Abstract

Objectives

To estimate age standardised suicide rate ratios in male and female physicians compared with the general population, and to examine heterogeneity across study results.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

Studies published between 1960 and 31 March 2024 were retrieved from Embase, Medline, and PsycINFO. There were no language restrictions. Forward and backwards reference screening was performed for selected studies using Google Scholar.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

Observational studies with directly or indirectly age standardised mortality ratios for physician deaths by suicide, or suicide rates per 100 000 person years of physicians and a reference group similar to the general population, or extractable data on physician deaths by suicide suitable for the calculation of ratios. Two independent reviewers extracted data and assessed the risk of bias using an adapted version of the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist for prevalence studies. Mean effect estimates for male and female physicians were calculated based on random effects models, with subgroup analyses for geographical region and a secondary analysis of deaths by suicide in physicians compared with other professions.

Results

Among 39 included studies, 38 studies for male physicians and 26 for female physicians were eligible for analyses, with a total of 3303 suicides in male physicians and 587 in female physicians (observation periods 1935-2020 and 1960-2020, respectively). Across all studies, the suicide rate ratio for male physicians was 1.05 (95% confidence interval 0.90 to 1.22). For female physicians, the rate ratio was significantly higher at 1.76 (1.40 to 2.21). Heterogeneity was high for both analyses. Meta-regression revealed a significant effect of the midpoint of study observation period, indicating decreasing effect sizes over time. The suicide rate ratio for male physicians compared with other professions was 1.81 (1.55 to 2.12).

Conclusion

Standardised suicide rate ratios for male and female physicians decreased over time. However, the rates remained increased for female physicians. The findings of this meta-analysis are limited by a scarcity of studies from regions outside of Europe, the United States, and Australasia. These results call for continued efforts in research and prevention of physician deaths by suicide, particularly among female physicians and at risk subgroups.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42019118956.

Introduction

In 2019, suicide caused over 700 000 deaths globally, which was more than one in every 100 deaths that year (1.3%). While the worldwide age standardised suicide rate was estimated at 9.0 per 100 000 population, there was great variation between individual countries (from <2 to >80 suicide deaths per 100 000).1 The overall global decline in suicide rates by 36% since 2000 is not a universal trend because some countries like the United States or Brazil saw an increase of roughly the same magnitude.1 2 Among many other social and environmental factors, occupation has been shown to influence suicide risk beyond established risk factors such as low socioeconomic status or educational attainment.3 4 5 6 7

Physicians are one of several occupational groups linked to a higher risk of death by suicide, and the medical community has a longstanding and often conflicted history in addressing this issue.8 A JAMA editorial from 1903 reviewed annual suicide numbers for US physicians and concluded that their suicide risk is higher compared with the general population.9 A substantial amount of evidence has been accumulated globally in the 120 years since then, providing more insight on the topic and the challenges involved in its assessment. Most earlier research reported higher suicide rates for male and female physicians compared with the general population, and the mean effect estimates from the first meta-analysis in 2004 indicated a significantly increased standardised mortality ratio (SMR) of 1.41 for male physicians and 2.27 for female physicians.10 This meta-analysis included 22 studies on suicide in physicians with observation periods between 1910 and 1998 and revealed some heterogeneity among study results, which was partly explained by the decline in risk over time. Similarly, another meta-analysis that included nine studies with observation periods between 1980 and 2015 reported a significantly decreased SMR of 0.68 for male physicians and a significantly increased SMR of 1.46 for female physicians.11

In addition to publication year, several other factors could potentially drive heterogeneity between the published studies. Methodological differences in study design, outcome measures, and level of age standardisation could explain heterogeneity between studies. Furthermore, individual countries and world regions have varying levels of stigma about suicide in general and among physicians in particular, associated with different risks of underreporting, access to support systems, and generally different training and working conditions.

In this study, we aimed to perform an appraisal of the currently available evidence on suicide deaths in male and female physicians compared with the general population. We also aimed to explore heterogeneity by considering a broader spectrum of potential covariates. We hypothesise that suicide rate ratios for male and female physicians have declined over time, but gender differences persist and suicide risk remains increased for female physicians.

Methods

Search strategy and study selection

This meta-analysis was conducted based on recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration,12 and is reported in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement.13 We searched for observational studies with data on suicide rates in physicians compared with the general population or similar using Medline, PsycINFO, and Embase. “Physician,” “mortality,” and “suicide” were entered as MeSH terms and text words and then connected through Boolean operators. The specific search strategy was developed and adapted for each database with the support of librarians from the Medical University of Vienna (supplement table S1). Following Schernhammer and Colditz,10 we limited the search period to articles published after 1960 but updated it through to 31 March 2024. No constraints were placed on the language in which the reports were written, the region where study participants lived, or their age group. Articles published in languages other than English or German were screened with the help of the translation software DeepL14 and colleagues fluent in these languages. Screening of the literature was done independently by two reviewers (CZ and SS). We also performed forward and backwards reference screening for the included articles and searched for unpublished data from sources and databases listed in included articles, such as the US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, the UK Office for National Statistics, Switzerland’s Federal Statistical Office, and Statistics Denmark.

We excluded studies that reported only on specific suicide methods in physicians, non-fatal suicidal behaviour or thoughts, mental health and burnout, and suicide prevention. We also excluded conference abstracts, editorials, case studies, and letters. Only reports with adequate data about physician deaths by suicide (not attempts) were eligible.

At the full text screening stage, we decided to only include rate based outcome measures that compare the suicide mortality in a physician population with the suicide mortality in a reference population. This includes the indirectly standardised mortality ratio (SMR), directly standardised rate ratio (SRR), and the comparative mortality figure. Even though their formulas and recommended uses differ and might yield slightly different results when calculated for the exact same population,15 it can be argued that they are comparable estimates for the purpose of meta-analysing suicide deaths in physicians compared with a reference population. We also included rate ratios, even though their level of age standardisation is typically less detailed and only comprises one age group (with lower or upper age cutoff points). However, the proportionate mortality ratio expresses a different concept (the cause specific SMR divided by the all cause SMR, or the rate of suicides in all physician deaths divided by the rate of suicides in all population deaths). This outcome measure is not suitable for calculation of combined estimates with SMRs, especially in target populations with higher general life expectancy like physicians,16 and was therefore not included. We also excluded studies that reported odds ratios and relative risk calculations because these are not based on rates.

We avoided overlapping time periods of the same geographical regions among included studies so that any physician death by suicide would only be counted once towards the pooled result. In case of overlaps, only one study was included, and the decision of which to include was based on three criteria in sequential order: sample size (higher number of observed suicides); risk of bias (lower risk of bias based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist for prevalence studies); and recentness (more recent midpoint of observation period). We also excluded studies that only reported overall (and not gender stratified) suicide ratios, only covered physician subgroups (eg, medical specialties), or did not meet minimum requirements for sample size (ie, an expected number of one suicide). When necessary information for inclusion was missing from eligible studies or the source of data was unclear, we contacted the authors. We excluded studies if the necessary information could not be obtained. A detailed list of excluded references including reason for exclusion can be found in the supplement (table S2).

