Abstract

Occupational health has evolved as a field over the last 20 years, most significantly over the last 2 years. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the amount and complexity of challenges for occupational health professionals and at the same time provided a unique opportunity for the field in light of the heightened focus on health at the workplace. Responsibilities have become broader and more multi-faceted including areas such as mental wellbeing and psychosocial risk factors. The pandemic has shown us that the workplace is an essential setting to promote health with a growing number of employers investing in policies and programs for their employees. However, many global health campaigns and large scale national initiatives do not include the workplace setting in their strategy to the detriment of the their effectiveness. In addition to the pressing global health needs, two recent developments have propelled workplace health to the forefront and are asking questions of employers. The Sustainable Development Goals as well as the ESG (Environment, Social, Governance) agenda on behalf of the financial sector are pushing the corporate sector to act responsibly beyond seeking profits and disclose related policies and actions. Healthy workplaces are essential for global development and progress.

Keywords: Occupational health; healthy workplaces; psychosocial risk management; Environment, Social and Governance; workplace wellbeing

“The understanding of health has evolved to a broader concept of wellbeing, and siloed occupational health services have transformed into comprehensive healthy workplace strategies involving various different business units.”

Introduction

The field of occupational health has undergone significant changes over the last 20 years with a changing working world, rise in technology, globalization, demographic shifts, and various political and economic changes. 1 The field is in the middle of a significant transformation reacting to an extensively altered landscape. 2 The past few years of the global COVID-19 pandemic have only intensified and accelerated this transformation moving occupational health to the forefront of business issues and decisions. It is therefore very timely to take a close look at the field and review the current status. The global pandemic still requires our attention as a whole and remains the key focus of occupational health (OH) professionals who are doing their best to keep employees healthy. It has become clear that job responsibilities have significantly changed for OH professionals requiring added skills and expertise. Taking care and enhancing the health of employees is a multidisciplinary task beyond the core OH task of shielding the employee from physical health-related workplace risks. For one, psychosocial risks have become a central focus with regard to enhancing mental health, and, furthermore, employees are being helped to improve their health behaviors and develop their personal health resources. These developments coupled with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic present a huge opportunity for the OH field to become an essential workplace service and raise its visibility and standing on a global scale.

This review article will take a global and analytical look at the evolution of occupational health and what the global pandemic means for the future of the field.

Global Trends in Workplace Health

According to the joint estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO) and International Labor Organization (ILO), work-related diseases and injuries were responsible for the deaths of 1.9 million people in 2016. 3 Non-communicable diseases accounted for 81% of the deaths, for example, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, and ischaemic heart disease. Work-related injuries caused 19% of deaths (360 000 deaths). The exposure to long working hours was also tracked and linked to approximately 750 000 deaths. Workplace exposure to air pollution was estimated to be responsible for 450 000 deaths. These figures are shocking and serve as a wake-up call for employers, governments, and occupational health professionals alike to better protect the health and safety of workers. While the overall number of deaths has declined since 2000, exposure to psychosocial occupational risk factors has increased. 3 The next report will be especially interesting in light of the impact of the COVID-19 on the total work-related burden of disease.

Encouraging are the latest workplace wellbeing trends from the Aon 2021 4 Global Wellbeing Survey. 82% of surveyed companies (1648 companies in 41 countries) regard wellbeing as important for their company, 87% have a wellbeing initiative in place while 55% have a wellbeing strategy in place. Key drivers for implementing wellbeing initiatives are improving employees’ satisfaction and engagement, improving worklife balance, reducing employee stress, improving employee productivity, and increasing employee loyalty. As major challenges, the surveyed companies identified financial resources and investment, measuring the return of actions being implemented, and employee engagement. Employee engagement is the third most important measure of company performance after profit and customer satisfaction. The Aon survey also outlines the key challenges and wellbeing risks, which impact company performance: stress, burnout, anxiety, depression, musculoskeletal conditions, and physical inactivity.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has been monitoring the quality of the working environment 5 due to its significant role in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). 6 Goal 8 is to “protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers.” Job quality also plays a central role in the OECD Jobs Strategy. The most recent analysis of 28 OECD countries looked at how the demands of the job and the resources that are available to workers to meet those demands were balanced. The study revealed that one third of employees are (moderately or heavily) strained at work, while one half are well-resourced. 10% of employees are heavily strained. 5 Differences in job strain exist across education, industry, occupation, and employment status categories. Low skill and low educated workers (agriculture, construction, and industry) report more frequently being highly or moderately strained. The quality of the working environment is strongly associated with workers’ wellbeing, days of sickness, job satisfaction as well as job motivation.

