitors. Significantly, death rate was higher in selective COX‐2 inhibitors, compared to traditional NSAIDs. Meta‐analysis of side effects that included more than 1000 participants included gastrointestinal, cerebrovascular and other side effects as well as death.

There is a wealth of epidemiological data supporting a role for anti‐inflammatory treatment in the protection against the development of cognitive dysfunction. In addition, a role for inflammatory processes in the pathogenesis of AD is now widely recognised. Nevertheless, such data has not been translated into clinical benefit to patients with AD. Anti‐inflammatory drugs do not seem, based on current evidence, to achieve any noticeable improvement in any of the various outcomes assessed, and foremost among them cognitive measures. It cannot be discounted that most, in fact all of the studies assessing the efficacy of anti‐inflammatory agents have been for a relatively short duration not usually exceeding 12 months. Further, patients selected are likely to have well established disease. It is accepted that the disease pathological process begins many years before the start of any symptoms associated with AD. Hence, one cannot comment on any potential efficacy for anti‐inflammatories such as NSAIDs in those with very early stages of asymptomatic and silent disease. In fact epidemiological studies showing a benefit for anti‐inflammatories has tended to assess patients with mainly rheumatological disorders on long term treatment with anti‐inflammatory drugs. This may explain the discrepancy between the widely observed data from epidemiological studies and RCTs.

It is tempting to speculate whether a potential difference may exist between traditional NSAIDs and selective COX‐2 inhibitors. It remains unclear whether this may relate to mechanism of action beyond COX‐2 inhibition. In recent years more interest has been directed at selective COX‐2 inhibitors, in part, due to the earlier perceived supremacy of this class of NSAIDs when it comes to side effects. In recent years, however, the benefit/risk profile of these drugs has been evaluated and earlier enthusiasm about their use has been critically reassessed. It will be of benefit that future work continues to include traditional NSAIDs as well as the newer COX‐2 inhibitors.

Summary of main results

Aspirin, steroid and NSAIDs (traditional NSAIDs and selective COX‐2 inhibitors) do not slow down cognitive decline in AD patients. They also do not improve behavioural and all other non‐cognitive outcome measures such as depression, behavioral disturbance, activity of daily living, quality of life, clinical global impression of change and caregiver burden.

All anti‐inflammatory agents are known to be associated with a host of side effects. In the selected studies aspirin significantly increased bleeding in AD patients. Steroid medication was associated with hyperglycaemia, abnormal laboratory parameters, and face edema.Traditional NSAIDs were associated with nausea, vomiting, elevated creatinine, elevated liver function tests, and hypertension. Selective COX‐2 inhibitors were associated with hypertension, heart problems and rash. Death rate was higher in selective COX‐2 inhibitors, compared to traditional NSAIDs.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

All patients in this review were diagnosed as having probable AD by NINCDS‐ADRDA criteria or DSM 4. MMSE ranged from 10‐26; hence patients in these studies had mild to moderate disease. Most recruitment took place in out‐patient settings, except for two studies that were conducted in in‐patient settings (42 participants) (Zhou 2004b; Zhou 2004a) and one study (Hüll 1999) in both out‐patient and in‐patient settings (10 participants). Minimum participants’ age was 46 years. The studies were conducted in different countries including USA, UK, Netherlands, Australia, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Italy and China. Interventions included Aspirin, Steriods and NSAIDs.

Quality of the evidence

The three aspirin studies were rated ‘moderate’ in quality as they were not double‐blind randomised controlled trials. The steroid study had low risk of bias and high quality rating. For NSAIDs, high rating for quality was obtained for four studies (Aisen 2003a; De Jong 2008; Pasqualetti 2009; Reines 2004). Moderate rating for quality was for three studies (Aisen 2002a; Rogers 1993; Soininen 2007) while low rating for quality was achieved by another three studies (Hüll 1999; Jhee 2004; Scharf 1999).

Potential biases in the review process

There were 2 studies by Beck 2000 and Taylor 1999 that met all inclusion criteria, but data could not be retrieved and the authors could not be contacted. Inability to include this unpublished data could have led to publication bias as the articles might not be published due to the nature and direction of the results. However, for this review thorough search of multiple databases was performed and is expected to have identified all registered trials and possible unpublished articles.

Duplicate publication bias

There were 15 studies in this review that were found to be repetitive or overlapped substantially with the included studies. It was crucial to identify all redundant and multiple publication as it can lead to overestimation of intervention effects.

Location bias

It was found that trials published in low or non‐impact factor journals were more likely to report significant results than those published in high‐impact journals and that the quality of the trials was also associated with the journal of publication. In this systematic review, high risk of bias studies such as Zhou 2004b, Hüll 1999 and Scharf 1999 tended to provided more significant positive outcome toward intervention group than those of low risk.

Language bias

Reviews have often been exclusively based on studies published in English. Although the number of systematic reviews that restricted their search to studies reported in English had been decreased from 72% to 16%, it remained a challenge of the review process. In this review there was no language restriction which resulted in including 2 Chinese language studies. Although no total translation for the two Chinese language studies was done, data was extracted using a translation sheet from Cochrane as shown in Appendix 4. The process was done to help reduce language bias in the review.

Outcome reporting bias

Of all included studies only one Hüll 1999 did not report all stated outcomes. A reason for this may have been because the data was presented in an abstract form. For the remainder of the included studies, at least the stated primary outcomes were reported. For Jhee 2002, the ADAScog was not reported and data could not be retrieved although the author could be contacted. For side effects, Soininen 2007 study only reported side effects where more than 10% of participants complained. Hence, less common side effects were not reported.

