Summary

Background

Sepsis is a leading cause of mortality in intensive care units and vasoactive drugs are widely used in septic patients. The cardiovascular response of septic shock patients during resuscitation therapies and the relationship of the cardiovascular response and clinical outcome has not been clearly described.

Methods

We included adult patients admitted to the ICU with sepsis from Peking Union Medical College Hospital (internal), Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) and eICU Collaborative Research Database (eICU-CRD). The Blood Pressure Response Index (BPRI) was defined as the ratio between the mean arterial pressure and the vasoactive-inotropic score. BRRI was compared with existing risk scores on predicting in-hospital death. The relationship between BPRI and in-hospital mortality was calculated. A XGBoost's machine learning model identified the features that influence short-term changes in BPRI.

Findings

There were 2139, 9455, and 4202 patients in the internal, MIMIC-IV and eICU-CRD cohorts, respectively. BPRI had a better AUROC for predicting in-hospital mortality than SOFA (0.78 vs. 0.73, p = 0.01) and APS (0.78 vs. 0.74, p = 0.03) in the internal cohort. The estimated odds ratio for death per unit decrease in BPRI was 1.32 (95% CI 1.20–1.45) when BPRI was below 7.1 vs. 0.99 (95% CI 0.97–1.01) when BPRI was above 7.1 in the internal cohort; similar relationships were found in MIMIC-IV and eICU-CRD. Respiratory support and latest cumulative 12-h fluid balance were intervention-related features influencing BPRI.

Interpretation

BPRI is an easy, rapid, precise indicator of the response of patients with septic shock to vasoactive drugs. It is a comparable and even better predictor of prognosis than SOFA and APS in sepsis and it is simpler and more convenient in use. The application of BPRI could help clinicians identify potentially at-risk patients and provide clues for treatment.

Funding

Fundings for the Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation; the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding; the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) from Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and the National Key R&D Program of China, Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China.

Keywords: Septic shock, Vascular reactivity, Mortality, Machine learning, Dynamic risk model

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

All English-language articles were screened until 2023 in PubMed to identify studies that used “arterial tone”, “vasoactive” and “response” in sepsis patients. To date, there have been no studies focusing on the indicator reflecting transient responsiveness to vasoactive drugs in patients with sepsis and its clinical value, and there was a lack of convenient manufacturers to reflect arterial tone. We found several studies1, 2, 3, 4 that attempted to explore the predictive ability of the vasoactive-inotropic score in predicting mortality in sepsis shock or attempted to use surrogates to reflect arterial load with neglect of treatment.5, 6, 7 However, most of the previously cited studies were focused on newborns or children or were based on single-center. Moreover, these studies were based on single-center design whereas the finding requires external validation.

Added value of this study

The current multicenter study, we proposed an indicator called the Blood Pressure Response Index (BPRI), which is easily and quickly obtained and can reflect the cardiovascular response to vasoactive drugs in sepsis patients. The AUROCs of BPRI for predicting in-hospital mortality were 0.78 (95% CI 0.75–0.81), 0.74 (95% CI 0.73–0.74), and 0.74 (95% CI 0.72–0.76) in internal, MIMIC-IV, and eICU-CRD cohorts, respectively. Furthermore, we investigate the relationship of BPRI and in-hospital mortality, proving that there was the L-shaped in the internal cohort as well as external cohorts. When BPRI was less than the cut-point, the risk of in-hospital mortality increased rapidly with decreasing BPRI. When BPRI was greater than the cut-point, the risk of in-hospital mortality decreased slowly with increasing BPRI. In addition, we also explored which clinical features may be related to changes in BPRI by a machine learning method.

Implications of all the available evidence

The proposed BPRI, is an easy, rapid, precise indicator of the response of patients with septic shock to vasoactive drugs. It is a comparable and even better predictor of prognosis than SOFA and APS in sepsis and it is simpler and more convenient in use, which could help clinicians identify potentially at-risk patients and provide clues for treatment.

Introduction

Septic shock, a form of distributive shock whose main physiopathological characteristics are a decrease in peripheral vascular resistance and an alteration in oxygen extraction, is the most common form of shock in intensive care unit (ICU) patients.8 It results in the death of more than a quarter of sufferers.9 Vasoactive drugs are widely used in septic patients due to their persistent hypotension.10 The cardiovascular response of septic shock patients during resuscitation therapies has not been clearly described.

Through various mechanisms, sepsis reduces vascular tone, induces hypotension and decreases tissue perfusion. Despite stable cardiac output, impaired regional blood flow distribution due to modulation of regional arterial tone could affect splanchnic perfusion.11 But there are no convenient and noninvasive markers for precisely evaluating arterial tone.12,13 According to the Windkessel model, left ventricular end-systolic pressure (LVESP) divided by stroke volume (SV) can be used as a metric of effective arterial elasticity5 and can also serve to evaluate arterial load.6 SV can be accurately estimated by bedside monitoring in the ICU, but LVESP still requires a surrogate. Pinsky proposed that the ratio of pulse pressure variation (PPV) to stroke volume variation (SVV) during a single positive-pressure breath can provide a functional evaluation of arterial tone.14, 15, 16 In animal experiments, 90% of systolic pressure, mean arterial pressure (MAP) and dicrotic notch pressure have been used to estimate LVESP.7 Pulse contour analyses (MostCare®, Vygon, Italy) have also been applied to assess LVESP.17 The above assessments are either invasive or deviate from the real clinical status and do not allow easy, fast, economical estimation.

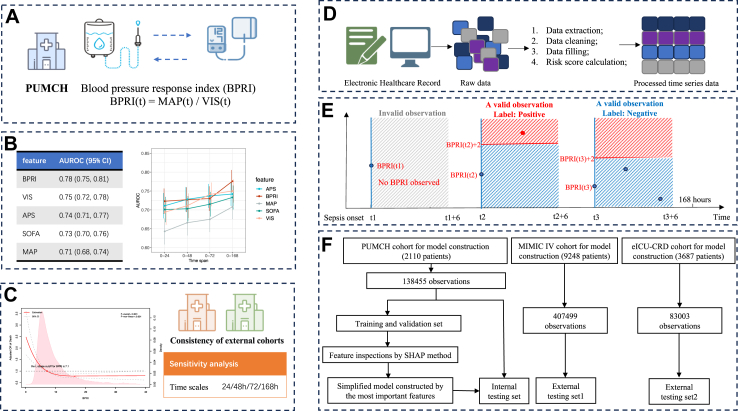

Therefore, we devised a dose‒effect index named the blood pressure response index (BPRI), which was calculated by dividing the MAP at a given time point by the vasoactive-inotropic score (VIS) (Fig. 1A) and reflects the responsiveness of sepsis patients to vasoactive drugs, to achieve a real-time and convenient representation of patients' vascular situation.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the study design and workflow. A: Blood pressure response index (BPRI) proposed. B: Comparison of AUROCs for predicting in-hospital mortality between BPRI and other variables for different time spans. C: Relationship between BPRI and risk of in-hospital mortality. D: Dynamic risk model of BPRI change: data extraction procedure. E: Dynamic risk model of BPRI change: dataset construction and outcome definition. F: Dynamic risk model of BPRI change: flowchart of the study design.