The need for more preventive and innovative actions and policies is evident. A more comprehensive and integrated approach to occupational health is called for, which this article will lay out and emphatically recommend.

The Workplace as an Essential Setting to Improve Health

Employing the workplace as a setting to promote health is a comparably novel approach in the overall history of health and medicine. The workplace has been regarded as a potential risk to worker health as far back as 400 BC when Hippocrates recognized lead poisoning in miners. 7 Bernardino Ramazzini, considered the father of occupational medicine, maintained the view “that workplace analysis can identify potential and actual hazards to workers’ health.” 8 Many studies in the OH field have been focused on how to minimize or eliminate these risks. This focus has evolved with the workplace now being regarded as one of the priority settings for health promotion into the 21st century. The World Health Organization (WHO) has promoted the healthy settings approach since the Health for All strategy in 1980 9 underlining the value of settings for implementing comprehensive strategies and providing an infrastructure for health promotion. However, this thinking has not been widely supported by employers, as uptake of workplace health promotion has been slow and with significant regional differences. 10 The United States has a long tradition of promoting healthy behaviors via the workplace 11 whereas for example, in Asia, this approach is relatively new. 9 No doubt has the COVID-19 pandemic put health at the center of the workplace, but it is too early to tell whether this development will result in long-term investment in employee health.

The workplace is a key setting for promoting health as the working population spends most of their time at the workplace, wherever it may be. The working environment may have changed considerably during the last 2 years but utilizing the work relationship as a channel to promote health and wellbeing remains an opportunity not to be missed. The potential to improve health and quality of life is enormous and employers and employees alike benefit from the introduction of health promotion at the workplace—a so-called win-win situation. Employers benefit from more productive and motivated employees generating less health care costs and employees enjoy better health and enhanced quality of life. The third win could be for overall global health due to the potential to reduce the non-communicable disease burden as well as preventable deaths. As stated above, a high number of preventable deaths are attributed to the exposure to long working hours as well as to air pollution.

Linking Occupational Health and Public Health

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Labor Organization (ILO) adopted a common definition of occupational health in 1950 (revised in 1995):

“Occupational health should aim at the promotion and maintenance of the highest degree of physical, mental and social well-being of workers in all occupations; the prevention amongst workers of departures from health caused by their working conditions; the protection of workers in their employment from risks resulting from factors adverse to health; the placing and maintenance of the worker in an occupational environment adapted to his physiological and psychological capabilities and; to summarize: the adaptation of work to man and of each man to his job.”9,12

The ILO has been providing international guidelines and a legal framework for the development of occupational health policies and infrastructures on a tripartite basis (including governments, employers, and workers). The WHO is focused on advancing public health and primary care through scientific evidence, methodologies, technical support. 7 While public health and occupational health have many common goals, like health protection or health equity, the integration of the two fields has been lagging globally. In 2007, the WHO endorsed the Workers’ Health: A Global Plan of Action, which planted the seed of promoting health at the workplace and provided the impetus for the WHO Healthy Workplace Model for Action. 13