Data extraction and risk of bias

Data extraction was conducted by two reviewers (CZ and SS) using a standardised table in Microsoft Excel. If studies did not include an SMR, but reported the numbers of observed (O) and expected (E) suicides or the necessary information to calculate them, the SMR was calculated by the reviewers (SMR=O/E). If the studies did not include an SRR or rate ratio, but reported (age standardised) suicide rates per 100 000 person years for physicians (R1) and a suitable reference population (R2) for a similar time period, the SRR or rate ratio was calculated (SRR=R1/R2, rate ratio=R1/R2). For one study, R1 and R2 were estimated from graphs.17 Because not all studies reported confidence limits and the ones that did used different methods, we calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all studies based on Fisher’s exact test using observed and expected suicide numbers. For SRRs or rate ratios, we calculated the expected suicides by treating the SRR as an SMR (E=O/SRR). Standard errors were derived from the calculated 95% CIs by using the formula recommended for ratios in the Cochrane handbook (standard error=(ln upper CI limit – ln lower CI limit)/3.92).12

In addition to variables relating to the main outcome, we extracted data on the following study characteristics to be used in sensitivity analyses: geographical location, observation period, age range, level of age standardisation, suicide classification, study design, and reference group. We used duplicate extraction and checked the final extraction table for errors to ensure accuracy.

Because there was no suitable validated scale to assess the quality of observational studies on mortality ratios, we used the JBI checklist for prevalence studies18 as a critical appraisal tool for risk of bias assessment. Out of nine questions on this checklist, three were deemed not applicable owing to the investigation of mortality rather than morbidity (see supplement table S3a). Two reviewers (CZ and SS) independently evaluated a subsample of the included studies and the JBI checklist was subsequently further specified to achieve clear criteria for risk of bias assessment (see supplement table S3b). The same two reviewers then independently evaluated all studies (supplement table S4a and S4b). Consistency in rating was high, disagreements were resolved through discussion. If all applicable items of the JBI checklist were rated positive, a study was classified as having low risk of bias. If at least one item was rated negative or unclear, a study was classified as having moderate or high risk of bias.

Data analysis

We performed separate meta-analyses of suicide rate ratios for male and female physicians. Random effects models were chosen a priori owing to the assumption that the included studies represent a random sample of different yet comparable physician populations with some heterogeneity in effect size.19 Random effects models were calculated based on the Hartung-Knapp method (also known as the Sidik-Jonkman method).20 Cumulative meta-analyses were performed to examine changes in the overall mean effect estimate over time. Heterogeneity was assessed by Q tests, I2, T2, and prediction intervals.

Begg and Egger tests were conducted to evaluate the possibility of publication bias, which was also assessed by funnel plot and trim-and-fill analysis. We performed sensitivity analyses using meta-regression (for single covariates and adjusted for study observation period midpoint), including binary variables for several study characteristics (see supplement table S5a and S5b): risk of bias (low risk v moderate or high risk studies), study design (registry based studies v others), outcome measures (SMR v others), level of age standardisation (detailed with several age groups used v others), suicide classification (narrow international classification of diseases (ICD) definition without deaths of undetermined intent v others), age range (studies with a cutoff point around retirement age v others), and reference group (general population v similar). We also performed meta-regressions for length of observation period and number of suicides. Subgroup analysis was performed to assess geographical differences in two categorisations: World Health Organization world regions (with studies from the Americas, European Region, and Western Pacific Region for male and female physicians, only one study from the African Region for male physicians, and no studies from the South East Asian and Eastern Mediterranean Region) and most common study origin regions, reflecting the accumulation of reports from certain parts of the world (US, UK, Scandinavia, other European countries, rest of the world). We also used subgroups to calculate mean effect estimates in older and more recent studies. Two groups were formed based on the midpoint of study observation period, with one subgroup consisting of the 10 most recent studies, and another subgroup with the remaining studies. To accommodate for multiple testing, we adapted the level of significance to P<0.01 for all sensitivity analyses.

We conducted a secondary meta-analysis on suicide rates in physicians compared with another reference group that was more similar than the general population in terms of socioeconomic status. Studies were included if they provided data on deaths by suicide in physicians as well as a group of other professions with similar socioeconomic status (all other eligibility criteria remained the same).

All analyses were performed with Stata (version 17). This study was registered at the International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under CRD42019118956.

Patient and public involvement

Several authors of this paper have trained and worked as physicians, and lived through the loss of colleagues to suicide. Their firsthand experiences offered valuable insights similar to those typically provided by patients. Because of the highly methodical nature of a systematic review and meta-analysis, it was difficult to involve members of the public in most areas of the study design and execution. However, patient and public involvement representatives reviewed the manuscript after submission and offered suggestions on language, dissemination, and general improvements to increase its relevance to those affected by physician deaths by suicide.

Results

Included studies

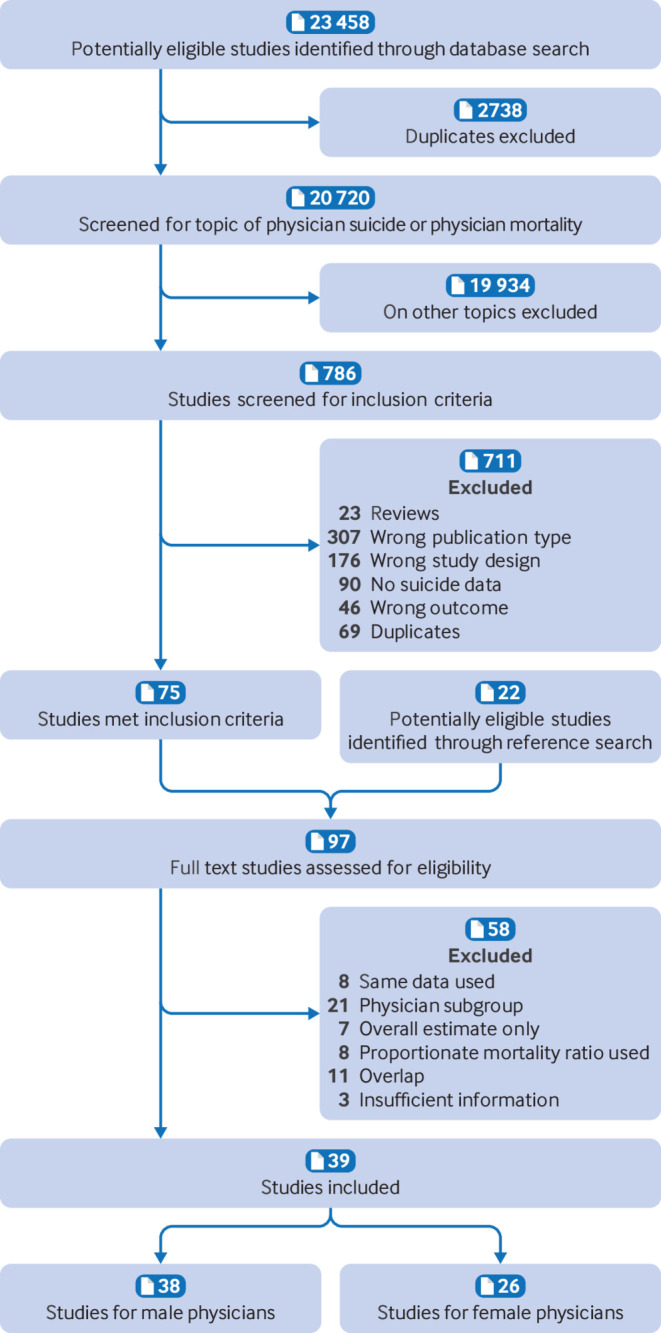

The initial literature search yielded 23 458 studies. After removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, we were left with 786 articles. Application of the inclusion criteria resulted in 75 reports and we found a further 22 potentially eligible studies through reference list and registry based searches. Full text screening resulted in 38 studies for male physicians and 26 for female physicians that were eligible for analyses (fig 1). Because a few studies provided more than one effect estimate,21 22 a total of 42 datasets (male physicians) and 27 datasets (female physicians) were used for meta-analysis (table 1 and table 2).

Fig 1.

