Abstract

Background

Despite disproportionate rates of mental ill-health compared with non-Indigenous populations, few programs have been tailored to the unique health, social, and cultural needs and preferences of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males. This paper describes the process of culturally adapting the US-based Young Black Men, Masculinities, and Mental Health (YBMen) Project to suit the needs, preferences, culture, and circumstances of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males aged 16–25 years in the Northern Territory, Australia. YBMen is an evidence-based social media-based education and support program designed to promote mental health, expand understandings of gender and cultural identities, and enhance social support in college-aged Black men.

Methods

Our adaptation followed an Extended Stages of Cultural Adaptation model. First, we established a rationale for adaptation that included assessing the appropriateness of YBMen’s core components for the target population. We then investigated important and appropriate models to underpin the adapted program and conducted a non-linear, iterative process of gathering information from key sources, including young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males, to inform program curriculum and delivery.

Results

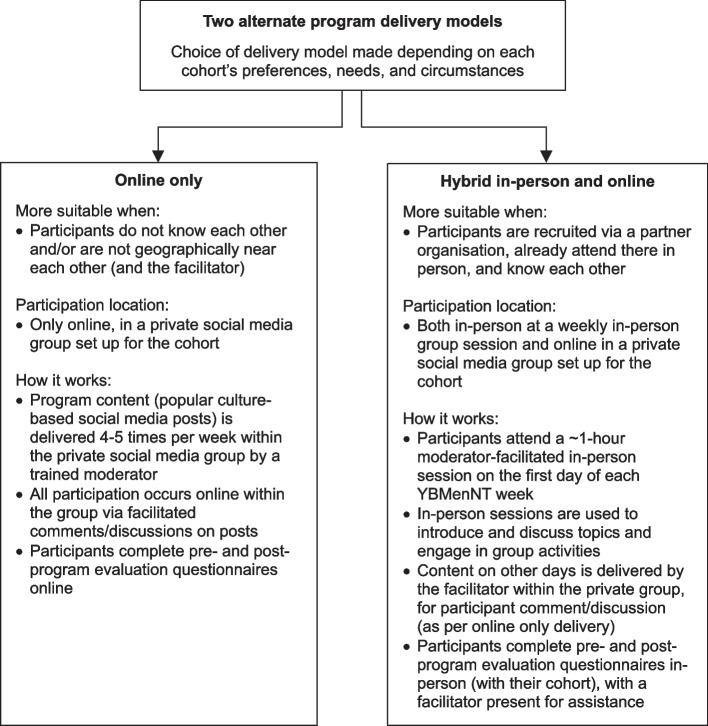

To maintain program fidelity, we retained the core curriculum components of mental health, healthy masculinities, and social connection and kept the small cohort, private social media group delivery but developed two models: ‘online only’ (the original online delivery format) and ‘hybrid in-person/online’ (combining online delivery with weekly in-person group sessions). Adaptations made included using an overarching Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional wellbeing framework and socio-cultural strengths-based approach; inclusion of modules on health and wellbeing, positive Indigenous masculinities, and respectful relationships; use of Indigenous designs and colours; and prominent placement of images of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male sportspeople, musicians, activists, and local role models.

Conclusions

This process resulted in a culturally responsive mental health, masculinities, and social support health promotion program for young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males. Next steps will involve pilot testing to investigate the adapted program’s acceptability and feasibility and inform further refinement. Keywords: Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, Indigenous, Australia, male, cultural adaptation, social media, mental health, masculinities, social support.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12939-024-02253-w.

Background

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, the Indigenous peoples of Australia, make up 4% of the Australian population [1]. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are not a homogenous group, comprising hundreds of diverse and distinct groups and nations, each with their own language, history, culture, beliefs, and practices [2]. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures were established and strong for tens of thousands of years before colonisation, with sophisticated spiritual and intellectual connections with land, seas, skies, and waterways, language, laws, lore, customs, and ceremony, educational systems, intricate family, kinship, and societal systems, and effective, harmonious methods for understanding, living on, and nurturing Country [3, 4]. The colonisation of Australia and associated forced displacement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people from their homelands, genocide and slavery, destruction of families, communities, and cultural practices, introduction of addictive substances, and ongoing discrimination, disadvantage, exclusion, and intergenerational trauma, have had, and continue to have, devastating impacts on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s health and wellbeing [5, 6]. Colonialism is rooted in control and influence over others and is a structural determinant of health that intersects with traumatic experiences including discrimination and racism, resulting in adverse outcomes including mental ill-health, poor physical health, substance misuse, and suicidality [7]. However, despite facing a myriad of health and wellbeing concerns, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people show strength and resilience through their Indigenous identities, spirituality, and longstanding connection to culture, values, practices, beliefs, and Country. This is evident in Australia through their exceptional leadership, sovereign positioning, cultural continuity, and commitment to self-determination [4, 8].

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males in particular experience many of the poorest health and wellbeing outcomes and greatest marginalisation of any population group in Australia [9–12], including disproportionately high rates of distress, mental ill-health, self-harm, death by suicide, substance misuse, and incarceration [13–18]. The project described in this paper is focused on older teen and young adult Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males living in the Northern Territory (NT), Australia. The NT is a vast and sparsely populated territory (18% of Australia’s landmass and 1% of the population) in central northern Australia [19, 20]. Almost one-third of the NT population is Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, and approximately ten percent of the NT Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population are young males aged 15 to 24 years [1]. This group experiences particularly high rates of mental ill-health, with a 2.4 times higher rate of hospitalisation for mental health reasons [21] and three times higher rate of death by suicide [22] than their non-Indigenous counterparts. While it is necessary to acknowledge these statistics, discussions of the health and wellbeing of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males often get stuck on disparities and disadvantage. Rather than staying focused only on what is wrong, it is absolutely vital that we move forward by developing innovative programs that work to support the health and wellbeing of this population. Development of such programs must take into account the complex array of reasons why young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males may not engage with health promoting strategies and services, including personal and community experiences of stereotyping and racism in health settings [23], lack of trusted, culturally suitable, and accessible assistance [24], and intergenerational stigma and shame about accessing healthcare, particularly for mental ill-health [25, 26]. Mainstream mental health programs often do not meet Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s needs due to their individualistic approach, use of western conceptualisations of health, and lack of recognition of the unique factors impacting the mental health and social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [27].

A variety of culturally informed, co-designed health promotion programs conducted in a variety of settings (e.g., [28–31]), including several designed for males [32, 33], have demonstrated positive impacts for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s mental health and wellbeing. However, few health promotion programs have been specifically designed to meet the unique health, social, and cultural needs, preferences, and circumstances of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males [34, 35]. There is little evidence on effective approaches to developing programs for populations based on three-way intersections of gender (e.g., male) and age (e.g., young) and culture (e.g., Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander), or frameworks to advance such approaches [34, 36, 37]. Culturally responsive, age appropriate, and gender specific health promotion efforts that centre Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture, facilitate appropriate and acceptable high-quality health promotion, and privilege and promote the strengths of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males are needed [34, 38]. Doing so effectively will need alignment between the community and cultural concepts and needs [39–41] and should draw on the knowledge and lived experiences of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males to develop programs that are acceptable, accessible, and effective for this often marginalised population [42]. Interventions must align with the needs and preferences of the specific target population to increase program acceptability and effectiveness [42], and there is potential for adverse outcomes from the use of culturally inappropriate health interventions. Perera et al. [43] note “at its best, failure to culturally adapt a psychological intervention could lead to inefficient use of scarce resources; at worst it could cause harm” (p. 12). These harms include the potential for non-engagement or premature discontinuation, poor physical or mental health outcomes, and increased mistrust in and reduced likelihood of future engagement with health interventions and systems [43].

