Abstract

Protein kinases C (PKCs) are a family of serine/threonine kinases that are critical for signal transduction pathways involved in growth, differentiation and cell death. All PKC isoforms have four conserved domains, C1–C4. The C1 domain contains cysteine-rich finger-like motifs, which bind two zinc atoms. The zinc-finger motifs modulate diacylglycerol binding; thus, intracellular zinc concentrations could influence the activity and localization of PKC family members. 3T3 cells were cultured in zinc-deficient or zinc-supplemented medium for up to 32 h. Cells cultured in zinc-deficient medium had decreased zinc content, lowered cytosolic classical PKC activity, increased caspase-3 processing and activity, and reduced cell number. Zinc-deficient cytosols had decreased activity and expression levels of PKC-α, whereas PKC-α phosphorylation was not altered. Inhibition of PKC-α with Gö6976 had no effect on cell number in the zinc-deficient group. Proteolysis of the novel PKC family member, PKC-δ, to its 40-kDa catalytic fragment occurred in cells cultured in the zinc-deficient medium. Occurrence of the PKC-δ fragment in mitochondria was co-incident with caspase-3 activation. Addition of the PKC-δ inhibitor, rottlerin, or zinc to deficient medium reduced or eliminated proteolysis of PKC-δ, activated caspase-3 and restored cell number. Inhibition of caspase-3 processing by Z-DQMD-FMK (Z-Asp-Gln-Met-Asp-fluoromethylketone) did not restore cell number in the zinc-deficient group, but resulted in processing of full-length PKC-δ to a 56-kDa fragment. These results support the concept that intracellular zinc concentrations influence PKC activity and processing, and that zinc-deficiency-induced apoptosis occurs in part through PKC-dependent pathways.

Keywords: apoptosis, caspase-3, protein kinase C-α, protein kinase C-δ, 3T3 cell, zinc

Abbreviations: DAG, diacylglycerol; DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium; DOG, 1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycerol; DTPA, diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid; DTT, dithiothreitol; FBS, fetal bovine serum; ICP-AES, inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry; MARCKS, myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate; MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide; PKC, protein kinase C; PS, phosphatidylserine; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TTBS, Tween 20/Tris-buffered saline; Z-DQMD-FMK, Z-Asp-Gln-Met-Asp-fluoromethylketone

INTRODUCTION

Zinc has important structural and catalytic functions in numerous proteins that control gene expression, decipher endocrine signals, organize the extracellular matrix, regulate oxidative stress and catalyse essential metabolic events. In vitro or in vivo zinc deficiency results in growth arrest and ultimately cell death [1–5]. Modes of cell death include necrosis and apoptosis, the former often caused by an energy-independent catastrophic event occurring at the plasma membrane, whereas an energy-dependent genetically defined programme carries out the latter. A hallmark of apoptosis is the activation of caspases, a family of cysteine proteases initially synthesized as zymogens, but proteolytically processed into activated enzymes that subsequently target and deactivate cellular proteins essential for cell structures, metabolism and signaling. Activation of caspases has been reported in tissues and cells depleted of zinc. Supplementation with zinc reduces caspase activation and the cell death induced by zinc deficiency [5]. While some investigators have suggested that zinc acts directly to down-regulate caspases by binding to the catalytic cysteine of the active site in the enzyme, others suggest a role for zinc upstream from the proteolytic activation of effector caspases [6,7].

Apoptosis occurs via two predominant pathways, the extrinsic or receptor-mediated pathway exemplified by FasL–Fas interaction [8] and the intrinsic pathway characterized by mitochondrial involvement as a consequence of cells subjected to physical or chemical stressors [9]. Engagement of the intrinsic pathway has been associated with alterations in protein kinase C (PKC) activity and processing. PKCs are a family of phospholipid-dependent serine/threonine kinases that have significant roles in signal transduction pathways involved in growth, differentiation and cell death. The twelve PKC isoforms identified to date are classified into three groups according to their cofactor requirements. Classical and atypical PKC isoforms are mainly involved in cell proliferation and survival [10], whereas novel PKC isoforms, particularly PKC-δ, often promote cell death [11–15]. PKC-α, a classical PKC isoform, stimulates cell proliferation by activating MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) pathways after its recruitment to the plasma membrane. In vitro studies show that apoptosis is induced in cells where PKC-α levels have been down-regulated by antisense treatment or expression of dominant-negative constructs [16]. In contrast, numerous studies have provided evidence that PKC-δ provides a pro-apoptotic signal and that it can act as a tumour suppressor [17,18]. Apoptotic stimuli seem to activate PKC-δ via caspase proteolysis, generating a 40-kDa catalytically active fragment [15]. Consistent with the above, exposure to DNA-damaging agents in different cell types leads to the occurrence of the PKC-δ 40-kDa fragment in the cytosol, mitochondria and the nucleus, an event that correlates with the onset of apoptosis [14,15,19].

In the present study, we examined the time-dependent effects of a cellular zinc deficiency on classical and novel PKC activity in the cytosolic and particulate fractions of 3T3 cells. The relationship of pro-apoptotic signals or regulators, including activation of caspase-3 and proteolytic cleavage of PKC-δ, to zinc-deficiency-induced cell death was determined. Finally, we investigated whether inhibiting PKC-α, PKC-δ or caspase-3 activity would modulate cell death in zinc-deficient 3T3 cells.

EXPERIMENTAL

Reagents

FBS (fetal bovine serum), penicillin and streptomycin, and DMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium) were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, U.S.A.). Phosphatidylserine (PS) and 1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycerol [DOG; a synthetic DAG (diacylglycerol)] were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, U.S.A.). MARCKS (myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate) peptide was obtained from American Qualex Antibodies (San Clemente, CA, U.S.A.). [γ-32P]ATP, Full Range Rainbow® Molecular Weight Markers and the ECL® (enhanced chemiluminescence) Western blot detection system were purchased from Amersham (Piscataway, NJ, U.S.A.). Catch and Release® Reversible Immunoprecipitation System was obtained from Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions (Lake Placid, NY, U.S.A.). PKC-δ antibody (SC 937 C20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, U.S.A.) was raised against a peptide antigen corresponding to a BLAST specific amino acid sequence (amino acids 655–680) in the C-terminal region of PKC-δ. Anti-PKC-α antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (SC8393 H7) and from Cell Signaling Technologies [anti-phospho-PKC-α (Thr638); Beverly, MA, U.S.A.], and the caspase-3 antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling. Antibodies against HSP 60 were purchased from BD Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY, U.S.A.). Secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase were obtained from Promega (Madison, WI, U.S.A.). Tris/HCl Ready gels and Chelex-100 were purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, U.S.A.); Restore® Western blot stripping buffer was obtained from Pierce (Rockford, IL, U.S.A.). Gö6976 and the caspase-3 inhibitor Z-DQMD-FMK (Z-Asp-Gln-Met-Asp-fluoromethylketone) were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). CyQUANT® cell proliferation assay kit was obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, U.S.A.). ApoAlert® caspase-3 activity assay kit was purchased from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA, U.S.A.). Complete protease inhibitor (EDTA-free) cocktail tablets were obtained from Roche Applied Sciences (Indianapolis, IN, U.S.A.). Microcon®-10 filters were purchased from Millipore (Bedford, MA, U.S.A.). All other reagents were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.).

