Key Points

Question

Is zasocitinib effective and sufficiently safe for treating psoriasis?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 259 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, 18%, 44%, 68%, and 67% of patients receiving oral zasocitinib, 2 mg; zasocitinib, 5 mg; zasocitinib, 15 mg; and zasocitinib, 30 mg, respectively, achieved a 75% or greater improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index scores from baseline to week 12 vs 6% of patients receiving placebo (significant at ≥5 mg). Treatment-emergent adverse events were reported for 53% to 62% of zasocitinib-treated and 44% of placebo-treated patients, with no dose dependency.

Meaning

The results of this trial suggest that zasocitinib, a selective tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor, represents a potential new oral treatment for psoriasis.

Abstract

Importance

New, effective, and well-tolerated oral therapies are needed for treating psoriasis. Zasocitinib, a highly selective allosteric tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) inhibitor, is a potential new oral treatment for this disease.

Objective

To assess the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of zasocitinib in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This phase 2b, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple-dose randomized clinical trial was conducted from August 11, 2021, to September 12, 2022, at 47 centers in the US and 8 in Canada. The study included a 12-week treatment period and a 4-week follow-up period. Key eligibility criteria for participants included age 18 to 70 years; a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score of 12 or greater; a Physician’s Global Assessment score of 3 or greater; and a body surface area covered by plaque psoriasis of 10% or greater. Of 287 patients randomized, 259 (90.2%) received at least 1 dose of study treatment.

Intervention

Patients were randomly assigned (1:1:1:1:1) to receive zasocitinib at 2, 5, 15, or 30 mg or placebo orally, once daily, for 12 weeks.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary efficacy end point was the proportion of patients achieving 75% or greater improvement in PASI score (PASI 75) at week 12. Secondary efficacy end points included PASI 90 and 100 responses. Safety was also assessed.

Results

In total, 259 patients were randomized and received treatment (mean [SD] age, 47 [13] years; 82 women [32%]). At week 12, PASI 75 was achieved for 9 (18%), 23 (44%), 36 (68%), and 35 (67%) patients receiving zasocitinib at 2, 5, 15, and 30 mg, respectively, and 3 patients (6%) receiving placebo. PASI 90 responses were consistent with PASI 75. PASI 100 demonstrated a dose response at all doses, with 17 patients (33%) achieving PASI 100 with zasocitinib, 30 mg. Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred for 23 patients (44%) receiving placebo and 28 (53%) to 31 (62%) patients receiving the 4 different doses of zasocitinib, with no dose dependency and no clinically meaningful longitudinal differences in laboratory parameters.

Conclusions and Relevance

This randomized clinical trial found that potent and selective inhibition of TYK2 with zasocitinib at oral doses of 5 mg or more once daily resulted in greater skin clearance than placebo over 12 weeks.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04999839

This randomized clinical trial examines the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of zasocitinib in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic immune-mediated inflammatory skin disease that is associated with several comorbidities and impairs the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients.1,2 Approximately 20% of patients with psoriasis have 10% or more of their body surface affected.3 Plaque psoriasis is the most common form and is characterized by erythematous, indurated plaques with overlying silvery scale.

The interleukin (IL)–23/T helper (Th)–17 axis plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of plaque psoriasis,4 as evidenced by the effectiveness of injectable biologics that block IL-23 or IL-17 in its treatment.5 However, to our knowledge, fewer oral therapies have been investigated for treating psoriasis, and none have shown the same levels of efficacy, safety, and tolerability as current biologics.5 The paucity of oral therapies for psoriasis underscores the need for new, effective, and well-tolerated oral agents.

A promising target for novel oral agents in treating psoriasis and other immune-mediated diseases is tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2), a Janus kinase (JAK)–related mediator involved in intracellular signaling transduction via the JAK–signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway.6 Genome-wide association studies have shown that loss-of-function TYK2 variants may protect against several inflammatory diseases, including psoriasis.7,8,9,10,11,12 Although broadly acting oral JAK inhibitors have shown efficacy in psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, alopecia areata, and vitiligo,13,14,15,16 their broad inhibitory effects on multiple JAK enzymes are associated with rare but serious safety concerns, including cancers, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs), and infections,17,18 which have limited their use and further development in psoriasis.

Deucravacitinib, an oral allosteric TYK2 inhibitor recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treating moderate to severe psoriasis, has set the clinical precedent for selectively targeting TYK2 activity in this disease.19,20,21 In contrast to JAK1-3 inhibitors, long-term follow-up has shown that deucravacitinib is not associated with an increased risk of serious safety concerns, and efficacy has been maintained for patients experiencing an early response.22,23

Zasocitinib (formerly TAK-279) is an oral, allosteric inhibitor of TYK2 that binds to the Janus homology 2 (JH2) pseudokinase domain of TYK2, leading to inhibition of kinase activity and subsequent downstream signaling events.24 Although identical in mechanism of action to deucravacitinib, zasocitinib was identified via a computationally enabled design strategy and demonstrates a higher level of selectivity than deucravacitinib for the JH2 domain of TYK2 compared with those of JAK1 and JAK2 owing to steric occlusion from the latter via a methocyclobutyl ring.24 A previous phase 1 study demonstrated that zasocitinib modulates psoriasis primarily through its effects on the IL-23/Th-17 axis, with a safety profile consistent with TYK2 inhibition.25 In the present phase 2b randomized clinical trial, we assessed the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of zasocitinib at various doses in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.