Selection bias

In Soininen 2007 study the intervention group included higher number of subjects with pre‐existing hypertension, diabetes and heart bypass. Hence, in this sponsored study the results obtained as far as side effects are concerned need to be interpreted with caution.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Results from cross‐sectional, cohort and case‐control studies tended to be positive toward the use of NSAIDs in AD (Imbimbo 2004; In't Veld 2001; Landi 2003; McGeer 1996; Rich 1995). There was also evidence from a systematic review that people who took NSAIDs had a lower risk of developing AD (Etminan 2003). Theoretically, aspirin, steroid and NSAIDs should be able to decrease inflammatory process (Aisen 1994; Aisen 1996; Aisen 1998; Harris 2002; Ho 1999; McGeer 1989; Pasinetti 1998; Thomas 2001) which in turn would help improve AD.

In this systematic review, all three classes of drug were found to be associated with more side effects than placebo. The selective COX‐2 inhibitor group experienced more hypertension and heart problems. Patients treated with NSAIDs, particularly COX‐2 inhibitors had a higher death rate than the placebo group.

In patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, selective COX‐2 inhibitors have been associated with fewer gastrointestinal side effects than traditional NSAIDs (Deek 2002). Among the AD patients studied, gastrointestinal side effects occurred at a similar rate in both groups for AD.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There no evidence to support the use of aspirin, steroidal or NSAIDs (both traditional NSAIDs and selective COX‐2 inhibitors) in AD. None of the assessed drugs can be recommended for the treatment of AD.

Implications for research.

The results of this review show that currently available evidence does not support the use of aspirin, steroid and NSAIDs (traditional NSAIDs and COX‐2 inhibitors) for treating AD. These results are not in line with the majority of epidemiological data supporting a protective role for anti‐inflammatories in the development of cognitive impairment. However, all of the selected studies were of relatively short duration and in symptomatic people with well established disease. As it is now widely accepted that inflammatory processes contribute to the pathogenesis of AD, future clinical trials need to assess a prophylactic role for anti‐inflammatories. Participants should include those with Mild cognitive impairment and those with normal cognition but with evidence of early disease pathology such as amyloid deposits as assessed on Pet imaging and tau/amyloid ratio in the cerebrospinal fluid. Agents used should not be restricted to COX‐2 inhibitors but need to include traditional NSAIDs as well.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2007 Review first published: Issue 2, 2012

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 26 August 2008 | Amended | When the full review of "Aspirin and anti‐inflammatory drugs for Alzheimer's Disease" is published, it will replace the previously published reviews "Ibuprofen for Alzheimer's Disease", "Indomethacin for Alzheimer's Disease", and the previously published protocol "Naproxen for Alzheimer's Disease". At that time, these ibuprofen and indomethacin reviews and this naproxen protocol will be withdrawn from the Cochrane Library. |

| 26 August 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 14 November 2006 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the consumer editor, Lynne Ramsay and Ruth Chandler, for their helpful comments. We wish to acknowledge the contribution of Rebecca Quinn as the writer of the protocol of this review. We also wish to thank Dr. Helen Collins. We want to express our thanks for the support of the Cochrane dementia and cognitive improvement group for their help coordinating this project.

We thank Dr. Wanruchada Katchamart, Dr. Paula A. Rochon, Dr. Sunila Kalkar and Wei Wu for their practical advice for the review. We also thank Wei Wu for extracting data and filling the translation sheet for the 2 Chinese studies. We thank Ms. Reem Malouf for statistical advice, Dr. Kittphon Nagaviroj for the PDF file for full text assessment form and Inez Kost and Rita Shaughnessy, the librarians at University of Toronto who helped with the article findings and search term respectively.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Pre‐publication search: April 2011

| Source |

Search strategy | Hits retrieved |

| 1. ALOIS (www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/alois) | Keyword search: aspirin OR "cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor" OR aceclofenac OR acemetacin OR betamethasone OR celecoxib OR cortisone OR deflazacort OR dexamethasone OR dexibruprofen OR dexketoprofen OR diclofenac sodium OR diflunisal OR diflusinal OR etodolac OR etoricoxib OR fenbufen OR fenoprofen OR flurbiprofen OR hydrocortisone OR ibuprofen OR indometacin OR indomethacin OR ketoprofen OR lumiracoxib OR mefenamic OR meloxicam OR methylprednisolone OR nabumetone OR naproxen OR nimesulide OR "anti‐inflammatory" OR prednisone OR piroxicam OR sulindac OR tenoxicam OR tiaprofenic acid OR triamcinolone OR NSAIDS OR NSAID | 37 |

