Summary

Background

Intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) serve as robust barriers against potentially hostile luminal antigens and commensal microbiota. Epithelial barrier dysfunction enhances intestinal permeability, leading to leaky gut syndrome (LGS) associated with autoimmune and chronic inflammatory disorders. However, a causal relationship between LGS and systemic disorders remains unclear. Ap1m2 encodes clathrin adaptor protein complex 1 subunit mu 2, which facilitates polarized protein trafficking toward the basolateral membrane and contributes to the establishment of epithelial barrier functions.

Methods

We generated IEC-specific Ap1m2-deficient (Ap1m2ΔIEC) mice with low intestinal barrier integrity as an LSG model and examined the systemic impact.

Findings

Ap1m2ΔIEC mice spontaneously developed IgA nephropathy (IgAN)-like features characterized by the deposition of IgA–IgG immune complexes and complement factors in the kidney glomeruli. Ap1m2 deficiency markedly enhanced aberrantly glycosylated IgA in the serum owing to downregulation and mis-sorting of polymeric immunoglobulin receptors in IECs. Furthermore, Ap1m2 deficiency caused intestinal dysbiosis by attenuating IL-22-STAT3 signaling. Intestinal dysbiosis contributed to the pathogenesis of IgAN because antibiotic treatment reduced aberrantly glycosylated IgA production and renal IgA deposition in Ap1m2ΔIEC mice.

Interpretation

IEC barrier dysfunction and subsequent dysbiosis by AP-1B deficiency provoke IgA deposition in the mouse kidney. Our findings provide experimental evidence of a pathological link between LGS and IgAN.

Funding

AMED, AMED-CREST, JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research, JST CREST, Fuji Foundation for Protein Research, and Keio University Program for the Advancement of Next Generation Research Projects.

Keywords: IgA nephropathy, Epithelial barrier, Leaky gut syndrome, Intestinal microbiota, Ap1m2

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Epithelial barrier dysfunction enhances intestinal permeability, leading to leaky gut syndrome (LGS). Recent cohort studies and a GWAS have shown an association between the risk of IgA nephropathy and intestinal dysfunctions. These reports suggest that intestinal dysfunction may cause the development of IgA nephropathy (IgAN). However, experimental evidence is still lacking, limiting development to therapeutic targets at the cellular or molecular level.

Added value of this study

Here, we generated Villin-Cre-ERT2 Ap1m2fl/fl mice, tamoxifen-inducible and intestinal epithelial cell-specific Ap1m2-deficient (Ap1m2ΔIEC) mice, as an LGS model and examined the systemic impact. Ap1m2ΔIEC mice spontaneously developed IgAN-like features characterized by the deposition of IgA-IgG immune complexes and complement factors in the kidney glomeruli. Ap1m2 deficiency markedly enhanced aberrantly glycosylated IgA and IgA-IgG complex in the serum. This was due to downregulation and mis-sorting polymeric immunoglobulin receptors in intestinal epithelial cells. IgA produced in the isolated intestine of Ap1m2ΔIEC mice caused IgA deposition in the kidney of control mice. Furthermore, Ap1m2 deficiency caused decreased antimicrobial peptide production due to reduced IL-22-STAT3 signaling, resulting in dysbiosis of the gut microbiota. Intestinal dysbiosis contributed to the pathogenesis of IgAN because depletion of the microbiota reduced aberrantly glycosylated IgA production and renal IgA deposition in Ap1m2ΔIEC mice.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our study provides experimental evidence of a causal relationship between IgAN and intestinal barrier disruption by using Ap1m2ΔIEC mice as a new LGS model. This model supports the hypothesis that the gut–kidney axis plays a vital role in the pathogenesis of IgAN. Furthermore, this experimental model may be applied to develop and improve promising treatments for IgAN.

Introduction

The intestinal mucosa is constitutively exposed to numerous foodborne antigens, pathogens, and commensal microbes. To prevent the infiltration of exogenous antigens into the bloodstream, intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) establish robust physical and immune barriers, including tight junctions, mucin, and antimicrobial peptides.1, 2, 3 IECs are responsible for luminal secretion of dimeric or polymeric IgA via polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR)-dependent transcytosis.4 Secretory IgA contributes significantly to the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis by regulating the microbial community and constraining the penetration of microbial metabolites into the bloodstream of the host.5,6

Asymmetric protein distribution via proper protein sorting is essential for cell polarity formation and is vital for barrier functions. Clathrin adaptor protein (AP)-1B complexes localize in the trans-Golgi network and recycling endosomes regulate basolateral sorting in polarized epithelial cells.7 AP-1B complexes are composed of four subunits—γ, β1, σ1, and μ1B. Among them, μ1B recognizes tyrosine-based motifs in the cytosolic region of membrane proteins to facilitate their polarized sorting into the basolateral membrane.8,9 We previously reported that mice carrying a systemic deletion of Ap1m2, the gene encoding μ1B subunit, spontaneously develop IL-17-mediated colitis accompanied by intestinal dysbiosis.10 This abnormality is mainly attributed to diminished production of antimicrobial products due to mis-sorting of otherwise basolaterally localized cytokine receptors, such as IL-6st and IL-17RA.10 Additionally, mislocalization of E-cadherin caused by Ap1m2 deficiency leads to hyperplasia of the upper intestinal epithelium due to hyperactivation of β-catenin signaling.11 Therefore, AP-1B complex is essential for maintaining epithelial integrity and barrier function.

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is the most common glomerulonephritis, characterized by glomerular deposition of IgA, which induces inflammation and progression to renal injury.12 Patients present with hematuria/proteinuria and approximately 40% develop end-stage renal disease within 30 years. Several lines of experimental evidence suggest that the onset of IgAN may arise from the presence of galactose-deficient IgA.13, 14, 15 The aberrantly glycosylated IgA is recognized by anti-glycan antibodies, and the immune complex causes renal deposition and the subsequent complement activation, leading to tissue damage.16, 17, 18

Given the detection of J chain-containing polymeric IgA in the kidneys of patients with IgAN,19 mucosal IgA production may play a role in disease onset. The intestinal tract is the largest mucosal tissue for IgA production. Recent GWAS have shown an association between the risk of IgAN with intestinal inflammation and the gut immune system.20,21 However, the experimental evidence is insufficient to establish a causal relationship between intestinal immunity and IgAN development.

Disruption of the barrier function alters the microbial composition of the intestine and leads to dysbiosis.22,23 Intestinal dysbiosis further increases intestinal permeability, facilitating systemic inflammation due to leakage of intraluminal substances into the bloodstream. This pathological condition is often referred to as “leaky gut syndrome (LGS)".24,25 Accumulating evidence suggests a potential association between LGS with various diseases, not only in the intestine (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease and celiac disease), but also in the extraintestinal tissue (e.g., allergic diseases, obesity, and autoimmune diseases).26 However, it remains to be determined whether LGS is the cause or result of these diseases. The lack of animal models of LGS has hampered the elucidation of this issue.

In this study, we aimed to clarify the relationship between LGS and systemic disorders. To this end, we established IEC-specific AP-1B-deficient (Ap1m2ΔIEC) mice as a model for LGS and found that these mice spontaneously develop IgAN-like features, including IgA deposition in the kidney glomeruli with signs of abnormal renal function. Our analysis revealed that AP-1B deficiency impaired several IEC functions, including pIgR-dependent IgA transcytosis and IL-22-STAT3 signaling. These IEC dysfunctions may cause defects in the secretion of IgA and production of antimicrobial peptides, which may contribute to dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota. Furthermore, IgA from the AP-1B-deficient intestine was deposited in the kidney glomeruli of wild-type mice, and depletion of microbiota by antibiotic treatment reduced the IgA deposition in AP-1B-deficient mice. These results underscore the importance of IEC dysfunction and resulting dysbiosis in the pathogenesis of IgAN.

Methods

Animals

All the mouse strains were housed in a group of around 5 mice per cage in a 12-h light/dark cycle and provided food and water ad libitum at Keio University Faculty of Pharmacy Animal Facility. In the Ussing chamber experiment, animals were transported to the University of Shizuoka from Keio University and maintained under the same conditions until the dissection.

We have generated Ap1m2fl/fl mice as described previously.11 We crossed Ap1m2fl/fl mice with Villin-Cre-ERT2 transgenic mice (kindly provided from Sylvie Robine27). Villin-Cre-ERT2 Ap1m2fl/fl mice and Ap1m2fl/fl mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. One week before tamoxifen administration, they were transferred to conventional conditions and grouped by genotype by experimenters. C57BL/6JJcl (RRID:IMSR_JCL:JCL:MIN-0003) mice were purchased from CLEA (Tokyo, Japan) and maintained under conventional conditions. All experiments, except those in Supplementary Figure S2, were performed using female mice.

All animal experimental protocols were prepared before the start. All mice prepared in each experiment were analyzed, and we did not establish any humane endpoints and criteria related to inclusion or exclusion. We did not employ any specific strategies to control for confounders.

Induction of Ap1m2 gene deletion by tamoxifen administration

To induce Ap1m2 gene deletion in intestinal epithelial cells, eight to ten weeks-old Villin-Cre-ERT2 Ap1m2fl/fl mice were orally administrated 1 mg tamoxifen (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) diluted in sunflower seed oil (Sigma Aldrich) three times every five days. Age- and sex-matched littermate Ap1m2fl/fl mice were administered tamoxifen in the same manner and served as the experimental control group. Tamoxifen-treated mice were used for experiments on days 15 and 20 after the initial administration.

Antibiotic treatment

For antibiotic treatment, antibiotics were prepared as a cocktail of 1 g/L ampicillin, 1 g/L neomycin (both from Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan), 1 g/L metronidazole, and 0.5 g/L vancomycin (both from FUJIFILM Wako, Tokyo, Japan) in water. To acclimatize the antibiotics treatment, the mice were administered the antibiotic cocktail orally once a day for the first week. The antibiotic administration was started two weeks before tamoxifen treatment to help the mice recover from the initial body weight loss caused by the antibiotic treatment. The antibiotic cocktail was given to mice ad libitum as drinking water until the day of dissection.

Biochemical test

Blood was drawn from the heart of deeply anesthetized mice, allowed to incubate at 20–25 °C for 0.5–1 h, and then serum was collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 25 °C. Each mouse was placed in an empty cage for urine collection, allowed to urinate freely, and urine was immediately collected from the cage. These samples were stored at −80 °C until use. Serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, urine total protein, urine albumin, and urine creatinine levels were analyzed by Oriental Yeast (Tokyo, Japan).

