Abstract

Background

Audit and feedback is widely used as a strategy to improve professional practice either on its own or as a component of multifaceted quality improvement interventions. This is based on the belief that healthcare professionals are prompted to modify their practice when given performance feedback showing that their clinical practice is inconsistent with a desirable target. Despite its prevalence as a quality improvement strategy, there remains uncertainty regarding both the effectiveness of audit and feedback in improving healthcare practice and the characteristics of audit and feedback that lead to greater impact.

Objectives

To assess the effects of audit and feedback on the practice of healthcare professionals and patient outcomes and to examine factors that may explain variation in the effectiveness of audit and feedback.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2010, Issue 4, part of The Cochrane Library.www.thecochranelibrary.com, including the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group Specialised Register (searched 10 December 2010); MEDLINE, Ovid (1950 to November Week 3 2010) (searched 09 December 2010); EMBASE, Ovid (1980 to 2010 Week 48) (searched 09 December 2010); CINAHL, Ebsco (1981 to present) (searched 10 December 2010); Science Citation Index and Social Sciences Citation Index, ISI Web of Science (1975 to present) (searched 12‐15 September 2011).

Selection criteria

Randomised trials of audit and feedback (defined as a summary of clinical performance over a specified period of time) that reported objectively measured health professional practice or patient outcomes. In the case of multifaceted interventions, only trials in which audit and feedback was considered the core, essential aspect of at least one intervention arm were included.

Data collection and analysis

All data were abstracted by two independent review authors. For the primary outcome(s) in each study, we calculated the median absolute risk difference (RD) (adjusted for baseline performance) of compliance with desired practice compliance for dichotomous outcomes and the median percent change relative to the control group for continuous outcomes. Across studies the median effect size was weighted by number of health professionals involved in each study. We investigated the following factors as possible explanations for the variation in the effectiveness of interventions across comparisons: format of feedback, source of feedback, frequency of feedback, instructions for improvement, direction of change required, baseline performance, profession of recipient, and risk of bias within the trial itself. We also conducted exploratory analyses to assess the role of context and the targeted clinical behaviour. Quantitative (meta‐regression), visual, and qualitative analyses were undertaken to examine variation in effect size related to these factors.

Main results

We included and analysed 140 studies for this review. In the main analyses, a total of 108 comparisons from 70 studies compared any intervention in which audit and feedback was a core, essential component to usual care and evaluated effects on professional practice. After excluding studies at high risk of bias, there were 82 comparisons from 49 studies featuring dichotomous outcomes, and the weighted median adjusted RD was a 4.3% (interquartile range (IQR) 0.5% to 16%) absolute increase in healthcare professionals' compliance with desired practice. Across 26 comparisons from 21 studies with continuous outcomes, the weighted median adjusted percent change relative to control was 1.3% (IQR = 1.3% to 28.9%). For patient outcomes, the weighted median RD was ‐0.4% (IQR ‐1.3% to 1.6%) for 12 comparisons from six studies reporting dichotomous outcomes and the weighted median percentage change was 17% (IQR 1.5% to 17%) for eight comparisons from five studies reporting continuous outcomes. Multivariable meta‐regression indicated that feedback may be more effective when baseline performance is low, the source is a supervisor or colleague, it is provided more than once, it is delivered in both verbal and written formats, and when it includes both explicit targets and an action plan. In addition, the effect size varied based on the clinical behaviour targeted by the intervention.

Authors' conclusions

Audit and feedback generally leads to small but potentially important improvements in professional practice. The effectiveness of audit and feedback seems to depend on baseline performance and how the feedback is provided. Future studies of audit and feedback should directly compare different ways of providing feedback.

Keywords: Humans; Feedback, Psychological; Education, Medical, Continuing; Health Personnel; Health Personnel/standards; Health Services Research; Medical Audit; Medical Audit/standards; Outcome Assessment, Health Care; Practice Patterns, Physicians'; Practice Patterns, Physicians'/standards; Professional Practice; Professional Practice/standards; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and patient outcomes

Researchers in The Cochrane Collaboration conducted a review to evaluate the effect of audit and feedback on the behaviour of health professionals and the health of their patients. After searching for all relevant studies, they found 140 studies that met their requirements. Their findings are summarised below.

The use of audit and feedback to influence health professional behaviour and patient health

In an audit and feedback process, an individual’s professional practice or performance is measured and then compared to professional standards or targets. In other words, their professional performance is “audited”. The results of this comparison are then fed back to the individual. The aim of this process is to encourage the individual to follow professional standards.

Audit and feedback is often used in healthcare organisations to improve health professionals’ performance. It is often used together with other interventions, such as educational meetings or reminders. Most of the studies in this review measured the effect of audit and feedback on doctors, although some studies measured the effect on nurses or pharmacists. Audit and feedback was used to influence their performance in different areas, including the proper use of treatments or laboratory tests or improving the overall management of patients with chronic disease such as heart disease or diabetes.

After their performance had been measured, the health professionals were given feedback either verbally, in writing, or both. In some studies, this feedback was given to them by the researchers responsible for the study, while in other studies, feedback was given by supervisors or colleagues, by professional organisations or by someone representing their employer. In some studies, health professionals were given feedback only once, while others were given feedback once a week or once a month.

In some studies, health professionals were simply given information about their performance and how this compared to professional standards or targets. In other studies, health professionals were also given a specific target that they personally were expected to reach, or were given an action plan with suggestions or advice about how to improve their performance.

What happens when health professionals are given audit and feedback?

The effect of using audit and feedback varied widely across the included studies. Overall, the review shows that:

The effect of audit and feedback on professional behaviour and on patient outcomes ranges from little or no effect to a substantial effect. The quality of the evidence is moderate.

Audit and feedback may be most effective when:

1. the health professionals are not performing well to start out with;

2. the person responsible for the audit and feedback is a supervisor or colleague;

3. it is provided more than once;

4. it is given both verbally and in writing;

5. it includes clear targets and an action plan.

In addition, the effect of audit and feedback may be influenced by the type of behaviour it is targeting. It is uncertain whether audit and feedback is more effective when combined with other interventions.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings: Audit and feedback for health professionals.

|

Patient or population: Healthcare professionals Settings: Primary and secondary care Intervention: Audit and feedback with or without other interventions1 Comparison: Usual care | ||||

| Outcomes | Absolute improvement2 | Number of health professionals (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Compliance with desired practice (dichotomous outcomes) |

Median 4.3% absolute increase in desired practice (IQR 0.5% to 16.0%) |

82 comparisons from 49 studies.3 2310 clusters/groups of health providers (from 32 cluster trials) and 2053 health professionals (from 17 trials allocating individual providers). |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | The effect appears to be larger when baseline performance is low, the source is a supervisor or senior colleague, delivered both verbally and written, provided more than once, aims to decrease current behaviours, targets prescribing, and includes both explicit targets and an action plan. |

| Compliance with desired practice (continuous outcomes) |

Median 1.3% improvement in desired practice (IQR 1.3% to 28.9%) |

26 comparisons from 21 studies. 661 clusters/groups of health providers (from 13 cluster trials) and 605 health professionals (from 8 trials allocating individual providers). |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | |

| Patient outcomes (dichotomous) |

Median percent change ‐0.4% (IQR ‐1.3% to 1.6%) |

12 comparisons from 6 studies. | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5 | |

| Patient outcomes (continuous) |

Median percent change 17% (IQR 1.5 to 17%) | 8 comparisons from 5 studies. | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5 | |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence: High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||

1 ‐ The effect of audit and feedback alone on professional practice was similar to audit and feedback as the core, essential feature in multifaceted interventions.

2 ‐ The post‐intervention risk differences are adjusted for pre‐intervention differences between the comparison groups to account for baseline differences. The effect was weighted across studies by the number of health professionals involved in the study to ensure that small trials did not contribute as much to the estimate of effect as large trials.

3 ‐ Many studies had more than two arms and therefore contributed multiple comparisons of audit and feedback versus usual care.

4 ‐ We have downgraded the evidence from high to moderate because of inconsistency in the results that could not be fully explained.