The primary objective of this study was to compare the ability of BPRI to predict in-hospital mortality in sepsis patients with that of widely used clinical scores, including the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score and Acute Physiology Score (APS, a component of Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II). The secondary objective of this study was to quantify the relationship between BPRI of early stage of sepsis (within 7 days after sepsis diagnosis) and in-hospital mortality. Furthermore, after discovering such a dose–effect index and proving its efficacy at indicating in-hospital mortality, we developed a prediction model that dynamically predicts short-term changes in the dose–effect index to identify which factors influence changes in BPRI.

Methods

Study population

This was a multicenter retrospective study utilizing data from three cohorts. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH, ethics number: I-23PJ1416). The internal cohort was collected from PUMCH, while two validation cohorts were included from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) database and the eICU Collaborative Research Database (eICU-CRD) database. MIMIC-IV is a longitudinal, single-center database including 247, 366 individuals and 196, 527 adults admitted to the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center from 2008 to 2019. Wei Pan, a member of the China-NCCQC group (Record ID 55009879), is certified to get access to the database and is responsible for data extraction. The eICU-CRD is a multi-center ICU database developed by Philips Healthcare encompassing more than 200, 000 ICU admissions from 208 different ICUs in the United States between 2014 and 2015.

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: 1) Patients diagnosed with sepsis and admitted to the ICU. 2) Patients aged 18 years or older. 3) Patients who had received at least one of vasoactive drugs (dopamine, dobutamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine, vasopressin, or milrinone) within the early stage of sepsis. Patients with unknown dose of vasoactive drugs were excluded. The diagnosis of sepsis was based on the Sepsis-3 criteria10: documented infection (with signs of infection and treated with antibiotics for more than 48 h) plus an increase in SOFA score of 2 points or more. Sepsis onset (time zero) was defined as the time when the patient met the two criteria mentioned above. Patients were followed to time of discharge or in-hospital death.

Comparison of BPRI and other scores

BPRI was calculated by dividing the MAP at a given time point by the vasoactive-inotropic score (VIS) (Fig. 1A). VIS is calculated as follows: doses of dopamine (μg/kg/min) + dobutamine (μg/kg/min) + epinephrine (μg/kg/min) × 100 + norepinephrine (μg/kg/min) × 100 + vasopressin (U/kg/min) × 10,000 + milrinone (μg/kg/min) × 10.18 A VIS of 0 was assigned if no vasoactive drugs were administered during the specific hour. Hourly VIS and MAP were used to calculate BPRI for each time point within the 7-day period following sepsis diagnosis.

The primary outcome of interest was in-hospital mortality. To fairly compare the ability of BPRI to predict in-hospital mortality with that of SOFA score and APS, we recorded the minimum value of BPRI, which representing the worst condition, along with the corresponding MAP and VIS at the time of the minimum BPRI, the maximum SOFA score, and the maximum APS within different time spans (24/48/72/168 h) following sepsis diagnosis (Fig. 1B).

Since the median age of patients in the external cohorts was 69 years, which is higher than that in the internal cohort (60 years), and there were differences in mortality rates, we conducted stratified analyses based on age group. Specially, we repeated the analyses for two groups: patients aged 70 years and under and those aged over 70 years, to explore potential subgroup effects.

The relationship of BPRI and in-hospital mortality

To quantify the relationship between BPRI of early stage of sepsis and in-hospital mortality. The minimum value of BPRI within the 7-day period following sepsis diagnosis was identified for each patient. If a non-linear relationship was observed, a two-piecewise multivariate logistic regression (segmented logistic regression) analysis was performed to fit each interval based on the cut-off value of the curve. Sensitivity analysis was conducted by repeating the procedures mentioned above at different time spans (24/48/72/168 h) in different cohorts (Fig. 1C).

Feature inspection by modeling

Five widely used algorithms, including extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), Logistic Regressuib (LR), Decision Tree (DT), Random Forest (RF), and Gradient boosting machine (GBM) were used to develop prediction models and to identify which factors might influence the short-term changes in BPRI (Fig. 1D, E & F). We then selected the best-performing algorithm to construct the final model. The SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method and dependency plots were used to detect important features and to analyze the relationships between features and changes in BPRI.

The clinical features included both baseline and hourly recorded longitudinal features. The baseline features included demographic information and comorbidities. The hourly recorded longitudinal features included laboratory test results, vital signs, SOFA score, systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) score, urine volume, fluid balance, medication and other treatments. The longitudinal data collection started three days before the diagnosis of sepsis and continued to seven days after diagnosis, ICU discharge or death. The observations where BPRI was valid for the current hour and there was at least one valid value within the following 6 h formed the modeling dataset. The outcome was defined as the increase in BPRI. Specifically, an observation was considered positive if, within the following 6 h, there was at least one valid BPRI that exceeded the current hour's BPRI value by more than 2. Otherwise, the observation was considered negative (Fig. 1E). Formal sample size calculation was not conducted. Of the 1477 patients (70% of the PUMCH cohort) in the internal training cohort, assume that 10% met the outcome definition. According to the guideline of 10 events per feature,19 this dataset is large enough to construct prediction models with at least fourteen predictors.

For continuous features, the outliers were defined as those less than the 0.25% quantile or greater than the 99.75% quantile and were treated as missing values. Missing values were imputed from the last valid measurement. Features with more than 40% missing values after data imputation were removed from the analysis. For algorithms comparison, the remaining features with equal or less than 40% missing values were imputed using random forests (RF) method of Python package “miceforest”.

The patients who met the criteria of the internal cohort were randomly divided into a training set and an internal testing set at a 7:3 ratio. The observations from the training set were used for model training, parameter optimization, and feature inspection. Fivefold cross-validation was performed within the training set to optimize the parameters. The observations from the internal testing set were used for model evaluation. To validate the representativeness of the important features, a simplified model was constructed using the top ten features obtained from the full model built by all included features and was evaluated on the internal testing set and the MIMIC-IV and eICU-CRD cohorts.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) and were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables are expressed as numbers and percentages. Pearson's χ2 test or Fisher's exact test was used for categorical data, as appropriate. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) was used to evaluate the performance of the minimum of BPRI and other risk scores at different time points for predicting in-hospital mortality, which was a cross-sectional analysis and as a performance evaluation metric for dynamic model, which included both static and longitudinal features. DeLong's test20 was used to compare the AUROCs. The association between BPRI and in-hospital mortality was evaluated with continuous-scale restricted cubic spline (RCS) curves based on a logistic regression model using the R package “rcssci”. The cut-off points were determined based on likelihood-ratio test and bootstrap resampling method using the R package “segmented”. To balance the best fit and overfitting in the main splines for mortality, a number of knots between three and seven was chosen as the lowest value for the Akaike information criterion. We adjusted the splines for patient age, sex, SOFA score, and calendar year groups (2008–2010, 2011–2013, 2014–2016, 2017–2019, and 2020–2022). All p values were 2-tailed, and a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with Python 3.9 and R4.2.2.

