FLACS showed a trend of less damage to the corneal endothelium. ECL stabilized at 3 months at positions 1 and 3 but continued at position 2 even at 6 months.

Abstract

Purpose:

To compare changes in corneal endothelial parameters after femtosecond laser–assisted cataract surgery (FLACS) and conventional phacoemulsification surgery (CPS) in different corneal regions.

Setting:

Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou, Taiwan.

Design:

Single-center, retrospective.

Methods:

Before and 1, 3, and 6 months postoperatively, specular microscopy was performed to measure endothelial cell density (ECD), corneal thickness, hexagonal cell rate (Hex), and coefficient of variation (CoV). Position 1 referred to the central cornea, position 2 was nearest to the main wound, and position 3 was at the peripheral zone diagonal to the main wound.

Results:

This study analyzed 96 eyes in the FLACS group and 110 eyes in the CPS group. Preoperatively, position 1 had lower ECD and CoV and higher Hex compared with the peripheral regions. FLACS patients had a significantly less phacoemulsification time and cumulative dissipated energy. At 1 month, FLACS patients showed a significantly smaller increase in corneal thickness at positions 1 and 2. At 3 months, FLACS patients had lower endothelial cell loss (ECL) at positions 1 and 3. ECL remained lower in FLACS patients at 6 months. The highest ECL was observed at position 2 in both groups and was progressive up to 6 months.

Conclusions:

After phacoemulsification, ECL varied in different corneal regions. At 3 months, the FLACS group exhibited significantly less ECL at the central cornea; however, the continued ECL at 6 months near the main wound suggested ongoing endothelial remodeling in the region.

Damage to the corneal endothelium is the most devastating injury inflicted on the cornea during phacoemulsification. The turbulent flow of the irrigation solution, turbulent lens fragments, instrument-related mechanical trauma, intraocular lens (IOL) contact, and free oxygen radicals can all cause corneal damage during cataract surgery.1 Furthermore, several preoperative and intraoperative parameters (nucleus rigidity, advanced age, long phacoemulsification time, high ultrasound energy, short axial length, and surgical skill) are related to an increased risk of endothelial cell damage after phacoemulsification.1–6 Higher effective phacoemulsification time and cumulative dissipated energy values are known to be associated with a higher risk of intraoperative corneal endothelial cell injury and postoperative corneal edema.7,8

By using a femtosecond laser to fragment the crystalline lens, less ultrasound energy is required to complete its removal, and theoretically, endothelial cell loss (ECL) is decreased.9,10 Mastropasqua et al. previously demonstrated that the femtosecond laser procedure was safer, more efficient, and less damaging than the manual technique, as evidenced by less central ECL, less increase in corneal thickness (CT) at the incision site, and better tunnel morphology.11 Quinto et al. later demonstrated that femtosecond laser–assisted cataract surgery (FLACS) and conventional phacoemulsification surgery (CPS) had comparable refractive and visual outcomes.12

By contrast, Popovic et al. concluded that there were no significant differences in postoperative endothelial cell density (ECD).13 During a 3-month follow-up period, Dzhaber et al. found that postoperative corneal ECD and central CT (CCT) were comparable between FLACS and CPS.14 According to Lucia et al., although FLACS improves phacoemulsification parameters when compared with CPS, there are no significant differences in corneal endothelium measurements between the 2.15 Finally, a more recent meta-analysis on ECL found no significant difference between the 2 techniques.16

Our research is based on the ongoing discussion on the impact of FLACS on ECL and other parameters of endothelial integrity. The goal of this study was to investigate whether FLACS is superior to conventional CPS in reducing ECL, with special attention given to its impact on different corneal regions.

METHODS

Study Design

In this retrospective, single-center study, patients undergoing FLACS and CPS at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CGMH), Linkou, Taiwan, between 2018 and 2022 were recruited. The study followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and institutional review board permission was obtained from CGMH (approval number: 202100055B0C102(2301300008). Written informed consent was waived because only electronic medical records were reviewed. The inclusion criteria were patients aged 18 years or older with a minimum follow-up of 6 months who underwent implantation of a premium IOL using FLACS or CPS. Patients with a preoperative endothelial density less than 1500/mm2, unhealthy looking endothelium with the appearance of guttae, any evidence of Fuchs dystrophy with no visible central guttae, nuclear sclerosis cataracts reaching NO5/NC5 according to the Lens Opacities Classification System III and posterior capsular rupture were excluded.

