Abstract

Botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs), produced by Clostridium botulinum, have been used for the treatment of various central and peripheral neurological conditions. Recent studies have suggested that BoNTs may also have a beneficial effect on pain conditions. It has been hypothesized that one of the mechanisms underlying BoNTs' analgesic effects is the inhibition of pain-related receptors' transmission to the neuronal cell membrane. BoNT application disrupts the integration of synaptic vesicles with the cellular membrane, which is responsible for transporting various receptors, including pain receptors such as TRP channels, calcium channels, sodium channels, purinergic receptors, neurokinin-1 receptors, and glutamate receptors. BoNT also modulates the opioidergic system and the GABAergic system, both of which are involved in the pain process. Understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying these effects can provide valuable insights for the development of novel therapeutic approaches for pain management. This review aims to summarize the experimental evidence of the analgesic functions of BoNTs and discuss the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which they can act on pain conditions by inhibiting the transmission of pain-related receptors.

Keywords: Botulinum neurotoxin, pain, pain-related receptor, analgesic

Introduction

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as an “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage”. 1 Pain is a common reason for seeking medical care, with osteoarthritis, back pain, and headaches ranking among the top 10 causes.2,3 It can be classified as acute or chronic based on the duration of symptoms, with chronic pain persisting or recurring for more than 3 months. 4 Furthermore, pain can be classified into three primary types based on its underlying causes or pathogenesis: nociceptive or inflammatory pain, neuropathic pain, and mixed pain.5–7 Despite advancements in understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of pain, its management remains unsatisfactory, with less than 50% of patients finding relief from initial medications.8,9 There is a need for more effective analgesics, which requires a deeper understanding of pain mechanisms. Neuropathic pain is a chronic condition that poses challenges in clinical treatment due to its limited response to therapies compared to other types of pain.10,11 It is associated with an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory somatosensory signaling, as well as variations in the processing of pain signals within the central nervous system. The condition is resistant to conventional treatment approaches, and its management can be particularly difficult. 12 The two main symptoms of neuropathic pain, allodynia and hyperalgesia, occur due to the release of inflammatory mediators, which act on nociceptive nerve endings, lowering the threshold for neuronal excitation. This can lead to a phenomenon known as central sensitization.13,14 In cases where the somatosensory nervous system is damaged, the release of inflammatory mediators can trigger ectopic discharge of nerve fibers. This abnormal firing of nerves results in neuronal hyperexcitability, thereby causing symptoms such as hyperalgesia, allodynia, and spontaneous pain.10,15,16 Neuropathy can disrupt the sensory signaling pathway in both the spinal cord and brain by affecting the expression and function of ion channels and receptors within neurons. Numerous ion channels and receptor classes have been identified as potential targets for the development of next-generation analgesic drugs. These channels include potassium channels, sodium channels, ATP-gated channels, transient receptor potential channels, and calcium channels.17–19 The receptor classes include purinergic receptors, the neurokinin-1 receptor, AMPA receptors, NMDA receptors, glutamate receptors, and opioid receptors. These receptors contribute to different levels of pain signaling and are potential targets for therapeutic interventions.20–23

Botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) is a potent neurotoxin used to address pain, particularly neuropathic pain, and has been applied in various medical treatments for disorders like dystonia and blepharospasm.12,24 Numerous clinical trials, case studies, and animal models have demonstrated BoNT’s efficacy in managing neuropathic pain. However, the mechanisms underlying BoNT’s role in pain signaling are subject to debate. Growing evidence suggests that BoNT’s analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects are mediated through multiple mechanisms, indicating a complex interplay in its pain-relieving actions. BoNT therapy alleviated pain through two primary mechanisms. Firstly, it directly reduces muscle contraction by inhibiting acetylcholine release, leading to relief from pain. Secondly, it exerts indirect effects by inhibiting the release of neurotransmitters other than acetylcholine and modulating receptors and ion channels involved in pain signaling. These combined actions

In this review, we aim to provide a comprehensive summary of the potential effects of botulinum neurotoxin on receptors associated with pain. By exploring these mechanisms, we can gain a better understanding of how BoNT exerts its analgesic effects.

Botulinum neurotoxin

BoNTs are a class of bacterial proteins produced by the anaerobic bacteria “Clostridium botulinum”. These toxins exhibit potent inhibitory effects on synaptic transmission within the peripheral cholinergic nervous system. 25 There are seven distinct serologically different BoNT isoforms, designated as A-G [40], and each subtype of BoNT has a different amino acid sequence. 26 Human botulism, a neuroparalytic disease, is primarily caused by four serotypes of BoNT: A, B, E, and F. Types C and D are responsible for inducing botulism in domestic and wild animals but are not known to affect humans. A bacterial species that produces the toxin type G was discovered in South American soil in 1969. However, it has never been associated with causing foodborne botulism.27–29 In recent years, significant progress has been made in understanding the structures and mechanisms of action of BoNTs. These toxins exhibit neurospecificity, targeting peripheral nerve terminals associated with skeletal and autonomic cholinergic nerves, allowing their use as therapeutic agents in treating various human diseases.30,31 FDA-approved BoNT types A and B have been used for conditions such as migraine, hypersalivation, dystonia, overactive bladder, spasticity, strabismus, blepharospasm, and cosmetic procedures.32–38 The duration of BoNT effects varies depending on the serotype, with BoNT/A and BoNT/C typically exhibiting longer-lasting effects (around 4–6 months).39,40

Structure of botulinum neurotoxin

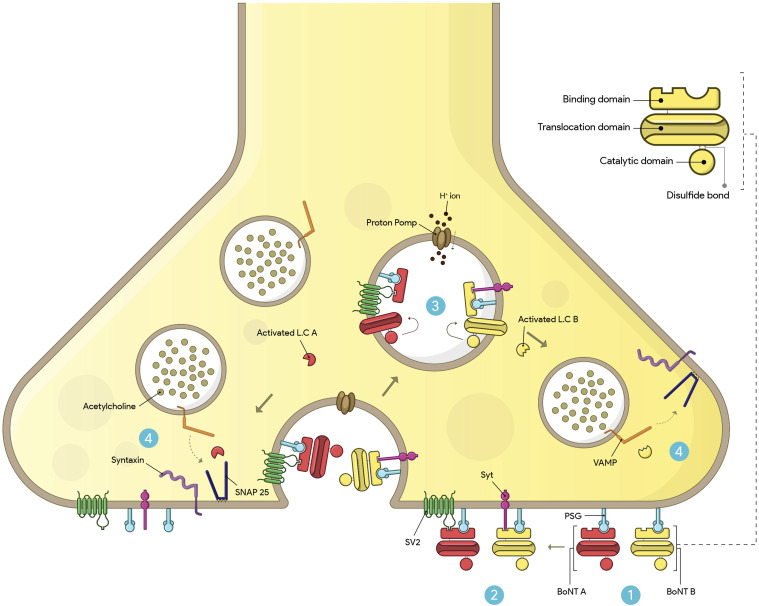

BoNT serotypes consist of a metalloprotease light chain (50 kDa) and a heavy chain (100 kDa) connected by an interchain disulfide bond. The toxin molecule of BoNTs is often enveloped and protected by a group of naturally occurring proteins, in addition to the two peptide chains. These neurotoxins exist as macromolecular complexes ranging in size from 300 kDa to 900 kDa, and the specific molecular weight and structure of the protein complex are determined by the clostridial strain and serotype involved. The 900 kDa complex is unique to serotype A. 28 BoNT serotypes have three functional domains: binding, translocation, and catalytic. The C-terminal of the heavy chain binds the toxin to the receptor site, while the N-terminal of the heavy chain facilitates translocation, while the belt region of the translocation domain contributes to the protection of the active site. The BoNT light chain serves as the catalytic domain and functions as a zinc-dependent endopeptidase. These domains are arranged linearly, with the translocation domain located in the center. Physicochemical tests have shown that each clostridial neurotoxic molecule, except for BoNT/C, contains one zinc atom linked to the light chain. BoNT/C, however, contains two zinc atoms.41,42 The receptor-binding domain of the heavy chain of BoNT initially interacts with polysialogangliosides on the presynaptic surface, and then the toxin binds to another surface receptor, such as synaptotagmin (Syt) or synaptic vesicle protein 2 (Sv2), leading to internalization. BoNT serotypes A, D, E, F predominantly bind with Sv2, while serotypes B and G exhibit a strong affinity for Syt.43–45 BoNT serotype C is unique as it has not yet been associated with a specific protein receptor in neuronal cells. Instead, BoNT-C has been observed to bind to liposomes containing phosphoinositide (Figure 1). 46

Figure 1.

