Abstract

Photosynthesis converting solar energy to chemical energy is one of the most important chemical reactions on earth. In cyanobacteria, light energy is captured by antenna system phycobilisomes (PBSs) and transferred to photosynthetic reaction centers of photosystem II (PSII) and photosystem I (PSI). While most of the protein complexes involved in photosynthesis have been characterized by in vitro structural analyses, how these protein complexes function together in vivo is not well understood. Here we implemented STAgSPA, an in situ structural analysis strategy, to solve the native structure of PBS–PSII supercomplex from the cyanobacteria Arthrospira sp. FACHB439 at resolution of ~3.5 Å. The structure reveals coupling details among adjacent PBSs and PSII dimers, and the collaborative energy transfer mechanism mediated by multiple super-PBS in cyanobacteria. Our results provide insights into the diversity of photosynthesis-related systems between prokaryotic cyanobacteria and eukaryotic red algae but are also a methodological demonstration for high-resolution structural analysis in cellular or tissue samples.

Subject terms: Cryoelectron tomography, Photosynthesis, Bioenergetics

The authors solved the native structure of cyanobacterial PBS–PSII supercomplex at a resolution of 3.5 Å via STAgSPA strategy, revealing the association details and possible energy transfer pathways between PBS and PSII.

Introduction

In oxygenic photosynthetic organisms, the light-driven reactions depend on the cooperation of different multiprotein complexes that are attached to or embedded in thylakoid membranes, such as antenna systems, photosystems II/I (PSII/PSI) and cytochrome b6f (Cyt b6f)1,2. In cyanobacteria, sunlight is harvested by the soluble light-harvesting apparatus, phycobilisomes (PBSs), and the energy is finally transferred to the reaction centers of PSII/PSI to induce photo-induced electron transport3,4. The structures of isolated PBS, PSII, and PSI have been determined individually by cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) single-particle analysis (SPA) at near-atomic resolution5–8, providing the structural basis for energy transfer, electron transfer, and photoprotection within the isolated complexes. However, it is hard to obtain intact assemblies of these protein machinery by SPA due to their diverse protein properties, which may result in the dissociation of some loosely associated supercomplexes during purification. Previously, the cross-linking coupled with mass spectrometry analysis has identified some potential interaction sites of PBS–PSII–PSI megacomplex9. The low-resolution negative-staining PBS–PSII and PBS–CpcL–PSI structures also indicate the coarse binding patterns between PBS and PSII/PSI in cyanobacteria10,11. However, the exact interactions and energy transfer pathways of PBS–PSII/PSI at their native state remain elusive.

Cryo-electron tomography (Cryo-ET) coupled with subtomogram averaging (STA) is emerging as a potent methodology for addressing target particles in the cellular environment, which has been applied to visualize the arrangement of PBSs, PSII, or ATPase in thylakoid membranes12,13. Although some complexes, i.e., ribosomes14, cilia15, and filaments16, have been solved at pseudo-atomic resolution via the standard cryo-ET-STA procedure, challenges still remain due to a series of limiting factors, including the limited amount of collected data, low signal-to-noise ratio, inaccurate tilt-series alignment, etc. Thus, the utilization of the typical pipeline of cryo-ET-STA only provides the cellular-scale observation of the binding of the PBS and PSII dimer with stoichiometry 1:1 from cyanobacteria Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 without structural detail13. Recently, SPA was also applied to in situ structural analysis through a high-resolution template matching procedure (isSPA), which has emerged as an alternative approach and has successfully solved several structures at near-atomic resolution17–21. However, a prerequisite that a high-resolution template is needed for particle detection significantly limits the application prospects of this method. To overcome these challenges, we have developed an in situ structural analysis strategy that combines cryo-ET-STA and SPA techniques to determine the structures in the cellular context, termed subtomogram averaging guided single-particle analysis (STAgSPA). We have successfully applied this strategy to solve the structure of the PBS–PSII–PSI–LHC megacomplexes from red alga Porphyridium purpureum at an overall resolution of 3.3 Å22, which reveals the association and bilin distribution among PBS, PSII, and PSI of red algae. Since native photosynthetic apparatuses are compositionally and structurally diverse, structural analysis of other species is also essential for a comprehensive understanding of their working mechanisms.

Herein, we employed cryo-focused ion beam (cryo-FIB) milling and the STAgSPA method to address the in situ structure of the cyanobacterial PBS–PSII supercomplex from Arthrospira sp. FACHB439 (hereafter Arthrospira FACHB439), a more challenging sample due to the relatively smaller size and more flexible property of cyanobacterial PBS compared to the red algal PBS. We determined the structure at a resolution of ~3.5 Å, demonstrating the powerful capability of the STAgSPA strategy to deal with complicated samples. The structure reveals details concerning the specific interactions between PBS and PSII in cyanobacteria, and pigment networks that contribute to energy transfer. Moreover, we conducted a comparative analysis between the prokaryotic cyanobacterial PBS–PSII supercomplex and the eukaryotic red algal PBS–PSII module reported recently22, aiming to elucidate both their shared characteristics and distinctive individual features. This investigation provides insights into the evolutionary perspective of light energy capture and transfer in photosynthetic organisms.

Results and discussion

Determination of cyanobacterial PBS–PSII by optimized STAgSPA

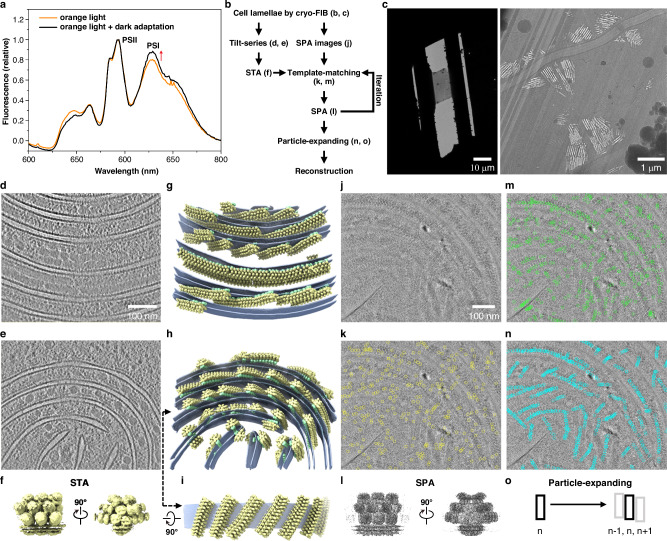

The cyanobacterium Arthrospira FACHB439 was cultured under continuous low orange light followed by a 20-min dark adaptation period to induce the proximity of PBS and PSI23 (Fig. 1a). This condition was employed to facilitate subsequent structural analysis. Our prior success in studying the structure of red algal PBS–PSII–PSI–LHC megacomplexes with STAgSPA prompted us to apply the same strategy to cyanobacterial PBS-photosystem supercomplex. However, due to smaller and more flexible PBS in cyanobacteria, specific optimizations were implemented (Fig. 1b). Similar to the red alga, we collected two types of data from lamellae for the cyanobacteria (Fig. 1b, c), tilt-series and high-dose zero-tilt images (SPA images). Cryo-ET reconstruction was then performed (Fig. 1d, e), followed by STA that yielded an intermediate-resolution structure of the PBS–PSII complex (10 Å) (Fig. 1f) and also revealed the distribution characteristics of the target (Fig. 1g–i). Subsequently, this PBS–PSII structure, with the PSII region masked out, served as a reference for the high-resolution template matching to detect 2D particles in SPA images (Fig. 1j, k). The reconstruction of these particles showed extra density of the membrane region including PSII and an increase in the overall resolution (6.5 Å) (Fig. 1l and Supplementary Fig. 1). Different from the data processing for the red alga, where a single round of particle detection using the STA map sufficed, here we re-detected particles using the refined PBS–PSII structure from SPA as an updated reference to acquire more suitable particles for the analysis. Indeed, this step significantly increased the number of identified particles (Fig. 1m). Furthermore, leveraging the geometric relationships derived from cryo-ET distribution information allowed us to infer the presence of unpicked particles. We then employed a particle-expanding step, where particle coordinates were shifted based on the spatial positions of nearby PBS particles (Fig. 1n, o). These two additional steps—re-detecting particles with a higher-resolution reference and expanding particles based on spatial proximity—maximized the number of valid particles, ensuring a final high-resolution reconstruction at ~3.5 Å (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Overview of the STAgSPA workflow.