Methods

Ethics

This trial was conducted from August 11, 2021, to September 12, 2022. This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice recommendations, and all applicable regulations. The study protocol (and amendments; Supplement 1 and Supplement 2) and informed consent forms were reviewed and approved by an institutional review board and the central ethics committee of Advarra. All participants agreed to participate in the study by providing their written informed consent form. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines were followed during the development of this article.26

Study Design

This was a phase 2b, randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple-dose trial that enrolled patients with moderate to severe psoriasis from 47 centers in the US and 8 centers in Canada. Patients were randomized 1:1:1:1:1 (stratified by previous treatment with biologics) to receive 1 of 4 oral doses of zasocitinib (2, 5, 15, or 30 mg, once daily) or matching oral placebo for 12 weeks, with an additional 4-week follow-up period for safety monitoring (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3). Protocol amendments are listed in eTable 3 in Supplement 3.

Study Population

Patients aged 18 to 70 years at the time of consent who had plaque psoriasis for 6 months or longer before the screening visit were eligible for inclusion if they had moderate to severe disease as defined by a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI)27 score of 12 or greater and a Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) score of 3 or greater at screening and day 1, plaque psoriasis covering 10% or more of their total body surface area (BSA) at screening and day 1, a body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) of 18 to 42, a total body weight of more than 50 kg, no substantial flare in psoriasis for 3 months or longer before screening, and were a candidate for phototherapy or systemic therapy. Patients were excluded if they had erythrodermic, pustular, guttate, or drug-induced psoriasis; active bacterial, viral, fungal, mycobacterial, or other infections (including tuberculosis); or active herpes infection (including herpes simplex 1 and 2 and herpes zoster) within 8 weeks before the baseline (study day 1), as well as positive results for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or HIV; a previous lack of response to any therapeutic agent targeting IL-12/IL-23, IL-17, and/or IL-23; or any use of topical or systemic treatment that could have affected psoriasis within 2 and 4 weeks before baseline, respectively. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are available in Supplement 1.

Randomization and Masking

Patients were randomized using a randomization list generated using validated software (SAS, version 9.4; SAS Institute) that was stratified based on previous treatment with biologics (yes/no) and kept secured until the masking was broken at the end of study. During screening, investigators acquired a patient identifier number via an interactive web response system, and a randomization number was allocated to each patient. This number contained the site number and patient number and was assigned in numerical order at the screening visit based on a chronological order of screening dates. Participants, investigators, study staff, the company research organization, or the sponsor’s study team were masked to treatment and randomization information.

End Points

The primary efficacy end point was the proportion of patients achieving 75% or greater improvement in PASI score from baseline (PASI 75) at week 12. Secondary efficacy end points included the proportion of patients achieving a PASI 90 or 100 response, or a PGA score of clear (0) or almost clear (1), and change from baseline in the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) at week 12.28 Exploratory efficacy end points are described in the eMethods in Supplement 3. Safety end points included the incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) and changes in vital signs, clinical laboratory parameters, and electrocardiograms.

Statistical Analysis

A sample size of 250 patients (approximately 50 patients per treatment group) was determined to provide 85% power to detect a PASI 75 (≥75% improvement from baseline) response rate of 40% or greater in at least 1 of the zasocitinib treatment groups at a significance level of α = .05 using a 2-sided test, assuming a placebo response rate of 10%. Patient demographic and baseline disease characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage). Race was determined according to what the patient felt best described them. Analyses of patient demographic characteristics, baseline disease characteristics, and the primary and secondary efficacy end points were conducted on the modified intent-to-treat analysis set (all randomized patients who received ≥1 dose of the study treatment). Analysis of the safety end points was conducted in the safety analysis set (all patients who received ≥1 dose of the study treatment). Nonresponse was imputed for missing data for binary end points. Multiplicity adjustment in the primary end point analysis used a hierarchical testing procedure, starting with the highest dose and ending with the lowest dose. No adjustments for multiple comparisons for secondary end points were made; as such, P values for secondary end points are not reported. Point estimates with unadjusted confidence intervals are reported. All analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.4 or higher; SAS Institute).

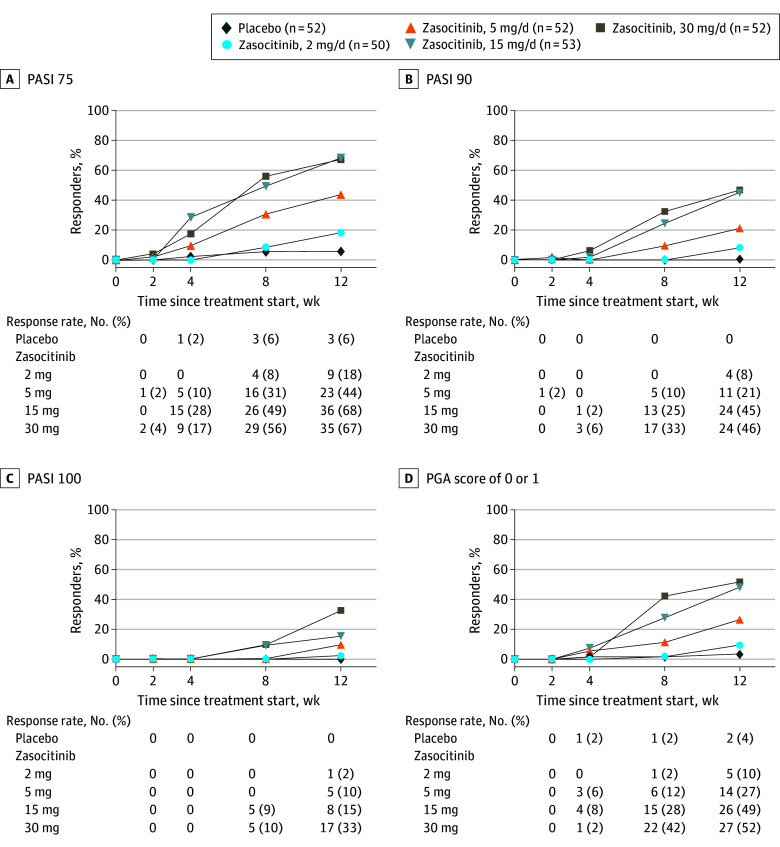

PASI 75, 90, and 100 responses and achievement of a PGA score of 0 or 1 were assessed using descriptive statistics by visit for each group. Longitudinal line plots for PASI 75, 90, and 100 responses and achievement of a PGA score of 0 or 1 by treatment group were also created.

A Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test (using previous biologic treatment as a stratification factor) was used to compare the proportion of patients achieving PASI 75, 90, and 100 scores and PGA 0/1 responses between each active treatment group and placebo. Change from baseline in DLQI was analyzed using a mixed model for repeated measures method. The model included treatment group, visit (weeks 4, 8, and 12), treatment-by-visit interaction, and previous treatment, with biologics as fixed effects and baseline score as a covariate.

Results

Patients

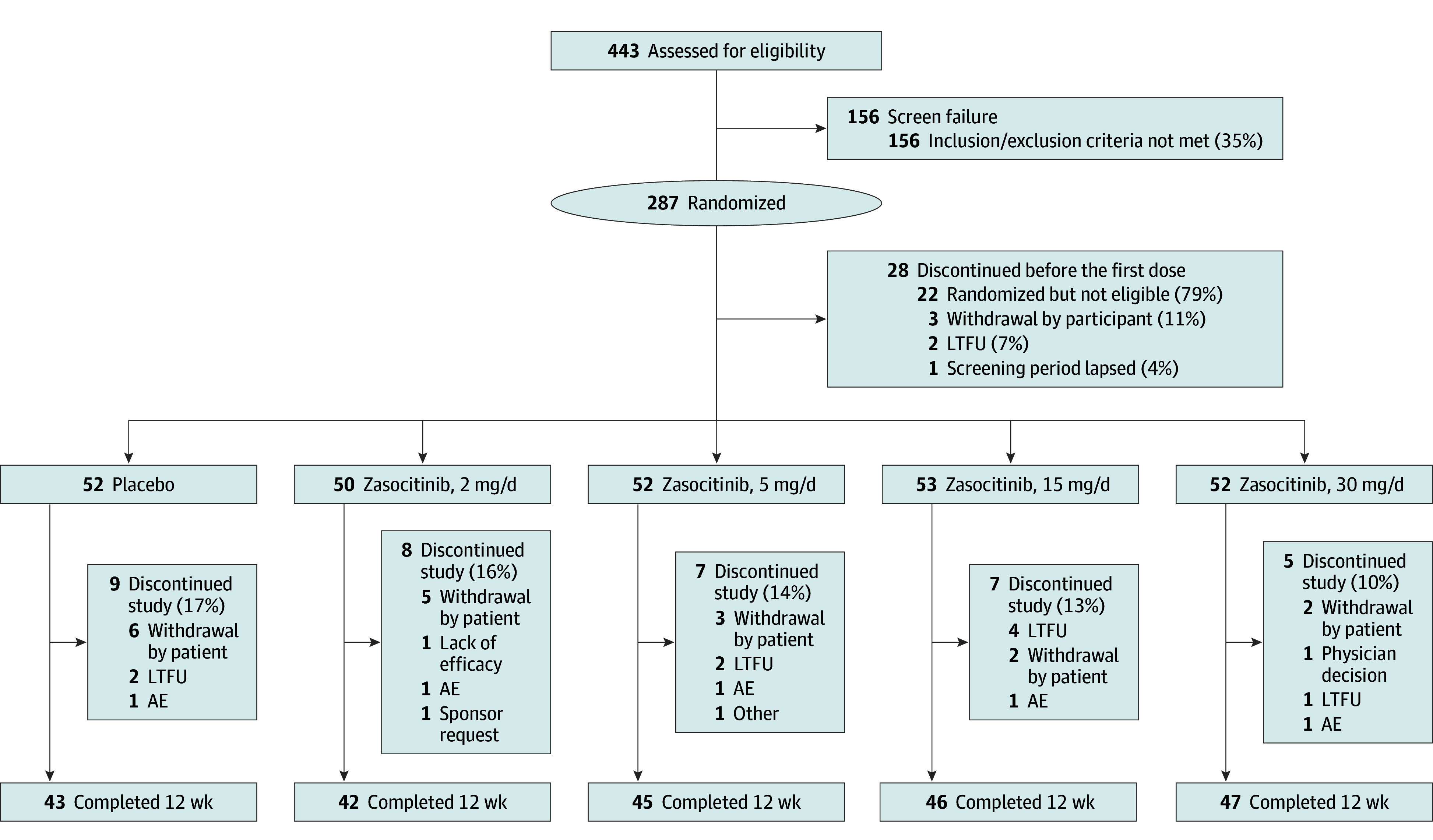

In total, 443 patients were screened for eligibility, of whom 287 (65%) were randomly allocated to 1 of the 4 active treatment groups or placebo, and 259 (58%) received at least 1 dose of study treatment. Overall, 36 patients (14%) discontinued the study prematurely, with 223 (86%) completing the 12-week treatment period (Figure 1). Discontinuations due to TEAEs were infrequent and comparable across treatment groups.