5 ‐ We have downgraded the evidence from moderate to low because of the limited number of trials targeting patient outcomes as a primary outcome.

Background

Audit and feedback is widely used as a strategy to improve professional practice. This review updates a previous Cochrane review of the effects of audit and feedback (Jamtvedt 2006), where we defined audit and feedback as a 'summary of the clinical performance of healthcare provider(s) over a specified period of time'.

Earlier versions of this review found that audit and feedback can have an effect on professional practice and patient outcomes, but even when it is effective, these effects are generally small to moderate. Furthermore, the impact of audit and feedback is highly variable (Jamtvedt 2003; Jamtvedt 2006; Thomson OBrien 1997a;Thomson OBrien 1997b). While few studies have directly investigated the relative effectiveness of different characteristics of audit and feedback, it does seem that feedback has the greatest effect when baseline compliance with recommended practice was low (Jamtvedt 2006). Due to both the heterogeneity of studies and the methodology of these reviews, we remained limited in our ability to make recommendations regarding characteristics most likely to lead to successful feedback interventions.

Foy et al (Foy 2005) concisely summarised the problem stating that, “Audit and feedback will continue to be an unreliable approach to quality improvement until we learn how and when it works best.”

How the intervention might work

Many theories exist (with multiple overlapping constructs) to further explain how feedback may lead to quality improvement (for a review of such theories, see Grol 2007). Briefly, individual behaviour change theories suggest that feedback may work in many ways, including (but not limited to) changing recipient awareness and beliefs about current practice and subsequent clinical consequences, changing perceived social norms, affecting self‐efficacy, or by directing attention to a specific set of tasks (sub‐goals). The observation that the effects of audit and feedback are greatest if baseline compliance is low supports the idea that audit and feedback is felt to be effective as a tool to improve practice because it may overcome healthcare providers’ limited ability to self‐assess accurately (Davis 2006). Under this assumption, providers are thought to be inherently motivated to improve care, but lacking intention to change their current practices in large part because they are unaware of their suboptimal performance. In turn, they may be prompted to modify their practice if given feedback that their clinical practice was inconsistent with their peers or with accepted guidelines.

Nevertheless, even if intention to change behaviour is strong, the desired action may depend on multiple factors beyond the control of the healthcare provider. Organisational theories focused on quality improvement offer clues regarding potential important effect modifiers, including organisational culture with respect to quality improvement, and the ‘actionability’ of feedback reports (Hysong 2006). Van der Veer et al. (Van der Veer 2010) conducted a systematic review of the impact on quality of care of using medical registries to produce feedback reports to healthcare professionals. They analysed 53 studies of widely varying quality and considered both quantitative and qualitative data. Most of the studies featured multifaceted interventions. They noted that important effect modifiers seemed to be the quality of the data provided to recipients, the motivation and interest of recipients, and the organisational support for quality improvement.

Some potentially important variables are difficult to operationalise in a trial and others have been tested with uncertain results. For instance, although perceived social and professional norms are considered important predictors of behaviour change, there is conflicting evidence regarding the role of peer‐comparison in feedback (Kiefe 2001; Søndergaard 2002; Wones 1987). In an attempt to further delineate how to most effectively design and deliver feedback interventions, Hysong (Hysong 2009) completed a re‐analysis of the 2006 Cochrane review based on "Feedback Intervention Theory" (Kluger 1996). The results showed greater effectiveness with increasing frequency of the feedback, with written rather than verbal or graphical delivery and with feedback that included information about the correct solution.

Similarly, Gardner and colleagues (Gardner 2010) conducted a re‐analysis of the 2006 Cochrane review that applied the Control Theory of Carver and Scheier (Carver 1982), to test target‐setting and action plans as effect‐modifiers of feedback. Although the results of that re‐analysis were inconclusive because very few studies explicitly described their use of targets or action plans, there is empirical evidence from non‐health literature to suggest that goal‐setting can increase the effectiveness of feedback (Locke 2002), especially if specific and measurable goals are used. However, the role of participant involvement in either target‐setting or in feedback interventions seems promising (BMJ 1992) but remains uncertain (Nasser 2008). Other empirical work from the psychology literature has demonstrated the value of action‐plans with respect to improving the effectiveness of feedback (Sniehotta 2009).

Regardless of the feedback design, the nature of the clinical change that the feedback tries to encourage may play a role in the effectiveness of the intervention. Qualitative work indicates that it may be easier to comply with guidelines that aim to increase rather than decrease behaviours (Carlsen 2007).

Why it is important to do this review

The aim of the current update is to investigate the effectiveness of audit and feedback to improve processes and outcomes of care and to examine factors that could influence the effectiveness of this intervention. Given the variability in results of the prior review and the inability to satisfactorily explain this based on intuitive factors, this review will attempt to examine multiple theory‐informed feedback design characteristics. In so doing, we hope this review will clarify the effectiveness of audit and feedback in general and inform stakeholders regarding how to best employ feedback to change provider behaviours.

Objectives

We will address three primary questions in this review:

1. Is audit and feedback effective for improving health provider performance and healthcare outcomes?

2. What are the key factors that explain variation in the effectiveness of audit and feedback?

3. How does the effectiveness of audit and feedback compare to other interventions?

For question 1, we considered the following comparisons.

Comparison A. Audit and feedback alone or as the core/essential feature of a multifaceted intervention compared with usual care (includes comparisons B and C).

Comparison B. Audit and feedback (alone) compared with usual care.

Comparison C. Audit and feedback as the core/essential feature of a multifaceted intervention compared with usual care.

For question 2, we considered the following comparisons.

Comparison D. Head‐to‐head comparisons of different types of audit and feedback interventions (effect of changing the way that audit and feedback is designed or delivered).

Comparison E. Audit and feedback as the core/essential feature of a multifaceted intervention compared with audit and feedback alone (effect of adding different co‐interventions to audit and feedback).

In addition, for question 2 we also conducted a meta‐regression on the studies in comparison A . In the previous review, we subjectively categorised both the “intensity” of the feedback intervention and the “complexity” of the targeted behaviour, but this approach did not adequately predict feedback effectiveness in a manner that would clearly inform future intervention design. Therefore, to investigate the effectiveness of different ways of providing audit and feedback and other factors that might modify the effects of audit and feedback, studies in this review were characterised according to a selection of variables considered to be both important (based on relevant literature reviewed in the background section above and our knowledge of theories of behaviour change) and accessible in published manuscripts (based on the prior experience of our systematic review authors). Specifically, we used meta‐regression to examine the effects of four ways of providing audit and feedback that might increase its effectiveness.

Providing instruction for improvement with the feedback in the form of specific goals and/or action plans

Providing verbal feedback in addition to written feedback

Providing feedback from a senior or respected colleague, supervisor, employer, purchaser or professional standards review organisation (compared with feedback provided by researchers)

Providing more frequent feedback

We also examined additional factors not related to the intervention itself that might increase the effects of audit and feedback or its apparent effects.

Lower baseline compliance

Feedback requiring increasing current behaviours (compared to decreasing behaviours or changing the approach to a clinical problem)

Audit and feedback targeting health professionals other than physicians

Higher risk of bias in the primary study

There are many important factors that may predict effectiveness of audit and feedback; the basis for selecting the above factors to examine in a meta‐regression and not including other potential effect modifiers is summarised in Appendix 1. (This appendix is not a comprehensive listing of all possible audit‐and‐feedback questions, but includes the key factors that we considered for inclusion in this update.)

We recognize the importance of context with respect to the effectiveness of an intervention. In particular, the relative complexity of the targeted behaviour likely plays a role in the ability of feedback to increase guideline adherence. To investigate this issue, we conducted a limited number of exploratory subgroup analyses based on the target of the intervention.

For question 3, we considered the following comparison.

Comparison F. Audit and feedback alone or as the core/essential feature of a multifaceted intervention compared with other interventions

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

Healthcare professionals responsible for patient care. Healthcare professionals in postgraduate training were included, but studies involving only undergraduate students were not.