Histochemistry

The terminal portion of ileum and the central portion of the colon were sampled, and then fixed with zinc-formalin (Polysciences, Marlborough, MA) for 1 h. After fixation, the tissue was dehydrated by stepwise increases in the ethanol concentration from 70% to 100%, replacing it with xylene, and then embedding it in paraffin. The paraffinized-tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene and hydrated. For hematoxylin-eosin staining, the sections were soaked in Mayer's Hematoxylin Solution (FUJIFILM Wako), followed by rinsing with water. Then, they were soaked in EosinY (FUJIFILM Wako)-Phloxine B (FUJIFILM Wako) solution. For alcian-blue staining, the sections were soaked in 3% acetate and then in Alcian Blue Solution (FUJIFILM Wako). After washing 3% acetate and water, the sections were stained with Nuclear Fast Red (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). After dehydration and clearing, the sections were mounted with Mount-Quick (Daido Sangyo, Tokyo, Japan). The specimens were observed using System Microscope BX53 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

FITC-dextran test

Mice were orally gavaged with 4 or 70 kDa FITC-dextran (Sigma–Aldrich) (60 mg/100 g body weight) after 4 h of fasting, and blood was collected 45 min later. The concentration of FITC-dextran was determined using an Infinite M1000 instrument (TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland) with an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 528 nm. Diluted FITC-dextran from the serum of wild-type mice was used as a standard.

Organ culture

Circular fragments were sectioned with 3 mm diameter biopsy punches from isolated ileum, which were placed into a 24-well culture plate and were cultured for 6 h with RPMI 1640 medium (Nacalai Tesque) containing 100 U/mL Penicillin and Streptomycin Mixed Solution (Nacalai Tesque), 12.5 mM HEPES (Nacalai Tesque), 2-ME (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), and GultaMax (Gibco) (1:100) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Culture supernatants were collected and used for ELISA and mouse treatment. To examine whether intestine-derived IgA has renal deposition properties, diluted supernatants containing 200 ng of IgA were injected into wild-type mice. Two hours later, the kidneys were sampled after perfusion with PBS (Nacalai Tesque) and used for immunofluorescence staining.

Transepithelial electrical resistance using ussing chamber

To obtain intestinal tissues, the animals were anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation and sacrificed by cervical dislocation immediately before the experiments. Tissue preparation and the methods of measurements of Isc and TEER were performed as previously described.28

Terminal ileum and middle colon were isolated from the Ap1m2fl/fl and Ap1m2ΔIEC mice, and the tissues were immediately immersed in ice-cold Krebs–Ringer solution (117 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, and 2.5 CaCl2 in mmol/L saturated with 95% O2–5% CO2). The tissues were cut along the mesenteric border and the contents were gently removed using Ringer's solution. Flat sheets of the tissues were pinned with the mucosal side down to silicon rubber-lined Petri dishes filled with the Krebs–Ringer solution. The serosa and smooth muscle layers of the tissue were removed in cold Krebs–Ringer solution using spring microscissors and precision tweezers under a stereomicroscope. The mucosa-submucosa preparations were mounted between sliders (P2404; Recording area 0.25 cm2; Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA), and inserted between halves of the Ussing chambers (P2400, Physiologic Instruments). One milliliter Krebs–Ringer solutions with and without 5 mM glucose were perfused with submucosal and mucosal chambers, respectively, and both side solutions were maintained at 37 °C and bubbled with 95% O2–5% CO2.

A pair of Ag/AgCl electrodes for measuring membrane potential differences and another pair of Ag/AgCl electrodes for applying a current (Isc) to clamp potential difference to 0 mV were placed via Krebs-2% Ager bridges to each side of the Ussing chambers and connected to a voltage-clamp apparatus (CEZ-9100; Miyuki Giken, Tokyo, Japan). To measure the TEER, the clamp voltage was changed from 0 to 10 mV only for 3 s at 1-min intervals. The outputs of the applied current values (Isc when 0 mV clamp) from the voltage-clamp apparatus were recorded using an A/D conversion and data acquisition system (PowerLab; AD Instruments Japan, Nagoya, Japan). Using a chart-recorder software, LabChart (ADInstruments Japan), TEER values were calculated in real-time by Ohm's law from the applying current change necessary (ΔI10mV) to change the clamp voltage as follows: TEER (mΩcm2) = 10 (mV)/ΔI10mV (μA/cm2). Isc and TEER values after 1 h of stabilization from tissue mounting were determined as the basal electrophysiological parameters of the intestinal epithelial tissue preparations.

Mouse small intestinal organoid culture

Small intestinal organoids were generated from the ileum of Ap1m2fl/fl and Villin-Cre-ERT2 Ap1m2fl/fl mice following previously established protocol.29 The ileum was collected, and its villus was removed using a cover glass. The tissue was sectioned into 5 mm segments and washed in ice-cold 2 mM EDTA (Nacalai Tesque) in PBS by vigorously pipetting. After removal of the supernatant, the segments were resuspended in ice-cold 2 mM EDTA in PBS and incubated for 30 min. Crypts were subsequently isolated by vigorously pipetting in HBSS (−) without Ca, Mg, with Phenol Red (Nacalai Tesque). After the centrifugation, the isolated crypts were then resuspended in Advanced DMEM/F12 (Gibco) containing 100 U/ml Penicillin and Streptomycin Mixed Solution and Glutamax (1:100). They were passed through a 70 μm cell strainer (Corning, Corning, NY) to remove the remained villus and centrifuged at 70 × g for 3 min to separate crypts from single cells. The resulting pellet containing the crypts was resuspended in Matrigel (Corning) and plated in a 48-well plate using IntestiCult Organoid Growth Medium (Mouse) (Stemcell Technologies, Cologne, Germany), and then incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

To induce Cre-ERT2 recombinase activation, the organoids were treated with 1 μM 4-hydroxytamoxyfen (Selleckchem, Houston, TX) one day after the seeding and incubated for 24 h. After five days, 10 ng/ml recombinant mouse IL-17A (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was added to the culture medium. Organoids were collected in TRIzol LS reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) after 24 h from the addition of IL-17 to purify total RNA for quantitative PCR.

Quantitative PCR

Epithelial monolayers were isolated by modifying a previously described method.30 Briefly, 1 cm sections of ileal tissues were soaked in ice-cold 30 mM EDTA solution in Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) (Gibco) for 5–10 min. The epithelial monolayers were peeled off by manipulation with a fine needle under stereomicroscopic monitoring. Total RNA was purified using the TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the ReverTra Ace (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). Quantitative PCR was performed with a CFX Connect real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) using SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The primers used for these assays are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Size fractionation of serum protein

Pooled sera in each group were diluted in PBS and were fractionated by size exclusion chromatography using a Superose 6 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare Life Science, Wauwatosa, WI). High-molecular-weight gel filtration calibration kits (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) were used to calibrate the column. The fractions were subjected to ELISA to detect IgA and western blotting to detect secretory components.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

For detection of IgA, 96-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were coated with 100 μl anti-mouse IgA antibody (1:100, Cat. No. A90-103A, Betyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX, RRID:AB_67136) in 50 mM sodium carbonate for 1 h at 20–25 °C. To detect the IgA-IgG immune complex, 96-well plates were coated with an anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:100, Cat. No. A90-131A; Betyl Laboratories, RRID:AB_67172) in the same manner. After washing three times with Tris Buffered Saline containing 0.05% Tween 20, the plates were blocked with 200 μl 2% BSA/PBS. The plates were incubated with 100 μl sera diluted in 2% BSA/PBS or luminal content suspended in cOmplete™ EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) solution for 1 h at 20–25 °C. IgA or IgA-IgG complex captured on the plate was labeled with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgA antibody (1:50,000–100,000, Cat. No. A90-103P, Betyl Laboratories, RRID:AB_67140) diluted in 2% BSA/PBS for 1 h at 20–25 °C. After washing, HRP enzyme activity on the plate was detected by 5–10 min incubation with 3,3′, 5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or ELISA POD Substrate TMB Kit (Popular) (Nacalai Tesque). After stopping the HRP enzyme–substrate reaction by adding 100 μl 1.2 M sulfuric acid to the plate, HRP activity was measured as absorbance at 450 nm with an Infinite 200Pro plate reader (TECAN). Absorbance at 570 nm was used as a reference.

Lectin binding assay

The lectin binding assay was performed as previously described.31 The serum used for the lectin binding assay was formerly measured for IgA concentration by ELISA and diluted with PBS so that the IgA concentration was 1 μg/ml. IgA-coated 96 well plates prepared as above were incubated with 100 μl of the diluted sera for 1 h at 20–25 °C. After washing with Tris Buffered Saline including 0.05% Tween 20, the plates were incubated with 100 μl biotinylated RCA (1:1,000, B-1085-5, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) or biotinylated SNA (1:400, B-1305-2, Vector Laboratories) for 1 h at 20–25 °C. Subsequently, the plates were incubated with 100 μl HRP-conjugated streptavidin (1:10,000, Cat. No. 3999, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) for 1 h at 20–25 °C. The HRP enzyme–substrate reaction and absorbance measurements were performed as described in the section of Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Western blotting

The isolated epithelium was lysed in 1× RIPA Buffer with 1% SDS (10×) (Nacalai Tesque) containing 1 mM NaF (Nacalai Tesque) for 30 min on ice and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was diluted in a 2× Sample Buffer Solution with 2-ME for SDS-PAGE (Nacalai Tesque). The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to an Immobilon-P membrane (Merck, Kenilworth, NJ). After blocking with PVDF Blocking Reagent (TOYOBO), the membranes were incubated with anti-phospho-STAT3 antibody (1:2000; clone D3A7, Cell Signaling Technology, RRID:AB_2491009) and following HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:2000; Cat. No. 7074, Cell Signaling Technology, RRID:AB_2099233) in Can Get Signal Immunoreaction Enhancer Solution (TOYOBO). Chemiluminescence and bright-field images of the protein-blotted membranes were acquired using the Chemi-Lumi One series (Nacalai Tesque) and Amersham ImageQuant800 (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA). After that, the membranes were stripped with a WB Stripping Solution (Nacalai Tesque) for 15 min at 20–25 °C and were reacted with anti-STAT3 (1:1000; clone D3Z2G, Cell Signaling Technology, RRID:AB_2629499) and anti-β-actin (1:2000; clone 6D1, FUJIFILM Wako, RRID:AB_2858279) antibodies and following HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG or mouse IgG antibody (1:2000; Cat. No. 7076, Cell Signaling Technology, RRID:AB_330924). The image was acquired the same method. The band intensity was measured by densitometry with Fiji32 (RRID:SCR_002285).

Immunofluorescence staining

For most kidney staining, the mice were perfused with PBS under deep anesthesia, and the kidneys were extracted and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA)/PBS overnight. After substituting 30% sucrose (Nacalai Tesque), the tissues were immersed in OCT compound and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. For the antibiotic treatment experiment, dissected fresh kidneys were fixed with 4% PFA/PBS overnight. After fixation, the tissue was dehydrated by stepwise increases in the ethanol concentration from 70% to 100%, replacing it with xylene, and then embedding it in paraffin.

To stain the ileum with anti-pIgR antibody, the extracted ileum was fixed in 4% PFA/PBS for 1 h. After substituting 30% sucrose, the tissues were immersed in OCT compound and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. For ZO-1 and E-cadherin staining, the dissected ileum was directly immersed in OCT compound, napped, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Fresh frozen tissue was cut into 10-μm thin sections, air-dried, and fixed in 4% PFA/PBS for 1 h. For RegIIIγ staining, the ileum tissues were fixed with zinc-formalin for 1 h and then embedded in paraffin.