Preparation of zinc-free buffers and zinc treatment medium

Zinc was removed from buffers by batch washing with 5% (w/v) Chelex-100 for 1 h. The first batch of supernatant wash was discarded and subsequent batches were pooled. Removal of Chelex-100 resin from buffer supernatants was ensured by filtration (0.22-μm pore size). Zinc-deficient medium (0.5 μM zinc) was prepared from DTPA (diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid)-chelated FBS as described previously [5]. Zinc-supplemented medium was prepared from zinc-deficient medium (0.5 μM) by adding ZnSO4 to a final concentration of 50 μM. Control medium was made from FBS not subjected to DTPA chelation. Mineral concentrations in serum and media were analysed by sequential inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES; Trace Scan, Thermo Elemental, Wilmington, MA, U.S.A.). All media in the study contained protein concentrations of 3.0 mg/ml.

Cell culture

3T3-Swiss Albino cells (CCL-92) were obtained from A.T.C.C. (Manassas, VA, U.S.A.) and seeded in control medium at a density of 1.5×106 cells/150-mm diameter dish or 10000 cells/well in 24-well plates. After 24 h, control medium was removed and cells were serum starved in FBS-free DMEM overnight. Subsequently, DMEM was removed and experimental medium was then added and cells were grown for the indicated time periods.

Cell number assay

Cells were washed twice with PBS and plates were frozen at −80 °C. Cell numbers were determined using the CyQUANT® cell proliferation assay kit following manufacturer's procedures (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, U.S.A.) with the exception that uniformly sheared calf thymus DNA was used as the standard.

Zinc analysis

Cells were harvested in buffer containing 20 mM Hepes and 2 mM EDTA, pH 8, and frozen at −80 °C until processed. Cellular zinc content was determined using ICP-AES after acid extraction [20].

Preparation of cell extracts

Cytosolic and particulate fractions were prepared as described previously [21] with slight modification. Cells were washed twice with calcium- and magnesium-free PBS and twice with Buffer A [20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 0.3 M sucrose, 2 mM PMSF, 1×complete protease inhibitor (EDTA-free), 0.5 mM EGTA, 2 mM DTT (dithiothreitol), 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4 and 1 mM NaF]. Cells were then scraped into Buffer A and homogenized in a glass homogenizer (30 strokes). Nuclei were collected by centrifugation at 3300 g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was centrifuged at 100000 g for 1 h at 4 °C to obtain a cytosolic fraction that was stored at −80 °C. The pellet was sonicated (3 times, 10-s bursts) in Buffer B (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 0.5 mM EGTA, 2 mM PMSF, 0.1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4 and 1 mM NaF) and incubated on ice for 30 min. The particulate fraction was then obtained by centrifugation at 100000 g for 1 h at 4 °C and the supernatant was stored at −80 °C.

Mitochondrial fractions were prepared as described [15]. Briefly, cells were homogenized in lysis buffer containing 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 250 mM sucrose, 1 M KCl, 1 M MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 1×complete protease inhibitor (EDTA-free), 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM NaF, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate and 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate. Nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 750 g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 10000 g for 25 min at 4 °C. The mitochondrial fraction was suspended in lysis buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and stored at −80 °C. The supernatant was centrifuged at 100000 g for 1 h and the resulting supernatant was stored at −80 °C.

Nuclear extracts were prepared as described previously [22]. Nuclear pellets were homogenized in a glass homogenizer (6 strokes) in nuclear extraction buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 400 mM KCl, 0.1 mM DTT, 0.2 mM PMSF, 25% glycerol, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4 and 1 mM NaF), incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged at 89000 g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant fraction was then concentrated in Microcon®-10 filters by centrifugation at 12000 g for 2 h at 4 °C. The concentrated extract was diluted in equal volumes of nuclear extraction buffer without KCl and stored at −80 °C.

Protein assay

Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay [23].

PKC activity assay

PKC activity was determined as described previously [24] with modifications. PKC activity was determined in cytosolic and particulate fractions by measuring the rate of phosphorylation of a peptide derived from the MARCKS protein, a PKC substrate. The amount of protein used to measure PKC activity was 20 μg and 10 μg in cytosolic and particulate fractions respectively. Reactions were initiated by adding buffer containing 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 2 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, 100 μM ATP, 1 μCi [γ-32P]ATP, 15 μM MARCKS peptide, 140 μM PS, 3.8 μM DOG and 100 μM CaCl2, and allowed to proceed for 10 min at 30 °C. In addition, background activity was measured by adding 5 mM EGTA and 20 mM Hepes instead of the cofactors CaCl2, PS and DOG. To stop the reaction, buffer containing 0.1 M ATP and 0.1 M EDTA, pH 8, was added. An aliquot of each reaction was spotted on Whatman P81 cellulose filter paper, which was washed four times with 0.4% phosphoric acid and once with 95% ethanol. Radioactivity was measured using a liquid-scintillation counter and PKC activity was calculated as nmol of phosphate transferred/min per mg of protein after subtracting the activity measured in the absence of cofactors.

PKC-α immunoprecipitation

PKC-α was immunoprecipitated from cytosolic extracts incubated with a monoclonal antibody against PKC-α using the Catch and Release® reversible immunoprecipitation system according to manufacturer's specifications (Upstate Inc., Lake Placid, NY, U.S.A.). The resulting immunocomplexes were used to measure kinase activity as described above, in the presence of calcium, PS and DOG. In addition, immunocomplexes were used for Western blot analysis of PKC-α phosphorylation at Thr638.

Inhibition of PKC isoforms

Cells were plated at a density of 10000 cells/well in 24-well plates and grown in control medium for 24 h. Cells were serum-starved in FBS-free DMEM overnight, and the medium replaced with zinc-deficient (0.5 μM zinc) medium. After 8 h in culture, the cells were split into three groups containing: the PKC-α inhibitor Gö6976 (0.01–1 μM), the PCK-δ inhibitor rottlerin (10 μM) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO). The cells were incubated for an additional 24 h (32 h total) in their respective media and harvested.

Inhibition of caspase-3

Cells were plated at a density of 1.5×106 cells/150-mm diameter dish and grown in control medium for 24 h. Cells were serum starved in FBS-free DMEM overnight, and the medium replaced with zinc-deficient (0.5 μM zinc) medium. After 8 h in culture, cells were treated with 25 μM Z-DQMD-FMK or vehicle control (0.1% DMSO) in zinc-deficient medium for 24 h. Cells were then harvested and cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions were collected as described above.

MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide] assay

In the rottlerin experiments, cellular viability was also evaluated using the MTT assay. At the end of the 32 h culture, cells grown in zinc-deficient medium with or without rottlerin (vehicle control, 0.1% DMSO) were incubated with 5 mg/ml MTT in DMEM containing 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, for 1 h at 37 °C. MTT reagent was then removed and cells were frozen at −80 °C. Cells were then lysed with DMSO and absorbance of the MTT formazan was measured at a wavelength of 570 nm. The CyQUANT® assay for cell DNA is incompatible with the MTT assay. Therefore, in order to quantify cell numbers in the MTT experiment, cell number was determined by viewing cells in an Olympus IMT-2 inverted microscope (Melville, NY, U.S.A.) with ×10 phase lens, capturing cell images with a Hamamatsu Orca II charge-coupled-device camera (Bridgewater, NJ, U.S.A.), and processing the images with Isee software (Inovision Corp., Raleigh, NC, U.S.A.). MTT reduction was calculated as the absorbance of MTT formazan normalized to cell number per well.

Western blotting

Equal amounts of protein were heat denatured at 95 °C in Laemmli's buffer for 5 min and subjected to SDS/PAGE and then transferred on to PVDF membranes. Membranes were then blocked in 5% (w/v) skimmed milk in TTBS (0.5 M Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 0.5 M NaCl and 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h and incubated with primary antibodies in 5% (w/v) skimmed milk in TTBS overnight at 4 °C. The antibody–antigen complexes were detected using their respective secondary antibodies in 5% (w/v) skimmed milk in TTBS for 1 h and visualized by chemiluminescence. Membranes were stripped using the Pierce Restore® Western blot stripping buffer, following manufacturer's specifications, and re-blotted for actin. Densitometry analysis was performed using the Quantity One software from Bio-Rad.