Types of interventions

Audit and feedback, defined as 'any summary of clinical performance of health care over a specified period of time'. One may alternatively describe an audit and feedback intervention as 'clinical performance feedback'. The feedback may include recommendations for clinical action and may be delivered in a written, electronic or verbal format.

Studies that focused on real‐time feedback for procedural skills were excluded as were studies in which the feedback focused on performance on tests or simulated patient interactions. Studies that featured facilitated relay of communication regarding patient status or symptoms but that did not provide a summary of physician performance were also excluded. In general, even if the term 'feedback' was used in the manuscript, the study was excluded if the intervention would be best classified as 'facilitated relay' of patient‐specific clinical information or a 'reminder' (especially when the intervention was at the point of care), or any other unique category in the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) (EPOC 2002) classification of quality improvement interventions other than 'audit and feedback' (see also: Shojania 2006).

For this update, we only included interventions where we assessed audit and feedback to be a core or essential element. To this end, we categorised studies by the extent to which audit and feedback was the core component of the intervention into three groups: (i) audit and feedback alone; (ii) audit and feedback as a core, essential component of a multifaceted intervention; or (iii) audit and feedback as a component of a multifaceted intervention but not considered ‘core and essential’. In multifaceted interventions (which we defined as studies that utilised two or more interventions aiming to change the behaviour of health professionals), we made the distinction between 'core' and 'not core' by considering whether the other components were likely to be used in the absence of audit and feedback, or whether the audit and feedback seemed to provide the foundation for the rest of the intervention. In cases where the audit and feedback was merely added to a multifaceted intervention that could easily be offered in its absence, the study would be classified as 'not core'.

For comparisons C, D, E, and F, we used the EPOC classification (EPOC 2002) scheme to identify the components of the multifaceted interventions. We used this classification to differentiate between RCTs that tested different ways of designing or delivering an audit and feedback intervention (comparison D) and RCTs that tested whether additional intervention(s) along with audit and feedback were more effective than audit and feedback alone (comparison E). To illustrate, when a suggestion for improvement accompanies the feedback report, it may alternatively be viewed as a co‐intervention (clinician education) or as an intrinsic feature of the feedback design (action plan). As with all other abstracted descriptive variables, this process was completed independently by two abstractors and discrepancies resolved through discussion, including other authors as needed.

Types of outcome measures

We focused on objectively measured provider performance in a healthcare setting or patient health outcomes. We abstracted outcomes from the longest available follow‐up interval in the original publication, but we did not abstract data from separate articles or companion reports wherein longer term follow‐up was reassessed. Studies that provided data only on cost were excluded as were studies that measured knowledge or performance in a test situation only.

Search methods for identification of studies

The current search strategies differ from the strategies used in previous versions of this review. For this version we developed the MEDLINE search strategy based on all MEDLINE indexed and included studies from the previous review versions, in addition to studies known to be eligible for inclusion, but not yet included, a total of 144 records. One hundred and twenty‐eight of the 144 records (89%) were identified by the current MEDLINE strategy. We then translated this strategy into the other databases using the appropriate controlled vocabulary as applicable. CENTRAL and CINAHL were searched without time limits. As we searched for RCTs only, MEDLINE was searched from 2005 onwards and EMBASE from 2010 onwards. We expected that MEDLINE records prior to 2005 and EMBASE records prior to 2010 would have been found in CENTRAL. Full search strategies for all databases ‐ for the current update and for the previous review ‐ are available in Appendix 2.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2010, Issue 4, part of The Cochrane Library.www.thecochranelibrary.com, including the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group Specialised Register (searched 10 December 2010)

MEDLINE, Ovid (1950 to November Week 3 2010) (searched 09 December 2010)

EMBASE, Ovid (1980 to 2010 Week 48) (searched 09 December 2010)

CINAHL, Ebsco (1981 to present) (searched 10 December 2010)

Science Citation Index and Social Sciences Citation Index, ISI Web of Science (1975 to present) (searched 12‐15 September 2011)

Searching other resources

We searched the Science Citation Index and the Social Sciences Citation Index for studies citing all included studies in this review, in addition to selected studies from the review's Additional references list: (Axt‐Adam 1993; Balas 1996; Foy 2002; Foy 2005; Gardner 2010; Hysong 2006; Hysong 2009; Van der Veer 2010). Reference lists of all included studies were reviewed and potentially relevant ones are included in the list of Studies awaiting classification, together with potentially relevant studies retrieved from the citation search. These will be included in a future update of this review.

Data collection and analysis

The following methods will be used in updating this review.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (NI, GJ, SFl, or JY) independently screened the titles and abstracts and applied inclusion criteria; complete manuscripts were sought in the case of uncertainty and differences of opinion resolved through consensus. Conference abstracts were included if they provided sufficient data, a full report could be found or missing data could be obtained from the investigators. For this version of the review, we reassessed whether each study from the previous review met the inclusion criteria.

We categorised the extent to which audit and feedback was the 'core' component of the intervention as follows.

Audit and feedback alone (included)

Audit and feedback as a core, essential component, combined with other interventions categorised according to EPOC classification scheme (included)

Audit and feedback as a component of a multifaceted intervention but not considered ‘core and essential’ (excluded)

Multifaceted interventions were defined as including two or more interventions. Where audit and feedback was not considered to be a core, essential component of the intervention, the study was excluded. In other words, this review included multifaceted interventions when the other components were judged to be unlikely to be used in the absence of audit and feedback, or were built around the audit and feedback, which provided the foundation for the rest of the intervention (rather than the audit and feedback being added to a multifaceted intervention that could easily be offered in its absence).

This was assessed independently by two review authors (NI, GJ, SFl, or JY); of all abstracts screened, only eight disagreements regarding inclusion were due to differences in the assessment of whether or not the article was 'core' audit and feedback. All disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data extraction and management

Data from included studies were abstracted independently by two review authors (NI, GJ, SF, or SFr). A revised version of the EPOC data collection checklist was used to collect information on study design, type of interventions compared, type of targeted behaviour, participants, setting, methods, outcomes, and results. Discrepancies between authors were resolved through discussion. Studies included in the previous review were reassessed due to changes in the data abstraction form and methods for this updated review. For articles included in the previous review, the new variables analysed in this update (instruction for improvement and direction of change required) were abstracted by one author (NI). In all other cases, the variables have been double‐abstracted. For numerical results, abstraction was performed by one author (NI) and double‐checked by another author (GJ, SF, or SFr).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (GJ, NI, SFl, or SFr) independently assessed the risk of bias of each study and extracted data for newly identified studies using a revised data collection form; discrepancies were resolved by consensus with a third author as needed. The risk of bias for each main outcome in all studies included in the review was assessed according to the revised EPOC criteria. The degree of confidence in the estimate of effect across studies was assessed using GRADEpro and the GRADE approach (Guyatt 2008; Schunemann 2008, Schunemann 2009).

An overall assessment of the risk of bias (high, moderate or low risk of bias) was assigned to each of the included studies using the approach suggested in the Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). Studies with low risk of bias for all key domains or where it seems unlikely for bias to seriously alter the results were considered to have a low risk of bias. Studies where risk of bias in at least one domain was unclear or judged to have some bias that could plausibly raise doubts about the conclusions were considered to have an unclear risk of bias. Studies with a high risk of bias in at least one domain or judged to have serious bias that decreased the certainty of the conclusions were considered to have a high risk of bias. For the studies included in the previous review, one review author (NI) updated the 'Risk of bias' assessment using this approach. Any discrepancies between the conclusions regarding risk of bias using the new and the previous approach were discussed with other review authors and resolved through consensus

Measures of treatment effect

All outcomes were expressed as compliance with desired practice. Professional and patient outcomes were analysed separately. For trials reporting summary and individual measures of performance, the summary measures were used. When several outcomes were reported in a trial we only extracted results for the variable(s) explicitly described as the primary outcome(s). When the primary outcome was not specified we took the variable(s) described in the sample size calculation as the primary outcome. When the primary outcome was still unclear or when the manuscript described several primary outcomes, we calculated the median value across multiple outcomes.