In the case of paraffin-embedded tissues, after deparaffinization with xylene, the xylene was removed by lowering the ethanol concentration stepwise from 100% to 70% and finally replaced with PBS. For frozen tissue sections, PBS was used to remove OCT compounds. After pretreatment with 0.3% Triton X-100 (Nacalai Tesque) in PBS and pre-incubation with 10% normal donkey serum (Sigma–Aldrich) in PBS, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies at 20–25 °C overnight. After washing, the sections were incubated with secondary antibodies at 20–25 °C for 2–3 h. The specimens were observed using a confocal laser microscope FV3000 (Olympus) after mounting with ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The primary antibodies were as followed: rabbit anti-C3 (1:200, Cat. No. A006302, DAKO, Carpinteria, CA, RRID:AB_578478), rat anti-mouse CD107a (LAMP-1) (1:200, clone 1D4B, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, RRID:AB_572020), goat anti-mouse IgA (1:200, Cat. No. A90-103A; Betyl Laboratories, RRID:AB_67136), rat anti-mouse IgA (1:200, clone RMA-1, BioLegend, RRID:AB_315076), Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:400; Cat. No. 715-545-150, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, RRID:AB_2340846), goat anti-mouse pIgR antibody (1:200, Cat. No. AF2800, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, RRID:AB_2283871), and rabbit anti-RegIIIγ (1:200, Cat. No. ab198216, Abcam, RRID:AB_2892581). For the quantification of the deposition area of IgA, IgG, and C3 in the kidney, the stained areas with fluorescence intensity above a certain level and the glomerular area were measured using Fiji.

Electron microscopy

The detailed procedure has been previously described.33 Briefly, for transmission electron microscopy (TEM), kidney specimens were primarily fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (TAAB Laboratories, England, UK) for 12–24 h at 4 °C. Samples were washed in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.4, Muto Pure Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan), secondary fixed with 1.0% osmium tetroxide (FUJIFILM Wako) for 2 h at 4 °C. Samples were dehydrated from a series of increasing concentrations of ethanol (twice at 50, 70, 80, 90, 100% EtOH for 20 min each), soaked with acetone (Sigma–Aldrich) with n-butyl glycidyl ether (QY1, Okenshoji, Tokyo, Japan), graded concentration of epoxy resin with QY-1, and 100% epoxy resin (100 g Epon was composed of 27.0 g MNA, 51.3 g EPOK-812, 21.9 g DDSA and 1.1 ml DMP-30, all from Okenshoji) for 48 h at 4 °C; these were polymerized with pure epoxy resin for 72 h at 60 °C. Resin blocks with organoids were trimmed, semi-thin-sectioned at 350 nm for toluidine blue staining, and ultra-thin-sectioned at 80 nm using an ultramicrotome (UC7; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Ultrathin sections were collected on copper grids and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. The sections were imaged using a TEM (JEM-1400 Plus, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at 100 keV.

For pre-embedding immuno-electron microscopy analysis, the frozen sections of the gut wall on the slide glasses were dried up with a cool wind dryer, washed in 0.1 M PB three times, followed by incubation with the blocking solution containing 5.0% Block Ace (DS Pharma Biomedical, Osaka, Japan) with 0.01% saponin in 0.1 M PB for 1 h at 25 °C. Sections were incubated with goat anti-mouse pIgR antibody (1:100, Cat. No. AF2800, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, RRID:AB_2283871) in blocking solution for 72 h at 4 °C, followed by the incubation with Hoechst 33,258 (1:1000, Sigma–Aldrich) and Alexa Fluor 488 FluoroNanogold conjugated rabbit anti-goat secondary antibody (1:100, Nanoprobes, Yaphank, NY) for 24 h at 4 °C. The specific area of interest was identified using fluorescence microscopy (Axio Imager M1, Carl Zeiss, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany) as an Alexa Fluor 488 positive area. After 2.5% glutaraldehyde fixation in 0.1 M PB for 1 h, washed in 0.1 M PB and 50 mM HEPES (pH 5.8) three times for 10 min, and washed with diluted water for 1 min, nanogold signals were enhanced with silver enhancement solution for 2.5 min at 25 °C. Gold labeled sections were post-fixed with 1.0% osmium tetroxide for 1.5 h at 4 °C, en bloc stained with uranyl acetate for 20 min at 25 °C, and dehydrated through diluted ethanol (twice at 50, 70, 80, 90, 100% EtOH for 5 min each), with 100% acetone (Sigma–Aldrich) for 5 min, two times with QY1 for 5 min, epoxy resin with QY1 (1:1) for 1 h, 100% epoxy resin for 48 h at 4 °C and embedded into 100% epoxy resin. After polymerization for 72 h at 60 °C, resin blocks were trimmed and were ultrathin-sectioned at 80 nm thickness with ultramicrotome. Ultrathin sections were collected on copper grids, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and imaged by TEM (JEM-1400 plus, JEOL) at 100 keV.

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observation, gut samples were primary fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 12–24 h at 4 °C, washed in 0.1 M PB, and secondary fixed with 1.0% osmium tetroxide for 2 h at 4 °C. Samples were dehydrated using a series of increasing ethanol concentrations and dried with a critical point dryer (CPD300, Leica Biosystems). The samples were placed on an aluminum scanning stage, coated with Pt–Pd using a conductive quick coater at a current of 5 mA for 30 s three times (sc-701, SANYU ELECTRON, Tokyo, Japan), and imaged with SEM (SU6600, Hitachi High Tech, Tokyo, Japan) at 5 kV.

Preparation of immune cells

Leukocytes from the ileal lamina propria were prepared as previously described with some modifications.32 After removal of Peyer's patches and vortex washed, ileal tissues were treated with 20 mM EDTA in HBSS (−) without Ca, Mg, with Phenol Red containing 1 mM dithiothreitol (Nacalai Tesque), 100 U/mL Penicillin and Streptomycin Mixed Solution, and 12.5 mM HEPES at 37 °C for 20 min. After vortexing, the tissues were minced using scissors. Subsequently, they were enzymatically dissociated at 37 °C for 30 min, with gently mixing, using 0.2 U/mL of Liberase (Roche) and 0.125 mg/ml of DNase I (Sigma Aldrich) in RPMI 1640 medium containing 2% newborn calf serum, 100 U/mL of Penicillin and Streptomycin Mixed Solution, and 12.5 mM of HEPES. The leukocytes were concentrated using a 40/80% Percoll gradient (Cytiva).

To isolate leukocytes from the Peyer's patches and mesenteric lymph nodes, the tissues were mechanically disrupted into single-cell suspensions through 100 μm nylon mesh cell strainers (Greiner Bio-One, Kremsmünster, Austria).

Flow cytometry

For cell-surface staining, cells were incubated with TruStain FcX™ PLUS (anti-mouse CD16/32) antibody (clone S17011E, BioLegend, RRID:AB_2783138) in 2% NBCS/PBS to block Fc receptors before surface antigen staining. Cells isolated from the ileal lamina propria were reacted with antibodies to BV650-conjugated anti-mouse CD45 (clone 30-F11, BioLegend, RRID:AB_2565884), BV510-conjugated anti-mouse B220/CD45R (clone RA3-6B2, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, RRID:AB_2738007), BV421-conjugated anti-mouse CD3ε (clone 145-2C11, BioLegend, RRID:AB_2562556), and FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgA (clone C10-3, BD Biosciences, RRID:AB_397235), followed by dead cell staining with 7-AAD Viability Staining Solution (BioLegend). Cells isolated from Peyer's patches and mesenteric lymph nodes were stained with antibodies to BV786-conjugated anti-mouse CD19 (clone 1D3, BD Biosciences, RRID:AB_2738141), BV650-conjugated anti-mouse CD25 (clone PC61, BD Biosciences, RRID:AB_2738547), BV605-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 (clone RM4-5, BD Biosciences, RRID:AB_2687549), BV510-conjugated anti-mouse CD45 (clone 30-F11, BioLegend, RRID:AB_2563061), Pacific Blue-conjugated anti-mouse/human GL7 antigen (clone GL7, BioLegend, RRID:AB_2563292), PerCP-eFluor 710-conjugated anti-CD279 (PD-1) (clone J43, Thermo Fisher Science, RRID:AB_11150055), FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgA (clone C10-3, BD Biosciences, RRID:AB_397235), R718-conjugated anti-mouse CD95 (Fas) (clone Jo2, BD Biosciences, RRID:AB_2917330), and APC-conjugated anti-mouse CD185 (CXCR5) (clone L138D7, BioLegend, RRID:AB_2561970), followed by dead cell staining with Fixable Viability Stain 780 (BD Biosciences). The cells were fixed, permeabilized using a Transcription Factor Buffer Set (BD Biosciences) and stained with PE-conjugated anti-FOXP3 (clone FJK-16s, Thermo Fisher Science, RRID:AB_465936) and PE-CF594-conjugated anti-mouse Bcl-6 (clone K112-91, BD Biosciences, RRID:AB_11152084) antibodies. Flow cytometry was performed using a FACSCelesta flow cytometer with BD FACS Diva software version 8.0 (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed using FlowJo version 10.7 (FlowJo, Ashland, OR, RRID:SCR_008520).

B cells isolation

After the preparation of single cells from the ileal lamina propria, B cells were isolated using the MojoSort Mouse Pan B Cell Isolation Kit II (BioLegend) according to the manufacturer's instructions and used for quantitative PCR.

16S rRNA gene sequencing

A library of 16S rRNA genes was constructed as previously described with some modifications.34 Genomic DNA was extracted from the luminal contents of the ileum using a QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Each DNA sample was amplified by PCR using KAPA HiFi HS ReadyMix (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA) and primers specific for the variable regions three and four of the 16S rRNA gene. The amplicons were purified using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) and attached to dual indices by index PCR using a Nextera XT Index kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA). After purification using AMPure XP beads, libraries were diluted to 4 nM with 10 nM Tris–HCl buffer. The libraries were normalized, pooled, and sequenced on a MiSeq system (Illumina) with 300 bp paired-end reads.

Data analysis was performed as described previously with some modifications.34 Briefly, FASTQ files were analyzed using the QIIME2 pipeline (QIIME2 version 2022.2) and SILVA database (version 138). The quality score was checked using a demux-summarize, and denoising was performed using denoise-paired DADA2. The phylogenetic tree for diversity analysis was reconstructed using the QIIME2 align-to-tree-mafft-fast tree. Diversity analysis was performed using QIIME2 core-metric phylogenetic analysis. The relative abundance of each taxon was calculated using the taxa collapse QIIME2 plugin.

Antibody characterization

All antibody used in this study were obtained from commercial suppliers and have been validated for the specificity in ELISA, western blotting, immunostaining, and flow cytometry applications by the manufacturers.