| 2. MEDLINE In‐process and other non‐indexed citations and MEDLINE 1950‐present (Ovid SP) | 1. Aspirin/ 2. aspirin*.ti,ab. 3. cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor*.ti,ab. 4. ("anti‐inflammatory agent*" or "antiinflammatory agent" or "antinflammatory agent*").ti,ab. 5. aceclofenac.ti,ab. 6. acemetacin.ti,ab. 7. betamethasone.ti,ab. 8. dexibruprofen.ti,ab. 9. dexketoprofen.ti,ab. 10. "diclofenac sodium".ti,ab. 11. diflunisal.ti,ab. 12. diflusinal.ti,ab. 13. etodolac*.ti,ab. 14. etoricoxib*.ti,ab. 15. (fenbufen* or fenoprofen*).ti,ab. 16. flurbiprofen*.ti,ab. 17. (hydrocortison* or ibuprofen*).ti,ab. 18. (indometacin* or indomethacin*).ti,ab. 19. ketoprofen*.ti,ab. 20. lumiracoxib*.ti,ab. 21. "mefenamic acid".ti,ab. 22. meloxicam*.ti,ab. 23. methylprednisolone.ti,ab. 24. nabumeton*.ti,ab. 25. naproxen.ti,ab. 26. nimesulide.ti,ab. 27. "non‐steroid* anti‐inflammatory agent*".ti,ab. 28. prednisone.ti,ab. 29. piroxicam.ti,ab. 30. sulindac.ti,ab. 31. tenoxicam.ti,ab. 32. "tiaprofenic acid".ti,ab. 33. triamcinolone.ti,ab. 34. Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal/ 35. Anti‐Inflammatory Agents/ 36. NSAID*.ti,ab. 37. or/1‐36 38. Alzheimer Disease/ 39. (alzheimer* or AD or dement*).ti,ab. 40. alzheimer*.ti,ab. 41. (AD or dement*).ti,ab. 42. or/38‐41 43. 37 and 42 44. randomized controlled trial.pt. 45. controlled clinical trial.pt. 46. randomized.ab. 47. placebo.ab. 48. drug therapy.fs. 49. randomly.ab. 50. trial.ab. 51. groups.ab. 52. or/44‐51 53. (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. 54. 52 not 53 55. 43 and 54 56. (2008* or 2009* or 2010* or 2011*).ed. 57. 55 and 56 |

193 |

| 3. EMBASE 1980‐2011 week 15 (Ovid SP) |

1. Aspirin/ 2. aspirin*.ti,ab. 3. cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor*.ti,ab. 4. ("anti‐inflammatory agent*" or "antiinflammatory agent" or "antinflammatory agent*").ti,ab. 5. aceclofenac.ti,ab. 6. acemetacin.ti,ab. 7. betamethasone.ti,ab. 8. dexibruprofen.ti,ab. 9. dexketoprofen.ti,ab. 10. "diclofenac sodium".ti,ab. 11. diflunisal.ti,ab. 12. diflusinal.ti,ab. 13. etodolac*.ti,ab. 14. etoricoxib*.ti,ab. 15. (fenbufen* or fenoprofen*).ti,ab. 16. flurbiprofen*.ti,ab. 17. (hydrocortison* or ibuprofen*).ti,ab. 18. (indometacin* or indomethacin*).ti,ab. 19. ketoprofen*.ti,ab. 20. lumiracoxib*.ti,ab. 21. "mefenamic acid".ti,ab. 22. meloxicam*.ti,ab. 23. methylprednisolone.ti,ab. 24. nabumeton*.ti,ab. 25. naproxen.ti,ab. 26. nimesulide.ti,ab. 27. "non‐steroid* anti‐inflammatory agent*".ti,ab. 28. prednisone.ti,ab. 29. piroxicam.ti,ab. 30. sulindac.ti,ab. 31. tenoxicam.ti,ab. 32. "tiaprofenic acid".ti,ab. 33. triamcinolone.ti,ab. 34. NSAID*.ti,ab. 35. nonsteroid antiinflammatory agent/ 36. antiinflammatory agent/ 37. or/1‐36 38. ALZHEIMER DISEASE/ 39. (alzheimer* or AD or dement*).ti,ab. 40. or/38‐39 41. 37 and 40 42. randomly.ti,ab. 43. trial.ti,ab. 44. placebo.ab. 45. clinical trial/ 46. "double‐blind*".ti,ab. 47. (2008* or 2009* or 2010* or 2011*).em. 48. or/42‐46 49. 41 and 48 50. 47 and 49 |

460 |

| 4. PSYCINFO 1806‐April week 2 2011 (Ovid SP) |

1. Aspirin/ 2. aspirin*.ti,ab. 3. cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor*.ti,ab. 4. ("anti‐inflammatory agent*" or "antiinflammatory agent" or "antinflammatory agent*").ti,ab. 5. aceclofenac.ti,ab. 6. acemetacin.ti,ab. 7. betamethasone.ti,ab. 8. dexibruprofen.ti,ab. 9. dexketoprofen.ti,ab. 10. "diclofenac sodium".ti,ab. 11. diflunisal.ti,ab. 12. diflusinal.ti,ab. 13. etodolac*.ti,ab. 14. etoricoxib*.ti,ab. 15. (fenbufen* or fenoprofen*).ti,ab. 16. flurbiprofen*.ti,ab. 17. (hydrocortison* or ibuprofen*).ti,ab. 18. (indometacin* or indomethacin*).ti,ab. 19. ketoprofen*.ti,ab. 20. lumiracoxib*.ti,ab. 21. "mefenamic acid".ti,ab. 22. meloxicam*.ti,ab. 23. methylprednisolone.ti,ab. 24. nabumeton*.ti,ab. 25. naproxen.ti,ab. 26. nimesulide.ti,ab. 27. "non‐steroid* anti‐inflammatory agent*".ti,ab. 28. prednisone.ti,ab. 29. piroxicam.ti,ab. 30. sulindac.ti,ab. 31. tenoxicam.ti,ab. 32. "tiaprofenic acid".ti,ab. 33. triamcinolone.ti,ab. 34. NSAID*.ti,ab. 35. Anti Inflammatory Drugs/ 36. or/1‐35 37. exp Alzheimer's Disease/ 38. (AD or alzheimer* or dement*).ti,ab. 39. or/37‐38 40. 36 and 39 41. (random* or trial or placebo or "double‐blind*" or "single‐blind*").ti,ab. 42. exp Clinical Trials/ 43. 41 or 42 44. 40 and 43 45. (2008* or 2009* or 2010* or 2011*).up. 46. 44 and 45 |