Since important baseline differences between intervention and control groups are frequently found in cluster‐randomised trials, our primary analyses was based on estimates of effect that were adjusted for baseline differences. Therefore, only studies providing data on baseline performance were included in the statistical analysis. Baseline compliance, defined as compliance with desired practice (or with the targeted behaviours) prior to the intervention, was treated as a continuous variable ranging from zero to 100%, based on the median value of pre‐intervention level of compliance in the audit and feedback group and control group. For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the adjusted risk difference (RD) as the difference in adherence after the intervention minus the difference before the intervention. A positive RD indicates that performance improved more in the audit and feedback group than in the control group (eg. an adjusted RD of 0.09 indicates an absolute improvement in compliance with targeted behaviours of 9%). For continuous outcomes, we calculated adjusted change relative to the control group as the post‐intervention difference in means minus the baseline difference in means divided by the baseline control group mean. As with the adjusted RD, a positive change indicates that performance improved more in the audit and feedback group than in the control group. This is a relative effect rather than an absolute effect; the effect size reflects the baseline performance as well as the change in performance and it is not bound between ‐100 and +100%.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

Due to the nature of the intervention, we expected that most of the trials would be randomised by cluster. Under such circumstances it is necessary to adjust results from primary trials for clustering before they are included in a meta‐analyses in order to avoid underestimating the standard error (SE) of the estimate of effect. As in the previous versions of this review, we have not abstracted the observed SEs, P values, or confidence intervals for our statistical analysis, instead performing meta‐regression using the number of health professionals as the basis for weighting.

Studies with more than two arms

If more than one comparison from a study with more than two arms were eligible for the same comparison, we adjusted the number of healthcare professionals to avoid double counting. The adjustment was done by dividing the number of healthcare professionals in the shared arm approximately evenly among the comparisons.

Dealing with missing data

Only studies reporting baseline data for primary outcomes were included in the statistical analysis because the previous review identified baseline performance as an important predictor of feedback effectiveness. Missing data regarding the characteristics of the studies or of the audit and feedback intervention were not imputed.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We explored heterogeneity visually by preparing tables, bubble plots and box plots (displaying medians, inter‐quartile ranges, and ranges) to explore the size of the observed effects in relationship to each of these variables. The size of the bubble for each comparison corresponds to the number of healthcare professionals who participated. We also plotted the lines from the weighted regression to aid the visual analysis of the bubble plots.

Data synthesis

Across studies, the median effect size was weighted by the number of health professionals involved in the trial reported to ensure that very small trials did not contribute the same to the overall estimate as larger trials. If the number of health professionals was not reported, the number of practices/hospitals/communities was used instead. Thus, the summary statistics in the meta‐analyses reported as weighted median adjusted RD or weighted median adjusted change relative to baseline control are weighted by the number of health professionals, while the results reported from individual studies are not. The primary analyses excluded studies at high risk of bias.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Visual analyses were supplemented with meta‐regression to examine how the size of the effect (adjusted RD) was related to the potential explanatory variables (listed below), weighted according to the number of healthcare professionals. We accounted for baseline differences in compliance by using adjusted estimates of effect to avoid the effect of potentially important baseline differences in compliance between groups. We conducted a multivariable linear regression using main effects only; baseline compliance treated as a continuous explanatory variable and the others as categorical. For this analysis we excluded studies with a high risk of bias. The analyses were conducted using the GLIMMIX procedure in SAS (Version 9.2. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), where we also took the dependency between comparisons from the same trial into account. P values were based on the classical sandwich estimator.

Each comparison was characterised relative to the other variables in the tables, looking at one potential explanatory variable at a time in univariate analyses. If the number of included studies was large enough, we also performed a multivariate analysis including all potential explanatory variables. We assessed the following potential sources of heterogeneity to explain variation in the results of the included studies.

Format (verbal; written; both; unclear)

Source (supervisor or senior colleague; professional standards review organisation or representative of employer/purchaser; investigators; unclear)

Frequency (weekly; monthly; less than monthly; one‐time)

Instruction for improvement (explicit measurable target or specific goal but no action plan; action plan with suggestions or advice given to help participants improve but no goal/target; both; neither)

Direction of change required (increase current behaviour; decrease current behaviour; mix or unclear)

Recipient (physician; other health professional)

Risk of bias (high; unclear; low)

Baseline compliance (continuous measure of health professionals' compliance with desired practice)

We hypothesised that audit and feedback with the following characteristics would be most effective: provided in both verbal and written format, from a supervisor or senior colleague, delivered more frequently than less, featuring both specific goals and action plans, aiming to increase rather than decrease behaviours, and received by non‐physician providers. We also hypothesised that studies with low risk of bias would be associated with smaller effect sizes.

In addition, we conducted two exploratory analyses to examine the importance of context and the relative complexity of the targeted behaviour on the likelihood that feedback would improve professional practice. We compared the effectiveness of feedback in outpatient (primary care or outpatient clinics) and hospital (inpatient, emergency room or hospital) settings. In addition, we considered common targets of feedback interventions, including: appropriate prescribing, test‐ordering (laboratory or radiology), and diabetes or cardiovascular disease management (two chronic clinical conditions with similar management and targets). We did not have any a priori hypotheses for these analyses. However, the second analysis reflects two hypotheses that we tested in the previous update of this review: that the effectiveness of feedback would be greater for behaviours that are important but not complex (ie. prescribing) compared to more complex behaviours (ie. disease management) or compared to behaviours that clinicians might perceive as less important (ie. test‐ordering). For these analyses, we compared the weighted median effect sizes and conducted a univariate meta‐regression for studies reporting dichotomous outcomes. If we found potentially important and statistically significant differences, we included these explanatory factors in the full model for the meta‐regression described above to assess the robustness of these exploratory findings.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses by including studies with a high risk of bias. We also examined whether differences in the level of the unit of analysis (groups of professionals versus individual professionals versus patients) was a source of heterogeneity, since analyses conducted at different levels can result in different effect estimates.

Results

Description of studies

For this update we screened 3623 new studies and reviewed the full text of 282. The total number of studies included is 140. Of note, 53 new studies were added to this review since the previous update and 31 were removed from the previous version of the review as they no longer met our inclusion criteria. See study flow diagram for details (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

All abstracted information is available upon request; the general characteristics of the included studies are described in Table 2.

1. Description of Included Trials (N = 140).

| Study Characteristic | Number | Percent | Intervention Characteristic | Number | Percent | |

| Publication Year | Audit and Feedback alone | 49 | 35.0 | |||

| 2006‐2010 | 32 | 22.9 | Multifaceted intervention with AF as core feature | 91 | 65.0 | |

| 1996‐2005 | 76 | 54.3 | with Case management or team change | 3 | 2.1 | |

| 1986‐1995 | 20 | 14.3 | with Clinician education (not outreach) | 48 | 34.3 | |

| before 1986 | 12 | 8.6 | with Educational outreach | 28 | 20.0 | |

| Country | with Clinician reminders, including decision support | 17 | 12.1 | |||

| USA | 69 | 49.3 | with Patient intervention (eg. self mgmt/reminders) | 8 | 5.7 | |

| UK or Ireland | 21 | 15.0 | with Continuous quality improvement | 9 | 6.4 | |

| Canada | 11 | 7.9 | with Financial incentives | 5 | 3.6 | |

| Australia or New Zealand | 10 | 7.1 | Format | |||

| Other | 29 | 20.7 | Verbal | 13 | 9.3 | |

| Unit of Allocation | Written | 84 | 60.0 | |||

| Provider | 51 | 36.4 | Both | 32 | 22.9 | |

| Many Providers/Groups | 88 | 62.9 | Unclear | 11 | 7.9 | |

| Unclear | 1 | 0.7 | Source | |||

| Unit of Analysis | Supervisor/colleague | 13 | 9.3 | |||

| Patient | 81 | 57.9 | Employer | 15 | 10.7 | |

| Provider | 29 | 20.7 | Investigators/unclear | 112 | 80.0 | |

| Many Providers/Groups | 29 | 20.7 | Frequency | |||

| Unclear | 1 | 0.7 | Weekly | 11 | 7.9 | |

| Risk of Bias | Monthly | 19 | 13.6 | |||

| Low | 45 | 32.1 | Repeated less than monthly | 36 | 25.7 | |

| Unclear | 70 | 50.0 | Once only | 68 | 48.6 | |

| High | 25 | 17.9 | Instructions for Improvement | |||

| Number of Arms in Trial | Goal‐setting | 11 | 7.9 | |||

| Two | 98 | 70.0 | Action planning | 41 | 29.3 | |

| Three | 22 | 15.7 | Both | 4 | 2.9 | |

| Four | 20 | 14.3 | Neither | 84 | 60.0 | |

| Clinical Setting | Direction of Change Required | |||||

| Outpatient | 94 | 67.1 | Increase current behaviour | 57 | 40.7 | |

| Inpatient | 36 | 25.7 | Decrease current behaviour | 29 | 20.7 | |

| Other/unclear | 10 | 7.1 | Mix or unclear | 55 | 39.3 | |

| Medical Specialty (could include more than one) | Targeted Health Professional (could include more than one) | |||||

