Abstract

Cationic lipodepsipeptides from Pseudomonas spp. have been characterized for their structural and antimicrobial properties. In the present study, the structure of a novel lipodepsipeptide, cormycin A, produced in culture by the tomato pathogen Pseudomonas corrugata was elucidated by combined protein chemistry, mass spectrometry and two-dimensional NMR procedures. Its peptide moiety corresponds to L-Ser-D-Orn-L-Asn-D-Hse-L-His-L-aThr-Z-Dhb-L-Asp(3-OH)-L-Thr(4-Cl) [where Orn represents ornithine, Hse is homoserine, aThr is allo-threonine, Z-Dhb is 2,3-dehydro-2-aminobutanoic acid, Asp(3-OH) is 3-hydroxyaspartic acid and Thr(4-Cl) is 4-chlorothreonine], with the terminal carboxy group closing a macrocyclic ring with the hydroxy group of the N-terminal serine residue. This is, in turn, N-acylated by 3,4-dihydroxy-esadecanoate. In aqueous solution, cormycin A showed a rather compact structure, being derived from an inward orientation of some amino acid side chains and from the ‘hairpin-bent’ conformation of the lipid, due to inter-residue interactions involving its terminal part. Cormycin was significantly more active than the other lipodepsipeptides from Pseudomonas spp., as demonstrated by phytotoxicity and antibiosis assays, as well as by red-blood-cell lysis. Differences in biological activity were putatively ascribed to its weak positive net charge at neutral pH. Planar lipid membrane experiments showed step-like current transitions, suggesting that cormycin is able to form pores. This ability was strongly influenced by the phospholipid composition of the membrane and, in particular, by the presence of sterols. All of these findings suggest that cormycin derivatives could find promising applications, either as antifungal compounds for topical use or as post-harvest biocontrol agents.

Keywords: antimicrobial peptide, cormycin, lipid bilayer, lipodepsipeptide, membrane permeabilization, phytotoxin, Pseudomonas corrugata

Abbreviations: CM-A, cormycin A; HMQC, heteronuclear multiple quantum correlation; LDP, lipodepsipeptide; LUVs, large unilamellar vesicles; MALDI–TOF, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight; NOE, nuclear Overhauser effect; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PSD, post-source decay; RBC, red-blood cell; C50, peptide concentration causing 50% RBC lysis; PS, pseudomycin; SM, sphingomyelin; SR, syringomycin; SS, syringostatin; ST, syringotoxin; TPPI, time proportional phase increment

INTRODUCTION

Human and plant pathogens are increasingly resistant to current control strategies. Much effort has been spent in finding novel compounds with antimicrobial properties. Among these molecules, different polypeptides from various organisms have been studied for their important pharmaceutical and agricultural applications. LDPs (lipodepsipeptides) from Pseudomonas spp. are among the most characterized bacterial peptide derivatives [1]; in particular, those from the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae van Hall have been studied either as antifungal derivatives for pharmacological use or as post-harvest biocontrol agents [2–4]. P. corrugata Robert et Scarlett is a Gram-negative bacterium that has been isolated all over the world from bulk soil and the plant rhizosphere, as well as from several plant species. It is the causal agent of some necrotic diseases of cultivated plants, such as pith necrosis of tomato and pepper [5]; infected plants may wilt and die. The type of damage caused to plants, particularly loss of turgor of parenchymatic tissues, cell collapsing and necrosis, suggests that toxins produced by the pathogen are partially responsible for disease symptoms. P. corrugata is also a strong antagonist of several bacteria [6].

Several species of plant pathogenic Pseudomonas, particularly P. syringae, produce, in culture, phytotoxic and antimicrobial cationic LDPs belonging to two main groups. The first one is formed by nonapeptide lactones acylated by a long chain of 3-hydroxy fatty acids. This group includes the SRs (syringomycins) [7,8], the STs (syringotoxins) [9], the SSs (syringostatins) [10] and the PSs (pseudomycins) [11]. The second group consists of lipopeptides formed by a long and highly hydrophobic peptide chain, containing a polar lactonized penta- or octa-peptide moiety at the C-terminus. It includes the tolaasins [12], the SPs (syringopeptins) [13] and the FPs (fuscopeptins) [14]. Both classes present a cyclic structure rich in basic amino acids that resembles the characteristic disulphide-bridged hepta-, octa- and nona-peptide ring occurring in a series of antimicrobial peptides recently described from amphibian skin [15]. The strong activity of these Pseudomonas metabolites against plants, animals and microorganisms is due to their membrane-disrupting ability, as demonstrated by their effect on some membrane functions in higher plants [16]. In fact, biophysical studies have demonstrated that LDPs form transmembrane ion channels, and consequently increase cell membrane permeability [17–21].

Recently, it was demonstrated that a P. corrugata strain from tomato (NCPPB 2445) produces two isoforms of LDPs consisting of 22 amino acid residues; these long-chain lipodepsipeptides were called corpeptins (CPA and CPB; [22]). Interestingly, no nonapeptides were found in the culture filtrate of this strain. This finding was very unexpected, because Pseudomonas strains usually produce both groups of LDPs. To verify the possibility that nonapeptides could also be present in the P. corrugata filtrates, culture media of several wild-type bacterium strains were produced and screened. Their chromatographic analysis revealed a strain-dependent production of nonapeptides; this finding prompted us to characterize these novel compounds. In the present study, we describe the isolation, structural elucidation, definition of structure in solution, and biological activity of a member of this family of lipodepsinonapeptides.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Ergosterol, stigmasterol, soya-bean asolectin (a negatively charged mixture of 24% PC (phosphatidylcholine), 39% phosphatidylethanolamine, 19% phosphatidylserine, 6% phosphatidic acid, 1% phosphatidylinositol and 11% other lipids), calcein, Sephadex G50 and α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid were from Sigma (St Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Prionex (porcine hydrolysed collagen with an average mass of 20 kDa) was from Pentapharm (Basel, Switzerland). Egg PC, egg SM (sphingomyelin), cholesterol, egg phosphatidic acid, 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycerophosphocholine and liver phosphatidylinositol were from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, U.S.A.); all lipids were used without further purifications. Triton X-100 was from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). 2H2O, H2O and CF3C2H2O2H (deuterated trifluoroethanol) for NMR experiments were purchased from Fluka and ICN Biochemicals respectively.

Bacterial strain and culture conditions

P. corrugata strain IPVCT 10.3, isolated from tomatoes in Italy and belonging to the genomic group I [23], was used throughout the present study. Colonies were maintained on nutrient agar containing 2% (v/v) glycerol, and stored at 4 °C.

For toxin production, bacteria were grown in 1-litre Roux bottles containing 200 ml of 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 6.2, 1% (w/v) mannitol, 0.4% (w/v) L-α-amino-β-imidazole-propionic acid, 0.01% (w/v) CaCl2, 0.02% (w/v) MgSO4 and 0.002% (w/v) FeSO4 [24]. Bacterial inoculum was prepared from cultures grown on King B medium at 25 °C for 24 h. Bacteria were washed from medium with sterile distilled water, and the resulting suspension was adjusted to an optical density of 0.3 [2×108 c.f.u. (colony-forming units)/ml], estimated spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 600 nm. Each bottle was inoculated with 400 μl of bacterial suspension and incubated in the dark at 25 °C for 5 days.

Peptide extraction and purification procedure

After incubation, cultures were acidified at pH 2 by 1 M HCl addition; then, an equal volume of cold acetone was added and the precipitate was stored overnight at 4 °C. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (7000 g for 15 min at 4 °C). Toxin extraction and purification were carried out as described previously [8]. Extracts were fractionated by reversed-phase HPLC on a Aquapore RP300 column (220 mm×4.6 mm, 7 μm internal diameter; Applied Biosystems, Framingham, MA, U.S.A.) using a model 200LC pump (PerkinElmer, Fremont, CA, U.S.A.) and a model SP-10AVvp UV-VIS detector (Shimadzu, Japan). Single peaks were collected manually, and the freeze-dried material was used for further characterization.