a Low temperature (77 K) fluorescence emission spectra of Arthrospira platensis cells cultured under orange light and orange light plus dark adaptation. The excitation wavelength was 580 nm. Three times experiments were repeated independently. b A succinct flowchart of the optimized STAgSPA strategy used in the determination of the in situ structure of the cyanobacterial PBS–PSII supercomplex. c Representative TEM images of lamellae at low magnification (left) and media magnification showing the thylakoid membrane in cells (right). d, e Slices of two tomograms reconstructed from cryo-ET. f An intermediate resolution structure of the PBS–PSII supercomplex revealed by cryo-ET-STA. g, h Mapping of STA results (f) back to the corresponding tomograms (d, e), illustrating their 3D positions and orientations. PBSs and PSII dimers are distinguished in yellow and light green, respectively. The thylakoid membrane is depicted as transparent sky-blue layers. i A rotated perspective of a membrane segment extracted from (h), displaying the upper surface of the PBS arrays. j A representative SPA image. k Results of particle picking (yellow circles) using the STA map (f), with the PSII region masked out, served as the reference for the high-resolution template matching. l The SPA reconstruction from first-round picked particles. m Results of particle picking (green circles) using the SPA map (l) as the reference. n Retention of particles after particle-expanding and removal of overlaps, indicated by blue circles. o The particle-expanding step is used to infer unpicked particles.

It should be noticed that while both a single-particle cryo-EM structure and an STA structure served as effective references for the high-resolution template matching for red algae18, using the homologous single-particle structure24 of cyanobacterial PBS failed to generate a reconstruction with the expected PBS shape. To investigate this discrepancy, we conducted a comparative test using five different references including our SPA map obtained from the first round of particle-picking (6.5 Å), our intermediate-resolution STA map (10 Å), a low-resolution STA map from a related species (24 Å)13, a simulated map (3.3 Å) from the homologous PBS model24, and a simulated map (3.3 Å) built by fitting three homologous PBS models into the 24 Å STA map13 (Supplementary Fig. 3a). The results indicate that our STA map outperforms other options, except for our SPA map, as evidenced by the much more valid particles (Supplementary Fig. 3b). The 6.5 Å SPA map and the 24 Å STA map show the highest and lowest valid particle numbers, respectively, suggesting that high-resolution structural features are crucial for the particle detection. Moreover, the relatively high mismatch (low ratio of valid particles to detected particles) observed in the two simulated maps could be attributed to structural variations across species or experimental conditions, or inaccuracies in imaging parameters like pixel size. An STA map generated from the same sample as that used in the SPA under identical imaging conditions eliminates these discrepancies, thereby delivering superior performance. Taken together, these results demonstrate the power of cryo-ET-STA as an initial guide for particle detection in SPA, especially for targets lacking a high-resolution model. Therefore, the STAgSPA strategy could overcome the inherent limitations of standalone cryo-ET-STA or isSPA methods17,18, propelling in situ structural analysis to a high-resolution frontier.

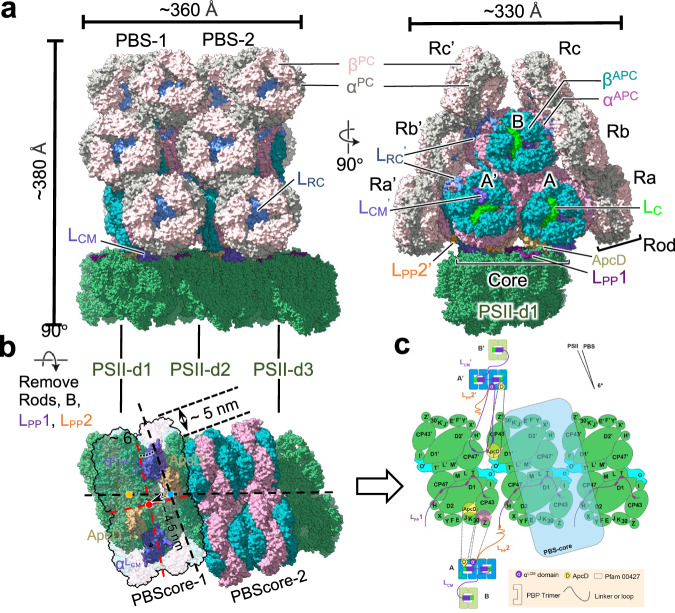

The overall structure of cyanobacterial PBS–PSII supercomplex

The overall structure of cyanobacterial PBS–PSII supercomplex has dimensions of approximately 360 × 330 × 380 Å3 with a total mass of approximately 7.6 MDa (Fig. 2a). The structure shows that two face-to-face stacked PBSs (labeled as PBS-1 and PBS−2) are anchored to three PSII dimers (PSII-d1, -d2 and -d3), and repeat periodically along the PSII array of thylakoid membrane (Fig. 2a–c). Each PBS spans two PSII dimers with an angle of 6° between the hemi-discoidal plane of the PBS core and the central plane of the PSII dimer pair. Although both PBS and PSII dimers are C2 symmetrical structures individually, their symmetry axis is misaligned when associated with the PBS–PSII supercomplex, and the PBS center is offset by nearly 4.5 nm relative to the PSII dimer pair center (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 4). These result in the non-symmetric fashion of the PBS–PSII supercomplex, therefore the two pairs of terminal emitters of each PBS, ApcD/ApcD’, and LCM/LCM’, contact with PSII dimers in different manners. Moreover, two adjacent PBS cores show parallel-displaced organization with a ~5 nm shift along the PBS array (Fig. 2b). Notably, red algal PBS–PSII exhibits a larger rotation angle (~14°) but no PBS core offset relative to the PSII dimer pair22,25, leading to the red algal PBSs are attached to the PSII in isolation, lacking sufficient connection between each other. It suggests that the PBS–PSII supercomplex from the prokaryotic cyanobacteria may have distinctive strategies for association and energy transfer pathways between PBS and photosystems (described below).

Fig. 2. Overall structure of PBS–PSII supercomplex from Arthrospira FACHB439.

a Overall structure of cyanobacterial PBS–PSII is shown as a surface representation. The key subunits are color-coded as indicated. b The top view of the PBS–PSII supercomplex shows that the PBS core plane rotates approximately 6° along the face plane of the PSII dimers. The centers of the PBS core and PSII-d1 and -d2 shift approximately 4.5 nm. The PBS-1 and -2 shift approximately 5 nm. The symmetry axis of PBS and PSII dimer, as well as the central section of PSII dimer pair, are represented in red, orange, and blue points. c Schematic model of the PBS–PSII architecture in top view, showing the components and connections of PBS and PSII. Transmembrane subunits are shown in PSII dimers. PSII dimer array displays the interaction between adjacent PSII dimers through PsbO. PSII dimers 1 and 2 display the interactions between PBS and PSII mediated by LPP1, LPP2, LCM-PB loop, and ApcD.