Cultural adaptation is the process of systematically modifying an existing evidence-based program to make it more compatible with a different population’s culture, context, circumstances, patterns, meanings, and values [44]. Changes might be made to the program’s language, metaphors, content, concepts, goals, methods, and context to meet this aim [45], and more broadly, to increase the acceptability and effectiveness of the program for the population. Cultural adaptations may provide an avenue to develop programs that address the specific mental health and wellbeing needs of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males. A number of mental health and wellbeing focused programs have previously been culturally adapted for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations, with those adaptations demonstrating a range of positive outcomes [27, 46–48]. Meta-analytic evidence also supports the use of culturally adapted mental health interventions [49, 50], though this has not been specifically investigated in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander or Indigenous populations to date. Adaptation of an existing intervention may also have advantages in terms of reduced cost and time burden compared to developing a new intervention, increased efficiency of program development, and evidence to support the original program’s effectiveness [51]. However, there are diverse perspectives on the value of adapting evidence-based programs for Indigenous peoples, with some favouring co-designing new interventions from the ground up to ensure that Indigenous ways of being, knowing, and doing are centred (e.g., using ‘wise practices’ methods [52]), rather than adapting programs that have their basis and evidence base in non-Indigenous populations [53, 54].

This paper describes the process of culturally adapting the US-based Young Black Men, Masculinities, and Mental Health (YBMen) Project for use by young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males aged 16 to 25 years in the NT. YBMen was developed in 2014 as a mental health and progressive masculinities education and support program for young (college-aged) Black men in the US. It has been trialled with over 150 participants [55]. YBMen aims to use a culturally responsive, age appropriate, and gender sensitive approach to engaging young Black men in discussions on culturally sensitive and potentially stigmatising topics. The program is conducted with small cohorts of participants in a private social media group setting. It typically runs for six weeks, with each week focusing on a different topic (e.g., mental health). The program aims to educate young Black men about mental health, foster progressive and inclusive definitions of manhood, and develop social support. A trained facilitator moderates the group by posting daily engaging content (e.g., lyrics, YouTube videos, news headlines) related to the current topic and encouraging discussion focused on group problem solving, action-focused goal setting, and individual decision making [55–57]. Simultaneous to this Australian-based adaptation, YBMen is also being adapted (by a separate team) for African, Caribbean, and Black males aged 16–30 who have experienced the murder of family members and/or friends, within five neighbourhoods disproportionately impacted by homicide in Toronto, Canada (the RISE YBMen Toronto project) [58].

A number of previous papers have provided in-depth accounts of conducting cultural adaptations (e.g., [59–63]), including several on Indigenous led cultural adaptations (e.g., [64–66]), This information is important for increasing knowledge about cultural adaptations and adaptation processes, and for understanding relationships between adaptations, processes, and intervention outcomes [67]. However, documentation of the processes of cultural adaptation is frequently poor [68], and there is a dearth of literature detailing mental health intervention adaptations [43] and cultural adaptations targeting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations. Accounts of these cultural adaptations will assist in building the evidence base for these types of programs. As such, this paper describes the processes undertaken to culturally adapt the YBMen program to suit young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males in the NT (referred to as the YBMenNT project).

Methods

Development of the project

The YBMenNT project emerged out of iterative discussions with local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men over many years. The importance of addressing youth, health literacy, mental health, and social and emotional wellbeing issues was identified during a NT Indigenous Male Research Strategy Think Tank held in Darwin in 2016 [69–71]. This resulted in a collaboration between local Indigenous men’s health experts and non-Indigenous men’s health and health promotion academics on a project focused on understanding health literacy among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males from the Top End of the NT. This involved a combination of yarning sessions and a novel social media methodology to better understand the perspectives of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men. Findings from this project identified that there were no culturally relevant programs in the NT or Australia to help young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men navigate intersections between cultural identity, mateship, manhood, and their social and emotional wellbeing [34, 37, 72]. The closest example that could be found globally was the YBMen program, developed for African American College men in the US. While there was a clear understanding that the cultural and socio-political contexts are different between Australia and the US, and between African American and Indigenous people, the underpinning social and cultural determinants that impact on boys and young men of colour are very similar [73]. Through processes including iterative conversations with the founder of YBMen (DCW) and a visit to the US to learn more about YBMen as part of a Fulbright Award (JAS), an international, interdisciplinary research collaboration was formed, inclusive of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men in the NT, and a successful funding application was developed to adapt YBMen to YBMenNT. The project has also provided an opportunity to work with local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander controlled organisations including Indigenous Allied Health Australia (IAHA) and One Percent Program through the program adaptation and implementation phases. This has created a context of international research collaboration, cross-cultural learning, Indigenous research capacity building, and encouraged a foundation of sharing and reciprocity that is highly valued by our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers, program staff and program participants.

Reporting framework

The reporting of this paper is guided by the Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications – Expanded (FRAME) by Wiltsey Stirman, Baumann, and Miller [67]. FRAME includes items about: (1) the process, including when the modification occurred, whether adaptations were planned, and who participated; (2) the adaptation, including what was modified and the type or nature of the modifications; and (3) rationale for the adaptation, including goals and reasons for the adaptation. The completed FRAME checklist for this study is included as Supplementary File 1.

Ethics and consent

This research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was provided by the Menzies School of Health Research Human Research Ethics Committee in February 2022 (HREC-2021-4187). The work described in this paper was completed in March 2024. All participants provided written informed consent to participate.

Framework for the cultural adaptation

This project followed the Extended Stages of Cultural Adaptation model by Marshall et al. [74]. This model added an initial step of justifying the cultural adaptation to a five-part model by Barrera et al. [75]. The extended model consists of six linear stages:

Stage 1: Initial considerations – establish rationale for cultural adaptation and critically assess program core components.

Stage 2: Information gathering – review literature and consult key stakeholders.

Stage 3: Preliminary cultural adaptation – conduct adaptation based on findings of Stages 1 and 2.

Stage 4: Test preliminary design – small scale trial to assess feasibility and acceptability.

Stage 5: Refinements – further refine the program based on the findings of Stage 4.

Stage 6: Effectiveness trial – trial of refined culturally adapted program to assess outcomes.

This paper describes the work undertaken in Stages 1–3; subsequent stages will be reported in future papers.

Procedure

In Stage 1, we sought to establish a rationale for the cultural adaptation of the YBMen program for use by and with young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males, critically assessing the suitability and applicability of the program’s core components – its online private group delivery, and foci on mental health, social connection, and healthy masculinities – for this population and context.

