Abstract

Objective:

We examined prescription-related opioid use disorder (POUD) prevalence, individual symptoms, severity, characteristics, and treatment by prescription opioid misuse status among adults with prescription opioid use.

Methods:

Cross-sectional study using nationally representative data from 47,291 adults aged ≥18 years who participated in the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Past-year POUD used DSM-5 criteria.

Results:

Among US adults with past-year prescription opioid use, 12.1% (95% CI, 11.1%–13.1%) misused prescription opioids, and 7.0% (95% CI, 6.2%–8.9%) had POUD. Among adults with POUD, 62.0% (95% CI, 56.7%–67.2%) reported no prescription opioid misuse, including 49.1% (95% CI, 43.5%–54.7%) with mild POUD, 11.0% (95% CI, 6.5%–15.4%) with moderate POUD, and 1.9% (95% CI, 0.6%–3.2%) with severe POUD. Prevalence of POUD was 4.5 times higher (prevalence ratio = 4.5, 95% CI, 3.6–5.6) among those reporting prescription opioid misuse (22.0%, 95% CI, 18.6%–25.8%) than those reporting use without misuse (4.9%, 95% CI, 4.2%–5.7%). Among adults reporting prescription opioid use without misuse, high POUD prevalence was found for those with ≥3 emergency department visits (16.4%, 95% CI, 11.5%–23.0%), heroin use/use disorder (17.1%, 95% CI, 5.2%–43.8%), prescription sedative/tranquilizer use disorder (36.2%, 95% CI, 23.6%–51.1%), and prescription stimulant use disorder (21.8%, 95% CI, 11.0%–38.7%).

Conclusions:

Moderate-to-severe POUD is more frequent among adults who report misusing prescription opioids. However, 62% of adults with POUD do not report prescription opioid misuse, suggesting that adults who are treated with prescription opioids and report no misuse could be at risk for developing POUD. Results highlight the need to screen for and treat POUD among adults taking prescription opioids regardless of whether they report prescription opioid misuse.

For more than a decade, researchers, policymakers, and clinicians have focused on reducing health harms associated with prescription opioids, especially overdose mortality.1–5 Although overdose deaths involving prescription opioids have stabilized since approximately 2012, they remain an important contributor to overdose mortality. In 2021, among the 80,411 US people who died from an opioid-involved overdose, 16,706 (20.7%) deaths involved prescription opioids.6

Prescription-related opioid use disorder (POUD) is defined as prescription opioid use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress,7 which has commonly been considered to impact a subset of people with prescription opioid misuse (ie, opioid use in any way not directed by a clinician).8–12 Thus, public health efforts and clinical attention have focused on prevention of and screening for opioid misuse to prevent POUD and other opioid-related harms.13–15 The rationale that POUD primarily affects people misusing prescription opioids has been reflected in National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) questionnaires, which, prior to 2021, asked about POUD symptoms only among respondents reporting prescription opioid misuse. Yet, prescription opioid use among persons not reporting misuse can also lead to POUD16–20 and overdose mortality. Studies have reported that as many as 25% of patients receiving long-term opioid therapy in primary care settings have POUD.17–21

In 2021, for the first time in its data collection history, the NSDUH assessed all respondents reporting prescription opioid use for POUD, regardless of whether misuse was reported. The 2021 NSDUH also asked all persons reporting prescription opioid use about receipt of any past-year substance use treatment for prescription opioid use problems.8 Thus, leveraging nationally representative 2021 NSDUH data, we examined POUD prevalence among US adults reporting prescription opioid use and whether and how POUD symptoms, severity, characteristics, and treatment varied among those reporting or not reporting prescription opioid misuse.

METHODS

Data Sources

Data were from individuals aged ≥18 years who participated in the 2021 NSDUH, providing nationally representative data on prescription opioid use, misuse, POUD, and any substance use treatment for prescription opioid use problems among US civilian, noninstitutionalized adult populations.8–12 The NSDUH data collection protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Research Triangle Institute International. The 2021 NSDUH used multimode (via in-person or web) data collection and covered residents of households and people in noninstitutional group quarters. Each participant provided verbal/online informed consent.11,12 Audio computer-assisted self-administered interviewing was used, providing respondents with a private, confidential way to record answers. Race/ethnicity was determined according to NSDUH respondents’ self-classification of racial/ethnic origin and identification based on classifications developed by the US Census Bureau. The weighted household screening response rate was 22.2%, and the weighted interview response rate for adults aged ≥18 years was 47.0%.8 This study used publicly available deidentified data and was deemed exempt from review by the National Institutes of Health IRB.

Measures

To assess prescription opioids, NSDUH questionnaire items used the simple term “prescription pain relievers” because “prescription opioids” might not be understood by respondents at a sixth-grade reading level.8 However, NSDUH questionnaires clearly asked participants to exclude over-the-counter pain relievers and applied prescription opioid images during survey interviews to prompt recall of specific prescription opioid use from 11 subtypes of prescription opioids: hydrocodone, oxycodone, tramadol, codeine, morphine, fentanyl, buprenorphine, oxymorphone, meperidine, hydromorphone, and methadone.8–12 Misuse of prescription medications is defined as “use in any way not directed by a doctor, including use without a prescription of one’s own; use in greater amounts, more often, or longer than told to take a drug; or use in any other way not directed by a doctor.”8–12

The 2021 NSDUH Methodological Report summarized that based on the 2021 NSDUH data, 84% of people with past-year use of prescription pain relievers used prescription opioids, 94% of people with past-year misuse of prescription pain relievers misused prescription opioids, and ≥92% of people with a past-year prescription pain reliever use disorder used prescription opioids.8,9 To enhance clarity throughout the rest of this article, the terms “prescription opioid use,” “prescription opioid misuse,” and “POUD” are used rather than prescription pain reliever use, misuse, and use disorder.