Caspase activity assay

Proteolytic activation of caspase-3 was detected using Western blotting analysis to detect the p12 fragment of the 32-kDa zymogen. Caspase-3-like activity was determined by measuring the fluorescence generated by the cleavage of a caspase-3 substrate, DEVD-AFC (Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-7-amino-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin), using the ApoAlert® caspase-3 fluorescent assay kit according to manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were scraped into the cell lysis buffer, incubated on ice for 10 min and centrifuged at 12000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. Protein content was determined for each supernatant and equivalent amounts of protein were measured for caspase-3-like activity in a fluorescence plate reader (400 nm excitation/505 nm emission; Victor 2, PerkinElmer).

Statistics

Experiments were performed at least three times. Data were analysed using ANOVA (Statview 5.0.1). Treatments generating a significant F-value were subjected to post-hoc analysis using the Fisher's least significant difference test. Statistical tests where P≤0.05 were considered significant. Results are expressed as the means±S.E.M.

RESULTS

3T3 cells cultured in zinc-deficient medium have decreased cellular zinc and reduced cell number

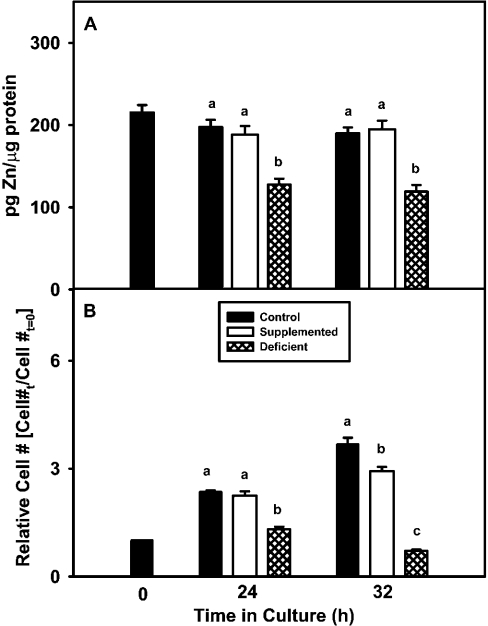

Cells cultured in control and zinc-supplemented media showed similar zinc concentrations at 24 h and 32 h (Figure 1A), whereas cells grown in zinc-deficient medium had significantly lower zinc concentrations at 24 and 32 h (Figure 1A). Similarly, the zinc-deficient group had significantly lower cell numbers than the other groups at 24 h and 32 h (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. 3T3 cells cultured in zinc-deficient medium display decreased cell zinc content and cell number.

(A) 3T3 fibroblasts were cultured in control (untreated FBS), zinc-supplemented (50 μM Zn) or zinc-deficient (0.5 μM Zn) medium for the indicated time periods. Acid-extracted supernatants of 3T3 cells were analysed for total zinc content by ICP-AES. (B) Cell number was determined by DNA analysis and the fold-increase or decrease in cell number relative to initial cells plated (Cell #t=0) is shown. The results are expressed as the means±S.E.M. Data for each time point were subjected to ANOVA and statistical differences (P≤0.05) among treatment groups within a time point are indicated by a difference in lower case letters.

PKC activity of the classical PKC isoforms is decreased in zinc-deficient 3T3 cells

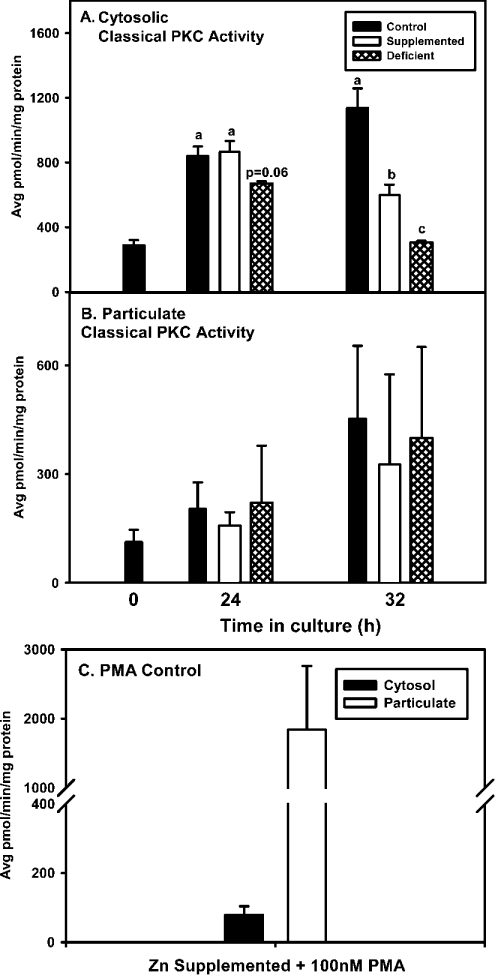

Zinc is found in the regulatory domain of PKC isoforms, where it is thought to influence the activity and translocation of PKC. To test the effects of zinc deficiency on these parameters, activity and compartmentalization of the three major isoform classes of PKC were determined. Cytosolic classical PKC activity measured in the presence of calcium, PS and DOG was lower in zinc-deficient cells than in control or zinc-supplemented cells (Figure 2A). Cytosolic classical PKC activity in zinc-supplemented cells was similar to the control group at 24 h, but lower than the control group at 32 h. Once PKC is activated via cytosolic phosphorylation, it translocates to cellular membranes, where its binding is stabilized by membrane-associated DAG and PS/calcium. Therefore, one explanation for a decrease in cytosolic activity during zinc deficiency could be that classical PKCs translocate to the particulate fraction. However, this outcome was not found to be the case, as activity of the classical PKCs in zinc-deficient cells in the particulate fraction was similar in all groups (Figure 2B). As a positive control, cells from the zinc-supplemented group were exposed to PMA, which induces PKC translocation to the membrane or particulate fraction. PMA treatment significantly induced classical PKC activity in the membrane fraction, while reducing PKC activity in the cytosol (Figure 2C). In contrast to classical PKC activity, activity and compartmentalization of novel PKC isoforms were not affected by zinc deficiency (results not shown).

Figure 2. 3T3 cells cultured in zinc-deficient medium have lower cytosolic PKC activity.

3T3 fibroblasts were cultured in control (untreated FBS), zinc-supplemented (50 μM Zn) or zinc-deficient (0.5 μM Zn) medium for the indicated time periods. Cells were then subjected to ultracentrifugation fractionation and classical PKC activity was measured in cytosolic and particulate fractions under activating (in the presence of calcium, PS and DOG) conditions. (A) Cytosolic classical PKC activity. (B) Particulate classical PKC activity. (C) Translocation of PKC from cytosol to the particulate fraction in cells grown in zinc-supplemented medium (50 μM Zn) for 32 h treated with 100 nM PMA for 30 min prior to harvesting. The results are expressed as the means±S.E.M. Data within each time point were subjected to ANOVA and statistical differences (P≤0.05) among treatment groups within a time point are indicated by a difference in lower case letters.