Figure 1. Patient Disposition.

AE, adverse event; LTFU, lost to follow-up.

Patient demographic and baseline disease characteristics were consistent with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis clinical trial populations and were comparable across treatment groups (Table 1). The patient population was predominantly White (215 [83%]) and male (177 [68%]), with a mean (SD) age of 47 (13) years. Approximately 41 patients (16%) had received previous treatment with biologics. The median (range) duration of psoriasis was 12 (6-22) years, mean (SD) PASI score was 18 (6), and mean (SD) BSA was 22% (13%).

Table 1. Demographic and Baseline Disease Characteristics of Patients With Moderate to Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study for Zasocitinib.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 52) | Zasocitinib, once daily | Total (N = 259) | ||||

| 2 mg (n = 50) | 5 mg (n = 52) | 15 mg (n = 53) | 30 mg (n = 52) | |||

| Demographic | ||||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 49 (13) | 46 (14) | 45 (14) | 46 (13) | 49 (11) | 47 (13) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 21 (40) | 12 (24) | 11 (21) | 19 (36) | 19 (37) | 82 (32) |

| Male | 31 (60) | 38 (76) | 41 (79) | 34 (64) | 33 (63) | 177 (68) |

| Race | ||||||

| Asian | 5 (10) | 3 (6) | 7 (14) | 2 (4) | 3 (6) | 20 (8) |

| Black or African American | 2 (4) | 4 (8) | 4 (8) | 3 (6) | 4 (8) | 17 (7) |

| White | 44 (85) | 43 (86) | 40 (77) | 46 (87) | 42 (81) | 215 (83) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 88 (16) | 94 (17) | 90 (19) | 93 (17) | 90 (18) | 91 (17) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 31 (5) | 31 (5) | 30 (6) | 32 (5) | 30 (5) | 31 (5) |

| Clinical | ||||||

| Duration of psoriasis, median (range), y | 9 (6–16) | 12 (6-17) | 12 (7-21) | 12 (6-27) | 16 (8-27) | 12 (6-22) |

| Prior treatment with biologics | 8 (15) | 8 (16) | 8 (15) | 9 (17) | 8 (15) | 41 (16) |

| PASI score, mean (SD)a | 18 (8) | 18 (7) | 19 (6) | 16 (5) | 18 (6) | 18 (6) |

| PGA score, mean (SD)b | 3 (0) | 3 (0) | 3 (0) | 3 (0) | 3 (0) | 3 (0) |

| PGA scoreb | ||||||

| 3: Moderate | 41 (79) | 30 (60) | 34 (65) | 40 (75) | 42 (81) | 187 (72) |

| 4: Severe | 11 (21) | 20 (40) | 18 (35) | 13 (25) | 10 (19) | 72 (28) |

| BSA, mean (SD), %c | 21 (14) | 25 (16) | 23 (12) | 18 (10) | 22 (14) | 22 (13) |

| DLQI score, mean (SD)d | 12 (7) | 10 (6) | 13 (7) | 12 (7) | 13 (7) | 12 (7) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); BSA, body surface area; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PGA, Physician’s Global Assessment.

The PASI is a composite score ranging from 0 to 72 that considers the degree of erythema, induration/infiltration, and desquamation (each scored from 0 to 4 separately) for each of 4 body regions, with adjustments for the percentage of the BSA involved for each body region and proportion of the body region to the whole body. For PASI calculation, the 4 main body regions were assessed: the head, the trunk, and the upper and lower extremities, corresponding to 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40% of the total body area, respectively. The area of psoriatic involvement of these 4 main regions was given a numerical value: 0 indicating no involvement, 1 indicating less than 10% psoriatic involvement, 2 indicating 10% to less than 30% psoriatic involvement, 3 indicating 30% to less than 50% psoriatic involvement, 4 indicating 50% to less than 70% psoriatic involvement, 5 indicating 70% to less than 90% psoriatic involvement, and 6 indicating 90% to 100% psoriatic involvement.27

The PGA score is a 5-point morphological assessment of overall disease severity. For the purposes of this study, the PGA score ranged from 0 to 4, with 0 representing clear skin and 4 representing severe disease.

The overall BSA affected by plaque psoriasis was evaluated from 0% to 100%. The palmar surface of 1 hand (using the patient’s hand and including the fingers) represented 1% of the total BSA.

The DLQI is a 10-question validated questionnaire structured with each question having 4 alternative responses: not at all, a little, a lot, or very much, with corresponding scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The questionnaire also includes a “not relevant” answer scored as 0. The DLQI is calculated by summing the score of each question, resulting in a maximum of 30 and minimum of 0. The higher the score, the greater the impairment of quality of life.28

Efficacy

At week 12, the primary efficacy end point (PASI 75) was achieved in patients receiving zasocitinib at doses of 5 mg and higher: 9 (18%), 23 (44%), 36 (68%), and 35 (67%) patients in the zasocitinib 2-, 5-, 15-, and 30-mg groups, respectively, and in 3 patients (6%) in the placebo group. PASI 75 responses increased from 2 mg to 15 mg but were similar at 15 mg and 30 mg (Table 2).