Chemical procedures

Lactone bond hydrolysis was selectively obtained following incubation with 0.1 M NH4HCO3 at 37 °C overnight. Partial acid hydrolysis was performed in 120 mM HCl for 30, 180 and 480 min at 110 °C. Mass spectrometry (MS) analysis of peptide partial hydrolysates was performed directly on hydrolysis product mixtures without any purification procedure. Extensive peptide hydrolysis was obtained following incubation with 6 M HCl at 110 °C for 24 h in vacuo. Amino acid analyses were performed with a 4151 Alpha Plus automatic analyser (Amersham Biosciences). Amino acid chirality was determined on CM-A (cormycin A) hydrolysates following derivative formation with 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrophenyl-5-L-alanine amide and chromatographic separation of the resulting derivatives, as described previously [25]. Parallel analysis of SR-E and ST was performed as a control.

MS

LDPs were identified by LC-MS using an API-100 single quadrupole mass spectrometer (PerkinElmer Sciex Instruments, Montreal, PQ, Canada) equipped with an atmospheric pressure ionization source. Separation was performed using an Aquapore RP300 column (220 mm×2.1 mm, 7 μm internal diameter; Applied Biosystems) eluted at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min. The eluate was monitored at 220 nm and 0.05 ml/min split into the ion source, measuring the total ion current. A probe voltage of 4.7 kV and a declustering potential of 40 V were used. Acquisition was made in positive polarity, using a dwell time of 1 ms and a step size of 0.5 m/z. Each scan was acquired from 500–2500 m/z. The instrument was calibrated with the ions of ammonium adducts of poly(propylene glycol). LC-MS data were processed with BioMultiView software (PerkinElmer Sciex).

Samples were also analysed by MALDI–TOF (matrix-assisted laser-desorption ionization–time of flight) MS using a Voyager-DE PRO mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems). Peptides were loaded on to the instrument target using the dried droplet technique and α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid as matrix. Spectra were acquired either by reflectron or linear mode with delayed extraction. PSD (post-source decay) fragment ion spectra were acquired after isolation of the appropriate precursor using timed ion selection. Fragment ions were refocused on to the detector by stepping the voltage applied to the reflectron in the following ratios: 1.000 (precursor ion segment), 0.960, 0.750, 0.563, 0.422, 0.316, 0.237, 0.178, 0.133, 0.100, 0.075, 0.056 and 0.042 (fragment segments). Individual segments were superimposed by using the Data Explorer 5.1 software (Applied Biosystems). All precursor ion segments were acquired at low laser power (variable attenuator=1950) for less than 200 laser pulses to avoid saturation of the detector. The laser power was increased by 200 units for all remaining segments of the PSD acquisitions. Typically, 300 laser pulses were acquired for each fragment-ion segment. The PSD data were acquired with an Acquiris digitizer at a digitization rate of 500 MHz.

NMR experiments

Samples for NMR study were prepared by dissolving approx. 1 mg of freeze-dried peptide both in 700 μl of 2H2O (for preliminary observations) and in CF3C2H2O2H/H2O (4:1 v/v), without any pH correction. NMR spectra were run on a Bruker AMX600 instrument operating at 600.13 MHz with a z-gradient selection. Experiments were performed either at 300 K or at lower temperatures; in fact, at 282 K it was possible to obtain spectra with a good resolution, avoiding both precipitation processes and concentration effects due to peptide aggregation.

1H-NMR experiments were performed using either a suitable pre-saturation of the water signal or a gradient water suppression sequence. 1H–1H TOCSY and NOESY experiments were performed in the phase-sensitive mode with the TPPI (time proportional phase increment) method using a gradient water suppression. The HMQC (heteronuclear multiple quantum correlation) experiment was performed using the echo/anti-echo detection method with a soft pre-saturation to suppress the water signal. All the two-dimensional experiments have been acquired with a time domain of 1024 data points in the F2 dimension, 512 data points in the F1 dimension and a recycle delay of 1 s. 1H–1H TOCSY was acquired with a spin-lock duration of 80 ms; 1H–1H NOESY was acquired with a mixing time of 200 ms; the HMQC was acquired using a coupling constant 1JC-H of 150 Hz. The number of scans was optimized to obtain a satisfactory signal/noise ratio.

Structural determination, refinement and analysis from NMR data

NMR data from NOESY spectra performed on the sample in CF3C2H2O2H/H2O (4:1, v/v) at 282 K were translated into interprotonic distance restraints by classifying peak intensities into three classes: ‘strong’ (s), ‘medium’ (m) and ‘weak’ (w), corresponding to 3.0, 4.0 and 5.0 Å distance upper-limit values respectively (1 Å≡0.1 nm). Pseudoatoms were used to represent non-stereospecifically assigned protons.

Restraints were processed with CYANA 1.0.6 [26], setting both ‘swap’ and ‘expand’ parameters equal to zero to reproduce the behaviour of DYANA 1.5 [26], by applying pseudoatom correction and the GRIDSEARCH module (excluding the ‘distance modify’ option to prevent excessive increase of restraint distance values involving pseudoatoms). These restraints were used in SA (simulated annealing) calculations with CYANA 1.0.6, using default values for all program variables not explicitly discussed here.

Restraints (143 in total) were initially classified as either ‘unambiguous’ (a single possible assignment allowed, no noise or solvent interference) or ‘ambiguous’ (28 restraints; multiple possible assignments and/or location in noisy regions, close proximity to solvent signals).

Starting with ‘unambiguous’ restraints only, an iterative structure determination was performed based on 200 cycles of simulated annealing, which produced a structure set in which the best 20 conformations in terms of target function were used for a tentative assignment of the remaining ambiguous restraints. The new assignments were retained only if the resulting structures exhibited better convergence and target function values than the previous set. The whole cycle was iterated until no new assignments or target function improvements were obtained. The resulting best 20 structures of the last iteration underwent final refinement and analyses.

These structures were energy-minimized, using the SANDER module of the AMBER 6.0 package [27], down to an energy gradient norm value of <10−4 kcal·mol−1·Å−1 (1 cal≈4.184 J). The PARM99 set of force-field parameters [28,29], with a distance-dependent dielectric constant ε=rij and an 8 Å cut-off for non-bonded distances, were used. Atomic point charges of non-codified residues for the AMBER force-field were calculated using a standard procedure, based on the best fit of ab initio electronic distribution {Hartree-Fock level, 6-31G* basis set, GAMESS (General Atomic and Molecular Electronic Structure System) program [30] with the RESP (restrained electrostatic potential) procedure [31,32]}. Parameters for the other force-field terms were derived by analogy with already parameterized residues and atom types, except for torsional parameters involving Φ and ψ dihedral angles of Z-Dhb (2,3-dehydro-2-aminobutanoic acid), obtained by minimizing the difference between ab initio and AMBER (Φ,ψ) potential energy hypersurfaces (P. Amodeo, unpublished work).

Final analyses and figure drawing were performed with the MolMol 2K.2 program [33].

Antimicrobial and phytotoxic assays

Antimicrobial activity of culture filtrates and preparations from each purification step was tested against cultures of Bacillus megaterium de Bary ITM 100 and Rhodotorula pilimanae Hedrick et Burke A.T.C.C. 26423 by PDA plate assay [34]. Activity of preparations and pure compounds was expressed in LDP unit/μg. In particular, a unit of activity was the amount of toxin in a 10 μl droplet which completely inhibited growth of B. megaterium in the area of application of the droplet. Phytotoxic activity was estimated by injection on leaves of 1-month-old tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum, L. cv). White Burley plants were grown in a greenhouse at 23 °C [35]. Appearance of necrotic lesions was observed at 48 h after injections.

RBC (red-blood cell) haemolysis

Haemolytic activity of LDPs on human, rabbit and sheep erythrocytes was determined by measuring turbidity at 650 nm with a 96-well kinetic microplate reader UVMax (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, U.S.A.), as described previously [19]. RBCs were prepared from fresh blood by washing in 0.85% (w/v) NaCl. Anticoagulant solutions used were heparin, sodium-EDTA and sodium citrate respectively. Typically, 5–10 μl of peptide solution was added to the first microplate well and then serially diluted 2-fold into a buffer containing 120 mM NaCl, 10 mM Mes and 1 mM EDTA, pH 6.0. Subsequently, 100 μl of RBCs in the same buffer (1.2×107 cells/ml) was added to each well. The initial apparent absorbance (A) at 650 nm was approx. 0.1. The percentage of haemolysis was calculated as (Ai−Af)/(Ai−Aw)×100, where Ai and Af are the absorbance values at the beginning and the end of the reaction respectively, whereas Aw is the absorbance value obtained by hypotonic lysis with pure water. Haemolytic activity was reported as 1/C50 value, where C50 is the peptide concentration causing 50% RBC lysis.