Flowchart showing study selection

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies on male physicians

| Study | Location | Time period | Suicides | Effect (95% CI*) | Measure | R1 | R2 | O | E | SE† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lindhardt et al (1963)23 | Denmark | 1935-59 | 67 | 1.53 (1.18 to 1.94) | SMR‡ | — | — | 67 | 43.9 | 0.126 |

| Craig and Pitts (1968)24 | US | 1965-67 | 211 | 1.12 (0.98 to 1.29) | RR‡ | 38.3 | 34.1 | 211 | 187.9 | 0.070 |

| Dean (1969)25 | South Africa | 1960-66 | 22 | 1.26 (0.79 to 1.90) | SMR‡ | — | — | 22 | 17.5 | 0.225 |

| Rich and Pitts (1979)26 | US | 1967-72 | 544 | 1.03 (0.95 to 1.12) | RR‡ | 35.7 | 34.6 | 544 | 528.7 | 0.043 |

| Balogh (1981)27 | Hungary | 1960-64 | 35 | 1.01 (0.70 to 1.40) | SRR‡ | 55.0 | 54.6 | 35 | 34.8 | 0.176 |

| Enstrom (1983)28¶ | California, US | 1950-59 | 54 | 1.82 (1.37 to 2.38) | SMR | — | — | 54 | 29.7 | 0.141 |

| Revicki and May (1985)29 | North Carolina, US | 1978-82 | 13 | 1.20 (0.64 to 2.05) | SMR‡ | — | — | 13 | 10.9 | 0.298 |

| Bämayr and Feuerlein (1986)30 | Upper Bavaria, Germany | 1963-78 | 67 | 1.50 (1.16 to 1.91) | SMR‡ | — | — | 67 | 44.6 | 0.126 |

| OPCS England and Wales A (1986)21§ | England and Wales, UK | 1949-53 | 61 | 2.26 (1.73 to 2.90) | SMR | — | — | 61 | 27.0 | 0.132 |

| OPCS England and Wales B (1986)21§ | England and Wales, UK | 1959-63 | 65 | 1.76 (1.36 to 2.24) | SMR | — | — | 65 | 36.9 | 0.128 |

| OPCS England and Wales C (1986)21§ | England and Wales, UK | 1970-72 | 55 | 3.35 (2.52 to 4.36) | SMR | — | — | 55 | 16.4 | 0.140 |

| OPCS Great Britain (1986)21§ | Great Britain, UK | 1979-83 (ex. 1981) | 65 | 1.72 (1.33 to 2.19) | SMR | — | — | 65 | 37.8 | 0.128 |

| Richings et al (1986)31¶ | England and Wales, UK | 1975 | 6 | 2.21 (0.81 to 4.81) | SMR | — | — | 6 | 2.7 | 0.454 |

| Arnetz et al (1987)32 | Sweden | 1961-70 | 32 | 1.20 (0.82 to 1.70) | SMR | — | — | 32 | 26.7 | 0.185 |

| Rimpelä et al (1987)33 | Finland | 1971-80 | 17 | 1.28 (0.75 to 2.05) | SRR‡ | — | — | 17 | 13.3 | 0.258 |

| Kono et al (1988)34 | Japan | 1973-83 | 3 | 0.15 (0.03 to 0.45) | SMR | — | — | 3 | 19.7 | 0.676 |

| Schlicht et al (1990)35 | Australia | 1950-86 | 10 | 1.13 (0.54 to 2.07) | SMR | — | — | 10 | 8.9 | 0.343 |

| Stefansson and Wicks (1991)17¶ | Sweden | 1971-85 (ex. 1980) | 113 | 2.03 (1.68 to 2.44) | SRR‡ | 80.7 | 39.7 | 113 | 55.6 | 0.096 |

| Shima et al (1992)36¶ | Chiba prefecture, Japan | 1984-88 | 2 | 0.36 (0.04 to 1.30) | SMR | — | — | 2 | 5.6 | 0.866 |

| Herner (1993)37 | Sweden | 1989-91 | 17 | 1.10 (0.64 to 1.76) | RR‡ | 45 | 40.9 | 17 | 15.5 | 0.258 |

| Lindeman et al (1997)38 | Finland | 1986-93 | 35 | 0.90 (0.63 to 1.25) | SMR | — | — | 35 | 38.9 | 0.176 |

| Rafnsson and Gunnarsdottir (1998)39 | Iceland | 1951-95 | 7 | 1.01 (0.41 to 2.08) | SMR‡ | — | — | 7 | 6.9 | 0.417 |

| Juel et al (1999)40 | Denmark | 1973-92 | 168 | 1.64 (1.40 to 1.91) | SMR | — | — | 168 | 102.4 | 0.079 |

| Hawton et al (2001)41 | England and Wales, UK | 1991-95 | 42 | 0.67 (0.48 to 0.90) | SMR | — | — | 42 | 62.9 | 0.160 |

| Hostettler and Minder (2002)42 | Switzerland | 1979-92 | 39 | 1.48 (1.05 to 2.02) | SMR | — | — | 39 | 26.4 | 0.167 |

| Innos et al (2002)43 | Estonia | 1983-98 | 6 | 0.58 (0.21 to 1.26) | SMR | — | — | 6 | 10.3 | 0.454 |

| Shin et al (2005)44 | South Korea | 1992-2002 | 43 | 0.51 (0.37 to 0.69) | SMR | — | — | 43 | 84.3 | 0.158 |

| Meltzer et al (2008)45 | England and Wales, UK | 2001-05 | 58 | 0.69 (0.52 to 0.89) | SMR | — | — | 58 | 84.1 | 0.136 |

| Petersen and Burnett (2008)46 | 26 states, US | 1984-92 | 181 | 0.80 (0.69 to 0.93) | SRR | — | — | 181 | 226.3 | 0.076 |

| Skegg et al (2010)47 | New Zealand | 1973-2004 (ex. 1996-97) | 25 | 0.60 (0.39 to 0.89) | SMR | — | — | 25 | 41.7 | 0.210 |

| Aasland et al (2011)48 49 | Norway | 1960-2000 | 98 | 1.77 (1.44 to 2.16) | SRR | — | — | 98 | 55.4 | 0.104 |

| Palhares-Alves et al (2015)50 | Sao Paolo, Brazil | 2000-09 | 38 | 0.65 (0.46 to 0.90) | RR‡ | 4.9 | 7.5 | 38 | 58.2 | 0.169 |

| Claessens (2016)51 | Flanders, Belgium | 2004-11 | 31 | 0.71 (0.48 to 1.01) | RR‡ | 25 | 35.1 | 31 | 43.5 | 0.188 |

| Davis et al A (2021)22§¶ | 16 states, US | 2007-08 | 66 | 0.86 (0.67 to 1.10) | RR‡ | 22.9 | 26.6 | 66 | 76.7 | 0.127 |

| Davis et al B (2021)22§¶ | 33-38 states, US | 2017-18 | 182 | 0.97 (0.83 to 1.12) | RR‡ | 31.5 | 32.6 | 182 | 188.4 | 0.075 |

| Gold et al (2021)52 | 27 states, US | 2010-15 | 307 | 0.86 (0.77 to 0.96) | SMR‡ | — | — | 307 | 356.6 | 0.058 |

| Ye et al (2021)53¶ | 32 states, US | 2016 | 110 | 0.70 (0.57 to 0.84) | SRR‡ | 20.71 | 29.73 | 110 | 157.9 | 0.098 |

| Herrero-Huertas et al (2022)54 | Spain | 2001-11 | 55 | 0.61 (0.46 to 0.80) | SRR‡ | — | — | 55 | 89.9 | 0.140 |

| FSO Switzerland, 2008-2055 56** | Switzerland | 2008-20 | 53 | 0.79 (0.60 to 1.04) | SMR‡ | — | — | 53 | 66.7 | 0.142 |

| ONS England, 2011-2057** | England, UK | 2011-20 | 112 | 0.58 (0.48 to 0.70) | SRR‡ | 10.85 | 18.65 | 112 | 192.5 | 0.097 |

| Petrie et al (2023)58 | Australia | 2001-17 | 90 | 0.97 (0.78 to 1.19) | SRR‡ | 15 | 15.5 | 90 | 93.0 | 0.108 |

| Zimmermann et al (2023)59 | Austria | 1998-2020 | 98 | 0.79 (0.64 to 0.96) | SMR | — | — | 147 | 198.6 | 0.104 |

E=expected number of suicides; O=observed number of suicides; R1=rate of physician target population; R2=rate of reference population; RR=rate ratio; SMR=standardised mortality ratio; SRR=standardised rate ratio.