Using diagnostic criteria specified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5),7–10 NSDUH estimated past-year POUD and individual POUD symptoms among people with past-year prescription opioid use regardless of their prescription opioid misuse status. POUD severity is defined by the number of identified symptoms: mild (2–3 symptoms), moderate (4–5 symptoms), and severe (≥6 symptoms).7 As specified in DSM-5, tolerance and withdrawal are normal physiological adaptations that can occur when people take prescription opioids appropriately under medical supervision and should not be included in the DSM-5 diagnosis of POUD when taken as prescribed.8,16 Following these DSM-5 guidelines and related NSDUH definitions, for respondents reporting prescription opioid use without misuse, POUD was based on 9 DSM-5 criteria (excluding tolerance and withdrawal), and for those reporting misuse, POUD was based on all 11 DSM-5 criteria.8,16

NSDUH assessed prevalence of prescription stimulant, tranquilizer, and sedataive use, misuse, and use disorder, which were assessed similarly to opioid use, misuse, and POUD. Based on DSM-5 diagnostic criteria,7–10 NSDUH also assessed past-year major depressive episode (MDE) and alcohol and other specific drug use disorders. Among NSDUH respondents who reported past-month cigarette smoking, past-month nicotine dependence was assessed by the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale and the Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence criteria for dependence.8 NSDUH asked respondents about sociodemographic characteristics, health status (eg, self-rated health, the number of past-year emergency department visits, and diseases diagnosed by health professionals [eg, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes mellitus, cancer, asthma, COPD, and hepatitis B/C]), functional disabilities,22 and past-year suicidal ideation. Details about NSDUH methods and survey questionnaires are available.8–12 This study focused on people aged ≥18 years because many examined factors (eg, educational attainment, marital status, and employment status) were more relevant for adults and because NSDUH assessed certain factors (eg, suicidal ideation) among adults and youth differently.8

Statistical Analyses

We estimated POUD prevalence, individual POUD symptoms, and number of POUD symptoms by prescription opioid misuse status among US adults with past-year use of prescription opioids. Next, bivariable logistic regression analyses23 were conducted to estimate prevalence of POUD by sociodemographic characteristics, physical health conditions, functional disability, and behavioral health status within and across prescription opioid misuse status among adults with past-year use of prescription opioids. Finally, we estimated prevalence of receiving any substance use treatment for prescription opioid use problems by number of POUD symptoms and prescription opioid misuse status.

All analyses used SUDAAN software (Release 11.0.3)24 to account for NSDUH’s complex sample design and sample weights. The NSDUH weighting procedures adjusted for nonresponse through direct adjustments and an indirect adjustment via poststratification.25 For each analysis, P < .05 (2-tailed) was considered statistically significant. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for observational (cross-sectional) studies.

RESULTS

Prescription Opioid Use, Misuse, POUD, and POUD Severity

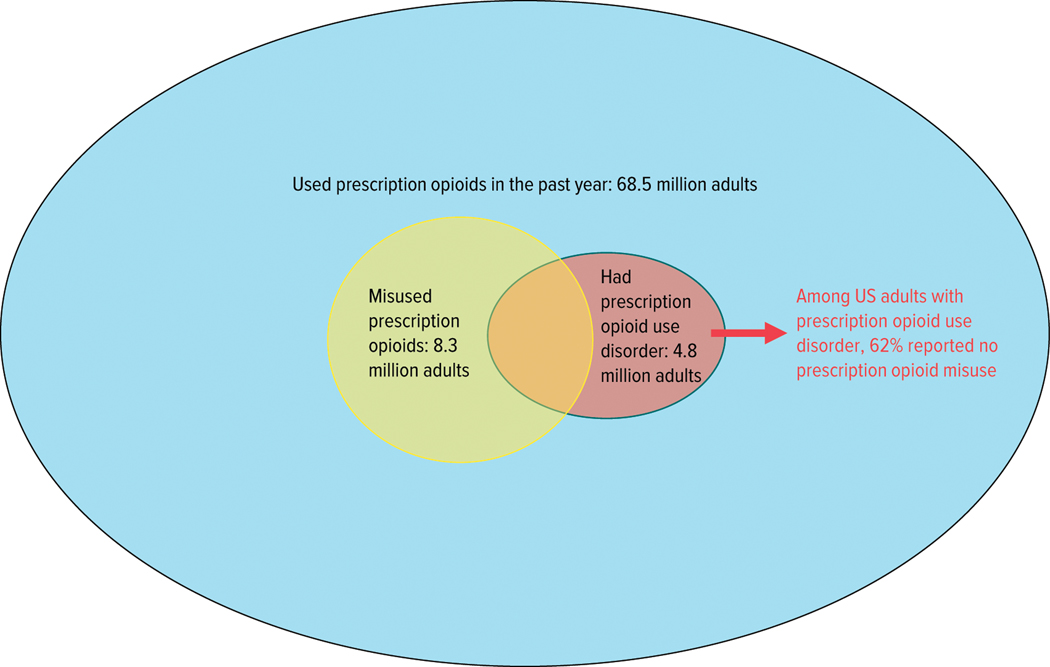

Among US adults aged ≥18 years in 2021 (n = 47,291), approximately 27.0% (95% CI, 26.3%–27.7%), or 68.5 million (95% CI, 65.3–71.7 million), used prescription opioids in the past year. Among adults with past-year prescription opioid use, approximately 12.1% (95% CI, 11.1%–13.1%), or 8.3 million (95% CI, 7.5–9.0 million), misused prescription opioids, and approximately 7.0% (95% CI, 6.2%–8.9%), or 4.8 million (95% CI, 4.2–5.3 million), had POUD (ie, with ≥2 DSM-5 symptoms) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Overlap of Prescription Opioid Misuse and POUD Among Adults 18 Years and Older With Prescription Opioid Use in the United States in the Past Yeara.

aData source: the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health data.

Abbreviation: POUD = prescription-related opioid use disorder.

For adults with past-year use of prescription opioids, prevalence of POUD was 4.5 times higher (prevalence ratio [PR] = 4.5, 95% CI, 3.6–5.6) among those reporting prescription opioid misuse (22.0%, 95% CI, 18.6%–25.8%) than those reporting use without misuse (4.9%, 95% CI, 4.2%–5.7%) (Table 1). For adults reporting use without misuse, to estimate potential contributions of excluding tolerance and withdrawal criteria from the POUD diagnosis to the POUD prevalence, we conducted ad hoc analyses that included these criteria and found higher prevalence of POUD (7.0%, 95% CI, 6.2%–8.0%) (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Past-Year Prevalence of POUD, Individual Symptoms, and the Number of Symptoms by Prescription Opioid Misuse Status Among US Adults With Past-Year Use of Prescription Opioids (N = 11,090)

| POUD based on DSM-5 criteria | Adults reporting Rx opioid misuse n = 1,556 wtd % (95% CI) | Adults reporting Rx opioid use without misusea n = 9,534 wtd % (95% CI) | Prevalence ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meeting ≥2 Rx OUD criteria | 22.0 (18.6–25.8) | 4.9 (4.2–5.7) | 4.5 (3.6–5.6) |

|

| |||

| Meeting a specific Rx OUD criterion | |||

| 1. Often taken in larger amounts, longer than intended | 11.9 (9.1–15.4) | 1.7 (1.3–2.2) | 7.1 (5.0–10.2) |