Ethics

Animal experiments were performed using protocols approved by the Animal Studies Committee of Keio University (No. A2022-201), the University of Shizuoka Animal Usage Ethics Committee (No. 215328), and the University of Shizuoka Genetic Recombination Experiment Safety Committee (No. 782–2203).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.2.0 (GraphPad Software, RRID:SCR_002798). Differences between the two groups were analyzed using an unpaired two-tailed Mann–Whitney test. In the organoid experiment and the antibiotic treatment experiment, the differences were analyzed using two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. Feature taxa were identified using Linear Discrimination Analysis Effect Size.35

Role of funders

The funding source did not have any role in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

Generation of tamoxifen-inducible transgenic mice deficient in AP-1B in the intestinal epithelial cells

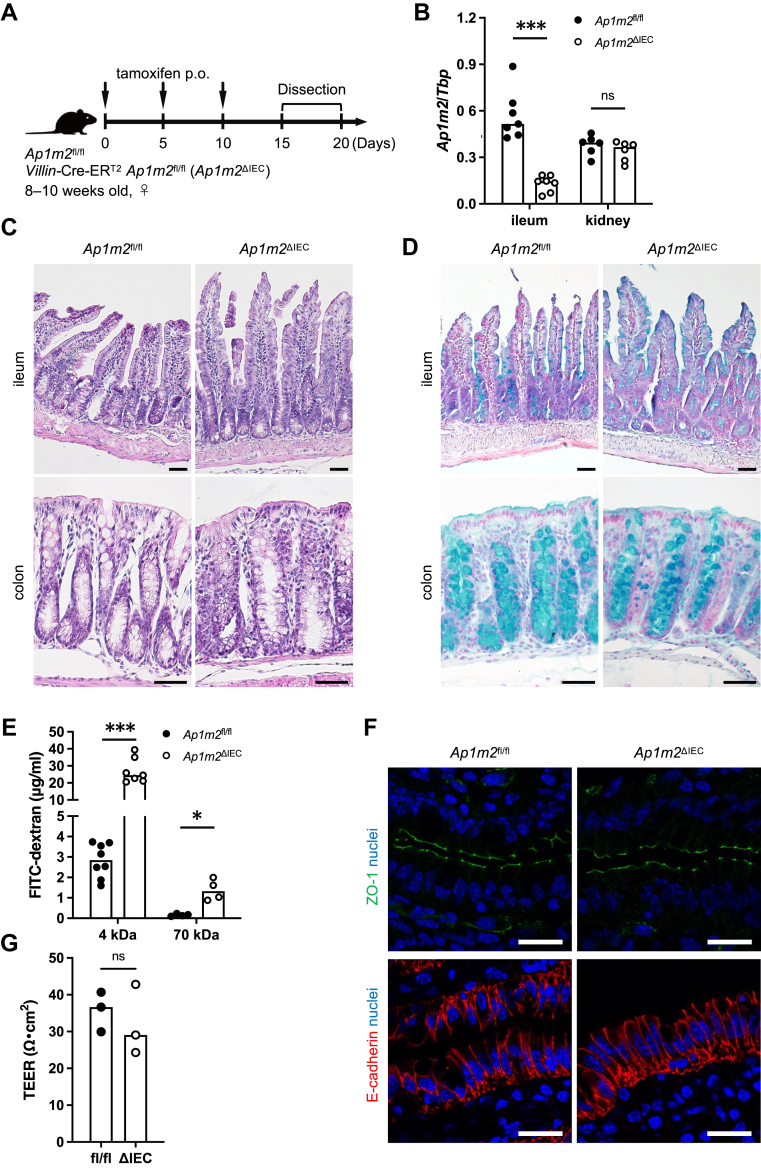

To induce Ap1m2 deletion in the intestinal epithelial cells (IECs), we generated Villin-Cre-ERT2 Ap1m2fl/fl mice and orally administered tamoxifen three times every five days (Fig. 1A). The expression of Ap1m2 decreased to approximately 20% in the ileum of Villin-Cre-ERT2 Ap1m2fl/fl mice after tamoxifen administration compared to Ap1m2fl/fl mice under the same conditions (Fig. 1B). Villin is an actin-binding protein that is localized at the brush borders of the columnar epithelium of the intestine and kidney. Considering that Ap1m2 is expressed by the polarized epithelium, including the renal epithelium, Villin-Cre-ERT2 expression might affect renal Ap1m2 expression. However, the expression level of Ap1m2 was comparable in the kidneys of Ap1m2fl/fl and Villin-Cre-ERT2 Ap1m2fl/fl mice (Fig. 1B). Hereafter, we term Villin-Cre-ERT2 Ap1m2fl/fl mice as Ap1m2ΔIEC mice. The tamoxifen-treated Ap1m2fl/fl mice were used as controls and are simply referred to as Ap1m2fl/fl mice.

Fig. 1.

The absence of AP-1B increases the intestinal permeability of dextran. (A) Experimental schedule of tamoxifen administration to Ap1m2fl/fl and Ap1m2ΔIEC mice for induction of Ap1m2 deficiency in the intestinal epithelial cells. Mice were orally administered 100 μl of 10 mg/ml tamoxifen diluted in sunflower seed oil every five days. Mice were used for the following experiments between days 15 and 20 after the initial administration. (B) Quantitative PCR analysis of Ap1m2 expression in the intestine and kidney from Ap1m2fl/fl and Ap1m2ΔIEC female mice after tamoxifen administration. Tbp was analyzed as a reference gene. n = 7 (ileum) or 6 (kidney). (C) and (D) Representative histological sections of (C) hematoxylin and eosin or (D) Alcian Blue-stained ileal and colonic tissues from Ap1m2fl/fl and Ap1m2ΔIEC female mice. Scale bars: 50 μm. (E) Intestinal permeability was assessed by the serum concentration of 4 kDa (n = 8 or 7) or 70 kDa (n = 4) FITC-dextran. (F) Immunofluorescence staining images of ZO-1 (green), E-cadherin (red), and nuclei (blue) in the ileum from Ap1m2fl/fl and Ap1m2ΔIEC female mice. Scale bars: 20 μm. (G) The trans-epithelial electrical resistance of isolated intestinal epithelium was measured with Ussing chamber. n = 3. Data represent the median. ns: not significant, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 (unpaired, two-tailed Mann–Whitney test).

AP-1B deficiency partially impaired the para-cellular integrity of the intestinal epithelium

Histological analysis with hematoxylin-eosin and Alcian-Blue staining showed that Ap1m2ΔIEC mice have no apparent abnormality in the intestine with proper epithelial differentiation, including Paneth and goblet cells (Fig. 1C and D).

To examine the intestinal epithelial permeability, we orally administrated 4 or 70 kDa FITC-dextran to mice, which is widely used to assess epithelial integrity in animal models.36 In Ap1m2fl/fl mice orally administered with tamoxifen, 70 kDa dextran was hardly detected in the plasma, while 4 kDa dextran was detected in small amounts. This is not significantly different from steady-state mouse values reported in a previous similar experiment,37 suggesting that oral administration of tamoxifen does not severely affect intestinal epithelial permeability. FITC-dextran translocation into the plasma was significantly increased in Ap1m2ΔIEC mice, and the amount translocated was size-dependent: the permeability of 70 kDa was much lower than that of 4 kDa (Fig. 1E).

Alternatively, immunofluorescence staining of ZO-1 and E-cadherin in the ileal epithelium did not show apparent abnormal localization in Ap1m2ΔIEC mice (Fig. 1F). We further measured trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TEER) using an Ussing chamber.28 The TEER of isolated mucus layers of Ap1m2ΔIEC mice was comparable to that of Ap1m2fl/fl mice (Fig. 1G). These data suggest that Ap1m2 deficiency has very little, if any, effect on the ionic conductance of the intestinal epithelium or tight junction formation; however, the concentration of FITC-dextran, a non-electrolyte tracer, increased in the blood, indicating increased paracellular fluid leakage without massive destruction of the tight junction.

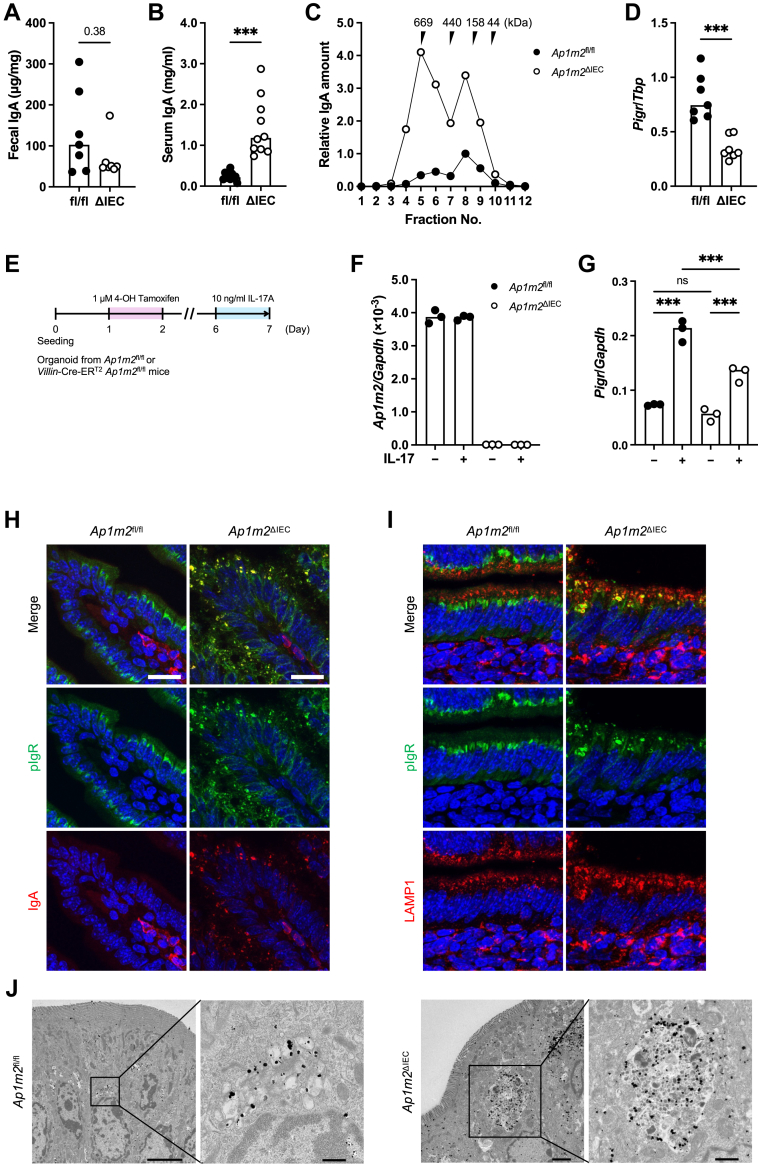

AP-1B deficiency led to the dysfunction of polymeric immunoglobulin receptor

We also measured the secretory IgA antibodies, a major component of the immune barrier in the intestinal tract. The amount of secretory IgA tended to be decreased in the feces of Ap1m2ΔIEC mice (Fig. 2A), whereas the serum IgA level was markedly elevated in these mice (Fig. 2B). Serum IgA mainly consists of 150 kDa monomeric, but not polymeric IgA. The size exclusion chromatography demonstrated that a high molecular weight (approximately 670 kDa) IgA, in addition to monomeric IgA detected around 150 kDa, was abundant in the serum of Ap1m2ΔIEC mice (Fig. 2C). These fractions most likely contained polymeric IgA because secretory component was detected in the high molecular weight IgA fractions by western blotting (Supplementary Figure S1). Thus, Ap1m2ΔIEC mice displayed an accumulation of polymeric IgA in the circulation.