26 |

| 5. CINAHL (EBSCOhost) | S1 (MH "Dementia+") S2 (MH "Delirium") or (MH "Delirium, Dementia, Amnestic, Cognitive Disorders") S3 (MH "Wernicke's Encephalopathy") S4 TX dement* S5 TX alzheimer* S6 TX lewy* N2 bod* S7 TX deliri* S8 TX chronic N2 cerebrovascular S9 TX "organic brain disease" or "organic brain syndrome" S10 or/S1‐S9 S11 MH non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory agent S12 MH Aspirin S13 TX aspirin S14TX "cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor*" OR aceclofenac OR acemetacin OR betamethasone OR celecoxib OR cortisone OR deflazacort OR dexamethasone OR dexibruprofen OR dexketoprofen OR diclofenac sodium OR diflunisal OR diflusinal OR etodolac OR etoricoxib OR fenbufen OR fenoprofen OR flurbiprofen OR hydrocortisone OR ibuprofen OR indometacin OR indomethacin OR ketoprofen OR lumiracoxib OR mefenamic OR meloxicam OR methylprednisolone OR nabumetone OR naproxen OR nimesulide OR "anti‐inflammatory" OR prednisone OR piroxicam OR sulindac OR tenoxicam OR tiaprofenic acid OR triamcinolone S15 or/S11‐S14 S16 S10 AND S15 S17 TX random* OR placebo* OR trial OR group OR “double‐blind*” S18 MH Clinical Trial S19 S17 AND S18 S20 S19 AND S16 |

74 |

| 6. ISI Web of Knowledge – all databases [includes: Web of Science (1945‐present); BIOSIS Previews (1926‐present); MEDLINE (1950‐present); Journal Citation Reports] | Topic=(aspirin OR "cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor*" OR aceclofenac OR acemetacin OR betamethasone OR celecoxib OR cortisone OR deflazacort OR dexamethasone OR dexibruprofen OR dexketoprofen OR diclofenac sodium OR diflunisal OR diflusinal OR etodolac OR etoricoxib OR fenbufen OR fenoprofen OR flurbiprofen OR hydrocortisone OR ibuprofen OR indometacin OR indomethacin OR ketoprofen OR lumiracoxib OR mefenamic OR meloxicam OR methylprednisolone OR nabumetone OR naproxen OR nimesulide OR "anti‐inflammatory" OR prednisone OR piroxicam OR sulindac OR tenoxicam OR tiaprofenic acid OR triamcinolone) AND Topic=(Alzheimer* OR AD) AND Topic=(randomized OR randomised OR placebo OR "double‐blind*" OR randomly OR RCT OR trial OR CCT) AND Year Published=(2008‐2011) |

244 |

| 7. LILACS (BIREME) | aspirin OR anti‐inflammatory [Words] and alzheimer OR AD [Words] | 18 |

| 8. CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library) (Issue 1 of 4, Jan 2011) | #1 aspirin OR aceclofenac OR acemetacin OR betamethasone OR celecoxib OR cortisone OR "cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor*" OR deflazacort OR dexamethasone OR dexibruprofen OR dexketoprofen OR diclofenac sodium OR diflunisal OR diflusinal OR etodolac OR etoricoxib OR fenbufen OR fenoprofen OR flurbiprofen OR hydrocortisone OR ibuprofen OR indometacin OR indomethacin OR ketoprofen OR lumiracoxib OR mefenamic OR meloxicam OR methylprednisolone OR nabumetone OR naproxen OR nimesulide OR "anti‐inflammatory" OR prednisone OR piroxicam OR sulindac OR tenoxicam OR tiaprofenic OR triamcinolone #2 alzheimer* OR AD #3 (#1 AND #2), from 2008 to 2011 |

88 |

| 9. Clinicaltrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) | alzheimer OR alzheimers OR AD | aspirin OR anti‐imflammatory OR celecoxib OR cortisone OR ibuprofen | received from 01/01/2008 to 04/20/2011 | 6 |

| 10. ICTRP Search Portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch) [includes: Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry; ClinicalTrilas.gov; ISRCTN; Chinese Clinical Trial Registry; Clinical Trials Registry – India; Clinical Research Information Service – Republic of Korea; German Clinical Trials Register; Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials; Japan Primary Registries Network; Pan African Clinical Trial Registry; Sri Lanka Clinical Trials Registry; The Netherlands National Trial Register] | (aspirin OR anti‐inflammatory OR dexamethasone OR dexibruprofen OR dexketoprofen OR diclofenac sodium OR diflunisal OR diflusinal OR etodolac OR etoricoxib OR fenbufen OR fenoprofen OR flurbiprofen OR hydrocortisone OR ibuprofen OR indometacin OR indomethacin OR ketoprofen OR lumiracoxib OR mefenamic OR meloxicam OR methylprednisolone OR nabumetone OR naproxen OR nimesulide OR "anti‐inflammatory" OR prednisone OR piroxicam OR sulindac OR tenoxicam OR tiaprofenic OR triamcinolone OR NSAIDS) AND (rec from: 01/01/2008 to 20/04/2011) |