| 2. Unsuccessful efforts to cut down/control use | 12.3 (9.6–15.5) | 6.4 (5.5–7.4) | 1.9 (1.5–2.6) |

| 3. Spending a great deal of time obtaining, using, recovering | 12.4 (10.1–15.1 ) | 5.9 (5.0–7.0) | 2.1 (1.6–2.7) |

| 4. Craving/strong urge to use | 19.8 (16.2–23.9) | 6.2 (5.5–6.9) | 3.2 (2.6–4.0) |

| 5. Recurrent use resulting in failure to fulfill major role obligations at work/school/home | 7.0 (4.7–10.4) | 0.7 (0.5–1.0) | 10.1 (6.2–16.4) |

| 6. Continued use despite social problems | 6.0 (4.1–8.8) | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) | 11.1 (6.1–20.1 ) |

| 7. Important social, occupational, or recreational activities given up or reduced because of use | 8.6 (6.1–11.9) | 1.6 (1.1–2.2) | 5.5 (3.3–9.1 ) |

| 8. Recurrent use in physically hazardous situations | 4.6 (2.9–7.4) | 0.4 (0.3–0.7) | 11.2 (6.0–21.0) |

| 9. Continued use despite physical, psychological problems | 6.9 (4.9–9.6) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1 ) | 8.6 (2.1–5.2) |

| 10. Increased amount of substance needed to achieve same effect | 19.0 (15.6–23.0) | ||

| 11. Withdrawal symptoms or the same or related substance is taken to avoid withdrawal symptoms | 19.2 (15.8–23.2) | ||

|

| |||

| Number of Rx OUD symptoms | |||

| OUD: 0 symptomb | 60.2 (55.4–64.9) | 84.3 (82.9–85.6) | 0.7 (0.7–0.8) |

| OUD: 1 symptomb | 17.7 (13.6–22.7) | 10.9 (9.8–12.0) | 1.6 (1.2–2.2) |

| OUD: 2 symptomsb | 5.8 (3.9–8.7) | 2.9 (2.4–3.6) | 2.0 (1.2–3.3) |

| OUD: 3 symptomsb | 3.1 (2.1–4.6) | 1.0 (0.6–1.4) | 3.2 (1.9–5.5) |

| OUD: 4 symptomsb | 3.0 (1.9–4.9) | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) | 5.7 (2.8–11.7) |

| OUD: 5 symptomsb | 2.4 (1.5–3.8) | 0.3 (0.2–0.6) | 7.8 (3.3–18.1 ) |

| OUD: ≥6 symptoms | 7.7 (5.5–10.7) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 50.9 (24.5–105.8) |

For those without prescription opioid misuse, POUD is based on 9 DSM-5 criteria (without counting withdrawal and tolerance).

Analyses were limited to respondents without missing data on Rx OUD symptoms.

Abbreviations: OUD = opioid use disorder, POUD = prescription-related opioid use disorder, Rx = prescription, wtd = weighted.

Prevalence of being subthreshold for POUD (ie, only 1 DSM-5 symptom reported) was 1.6 times higher (PR = 1.6, 95% CI, 1.2–2.2) among those reporting prescription opioid misuse (17.7%, 95% CI, 13.6%–22.7%) than those reporting use without misuse (10.9%, 95% CI, 9.8%–12.0%) (Table 1). Prevalence of severe POUD was 50.9 times higher (PR = 50.9, 95% CI, 24.5–105.8) among those reporting prescription opioid misuse (7.7%, 95% CI, 5.5%–10.7%) than those reporting use without misuse (0.2%, 95% CI, 0.1%–0.3%). Severe POUD was substantially more prevalent among adults with misuse (PR = 12.5, 95% CI, 7.3–21.4) even when tolerance and withdrawal symptoms were considered for those reporting use without misuse (severe POUD: 0.6%, 95% CI, 0.5%–1.0%, Supplementary Table 1).

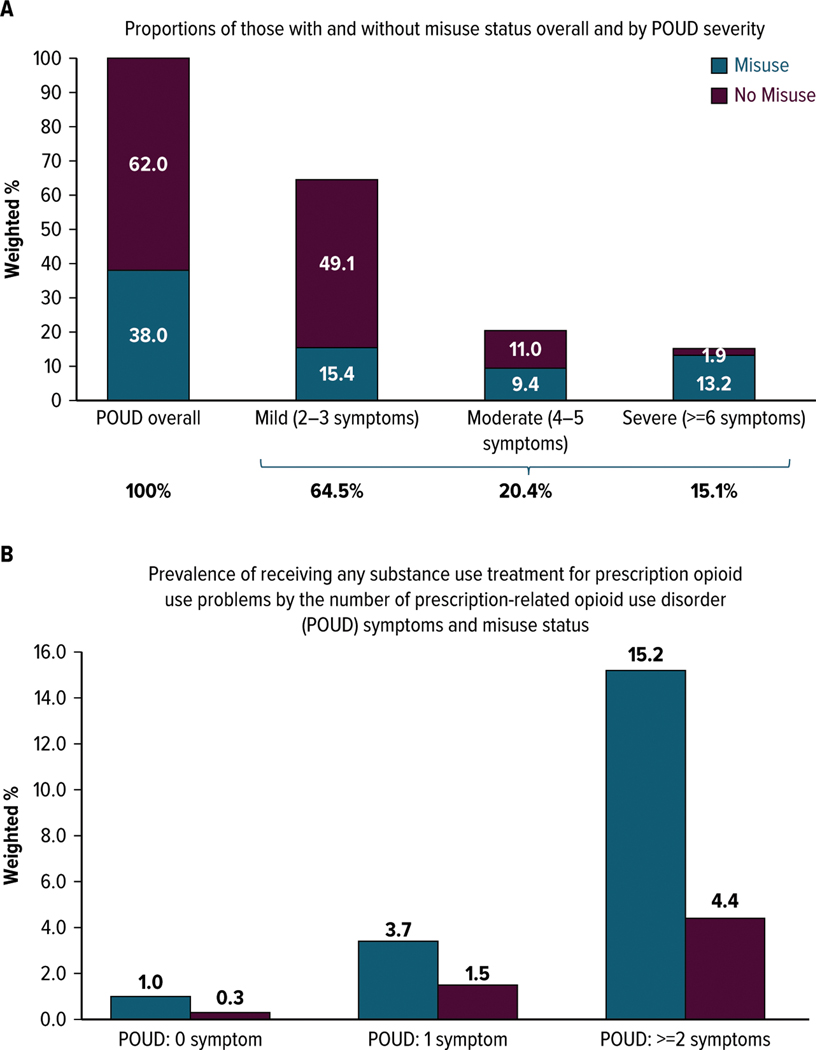

Among adults with past-year prescription opioid use and POUD (Figure 1 and Figure 2A), 62.0% (95% CI, 56.7%–67.2%) reported no prescription opioid misuse, including 49.1% (95% CI, 43.5%–54.7%) with mild POUD, 11.0% (95% CI, 6.5%–15.4%) with moderate POUD, and 1.9% (95% CI, 0.6%–3.2%) with severe POUD. Among adults with prescription opioid use and POUD, 38.0% (95% CI, 32.8%–43.3%) misused prescription opioids, including 15.4% (95% CI, 11.4–19.3) with mild POUD, 9.4% (95% CI, 6.5%–12.3%) with moderate POUD, and 13.2% (95% CI, 8.8%–17.7%) with severe POUD.