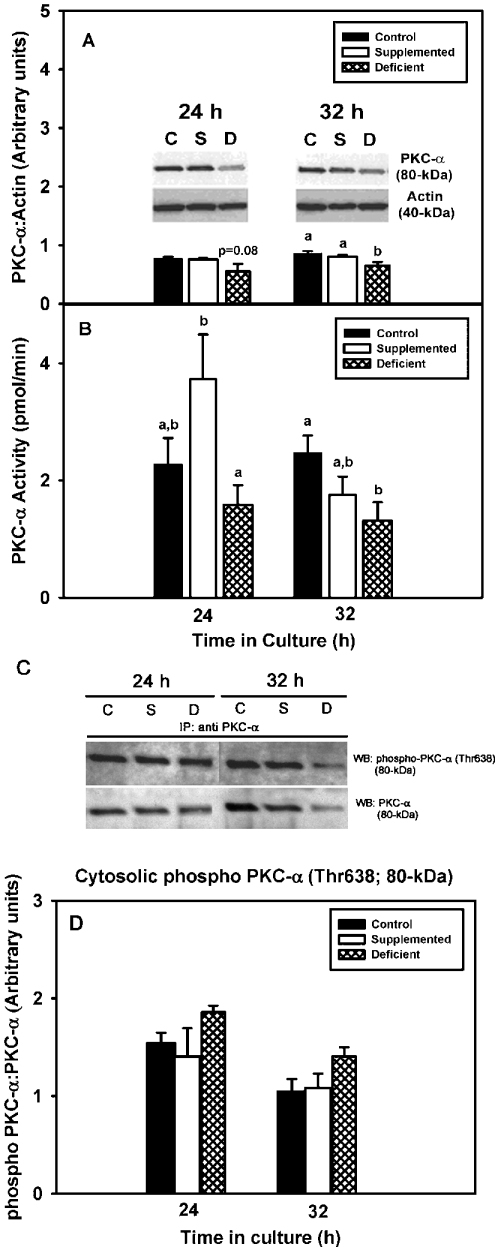

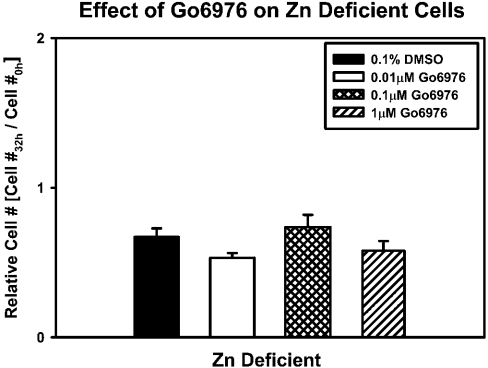

Both cell growth and classical PKC isoforms were affected by zinc depletion. Given that PKC-α is the major classical PKC expressed in 3T3 cells [25] and that increased PKC-α is commonly associated with cellular proliferation and survival, we tested the hypothesis that zinc deficiency would result in decreased PKC-α protein levels, phosphorylation status and activity. PKC-α protein levels tended to be lower in the zinc-deficient group than in control and zinc-supplemented groups at 24 h (P=0.08), and they were significantly lower at 32 h (Figure 3A). Values in the zinc-supplemented and control cells were similar at the two time points. Activity levels of PKC-α in the zinc-deficient group were lower than in the zinc-supplemented and control groups at 24 and 32 h respectively (Figure 3B). Phosphorylation status of PKC-α was investigated as a possible target of zinc deficiency; PKC-α immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis demonstrated that the ratio of phospho-PKC-α (Thr638) to PKC-α was not altered by zinc deficiency (Figures 3C and 3D). Further inhibition of PKC-α activity with increasing doses of Gö6976 (0.01–01 μM), a specific PKC-α inhibitor that induces apoptosis in many cell lines [26], did not result in further alterations in cell number in the zinc-deficient group (Figure 4).

Figure 3. 3T3 cells cultured in zinc-deficient medium have decreased levels of cytosolic PKC-α.

3T3 fibroblasts were cultured in control (untreated FBS), zinc-supplemented (50 μM Zn) or zinc-deficient (0.5 μM Zn) medium for the indicated time periods. (A) Cytosolic fractions were analysed for PKC-α expression levels by SDS/PAGE and Western immunoblot analysis with an anti-PKC-α specific antibody. The Western blots shown are representative of three individual experiments. Densitometry analyses were performed, and the results are expressed as the means±S.E.M. (B) Cytosolic fractions were subjected to immunoprecipitation assays using an anti-PKC-α specific antibody and then assayed for PKC activity in the presence of calcium, PS and DOG. The results are expressed as the means±S.E.M. (C) Cytosolic fractions subjected to immunoprecipitation assays using an anti-PKC-α specific antibody were analysed for phosphorylation at Thr638 by SDS/PAGE and Western immunoblot analysis with an anti-rabbit horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. The membranes were stripped and re-probed for PKC-α using an anti-mouse horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. The Western blots shown are representative of three individual experiments. (D) Densitometry analyses were performed and the results are expressed as the means±S.E.M. Statistical differences (P≤0.05) among treatment groups within a time point are indicated by a difference in lower case letters. C, control, S, zinc-supplemented, D, zinc-deficient.

Figure 4. Addition of Gö6976 does not induce cell death in zinc-deficient cells.

3T3 fibroblasts were cultured in zinc-deficient (0.5 μM Zn) medium. After 8 h in culture, 0.01–1 μM Gö6976 or 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control) was added and cells were allowed to grow for 24 h. Cell number was determined by DNA analysis. The fold-increase/decrease in cell number relative to initial cells plated (Cell #0h) is shown (means±S.E.M.).

Inhibition of PKC-δ in zinc-deficient cells leads to decreased caspase-3 activation and increased cell viability

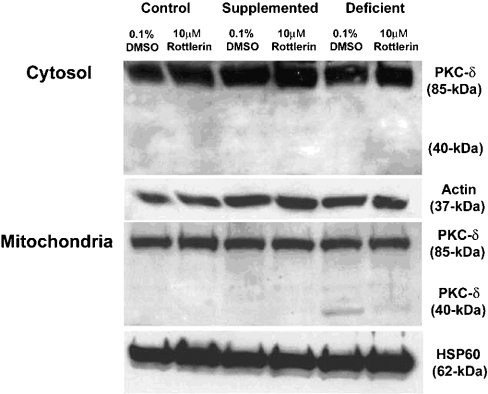

Zinc deficiency results in the activation of effector caspases, such as caspase-3 and caspase-7, which mark the cell for death. Events or agents that trigger mitochondrial stress often activate these effector caspases via cytochrome c release and recruitment/activation of initiator caspases, such as caspase-9. Translocation of full-length PKC-δ and its caspase-3-mediated cleavage to a 40-kDa PKC fragment has been shown to be a positive regulator of apoptosis. To examine the role of PKC-δ in zinc-deficiency-induced apoptosis, cells were cultured in zinc-deficient medium for 8 h and then the medium was replaced with zinc-deficient medium containing 10 μM rottlerin, a PKC-δ inhibitor, or vehicle control (0.1% DMSO). Cells were harvested 24 h later (i.e. 32 h in total in zinc-deficient medium). This time frame was chosen as previous experiments indicated a lack of changes in PKC-δ translocation and cleavage prior to 32 h. At 32 h, zinc-deficient cells treated with vehicle alone (0.1% DMSO) demonstrated significant levels of the 40-kDa cleavage product of PKC-δ in the mitochondrial, but not the cytosolic fraction (Figure 5), whereas the zinc-supplemented and control groups showed only full-length 80-kDa PKC-δ in the cytosol and mitochondria (Figure 5). Rottlerin markedly decreased the levels of the 40-kDa catalytic fragment in zinc-deficient mitochondria by 50% as measured by densitometry (P<0.05; results not shown). Others have shown that the PKC-δ catalytic fragment is present in the nucleus of apoptotic cells where it acts as a lamin kinase to disrupt the nuclear envelope [27]. Although we observed full-length PKC-δ in the nuclear fraction, there was no difference in the expression among groups. There was no evidence of the PKC-δ catalytic fragment in the nuclear fraction of any group (results not shown).