| GP/Family physician | 84 | 60.0 | Physician | 121 | 86.4 | |

| Internists | 60 | 42.9 | Nurses | 16 | 11.4 | |

| Other | 40 | 28.6 | Pharmacists | 5 | 3.6 | |

| Other | 3 | 2.1 | ||||

| Clinical Topic / Targeted Behaviour (could be more than one) | ||||||

| Diabetes/Cardiovascular disease management | 30 | 21.4 | ||||

| Size of trial | Median | IQR | Laboratory testing/radiology | 21 | 15.0 | |

| Providers (when providers allocated) | 56 | 28‐139 | Prescribing | 31 | 22.1 | |

| Groups (when many providers allocated) | 32 | 19‐69 | Other | 50 | 41.4 | |

The unit of allocation was a single healthcare provider in 51 studies (5056 total providers, median 56), groups of clusters of healthcare professionals (e.g. clinics, wards, hospitals, communities) in 88 studies (5267 total clusters, median 32), and in one study (24 providers, 1140 patients) the unit of allocation was not clear (Everett 1983). Twenty studies had four arms, 22 studies had three and the remaining 98 had two arms.

Characteristics of setting and professionals

Eighty trials were based in North America (69 in USA, 11 in Canada), 21 in the UK or Ireland, 10 in Australia or New Zealand, and 29 elsewhere. Only four studies were from low‐ and middle‐income countries (two in Sudan, one in Thailand, and one in Laos).

In 121 trials the targeted health professionals for the intervention were physicians. Five studies explicitly targeted pharmacists and 16 studies explicitly targeted nurses. The most common clinical specialty area was general or family practice, targeted in 84 trials. Ninety‐four trials were in an outpatient setting, 36 were in inpatient settings, and in 10 studies the clinical setting was unclear.

Targeted behaviours

There were 39 trials specifically aiming to improve appropriate prescribing and 31 specifically targeting laboratory or radiology test utilisation. Thirty‐four trials focused on management of patients with either cardiovascular disease or diabetes (two exemplar chronic conditions with common management strategies). The remaining trials varied widely across conditions and targeted behaviours.

Characteristics of interventions

There were 49 studies in which audit and feedback was the only intervention, while audit and feedback was considered the core, essential component of a multifaceted intervention in 91 studies.

The format of the feedback was clearly reported in 129 studies: 13 had verbal feedback, 84 had written feedback, and 32 had both. In the majority of studies (112), the source of the feedback was unclear or it was provided by the researchers who had no other relationship to the recipients. In 13 studies feedback was provided from a supervisor or senior colleague, and in 15 from a 'professional standards review organisation' or representative of the employer or purchaser. The frequency of the feedback was weekly in 11 trials, monthly in 19 trials, repeated but less than monthly in 36, and once only in 68 trials.

In 11 studies the feedback provided recipients with explicit, measurable goals and 41 studies included action plans or correct solution information with the feedback. The feedback had both these features in four studies and neither in 84 studies. In 57 studies, the feedback required recipients to increase current behaviours; in 29 they had to decrease current behaviours, and in 55 studies the feedback was judged to require a complex or uncertain change in behaviour.

Outcome measures

There was large variation in outcome measures, and studies often reported multiple primary outcomes related to compliance with different aspects of a guideline. Most trials measured professional practice, such as prescribing or use of laboratory tests. Some trials reported both practice and patient outcomes such as smoking status or blood pressure. There was a mixture of dichotomous outcomes (for example the proportion compliance with guidelines or the proportion of patients with appropriate management) and continuous outcome measures (for example costs, number of laboratory tests, or number of prescriptions) across and within studies.

Baseline performance was not reported in 10 studies (Balas 1998; Berman 1998; Curtis 2007; Everett 1983; Linn 1980; Lobach 1996; Robling 2002; Sandbaek 1999; Tierney 1986; Wones 1987).

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 2. Of the 140 trials, 44 (31%) had a low risk of bias, 71 (51%) had an unclear risk of bias, and 25 (18%) had a high risk of bias (Baker 1997; Batty 2001; Berman 1998; Boekeloo 1990; Brown 1994; Buffington 1991; Canovas 2009; Charrier 2008; Claes 2005; Curran 2008; Everett 1983; Foster 2007; Gama 1992; Gehlbach 1984; Kim 1999; Millard 2008; Robling 2002; Rust 1999; Sandbaek 1999; Schneider 2008; Sommers 1984; Søndergaard 2006; Wadland 2007; Winkens 1995; Zwar 1999). The most common sources of a high risk of bias related to lack of similarity at baseline (ten trials), lack of outcome blinding (e.g. when outcomes were reported by participating healthcare professionals) (ten trials), and due to incomplete follow‐up (six trials). Clarity of reporting regarding the risk of bias variables was frequently inadequate. For example, the nature of the randomisation sequence was unclear in 81 trials, outcome blinding was unclear in 61 trials, similarity at baseline was unclear in 48 trials, and risk of contamination was unclear in 45 trials. Randomisation was clearly concealed (or there was cluster randomisation) in 117 trials. There was adequate follow‐up in 111 trials.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See Table 1.

Comparison A. Any intervention in which audit and feedback is the single intervention or is the core, essential feature of a multifaceted intervention, compared to usual care

A total of 171 comparisons from 109 studies were included in this comparison. Of these, 17 comparisons from 10 studies had no baseline data, and 21 comparisons from 14 studies were at high risk of bias. Twenty‐five comparisons from 15 studies included patient outcomes as a primary outcome. Thus, 108 comparisons from 70 studies were included in the primary analyses assessing the effects of audit and feedback on professional practice.

Dichotomous measures of compliance with desired practice

There were 124 total comparisons, of which 11 comparisons were removed due to lack of adequate baseline data. Of the 113 remaining comparisons, 15 had patient‐oriented outcomes, leaving 98 comparisons from 62 studies. In the primary meta‐analysis, a further 16 comparisons from 12 studies at high risk of bias were excluded, leaving 82 comparisons from 49 studies with dichotomous outcomes. These studies included 2310 clusters/groups of health providers (from 32 cluster trials), and 2053 health professionals (from 17 trials allocating individual providers).

For these studies, the weighted median adjusted RD was a 4.3% increase in compliance with desired practice (interquartile range (IQR) 0.5% to 16%). The weighted median RD when studies with high risk of bias were included in the sensitivity analysis was also 4.3% (IQR 0.6% to 16%).

The range in adjusted RDs for compliance with desired practice was wide: a 9% absolute decrease to a 70% increase in compliance. Of the 98 total comparisons, 27 had an adjusted RD of at least 10% and in 20 comparisons the adjusted RD was between 5% and 10%. For 50 comparisons the adjusted RD was small (ranging from ‐5% to 5%). Only one study reported a negative effect greater than 5%; an adjusted RD of ‐9% for appropriate prescribing of benzodiazepines (Batty 2001). This study had a high risk of bias due to imbalance at baseline. Three other studies had unusually large effect sizes. Foster 2007 reported a 45% increase in the utilisation of peak flow in asthma patients. This study had a high risk of bias due to incomplete follow‐up. Gehlbach 1984 reported a 45% improvement in the use of generic prescriptions and this study also had a high risk of bias. Finally, Mayer 1998 showed a 70% increase in the provision of skin cancer preventive advice among pharmacists, from a baseline performance of 0%. As in the previous version of this review, this study was excluded from the primary analysis because it differed from the others, as it aimed to initiate an entirely new clinical behaviour in the intervention group, rather than help providers to improve their performance in an area of known professional responsibility.