Calcein release assay of membrane-permeabilizing activity

LUVs (large unilamellar vesicles), loaded with a self-quenching concentration of calcein (80 mM), were used to check membrane-permeabilizing activity of peptides, as described previously [36]. LUVs were prepared by extrusion through two stacked polycarbonate filters with 100 nm pores. Prepared vesicles were monodisperse with a diameter of approx. 100 nm, as measured by quasi-elastic light scattering [37]. External non-encapsulated calcein was removed by spinning the LUVs suspension through a mini-column packed with Sephadex G50 medium. The lipid mixtures reported elsewhere in the paper are given on a molar basis. The permeabilizing assay was performed using a kinetic microplate fluorimeter reader (Fluostar, SLT, Groeding, Austria), as reported previously [38]. Aliquots of washed LUVs were introduced into each well to a final lipid concentration of 6–8 μM in 200 μl of 10 mM Mes, pH 6.0, containing 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA. Interferometric filters (485 nm excitation wavelength; 538 nm emission wavelength) were used. The percentage permeabilization (R%) was then calculated as (Ffin−Fin)/(Fmax−Fin)×100, where Fin and Ffin represent the initial and final value of fluorescence before and after peptide addition respectively, and Fmax is the maximum calcein release, which was obtained by adding 1 mM Triton X-100. Unspecific binding of protein and liposomes to plastic microplate walls was strongly reduced by pre-treating the microplate with a 0.1 mg/ml Prionex solution. In all experiments, spontaneous calcein leakage was so small as to be neglected.

Data were analysed further using a statistical model introduced by Parente et al. [39], improved by Rapaport et al. [40], and implemented in our laboratory using a software package [19,41]. This approach allowed an estimation of the main parameters governing the permeabilization process, i.e. the partition coefficient K1 of toxin monomers into the liposomes, the aggregation process of membrane-inserted monomers (K2) and the number of monomers (M) necessary for the formation of an active pore. The reported values were calculated as follows: a set of curves was generated by freely varying each of the three parameters in a wide range, curves with a χ2 (chi-square distribution) value between the minimal (χ2min) and χ2min+(χ2min/10) were selected, and their parameters were used to calculate the average±S.E.

Determination of the critical micellar concentration

Peptide critical micellar concentration was determined as described previously [19], at room temperature by measuring the contact angle between a 1 μl drop of water containing CM-A and a polypropylene surface. Measurement was obtained semi-automatically from the picture of each drop by a home-developed fitting routine. Measured angles were reported in a graph as a function of CM-A concentration. The obtained critical micellar concentration value corresponds to the peptide concentration where a discontinuity in that graph occurred.

Pore-forming activity on planar lipid bilayers

Ion-channel-forming ability of CM-A was studied on planar lipid membranes made of 30% (mol/mol) cholesterol in 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycerophosphocholine. Peptide was added on one side only (called the ‘cis’ side) to stable pre-formed bilayers bathed in 10 mM Mes/100 mM KCl, pH 6.0. The trans side was held at virtual ground. Currents were recorded by a patch clamp amplifier (Axopatch 200, Axon Instruments); a DigiData 1200 A/D converter (Axon Instruments) connected to a personal computer was used for data acquisition. Current traces were filtered at 100 Hz and computer-acquired using the Axoscope 8 software (Axon Instruments). Measurements were performed at room temperature.

RESULTS

Purification of lipodepsinonapeptides from P. corrugata

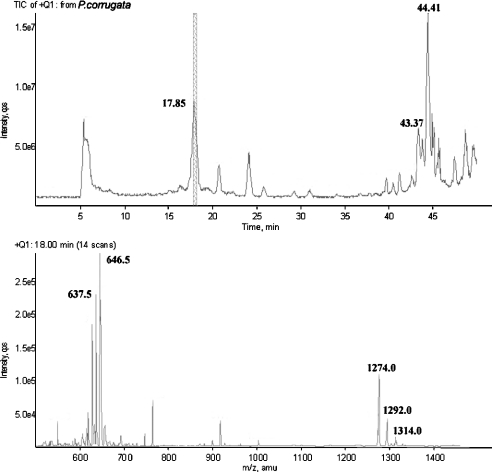

Chromatographic analysis of culture filtrates from selected P. corrugata strains showed the typical pattern already observed in P. syringae extracts, characterized by the presence of two groups of compounds with different polarity [13]. In particular, P. corrugata strain IPVCT 10.3 showed the profile reported in Figure 1 (top panel). Peaks eluting at 43.37 and 44.41 min corresponded to corpeptin A and B (M-H+ ion at m/z 2095.3 and 2121.2 respectively). On the other hand, the compound eluting at 17.85 min presented an M-H+ ion at m/z 1274.0–1276.0 (Figure 1, bottom panel). Although this value was in the range of that observed for other Pseudomonas lipodepsinonapeptides, it did not match any of the known ones. This finding suggests that P. corrugata strain IPVCT 10.3 produced a new metabolite, which we named ‘cormycin A’ (CM-A). In some culture filtrates, peaks corresponding to corpeptins were not detected, thus suggesting that production of long-chain LDPs by P. corrugata strains was dependent on strain variability and growth conditions, even though genetic potential for production of both toxin groups was present. This would explain the lack of nonapeptides in the culture filtrate studied by Emanuele et al. [22]. It is likely that LDP production by P. corrugata strains has a regulation different from that already reported in P. syringae strains. In fact, wild-type P. syringae always produces both toxins, although mutants defective in the production of one of the two type of toxins were obtained.

Figure 1. Representative chromatogram of P. corrugata extracts and mass spectrum CM-A.

Top panel reports the total ion current trace; bottom panel shows the mass spectrum of the compound eluted at 17.85 min.

Structural analysis of CM-A

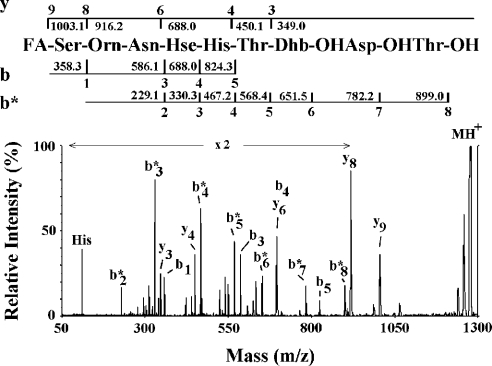

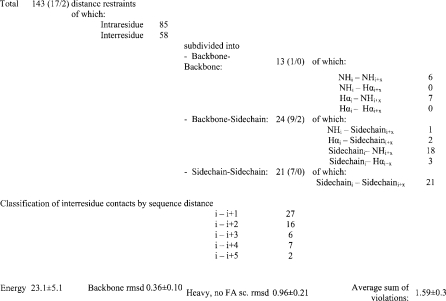

The complete structure of CM-A was elucidated by combined chemical degradation, MS and two-dimensional NMR procedures. Quantitative amino acid determination showed the occurrence of one mol each of serine, Orn (ornithine), Asx (Asn or Asp), Hse (homoserine), histidine, aThr (allo-threonine), Asp(3-OH) (3-hydroxyserine) and Thr(4-Cl) (4-chlorothreonine). Furthermore, two-dimensional NMR investigation reached the same conclusion, and identified a Dhb (2,3-dehydro-2-aminobutanoic acid) residue and the 3,4-dihydroxyexadecanoyl fatty acid. All amino acid residues, with the exception of Orn and Hse, presented an L-absolute configuration, as determined by derivative formation with 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrophenyl-5-L-alanine amide. The presence of a chlorine atom/molecule was confirmed by the typical M-H+ ion doublet already detected in other LDPs from P. syringae strains. The possibility that CM-A was a lipodepsinonapeptide was supported by the occurrence in the molecule of nine amino acid residues and a long dihydroxyacyl chain, as well as from the difference of 18 mass units between the calculated sum of the different moieties and the measured molecular mass. Moreover, this hypothesis was reinforced from the observed addition of one mole of water (M-H+ ion at m/z 1292.0–1294.0 as a doublet) by treatment with ammonium bicarbonate, followed by substitution of chloride with a hydroxy group (M-H+ ion at m/z 1274.1 as a singlet). Tandem MS analysis of this latter species produced a fragmentation pattern from which the partial sequence Ser-Orn-Asn-Hse-His-aThr-Dhb-Asp(3-OH)-Thr(4-OH) was deduced (Figure 2). This finding was integrated with data derived by direct MALDI–TOF-MS analysis of partial acid hydrolysates that allowed us to confirm the structure proposed for CM-A (Table 1). In these hydrolysates, an acid-catalysed conversion of the side-chain-amide moiety (Asn) to carboxylate (Asp) was observed.