Figure 5. Zinc-deficient cells are characterized by PKC-δ fragmentation, which can be attenuated by rottlerin treatment.

3T3 fibroblasts were cultured in control (untreated FBS), zinc-supplemented (50 μM Zn) or zinc-deficient (0.5 μM Zn) medium. After 8 h in culture, 10 μM rottlerin or 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control) was added to each group of cells and they were allowed to grow for an additional 24 h. Cells were fractionated and cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions were subjected to SDS/PAGE and Western immunoblot analysis for PKC-δ. Densitometry analyses were performed on the zinc-deficient group to quantitate differences in PKC-δ fragmentation. No fragmentation was found in either the control or zinc-supplemented groups. Actin and HSP-60 were used as loading controls for cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions respectively.

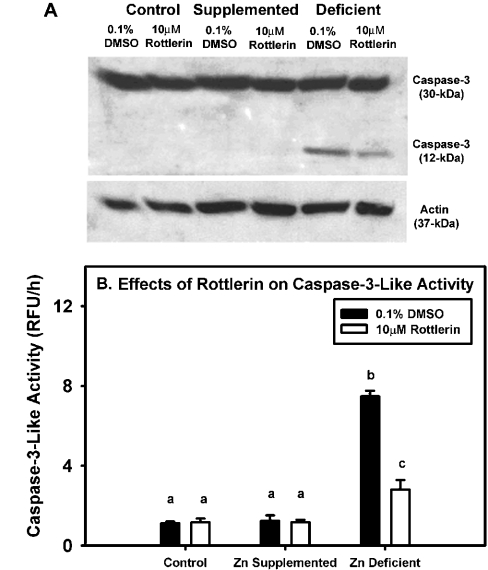

Prior to 32 h, only full-length caspase-3 was noted in the groups (results not shown). However, at 32 h, processing of the full-length caspase-3, as indicated by the occurrence of the p12 fragment, and an increase in caspase-3-like activity, was evident in the zinc-deficient cells (Figures 6A and 6B). Rottlerin treatment of zinc-deficient cells reduced both the processing (measured by densitometry, P<0.05; results not shown) and activation of caspase-3 relative to the vehicle-treated zinc-deficient group (Figure 6A), but caspase-3-like activity was still higher when compared with the zinc-supplemented and control groups (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Zinc-deficient cells display increased caspase-like activity, which is attenuated by rottlerin treatment.

3T3 fibroblasts were cultured in control (untreated FBS), zinc-supplemented (50 μM Zn) or zinc-deficient (0.5 μM Zn) medium. After 8 h in culture, 10 μM rottlerin or 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control) was added to each group of cells and they were allowed to grow for an additional 24 h. (A) Cell lysates were subjected to SDS/PAGE and Western immunoblot analysis for caspase-3 and its cleaved fragments. Densitometry analyses were performed on the activated caspase-3 12-kDa fragment for the zinc-deficient group only, as activated fragments were not present in the control and zinc-supplemented groups. (B) Caspase-3-like activity was measured in all treatment groups in the absence or presence of rottlerin. The results are expressed as means±S.E.M. The different letters indicate significant differences (P≤0.05).

Treatment of zinc-deficient cells with rottlerin resulted in a 75% increase in cell number relative to vehicle (0.1% DMSO)-treated zinc-deficient cells, indicating that PKC-δ catalytic activity contributes to zinc-deficiency-induced cell death. Measurement of cell viability, as assessed by MTT reduction, demonstrated improved cell viability in the zinc-deficient group treated with 10 μM rottlerin compared with the vehicle-treated zinc-deficient group (P<0.05, results not shown).

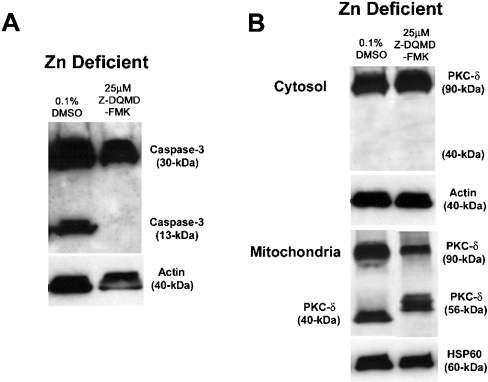

Inhibition of caspase-3 processing in zinc-deficient cells does not prevent cell death but alters processing of PKC-δ

Other studies have demonstrated the existence of a caspase-3–PKC-δ positive feedback loop in cells. Presumably, initial activation of caspase-3 in the cytosol or mitochondria [28] leads to PKC-δ fragmentation and subsequent mitochondrial stress and amplification of the caspase-3 cascade. In the above experiment, we demonstrated that zinc-deficient cells express both the 40-kDa PKC-δ fragment and activated caspase-3. Both of these events can be attenuated with rottlerin treatment of zinc-deficient cells. Next, we asked whether a specific inhibitor of caspase-3, Z-DQMD-FMK, could also attenuate this amplification loop. Our hypothesis was that if caspase-3 activation precedes PKC-δ processing, caspase-3 inhibition would mitigate PKC-δ fragmentation and thus attenuate the caspase-3–PKC-δ feedback loop. 3T3 cells were cultured for 8 h in zinc-deficient medium (i.e. before the onset of caspase-3 activation), the medium was removed, and fresh zinc-deficient medium supplemented with either 25 μM Z-DQMD-FMK or with 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control) was added for an additional 24 h of culture (i.e. 32 h in total). Addition of 25 μM Z-DQMD-FMK to zinc-deficient medium prevented activation of caspase-3 (Figure 7A), whereas addition of the vehicle control (0.1% DMSO) did not affect caspase-3 (Figure 7A). Surprisingly, inhibition of caspase-3 processing led to an alternative processing of PKC-δ into a 56-kDa fragment, whereas treatment of zinc-deficient cells with the vehicle control resulted in the appearance of the 40-kDa PKC fragment as noted above (Figure 7B). Unlike the case for rottlerin, treatment of zinc-deficient cells with 25 μM Z-DQMD-FMK did not restore cell number (results not shown).

Figure 7. Specific caspase-3 inhibitor, Z-DQMD-FMK, does not rescue zinc-deficient cells from cell death.

3T3 fibroblasts were cultured in zinc-deficient (0.5 μM Zn) medium. After 8 h in culture, 25 μM Z-DQMD-FMK or 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control) was added and cells were allowed to grow for 24 h. (A) Cells were fractionated and cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions were subjected to SDS/PAGE and Western immunoblot analysis for PKC-δ. (B) Cytosolic cell extracts were subjected to SDS/PAGE and Western immunoblot analysis for caspase-3 activation. The depicted Western blots are representative of three individual experiments. Actin and HSP60 served as loading controls for cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions respectively.