Role of funding source

The funders played no role in study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Results

Study population and baseline characteristics

From the 3048 patients with sepsis admitted to the ICU at Peking Union Medical College Hospital between June 8, 2013 and October 12, 2022, a total of 2139 ICU stays were included. Out of 26,780 sepsis ICU stays from 2008 to 2019 in the MIMIC-IV cohort and 19,598 sepsis ICU stays from 2014 to 2015 in the eICU-CRD cohort, 9455 and 4202 ICU stays were included in the MIMIC-IV and eICU-CRD cohorts, respectively. The inclusion and exclusion processes are shown in Fig. S1. The clinical characteristics of the patients in each cohort are reported in Table 1 and Tables S1–S3. The in-hospital mortality rates in the overall internal cohort, MIMIC-IV cohort, and eICU-CRD cohort were 17.1%, 25.9%, and 23.3% (p < 0.001), respectively. The median age of the three cohorts were 60, 68.7, and 69 (p < 0.001), while the median lengths of ICU stay were 6.0, 4.6, and 3.0 days (p < 0.001), respectively.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| PUMCH cohort (n = 2139) | MIMIC cohort (n = 9455) | eICU cohort (n = 4202) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General characteristics | |||

| Male, n (%) | 1330 (62.2) | 5479 (57.9) | 2126 (50.6) |

| Age, median (IQR) | 60.0 [48.0,69.0] | 68.7 [58.2,78.7] | 69.0 [58.0,79.0] |

| BPRI (minimum of 168 h), median (IQR) | 4.7 [2.1, 9.9] | 3.7 [1.7, 8.0] | 3.9 [1.6, 8.6] |

| SOFA (maximum of 168 h), median (IQR) | 13.0 [11.0, 16.0] | 7.0 [5.0, 10.0] | 10.0 [8.0, 12.0] |

| APS (maximum of 168 h), median (IQR) | 15.0 [10.0, 21.0] | 14.0 [10.0, 19.0] | 19.0 [15.0, 25.0] |

| Vosoactive drug and dosage used for the first time after sepsis diagnosis | |||

| Dopamine, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 478 (5.1) | 301 (7.2) |

| Dopamine, median (IQR) | 0 [0.0, 0.0] | 5.0 [3.0, 7.5] | 7.3 [3.2, 18.0] |

| Dobatamine, n (%) | 36 (1.7) | 211 (2.2) | 34 (0.8) |

| Dobatamine, median (IQR) | 2.6 [2.0, 3.8] | 2.5 [2.5, 5.0] | 5.0 [2.5, 5.0] |

| Epinephrine, n (%) | 468 (21.9) | 985 (10.4) | 29 (0.7) |

| Epinephrine, median (IQR) | 0.1 [0.0, 0.1] | 0.0 [0.0, 0.1] | 0.1 [0.1, 0.1] |

| Norepinephrine, n (%) | 1885 (88.1) | 7519 (79.5) | 3898 (92.8) |

| Norepinephrine, median (IQR) | 0.1 [0.0, 0.2] | 0.1 [0.1, 0.20] | 0.1 [0.0, 0.2] |

| Pituitrin, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 169 (4.0) |

| Pituitrin, median (IQR) | 0 [0.0, 0.0] | 0 [0.0, 0.0] | 0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| Millinone, n (%) | 90 (4.2) | 237 (2.5) | 16 (0.4) |

| Millinone, median (IQR) | 0.2 [0.1, 0.2] | 0.3 [0.3, 0.4] | 0.7 [0.4, 2.5] |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hematological cancer, n (%) | 122 (5.7) | 423 (4.5) | 71 (1.7) |

| Nonhematological cancer, n (%) | 455 (21.3) | 1715 (18.1) | 193 (4.6) |

| Respiratory system disease, n (%) | 1051 (49.1) | 7182 (76.0) | 2207 (52.5) |

| Neurological disease, n (%) | 291 (13.6) | 4980 (52.7) | 434 (10.3) |

| Endocrine disease, n (%) | 983 (46.0) | 6422 (68.0) | 1124 (26.7) |

| Digestive disease, n (%) | 1046 (48.9) | 7033 (74.4) | 558 (13.3) |

| Hematological disease, n (%) | 737 (34.5) | 6755 (71.5) | 733 (17.4) |

| Urogenital disease, n (%) | 863 (40.3) | 6981 (73.9) | 2122 (50.5) |

| Circulatory system disease, n (%) | 1732 (81.0) | 8777 (92.9) | 1702 (40.5) |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 79 (3.7) | 270 (2.9) | 16 (0.4) |

| Acute renal failure, n (%) | 360 (16.8) | 5221 (55.2) | 1327 (31.6) |

| Sepsis diagnosis | |||

| HR, median (IQR) | 96.0 [85.0, 109.0] | 88.0 [77.0, 103.0] | 90.0 [75.0, 104.2] |

| RR, median (IQR) | 18.0 [15.0, 21.0] | 20.0 [17.0, 25.0] | 19.0 [16.0, 24.0] |

| SAP, median (IQR) | 123.0 [110.0, 137.0] | 103.0 [93.0, 117.0] | 98.0 [85.0, 113.0] |

| DAP, median (IQR) | 65.0 [58.0, 72.0] | 56.0 [48.0, 65.0] | 55.0 [47.0, 65.0] |

| MAP, median (IQR) | 84.0 [76.0, 92.0] | 72.0 [64.3, 81.7] | 58.0 [50.0, 67.0] |

| FiO2, median (IQR) | 35.0 [30.0, 40.0] | 60.0 [50.0, 100.0] | 44.0 [28.0, 100.0] |

| PCO2, median (IQR) | 42.0 [37.0, 46.8] | 41.0 [36.0, 47.0] | 38.0 [31.0, 47.8] |

| PLT, median (IQR) | 130.0 [86.0, 182.0] | 180.0 [125.0, 247.2] | 192.0 [126.0, 272.0] |

| TBIL, median (IQR) | 18.2 [11.9, 30.6] | 13.7 [6.8, 29.1] | 12.0 [6.8, 22.2] |

| Crea, median (IQR) | 84.0 [64.0, 126.0] | 106.1 [70.7, 176.8] | 156.5 [97.2, 255.5] |