Mechanism of action of BoNT A and B at neuromuscular junction. 1) BoNT uses the C-terminal of its heavy chain (binding domain) to bind to PSGs on the presynaptic surface. 2) BoNT/A binds to SV2, while BoNT/B binds to the Syt protein. Subsequently, the toxin enters the cell through receptor-mediated endocytosis. 3) The entry of H+ ions into the vesicle through proton pumps causes acidification. As a result, the N-terminal of the heavy chain (translocating domain) is inserted into the membrane of the synaptic vesicle, and the LC is subsequently translocated into the cytoplasm. 4) The activated LC selectively cleaves one of the SNARE proteins involved in ACh exocytosis, preventing the complete assembly of the synaptic fusion complex. BoNT/A cleaves SNAP-25, and BoNT/B cleaves the VAMP protein. Eventually, the toxin blocks the release of ACh into the synaptic space.

BoNT binds to specific receptors on the neuronal presynaptic surface and is internalized through receptor-mediated endocytosis. The acidic environment within the endocytic vesicles induces structural changes in BoNT, and the translocation of the BoNT’s catalytic domain, the light chain, into the cytosol takes place when the heavy chain inserts into the membrane of the synaptic vesicle. The light chain remains inactive and does not function while still connected to the rest of the toxin, but after translocation, the light chain is released from the rest of the toxin through the action of cleaving enzymes, such as heat shock protein 90.44,47 After internalization into the neuronal cytosol, the light chain of BoNT targets and cleaves one of three SNARE (soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor) proteins necessary for vesicular trafficking and neurotransmitter release: VAMP, SNAP25, and syntaxin. This enzymatic activity enables BoNTs to exert their toxic effects. 48 BoNT serotypes A and E specifically cleave SNAP-25, while serotype C cleaves both syntaxin and SNAP-25. Serotypes B, D, F, and G of BoNT hydrolyze VAMP. As a result, these proteins become inactive due to BoNT action, leading to the prevention of acetylcholine release and causing reversible chemical paralysis of the muscles.41,44,47

The mechanisms of pain-relieving effect of botulinum neurotoxin

BoNT’s pain-relieving effects are caused by several major mechanisms other than its direct effect on reducing muscle contraction. One significant mechanism through which BoNT alleviates pain, particularly in neuropathic pain conditions, is by inhibiting the release of neurotransmitters involved in the pain pathway, including CGRP,49,50 glutamate,51,52 substance P,53,54 and ATP, 55 through the suppression of SNARE proteins. Moreover, BoNT inhibits the release of pain mediators from peripheral nerve terminals, dorsal root ganglia, and spinal cord neurons, thereby reducing inflammation.56,57 BoNT has been found to suppress glial cell activity, enhances microglial M2 phenotype, and reduces the release of pro-nociceptive and pro-inflammatory mediators. 58 BoNT also modulates the communication between glial cells and neurons, inhibits c-Fos expression, and modulates receptors and ion channels involved in pain signaling.59,60 Additionally, BoNT’s central anti-nociceptive effect is attributed to its ability to cleave SNAP-25 in various central regions, such as the brainstem, 61 motor neurons of the spinal cord,62,63 and superior colliculus. 64 This occurs because BoNT can be retrogradely transported from the peripheral injection site to the central region, allowing it to exert its effects on both peripheral and central neural levels.

The effect of botulinum neurotoxin on pain-related receptors

The application of BoNT disrupts the integration of synaptic vesicles with the cellular membrane, which is responsible for transporting various receptors, including pain receptors. BoNT inhibits the expression of channels and receptors in primary afferent neurons. Peripheral injection of BoNT/A not only affects neurotransmitter secretion in the presynaptic terminal but also influences neurons beyond the synapses, suppressing the translocation of receptors to the cell membrane.65,66 The effects of BoNT on various pain-related receptors are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of studies on BoNT effects on pain-related receptors.

| Receptor type | Model (in vivo, in vitro) | Human/Animal/Cells | BoNT type injection site/Dose | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRPV1 | In vivo | Rat | BoNT/A/Subcutaneously into ophthalmic division of trigeminal ganglion/0.25, 0.5, and 5 ng/kg | Cleavage of SNAP-25, reduction of TRPV1 levels and transmission to cell membrane of trigeminal ganglion neurons | 66 |

| TRPV1 | In vivo | Rat/Spinal ventral root transection model | BoNT/A/Subcutaneously/10 and 20 unit/kg | Reduction of TRPV1 expression in DRG neurons | 67 |

| TRPV1 and TRPA1 | In vivo | Rat | BoNT/A/extracranial injection/outside the calvaria/5 unit | Inhibition of synaptic vesicles attaching comprising TRPA1 and TRPV1 channels into the cell surface | 68 |

| TRPV1 | In vitro | Mouse/Embryonic DRG neurons | BoNT/A/1 nM | Colocalization of TRPV1 with SNAP-25 and BoNT/A in cell membrane | 69 |

| TRPV1 | In vivo | Rat/Adjuvant-arthritis pain model | BoNT/A/Intra-articulary/1, 3 and10 unit | Cleavage of SNAP-25, reduction of TRPV1 expression in DRG neurons | 70 |

| TRPV4 and TRPM3 | In vivo | Rat/ION-CCI model | BoNT/A/Subcutaneously/3 and10 unit | Reduction of TRPV1 expression in the trigeminal spinal subnucleus caudalis | 71 |

| Sodium | In vitro | Rat/Hippocampus and DRG cells | BoNT/A/10 p.m. | Inhibition of membrane Na+-channel activity | 72 |

| Sodium (NaV1.7) | In vivo | Rat/Trigeminal neuropathic pain | BoNT/A/Subcutaneously/10 and 20 unit/kg | Inhibition of Nav1.7 overexpression | 73 |

| Calcium (CaV3.2) | In vivo | Rat/SCI model | BoNT/A/Intramuscularly (into EDL muscles)/1, 3 and 6 unit/kg | Reduction of Cav3.2 expression, reduction of calcium release in EDL muscles | 74 |

| P2X3 | In vivo | Rat/Spinal ventral root transection model | BoNT/A/Subcutaneously/7 unit/kg | Inhibition of P2X3 receptor overexpression | 75 |

| P2X2 and P2X3 | Human (children and adolescents) | Human/Neurogenic detrusor overactivity | BoNT/A/Intramuscularly (into detrusor muscle)/12 unit/kg up to 300 unit | Reduction in expression of P2X2 and P2X3 receptors | 76 |

| P2X7 | In vivo | Rat/CCI model | BoNT/A/Subcutaneously/10 and 20 unit/kg | Reduction of P2X7 expression in spinal cord neurons | 58 |

| In vitro | Rat/LPS-activated microglial cells line | BoNT/A/0.1 nM | Reduction of P2X7 expression | ||

| NK-1 | In vivo | Rat/plantar incision model | BoNT/A/Intraplantary (2 unit) and intrathecally (0.5 unit) | Inhibition of NK-1 receptor overexpression in dorsal horn neurons | 77 |

| NK-1 | In vivo | Mouse/formalin-induced pain model and SNL model | BoNT/B/Intrathecally/0.5 unit | Reduction of NK1-R internalization in spinal dorsal horn neurons, cleavage of VAMP I/II in sensory afferents | 78 |

| AMPA | In vivo | Rat/formalin-induced pain model | BoNT/A/Peripherally (into the right foot)/3 and 6 unit/kg | Reduction of AMPA receptor expression and glutamate secretion in spinal dorsal horn neurons | 51 |

| AMPA (GluA1 subunit) | In vivo | Mouse/Carrageenan-induced pain model | BoNT/B/Intraplantary/1 unit | Reduction of pGluA1 expression in spinal dorsal horn neuron | 79 |

| µ opioid | In vivo | Mouse/SNL model | BoNT/A/Intraplantary/15 pg/paw | Enhancement of µ opioid receptor expression in spinal dorsal horn neurons | 60 |

ION-CCI: chronic constriction injury to the infraorbital nerve, EDL: extensor digitorum longus, CCI: chronic compression injury, SCI: spinal cord injury, SNL: spinal nerve ligation.

Transient receptor potential ion channel

The transient receptor potential (TRP) ion channels, particularly TRPV1 and TRPA1, play a crucial role in various neuropathic pain conditions. 80 These non-selective ion channels are involved in hypersensitivity to chemical, mechanical, and thermal stimuli associated with inflammation and neuropathy. TRPV1 and TRPA1 are expressed together on nociceptive primary afferent fibers and, when activated by endogenous metabolites and natural mediators, they increase sensitivity to pain stimuli, contributing to the experience of pain.81,82 TRPV1 sensitization, a crucial mechanism in pain signaling, involves phosphorylation by various protein kinases (Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase, PKA, PKC, PKG, and tyrosine kinase). Additionally, mediators like bradykinin, PGE2, ATP, and nerve growth factor can sensitize the TRPV1 channel. Another important aspect of pain signaling is the upregulation of TRPV1 expression, which occurs in pathological conditions such as peripheral nerve injuries, leading to increased TRP channel expression at the injury site.83–88

Studies have demonstrated that BoNT/A can decrease TRPV1 expression in peripheral tissues. For example, Apostolidis et al. found that local administration of BoNT/A reduced TRPV1 expression in the human bladder. 89 Moreover, the activation of PKC can induce the translocation of TRPV1 channels to the cell membrane through SNARE-dependent exocytosis in cultured DRG neurons, and BoNT/A inhibits this translocation of TRPV1 to the neuronal surface. 90 BoNT/A appears to hinder the trafficking of TRPV1 to cell membranes by cleaving the SNARE protein complex, leading to a decrease in TRPV1 expression.