Confidence intervals calculated by reviewers based on Fisher's exact test.60

Standard error calculated by reviewers with formula recommended by Cochrane handbook.12

Effect estimate calculated by reviewers.

Effect estimates for different time periods from same study.

Not all reported effect estimates from this study are included to avoid time period overlap with other studies from same location.

Unpublished.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies on female physicians

| Study | Location | Time period | Suicides | Effect (95% CI*) | Measure | R1 | R2 | O | E | SE† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Craig and Pitts (1968)24 | US | 1965-67 | 17 | 3.55 (2.07 to 5.69) | RR‡ | 40.5 | 11.4 | 17 | 4.8 | 0.258 |

| Pitts et al (1979)61 | US | 1967-72 | 49 | 3.57 (2.64 to 4.72) | RR‡ | 40.7 | 11.4 | 49 | 13.7 | 0.148 |

| Bämayr and Feuerlein (1986)30 | Upper Bavaria, Germany | 1963-78 | 27 | 3.21 (2.12 to 4.67) | SMR‡ | — | — | 27 | 8.4 | 0.202 |

| OPCS England and Wales (1986)21 | England and Wales, UK | 1979-83 (ex. 1981) | 14 | 3.10 (1.70 to 5.20) | SMR | — | — | 14 | 4.5 | 0.286 |

| Arnetz et al (1987)32 | Sweden | 1961-70 | 10 | 5.70 (2.74 to 10.51) | SMR | — | — | 10 | 1.8 | 0.343 |

| Stefansson and Wicks (1991)17¶ | Sweden | 1971-85 (ex. 1980) | 25 | 2.85 (1.85 to 4.21) | SRR‡ | 49.3 | 17.3 | 25 | 8.8 | 0.210 |

| Herner (1993)37 | Sweden | 1989-91 | 8 | 2.32 (1.00 to 4.57) | RR‡ | 39 | 16.8 | 8 | 3.4 | 0.387 |

| Lindeman et al (1997)38 | Finland | 1986-93 | 16 | 2.40 (1.37 to 3.90) | SMR | — | — | 16 | 6.7 | 0.266 |

| Juel et al (1999)40 | Denmark | 1973-92 | 26 | 1.68 (1.10 to 2.46) | SMR | — | — | 26 | 15.5 | 0.206 |

| Hawton et al (2001)41 | England and Wales, UK | 1991-95 | 15 | 2.02 (1.13 to 3.33) | SMR | — | — | 15 | 7.4 | 0.276 |

| Innos et al (2002)43 | Estonia | 1983-98 | 5 | 0.62 (0.20 to 1.45) | SMR | — | — | 5 | 8.1 | 0.503 |

| Shin et al (2005)44 | South Korea | 1992-2002 | 3 | 0.57 (0.12 to 1.67) | SMR | — | — | 3 | 5.3 | 0.676 |

| Meltzer et al (2008)45 | England and Wales, UK | 2001-05 | 25 | 1.52 (0.98 to 2.24) | SMR | — | — | 25 | 16.5 | 0.210 |

| Petersen and Burnett (2008)46 | 26 states, US | 1984-92 | 22 | 2.39 (1.50 to 3.62) | SRR | — | — | 22 | 9.2 | 0.225 |

| Skegg et al (2010)47 | New Zealand | 1973-2004 (ex. 1996-97) | 2 | 0.40 (0.05 to 1.45) | SMR | — | — | 2 | 5.0 | 0.866 |

| Aasland et al (2011)48 49 | Norway | 1960-2000 | 13 | 2.93 (1.56 to 5.01) | SRR | — | — | 13 | 4.4 | 0.298 |

| Palhares-Alves et al (2015)50 | Sao Paolo, Brazil | 2000-09 | 12 | 1.45 (0.75 to 2.53) | RR‡ | 2.9 | 2.0 | 12 | 8.3 | 0.311 |

| Claessens (2016)51 | Flanders, Belgium | 2004-11 | 10 | 1.68 (0.81 to 3.09) | RR‡ | 23.7 | 14.1 | 10 | 6.0 | 0.343 |

| Davis et al A (2021)22§¶ | 16 states, US | 2007-08 | 9 | 1.04 (0.48 to 1.98) | RR‡ | 7.2 | 6.9 | 9 | 8.6 | 0.363 |

| Davis et al B (2021)22§¶ | 33-38 states, US | 2017-18 | 39 | 1.17 (0.84 to 1.61) | RR‡ | 10.1 | 8.6 | 39 | 33.2 | 0.167 |

| Gold et al (2021)52 | 27 states, US | 2010-15 | 50 | 0.89 (0.66 to 1.17) | SMR‡ | — | — | 50 | 56.4 | 0.146 |

| Ye et al (2021)53¶ | 32 states, US | 2016 | 27 | 1.22 (0.81 to 1.78) | SRR‡ | 9.83 | 8.03 | 27 | 22.1 | 0.202 |

| Herrero-Huertas et al (2022)54 | Spain | 2001-11 | 16 | 0.84 (0.48 to 1.36) | SRR‡ | — | — | 16 | 19.0 | 0.266 |

| FSO Switzerland, 2008-202055 56** | Switzerland | 2008-20 | 17 | 1.23 (0.72 to 1.97) | SMR‡ | — | — | 17 | 13.8 | 0.258 |

| ONS England, 2011-202057** | England, UK | 2011-20 | 56 | 0.97 (0.74 to 1.26) | SRR‡ | 5.4 | 5.55 | 56 | 57.6 | 0.138 |

| Petrie et al (2023)58 | Australia | 2001-17 | 31 | 2.55 (1.73 to 3.62) | SRR‡ | 7.9 | 3.1 | 31 | 12.2 | 0.188 |

| Zimmermann et al (2023)59 | Austria | 1998-2020 | 43 | 1.55 (1.12 to 2.09) | SMR | — | — | 43 | 27.7 | 0.158 |

E=expected number of suicides; O=observed number of suicides; R1=rate of physician target population; R2=rate of reference population; RR=rate ratio; SMR=standardised mortality ratio; SRR=standardised rate ratio.

Confidence intervals calculated by reviewers based on Fisher's exact test.60

Standard error calculated by reviewers with formula recommended by Cochrane handbook.12

Effect estimate calculated by reviewers.

Effect estimates for different time periods from same study.

Not all reported effect estimates from this study are included to avoid time period overlap with other studies from same location.

Unpublished.