| WBC, median (IQR) | 12.7 [8.7, 17.2] | 12.2 [8.1, 17.4] | 13.8 [8.7, 19.8] |

| pH, median (IQR) | 7.4 [7.4, 7.5] | 7.4 [7.3, 7.4] | 7.3 [7.3, 7.4] |

| Lac, median (IQR) | 2.0 [1.3, 3.6] | 2.1 [1.4, 3.4] | 2.4 [1.5, 4.1] |

| PT, median (IQR) | 14.4 [13.3, 16.0] | 14.7 [12.9, 17.9] | 15.6 [13.8, 19.5] |

| APTT, median (IQR) | 35.3 [29.3, 43.3] | 33.6 [29.0, 44.2] | 33.0 [29.0, 39.9] |

| Cl, median (IQR) | 109.0 [105.5, 112.0] | 103.0 [99.0, 108.0] | 102.0 [97.0, 107.0] |

| Hb, median (IQR) | 103.0 [88.0, 117.0] | 102.0 [88.0, 118.0] | 109.0 [93.0, 126.0] |

| Glu, median (IQR) | 9.5 [7.8, 11.6] | 13.1 [10.4, 17.4] | 12.4 [10.0, 16.5] |

| Teatment of sepsis diagnosis | |||

| Dopamine, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 160 (1.7) | 137 (3.3) |

| Dobatamine, n (%) | 24 (1.1) | 87 (0.9) | 13 (0.3) |

| Epinephrine, n (%) | 439 (20.5) | 307 (3.2) | 13 (0.3) |

| Norepinephrine, n (%) | 1507 (70.5) | 1353 (14.3) | 1352 (32.2) |

| Pituitrin, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 84 (2.0) |

| Millinone, n (%) | 83 (3.9) | 91 (1.0) | 3 (0.1) |

| Respiratory_support, n (%) | 1301 (60.8) | 2199 (23.3) | 1114 (26.5) |

| Clinical outcomes | |||

| Mortality (in-hospital), n (%) | 366 (17.1) | 2453 (25.9) | 979 (23.3) |

| ICU LOS, median (IQR) | 6.0 [3.5, 11.7] | 4.6 [2.5, 9.1] | 3.0 [1.7, 5.7] |

BPRI, blood pressure response index; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment; APS, acute physiology score; HR, heart rate; RR, respiratory rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; PaCO2, arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PLT, platelet count; TBIL, total bilirubin; Crea, creatinine; WBC, white blood cell count; Lac, lactic acid; PT, prothrombin time; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; Cl, chlorion; Hb, hemoglobin; Glu, serum glucose; ICU, intensive care unit.

Comparison of BPRI and other scores

Within the first 168 h following sepsis diagnosis, the AUROCs (95% CI) of BPRI, MAP, VIS, SOFA score, and APS for predicting in-hospital mortality were 0.78 (0.75, 0.81), 0.71 (0.68, 0.74), 0.75 (0.72, 0.78), 0.73 (0.70, 0.76) and 0.74 (0.71, 0.77), respectively. DeLong's test showed that BPRI had an overall superior ability to predict in-hospital mortality compared to other indices within 168 h (all p values were less than 0.05). In the MIMIC-IV cohort, BPRI performed better than APS (0.74 vs. 0.72, p = 0.02). There were no significant differences between AUROCs of BPRI and SOFA score in the MIMIC cohort (0.74 vs. 0.75, p = 0.10) and eICU-CRD cohort (0.74 vs. 0.73, p = 0.55), respectively. On other time spans, the AUROCs of BPRI were all above 0.7, which fell between those of SOFA score and APS. The details of the AUROCs on different time spans in the three cohorts are shown in Table S4 and Fig. 2. Taken together, these data indicate a noninferior predicative capability for in-hospital mortality compared with SOFA score and APS. As a non-invasive, convenient marker, BPRI has a potential clinical application value.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of AUROCs for predicting in-hospital mortality between BPRI, MAP, VIS, SOFA score, and APS within different time spans. A: internal (PUMCH) cohort: The BPRI had a superior ability to predict in-hospital mortality compared to other indices within the first 24 h, 48 h and 168 h following sepsis diagnosis. B: MIMIC-IV cohort: The BPRI outperformed the APS across all time windows and was equivalent to the SOFA score within the first 168 h following sepsis diagnosis in predicting in-hospital mortality. C: eICU-CRD cohort: The BPRI had a superior or equal performance in predicting in-hospital mortality compared to the SOFA score across all time spans. APS, Acute Physiology Score; BPRI, blood pressure response index; MAP, mean arterial pressure; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; VIS, vasoactive-inotropic score.

In the subgroup of patients over 70 years, within the internal cohort, the AUROCs for BPRI in predicting in-hospital mortality was consistently higher than that for SOFA and APS across all time spans examined. In the MIMIC-IV cohort, BPRI demonstrated superior predictive accuracy compared to APS and showed no statistically significant difference when compared to SOFA. In the eICU-CRD cohort, BPRI was found to be superior to SOFA, with no statistically significant difference compared to APS. Detailed results of subgroup analysis are shown in Table S5. Additionally, the comparative results (Table S6 & Fig. S2) between models containing only SOFA and APS, as well as models with BPRI combined with SOFA and APS, showed that the inclusion of BPRI significantly enhances the predictive accuracy of in-hospital mortality, suggesting that BPRI provides addition information beyond what is not captured by SOFA and APS alone.

The relationship of BPRI and in-hospital mortality

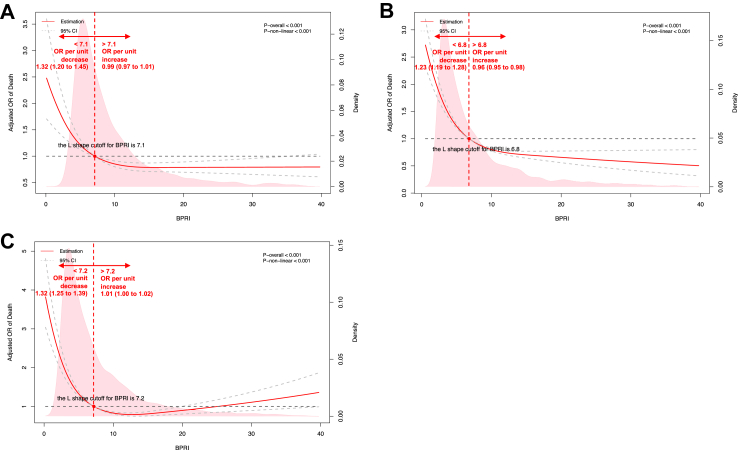

The association between BPRI and the risk of in-hospital mortality was L-shaped in the internal cohort (Fig. 3A). The BPRI value separating the two parts of this L-shaped curve was 7.1: When BPRI was less than 7.1, the risk of in-hospital mortality increased rapidly with decreasing BPRI. When BPRI was greater than 7.1, the risk of in-hospital mortality decreased slowly with increasing BPRI (p for nonlinearity <0.001). Below BPRI = 7.1, the odds ratio (OR) per unit decrease was 1.32 (1.20–1.45); above BPRI = 7.1, the OR per unit increase was 0.99 (0.97–1.01).