Preoperatively, various assessments were conducted, including autorefraction, biometry, uncorrected and corrected distance visual acuity, intraocular pressure measurement, slitlamp biomicroscopy, and indirect ophthalmoscopy. Corneal endothelial cells were also routinely accessed using a noncontact specular microscope (CEM-530, Nidek Co., Ltd.). Three different positions of the cornea were simultaneously evaluated for ECD, CT, rate of hexagonal cells rate (Hex), and coefficient of variation (CoV). Position 1 was aimed at the central cornea. Position 2 was aimed at a peripheral zone 7.3 mm in diameter nearest to the temporal main wound (210 degrees for right eye and 30 degrees for left eye), which is the area that might show the highest endothelial damage. Position 3 was aimed at the peripheral zone farthest from and opposite the main wound, which is the area that might have the minimal endothelial damage. Specular microscopy was performed before surgery and at 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months postoperatively. The Nidek CEM-530 specular microscope can perform both automatic and manual measurements. We avoid using manual measurements because they typically underestimate the cell count. This is particularly relevant because we also captured images from peripheral corneas. In our study, we exclusively use automatic measurements with manual correction if needed. The built-in NAVIS-EX imaging software automatically calculated the results, and then, the data were recorded in the electronic medical records.

Surgical Technique

All surgeries were performed by the same surgeon (D.H.-K.M.) using the temporal clear corneal approach. The 3-step clear cornea main incision was fashioned with a 2.4 mm angled keratome. A 5.0 mm continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis was created using capsular forceps. Phacoemulsification was performed using mainly the divide-and-conquer technique or the stop-and-chop technique for more difficult nuclei. The Infiniti System (Alcon Laboratories, Inc.) was used for phacoemulsification.

The laser-assisted main incisions, side-port incision, capsulotomy, and lens fragmentation (chop + cylinder ablation) were performed using the LenSx laser system (Alcon Laboratories, Inc.). The subsequent phacoemulsification and irrigation/aspiration procedures were the same for both FLACS and CPS. After removing the cataract, the IOL was implanted, including aspheric IOLs, toric IOLs, and trifocal IOLs from Alcon Laboratories, Inc. and Johnson & Johnson Vision.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis for the study was conducted using SPSS software. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were performed to assess the normality of the data. Histograms were also used to visually confirm the normal distribution of the data. For continuous variables, independent-sample t tests were used, while the Mann-Whitney U test was used for nonparametric comparisons. When comparing 3 or more groups, the Kruskal-Wallis test (nonparametric) and analysis of variance (ANOVA) test (parametric) were used, depending on the distribution of the data and the parametric or nonparametric nature of the variables.

For variables measured at multiple timepoints, repeated measures ANOVA was used. Corrections such as Greenhouse-Geisser, Huynh-Feldt, and lower-bound were used to adjust the degrees of freedom for within-subject effects, considering violations of the assumption of sphericity. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare parameters when the sample sizes were unequal. A P value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The study included 96 eyes from 78 patients in the FLACS group and 110 eyes from 87 patients in the CPS group. The male-to-female ratio did not show a significant difference (P = .241). However, there was a marginally significant difference in the mean age of patients between the FLACS and CPS groups (61.43 ± 12.03 years vs 64.56 ± 10.68 years; P = .052). The FLACS group had a significantly lower phacoemulsification time than the CPS group (57.39 ± 32.42 seconds vs 75.12 ± 58.43 seconds; P < .001). In addition, the cumulative dissipated energy was also significantly lower in the FLACS group (19.28 ± 15.02 kN·mm vs 22.28 ± 12.31 kN·mm; P < .001). Because preoperatively, the measured endothelial parameters were similar between the FLACS and CPS groups, data from all 206 eyes were combined for the comparison of endothelial parameters at 3 different regions. Preoperatively, position 1 had a significantly lower ECD (2616 ± 332/mm2) than positions 2 (2657% ± 446/mm2) and 3 (2737 ± 425/mm2; P = .009). Position 1 exhibited a significantly lower CoV (29% ± 5%) than positions 2 and 3 (31% ± 7% and 32% ± 7%, respectively; P < .001). Hex was highest in position 1 (67% ± 8%), while position 3 had the lowest Hex (64% ± 9%; P = .008). The thinnest part of the cornea was observed in position 1 (556 ± 39 μm), whereas the thickest zone was found in position 3 (593 ± 50 μm; P < .001). These findings are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of the mean values of preoperative ECD, CoV, Hex, and CT at representative locations

| Parameters | Position | P value | ||

| Central (position 1) | Nearest to the wound (position 2) | Farthest from the wound (position 3) | ||

| ECD (mm2) | 2616 ± 332 | 2657 ± 446 | 2737 ± 425 | .009a |

| CoV (%) | 29 ± 5 | 31 ± 7 | 32 ± 7 | <.001a |

| Hex (%) | 67 ± 8 | 65 ± 10 | 64 ± 9 | .008a |

| CT (um) | 556 ± 39 | 579 ± 43 | 593 ± 50 | <.001a |

CoV = coefficient of variation; CT = corneal thickness; ECD = endothelial cell density; Hex = hexagonal cell