At Stage 2, we collected information to guide the adaptation from a variety of essential sources. We sought literature on appropriate frameworks to underpin the adapted program, and guidance from key informants about the program content and format. This data collection was achieved iteratively, using a variety of approaches including group discussions, yarning sessions, individual conversations, and targeted expert advice. Our information-gathering processes were grounded in consultative and co-design activities undertaken with young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males from the NT and key representatives from our partner organisation, who are experts in engaging and working with young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males. The processes used to gather data from our key informants were non-linear and iterative. The research team was responsive to the information gathered from consultation activities. Opinions and knowledge gained from initial discussions informed subsequent discussions and helped identify additional stakeholders to consult. In this way, we sought a wide range of expert knowledge, opinions, and suggestions, aiming to garner a non-reductive accord on important adaptations to make to YBMen in order for the program to suit the needs, circumstances, and preferences of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males.

The data generation and gathering processes utilised were:

Discussions among the research team and expert Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advisory Group.

Non-directive guidance from the US YBMen team on their experiences of developing engaging program content and successful program delivery with young Black men in the US.

Multiple, informal discussions with key representatives from our partner organisation about appropriate program content and delivery format.

A local yarning session (led by CP, JB, JAS, GO) with a group of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males, recruited via the partner organisation, about their interests and preferences for program topics and delivery format. Some of these participants had further iterative conversations with YBMenNT project staff about adaptation considerations following the initial yarning session.

A yarning session (led by CP, JB, JAS) with key local service providers involved in engaging young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males about their health and wellbeing.

In Stage 3, data from the first two stages were used to develop the preliminary YBMenNT project. CP drafted the initial version of the culturally adapted YBMenNT program, which was later expanded and revised by JV and DR. This process was intentionally led by young Indigenous males (all < 25 years old).

Situating the research

While this project may have broader implications, it is important to ground this research in its place and context [76]. The NT has around 250,000 residents, approximately 76,000 of whom are Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander [1]. This project was focused on young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males living on Larrakia land, in and around Garramilla (Darwin), the capital city of the NT. The Larrakia people are the Traditional Owners and custodians of the land and waters of the Garramilla region. They have lived on and cared for the earth, seas, and waterways of the area for many thousands of years and continue to have a rich and vibrant culture [77]. While the Larrakia people are the Indigenous people of this area, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people from many different groups and nations live in and around Garramilla.

The research team

The YBMenNT project group is a collaborative, multidisciplinary team of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous researchers with expertise in areas including developing and implementing men’s health promotion programs with young men of colour, masculinities and men’s mental health research, research on the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males and youth, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander higher education research. The project is co-led by KC (Wagadagam man from the Torres Strait) and JAS (non-Indigenous), both of whom have extensive experience in research related to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male mental health and wellbeing. A total of 11 Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander research and professional staff were directly involved in the work described in this paper (CP, CS, DA, JB, JPr, JV, KC, KJC, MMR, OB, PA), with further support and guidance provided at all stages by three additional male Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander expert advisors. An Aboriginal male health policy and advocacy expert with 25 + years working in the NT (JB) mentored and supervised young Aboriginal males working on the project. Our First Nations YBMenNT facilitators are JV and DR, both proud young Tiwi Islander (Aboriginal) men who are experienced in engaging young Indigenous males in health and wellbeing promotion. All team members guiding program facilitation and evaluation (JAS, JB, JV, DR, MJO) underwent training from a US YBMen team member (KM) on developing engaging content, participant safety, and effective program facilitation. The US YBMen team (DCW, KM) also provided expert overarching advice throughout the cultural adaptation.

Partner organisation

Evidence indicates that barriers to engaging young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males in health promoting programs may be reduced by engaging members of this population on their own terms, within their own communities, and in environments and settings in which they are already engaged, that align with their interests, and that are relevant to their lives [34, 37, 72, 78, 79]. For this reason, partnering with organisations that have established, trusting relationships with young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males in the NT is a crucial part of YBMenNT. IAHA, a national, member-based Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisation focused on allied health workforce development and support, joined as a YBMenNT project partner before the cultural adaptation process started. IAHA founded the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Academy, which uses an innovative, culture-centred, community-led learning model to deliver training and education to Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander high school students. The first Academy was established in Darwin in 2018 [80]. Several representatives and young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male students from IAHA acted as key stakeholders in the information gathering phase of this cultural adaptation (reported on later in this paper). The first cohort of YBMenNT participants is also expected to be recruited from the IAHA NT Academy student body.

Results

Stage 1: Establish rationale for the adaptation

In Stage 1, we established a rationale for adapting YBMen, assessing the appropriateness of the YBMen program’s core components for our target population.

Rationale for adapting YBMen

We examined the core components of, and evidence for, the original YBMen program. The social media small private group delivery and foci on mental health, social connection, and health-promoting masculinities are core components of YBMen, while the intervention length, additional topics, popular culture prompts, and choice of social media platform are adaptable to the target population’s needs, circumstances, and preferences [55]. This flexibility, along with favourable evaluations of YBMen showing reductions in depression symptoms and mental health stigma, increased mental health literacy and social support, and expanded masculine norms [55, 56], support the adaptation of this program.

Core component 1: Online private group delivery

Though a number of potential barriers to online health promotion with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations have been identified, including poor internet access, literacy and language concerns, and non-familiarity with social media [81], the private social media group delivery format of YBMen was considered advantageous for engaging young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males in a program designed to educate and stimulate discussion on potentially uncomfortable topics such as mental health. The high level of mobility of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males between remote, regional, and metropolitan areas of the NT [82, 83] has traditionally presented a major challenge for continuing and coordinated in-person health service provision and targeted health promotion action. However, young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the NT have a high level of smartphone ownership and digital engagement, with many having access to the technology needed to participate in digital health promotion activities [72, 84]. Online interventions can be an opportunity to provide structured, accessible, personalised, low-cost assistance [85] using technology that many young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are already highly engaged with for communication, learning, relaxation, and fun [84, 86]. This may also reduce many barriers that stop young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people from accessing in-person mental health and wellbeing assistance, including shame, stigma, and lack of accessible and appropriate face-to-face services [84, 87], and facilitate greater self-disclosure about potentially stigmatising topics such as mental health [85]. There is increasing evidence of high levels of acceptability for e-mental health programs among young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [84, 88, 89], with data demonstrating their enthusiasm toward using online mental health programs that have been designed to meet their particular needs, and belief that these types of programs can effectively deliver mental health information, combat stigma, and encourage help-seeking [84]. However, program-related factors shown to influence the acceptability of e-mental health for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – local production, culturally relevant content, graphics, and language, ease of use, and security and information sharing – must be considered in the development of new programs [81].

Core component 2: Focus on mental health and social connections

Alignment between the core YBMen foci on improving mental health and developing social support and the needs and circumstances of our target population were key to its selection. Young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males experience disproportionately high rates of mental health concerns and deaths by suicide [21, 22] and also report often feeling lonely and disconnected from others [84]. Conversely, high self-esteem, supportive close friendships, and engaging in positive social activities are associated with positive psychosocial functioning in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teens [90]. Strengthening identity (e.g., by spending time with others with shared culture, beliefs, and experiences) and increasing social connections (e.g., by yarning, sharing beliefs and history, and overcoming challenges as a group) have been identified as key elements of successful programs to improve mental health and emotional wellbeing in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male populations [91]. As such, YBMen’s core components of mental health and social support were deemed highly important for our target population. We considered this an important opportunity to develop a program that sought to address mental health and social connectedness in a culturally, gender, and age appropriate manner.