Fig. 2.

AP-1B deficiency causes pIgR dysfunction and increases IgA in the blood. (A) and (B) IgA concentrations in feces in (A) and serum in (B) from Ap1m2fl/fl and Ap1m2ΔIEC female mice were measured by ELISA. n = 7 in (A) and n = 10 in (B) from two independent experiments. (C) Size exclusion chromatography fractionation profile of IgA in sera were pooled from Ap1m2fl/fl and Ap1m2ΔIEC female mice. The IgA levels in each fraction were measured by ELISA. (D) Quantitative PCR analysis of Pigr expression in the ileum from Ap1m2fl/fl and Ap1m2ΔIEC female mice. Tbp was analyzed as a reference gene. n = 7. (E) Experimental schedule for a treatment of intestinal organoids with IL-17. Organoids were generated from the ileum of Ap1m2fl/fl and Villin-Cre-ERT2Ap1m2fl/fl mice and treated with 1 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen on day 1–2, followed 10 ng/ml recombinant IL-17A on day 6–7. (F) and (G) Quantitative PCR analysis of Ap1m2 (F) and Pigr (G) expression in Ap1m2fl/fl or Ap1m2ΔIEC organoids. Gapdh was analyzed as a reference gene. (H) and (I) Immunofluorescence images of pIgR (green), IgA or LAMP1 (red), and nuclei (blue) in the ileum from Ap1m2fl/fl and Ap1m2ΔIEC female mice. Scale bars: 20 μm. (J) Immuno-electron microscopic images of epithelial cells in the ileum from Ap1m2fl/fl and Ap1m2ΔIEC female mice for pIgR. Scale bars: 0.5 μm (left) or 1.0 μm (right). Data represent the median. ns: not significant, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 (unpaired, two-tailed Mann–Whitney test for comparison of two groups or two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test for comparison of multiple groups).

We investigated the expression level and intracellular localization of polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR), which is responsible for transporting IgA from the lamina propria to the gut lumen. The expression level of Pigr was downregulated in IECs of Ap1m2ΔIEC mice (Fig. 2D). Given that the expression of Pigr is regulated by IL-17 signaling,38,39 we further examined the association of Pigr expression with IL-17 signaling using the intestinal organoid culture system. Ap1m2 deficiency in the organoid was induced by adding 4-hydroxytamoxifen, an active metabolite of tamoxifen, to the organoid culture medium (Fig. 2E and F). Treatment with IL-17A upregulated the Pigr expression in the organoid cultures; however, the upregulation of Pigr was observed to a lesser extent in Ap1m2-deficient organoids than in Ap1m2-sufficient control (Fig. 2G). These data illustrate that Ap1m2 deficiency impaired IL17-signaling, resulting in lower expression of Pigr.

We further conducted immunofluorescence staining to analyze the intracellular localization of pIgR. Consistent with a previous report,40 pIgR was detected in the perinuclear components of IECs of control mice (Fig. 2H). Meanwhile, in Ap1m2ΔIEC mice, pIgR was abnormally accumulated in the large granules scattered throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 2H). IgA was not detectable in the control IECs and was only observed in the IgA-producing cells of the lamina propria (Fig. 2H). Interestingly, Ap1m2-deficient IECs deposited IgA in large intracellular granules and colocalized well with pIgR (Fig. 2H). The pIgR-positive large intracellular granules in Ap1m2ΔIEC mice were commonly co-labeled with the lysosome marker LAMP1 (Fig. 2I). Furthermore, immunoelectron microscopy analysis also confirmed that pIgR was localized within the lysosome-associated large membrane compartments containing electron-dense amorphous contents in the IECs of Ap1m2ΔIEC mice (Fig. 2J). Based on these observations, we reasoned that the absence of the AP-1B complex significantly affected transcytosis of the IgA-pIgR complex, leading to its accumulation in lysosome-like large granules.

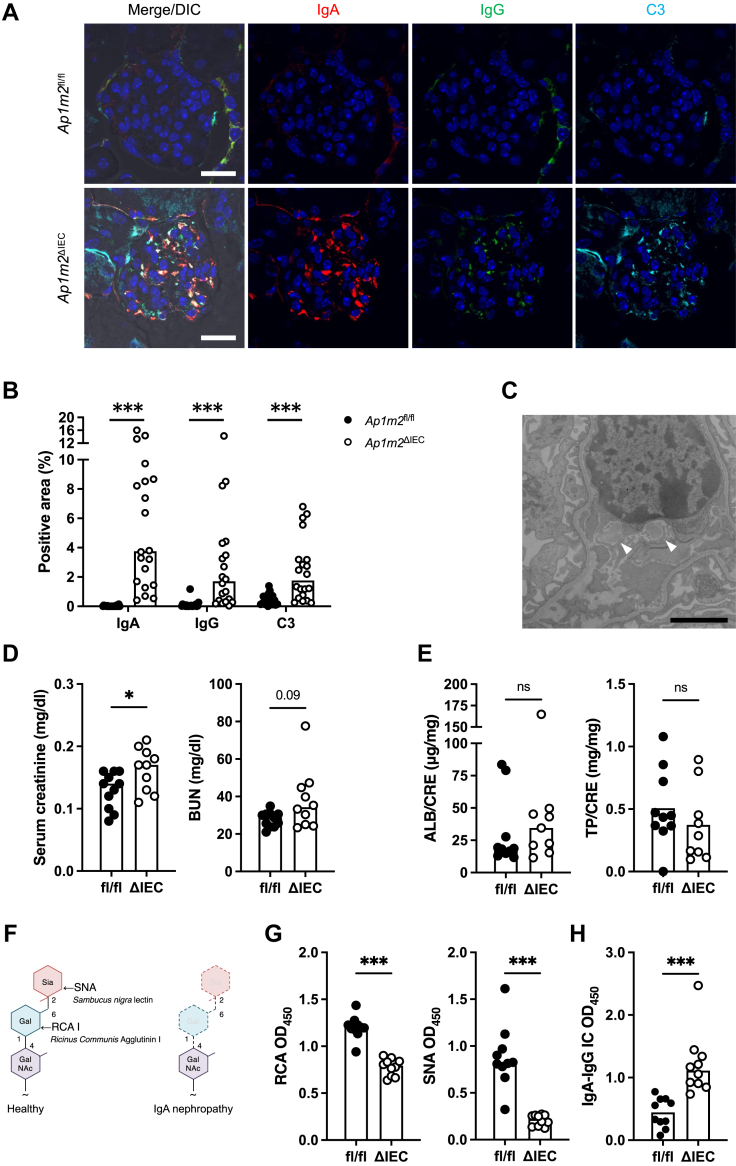

Ap1m2ΔIEC mice developed IgA deposition spontaneously in the kidney glomeruli

Elevated total serum IgA levels are considered predisposing factors for various inflammatory disorders.41, 42, 43 Therefore, we carefully analyzed various systemic tissues of Ap1m2ΔIEC mice unbiasedly and found IgA deposits in the kidney glomeruli (Fig. 3A and B). IgG and complement C3 were also detected in IgA deposits (Fig. 3A and B). Furthermore, transmission electron microscopy revealed electron-dense deposits in the mesangial area of the glomeruli of Ap1m2ΔIEC mice (Fig. 3C). These pathological changes are reminiscent of IgAN. Indeed, serum creatinine was significantly increased, and blood urea nitrogen tended to be increased in Ap1m2ΔIEC mice (Fig. 3D), whereas urinary albumin and total protein levels were comparable between the two groups (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

IgA–IgG immune complex is deposited in the glomeruli of Ap1m2ΔIECfemale mice. (A) Immunofluorescence images of IgA (red), IgG (green), complement C3 (cyan), and nuclei (blue) in the kidney from Ap1m2fl/fl and Ap1m2ΔIEC female mice. Scale bars: 20 μm. (B) Quantitative data of (A): the percentage of IgA+, IgG+, or C3+ area in a glomerulus area were quantified. n = 20, five glomeruli each from four different mice. (C) A representative transmission electron microscopic image of the mesangial cells in the kidney from Ap1m2ΔIEC female mice. Arrowheads indicate electron-dense deposits in the mesangial area. Scale bar: 2.0 μm. (D) Creatinine and blood urea nitrogen concentration in their sera of Ap1m2fl/fl (n = 11) and Ap1m2ΔIEC (n = 10) female mice from two independent experiments. (E) Urinary ratio of albumin and total protein to creatinine in Ap1m2fl/fl (n = 10) and Ap1m2ΔIEC (n = 9) female mice. (F) Illustration of lectin-binding assay. When IgA is completely glycosylated, galactose is added to N-acetylgalactosamine, followed by the addition of sialic acid. Therefore, IgA is recognized by Ricinus communis agglutinin I (RCA) or Sambucus nigra lectin (SNA). (G) Quantification of galactose or sialic acid in the serum IgA glycans by lectin-binding assay. 100 ng serum IgA was reacted with RCA or SNA, and the optical density (OD) was measured. n = 10 from two independent experiments. (H) Quantification of IgA-IgG immune complex (IC) in the serum. Serum IgA-IgG immune complex captured by anti-IgG antibody was detected with anti-IgA antibody. The bar graphs show optical density values at 450 nm. n = 10 from two independent experiments. Data represent the median. ns: not significant, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 (unpaired, two-tailed Mann–Whitney test).

Aberrant IgA glycosylation and IgA-IgG complex were formed in Ap1m2ΔIEC mice

Aberrant IgA glycosylation has been well documented to lead to IgA deposition in the glomeruli of human patients with IgAN and several IgAN animal models.14,44, 45, 46 Therefore, we analyzed IgA glycosylation by lectin-binding assay with galactose-recognizing Ricinus communis agglutinin-I (RCA) and sialic acid-recognizing Sambucus nigra lectin (SNA).31 As sialic acid is added after galactose during IgA glycosylation, galactose-deficient IgA usually lacks sialic acid (Fig. 3F). Consequently, serum IgA from Ap1m2ΔIEC mice had significantly lower reactivity with both RCA and SNA compared with that from Ap1m2fl/fl mice, indicating lower levels of galactose and sialic acid in IgA glycosylation (Fig. 3G). Anti-glycan IgG binds to aberrantly glycosylated IgA to form the IgA-IgG immune complex, therefore, we further examined IgA-IgG complexes using anti-IgG and anti-IgA antibodies for capture and detection, respectively. We observed that the IgA-IgG immune complex was significantly increased in the serum of Ap1m2ΔIEC mice (Fig. 3H). Although all of these analyses were performed using female mice, the IgAN-like phenotypes—including renal depositions, aberrant IgA glycosylation, and immune complex formation—were also observed in male Ap1m2ΔIEC mice, regardless of sex differences (Supplementary Figure S2).