DISCUSSION

A deficit of zinc can result in decreased cell proliferation and enhanced cell death in animals, and their conceptuses, as well as in in vitro cell culture systems [2,3,5,29,30]. In the present study, medium derived from zinc-deficient FBS was supplemented with zinc or not, allowing us to examine the specific effects of zinc on 3T3 cell PKC activity and processing directly without having the chelator present in the experimental system. Growing cells in zinc-deficient medium resulted in a 35% decline in cellular zinc content. The decline in total zinc in 3T3 cells (measured by ICP-AES) occurring over the 24–32 h time frame is of similar magnitude to the decline in free or labile zinc concentrations {measured indirectly by Zinquin and TSQ [N-6-(6-methoxy-8-quinolyl)-p-toluenesulphonamide] fluorogenic probes} noted in other cell types cultured in zinc-deficient medium [1,2,5]. The reduction in intracellular zinc (whether free or total) is coincident with decreased cell number, a result we have shown to be a consequence of decreased cell proliferation and increased apoptosis [5]. Thus both labile and total intracellular zinc are reasonable predictors of cell fate. Zinc deficiency in vivo and in vitro has been reported to result in apoptosis mediated by caspase activation [3–5,31,32], a finding that is confirmed in the present study. Several studies have implicated caspase-3 in the activation of PKC-δ via proteolytic cleavage to yield a 40-kDa kinase active PKC-δ fragment that is responsible for apoptosis induction [14,15]. Activation of PKC-δ by fragmentation, tyrosine phosphorylation and over-expression of the PKC-δ fragment results in depolarization of mitochondrial membrane potential, nuclear fragmentation and apoptosis in numerous cell types [11,13–15,33,34] (and reviewed in [35]). Furthermore, chemical (rottlerin, GF 109203X), or biological inhibitors (PKC-δ-kinase-dead mutants) of PKC-δ can block the apoptotic action of both chemical and physical stressors [15]. Our results suggest that zinc-deficiency-induced apoptosis is also mediated by PKC-δ fragmentation. However, in the case of zinc-deficiency-induced apoptosis, the PKC-δ fragment seems specifically targeted to the mitochondria, as there is no evidence of PKC-δ fragmentation in the cytosol or nucleus, despite an abundance of full-length PKC-δ in these compartments. Rottlerin treatment significantly reduced the amount of the mitochondrial PKC-δ fragment, and this event was coincident with decreased caspase-3 processing/activity along with increased cell viability (amount of MTT reduced/cell) and cell number. It has been suggested that rottlerin acts indirectly as a mitochondrial uncoupler, resulting in decreased ATP levels and a block in PKC-δ tyrosine activation [36]. Hence, there is the possibility that other ATP-dependent processes, in addition to PKC-δ activation, may contribute to PKC-δ attributed apoptotic processes. However, arguing against this concept are the results by Reyland and co-workers [13,14], demonstrating that kinase-dead mutants of PKC-δ are potent inhibitors of apoptotic agents that mediate their effects through PKC-δ cleavage. Studies examining ATP depletion in cells subjected to apoptotic agents have shown that the mode of cell death switches from apoptosis to predominantly necrosis as the energy charge of the cell decreases. Concordantly, with regard to zinc deficiency, several groups have shown that cell death occurs primarily through apoptosis [5,31,37,38]. Caution concerning the interpretation that PKC-δ cleavage is essential for PKC-δ-induced apoptosis is warranted, given the studies of Soltoff [36], Fujii et al. [39] and Goerke et al. [40] that suggest induction of apoptosis by PKC-δ can be dependent upon PKC-δ tyrosine phosphorylation and independent of its cleavage or kinase activity. Furthermore, in vitro, rottlerin (10 μM) has been demonstrated to inhibit at least one family member of the calmodulin kinases [41].

The fact that the inhibition of PKC-δ fragmentation in the present study resulted in improved cell survival in the zinc-deficient cells, and that it significantly blocked caspase-3 activation/activity, supports the concept that both PKC-δ and zinc can act upstream of broad caspase-3 activation. Indeed, it has been suggested that PKC-δ ‘retro-activation’ of caspase-3 induces further PKC-δ cleavage and amplification of the caspase-3–PKC-δ feedback loop [19]. If caspase-3 is activated upstream of PKC-δ fragmentation, inhibition of caspase-3 should prevent fragmentation of PKC-δ and attenuate the caspase-3–PKC-δ feedback loop. Although inhibition of caspase-3 processing completely blocked the appearance of the 40-kDa PKC-δ fragment, it did not prevent the generation of a mitochondrial specific 56-kDa fragment. This novel finding suggests that at least partial caspase-3 activation lies upstream of the fragmentation of PKC-δ into its 40-kDa form, but that redundant protease(s) are also capable of processing fulllength PKC-δ. The unknown protease(s) responsible for this cleavage is unlikely to be calpain, as we did not observe proteolysis of PKC-α, a known calpain substrate. Furthermore, inhibition of calpain by calpeptin had a minor effect on PKC-δ processing in other cell types [19], whereas calpeptin treatment of salivary acinar cells enhanced PMA-induced apoptosis [42]; albeit, in vitro, calpain treatment of various PKC isoenzymes leads to their cleavage in the hinge region [43]. Others have demonstrated that inhibition of caspases merely switches the mode of cell death from apoptosis to necrosis [44]. Hence, release of lysosomal enzymes (e.g. cathepsins) during the latter form of cell death may be responsible for this alternative processing, although preview of the murine PKC-δ primary structure did not reveal an obvious consensus cathepsin cleavage site. The fact that caspase-3 inhibition did not rescue cells in the zinc-deficient group suggests that the 56-kDa fragment induces cell death in 3T3 cells. Sequencing of the 56-kDa PKC-δ fragment and its eventual expression de novo will yield valuable information concerning whether it is both catalytically active and/or shares the same ‘killing’ power as its established 40-kDa PKC-δ cousin.

We have previously reported that zinc deficiency results in alterations of the cell cycle [5], specifically, a block in the G1–S transition and the appearance of a significant sub-G0–G1 peak indicative of apoptosis. Furthermore, we demonstrated that zinc deficiency in 3T3 cells could result in an elevation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [30]. As studies implicated PKC-α in the regulation of cell cycle and apoptosis [45], combined with reports that intracellular zinc and ROS-induced oxidative stress can regulate PKC-α activity [46], we examined potential effects of zinc deficiency on PKC-α activity and processing.

Signalling cascades regulate both cell proliferation and cell death, and in the case of PKC, distinct family members can play opposing roles in this delicate balance [35]. Classical isoforms, such as PKC-α, have been demonstrated to promote cell proliferation and inhibit apoptosis. The former event seems to be mediated by up-regulation of cyclin D1 and down regulation of p21WAF1/CIP1 [45], whereas the latter event is partially regulated by activation of Raf-1 [47,48] and phosphorylation of Bcl-2 [49]. Classical PKC signalling is mediated by translocation in its mature form from the cytosol to the membrane or particulate fraction of the cell as a consequence of receptor-mediated signaling. This event occurs as membranes contain inducible amounts of highly localized DAG and calcium/PS that interact with the C1 (i.e. DAG-binding site) and C2 (calcium-binding site) domains of classical forms of PKC. This stabilization process induces release of the active site pseudo-substrate, allowing for subsequent PKC-α phosphorylation of downfield targets. Our initial screen of zinc-deficient cells for classical PKC activity revealed no steady-state differences among the groups in the particulate fraction. These results would suggest that under steady-state conditions in vivo cellular zinc levels (free or total), or the oxidative stress associated with zinc deficiency, do not directly influence the compartmentalization or activities of PKC family members. However, despite the lack of differences in classical PKC activities in the particulate fraction, we noted a decline in cytosolic activities of classical forms. Subsequent immunoprecipitation/in vitro kinase assays verified that the most abundant classical PKC isoform in 3T3 cells, PKC-α, was similarly lower in the cytosol of zinc-deficient cells. Further examination revealed decreased protein levels of cytosolic PKC-α that can account for some of the decline in PKC-α activity. Decreased activity of PKC-α could also be a function of its phosphorylation status. The initial phosphorylation of PKC-α occurs in its activation loop, which is carried out by phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 [50]. Subsequent autophosphorylations at the turn and hydrophobic motif result in mature enzyme that is released into the cytosol where it remains inactive until DAG and calcium fluxes recruit the enzyme to the membrane or to other cellular compartments by adapter proteins, termed RACKS (receptors for activated C-kinase) [51]. In this study, phosphorylation status (Thr638) of cytoplasmic PKC-α seemed to be unaffected by treatment, as the ratio of phospho-PKC-α to PKC-α did not differ among groups. In other studies, antisense or dominant-negative constructs were used to knock-down levels and activities of PKC-α, which resulted in cell cycle alterations and appeared to make cells more permissive to apoptosis [13,45]. Matassa et al. [13] provided evidence for a direct link between declining PKC-α levels and initiation of a PKC-δ-directed apoptotic programme. In the knock-down studies described above, the levels of PKC-α were more markedly reduced than that achieved alone by zinc deficiency in the present study. However, the inhibitor Gö6976, at concentrations known to inhibit PKC-α activity and induce apoptosis in cells [26], did not further enhance zinc-deficiency-induced apoptosis. This outcome suggests that even slightly reduced levels of PKC-α activity achieved by zinc deficiency alone may be sufficient to sensitize cells to apoptosis.