Figure 2. Among US Adults With POUD: (A) Proportions of Those With and Without Misuse Overall and by POUD Severity and (B) Prevalence of Receiving Substance Use Treatment for Prescription Opioid Use Problems by the Number of POUD Symptoms and Misuse Status.

Abbreviation: POUD = prescription-related opioid use disorder.

Prevalence of POUD Individual Symptoms and Severity by Prescription Opioid Misuse Status

Among adults with prescription opioid use, all POUD DSM-5 symptoms were more prevalent among persons reporting misuse compared to those reporting use without misuse (Table 1). The following POUD symptoms were relatively common among adults with and without prescription opioid misuse: Prevalence of unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control use was 1.9 times higher (PR = 1.9, 95% CI, 1.5–2.6) among those reporting prescription opioid misuse (12.3%, 95% CI, 9.6%–15.5%) than those reporting use without misuse (6.4%, 95% CI, 5.5%–7.4%), and prevalence of spending a great deal of time obtaining, using, or recovering was 2.1 times higher (PR = 2.1, 95% CI, 1.6–2.7) among those reporting prescription opioid misuse (12.4%, 95% CI, 10.1%–15.1%) than those reporting use without misuse (5.9%, 95% CI, 5.0%–7.0%).

Adults with prescription opioid misuse tended to report POUD symptoms related to functional impairments more frequently than did adults reporting use without misuse. Prevalence of recurrent use resulting in failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home was 10.1 times higher (PR = 10.1, 95% CI, 6.2–16.4) among those reporting prescription opioid misuse (7.0%, 95% CI, 4.7%–10.4%) than those reporting use without misuse (0.7%, 95% CI, 0.5%–1.0%). Prevalence of continued use despite social problems was 11.1 times higher (PR = 11.1, 95% CI, 6.1–20.1) among those reporting prescription opioid misuse (6.0%, 95% CI, 4.1%–8.8%) than those reporting use without misuse (0.5%, 95% CI, 0.3%–0.9%). Prevalence of recurrent use in physically hazardous situations was 11.2 times higher (PR = 11.2, 95% CI, 6.0–21.0) among those reporting prescription opioid misuse (4.6%, 95% CI, 2.9%–7.4%) than those reporting use without misuse (0.4%, 95% CI, 0.3%–0.7%).

POUD Prevalence by Sociodemographic Characteristics Within and Across Prescription Opioid Misuse Status

Within each category of examined sociodemographic characteristics, past-year POUD prevalence was 2.5–7.3 times higher (PRs = 2.5–7.3, 95% CIs, 1.4–12.1) among those reporting prescription opioid misuse than those reporting use without misuse (Table 2). Among persons who reported prescription opioid use without misuse, higher POUD prevalence was found among those aged ≥50 years (5.3%, 95% CI, 4.3%–6.7%) than adults aged 18–29 years (3.2%, 95% CI, 2.1%–4.9%), Medicaid beneficiaries (7.3%, 95% CI, 5.7%–9.4%) than privately insured adults (3.1%, 95% CI, 2.2%–4.3%), and disabled (13.8%, 95% CI, 10.1%–18.5%), unemployed, or part-time employed adults (4.8%–5.3%, 95% CIs, 2.9%–8.7%) than full-time employed adults (2.9%, 95% CI, 2.1%–3.9%).

Table 2.

Prevalence of POUD by Sociodemographic Characteristics Within and Across Prescription Opioid Misuse Status Among US Adults With Past-Year Use of Prescription Opioids

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Adults reporting Rx opioid misuse n = 1,556 wtd % (95% CI) | Adults reporting Rx opioiduse without misuse n = 9,534 wtd % (95% CI) | Prevalence ratioa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 22.0 (18.6–25.8) | 4.9 (4.2–5.7) | 4.5 (3.6–5.6) |

|

| |||

| Age | |||

| 18–29 y | 23.4 (18.0–29.8) | 3.2 (2.1–4.9) | 7.3 (4.4–12.1) |

| 30–49 y | 22.3 (18.2–27.1) | 4.9 (4.2–5.7) | 4.6 (3.5–5.8) |

| ≥50 yb | 20.9 (14.6–29.0) | 5.3 (4.3–6.7) | 3.9 (2.6–5.9) |

|

| |||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 21.6 (16.3–28.1) | 5.1 (4.1–6.4) | 4.2 (3.0–6.0) |

| Femaleb | 22.4 (18.5–26.9) | 4.7 (3.9–5.8) | 4.7 (3.6–6.2) |

|

| |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 28.7 (19.1–40.6) | 5.0 (3.4–7.4) | 5.7 (3.3–10.1) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 29.9 (19.9–42.3) | 5.0 (3.5–7.1) | 6.0 (3.7–9.8) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 19.5(9.8–35.3) | 3.7 (2.3–5.9) | 5.3 (3.0–9.4) |

| Non-Hispanic whiteb | 18.9 (15.1–23.3) | 5.0 (4.1–6.1) | 3.8 (2.8–5.1) |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| <High school | 31.4(20.8–44.2) | 5.1 (3.5–7.3) | 6.1 (3.7–10.1) |

| High school | 27.7 (19.6–37.6) | 5.5 (4.1–7.3) | 5.1 (3.1–8.3) |

| Some college/associate degree | 17.8 (12.1–25.3) | 5.3 (4.1–7.0) | 3.3 (2.2–5.0) |