The Healthy Workplace Model

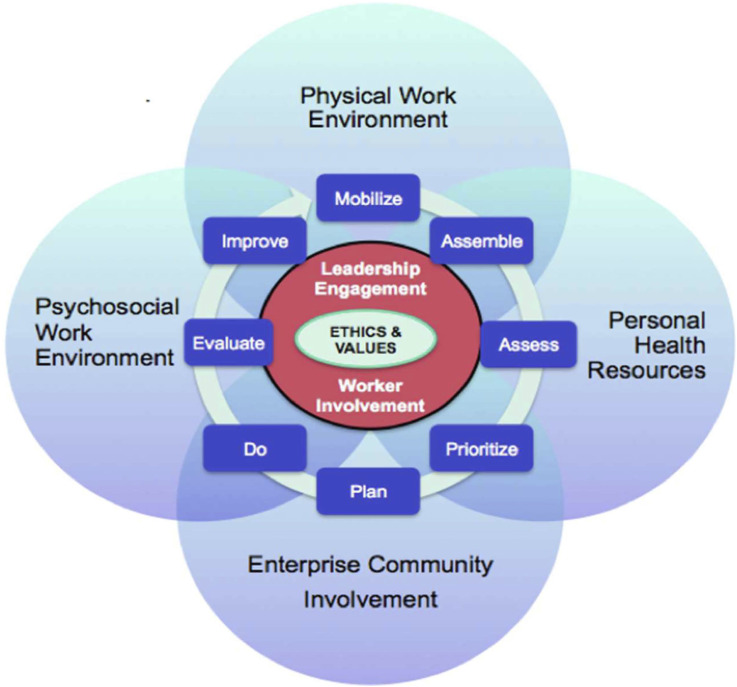

The Healthy Workplace model was developed in 2010 and brings together traditional occupational health, health promotion and enterprise involvement in the community to address broader social and environmental determinants of workers’ health. 14 It conceptualizes a holistic effort to address worker health needs including workplace health promotion, hazard prevention, and the organization of work. With the model, the WHO emphasizes that creating healthy workplaces is from a business perspective “not only the right thing to do but also the smart thing to do.” The model for action provides a framework for creating healthy workplaces and is adaptable to diverse countries, cultures and workplaces. While following a continuous improvement process, the model outlines four interrelated areas:

• Physical work environment

• Psychosocial work environment

• Personal health resources

• Enterprise community involvement

Programs in the various areas need to be implemented as part of a continual improvement process, which ensures needs are met and that the program is sustainable. Unfortunately, many workplace health programs are not rigorously evaluated and employers do not know whether they are effective. 14 The model features key underlying principles that are indispensable for the success of a healthy workplace program. The program needs to be integrated into the organization’s business strategy and management systems, which is coupled with leadership engagement. Without the commitment and support of senior leaders, the program is highly unlikely to succeed. This includes incorporating health and wellbeing into corporate business planning from the outset, and not reactively when business continuity is imminently threatened. Likewise is the involvement of workers and their representatives of utmost importance. Affected workers should be actively involved in every step of the process. 15 Upon review of successful workplace inventions, Schnall, Dobson, and Rosskam make the case that “… strong collective voice is the singularly most important element found among all of the various interventions described. To date, few work organization change initiatives have succeeded in the absence of strong collective voice.” 16 Workers need to have a voice that is stronger than that of the individual worker and trade unions or worker representatives can provide this voice (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Healthy Workplace model for action. It was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2010.

One element often overlooked or neglected is the integration of the different program components and units involved. This is particularly relevant in large organizations in which many units touch upon and address the health employees: health and safety, medical services, wellness, human resources, sustainability, diversity and inclusion, etc. Enhanced integration is called for, for example, via the use of cross-functional teams and matrices as well as applying a healthy and safety filter to all business decisions.

A Holistic Understanding of Wellbeing

At the basis of a more comprehensive approach to occupational health is a holistic and positive understanding of health and wellbeing. The biopsychosocial model of health expands on the biomedical model and features social, psychological and behavioral dimensions. 17 The approach leads to more patient-centered care and more effective outcomes, in particular with chronic illness which requires the modification of health risk behaviors and the environments that reinforce these. Closely linked to this thinking is Michael Marmot’s work on the social determinants of health, 18 which stresses the influence of living and working conditions (quality schooling, affordable housing, fair pay, safe neighborhoods) on one’s health and the significant health inequalities it has led to. While Marmot has been researching the link for decades and the WHO focusing on this issue since the early 2000s social determinants of health have received more attention recently with the social justice movement in the United States. The evolution of the biomedical model has also led to the advent of the wellbeing concept which is now being promoted by the WHO. In the Geneva Charter for Wellbeing, the WHO advocates for a positive vision of health integrating physical, mental, spiritual, and social wellbeing. 19 Gallup has been gathering wellbeing data since 2008 and created the wellbeing index in 2012. The index features 5 interrelated elements that make up wellbeing: sense of purpose, social relationships, financial security, relationship to community, and physical health. 20 The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) updated their Total Worker Health concept to feature biopsychosocial perspectives more explicitly, for example, psychosocial hazards and exposures, organization of work, compensation and benefits, built environment supports, and worklife integration. 21 In addition to the development of a conceptual framework for worker wellbeing, NIOSH, in partnership with the RAND Corporation, operationalized the concept and provided a practical approach for measurement and action, which included 5 domains (workplace physical environment and safety climate, workplace policies and culture, health status, work evaluation and experience, home, community and society) and twenty subdomains 22 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Worker WellBeing. Framework was developed by NIOSH and the Rand Corporation in 2018.