Table 2. Efficacy at Week 12 in Patients With Moderate to Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study for Zasocitinib.

| End pointa | Placebo (n = 52) | Zasocitinib, once daily | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 mg (n = 50) | 5 mg (n = 52) | 15 mg (n = 53) | 30 mg (n = 52) | ||

| PASI 75 (primary end point), No. (%) | 3 (6) | 9 (18) | 23 (44) | 36 (68) | 35 (67) |

| P value vs placebo | NA | .05 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Proportion difference vs placebo, % (95% CI)b | NA | 12 (0 to 25) | 39 (24 to 53) | 62 (48 to 76) | 62 (47 to 76) |

| PASI 90, No. (%) | 0 | 4 (8) | 11 (21) | 24 (45) | 24 (46) |

| Proportion difference vs placebo, % (95% CI)b | NA | 8 (1 to 16) | 21 (10 to 32) | 45 (32 to 59) | 46 (33 to 60) |

| PASI 100, No. (%) | 0 | 1 (2) | 5 (10) | 8 (15) | 17 (33) |

| Proportion difference vs placebo, % (95% CI)b | NA | 2 (−2 to 6) | 10 (2 to 18) | 15 (5 to 25) | 33 (20 to 45) |

| PGA score of 0 or 1, No. (%) | 2 (4) | 5 (10) | 14 (27) | 26 (49) | 27 (52) |

| Proportion difference vs placebo, % (95% CI)b | NA | 6 (−4 to 16) | 23 (10 to 36) | 45 (31 to 60) | 48 (34 to 63) |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PASI 75, at least 75% improvement in PASI; PASI 90, at least 90% improvement in PASI; PASI 100, 100% improvement in PASI; PGA, Physician’s Global Assessment.

The PASI is a composite score ranging from 0 to 72 that considers the degree of erythema, induration/infiltration, and desquamation (each scored from 0 to 4 separately) for each of 4 body regions, with adjustments for the percentage of the BSA involved for each body region and proportion of the body region to the whole body. For PASI calculation, the 4 main body regions were assessed: the head, the trunk, and the upper and lower extremities, corresponding to 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40% of the total body area, respectively. The area of psoriatic involvement of these 4 main regions was given a numerical value: 0 indicating no involvement, 1 indicating less than 10% psoriatic involvement, 2 indicating 10% to less than 30% psoriatic involvement, 3 indicating 30% to less than 50% psoriatic involvement, 4 indicating 50% to less than 70% psoriatic involvement, 5 indicating 70% to less than 90% psoriatic involvement, and 6 indicating 90% to 100% psoriatic involvement.27 The PGA score is a 5-point morphological assessment of overall disease severity. For the purposes of this study, the PGA score ranged from 0 to 4, with 0 representing clear skin and 4 representing severe disease.

Proportion differences for achievement of PASI 75, PASI 90, PASI 100, and a PGA of 0 or 1 were calculated using the Mantel-Haenszel method. The P value for the primary end point was derived from a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, with previous treatment with biologics included as a stratification factor, and compared with the proportion of patients achieving PASI 75 in each dose group of zasocitinib vs placebo. P values for secondary end points were not reported because these values have not been adjusted for multiple comparisons; 95% CIs are unadjusted.

PASI 90 was achieved for 4 (8%), 11 (21%), 24 (45%), and 24 patients (46%) receiving zasocitinib at 2, 5, 15, and 30 mg, respectively, and for no patients in the placebo group. The pattern of the dose-response association for PASI 90 was similar to PASI 75 (Table 2). PASI 100 was achieved for 1 (2%), 5 (10%), 8 (15%), and 17 (33%) patients receiving zasocitinib at 2, 5, 15, and 30 mg, respectively, and for no patients in the placebo group. An increase in PASI 100 was observed across all doses tested, with the highest response in the 30-mg group (Table 2). The effects of zasocitinib treatment on PASI responses were also apparent as early as week 4 and persisted through to the end of the 12-week treatment period (Figure 2, A-C; eTable 1 in Supplement 3).

Figure 2. Time Course of Efficacy Responses.

A, Proportion of patients with at least a 75% improvement from baseline in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score (PASI 75; primary end point). B, Proportion of patients with at least a 90% improvement in the PASI score (PASI 90). C, Proportion of patients with a 100% improvement in the PASI score (PASI 100). D, Percentages of patients with a Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) score of 0 or 1 (on a scale from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater disease severity). Patients with missing values at each point and patients with assessments collected on the day of, or after the start of, a prohibited medication that was considered a major protocol deviation were imputed as nonresponders.

A PGA score of 0 or 1 was achieved at week 12 for 5 (10%), 14 (27%), 26 (49%), and 27 (52%) patients receiving zasocitinib at 2, 5, 15, and 30 mg, respectively, and for 2 patients (4%) in the placebo group (Table 2). As with PASI 75 and PASI 90, the proportion of patients achieving a PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 12 increased between the 2-mg and 15-mg doses of zasocitinib, with similar efficacy observed with the 15-mg and 30-mg doses (Figure 2D). In a post hoc analysis, a PGA score of 0 (clear skin) was achieved for 1 of 50 (2%), 5 of 52 (10%), 8 of 53 (15%), and 17 of 52 (33%) patients receiving zasocitinib at 2, 5, 15, and 30 mg, respectively, and for no patients in the placebo group.

No difference in DLQI score was observed at any visit for patients receiving zasocitinib, 2 mg, compared with placebo and only at week 8 and beyond for zasocitinib, 5 mg. Greater changes from baseline were observed in patients receiving zasocitinib at 15 mg, and 30 mg compared with placebo, which were observed at week 4 and maintained through week 12 (eFigure 2 in Supplement 3). Changes from baseline in affected BSA generally mirrored the findings for the primary and secondary end points (eFigure 3 in Supplement 3). The findings for other exploratory efficacy outcomes are presented in the eResults in Supplement 3.