The mechanism(s) underlying the decline in cytosolic PKC-α protein levels have yet to be identified. Transcriptional regulation of the murine and human PKC-α promoters seems to occur primarily through consensus sequences characteristic of RAREs (retinoic-acid-response elements), AP-2 (activator-2), Sp1 and GATA-1 [52]. Examination of the PKC-α promoter revealed no inducible MREs (metal response elements), however, GATA-1, the ubiquitous constitutive transcription factor Sp1, and retinoid receptors are all dependent upon zinc for their DNA-binding activity. Thus alterations in zinc-dependent transcription factor binding and transactivation cannot be ruled out as a possible explanation for the decreased PKC-α levels noted in the cytosol of zinc-deficient cells.

As an alternative explanation, increased proteolysis may be responsible for the decreased cytosolic PKC-α expression, although the mechanism of proteolysis cannot be explained by direct fragmentation [53], as there were no indications of PKC-α cleavage revealed by SDS/PAGE and Western analysis. However, PKC-α is normally degraded via the proteosome pathway. Thus down-regulation of PKC-α during prolonged exposure to phorbol esters occurs through dephosphorylation, followed by ubiquitination, thereby targeting the protein for degradation [54]. Supporting the concept that enhanced proteosome activity may be a feature of zinc deficiency is the observation that zinc-deficient IMR-32 cells have enhanced proteosome-mediated turnover of IκBα, an inhibitory protein that sequesters NF-κB (nuclear factor-κB) in the cytoplasm [2]. Further studies are warranted to delineate the mechanism for zinc-deficiency-induced reduction in PKC-α levels.