BoNT/A can prevent the translocation of TRPV1 to cell membranes through two potential mechanisms. Firstly, it inhibits the phosphorylation of TRPV1, particularly at the Y200 site. 91 It has been observed that blocking SNAP25 activity reduces the delivery of NGF-induced TRPV1 to the cell membrane. 92 BoNT/A inhibits TRPV1 phosphorylation by cleaving SNAP25, which can lead to a decrease in TRPV1 levels. Additionally, BoNT/A affects TRPV1 expression through changes in cell membrane trafficking. In a study by Shimizu et al., subcutaneous injection of BoNT/A in rats’ ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal ganglion area resulted in SNAP25 cleavage and suppressed TRPV1 transmission to the plasma membrane in trigeminal ganglion neurons. RT-PCR analysis showed that BoNT/A did not reduce TRPV1 expression at the transcriptional level. These findings indicate that BoNT/A attenuates TRPV1 expression by inhibiting its cell membrane trafficking. 66 Similarly, Lizu Xiao and colleagues evaluated the effects of BoNT/A on TRPV1 expression in the DRG of a ventral root transaction-evoked neuropathic pain model in rats. They showed that TRPV1 protein levels were significantly upregulated in DRG neurons and that subcutaneous injection of BoNT/A abolished TRPV1 overexpression and attenuated hyperalgesia. 67

BoNT/A’s prophylactic efficacy in chronic migraine depends on reducing the sensitivity of meningeal nociceptors to TRPA1 and TRPV1 channel stimulation. Injecting BoNT/A outside the calvaria in rats successfully suppressed the responses of meningeal C-fiber nociceptors when capsaicin, a TRPV1 agonist, and mustard oil, a TRPA1 agonist, were used to stimulate intracranial dural receptive fields. Extracranial application of BoNT/A reduces the expression of TRPV1 and TRPA1 receptors in dural nerve endings. Administering BoNT/A along suture lines is more effective than muscle administration in inhibiting the activation of meningeal nociceptors through TRPV1 and TRPA1 channels. These findings suggest that injecting BoNT/A near the extracranial nerve endings of meningeal nociceptors can alleviate sensitivity by preventing the attachment of synaptic vesicles containing TRPA1 and TRPV1 channels to the plasma membrane of collateral branches of the same axon. 68

The interaction between the TRPV1 channel and BoNT/A is a critical factor for the analgesic effect of BoNT/A. Functional and structural interactions between the BoNT/A and TRPV1 receptors were observed in the cultured mouse DRG neurons. Following BoNT/A exposure, TRPV1 channels colocalized with cleaved SNAP-25 and BoNT/A in the plasma membrane of neurons. Moreover, TRPV1 bocking using a specific antibody reduced BoNT/A-induced SNAP-25 cleavage. These results showed that BoNT/A interacts structurally with TRPV1 receptors and that this interaction could functionally change the BoNT⁄A activity and TRPV1 levels. 69 In the adjuvant-arthritis pain model of rats, a study found a correlation between the analgesic effect of BoNT/A and TRPV1 levels. Intra-articular injection of BoNT/A dose-dependently reversed nociceptive behaviors, cleaved SNAP-25, and decreased TRPV1 expression in DRG neurons. The analgesic effect of BoNT/A was supported by the co-localization of cleaved SNAP-25 with TRPV1 channels and TRPV1 channels with CGRP in DRG neurons. Additionally, a single intra-articular injection of BoNT/A cleaved SNAP-25 in ipsilateral DRG neurons, indicating retrograde axonal transport. These findings suggest that BoNT/A may act as an anti-nociceptive agent by reducing TRPV1 expression through the inhibition of its cell membrane trafficking. 70 In a rat model of trigeminal neuralgia, Yi Zhang et al. discovered that the analgesic effect of BoNT/A might be linked to the reduction of TRPV4 and TRPM3 levels. In this model, TRPV4 and TRPM3 expression was increased in the trigeminal spinal subnucleus caudalis. The co-overexpression of TRPV4 and TRPM3 can lead to mechanical hyperalgesia. However, subcutaneous injection of BoNT/A reversed hyperalgesia by suppressing the overexpression of TRPV4 and TRPM3 in the central nervous system. 71 These findings suggest that the analgesic effect of BoNT/A involves the inhibition of TRP channel levels, although the exact mechanism remains unclear.

Sodium channel

Voltage-gated sodium channels (NaVs) are important receptors involved in transmitting and amplifying pain signals. 93 The nervous system has nine different isoforms of sodium channels (NaV1.1 to NaV1.9) with distinct properties and distribution.73,94 Sodium channels are implicated in various peripheral neuropathies. 95 Specifically, NaV1.3, NaV1.7, NaV1.8, and NaV1.9 have a critical role in activating nociceptors. 96 Sodium channels regulate the initial depolarization and propagation of action potentials, so changes in their expression and function impact neuronal excitability. 97 Nerve injury can modify sodium channel properties and expression, and alterations in sodium currents significantly contribute to the hyperexcitability observed in neuropathic pain conditions. 98

The deactivation of sodium channels appears to be one of the mechanisms by which BoNT/A can modulate pain behavior. Min-Chul Shin et al. demonstrated that BoNT/A blocked sodium channel activity in central and peripheral neuronal cells, reducing sodium current in cultured hippocampal and DRG cells. 72 Furthermore, subcutaneous injection of BoNT/A significantly reduced mechanical allodynia in rats with trigeminal neuropathic pain. Additionally, BoNT/A effectively inhibited the overexpression of Nav1.7 in the trigeminal ganglion of these nerve-injured animals. These findings suggest that the anti-nociceptive effects of BoNT/A involve suppressing NaV1.7 expression in the trigeminal ganglion. 73

Calcium channel

Voltage-gated calcium channels are important in the pain pathway, activating the action potential and triggering many physiological cytoplasmic processes. 99 Neurons express different classes of calcium channels, which are categorized into low and high-voltage-activated channels based on the activation voltage. 100 The low voltage-activated channels, also known as T-types or CaV3, contribute to neuronal excitability in the descending and ascending pain pathways within the brain, spinal dorsal horn, and primary afferent neurons.99,101–103 T-type calcium channels are enhanced in afferent pain fibers in several chronic pain disorders, such as diabetic neuropathy,104,105 traumatic nerve injury,106–108 and toxic neuropathies induced by chemotherapy.109–112 The CaV3.2 isoform is the most notable among the calcium channels involved in the pain process, and studies confirm it as a target for treating pain conditions. 99 The CaV3.2 channel is highly expressed in DRG neurons, and its contribution to chronic pain pathophysiology has been demonstrated in many reports.113,114 The current and excitability of T-type calcium channels were found to be enhanced in DRG cells of neuropathic pain models.115,116 Studies have revealed that suppression of the T-type calcium channel in spinal dorsal horn neurons might mediated analgesia in rat neuropathic pain models.99,117 These findings suggest the role of the T-type calcium channel in pain processing mediation.

BoNTs may help treat neuropathic pain by inhibiting the T-type calcium channel. Kening Ma et al., showed that BoNT/A reduced the expression of CaV3.2, leading to improved muscle spasticity in a rat SCI model. After SCI, calcium levels were elevated in the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles. Injection of BoNT/A into EDL muscles alleviated symptoms, reduced CaV3.2 expression, and attenuated calcium release in a dose-dependent manner. These data suggest that BoNT/A might prevent SCI-evoked muscle spasticity by acting on the CaV3.2 calcium channel. 74

Purinergic receptor

The ATP signaling pathway is implicated in pain signal processing, with stimulation of ATP purinergic receptors in spinal cord neurons increases pain behavior in animal model. 118 Extracellular ATP activates two superfamilies of surface P2 purinergic receptors: ionotropic receptor channels (P2XRs) and the metabotropic G protein-coupled receptors (P2YRs), which are divided into seven and eight subtypes, respectively. These receptors are present in various cell types and play a vital role in regulating neurotransmission. 119 Several studies have shown a correlation between P2Y expression levels and neuropathic pain conditions, as nerve injuries can lead to dysregulation of P2Y receptor expression, resulting in neuropathic pain. 120 P2X channels, found in nerve terminals of peripheral tissues and the central terminal of DRG and trigeminal ganglia, are implicate in the generation and maintenance of pain. The involvement of P2X channels in pain has been demonstrated in several studies.119,121 Certain P2X receptor subtypes, including P2X2, P2X3, P2X4, and P2X7, play various roles in the pathophysiology of pain.121,122 For example, P2X3 receptors are critical in chronic inflammatory and neuropathic pain. 123 In a mouse model of chronic muscle hyperalgesia, a selective P2X3 receptor antagonist blocked P2X3 receptors and inhibited acute muscle hyperalgesia. 124