77 |

| TOTAL before de‐duplication | 1223 | |

| TOTAL after de‐dupe and first‐assess | 116 | |

Appendix 2. Initial search: September 2008

| Source searched | Date of search | Search strategy used |

| PubMed (MEDLINE) | 8 September 2008 | (aspirin OR aceclofenac OR acemetacin OR betamethasone OR celecoxib OR cortisone OR deflazacort OR prednisone OR dexamethasone OR dexibruprofen OR dexketoprofen OR diclofenac sodium OR diflusinal OR etodolac OR etoricoxib OR fenbufen OR fenoprofen OR flurbiprofen OR hydrocortisone OR ibuprofen OR indomethacin OR indometacin OR ketoprofen OR lumiracoxib OR mefenamic acid OR meloxicam OR methylprednisolone OR nabumetone OR naproxen OR nimesulide OR piroxicam OR sulindac OR tenoxicam OR tiaprofenic acid OR triamcinolone OR cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor* OR anti‐inflammatory agent*) AND (Alzheimer* OR dementia OR ((cognit* or memory* or mental*) and (declin* or impair* or los* or deteriorat*)) AND (randomized OR randomized OR double blind* OR single blind* OR placebo* OR controlled) |

| EMBASE (Ovid SP) | 9 September 2008 | as PubMed |

| CINAHL (Ovid SP) | 9 September 2008 | as PubMed |

| PsycINFO (Ovid SP) | 9 September 2008 | as PubMed |

| LILACS (Bireme) | 9 September 2008 | (aspirin OR aceclofenac OR acemetacin OR betamethasone OR celecoxib OR cortisone OR deflazacort OR prednisone OR dexamethasone OR dexibruprofen OR dexketoprofen OR diclofenac sodium OR diflusinal OR etodolac OR etoricoxib OR fenbufen OR fenoprofen OR flurbiprofen OR hydrocortisone OR ibuprofen OR indomethacin OR indometacin OR ketoprofen OR lumiracoxib OR mefenamic acid OR meloxicam OR methylprednisolone OR nabumetone OR naproxen OR nimesulide OR piroxicam OR sulindac OR tenoxicam OR tiaprofenic acid OR triamcinolone OR cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor* OR anti‐inflammatory agent*) AND (Alzheimer* OR dementia) |

| CDCIG Specialized Register | 8 September 2008 | (aspirin OR aceclofenac OR acemetacin OR betamethasone OR celecoxib OR cortisone OR deflazacort OR prednisone OR dexamethasone OR dexibruprofen OR dexketoprofen OR diclofenac sodium OR diflusinal OR etodolac OR etoricoxib OR fenbufen OR fenoprofen OR flurbiprofen OR hydrocortisone OR ibuprofen OR indomethacin OR indometacin OR ketoprofen OR lumiracoxib OR mefenamic acid OR meloxicam OR methylprednisolone OR nabumetone OR naproxen OR nimesulide OR piroxicam OR sulindac OR tenoxicam OR tiaprofenic acid OR triamcinolone OR cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor* OR anti‐inflammatory agent*) |

| CENTRAL | Issue 3/2008 | (aspirin OR aceclofenac OR acemetacin OR betamethasone OR celecoxib OR cortisone OR deflazacort OR prednisone OR dexamethasone OR dexibruprofen OR dexketoprofen OR diclofenac sodium OR diflusinal OR etodolac OR etoricoxib OR fenbufen OR fenoprofen OR flurbiprofen OR hydrocortisone OR ibuprofen OR indomethacin OR indometacin OR ketoprofen OR lumiracoxib OR mefenamic acid OR meloxicam OR methylprednisolone OR nabumetone OR naproxen OR nimesulide OR piroxicam OR sulindac OR tenoxicam OR tiaprofenic acid OR triamcinolone OR cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor* OR anti‐inflammatory agent*) AND (Alzheimer* OR dementia OR ((cognit* or memory* or mental*) and (declin* or impair* or los* or deteriorat*)) |

| ISI Conference Proceedings | 10 September 2008 | (aspirin OR aceclofenac OR acemetacin OR betamethasone OR celecoxib OR cortisone OR deflazacort OR prednisone OR dexamethasone OR dexibruprofen OR dexketoprofen OR diclofenac sodium OR diflusinal OR etodolac OR etoricoxib OR fenbufen OR fenoprofen OR flurbiprofen OR hydrocortisone OR ibuprofen OR indomethacin OR indometacin OR ketoprofen OR lumiracoxib OR mefenamic acid OR meloxicam OR methylprednisolone OR nabumetone OR naproxen OR nimesulide OR piroxicam OR sulindac OR tenoxicam OR tiaprofenic acid OR triamcinolone OR cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor* OR anti‐inflammatory agent*) AND (Alzheimer* OR dementia) |

| mRCT including ISRCTN Register, ClinicalTrials.gov |

10 September 2008 | (aspirin OR aceclofenac OR acemetacin OR betamethasone OR celecoxib OR cortisone OR deflazacort OR prednisone OR dexamethasone OR dexibruprofen OR dexketoprofen OR diclofenac sodium OR diflusinal OR etodolac OR etoricoxib OR fenbufen OR fenoprofen OR flurbiprofen OR hydrocortisone OR ibuprofen OR indomethacin OR indometacin OR ketoprofen OR lumiracoxib OR mefenamic acid OR meloxicam OR methylprednisolone OR nabumetone OR naproxen OR nimesulide OR piroxicam OR sulindac OR tenoxicam OR tiaprofenic acid OR triamcinolone OR cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor* OR anti‐inflammatory agent*) AND (Alzheimer* OR dementia) |

| IFPMA, UMIN Japan trials register, Netherland trials register, Australasian Digital theses, Theses Canada, DATAD | 10 September 2008 | Alzheimer’s disease |

Appendix 3. measurement agreement

Kappa statistic was used to measure agreement between 2 authors who make a decision for inclusion and exclusion.From calculation, kappa is 0.782. It should be noted that this calculation is based on the first decision making of both reviewers.