In summary, we have demonstrated that zinc deficiency alters cell signalling pathways through possible down-regulation of PKC-α and activation of the pro-apoptotic protein PKC-δ, leading to decreased cell proliferation and accelerated cell death. We have identified PKC-δ as a key target of zinc-deficiency-induced apoptosis, whose catalytic domain localizes exclusively to the mitochondria. In this vein, we had demonstrated previously [5] that decreases in the labile zinc pool temporally preceded alterations in the mitochondrial electrochemical potential (ΔΨm) and caspase activation. Loss of ΔΨm is associated with the onset of the mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) and the subsequent release of pro-apoptotic molecules, such as cytochrome c and AIF (apoptosis-inducing factor), from the inner mitochondrial membrane space into the cytoplasm [55], which leads to an irreversible commitment to cell death. Blocking PKC-δ activation and mitochondrial translocation leads to a significant reduction in caspase-3 activation and results in significant rescue of zinc-deficient cells.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HD-01743, T32-DK 07355 and DK 35747). We would like to acknowledge Joel Commisso for the trace element analysis and Dr Janet Uriu-Adams, Jodi Ensunsa, Valentin Chou and Jason Clegg for their valuable input concerning technical aspects of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Mackenzie G. G., Keen C. L., Oteiza P. I. Zinc status of human IMR-32 neuroblastoma cells influences their susceptibility to iron-induced oxidative stress. Dev. Neurosci. 2002;24:125–133. doi: 10.1159/000065691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackenzie G. G., Zago M. P., Keen C. L., Oteiza P. I. Low intracellular zinc impairs the translocation of activated NF-kappa B to the nuclei in human neuroblastoma IMR-32 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:34610–34617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203616200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jankowski-Hennig M. A., Clegg M. S., Daston G. P., Rogers J. M., Keen C. L. Zinc-deficient rat embryos have increased caspase 3-like activity and apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;271:250–256. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Truong-Tran A. Q., Grosser D., Ruffin R. E., Murgia C., Zalewski P. D. Apoptosis in the normal and inflamed airway epithelium: role of zinc in epithelial protection and procaspase-3 regulation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003;66:1459–1468. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00498-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duffy J. Y., Miller C. M., Rutschilling G. L., Ridder G. M., Clegg M. S., Keen C. L., Daston G. P. A decrease in intracellular zinc level precedes the detection of early indicators of apoptosis in HL-60 cells. Apoptosis. 2001;6:161–172. doi: 10.1023/a:1011380508902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Truong-Tran A. Q., Carter J., Ruffin R. E., Zalewski P. D. The role of zinc in caspase activation and apoptotic cell death. Biometals. 2001;14:315–330. doi: 10.1023/a:1012993017026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolf C. M., Eastman A. The temporal relationship between protein phosphatase, mitochondrial cytochrome c release, and caspase activation in apoptosis. Exp. Cell Res. 1999;247:505–513. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagata S. Fas ligand-induced apoptosis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1999;33:29–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penninger J. M., Kroemer G. Mitochondria, AIF and caspases-rivaling for cell death execution. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:97–99. doi: 10.1038/ncb0203-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soh J. W., Weinstein I. B. Roles of specific isoforms of protein kinase C in the transcriptional control of cyclin D1 and related genes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:34709–34716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blass M., Kronfeld I., Kazimirsky G., Blumberg P. M., Brodie C. Tyrosine phosphorylation of protein kinase Cδ is essential for its apoptotic effect in response to etoposide. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:182–195. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.1.182-195.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brodie C., Blumberg P. M. Regulation of cell apoptosis by protein kinase Cδ. Apoptosis. 2003;8:19–27. doi: 10.1023/a:1021640817208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matassa A. A., Kalkofen R. L., Carpenter L., Biden T. J., Reyland M. E. Inhibition of PKCα induces a PKCδ-dependent apoptotic program in salivary epithelial cells. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:269–277. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeVries T. A., Neville M. C., Reyland M. E. Nuclear import of PKCδ is required for apoptosis: identification of a novel nuclear import sequence. EMBO J. 2002;21:6050–6060. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denning M. F., Wang Y., Tibudan S., Alkan S., Nickoloff B. J., Qin J. Z. Caspase activation and disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential during UV radiation-induced apoptosis of human keratinocytes requires activation of protein kinase C. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:40–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsieh Y. C., Jao H. C., Yang R. C., Hsu H. K., Hsu C. Suppression of protein kinase Cα triggers apoptosis through down-regulation of Bcl-xL in a rat hepatic epithelial cell line. Shock. 2003;19:582–587. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000065705.84144.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reyland M. E., Anderson S. M., Matassa A. A., Barzen K. A., Quissell D. O. Protein kinase Cδ is essential for etoposide-induced apoptosis in salivary gland acinar cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:19115–19123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abbas T., White D., Hui L., Yoshida K., Foster D. A., Bargonetti J. Inhibition of human p53 basal transcription by down-regulation of protein kinase Cδ. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:9970–9977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306979200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leverrier S., Vallentin A., Joubert D. Positive feedback of protein kinase C proteolytic activation during apoptosis. Biochem. J. 2002;368:905–913. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clegg M. S., Keen C. L., Lonnerdal B., Hurley L. S. Influence of ashing techniques in the analysis of trace elements in animal tissue. I. Wet ashing. Biol. Trace Element Res. 1981;3:107–115. doi: 10.1007/BF02990451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu J. Y., Lin S. J., Lin J. K. Inhibitory effects of curcumin on protein kinase C activity induced by 12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate in NIH 3T3 cells. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14:857–861. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dalton T. P., Li Q., Bittel D., Liang L., Andrews G. K. Oxidative stress activates metal-responsive transcription factor-1 binding activity. Occupancy in vivo of metal response elements in the metallothionein-I gene promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:26233–26241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.26233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newton A. C. Analyzing protein kinase C activation. Methods Enzymol. 2002;345:499–506. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)45041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mischak H., Goodnight J. A., Kolch W., Martiny-Baron G., Schaechtle C., Kazanietz M. G., Blumberg P. M., Pierce J. H., Mushinski J. F. Overexpression of protein kinase C-δ and -ε in NIH 3T3 cells induces opposite effects on growth, morphology, anchorage dependence, and tumorigenicity. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:6090–6096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amin H. M., Ergin M., Denning M. F., Quevedo M. E., Alkan S. Characterization of apoptosis induced by protein kinase C inhibitors and its modulation by the caspase pathway in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2000;110:552–562. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cross T., Griffiths G., Deacon E., Sallis R., Gough M., Watters D., Lord J. M. PKC-δ is an apoptotic lamin kinase. Oncogene. 2000;19:2331–2337. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samali A., Cai J., Zhivotovsky B., Jones D. P., Orrenius S. Presence of a pre-apoptotic complex of pro-caspase-3, Hsp60 and Hsp10 in the mitochondrial fraction of Jurkat cells. EMBO J. 1999;18:2040–2048. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clegg M. S., Keen C. L., Donovan S. M. Zinc deficiency-induced anorexia influences the distribution of serum insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins in the rat. Metabolism. 1995;44:1495–1501. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(95)90152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oteiza P. I., Clegg M. S., Zago M. P., Keen C. L. Zinc deficiency induces oxidative stress and AP-1 activation in 3T3 cells. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2000;28:1091–1099. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolenko V. M., Uzzo R. G., Dulin N., Hauzman E., Bukowski R., Finke J. H. Mechanism of apoptosis induced by zinc deficiency in peripheral blood T lymphocytes. Apoptosis. 2001;6:419–429. doi: 10.1023/a:1012497926537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanna L. A., Clegg M. S., Momma T. Y., Daston G. P., Rogers J. M., Keen C. L. Zinc influences the in vitro development of peri-implantation mouse embryos. Birth Defects Res. Part A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2003;67:414–420. doi: 10.1002/bdra.10046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Basu A., Woolard M. D., Johnson C. L. Involvement of protein kinase C-δ in DNA damage-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8:899–908. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshida K., Wang H. G., Miki Y., Kufe D. Protein kinase Cδ is responsible for constitutive and DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of Rad9. EMBO J. 2003;22:1431–1441. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gutcher I., Webb P. R., Anderson N. G. The isoform-specific regulation of apoptosis by protein kinase C. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2003;60:1061–1070. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-2281-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soltoff S. P. Rottlerin is a mitochondrial uncoupler that decreases cellular ATP levels and indirectly blocks protein kinase Cdelta tyrosine phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:37986–37992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105073200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zalewski P. D., Forbes I. J., Seamark R. F., Borlinghaus R., Betts W. H., Lincoln S. F., Ward A. D. Flux of intracellular labile zinc during apoptosis (gene-directed cell death) revealed by a specific chemical probe, zinquin. Chem. Biol. 1994;1:153–161. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chimienti F., Seve M., Richard S., Mathieu J., Favier A. Role of cellular zinc in programmed cell death: temporal relationship between zinc depletion, activation of caspases, and cleavage of Sp family transcription factors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001;62:51–62. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00624-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujii T., García-Bermejo M. L., Bernabó J. L., Caamaño J., Ohba M., Kuroki T., Li L., Yuspa S. H., Kazanietz M. G. Involvement of protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ) in phorbol ester-induced apoptosis in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Lack of proteolytic cleavage of PKCδ. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:7574–7582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goerke A., Sakai N., Gutjahr E., Schlapkohl W. A., Mushinski J. F., Haller H., Kolch W., Saito N., Mischak H. Induction of apoptosis by protein kinase Cδ is independent of its kinase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:32054–32062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203734200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gschwendt M., Muller H. J., Kielbassa K., Zang R., Kittstein W., Rincke G., Marks F. Rottlerin, a novel protein kinase inhibitor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994;199:93–98. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reyland M. E., Barzen K. A., Anderson S. M., Quissell D. O., Matassa A. A. Activation of PKC is sufficient to induce an apoptotic program in salivary gland acinar cells. Cell Death Differ. 2000;7:1200–1209. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kishimoto A., Mikawa K., Hashimoto K., Yasuda I., Tanaka S., Tominaga M., Kuroda T., Nishizuka Y. Limited proteolysis of protein kinase C subspecies by calcium-dependent neutral protease (calpain) J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:4088–4092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lemaire C., Andréau K., Souvannavong V., Adam A. Inhibition of caspase activity induces a switch from apoptosis to necrosis. FEBS Lett. 1998;425:266–270. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deeds L., Teodorescu S., Chu M., Yu Q., Chen C. Y. A p53-independent G1 cell cycle checkpoint induced by the suppression of protein kinase Cα and θ isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:39782–39793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Korichneva I., Hoyos B., Chua R., Levi E., Hammerling U. Zinc release from protein kinase C as the common event during activation by lipid second messenger or reactive oxygen. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:44327–44331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205634200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buitrago C. G., Pardo V. G., de Boland A. R., Boland R. Activation of RAF-1 through Ras and protein kinase Cα mediates 1α,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 regulation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:2199–2205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205732200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bronisz A., Gajkowska B., Domanska-Janik K. PKC and Raf-1 inhibition-related apoptotic signalling in N2a cells. J. Neurochem. 2002;81:1176–1184. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jiffar T., Kurinna S., Suck G., Carlson-Bremer D., Ricciardi M. R., Konopleva M., Andreeff M., Ruvolo P. P. PKCα mediates chemoresistance in acute lymphoblastic leukemia through effects on Bcl2 phosphorylation. Leukemia. 2004;18:505–512. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Newton A. C. Regulation of the ABC kinases by phosphorylation: protein kinase C as a paradigm. Biochem. J. 2003;370:361–371. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McCahill A., Warwicker J., Bolger G. B., Houslay M. D., Yarwood S. J. The RACK1 scaffold protein: a dynamic cog in cell response mechanisms. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002;62:1261–1273. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.6.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clark J. H., Haridasse V., Glazer R. I. Modulation of the human protein kinase Cα gene promoter by activator protein-2. Biochemistry. 2002;41:11847–11856. doi: 10.1021/bi025600k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamakawa H., Banno Y., Nakashima S., Yoshimura S., Sawada M., Nishimura Y., Nozawa Y., Sakai N. Crucial role of calpain in hypoxic PC12 cell death: calpain, but not caspases, mediates degradation of cytoskeletal proteins and protein kinase C-α and -δ. Neurol. Res. 2001;23:522–530. doi: 10.1179/016164101101198776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu Z., Liu D., Hornia A., Devonish W., Pagano M., Foster D. A. Activation of protein kinase C triggers its ubiquitination and degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:839–845. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ravagnan L., Roumier T., Kroemer G. Mitochondria, the killer organelles and their weapons. J. Cell. Physiol. 2002;192:131–137. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]