This approach has guided the development of the Worker WellBeing Questionnaire (NIOSH WellBQ) and is intended for real-world application. 23

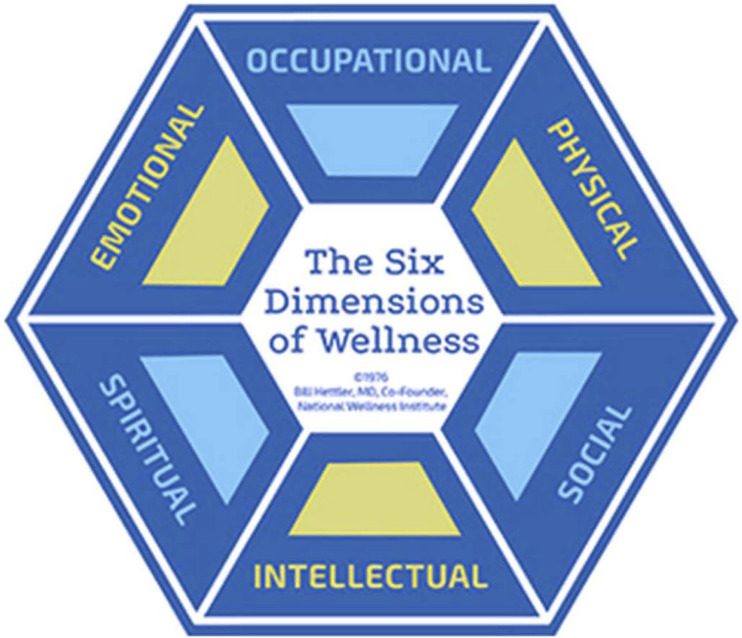

As far back as 1976, the National Wellness Institute promoted a holistic approach to health with the 6 dimensions of wellness 24 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Six Dimensions of Wellness.

According to the Aon Global Wellbeing Survey, 4 70% of companies incorporate physical wellbeing into their strategy, 67% emotional wellbeing, 65% social wellbeing, 54% financial wellbeing, and 68% career wellbeing.

The wellbeing concept is significant for the ongoing development of the occupational health field and the expansion of the scope of work of occupational health professionals.

Workplace Health in the Spotlight

Before we take a look at how the evolution from occupational health to healthy workplaces has changed the role of occupational health (OH) professionals, we need to reflect on what has happened over the last 2 years. Without a doubt has the COVID-19 pandemic propelled employee health to the forefront and the OH profession into the spotlight. 25 Company physicians have become lead experts in the consultation of corporate policies and strategies with direct access to the executive level. At the same time, existing health issues and their underlying factors were laid bare and their impact significantly increased, for example, the mental and physical costs of isolation and loneliness. 25 On top of that, working arrangements and environments have changed significantly with the rapid advent of virtual and flexible working. While the predictions vary, it is widely agreed that flexible working will be a key feature of the working world in the future. The Work After Lockdown research project in the United Kingdom found a strong workforce demand for hybrid working, that is, 73% of employees wished to adopt a hybrid work arrangement to retain the flexibility and control over their working pattern from which they have benefited under lockdown. 26 Naturally have the changes in working arrangements modified health risk profiles of employees as well as program delivery in a major way, for example, ergonomic assessments and programs for home office workers. 4 A major barrier to social wellbeing is working remotely as well as pandemic-related social distancing requirements. These trends reflect a global phenomenon. Large parts of the working population will remain working from home across the world albeit with local variations, for example, countries with large industry sectors will have less homeworkers than service-oriented. These developments provide a massive opportunity for occupational health professionals to play a more prominent role within corporations and make sustained progress towards creating healthy workplaces. Two consequential developments, which have gained momentum during the pandemic need to be pointed out:

1. The pressing need for psychosocial risk management

2. The role of health in Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) analysis (evaluating a company’s policies and practices in the three areas) and reporting.