Core component 3: Promotion of healthy masculinities

Masculinities are an important social and cultural determinant of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male health and wellbeing that have received little attention [92]. Research indicates that young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males construct unique masculinities that both embrace and resist ‘traditional’ masculine norms such as strength, self-reliance, control, and dominance, with masculine beliefs and behaviours rooted in connections to Country, intergenerational learnings, and systems of kinship that are unique to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [34]. Culturally responsive programs are needed to engage with young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males’ unique masculine identities to promote progressive, health-promoting masculine norms. Nuanced approaches must incorporate positive Indigenous masculinities (including aspects such as role modelling of traditional knowledge, multilingualism, and adherence to traditional Indigenous worldviews) to ensure the development of culturally and situationally appropriate programs that address this group’s mental health and wellbeing needs [34, 36]. The importance of this work has been highlighted by Liddle et al. [36], who stated “without a comprehensive discussion of alternative, strengths-based Aboriginal masculinities there is little hope for improving mental health outcomes for Aboriginal men” (p. 5). As such, YBMen’s emphasis on progressive, health-enhancing masculinities and flexibility to deliver this content in a culturally responsive manner supported its adaptation for young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males.

Stage 2: Gather information to inform the adaptation

In Stage 2, we investigated the literature and consulted key informants to gather information that would inform our cultural adaptation of YBMen.

Use of an overarching social and emotional wellbeing framework

It was key that YBMenNT utilise mental health and wellbeing models that resonate with the target population. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander conceptualisations of health situate mental and physical health as lying within a broader social and emotional wellbeing framework, in which individual, family, and community wellbeing are shaped by experiences and expressions of connections to body, mind and emotions, family and kin, community, culture, country, and spirit, spirituality, and ancestors [41, 93]. Mental ill-health is generally considered distinct from, but overlapping and interacting with, social and emotional wellbeing and its underlying domains [41]. Inequities, stressors, and disadvantages such as unemployment, lack of accessible, appropriate health services, exposure to violence, trauma, and abuse, experiences of discrimination and racism, grief and loss, incarceration, and risky alcohol and substance use are risks to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ wellbeing [94]. At the same time, connection to Country, culture, spirituality and ancestry, kinship and community relationships, self-determination, community governance, cultural continuity, autonomy and empowerment, and having knowledge and pride in their own identity have been identified as protecting and buffering Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s social and emotional wellbeing [94, 95]. Variations in how mental health, mental illness, and social and emotional wellbeing are understood by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals, families, and communities [41] must also be considered in the development of programs to promote mental health and social and emotional wellbeing and build resilience, coping skills, and self-identity in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males.

Use of a sociocultural strengths-based approach

The health and wellbeing challenges commonly experienced by young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males must not be the dominant stories in efforts to improve these issues. As described by Fogarty et al. [8], discourses of deficit occur when programs “aimed at alleviating disadvantage become so mired in narratives of failure and inferiority that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people themselves are seen as the problem, and a reductionist and essentialising vision of what is possible becomes all pervasive” (p. 2). Deficit discourses focused on what is negative, deficient, or failing are themselves a barrier to improving health and wellbeing outcomes [96] and have failed to successfully address challenges faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [97]. As a result, alternate, strengths-based approaches to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wellbeing have garnered increasing attention [8]. In contrast to deficit approaches, strengths-based approaches explicitly recognise and seek to promote people’s capacities and capabilities. Strengths-informed research indicates that young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experience culture and connection to Elders, Country, and Community as central to fostering their own strength, resilience, and social and emotional wellbeing [96]. Sociocultural strengths approaches – which place less weight on capacities and capabilities as individual qualities, and more on their connection to social relations, collective practices, and Indigenous identities [98] – appear to align with young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander conceptions of social and emotional wellbeing. As such, an Indigenous-informed sociocultural strengths-based approach, accounting for the variety of protective and strengths-enhancing factors relevant to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing, being, and doing [99], was at the forefront of the adaptation. This was also consistent with previous health literacy-related research involving young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males from the Top End of the NT [34].

Data collection from key sources

Data from our expert Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advisory Group, young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males, and partner organisation representatives highlighted preferences for:

Use of an Indigenous-informed model of social and emotional wellbeing aligning with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives, rather than a narrower focus on mental health only;

Attention to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander masculinities;

Inclusion of content on fathering and fatherhood;

Opportunities to discuss the impacts of racism, policing, and safety in the NT;

Specific content on sport (including racism and masculinities in sport);

Photo, video, and musical prompts from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander talent and local identities;

Content focused on the important roles of Elders and intergenerational exchanges of information for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wellbeing;

Content and delivery format to be tailored for the circumstances and preferences of each individual cohort of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males.

There was also strong feedback from young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males that Instagram was their preferred social media platform for the program, over other potential options such as Facebook or TikTok.

Though data from Stage 1 supported the use of an online-based program for young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males, representatives from our partner organisation suggested that the online only delivery model of the original YBMen program was likely to result in reduced engagement for some participants. Instead, they proposed a ‘hybrid’ delivery model combining in-person and online program components, believing this would lead to better engagement with the program for some young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males.

Stage 3: Preliminary cultural adaptation

In the third stage of this process, data gathered in Stages 1 and 2 were used to develop the preliminary YBMenNT project. We sought to retain the key strengths and principles of the original program – its centring of positive masculinities, mental health, and social connection, use of popular culture prompts, and delivery via private social media group – while adapting the language, cultural references, specific prompts, visual design of posts, and additional program topics to suit young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males in the NT.

Delivery models

Following the recommendation of our partner organisation representatives, two alternate YBMenNT delivery models were developed: one ‘online only’ and one ‘hybrid in-person and online’ (see Fig. 1). It is envisaged that we will offer both of these models to future cohorts, depending on their wants, needs, and situation. Our online only delivery model follows the original YBMen program, with all participation anonymous and the entire program occurring online. All participants in a YBMenNT cohort will be invited into a private social media (e.g., Instagram) group, where facilitators post content relevant to the week’s topic (e.g., mental health) and all participant discussions occur. In the alternate hybrid delivery model, in-person sessions will be confidential but not anonymous, while the online components will remain anonymous. Participants and facilitators will gather as a group for approximately one hour on the first day of every YBMenNT program week. These in-person sessions will be used to introduce the week’s topic, allow for participant questions and initial relevant discussions, and engage in group activities relevant to the topic. Depending on the interests and preferences of the members of each cohort and availability of a suitable location, in-person sessions will also incorporate physical activities (e.g., boxing, basketball) and meditation/relaxation as a further means of promoting wellbeing and group connection. Subsequent days in each YBMenNT week will follow the ‘online only’ format, with all content posted to the cohort’s private social media group and all discussions occurring online. The hybrid delivery model is envisaged as potentially appropriate when (a) program participants are recruited via a specific partner organisation and attend that organisation on a regular day each week (e.g., for sport or education or recreation), and (b) the partner organisation is in a facilitator-accessible location.