| College graduateb | 12.3 (7.9–18.8) | 3.7 (2.5–5.3) | 3.3 (2.0–5.6) |

|

| |||

| Health insurance | |||

| Private onlyb | 15.5 (11.4–20.6) | 3.1 (2.2–4.3) | 5.0 (3.1–8.1) |

| Uninsured | 15.3 (9.8–23.2) | 5.2 (2.8–9.4) | 2.9 (1.4–6.2) |

| Medicaid | 37.4 (29.2–46.3) | 7.3 (5.7–9.4) | 5.1 (3.7–7.1) |

| Other | 13.6 (9.0–20.2) | 5.5 (4.0–7.4) | 2.5 (1.5–4.1) |

|

| |||

| Marital status | |||

| Marriedb | 13.0 (9.2–18.0) | 4.6 (3.5–5.9) | 2.8 (1.9–4.2) |

| Widowed | 21.3 (7.8–46.3) | 7.1 (4.1–12.2) | 3.0 (1.1–8.1) |

| Divorced/separated | 29.1 (18.8–42.0) | 5.3 (3.8–7.3) | 5.5 (3.2–9.4) |

| Never married | 26.1 (21.5–31.4) | 4.7 (3.3–6.5) | 5.6 (3.8–8.2) |

|

| |||

| Employment status | |||

| Full-timeb | 17.0 (13.4–21.4) | 2.9 (2.1–3.9) | 5.9 (4.0–8.8) |

| Part-time | 23.2 (14.7–34.5) | 4.8 (2.9–7.6) | 4.9 (2.6–9.1) |

| Unemployed | 26.6 (16.7–39.5) | 5.3 (3.2–8.7) | 5.0 (2.5–10.1) |

| Disabled | 36.2 (23.7–50.9) | 13.8 (10.1–18.5) | 2.6 (1.5–4.6) |

| Other | 20.5 (13.9–29.2) | 4.4 (3.3–6.0) | 4.6 (2.8–7.6) |

|

| |||

| Family income | |||

| <$20,000 | 33.3 (25.0–42.8) | 7.6 (5.7–10.0) | 4.4 (2.9–6.7) |

| $20,000–$49,999 | 22.6 (17.5–28.8) | 4.4 (3.4–5.8) | 5.1 (3.6–7.3) |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 18.8 (10.1–32.3) | 6.2 (3.9–9.6) | 3.0 (1.4–6.6) |

| ≥$75,000b | 12.1 (8.1–17.9) | 3.3 (2.4–4.5) | 3.7 (2.2–6.2) |

|

| |||

| Metropolitan statistical area | |||

| Largeb | 22.3 (17.3–28.1) | 4.6 (3.7–5.7) | 4.9 (3.5–6.8) |

| Small | 25.5 (17.8–35.1) | 6.1 (4.3–8.5) | 4.2 (2.7–6.6) |

| Nonmetropolitan | 20.0 (14.9–26.3) | 4.9 (3.8–6.2) | 4.1 (2.8–6.0) |

For each prevalence ratio, the reference group is the group of adults reporting Rx opioid use without misuse.

Within each group, bolded estimates were statistically significantly different from the corresponding estimate from the reference group (reference groups indicated with superscript b) (P < .05).

Abbreviations: Rx = prescription, wtd = weighted.

POUD Prevalence by Physical Health Conditions, Disability, and Behavioral Health Status Within and Across Prescription Opioid Misuse Status

Within almost every examined category of physical health conditions, functional disability, and behavioral health status, past-year POUD prevalence was 1.9–35.0 times higher (PRs = 1.9–35.0, 95% CIs, 1.1–290.8) among adults reporting vs not reporting prescription opioid misuse (Table 3). Among persons who reported prescription opioid use without misuse, higher POUD prevalence was found among adults reporting fair/poor self-rated health (10.6%, 95% CI, 8.7%–12.8%), ≥3 emergency department visits (16.4%, 95% CI, 11.5%–23.0%), COPD diagnosis (10.7%, 95% CI, 7.0%–15.9%), hepatitis B or C diagnosis (12.8%, 95% CI, 6.5%–23.7%), self-care disability (13.6%, 95% CI, 10.4%–17.7%), ≥4 disabilities (14.2%, 95% CI, 10.8%–18.4%), MDE (12.0%, 95% CI, 9.3%–15.3%), suicidal ideation (10.9%, 95% CI, 7.0%–16.6%), heroin use or use disorder (17.1%, 95% CI, 5.2%–43.8%), prescription sedative/tranquilizer use disorder (36.2%, 95% CI, 23.6%–51.1%), and prescription stimulant use disorder (21.8%, 95% CI, 11.0%–38.7%), each compared to their corresponding reference group.

Table 3.

Prevalence of POUD by Health Conditions, Functional Disabilities, and Behavioral Health Status Within and Across Prescription Opioid Misuse Status Among US Adults With Past-Year Use of Prescription Opioids

| Health conditions, functional disabilities, and behavioral health status | Adults reporting Rx opioid misuse n = 1,556 wtd % (95% CI) | Adults reporting Rx opioid use without misuse n = 9,534 wtd % (95% CI) | Prevalence ratioa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health conditions | |||