Psychosocial Risk Management

One area from the WHO Healthy Workplace model which justifiably has received more attention since the COVID-19 pandemic started is psychosocial risk management. The pandemic is showing us how unpredictability is impacting our mental wellbeing, how the interface of home and work has become ever more complex, and how important the psychological safety of employees is. While psychosocial risk management has been referenced in research, policy, legislation, and intervention design for many years,27,29 a large number of employers have not embraced this key focus of creating healthy workplaces. OH professionals are well versed in risk management, mostly focused on physical risk factors, for example, related to chemical, biological, and ergonomic hazards. Therefore, an extension of the risk management approach to include psychosocial hazards is not far-fetched and often becomes the responsibility of the OH professional. Psychosocial hazards are defined as “those aspects of work design and the organization and management of work, and their social and environmental contexts, which have the potential for causing psychological, social or physical harm” 28 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of Psychosocial Hazards (Worksafe NZ). 13

| Area | Examples |

|---|---|

| Job contents/demands | High physical, emotional, or mental demands, overload |

| Work schedule | Shift working, inflexible hours |

| Job control | Low participation in decision making |

| Physical environment/equipment | Poor conditions |

| Organizational culture | Poor communication |

| Interpersonal relationships | Lack of social support from superior or colleagues |

| Role in organization | Role ambiguity |

| Career development | Career stagnation, job insecurity |

Psychosocial risks refer to the potential of a hazard occurring and the likelihood it will cause harm. 24 The risk management process starts with a psychosocial risk assessment, which is required by law in a number of countries. The European Economic Community (EEC) Council Directive 89/391 in 1989 specifies the employer’s responsibility to assess and manage of all types of risks to workers’ health including psychosocial factors. 27 According to a study by Chirico et al., 30 47 countries (out of 132 reviewed) included mandatory psychosocial risk assessment and prevention in their national occupational safety and health legislation. However, in many of these countries, actual implementation and enforcement are lacking. Numerous assessment tools exist in various countries, such as the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ) 31 and the Psychosocial Safety Climate instrument (PSC-12) 32 from Australia, as well as guidance documents and standards. In 2021 the International Standards Organization (ISO) released the 45 003 standard focusing on “Psychological health and safety at work—Guidelines for managing psychosocial risks.” This will provide an added impetus for employers to move to psychosocial risk management. Furthermore, the OECD has recognized the improvement of the quality of the working environment as a policy priority and has included job quality as part of their Job Strategy. 5 The framework features key job characteristics such as the physical and social environment, job tasks, organizational characteristics, working time arrangements, job prospects, and intrinsic job aspects.

Occupational Health and Environment, Social, Governance

When reviewing the state of the field of occupational health and looking into the future opportunities for professionals, it is imperative to discuss the increasing significance of sustainable business practices and the surging interest in environmental, social, and governance matters (ESG) on behalf of investors, consumers, and corporate stakeholders. 33 Health and safety is nestled under the “S,” which covers human capital and social justice issues, such as diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). Addressing structural racism, lack of living wages, and health inequities amongst the employee population as well as the supply chain have become a key element of corporate human capital strategies. 34

The case for aligning employee health and wellbeing with business performance is clear. Numerous studies over the past 30 years have demonstrated the link between poor employee health and increased health care costs, higher absenteeism rates, lower productivity, lower morale, and lesser engagement. 35 A number of studies have demonstrated that publicly traded companies with either award-winning health promotion programs or with high health and wellness index scores significantly outperform the tracked stock market index over a certain time frame.36,37 Employers that pursue health and wellbeing strategies for their employees often have well developed sustainability policies covering a range of ESG factors. What is less clear is how such findings are understood by investors and to what extent it influences their decisions on valuing their portfolio and in allocating investments. The 2015 CFA Institute ESG Survey found that human capital, which is highly impacted by employee health, was the second most important issue in their members’ investment analysis and decisions. 38 There is growing interest and activity in the financial community with regard to incorporating health-related criteria in investment analysis in relation to ESG and the leading international frameworks are expanding their standards, for example, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). 33

The challenge remains to recommend metrics which accurately reflect corporate health and wellbeing and which companies can readily track at the same time. No doubt is the potential for growth and increased awareness of occupational health substantial once the investor community takes serious note whether companies are creating healthy workplaces.