Meta-analyses

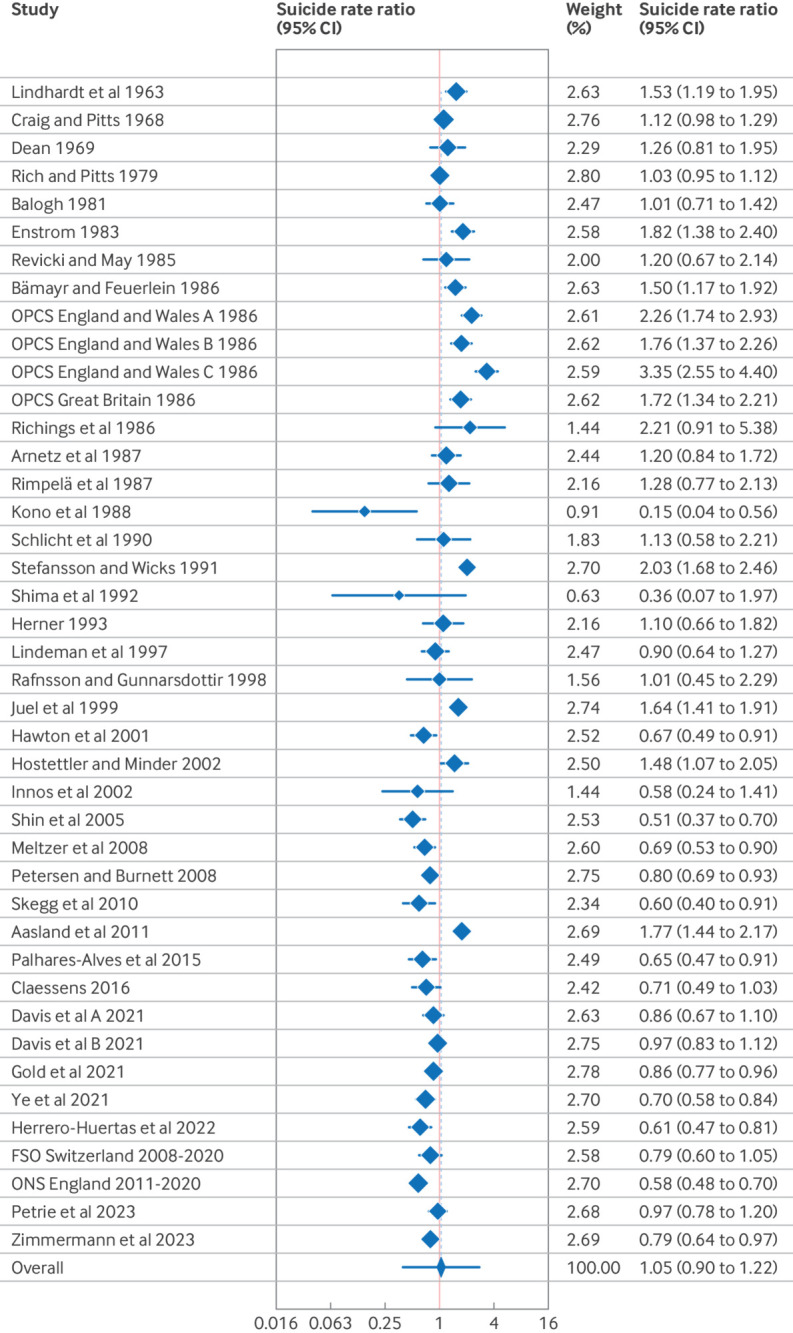

The meta-analysis on suicide deaths in male physicians (fig 2) produced a mean effect estimate of 1.05 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.22). The Q test was highly significant (Q=460.2, df=41, P<0.001), and the I2 of 94% indicated that a high proportion of variance in the observed effects was caused by heterogeneity in true effects compared with sampling error. The variance of true effect size estimated with T2 was 0.216, the standard deviation T was 0.465. The resulting prediction interval ranged from 0.41 to 2.72, which indicates that in 95% of all comparable future studies in male physician populations, the true effect size will fall in this interval. This finding reflects a high level of dispersion, suggesting that the suicide rates are decreased in some male physician populations but increased in others compared with the general population. Meta-regression confirmed calendar time (measured by midpoint of study observation period) as a highly significant covariate (β=−0.015, P<0.001), with an adjusted R2 indicating an explained proportion of 52% of between-study variance.

Fig 2.

Forest plot of suicide rate ratios for male physicians compared with general population

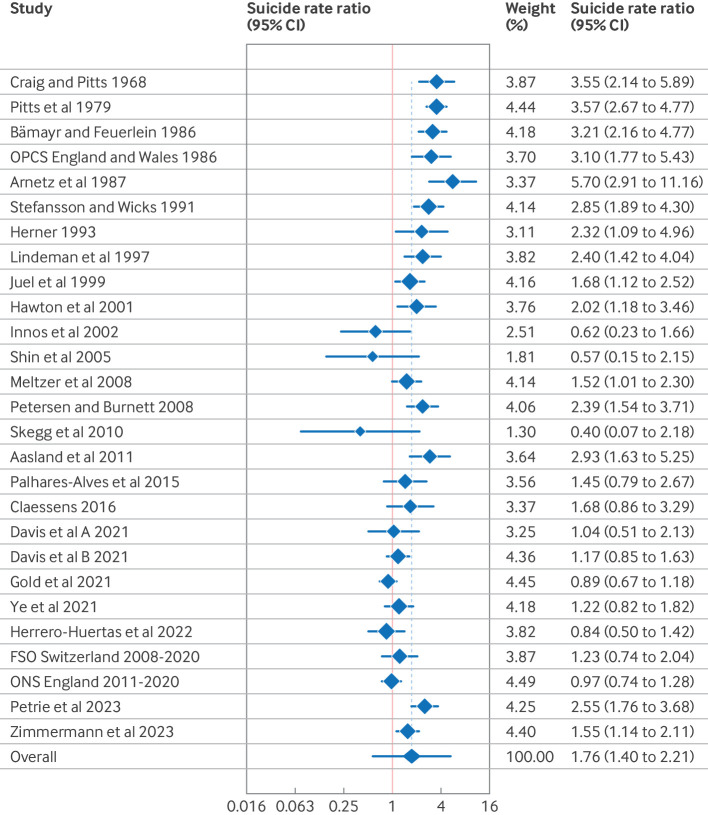

The mean effect estimate for suicide deaths in female physicians (fig 3) was 1.76 (95% CI 1.40 to 2.21). The Q test for heterogeneity was highly significant (Q=143.2, df=26, P<0.001), and the I2 of 84% indicated a high proportion of variance caused by heterogeneity in true effects, with T2 estimated at 0.278 and T at 0.523. The prediction interval ranged from 0.58 to 5.35, so the dispersion of the true effect size across studies on female physicians was also substantial, ranging from decreased suicide rates in some female physician populations to considerably increased rates in others. The midpoint of study observation period also showed a highly significant association with the pooled estimate in a meta-regression (β=−0.024, P<0.001), explaining 87% of between-study variance.

Fig 3.

Forest plot of suicide rate ratios for female physicians compared with general population

A decrease in suicide rate ratios over time is shown by cumulative meta-analyses (supplement figure S1a and S1b). A decline in pooled estimates is observed for female physicians throughout all studies, and a decline for studies with midpoints of observation period after 1985 can be seen for male physicians.

Further analyses

We performed sensitivity analyses across all studies using meta-regression. We did not observe any significant (P<0.01) results for male or female physicians, for study design, outcome measures, level of age standardisation, suicide classification, age range, reference group, length of observation period, and number of suicides. We found a significant association between risk of bias and effect size for male (β=−0.475, P=0.001) and female (β=−0.601, P=0.003) physicians, but when adjusting for midpoint of observation period, this association was no longer significant.

Egger test and Begg test gave no evidence of publication bias for studies on male or female physicians. The funnel plots showed no asymmetry, although they did reflect the high heterogeneity between studies (figure S2a and S2b). The non-parametric trim-and-fill analyses imputed no studies for male or female physicians, therefore no difference in effect size was found for observed versus observed plus imputed studies.