Fig. 3.

The restricted cubic spline for the relationships between BPRI (the minimum value within 168 h after sepsis diagnosis) and in-hospital mortality in three cohorts. Similar L-shaped relationship curves and cut-off values were observed in the three cohorts: when BPRI was below the cut-off value, the risk of in-hospital mortality increased rapidly with decreasing BPRI; when BPRI was above the cut-off value, the risk of in-hospital mortality changed slightly with increasing BPRI. A: internal (PUMCH) cohort (cutoff value is 7.1). B: MIMIC-IV cohort (cutoff value is 6.8). C: eICU-CRD cohort (cutoff value is 7.2). Estimates adjusted for age, gender, SOFA score, and group of calendar year. OR, odds ratio. The solid red line represented the estimated ORs and the dashed grey lines represented corresponding 95% confidence intervals. The horizontal dashed grey line and the red dot indicated the reference value. Solid pink curves show the fraction of the population with different level of BPRI. The p value for overall association <0.05 manifested a significant association, whatever the shape of the relationship curve was. The p value for non-linear association <0.05 indicated a nonmonotonic dose–response curve, otherwise, a monotonic relationship was suggested.

Similar L-shaped relationships were seen in the MIMIC-IV and eICU-CRD cohorts, with BPRI cutoff values of 6.8 and 7.2, respectively (Fig. 3B & C). The relationships and ORs of in-hospital mortality for patients in different risk strata are shown in Fig. 3. The sensitivity results at different time spans are listed in Table S7.

Feature inspection by modeling

A total of 96,986, 41,469, 407,499, and 83,003 observations were generated from the included ICU stays in the internal training, internal holdout testing, MIMIC-IV, and eICU-CRD cohorts, respectively (Fig. 1F). The positive rates of the four cohorts were 7.56%, 7.84%, 7.66%, and 14.15%, respectively. A total of 142 features (Table S8) were included. The distribution of dynamic features in training and internal holdout testing cohorts are shown in Tables S9 & S10. The candidate and selected parameters of algorithms comparison are listed in Table S11.

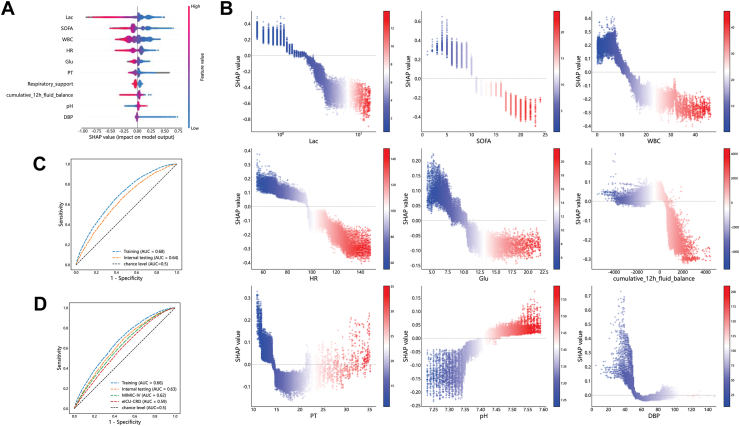

The results of different algorithms are shown in Table S12. Of the considered machine learning algorithms, the XGBoost performed better than other algorithms. To improve the usability of clinical application, as not all variables were available every hour, we selected the algorithm XGBoost to build the final model on the dataset without RF-imputed. The top-ranked features are compared between groups in Table S13 and Fig. S3. The top ten of these features were lactate level, SOFA score, white blood cell count (WBC), heart rate (HR), glucose level, prothrombin time (PT), respiratory support, cumulative 12-h fluid balance, pH, and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) (Fig. 4A & B). The AUROCs of the full model and the simplified model, which was constructed by the top ten features, in the internal testing set were 0.64 (0.63, 0.65) and 0.63 (0.62, 0.64), respectively (Fig. 4C & D). The AUROCs of the simplified model in the MIMIC-IV and eICU-CRD cohorts were 0.62 (0.61, 0.62) and 0.59 (0.58, 0.60), respectively (Fig. 4D). Missing status of the top ten features were shown in Table S14.

Fig. 4.

Feature inspection and model evaluation. A: SHAP summary plot for the top 10 features of the dynamic risk model (full model). B: SHAP dependence plot for the top 10 continuous features of the dynamic risk model (full model). The x-axis represents the actual values and the y-axis represents the SHAP values. Each dot represents an observation. Colorbar scale represents the actual values of feature, the greater the value, the redder the color. SHAP values for specific features that exceeding zero represents an increased probability of the increase in BPRI. C: ROC curves for dynamic risk model of the training, internal testing cohort (full model). D: ROC curves for simplified dynamic risk model of the training, internal testing, MIMIC-IV, and eICU-CRD cohort. Abbreviations: Lac, lactate level; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment; WBC, white blood cell count; HR, heart rate; Glu, glucose; PT, prothrombin time; DBP, diastolic blood pressure.

Discussion

In this study, we propose a rapid, noninvasive dose-effect index to reflect the cardiovascular response of septic shock patients. We evaluate the relationships between BPRI and in-hospital mortality and which factors influence the changes in BPRI. Our study has three important findings: (a) As a single marker, BPRI exhibited a same or even better predicative capability for in-hospital mortality compared with SOFA score and APS. (b) We found an L-shaped relationship between BPRI and the risk of in-hospital mortality in both internal and external cohorts, with cutoff values of 7.1, 6.8 and 7.2. (c) We found important features associated with short-term dynamic changes in BPRI, which were clinically interpretable.