Figure 2. MALDI–TOF post-source decay mass spectrum of the linear peptide with M-H+ ion at m/z 1274.1 obtained from CM-A following alkaline treatment.

Measured mass values and assigned ions are indicated. In addition to b- and y-type ions, the spectrum showed the occurrence of b*-type ions generated after the initial cleavage of the peptide bond between serine and Orn residues. FA, fatty acid.

Table 1. Structure of CM-A and some products generated by its partial acid hydrolysis.

The structural analysis performed by two-dimensional high-field NMR spectroscopy allowed the complete assignment of the resonances of each amino acid residue (Supplementary Table 1S, http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/384/bj3840025add/htm). Results were consistent with MS data: the presence of hydroxylic groups in positions β and γ of the fatty chain was clearly demonstrated by the TOCSY connectivities and by the HMQC experiments. The length of the fatty acid moiety was determined by the integration of the fatty acid chain resonances with respect to the amino acid resonances. The closure of the lactone ring between the carboxy group of Thr(4-Cl) and the hydroxy moiety of serine was clearly indicated by the diagnostic 1H and 13C chemical-shift values. The NOESY spectrum showed the cross-peaks due to dipolar connectivities. In particular, the CαHi/NH(i+1) crosspeaks (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 2S, http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/384/bj3840025add/htm) allowed us to determine the peptide sequence, which was in agreement with the data reported above. In addition, the Z-configuration of the double bond in the Dhb residue was assigned on the basis of the NOE (nuclear Overhauser effect) cross-peaks between the CHβ-Dhbi and NH(i+1).

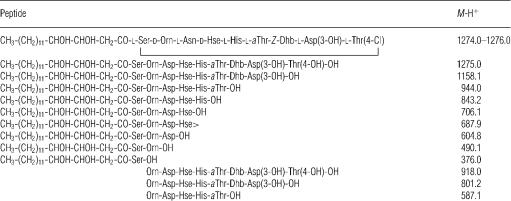

Figure 3. Statistics of NOEsy-derived interprotonic contacts for CM-A.

Assigned cross-peaks used in structural determination are classified in terms of distance and topology. The numbers of violations, occurring at least in five energy-minimized structures (<0.2 Å and >0.2 Å respectively) are reported in parentheses. Average energy (in kcal·mol−1), root-mean-square deviations for backbone and heavy atoms (excluding fatty-acid side chains) (in Å) and average value of the distance violation sum (in Å) for the best 20 refined structures are also shown, alongside their corresponding S.D.s.

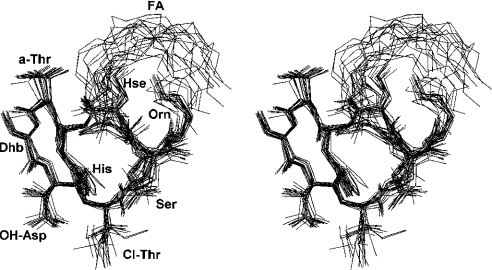

Structure of CM-A in solution

The refined structure set, obtained with the restraints summarized in Figure 3 (for a complete restraint list, see the NOE peak table in Supplementary Table 2S, http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/384/bj3840025add/htm) exhibited a very satisfying spatial convergence, with root-mean-square deviation values of 0.36, 0.39 and 0.96 Å for backbone atoms, backbone atoms plus the two heavy atoms of the L-Ser1 side chain involved in peptide-lactone ring closure, and all heavy atoms, excluding lipidic side chain, respectively, and a small number of violations, mostly under 0.2 Å (Figure 3). Dihedral angle analysis (Table 2) and visual inspection of the final bundle (Figure 4) both showed that, in addition to the backbone, a strict convergence (angular order parameter values >0.85) was also obtained for side chains of L-Ser1 (involved in the lactone ring closure), D-Orn2 (χ1), D-Hse4, L-His5, L-aThr6 and L-Asp(3-OH)8 (χ1). In particular, L-His5 side chain exhibited a very limited conformational flexibility, with the imidazole ring pointing inwards with respect to the peptide ring. This rigidity can be related mainly to several medium and long-range NOE correlations, involving His5 with Z-Dhb7, Asp(3-OH)8 and Thr(4-Cl)9 [see the NOE table (Supplementary Table 2S, http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/384/bj3840025add/htm)]. This orientation was in part stabilized by hydrogen bond interactions of the side-chain -NH group with amide carbonyl groups from both L-His5 and L-Asp(3-OH)8. Another noteworthy side chain orientation was that of D-Orn2, whose terminal amino group was involved in hydrogen-bond interactions, mainly with D-Hse4 side chain, but also with the polar part of the lipid. This amino acid was shielded from solvent by the hairpin-folded lipid hydrophobic chain. This feature provided a reasonable explanation for the detectability of NMR signals from side chain amino protons, which are usually not observable in peptides, because of their fast exchange with solvent protons, and for the relatively low value (−2.8 ppb·K−1) of the temperature coefficient calculated for these protons in the 282–300 K temperature range, usually associated with a moderate solvent interaction only in the higher temperature region of the range.

Table 2. Dihedral angle statistics of best 20 structures in solution of CM-A.

For each angle, average values are reported in degrees. Angular order parameter (S) values are also shown in parentheses. Bold values correspond to angles associated with the peptide-lactone ring backbone. χ values in the fatty acid (FA) side chain are omitted. The last atom involved in χ2 dihedral definition for Ser1 is C(10). ψ and ω′ angles in L-Thr(4-Cl)9 are defined as N(10)-Cα(10)-C(10)-Oγ(2) and Cα(10)-C(10)-Oγ(2)-Cβ(2) respectively.

| ω | Φ | χ1 | χ2 | Others | ψ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA | −28 (0.58) | |||||

| L-Ser1 | 179 (0.99) | 22 (0.48) | −51 (0.99) | 140 (0.81) | ω′: 177 (0.99) | −36 (0.95) |

| D-Orn2 | −177 (0.99) | 151 (0.98) | −65 (0.99) | 86 (0.80) | χ3: 108 (0.49) | −32 (0.99) |

| L-Asn3 | 172 (1.00) | −56 (0.99) | −53 (0.72) | 15 (0.75) | −29 (0.96) | |

| D-Hse4 | 177 (1.00) | 88 (0.94) | −163 (0.99) | −179 (0.99) | χ3: −177 (0.97) | 37 (0.99) |

| L-His5 | −176 (1.00) | −120 (0.99) | 48 (1.00) | 45 (1.00) | 92 (0.99) | |

| L-aThr6 | 178 (1.00) | −57 (1.00) | −63 (1.00) | χ21: −179 (1.00) | χ22: −47 (0.91) | 94 (0.99) |

| Z-Dhb7 | 173 (1.00) | 133 (1.00) | 86 (1.00) | −14 (1.00) | ||

| L-Asp(3-OH)8 | 177 (1.00) | −118 (0.99) | −162 (0.97) | χ21: −106 (0.80) | χ22: −30 (0.35) | 160 (1.00) |

| L-Thr(4-Cl)9 | −171 (1.00) | −49 (0.89) | 99 (0.36) | χ21: −135 (0.04) | χ22: −23 (0.67) | 120 (0.95) |

Figure 4. Bundle of the best 20 structures of CM-A in solution.

A stereoscopic diagram showing the best-fit ring superposition (calculated on backbone atoms plus heavy atoms of the Ser1 side chain) is shown. Hydrogen atoms are omitted.

The overall backbone conformation of the peptide, resulting from the presence of alternating stereochemistry at the Cα atom, a lactone ring, a conformationally restrained unusual residue (Z-Dhb7), and a large lipid chain, exhibits mostly non-canonical dihedral angle values, with no typical secondary structure element, and a mixture of positively and negatively valued Φ angles. However, a slightly distorted type II β-turn centred on L-aThr6-Z-Dhb7 is stably observed, whereas L-Asp(3-OH)8 shows a substantially extended conformation in all the refined structures (Table 2).