To analyze the spatial distribution of the PBS–PSII supercomplex on the native thylakoid membrane, the subtomogram maps were placed back into the original tomograms. Unlike red algae where PBSs are closely sandwiched between parallel thylakoid membranes and adjacent PBSs anchor to the upper and lower membranes in opposite orientations22,25, there is sufficient free space between the cyanobacterial PBS–PSII arrays, providing convenience for the movement of the PBS–PSII arrays along the membrane (Fig. 1g–i). Low temperature (77 K) fluorescence spectroscopy provides clear and more distinct fluorescence signals from the photosynthetic systems. In this study, a significant increase in PSI fluorescence at 730 nm under orange light and dark adaptation compared with orange light is observed, suggesting that there might be a considerable number of PBSs close to PSI26 (described in “Methods”) (Fig. 1a). Obvious gaps are observed between two adjacent PSII arrays on the membranes in the tomograms (Fig. 1i). According to the atomic force microscope (AFM) topographs27,28, some unidentified densities in the gaps could be other membrane-spanning complexes such as PSI, NADH dehydrogenase-like (NDH) and Cyt b6f. Unfortunately, we did not observe PSI density in the reconstructed EM map. This situation is different from that of red algae, where two PSI subcomplexes are connected to two ends of the PSII array22. This is likely reasonable because AFM observation corroborated that PSII arrays are interspersed with PSI, which exhibits diverse interaction patterns and inhomogeneous arrangement in native thylakoid membranes27,28. We also identified 180 phycocyanobilin (PCB) for each PBS, 70 chlorophylls, 4 heme molecules, 18 carotenoids, and 56 lipids for each PSII dimer. All pigments are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

In situ structure of cyanobacterial PBS and super-PBS

The in situ PBS structure of Arthrospira platensis has a typical hemi-discoidal morphology with a triangular core consisting of a top cylinder B and two basal cylinders A and A’ and six phycocyanin (PC) rods surrounding the core (Fig. 2a), which is consistent with the published cryo-EM structures of PBS from other cyanobacterial species6,24,29,30. However, the densities of rods, especially the peripheral rod hexamers, cannot be solved well because cyanobacterial rods are mobile and may be able to switch conformation31 (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). There is only one type of rod-core linker protein (LRC) for the PBS of A. platensis. LRC contains a conserved N-terminal Pfam00427 domain located in the cavity of the PC hexamer proximal to the core, and a C-terminal domain (CTD) protruding out of the central cavity of rod hexamer and latching onto the lateral grooves formed by α and β subunits of core cylinders forming several binding belts, similar to that in the published cyanobacterial PBS structures via in vitro SPA6,24 (Supplementary Fig. 5c). In addition, the structure reveals that a short tail of LRC CTD (R230 to L240) extends from the lateral grooves to the front surface, serving as a buckle to stabilize and strengthen the stacking of PBS core layers, which may contribute to energy migration between adjacent PBSs (described below) (Supplementary Fig. 5d, e).

PBSs have been demonstrated to arrange into linear rows on the stromal side of PSII with the cores stacked tightly in a face-to-face manner13,24,32. However, the proposed PBS array model is inaccurate due to the limitation of the low resolution (~24 Å) of the in situ PBS arrays. In this study, we found the approximately 5 nm shift between two adjacent PBS cores (Fig. 2b) and the slight twist (~25.3°) between two basal cylinders (Supplementary Fig. 5f), thereby the hexamers from adjacent cores are positioned with corresponding displacements. Interestingly, the offset of 5 nm is about the same as the radius of the hexameric ring, which ensures that there are still certain interfaces between the two adjacent cores. In detail, the interactions between the core layers B1’/A1/A4’ and B1/A4/A1’ are formed by several hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) between the outermost trimeric β layers (Supplementary Fig. 6). Moreover, cyanobacterial LCM has evolved an extra loop region (D527 to K550) extending to the central cavity of core A1 layer (Supplementary Fig. 7a–c). We found that this loop bound to A1 layer and LC via 7 H-bonds (D527–R107/β2A1, D527–Q23/LC, S535–T28/LC, N540–D105/β2A1, K541–S118/β1A1, N544–Q2/β2A1, and G546–R77/β1A1), which further stabilizes the conformation of A1 layer (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). The binding belts and the short buckles formed by LRC CTDs are also involved in the compact assembly of PBS (as mentioned above) (Supplementary Fig. 5d, e). All these lead to the dense face-to-face packing of PBSs with the bilin distances between adjacent PBSs in~30 Å (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Such a tightly stacked arrangement of PBSs may function as super-PBS in which the excitation energy flow could propagate across the adjacent PBSs along the PBS rows (described below).

The binding mechanism of PBS with PSII in cyanobacteria

In the PBS–PSII supercomplex structure, we clearly resolved the loop of the phycobilin-binding domains (PB domain) of LCM (PB-loop/LCM), which was absent in the published in vitro PBS structures (Supplementary Fig. 7d, e).

As mentioned above, LCM and LCM’ have different modes of interaction with PSII. LCM interacts with PSII-d1 via αLCM rather than through the PB-loop (Fig. 3a–c), while LCM’ uses PB-loop’ to contact with both PSII-d1 and PSII-d2 through H-bond interactions of D118, N119, and D134 of PB-loop’ with R476/PSII-d1CP47’, K227/PSII-d1CP47’, and Y130/PSII-d2CP43’, and through T-shaped π–π interaction of its aromatic residue F132 with F133/PSII-d2CP43’ (Fig. 3d, e). The sequence alignment of PB-loop in different cyanobacteria shows that the key residues D118 and F132 maintain the corresponding amino acid properties, indicating that PB-loop may mediate the association between PBS and PSII via some key residues in cyanobacteria (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Similarly, ApcD and ApcD’ have different contacts with PSII dimer. ApcD interacts with D2 of PSII-d1 through several electrostatic interactions, while ApcD’ binds with PSII dimer through a H-bond (Fig. 3f, g).

Fig. 3. Interactions of PBS with PSII tetramers.

a Different views of interactions between PBS and PSII tetramers. LCM (LCM’), ApcD (ApcD’), and LPP2 (LPP2’) of PBS and LPP1 of PSII dimers are highlighted. The transmembrane subunits involved in the interactions are shown as cartoons. b Enlarged views showing LCM binds to only PSII-d1 (left panel), while LCM’ binds to both PSII-d1 and -d2 (right panel). PB-loop/LCM (PB-loop’/LCM’) is shown as surface representation in 60% transparency. c, d Details of the interactions of LCM (c) and LCM’ (d) binding to PSII subunits. The residues involved in the interactions are shown as stick representations. e, f Interactions of ApcD (e) and ApcD’ (f) with PSII dimers. The enlarged view of e shows the electrostatic interaction between the ApcD and the D2 subunit of PSII-d1. g, h Different views showing the position of LPP2 and the interaction between LPP2 and LPP1 of PSII-d2. The positively charged residue K150 of LPP2 is labeled.