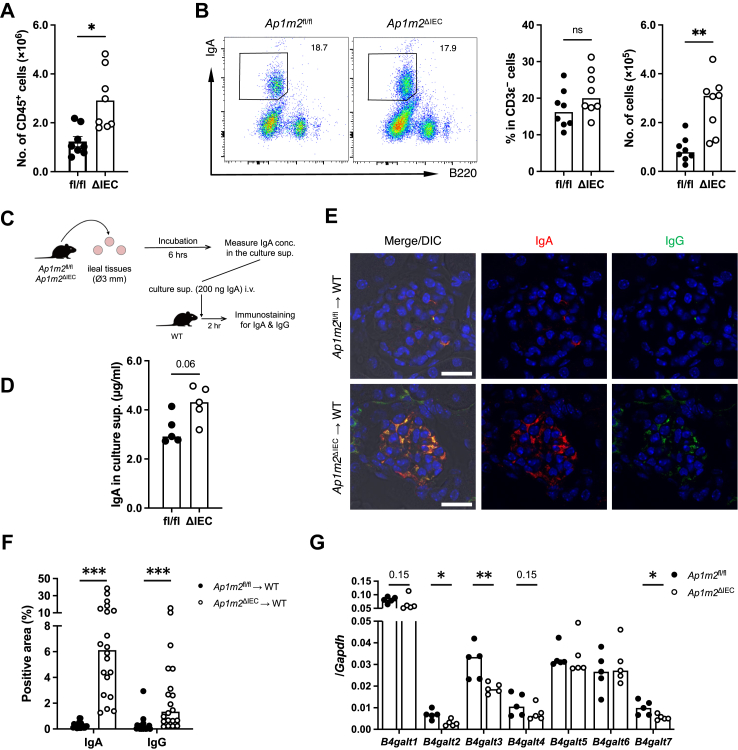

IgA produced in the intestine of Ap1m2ΔIEC mice caused IgA deposition in the kidney

As the intestinal immune system is a major site of IgA production, we investigated the IgA response in the intestinal mucosa. Flow cytometric analysis showed an increase in the number of CD45+ leucocytes and IgA+ plasma cells in the ileal lamina propria of Ap1m2ΔIEC mice (Fig. 4A and B; Supplementary Figures S3). To measure IgA production in the intestine, we performed ex vivo ileal organ culture, followed by IgA quantification by ELISA (Fig. 4C). Consistent with the flow cytometry observation, the IgA amount increased in the culture supernatant of the ileal tissue from Ap1m2ΔIEC mice (Fig. 4D), suggesting augmentation of IgA response in the absence of AP-1B complex. Peyer's patches and mesenteric lymph nodes are major induction sites for mucosal IgA responses via germinal center reactions in a T cell-dependent manner.47 However, the frequency and number of germinal center B cells and follicular helper T cells that facilitate the germinal center reaction were comparable in these lymphoid tissues between the Ap1m2ΔIEC and control mice (Supplementary Figures S4 and S5). Correspondingly, the frequency and number of IgA+ cells in the Peyer's patches and mesenteric lymph nodes were not changed in Ap1m2ΔIEC mice. These data imply that T cell-independent IgA production may be enhanced in the intestine of Ap1m2ΔIEC mice.

Fig. 4.

Intestinal-derived IgA causes deposition in the kidney. (A) and (B) Flow cytometric analysis of leucocytes isolated from the ileal lamina propria of Ap1m2fl/fl and Ap1m2ΔIEC female mice. The total number of CD45+ cells (A); representative plots, the frequency and the number of IgA+ B cells (B). n = 8 from two independent experiments. (C) Experimental procedure: (D) Ileal tissues were sampled from Ap1m2fl/fl and Ap1m2ΔIEC female mice and were cultured for 6 h. Culture supernatant was collected, and IgA secreted into the supernatant was measured by ELISA. n = 5. and (E) The pooled culture supernatant of each group was adjusted to contain 200 ng IgA and injected intravenously into wild-type female mice. After 2 h, immunofluorescence analysis was performed. Images show IgA (red), IgG (green), and nuclei (blue) in the kidney from culture supernatant-treated wild-type female mice. Scale bars: 20 μm. (F) Quantitative data of (D): the percentage of IgA+ or IgG+ area in a glomerulus area. n = 20, five glomeruli each from four different mice. (G) Quantitative PCR analysis of B4galt1 to 7 expressions in B cells isolated from the ileal lamina propria of Ap1m2fl/fl and Ap1m2ΔIEC female mice. Gapdh was analyzed as a reference gene. n = 5. Data represent the median. ns: not significant, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 (unpaired, two-tailed Mann–Whitney test).

To further investigate whether intestinal-derived IgA was responsible for renal IgA deposition, intestinal culture supernatants were intravenously administered to wild-type mice (Fig. 4C). The Ap1m2ΔIEC mice-derived intestinal culture supernatants caused IgA and IgG deposition in the kidney glomeruli (Fig. 4E and F). In contrast, the supernatant from Ap1m2fl/fl control mice, whose IgA concentration was adjusted equivalent to that of Ap1m2ΔIEC mice, did not cause IgA and IgG deposition.

We further investigated the underlying mechanism of aberrant IgA glycosylation in Ap1m2ΔIEC mice. To this end, we purified intestinal B cells and examined expression profiles of the β-1,4-galactosyltransferase family (encoded by B4galt1–7) because this enzyme family is responsible for glycosylation of IgA, and its deletion or downregulation predisposes the model animals to IgAN with renal IgA deposits.44,48 Among the β-1,4-galactosyltransferase family molecules, B4galt2, B4galt3, and B4galt7 were significantly decreased in Ap1m2ΔIEC mice than in control mice (Fig. 4G).

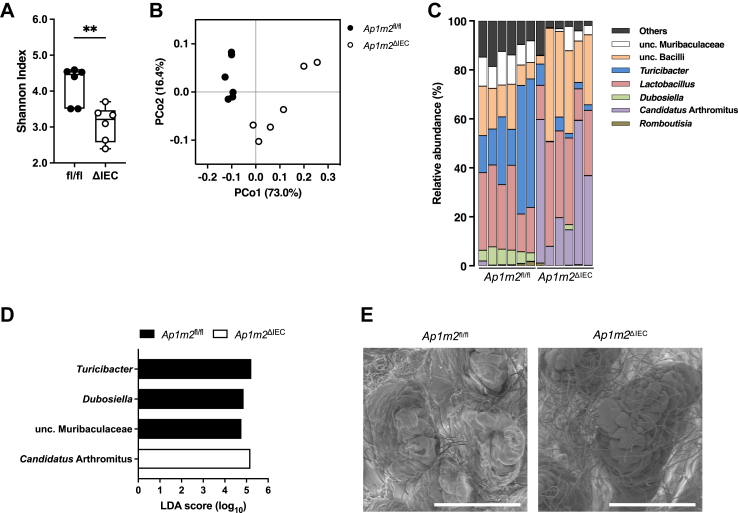

AP-1B deficiency caused the development of gut dysbiosis

Intestinal barrier dysfunction often affects the gut microbial community, and an altered microbial composition, termed dysbiosis, is associated with the development of IgAN.49,50 We hypothesized that AP-1B deficiency causes intestinal dysbiosis, which may be responsible for the enhanced IgA response and aberrant glycosylation. To examine this assumption, we initially performed 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing analysis of ileal microbiota and observed that α-diversity was much lower in Ap1m2ΔIEC mice (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, based on β-diversity, intestinal microbial compositions were distinct between Ap1m2ΔIEC and Ap1m2fl/fl mice (Fig. 5B). Notably, the intestinal microbiota in Ap1m2ΔIEC mice was characterized by the overrepresentation of Candidatus Arthromitus as well as the underrepresentation of Turicibacter, Dubosiella, and unclassified Muribaulaceae (Fig. 5C and D). Scanning electron microscopic analysis on the ileal villus displayed the expansion of filamentous bacteria considered Candidatus Arthromitus in Ap1m2ΔIEC mice (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5.

Ap1m2ΔIECmice exhibit dysbiosis in the gut microbiota. Microbiota profiles in the ileum from Ap1m2fl/fl and Ap1m2ΔIEC female mice. n = 6. (A) Species richness and evenness (Shannon index). Data represent the median, interquartile range, and minimum and maximum values. ∗∗p < 0.01 (unpaired, two-tailed Mann–Whitney test). (B) Principal coordinate analysis based on the weighted UniFrac analysis is shown. (C) Genus-level taxonomic distribution of individual mice. Values represent relative abundance (%). (D) Differentially abundant taxa at the genus level with an average relative abundance >0.3%. Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) shows significantly different genera (LDA score >2). (E) Scanning electron microscopic image of ileal epithelium from Ap1m2fl/fl and Ap1m2ΔIEC female mice. Scale bars: 100 μm.

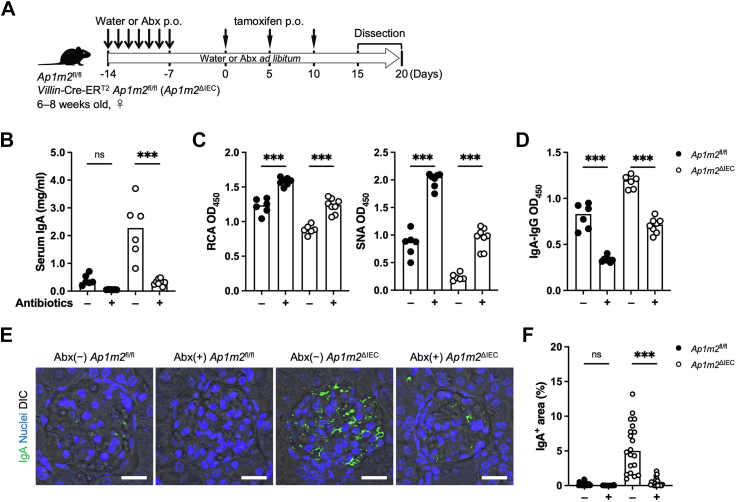

Antibiotic treatment resolved IgA deposits in the kidney glomerulus

To ascertain whether the altered microbial community caused by AP-1B deficiency contributes to the IgA deposition in the kidney, the mice received an antibiotic cocktail in drinking water to eradicate intestinal microbes (Fig. 6A). The antibiotic treatment markedly decreased the amount of serum IgA in the Ap1m2ΔIEC mice as well as Ap1m2fl/fl mice (Fig. 6B). The antibiotic treatment increased IgA glycosylation and decreased IgA-IgG immune complex formation in control Ap1m2fl/fl mice (Fig. 6C and D). Likewise, in the Ap1m2ΔIEC mice, the galactosylation and sialylation status of IgA was restored, and the IgA-IgG immune complex was decreased to nearly the same level as that in untreated Ap1m2fl/fl mice (Fig. 6C and D). Significantly, the renal IgA deposition was alleviated in antibiotics-treated Ap1m2ΔIEC mice (Fig. 6E and F).