This conformation is stabilized, in addition to the interactions described above, by a network of hydrogen bonds of high- to medium-stability, including both backbone–backbone and backbone–side chain interactions. In particular, strong stabilizing hydrogen bonds are observed between D-Hse4 and NH, and fatty acid and CO groups (and, to a lesser extent, D-Orn2), as well as between L-Asp(3-OH)8 and NH, and L-His5 and CO groups (this latter locking the aforementioned β-turn). The hydrogen-bond pattern, combined with a solvent-accessibility analysis, also explains the temperature coefficient values observed for amide protons in the 282–300 K temperature range. In fact, a very low value (0.5 ppb·K−1), corresponding to virtually no interaction with the solvent, is observed for the D-Hse4 HN proton, which is both involved in hydrogen bonding and totally inaccessible to the solvent in all the final structures, whereas low to intermediate values (−3.2 and −3.0 ppb·K−1) are exhibited by L-Asp(3-OH)8 HN and L-His5 HN protons respectively. Although L-Asp(3-OH)8 HN is strongly involved in the β-turn hydrogen bond, it has a very small, average accessibility (2.0% of the maximum accessibility), with a maximum value of 5.3% in the whole structure set, which could account for a limited solvent interaction. On the other hand, L-His5 HN is not involved in hydrogen-bond interactions, but is totally shielded from the solvent in the structure set. However, the lack of local rigidity resulting from the absence of strong polar interactions is associated with larger local fluctuations in molecular dynamics simulations (results not shown), and this could explain the limited solvent interaction apparently indicated by the temperature coefficient value. All other amide protons exhibited no hydrogen-bond interactions and/or higher solvent accessibilities, and this feature correlates well with their temperature coefficients, spanning a range from −5.0 to −11.2 ppb·K−1, usually associated with a strong interaction with solvent. Only L-Asn3 exhibited a positive value (5.8) of the coefficient, which is usually interpreted as being associated with conformational equilibrium at a higher temperature.

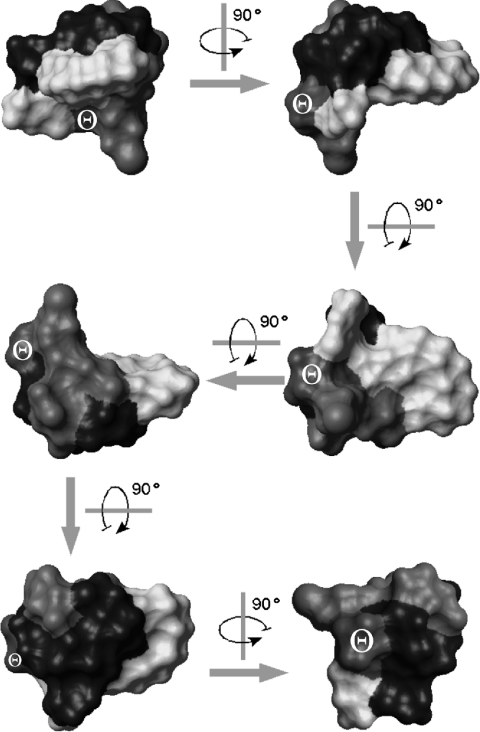

The representative structure of the final bundle had a rather compact shape, resulting from an inward orientation of some side chains (D-Orn2, D-Hse4 and L-His5), and from the ‘hairpin-bent’ conformation of the lipid due to inter-residue interactions, corresponding to observed NOE effects of its terminal part with D-Orn2 and D-Hse4 (see Supplementary Table 2S, http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/384/bj3840025add/htm). This arrangement results in an ‘L’-shaped, almost orthogonal (89°) orientation both of the average planes of the lactone ring and of the bent fatty acid side chain. An analysis of residue distribution on the molecular surface showed the presence of highly distinctive regions of polarity: a concave hydrophobic surface, including the lipid and Z-Dhb7 side chains, and a larger, mainly convex region containing polar and charged residues (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Rotated views of CM-A representative structure in solution.

The solvent-accessible surface (calculated with a probe radius of 1.4 Å) is shown in light grey, medium grey, medium grey with a Θ symbol, and dark grey for hydrophobic, neutral polar, acidic and basic residues respectively. The different orientations shown in the Figure are obtained by 90° rotations around orthogonal axes, as indicated on the corresponding arrows.

Biological activity

P. corrugata culture filtrates presented a strong antimicrobial activity against B. megaterium and R. pilimanae. Similarly, purified CM-A was able to inhibit bacterial growth, and its antimicrobial effect was elicited at low micromolar concentrations (Table 3). Its activity against these micro-organisms was higher than that observed for other lipodepsinonapeptides from P. syringae. Similarly to other LDPs, CM-A also exhibited phytotoxic activity, as measured by chlorosis induction on N. tabacum leaves (Table 3). The necrotic symptoms caused by a 10 μM solution of CM-A (after 48 h) are shown in Figure 6. Symptoms were similar to those obtained using whole P. corrugata culture filtrates, thus confirming that this peptide is essential for the biological activity of this bacterium.

Table 3. Antimicrobial activity of CM-A against B. megaterium and Rh. pilimanae and phytotoxic activity on N. tabacum.

Measurements were performed in comparison with SR-E and ST. MIC, minimal inhibitory concentration.

| Specific activity (units/μg) | MIC (μM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. megaterium | R. pilimanae | B. megaterium | R. pilimanae | Time of chlorosis induction (h) | |

| CM-A | 3.0 | 8.0 | 3 | 3 | 24 |

| SR-E | 1.3 | 5.0 | 5 | 5 | 48 |

| ST | 1.0 | 2.5 | 9 | 9 | 72 |

Figure 6. Toxicity of P. corrugata and purified CM-A to host plant leaves.

Symptoms shown by tobacco leaves 48 h after infection. Left of the central leaf vein, P. corrugata infection; right, pure CM-A (10 μM) injection.

In addition, CM-A lysed human, rabbit and sheep RBCs (Table 4). Its haemolytic activity was dependent on peptide concentration, and was similar with human and rabbit erythrocytes (C50≈20 nM), but 5-fold smaller with sheep erythrocytes. A similar trend was observed for the other lipodepsinonapeptides from P. syringae that were tested. In addition, comparative measurements showed that CM-A was more active than SR-E and ST (Table 4) [19,42].

Table 4. Haemolytic activity of CM-A and its permeabilizing activity on vesicles with different lipid composition.

Measurements were performed in comparison with syringomycin E and syringotoxin. Lipid mixtures are reported on a molar basis. n.d., not determined; Chol, cholesterol; Erg, ergosterol; Sti, stigmasterol.

| 1/C50* (106 M−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| CM-A | SR-E | ST | |

| Target cells | |||

| Human RBC | 50±8 (11)† | 2.0±0.2 (9) | 0.3±0.1 (4) |

| Rabbit RBC | 40 (1) | 0.8±0.3 (2) | 0.2 (1) |

| Sheep RBC | 10±1 (3) | 0.4±0.1 (3) | 0.07±0.02 (3) |

| Target liposomes | |||

| PC | <0.05 (1) | 0.14±0.02 (3) | <0.05 (1) |

| PC:PA (1:1) | <0.05 (1) | <0.1 (1) | <0.05 (1) |

| PC:PI (1:1) | <0.04 (1) | <0.1 (1) | <0.05 (1) |

| Asolectin | 0.06±0.01 (3) | 0.03 (2) | <0.01 (3) |

| PC:SM (1:1) | 0.03 (1) | 1.1±0.1 (3) | <0.05 (1) |

| PC:Chol (1:1) | 1.7±0.8 (2) | 20±8 (2) | 0.2 (1) |

| PC:Erg (1:1) | 0.59±0.03 (2) | 2.5±0.6 (3) | 0.06 (1) |

| PC:Sti (1:1) | 0.21±0.01 (2) | 0.04±0.02 (2) | 0.02 (2) |

| PC:Chol:SM (1:0.7:0.3) | 1 (1) | 3.3±1.1 (2) | n.d. |

| PC:PA:Chol:SM (0.9:0.1:0.7:0.3) | 2.7 (1) | 2.6 (1) | 0.04 (1) |

| PC:PA:Chol:SM (0.1:0.9:0.7:0.3) | 1.3 (1) | 2.6 (1) | 0.04 (1) |

* Activity is expressed as 1/C50, where C50 is the micromolar concentration of LDP causing 50% of erythrocyte haemolysis or of calcein release.