Sequence alignment of ApcD shows that these charged residues are mostly conserved in different cyanobacteria, suggesting that ApcD from different cyanobacteria may contact with PSII in a similar interaction manner (Supplementary Fig. 8b). Previously, some potential interactions have been identified between PBS and two photosystems from cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803 by in vivo protein cross-linking analysis9. Comparison of the PBS–PSII interactions with our structure suggests that the cross-link K87/PB-loop–K227/CP47 is reasonable, while the other cross-linking sites of PBS (K317/LCM, K523/LCM, and K584/LCM) are far away from the surface of PSII, which could not be involved in the association between PBS and PSII (Supplementary Fig. 9). The PBS–PSI cross-linking sites, K18/ApcB, K58/ApcB, K48/ApcD, and K49/ApcD, are located above the inner side of PSII surface in our structure, where there is no space to accommodate PSI (Supplementary Fig. 9). Given that this PBS–PSII structure is only one stable state in cells, it could not be excluded the possibility of direct interaction between PBS and PSI. In addition to LCM and ApcD, a homolog of linker 2 of PBS and PSII (LPP2) of the red algal PBS22 was found in the in situ structure of the Arthrospira FACHB439 PBS, and also named LPP2 (Supplementary Fig. 10a-e). Using its C-terminus LPP2 has a slight contact with the N-terminus of the linker 1 of PBS and PSII (LPP1), a component of PSII dimers (discussed later), via a conserved positively charged residue K150 (Fig. 3h, i and Supplementary Fig. 10f, g). Given that the complete LPP2 has not been solved yet, it could not be excluded that its N-terminal region has a direct interaction with PSII. However, even if this interaction exists, it may be transient and unstable in Arthrospira FACHB439. Together with other possible factors, such as the resolution limitation, dynamic coupling, etc., we could not obtain the complete structure of LPP2. By contrast, the red algal LPP2 forms a stable interaction with the CNT subunit of PSII dimer directly by its N-terminal loop, exhibiting a much stronger binding between PBS and PSII than cyanobacteria22. Since the interaction forces between PBS and PSII are mainly attributed to several polar interactions provided by loop regions of the PBS–PSII interface, and no complete linker ties PBS and PSII together, the coupling between cyanobacterial PBS and PSII seems weak and unstable in vivo33,34. It is quite different from red algal PBS–PSII, where PBS is tightly bonded on the PSII surface by four PBS–PSII linker proteins (LRC2, LRC3, LPP2, and LPP1), as well as LCM and ApcD22. This may provide a structural basis for the diffusion movement of cyanobacterial PBS on the surface of the thylakoid membrane observed by fluorescence spectra35.

Structure of cyanobacterial PSII and interaction pattern

Similar to the published cryo-EM structure of cyanobacterial PSII, the in situ structure of Arthrospira FACHB439 PSII monomer consists of 17 core subunits (PsbA (D1), PsbB (CP47), PsbC (CP43), PsbD (D2), PsbE, PsbF, PsbH, PsbI, PsbJ, PsbK, PsbL, PsbM, PsbT, PsbX, PsbY, Psb30, and PsbZ) and 4 extrinsic subunits (PsbQ, PsbO, PsbU, and PsbV) (Supplementary Table 1). Notably, we observed a previously undetected density that attached on the stromal side of PSII (Fig. 4a). Because the PSII-binding position of this density is similar to that of the red algal LPP122, it may be a homolog of the red algal LPP1 and is also named LPP1 here. Unfortunately, the sequence of LPP1 could not be identified in our structure, so it is modeled as poly-Ala residues. LPP1 contains an N-terminal LPP2-binding motif (A1–A9) followed by a PSII-binding motif (A10–A47), which attaches to the PSII surface through binding with D1, D2, CP43, CP47, PsbT, and PsbH by electrostatic interactions (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 11a–c). Remarkably, only one monomer of the PSII dimer has the LPP1 protein attached, as the corresponding site for LPP1 binding on the other monomer is occupied by a segment of the PB-loop/LCM. The asymmetric distribution of LPP1 may be one of the reasons for the PBS–PSII asymmetric fashion. However, given that the interaction between LPP1 and PBS is very weak (Fig. 3h, i), this effect seems negligible. Actually, this segment shares a highly similar structural feature and the PSII binding pattern with LPP1 (Supplementary Fig. 11d). Notably, the C-terminus of the red algal LPP1 (PBS-core-binding motif) is embedded into the groove of LCM to tie PBS and PSII tightly22, while only PSII-binding motif is resolved in cyanobacterial LPP1. This is because the outermost APC_β trimers of cylinder core A /A’ occupy the binding site, therefore the C-terminus of cyanobacterial LPP1 may be unstable and unresolved (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 4. Interaction pattern between PSII dimers.

a The interaction pattern of PSII dimers from the side view (upper) and the bottom view (lower). LPP1, PsbO, and PsbO’ are shown as surface representations and colored in purple, dodger blue, and cyan, respectively. b The diagram of structural elements of LPP1 (upper panel) is shown above the atomic model (middle panel). Lower panel: top view of the stromal side of PSII showing that LPP1 spans on the stromal surface of one PSII monomer created by transmembrane helices of D1, D2, CP43, CP47, PsbH, and PsbT. The N- and C-terminal residues of LPP1 are colored in red. c Close-up view of the interaction between PsbO molecules from adjacent PSII dimers. The residues involved in the interaction are shown as stick representations.

In addition, structural analysis shows that adjacent PSII dimers are associated only via two PsbO subunits on the lumen side (Fig. 4a). Two conserved charged residues R55 and E241 of PsbO interact with E241’ and R55’ of PsbO’ forming salt bridges (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 8c). Besides, two conserved polar residues T168/PSII-d1PsbO’ and S229/PSII-d1PsbO’ are also contributed to the connection of PSII dimers through forming H-bonds with T168/PSII-d2PsbO and R55/PSII-d2PsbO (Fig. 4c). According to our structure, under low light intensity culture condition, most, if not all, cyanobacterial PSIIs are almost stably arranged in long parallel rows in vivo, therefore PsbO mediated interactions seem to be the crucial factors for the array layout of PSII dimers.

Multiple super-PBS mediated energy transfer pattern

As mentioned above, cyanobacterial PBSs are closely stacked against one another, forming a super-PBS organization, in which the excitation energy flow could propagate across the adjacent PBSs (Fig. 2a). Several bilin pairs of the super-PBS, having short distances between two neighboring PBS layers, are possibly key bridges in the energy transfer across the interface (Supplementary Fig. 6b). It should be noted that terminal emitters (A4αApcD/A4αApcD’ and A3αLCM/A3αLCM’) are located in the layer A3/A3’ and A4/A4’ of PBS core, thus the energy from layer A1/A1’ will have to travel across layer A2/A2’ to reach the terminal emitters within one PBS core. However, in the super-PBS layer, A1/A1’ from one PBS becomes a neighbor to the layer A4/A4’ from the other PBS, which could deliver the energy from layer A1/A1’ directly to the terminal emitters A4αApcD/A4αApcD’ of neighbor PBS. Based on these data, we speculate that the cyanobacterial super-PBS might increase the energy transfer efficiency by coupling pigments of adjacent PBSs.