The values were measured before the operation, primarily during the last visit before the operation, or on the same day shortly before the operation

ANOVA

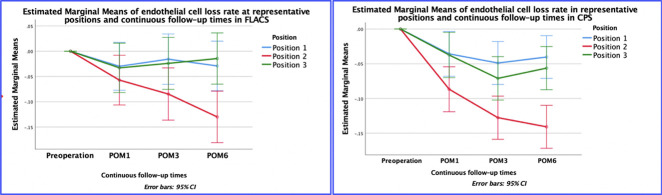

Table 2 and Figure 1 present that in both the FALCS and CPS groups, there is a significant difference in ECL rate at all postoperative time intervals. When comparing the ECL rate in the FLACS and CPS groups, the study demonstrated that the region closest to the main wound consistently exhibited the highest rate of ECL. By contrast, there was variability in the extent of cell damage between zones 1 and 3. Within the FLACS group, at the first month postoperatively (postoperative month [POM] 1), position 2 exhibited the highest (−5% ± 3%) ECL rate, while position 3 (−3% ± 2%) had a lower rate, and position 1 had the lowest (−3% ± 1%) rate (P = .005). At POM3, position 2 had the highest (−9% ± 4%) ECL rate, whereas position 1 showed a lower (−3% ± 1%) rate, and position 3 displayed the lowest (−1% ± 2%) rate (P < .001). Similarly, at POM6, position 2 demonstrated the highest (−13% ± 3%) ECL rate, position 1 had a lower (−2% ± 1%) rate, and position 3 had the lowest (−1% ± 2%) rate (P < .001). In the CPS group, at POM1, position 2 had the highest (−7% ± 2%) ECL rate, while position 1 had a lower (−4% ± 1%) rate, and position 3 had the lowest (−4% ± 2%) rate (P = .008). At POM3, position 2 displayed the highest ECL (−13% ± 2%) rate, position 3 had a lower (−7% ± 1%) rate, and position 1 exhibited the lowest (−5% ± 1%) rate (P < .001). Similarly, at POM6, position 2 demonstrated the highest (−14% ± 2%) ECL rate, while position 3 showed a lower (−6% ± 2%) rate, and position 1 had the lowest (−4% ± 1%) rate. It should be noted that in the FLACS group, the ECL rates at positions 1 and 3 were relatively stable from POM1 to POM6, while in the CPS group, the ECL rate continued to increase at POM3 and then stabilized at POM6, and the ECL rate at position 3 was always higher than that at position 1.

Table 2.

Mean percentage of cell loss in representative positions at postoperative follow-up periods

| Positions | POM1 | POM3 | POM6 | P value |

| Comparison of ECL rate in representative positions in FLACS (%) | ||||

| Position 1 | −3 ± 1 | −2 ± 1 | −3 ± 1 | .048a |

| Position 2 | −5 ± 3 | −9 ± 4 | −13 ± 3 | .001a |

| Position 3 | −3 ± 2 | −1 ± 2 | −1 ± 2 | .004a |

| P value | .005b | <.001b | <.001b | |

| Comparison of ECL rate in representative positions in CPS (%) | ||||

| Position 1 | −4 ± 1 | −5 ± 1 | −4 ± 1 | .001a |

| Position 2 | −7 ± 2 | −13 ± 2 | −14 ± 2 | .001a |

| Position 3 | −4 ± 2 | −7 ± 1 | −6 ± 2 | .002a |

| P value | .008b | <.001b | <.001b |

CPS = conventional phacoemulsification surgery; ECL = endothelial cell loss; POM = postoperative month

Repeated ANOVA test

Kruskal-Wallis test

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of linear trends in cell loss (as a percentage) at continuous follow-up times at representative positions. CPS = conventional phacoemulsification surgery; ECL = endothelial cell loss; POM = postoperative month; FLACS = femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery

As presented in Figure 1 and Table 3, we compared the ECL and ECL rates at 1, 3, and 6 months between both groups. Although the averaged ECL rate was invariably lower in the FLACS group, most differences did not reach statistical significance due to the large variation in data. At POM1, there were no significant differences in ECL between the 2 groups at any position (P > .05). At POM3, only position 1 exhibited significantly less ECL in the FLACS group (−50 ± 28/mm2) than in the CPS group (−125 ± 23/mm2, P = .014), and the ECL rate showed the same trend (−2% ± 1% vs −5% ± 1%, P = .014). Position 3 in the FLACS group also showed a substantially lower ECL and ECL rate; however, statistical significance was not reached (−58 ± 50 vs −206 ± 43/mm2, P = .059; −1% ± 2% vs −7 ± 1%, P = .074). At POM6, although the ECL rate at the 3 positions was consistently lower in the FLACS group, statistical significance was also not reached (Table 3). We found that the ECD consistently decreased over time in the zone nearest to the main wound, while the ECL rates in other zones remained relatively stable. This observation occurred in both the FLACS and CPS groups (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Comparison of preoperative cell density, postoperative cell loss count, and rate between the 2 groups

| Parameters | Position | FLACS (n = 96) | CPS (n = 110) | P value |

| Pre ECD | 1 | 2601 ± 342 | 2629 ± 324 | .545a |

| 2 | 2604 ± 462 | 2704 ± 429 | .109a | |

| 3 | 2676 ± 447 | 2792 ± 399 | .053a | |

| Post ECL | ||||

| POM1 | 1 | −79 ± 38 | −115 ± 32 | .473a |

| 2 | −218 ± 53 | −230 ± 49 | .812a | |

| 3 | −128 ± 56 | −113 ± 41 | .547a | |

| POM3 | 1 | −50 ± 28 | −125 ± 23 | .014b |

| 2 | −333 ± 58 | −374 ± 47 | .767a | |

| 3 | −58 ± 50 | −206 ± 43 | .059b | |

| POM6 | 1 | −77 ± 29 | −110 ± 27 | .181a |

| 2 | −422 ± 58 | −399 ± 42 | .251a | |

| 3 | −68 ± 43 | −166 ± 44 | .15b | |

| Post ECL rate (%) | ||||

| POM1 | 1 | −3 ± 1 | −4 ± 1 | .486a |

| 2 | −5 ± 3 | −7 ± 2 | .705a | |

| 3 | −3 ± 2 | −4 ± 2 | .61a | |

| POM3 | 1 | −2 ± 1 | −5 ± 1 | .014b |

| 2 | −9 ± 4 | −13 ± 2 | .585a | |

| 3 | −1 ± 2 | −7 ± 1 | .074b | |

| POM6 | 1 | −3 ± 1 | −4 ± 1 | .173a |

| 2 | −13 ± 3 | −14 ± 2 | .216a | |

| 3 | −1 ± 2 | −5 ± 2 | .172b |

CPS = conventional phacoemulsification surgery; ECD = endothelial cell density; ECL = endothelial cell loss; POM = postoperative month

Independent sample t test

Wilcoxon rank-sum test

In Table 4, we compared the CoV, Hex, and CT between the 2 groups. Again, due to the large variation in data, only few comparisons showed a significant difference. There was no significant difference in preoperative CoV between the FLACS and CPS groups at any location (P = .374, P = .974, and P = .557, respectively). At POM1, the CoV increased in every position in both groups (Table 4). At POM3, although a trend of reduction in CoV was seen in the FLACS group, no statistical significance was reached during the 6-month follow-up. Similarly, there was no significant difference in the ratio of hexagonal cells (Hex in %) between the FLACS and CPS groups. At the first POM1, Hex decreased in all positions (Table 4). At POM3, Hex showed a tendency to increase in the FLACS group, and statistical significance was not reached during the 6-month follow-up period. Finally, there was no significant difference in preoperative CT in the representative positions between the groups. At POM1, the CPS group showed a significant increase in CT in positions 1 (FLACS vs CPS: 4 ± 3 μm vs 7 ± 2 μm; P = .041) and 2 (−2 ± 4 μm vs 11 ± 4 μm, P = .004) but a decrease in position 3 (−2 ± 5 μm vs −10 ± 8 μm) without statistical significance. At POM3, both groups demonstrated a reduction in CT at positions 1 (−5 ± 3 μm vs −3 ± 1 μm), 2 (−7 ± 4 μm vs −3 ± 4 μm), and 3 (−6 ± 4 μm vs −8 ± 4 μm), but none of them were statistically significant. At POM6, CT decreased in all positions in both groups, but without reaching statistical significance (Table 4).

Table 4.