† The error shown corresponds to S.D.; in parentheses the number of repetitions is shown.

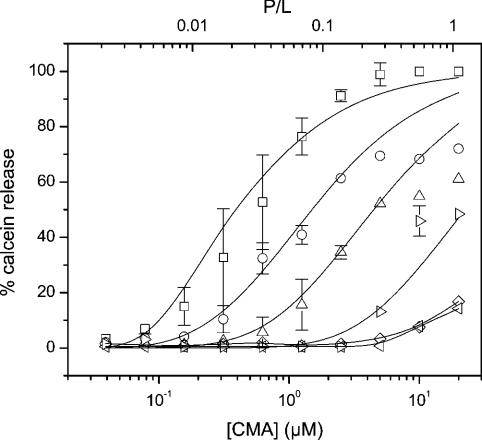

CM-A was also able to interact with and permeabilize artificial membranes. The leakage of calcein was dependent on peptide concentration and liposome lipid composition (Figure 7 and Table 4). CM-A was far more active when a sterol was present as a component of the liposome membranes (Table 4). Among all sterols tested, cholesterol (mainly present in animal cell membranes) provided the highest sensitivity, followed by ergosterol (a major component of fungal plasma membranes) and stigmasterol (the main sterol component of higher plant membranes). This preference for sterol-containing membranes has been already reported for SR-E [19] and ST (Table 4), although animal cells are not the natural targets of these LDPs. The presence of negatively charged lipids (i.e. phosphatidic acid and phosphatidylinositol) did not improve, but rather hampered, CM-A activity. Moreover, SM made LUVs less prone to CM-A permeabilization. The observed reduced activity on SM-containing liposomes correlates well with the lower haemolytic activity measured on sheep RBCs. In fact, sheep erythrocytes present a higher content of SM and a reduced percentage of PC with respect to the other RBCs tested, whereas the content of the other phospholipids and cholesterol is similar [43].

Figure 7. Dose-dependence of CM-A-permeabilizing activity on liposomes with different lipid composition.

Calcein-loaded liposomes were exposed to different peptide concentrations, and the percentage of calcein released after 45 min is reported. The scale on the top x-axis shows the peptide-to-lipid molar ratio. Lines through the points are best-fit plots, fitted according to the statistical model described in the text. Best values of fitting parameters were as follows: □, PC/cholesterol: K1=5.8±0.7×102 M−1, M=7±1, K2=320±30×10−3; ○, PC/ergosterol: K1=5.9±0.7×102 M−1, M=6±1, K2=80±10×10−3; ▵, PC/stigmasterol: K1=5.5±0.9×102 M−1, M=7±1, K2=38±9×10−3; ⊳, asolectin: K1=5.1±0.7×102 M−1, M=7±1, K2=13±2×10−3; ⋄, PC/SM: K1=4.4±0.8×102 M−1; M=7±1; K2=4±1×10−3; ⊲, PC: K1=4.2±1.0×102 M−1; M=6±1; K2=2.5±0.7×10−3.

In general, the Parente-Rapaport model, based on a pore-forming mechanism, described our data well, at least for peptide concentrations lower than 10 μM (Figure 7). According to this model, the difference in activity was related to a different degree of reversibility of surface aggregation of the adsorbed monomers (K2). In fact, CM-A bound to PC/cholesterol LUVs showed a low degree of reversibility (K2=0.3); on the contrary, increased levels of reversibility were observed for PC/ergosterol, PC/stigmasterol and other-composition vesicles. In all cases, the partition coefficient (K1) was almost constant. Similarly, the number of monomers constituting the active channel was always in the range of 7±1. All the parameters calculated for the different LUVs are shown in the legend to Figure 7.

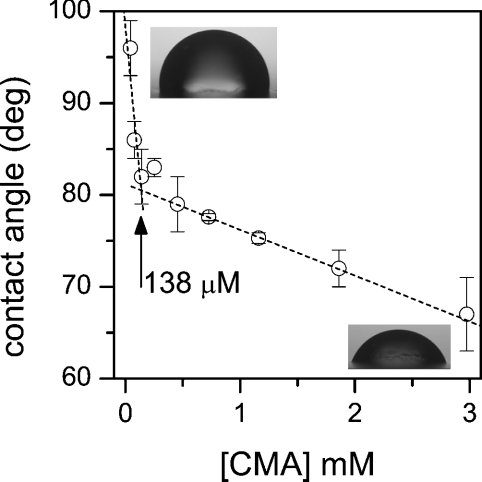

To better understand the strongest interaction of CM-A with RBC, the critical micellar concentration of this peptide was measured. Normally, this parameter is inversely related to membrane-permeabilizing properties. Our experiments demonstrated that CM-A presents a critical micellar concentration of 138 μM (Figure 8), a value approx. 10 times lower than that measured for SR-E [19]. Accordingly, CM-A is more hydrophobic than SR-E [17,19]; this result is consistent with the strongest propensity of CM-A to partition into membranes. On the other hand, the ability of CM-A to self-associate in solution into micelles could delay the process of membrane penetration at concentrations above the critical micellar concentration, providing a possible explanation of the saturating permeabilization effect observed in Figure 7.

Figure 8. Determination of the critical micellar concentration of CM-A.

Drops (1 μl volume) containing CM-A at the reported concentrations in pure water were gently deposited on a flat polypropylene surface, and the contact angles were measured. Points reported are averages±S.D. for at least three measurements. Critical micellar concentration is indicated by the arrow, and corresponds to the sharp bend in the curve. Insets show pictures of the drops at the highest (lower-right corner) and lowest (upper-left corner) CM-A concentrations.

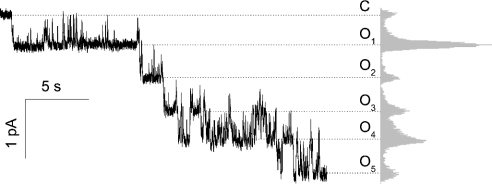

The pore-forming mechanism of action for CM-A was well supported by planar lipid-bilayer experiments. Addition of CM-A to a solution bathing a planar lipid bilayer made of 7:3 (mol/mol) 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycerophosphocholine/cholesterol increased the membrane conductance, causing step-like current transitions (Figure 9). This behaviour is peculiar to the formation of structured conducting pathways across the membrane (i.e. pores), rather than being due to an unspecific detergent-like activity. From the representative trace reported in Figure 9, a single channel conductance of 3.9±0.6 pS was measured.

Figure 9. Formation of ion channels by CM-A in planar lipid bilayer.

Addition of a 11 μM CM-A solution to the buffer bathing the membrane was able to cause discrete increases of the ionic current through the membrane. Each step-like current increase corresponded to the opening of a single channel with an average conductance of 3.9±0.6 pS. The closed state (C) and the different open levels (Oi) are marked with dashed lines. The i parameter corresponds to the number of single channels simultaneously open; its value ranged from 1–5. On the right, the occupation histogram of each level is shown. The applied voltage was −140 mV; the buffer used was 100 mM KCl/10 mM Mes, pH 6.0. Membrane composition was 7:3 (mol/mol) 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycerophosphocholine/cholesterol.

DISCUSSION

The growing problem of microbial resistance to conventional antibiotics and the need for new compounds with antibiotic properties has stimulated interest in the development of antimicrobial and antifungal peptides as human therapeutics. The main hurdles impeding the use of antimicrobial peptides in systemic therapy include the high doses, close to toxic ones, at which they are effective in animal models of infection. Nevertheless, a series of antimicrobial peptides are now under pharmaceutical development [44,45]. In this scenario, Pseudomonas LDPs have shown promising features based on their effective antimicrobial and antifungal properties [46,47]. They can be potentially employed in mycoses and systemic fungi infections caused by Candida ssp., Aspergillus fumigatus and Fusarium spp., which are emerging as problems for immunocompromised hosts [2]. In fact, the usefulness of azole-based drugs (e.g. fluconazole) against fungal infections is limited by the lack of a broad spectrum of activity, or by severe toxicity phenomena. Moreover, LDPs have also shown a potential use as biocontrol agents in agriculture [4]. In fact, Pseudomonas-based formulates are marketed in the U.S.A. for citrus post-harvest treatment, and the association between LDPs and cell-wall-degrading enzymes has proved to be very effective against several plant pathogens [48].