Fig. 6.

Gut microbiota contribute to the development of IgA nephropathy in Ap1m2ΔIECmice. (A) Experimental schedule of antibiotic treatment on Ap1m2fl/fl (n = 6 or 7) and Ap1m2ΔIEC (n = 6 or 8) female mice from two independent experiments. Antibiotics were administered in their drinking water ad libitum from the first two weeks before tamoxifen administration until dissection for experiments. During the first week, the antibiotic cocktail was additionally given orally once daily. (B) Serum IgA concentrations were measured by ELISA. (C) Serum IgA glycosylation was evaluated by lectin binding assay. (D) Serum IgA-IgG immune complex (IC) was quantified. (E) Immunofluorescence image of IgA (green) in kidneys. Scale bars: 50 μm. (F) Quantitative data of (D): the percentage of IgA+ area in a glomerulus area. n = 20, five glomeruli each from four different mice. Data represent the median. ns: not significant, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 (two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test).

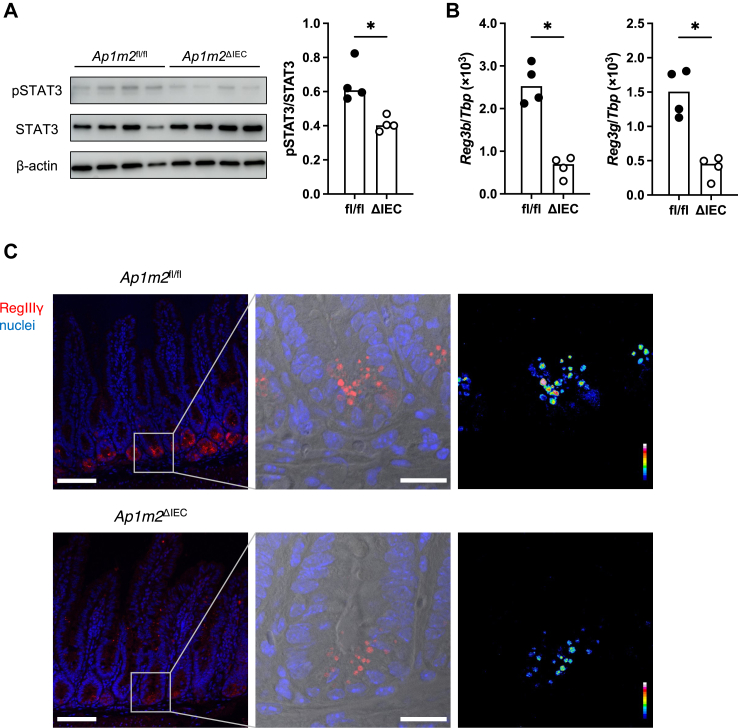

AP-1B deficiency impaired antimicrobial peptide production due to decreased IL-22 receptor signal

Finally, we investigated the underlying mechanism by which epithelial AP-1B deficiency causes intestinal dysbiosis as represented by the expansion of Candidatus Arthromitus. Early works have demonstrated that antimicrobial lectins like RegIIIγ play a vital role in the containment of this bacterial species.51 As STAT3 activation upon stimulation of IL-22Ra1 with IL-22 contributes to the production of the Reg family of antimicrobial lectins,52,53 we analyzed phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3) levels in the ileal epithelium. The pSTAT3 intensities were significantly attenuated in Ap1m2ΔIEC mice (Fig. 7A). Correspondingly, the expressions of Reg3b and Reg3g were also diminished in the ileal epithelium of Ap1m2ΔIEC mice (Fig. 7B). Immunofluorescence analysis further confirmed the reduction of RegIIIγ at the protein level in the intestinal crypt regions of Ap1m2ΔIEC mice (Fig. 7C). These data illustrate that AP-1B deficiency results in the downregulation of the Reg family of antimicrobial lectins, mainly by Paneth cells, owing to the mitigation of STAT3 signaling.

Fig. 7.

Loss of AP-1B decreases IL-22-STAT3 signal, leading to decreased RegIIIγ expression in the intestine. (A) Western blot analysis of pSTAT3, STAT3, and β-actin in the intestinal epithelium from Ap1m2fl/fl and Ap1m2ΔIEC female mice. n = 4. (B) Quantitative PCR analysis of Reg3b and Reg3g in the intestine from ileal Ap1m2fl/fl and Ap1m2ΔIEC female mice. Tbp was analyzed as a reference gene. n = 4. (C) Immunofluorescence images of RegIIIγ (red) and nuclei (blue) in the intestine from Ap1m2fl/fl and Ap1m2ΔIEC female mice. Scale bars: 100 μm. Data represent the median. ∗p < 0.05 (unpaired, two-tailed Mann–Whitney test).

Discussion

In this study, we observed IEC barrier dysfunctions with the production of aberrantly glycosylated IgA in the Ap1m2ΔIEC mice. These IgA molecules formed complexes with IgG in the bloodstream, resulting in the deposition of IgA-IgG complexes with complement C3 in the kidney glomeruli, a characteristic feature of IgAN. The excess amount of aberrant glycosylated IgA in the blood, which may be attributed to epithelial barrier dysfunction and resulting dysbiosis, were responsible for the deposition of the IgA-IgG complex in the kidney. Therefore, this animal model is expected to help analyze the association between IEC dysfunction and IgAN onset.

Increasing evidence suggests an association between IgAN and the intestinal tract. Patients with IgAN showed significantly higher intestinal permeability than healthy subjects.50,54 Furthermore, intestinal dysbiosis is evident in patients with IgAN, particularly in progressors.49 A clinical survey has also demonstrated that approximately 20% of European patients with IgAN were accompanied by gastrointestinal complications, such as inflammatory bowel diseases and celiac disease.55 In support of this survey, a GWAS of European and East Asian ancestry has shown that most risk loci for IgAN are linked with those of inflammatory bowel disease or maintenance of the intestinal epithelial barrier and response to mucosal pathogens.20 The latest GWAS of IgAN across 17 international cohorts also indicated the causal genes in intestinal mucosal cells.21 These observations strengthen the significance of intestinal immune response in IgAN pathogenesis. In this study, using the new animal model, Ap1m2ΔIEC mice, we demonstrate that IEC dysfunction leads to the deposition of IgA-IgG complexes in the kidney glomeruli. This provides novel experimental evidence supporting the hypothesis that the gut–kidney axis plays a vital role in the pathogenesis of IgAN.

pIgR mediates selective transcytosis of polymeric IgA across IECs. Gene polymorphisms of pIgR gene are associated with IgAN.56,57 A missense mutation (A580V) in human pIgR reduces the transcytosis efficiency of polymeric IgA and increases the risk of developing IgAN.58 Our studies show that AP-1B secures the expression and intracellular trafficking of pIgR in IECs. The attenuation of IL-17A-dependent Pigr induction due to AP-1B deficiency most likely results from impaired trafficking of IL-17 receptor to the basolateral membrane. Additionally, in the Ap1m2ΔIEC mice, pIgR was accumulated in the LAMP-1-positive granules along with IgA, indicating that the IgA-bound pIgR was mis-targeted to the lysosome-like vesicles. Thus, the absence of AP-1B may not completely abrogate pIgR basolateral sorting essential for IgA binding, but rather impair the subsequent transport of pIgR-IgA complexes from the basolateral to the apical membrane. AP-1B was initially considered to regulate basolateral protein sorting; however, recent findings revealed that the functional loss of AP-1B affects the apical transport of several membrane proteins. For instance, we previously found that Ap1m2 deficiency partially compromised the apical localization of villin and sucrase in IECs.11 Proteomic analysis of subcellular membrane fractions from Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells also demonstrated that several apical proteins, in addition to basolateral proteins, were missorted upon Ap1m2-knockdown.59 Moreover, Ap1m2 knockdown in MDCK cells impairs the apical sorting of newly synthesized glycosyl phosphatidyl inositol-anchored proteins in the biosynthetic pathway.60 Furthermore, apical recycling and basal-to-apical transcytosis routes are inhibited in these cells.60 Our data revealed a novel function in which AP-1B controls pIgR function through dual regulation of intracellular trafficking and signaling pathways, thereby controlling IgA secretion.

High serum IgA1 levels are a major laboratory finding of IgAN. Similarly, Ap1m2ΔIEC mice also displayed the prominent elevation of serum IgA. Given the detection of polymeric IgA with secretory component in blood, the increase in serum IgA levels is most likely attributable to leakage from the mucosal tissue. The intestine may be the primary source of increased IgA in the serum because Ap1m2 deficiency increased the number of IgA + B cells in the gut lamina propria and the amount of IgA in the ex vivo intestinal culture supernatant. Additionally, administration of IgA from Ap1m2-deficient intestinal tissue cultures caused IgA deposition in the kidneys of wild-type mice. pIgR-dependent IgA transcytosis was impaired in Ap1m2ΔIEC mice, as mentioned above. Notably, pIgR−/− mice also exhibit increased serum IgA and IgA + B cells in the lamina propria.61,62 Therefore, aberrant influx of IgA from the intestinal mucosa into the bloodstream may result from impaired pIgR-dependent IgA transcytosis and overproduction.

Ap1m2ΔIEC mice have increased amounts of poorly glycosylated IgA. This observation was in line with the downregulation of glycosylation enzymes in B cells from the lamina propria of Ap1m2ΔIEC mice. We also observed enhanced paracellular translocation of the luminal contents and activation of the IgA response in the ileum of these mice. Therefore, it is plausible that the enhanced translocation of gut microbes or their components may activate the intestinal immune system, leading to the downregulation of glycosylation enzymes and the production of aberrantly glycosylated IgA. Indeed, inflammatory stimuli downregulate IgA glycosylation.63 Moreover, microbiota depletion by antibiotic treatment recovered the glycosylation levels of IgA in the Ap1m2ΔIEC mice. The activation of toll-like receptor 9, which recognizes unmethylated CpG motifs prevalent in microbes, exacerbates IgAN symptoms in mice, depending on interleukin-6 and a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL).64 APRIL and B-cell activation factor (BAFF) are essential for B cell survival and IgA class switching. These cytokines are highly expressed in patients with IgAN and may contribute to disease progression.45,65 Meanwhile, mRNA expression of APRIL and BAFF was not altered in the Ap1m2ΔIEC mice. Therefore, other unknown factors may dysregulate IgA glycosylation in these mice.

The depletion of gut microbiota ameliorated renal IgA deposition in Ap1m2ΔIEC mice. Consistent with our data, human BAFF-transgenic mice develop IgAN when housed under specific pathogen-free conditions, yet fail to manifest the illness in germ-free environments.45 Antibiotic treatment also prevented the symptoms of IgAN in human IgA1-knockin and human CD89-transgenic mice.66,67 Based on these findings, the mucosal IgA response to intestinal microbes is vital for the development of IgAN.