Harms

TEAEs occurred at a higher rate in the zasocitinib treatment groups (53%-62%) compared with placebo (44%); however, there was no dose-response association for any specific TEAE (Table 3). COVID-19, acne/acneiform dermatitis, and diarrhea were the most frequently reported events (reported by 3 or more patients in any treatment group) (Table 3). TEAEs leading to study treatment discontinuation occurred for 1 to 2 patients (2%-4%) in the zasocitinib treatment groups and 1 patient (2%) in the placebo group. Two SAEs were reported in a single patient receiving zasocitinib, 15 mg (severe pleural effusion and severe pericardial effusion); however, these were considered unrelated to study drug (Table 3). There were no MACE, thromboembolic events, or opportunistic infections.

Table 3. Summary of Harms in Patients With Moderate to Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study for Zasocitinib.

| Adverse Event | No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 52) | Zasocitinib, once daily | ||||

| 2 mg (n = 50) | 5 mg (n = 52) | 15 mg (n = 53) | 30 mg (n = 52) | ||

| Deaths | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SAEs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 |

| TEAEs | 23 (44) | 31 (62) | 28 (54) | 28 (53) | 31 (60) |

| TEAEs leading to study treatment discontinuationa | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) |

| Most frequent TEAEsb | |||||

| COVID-19c | 1 (2) | 6 (12) | 4 (8) | 6 (11) | 7 (14) |

| Acnec | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | 3 (6) | 2 (4) |

| Acneiform dermatitisc | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 3 (6) |

| Diarrheac | 1 (2) | 3 (6) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 |

Abbreviations: SAE, serious adverse event; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

TEAEs leading to drug discontinuation and early termination in 5 patients included increased creatine kinase levels (30 mg), pericardial effusion and pleural effusion (15 mg), tachycardia and syncope (5 mg), decreased lymphocyte cell counts (2 mg), and atrial fibrillation (placebo).

TEAEs reported by 3 or more patients in any treatment group (events elicited by laboratory testing are not included).

All events of COVID-19 and acneiform dermatitis were grade 1 (mild) or grade 2 (moderate) in severity and resolved by the end of the study. All events of acne and diarrhea were grade 1 (mild) in severity, and most were resolved by the end of the study.

No clinically meaningful longitudinal differences were observed in laboratory parameters for cholesterol levels, blood cell counts, liver enzyme levels, or estimated glomerular filtration rates with zasocitinib compared with placebo. Creatine kinase elevations were more common in the zasocitinib treatment groups compared with placebo, but there was no evidence of dose dependence (eFigures 13-15 in Supplement 3). Clinically significant TEAEs associated with creatine kinase elevation were observed at similar rates between the zasocitinib treatment groups and placebo, and there were no cases of rhabdomyolysis. A full list of all TEAEs is contained in eTable 4 in Supplement 3.

Discussion

In this randomized clinical trial, the primary end point of PASI 75 response at week 12 was achieved for patients receiving zasocitinib at doses of 5 mg and higher. The secondary end points of PASI 90 and 100 and a PGA score of 0 or 1 were concordant with the primary end point. A trend for a dose-response association was observed for PASI 75 and 90 up to zasocitinib, 15 mg, with similar efficacy achieved with zasocitinib, 30 mg. By contrast, the trend for a dose-response association for PASI 100 continued past zasocitinib, 15 mg, with the highest response with zasocitinib, 30 mg. This suggests that higher coverage of the target is more likely to result in complete skin clearance without the risk of clinically significant toxic effects characteristic of JAK1-3 inhibition.

The current study also investigated the effect of zasocitinib on the HRQoL of patients using the DLQI. Previous studies using DLQI and the Psoriasis Symptom Inventory have shown that complete skin clearance (PASI 100) is associated with clinically meaningful improvements in the HRQoL and psoriasis symptoms of patients compared with almost complete skin clearance (PASI 90 to <100).29,30,31,32 In the current study, patients receiving zasocitinib, 30 mg, had the greatest reduction in DLQI from baseline compared with all other zasocitinib treatment groups and placebo, indicating a dose-responsive improvement in HRQoL. Greater DLQI reductions from baseline in the zasocitinib, 15 mg, and zasocitinib, 30 mg, treatment groups relative to placebo were observed from as early as week 4.

The incidence of TEAEs was higher in the zasocitinib groups compared with placebo, but there was no clear dose dependence for any individual TEAE. The incidence of TEAEs of 44% in the placebo arm aligned with previous clinical trial results of treatments in plaque psoriasis, for which TEAEs occurred at similar rates between treatment and placebo groups.19,33,34 COVID-19, acne/acneiform dermatitis, and diarrhea were the most frequently reported TEAEs. No treatment-related SAEs or opportunistic infections or psychiatric sequelae (eg, suicide attempts) were reported during the study. In addition, rates of study discontinuation due to TEAEs were low overall and comparable between the placebo and active treatment groups. Some asymptomatic, transient, and/or reversible change in some laboratory parameters were also observed, such as creatine kinase elevation; however, these were not considered meaningful by the investigators, and there were no cases of rhabdomyolysis. Additionally, there were no dose-dependent associations between zasocitinib use and changes in liver function or hematology parameters. Consistent with the phase 3 randomized clinical trials of deucravacitinib,20,21 there were no MACE or thromboembolic events observed in this trial. The efficacy and safety results from the current study were also consistent with previous studies on zasocitinib.25,35

The lack of JAK-related safety signals was consistent with the high level of selectivity that zasocitinib demonstrates for the JH2 domain of TYK2 (KD [dissociation constant] = 0.0038 nM) relative to the JH2 domains of JAK1 and JAK2 (KD = 4975 and 23 000 nM, respectively).24 This level of selectivity is achieved through the presence of a methoxycyclobutyl ring that fits into the binding pocket of the TYK2 JH2 domain (defined by Val603 and Lys642) but is sterically occluded from the JAK1 and JAK2 JH2 domains owing to the presence of Ile597 and Ile559 residues.24 Such a selectivity profile could potentially elicit fewer off-target SAEs than currently available JAK1-3 inhibitors, allowing for exploration of higher doses of zasocitinib. By contrast, deucravacitinib binds with a lower binding affinity for TYK2 than that demonstrated by zasocitinib.24 Whether these differences translate into corresponding levels of clinical efficacy remains to be confirmed in further clinical trials.