Fig. 1.

The YBMenNT delivery models

Curriculum

We maintained fidelity to the core components of the original YBMen program by retaining the small cohort, private social media group delivery model and foci on promoting mental health, healthy masculinities, and social connection. Based on guidance from key informants, policies, and the literature, we used an overarching Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional wellbeing framework (rather than a culturally inappropriate focus on only mental health), and also took a socio-cultural strengths-based approach with posts emphasising the importance of connection to Elders, Country, Community, and Indigenous culture and identity for fostering the wellbeing of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males. As can be seen in the examples presented in Fig. 2, the YBMenNT program social media posts commonly used a black, red, and yellow (Aboriginal flag colours) colour theme with Indigenous designs as backgrounds. Images of prominent male Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander musical artists, sportspeople, activists, and local figures and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males engaged in traditional cultural activities (e.g., dance and ceremonies) were incorporated into many posts. Information and statistics were relevant to the specific population; for example, one post mentioned a number of different mental health and wellbeing services for young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the Darwin area, and another reported the proportion of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males in the NT who experience mental health difficulties. The first iteration of the pilot curriculum used the following sequence of topics: program introduction and orientation (week 1), health and wellbeing (week 2), manhood and Indigenous masculinities (week 3), respectful relationships (week 4), wellbeing and social support (week 5), revision and future planning (week 6). Further topics that had been suggested by key informants for inclusion in the program (including fathering, racism in sport, and policing and safety) that were not included in the first version may be incorporated into the curriculum to suit future participant cohort preferences, needs, and circumstances.

Fig. 2.

Example social media posts from the pilot culturally adapted YBMenNT curriculum

Discussion

This paper reported on the process of culturally adapting the established the US-based YBMen program, a social media-based intervention designed to promote mental health, healthy masculinities, and social support to college-aged Black men, for use with young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males in the NT, Australia. Following an Extended Stages of Cultural Adaptation model [74, 75], the steps we followed included: establishing a rationale for the cultural adaptation of the YBMen program; assessing the suitability of the program’s core components for the target population; reviewing the literature to identify important models to underlie the adaptation; and collecting data from our expert advisor group, young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males, and representatives from our organisational partner on engaging and culturally responsive program content and delivery models. Information collected in these steps then guided the subsequent cultural adaptation of the YBMen program to become the pilot YBMenNT program. This study contributes to the growing literature documenting processes and outcomes related to the cultural adaptation of evidence-based interventions.

There has been limited scholarship on effective ways to promote mental health and wellbeing specifically in young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males. Consideration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander conceptualisations of health and wellbeing and ways of being, knowing, and doing [99], intersections between gender, Indigenous masculinities, and culture [34], and diversity among young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males [100] will need to be at the forefront of work in this area. Use of strengths-based approaches that counter dominant deficit narratives [8], such as the Indigenous strengths-based theoretical framework by Prehn [101], should also be prioritised. This model seeks to “identify and amplify the diverse strengths inherent in Indigenous people” (p. 2) by promoting identification of strengths within six key principles: celebrate diversity, embrace growth, empower aspirations, foster self-determination and collaboration, utilise resources, and cultural grounding [92]. Co-designing programs with young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males from the target population is crucial for developing programs that are both acceptable and effective for this demographic [102]. Research indicates that young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males are often interested in their own health and wellbeing and are willing and able to engage in discussion on this topic when engaged in a gender sensitive, culturally responsive, and age-appropriate way [34, 55, 56]. Our data collection for this adaptation aligned with these findings, with young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males demonstrating willingness and ability to discuss their preferences for topics and prompts in a theoretical program.

Cultural adaptation and e-health may offer particular potential as avenues for developing health promotion programs that resonate with young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males. Meta-analytic evidence has found that using culturally adapted programs leads to better outcomes (medium effect) for individuals from ethnic and racial minorities when compared to use of the same, non-culturally adapted programs in the same populations [49]. Examination of culturally adapted e-mental health interventions reported high levels of user acceptability and a large positive effect across mental health outcomes when compared to control conditions [50]. In a systematic review focused on Indigenous populations, Li and Brar [103] reported that e-mental health approaches were acceptable and demonstrated promising outcomes, particularly when the programs used decolonising, culturally appropriate approaches. The single previous project that we are aware of that has sought to promote mental health and wellbeing in young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males also had an e-health focus and incorporated a cultural adaptation [46]. Stayin’ On Track used a co-designed website, text messages, and mood monitoring to promote mental health and wellbeing in young Aboriginal fathers aged 18–25 years, with the text messaging and mood tracker component culturally adapted from the earlier Australian SMS4Dads intervention [104]. Pilot results for Stayin’ On Track supported the program’s feasibility and acceptability and lend initial support for the use of culturally adapted and e-mental health interventions for young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males.

However, little is known about the impacts of culturally adapted and e-mental health programs for young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males, and concerns have been raised about cultural adaptations for Indigenous populations, including the possibility of Indigenous worldviews being secondary in adaptations of programs from non-Indigenous cultures, risks related to retaining ‘core components’ of programs that conflict with Indigenous values, norms, and beliefs, and challenges in accounting for the within-group heterogeneity of experiences, circumstances, viewpoints, needs, and preferences in Indigenous populations, which require investigation [53, 54]. Further evidence is clearly needed to understand the utility of both e-health and cultural adaptations as avenues for mental health and social and emotional wellbeing promotion for this population. We hope the next stage of the YBMenNT project, the pilot trial of the initial culturally adapted program, will add to the evidence base on the acceptability and feasibility of these types of programs for young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males.

Major strengths of this study were the use of an established adaptation framework and guidance on program content and delivery from important sources including young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males and partner organisation representatives who are experts in working with and engaging young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males. Our non-linear, iterative process of gathering data from key informants is both a strength and a weakness, as we did not follow a predetermined or sequential process. Instead, we often took information from one informant or group of informants to others for their thoughts on those ideas and preferences, continuing this process until saturation. In this way, our YBMenNT program frameworks, prompts, topics, and delivery models were developed and refined iteratively. We had planned to carry out further yarning sessions with additional groups of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males. However, a number of Indigenous-led education providers, charities, and sporting clubs that we approached either were unsuitable or declined to be involved in the study. Reasons for this included the boys attending the organisation not fitting the YBMenNT age criterion (too young) or not having access to mobile phones due to incarceration, and limited organisational capacity combined with existing participation in other programs. As such, we were unable to establish additional partnerships to facilitate further co-design prior to the first cohort of participants taking part in YBMenNT. We plan to conduct further yarning sessions with young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males after the first cohort of participants complete the program, to inform further improvements.