We also performed subgroup analyses based on geographical study location in two different categorisations: WHO world regions and most common study origin regions. With both analyses, the decrease in effect sizes over time was visible in most subgroups, and lower effect sizes were observed especially in studies from Asian countries (supplement figures S3a, S3b, S4a, and S4b). This finding translates to lower overall suicide rates for male physicians in the Western Pacific Region of 0.61 (95% CI 0.35 to 1.04), or similarly, for studies outside of Europe and the US with 0.69 (0.45 to 1.06). This pattern was not observed for female physicians, although the suicide rate ratio for the Western Pacific Region (1.06, 0.34 to 3.32) was also the lowest compared with all other subgroups.

Given that calendar time has been shown to have a strong association with effect size, we also performed a subgroup analysis of the 10 most recent studies versus all older studies. For male physicians (supplement figure S5a), the mean effect estimate in the subgroup of 32 older datasets was increased at 1.17 (0.96 to 1.41), whereas in the subgroup of the 10 most recent studies it was significantly decreased at 0.78 (0.70 to 0.88). For female physicians (supplement figure S5b), the mean suicide rate ratio in the subgroup of 17 older studies was significantly increased at 2.21 (1.63 to 3.01). In the subgroup of the 10 most recent studies, the mean effect was still significantly increased at a lower level of 1.24 (1.00 to 1.55).

Secondary meta-analysis

We conducted another meta-analysis on suicide rates in physicians compared with other professions of similar socioeconomic status and identified eight studies that compared male physicians with a reference group of other academics, other professionals, other health professionals, or members of social class I (supplement figure S6 and table S6). The pooled effect estimate was significantly increased at 1.81 (95% CI 1.55 to 2.12). The Q test (Q=17.6, df=7, P=0.01) was significant, but the I2 of 58% and the prediction interval of 1.15 to 2.87 indicated a lower level of heterogeneity compared with the main analysis, and a more similar effect size across studies. We found five studies on female physicians (supplement table S6). The results of these studies appeared similar to those for male physicians, but we deemed the number of eligible studies too low for a random effects meta-analysis.62

Discussion

In this meta-analysis summarising the available evidence on physician deaths by suicide, we found the rate ratio for female physicians to be significantly raised, but not for male physicians. This result confirmed our hypothesis that mean effect estimates would be lower than in a previous meta-analysis on the subject published in 2004.10 Calendar time was identified as a significant covariate in both analyses, indicating decreasing suicide rate ratios for physicians over time. The high level of heterogeneity in results from different studies suggests that suicide risk for male and female physicians is not consistent across various physician populations. Therefore, the pooled effect estimate is only of limited use in describing the overall suicide risk for physicians compared with the general population. In a secondary meta-analysis, the suicide rate ratio of male physicians was shown to be significantly raised when other professional groups with similar socioeconomic status were used as a reference group, with less heterogeneity across study results.

Strengths and limitations of this study

We did not impose any language restrictions on our search strategy so that relevant studies from different geographical regions were found. Consequently, we were able to include a large number of studies from 20 countries providing overall and recent summary estimates based on a complete assessment of the available evidence. This study also explored a range of covariates as potential causes for heterogeneity.

Several weaknesses should also be mentioned. Underreporting of suicide deaths might be more common for physicians compared with the general population,8 influencing ratios between those two populations in the original studies. Despite the large number of included reports, several geographical regions are still underrepresented in the available evidence, which limits the generalisability of findings.

Comparison with other studies

A systematic review on physician deaths by suicide included a meta-analysis of studies with observation periods between 1980 and 2015,11 but found only nine eligible studies (a third of which were already included in the first meta-analysis by Schernhammer and Colditz10). This analysis was also subject to some methodological limitations, such as using a potentially arbitrary starting point for study observation periods and not accounting for overlap between included studies (therefore counting some physician deaths by suicide twice). Another systematic review and meta-analysis on physician and healthcare worker deaths by suicide included only one new study compared with Schernhammer and Colditz10 and so did not provide an updated estimate.63 Additionally, this analysis included a large US study that reported increased proportionate mortality ratios, impacting the pooled estimate for male physicians towards showing an effect.

Meaning of the study

The results of this study suggest that across different physician populations, the suicide risk is decreasing compared with the general population, although it remains raised for female physicians. The causes of this decline are unknown, but several factors might play a part. The critical appraisal of the included studies indicated better study quality among more recent studies, which might have contributed to the decrease in effect sizes over time. Meta-regression results by Duarte and colleagues suggested that the decrease in suicide risk in male physicians was driven by a reduction in the rate of suicide deaths in physicians rather than an increase in suicide deaths in the population.11 This finding could mean that physicians have benefitted more from general or targeted suicide prevention efforts compared with the general population, which is testament to the repeated calls for more awareness and interventions to support the mental health of physicians.64 65 Furthermore, the proportion of female physicians has increased over recent decades, and the average proportion of female physicians across all OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries reached 50% in 2021.66 This change is likely to affect working conditions in a historically male dominated field that could be relevant to the mental health of workers. Some evidence exists that occupational gender composition affects the availability of workplace support and affective wellbeing, with higher support levels in mixed rather than male dominated occupations.67 68

It is important to note, however, that considerable heterogeneity exists in the suicide risk of different physician populations that is still partly unexplained. Working as a physician is probably associated with different risk and protective factors across diverse healthcare systems, as well as training and work environments. Additionally, prevailing attitudes and stigma about mental health and suicide could vary. Societal influences on suicide rates over time might affect physicians differently compared with the general population (eg, mental health stigma might differ for physicians compared with the general population, and change at a different rate). Therefore, it seems plausible that the relation between suicide deaths in physicians compared with the general population differs between regions and countries.

Policy implications

Overall, this study highlights the ongoing need for suicide prevention measures among physicians. We found evidence for increased suicide rates in female physicians compared with the general population, and for male physicians compared with other professionals. Additionally, the decreasing trend in suicide risk in physicians is not a universal phenomenon. An Australian study found a substantial increase in suicide risk for female physicians, which doubled between 2001 and 2017.58 The recent covid-19 pandemic has put additional strain on the mental health of physicians, potentially exacerbating risk factors for suicide such as depression and substance use.69 70 Other important risk factors include suicidal ideation and attempted suicide, and their prevalence among physicians was estimated by a recent meta-analysis. The results suggest higher levels of suicidal ideation among physicians compared with the general population, whereas the prevalence of suicide attempts appeared to be lower.71 This finding could indicate that suicidal intent in physicians is more likely to result in fatal rather than non-fatal suicidal behaviours.72 A systematic review on mental illness in physicians concluded that a coordinated range of mental health initiatives needs to be implemented at the individual and organisational level to create workplaces that support their mental health.73 Evidence exists for effective physician directed interventions, but hardly any research on organisational measures to address suicide risk in physicians.74 Continued advances in organisational strategies for the mental wellbeing of physicians are essential to support individual medical institutions in their efforts to foster supportive environments, combat gender discrimination, and integrate mental health awareness into medical education and training.

Recommendations for future research

In addition to more primary studies from world regions other than Europe, the US, and Australia, future research also needs to systematically look into other factors beyond study characteristics that might explain the heterogeneity in suicide risk in physicians. Such research would help in identifying physicians who are at risk, with targeted prevention measures and ways to adapt them to different clinical and cultural contexts. Because geographical or national differences appear to be important factors, future studies on suicide risk in physicians should bear in mind that the specific settings of any physician population might influence their risk and resilience factors to a much higher degree than previously assumed. Other major events that affect healthcare, such as the covid-19 pandemic, could also have a large impact. Future research is needed to assess any covid-19 related effects on suicide rates in physicians around the world.