Previous studies have investigated dynamic arterial elastance (Eadyn), the ratio of PPV to SVV during mechanical breathing14,16; however, these studies were limited to animal models and struggled to identify an accurate surrogate for PPV or reflect clinical interventions.7,17,21 Eadyn cannot accurately reflect arterial elastance because it is measured only during a single breath and is influenced by a number of factors.22 If the tidal volume fluctuates, this leads to increased pleural pressure due to the lung volume when breathing under positive pressure, causing the filling of the LV to change even though the actual arterial elastance remains unchanged.23,24 Vascular tone elasticity undeniably plays a crucial role in determining blood pressure, but it is important to note that blood pressure is influenced by other factors, such as vascular nontension elasticity, ventricular-arterial coupling,25,26 and blood volume. Vasoactive drugs, including adrenergic agents combining α-, β-, and/or dopaminergic stimulation, are commonly used to achieve hemodynamic stability in patients with septic shock. For instance, consensus guidelines recommend norepinephrine as a first-line therapy.8,27 It binds to α-adrenergic receptors and induces vasoconstriction, increasing the proportion of pressed blood volume28 and exerting a fluidlike effect.29,30 Inotropes are indicated when the function of the myocardium is impaired, and dobutamine remains the first-line therapy.31 That is, although patients may have the same MAP, their actual condition can be vary because of the different interventions. If treatment were neglected, the studies’ results would be indistinguishable from the actual condition of the patient. To date, there has been a lack of evidence-based medicine for the investigation of vascular elasticity in large samples. Studies have been limited to animal models or alternatives that require invasive manipulation of indices, and the impact of clinical interventions has not been considered. Therefore, we are trying to construct a real-world based, easy-to-use indicator that reflects real-time changes to compensate for the above shortcomings and dynamically assess the reactivity of vasoactive drugs, providing an accurate picture of the current state of the disease based on actual clinical data. MAP is influenced by cardiac output and systemic vascular resistance and forms the basis for autoregulation by vital organs such as the heart and kidneys.32,33 The vasoactive-inotropic score (VIS), can be used to objectively quantify the degree of haemodynamic support. We have tried to link MAP and VIS through mathematical operations that dynamically reflect how vasoactive drugs affect blood pressure.

When investigating the correlation between BPRI and inpatient mortality in the internal cohort, we observed a distinct L-shaped relationship whereby mortality rates were considerably higher when BPRI fell below the cutoff value (Fig. 3). The identification of the cut off value is of clinical significance as it allows for risk stratification and enable physicians to promptly evaluate a patient's prognosis at the bedside. Patients with BPRI values of greater than 7.1 had a lower risk of death and those with values of less than 7.1 had a higher risk. When BPRI was less than 7.1, the risk of in-hospital mortality increased rapidly with decreasing BPRI and aggressive treatment may be considered. Currently available sepsis screening tools have not demonstrated such a clear stratification of patient prognosis. Early warning of mortality risk can be achieved in patients administered vasoactive drugs by analyzing only blood pressure at the bedside in seconds, without the wait for lab tests. This is superior to current screening tools such as SOFA and APS, which reflect multi-organ dysfunction and are dependent on laboratory tests. In contrast to vasoactive drug responsiveness, which is a per-second change, the impairment on organ function necessitates adequate mapping time. The BPRI presents an opportunity for timely intervention prior to organ dysfunction, aligning with the urgent emphasis of the sepsis survival campaign on early diagnosis and treatment, as the risk of death from septic shock increases with each hour of delay in appropriate treatment.34 Importantly, despite the slight differences in the cut off values across three cohorts, they are remarkably close, further reinforcing the validity and generalizability of the findings. This consistency suggests that the identified BPRI cut off values have relevance across different patient populations and settings, emphasizing their generalisability and potential utility in clinical practice.

As a non-invasive and convenient marker in predicting in-hospital mortality, the AUROCs of BPRI consistently above 0.7 across different time spans, indicating its robust accuracy and stability in early risk assessment for sepsis patients. When comparing BPRI with the SOFA and APS in three cohorts, it exhibited noninferior prediction accuracy for mortality throughout the various observation periods, indicating its consistency. Subgroup analyses demonstrated that BPRI exhibited a more pronounced advantage over SOFA or APS in predicting prognosis in an older population (>70 years of age) with poorer vascular status. In other words, BPRI is considered to be a more effective marker in populations with poorer vascular function. Furthermore, a comparison of the predictive performance of models utilizing SOFA and APS individually with those incorporating BPRI, SOFA, and APS revealed that the incorporation of BPRI led to an enhancement in model performance, indicating that BPRI provides distinctive information that surpasses that which can currently be captured by SOFA and APS, which can optimize risk assessment. In addition, the BPRI requires fewer indicators, can be scored quickly at the bedside, and is timely and operational, making it suitable for clinical promotion. BPRI is more user-friendly and quicker than the extensive indicator collection process of these assessment tools, and demonstrates good performance in both stand-alone and joint applications.

As an indicator of vasoactive drug responsiveness, BPRI could be influenced by different factors. Disturbances in the production of NO and reactive oxygen species (ROS), prostacyclin and endothelin have resulted in regional changes in vascular tone and permeability in patients with sepsis,35, 36, 37 leading to a decrease in blood volume and refractory hypotension.38 In the real world, it may be important to know which interventions have an effect on BPRI, as the discovery and understanding of such factors has been critical in guiding treatment decisions. To address this issue, we adopted a machine learning-based data-driven approach: a machine learning model was developed to predict dynamic short-term changes in BPRI, and feature analysis by an explainable machine learning approach revealed the most important factors (Fig. 4A) affecting the short-term changes in BPRI. These factors include lactate level, SOFA score, WBC, heart rate, and glucose level. Our randomized controlled trial has demonstrated the great benefit of stepwise lactate kinetics-oriented hemodynamic therapy,39 and blood lactate levels have been emphasized by the SSC guidelines.27 In addition, vital signs and laboratory results are consistent with current clinical findings, with a leukocyte count <10 × 109, SOFA score <10, heart rate <100 bpm, normal-range blood glucose value and lower creatinine value among the indicators of improvement in the patient's clinical symptoms, all of which are associated with an elevated BPRI. This further validates the clinical interpretability of BPRI.

Two intervention-related features, respiratory support and the latest cumulative 12-h fluid balance prior to the observation point, were associated with changes in BPRI in this study. In general, patients who do not require respiratory support have less severe disease and higher BPRI values. Interestingly, the SHAP dependence plot (Fig. 4B) showed a distinct bipolar distribution in fluid balance, whereby negative fluid balance increased BPRI, indicating an improvement in the responsiveness to vasoactive drugs. Note that fluid balance was calculated as the sum of the total 12 h, occurring at least 12 h after sepsis onset. A correlation was found between negative fluid balance and improvement in BPRI by analyzing a large sample of real-world clinical data. This is despite the fact that real-world based studies are affected by the intertwining of patient status and clinical interventions, meaning that the amount of fluid balance in a patient is affected by both changes in the patient's condition and interventions. Nevertheless, the correlations derived from real-world research findings could provide direction for clinical treatment. Although the SSC guidelines proposed that establishing vascular access and initiating aggressive fluid resuscitation are the first priorities in the management of patients with severe septic shock27 and have proven helpful,40 a growing number of studies have shown a positive correlation between mortality and the persistence of daily positive fluid balance in septic patients.41, 42, 43 Thus, the optimal fluid resuscitation volume is still under debate. Meyhoff et al. and Sivapalan et al. successively conducted systematic reviews with meta-analyses of nine and thirteen randomized clinical trials, respectively, and found no significant effect of fluid volume on total mortality in patients with sepsis, though there was a relatively low quantity and quality of evidence to support the conclusion.44,45 Better-designed trials are needed in this field. Our study, as a large observational study at a national medical center with external validation in two large international public databases, demonstrated that it might be worth attempting a negative fluid balance in patients who respond well to vasoactive agents, with the hope of improving prognosis.