The next steps of the Extended Stages of Cultural Adaptation model [74, 75] are to pilot test the preliminary cultural adaptation to assess its feasibility and acceptability (Stage 4) and use these results to further refine the program curriculum and delivery (Stage 5), prior to conducting an effectiveness trial of the final program to assess outcomes (Stage 6). With a variety of potential combinations of program topics and two proposed delivery models, our pilot investigations may involve comparing different sequences of topics and delivery models to investigate their appropriate use and potential effectiveness. Stage 4 of this project commenced in March 2024 and will be reported in future papers.

Conclusions

Guided by the Expanded Stages of Cultural Adaptation model, we culturally adapted the US-based YBMen program for use with young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males in the NT. The pilot adapted YBMenNT program maintained the small cohort, private social media group delivery and mental health, masculinities, and social connection foci of the US YBMen program, but made adaptations including use of an overarching social and emotional framework; a sociocultural strengths-based approach with content emphasising connection to Elders, Country, Community, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and identities; prominent use of Indigenous colours and designs in social media posts; inclusion of images and videos of influential Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males (e.g., sportspeople, activists) and of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males engaged in traditional cultural activities (e.g., dance); incorporation of locally relevant data and information on local services; inclusion of modules on health and wellbeing, Indigenous masculinities, and respectful relationships; and added a second, alternative delivery model combining weekly in-person sessions with the original online delivery. Important questions about the feasibility and acceptability of this initial program for young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males will be investigated – and improvements made to the program as informed by those results – in a subsequent pilot study.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males and Expert Advisory Group members who willingly shared their knowledge and ideas to guide the development of the YBMenNT program. Thank you also to Uncle Dr. Richard Fejo, Larrakia Elder and Senior Elder on Campus at Flinders University (Darwin), for his generous advice regarding respectful and inclusive descriptions of Larrakia country and Garramilla. The authors wish to acknowledge and pay respect to the Larrakia people on whose lands this project was conducted; to all past, present, and future Traditional Custodians of Australia; and to the continuation of cultural, spiritual, and educational practices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Abbreviations

- FRAME

Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications – Expanded

- IAHA

Indigenous Allied Health Australia

- NT

Northern Territory

- YBMen

Young Black Men, Masculinities, and Mental Health Project

- YBMenNT

Young Black Men, Masculinities, and Mental Health in the Northern Territory Project

Authors’ contributions

DCW, GS, JAS, JV, KC, MMR, and PA acquired the project funding. BB, CS, CP, DA, DCW, DR, GO, GS, JP, JV, JAS, JP, JB, KJC, KFM, KC, MMR, MR, MJO, MJND, OB, and PA worked on conceptualising and planning out the study. BB, CP, DR, GO, JV, JAS, JB, KC, and MJO were involved in the data collection. BB, CP, JV, JAS, JB, and KC coordinated responsibility for the research planning and execution. GO facilitated recruitment of participants via the partner organisation. JAS and MJO visualised the data and wrote the original manuscript draft. BB, CS, CP, DA, DCW, DR, GO, GS, JP, JV, JAS, JP, JB, KJC, KFM, KC, MMR, MR, MJO, MJND, OB, and PA reviewed and edited the draft manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript. JAS and KC supervised the project.

Funding

This work was funded by a Movember Digital Social Connections Challenge grant. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation, article writing, or in the decision to submit this article for publication.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval for this project was granted by the Menzies School of Health Research Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC-2021–4187). All participants provided their written informed consent.

Competing interests

DCW created the YBMen project and holds substantial intellectual property in the program. The licence is owned by the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. The University of Michigan has been paid a licensing fee for DCW’s willingness to share YBMen project resources as part of the adaptation process. All other authors declare that they have no known competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Kootsy Canuto and James A. Smith joint senior authors.

Contributor Information

Kootsy Canuto, Email: kootsy.canuto@flinders.edu.au.

James A. Smith, Email: james.smith@flinders.edu.au

References

- 1.Australian Bureau of Statistics: Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians (June 2021). 2021.

- 2.Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Australia's first peoples. 2022. https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/australias-first-peoples.

- 3.Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture and history [https://vpsc.vic.gov.au/workforce-programs/aboriginal-cultural-capability-toolkit/aboriginal-culture-and-history/]

- 4.Woodward E, Hill R, Harkness P, Archer R. Our Knowledge Our Way in caring for Country: Indigenous-led approaches to strengthening and sharing our knowledge for land and sea management. NAILSMA and CSIRO; 2020.

- 5.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. 2015. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous-australians/indigenous-health-welfare-2015.

- 6.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health performance framework summary report 2023. Canberra: AIHW; 2023.

- 7.Smallwood RW, C., Power T, Usher K: Understanding the impact of historical trauma due to colonisation on the health and wellbeing of Indigenous young peoples: A systematic scoping review. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2021;31:59–68. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Fogarty W, Lovell M, Langenberg J, Heron MJ. Deficit discourse and strengths-based approaches: changing the narrative of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wellbeing. Melbourne: The Lowitja Institute; 2018.

- 9.Canuto K, Brown A, Wittert G, Harfield S. Understanding the utilisation of primary health care services by Indigenous men: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canuto K, Harfield S, Wittert G, Brown A. Listen, understand, collaborate: developing innovative strategies to improve health service utilisation by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2019;43:307–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health and Ageing. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander suicide prevention strategy. Canberra: Australian Government; 2013.

- 12.Prehn J, Ezzy D. Decolonising the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal men in Australia. J Sociol. 2020;56:151–66. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Corrective services, Australia (September quarter 2023). 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime-and-justice/corrective-services-australia/latest-release.

- 14.National Indigenous Australians Agency. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health performance framework: 2.16 Risky alcohol consumption. 2023. https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/Measures/2-16-Risky-alcohol-consumption.

- 15.National Indigenous Australians Agency. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health performance framework: 1.18 Social and emotional wellbeing. 2023. https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/1-18-social-emotional-wellbeing.

- 16.National Indigenous Australians Agency. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health performance framework: 2.17 Drug and other susbtance use including inhalants. 2023. https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/2-17-drug-other-substance-use-including-inhalants.

- 17.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Causes of death, Australia, 2021. 2021. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/causes-death/causes-death-australia/2020.

- 18.National Indigenous Australians Agency. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health performance framework, Data tables: 3.10 Access to mental health services. 2023. https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/3-10-access-mental-health-services.

- 19.Area of Australia - states and territories [www.ga.gov.au/scientific-topics/national-location-information/dimensions/area-of-australia-states-and-territories]

- 20.Australian Bureau of Statistics. National, state, and territory population (June 2023). 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/national-state-and-territory-population/latest-release.

- 21.National Indigenous Australians Agency. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health performance framework, Table D1.18.14 NT: Hospitalisation rates for mental health-related conditions (based on principal diagnosis), by Indigenous status, sex and age group, Northern Territory and Australia, July 2017 to June 2019. 2023. https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/1-18-social-emotional-wellbeing/data#DataSource.

- 22.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Causes of death, Australia, 2022: Table 12.4, underlying causes of death, leading causes by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origin, numbers and age-specific death rates, males, females, and persons, NSW, QLD, SA, WA, and NT, 2018–2022 (ABS 3303.0). 2022. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/causes-death/causes-deathaustralia/2022/2022_12%20Deaths%20of%20Aboriginal%20and%20Torres%20Strait%20Islander%20people.xlsx.