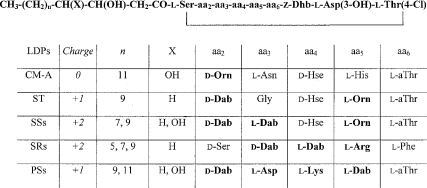

In the present study, we have reported the structural and biological properties of a new LDP, namely CM-A. CM-A shares several structural features with other lipodepsinonapeptides from P. syringae spp. (Figure 10). They all present a similar hydroxy-fatty acyl moiety at the N-terminus, a similar nonapeptide cyclic structure closed by a lactone bond between conserved residues, three common peculiar amino acids, i.e. Z-Dhb, L-Asp(3-OH), and L-Thr(4-Cl), and two residues with a D-absolute configuration at not-fixed positions in the polypeptide chain. Main differences between CM-A and the other P. syringae LDPs were ascribed to the nature of the amino acids occurring at positions 2–6, as well as to the molecular net charge. In fact, all P. syringae lipodepsinonapeptides have a positive net charge as a result of the presence of two or three positively charged residues in the amino acid region 2–5 (Figure 10), whereas only a negatively charged residue [Asp(3-OH)] is present in the conserved region of amino acids 6–8. On the other hand, CM-A presents only a single positively charged residue at neutral pH in these positions. In fact, the imidazole of its histidine residue has a measured pKa value of 6.0, and an ionization strongly influenced by interactions with proximal amino acids.

Figure 10. Structural differences among PSs, SSs, ST, SRs and CM-A.

The general structure of Pseudomonas lipodepsinonapeptides is reported on the top. Peptide net charge was calculated at pH 7.0. Orn, ornithine; Hse, homoserine; aThr, allo-threonine; Dab, 2,4-diamino-butanoic acid; Dhb, 2,3-dehydro-2-amino-butanoic acid; Asp(3-OH), 3-hydroxyaspartic acid; Thr(4-Cl), 4-chlorothreonine. Charged residues are shown in bold.

A detailed comparative analysis of the three-dimensional structure of CM-A with respect to those already published for ST [9] and pseudomycin A [11] was not possible. In fact, all structural analyses were performed under different experimental conditions. However, although influences due to solvent effects have to be considered, CM-A has a cyclic structure, with some amino acids shielded from solvent by its hairpin-folded lipid hydrophobic chain, similarly to what has already been reported previously for ST, but different from that reported for pseudomycin A. Preliminary modelling studies on CM-A suggest that this lipodepsipeptide should form oligomeric channel structures containing six to eight monomers (results not shown), in agreement with biological data derived from lipid bilayer permeabilization measurements (Figure 7).

Based on mechanism of action of antimicrobial cationic peptides from multicellular organisms towards bacterial membranes [44,45], two main structural features have been proposed to strongly affect the biological activity of Pseudomonas spp. LDPs, i.e. the occurrence of basic residues and the presence of specific hydrophobic moieties [3,46]. It has been suggested that positive charges should facilitate interaction with negatively charged phospholipids, allowing LDP to insert itself into membrane bilayers as a result of its amphipathic nature [47]. Although these features should strongly promote initial peptide-membrane targeting, other important and unknown physicochemical phenomena have to be considered to definitively understand the mechanism of action of these molecules. In fact, our comparative data on antimicrobial, phytotoxic and haemolytic properties of Pseudomonas LDPs (Tables 3 and 4), in contrast with the general structural criteria reported above, demonstrated that the peptide homologue with the most reduced positive net charge (i.e. CM-A) presents the highest biological activity. Moreover, measurements on artificial vesicles of different lipid composition demonstrated for all these LDPs (Table 4) that permeabilization was not improved by the presence of negatively charged phospholipids, hypothetical targets of basic amino acids. On the other hand, LUV permeabilization was strongly increased by sterols (Table 4). These findings are in perfect agreement with previous data on P. syringae lipodepsinonapeptides, showing by a genetic approach that ergosterol, the main component of the fungal plasma membrane, and cholesterol or stigmasterol, are implicated in their mechanism of action [49]. On the other hand, this observation strongly contrasts with the decreased activity of antimicrobial cationic peptides from multicellular organisms in sterol-containing membranes [50], again suggesting that modified models of interaction, with respect to those adopted for ribosomally synthesized peptides from multicellular organisms, have to be proposed to fully explain the activity of Pseudomonas LDPs towards fungal plasma membranes. These considerations correlate well with recent publications on other bacterial peptides [47,50].

In conclusion, although not as active as other well-known pharmaceutical derivatives, Pseudomonas LDPs show potential as lead compounds for the development of effective antifungal agents. They are fungicidal against important human pathogens, soluble in aqueous solution, and they seem to have a unique mechanism of action. The structural and biological properties of CM-A reported in the present study provide new insights into previous information on structure–function relationships regarding these molecules. Promising new studies are now in progress to modify specific LDP chemical functionalities, in an attempt to enhance their antifungal activity and reduce their toxicity.

Online data

Acknowledgments

We thank Teuzin Wangdu and Claudio Della Volpe for their kind technical assistance and scientific discussion in critical micellar concentration experiments. This work was financially supported by grants from the Italian National Research Council, Istituto Trentino di Cultura and Provincia Autonoma di Trento (PAT, project AGRIBIO) and PRIN 2002. The bacterial strain IPVCT 10.3 was kindly supplied by Dr. G. Cirvilleri (University of Catania, Italy).