This study had several limitations. First, as it was a retrospective study, although the findings of BPRI and its ability to predict in-hospital mortality were validated in both internal and external cohorts, the level of evidence needs to be improved by validation in additional cohorts and prospective studies. Furthermore, without prospective studies, the extent to which patients actually benefit from the use of BPRI has not been determined. Additionally, the interplay of fluid resuscitation, intervention measures, and the complex clinical course of sepsis patients may introduce confounding factors that are difficult to control for in an observational study, but which are one of the characteristics of real-world research. Our findings indicate a strong correlation between factors such as lactate levels, fluid balance, and short-term changes in BPRI, which should be considered as indicative of potential associations that could guide future research directions. Finally, in observational studies of big data, algorithmic bias is unavoidable and can cause machine-learned results to deviate from the real world.46 This bias was a potential drawback of our study. Even so, such algorithmic bias was not severe enough to affect the reliability of our findings, as our conclusions are supported by evidence from multinational, multiethnic external cohorts.

Conclusion

We propose the use of the novel dose–effect index, BPRI, to allow rapid bedside assessment of the reactivity of septic shock patients to vasoactive drugs, as isolated MAP or VIS cannot reflect this feature. BPRI had a comparable AUROC than SOFA and APS for predicting in-hospital mortality and was more user-friendly and efficient. Also, the BPRI demonstrated a significant cut-off value in predicting prognosis, with patients less than the cut-off value having a significantly higher risk of death. Short-term changes in BPRI could be influenced by lactate level, the cumulative 12-h fluid balance, and related measures. The application of BPRI and other factors influencing short-term changes in the clinical setting could help clinicians identify potentially at-risk patients and provide clues for treating the early stage of sepsis. Future research is needed to determine whether BPRI could be used as a target for intervention in patients with sepsis.

Contributors

Yujie Chen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing–Original Draft; Huizhen Jiang: Data Curation, Resources, Software, Writing–Original Draft; Yuna Wei: Data Curation, Software, Visualization, Validation, Writing–Original Draft; Yehan Qiu: Investigation, Formal Analysis; Longxiang Su: Supervision, Methodology, Writing—review & editing; Jieqing Chen: Data Curation, Software; Xin Ding: Supervision, Writing–Review & Editing; Lu Wang: Data Curation, Supervision; Dandan Ma: Resources, Supervision; Feng Zhang: Resources, Supervision; Wen Zhu: Formal Analysis, Supervision; Xiaoyang Meng: Data Curation, Project administration; Guoqiang Sun: Supervision, Project administration; Lian Ma: Resources, Project administration; Yao Wang: Software, Visualization, Validation; Linfeng Li: Software, Visualization, Validation; Guiren Ruan: Validation; Fuping Guo: Supervision; Xiang Zhou: Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing–Review & Editing; Ting Shu: Formal Analysis, Supervision, Resources, Project administration; Bin Du: Funding Acquisition, Resources, Supervision; China National Critical Care Quality Control Center Group (Group Author):Resources, Supervision.

Yujie Chen, Huizhen Jiang, Yuna Wei contributed equally, and Xiang Zhou, Ting Shu, Bin Du are the corresponding writers.

Data sharing statement

The datasets generated from Peking Union Medical College Hospital is not publicly available due to no prior agreement with the ethical committee but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The datasets generated from other sources are available in the MIMIC and the eICU repositories, https://mimic.physionet.org/, https://physionet.org/content/eicu-crd/2.0/.

Declaration of interests

All authors disclosed no potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This work was supported by the Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (L222019); the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-B-115); CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) from Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (2021-I2M-1-062) and the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFC2500801 & 2021YFC2500805).

Footnotes

The China National Critical Care Quality Control Center Group is the group author.

Monitored email of China National Critical Care Quality Control Center group: china_nccqc@163.com

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.105257.

Contributor Information

Yujie Chen, Email: herminedoc@foxmail.com.

Huizhen Jiang, Email: jianghuizhen@pumch.cn.

Yuna Wei, Email: yuna.wei@yiducloud.cn.

Yehan Qiu, Email: 18190032847@163.com.

Longxiang Su, Email: slx77@163.com.

Jieqing Chen, Email: chenjieqing@pumch.cn.

Xin Ding, Email: starrydx@163.com.

Lu Wang, Email: saibeiyin@163.com.

Dandan Ma, Email: madandan@pumch.cn.

Feng Zhang, Email: zhangfeng@pumch.cn.

Wen Zhu, Email: zhuwen@pumch.cn.

Xiaoyang Meng, Email: mengxy@pumch.cn.

Guoqiang Sun, Email: sungq@pumch.cn.

Lian Ma, Email: mal@pumch.cn.

Yao Wang, Email: yao.wang@yiducloud.cn.

Linfeng Li, Email: linfeng.li@yiducloud.cn.

Guiren Ruan, Email: ruangr@pumch.cn.

Fuping Guo, Email: pumchguofp@163.com.

Ting Shu, Email: nctingting@126.com.

Xiang Zhou, Email: zhouxiang@pumch.cn.