Tracking Health and Business Metrics

While challenging it is imperative that organizations evaluate their health and wellbeing programs and generate and track health-related and business metrics. As described above with the Healthy Workplace model for action, this is an integral step of the continuous improvement process. 14 Companies often tend to track longstanding, conventional indicators such as fatalities or lost time injury frequency rate. Health and wellbeing are complex constructs, which require additional indicators. Deciding on what indicators are most relevant and how to measure them can be inconvenient as it involves different business units (e.g., HR, safety, and health services), quantitative as well as qualitative data, and utilizing a variety of types of instruments not readily available. The Healthy Workplace model can serve as a guiding framework to develop relevant metrics. One guiding principle is to collect data in all four areas and include leading as well as lagging indicators (Table 2).

Table 2.

Healthy Workplace Indicators.

| Area | Indicator |

|---|---|

| Physical work environment | Occupational injury, disease, accident rates |

| Psychosocial work environment | Psychosocial risks, engagement, turnover, workplace climate, percentage of employees making living wage |

| Personal health resources | Health status, health risks, health behaviors |

| Enterprise community involvement | Engagement with local community programs, health services offered to dependents and the community |

Another promising strategy is to share key metrics with leadership and the employee population, that is, being transparent and celebrating progress together. Senior leaders will have limited time and focus to track health-related indicators, so it is important to decide which leading metrics make it to the executive dashboard. One example is the engagement or people survey, which is conducted annually by many companies and for which senior leaders get to see the results. Engagement surveys lend themselves to analyze psychosocial factors such as job satisfaction, trust, and worklife balance. Lastly, the data should be used to change course, if necessary, address emerging needs, develop action plans as well as improve existing programs.

The Evolving Role of the Occupational Health Professional

What does the advent of new health challenges and working life as well as the evolution of the healthy workplace concept mean for the OSH professional? Bevan and Cooper 25 maintain that OH doctors and nurses have come out of the shadows during the pandemic. Their specialist knowledge is very much needed, for example, risk assessment and prevention, as is their biopsychosocial approach to workplace wellbeing. Bevan and Cooper 25 go on to demand more opportunities for the OH professional to give advice to the CEO and have input on business strategies.

With opportunities growing, the OH professional needs to be prepared for more challenging and varied tasks and demands. The field is evolving rapidly and the list of competencies is getting longer. The American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (ACOEM) identified the 10 core competencies for occupational and environmental medicine (OEM): clinical occupational and environmental medicine, OEM related law and regulations, environmental health, work fitness and disability management, toxicology, hazard recognition, evaluation, and control, disaster preparedness and emergency management, health and productivity, public health, surveillance, and disease prevention, and OEM related management and administration. 39 The American Association of Occupational Health Nurses (AAOHN) takes a broader approach with expanded competencies: Total Worker Health, culture of health safety, economics, principles of professional nursing practice, business climate and community health, and culturally appropriate, evidence-based nursing care within licensed scope of practice. 40 A Delphi study in the UK 41 concluded 12 domains of core competencies for occupational health nurses: general principles of assessment and management of occupational hazards to health, assessment of disability and fitness for work, health promotion, ethical and legal issues, clinical governance and clinical improvement, communication skills, team working and leadership skills, management skills, environmental issues related to work practice, teaching and education supervision, good clinical care, and research methods.

Two key aspects touched upon in the description of competencies are worthwhile pointing out:

1. Health literacy, specifically digital health literacy, which entails competencies and motivation to access, understand, appraise, and apply information in a digital context. This competency has become extremely important for health care professionals with the advent of misleading information (magnified through social media) as well as the general information overload.

2. The business orientation and needed skills to comprehend economic inferences as well as to engage key stakeholders. This includes the ability to speak in business-relevant terms, make the business case, and to clearly articulate the value proposition of investing in occupational health services (OHS).

Various occupational health curricula are applied globally, largely using approaches developed from old models of work and risks, 2 and slow in adapting to the new challenges and tasks. It is important for the OH professional to stay up-to-date and refresh their training when needed as well as follow the guidelines of active professional organizations in the field for example like ACOEM and AAOHN.