|

| |||

| Self-rated health | |||

| Excellentb | 9.1 (5.0–15.9) | 2.3 (1.1–4.6) | 4.0 (1.6–10.0) |

| Very good | 12.0 (8.0–17.5) | 2.7 (1.8–4.0) | 4.5 (2.5–8.1) |

| Good | 26.2 (20.5–32.8) | 3.6 (2.8–4.6) | 7.3 (5.2–10.4) |

| Fair/poor | 33.5 (23.8–44.8) | 10.6 (8.7–12.8) | 3.2 (2.3–4.4) |

|

| |||

| PY emergency department visit | |||

| 0b | 18.1 (14.4–22.6) | 3.6 (2.9–4.6) | 5.0 (3.6–6.8) |

| 1–2 | 27.8 (20.9–36.0) | 4.3 (3.2–5.8) | 6.5 (4.2–9.9) |

| ≥3 | 32.0 (20.4–46.4) | 16.4 (11.5–23.0) | 1.9 (1.1–3.5) |

|

| |||

| Hypertension | |||

| Yes | 26.8 (18.8–36.6) | 6.8 (5.3–8.8) | 3.9 (2.6–5.9) |

| Nob | 20.6 (17.1–24.6) | 4.0 (3.4–4.9) | 5.1 (3.9–6.7) |

|

| |||

| Heart disease | |||

| Yes | 38.5 (25.4–53.5) | 8.3 (5.6–12.1) | 4.6 (2.7–7.9) |

| Nob | 19.7 (16.4–23.4) | 4.1 (3.4–5.0) | 4.8 (3.7–6.2) |

|

| |||

| Diabetes mellitus | |||

| Yes | 26.2 (15.7–40.5) | 8.2(5.9–11.3) | 3.2 (1.8–5.7) |

| Nob | 21.2 (17.7–25.2) | 4.1 (3.3–5.1) | 5.1 (3.9–6.7) |

|

| |||

| Cancer | |||

| Yes | c | 7.1 (4.4–11.3) | c |

| Nob | 22.5 (19.1–26.2) | 4.5 (3.9–5.3) | 4.9 (3.9–6.3) |

|

| |||

| Asthma | |||

| Yes | 24.9 (16.2–36.3) | 7.0 (4.7–10.2) | 3.6 (2.1–6.1) |

| Nob | 21.2 (17.7–25.2) | 4.5 (3.7–5.3) | 4.7 (3.7–6.2) |

|

| |||

| COPD | |||

| Yes | c | 10.7 (7.0–15.9) | c |

| Nob | 21.0 (17.8–24.5) | 4.2 (3.6–5.0) | 5.0 (3.9–6.3) |

|

| |||

| Hepatitis B or C | |||

| Yes | c | 12.8 (6.5–23.7) | c |

| Nob | 21.4 (18.0–25.1) | 4.6 (3.9–5.4) | 4.6 (3.6–6.0) |

| Functional disabilities | |||

| Hearing disability | |||

| Yes | 22.0 (16.6–28.4) | 7.0 (5.3–9.3) | 3.1 (2.0–4.8) |

| Nob | 22.2 (18.2–26.8) | 4.2 (3.5–5.0) | 5.3 (4.0–7.0) |

|

| |||

| Vision disability | |||

| Yes | 25.9 (19.8–33.2) | 8.0 (6.4–9.9) | 3.3 (2.3–4.7) |

| Nob | 19.3 (15.8–23.3) | 3.2 (2.6–4.1) | 6.0(4.3–8.2) |

|

| |||

| Cognition disability | |||

| Yes | 27.5 (22.2–33.5) | 8.0 (6.5–9.8) | 3.4 (2.6–4.6) |

| Nob | 16.6 (12.6–21.4) | 2.8 (2.2–3.5) | 6.0 (4.1–8.7) |

|

| |||

| Mobility disability | |||

| Yes | 34.5 (24.9–45.5) | 8.9 (7.4–10.7 | 3.9 (2.9–5.2) |

| Nob | 17.1 (13.6–21.2) | 2.8 (2.0–3.8) | 6.2 (4.1–9.1) |

|

| |||

| Communication disability | |||

| Yes | 37.5 (28.4–47.5) | 11.3 (8.5–14.7) | 3.3 (2.3–4.9) |

| Nob | 19.5 (15.7–23.9) | 4.2 (3.5–5.0) | 4.7 (3.5–6.3) |

|

| |||

| Self-care disability | |||

| Yes | 37.7 (27.0–49.7) | 13.6 (10.4–17.7) | 2.8 (1.9–3.9) |

| Nob | 19.1 (15.3–23.5) | 3.9 (3.1–4.8) | 4.9 (3.6–6.8) |

|

| |||

| Sum of disabilities | |||

| 0b | 14.5 (10.5–19.6) | 1.5 (1.0–2.4) | 9.4 (5.4–16.3) |

| 1 | 15.4 (10.4–22.2) | 4.2 (2.9–6.0) | 3.7 (2.3–6.0) |

| 2 | 28.1 (20.4–37.4) | 4.2 (2.6–6.7) | 6.7 (3.5–13.0) |

| 3 | 23.3 (14.9–34.6) | 7.3 (4.9–10.8) | 3.2 (1.8–5.8) |

| ≥4 | 39.3 (28.6–51.1) | 14.2 (10.8–18.4) | 2.8 (1.9–4.0) |

| Mental health problems | |||

| PY MDE | |||

| Yes | 33.9 (24.7–44.5) | 12.0 (9.3–15.3) | 2.8 (2.0–4.1) |

| Nob | 18.3 (14.5–22.9) | 4.0 (3.3–4.9) | 4.6 (3.3–6.3) |

|

| |||

| PY suicidal ideation | |||

| Yes | 34.4 (23.8–46.8) | 10.9 (7.0–16.6) | 3.2 (1.8–5.5) |

| Nob | 20.3 (16.7–24.5) | 4.6 (3.8–5.5) | 4.4 (3.4–5.7) |

| Substance use problems | |||

| PM nicotine dependence | |||

| Yes | 38.7 (30.7–47.3) | 9.4 (7.3–12.0) | 4.1 (2.9–5.7) |

| Nob | 15.5 (12.7–18.7) | 4.1 (3.3–5.0) | 3.8 (2.9–5.0) |

|

| |||

| PY alcohol use and disorder | |||

| Use disorder | 26.4 (20.6–33.0) | 6.0 (4.3–8.5) | 4.4 (2.9–6.5) |

| Use, no disorder | 15.6 (11.7–20.5) | 2.8 (2.1–3.6) | 5.6 (4.0–8.0) |

| useb | 29.7 (21.4–39.7) | 8.4 (6.6–10.6) | 3.5 (2.4–5.2) |

|

| |||

| PY cannabis use and disorder | |||

| Use disorder | 27.8 (20.2–37.0) | 8.6 (4.8–15.1) | 3.2 (1.7–6.0) |

| Use, no disorder | 17.6 (12.1–25.0) | 4.2 (2.9–6.2) | 4.2 (2.5–7.1) |

| No useb | 22.0 (16.7–28.3) | 4.8 (4.0–5.8) | 4.6 (3.4–6.3) |

|

| |||

| PY cocaine use and disorder | |||

| Use or use disorder | 45.5 (33.1–58.4) | 9.0 (3.6–20.9) | 5.0 (2.0–12.8) |

| No useb | 18.2 (15.1–21.8) | 4.8 (4.1–5.7) | 3.8 (2.9–4.9) |

|

| |||

| PY heroin use and disorder | |||

| Use or use disorder | 69.5 (53.6–81.8) | 17.1 (5.2–43.8) | 4.1 (1.3–12.5) |

| No useb | 18.5 (15.5–21.9) | 4.9 (4.2–5.7) | 3.8 (3.0–4.8) |

|

| |||

| PY Rx sedative/tranquilizer use, misuse, or use disorder | |||

| Use disorder | 82.8 (71.2–90.4) | 36.2 (23.6–51.1) | 2.3 (1.5–3.4) |

| Misuse, no disorder | 18.3 (11.3–28.3) | 14.6 (5.9–31.7) | 1.3 (0.4–3.6) |

| Use, no misuse, no disorder | 19.8 (13.4–28.2) | 6.1 (4.7–8.0) | 3.2 (2.0–5.2) |