Mean preoperative CoV, Hex, and corneal thickness and postoperative changes in the 2 groups

| Parameters | Position | FLACS | CPS | P value |

| Pre CoV (%) | 1 | 29 ± 6 | 29 ± 5 | .374a |

| 2 | 31 ± 1 | 31.5 ± 7 | .974a | |

| 3 | 31 ± 7 | 32 ± 7.0 | .557a | |

| Changes in post CoV (%) | ||||

| POM1 | 1 | 2 ± 1 | 2 ± 0.6 | .966a |

| 2 | 1 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | .971a | |

| 3 | 3 ± 1 | 2 ± 1.0 | .335a | |

| POM3 | 1 | 1 ± 1 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | .566b |

| 2 | −0.5 ± 1.0 | 1 ± 1.0 | .221b | |

| 3 | −0.1 ± 0.1 | 2 ± 1.0 | .324b | |

| POM6 | 1 | −0.1 ± 0.5 | 1 ± 0.7 | .547b |

| 2 | −2.5 ± 1.0 | −0.5 ± 1.0 | .065b | |

| 3 | 0.2 ± 1.0 | 0.3 ± 1.0 | .722b | |

| Pre Hex | 1 | 66 ± 11 | 68 ± 5 | .283a |

| 2 | 65 ± 12 | 66 ± 8 | .294a | |

| 3 | 64 ± 10 | 64 ± 9 | .766a | |

| Changes in post Hex | ||||

| POM1 | 1 | −2 ± 1 | −1 ± 1 | .205a |

| 2 | −4 ± 2.0 | −3 ± 1 | .431a | |

| 3 | −3 ± 2 | −1 ± 1 | .953b | |

| POM3 | 1 | 0.6 ± 1 | −1 ± 1.0 | .906b |

| 2 | 1.0 ± 1 | −1 ± 1 | .913b | |

| 3 | −2.0 ± 2 | −1 ± 1 | .611b | |

| POM6 | 1 | 0.3 ± 1 | −1 ± 1.0 | .974b |

| 2 | 0.4 ± 1 | −0.5 ± 1 | .983b | |

| 3 | −0.4 ± 2 | −3 ± 1 | .510b | |

| Pre corneal thickness | 1 | 554 ± 42 | 558 ± 37 | .55a |

| 2 | 579 ± 43 | 586 ± 44 | .299a | |

| 3 | 593 ± 50 | 603 ± 50 | .171a | |

| Changes in post corneal thickness | ||||

| POM1 | 1 | 4 ± 3 | 7 ± 2 | .041a |

| 2 | −2 ± 4 | 11 ± 4 | .004a | |

| 3 | −2 ± 5 | −10 ± 8 | .609a | |

| POM3 | 1 | −5 ± 3 | −3 ± 1 | .460a |

| 2 | −7 ± 4 | −3 ± 4 | .809a | |

| 3 | −6 ± 4 | −8 ± 4 | .461a | |

| POM6 | 1 | −8 ± 2 | −2 ± 1 | .090a |

| 2 | −6 ± 4 | −3 ± 4 | .709a | |

| 3 | −1 ± 4.0 | −10 ± 4 | .109a |

CoV = coefficient of variation; CPS = conventional phacoemulsification surgery; Hex = hexagonal rate; POM = postoperative month

Independent sample t test

Wilcoxon rank-sum test

DISCUSSION

A key issue that was not addressed in previous studies involving the effect of FLACS on EC loss is the topographical variation in corneal endothelial density. Amann et al. found that paracentral and peripheral areas exhibited significantly higher ECD than the central zone.17 There was not only a significant negative correlation between mean ECD and age but also a positive correlation between the CoV and age.18 We observed a significant difference in ECD between the central and peripheral zones. The ECD was found to be significantly lower in the central zone, with a 5.04% increase in ECD at the peripheral zone. Furthermore, we found a significantly higher rate of Hex in the central zone than in the peripheral zone. Conversely, the CoV was significantly lower in the central zone. These findings are consistent with previous studies.