There were 11 comparisons from seven studies with dichotomous outcomes that did not report baseline data (Balas 1998; Berman 1998; Curtis 2007; Lobach 1996; Robling 2002; Sandbaek 1999; Tierney 1986). The range of (unadjusted) RD seen in these studies was ‐2.3% to 29.2%. The median unadjusted RD for these studies was 4% (IQR 1% to 7%).

Continuous measures of compliance with desired practice

There were 47 total comparisons, of which six were removed due to lack of adequate baseline data. Of the 41 remaining comparisons with continuous primary outcomes, 10 had patient‐oriented outcomes, leaving 31 comparisons from 25 studies. The primary meta‐analysis excluded a further five comparisons from four studies at high risk of bias leaving 26 comparisons from 21 studies with continuous outcomes. These studies included 661 groups of healthcare providers (from 13 cluster trials) and 605 healthcare professionals (from eight trials allocating individual providers).

For these studies, the weighted median adjusted change relative to baseline control was a 1.3% increase in compliance with desired practice (IQR 1.3% to 23.2%). When studies at high risk of bias were included, the weighted median adjusted change relative to baseline control was 2.9% (IQR 1.3% to 26.1%).

The adjusted change relative to baseline control varied widely, from a 50% decrease in desired practice to a 139% increase in desired practice. Of the 31 total comparisons with continuous outcomes, 21 had an adjusted change relative to baseline control of at least 10%. For eight comparisons the adjusted change relative to baseline control was relatively small (‐5% to 5%). Two comparisons had larger negative effects: one (Holm 1990) showed a 10% relative increase in benzodiazepine/sedative medications; the other comparison (Cohen 1982) showed a 50% relative increase in laboratory test utilisation, but actually reported a positive effect during the intervention period, which reversed after the intervention stopped. The trial (Wadland 2007) that reported a 139% relative increase in smoking cessation referrals had a high risk of bias.

There were six comparisons from three studies with continuous outcomes that did not report baseline data (Everett 1983; Linn 1980; Wones 1987). The median effect seen in these studies was a 54% relative increase in desired practice (IQR 15.1% to 54%)

Patient outcomes

Fifteen studies (Buffington 1991; Curran 2008; Fairbrother 1999; Gullion 1988; Hemminiki 1992; Hendryx 1998; Linn 1980; Lomas 1991; Mitchell 2005; O'Connor 2009; Phillips 2005; Rantz 2001; Rust 1999; Svetkey 2009; Thomas 2007) reported patient‐type outcomes as a primary outcome. One study (Linn 1980) did not have any baseline data, and two studies (Buffington 1991; Curran 2008) had a high risk of bias, leaving 12 comparisons with dichotomous outcomes and eight comparisons with continuous outcomes for analysis.

There was minimal discernable effect observed for patient outcomes with dichotomous outcomes, while a positive effect was noted in studies with continuous outcomes. Specifically, for dichotomous outcomes, the weighted median adjusted RD was a 0.4% decrease in desired outcomes (IQR ‐1.3% to 1.6%) and for continuous outcomes, the weighted median adjusted change relative to baseline control was a 17% improvement (IQR 1.5% to 17%).

Investigation of heterogeneity

The multivariable meta‐regression analysis explored the role of five characteristics of the intervention (format, source, frequency, instructions for improvement, direction of change required), two characteristics of the recipients (baseline performance, profession), and one characteristic of the trial design (risk of bias) on heterogeneity in effect size. This was performed on trials that had dichotomous outcomes and that compared audit and feedback as the only intervention or as the core, essential feature of a multi‐faceted intervention versus usual care. Studies at high risk of bias were excluded, leaving 80 comparisons in this analysis with either unclear or low risk of bias.

All five characteristics of the intervention were identified as significant in the model, as described in Table 3, indicating that the format (P = 0.02), source (P < 0.001), frequency (P < 0.001), instructions for improvement (P < 0.001), and the direction of change required (P = 0.007) each help explain variation in effects. Within these variables, relatively large differences in effect size were seen when comparing certain characteristics: presented in both verbal and written format versus only verbal (expected difference in adjusted RD = 8%); delivered by a supervisor or senior colleague versus the investigators (expected difference in adjusted RD = 11%); frequency of monthly versus once only (expected difference in adjusted RD = 7%); containing both an explicit, measurable target and a specific action plan versus neither (expected difference in adjusted RD = 5%); and requiring a decrease versus an increase of current behaviour to achieve a higher score (expected difference in adjusted RD = 6%).