References

- 1.Bender C. L., Alarcón-Chaidez F., Gross D. C. Pseudomonas syringae phytotoxins: mode of action, regulation and biosynthesis by peptide and polyketide synthetases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999;63:266–292. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.266-292.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Lucca A. J., Jacks T. J., Takemoto J. Y., Vinjard B., Peter J., Navarro E., Walsh T. J. Fungal lethality, binding, and cytotoxicity of syringomycin-E. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999;43:371–373. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y.-Z., Sun X., Zeckner D. J., Sachs R. K., Current W. L., Jidda J., Rodriguez M., Chen S. H. Syntheses and antifungal activities of novel 3-amido bearing pseudomycin analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;11:903–907. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bull C. T., Wadsworth M. L., Sorensen K. N., Takemoto J. Y., Austin R. K., Smilanick J. L. Syringomycin E produced by biological control agent controls green mold on citrus. Biol. Control. 1998;12:89–95. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradbury J. F. CMI Descriptions of Pathogenic Fungi and Bacteria, No 893. Kew, U.K.: Commonwealth Mycological Institute, CAB International; 1987. Pseudomonas corrugata. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chun W., Leary J. V. Novel toxin produced by Pseudomonas corrugata, the causal agent of tomato pith necrosis. In: Graniti A., Durbin R. D., Ballio A., editors. Phytotoxins and Plant Pathogenesis. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1989. pp. 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segre A. L., Bachmann R. C., Ballio A., Bossa F., Grgurina I., Iacobellis N. S., Marino G., Pucci P., Simmaco M., Takemoto J. Y. The structure of syringomycin A1, E and G. FEBS Lett. 1989;255:27–31. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ballio A., Barra D., Bossa F., DeVay J. E., Grgurina I., Iacobellis N. S., Marino G., Pucci P., Simmaco M., Surico G. Multiple forms of syringomycin. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 1988;33:493–496. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ballio A., Bossa F., Collina A., Gallo M., Iacobellis N. S., Paci M., Pucci P., Scaloni A., Segre A. L., Simmaco M. Structure of syringotoxin, a bioactive metabolite of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. FEBS Lett. 1990;269:377–380. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81197-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukuchi N., Isogai A., Nakayama S., Suzuki A. Structure of syringostatins A and B, novel phytotoxins produced by Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae isolated from lilac blights. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:695–698. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coiro V. M., Segre A. L., Di Nola A., Paci M., Grottesi A., Veglia G., Ballio A. Solution conformation of the Pseudomonas syringae MSU 16H phytotoxic lipodepsipeptide Pseudomycin A determined by computer simulations using distance geometry and molecular dynamics from NMR data. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998;257:449–456. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2570449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nutkins J. C., Mortishire-Smith R. J., Packman L. C., Brodey C. L., Rainey P. B., Johnston K., Williams D. H. Structure determination of tolaasin, an extracellular lipodepsipeptide produced by mushroom pathogen. Pseudomonas tolaasii. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:2621–2627. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ballio A., Barra D., Bossa F., Collina A., Grgurina I., Marino G., Moneti G., Paci M., Pucci P., Segre A. L., Simmaco M. Syringopeptins, new phytotoxic lipodepsipeptides from Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. FEBS Lett. 1991;291:109–112. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81115-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ballio A., Bossa F., Camoni L., Di Giorgio D., Flamand M. C., Marcite H., Nitti G., Pucci P., Scaloni A. Structure of fuscopeptins, phytotoxic metabolites from Pseudomonas fuscovaginae. FEBS Lett. 1996;381:213–216. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rinaldi A. C. Antimicrobial peptides from amphibian skin: an expanding scenario. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2002;6:799–804. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(02)00401-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Che F. S., Kasamo K., Fukuchi N., Isogai A., Suzuki A. Bacterial phytotoxin, syringomycin, syringostatin and syringotoxin, exert their effect on the plasma membrane H+-ATPase partly by a detergent action and partly by inhibition of the enzyme. Physiol. Plant. 1992;86:518–524. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hutchinson M. L., Tester M. A., Gross D. C. Role of biosurfactant and ion channel-forming activities of syringomycin in transmembrane ion flux: a model for the mechanism of action in the plant-pathogen interaction. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1995;8:610–620. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-8-0610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fegin A. M., Takemoto J. Y., Wangspa R., Teeter J. H., Brand J. G. Properties of voltage-gated ion channel formed by syringomycin E in planar lipid bilayers. J. Membr. Biol. 1996;149:41–47. doi: 10.1007/s002329900005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalla Serra M., Fagiuoli G., Nordera P., Bernhart I., Della Volpe C., Di Giorgio D., Ballio A., Menestrina G. The interaction of lipodepsipeptide toxins from Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae with biological and model membranes: a comparison of syringotoxin, syringomycin and syringopeptins. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1999;12:391–400. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1999.12.5.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalla Serra M., Bernhart I., Nordera P., Di Giorgio D., Ballio A., Menestrina G. Conductive properties and gating of channels formed by syringopeptin 25A, a bioactive lipodepsipeptide from Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae in planar lipid membrane. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1999;12:401–409. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1999.12.5.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agner G., Kaulin I. A., Gurnev P. A., Szabo T., Schagina L. V., Takemoto J. Y., Blasko K. Membrane-permeabilizing activities of cyclic lipodepsipeptides, syringopeptin 22A and syringomycin E from Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae in human red blood cells and in bilayer lipid membranes. Bioelectrochemistry. 2000;52:161–167. doi: 10.1016/s0302-4598(00)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emanuele M. C., Scaloni A., Lavermicocca P., Iacobellis N. S., Camoni L., Di Giorgio D., Pucci P., Paci M., Segre A. L., Ballio A. Corpeptins, new bioactive lipodepsipeptide from culture of Pseudomonas corrugata. FEBS Lett. 1998;433:317–320. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00933-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Catara V., Arnold D., Cirvilleri G., Vivian A. Specific oligonucleotide primers for the rapid identification and detection of the agent of tomato pith necrosis, Pseudomonas corrugata, by PCR amplification: evidence for two distinct genomic groups. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2000;106:753–762. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Surico G., Lavermicocca P., Iacobellis N. S. Produzione di siringomicina e siringotossina in colture di Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. Phytopathol. Med. 1988;27:163–168. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scaloni A., Simmaco M., Bossa F. D-amino acid analysis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2003;211:169–180. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-342-9:169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Güntert P., Mumenthaler C., Wüthrich K. Torsion angle dynamics for NMR structure calculation with the new program DYANA. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;273:283–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Case D. A., Pearlman D. A., Caldwell J. W., Cheatham T. E., III, Ross W. S., Simmerling C. L., Darden T. A., Merz K. M., Stanton R. V., Cheng A. L., et al. Vol. 6. San Francisco: University of California; 1999. AMBER. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J., Cieplak P., Kollman P. A. How well does a restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) model perform in calculating conformational energies of organic and biological molecules? J. Comput. Chem. 2000;21:1049–1074. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cornell W. D., Cieplak P., Bayly C. I., Gould I. R., Merz K. M., Jr, Ferguson D. M., Spellmeyer D. C., Fox T., Caldwell J. W., Kollman P. A. A second generation force field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic acids, and organic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:5179–5197. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt M. W., Baldridge K. K., Boatz J. A., Elbert S. T., Gordon M. S., Jensen J. J., Koseki S., Matsunaga N., Nguyen K. A., Su S., Windus T. L., Dupuis M., Montgomery J. A. The general atomic and molecular electronic structure system. J. Comput. Chem. 1993;14:1347–1363. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bayly C. I., Cieplak P., Cornell W. D., Kollman P. A. A well-behaved electrostatic potential based method using charge restraints for determining atom-centered charges: the RESP model. J. Phys. Chem. 1993;97:10269–10280. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cornell W. D., Cieplak P., Bayly C. I., Kollman P. A. Application of RESP charges to calculate conformational energies, hydrogen bond energies and free energies of solvation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:9620–9625. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koradi R., Billeter M., Wüthrich K. MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graphics. 1996;14:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavermicocca P., Iacobellis N. S., Simmaco M., Graniti A. Biological properties and spectrum of activity of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae toxins. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 1997;50:129–140. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iacobellis N. S., Lavermicocca P., Grgurina I., Simmaco M., Ballio A. Phytotoxic properties of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae toxins. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 1992;40:107–116. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kayalar C., Düzgünes N. Membrane action of colicin E1: detection by the release of carboxyfluorescein and calcein from liposomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1986;860:51–56. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(86)90497-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderluh G., Dalla Serra M., Viero G., Guella G., Macek P., Menestrina G. Pore formation by equinatoxin II, a eukaryotic protein toxin, occurs by induction of nonlamellar lipid structures. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:45216–45223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tejuca M., Dalla Serra M., Ferreras M., Lanio M. E., Menestrina G. Mechanism of membrane permeabilization by sticholysin I, a cytolysin isolated from the venom of the sea anemone Stichodactyla helianthus. Biochemistry. 1996;35:14947–14957. doi: 10.1021/bi960787z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parente R. A., Nir S., Szoka F. C. Mechanism of leakage of phospholipid vesicle contents induced by the peptide GALA. Biochemistry. 1990;29:8720–8728. doi: 10.1021/bi00489a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rapaport D., Peled R., Nir S., Shai Y. Reversible surface aggregation in pore formation by pardaxin. Biophys. J. 1996;70:2502–2512. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79822-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anzlovar S., Dalla Serra M., Dermastia M., Menestrina G. Membrane permeabilizing activity of linusitin from flax seed. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1998;11:610–617. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dalla Serra M., Menestrina G., Carpaneto A., Gambale F., Fogliano V., Ballio A. Molecular mechanism of action of syringopeptins, antifungal peptides from Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. In: Menestrina G., Dalla Serra M., Lazarovici P., editors. Pore-Forming Peptides and Protein Toxins, vol. 5; Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Toxin Action, Lazarovici, P., series ed. London: Taylor & Francis Group; 2003. pp. 272–295. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chapman D. London, UK: Academic Press; 1968. Biological Membranes, Physical Fact and Function. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature (London) 2002;415:389–395. doi: 10.1038/415389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hancock R. E., Lehrer R. Cationic peptides: a new source of antibiotics. Trends Biotechnol. 1998;16:82–88. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(97)01156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sorensen K. N., Kim K. H., Takemoto J. Y. In vitro antifungal and fungicidal activities and erythrocyte toxicities of cyclic lipodepsinonapeptides produced by Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. Antimicrob. Agent Chemother. 1996;40:2710–2713. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang L., Dhillon P., Yan H., Farmer S., Hancock R. E. W. Interactions of bacterial cationic peptide antibiotics with outer and cytoplasmic membranes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agent Chemother. 2000;44:3317–3321. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.12.3317-3321.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fogliano V., Ballio A., Gallo M., Woo S., Scala F., Lorito M. Pseudomonas lipodepsipeptides and fungal cell wall degrading enzymes are synergistic in the inhibition of fungal growth. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2002;15:323–330. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wangspa R., Takemoto J. Y. Role of ergosterol in growth inhibition of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by syringomycin E. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1998;167:215–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsuzaki K. Why and how are peptide–lipid interactions utilized for self-defense? Magainins and tachyplesins as archetypes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1462:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.