This study aimed to compare corneal endothelial damage after FLACS and CPS. Previous studies have reported mixed findings regarding ECL between the 2 techniques. Takacs et al. found an insignificant difference in reduction with FLACS (4.4%) and with CPS (10.5%).19 Conrad-Hengerer et al. showed a significantly lower ECL in the FLACS vs CPS group at 1 week postoperatively (7.9% vs 12.1%) and at 3 months postoperatively (8.1% vs 13.7%).20 Schroeter et al. also demonstrated that low-energy FLACS resulted in better outcomes, with an ECL of 12.7% in the FLACS group and 17.4% in the CPS group after 12 weeks.21 In our study, we did not find a significant difference in ECL between FLACS and CPS at 1 and 6 months postoperatively across the 3 corneal zones. However, at 3 months postoperatively, the FLACS group showed a significantly lower ECL (−50 ± 28 vs −125 ± 23) and ECL rate (−2% ± 1% vs −5% ± 1%) than the CPS group, specifically in the central zone. In our experience, the substantial variation in the ECL rate in both groups may be the major reason why the difference did not reach statistical significance. To circumvent this problem, Wang et al. recently conducted a meta-analysis that included 42 trials containing 3916 eyes of FLACS patients and 3736 eyes of CPS patients. The ECL rate was significantly lower in the FLACS group at 1–3 days, 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months.22

Among the studies investigating ECL after FLACS, few have specifically focused on evaluating ECL in different corneal zones. Mastropasqua et al. compared the functional and morphological outcomes of femtosecond laser clear corneal incision vs manual clear corneal incision. They found that the femtosecond laser procedure was safe, efficient, and less damaging, as evidenced by lower central ECL, a lower increase in CT at the incision site, and better tunnel morphology compared with the manual technique.11 By contrast, Abell et al. suggested that laser corneal incisions in FLACS could result in greater ECL than manual incisions.23 On the other hand, studies comparing manual incisions have reported a significant difference in ECL, favoring FLACS over CPS.20,24,25 In our study, we observed that ECL was higher in both the FLACS and CPS groups at position 2. However, there was a trend of less endothelial loss in the FLACS group, suggesting that the use of a laser for wound formation did not cause additional damage to the corneal endothelium when compared with knife-based wound formation. Further research is needed to fully understand whether femtosecond lasers may reduce ECL near corneal wounds in eyes with compromised endothelium.

Among the studies investigating the trend of ECL rates after cataract surgery, the study of Krarup et al. found a difference in postoperative ECL rates between FLACS and CPS. Initially, the study reported ECL rates of 9.1% for FLACS and 8.2% for CPS in the first 1 to 3 days postsurgery. However, at 3 months, the ECL rates increased to 11.4% for FLACS and 13.9% for CPS. These findings suggest that the risk of ECL may increase over time after cataract surgery, regardless of the surgical technique used.26 In our study, we found a progressive increase in the ECL rate at the incisional site over time, which was observed in both the FLACS and CPS groups (POM1/POM3/POM6: −5%/−9%/−13% in FLACS and −7%/−13%/−14% in CPS). By contrast, the central and farthest sites from the wound showed stabilized ECL rates at 3 months postoperatively in the FLACS group but not in the CPS group. Contrary to our hypothesis that ECL would be lowest at position 3, we observed that in the CPS group, the ECL rate was higher at position 3 than at position 1, which may be caused by stronger turbulence flow from the irrigation solution and ultrasound lens fragmentation at that position. These findings emphasize the importance of long-term monitoring of ECL rates and considering the effect on different corneal zones when assessing the impact of surgical trauma. Further research is needed to fully understand the long-term effects of FLACS and CPS on ECL and to develop strategies for minimizing ECL during cataract surgery.

According to the meta-analysis of Wang et al., which included 42 studies, there was no significant difference in Hex and CoV between the FLACS and CPS groups at 1, 3, and 6 months postoperatively.22 This finding is consistent with those of our study, which also did not find a significant difference in Hex and CoV between the 2 groups. In addition, in the meta-analysis of Wang et al., 15 studies reported postoperative CCT and found that there was no statistically significant difference in postoperative CCT between the FLACS and CPS groups at 1 to 3 days postoperatively. However, significantly lower CCT was observed in the FLACS group than in the CPS group at 1 week and 1 month postoperatively. At 3 months and 6 months, there was no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. Our study showed that in the CPS group, there was significantly increased CT at positions 1 and 2 at POM1 compared with the FLACS group. At POM3 and POM6, CT decreased in all positions in both groups. This implies that the perturbation of endothelial function by either FLACS or CPS is minimal, and ECs can regain normal function quickly.