2. Assessment of Heterogeneity: results from meta regression.

| Characteristic of the Feedback or Recipient or Trial | Effect | |

| Format of feedback | P = 0.020 | |

| Verbal | 3.38 | |

| Written | 9.50 | |

| Both verbal and written | 11.23 | |

| Not clear | 5.27 | |

| Source of feedback | P < 0.001 | |

| A supervisor or colleague | 16.50 | |

| A 'professionals standards review organization' or employer | 2.37 | |

| The investigators | 5.04 | |

| Not clear | 5.48 | |

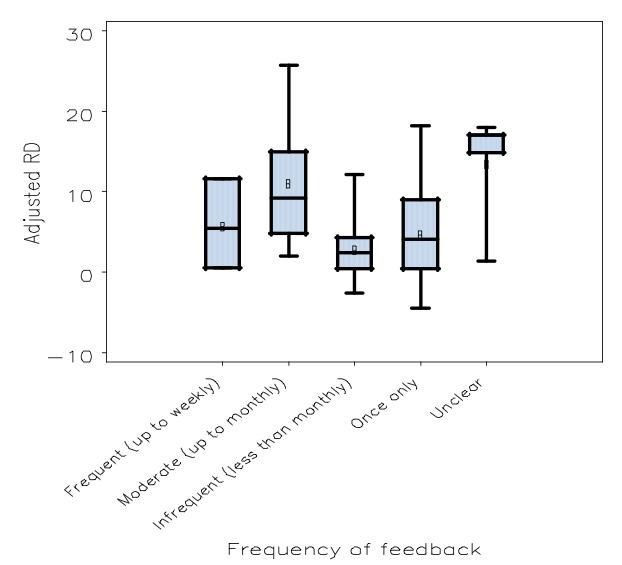

| Frequency of feedback | P < 0.001 | |

| Frequent (up to weekly) | 1.44 | |

| Moderate (up to monthly) | 9.83 | |

| Infrequent (less than monthly) | 4.78 | |

| Once only | 2.56 | |

| Unclear | 18.12 | |

| Instructions for improvement | P < 0.001 | |

| Explicit, measurable target/goal, but no action plan | 2.52 | |

| Action plan | 9.57 | |

| Both | 11.09 | |

| Neither | 6.20 | |

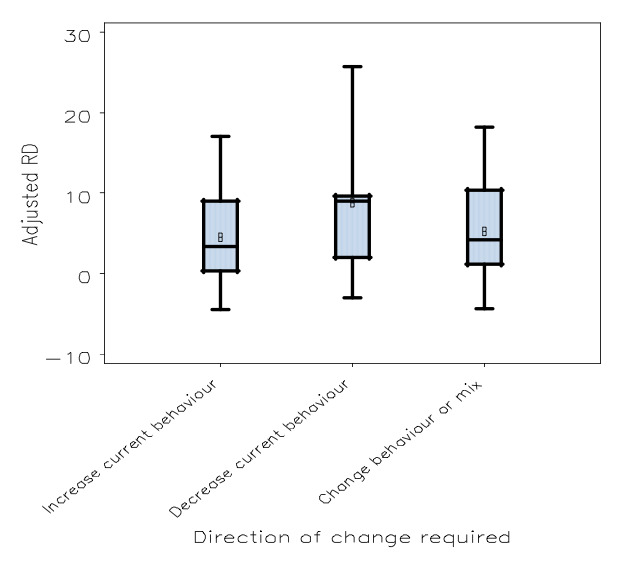

| Direction of change required | P < 0.001 | |

| Increase current behaviour | 4.34 | |

| Decrease current behaviour | 10.54 | |

| Change behaviour or mix or unclear | 7.16 | |

| Baseline performance | P = 0.007 | |

| at 25% | 9.11 | |

| at 50% | 7.07 | |

| at 75% | 5.03 | |

| Profession of recipient | P = 0.561 | |

| Physician | 7.90 | |

| Non‐physician | 6.80 | |

| Risk of bias | P = 0.679 | |

| Low risk of bias | 7.68 | |

| Unclear | 7.02 | |

| High risk of bias (not included in primary analysis) | n/a | |

Risk of bias (P = 0.679) and profession (physician versus non‐physician) (P = 0.561) were not associated with variation in effect size. Lower baseline performance was associated with greater effectiveness for the intervention (P = 0.007). To illustrate, the model predicts that recipients who achieved 25% of desired practice at baseline would have an expected adjusted RD of 9%, while those who achieved 75% of desired practice at baseline would have an expected adjusted RD of only 5%. See Figure 3 for a bubble plot of effect size by baseline performance.

3.

Bubble plot: adjusted risk difference by baseline performance

Examination of box plots for each of the explanatory variables primary analysis supported the statistical conclusions (see Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9). For exploratory purposes, we also examined box plots for explanatory variables considering trials with continuous outcomes from Comparison A. This did not result in any qualitative differences in the assessment of heterogeneity. Finally, we examined the box plots for trials with dichotomous and continuous outcomes, respectively, for Comparison B (audit and feedback alone versus usual care) and then for Comparison C (audit and feedback as the core, essential feature of a multifaceted intervention versus usual care), separately. These analyses revealed consistency in the direction of effects for the explanatory variables, supporting the initial conclusions.

4.

Box plot: comparing adjusted risk difference by format of feedback

5.

Box plot: comparing adjusted risk difference by format of feedback

6.

Box plot: comparing adjusted risk difference by source of feedback

7.

Box plot: comparing adjusted risk difference by frequency of feedback

8.

Box plot: comparing adjusted risk difference by presence/extent of instructions for improvement in feedback

9.

Box plot: comparing adjusted risk difference by direction of change required by the feedback

Although the multifaceted studies appeared to have a larger median effect size, when comparing the mean estimate of effect for audit and feedback alone versus audit and feedback in a multifaceted intervention using a univariate analysis we found that the differences were not statistically significant for dichotomous outcomes (estimated absolute difference in adjusted RD = 3.3%; P = 0.27). The similarity in estimated adjusted RD is illustrated in Figure 10. However, there was a significant difference when examining the studies with continuous outcomes (estimated absolute difference in adjusted change relative to baseline control = 24%; P < 0.0001).

10.

Box plot: comparing adjusted risk difference for Comparison B (audit and feedback alone versus usual care) and Comparison C (multifaceted intervention featuring audit and feedback versus usual care)

The sensitivity analysis adding level of analysis (patient versus provider versus cluster) to the model did not lead to any significant changes in the results. In another sensitivity analysis, when studies with a high risk of bias were included in the model, the findings remained consistent, with two exceptions: format (written versus verbal versus both) no longer had a significant effect, but profession of recipient did, with non‐physicians performing better than physicians. It was observed that the model‐based estimated effect sizes increased when the high risk of bias studies were included, suggesting caution is needed when interpreting these results. Given that some of the strata within the model were quite small (e.g. only six comparisons from four studies assessed 'both' goals and action plans), such instability is not surprising.

Exploratory analyses

Exploratory analyses were conducted to examine the importance of context and the complexity of the targeted behaviour on the likelihood that audit and feedback will improve professional practice. Although clinical setting (outpatient versus inpatient versus mixed, other or unclear) was marginally statistically significant in the multivariate meta‐regression model (P = 0.037), the estimated effects were similar across inpatient and outpatient settings (inpatient estimated RD = 7.7%; outpatient estimated RD = 7.1%; mixed, other or unclear estimated RD = 3.0%).

When 'targeted behaviour' (prescribing versus laboratory or radiology utilisation versus diabetes or cardiovascular disease management versus other) was added to the meta‐regression model, it was statistically significant (P < 0.0001), with estimated RD for prescribing (11.1%) larger than diabetes or cardiovascular disease (5.9%), laboratory or radiology testing (4.2%), or other (4.7%). In that model, the 'direction of change required' (increase current behaviour versus decrease versus mix/other) was no longer statistically significant (P = 0.525) and the estimates for some other variables changed (see Table 4). We then conducted meta‐analyses on the subgroups of studies that focused on the targeted behaviours of interest. For prescribing, the weighted median adjusted RD was 13.1% (IQR 3% to 17%) based on 26 comparisons with dichotomous outcomes at unclear or low risk of bias. For laboratory or radiology test utilisation, the weighted median adjusted RD was ‐0.1% (IQR ‐0.1% to 6.5%) based on three comparisons, and for trials focusing on the management of diabetes or cardiovascular disease, the weighted median adjusted RD was 0.5% (IQR ‐0.5% to 3.4%) based on 14 comparisons.

3. Exploratory analysis: meta regression with targeted behaviour.

| Characteristic of the Feedback or Recipient or Trial | Effect | |

| Type of professional practice | P < 0.001 | |

| Diabetes/CVD | 5.91 | |

| Laboratory testing/radiology referrals | 4.21 | |

| Prescribing | 11.11 | |

| Other | 4.71 | |

| Format of feedback | P < 0.001 | |

| Verbal | 2.42 | |

| Written | 5.86 | |

| Both verbal and written | 10.07 | |

| Not clear | 7.60 | |

| Source of feedback | P < 0.001 | |

| A supervisor or colleague | 13.71 | |

| A 'professionals standards review organization' or employer | 2.44 | |

| The investigators | 4.95 | |

| Not clear | 4.85 | |

| Frequency of feedback | P = 0.002 | |

| Frequent (up to weekly) | 3.09 | |

| Moderate (up to monthly) | 9.58 | |

| Infrequent (less than monthly) | 6.28 | |

| Once only | 3.59 | |

| Unclear | 9.89 | |

| Instructions for improvement | P < 0.001 | |

| Explicit, measurable target/goal, but no action plan | 2.84 | |

| Action plan | 9.30 | |

| Both | 7.18 | |

| Neither | 6.63 | |

| Direction of change required | P = 0.525 | |

| Increase current behaviour | 6.64 | |

| Decrease current behaviour | 7.13 | |

| Change behaviour or mix or unclear | 5.70 | |

| Baseline performance | P = 0.002 | |

| at 25% | 8.72 | |

| at 50% | 6.75 | |

| at 75% | 4.77 | |

| Profession of recipient | P = 0.059 | |

| Physician | 5.04 | |

| Non‐physician | 7.94 | |

| Risk of bias | P = 0.454 | |

| Low risk of bias | 5.88 | |

| Unclear | 7.09 | |

| High risk of bias (not included in primary analysis) | n/a | |

Comparison B. Audit and feedback alone compared to no intervention

A total of 82 comparisons from 65 studies were included in this comparison. Nine comparisons from six trials did not report baseline data and 13 comparisons from 10 trials assessed patient outcomes as a primary outcome, leaving 59 comparisons from 48 studies for the analyses.

For studies with audit and feedback alone targeting professional practice with dichotomous outcomes, there were nine comparisons from seven studies excluded due to high risk of bias, leaving 32 comparisons from 26 studies for the primary analysis. These studies included 759 groups of health providers (from 12 cluster trials) and 1617 health professionals (from 14 trials allocating individual providers). The weighted median adjusted RD was 3.0% (IQR 1.8% to 7.7%). Including the studies at high risk of bias resulted in no change to the estimate of effect.