What is already known on this topic

Many studies reported increased suicide rates for physicians, and a 2004 meta-analysis found significantly increased suicide rates for male and female physicians compared with the general population

Evidence on increased suicide rates for physicians is inconsistent across countries

What this study adds

Suicide rate ratios for physicians appear to have decreased over time, but are still increased for female physicians

A high level of heterogeneity exists across studies, suggesting that suicide risk varies among different physician populations

Further research is needed to identify physician populations and subgroups at higher risk of suicide

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support in developing the literature search strategy that was provided by the library staff at the Medical University of Vienna, and for the generous help with translations that was provided by a number of colleagues from within and outside of this institution. The authors also want to acknowledge the efforts undertaken by the Federal Statistics Office (Switzerland) and the Office for National Statistics (UK) to provide original data that were used in this analysis. Furthermore, the authors thank Eduardo Vega who reviewed the paper after submission as a member of the public, as well as Lena Hübl and Klaus Michael Fröhlich who provided their perspectives as physicians.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: Supplement

Contributors: CZ, SS, and ES conceived and designed the study, HH and TN contributed and advised on methodological aspects. CZ performed the literature search and was the first reviewer for article screening, data extraction, and risk of bias assessment. SS was the second reviewer for article screening, data extraction, and risk of bias assessment. CZ performed the statistical analyses and SS accessed and verified the underlying study data. CZ, SS, and ES interpreted the data. CZ drafted the manuscript and prepared tables and figures. All authors critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final version. ES supervised the study. CZ is the study guarantor. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This study was partially supported by the Vienna Anniversary Foundation for Higher Education (grant number H-303766/2019). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation, or in writing or submitting the report. The researchers were independent from the funder and all authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: CZ received partial funding from the Vienna Anniversary Foundation for Higher Education for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Transparency: The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as originally planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: The authors plan to disseminate the study findings through conference presentations, talks, press releases, social media, and in mandatory courses on mental wellbeing for medical students. The results will also be forwarded to national and international organisations that the authors have had contact with, to be disseminated both within these organisations and through their communication channels. This includes organisations in the field of mental health, public health, suicide prevention, and professional associations (for physicians and medical students); examples include the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, the International Association for Suicide Prevention and particularly its Special Interest Group on Suicide and the Workplace, the Canadian Medical Association, the Austrian Public Health Association, and the Austrian Medical Chamber. Discussions on how these findings might be used in local and national suicide prevention efforts in Austria will involve physicians, hospital administrators, mental and occupational health professionals, and interested members of the public who are affected by suicidality among physicians.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Ethical approval

Not required.

Data availability statement

Additional data are available from the corresponding author at eva.schernhammer@muv.ac.at upon request.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Suicide worldwide in 2019: global health estimates. Published online 2021. Accessed 12 Sep 2023. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240026643

- 2. Turecki G, Brent DA, Gunnell D, et al. Suicide and suicide risk. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019;5:74. 10.1038/s41572-019-0121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Agerbo E, Gunnell D, Bonde JP, Mortensen PB, Nordentoft M. Suicide and occupation: the impact of socio-economic, demographic and psychiatric differences. Psychol Med 2007;37:1131-40. 10.1017/S0033291707000487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lorant V, de Gelder R, Kapadia D, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in suicide in Europe: the widening gap. Br J Psychiatry 2018;212:356-61. 10.1192/bjp.2017.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Øien-Ødegaard C, Hauge LJ, Reneflot A. Marital status, educational attainment, and suicide risk: a Norwegian register-based population study. Popul Health Metr 2021;19:33. 10.1186/s12963-021-00263-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Milner A, Spittal MJ, Pirkis J, LaMontagne AD. Suicide by occupation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2013;203:409-16. 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.128405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Roberts SE, Jaremin B, Lloyd K. High-risk occupations for suicide. Psychol Med 2013;43:1231-40. 10.1017/S0033291712002024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Legha RK. A history of physician suicide in America. J Med Humanit 2012;33:219-44. 10.1007/s10912-012-9182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. JAMA . Suicides of physicians and the reasons. J Am Med Assoc 1903;41:263-4. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schernhammer ES, Colditz GA. Suicide rates among physicians: a quantitative and gender assessment (meta-analysis). Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:2295-302. 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Duarte D, El-Hagrassy MM, Couto TCE, Gurgel W, Fregni F, Correa H. Male and female physician suicidality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2020;77:587-97. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cochrane. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 6.3. Published 2022. Accessed 19 Jul 2023. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current

- 13. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000100. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deep L. DeepL Translator. Accessed 19 Jul 2023. https://www.DeepL.com/translator

- 15. Kim I, Lim HK, Kang HY, Khang YH. Comparison of three small-area mortality metrics according to urbanity in Korea: the standardized mortality ratio, comparative mortality figure, and life expectancy. Popul Health Metr 2020;18:3. 10.1186/s12963-020-00210-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Windsor-Shellard B. Suicide by Occupation, England: 2011 to 2015. Office for National Statistics; 2017. Accessed 17 Sep 2023. https://www.ons.gov.uk/releases/suicidesbyoccupationengland2011to2015

- 17. Stefansson CG, Wicks S. Health care occupations and suicide in Sweden 1961-1985. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1991;26:259-64. 10.1007/BF00789217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Chapter 5: Systematic reviews of prevalence and incidence. In: JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. 2020. Accessed 19 Jul 2023. https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools

- 19.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Wiley; 2021. https://www.google.at/books/edition/Introduction_to_Meta_Analysis/2oYmEAAAQBAJ

- 20. IntHout J, Ioannidis JP, Borm GF. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:25. 10.1186/1471-2288-14-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Office of Population Censuses and Surveys. Occupational Mortality 1979-80, 1982-83, Decennial Supplement, Part I+II. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office; 1986.

- 22. Davis MA, Cher BAY, Friese CR, Bynum JPW. Association of US nurse and physician occupation with risk of suicide. JAMA Psychiatry 2021;78:1-8. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lindhardt M, Frandsen E, Hamtoft H, Mosbech J. Causes of death among the medical profession in Denmark. Dan Med Bull 1963;(10):59-64. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Craig AG, Pitts FN, Jr. Suicide by physicians. Dis Nerv Syst 1968;29:763-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dean G. The causes of death of South African doctors and dentists. Afr Med J. Published online 1969. [PubMed]