The Society of Occupational Medicine (SOM) report on the value proposition of occupational health 42 provides a number of compelling evidence-based arguments for the support of OHS. The two overarching reasons specified are ensuring compliance with regulations and enhancing organizational performance. Interestingly, non-tangible issues such as corporate image, retention and recruitment, and moral obligation played a bigger role in providing OHS compared to tangible cost issues. The report highlights the different aspects of the value proposition (legal, moral, business, financial) and cites comprehensive sources of evidence. With the difficulty of conducting quality economic evaluations, it is wise to position health as a social investment and not merely as a justifiable cost. OH professionals need to know the value of the services they provide and articulate such in an unembellished manner with the relevant evidence in hand.

Taking Advantage

The field of occupational health has evolved significantly over the last 20 years concurrent with the major changes in health risks at the workplace and in working environment and practices. Traditional occupational health and safety risks, such as exposure to asbestos or workplace accidents, have largely made way for psychosocial risks and non-communicable diseases exacerbated by work-related habits, for example, prolonged sitting. Not to minimize or underestimate the existing physical risks and resulting disease, injuries and fatalities, however, a shift to a different kind of risk has taken place. The understanding of health has evolved to a broader concept of wellbeing, and siloed occupational health services have transformed into comprehensive healthy workplace strategies involving various different business units. In addition, the sustainability movement is increasingly asking organizations to report on how they treat their workers and promote workers’ health, which is coupled to the financial sector focusing on ESG factors.

In particular, the last 2 years with the COVID-19 pandemic have added a layer of complexity and urgency within workplace health. For some time, occupational health was seemingly losing its status and standing in corporate circles before the global pandemic made it strikingly clear how important the role of OH professionals is. A justifiable concern is whether the global crisis will actually lead to sustained growth in corporate health strategies and comprehensive programming. Past crises have been met with reactive policies and actions, which lost its muster once the crises subsided. However, the COVID-19 pandemic represents a public health crisis impacting so many elements of our society and with such intensity, which we have not witnessed before. It is evident that OH professionals, and workplace health professionals on a broader scale, need to take advantage of the present opportunity before the spotlight fades.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Wolf Kirsten https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8060-6381

References

- 1.Schulte P, Delclos G, Felknor S, Chosewood LC. Toward an expanded focus for occupational safety and health: A commentary. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2019;16:4946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peckham T, Baker M, Camp J, Kaufman J, Seixas N. Creating a future for occupational health. Ann Work Expo Health. 2017;61(1):3-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO . WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-Related Burden of Disease and Injury, 2000-2016: Global Monitoring Report. Geneva: World Health Organization and the International Labour Organization; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4.AON Global Wellbeing Survey 2021.

- 5.Murtin F, Arnaud B, Le Th C, Parent-Thirion A. The Relationship Between Quality of the Working Environment, Workers’ Health And Well-Being: Evidence from 28 OECD Countries. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2022. OECD Papers on Well-being and Inequalities, No. 04. [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Nations . Making the SDGs a reality. https://sdgs.un.org/#goal_section. Accessed May 12, 2022.

- 7.Gochfeld M. Chronologic history of occupational medicine. J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47(2):96-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franco G. Ramazzini and workers’ health. Lancet. 1999;354(9181):858-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Creating health promoting settings . World Health Organization Western Pacific. https://www.who.int/westernpacific/activities/creating-health-promoting-settings. Accessed January 3, 2022.

- 10.Buck . Working well: A global survey of workplace wellbeing strategies. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reardon J. The history and impact of worksite wellness. Nurs Econ. 1998;16(3):117-121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ILO Encylopedia on Occupational Safety and Health . Occupational health services and practice. 2011. https://www.iloencyclopaedia.org/part-ii-44366/occupational-health-services/item/155-occupational-health-services-and-practice. February 11, 2011. Accessed December 14, 2021.