For studies with audit and feedback alone targeting professional practice with continuous outcomes, there were five comparisons from four studies excluded due to high risk of bias, leaving 14 comparisons from 13 studies for the primary analysis. These studies included 348 groups of health providers (from eight cluster trials) and 494 health professionals (from five trials allocating individual providers). The weighted median adjusted change relative to baseline control was 1.3% (IQR 1.3% to 11.0%). Including the studies at high risk of bias studies in the sensitivity analysis also resulted in a weighted adjusted change relative to baseline control of 1.3% (IQR 1.3% to 20.1%).

Comparison C. Audit and feedback as the core feature of a multifaceted intervention compared to no intervention

A total of 90 comparisons from 65 studies were included in this comparison. Seven comparisons from six trials did not report baseline data and 13 comparisons from nine trials assessed patient outcomes as a primary outcome, leaving 70 comparisons from 50 studies for the analyses.

For studies with multifaceted interventions featuring audit and feedback targeting professional practice with dichotomous outcomes, there were seven comparisons from seven studies excluded due to high risk of bias, leaving 50 comparisons from 32 studies for the primary analysis. These studies included 1574 groups of health providers (from 26 cluster trials) and 480 health professionals (from seven trials allocating individual providers). The weighted median adjusted RD was 5.5% (IQR 0.4% to 16%). Including high risk of bias studies in the sensitivity analysis resulted in a revised weighted adjusted RD = 6.5% (IQR 0.5% to 16%).

For studies with multifaceted interventions featuring audit and feedback targeting professional practice with continuous outcomes, there were 12 comparisons from 11 studies for the primary analysis. These studies included 317 groups of health providers (from seven cluster trials) and 111 health professionals (from four trials allocating individual providers). The weighted median adjusted change relative to baseline control was 26.1% (IQR 12.7% to 26.1%). There were no studies in this group with high risk of bias.

Comparison D. Different ways of providing audit and feedback (head‐to‐head comparisons)

Seventeen trials included 16 head‐to‐head comparisons of different ways of providing audit and feedback. For each comparison, we determined the adjusted RD or the adjusted change relative to baseline control. This is reported below in addition to any statistical comparisons conducted by the authors of a particular study (e.g. odds ratios or P values) to provide a standard measure of effect across all comparisons in this review.

Peer comparison

Søndergaard 2002 and Wones 1987 each found small differences when adding peer comparison data to the audit and feedback for asthma management (adjusted RD = 2%) or inpatient laboratory test utilisation (adjusted change relative to baseline control = 5%), respectively. Kiefe 2001 compared audit and feedback featuring a mean score of peers with feedback that featured an “achievable benchmark” (the mean score of the top 10% of peers). They found that the achievable benchmark group improved quality of care for diabetic patients (median adjusted RD = 3%, IQR = 2% to 4%). In particular, statistically significant increases were observed for influenza vaccination (OR 1.54, 95% CI 1.26 to 1.96), foot examination, (OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.69) and haemoglobin A1C measurement (OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.69), while cholesterol measurement (OR 1.20, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.51) and triglyceride measurement (OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.44) had non‐statistically significant increases. In contrast, Schneider 2008 found that identifying top performers in feedback presented in a quality circle (i.e. learning collaborative) did not lead to improvements in management of asthma (adjusted RD = ‐5%, high risk of bias).

Presentation of feedback and inclusion of additional information

Mitchell 2005 found that feedback was slightly more effective for control of blood pressure if it presented information in a way that identified patients at higher risk, suggesting that action for such patients should be prioritised (adjusted RD = 2%; OR 1.72, 95% CI 1.09 to 2.70). (This is a ‘patient’ outcome due to the role of patient‐specific factors in achieving control of hypertension. Larger effects on professional practice outcomes might be expected.)

Two studies directly compared including a small amount of extra information to not including that information. Buntinx 1993 added brief advice to typical feedback. They found similar effects for the quality of pap smears (adjusted RD = 1%; no statistical test reported for this comparison). Curran 2008 added ‘Pareto’ and ‘cause and effect' charts’ to help recipients identify barriers and focus improvement efforts. They did not find a statistically significant difference in rates of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in hospital wards (adjusted change = 5%, high risk of bias, patient outcome; P = 0.46).

Two studies tested the type and amount of data used for the feedback reports. Gullion 1988 compared feedback regarding blood pressure laboratory values, and medications from chart audits to feedback regarding blood pressure and adherence to medication and lifestyle recommendations from patient surveys. They reported no differences in blood pressure control (adjusted RD = 2%, patient outcome; no P value reported for this comparison). Herrin 2006 compared feedback based on administrative data to this plus additional, patient‐specific clinical data from medical records. They also did not find a statistically significant difference in the proportion of adequate glucose control (adjusted RD = 1.9%, patient outcome; P = 0.97).

Source and delivery

Four studies directly tested whether feedback should be delivered by mail (written) or in‐person (verbally). Rubin 2001 compared written feedback delivered only to the hospital administration with the addition of verbal feedback at staff meetings. They did not find a difference in appropriateness of red blood cell transfusions (adjusted RD = ‐2%; no statistical test reported for this comparison). Sauaia 2000 found differences that were not statistically significant between verbal feedback in a large group setting by an expert cardiologist and written feedback for improving eight quality of care outcomes related to acute management of myocardial infarction (median adjusted RD = 7%; P value for each outcome > 0.05). Batty 2001 compared similar interventions for in‐hospital benzodiazepine prescriptions. The verbal presentation was more effective than the written feedback (adjusted RD = 24%, high risk of bias). Finally, Anderson 1994 found little or no difference when they compared feedback given to large groups as part of a CME (continuing medical education) program, with and without sending individualised feedback reports to participants for prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism (adjusted RD = 0%; no P value reported for this comparison).

Two studies directly tested the effects of who delivered the feedback. Ward 1996 compared audit and feedback delivered by a physician‐peer with audit and feedback delivered by a nurse. They found that peer‐physician feedback led to non‐statistically significant improved management of diabetes (adjusted change relative to baseline control = 12%; P value reported as “NS”). They also noted that the physician interviews were longer (25 minutes versus 14 minutes; P < 0.001) and that there was a significant variation in effect size across the different physicians providing the outreach. Similarly, Van den Hombergh 1999 found that mutual feedback by physician‐peers (ie. each physician provides and receives feedback in turn) improved outcomes as measured by 33 indicators of practice management compared with unidirectional feedback by a non‐physician (median adjusted RD = 5%; no overall statistical test reported).

Recipient participation

Two studies directly tested the role of recipient participation. Sommers 1984 found that participation in criteria setting prior to the feedback resulted in worse management of anaemia in hospitalised patients (adjusted RD = ‐21%, high risk of bias; OR = ‐3.36, P = 0.002). Conversely, Brady 1988 found that when resident physicians conducted a self‐audit at baseline, it led to improvements compared with simply receiving the data for mammographic screening rates (adjusted RD = 8%; no OR reported, P value reported as < 0.05) but not to a statistically significant improvement for influenza vaccination rates (adjusted RD = 1.5%; no OR reported, P = 0.17).

Comparison E. Audit and feedback combined with complementary interventions compared to audit and feedback alone

Fifty‐three comparisons from 43 trials were included. Below, the results of these comparisons are summarised within categories related to the 'type' of intervention that audit and feedback was combined with when comparing to audit and feedback alone. We acknowledge that some of the multifaceted interventions may fit into multiple categories, but only describe the findings from each trial once. Multi‐arm studies may be described in multiple sections corresponding with the type of comparison. Due to the variation in outcome type (dichotomous, continuous, patient, provider) across the studies, we were unable to conduct quantitative meta‐analyses, with the exception of trials comparing audit and feedback with educational outreach to audit and feedback alone (see below). For each comparison, we determined the adjusted RD or the adjusted per cent change relative to baseline performance in the audit and feedback alone arm. This is reported below in addition to any statistical comparisons conducted by the authors of a particular study (e.g. odds ratios or P values) to provide a standard measure of effect across all comparisons in this review.

Audit and feedback with reminders compared to audit and feedback alone