- 23.Gatwiri K, Rotumah D, Rix E. BlackLivesMatter in healthcare: Racism and implications for health inequity among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:4399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kilian A, Williamson A. What is known about pathways to mental health care for Australian Aboriginal young people? A narrative review. International Journal of Equity in Health. 2018;17:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canuto K, Wittert G, Harfield S, Brown A. “I feel more comfortable speaking to a male”: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men’s discourse on utilizing primary health care services. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2018;17:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinton R, Kavanagh DJ, Barclay L, Chenhall R, Nagel T. Developing a best practice pathway to support improvements in Indigenous Australians’ mental health and wellbeing: A qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donovan RJ, Drane CF, Owen J, Murray L, Nicholas A, Anwar-McHenry J. Impact on stakeholders of a cultural adaptation of a social and emotional wellbeing in an Aboriginal community. Health Promot J Austr. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Tsey K, Every A. Evaluating Aboriginal empowerment programs: The case of Family Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2007;24:509–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sabbioni D, Feehan S, Nicholls C, Soong W, Rigoli D, Follett D, Carastathis G, Gomes A, Griffiths J, Curtis K, et al. Providing culturally informed mental health services to Aboriginal youth: The YouthLink model in Western Australia. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2018;12:987–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tighe J, Shand F, Ridani R, Mackinnon A, De La Mata N, Christensen H. Ibobbly mobile health intervention for suicide prevention in Australian Indigenous youth: a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e013518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skerrett DM, Gibson M, Darwin L, Lewis S, Rallah R, De Leo D. Closing the gap in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth suicide: A social-emotional wellbeing service innovation project. Aust Psychol. 2018;53:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cox T, Hoang H, Barnett T, Cross M. Older Aboriginal men creating a therapeutic Men’s Shed: An exploratory study. Ageing Soc. 2020;40:1455–68. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanley N, Marchetti E. Dreaming Inside: An evaluation of a creative writing program for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men in prison. Aust N Z J Criminol. 2020;53:285–302. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith JA, Merlino A, Christie B, Adams M, Bonson J, Osborne R, Judd B, Drummond M, Aanundsen D, Fleay J. “Dudes are meant to be tough as nails”: The complex nexus between masculinities, culture and health literacy from the perspective of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males - implications for policy and practice. Am J Mens Health. 2020;14:1557988320936121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Souter J, Smith JA, Canuto K, Gupta H. Strengthening health promotion development with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males in remote Australia: A Northern Territory perspective. Aust J Rural Health. 2022;30:540–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liddle J, Langton M, Rose JWW, Rice S. New thinking about old ways: Cultural continuity for improved mental health of young Central Australian Aboriginal men. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2022;16:461–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merlino A, Smith JA, Adams M, Bonson J, Osborne R, Judd B, Drummond M, Aanundsen D, Fleay J, Christie B. What do we know about the nexus between culture, age, gender and health literacy? Implications for improving the health and well-being of young indigenous males. International Journal of Men’s Social and Community Health. 2020;3:e46–57. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Indigenous Allied Health Australia. Cultural responsiveness in action: An IAHA framework. Deakin West, ACT: IAHA; 2019.

- 39.Dudgeon P, Walker R, Scrine C, Shepherd C, Calma T, Ring I. Effective strategies to strengthen the mental health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2014.

- 40.Anwar-McHenry J, Murray L, Drane CF, Owen J, Nicholas A, Donovan RJ. Impact on community members of a culturally-appropriate adaptation of a social and emotional wellbeing intervention in an Aboriginal community. J Public Ment Health. 2022;21:108–18. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gee G, Dudgeon P, Schultz C, Hart A, Kelly K. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional wellbeing. In: Dudgeon P, Milroy H, Walker R, eds. Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2014:55–68.

- 42.Opozda MJ, Galdas PM, Watkins DC, Smith JA. Intersecting identities, diverse masculinities, and collaborative development: Considerations in creating online mental health interventions that work for men. Compr Psychiatry. 2023;129:152443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perera C, Salamanca-Sanabria A, Caballero-Bernal J, Feldman L, Hansen M, Bird M, Hansen P, Dinesen C, Wiedemann N, Vallières F. No implementation without cultural adaptation: a process for culturally adapting low-intensity psychological interventions in humanitarian settings. Confl Heal. 2020;14:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bernal G, Jiménez Chafey MI, Domenech Rodríguez MM. Cultural adaptation of treatments: A resource for considering culture of evidence-based practice. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2009;40:361–8. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bernal G, Bonilla J, Bellido C. Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: issues for the cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1995;23:67–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fletcher R, Hammond C, Faulkner D, Turner N, Shipley L, Read D, Gwynn J. Stayin’ on Track: The feasibility of developing internet and mobile phone-based resources to support young Aboriginal fathers. Aust J Prim Health. 2017;23:329–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Franck L, Midford R, Cahill H, Buergelt PT, Robinson G, Leckning B, Paton D. Enhancing social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal boarding students: Evaluation of a social and emotional learning pilot program. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nagel T, Hinton R, Griffin C. Yarning about Indigenous mental health: Translation of a recovery paradigm to practice. Adv Ment Health. 2012;10:216–23. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nagayama Hall GC, Ibaraki AY, Huang ER, Marti CN, Stice E. A meta-analysis of cultural adaptations of psychological interventions. Behaviour Therapy. 2016;47:993–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ellis DM, Draheim AA, Anderson PL. Culturally adapted digital mental health interventions for ethnic/racial minorities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2022;90:717–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moore G, Campbell M, Copeland L, Craig P, Movsisyan A, Hoddinott P, Littlecott H, O’Cathain A, Pfadenhauer L, Rehfuess E, et al. Adapting interventions to new contexts - the ADAPT guidance. BMJ. 2021;374:n1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wesley-Esquimaux CC, Snowball A. Viewing violence, mental illness, and addiction through a wise practices lens. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2010;8:390–407. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bernal G, Adames C. Cultural adaptations: Conceptual, ethical, contextual, and methodological issues for working with ethnocultural and majority-world populations. Prev Sci. 2017;18:681–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.González Castro F, Barrerra J, M., Holleran Steiker LK: Issues and challenges in the design of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:213–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Watkins DC, Goodwill JR, Johnson NC, Casanova A, Wei T, Ober Allen J, Williams EDG, Anyiwo N, Jackson ZA, Talley LM, Abelson JM. An online behavioural health intervention promoting mental health, manhood, and social support for young Black men: The YBMen Project. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2020;14:1557988320937215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Watkins DC, Allen JO, Goodwill JR, Noel B. Strengths and weaknesses of the Young Black Men, Masculinities, and Mental Health (YBMen) Facebook project. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2017;87:392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watkins DC, Brown BR, Abelson JM, Ellis J. First-generation Black college men in the United States and the value of cohort-based programs: Addressing inequities through the YBMen project. In: Smith JA, Watkins DC, Griffith DM, eds. Health promotion with adolescent boys and young men of colour. Cham; 2023.