- 13.World Health Organization . Workers’ Health: Global Plan of Action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization . Healthy Workplace Model for Action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mansyur M. Occupational health, productivity and evidence-based workplace health intervention. Acta Med Philipp. 2021;55(6):602. Workplace and Environment Safety and Health Issue. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnall PL, Dobson M, Rosskam E, eds. Unhealthy Work: Causes, Consequences, Cures. Amityville, New York: Baywood Publishing Company Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beaumont D. Global concept: Heath. In: Australian Institute of Health & Safety (AIHS), the Core Body of Knowledge for Generalist OHS Professionals. 2nd ed. Tullamarine, VIC: AIHS; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marmot M. The health gap: The challenge of an unequal world. Lancet. 2015;386(10011):2442-2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization . Geneva charter for wellbeing. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/the-geneva-charter-for-well-being-(unedited). December 21, 2021. Accessed January 9, 2022.

- 20.Gallup . How does the Gallup-Sharecare Well-Being Index Work? https://www.gallup.com/175196/gallup-healthways-index-methodology.aspx. Accessed January 9, 2022.

- 21.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) . Fundamentals of Total Worker Health Approaches: Essential Elements for Advancing Worker Safety, Health, and Well-Being. Cincinnati, OH: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, NIOSH; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chari R, Chang C-C, Sauter S, et al. Expanding the paradigm of occupational safety and health: A new framework for worker wellbeing. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60(7):589-593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health . NIOSH Worker Well-Being Questionnaire (WellBQ). https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/twh/wellbq/default.html. .Accessed May 18, 2022.

- 24.National Wellness Institute . The six dimensions of wellness. https://nationalwellness.org/resources/six-dimensions-of-wellness/. Accessed January 11, 2022.

- 25.Bevan S, Cooper CL. The Healthy Workforce: Enhancing Wellbeing and Productivity in the Workers of the Future. Bingley: Emerald Publishing; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parry J, Young Z, Bevan S, et al. Working from Home under COVID-19 Lockdown: Transitions and Tensions. Work after Lockdown; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Worksafe New Zealand . Psychosocial Hazards in Work Environments and Effective Approaches for Managing Them; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cox T, Griffiths A, Rial-Gonzalez E. Research on Work Related Stress. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Psychosocial Risk Management Excellence Framework (PRIMA-EF) . Publicly available specification 1010. 2012. http://www.prima-ef.org/pas1010.html. Accessed January 17, 2022.

- 30.Chirico F, Heponiemi T, Pavlova M, Zaffina S, Magnavita N. Psychosocial risk prevention in a global occupational health perspective. A descriptive analysis. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2019;16(14):2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berthelsen H, Westerlund H, Bergström G, Burr H. Validation of the copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire version III and establishment of benchmarks for psychosocial risk management in Sweden. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17(9):3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hall G, Dollard M, Coward J. Psychosocial safety climate: Development of the PSC-12. Int J Stress Manag. 2010;17:353-383. doi: 10.1037/a0021320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance . Introduction to ESG. 2020. https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2020/08/01/introduction-to-esg/. Accessed January 17, 2022.

- 34.Gunter C, Baptista P. A Brave New World for Corporate Health & Wellbeing: A Key Sustainability Issue. Corporate Citizenship; 2022. https://corporate-citizenship.com/2022/01/25/a-brave-new-world-for-corporate-health-and-wellbeing-a-key-sustainability-issue/. January 25, 2022. Accessed January 17, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loeppke R, Taitel M, Haufle V, Parry T, Kessler RC, Jinnett K. Health and productivity as a business strategy: A multi-employer study. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(4):411-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fabius R, Loeppke RR, Hohn T, et al. Tracking the market performance of companies that integrate a culture of health and safety: An assessment of corporate health achievement award applicants. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58(1):3-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grossmeier J, Fabius R, Flynn J, et al. Linking workplace health promotion best practices and organizational financial performance: Tracking market performance of companies with highest scores on the HERO Scorecard. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58(1):16-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.CFA Institute . Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Survey. CFA Institute. June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hartenbaum NP, Baker BA, Levin JL, Saito K, Sayeed Y, Green-McKenzie J. ACOEM OEM Core Competencies: 2021. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63(7):e445-e461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.AAOHN . AAOHN competencies. Workplace Health & Saf. 2015;63(11):484-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lalloo D, Demou E, Kiran S, Gaffney M, Stevenson M, Macdonald EB. Core competencies for UK occupational health nurses: A Delphi study. Occup Med. 2016;66(8):649-655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nicholson PJ. Occupational Health: The Value Proposition. London: Society of Occupational Medicine; 2017. [Google Scholar]