Bin Du, Email: dubin98@gmail.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Pudjiadi A.H., Pramesti D.L., Pardede S.O., Djer M.M., Rohsiswatmo R., Kaswandani N. Validation of the vasoactive-inotropic score in predicting pediatric septic shock mortality: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2021;11(3):117–122. doi: 10.4103/IJCIIS.IJCIIS_98_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demirhan S., Topcuoglu S., Karadag N., Ozalkaya E., Karatekin G. Vasoactive inotropic score as a predictor of mortality in neonatal septic shock. J Trop Pediatr. 2022;68(6) doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmac100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kallekkattu D., Rameshkumar R., Chidambaram M., Krishnamurthy K., Selvan T., Mahadevan S. Threshold of inotropic score and vasoactive-inotropic score for predicting mortality in pediatric septic shock. Indian J Pediatr. 2022;89(5):432–437. doi: 10.1007/s12098-021-03846-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song J., Cho H., Park D.W., et al. Vasoactive-inotropic score as an early predictor of mortality in adult patients with sepsis. J Clin Med. 2021;10(3):495. doi: 10.3390/jcm10030495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly R.P., Ting C.T., Yang T.M., et al. Effective arterial elastance as index of arterial vascular load in humans. Circulation. 1992;86(2):513–521. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.2.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monge García M.I., Guijo González P., Gracia Romero M., et al. Effects of fluid administration on arterial load in septic shock patients. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(7):1247–1255. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3898-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monge Garcia M.I., Jian Z., Settels J.J., Hatib F., Cecconi M., Pinsky M.R. Reliability of effective arterial elastance using peripheral arterial pressure as surrogate for left ventricular end-systolic pressure. J Clin Monit Comput. 2019;33(5):803–813. doi: 10.1007/s10877-018-0236-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vincent J.L., De Backer D. Circulatory shock. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(18):1726–1734. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleischmann-Struzek C., Mellhammar L., Rose N., et al. Incidence and mortality of hospital- and ICU-treated sepsis: results from an updated and expanded systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(8):1552–1562. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06151-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singer M., Deutschman C.S., Seymour C.W., et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Backer D., Hajjar L., Monnet X. Vasoconstriction in septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2024;50(3):459–462. doi: 10.1007/s00134-024-7332-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nouriel J.E., Paxton J.H. The interplay between autonomic imbalance, cardiac dysfunction, and blood pressure variability in sepsis. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(2):322–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Backer D., Creteur J., Preiser J.C., Dubois M.J., Vincent J.L. Microvascular blood flow is altered in patients with sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(1):98–104. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200109-016oc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinsky M.R. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2005. Protocolized cardiovascular management based on ventricular-arterial coupling. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinsky M.R. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2002. Functional hemodynamic monitoring: applied physiology at the bedside. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinsky M., Vincent J.L., De Smet J.M. Estimating left ventricular filling pressure during positive end-expiratory pressure in humans. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143(1):25–31. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guarracino F., Bertini P., Pinsky M.R. Cardiovascular determinants of resuscitation from sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):118. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2414-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaies M.G., Gurney J.G., Yen A.H., et al. Vasoactive-inotropic score as a predictor of morbidity and mortality in infants after cardiopulmonary bypass. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11(2):234–238. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181b806fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wynants L., Bouwmeester W., Moons K.G.M., et al. A simulation study of sample size demonstrated the importance of the n umber of events per variable to develop prediction models in clustered data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(12):1406–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeLong E.R., DeLong D.M., Clarke-Pearson D.L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(3):837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monge Garcia M.I., Guijo Gonzalez P., Saludes Orduna P., et al. Dynamic arterial elastance during experimental endotoxic septic shock: a potential marker of cardiovascular efficiency. Front Physiol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.562824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monge Garcia M.I., Pinsky M.R., Cecconi M. Predicting vasopressor needs using dynamic parameters. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(12):1841–1843. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4752-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michard F., Chemla D., Richard C., et al. Clinical use of respiratory changes in arterial pulse pressure to monitor the hemodynamic effects of PEEP. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(3):935–939. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9805077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grace M.P., Greenbaum D.M. Cardiac performance in response to PEEP in patients with cardiac dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 1982;10(6):358–360. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanz J., Sanchez-Quintana D., Bossone E., Bogaard H.J., Naeije R. Anatomy, function, and dysfunction of the right ventricle: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(12):1463–1482. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.12.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rungatscher A., Hallstrom S., Linardi D., et al. S-nitroso human serum albumin attenuates pulmonary hypertension, improves right ventricular-arterial coupling, and reduces oxidative stress in a chronic right ventricle volume overload model. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015;34(3):479–488. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans L., Rhodes A., Alhazzani W., et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(11):1181–1247. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06506-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Persichini R., Lai C., Teboul J.L., Adda I., Guerin L., Monnet X. Venous return and mean systemic filling pressure: physiology and clinical applications. Crit Care. 2022;26(1):150. doi: 10.1186/s13054-022-04024-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Persichini R., Silva S., Teboul J.L., et al. Effects of norepinephrine on mean systemic pressure and venous return in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(12):3146–3153. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318260c6c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monnet X., Lai C., Ospina-Tascon G., De Backer D. Evidence for a personalized early start of norepinephrine in septic shock. Crit Care. 2023;27(1):322. doi: 10.1186/s13054-023-04593-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Annane D., Ouanes-Besbes L., de Backer D., et al. A global perspective on vasoactive agents in shock. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(6):833–846. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeMers D., Wachs D. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Physiology, mean arterial pressure. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Daliah Wachs declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khanna A.K., Maheshwari K., Mao G., et al. Association between mean arterial pressure and acute kidney injury and a composite of myocardial injury and mortality in postoperative critically Ill patients: a retrospective cohort analysis. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(7):910–917. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shankar-Hari M., Phillips G.S., Levy M.L., et al. Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock: for the third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315(8):775–787. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J.M., Shah A.M. Endothelial cell superoxide generation: regulation and relevance for cardiovascular pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287(5):R1014–R1030. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00124.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cepinskas G., Wilson J.X. Inflammatory response in microvascular endothelium in sepsis: role of oxidants. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2008;42(3):175–184. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.2008026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou M., Wang P., Chaudry I.H. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase is downregulated during hyperdynamic sepsis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1335(1-2):182–190. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(96)00139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siddall E., Khatri M., Radhakrishnan J. Capillary leak syndrome: etiologies, pathophysiology, and management. Kidney Int. 2017;92(1):37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou X., Liu D., Su L., et al. Use of stepwise lactate kinetics-oriented hemodynamic therapy could improve the clinical outcomes of patients with sepsis-associated hyperlactatemia. Crit Care. 2017;21(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1617-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levy M.M., Dellinger R.P., Townsend S.R., et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: results of an international guideline-based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(2):222–231. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1738-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Acheampong A., Vincent J.L. A positive fluid balance is an independent prognostic factor in patients with sepsis. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):251. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0970-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sirvent J.M., Ferri C., Baro A., Murcia C., Lorencio C. Fluid balance in sepsis and septic shock as a determining factor of mortality. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(2):186–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hjortrup P.B., Haase N., Bundgaard H., et al. Restricting volumes of resuscitation fluid in adults with septic shock after initial management: the CLASSIC randomised, parallel-group, multicentre feasibility trial. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(11):1695–1705. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4500-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meyhoff T.S., Moller M.H., Hjortrup P.B., Cronhjort M., Perner A., Wetterslev J. Lower vs higher fluid volumes during initial management of sepsis: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Chest. 2020;157(6):1478–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sivapalan P., Ellekjaer K.L., Jessen M.K., et al. Lower vs higher fluid volumes in adult patients with sepsis: an updated systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Chest. 2023;164(4):892–912. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2023.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferryman K., Drazen J.M., Mackintosh M., Ghassemi M. Considering biased data as informative artifacts in AI-assisted Health care. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(9):833–838. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2214964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.