Terminal emitters of PBS could converge the energy absorbed by PBS and further transfer it to PSII7,9,24. Owing to the rotation and shift between PBS and PSII dimers (as mentioned above), the distances from four terminal emitters, A4αApcD, A4αApcD’, A3αLCM and A3αLCM’, to the nearest chlorophylls in PSII are different, which leads to an asymmetry in the energy distribution to two PSII monomers (Fig. 5a). Similar to red algal PBS–PSII supercomplex, several aggregated chlorophylls of CP43 (CP43’) and CP47 (CP47’) form the displaced-parallel Chls clusters, prompting the delocalization of π system and downgrade the energy level22 (Fig. 5b, c). They are considered the key mediators of energy transfer from PBS to P68036 (Fig. 5a). Notably, the energy could be transferred from adjacent PBSs to PSII dimers due to the formation of the super-PBS array. Taking PSII-d2 as an example, A4αApcD, A3αLCM, and A3αLCM’ of PBS-1 could also deliver the energy to P680’ and P680 of PSII-d2, therefore each P680 could accept the excitation energy from two adjacent PBSs (PBS-1 and PBS-2) (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5. Key pigment arrangements and possible energy transfer pathways.

a Distribution of key pigments and possible energy transfer pathways in PBS–PSII supercomplex from the top view normal to the membrane plane. The key pigments are shown as bold-stick and the π–π distances (Å) for the adjacent pigments are labeled in black. P680 are boxed in oval. The low energy state Chl clusters of PSII are boxed in rectangles. The red arrows indicate the direction of the potential energy transfer from A3αLCM, A3αLCM’, and A4αApcD’ from neighboring PBSs. The densities (mesh) of the representative A4αApcD, A3αLCM, and Chl a from CP43 and CP47, as well as P680 (stick representation), show their conformations. b, c Magnified views of the low energy state Chl clusters of CP43 (b) and CP47 (c).

In conclusion, our STAgSPA, combining the advantages of cryo-ET-STA and SPA, is a practical in situ structural analysis strategy. This strategy has successfully determined the in situ structures of photosystems in both red algae22 and cyanobacteria, providing a useful methodological paradigm for structural analysis in cellular and tissue samples. In addition, the native high-resolution structures of the PBS-photosystems from cyanobacteria and red algae revealed remarkable differences in the association pattern and energy transfer pathways: (1) in red alga P. purpureum, four PBS–PSII linker proteins mediated the tight association between PBS and PSII, while the cyanobacterial PBS–PSII exhibits loose and possibly unstable binding pattern due to the lack of the similar linkers; (2) in red algae, two PSIs are stably associated with PSIIs at both ends of PSII arrays formed by stacked two or four PSII dimers. However, the structure we solved here suggests that cyanobacteria PSII would form long arrays under low light conditions, representing one of the binding states among PBS, PSII, and PSI. Under this state, PSIIs may lack a stable association with PSI; and (3) there is nearly no interaction between adjacent PBSs in red algae, while cyanobacterial PBSs are densely stacked together, forming the super-PBS pattern. Thus, the PSII reaction centers of cyanobacteria could accept the excitation energy from multiple adjacent PBSs, forming the sophisticated pigment networks for the efficient energy transfer from PBS to PSII, which could effectively compensate for the disadvantage of fewer bilins in cyanobacterial PBS compared to red algae22.

Methods

Strains and cultural conditions

Arthrospira FACHB439 was obtained from the Freshwater Algae Culture Collection at the Institute of Hydrobiology, FACHB. Cells were grown in Arthrospira medium at 25 °C and shaken at 150 rpm under continuous low orange light illumination with an intensity of ~10 μmol of photons m−2 s−1, which was provided by LED with wavelength at 625 nm23. The 5-day-old cultures were harvested for experiments.

Seventy-seven Kelvin fluorescence emission spectra

Arthrospira FACHB439 cultured as described above was collected and then kept in the dark for 20 min before fluorescence spectroscopy. Fluorescence emission spectra were recorded by FS5 Spectrofluorometer (Edinburgh Instruments) at 77 K with an excitation wavelength of 580 nm. Cells cultured under low white light (~10 μmol of photons m−2 s−1) were used as the control trial.

Cryo-EM sample preparation and cryo-FIB milling

Cells were preprocessed in the same way as for 77 K fluorescence emission experiments before freezing. Suspended cells (4 µl) were loaded onto the front side of glow-discharged holy-carbon copper grids (Quantifoil R1.2/1.3, 200 mesh), and 2 μl medium was subsequently added to the back side of the grids. The grids were back-side blotted by Leica EM GP2 (Leica Company) for 6 s at 20 °C and 100% humidity, and plunged into liquid ethane at near −183 °C for vitrification. Grids were stored in liquid nitrogen until used for FIB milling. Cryo-FIB milling was performed using a FIB/SEM dual-beam microscope (Aquilos, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Briefly, the cryo-EM grids were clipped into cryo-FIB Autogrids in the liquid nitrogen reservoir, and loaded into the FIB/SEM chamber at ~3 × 10−7 mbar and −190 °C. To reduce sample charging and protect the sample, the surface of samples was sputter coated with a layer of platinum and then deposited organometallic platinum using a gas-injection system (GIS) operated with a 35 s gas injection time before milling at a work distance of 11 mm. The stage was tilted at 22° (milling angle of ~15° related to the EM grid). Micro-expansion joints were milled to release stress in the support film37. Rough milling was performed with the accelerating voltage of the ion beam at 30 kV and a current of 3.0–0.5 nA to produce lamellae with a thickness of ~500 nm. Due to the inherent Gaussian profile of the ion beam, the typical milling scheme causes preferential thinning of the top of the lamella, resulting in uneven thickness of the lamella, therefore an optimization of the milling technique was used in the further polishing step38. In brief, rough-milled lamellae were polished by tilting each side of the lamella 1° towards the ion beam and milling with 50–30–pA. The optimized milling procedure results in final lamellas with homogenous thickness (100–200 nm) across their entire length.

Cryo-ET data collection and tomogram reconstruction

The data collection of the prepared lamellas was performed on a 300 kV Titan Krios EM G3i (Thermo Fisher). TEM images of lamellas at low and media magnifications were presented in Fig.1c. Before data collection, the stage was tilted to +15°/−15° to make the lamella plane approximately perpendicular to the electron beam. Tilt-series were acquired by a K3 Summit direct detector camera (Gatan) at a magnification of 53,000× (equivalent pixel size 1.632 Å) with a post-column Quantum energy filter (Gatan) operated in zero-loss mode and a slit width of 20 eV. Each tilt image was recorded as a super-resolution movie stack containing 15 frames with a total dose of 4.4 e−/Å2. The software SerialEM39 was used to collect the tilt-series with dose-symmetric tilt-scheme40. The tilted images were collected with an angular range from −42° to +42° (related to the lamella plane) and an interval step of 3°. Each tilt series contains 29 images with a total dose of ~130 e−/Å2. The defocus range used in data collection was from −2.5 μm to −5.5 μm.

The movie stacks were corrected for the beam-induced motion by using MotionCor241 and summed into images with a binned factor of 2. Images of each tilt series were then merged into the stack and aligned by patch tracking in IMOD42. In total, ~200 tomograms were reconstructed, and 94 tomograms with good alignment were selected for subsequent analysis. Tomograms were 3D reconstructed at bin 8 in IMOD42 by the Weighted Back-Projection method and processed with a deconvolution script: tomo_deconv (https://github.com/dtegunov/tom_deconv) before segmentation and particles annotation.

STA of PBS complexes

The reconstructed tomogram showed an Arthrospira FACHB439 sample with a regular distribution of PBS particles (Fig. 1d, e). Initially, ~3000 PBS sub-tomograms were manually picked from 6 tomograms (at bin 8) in Dynamo43. After translational and rotational alignment in Dynamo at bin 4, the averaging density map showed a shape of PBS array at ~30 Å resolution. By using this density map as a template, ~60,000 particles were picked out by template matching from selected tomograms in emClarity44. After manually removing falsely picked particles, 53,000 particles were subjected to STA. The cycles of alignment and averaging were consecutively processed at bin 4, bin 3, and bin 2 with a shape mask containing three PBSs (not including the membrane region and the peripheral hexamer of each rod), yielding an averaging map of ~10 Å (Fig. 1f). The density map had a blurred density at the bottom region of PBS, which were assumed to be PSII signal in the thylakoid membrane.