- 26. Rich CL, Pitts FN, Jr. Suicide by male physicians during a five-year period. Am J Psychiatry 1979;136:1089-90. 10.1176/ajp.136.8.1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Balogh J. Mortality of medical men in the Hungary (1960-1964). Sante Publique (Bucur) 1981;24:41-60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Enstrom JE. Trends in mortality among California physicians after giving up smoking: 1950-79. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983;286:1101-5. 10.1136/bmj.286.6371.1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Revicki DA, May HJ. Physician suicide in North Carolina. South Med J 1985;78:1205-7. 10.1097/00007611-198510000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bamayr A, Feuerlein W. [Incidence of suicide in physicians and dentists in Upper Bavaria]. Soc Psychiatry 1986;21:39-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Richings JC, Khara GS, McDowell M. Suicide in young doctors. Br J Psychiatry 1986;149:475-8. 10.1192/bjp.149.4.475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Arnetz BB, Hörte LG, Hedberg A, Theorell T, Allander E, Malker H. Suicide patterns among physicians related to other academics as well as to the general population. Results from a national long-term prospective study and a retrospective study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1987;75:139-43. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb02765.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rimpelä AH, Nurminen MM, Pulkkinen PO, Rimpelä MK, Valkonen T. Mortality of doctors: do doctors benefit from their medical knowledge? Lancet 1987;1:84-6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(87)91919-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kono S, Ikeda M, Tokudome S, Nishizumi M, Kuratsune M. Cause-specific mortality among male Japanese physicians: a cohort study. Asian Med J 1988;31:453-61. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schlicht SM, Gordon IR, Ball JR, Christie DG. Suicide and related deaths in Victorian doctors. Med J Aust 1990;153:518-21. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1990.tb126190.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shima M, Nitta Y, Iwasaki A, Adachi M, Yoshii I. [A study of mortality among male physicians in Chiba prefecture]. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 1992;39:139-46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Herner B. [High frequency of suicide among younger physicians. Unsatisfactory working situations should be dealt with]. Lakartidningen 1993;90:3449-52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lindeman S, Läärä E, Hirvonen J, Lönnqvist J. Suicide mortality among medical doctors in Finland: are females more prone to suicide than their male colleagues? Psychol Med 1997;27:1219-22. 10.1017/S0033291796004680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rafnsson V, Gunnarsdottir HK. [Mortality and cancer incidence among physicians and lawyers]. Laeknabladid 1998;84:107-15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Juel K, Mosbech J, Hansen ES. Mortality and causes of death among Danish medical doctors 1973-1992. Int J Epidemiol 1999;28:456-60. 10.1093/ije/28.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hawton K, Clements A, Sakarovitch C, Simkin S, Deeks JJ. Suicide in doctors: a study of risk according to gender, seniority and specialty in medical practitioners in England and Wales, 1979-1995. J Epidemiol Community Health 2001;55:296-300. 10.1136/jech.55.5.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hostettler M, Minder C. [Mortality of Swiss dentists]. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed 2002;112:456-62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Innos K, Rahu K, Baburin A, Rahu M. Cancer incidence and cause-specific mortality in male and female physicians: a cohort study in Estonia. Scand J Public Health 2002;30:133-40. 10.1177/14034948020300020701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shin YC, Kang JH, Kim CH. [Mortality among medical doctors based on the registered cause of death in Korea 1992-2002]. J Prev Med Public Health 2005;38:38-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Meltzer H, Griffiths C, Brock A, Rooney C, Jenkins R. Patterns of suicide by occupation in England and Wales: 2001-2005. Br J Psychiatry 2008;193:73-6. 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Petersen MR, Burnett CA. The suicide mortality of working physicians and dentists. Occup Med (Lond) 2008;58:25-9. 10.1093/occmed/kqm117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Skegg K, Firth H, Gray A, Cox B. Suicide by occupation: does access to means increase the risk? Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2010;44:429-34. 10.3109/00048670903487191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Aasland OG, Hem E, Haldorsen T, Ekeberg Ø. Mortality among Norwegian doctors 1960-2000. BMC Public Health 2011;11:173. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hem E, Haldorsen T, Aasland OG, Tyssen R, Vaglum P, Ekeberg O. Suicide rates according to education with a particular focus on physicians in Norway 1960-2000. Psychol Med 2005;35:873-80. 10.1017/S0033291704003344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Palhares-Alves HN, Palhares DM, Laranjeira R, Nogueira-Martins LA, Sanchez ZM. Suicide among physicians in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, across one decade. Braz J Psychiatry 2015;37:146-9. 10.1590/1516-4446-2014-1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Claessens H. Suïcide bij Vlaamse artsen. Huisarts Nu 2016;45:228-31. 10.1007/s40954-016-0081-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gold KJ, Schwenk TL, Sen A. Physician suicide in the United States: updated estimates from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Psychol Health Med 2022;27:1563-75. 10.1080/13548506.2021.1903053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ye GY, Davidson JE, Kim K, Zisook S. Physician death by suicide in the United States: 2012-2016. J Psychiatr Res 2021;134:158-65. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Herrero-Huertas L, Andérica E, Belza MJ, Ronda E, Barrio G, Regidor E. Avoidable mortality for causes amenable to medical care and suicide in physicians in Spain. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2022;95:1147-55. 10.1007/s00420-021-01813-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.FSO (Federal Statistics Office) Switzerland. Data request for physician suicide data. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home.html

- 56.FMH (Foederatio Medicorum Helveticorum). Online-tool for the physician statistics of the Swiss Medical Association (FMH), data for 2008-2020. https://aerztestatistik.fmh.ch/

- 57.ONS (Office for National Statistics) UK. Suicide by Occupation in England: 2011 to 2015 and 2016 to 2020. Published 2021. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/adhocs/13768suicidebyhealthcarerelatedoccupationsengland2011to2015and2016to2020registrations

- 58. Petrie K, Zeritis S, Phillips M, et al. Suicide among health professionals in Australia: a retrospective mortality study of trends over the last two decades. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2023;57:983-93. 10.1177/00048674221144263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zimmermann C, Strohmaier S, Niederkrotenthaler T, Thau K, Schernhammer E. Suicide mortality among physicians, dentists, veterinarians, and pharmacists as well as other high-skilled occupations in Austria from 1986 through 2020. Psychiatry Res 2023;323:115170. 10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rothman K, Boyce J. Epidemiologic Analysis with a Programmable Calculator. Vol NIH Publication No. 79-1649. National Institutes of Health; 1979. Accessed 13 Sep 2023. https://hero.epa.gov/hero/index.cfm/reference/details/reference_id/3978444

- 61. Pitts FN, Jr, Schuller AB, Rich CL, Pitts AF. Suicide among U.S. women physicians, 1967-1972. Am J Psychiatry 1979;136:694-6. 10.1176/ajp.136.5.694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Guolo A, Varin C. Random-effects meta-analysis: the number of studies matters. Stat Methods Med Res 2017;26:1500-18. 10.1177/0962280215583568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dutheil F, Aubert C, Pereira B, et al. Suicide among physicians and health-care workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2019;14:e0226361. 10.1371/journal.pone.0226361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Center C, Davis M, Detre T, et al. Confronting depression and suicide in physicians: a consensus statement. JAMA 2003;289:3161-6. 10.1001/jama.289.23.3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Goldman ML, Shah RN, Bernstein CA. Depression and suicide among physician trainees: recommendations for a national response. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:411-2. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.OECD. Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators. OECD Publ. Published online 2023. 10.1787/7a7afb35-en [DOI]

- 67. Taylor CJ. Occupational sex composition and the gendered availability of workplace support. Gend Soc 2010;24:189-212. 10.1177/0891243209359912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Qian Y, Fan W. Men and women at work: occupational gender composition and affective well-being in the United States. J Happiness Stud 2019;20:2077-99. 10.1007/s10902-018-0039-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Morawa E, Adler W, Schug C, et al. Depressive and anxiety symptoms in the course of the COVID-19 pandemic among physicians in hospitals: results of the longitudinal, multicenter VOICE-EgePan survey over two years. BMC Psychol 2023;11:327. 10.1186/s40359-023-01354-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Myran DT, Cantor N, Rhodes E, et al. Physician health care visits for mental health and substance use during the covid-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e2143160. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.43160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Dong M, Zhou FC, Xu SW, et al. Prevalence of suicide-related behaviors among physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2020;50:1264-75. 10.1111/sltb.12690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Frank E, Dingle AD. Self-reported depression and suicide attempts among U.S. women physicians. Am J Psychiatry. Published online 1999. Accessed 25 Jun 2018. https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/ajp.156.12.1887 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73. Harvey SB, Epstein RM, Glozier N, et al. Mental illness and suicide among physicians. Lancet 2021;398:920-30. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01596-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Petrie K, Crawford J, Baker STE, et al. Interventions to reduce symptoms of common mental disorders and suicidal ideation in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2019;6:225-34. 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30509-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Supplement

Data Availability Statement

Additional data are available from the corresponding author at eva.schernhammer@muv.ac.at upon request.