Meaning of kappa statistic

0.40‐0.59: fair agreement

0.60‐0.74: good agreement

0.75 or more: excellent agreement

From 488 studies, there were 19 studies that we did not agree and required more discussion. Although measuring agreement showed excellent agreement, it should be considered that the discussion is still the main part of the decision making. However, kappa helped us to revisit inclusion criteria again whether it is clear enough for both reviewers in case of poor agreement. Occasionally, we have to revisit and clarify the inclusion and exclusion criteria to assure that all reviewers are on the same page. For example, three reviewers at one point were not sure if we should include all studies of anti‐inflammatory. After the discussion, we understood that we will only focus on aspirin, steroidal and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory. This leaded to the change of the review’s title.

| Review Author 1 (DJ) |

Review author 2 (MI) | |||||||

| Include | Exclude | Unsure | ||||||

| Include | 39 (a) | 1 (b) | 1 (c) | |||||

| Exclude | 11 (d) | 546 (e) | 2 (f) | |||||

| Unsure | 0 (g) | 4 (h) | 0 (i) | |||||

| Total | 50 (A2) | 551 (E2) | 3 (U2) | |||||

Po = a+e+i / K Po = 39+546+0 /604 = 0.969

PE = (A1xA2) + (E1+E2) + (U1+U2) / K2 PE = (41x50) + (559x551) + (4x3) /6042 = 0.850

Kappa = Po PE/ 1‐PE Kappa = 0.969‐0.850/ 1‐0.850 = 0.793

Appendix 4. Translation sheet

Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group

Translation sheet.

To be completed by the translator.

Please note: full translations of papers are not necessary. The following questions are designed to assist in the extraction of necessary information for the inclusion of randomised controlled trials.

Date of translation:

Translator:

Language of the paper:

1. Publication details

Authors:

Title (in English):

Original title:

Publication details:

(journal, volume, year, page nos)

If details are not reported, please indicate so.

2. Materials and Methods

Is the trial described as RANDOMISED?

(NB ‐ if the paper is not described as randomised, we do not require any further information, but please give a description of the study, ie, a review article, a case controlled trial, a letter to a journal, a double blind trial in which treatment was not randomised etc).

If YES, the following details are necessary:

Was it a parallel or cross‐over study?

What were the patients described as suffering from?

Diagnostic criteria

Number of patients involved:

Gender ratio:

Age groups (please give Means and SDs) (+/‐ values if reported):

Where were the patients recruited from?

Was the treatment double blinded?

Are the allocation of treatment methods described, if so what were they?

What was the treatment compared with (placebo or standard therapies)?

Where did the study take place (city, multi‐centre, hospital, community)?

How long did the trial last for?

Was there a follow‐up period? If yes, over how long did it take place?

What were the inclusion/exclusion criteria?

What was the dosage involved (if the treatment was pharmacological)?

What were the dosages for the control/placebo group?

3. Results

How were baseline measurements recorded?

What were the outcome measures?

Over what period were values recorded for the outcome measures?

Were there any drop outs reported? If so, how many?

Data:

Were the continuous data reported as Means and SDs/SEMs/Confidence Intervals? Please provide page numbers where results were presented to facilitate double‐checking

What outcomes were presented as binary data?

Were the results reported in tables/graphs?

If, so please indicate on the axes of the copy sent to you, what the headings mean in English, and return with this sheet.

What is the value (e.g. % or otherwise) to describe the increase for each of the outcome measures that are reported? Please give +/‐ values if reported. Please indicate where these values can be found in the original article (this will help to facilitate validation).

Is there any additional information which you consider significant?

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Aspirin vs. aspirin avoidance.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Bleeding | 1 | 310 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.90 [2.43, 25.69] |

| 2 Death | 1 | 310 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.70, 1.46] |

| 3 Institutionaliation | 1 | 310 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.50, 1.74] |

Comparison 2. Steroids vs. placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ADAScog | 1 | 138 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.90 [‐0.48, 4.28] |

| 2 Confusion | 1 | 138 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.33 [0.88, 2.01] |

| 3 hyperglycemia | 1 | 138 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 5.0 [1.14, 21.99] |

| 4 Abnormal lab results | 1 | 138 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.55 [1.38, 4.70] |

| 5 Face edema | 1 | 138 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.87 [1.10, 3.17] |

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Steroids vs. placebo, Outcome 2 Confusion.