Our study possesses certain strengths, such as a substantial sample size and accurate measurements, which enhance the robustness and generalizability of our findings. In addition, the utilization of precise measurements, including the NAVIS-EX automatic analyzer, enhances the accuracy and validity of our results and avoids manual counting errors. However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. First, the use of an automated analysis system is not necessarily a strength, particularly when images are not excellent, and reproducibility diminishes. Second, the retrospective design may introduce inherent biases and limitations in data collection. In Taiwan, cataract surgery fees are covered by the National Health Insurance. However, both FLACS and premium IOLs are optional self-paid procedures. This difference may introduce a bias in case selection because the patients were not recruited from the general population. Furthermore, our study is constrained by the restricted measurement periods, which might not capture longer-term effects or intricate interactions. Of note, when the ECL stabilizes at position 2 remains unknown, which may require a much longer follow-up period. Finally, the divide-and-conquer technique was used in this study, and Allan et al. found that compared with the divide-and-conquer technique, the phacoemulsification–chop technique used less phacoemulsification power; therefore, it remains unknown whether FLACS still reduces ECL when the phacoemulsification–chop technique is used. Improvement in the phacoemulsification tip design that decreases the needed ultrasound energy is another factor that should be taken into consideration. Despite these limitations, our study did not encounter much data loss during the data collection process. This indicates that we had a comprehensive and complete dataset, thereby enhancing the validity and reliability of our findings. To address these limitations, future research could consider prospective designs, longer follow-up periods, and the incorporation of measures to control for potential confounding factors.

In summary, this study highlights the topographical variation in ECD and ECL after FLACS and CPS. Although the ECL rate was significantly lower in the central cornea at 3 months after FLACS and ECL in the central and peripheral cornea stabilized at 3 months in the FLACS group, continued ECL near the corneal wound in both groups did not cease up to 6 months postoperatively. Studies with much longer follow-up times are needed to elucidate the impact of FLACS near corneal wounds.

WHAT WAS KNOWN

The topographical variation in corneal endothelial cell density (ECD) across different corneal zones has been observed, revealing higher ECD in paracentral and peripheral areas compared with the central zone.

The relationship between corneal ECD and age has been established, indicating a negative correlation between mean ECD and age.

Studies have reported mixed findings regarding endothelial cell loss (ECL) between FLACS and conventional phacoemulsification surgery (CPS), with some studies showing no significant difference and others demonstrating lower ECL with FLACS.

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS

This study revealed that the central zone exhibited significantly lower ECD compared with the peripheral zone, accompanied by a higher rate of hexagonal cells, while the coefficient of variation was significantly lower in the central zone.

The study demonstrates a significantly lower ECL in the central cornea at 3 months postoperatively with FLACS compared with CPS, suggesting that FLACS may minimize ECL and avoid additional damage to the corneal endothelium.

After phacoemulsification, ECL varied in different corneal regions and was significantly higher near the main wound. Although ECL stabilized at 3 months in the central cornea, the continued ECL at 6 months near the main wound suggested an ongoing endothelial remodeling in the region.

Footnotes

Supported in part by IIT program of Alcon Medical Affairs (IIT no. 59192625).

Presented at the 40th Congress of ESCRS, Milan, Italy, 2022.

Disclosures: None of the authors have any financial or proprietary interest in any material or method mentioned.

First author:

Altantsetseg Altansukh, MD

Sasurea Eye Clinic, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

Contributor Information

Altantsetseg Altansukh, Email: Dr.Altantsetseg@gmail.com.

Kathleen Sheng-Chuan Ma, Email: xd1121@gmail.com.

Adiyabazar Doyodmaa, Email: Doogii.adiyabazar@gmail.com.

Ning Hung, Email: shsk1212@gmail.com.

Eugene Yu-Chuan Kang, Email: yckang0321@gmail.com.