Tomogram segmentation and 3D visualization

The thylakoid membrane in tomograms was segmented by using TomoSegMemTV45 and manually tracing the membrane density in the regions with weak signals. PBSs were repositioned back to tomograms according to the translational coordinates and Euler angles from the refinement result of STA. PSII particles were simply posited according to the spatial relation to PBS particles. PBS array, PSII, and the thylakoid membrane were represented as different colors in ChimeraX46 (Fig. 1g–i).

Data collection for high-dose single-particle images

In the previously reported hybrid method47,48, the high-dose image was first acquired at 0° followed by the typical tilt-series data collection on the same position of the lamella. Because an initial high-dose image is taken, the tolerance of the biological sample to the electron dose, and the range in which to acquire a tilt series without changes in the sample structure, is lower. The need to use a lower dose per tilt would lead to lower SNR and thus increase the difficulty of the cryo-ET-STA data processing. In our approach, high-dose images were acquired at positions different from the tilt series on the lamella. Images were acquired as 80 movie frames with a total dose of 35 e−/Å2 by using SerialEM39 at the same magnification as the tilt-series with a defocus range from −1.5 μm to −4.0 μm. Beam-induced motions between frames were corrected in cryoSPARC49 and the output micrographs were dose-weighted and binned with a factor of 2. The contrast transfer function (CTF) parameters of micrographs were estimated by CTFFIND450. Micrographs were inspected visually to exclude very large motions or incorrect CTF estimation. 1652 micrographs were selected from ~2200 micrographs for further analysis.

Particle picking from single-particle images

To translationally and rotationally localize the PBS–PSII complexes in high-dose images of lamella sample, we performed a high-resolution template matching method using a recently developed software GisSPA18, which was optimized to identify target protein signals from overlapping densities of crowded environment. The resulting density map from STA was applied with a bandpass filter from 10 Å to 50 Å and a mask containing three PBSs, and was used as the 3D template. Sampling points of three Euler angles were defined by dividing the Euler angle space equally at an interval of 3.7° in RELION51 Euler angle definition. The cross-correlograms were calculated at bin 2 level and the threshold used for particle detection was set as 6.3. Reduplicated peaks in cross-correlograms within a distance of 15 pixels and an orientation spacing angle of 30° were excluded. An average of ~130 peaks were detected in each micrograph. An example of detected particles was demonstrated in Fig. 1k. Subsequently, the parameters of each particle, including coordinates, defocus and Euler angles were imported into RELION51 for structure refinement. The first attempt at particle picking generated 212,000 detections. By using the averaging map of sub-tomograms as the initial reference, refinement in RELION51 yielded a density map of 6.5 Å (Supplementary Fig. 1b). This density map was used to perform high-resolution template matching once more. A second round of particle picking detected 896,000 particles (Fig. 1m). All the particles were merged together and overlapping particles were removed. After 3D classifications, the good classes (showing PSII density) including 167,000 particles were subjected to further analysis.

Although the membrane region was excluded in high-resolution template matching by applying a mask, the reconstruction from 2D particles picked by GisSPA18 showed a clear membrane protein signal (Supplementary Fig. 1). This signal could also be identified from raw tomograms, which indicated that the structure was not induced by template bias.

Comparative analysis of particle detection efficiency

To evaluate the particle detection efficiency using various references, comparative tests were conducted on a set of 100 SPA images. Each reference was subjected to particle detection using the software GisSPA18 under the same parameters. The 3D references used for input were illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 3a. Reference 1 was our SPA map at 6.5 Å, which was reconstructed from the first round of particle picking and used for the second round. Reference 2 was our STA map at 10 Å, which served as the basis for the first round of particle picking, as described above. Reference 3 was the previously reported EM map of the in situ STA PBS array (EMD-4602 [https://www.ebi.ac.uk/emdb/EMD-4602])13. Reference 4 was a simulated density map generated from an in vitro SPA PBS model (PDB 7EXT)24 using the pdb2mrc function in the EMAN software package52. Reference 5 was a composited map, in which three PBS models from PDB 7EXT were docked into EMD-4602 and then converted into a density map. The detected particle counting for the five references were 51,453, 31,464, 9,152, 20,801, and 24,792, respectively. Because of the unknown exact particle count in SPA images, the particle number from reference 1 was employed as a normalization factor to calculate the detection ratios for the other references. All the particles from five references were merged with an additional 91,000 high-quality particles derived from all SPA images, followed by a 3D classification in RELION. Classes exhibiting a clear PSII signal were deemed valid particles. The valid particles corresponding to the five references were then graphically represented in Supplementary Fig. 3b for comparative analysis.

Structure-refinement on PBS–PSII complexes

We noticed that the in-situ structure of the PBS–PSII supercomplex presented a large extent of flexibility, so we applied a multi-step refinement strategy by gradually reducing the mask size to focus on the smaller local regions during the refinement. The detailed steps of structure-refinement for subregions of PBS–PSII complexes were represented in Supplementary Fig. 2. Particles were shifted to the center of two PBS monomers and extracted at bin1 with a box size of 400 pixels. A local refinement (with an angle step of 3.7° and a mask containing two PBS along with a membrane region) yielded a 5.6 Å reconstruction. Particles were then subjected to three rounds of CTF refinement and 3D auto-refinement to increase the accuracy of the defocus parameter. Then, 3D classification was carried out with a smaller mask focusing on the PSII region to filter out falsely picked particles and low-quality particles. This 3D classification yielded four output classes, while the first two classes showed clear PSII density and the same conformation. Selected 127,000 particles from class 1 and class 2 (rotated 180° around the z-axis compared to class 1) were reconstructed as a 5.1 Å resolution PBS–PSII array density map (refined with a mask containing 2 PBS) and subjected to further process.

In cryo-ET results, PBSs were distributed in arrays bent into different curvatures, and densely packed and overlapping in the z-direction. The high-resolution template matching step using the reference of three PBS densities might miss potential particles. For samples like protein assembly, more particle positions could be inferred from those already detected by extending the coordinates53. In order to pick the particles exhaustively, a refinement with a mask containing two PBS APCs was performed and particles were subsequently shift-expanded to 1 left position (shifting the x, y in reconstruction coordinates by −15, −70 pixels, while keeping the Euler angle unchanged) and 1 right position (shifting by 15, 70 pixels). One step of local refinement was performed to align translations and rotations of these particles, and overlapped particles within 30 Å were removed (270,000 particles remained). Then the particles were further expanded to three left positions (−15, −70 pixels, −30, −140 pixels, −45, −210 pixels) and three right positions (15, 70 pixels, 30, 140 pixels, 45, 210 pixels), increasing the total particles number to 1,873,000. Again, the particles were aligned and the overlapping particles were removed (1,179,000 particles remained). A mask focusing on a smaller subregion containing only one APC was used for the following 3D classification, and 664,000 particles were selected for further processing.