Comparison 3. NSAIDs vs. placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cognition:ADAScog all studies | 9 | 1745 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.41 [‐3.13, 0.32] |

| 1.1 traditional NSAIDs vs placebo | 6 | 411 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.81 [‐7.94, 0.33] |

| 1.2 Selective COX‐2 inhibitor | 4 | 1334 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.30 [‐0.99, 1.60] |

| 2 Cognition:MMSE all | 6 | 1268 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.08 [‐2.21, 0.04] |

| 2.1 traditional NSAIDs vs placebo | 4 | 234 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.22 [‐6.58, 0.14] |

| 2.2 Selective COX‐2 inhibitor | 2 | 1034 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.34 [‐0.07, 0.76] |

| 3 CIBIC+ | 3 | 1099 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.04 [‐0.09, 0.16] |

| 3.1 traditional NSAIDs vs placebo | 1 | 38 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.10 [‐0.58, 0.38] |

| 3.2 Selective COX‐2 inhibitor | 2 | 1061 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.05 [‐0.08, 0.18] |

| 4 CDR sum score | 3 | 1124 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.03 [‐0.25, 0.30] |

| 4.1 traditional NSAIDs vs placebo | 1 | 229 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.10 [‐0.50, 0.70] |

| 4.2 Selective COX‐2 inhibitor | 3 | 895 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.30, 0.32] |

| 5 NPI | 3 | 632 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.14, 1.49] |

| 5.1 traditional NSAIDs vs placebo | 3 | 399 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.14, 1.54] |

| 5.2 Selective COX‐2 inhibitor | 1 | 233 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [‐2.54, 3.34] |

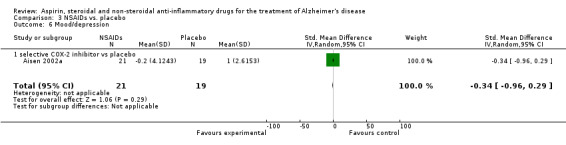

| 6 Mood/depression | 1 | 40 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.34 [‐0.96, 0.29] |

| 6.1 selective COX‐2 inhibitor vs placebo | 1 | 40 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.34 [‐0.96, 0.29] |

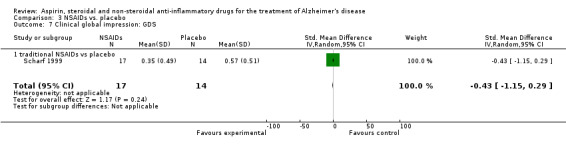

| 7 Clinical global impression: GDS | 1 | 31 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.43 [‐1.15, 0.29] |

| 7.1 traditional NSAIDs vs placebo | 1 | 31 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.43 [‐1.15, 0.29] |

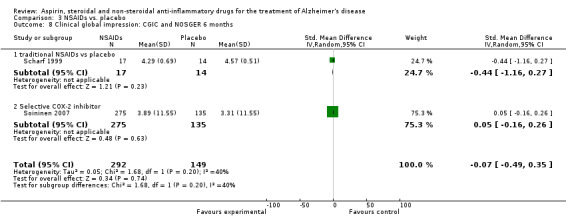

| 8 Clinical global impression: CGIC and NOSGER 6 months | 2 | 441 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.07 [‐0.49, 0.35] |

| 8.1 traditional NSAIDs vs placebo | 1 | 31 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.44 [‐1.16, 0.27] |

| 8.2 Selective COX‐2 inhibitor | 1 | 410 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.05 [‐0.16, 0.26] |

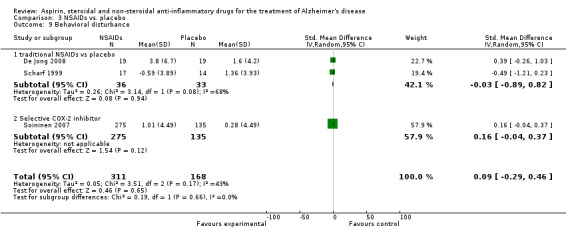

| 9 Behavioral disturbance | 3 | 479 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.09 [‐0.29, 0.46] |

| 9.1 traditional NSAIDs vs placebo | 2 | 69 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.03 [‐0.89, 0.82] |

| 9.2 Selective COX‐2 inhibitor | 1 | 410 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.16 [‐0.04, 0.37] |

| 10 Activity of daily living | 7 | 1737 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.22 [‐0.48, 0.04] |

| 10.1 traditional NSAIDs vs placebo | 4 | 375 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.48 [‐0.97, 0.01] |

| 10.2 Selective COX‐2 inhibitor | 4 | 1362 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.03 [‐0.22, 0.17] |

| 11 Quality of life | 2 | 382 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.08 [‐0.14, 0.29] |

| 11.1 traditional NSAIDs vs placebo | 2 | 205 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.07 [‐0.22, 0.36] |

| 11.2 Selective COX‐2 inhibitor | 1 | 177 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.09 [‐0.23, 0.41] |

| 12 Caregiver burden | 3 | 201 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.35 [‐0.63, ‐0.07] |

| 12.1 traditional NSAIDs vs placebo | 3 | 201 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.35 [‐0.63, ‐0.07] |

| 13 Gastrointestinal side effects | 9 | 1675 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.94 [1.36, 2.77] |

| 14 Elevated creatinine | 2 | 92 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.30 [0.54, 34.30] |

| 15 Elevated liver function test | 3 | 132 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.27 [0.97, 18.76] |

| 16 Headache | 4 | 577 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.34, 3.44] |

| 17 Psychiatric side effects | 4 | 586 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.67, 1.86] |

| 18 Bleeding | 1 | 425 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.45 [0.18, 66.35] |

| 19 Heart disease | 2 | 776 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.58 [1.48, 38.90] |

| 20 Cerebrovascular side effects | 4 | 1555 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.54, 2.02] |

| 21 Hypertension | 2 | 402 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.41 [1.36, 21.60] |

| 22 Hyperglycemia | 1 | 51 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.92 [0.19, 19.90] |

| 23 Rash | 2 | 61 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.47 [1.00, 12.04] |

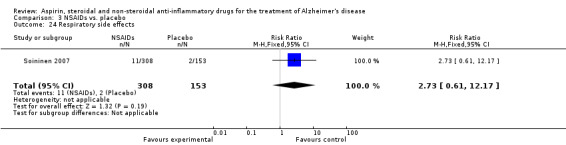

| 24 Respiratory side effects | 1 | 461 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.73 [0.61, 12.17] |