Limitations

As with any phase 2 trial, this study had limitations, including a potential lack of power due to the small sample size and short study duration. In addition, less than 8% of the patient population was Black or African American, and the study was conducted at centers in North America only and involved a restricted range of patient weights and body mass indices. Therefore, these findings may not be generalizable to more diverse populations in other geographic regions.

Conclusions

In this randomized clinical trial, zasocitinib, an advanced, potent, and highly selective oral TYK2 inhibitor bioengineered to optimize target coverage and functional selectivity, achieved biologic-level efficacy with complete skin clearance observed after only a 12-week treatment period in up to one-third of patients, with a low incidence of known tolerability issues and absence of serious toxic effects that are characteristic of JAK1-3 inhibition. Two phase 3 studies of longer duration and with larger populations (NCT06088043 and NCT06108544) have been initiated to confirm these early observations.

Trial protocol

Statistical analysis plan

eAppendix. List of Investigators

eMethods.

eResults.

eFigure 1. Design of Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis

eFigure 2. Change from Baseline in DLQI in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 3. Change from Baseline in BSA Affected by Psoriasis in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 4. Time Course of PASI 50 Response Rates In Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 5. Change from Baseline in PASI in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 6. Percent Change from Baseline in PASI in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 7. Change from Baseline in PGA in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 8. Proportion of Patients Achieving a ≥2-Grade Decrease from Baseline in PGA at Weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 9. Change from Baseline in Pruritus NRS in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 10. Proportion of Patients with a Baseline Pruritus NRS Score of ≥4 Achieving a ≥4-Point Decrease from Baseline at Weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 11. Change from Baseline in Pain NRS Among Patients with Concomitant Psoriatic Arthritis, in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study for Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 12. Time Course of Affected BSA ≤1% Response in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study for Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 13. Change from Baseline in Hematologic Parameters and Creatine Kinase in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study for Zasocitinib (Safety Analysis Set)

eFigure 14. Change from Baseline in Hepatic and Renal Parameters in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study for Zasocitinib (Safety Analysis Set)

eFigure 15. Change from Baseline in Lipid Parameters in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study for Zasocitinib (Safety Analysis Set)

eTable 1. Proportion of Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis Receiving Zasocitinib Who Achieved PASI 75, 90, and 100 Responses at Weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 (mITT Analysis Set)

eTable 2. Proportion of Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis Receiving Zasocitinib Who Achieved a DLQI of 0 or 1 at Weeks 4, 8, and 12 (mITT Analysis Set)

eTable 3. Protocol Amendments for Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis

eTable 4. Summary of TEAEs by system organ class and preferred term, all periods (safety analysis set)

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Armstrong A, Bohannan B, Mburu S, et al. Impact of psoriatic disease on quality of life: interim results of a global survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12(4):1055-1064. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00695-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong AW, Schupp C, Wu J, Bebo B. Quality of life and work productivity impairment among psoriasis patients: findings from the National Psoriasis Foundation survey data 2003-2011. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e52935. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papp KA, Gniadecki R, Beecker J, et al. Psoriasis prevalence and severity by expert elicitation. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11(3):1053-1064. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00518-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawkes JE, Chan TC, Krueger JG. Psoriasis pathogenesis and the development of novel targeted immune therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(3):645-653. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sbidian E, Chaimani A, Garcia-Doval I, et al. Systemic pharmacological treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;12(12):CD011535. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011535.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, O’Shea JJ. Janus kinases in immune cell signaling. Immunol Rev. 2009;228(1):273-287. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00754.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dendrou CA, Cortes A, Shipman L, et al. Resolving TYK2 locus genotype-to-phenotype differences in autoimmunity. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(363):363ra149. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag1974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enerbäck C, Sandin C, Lambert S, et al. The psoriasis-protective TYK2 I684S variant impairs IL-12 stimulated pSTAT4 response in skin-homing CD4+ and CD8+ memory T-cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):7043. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25282-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsoi LC, Spain SL, Knight J, et al. ; Collaborative Association Study of Psoriasis; Genetic Analysis of Psoriasis Consortium; Psoriasis Association Genetics Extension; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 . Identification of 15 new psoriasis susceptibility loci highlights the role of innate immunity. Nat Genet. 2012;44(12):1341-1348. doi: 10.1038/ng.2467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diogo D, Bastarache L, Liao KP, et al. TYK2 protein-coding variants protect against rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmunity, with no evidence of major pleiotropic effects on non-autoimmune complex traits. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faezi ST, Soltani S, Akbarian M, et al. Association of TYK2 rs34536443 polymorphism with susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematous in the Iranian population. Rheumatology Research. 2018;3(4):151-159. doi: 10.22631/rr.2018.69997.1057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, et al. ; International IBD Genetics Consortium . Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491(7422):119-124. doi: 10.1038/nature11582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papp KA, Menter MA, Abe M, et al. ; OPT Pivotal 1 and OPT Pivotal 2 investigators . Tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: results from two randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(4):949-961. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee KP, Plante J, Korte JE, Elston DM. Oral Janus kinase inhibitors in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Skin Health Dis. 2022;3(1):e133. doi: 10.1002/ski2.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu M, Gao Y, Yuan Y, et al. Janus kinase inhibitors for alopecia areata: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(6):e2320351. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.20351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qi F, Liu F, Gao L. Janus kinase inhibitors in the treatment of vitiligo: a review. Front Immunol. 2021;12:790125. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.790125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clarke B, Yates M, Adas M, Bechman K, Galloway J. The safety of JAK-1 inhibitors. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60(suppl 2):ii24-ii30. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang V, Kragstrup TW, McMaster C, et al. Managing cardiovascular and cancer risk associated with JAK inhibitors. Drug Saf. 2023;46(11):1049-1071. doi: 10.1007/s40264-023-01333-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papp K, Gordon K, Thaçi D, et al. Phase 2 trial of selective tyrosine kinase 2 inhibition in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(14):1313-1321. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armstrong AW, Gooderham M, Warren RB, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88(1):29-39. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strober B, Thaçi D, Sofen H, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, phase 3 program for evaluation of TYK2 inhibitor psoriasis second trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88(1):40-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.08.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armstrong A, Lebwohl M, Warren R, et al. Deucravacitinib in plaque psoriasis: 3-year safety and efficacy results. Accessed January 8, 2024. https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/deucravacitinib-in-plaque-psoriasis-3-year-safety-and-efficacy-results/