- 58.RISE YBMen Toronto: The CRIB announces partnership with University of Michigan supported by the Movember Foundation [https://socialwork.utoronto.ca/news/rise-ybmen-toronto-the-crib-announces-partnership-with-university-of-michigan-supported-by-the-movember-foundation/]

- 59.Duarte N, Hughes SL, Paúl C. Cultural adaptation and specifics of the Fit & Strong! program in Portugal. TBM. 2019;9:67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sit HF, Ling R, Lam AIF, Chen W, Latkin CA, Hall BJ. The cultural adaptation of Step-By-Step: An intervention to address depression among Chinese young adults. Front Psych. 2020;11:650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kumpfer KL, Pinyuchon M. Teixera de Melo A, Whiteside HO: Cultural adaptation processes for international dissemination of the Strengthening Families program. Eval Health Prof. 2008;31:226–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fisher J, Nguyen H, Mannava P, Tran H, Dam T, Tran H, Tran T, Durrant K, Rahman A, Luchters S. Translation, cultural adaptation and field-testing of the Thinking Healthy Program for Vietnam. Globalisation and Health. 2014;10:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shiu CS, Chen WT, Simoni J, Fredriksen-Goldsen K, Zhang F, Zhou H. The Chinese Life-Steps program: A cultural adaptation of a cognitive-behavioural intervention to enhance HIV medication adherence. Cognitive and Behavioural Practice. 2013;20:202–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goforth AN, Nichols LM, Sun J, Violante AE, Brooke E, Kusumaningsih S, Howlett R, Hogenson D, Graham N. Cultural adaptation of an educator social-emotional learning program to support Indigenous students. Sch Psychol Rev. 2024;53:365–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hiratsuka VY, Parker ME, Sanchez J, Riley R, Heath D, Chomo JC, Beltangady M, Sarche M. Cultural adaptations of evidence-based home visitation models in tribal communities. Infant Ment Health J. 2018;39:265–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lund JI, Toombs E, Mushquash CJ, et al. Cultural adaptation of a comprehensive housing outreach program for indigenous youth exiting homelessness. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2022:13634615221135438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Wiltsey Stirman S, Baumann AA, Miller CJ. The FRAME: an expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. 2019;14:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harper Shehdeh M, Heim E, Chowdhary N, Maercker A, Albanese R. Cultural adaptation of minimally guided interventions for common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mental Health. 2016;3:e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith J: Northern Territory Indigenous male research strategy think tank: Final report. Darwin: Charles Darwin University; 2016.

- 70.Smith JA, Adams M, Bonson J. Investing in men’s health in Australia. MJA. 2018;208:67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Smith JA, Drummond M, Adams M, Bonson J, Christie B. Understanding men’s health inequities in Australia. In: Griffith DM, Bruce MA, Thorpe RJ, editors. Men’s health equity: A handbook. New York: Routledge; 2019. p. 498–509. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smith JA, Merlino A, Christie B, Adams M, Bonson J, Osborne RH, Drummond M, Judd B, Aanundsen D, Fleay J, Gupta H. Using social media in health literacy research: A promising example involving Facebook with young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males from the Top End of the Northern Territory. Health Promot J Austr. 2020;32:186–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smith JA, Watkins DC, Griffith DM, Rung DL: What do we know about global efforts to promote health among adolescent boys and young men of colour? In Health promotion with adolescent boys and young men of colour: Global strategies for advancing research, policy, and practice in context. Edited by Smith JA, Watkins DC, Griffith DM. New York: Springer; 2023

- 74.Marshall S, Taki S, Love P, et al. The process for culturally adapting the Healthy Beginnings early obesity prevention program for Arabic and Chinese mothers in Australia. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Barrera M, Castro FG, Strycker LA, Toobert DJ. Cultural adaptations of behavioural health interventions: a progress report. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;81:196–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Drawson AS, Toombs E, Mushquash CJ. Indigenous research methods: a systematic review. International Indigenous Policy Journal. 2017;8:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 77.The Larrakia people [https://larrakia.com/about/the-larrakia-people/]

- 78.Bonevski B, Randell M, Paul C, et al. Reaching the hard-to-reach: a systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2014;14(42). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Shaghaghi A, Bhopal RS, Sheikh A. Approaches to recruiting “hard-to-reach” populations in research: a review of the literature. Health Promotion Perspectives. 2011;1:86–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.IAHA National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Academy [https://iaha.com.au/careers-and-pathways/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-health-academy/]

- 81.Povey J, Mills PPJR, Dingwall KM, Lowell A, Singer J, Rotumah D, Bennett-Levy J, Nagel T. Acceptability of mental health apps for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: A qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dockery AM, Colquhoun S. Mobility of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: A literature review (CRC-REP Working Paper CW004). Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2012.

- 83.Taylor A, Carson D. Indigenous mobility and the Northern Territory emergency response. People and Place. 2009;17:29–38. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Povey J, Sweet M, Nagel T, Mills PPJR, Stassi CP, Purutatameri AMA, Lowell A, Shand F, Dingwall K. Drafting the Aboriginal and Islander Mental Health Initiative for Youth (AIMhi-Y) app: Results of a formative mixed methods study. Internet Interv. 2020;21:100318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Opozda MJ, Oxlad M, Turnbull D, Gupta H, Smith JA, Ziesing S, Nankivell ME, Wittert G. Facilitators of, barriers to, and preferences for e-mental health interventions for depression and anxiety in men: Metasynthesis and recommendations. J Affect Disord. 2024;346:75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.eSafety Commissioner. Cool, beautiful, strange, and scary: The online experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and their parents and caregivers. Canberra: Australian Government; 2022.

- 87.Price M, Dalgleish J. Help-seeking among Indigenous Australian adolescents: Exploring attitudes, behaviours, and barriers. Youth Studies Australia. 2013;32:10–8. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dingwall KM, Povey J, Sweet M, Friel J, Shand F, Titov N, Wormer J, Mirza T, Nagel T. Feasibility and acceptability of the Aboriginal and Islander Mental Health Initiative for Youth app: Nonrandomised pilot with First Nations young people. JMIR Hum Factors. 2023;10:e40111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tighe J, Shand F, McKay K, Mcalister TJ, Mackinnon A, Christensen H. Usage and acceptability of the iBobbly app: Pilot trial for suicide prevention in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth. JMIR Mental Health. 2020;7:e14296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hopkins KD, Zubrick SR, Taylor CL. Resilience amongst Australian Aboriginal youth: An ecological analysis of factors associated with psychosocial functioning in high and low family risk contexts. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:102820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Menges JR, Caltabiano ML, Clough A. What works for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men? A systematic review of the literature. Journal of the Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet. 2023;4:5. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Prehn J, Guerzoni MA, Peacock H, et al. Supports desired by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males in fatherhood: Focusing on the social and cultural determinates of health and wellbeing. Aust J Soc Issues. 2024.

- 93.Commonwealth of Australia. National strategic framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples' mental health and social and emotional wellbeing 2017-2023. Canberra: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet; 2017.

- 94.Zubrick SR, Sheperd CCJ, Dudgeon P, et al. Social determinants of social and emotional wellbeing. In: Dudgeon P, Milroy H, Walker R, eds. Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2014:93–112.