Wuyong Quan, Email: qwy0329@163.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mencucci R, Ponchietti C, Virgili G, Giansanti F, Menchini U. Corneal endothelial damage after cataract surgery: microincision versus standard technique. J Cataract Refract Surg 2006;32:1351–1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Brien PD, Fitzpatrick P, Kilmartin DJ, Beatty S. Risk factors for endothelial cell loss after phacoemulsification surgery by a junior resident. J Cataract Refract Surg 2004;30:839–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayashi K, Hayashi H, Nakao F, Hayashi F. Risk factors for corneal endothelial injury during phacoemulsification. J Cataract Refract Surg 1996;22:1079–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pereira AC, Porfirio F, Jr, Freitas LL, Belfort R, Jr. Ultrasound energy and endothelial cell loss with stop-and-chop and nuclear preslice phacoemulsification. J Cataract Refract Surg 2006;32:1661–1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dosso AA, Cottet L, Burgener ND, Di Nardo S. Outcomes of coaxial microincision cataract surgery versus conventional coaxial cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 2008;34:284–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Storr-Paulsen A, Norregaard JC, Ahmed S, Storr-Paulsen T, Pedersen TH. Endothelial cell damage after cataract surgery: divide-and-conquer versus phaco-chop technique. J Cataract Refract Surg 2008;34:996–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho YK, Chang HS, Kim MS. Risk factors for endothelial cell loss after phacoemulsification: comparison in different anterior chamber depth groups. Korean J Ophthalmol 2010;24:10–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walkow T, Anders N, Klebe S. Endothelial cell loss after phacoemulsification: relation to preoperative and intraoperative parameters. J Cataract Refract Surg 2000;26:727–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kranitz K, Takacs A, Mihaltz K, Kovacs I, Knorz MC, Nagy ZZ. Femtosecond laser capsulotomy and manual continuous curvilinear capsulorrhexis parameters and their effects on intraocular lens centration. J Refract Surg 2011;27:558–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kranitz K, Mihaltz K, Sandor GL, Takacs A, Knorz MC, Nagy ZZ. Intraocular lens tilt and decentration measured by Scheimpflug camera following manual or femtosecond laser-created continuous circular capsulotomy. J Refract Surg 2012;28:259–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mastropasqua L, Toto L, Mastropasqua A, Vecchiarino L, Mastropasqua R, Pedrotti E, Di Nicola M. Femtosecond laser versus manual clear corneal incision in cataract surgery. J Refract Surg 2014;30:27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ang RET, Quinto MMS, Cruz EM, Rivera MCR, Martinez GHA. Comparison of clinical outcomes between femtosecond laser-assisted versus conventional phacoemulsification. Eye Vis (Lond) 2018;5:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Popovic M, Campos-Moller X, Schlenker MB, Ahmed II. Efficacy and safety of femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery compared with manual cataract surgery: a meta-analysis of 14 567 eyes. Ophthalmology 2016;123:2113–2126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dzhaber D, Mustafa O, Alsaleh F, Mihailovic A, Daoud YJ. Comparison of changes in corneal endothelial cell density and central corneal thickness between conventional and femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery: a randomised, controlled clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol 2020;104:225–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bascaran L, Alberdi T, Martinez-Soroa I, Sarasqueta C, Mendicute J. Differences in energy and corneal endothelium between femtosecond laser-assisted and conventional cataract surgeries: prospective, intraindividual, randomized controlled trial. Int J Ophthalmol 2018;11:1308–1316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ye Z, Li Z, He S. A meta-analysis comparing postoperative complications and outcomes of femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery versus conventional phacoemulsification for cataract. J Ophthalmol 2017;2017:3849152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amann J, Holley GP, Lee SB, Edelhauser HF. Increased endothelial cell density in the paracentral and peripheral regions of the human cornea. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;135:584–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanathi M, Tandon R, Sharma N, Titiyal JS, Pandey RM, Vajpayee RB. In-vivo slit scanning confocal microscopy of normal corneas in Indian eyes. Indian J Ophthalmol 2003;51:225–230 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takács AI, Kovács I, Miháltz K, Filkorn T, Knorz MC, Nagy ZZ. Central corneal volume and endothelial cell count following femtosecond laser-assisted refractive cataract surgery compared to conventional phacoemulsification. J Refract Surg 2012;28:387–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conrad-Hengerer I, Al Juburi M, Schultz T, Hengerer FH, Dick HB. Corneal endothelial cell loss and corneal thickness in conventional compared with femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery: three-month follow-up. J Cataract Refract Surg 2013;39:1307–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schroeter A, Kropp M, Cvejic Z, Thumann G, Pajic B. Comparison of femtosecond laser-assisted and ultrasound-assisted cataract surgery with focus on endothelial analysis. Sensors (Basel) 2021;21:996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang H, Chen X, Xu J, Yao K. Comparison of femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery and conventional phacoemulsification on corneal impact: a meta-analysis and systematic review. PLoS One 2023;18:e0284181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abell RG, Kerr NM, Howie AR, Mustaffa Kamal MA, Allen PL, Vote BJ. Effect of femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery on the corneal endothelium. J Cataract Refract Surg 2014;40:1777–1783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abell RG, Kerr NM, Vote BJ. Toward zero effective phacoemulsification time using femtosecond laser pretreatment. Ophthalmology 2013;120:942–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Mohtaseb Z, He X, Yesilirmak N, Waren D, Donaldson KE. Comparison of corneal endothelial cell loss between two femtosecond laser platforms and standard phacoemulsification. J Refract Surg 2017;33:708–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krarup T, Ejstrup R, Mortensen A, la Cour M, Holm LM. Comparison of refractive predictability and endothelial cell loss in femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery and conventional phaco surgery: prospective randomised trial with 6 months of follow-up. BMJ Open Ophthalmol 2019;4:e000233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]