Studies have shown that BoNT can alleviate neuropathic pain syndrome by affecting P2X receptors. BoNT/A has been found to reduce hyperalgesia in a rat neuropathic pain model by inhibiting the overexpression of P2X3 receptors in DRG neurons. 75 In another study, BoNT/A reduced the expression levels of muscular P2X2 and P2X3 receptors in adolescents and children with neurogenic detrusor activity. 76 Additionally, BoNT/A has been shown to induce microglial M2 polarization and increase pain threshold by reducing spinal levels of P2X7 receptor in a rat model of neuropathic pain caused by chronic compression injury. Furthermore, in an in vitro inflammatory model, BoNT/A elevated microglial M2 polarization in LPS-activated microglial cells by inhibiting P2X7 receptor levels. 58

Neurokinin-1 receptor

The NK-1 receptors are activated by the tachykinin family of peptides, with the highest affinity to substance P. They are involved in neuropathic pain conditions and are present in peripheral tissues and the central nervous system.125,126 Stimulation of NK-1 receptors maintains hypersensitivity to pain,127,128 and in rodent neuropathic pain models, NK-1 receptor antagonists have been shown to block substance P-evoked activation of spinal cord neurons and inhibit pain transmission. 125

BoNT/A inhibits neuropathic pain by affecting the NK1 receptor internalization in the pain nerve terminal. In a rat plantar incision model, intraplantar and intrathecal administration of BoNT/A alleviated mechanical pain hypersensitivity and inhibited the increase of NK1 receptors in dorsal horn neurons. 77 BoNT has also been found to decrease collagen secretion by suppressing the NK1 receptor signaling pathway in fibroblasts activated during scar formation in cutaneous neurogenic inflammation. 129 In a mouse model of formalin-induced neuropathic pain, intrathecal injection of BoNT/B alleviated nociceptive behavior by reducing NK1-R internalization and the cleavage of VAMP I/II in sensory afferents. Additionally, in mouse models of neuropathic pain, deletion of genes encoding the NK1 receptor inhibited the analgesic function of BoNT/A. 78

Glutamate receptor

Glutamate function is mediated by two types of receptors: ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors. The ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs) family, including AMPA, NMDA, and kainite receptor, is responsible for fast excitatory neurotransmission. In contrast, the metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) family comprises eight subtypes, and is implicated in slow modulating synaptic transmission.130,131 The role of iGluRs in transmitting nociceptive stimuli has been well established. Blocking iGluRs through AMPA receptor, kainite receptor, and NMDA receptor antagonists has been shown to reduce nociceptive transmission in various experimental pain models. 132 Spinal AMPA receptors play a crucial role in neuropathic pain pathogenesis,51,133–137 and AMPA receptor antagonists have been found to reduce pain behavior in animal models of neuropathic pain.51,138 Clinically used AMPA receptor inhibitors have been effective in treating humans with chronic neuropathic pain. 139

BoNT/A along with AMPA receptor antagonists, has been shown to reduce the expression of AMPA receptors in spinal dorsal horn neurons. In a study by Bin Hong and colleagues, peripheral injection of BoNT/A decreased the function and expression of AMPA receptors in dorsal horn neurons through retrograde transportation to the spinal cord. BoNT/A alleviated formalin-induced nociceptive hypersensitivity in rats and reduced glutamate release from dorsal horn neurons by cleavage of SNAP-25. They suggested that peripheral administration of BoNT/A alters the expression of AMPA receptors and glutamate secretion from spinal cord dorsal horn neurons, which might be responsible for its central anti-nociceptive functions. 51 AMPA receptors are composed of four subunits, GluA1-GluA4, each contributing specific properties to the receptor. In a mice model of inflammatory pain, BoNT/B was found to reduce pGluA1 expression, decrease carrageenan-induced allodynia, and prevent NMDA-induced phosphorylation of GluA1. This suggested that peripheral application of BoNT/B transported to the central region and inhibited the phosphorylation of AMPA receptor subunits. 79

NMDA receptor antagonists have been shown to alleviate symptoms of neuropathic pain in both experimental models and patients. 131 In a zebrafish orofacial neuropathic pain model, BoNT/A was shown to decrease nociceptive behavior and interact with the NMDA receptor. The analgesic function of BoNT/A was prevented by the NMDA receptor antagonist ketamine, and molecular data showed an interaction between BoNT/A and NMDA receptors, indicating the involvement of NMDA receptor mechanisms in the anti-nociceptive effects of BoNT/A in neuropathic pain conditions. 140

BoNT/A has been shown to alleviate neuropathic pain by modulating the expression and translocation of various receptors, including TRP ion channels, sodium channels, calcium channels, purinergic receptors, NK-1 receptor, and glutamate receptors. However, it is unclear whether these effects represent the primary mechanism by which BoNT/A exerts its analgesic effects. Further research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms by which BoNT/A reduces pain and to determine the relative contributions of these various mechanisms. Moreover, it is important to note that pain is a complex phenomenon that involves multiple physiological and psychological factors, and targeting a single receptor or pathway may not always be sufficient to effectively manage pain in all patients. A comprehensive approach that includes a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions may be necessary to effectively manage neuropathic pain.

The role of opioidergic system in anti-nociceptive effect of botulinum neurotoxin

The opioid system plays an important role in pain experience and management, with opioid receptors widely distributed in peripheral and central nervous areas. The density of opioid receptors and the function of opioid peptides can change under different neuropathic pain conditions. 141 Studies have demonstrated that the availability of opioid receptors decreases in the brains of patients with chronic pain conditions,142–148 including reduced µ opioid receptor expression in cortical regions implicated in pain conditions.142,149,150 Additionally, downregulation of µ opioid receptor expression has been observed in cortical regions of a rat model of peripheral neuropathic pain. 151

The involvement of the endogenous opioid system in the central anti-nociceptive effect of BoNT/A in an inflammatory pain model has been demonstrated. In both sciatic nerve transaction and formalin-induced pain models, the peripheral anti-nociceptive function of BoNT/A was abolished by systemic (subcutaneously) and central (intrathecally) administration of naltrexone, a non-selective opioid antagonist. Additionally, the analgesic effect of BoNT/A was found to be prevented by intrathecal injection of naloxonazine, a selective µ receptor antagonist, indicating that the analgesic effect of BoNT/A is mediated by the µ opioid receptor. BoNT/A also downregulated c-Fos expression levels in spinal dorsal horn neurons, and this effect was inhibited by naltrexone. These findings suggest that the central analgesic effect of BoNT/A may be associated with endogenous opioid system activity. 152 The interaction between BoNT/A and the opioidergic system was also demonstrated in another study. In a mouse model of neuropathic pain, Intraplantar administration of BoNT/A inhibited morphine-evoked tolerance allodynia and increased the analgesic action of morphine in rats with sciatic nerve lesion-induced neuropathic pain. The expression of the µ opioid receptor was downregulated in dorsal horn neurons of mice with neuropathic pain under chronic morphine treatment, and BoNT/A restored the expression levels of the µ opioid receptor. These results indicate that the beneficial effect of BoNT/A in morphine-evoked tolerance is related to an increase in µ opioid receptor expression in neurons. 60

Association between the anti-nociceptive action of botulinum neurotoxin and GABAergic system

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain and spinal cord dorsal horn. 153 GABAergic synaptic inhibition plays a critical inhibitory role in the transmission of nociceptive information in neuropathic pain.154–156 The inhibitory effect of GABA is mediated through its GABA-A ionotropic receptor and GABA-B metabotropic receptor. Several studies have demonstrated that GABAergic pathway plasticity is implicated in the generation and development of neuropathic pain after nerve injury, with GABA expression and neuronal activity being reduced in animal models of nerve injury. 157 The GABA-A receptor agonist has been found to abolish neuropathic pain behavior, indicating the critical role of GABAergic inhibitory pathways in modulating chronic pain conditions. 158

A study has demonstrated a correlation between the analgesic effect of BoNT/A and the GABA-A receptor. The systemic administration of bicuculline, a GABA-A receptor antagonist, was found to prevent the analgesic effect of peripheral BoNT/A injection in rat models of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Additionally, bicuculline abolished the inhibitory effect of BoNT/A on c-Fos expression levels in spinal dorsal horn neurons. These findings suggest that the GABA-A receptor antagonist abolishes the anti-nociceptive activity of BoNT/A by reducing the GABAergic inhibition pathway in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, which is essential in the initiation and maintenance of chronic pain. BoNT/A can reduce inhibitory GABA activity by cleaving SNAP-25 and suppressing neurotransmitter release. 159

Overall, the studies have shown that BoNT/A may modulate the endogenous opioid system and GABAergic pathways to reduce pain in animal models of neuropathic pain and in vitro experiments. It is also important to note that the opioid system and GABAergic pathways have complex interactions with other neurotransmitter systems and pathways involved in pain modulation.160–164 Therefore, the effects of BoNTs on these systems may be influenced by the activity of other systems and pathways, which may vary depending on the type and severity of the pain and individual patient factors. While the studies suggest a potential role for BoNTs in modulating the opioid system and GABAergic pathways to alleviate neuropathic pain, further research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms by which they work. Additional research is needed to better comprehend the complex interactions between different neurotransmitter systems and pathways involved in pain modulation and to develop more effective and comprehensive approaches to pain management.