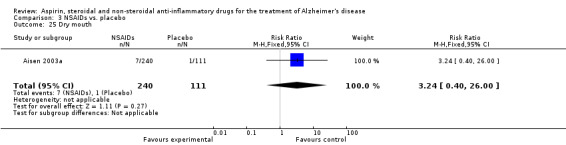

| 25 Dry mouth | 1 | 351 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.24 [0.40, 26.00] |

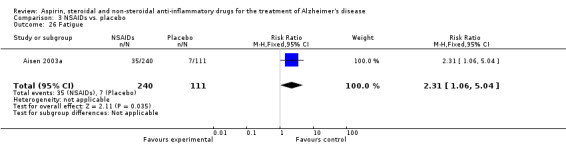

| 26 Fatigue | 1 | 351 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.31 [1.06, 5.04] |

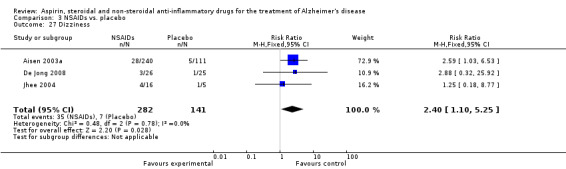

| 27 Dizziness | 3 | 423 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.40 [1.10, 5.25] |

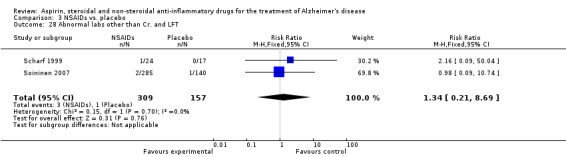

| 28 Abnormal labs other than Cr. and LFT | 2 | 466 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.34 [0.21, 8.69] |

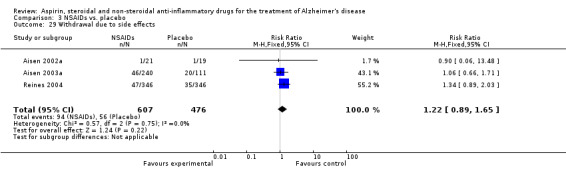

| 29 Withdrawal due to side effects | 3 | 1083 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.89, 1.65] |

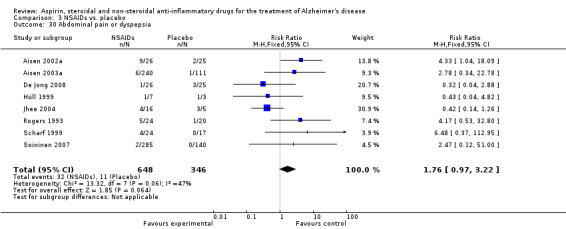

| 30 Abdominal pain or dyspepsia | 8 | 994 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.76 [0.97, 3.22] |

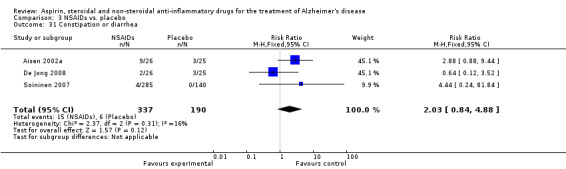

| 31 Constipation or diarrhea | 3 | 527 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.03 [0.84, 4.88] |

| 32 Nausea or vomiting | 3 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.69 [0.39, 7.38] |

| 33 Death | 9 | 1711 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.67 [0.85, 3.31] |

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 5 NPI.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 6 Mood/depression.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 7 Clinical global impression: GDS.

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 8 Clinical global impression: CGIC and NOSGER 6 months.

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 9 Behavioral disturbance.

3.10. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 10 Activity of daily living.

3.11. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 11 Quality of life.

3.14. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 14 Elevated creatinine.

3.15. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 15 Elevated liver function test.

3.16. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 16 Headache.

3.17. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 17 Psychiatric side effects.

3.18. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 18 Bleeding.

3.19. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 19 Heart disease.

3.20. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 20 Cerebrovascular side effects.

3.21. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 21 Hypertension.

3.22. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 22 Hyperglycemia.

3.23. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 23 Rash.

3.24. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 24 Respiratory side effects.

3.25. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 25 Dry mouth.

3.26. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 26 Fatigue.

3.27. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 27 Dizziness.

3.28. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 28 Abnormal labs other than Cr. and LFT.

3.29. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 29 Withdrawal due to side effects.

3.30. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 30 Abdominal pain or dyspepsia.

3.31. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 31 Constipation or diarrhea.

3.32. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 32 Nausea or vomiting.

3.33. Analysis.

Comparison 3 NSAIDs vs. placebo, Outcome 33 Death.

Comparison 4. Traditional NSAIDs vs. placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Nausea or vomiting | 1 | 51 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.81 [0.24, 95.58] |

| 1.1 traditional NSAIDs | 1 | 51 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.81 [0.24, 95.58] |

| 2 Gastrointestinal side effects | 5 | 320 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.43 [0.68, 3.00] |

| 2.1 traditional NSAIDs | 5 | 320 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.43 [0.68, 3.00] |

| 3 Elevated creatinine | 2 | 92 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.30 [0.54, 34.30] |

| 3.1 traditional NSAIDs | 2 | 92 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.30 [0.54, 34.30] |

| 4 Elevated liver function test | 2 | 92 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.04 [0.48, 33.98] |