| No useb | 14.9 (11.0–19.8) | 3.7 (3.0–4.5) | 4.1 (2.9–5.7) |

|

| |||

| PY Rx stimulant use, misuse, or use disorder | |||

| Use disorder | 76.5 (65.5–84.8) | 21.8 (11.0–38.7) | 3.5 (1.8–6.7) |

| Misuse, no disorder | 22.2 (13.8–33.8) | 00.6 (0.1–4.8) | 35.0 (4.2–290.8) |

| Use, no misuse, no disorder | 15.3 (8.5–26.1) | 4.5 (2.7–7.6) | 3.4 (1.8–6.5) |

| No useb | 20.4 (16.4–25.1) | 4.9 (4.1–5.8) | 4.2 (3.2–5.5) |

For each prevalence ratio, the reference group is the group of adults reporting Rx opioid use without misuse.

Within each group, bolded estimates were statistically significantly different from the corresponding estimate from the reference group indicated with superscript b (P < .05).

Estimate suppressed due to low statistical precision.

Abbreviations: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, MDE = major depressive episode, PM = past-month, POUD = prescription-related opioid use disorder, PY = past-year, Rx = prescription, wtd = weighted.

Prevalence of Substance Use Treatment for Prescription Opioid Use Problems

Among US adults with past-year use of prescription opioids (Figure 2B, Supplementary Table 2), prevalence of receiving any substance use treatment for prescription opioid use problems did not significantly differ between those reporting prescription opioid misuse with one POUD symptom (3.7%, 95% CI, 1.2%–11.0%) and their counterparts reporting use without misuse (1.5%, 95% CI, 0.6%–3.4%). Prevalence of receiving any substance use treatment for prescription opioid use problems was 3.5 times higher (PR = 3.5, 95% CI, 1.4–8.5) among adults reporting prescription opioid misuse with ≥2 POUD symptoms (15.2%, 95% CI, 9.9%–22.9%) than their counterparts reporting no misuse (4.4%, 95% CI, 1.9%–9.6%).

DISCUSSION

Although adults reporting prescription opioid misuse are more likely to report POUD symptoms than those reporting use without misuse, we found that most US adults with POUD do not report misuse of prescription opioids. Specifically, among an estimated 4.8 million adults with past-year POUD in 2021, 62% (or 3.0 million adults) reported no misuse of prescription opioids, and only 38% (or 1.8 million adults) reported misusing prescription opioids. Furthermore, among adults with moderate or severe POUD, for whom medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) are strongly recommended,4 36% reported no prescription opioid misuse. Our results suggest that adults who have untreated POUD and could benefit from treatment might be overlooked if they do not report that they are misusing their prescribed opioids or if their clinicians consider prescription opioid misuse to be a necessary premise for POUD. Consistent with the recommendations from the 2022 CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain,4 our results highlight the need to screen for and treat POUD among adults with prescription opioid use, regardless of whether they report prescription opioid misuse or not. This should be done in the context of a comprehensive patient-centered assessment and development of a treatment plan that addresses underlying pain conditions and any co-occurring substance use or mental health challenges.

Due to decreases in opioid prescribing and increases in the use of prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs)26 and efforts on prevention of and screening for opioid misuse,13–15 overdose deaths involving “natural and semi-synthetic opioids” (ie the majority of prescription opioid-involved overdose deaths) in the United States declined from 14,487 in 2016 to 13,618 in 2021 and 11,871 in 2022.27 Yet, when harm-reduction efforts focus primarily on reducing prescription opioid misuse and harms associated with misuse, large numbers of adults with POUD and at risk for associated health consequences, including opioid overdose, might be overlooked, missing critical opportunities for timely prevention and treatment. For example, among adults reporting opioid use without misuse in our study, we identified high prevalence of POUD among those with multiple emergency department visits, MDE, and co-occurring substance use, including heroin use or use disorder, prescription sedative/tranquilizer use disorder, and prescription stimulant use disorder. Our results suggest that distribution of naloxone is warranted among adults with prescription opioid use and at risk for POUD and/or overdose, regardless of reported misuse status.

MOUD are the most effective treatments for moderate-to-severe opioid use disorder (OUD), yet an overwhelming majority of people who could benefit from these medications do not receive them.28–31 Regardless of self-reported prescription opioid misuse status, to reduce harms associated with prescription opioid use, people with POUD need to receive timely interventions. Further research is needed to advance clinical POUD screening and the provision of treatment, in particular, MOUD, among patients using prescription opioids, whether misuse is reported or not.

POUD estimates in the 2021 NSDUH included, for the first time, data from all persons reporting past-year use of prescription opioids. Due to this change in 2021 and other methodologic changes in 2020–2021, POUD estimates from 2021 cannot be compared with previous POUD estimates. POUD was assessed by DSM-IV criteria in 201928 and earlier NSDUH surveys but was assessed by DSM-5 criteria beginning in 2020.32 Estimates in the years preceding these methodologic changes indicated that past-year POUD among US adults had been declining from 1.9 million adults in 2015 to 1.3 million in 2019.28 While our finding that an estimated 4.8 million adults had past-year POUD in 2021 seems to indicate a much larger population size of adults with POUD, we also found that in 2021, 3.0 million people with POUD reported no prescription opioid misuse and would not have been considered in prior NSDUH estimates for the population size of US adults with POUD.

Our results suggest that the estimated number of US adults with POUD varies dramatically, even when using the same DSM-5 criteria, depending on the population included (ie, focusing on adults reporting prescription opioid misuse vs adults reporting prescription opioid use without misuse). Although a larger percentage of those with past-year POUD reported no opioid misuse in the past year compared to the percentage reporting misuse, our results also identify how opioid misuse is associated with POUD overall, POUD severity, and POUD functional impairment.