To improve the resolution of the APC cores, the particles were subjected to an additional 3D classification in RELION51 and a local refinement in cryoSPARC49, which yielded a 3.6 Å local structure. Similar 3D classification steps were also applied to the PSII region. Subsequently, two refinement steps were applied to the selected particles; the first used a shape mask that included two PSII dimers, and the second employed separate local masks for each PSII dimer. Local refinements in cryoSPARC49 improved the resolution of each dimer of PSII to 3.5–3.6 Å, respectively. All the resolutions were estimated by gold-standard Fourier Shell Correlation with a criterion of 0.143 (Supplementary Fig. 2). The local resolution of final reconstructions and the angular distribution of used particles were also shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Since there was no specific difference found between the two connected PSII dimers, we suggest a periodic symmetry in the structure of PBS–PSII complexes. To better display the whole complexes, two copies of the regional map of APC (3.6 Å) and three copies of a regional map of PSII dimer (3.5 Å) were fitted into the lower resolution (5.1 Å) PBS–PSII array density map and merged as one.

Model building and refinement

For the model building of the PBS, the atomic model of Synechococcus 7002 PBS (PDB entry 7EXT)24 was first docked into the maps using Chimera54. The peripheral PC hexamers were not well-fitted into the maps, and thus were manually deleted. Then the PBP and linker proteins were changed to the corresponding sequences of Arthrospira FACHB439 in Coot55 and manually adjusted to better fit with the map. The sequence of LPP2 (GenBank: WP_014273973.1 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/WP_014273973.1]) was identified by searching the homolog of sll1873 (GenBank: BAA18221.1 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/BAA18221.1] (ApcG)) in Synechocystis 68036 based on the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). Sequence assignments of PB-loop of LCM, LRC, and LPP2 were guided by corresponding residues in Coot55. Furthermore, de novo model building was performed on the unidentified subunits defined as the LPP1, and the N/C terminus was manually defined in this study. LPP1 is located on the stromal side of PSII dimers. However, no similar structure was observed in published PSII structures, indicating that it might be lost during purification. To build the model of PSII dimers, the structure of Synechocystis 6803 (PDB entry 7RCV)8 was docked into density maps using Chimera54, and the sequences were mutated to those of Arthrospira FACHB439 with Coot55.

The model buildings of PBS and PSII dimers were completed via iterative rounds of manual building with Coot55 and refinement with phenix.real_space_refine56 with geometry and secondary structure restraints. Then, all parts were merged into the whole PBS–PSII supercomplex, and the structural validation report was produced against a whole artificially stitched map using local maps in MATLAB (Supplementary Fig. 12). The statistics for data collection and structure refinement are summarized in Supplementary Table 2. Figures were prepared with UCSF ChimeraX46 and PyMOL (http://pymol.org). The sequence alignments were performed by ClustalX257 and created by ESPript58.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff at the Tsinghua University Branch of the National Protein Science Facility (Beijing) for their technical support on the cryo-EM and high-performance computation platforms. We thank Dr. Hong-Wei Wang for providing inspiring discussion for the cryo-EM study in this work. We thank Dr. Wei Lu from the Department of Chemistry, Southern University of Science and Technology, for his assistance on 77 K fluorescence spectra. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32241030 and 32271245 to S.-F.S.), the Young Elite Scientist Sponsorship Program by CAST (2023QNRC001 to X.Y.), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M741985 to X.Y.), and the National Basic Research Program (2016YFA0501101 and 2017YFA0504600 to S.-F.S.).

Author contributions

S.-F.S. supervised the project. Y.X. and X.Y. froze samples, and performed cryo-FIB milling and sequence analysis. X.Z. designed the cryo-EM strategy and optimized the data collection scripts. X.Z., X.Y., and Y.X. collected the cryo-EM data. X.Z. performed the cryo-EM analysis. X.Y. and Y.X. performed the model building and the structure refinement. Y.X. performed the biochemical experiments. X.Y., Y.X., X.Z., S.S., and S.-F.S. analyzed the structure; all authors contributed in writing the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Seiji Akimoto, Michael Grange, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The cryo-EM density maps and atomic models have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank and the Protein Data Bank under the following accession codes: 8WQL (PBS–PSII supercomplex structure), EMD-37749 (artificially stitched map), EMD-37738 (local map of PBS at 3.5 Å resolution), EMD-37747 (local map of PSII dimer at 3.6 Å resolution), and EMD-37750 (low-resolution map of PBS–PSII at 5.1 Å resolution). References structures used in this work are 7RCV, 7EXT, and EMD-4602. Source data are provided in this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Xing Zhang, Yanan Xiao, Xin You.

Contributor Information

Xing Zhang, Email: zhxix@126.com.

Sen-Fang Sui, Email: suisf@mail.tsinghua.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-51460-0.