- 23.Strober B, Sofen H, Imafuku S, et al. Deucravacitinib in plaque psoriasis: maintenance of response over 3 years in the phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 and PSO-2 trials. Accessed January 8, 2024. https://eadv.org/wp-content/uploads/scientific-abstracts/EADV-congress-2023/Psoriasis.pdf

- 24.Leit S, Greenwood J, Carriero S, et al. Discovery of a potent and selective tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor: TAK-279. J Med Chem. 2023;66(15):10473-10496. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McElwee JJ, Garcet S, Li X, et al. 33226 Analysis of histologic and molecular improvement in moderate-to-severe psoriasis: results from a phase 1b trial of the novel allosteric TYK2 inhibitor NTX-973. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87(3)(suppl):AB139. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.590 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c869. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fredriksson T, Pettersson U. Severe psoriasis—oral therapy with a new retinoid. Dermatologica. 1978;157(4):238-244. doi: 10.1159/000250839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210-216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Revicki DA, Willian MK, Menter A, Saurat JH, Harnam N, Kaul M. Relationship between clinical response to therapy and health-related quality of life outcomes in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Dermatology. 2008;216(3):260-270. doi: 10.1159/000113150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viswanathan HN, Chau D, Milmont CE, et al. Total skin clearance results in improvements in health-related quality of life and reduced symptom severity among patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(3):235-239. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2014.943687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strober B, Papp KA, Lebwohl M, et al. Clinical meaningfulness of complete skin clearance in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(1):77-82.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lacour JP, Bewley A, Hammond E, et al. Association between patient- and physician-reported outcomes in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis treated with biologics in real life (PSO-BIO-REAL). Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10(5):1099-1109. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00428-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papp K, Cather JC, Rosoph L, et al. Efficacy of apremilast in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380(9843):738-746. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60642-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rich P, Sigurgeirsson B, Thaci D, et al. Secukinumab induction and maintenance therapy in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II regimen-finding study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(2):402-411. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gangolli EA, Carreiro S, McElwee JJ, et al. 317 Characterization of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, tolerability and clinical activity in phase I studies of the novel allosteric tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) inhibitor NDI-034858. J Invest Dermatol. 2022;142(8)(suppl):S54. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2022.05.325 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

Statistical analysis plan

eAppendix. List of Investigators

eMethods.

eResults.

eFigure 1. Design of Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Plaque Psoriasis

eFigure 2. Change from Baseline in DLQI in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 3. Change from Baseline in BSA Affected by Psoriasis in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 4. Time Course of PASI 50 Response Rates In Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 5. Change from Baseline in PASI in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 6. Percent Change from Baseline in PASI in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 7. Change from Baseline in PGA in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 8. Proportion of Patients Achieving a ≥2-Grade Decrease from Baseline in PGA at Weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 9. Change from Baseline in Pruritus NRS in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 10. Proportion of Patients with a Baseline Pruritus NRS Score of ≥4 Achieving a ≥4-Point Decrease from Baseline at Weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 11. Change from Baseline in Pain NRS Among Patients with Concomitant Psoriatic Arthritis, in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study for Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 12. Time Course of Affected BSA ≤1% Response in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study for Zasocitinib (mITT Analysis Set)

eFigure 13. Change from Baseline in Hematologic Parameters and Creatine Kinase in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study for Zasocitinib (Safety Analysis Set)

eFigure 14. Change from Baseline in Hepatic and Renal Parameters in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study for Zasocitinib (Safety Analysis Set)

eFigure 15. Change from Baseline in Lipid Parameters in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis in a Phase 2b Study for Zasocitinib (Safety Analysis Set)

eTable 1. Proportion of Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis Receiving Zasocitinib Who Achieved PASI 75, 90, and 100 Responses at Weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 (mITT Analysis Set)

eTable 2. Proportion of Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis Receiving Zasocitinib Who Achieved a DLQI of 0 or 1 at Weeks 4, 8, and 12 (mITT Analysis Set)

eTable 3. Protocol Amendments for Phase 2b Study of Zasocitinib in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis

eTable 4. Summary of TEAEs by system organ class and preferred term, all periods (safety analysis set)

Data sharing statement