In excluding people taking prescription opioids without reporting prescription opioid misuse, previous assessments may have substantially underestimated the population size of US adults with POUD. Moreover, potentially due to the social stigma associated with opioid misuse,33 some people taking their own prescribed opioids for pain might not consider themselves to be misusing opioids even if they are not taking opioids exactly as prescribed, resulting in being misclassified as using opioids without misuse. Our results also indicate that self-perceived prescription opioid misuse is not well suited to identifying problematic use behaviors. Findings provide critical new information and insight for policymakers to help ensure that resources to develop and implement prevention, treatment, recovery, and harm reduction approaches to address POUD among US adults are based on the full magnitude and varied dimensions of this challenge. Clinicians need to screen for and treat POUD regardless of patients’ prescription opioid misuse status.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of NSDUH data precludes drawing causal relationships. Second, this study may underestimate prevalence of POUD because NSDUH excluded people experiencing homelessness not living in shelters and institutionalized populations (eg, jail/prison populations), who often have higher POUD than the general population.34 Third, NSDUH is a self-report survey and is subject to recall and social-desirability bias. Future research is needed to examine whether the absence of functional impairment symptoms could be a reason why many people with POUD report prescription opioid use but without misuse. Research is also needed to examine POUD among youth reporting prescription opioid use with or without misuse in the United States. Finally, we cannot examine specific prescription opioids used and misused in the past year because the 2021 NSDUH public use files do not include the information.

CONCLUSIONS

Although misuse of prescription opioids remains a significant risk factor for potential harm, our results show that POUD is prevalent and can lead to harm among adults with prescription opioid use without misuse. Notably, among US adults with past-year POUD, only 38% reported prescription opioid misuse, and 62% reported use without misuse. Even among persons with moderate or severe POUD, 36% did not report misuse, but they are prime candidates for MOUD and other measures such as naloxone to reduce the risk for opioid-related harms. Our results highlight the need for clinicians to screen for and treat POUD in adults taking prescription opioids, including those who report use without misuse of their medications.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Points.

Public health efforts and clinical attention have focused on prevention of and screening for opioid misuse to prevent prescription-related opioid use disorder (POUD) and other opioid-related harms. However, 62% of adults with POUD do not report prescription opioid misuse.

Clinicians should screen for and treat POUD among adults taking prescription opioids regardless of their prescription opioid misuse status.

Disclaimer:

The findings and conclusions of this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Relevant Financial Relationships: Dr Compton reports ownership of stock (unrelated to the submitted work) in General Electric Co, 3M Co, and Pfizer Inc. The remaining authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Supplementary Material: Available at Psychiatrist.com.

References

- 1.Han B, Compton WM, Jones CM, et al. Nonmedical prescription opioid use and use disorders among adults aged 18 through 64 years in the United States, 2003–2013. JAMA. 2015;314(14):1468–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription–opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(2):154–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, et al. Prescription opioid use, misuse, and use disorders in U.S. adults: 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(5):293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, et al. CDC clinical Practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain – United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022; 71(3):1–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs). Accessed June 27, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/overdose-prevention/php/interventions/prescription-drug-monitoring-programs.html#:∼:text=A%20prescription%20drug%20monitoring%20program,a%20nimble%20and%20targeted%20response.

- 6.National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug overdose death rates. Accessed April 26, 2023. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates.

- 7.American Psychiatry Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5TM. 5th ed. American Psychiatry Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP22–07-01–005, NSDUH Series H-57). Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2021 methodological summary and definitions. Accessed April 26, 2023. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2021-methodological-summary-and-definitions

- 10.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). Accessed April 26, 2023. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health [PubMed]

- 11.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): Final Screener Specifications for Programming. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): field interviewer manual & field interviewer computer manual. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolodny A, Courtwright DT, Hwang CS, et al. The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: a public health approach to an epidemic of addiction. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:559–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez KC, et al. Development and validation of the current opioid misuse measure. Pain. 2007;130(1–2):144–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nuckols TK, Anderson L, Popescu I, et al. Opioid prescribing: a systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines for chronic pain. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(1): 38–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasin DS, O’Brien CP, Auriacombe M, et al. DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: recommendations and rationale. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(8): 834–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banta-Green CJ, Merrill JO, Doyle SR, et al. Opioid use behaviors, mental health and pain—development of a typology of chronic pain patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104(1–2):34–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boscarino JA, Rukstalis M, Hotfman SN, et al. Risk factors for drug dependence among out–patients on opioid therapy in a large US health-care system. Addiction. 2010;105(10):1776–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleming MF, Balousek SL, Klessig CL, et al. Substance use disorders in a primary care sample receiving daily opioid therapy. J Pain. 2007;8(7):573–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boscarino JA, Withey CA, Dugan RJ, et al. Opioid medication use among chronic non-cancer pain patients assessed with a modified drug effects questionnaire and the association with opioid use disorder. J Pain Res. 2020;13:2697–2705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Von Korff M, Walker RL, Saunders K, et al. Prevalence of prescription opioid use disorder among chronic opioid therapy patients after health plan opioid dose and risk reduction initiatives. Int J Drug Pol. 2017;46:90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Washington Group on Disability Statistics. Wash Group Short Set Funct (WG-SS). Accessed April 26, 2023. https://www.washingtongroup-disability.com

- 23.Bieler GS, Brown GG, Williams RL, et al. Estimating model-adjusted risks, risk differences, and risk ratios from complex survey data. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171: 618–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN [computer program]. Release 11.0.3. RTI International; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): Methodological Resource Book, Section 11, Person-Level Sampling Weight Calibration. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 26.The American Medical Association. 2021 overdose epidemic report: Physicians’ actions to help end the nation’s drug-related overdose and death epidemic-and what still needs to be done. Accessed March 17, 2024.

- 27.Spencer MR, Garnett MF, Miniño AM. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 2002–2022. NCHS Data Brief, no 491. National Center for Health Statistics; 2024. Accessed March 22, 2024. 10.15620/cdc:135849 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han B. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP20–07-01–001, NSDUH Series H-55). Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han B, Jones CM, Einstein EB, et al. Trends in and characteristics of buprenorphine misuse among adults in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10): e2129409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krawczyk N, Rivera BD, Jent V, et al. Has the treatment gap for opioid use disorder narrowed in the U.S.?: a yearly assessment from 2010 to 2019. Int J Drug Policy. 2022;110(1 ):103786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones CM, Han B, Baldwin GT, et al. Use of medication for opioid use disorder among adults with past-year opioid use disorder in the US, 2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(8):e2327488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. When did NSDUH make the change from DSM-IV to DSM-5 for assessing mental health and substance use disorder? Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2021. Accessed May 8, 2023. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/faq/concerns-about-trend-comparability/when-did-nsduh-make-change-dsm-iv-dsm-5-assessing-mental-health-and-substance-use-disorder. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braverman A, Lin T, Messmer S, et al. Survey of stigma across healthcare workers in an urban, academic medical center regarding perinatal patients using opioids. Am J Addict. 2023;32(5):510–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Compton WM, Dawson D, Dutfy SQ, et al. The etfect of inmate populations on estimates of DSM-IV alcohol and drug use disorders in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(4):473–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.