References

- 1.Nelson, N. & Junge, W. Structure and energy transfer in photosystems of oxygenic photosynthesis. Annu Rev. Biochem.84, 659–683 (2015). 10.1146/annurev-biochem-092914-041942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eberhard, S., Finazzi, G. & Wollman, F. A. The dynamics of photosynthesis. Annu Rev. Genet.42, 463–515 (2008). 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glazer, A. N. Light harvesting by phycobilisomes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Chem.14, 47–77 (1985). 10.1146/annurev.bb.14.060185.000403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Croce, R. & van Amerongen, H. Natural strategies for photosynthetic light harvesting. Nat. Chem. Biol.10, 492–501 (2014). 10.1038/nchembio.1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jordan, P. et al. Three-dimensional structure of cyanobacterial photosystem I at 2.5 Å resolution. Nature411, 909–917 (2001). 10.1038/35082000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dominguez-Martin, M. A. et al. Structures of a phycobilisome in light-harvesting and photoprotected states. Nature609, 835–845 (2022). 10.1038/s41586-022-05156-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma, J. et al. Structural basis of energy transfer in Porphyridium purpureum phycobilisome. Nature579, 146–151 (2020). 10.1038/s41586-020-2020-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gisriel, C. J. et al. High-resolution cryo-electron microscopy structure of photosystem II from the mesophilic cyanobacterium, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA119, e2116765118 (2022). 10.1073/pnas.2116765118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu, H. et al. Phycobilisomes supply excitations to both photosystems in a megacomplex in cyanobacteria. Science342, 1104–1107 (2013). 10.1126/science.1242321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang, L. et al. Structural organization of an intact phycobilisome and its association with photosystem II. Cell Res.25, 726–737 (2015). 10.1038/cr.2015.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanabe, M. et al. Attachment of phycobilisomes in an antenna-photosystem I supercomplex of cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA111, 2512–2517 (2014). 10.1073/pnas.1320599111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang, J., Cheong, K. Y., Falkowski, P. G. & Dai, W. Integrating on-grid immunogold labeling and cryo-electron tomography to reveal photosystem II structure and spatial distribution in thylakoid membranes. J. Struct. Biol.213, 107746 (2021). 10.1016/j.jsb.2021.107746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rast, A. et al. Biogenic regions of cyanobacterial thylakoids form contact sites with the plasma membrane. Nat. Plants5, 436–446 (2019). 10.1038/s41477-019-0399-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann, P. C. et al. Structures of the eukaryotic ribosome and its translational states in situ. Nat. Commun.13, 7435 (2022). 10.1038/s41467-022-34997-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tai, L., Yin, G., Huang, X., Sun, F. & Zhu, Y. In-cell structural insight into the stability of sperm microtubule doublet. Cell Discov.9, 116 (2023). 10.1038/s41421-023-00606-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang, Z. et al. Structures from intact myofibrils reveal mechanism of thin filament regulation through nebulin. Science375, n1934 (2022). 10.1126/science.abn1934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng, J., Li, B., Si, L. & Zhang, X. Determining structures in a native environment using single-particle cryoelectron microscopy images. Innovation2, 100166 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng, J. et al. Determining protein structures in cellular lamella at pseudo-atomic resolution by GisSPA. Nat. Commun.14, 1282 (2023). 10.1038/s41467-023-36175-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lucas, B. A., Zhang, K., Loerch, S. & Grigorieff, N. In situ single particle classification reveals distinct 60S maturation intermediates in cells. Elife11, e79272 (2022). 10.7554/eLife.79272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucas, B. A. et al. Locating macromolecular assemblies in cells by 2D template matching with cisTEM. Elife10, e68946 (2021). 10.7554/eLife.68946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucas, B. A., Himes, B. A. & Grigorieff, N. Baited reconstruction with 2D template matching for high-resolution structure determination in vitro and in vivo without template bias. Elife12, RP90486 (2023). 10.7554/eLife.90486.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.You, X. et al. In situ structure of the red algal phycobilisome–PSII–PSI–LHC megacomplex. Nature616, 199–206 (2023). 10.1038/s41586-023-05831-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luimstra, V. M. et al. Blue light reduces photosynthetic efficiency of cyanobacteria through an imbalance between photosystems I and II. Photosynth Res.138, 177–189 (2018). 10.1007/s11120-018-0561-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng, L. et al. Structural insight into the mechanism of energy transfer in cyanobacterial phycobilisomes. Nat. Commun.12, 5497 (2021). 10.1038/s41467-021-25813-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, M., Ma, J., Li, X. & Sui, S. F. In situ cryo-ET structure of phycobilisome–photosystem II supercomplex from red alga. Elife10, e69635 (2021). 10.7554/eLife.69635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, D. et al. Light-induced excitation energy redistribution in Spirulina platensis cells: “spillover” or “mobile PBSs”? Biochim. Biophys. Acta1608, 114–121 (2004). 10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao, L. S. et al. Structural variability, coordination and adaptation of a native photosynthetic machinery. Nat. Plants6, 869–882 (2020). 10.1038/s41477-020-0694-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao, L. S. et al. Native architecture and acclimation of photosynthetic membranes in a fast-growing cyanobacterium. Plant Physiol.190, 1883–1895 (2022). 10.1093/plphys/kiac372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamanaka, G., Glazer, A. N. & Williams, R. C. Cyanobacterial phycobilisomes. Characterization of the phycobilisomes of Synechococcus sp. 6301. J. Biol. Chem.253, 8303–8310 (1978). 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)34397-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bryant, D. A. et al. The structure of cyanobacterial phycobilisomes: a model. Arch. Microbiol.123, 113–127 (1979). 10.1007/BF00446810 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arteni, A. A., Ajlani, G. & Boekema, E. J. Structural organisation of phycobilisomes from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 and their interaction with the membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1787, 272–279 (2009). 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zlenko, D. V., Krasilnikov, P. M. & Stadnichuk, I. N. Structural modeling of the phycobilisome core and its association with the photosystems. Photosynth. Res.130, 347356 (2016). 10.1007/s11120-016-0264-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mullineaux, C. W. et al. Mobility of photosynthetic complexes in thylakoid membranes. Nature390, 421–424 (1997). 10.1038/37157 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mullineaux, C. W. Factors controlling the mobility of photosynthetic proteins. Photochem. Photobiol.84, 1310–1316 (2008). 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00420.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li, H., Li, D., Yang, S., Xie, J. & Zhao, J. The state transition mechanism—simply depending on light-on and -off in Spirulina platensis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta1757, 1512–1519 (2006). 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qin, X., Suga, M., Kuang, T. & Shen, J. R. Photosynthesis. Structural basis for energy transfer pathways in the plant PSI-LHCI supercomplex. Science348, 989–995 (2015). 10.1126/science.aab0214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolff, G. et al. Mind the gap: micro-expansion joints drastically decrease the bending of FIB-milled cryo-lamellae. J. Struct. Biol.208, 107389 (2019). 10.1016/j.jsb.2019.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schaffer, M. et al. Optimized cryo-focused ion beam sample preparation aimed at in situ structural studies of membrane proteins. J. Struct. Biol.197, 73–82 (2017). 10.1016/j.jsb.2016.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mastronarde, D. N. SerialEM: a program for automated tilt series acquisition on tecnai microscopes using prediction of specimen position. Microsc. Microanal.9, 1182–1183 (2003). 10.1017/S1431927603445911 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hagen, W., Wan, W. & Briggs, J. Implementation of a cryo-electron tomography tilt-scheme optimized for high resolution subtomogram averaging. J. Struct. Biol.197, 191–198 (2017). 10.1016/j.jsb.2016.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng, S. Q. et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods14, 331–332 (2017). 10.1038/nmeth.4193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kremer, J. R., Mastronarde, D. N. & McIntosh, J. R. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J. Struct. Biol.116, 71–76 (1996). 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Castano-Diez, D., Kudryashev, M., Arheit, M. & Stahlberg, H. Dynamo: a flexible, user-friendly development tool for subtomogram averaging of cryo-EM data in high-performance computing environments. J. Struct. Biol.178, 139–151 (2012). 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Himes, B. A. & Zhang, P. emClarity: software for high-resolution cryo-electron tomography and subtomogram averaging. Nat. Methods15, 955–961 (2018). 10.1038/s41592-018-0167-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martinez-Sanchez, A., Garcia, I., Asano, S., Lucic, V. & Fernandez, J. J. Robust membrane detection based on tensor voting for electron tomography. J. Struct. Biol.186, 49–61 (2014). 10.1016/j.jsb.2014.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF ChimeraX: structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci.30, 70–82 (2021). 10.1002/pro.3943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang, X. et al. A hybrid approach for scalable sub-tree anonymization over big data using MapReduce on cloud. J. Comput. Syst. Sci.80, 1008–1020 (2014). 10.1016/j.jcss.2014.02.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song, K. et al. In situ structure determination at nanometer resolution using TYGRESS. Nat. Methods17, 201–208 (2020). 10.1038/s41592-019-0651-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Punjani, A., Rubinstein, J. L., Fleet, D. J. & Brubaker, M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods14, 290–296 (2017). 10.1038/nmeth.4169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rohou, A. & Grigorieff, N. CTFFIND4: fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J. Struct. Biol.192, 216–221 (2015). 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scheres, S. H. RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J. Struct. Biol.180, 519–530 (2012). 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ludtke, S. J. et al. EMAN: semiautomated software for high-resolution single-particle reconstructions. J. Struct. Biol.128, 82–97 (1999). 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chai, P., Rao, Q. & Zhang, K. Multi-curve fitting and tubulin-lattice signal removal for structure determination of large microtubule-based motors. J. Struct. Biol.214, 107897 (2022). 10.1016/j.jsb.2022.107897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput Chem.25, 1605–1612 (2004). 10.1002/jcc.20084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr.66, 486–501 (2010). 10.1107/S0907444910007493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr.66, 213–221 (2010). 10.1107/S0907444909052925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Larkin, M. A. et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics23, 2947–2948 (2007). 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Robert, X. & Gouet, P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res.42, W320–W324 (2014). 10.1093/nar/gku316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The cryo-EM density maps and atomic models have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank and the Protein Data Bank under the following accession codes: 8WQL (PBS–PSII supercomplex structure), EMD-37749 (artificially stitched map), EMD-37738 (local map of PBS at 3.5 Å resolution), EMD-37747 (local map of PSII dimer at 3.6 Å resolution), and EMD-37750 (low-resolution map of PBS–PSII at 5.1 Å resolution). References structures used in this work are 7RCV, 7EXT, and EMD-4602. Source data are provided in this paper.