The activation of mucosal IgA response in Ap1m2ΔIEC mice may be caused by intestinal dysbiosis characterized by overrepresentation of Candidatus Arthromitus, a previously designated segmented filamentous bacterium. This bacterial species serves as a potent stimulator of the intestinal immune system, particularly by inducing Th17 and IgA responses.68, 69, 70 The expansion of Candidatus Arthromitus possibly results from the downregulation of RegIII family proteins, as well as the reduction of secretory IgA due to impaired pIgR-dependent transcytosis. The production of antigen-specific IgA triggered by Candidatus Arthromitus colonization may play a role in preventing overgrowth of the latter.71 Activation-induced cytidine deaminase-deficient mice, which lack hypermutated IgA, display aberrant Candidatus Arthromitus expansion.72 In addition to secretary IgA, RagIIIγ also limits the colonization of Candidatus Arthromitus in the mucus layer.51 The expression of Reg3 family genes in IECs is mainly regulated by the IL-22-STAT3 axis.52,53 Notably, STAT3 phosphorylation was significantly attenuated in AP-1B-deficient IECs. These data provide evidence that AP-1B critically contributes to securing IL-22 signaling, likely through basolateral sorting of IL-22RA1, an IL-22 receptor.

This study has several limitations. We showed that epithelial AP-1B deficiency leads to the generation of aberrantly glycosylated IgA. Given that restoration of IgA glycosylation by antibiotic treatment was also observed in Ap1m2fl/fl mice, the suppression of IgA glycosylation by intestinal bacteria may occur to a low degree even under steady-state conditions.

In conclusion, our study provides experimental evidence of a causal relationship between IgAN and intestinal barrier disruption by using Ap1m2ΔIEC mice as a new LGS model. This model may be applied to the development and improvement of promising treatments for IgAN. Considering that emerging therapies with fecal microbiota transplantation or Nefecon have shown promising efficacy in treating IgAN,73, 74, 75 the intestinal microbiota and immunity should be therapeutic targets for this disease.

Contributors

Y.K., S.Ki., and K.H. conceptualized the study. Y.K. conducted the experiments and analyzed the data. M.H. established the tamoxifen administration protocol. K.T. performed the organoid experiment. T.S., A.H., and S.S. performed the electron microscopy analysis. S.Ka. performed the Ussing chamber experiment. S.Ko. provided a method for analyzing the 16S rRNA sequencing data. D.T. conducted the data analysis of revise experiments. HO provided the mice. Y.K., S.Ki., and K.H. wrote the manuscript. S.Ki and K.H. supervised the study.

Data sharing statement

16S rRNA sequencing data were deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan database (DRA017446).

Declaration of interests

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Ji-Yang Wang, and Prof. Reiko Shinkura for valuable discussions; Prof. Masahiko Watanabe, Dr. Miwako Yamasaki, Dr. Kohtaro Konno, Dr. Narumi Ishihara, and Dr. Ryohtaroh Matsumoto for their technical assistance; the animal facility at the Keio University Faculty of Pharmacy for the breeding and maintenance of our mouse strains; and the Yoshida Scholarship Foundation for the support of research activity. This work was supported by grants from AMED grant number JP21gm6510006 (S S. and T.S.); AMED-CREST grant numbers 22gm1310009h0003 and 23gm1310009h0004 (K.H.); JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research 19K07239 and 23H02739 (S.Ki.), 20H05876, 20H00509, 22K19445, and 23H05482 (K.H.); JST CREST grant numbers JPMJPR19H3 and JPMJCR19H3 (S.Ki.) and JPMJCR19H1 (K.H.); Fuji Foundation for Protein Research (K.H.); and Keio University Program for the Advancement of Next Generation Research Projects (S. Ki.).

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.105256.

Contributor Information

Shunsuke Kimura, Email: kimura-sn@keio.jp.

Koji Hase, Email: hase.a6@keio.jp.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Peterson L.W., Artis D. Intestinal epithelial cells: regulators of barrier function and immune homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:141–153. doi: 10.1038/nri3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bevins C.L., Salzman N.H. Paneth cells, antimicrobial peptides and maintenance of intestinal homeostasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:356–368. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johansson M.E.V., Hansson G.C. Immunological aspects of intestinal mucus and mucins. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:639–649. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rojas R., Apodaca G. Immunoglobulin transport across polarized epithelial cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:944–956. doi: 10.1038/nrm972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei M., Shinkura R., Doi Y., Maruya M., Fagarasan S., Honjo T. Mice carrying a knock-in mutation of Aicda resulting in a defect in somatic hypermutation have impaired gut homeostasis and compromised mucosal defense. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:264–270. doi: 10.1038/ni.1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uchimura Y., Fuhrer T., Li H., et al. Antibodies Set boundaries limiting microbial metabolite penetration and the resultant mammalian host response. Immunity. 2018;49:545–559.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakatsu F., Hase K., Ohno H. The role of the clathrin adaptor AP-1: polarized sorting and beyond. Membranes. 2014;4:747–763. doi: 10.3390/membranes4040747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohno H., Tomemori T., Nakatsu F., et al. μ1B, a novel adaptor medium chain expressed in polarized epithelial cells 1. FEBS Lett. 1999;449:215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00432-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fölsch H., Ohno H., Bonifacino J.S., Mellman I. A novel clathrin adaptor complex mediates basolateral targeting in polarized epithelial cells. Cell. 1999;99:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81650-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi D., Hase K., Kimura S., et al. The epithelia-specific membrane trafficking factor AP-1B controls gut immune homeostasis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:621–632. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hase K., Nakatsu F., Ohmae M., et al. AP-1B-mediated protein sorting regulates polarity and proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells in mice. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:625–635. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai K.N., Tang S.C.W., Schena F.P., et al. IgA nephropathy. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2 doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiki Y., Odani H., Takahashi M., et al. Mass spectrometry proves under-O-glycosylation of glomerular IgA1 in IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2001;59:1077–1085. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0590031077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moldoveanu Z., Wyatt R.J., Lee J.Y., et al. Patients with IgA nephropathy have increased serum galactose-deficient IgA1 levels. Kidney Int. 2007;71:1148–1154. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki H., Yasutake J., Makita Y., et al. IgA nephropathy and IgA vasculitis with nephritis have a shared feature involving galactose-deficient IgA1-oriented pathogenesis. Kidney Int. 2018;93:700–705. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomana M., Matousovic K., Julian B.A., Radl J., Konecny K., Mestecky J. Galactose-deficient IgA1 in sera of IgA nephropathy patients is present in complexes with IgG. Kidney Int. 1997;52:509–516. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomana M., Novak J., Julian B.A., Matousovic K., Konecny K., Mestecky J. Circulating immune complexes in IgA nephropathy consist of IgA1 with galactose-deficient hinge region and antiglycan antibodies. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:73–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI5535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maillard N., Wyatt R.J., Julian B.A., et al. Current understanding of the role of complement in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:1503–1512. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014101000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waldherr R., Seelig H.P., Rambausek M., Andrassy K., Ritz E. Deposition of polymeric IgA1 in idiopathic mesangial IgA-glomerulonephritis. Klin Wochenschr. 1983;61:911–915. doi: 10.1007/BF01537531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiryluk K., Li Y., Scolari F., et al. Discovery of new risk loci for IgA nephropathy implicates genes involved in immunity against intestinal pathogens. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1187–1196. doi: 10.1038/ng.3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiryluk K., Sanchez-Rodriguez E., Zhou X.J., et al. Genome-wide association analyses define pathogenic signaling pathways and prioritize drug targets for IgA nephropathy. Nat Genet. 2023;55:1091–1105. doi: 10.1038/s41588-023-01422-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salzman N.H., Bevins C.L. Dysbiosis—a consequence of Paneth cell dysfunction. Semin Immunol. 2013;25:334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berbers R.M., Franken I.A., Leavis H.L. Immunoglobulin A and microbiota in primary immunodeficiency diseases. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;19:563–570. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fasano A., Shea-Donohue T. Mechanisms of Disease: the role of intestinal barrier function in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal autoimmune diseases. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2:416–422. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mu Q., Kirby J., Reilly C.M., Luo X.M. Leaky gut as a danger signal for autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. 2017;8:598. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kinashi Y., Hase K. Partners in leaky gut syndrome: intestinal dysbiosis and autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.673708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El Marjou F., Janssen K.P., Chang B.H.J., et al. Tissue-specific and inducible Cre-mediated recombination in the gut epithelium. Genesis. 2004;39:186–193. doi: 10.1002/gene.20042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karaki S.-I. A technique of measurement of gastrointestinal luminal nutrient sensing and these absorptions: ussing chamber (Short-Circuit current) technique. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 2023;69:164–175. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.69.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato T., Vries R.G., Snippert H.J., et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459:262–265. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimura S., Nakamura Y., Kobayashi N., et al. Osteoprotegerin-dependent M cell self-regulation balances gut infection and immunity. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1–16. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13883-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chintalacharuvu S.R., Emancipator S.N. The glycosylation of IgA produced by murine B cells is altered by Th2 cytokines. J Immunol. 1997;159:2327–2333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weigmann B., Tubbe I., Seidel D., Nicolaev A., Becker C., Neurath M.F. Isolation and subsequent analysis of murine lamina propria mononuclear cells from colonic tissue. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2307–2311. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shibata S., Iseda T., Mitsuhashi T., et al. Large-area fluorescence and electron microscopic correlative imaging with multibeam scanning electron microscopy. Front Neural Circuits. 2019;13:29. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2019.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Komiyama S., Yamada T., Takemura N., Kokudo N., Hase K., Kawamura Y.I. Profiling of tumour-associated microbiota in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89963-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Segata N., Izard J., Waldron L., et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang L., Llorente C., Hartmann P., Yang A.-M., Chen P., Schnabl B. Methods to determine intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation during liver disease. J Immunol Methods. 2015;421:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu H., Hong X.L., Sun T.T., Huang X.W., Wang J.L., Xiong H. Fusobacterium nucleatum exacerbates colitis by damaging epithelial barriers and inducing aberrant inflammation. J Dig Dis. 2020;21:385–398. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cao A.T., Yao S., Gong B., Elson C.O., Cong Y. Th17 cells upregulate polymeric Ig receptor and intestinal IgA and contribute to intestinal homeostasis. J Immunol. 2012;189:4666–4673. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar P., Monin L., Castillo P., et al. Intestinal interleukin-17 receptor signaling mediates reciprocal control of the gut microbiota and autoimmune inflammation. Immunity. 2016;44:659–671. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guzman M., Lundborg L.R., Yeasmin S., et al. An integrin αEβ7-dependent mechanism of IgA transcytosis requires direct plasma cell contact with intestinal epithelium. Mucosal Immunol. 2021;14:1347–1357. doi: 10.1038/s41385-021-00439-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]