Conclusions

BoNT has been employed as a therapeutic option for pain conditions, and its ability to alleviate pain is attributed to various significant mechanisms. One crucial mechanism involves the inhibition of pain-related receptors, which is associated with the inhibition of SNARE proteins. BoNT has the capacity to regulate the expression of TRP ion channels, sodium channels, calcium channels, purinergic receptors, NK-1 receptors, and glutamate receptors, which potentially contribute to its analgesic effects. Additionally, BoNT can modulate the endogenous opioid system and GABAergic pathways, thereby reducing pain sensation.

Nevertheless, although BoNT holds significant potential as a therapeutic strategy for neuropathic pain further investigation is necessary to gain a comprehensive understanding of the exact mechanism underlying the analgesic effects of BoNT. Furthermore, most of the studies performed on animal models, which may not precisely mirror human physiology. Consequently, the findings may not directly apply to humans. Additionally, certain studies are performed in vitro, potentially failing to fully capture the complexity of pain conditions in humans. As a result, the external validity of these studies and the generalizability of their findings may be limited.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Pain Research Center, Neuroscience Institute, Imam Khomeini Hospital Complex, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences [Ethical number: IR.TUMS.NI.REC.1402.043].

ORCID iD

Maziyar Askari Rad https://orcid.org/0009-0002-9609-8526

References

- 1.Loeser JD, Treede R-D. The Kyoto protocol of IASP basic pain terminology. PAIN® 2008; 137: 473–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen SP, Vase L, Hooten WM. Chronic pain: an update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet 2021; 397: 2082–2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rief W, Zenz M, Schweiger U, Rüddel H, Henningsen P, Nilges P. Redefining (somatoform) pain disorder in ICD-10: a compromise of different interest groups in Germany. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2008; 21: 178–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Treede R-D, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, Cohen M, Evers S, Finnerup NB, First MB, Giamberardino MA, Kaasa S, Korwisi B, Kosek E, Lavandʼhomme P, Nicholas M, Perrot S, Scholz J, Schug S, Smith BH, Svensson P, Vlaeyen JWS, Wang SJ. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: the IASP classification of chronic pain for the international classification of diseases (ICD-11). Pain 2019; 160: 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.John Smith E. Advances in understanding nociception and neuropathic pain. J Neurol 2018; 265: 231–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barakat A, Hamdy MM, Elbadr MM. Uses of fluoxetine in nociceptive pain management: a literature overview. Eur J Pharmacol 2018; 829: 12–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen TS, Baron R, Haanpää M, Kalso E, Loeser JD, Rice AS, Treede R-D. A new definition of neuropathic pain. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2011, pp. 2204–2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baron R, Maier C, Attal N, Binder A, Bouhassira D, Cruccu G, Finnerup NB, Haanpää M, Hansson P, Hüllemann P, Jensen TS, Freynhagen R, Kennedy JD, Magerl W, Mainka T, Reimer M, Rice ASC, Segerdahl M, Serra J, Sindrup S, Sommer C, Tölle T, Vollert J, Treede RD. Peripheral neuropathic pain: a mechanism-related organizing principle based on sensory profiles. Pain 2017; 158: 261–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amighi D, Majedi H, Tafakhori A, Orandi A. The efficacy of sphenopalatine ganglion block and radiofrequency denervation in the treatment of cluster headache: a case series. Anesth Pain Med 2020; 10: e104466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colloca L, Ludman T, Bouhassira D, Baron R, Dickenson AH, Yarnitsky D, Freeman R, Truini A, Attal N, Finnerup NB, Eccleston C, Kalso E, Bennett DL, Dworkin RH, Raja SN. Neuropathic pain. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017; 3: 17002–17019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernetti A, Agostini F, de Sire A, Mangone M, Tognolo L, Di Cesare A, Ruiu P, Paolucci T, Invernizzi M, Paoloni M. Neuropathic pain and rehabilitation: a systematic review of international guidelines. Diagnostics 2021; 11: 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colloca L, Ludman T, Bouhassira D, Baron R, Dickenson AH, Yarnitsky D, Freeman R, Truini A, Attal N, Finnerup NB. Neuropathic pain (primer). Nat Rev Dis Prim 2017; 3: 17002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park J, Chung ME. Botulinum toxin for central neuropathic pain. Toxins 2018; 10: 224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muley MM, Krustev E, McDougall JJ. Preclinical assessment of inflammatory pain. CNS Neurosci Ther 2016; 22: 88–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alles SR, Smith PA. Etiology and pharmacology of neuropathic pain. Pharmacol Rev 2018; 70: 315–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egeo G, Fofi L, Barbanti P. Botulinum neurotoxin for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Front Neurol 2020; 11: 716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park J, Luo ZD. Calcium channel functions in pain processing. Channels 2010; 4: 510–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsantoulas C, McMahon SB. Opening paths to novel analgesics: the role of potassium channels in chronic pain. Trends Neurosci 2014; 37: 146–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cregg R, Momin A, Rugiero F, Wood JN, Zhao J. Pain channelopathies. J Physiol 2010; 588: 1897–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Das V. An introduction to pain pathways and pain “targets”. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2015; 131: 1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.North RA, Jarvis MF. P2X receptors as drug targets. Mol Pharmacol 2013; 83: 759–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garry EM, Fleetwood-Walker SM. A new view on how AMPA receptors and their interacting proteins mediate neuropathic pain. Pain 2004; 109: 210–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petrenko AB, Yamakura T, Baba H, Shimoji K. The role of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in pain: a review. Anesth Analg 2003; 97: 1108–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baron R, Binder A, Wasner G. Neuropathic pain: diagnosis, pathophysiological mechanisms, and treatment. Lancet Neurol 2010; 9: 807–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rossetto O, Montecucco C. Presynaptic neurotoxins with enzymatic activities. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2008; 184: 129–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dolly J, Aoki K. The structure and mode of action of different botulinum toxins. Eur J Neurol 2006; 13 Suppl 4: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eleopra R, Tugnoli V, Quatrale R, Rossetto O, Montecucco C. Different types of botulinum toxin in humans. Mov Disord 2004; 19 Suppl 8: S53–S59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aoki K, Guyer B. Botulinum toxin type A and other botulinum toxin serotypes: a comparative review of biochemical and pharmacological actions. Eur J Neurol 2001; 8 Suppl 5: 21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arnon SS, Schechter R, Inglesby TV, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, Fine AD, Hauer J, Layton M, Lillibridge S, Osterholm MT, O'Toole T, Parker G, Perl TM, Russell PK, Swerdlow DL, Tonat K, Working Group on Civilian Biodefense . Botulinum toxin as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA 2001; 285: 1059–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossetto O, Pirazzini M, Montecucco C. Botulinum neurotoxins: genetic, structural and mechanistic insights. Nat Rev Microbiol 2014; 12: 535–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foster KA, Bigalke H, Aoki KR. Botulinum neurotoxin—from laboratory to bedside. Neurotox Res 2006; 9: 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Escher CM, Paracka L, Dressler D, Kollewe K. Botulinum toxin in the management of chronic migraine: clinical evidence and experience. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2017; 10: 127–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thaker H, Zhang S, Diamond DA, Dong M. Beyond botulinum neurotoxin A for chemodenervation of the bladder. Curr Opin Urol 2021; 31: 140–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spiegel LL, Ostrem JL, Bledsoe IO. FDA approvals and consensus guidelines for botulinum toxins in the treatment of dystonia. Toxins 2020; 12: 332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong SO. Cosmetic treatment using botulinum toxin in the oral and maxillofacial area: a narrative review of esthetic techniques. Toxins 2023; 15: 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen S. Clinical uses of botulinum neurotoxins: current indications, limitations and future developments. Toxins 2012; 4: 913–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guntinas-Lichius O. Management of Frey's syndrome and hypersialorrhea with botulinum toxin. Facial Plast Surg Clin 2003; 11: 503–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carr WW, Jain N, Sublett JW. Immunogenicity of botulinum toxin formulations: potential therapeutic implications. Adv Ther 2021; 38: 5046–5064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montecucco C, Molgó J. Botulinal neurotoxins: revival of an old killer. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2005; 5: 274–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zanetti G, Azarnia Tehran D, Pirazzini M, Binz T, Shone CC, Fillo S, Lista F, Rossetto O, Montecucco C. Inhibition of botulinum neurotoxins interchain disulfide bond reduction prevents the peripheral neuroparalysis of botulism. Biochem Pharmacol 2015; 98: 522–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar R, Dhaliwal HP, Kukreja RV, Singh BR. The botulinum toxin as a therapeutic agent: molecular structure and mechanism of action in motor and sensory systems. In: Seminars in neurology. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers, 2016, pp. 010–019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swaminathan S, Eswaramoorthy S. Structural analysis of the catalytic and binding sites of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin B. Nat Struct Biol 2000; 7: 693–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Binz T, Rummel A. Cell entry strategy of clostridial neurotoxins. J Neurochem 2009; 109: 1584–1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choudhury S, Baker MR, Chatterjee S, Kumar H. Botulinum toxin: an update on pharmacology and newer products in development. Toxins 2021; 13: 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mahrhold S, Strotmeier J, Garcia-Rodriguez C, Lou J, Marks JD, Rummel A, Binz T. Identification of the SV2 protein receptor-binding site of botulinum neurotoxin type E. Biochem J 2013; 453: 37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Y, Varnum SM. The receptor binding domain of botulinum neurotoxin serotype C binds phosphoinositides. Biochimie 2012; 94: 920–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montal M. Botulinum neurotoxin: a marvel of protein design. Annu Rev Biochem 2010; 79: 591–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh BR. Botulinum neurotoxin structure, engineering, and novel cellular trafficking and targeting. Neurotox Res 2006; 9: 73–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Urits I, Li N, Bahrun E, Hakobyan H, Anantuni L, An D, Berger AA, Kaye AD, Paladini A, Varrassi G, Vorenkamp KE, Viswanath O. An evidence-based review of CGRP mechanisms in the propagation of chronic visceral pain. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2020; 34: 507–516. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpa.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Y, Lian Y, Zhang H, Xie N, Chen Y. CGRP plasma levels decrease in classical trigeminal neuralgia patients treated with botulinum toxin type A: a pilot study. Pain Med 2020; 21: 1611–1615. DOI: 10.1093/pm/pnaa028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hong B, Yao L, Ni L, Wang L, Hu X. Antinociceptive effect of botulinum toxin A involves alterations in AMPA receptor expression and glutamate release in spinal dorsal horn neurons. Neuroscience 2017; 357: 197–207. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang KY, Mun JH, Park KD, Kim MJ, Ju JS, Kim ST, Bae YC, Ahn DK. Blockade of spinal glutamate recycling produces paradoxical antinociception in rats with orofacial inflammatory pain. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2015; 57: 100–109. DOI: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matak I, Tekus V, Bolcskei K, Lackovic Z, Helyes Z. Involvement of substance P in the antinociceptive effect of botulinum toxin type A: evidence from knockout mice. Neuroscience 2017; 358: 137–145. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marino MJ, Terashima T, Steinauer JJ, Eddinger KA, Yaksh TL, Xu Q. Botulinum toxin B in the sensory afferent: transmitter release, spinal activation, and pain behavior. Pain 2014; 155: 674–684. DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith CP, Gangitano DA, Munoz A, Salas NA, Boone TB, Aoki KR, Francis J, Somogyi GT. Botulinum toxin type A normalizes alterations in urothelial ATP and NO release induced by chronic spinal cord injury. Neurochem Int 2008; 52: 1068–1075. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kursun O, Yemisci M, van den Maagdenberg A, Karatas H. Migraine and neuroinflammation: the inflammasome perspective. J Headache Pain 2021; 22: 55. DOI: 10.1186/s10194-021-01271-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bach-Rojecky L, Dominis M, Lackovic Z. Lack of anti-inflammatory effect of botulinum toxin type A in experimental models of inflammation. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2008; 22: 503–509. DOI: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2008.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gui X, Wang H, Wu L, Tian S, Wang X, Zheng H, Wu W. Botulinum toxin type A promotes microglial M2 polarization and suppresses chronic constriction injury-induced neuropathic pain through the P2X7 receptor. Cell Biosci 2020; 10: 45–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Muñoz-Lora VRM, Dugonjić Okroša A, Matak I, Del Bel Cury AA, Kalinichev M, Lacković Z. Antinociceptive actions of botulinum toxin A1 on immunogenic hypersensitivity in temporomandibularoint of rats. Toxins 2022; 14: 161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vacca V, Marinelli S, Luvisetto S, Pavone F. Botulinum toxin A increases analgesic effects of morphine, counters development of morphine tolerance and modulates glia activation and μ opioid receptor expression in neuropathic mice. Brain Behav Immun 2013; 32: 40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Antonucci F, Rossi C, Gianfranceschi L, Rossetto O, Caleo M. Long-distance retrograde effects of botulinum neurotoxin A. J Neurosci 2008; 28: 3689–3696. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0375-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koizumi H, Goto S, Okita S, Morigaki R, Akaike N, Torii Y, Harakawa T, Ginnaga A, Kaji R. Spinal central effects of peripherally applied botulinum neurotoxin A in comparison between its subtypes A1 and A2. Front Neurol 2014; 5: 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Matak I, Riederer P, Lacković Z. Botulinum toxin’s axonal transport from periphery to the spinal cord. Neurochem Int 2012; 61: 236–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Restani L, Antonucci F, Gianfranceschi L, Rossi C, Rossetto O, Caleo M. Evidence for anterograde transport and transcytosis of botulinum neurotoxin A (BoNT/A). J Neurosci 2011; 31: 15650–15659. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2618-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Burstein R, Zhang X, Levy D, Aoki KR, Brin MF. Selective inhibition of meningeal nociceptors by botulinum neurotoxin type A: therapeutic implications for migraine and other pains. Cephalalgia 2014; 34: 853–869. DOI: 10.1177/0333102414527648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shimizu T, Shibata M, Toriumi H, Iwashita T, Funakubo M, Sato H, Kuroi T, Ebine T, Koizumi K, Suzuki N. Reduction of TRPV1 expression in the trigeminal system by botulinum neurotoxin type-A. Neurobiol Dis 2012; 48: 367–378. DOI: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xiao L, Cheng J, Zhuang Y, Qu W, Muir J, Liang H, Zhang D. Botulinum toxin type A reduces hyperalgesia and TRPV1 expression in rats with neuropathic pain. Pain Med 2013; 14: 276–286. DOI: 10.1111/pme.12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang X, Strassman AM, Novack V, Brin MF, Burstein R. Extracranial injections of botulinum neurotoxin type A inhibit intracranial meningeal nociceptors’ responses to stimulation of TRPV1 and TRPA1 channels: are we getting closer to solving this puzzle? Cephalalgia 2016; 36: 875–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li X, Coffield JA. Structural and functional interactions between transient receptor potential vanilloid subfamily 1 and botulinum neurotoxin serotype A. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0143024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fan C, Chu X, Wang L, Shi H, Li T. Botulinum toxin type A reduces TRPV1 expression in the dorsal root ganglion in rats with adjuvant-arthritis pain. Toxicon 2017; 133: 116–122. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang Y, Su Q, Lian Y, Chen Y. Botulinum toxin type A reduces the expression of transient receptor potential melastatin 3 and transient receptor potential vanilloid type 4 in the trigeminal subnucleus caudalis of a rat model of trigeminal neuralgia. Neuroreport 2019; 30: 735–740. DOI: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000001268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shin M-C, Wakita M, Xie D-J, Yamaga T, Iwata S, Torii Y, Harakawa T, Ginnaga A, Kozaki S, Akaike N. Inhibition of membrane Na+ channels by A type botulinum toxin at femtomolar concentrations in central and peripheral neurons. J Pharmacol Sci 2012; 118: 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang KY, Kim MJ, Ju JS, Park SK, Lee CG, Kim ST, Bae YC, Ahn DK. Antinociceptive effects of botulinum toxin type A on trigeminal neuropathic pain. J Dent Res 2016; 95: 1183–1190. DOI: 10.1177/0022034516659278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ma K, Zhu D, Zhang C, Lv L. Botulinum toxin type A possibly affects Ca(v)3.2 calcium channel subunit in rats with spinal cord injury-induced muscle spasticity. Drug Des Devel Ther 2020; 14: 3029–3041. DOI: 10.2147/DDDT.S256814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xiao L, Cheng J, Dai J, Zhang D. Botulinum toxin decreases hyperalgesia and inhibits P2X3 receptor over-expression in sensory neurons induced by ventral root transection in rats. Pain Med 2011; 12: 1385–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schulte-Baukloh H, Priefert J, Knispel HH, Lawrence GW, Miller K, Neuhaus J. Botulinum toxin A detrusor injections reduce postsynaptic muscular M2, M3, P2X2, and P2X3 receptors in children and adolescents who have neurogenic detrusor overactivity: a single-blind study. Urology 2013; 81: 1052–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li X, Guo R, Sun Y, Li H, Ma D, Zhang C, Guan Y, Li J, Wang Y. Botulinum toxin type A and gabapentin attenuate postoperative pain and NK1 receptor internalization in rats. Neurochem Int 2018; 116: 52–62. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuint.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Huang PP, Khan I, Suhail MS, Malkmus S, Yaksh TL. Spinal botulinum neurotoxin B: effects on afferent transmitter release and nociceptive processing. PLoS One 2011; 6: e19126. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sikandar S, Gustavsson Y, Marino MJ, Dickenson AH, Yaksh TL, Sorkin LS, Ramachandran R. Effects of intraplantar botulinum toxin-B on carrageenan-induced changes in nociception and spinal phosphorylation of GluA1 and Akt. Eur J Neurosci 2016; 44: 1714–1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Go EJ, Ji J, Kim YH, Berta T, Park CK. Transient receptor potential channels and botulinum neurotoxins in chronic pain. Front Mol Neurosci 2021; 14: 772719. DOI: 10.3389/fnmol.2021.772719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jardín I, López JJ, Diez R, Sánchez-Collado J, Cantonero C, Albarrán L, Woodard GE, Redondo PC, Salido GM, Smani T, Rosado JA. TRPs in pain sensation. Front Physiol 2017; 8: 392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dünnwald T, Gatterer H, Faulhaber M, Arvandi M, Schobersberger W. Body composition and body weight changes at different altitude levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Physiol 2019; 10: 430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hermann H, De Petrocellis L, Bisogno T, Schiano Moriello A, Lutz B, Di Marzo V. Dual effect of cannabinoid CB 1 receptor stimulation on a vanilloid VR1 receptor-mediated response. Cell Mol Life Sci 2003; 60: 607–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kwong K, Lee LY. PGE(2) sensitizes cultured pulmonary vagal sensory neurons to chemical and electrical stimuli. J Appl Physiol 2002; 93: 1419-1428. DOI: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00382.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lakshmi S, Joshi PG. Co-activation of P2Y2 receptor and TRPV channel by ATP: implications for ATP induced pain. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2005; 25: 819–832. DOI: 10.1007/s10571-005-4936-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chuang HH, Prescott ED, Kong H, Shields S, Jordt SE, Basbaum AI, Chao MV, Julius D. Bradykinin and nerve growth factor release the capsaicin receptor from PtdIns(4,5)P2-mediated inhibition. Nature 2001; 411: 957–962. DOI: 10.1038/35082088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mizumura K, Sugiur T, Koda H, Katanosaka K, Kumar BR, Giron R, Tominaga M. [Pain and Bradykinin Receptors--sensory transduction mechanism in the nociceptor terminals and expression change of bradykinin receptors in inflamed condition]. Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi 2005; 25: 33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Min J-W, Liu W-H, He X-H, Peng B-W. Different types of toxins targeting TRPV1 in pain. Toxicon 2013; 71: 66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Apostolidis A, Popat R, Yiangou Y, Cockayne D, Ford AP, Davis JB, Dasgupta P, Fowler CJ, Anand P. Decreased sensory receptors P2X3 and TRPV1 in suburothelial nerve fibers following intradetrusor injections of botulinum toxin for human detrusor overactivity. J Urol 2005; 174: 977–982. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000169481.42259.54, discussion 982-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Morenilla-Palao C, Planells-Cases R, Garcia-Sanz N, Ferrer-Montiel A. Regulated exocytosis contributes to protein kinase C potentiation of vanilloid receptor activity. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 25665–25672. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M311515200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Min JW, Liu WH, He XH, Peng BW. Different types of toxins targeting TRPV1 in pain. Toxicon 2013; 71: 66–75. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Camprubí-Robles M, Planells-Cases R, Ferrer-Montiel A. Differential contribution of SNARE‐dependent exocytosis to inflammatory potentiation of TRPV1 in nociceptors. Faseb J 2009; 23: 3722–3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ma RSY, Kayani K, Whyte-Oshodi D, Whyte-Oshodi A, Nachiappan N, Gnanarajah S, Mohammed R. Voltage gated sodium channels as therapeutic targets for chronic pain. J Pain Res 2019; 12: 2709–2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wang J, Ou SW, Wang YJ. Distribution and function of voltage-gated sodium channels in the nervous system. Channels 2017; 11: 534–554. DOI: 10.1080/19336950.2017.1380758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hoeijmakers JG, Faber CG, Merkies IS, Waxman SG. Channelopathies, painful neuropathy, and diabetes: which way does the causal arrow point? Trends Mol Med 2014; 20: 544–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Huang J, Han C, Estacion M, Vasylyev D, Hoeijmakers JG, Gerrits MM, Tyrrell L, Lauria G, Faber CG, Dib-Hajj SD, Merkies IS, Waxman SG, PROPANE Study Group . Gain-of-function mutations in sodium channel Na(v)1.9 in painful neuropathy. Brain 2014; 137: 1627–1642. DOI: 10.1093/brain/awu079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Theile JW, Cummins TR. Recent developments regarding voltage-gated sodium channel blockers for the treatment of inherited and acquired neuropathic pain syndromes. Front Pharmacol 2011; 2: 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG. Diversity of composition and function of sodium channels in peripheral sensory neurons. Pain 2015; 156: 2406–2407. DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bourinet E, Francois A, Laffray S. T-type calcium channels in neuropathic pain. Pain 2016; 157 Suppl 1(Suppl 1): S15–S22. DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nowycky MC, Fox AP, Tsien RW. Three types of neuronal calcium channel with different calcium agonist sensitivity. Nature 1985; 316: 440–443. DOI: 10.1038/316440a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bourinet E, Altier C, Hildebrand ME, Trang T, Salter MW, Zamponi GW. Calcium-permeable ion channels in pain signaling. Physiol Rev 2014; 94: 81–140. DOI: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chen WK, Liu IY, Chang YT, Chen YC, Chen CC, Yen CT, Shin HS, Chen CC. Ca(v)3.2 T-type Ca2+ channel-dependent activation of ERK in paraventricular thalamus modulates acid-induced chronic muscle pain. J Neurosci 2010; 30: 10360–10368. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1041-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Park C, Kim J-H, Yoon B-E, Choi E-J, Lee CJ, Shin H-S. T-type channels control the opioidergic descending analgesia at the low threshold-spiking GABAergic neurons in the periaqueductal gray. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107: 14857–14862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jagodic MM, Pathirathna S, Nelson MT, Mancuso S, Joksovic PM, Rosenberg ER, Bayliss DA, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM. Cell-specific alterations of T-type calcium current in painful diabetic neuropathy enhance excitability of sensory neurons. J Neurosci 2007; 27: 3305–3316. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4866-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cao XH, Byun HS, Chen SR, Pan HL. Diabetic neuropathy enhances voltage-activated Ca2+ channel activity and its control by M4 muscarinic receptors in primary sensory neurons. J Neurochem 2011; 119: 594–603. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07456.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jagodic MM, Pathirathna S, Joksovic PM, Lee W, Nelson MT, Naik AK, Su P, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM. Upregulation of the T-type calcium current in small rat sensory neurons after chronic constrictive injury of the sciatic nerve. J Neurophysiol 2008; 99: 3151–3156. DOI: 10.1152/jn.01031.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wen XJ, Xu SY, Chen ZX, Yang CX, Liang H, Li H. The roles of T-type calcium channel in the development of neuropathic pain following chronic compression of rat dorsal root ganglia. Pharmacology 2010; 85: 295–300. DOI: 10.1159/000276981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yue J, Liu L, Liu Z, Shu B, Zhang Y. Upregulation of T-type Ca2+ channels in primary sensory neurons in spinal nerve injury. Spine 2013; 38: 463–470. DOI: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318272fbf8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Okubo K, Takahashi T, Sekiguchi F, Kanaoka D, Matsunami M, Ohkubo T, Yamazaki J, Fukushima N, Yoshida S, Kawabata A. Inhibition of T-type calcium channels and hydrogen sulfide-forming enzyme reverses paclitaxel-evoked neuropathic hyperalgesia in rats. Neuroscience 2011; 188: 148–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Okubo K, Takahashi T, Sekiguchi F, Kanaoka D, Matsunami M, Ohkubo T, Yamazaki J, Fukushima N, Yoshida S, Kawabata A. Inhibition of T-type calcium channels and hydrogen sulfide-forming enzyme reverses paclitaxel-evoked neuropathic hyperalgesia in rats. Neuroscience 2011; 188: 148–156. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kawabata A. Targeting Ca (v) 3.2 T-type calcium channels as a therapeutic strategy for chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain. Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi 2013; 141: 81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Flatters SJ, Bennett GJ. Ethosuximide reverses paclitaxel- and vincristine-induced painful peripheral neuropathy. Pain 2004; 109: 150–161. DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Shin JB, Martinez-Salgado C, Heppenstall PA, Lewin GR. A T-type calcium channel required for normal function of a mammalian mechanoreceptor. Nat Neurosci 2003; 6: 724–730. DOI: 10.1038/nn1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Takahashi T, Aoki Y, Okubo K, Maeda Y, Sekiguchi F, Mitani K, Nishikawa H, Kawabata A. Upregulation of Ca(v)3.2 T-type calcium channels targeted by endogenous hydrogen sulfide contributes to maintenance of neuropathic pain. Pain 2010; 150: 183–191. DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Fukuizumi T, Ohkubo T, Kitamura K. Spinally delivered N-P/Q- and L-type Ca2+-channel blockers potentiate morphine analgesia in mice. Life Sci 2003; 73: 2873–2881. DOI: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00700-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Michaluk J, Karolewicz B, Antkiewicz-Michaluk L, Vetulani J. Effects of various Ca2+ channel antagonists on morphine analgesia, tolerance and dependence, and on blood pressure in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol 1998; 352: 189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Matthews EA, Dickenson AH. Effects of spinally delivered N- and P-type voltage-dependent calcium channel antagonists on dorsal horn neuronal responses in a rat model of neuropathy. Pain 2001; 92: 235–246. DOI: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00255-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Burnstock G, Wood JN. Purinergic receptors: their role in nociception and primary afferent neurotransmission. Curr Opin Neurobiol 1996; 6: 526–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Inoue K, Tsuda M, Koizumi S. ATP receptors in pain sensation: involvement of spinal microglia and P2X 4 receptors. Purinergic Signal 2005; 1: 95–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zhang X, Li G. P2Y receptors in neuropathic pain. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2019; 186: 172788. DOI: 10.1016/j.pbb.2019.172788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bernier LP, Ase AR, Seguela P. P2X receptor channels in chronic pain pathways. Br J Pharmacol 2018; 175: 2219–2230. DOI: 10.1111/bph.13957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kuan YH, Shyu BC. Nociceptive transmission and modulation via P2X receptors in central pain syndrome. Mol Brain 2016; 9: 58. DOI: 10.1186/s13041-016-0240-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ma H, Meng J, Wang J, Hearty S, Dolly JO, O'Kennedy R. Targeted delivery of a SNARE protease to sensory neurons using a single chain antibody (scFv) against the extracellular domain of P2X(3) inhibits the release of a pain mediator. Biochem J 2014; 462: 247–256. DOI: 10.1042/BJ20131387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Jorge CO, de Azambuja G, Gomes BB, Rodrigues HL, Luchessi AD, de Oliveira-Fusaro MCG. P2X3 receptors contribute to transition from acute to chronic muscle pain. Purinergic Signal 2020; 16: 403–414. DOI: 10.1007/s11302-020-09718-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ge C, Huang H, Huang F, Yang T, Zhang T, Wu H, Zhou H, Chen Q, Shi Y, Sun Y, Liu L, Wang X, Pearson RB, Cao Y, Kang J, Fu C. Neurokinin-1 receptor is an effective target for treating leukemia by inducing oxidative stress through mitochondrial calcium overload. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019; 116: 19635–19645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Iadarola MJ, Sapio MR, Wang X, Carrero H, Virata-Theimer ML, Sarnovsky R, Mannes AJ, FitzGerald DJ. Analgesia by deletion of spinal neurokinin 1 receptor expressing neurons using a bioengineered substance P-Pseudomonas exotoxin conjugate. Mol Pain 2017; 13: 1744806917727657. DOI: 10.1177/1744806917727657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Patacchini R, Lecci A, Holzer P, Maggi CA. Newly discovered tachykinins raise new questions about their peripheral roles and the tachykinin nomenclature. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2004; 25: 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Werge T. The tachykinin tale: molecular recognition in a historical perspective. J Mol Recognit 2007; 20: 145–153. DOI: 10.1002/jmr.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Zhang S, Li K, Yu Z, Chai J, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Min P. Dramatic effect of botulinum toxin type A on hypertrophic scar: a promising therapeutic drug and its mechanism through the SP-NK1R pathway in cutaneous neurogenic inflammation. Front Med 2022; 9: 820817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Pereira V, Goudet C. Emerging trends in pain modulation by metabotropic glutamate receptors. Front Mol Neurosci 2018; 11: 464. DOI: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zhou HY, Chen SR, Pan HL. Targeting N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors for treatment of neuropathic pain. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2011; 4: 379–388. DOI: 10.1586/ecp.11.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Osikowicz M, Mika J, Przewlocka B. The glutamatergic system as a target for neuropathic pain relief. Exp Physiol 2013; 98: 372–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Wang Y, Wu J, Wu Z, Lin Q, Yue Y, Fang L. Regulation of AMPA receptors in spinal nociception. Mol Pain 2010; 6: 5. DOI: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kopach O, Voitenko N. Spinal AMPA receptors: amenable players in central sensitization for chronic pain therapy? Channels 2021; 15: 284–297. DOI: 10.1080/19336950.2021.1885836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Chen Y, Derkach VA, Smith PA. Corrigendum to “Loss of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors in synapses of tonic firing substantia gelatinosa neurons in the chronic constriction injury model of neuropathic pain” Exp Neurol 2016; 286: 150. DOI: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Dušan P, Tamara I, Goran V, Gordana M-L, Amira P-A. Left ventricular mass and diastolic function in obese children and adolescents. Pediatr Nephrol 2015; 30: 645–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Galan A, Laird JMA, Cervero F. In vivo recruitment by painful stimuli of AMPA receptor subunits to the plasma membrane of spinal cord neurons. Pain 2004; 112: 315–323. DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Latacz G, Sałat K, Furgała-Wojas A, Martyniak A, Olejarz-Maciej A, Honkisz-Orzechowska E, Szymańska E. Phenylalanine-based AMPA receptor antagonist as the anticonvulsant agent with neuroprotective activity—in vitro and in vivo studies. Molecules 2022; 27: 875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Gormsen L, Finnerup NB, Almqvist PM, Jensen TS. The efficacy of the AMPA receptor antagonist NS1209 and lidocaine in nerve injury pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, three-way crossover study. Anesth Analg 2009; 108: 1311–1319. DOI: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318198317b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Rocha Barreto R, Lima Veras PJ, de Oliveira Leite G, Vieira-Neto AE, Sessle BJ, Villaça Zogheib L, Rolim Campos A. Botulinum toxin promotes orofacial antinociception by modulating TRPV1 and NMDA receptors in adult zebrafish. Toxicon 2022; 210: 158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.McNicol ED, Midbari A, Eisenberg E. Opioids for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 2013: CD006146. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006146.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Thompson SJ, Pitcher MH, Stone LS, Tarum F, Niu G, Chen X, Kiesewetter DO, Schweinhardt P, Bushnell MC. Chronic neuropathic pain reduces opioid receptor availability with associated anhedonia in rat. Pain 2018; 159: 1856–1866. DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Brown CA, Matthews J, Fairclough M, McMahon A, Barnett E, Al-Kaysi A, El-Deredy W, Jones AK. Striatal opioid receptor availability is related to acute and chronic pain perception in arthritis: does opioid adaptation increase resilience to chronic pain? Pain 2015; 156: 2267–2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.DosSantos MF, Martikainen IK, Nascimento TD, Love TM, Deboer MD, Maslowski EC, Monteiro AA, Vincent MB, Zubieta JK, DaSilva AF. Reduced basal ganglia mu-opioid receptor availability in trigeminal neuropathic pain: a pilot study. Mol Pain 2012; 8: 74. DOI: 10.1186/1744-8069-8-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Maarrawi J, Peyron R, Mertens P, Costes N, Magnin M, Sindou M, Laurent B, Garcia-Larrea L. Differential brain opioid receptor availability in central and peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain 2007; 127: 183–194. DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Klega A, Eberle T, Buchholz HG, Maus S, Maihofner C, Schreckenberger M, Birklein F. Central opioidergic neurotransmission in complex regional pain syndrome. Neurology 2010; 75: 129–136. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e7ca2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Harris RE, Clauw DJ, Scott DJ, McLean SA, Gracely RH, Zubieta JK. Decreased central mu-opioid receptor availability in fibromyalgia. J Neurosci 2007; 27: 10000–10006. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2849-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Sprenger T, Willoch F, Miederer M, Schindler F, Valet M, Berthele A, Spilker ME, Forderreuther S, Straube A, Stangier I, Wester HJ, Tolle TR. Opioidergic changes in the pineal gland and hypothalamus in cluster headache: a ligand PET study. Neurology 2006; 66: 1108–1110. DOI: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000204225.15947.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Petraschka M, Li S, Gilbert TL, Westenbroek RE, Bruchas MR, Schreiber S, Lowe J, Low MJ, Pintar JE, Chavkin C. The absence of endogenous beta-endorphin selectively blocks phosphorylation and desensitization of mu opioid receptors following partial sciatic nerve ligation. Neuroscience 2007; 146: 1795–1807. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Hoot MR, Sim-Selley LJ, Selley DE, Scoggins KL, Dewey WL. Chronic neuropathic pain in mice reduces mu-opioid receptor-mediated G-protein activity in the thalamus. Brain Res 2011; 1406: 1–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Costa AR, Carvalho P, Flik G, Wilson SP, Reguenga C, Martins I, Tavares I. Neuropathic pain induced alterations in the opioidergic modulation of a descending pain facilitatory area of the brain. Front Cell Neurosci 2019; 13: 287. DOI: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Drinovac V, Bach-Rojecky L, Matak I, Lackovic Z. Involvement of mu-opioid receptors in antinociceptive action of botulinum toxin type A. Neuropharmacology 2013; 70: 331–337. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Li C, Lei Y, Tian Y, Xu S, Shen X, Wu H, Bao S, Wang F. The etiological contribution of GABAergic plasticity to the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain. Mol Pain 2019; 15: 1744806919847366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Brewer AL, Liu S, Buhler AV, Shirachi DY, Quock RM. Role of spinal GABA receptors in the acute antinociceptive response of mice to hyperbaric oxygen. Brain Res 2018; 1699: 107–116. DOI: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]